Introduction

Eustachian tube dysfunction is a poorly defined condition. It can be defined according to symptoms, signs and abnormalities on objective testing or based on pathological processes. There are several ways in which the Eustachian tube functions abnormally. These can be summarised as: impairment of pressure regulation, loss of protective function or impairment of clearance.Reference Bluestone, Rosenfeld and Bluestone 1

The potential symptoms (blocked sensation, ear fullness) do not always correlate with objectively determined dysfunction. In addition, a blocked sensation or pressure can also be symptoms of other conditions, such as Ménière's syndrome or migraine. There are no universally agreed diagnostic criteria for Eustachian tube dysfunction, although recent work has attempted to develop a consensus.Reference Schilder, Bhutta, Butler, Holy, Levine and Kvaerner 2

Eustachian tube dysfunction has a reported incidence of 1–5 per cent in the adult population.Reference Ockermann, Reineke, Upile, Ebmeyer and Sudhoff 3 Chronic obstructive Eustachian tube dysfunction has a prevalence of about 1 per cent in the adult population.Reference Ockermann, Reineke, Upile, Ebmeyer and Sudhoff 3 Eustachian tube dysfunction can occur because of anatomical (intrinsic or extrinsic) or functional obstruction.Reference Choi, Han and Chung 4

Abnormal function of the Eustachian tube is an important factor in the pathogenesis of middle-ear disease. This hypothesis was first suggested more than 150 years ago by Politzer.Reference Politzer 5 However, later studies suggested that otitis media was a disease primarily of the middle-ear mucous membrane, and was caused by infection or allergic reactions in this tissue rather than by dysfunction of the Eustachian tube.Reference Zollner 6 – Reference Sadé 9 Most otologists agree that Eustachian tube function is critical for the outcome of middle-ear surgery.Reference Podoshin, Fradis, Malatskey and Ben-David 10 , Reference Dorrie, Dommerich and Pau 11

Assessment and quantification of Eustachian tube dysfunction involve subjective or objective methods. Subjective methods include an assessment of patient symptoms or the use of more structured instruments such as the seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire (‘ETDQ-7’).Reference McCoul, Anand and Christos 12 Objective methods include otoscopy, pneumo-otoscopy, tympanometry, Valsalva's manoeuvre and audiometry.

Treatment for Eustachian tube dysfunction includes pharmaceutical treatment with anti-histamine or anti-inflammatory medications (such as topical or oral steroids) and surgery. Balloon Eustachian tuboplasty is a recent development for the treatment of Eustachian tube dysfunction.Reference Randrup and Ovesen 13 A catheter is inserted into the cartilaginous Eustachian tube whilst the patient is under general anaesthetic. The catheter has an integral balloon which is inflated with saline, dilating the cartilaginous Eustachian tube. This aims to improve the ventilatory and pressure-equalising function of the Eustachian tube in order to improve patient symptoms. There are no controlled studies of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty. Some cases of success may simply be the result of the natural course of the underlying pathology.Reference Jurkiewicz, Bien, Szczygielski and Kantor 14

We aimed to assess the efficacy of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty treatment in patients with chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction, who have persisting or recurrent symptoms and signs of Eustachian tube dysfunction despite previous surgical treatment. Objective (pre- and post-operative tympanometry and audiometry) and subjective (seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire) outcome measures were used to quantify the effect of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty on patients with chronic symptoms and signs suggestive of Eustachian tube dysfunction.

Materials and methods

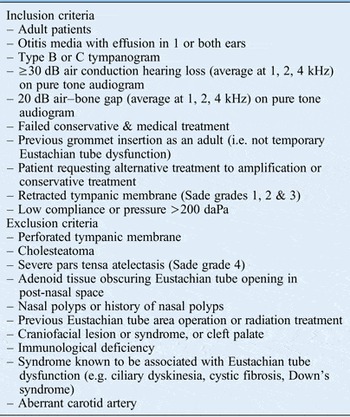

We undertook a prospective study of adult patients with evidence of chronic objective Eustachian tube dysfunction. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are set out in Table I. Study participants were recruited from adult ENT clinics at the University Hospital of Coventry and Warwickshire. The primary outcome measure was the presence or absence of a type A tympanogram on post-operative follow up. Secondary outcome measures included pure tone audiogram assessment and seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire score.

Table I Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants were clinically assessed, noting the history of pressure sensation in the ear, problems with pressure equalisation in the ear and relief of symptoms with Valsalva's manoeuvre. Past treatment history was recorded, including previous ear surgery; all patients had previously undergone grommet insertion for treatment of otitis media with effusion.

The seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire was used to quantify the Eustachian tube dysfunction symptoms (Appendix I).Reference McCoul, Anand and Christos 12

The clinical assessment included a complete ENT examination with otoscopy, Valsalva's manoeuvre and tympanometry, audiometry, and radioallergosorbent allergy testing. Patients underwent computed tomography (CT) scanning of the temporal bone to rule out an aberrant carotid artery.

All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Ethical approval was given by the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands and the Black Country, UK.

Tuboplasty method

All balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty procedures were performed by a single surgeon (DR). The procedures were performed as day cases. Under general anaesthesia and endoscopic visualisation, a Bielefeld balloon catheter (Spiggle and Theis, Overath, Germany) was inserted transnasally into the nasopharyngeal ostium of the Eustachian tube. The catheter was advanced 3 cm into the Eustachian tube. The balloon was inflated with saline to 10 atm (1013 kPa) for 120 seconds inside the cartilaginous part of the Eustachian tube. At 10 atm, the balloon had pre-defined dimensions of 2.0 cm in length and 3.28 mm in diameter. After 120 seconds, the catheter was deflated and removed. The orifice of the Eustachian tube was inspected for any evidence of trauma or bleeding.

Post-procedure follow up was carried out at three to nine months. Audiometry and tympanometry were performed, and the seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire scores were obtained.

Statistical analysis was carried out with the student t-test using Microsoft Excel™.

Results

Eleven patients (9 males (81.8 per cent) and 2 females (18.2 per cent); a total of 13 ears (2 bilateral cases)), with a mean age of 42.5 years, were recruited between June 2013 and June 2015 (24 months). These patients underwent balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty; 18.1 per cent (2 out of 11) underwent procedures on the left side, 66.6 per cent (7 out of 11) underwent procedures on the right side and 18.1 per cent (2 out of 11) had bilateral procedures. Demographic data for the patients are shown in Table II.

Table II Patient demographics

Symptom duration was between 14 and 86 months (mean of 45 months). All patients had previously undergone grommet insertion for the treatment of otitis media with effusion. The grommets had extruded and the patients’ symptoms had recurred or persisted. All patients experienced aural fullness of different magnitudes. Seventy-two per cent had muffled hearing, 56 per cent had otalgia and 36 per cent had tinnitus. All patients had a dull, retracted tympanic membrane on otoscopy. The patients showed mild-to-moderate conductive or mixed hearing loss (hearing threshold between 25 and 55 dB). All patients had previously been treated with topical decongestant, nasal steroids and grommets. No bony carotid canal dehiscence was found on CT. Radioallergosorbent blood testing showed evidence of aeroallergen allergy in 75 per cent of patients (Table III).

Table III Allergy test findings

*Normal level = less than 5 per cent; †normal level = less than 115 kU/l. RAST = radioallergosorbent test; IgE = immunoglobulin E

The surgery was uneventful and all patients were discharged from hospital on the same day as surgery. There were no complications (bleeding or damage of regional mucosa) during or after the procedure in any of the patients.

Statistical analysis (t-tests) did not reveal significant differences between pre- and post-operative average pure tone audiometry (average of 1, 2 and 4 kHz; p = 0.2) or tympanometry (p = 0.4) (Table IV). There was a statistically and clinically significant improvement in the mean seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire patient symptoms score of 14.3 (the mean score decreased from 28.3 to 14.0; p < 0.001) (Table V).

Table IV Pre- and post-operative tympanometry results*

* There was no significant difference between pre- and post-operative tympanometry (t-test p = 0.42). †Normal range = 0.3–1.6 cm3; ‡normal range = −200 to + 50 daPa. No. = number; pre-op = pre-operative; post-op = post-operative; SD = standard deviation

Table V Pre- and post-operative eustachian tube dysfunction questionnaire data*

* There was a significant difference between pre- and post-operative Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire scores (t-test p < 0.001). †Minimum score = 7, maximum score = 49. Symptoms are proportional to scores: a score of 7 indicates better Eustachian tube function compared to a score of 49. No. = number; pre-op = pre-operative; post-op = post-operative; SD = standard deviation

Subjective post-operative improvement of symptoms (aural fullness) was perceived by seven patients (63.6 per cent) at one week, three patients (27.3 per cent) at two months and one patient (9 per cent) at six months post-operatively. Aural fullness sensation completely disappeared in 10 patients (91 per cent) at 6 months post-operatively. All patients felt that the procedure was beneficial.

Discussion

The Eustachian tube is a complex osseocartilaginous connection between the protympanum and the nasopharynx. It has three main functions: to protect the middle ear from sources of disease, to ventilate the middle ear and to help drain secretions away from the middle ear.

The diagnostic criteria for Eustachian tube dysfunction have not been universally agreed. These may include subjective and/or objective criteria. Subjective symptoms associated with Eustachian tube dysfunction include hearing loss, ear fullness, otalgia, an inability to equilibrate middle-ear pressure, tinnitus and vertigo.Reference Randrup and Ovesen 13 Objective features include hearing loss on pure tone audiometry, negative pressure or reduced compliance on tympanometry, chronic otitis media with effusion, atelectasis of the tympanic membrane, adhesive otitis media, perforation, and cholesteatoma.Reference Seibert and Danner 15

Eustachian tube dysfunction is a frequent diagnosis in otolaryngology practice, even if common diagnostic criteria are lacking.Reference Randrup and Ovesen 13 Studies in children and adults demonstrate that Eustachian tube dysfunction is present in up to 70 per cent of patients undergoing tympanoplasty for chronic otitis media or cholesteatoma.Reference Choi, Han and Chung 4 , Reference Todd 16

In patients with objective Eustachian tube dysfunction, structural and functional abnormalities may exist, including upper respiratory tract infection, chronic sinusitis, allergic causes, adenoid hypertrophy, reflux, a reduced mastoid air cell system, cleft palate and so on.Reference Wullstein 17 Some patients with subjective symptoms suggestive of Eustachian tube dysfunction have no objective abnormalities.

Subjective quantification of Eustachian tube dysfunction usually involves the use of patient questionnaires. These include the seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire used in our study. This was developed to provide a disease-specific subjective symptom score, but has not yet been used extensively. McCoul et al. identified the sensitivity (100 per cent) and specificity (100 per cent) of the seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire, and determined Eustachian tube dysfunction as corresponding with a mean score of 2.1 or above.Reference McCoul, Anand and Christos 12

Objective measurement of Eustachian tube function can be achieved using a number of different methods. These include the semi-objective Toynbee and Valsalva's manoeuvres. When the tympanic membrane is intact, various Eustachian tube function tests can be used, including Bluestone's nine-step test, the microflow technique, impedance audiometry, sonotubometry, sequential scintigraphy, microendoscopy and pressure measurements using a balloon catheter in the cartilaginous Eustachian tube.Reference Bluestone and Jerger 18 When the tympanic membrane is not intact, the forced-response test may be used.Reference Cantekin, Saez, Bluestone and Bern 19

Some Eustachian tube dysfunction measurements combine subjective and objective criteria. The Eustachian Tube Score and its extension the Eustachian Tube Score-7 combine subjective measures (clicking sound when swallowing, Valsalva's manoeuvre) and objective measures (tubomanometry, tympanometry) of Eustachian tube function.Reference Schilder, Bhutta, Butler, Holy, Levine and Kvaerner 2

Eustachian tube dysfunction can be a self-limiting condition and require no intervention in some patients. Self-administered manoeuvres such as Valsalva's manoeuvre against a closed nostril can help some patients. Devices such as the Otovent™ or Earpopper™ can also be used. Medical treatments include decongestants, antihistamines and corticosteroids.Reference Gluth, McDonald and Weaver 20

Surgical interventions include surgery either directly on the Eustachian tube, on the area adjacent to the Eustachian tube or on the tympanic membrane. Tympanostomy tube placement can equalise middle-ear pressure, and alleviate tympanic membrane retraction, atelectasis and/or effusion. Adenoidectomy with grommets can be considered in patients with symptoms that may be contributing to Eustachian tube inflammation or interfering with tubal dilation.Reference Gates 21 , Reference Nguyen, Manoukian, Yoskovitch and Al-Sebeih 22

Procedures on the Eustachian tube apparatus include direct surgery to widen the osseous Eustachian tube, and microdebrider or laser procedures to the Eustachian cushions.Reference Zollner 23 – Reference Kujawski and Poe 25

Catheterisation of the Eustachian tube was first described by a Parisian, Deleau, in the early part of the nineteenth century, for diagnostic purposes and in an effort to improve hearing.Reference Politzer 26

Eustachian tube dilatation has been attempted as a treatment for Eustachian tube dysfunction. In a small study by Miller, in 1970, 13 children with tympanostomy tubes in place had a small Foley catheter inserted into the Eustachian tube.Reference Miller 27 The ability to equilibrate applied negative middle-ear pressure during swallowing was assessed in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Of these children, five responded to the treatment, but none responded to the placebo.

Balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty via the nasopharyngeal opening of the Eustachian tube is a novel approach designed to treat the underlying cause of Eustachian tube dysfunction. This minimally invasive intervention aims to dilate and open the cartilaginous part of the Eustachian tube. Customised Eustachian balloons (using the Bielefeld balloon catheter; Spiggle and Theis) were used clinically for the first time in February 2009 after extensive preliminary tests.Reference Ockermann 28 The technique has since been adopted by more than 110 ENT departments in Europe.

Ockermann et al. were the first to describe the use of balloon dilatation Eustachian tuboplasty in Eustachian tube dysfunction patients, in 2010.Reference Ockermann, Reineke, Upile, Ebmeyer and Sudhoff 3 The underlying treatment mechanism has not yet been identified, but it is hypothesised that submucosal micro-haemorrhages from the applied pressure cause fibrosis and expansion of the internal Eustachian tube diameter during healing.Reference McCoul and Anand 29

Symptoms of ear blockage and pressure have traditionally been ascribed to Eustachian tube dysfunction. Similar symptoms are, however, also present in a number of other conditions, including Ménière's disease, primary pain disorders and temporal mandibular joint disorders. Five per cent of those with objective evidence suggestive of Eustachian tube dysfunction have no subjective features.Reference Elner, Ingelstedt and Ivarsson 30

As there is no universally agreed diagnostic criteria and our understanding of the pathological processes is incomplete, patients diagnosed with Eustachian tube dysfunction are likely to be a heterogeneous group, and may comprise cases of atypical Ménière's disease, temporal mandibular joint disorder, Eustachian tube dysfunction and/or possible co-existence of these conditions. The pathological processes in these conditions are also poorly understood. It is possible that a Ménière's disease patient may be more symptomatic if their Eustachian tube is unable to equalise pressure. Some treatments used for Ménière's disease affect middle-ear ventilation, including grommet insertion and the Meniett® device. It is uncertain whether these treatments have a placebo effect, an unclear therapeutic but non-specific effect from surgery, or whether improvement in middle-ear ventilation is the key aspect.

In our study, we assessed the effects of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty on chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction. Our patients had previously been treated medically and surgically with grommets. Their symptoms had recurred after grommet extrusion or were not improved with grommet insertion. Furthermore, their Eustachian tube dysfunction symptoms were chronic. The main observation was the discord between subjective and objective outcomes. There was a significant improvement in patients’ seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire symptom scores, whilst objective outcome measures including tympanometry and pure tone audiometry did not improve significantly. Our study numbers were small, but there was a trend towards improvement in audiometry. The difference may become significant in a larger sample study.

-

• Abnormal Eustachian tube function can contribute to middle-ear disease pathogenesis

-

• Eustachian tube dysfunction is a poorly defined condition, with subjective and objective features

-

• Balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty efficiency was studied in patients with chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction

-

• Objective outcomes were not significantly improved, but subjective outcomes and symptoms were

-

• The objective abnormality and subjective symptoms in Eustachian tube dysfunction may represent two distinct pathological processes

One potential interpretation of our results is that the objective abnormalities often ascribed to Eustachian tube dysfunction are not themselves causing the symptoms. The objective abnormality and subjective symptoms may represent two distinct pathological processes, which may nevertheless influence and exacerbate each other. This is akin to respiratory and cardiac disease in a patient with breathlessness. Some studies on balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty have shown both objective and subjective improvements in Eustachian tube dysfunction measures.Reference Jurkiewicz, Bien, Szczygielski and Kantor 14 However, the objective improvements may not be required to yield subjective improvement.

To clarify these issues, future research needs to investigate the pathological processes and diagnostic criteria of patients with Eustachian tube dysfunction. The objective and subjective effects of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty must be studied independently in a blinded, randomised controlled trial, to eliminate natural disease course and placebo effects.

Conclusion

We have presented the results of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty in patients with chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction. We were unable to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in the objective outcome measures of tympanometry or pure tone audiometry. We did, however, find evidence of subjective improvements in symptoms with the seven-item Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire, and all participants felt that the procedure was worth undergoing.

Appendix I Eustachian tube dysfunction questionnaire