The curtain rose at the King's Theatre, Edinburgh, on 14 August 2011 to reveal a richly textured production of The Tempest on a bare stage with minimal props. As the lights came up, a group of white-robed sailors were caught in a meticulously choreographed storm, dancing to the mesmerizing beats of the master drummer upstage. The performers’ costumes echoed traditional Korean hanbok attire and their acting style incorporated t'alch'um mask-dance drama techniques. Their long white sleeves flapped and swayed in sync with their movements. Engulfed in stagewide sapphire and then crimson lighting, their sleeves were transformed from symbols of violent wind and waves to raging fire on board a ship approaching a world where, as Gonzalo aptly summarized, “no man was his own” (5.1.211). With Prospero (King Zilzi) as the drummer upstage and Ariel dancing in the midst of the unfortunate sailors, the storm scene—one of the longest renditions of the “direful spectacle” (1.2.26) in the performance history of The Tempest—served as an anchor to the tragicomic narrative about the self and the other. For a fleeting moment, Prospero gave the impression of being a drillmaster at the helm.Footnote 2

The drumming patterns and kinetic energy from the opening scene were carried over to the rest of the play. It became clear that this production was governed by an unpretentious and powerful visual language. As the play unfolded, the stage was transformed into a rice field symbolized by six broomsticks, a space inhabited by animals and indigenous island creatures. The well-received production in Edinburgh echoed what Virginia Vaughan, editor of the Arden Tempest, has described as a “theatrical wonder cabinet.”Footnote 3 Befitting the overarching theme of Shakespeare's late plays, this island off the medieval Korean shore offers exotic spectacles, sounds, and new discoveries. The Shakespearean play with a Western narrative structure helped a company tell their story through the performers’ Asian bodies on a global stage, though the structures of the play and stage scripts and the acting methods are not exclusive to any one region of the world. Just as the disoriented Viola, who is washed ashore in act 1, scene 2 of Twelfth Night, we are compelled to ask: “What country, friends, is this?” In the comedy, the captain provides a seemingly straightforward answer: “This is Illyria, lady,” that being an ancient region in the Balkans along the Adriatic coast, a region familiar to early modern London audiences.Footnote 4 We have no such luck with touring productions that tack on transhistorical and evolving cultural locations, both imaginary and real. Touring productions create a heterotopia and sometimes a state of delirium as the name Illyria suggests.

A play born at the dawn of British colonialism and inspired by “the wreck of a ship bound for Virginia,” as Michael Dobson reminded the audience in the program,Footnote 5The Tempest, directed by Oh Tae-suk of Mokwha Repertory Company (Seoul), was reimagined in the vein of the twelfth-century epic The Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk Sagi), one of the most canonical narratives about fifth-century Korea.Footnote 6 Recast as a vexed character capable of recognizing his own limitations, Prospero was often challenged by the spiky-haired Miranda and worked closely with Ariel, a shaman, to manage domestic affairs. Ariel sometimes assumed a motherly role to augment the aging father's tenuous relationship with his teenage daughter. The production deliberately lagged temporally. Its dilation of temporality hinges on a fictional ancient Korea created by Oh and his team, a past that is durative and open-ended. The performance ended on a high note. Instead of a staff and books—symbols of authority and the archival source of knowledge in an ontological sense—Prospero carried a folding bamboo fan (hapjukseon)—a symbol of artistry and intellectualism—when he was not at the drum.Footnote 7 The folding fan is an integral part of a gentleman's accessories and is a more versatile prop and powerful symbol than books. It can be used to create a cool breeze but it can also be used as a screen to hide its holder's face, as a daggerlike weapon, and as an important prop in stylized p'ansori music theatre (two-person operetta). In the final scene, Chung Jin-gak's Prospero was alone onstage. He folded his fan and asked the audience tentatively whether the “magic [he had] made with this fan [had] given [them] happiness.”Footnote 8 Once the audience clapped in approval, he descended from the stage and handed his fan to an audience member. The audience was thus offered a passionate portrayal of a single father who happens to be an artist eager to pass on his “magic.” Outside the dramatic context, the fan served as a gesture of the company's good will and as a mnemonic device. The production, which premiered in Seoul in 2010, received the 2011 Herald Angel Award in Edinburgh.

Performing Shakespeare in Asian theatrical styles and manufacturing Asianness through Shakespearean theatre—a reciprocal process that I refer to as Asian Shakespeares—has generated incredible artistic and intellectual energy. Perceived in many parts of East Asia as a modern figure, Shakespeare operates as a transhistorical brand. Theatrical transnationalism often collapses temporal and spatial dimensions of artworks—in this instance fifth-century, seventeenth-century, and twenty-first-century frameworks for understanding Shakespeare, the Korean Peninsula, and the British Isles. The reception of this collision of time and space reflects the unequal power relations that have been naturalized by the canonicity of dramatic works or genres. As one of the “Eastern-themed” Edinburgh International Festival's (EIF) three prominent Asian performances of Shakespeare, Oh's Tempest raised important issues of agency and efficacy. The EIF featured several genres of Asian performing arts ranging from theatre to ballet, including works by the Seoul Philharmonic and the Yogyakarta Palace Gamelan Orchestra, The Revenge of Prince Zi Dan (based on Hamlet) by the Shanghai Peking Opera Troupe, Lear Is Here by the Contemporary Legend Theatre of Taiwan, The Peony Pavilion by the National Ballet of China, and Haruki Murakami's The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in English and Japanese, directed by Stephen Earnhart. Why was Oh's Tempest judged by British critics to be a successful piece of touring theatre, while other adaptations of the Western canon—which were no less high profile in their Asian contexts, such as Wu Hsing-kuo's solo performance of Lear—did not quite “work”? Through their exemplary power, the intersections of Asia and Shakespeare provide a set of important issues for repositioning theatre studies in the wider field of globalization studies. As scholars and artists have imported ideas and exported their works across national borders with greater frequency, they have become more self-aware of their practices and spectators within local and global communities, as evidenced by recent publications that take stock of the theatricalization of globalization.Footnote 9 How does Shakespeare make Asian theatre legible in the British context? What roles have Asian performance styles played in the rise of Shakespearean theatre as a “global” genre and to postimperial British identity in the world? More specifically, what does it entail for Asian theatre artists to perform Shakespeare in Britain and for the British press to judge these touring productions?

These are some of the questions that artists and audiences of Asian Shakespeares have to confront. The following analysis of British reception of intercultural Shakespeare performances over the past decades showcases the dilemma and fantastic character of global Shakespeares on tour, on the one hand, and, the opportunity, on the other, to use touring performances to interrogate Asian and Shakespearean idioms as cultural signifiers in theatre historiography. Asian performance styles are highlighted here because of their increasing prominence at recent international festivals.

Double entendres: intercultural negotiations

Touring theatre is a place where theatre studies and globalization come into contact. I have offered broader metacritical interventions elsewhere, and here I would like to focus on the production and reception of Shakespeare and Asianness in postnational spaces—festival venues where national identities are blurred by the presence of such entities as transnational corporate sponsors.Footnote 10 Some of these touring theatre works are produced under circumstances that may prove challenging or alienating to even the most cosmopolitan audiences. Asian Shakespeares outside Asia and in the diaspora put pressure on some of the theoretical models theatre historians have privileged in their documentation of the Western sources of non-Western performances. We might stay aloof and distrust any intercultural ventures because they are inevitably fraught with colonial mentality, as Rustom Bharucha does in his criticism of intercultural theatre practice.Footnote 11 However, I suggest that the alienating experience serves important sociocultural and aesthetic functions, and capturing the experience as it unfolds in its shifting cultural location can help us move from narratives driven by political geographies to histories informed by theatrical localities—the variegated locations embodied by touring performances. Global cultural flows are an organized and intensified cluster of activities that thrive on multidirectionality. As Fredric Jameson puts it in his working definition, globalization is “an untotalizable totality which intensifies binary relations between its parts.”Footnote 12 Select cultural values are often ascribed to Asia. They are set against values associated with Shakespeare when Shakespearean characters are translated into palpable flesh-and-blood performers who may or may not be recognizable figures to the audience—for example, Kalamandalam Padmanabhan Nair's stylized Lear in the Kathakali dance drama adaptation at the London Globe in 1999.

The European tour of Oh's production and its reception embody several recurrent themes in touring performance. First, the cultural and political conditions of a venue or a production intervene in reception and undercut the work of artistic intent. This genre of stage works is shaped by forms of agency that are not rooted in intentionality. Second, in Shakespearean performance, language is often granted more agency than the materiality of performance, leading to the tendency to privilege certain modernized and editorialized versions of Shakespearean scripts and their accurate reproduction in foreign-language performances. The humanities over the past century have witnessed the so-called linguistic turn, the semiotic turn, and the cultural turn, all of which operate on assumptions about the substantial and substantializing power of language as opposed to the materiality of cultural representation. As opposed to other forms of embodiment, language as a marker is deeply ingrained in identity politics. Language is a tool of empowerment to create solidarity, but it can also be divisive at international festivals where audience members who do not have access to the immediacy of the spoken language on stage might feel alienated or excluded. Third, Shakespeare productions that tour to the United Kingdom reflect shifting locational terrains of performative meanings that—unlike nationalist imaginations of Shakespeare—do not always correspond to the performers’ and audiences’ cultural affiliations. The systemic mutations in the politics of cultural production and compression of time and space engender variegated, layered subject positions. Oh's works on tour are anything but typically Korean in style and theme. Other directors also make revisions to accommodate the performance space and audiences of international festivals, dictated by the cultural prestige of the exporting nation. Feng Gang, who wrote The Revenge of Prince Zi Dan, a jingju (Beijing opera) adaptation of Hamlet, told the Daily Telegraph that he and his colleagues “designed this play for foreign audiences.” While it would be ideal to take traditional jingju plays overseas, he added, they would be “incomprehensible to foreigners” no matter how “eye-catching” the performance might be.Footnote 13 In contrast, the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC)—occupying a more privileged position in the Shakespearean circle—does not usually localize its productions for the purpose of international tours (e.g., Ian Judge's The Comedy of Errors in Taipei in 1993, Lindsay Posner's The Taming of the Shrew in Taipei in 2000, and Loveday Ingram's The Merchant of Venice, starring Ian Bartholomew, in Beijing and Shanghai, 2002).

These three issues of politics, language, and performative cultural affiliations informed the reception of Oh's Tempest. The production was capable of restoring a sense of wonder because Oh concocted a fictional ancient Korea through his antiquated, hybrid style that was unfamiliar to the Korean expatriate, British, and international audiences in Edinburgh. The sheer energy of its musical and physical expressions of a wide spectrum of emotions effectively bridged the gap between this Korean production and an audience that was accustomed to a more Anglo-European flair and was more familiar with a modern, Westernized Korea. The spoken language (Korean) and textual presence of English surtitles further demarcated the actors’ and audiences’ discrete linguistic communities. In this ninety-minute production, the spoken language involved a great deal of elision and often omitted subjects. While the emphasis on visual signifiers may seem at first to be a strategic move to enter global circuits of cultural production by way of touring from a marginal location, the abbreviated phrases that omitted verbs or nouns were in fact necessitated by the acting style. The actors wore masks to perform physically demanding dance pieces and movements, and as a result could not speak full lines simultaneously, though the English surtitles offered deceivingly complete speeches translated and rewritten to serve British and international audiences.

One of the most refreshing features of the production was its attempt to create an enchanted isle full of noise but not politics. With a liberal sprinkling of humor, Oh's version of The Tempest shifts the focus away from the almost de rigueur postcolonial approach to Caliban's struggles against Prospero to the tension between Prospero and Miranda. This Prospero seems more interested in moral and artistic agency and harmonious domestic affairs than in regaining political power. It is notable that Oh chose to depart from the postcolonial angle that has been perceived to be universal. Buoyed by postcolonial critical traditions and such prominent works as Aimé Césaire's Une Tempête (1968), The Tempest has been institutionalized as a de facto postcolonial intervention and has become one of the most widely deployed canonical plays in revisionist allegories of local empowerment and anticolonial narratives. Beyond Anglophone performances, Caliban's language becomes even more powerful when the play is redacted in different languages, some of which have closer ties to Western colonial practices (such as Spanish) or Asian colonialism (such as Japanese) than others (such as Mandarin Chinese).Footnote 14

The overworked allegory can fail onstage, depending on the context. An example is the 2009 pan-African Tempest coproduced by the RSC and Cape Town's Baxter Theatre Centre, directed by Janice Honeyman. In this allegory of colonialism, Antony Sher's white, dominant Prospero had John Kani's black Caliban—who bears traces of a South African shaman—on a tether, but in the final scene, Prospero delivers the epilogue to Caliban as an acknowledgment of his crimes. Shakespearean scholar Anston Bosman, a South African native, argues that the production “signaled the exhaustion of The Tempest as a vehicle for that allegory and the urgent need for South African theater, now fifteen years into democracy, to appropriate Shakespeare in freshly imaginative ways.” Bosman mused that the tired allegory notwithstanding, the production, with its dramatis personae precisely keyed to “the complex ethnic patterns of South African society,” could “easily be the winner of a competition whose challenge was to create the perfect specimen of a ‘glocal’ Shakespeare production.”Footnote 15 However, when this production went on tour “on the global stage,” it received more favorable reviews in Britain. The worthy and politically correct allegory about the Third World was recruited to help British critics justify enjoyment of the African carnival. Kate Bassett found Prospero's final speech “universally poignant,” and Michael Billington was struck by how the performance's combination of “racial politics with visual playfulness liberate[d] this all-too-familiar play” and turned it into “a deeply moving cry for forgiveness of the colonial past.”Footnote 16 In his analysis of the divergent British and South African responses to Honeyman's production, Bosman locates the overseas success of the performance in its apolitical nature: the production is “political only in the most predictable sense—as a call for anticolonial insurrection and indigenous self-governance—which, in 2009, is no longer very political at all.”Footnote 17

Oh Tae-suk took a completely different approach to the questions of agency, coloniality, and the play's political undercurrents. For a company from South Korea, one option seems to be using the dramatic material to launch topical discourses about the not-so-distant history of Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1910–45) and the complicated emotional and political relationships between contemporary Korea and Japan. After all, the traditional theatre ch'anggŭ k (an opera form) and national history of Korean tend to draw their energy from a narrative that focus on “resistance to foreign penetration”; so a play such as The Tempest might work well for Oh's project of constructing and popularizing traditional Korean values.Footnote 18 However, Oh focused on the revitalization of traditional Korean aesthetics, a story whose subtlety is unfortunately lost to the British press. Oh, the founder and artistic director of Mokwha Repertory Theatre Company (founded 1984), began playwriting in 1968. Similar to his Tempest, his more than sixty original plays are rooted in Korea's cultural archetypes. He has established a unique theatre methodology based on traditional Korean aesthetics, language, and expressions. His Romeo and Juliet toured to the Barbican Centre in 2006.

Oh's extensive international touring experience has given him a unique vantage point. Opening with the music of the taegŭm, a horizontal Korean bamboo flute, Oh's production evoked Korean myth, music, and the Confucian tradition. Throughout the storm scene, music that drew on rural Korean percussion styles provided the rhythmic foundation for the actions, and some characters such as the spirits took on animal roles, echoing the traditional mask-dance drama t'alch'um. Oh transformed The Tempest into a romantic comedy. The Daoist magician King Zilzi (Prospero) rules the island and orchestrates the shipwreck out of revenge, but he brings the men to his island partly because it is high time his fifteen-year-old daughter “met somebody.” The Korean Miranda later reminds her suitor that the question about her purity is preposterous; after all, she has grown up on “a desert island.” Oh's version is not exactly a rollicking comedy, but it extrapolates something extraordinary from both the Elizabethan genre of romance and the Korean tradition of hybrid theatrical genres (such as ch'anggŭk and the masked dance drama kamyŏ n'guk). The production shows a new path through Shakespeare's material and The Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms that restores the comedic elements with a sense of “lightness and wit.”Footnote 19 Oh is more interested in establishing a space of his own in the teeming global cultural marketplace than he is in speaking on behalf of nations. A similar strategy was adopted by another Asian Tempest that recently toured to Britain during the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival at the London Globe. Nasir Uddin Yousuff's Bengali adaptation steered clear of postcolonial angst to embrace a colorful and vibrant comedy. Folk dance and Bangladeshi songs framed much of the action, and Prospero's charms were evoked by Manipuri drummers with double-headed hand drums.

For good reason, Western critics are often more attentive to works that criticize global inequalities, but the European premiere of Oh's Tempest demonstrates that productions that are critical of the geopolitical status quo represent but one approach to the play. Some theatre critics could not resist the urge to read Asian performances politically or imagine necessarily political agendas in these works. Toward the end of the production, the spirits ask the Prospero figure to liberate them from years of servitude and, in a surprising turn, add that they wish to be turned into ducks so that they can “go sightseeing in the north.” Along with the Chronicles’ teleological view of an eventually unified kingdom of Korea and the fact that Oh's company comes from South Korea, this line opened up a can of worms in Edinburgh. At a postshow discussion at the Hub, an audience member pressed Oh about his intentions, but the director reiterated several times that he did not have North Korea or the conflicts on the Korean Peninsula in mind.Footnote 20 Although Craig Singer does not pursue the issue in his review, he does highlight the idea of a unified Korea.Footnote 21 Paul Gent is more conclusive in his assessment of the political message in this “fine pageant” (Figs. 1 and 2):

The biggest change of all, though, is that Caliban is a monster with two heads in constant disagreement. In the final scenes, Prospero grants them their freedom by splitting them—undoubtedly a reference to North and South Korea.Footnote 22

Figure 1. Ariel about to saw apart the two-headed Caliban as granted by Prospero in Oh Tae-suk's The Tempest, Edinburgh, August 2011. Courtesy of Mokwha Repertory Company.

Figure 2. The two-headed Caliban separated and freed by Prospero in Oh Tae-suk's The Tempest, Edinburgh, August 2011. Courtesy of Mokwha Repertory Company.

The dynamics of British reviews of intercultural performance are symptomatic of the tendency to read contemporary Asian arts in political ways in the West. The patterns in the reception history of touring productions also point toward a lingering ideological investment in fixed notions of cultural authenticity. We have excellent histories of individual theatrical traditions, but touring productions have remained unclaimed goods outside of journalistic discourses. While there are in-depth studies of national Shakespeares, the same cannot be said of the history of performances imported from one region into another, partly because of the sheer multiplicity of cultural and political variables.Footnote 23

Headlines about Asian countries converge on the notion that politics in Asia dictate cultural life, a notion that leads to routine praise and the expectation of dissident, subversive, or political undertones in Asian theatre. Stories of oppression must be told, and indeed some Asian performances strive to make known the unspeakable acts. However, other cultural stories must also be told. Oh's comedic presentation also poses some obstacles. In his otherwise positive review, Mark Fisher writes that the “playful” adaptation is better for its lack of depth, because it is “the kind of thing you can imagine appealing to the groundlings in the Globe.”Footnote 24 Other critics go through a laundry list of parallels and departures from Shakespeare, noting that it is “hard for a British audience not to feel that Shakespeare's play has been diminished” and that the “greatest loss … is the word-magic.”Footnote 25 Many of the journalistic discourses about the production and interviews with the director focused on how the thematic parallels and transhistorical connections suggest palatable compatibility between Shakespeare's and Oh's visions of dramatic spontaneity that creates more with less by inviting the audience to “deck [their] kings” with their thoughts (Henry V, Prologue, 29). Gent reverts to the crude convention of authenticity in which performances of Shakespeare in English must necessarily be more effective onstage. He writes that “the poignant and troubled relationship between Prospero and Ariel … goes for nothing” in the Korean rewriting. He is right that the “acting style” of “one-note declamation”—a departure from psychological realism—may take some getting used to, but his reaction to the production as a whole suggests that when confronted with unfamiliar works, critics often use various versions of Shakespearean regionalism and cultural ownership as anchor points.Footnote 26

All this is a result of a complex network of cultural exchange that makes the paradigm of West to East, North to the Global South, or any “built to order” model meaningless, though some critical studies of Asian Shakespeares continue to emphasize the issue of compatibility between different theatrical traditions and marvel at the ease with which Asian performance idioms cross borders. They seem to suggest that Asian Shakespeare performances are valuable because they are “collectively distinguished … by the force of their visual, aural, and corporeal strategies … and can be enjoyed, irrespective of how well one understands them.”Footnote 27 Other works, such as The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare, are guided by a priori criteria (such as “innovation” and “influence”) that exclude the likes of Suzuki Tadashi.Footnote 28 When Shakespeare's plays are performed with Asian motifs (either by Asian or Western artists), they form a body of work that defies existing conventions based on divisions of cultures according to the boundaries of nation-states. Similar to the response to Honeyman's production on tour in Britain, the reception of Oh's production compartmentalizes the politics and aesthetics of The Tempest in racialized terms based on nation, culture, and the British relations with North and South Korea.

These articulations of difference and sameness are constructed in terms provided by Anglophone theatre historiography. As geopolitically situated citations of other Shakespeares and other Asias, these touring productions and how they are received reveal the unequal power relations naturalized by values associated with the Western canon. To combat the predictable expectations of topicality, Oh uses Shakespeare to revive a sense of traditional Korea that is distant even to his hometown audience and to polish his signature style of bringing contemporary sensibilities to bear on traditional aesthetics.Footnote 29 Ultimately, what is at stake is not how best to preserve Shakespeare's text but how to reconnect Oh's Korean audience with the lost realm that is traditional Korea.Footnote 30 His production of The Tempest not only sharpens but also expands our auditory sense of the Shakespearean and Korean texts at work.

World Shakespeare festival and globe-to-globe

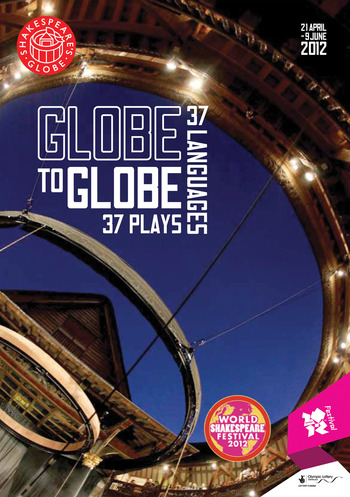

The politicized reception of Oh's Tempest is not an isolated instance. To understand the British patterns of reception of Asian performances, we must put them in a broader historical context. Organizers of the 2012 London Olympics and the Cultural Olympiad proclaimed Shakespeare, once again, the bearer of universal currency. Much more ambitious than the Royal Shakespeare Company's 2006 Complete Works festival, the 2012 Globe-to-Globe (part of World Shakespeare Festival) was an integral part of the Cultural Olympiad to celebrate the Olympics. The festival was presented by the Royal Shakespeare Company, the EIF, and the Globe to Globe program. Opened on 21 April, it brought theatre companies from many parts of the world to perform Shakespeare in their own languages (“37 plays in 37 languages”; Fig. 3) “in [the London] Globe, within the architecture Shakespeare wrote for.”Footnote 31 In fact, thirty-eight Shakespearean plays were performed in languages ranging from Lithuanian to sign language. This is arguably one of the most important festivals since David Garrick's Shakespeare Jubilee in 1769 that jump-started the Shakespeare industry and tourism in Stratford-upon-Avon. Billed as a “great feast of languages,”Footnote 32 the Olympiad season featured Rachel House's Troilus and Cressida in Maori, Nasir Uddin Yousuff's The Tempest in Bengla, Haissam Hussain's The Taming of the Shrew in Urdu, Wang Xiaoying's Richard III in Mandarin, Tang Shu-wing's Cantonese Titus Andronicus, Yang Jung-ung's Korean Midsummer Night's Dream, and Motoi Miura's Coriolanus in Japanese, among other plays. The Globe-to-Globe's website suggests that the festival “will be a carnival of stories,” including inspirational stories by companies “who work underground and in war zones.”Footnote 33

Figure 3. Cover of the program for the World Shakespeare Festival 2012. Courtesy of the London Globe.

The festival planners made choices about the languages to include in the festival and the companies to invite (usually one company for each language including Welsh, though Ninagawa Yukio's Cymbeline was staged at the Barbican and Motoi Miura's Coriolanus at the Globe), but they worked with the visiting companies to decide on the Shakespearean plays to perform. The World Shakespeare Festival, unlike the previous RSC Complete Works Festival, included almost exclusively non-English-language performances. The WSF also made an effort to cover Africa, the Americas, Russia, Asia, Europe, and New Zealand. In terms of geographical distribution during the WSF, European companies alone offered fifteen touring productions to the festival including British Sign Language performances. Asian companies offered eight productions (not counting the Maori Troilus and Cressida), African companies six, and Middle Eastern companies six. Groups from Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and the US also brought productions to the WSF. The 2012 Globe-to-Globe, a core component of the WSF, had a few conditions (“the artists will play the Globe way”),Footnote 34 including running time under two-and-a-quarter hours, synopsis surtitles, minimal stage set and technology, and no lighting. Some of these limitations are part of the unique architectural space of the London Globe and the need for quick turnaround time among 37 productions in rapid succession, but other conditions are related to the festival's goal to celebrate Shakespeare and world cultures, such as enforced linguistic authenticity, though there were a few exceptions to the ban on English on stage.

Some productions tapped into geopolitical imaginaries. To the Globe's credit, they had an inclusive policy and issued open calls for proposals. Some companies were interested in geopolitical alignment, as evidenced by the Globe's promotional language for Teatro di Roma's production: “Where else but from Rome for Julius Caesar?” Andrea Barraco's Julius Caesar touts its cultural bona fides: it is set in “a dreamlike yet contemporary Rome.”Footnote 35

Some companies approached the Globe with plays already in production. For example, Yohangza Company's (yohangza means travelers) Korean adaptation of A Midsummer Night's Dream has toured internationally to critical acclaim. The Globe also commissioned some productions, such as the National Theatre of China's Richard III. In still other instances, the Globe suggested plays for the companies to consider, and the companies’ rationales for choosing a specific play ranged from interest in creating escapist fantasies and experimenting artistically to a desire to participate in political activism. The Roy-e-Sabs Company of Kabul roundly rejected Richard II. The Comedy of Errors performed in Dari suited them better because they wanted to have a laugh amid realities of harsh Afghan politics, according to director Corinne Jaber. The themes of exile and darker aspects of the comedy were not lost on the company and their audiences. The play opens with a merchant from Syracuse telling his life story in Ephesus, where he is about to be executed for violating the travel ban between the two warring cities. Jaber's group had to rehearse in Delhi for the Globe-commissioned production after having narrowly escaped being killed in a Taliban attack on the British Council building in Kabul.Footnote 36 Ashtar Theatre of Ramallah gladly took on Richard II because, according to Globe to Globe festival director Tom Bird, the “Palestinians were desperate to tell their stories” through the Arabic adaptation.Footnote 37

Beyond international politics, the World Shakespeare Festival is also conceived of as a festival of languages that celebrates and recruits London's diverse ethnic communities, some of which have historically been marginalized. Major world languages, as defined by the number of speakers, were obvious choices, including Spanish, Mandarin, Russian, and Hindi, and languages that are important to London communities such as Bengali were also included. For 83 percent of the audience members who were members of these communities, it was their first visit to the Globe.Footnote 38

The festival at the Globe concluded in early June, but other foreign touring productions continued to arrive in Stratford-upon-Avon and elsewhere in the United Kingdom throughout the summer. Saturated with foreign-language productions, the festival was both boldly experimental and reassuringly British, anchored by the production that both closed the festival and opened the Globe's own season: Dominic Dromgoole's English Henry V, which, according to the Globe's marketing material, “celebrates the power of English, or any other language, to summon into life courts, pubs, ships and battlefields, within the embrace of ‘the wooden O.’”Footnote 39 The World Shakespeare Festival therefore served multiple purposes. First, it has successfully expanded its clientele by inviting London's ethnic communities to occupy the Globe's space. Second, the multilingual Shakespeare festival was a step toward consolidating the underdefined cosmopolitan British identity that was created at the inception of the Globe. Third, it celebrates diversity within the United Kingdom. (Welsh and British Sign Language were among the languages represented).

Finally, though, the festival was directed at the international audience who are the consumers of the South Bank's culture-driven tourism.Footnote 40 The timing of the festival coincided with the 2012 summer Olympics, and the productions were offered in a model of one play per language in quick succession (each production ran for only two to three days). This provided enough diversity to allow tourists who had come for the Olympics to see several different plays during a short stay. The Globe appealed to these particular tourists by offering packages that were named after sporting events: biathlon for two shows, triathlon for three shows, decathlon for ten shows, and Olympian for all thirty-eight shows.

“As Huge as High Olympus”Footnote 41

Both the Olympics and the Globe's festival focused on participants from many nations and on brands in promotional efforts. The parallels between sports and performance have been explored in various studies. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht attributes the fascination with watching sports to a very literal sense of aesthetic experience, namely the nature of athletic beauty. J.P. Singh argues in Globalized Arts that “creative products” can be incorporated into local and global markets to address cultural discomfort and anxieties about globalization.Footnote 42 For our purpose here I focus on national identities and Shakespeare's symbolic capital at the festival. Some visiting companies and audience members who spoke the languages the companies used in their productions saw the festival at the Globe as an opportunity to assert identity. Cultural festivals are often held before and during the Olympic Games.Footnote 43

Both the Olympic Games and the Cultural Olympiad are international events that draw a great deal of media attention and scrutiny. They share a common goal of promoting mutual understanding among countries, but they also fuel nationalism in various guises. Despite the London Globe's effort to market the international Shakespeare productions by focusing on the languages of the plays and the cities of origin of the companies rather than their countries (e.g., a Hebrew Merchant of Venice from Tel Aviv; The Comedy of Errors from Kabul), national flags appeared online and were brought onstage while enthusiastic crowds of expatriates cheered on. Similar to international sporting events, the multicultural celebration of languages inevitably fueled nationalist sentiments in various guises that ranged from political protests to celebration of independence. For instance, a 12 × 4.5-inch image of a crowd waving flags of the Republic of South Sudan (est. 2011) adorns the Globe's Web page advertising the South Sudan Theatre Company's Cymbeline in Juba Arabic.Footnote 44 At the curtain call of Dhaka Theatre's Tempest at the Globe on 8 May 2012, one of the actors appeared onstage wrapped in the Bangladeshi flag. The gesture connected an artistic achievement with national pride. More controversial were the street demonstration outside the Globe Theatre and calls to boycott the Israeli company Habima's performance of The Merchant of Venice.Footnote 45

However, unlike the Olympic Games, which focus attention on individual star athletes even when they participate in team sports, the World Shakespeare Festival at the London Globe seemed to have sidelined individual artistic identities: the festival promoted a Bengali Tempest (rather than a Tempest directed by Nasir Uddin Yousuff), a Turkish Antony and Cleopatra (rather than director Kemal Aydogan's production), and so on. It is not always easy to locate the names of participants and further information in English about the director and cast. The Globe did away with programs altogether and instead provided a bilingual leaflet for each production that provided only scanty information. The same is true of their Web site. By contrast, much more information is readily available for the Royal Shakespeare Company's or the Globe's productions in English. The Globe's strategy of emphasizing the languages of the productions (Fig. 4) suggests that the main selling point is national or political Shakespeares rather than the backstories of artists, for which festival audiences may not have patience.

Figure 4. Cover of the lecture series program for the World Shakespeare Festival 2012. Courtesy of the London Globe.

Boomerang Shakespeare comes home

Prominent in the marketing language of the World Shakespeare Festival (of which Globe to Globe was a part) was Viola's aforementioned question in Twelfth Night, now made rhetorical: “What country, friends, is this?” appears with an image of a marooned ship on the WSF's website to advertise the RSC's “shipwreck trilogy” (The Comedy of Errors, Twelfth Night, and The Tempest) and to serve as a tongue-in-cheek reaction to the deliciously confusing festival.Footnote 46 The idea seems to be that if each country's artists fully embody the essence of their culture, the audience would be able to tell which country it is at first blush. The Q Brother's ninety-minute hip hop Othello: The Remix was invited to represent the U.S. at the Globe. Set in modern-day U.S., the story about the reigning king of hip hop was acted and narrated by a cast of four men in jumpsuits, with a DJ up in the balcony. The production was among the first show to be sold out, and attracted a large number of young audiences.

There were moments in several productions when questions about cultural and geopolitical identities ceased to be rhetorical and became pressing in a productive way. The Belarus Free Theatre's production of King Lear was refreshing and challenging, partly because few audience members were familiar with Belarus and its culture. The facetious performance treated the play as a comic folktale that spirals into tragedy. Lear wobbled onstage with a thatch of white hair atop his slender frame, only to throw off the wig and reveal his jovial self. The play did not seem to need a Fool. The division-of-the-kingdom scene was presented as something akin to a reality TV show involving a rival striptease among the daughters. It is a different story with other troupes. When the National Theatre of China's Richard III opened at the Globe on 28 April 2012, the container that was carrying their exquisite set and costumes was still languishing on the North Sea. The Globe's support team and the Chinese actors quickly assembled substitute costumes and props from the Globe's storage room and the company pulled off a stellar, stylized performance without their full-face masks. They used simple but effective Western costumes, including Richard's red gloves, according to the conventions of the two primary styles the production employed, jingju and huaju (spoken drama). This is arguably intercultural theatre at its best, because both the hosts and visiting company turned contingencies into opportunities while on the road. Despite the overwhelming success of the performance in London, which was partly due to the effectiveness of the improvisation, director Wang Xiaoying and his crew were not entirely happy about the missing costumes and props.

While the production seems to hail from China, multiple intercultural elements indicate that it is born in a fluid, heterotopic space created by stage designer Liu Kedong. One of the most visible elements is calligraphy. The title “Richard III” is written with English letters morphed into pseudo Chinese written characters in the style of square word calligraphy pioneered by the artist Xu Bing. The letter R for example is fused with the Chinese character for human (ren) and placed on top of a triangular structure that contains the remaining letters of Richard. This is an instance where Viola's question takes on an interesting dimension. For English speakers who cared to look closely, they would realize they could actually read the writing that seemed foreign at first glance. For Chinese speakers who assumed they could claim insiders’ knowledge, they would quickly discover that the pseudo Chinese characters are inscrutable except for individual radicals and elements (such as ren) that made up the square word calligraphy.Footnote 47 During the performance in Beijing with full stage set and costumes, names of characters that would be killed by Richard appeared in the same fashion on the backdrop of the stage. Buckets of blood were poured down on the names, gradually devouring them and Richard's kingdom.

One of the contributions of touring productions and theatrical contingency is that Viola's question will be asked with increasing urgency and will prompt more reflections on cultural identities that have been taken for granted. “Shakespeare” is a canon that is supposedly familiar to educated English speakers, but it is increasingly alien to the younger generation. If the Belarusian Lear estranged Shakespeare in linguistic and artistic terms, the hip hop Othello made Shakespeare more familiar and relevant.Footnote 48 Thus, the Globe to Globe seasons and other similarly structured festivals including EIF and the Barbican International Theatre Events pitched Shakespeare as global celebrity against Shakespeare as national poet and created a new brand with contemporary currency and vitality.

Also prominent in the marketing language was the slogan “Shakespeare's coming home,” either evidence of lingering parochialism or an inside joke that riffed on a refrain in “Three Lions,” the anthem of the England football team. The song's chorus proclaims that “It's coming home, it's coming home … football's coming home,” suggesting that the honor of football comes home to England, where the modern game was invented.Footnote 49 Shakespeare seems to be a prodigal son who has traveled the world and finally returned to England.

The meaning of this “return,” however, is ambiguous. International performances of Shakespeare date back to the early seventeenth century; the practice of touring productions to international festivals is not new. What is new is the transformation of Shakespeare from a British export to an import industry and, since the 1950s, the emergence of intercultural or coproduced performances in England. As a business model and a cultural project, global Shakespeare has been used to reinforce the idea of Shakespeare as a world heritage that connects disparate local cultures. At a conference at the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon, Tom Bird told a crowd of Shakespeareans that “Shakespeare is less and less comprehensible in English, so it is good to see him working so well in translation.”Footnote 50 Likewise, Neil Constable, chief executive of the London Globe, remarked at the reception after the performance of the Hong Kong director Tang Shu-wing's minimalist Titus Andronicus on 3 May 2012 that “We don't own Shakespeare anymore here on Bankside at Shakespeare's Globe. I don't think the UK owns Shakespeare. Actually the world owns Shakespeare now.” What is left unarticulated, however, is how foreign Shakespeares have been deployed to validate and elevate the status of English Shakespeare performances, especially at a venue such as the London Globe.

Constable's remarks were part of the Globe's efforts to reach out to the ethnic and expatriate communities in greater London and to international visitors, but and the celebratory tone (“The world owns Shakespeare now”) contradicts the Globe's other message about global Shakespeare's return to England. That language has been in incubation since the construction of the modern Globe, though it was amplified during the Olympics. A playwright who belongs to the world is useful for campaigns that seek to enhance cross-cultural understanding on the playwright's home ground. The London Globe's 2010 season, entitled “Shakespeare Is German,” “celebrate[d] Germany's special affinity” with the playwright.Footnote 51 Celebrating Shakespeare's affiliations with world cultures in London carries special cultural and political meanings. As part of the festival, the German actor and director Norbert Kentrup, who was the modern Globe's first Shylock in 1998, discussed his experience performing in Shakespeare's plays in English and in German. The Guardian enthused that the season was an opportunity for the audience to rethink Shakespeare: “We tend to think of William Shakespeare as wholly ours. But Stratford's greatest son has a rival fan club across the North Sea.”Footnote 52 Cosponsored by the Germany Embassy in London within the framework of its “Think German” campaign to promote German culture, the season created an avenue of self-knowledge and understanding of foreign cultures within a relatively familiar framework. Sabine Hentzsch, director of the Goethe-Institut London, proudly cited the fact that the Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, one of the first Shakespeare societies in the world, was founded in 1864 in Weimar.Footnote 53 Similarly, in the context of the 2012 London Olympics, Shakespeare as an icon in a postnational age was made to work in domestic and foreign affairs.

The worldwide diffusion of Shakespeare's plays (Fig. 5) in ever-more-complex networks of exchange has made the division between national and foreign Shakespeares a moving target. Although World War II and the Cold War helped formalize binary oppositions of many kinds, setting select Western powers against the Soviet bloc, Shakespeare's global career is far from a simple story of colonial expansion and postcolonial reorientation. In 1957, one Chinese commentator remarked that “Shakespeare's real home is in the Soviet Union,” despite knowledge among the Chinese that Shakespeare was a British cultural icon.Footnote 54 It is worth noticing that the formation of global Shakespeare is not a linear process of transmission from Shakespearean texts to foreign-language performative texts and back to English surtitles as part of tours or coproductions in Britain. The plays often take winding routes through various performance traditions and cultural marketplaces. Ideological and artistic requirements and marketing considerations further complicate the picture. Significantly, the dissemination of Shakespeare was “not coextensive with the advance of English” as a colonial or global language.Footnote 55 In some instances, Shakespeare's text was relegated to the backstage. East Asian cultures first encountered Shakespeare through local translations of Charles and Mary Lamb's Tales from Shakespeare (1807), a Victorian prose rendition of select comedies and tragedies.Footnote 56 Even Shakespeare's fortunes in colonial India are far more complex than postcolonial criticism tends to allow. As Poonam Trivedi usefully points out, “while the study of the English language and Shakespeare [in India] was an imperial imposition, the performance of Shakespeare was not,” because he was regarded first and foremost as an entertainer and was not necessarily connected with English values.Footnote 57 Other similar stories of multiple levels of filtering demonstrate that cultural exchange did not occur in a hub-and-spoke paradigm. I will not belabor the point here, since the history of worldwide transmissions of Shakespeare is well documented and readily available.

Figure 5. “The biggest celebration of Shakespeare starts now,” proclaimed a promotional trailer for the World Shakespeare Festival 2012.

With such a complex history, it is only fitting that when transnational performances finally arrived in Britain in full force, they came under many different guises and in all stripes. Performance styles borrowed from other cultures can help retool some plays and aid directors in search of new values. British directors began employing hybrid performance styles as early as the 1950s; Peter Brook is a notable example. A director who regarded theatre as iconographic art, Brook worked from a set of compelling images for each production as if he were a designer.Footnote 58 His Titus Andronicus (1955), starring Laurence Olivier, is one of the landmark productions that rehabilitated the play. It transformed Titus from an undervalued melodrama to a study of primitive forces that can be taken seriously. Realistic but heavy-handed portrayals of horror and violence were replaced by abstract, elegant, Asian-inspired stylization that was supplemented by minimalism and the contrast between aural and visual signs: scarlet streamers flowing from Lavinia's mouth and wrists to symbolize her rape and mutilation; harp music to accompany her entrance; simple costumes that shared the “universal red of dried blood.” Not only did Brook's “Asian symbolism” made Titus into “a piece of visual and performative virtuosity” but it also tapped into the kinetic energy of the play as ritual and inspired Jan Kott when it toured to Warsaw.Footnote 59 Brook produced A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1970, which was an instant classic, and he adapted the Indian epic Mahabharata in 1985. His Titus is significant in the context of global Shakespeare, as it anticipates the use of red ribbons as symbols of blood and gore in Japanese director Ninagawa Yukio's 2006 production of Titus in Stratford as part of the RSC's Complete Works festival. Ninagawa treated the play as myth, because recurring ritual is a cycle that is best understood through symbolism.

There is a gap between Brook's 1955 and Ninagawa's 2006 versions of Titus. Few British directors followed in Brook's footsteps, though the RSC organized the World Theatre Seasons from 1964 to 1973 under Peter Daubeny's leadership. This brief but spectacular decade at the Aldwych Theatre in London welcomed companies from Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. During this decade, the U.K. premiere of South African playwright Welcome Msomi's 1970 adaptation of Macbeth, entitled uMabatha, took place; at the time, it was a little-known work. Msomi's play was revived in 1997 at the newly opened Globe. The trend of regularly featuring foreign productions did not take off until the 1990s. The belatedness of the emergence of “foreign” and particularly Asian Shakespeares in Britain was conditioned by wars and circumstances of globalization. In addition, the RSC's “powerful routines,” which asserted “the centrality of the [English] text” and textual-analysis-based acting, did not create a receptive environment for the appreciation of non-Anglophone or experimental performances.Footnote 60 Commenting in 1988 on his experience of directing Shakespeare, Peter Hall quipped: “Unless what's on the stage looks like the language, I simply don't believe it.”Footnote 61 Free from such self-imposed linguistic limitations, global Shakespeare thrives in the contact zone between different traditions.

Intercultural borrowings

Both homegrown and touring companies have staged Shakespearean performances in Britain that may sometimes seem foreign to the sensibilities and linguistic repertoire of the local audiences. Whether made in the United Kingdom or elsewhere, these performances have compelled their audiences to negotiate the unfamiliar iterations of the familiar and “local” canon that is Shakespeare. Foreign cultures enter the English stage through three interconnected channels.

The first channel is intercultural borrowings. In connection with the Paris intercultural movement of the 1980s and Brook's works, African, Asian, and Latin American theatrical idioms, including costumes, set, visual culture, performance styles, and music, became more common in directors’ and designers’ visions. While the performances may have been in English, the language of presentation could be perceived to be exotic. As these elements found their way into the mise-en-scène, global Shakespeare divided both critics and audiences. It is not uncommon for a work to be criticized for its penchant for orientalism or Eurocentrism and praised for its global currency, and the phenomenon is not limited to stage productions. There are clearly some risks associated with domesticating foreign materials for consumption by a local audience, but the biggest payoff is a fresh perspective on a “local” canon whose edge has been blunted by the audience's assumed familiarity with it. Echoing the spirit of Peter Brook's 1990 production of La Tempête in Paris with a multiracial cast, Tim Supple's multilingual Midsummer Night's Dream in 2006 was lauded by the Guardian as “the most life-enhancing production” of the play since Brook's 1970 version.Footnote 62 Inspired by his trip to India in 2005 on a British Council grant, Supple used a Sri Lankan and Indian cast in the production. Featuring Hindi, Bengali, Malayalam, Marathi, Tamil, Sanskrit, and English, his production recast the relationship between the play and “India” as a layered concept. The songs and acrobatics enchanted the audience and critics. Even critics such as Nicholas de Jongh who had reservations about the use of multiple languages and the actors’ accents (“the intermittent English speaking is not up to much”) embraced the visual feast. In de Jongh's opinion, Supple's real contribution lies in recovering “that sense of magic and enchantment of which the play has been purged by Anglo-Saxon directors.”Footnote 63 This kind of global Shakespeare laid the foundation for the next mode of engagement: touring.

Working with and against the Surtitles

A second channel has led to surtitled touring productions. Here, the selling point is not necessarily exoticism but rarity—new works or what is not otherwise unavailable. Festival organizers have a curatorial function in bringing together and presenting works by diverse groups. Touring Shakespeare productions share some features with international spectator sports; both require international travel, both are capable of garnering media attention, and both thrive on the unpredictability of the outcome. The theatre audience is simultaneously an outsider (to the foreign style) and an insider (familiar with certain aspects of Shakespeare). Festivals and special events have played an important role in bringing touring productions to London, Stratford-upon-Avon, Edinburgh, and other U.K. cities. In 1994, the Barbican Theatre hosted a festival entitled Everybody's Shakespeare that offered performances by the Comédie-Française (Paris), the Suzuki Company of Toga, Tel Aviv's Itim Theatre Ensemble, Moscow's Detsky Theatre, and the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus. Of interest is how the organizers turned Shakespeare on tour into “consumable chunks of popular culture” in a workshop of metonymic equivalences (the cherry blossom for Japan, drumming for Africa, the carnival for Brazil, and so on).Footnote 64 As is the case with many touring productions, the reception of this festival was characterized by conflicting strands of what Peter Holland has aptly summarized as “xenophobic suspicion at the sheer unEnglishness of the work” and cultural elitism that assumes that the novelty of Shakespeare in Japanese is superior to English Shakespeare conventions.Footnote 65 For some critics, the language barrier proved to be an insurmountable obstacle, as Charles Spencer commented: “There we sit, following [the] surtitles while listening to the performers delivering the matchless poetry in an incomprehensible tongue.”Footnote 66 He wrote with a sense of national pride, and many critics operated under a similar assumption of cultural exclusivity, though few voiced their disapproval in such a radical form.

Interestingly, while these performances may offer rich opportunities for engagement with other cultures through the displacement of the spectator and of familiar signs, such engagement does not always happen. On the contrary, in some cases the reception of touring Shakespeare reveals a great deal about the British attitude toward culture. Theatre reviews are sometimes informed by a sense of self-sufficiency when it comes to touring productions: “Although it is stimulating to be exposed to different views of Shakespeare, there is something coals-to-Newcastle-ish about importing foreign-language productions to England.”Footnote 67 At work behind the attitude is the assumption that global Shakespeare is colonial mimicry. While it may be almost Shakespeare, it always falls short in some respect.

During the World Shakespeare Festival in 2012, the Globe devised a strategy to divert attention away from the surtitles to the action onstage and applied it uniformly to all of the productions in different languages. The purpose was to remove language as a distraction, if not an obstacle, in order to allow for certain degree of improvisation. One obvious limitation is that the architectural space of the Globe is not ideal for line-by-line surtitles because of the pillars and the thrust stage. Only short summaries of the scene—written by the Globe staff in consultation with the visiting companies—were projected on the two screens next to the stage. According to Tom Bird, the synopsis surtitles were meant to avoid the elitism associated with line-by-line translations of Shakespearean texts.Footnote 68 The plot summaries are based on Shakespeare's script most of the time rather than performative choices or improvisational elements. Obviously no synopsis can be neutral whether it is based on narrative or dramaturgical structure, because it involves interpretive acts. As the actors worked with and against the surtitles, the synopsis surtitles redirected the audience's attention to the tension between the plot and dramaturgical structures, highlighting the “Brechtian narrative tension and elements of mediation,” as British scholar and artistic director of the Pantaloons Stephen Purcell observed.Footnote 69 In the Mandarin Richard III, short English phrases were inserted by actors playing the two murderers for more immediate comic effect. In another production, the actors mocked the surtitles. The audiences were told not to trust what was being projected “up there.” In the Hindi production of Twelfth Night by Company Theatre, the yellow tights Saurabh Nayyar's Malvolio wore onstage provided an interesting contrast with the textual presence of cross-gartered yellow stockings. Such moments of textual resistance became more noticeable through the synopsis surtitles.

For certain productions with large expatriate communities in London, such as the Hindi Twelfth Night, the Korean Midsummer Night's Dream, and the Mandarin Richard III, few audience members seemed to miss the surtitles, since a majority of them spoke the language. The strategy of projecting summaries rather than fully translated surtitles was not always successful, as the productions had to be designed to work visually and musically against the crude plot summaries. Some productions worked well for the extremely mixed international audiences, such as audience for the Yohangza Company's A Midsummer Night's Dream (which had toured to the Barbican in London a few years before in 2006 with a full set of surtitles—a line-by-line translation of the adaptation from Korean into modern English). Other companies played to the expatriate community and neglected audience members who were not versed in the language, such as the Company Theatre's Twelfth Night in Hindi, directed by Atul Kumar. Citing “a Hindi-speaking woman sitting next to [him],” Peter Smith applauded the accessible translation in modern prose but lamented the fact that the English-speaking audience had no access to parts of Twelfth Night “that cause the emotions to well up: the delicacy of Viola's ‘patience on a monument’ (2.4.114) or Olivia's pathetic self-abasement as she offers herself to the ungrateful boy (3.4.212).”Footnote 70

Some touring or intercultural productions were seen as showcases for the exotic beauty of unfamiliar performance traditions for cultural elites. Targeting audiences who are bored by an overworked Shakespeare through the education system, the BBC, and the Royal Shakespeare Company, these productions are not for purists. A few strands dominate in the narratives surrounding this type of productions, ranging from celebration of other cultures’ reverence of Shakespeare (e.g., the “Shakespeare Is German” season at the London Globe in 2010) to suspicion about delightful but bewildering (for the press at least) productions that are fully indigenized. The Globe has played host to numerous such productions, and the RSC often sets English-language performances by British actors in non-British locations.

Directors face a dilemma, as they are caught between pursuing authenticity and “selling out.” For example, the RSC's recent English-language productions of two plays, one Chinese and the other Shakespearean, have reignited debates about cultural authenticity. The first is Gregory Doran's adaptation of Orphan of Zhao with an almost exclusively white cast of seventeen. British actors of East Asian heritage have spoken up against the practice of “non-culturally specific casting,” in Doran's words, or colorblind casting.Footnote 71 The politics of recognition can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, intercultural theatre is important testing ground for ethnic equality and raises questions of equal employment opportunity in the UK. On the other hand, can an all-white cast not do justice to the Orphan of Zhao just as an all-Chinese cast performed Richard III at the London Globe and in Beijing? Why would an English adaptation of a Chinese play have to be performed by authentic-looking East Asian actors?Footnote 72 The second is Iqbal Khan's Much Ado About Nothing that is set in contemporary Delhi and staged at the Courtyard Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon in August, 2012. Performed by a cast of second generation Indian British actors to Bollywood-inspired music as part of the WSF, the “postcolonial” production (in Gitanjali Shabani's words)Footnote 73 was quickly compared by the press and reviewers to the two more ethnically authentic productions at the Globe from the Indian Subcontinent (Arpana Company's All's Well That Ends Well directed by Sunil Shanbag in Gujarati and Company Theatre's Twelfth Night directed by Atul Kumar in Hindi). In her essay in the program, Jyotsna Singh reminds the audience that “the romantic, sexual and emotional configurations underpinning the centrality of marriage in Shakespeare's romantic comedies” are elements that “richly resonate within the Indian social and cultural milieu.”Footnote 74 Clare Brennan, writing for the Guardian, believes that the transposition of Messina to contemporary Delhi works well, because it “plays to possible audience preconceptions about the communality and hierarchical structuring of life in India that map effectively on to similar structuring in Elizabethan England.”Footnote 75 However, cultural, linguistic, and ethnic pedigrees are part of the picture, too.Footnote 76 Other critics question the RSC's form of internationalism. Birmingham-born director Khan's treatment of Indian culture is seen as too simplistic. Kate Rumbold wishes the production had not ignored but “ironized the company's inevitable second-generation detachment from India.”Footnote 77 Taking issue with the production's “pastiche of ‘internationalism’, with apparently second generation British actors pretending to return to their cultural roots in a decidedly colonial way,” Kevin Quarmby states that the production offers “the veneer of Indian culture, served on a bed of Bradford or Birmingham Anglicized rice.” He concludes that “as the World Shakespeare Festival and Globe to Globe seasons have shown, ‘international’ is best understood in the context of the nations who embrace Shakespeare as their own.”Footnote 78 The more difficult part of these debates concerns commercialized cultural and ethnic identities. Obviously art and commerce are not antithetical activities, but they have become inescapable predicates in the debates about the sociological and expressive values of touring Shakespeare.

On the other hand, some productions run into the obstacle of an overdetermined locality. Kathakali King Lear challenged the audience while offering unique visual delights. Performed in the traditional theatre form of Kerala, the production offered few clues the audience could use to decode the complex patterns of stylization. Struggling to naturalize and localize the meanings of these performances, some critics become sensitivized to cultural contexts and the lack thereof. In response to Kathakali King Lear at the Globe, Lyn Gardner was concerned about the risk of turning the Globe to Globe season into a fair “showing off a rare animal,” because, she argued, once removed from their cultural context, these productions cease to make sense, at least for the uninitiated.Footnote 79

How efficiently a director presents digestible visual signs has therefore become a factor that determines the fate of touring Shakespeare. At the 2011 Edinburgh Festival, Oh Tae-suk's adaptation of The Tempest was more favorably received than Taiwanese Beijing opera actor and director Wu Hsing-kuo's striking, semiautobiographical solo performance Lear Is Here (which has an impressive history of worldwide tours since its inception in Ariane Mnouchkine's workshop in Paris in 2000). Wu's Lear received mixed reviews because of its more protracted (though equally poignant) backstory about Wu's theatre career and the declining popularity of Beijing opera. Both plays use theatrical stylization and a live orchestra in their respective traditions, and both are “foreign” to both hometown and U.K. audiences. Whereas Prospero's (King Zilzi) island gives Oh a platform for revitalizing traditional Korean cultural milieus that are lost on modern Koreans, King Lear is a springboard for Wu's intense self-reflection. Oh followed Shakespeare's script more closely while offering a two-headed Caliban played by two talented actors in a suit with a pouch. It takes much more extensive background information, especially Wu's life story, to appreciate his treatise of patriarchal authority and its failure in his solo performance. Michael Billington, speaking for most critics, could not grasp Wu's Lear but applauded Oh's creativity.Footnote 80

Similar patterns of thought informed the reception of Ninagawa's samurai-era Coriolanus at the 2007 Barbican International Theatre Event, his kabuki Macbeth at the National Theatre in 1987, and several other productions. Conceptualized by Ninagawa as “dialogues with the dead”Footnote 81 but also a dialogue with Nature, Ninagawa Macbeth acquired divergent meanings during its performances at Nissei Theatre in Tokyo in 1980 and later in London. As Macbeth wades through blood, spring turns to autumn and the petals fall. The encroaching Birnam Wood in the final scene is represented by moving branches onstage. For the Japanese, cherry blossoms symbolize both beauty and death (and the repose of the soul), but Ninagawa's decision to use a direct translation rather than a localized adaptation of the script of Shakespeare's Macbeth introduced unfamiliar narrative patterns into the Japanese audience's horizon of expectation. Inspired by Motojiro Kajii's (1901–32) widely circulated phrase, “dead bodies are buried under the cherry trees,” the production associated death with a cherry tree in full blossom. There can be no consolidated truth about the theatrical traditions of Asia or any part of the world. There was something for everyone in this production when it was staged in Japan and abroad, but it also challenged audience members to grapple with their limitations. Initiated audiences may gain a passing acquaintance with a wider array of performance idioms and cultural themes when enough clues are available, but audiences may also force new meanings on the works that cannot be ignored. The framework of Macbeth offers audience members who are familiar with the play some semblance of control over the exotic performance event. On the other hand, the sheer grace of a backdrop of cherry blossoms can serve up shocking twists and contrasts to the dark tragedy and blood. Audience members who are unfamiliar with the association of cherry blossoms with death in Japan might see the cherry blossoms as an expression of beauty and a marker of Japanese identity, which is one way to read Ninagawa's production.

Joint enterprises

The third channel leading to touring Shakespeare is shaped by coproductions by U.K. and foreign artists or companies, a growth area of theatre practice. Initiated by the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) in 2009, the three-year Bridge Project brought together actors from both sides of the Atlantic—from BAM, the Old Vic, and Neal Street Productions—to stage The Cherry Orchard and The Winter's Tale in New York and London. Another example is a British–Chinese coproduction of King Lear in Mandarin and English, with bilingual surtitles, directed by David Tse (Tse Ka-Shing). This was jointly produced by the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Center and Tse's London-based Yellow Earth Theatre for the RSC Complete Works Festival in Stratford-upon-Avon in November 2006. Here, too, the audience and even the artists seemed to emphasize recognizing the “Shakespeareness” in unfamiliar territory at the expense of other key issues. Peta David, for example, wrote in a review that “it is uncanny that even though I don't have a word of Mandarin to my name I could still tell it was Shakespeare.”Footnote 82 Lear, a Shanghai-based business tycoon who solicits confessions of love from his three daughters, spoke fluent Mandarin Chinese, as did Regan and Goneril. However, the English-educated Cordelia was a member of the Asian diaspora who was no longer proficient in her father's language. Meiyou, which means nothing, is the only Chinese vocabulary Cordelia shares with Lear. The absence of meaning became the meaning of absence.

Each of these touring Shakespeares met with different fates that reflect dominant views about cultural others, and the reception of these works was equally revealing of British attitudes toward national and international theatre. Some works throve on exotic local production values, while others gained additional purchase from the cosmopolitan venue of performance. The perception of agency and efficacy in all three modes of touring Shakespeare is structured around a break, a symbolic abandonment of mainstream English theatre practices. This gap between knowledge of a culture and ignorance of another sometimes contributes to the tendency to read foreign Shakespeare politically, ascribing artistic and moral agency to works that seem to contend with the status quo.

Sites of origin and cultural prestige

At the core of the touring phenomenon is the idea of returning to Britain as a geocultural site of origin (performing “within the architecture Shakespeare wrote for”), as an imaginary site of authenticity (e.g., the Shanghai Kunqu Opera's adaptation of Macbeth, entitled The Story of the Bloody Hand, performed in Scotland in 1987),Footnote 83 and as a privileged site for performative acts (both original practice and international Shakespeares are now the Globe's main products).Footnote 84 It is interesting to note that the logo of the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival (see lower right in Fig. 3) is the Earth seen from over the North Atlantic, showing Britain nearest the center of the world. This “return” is part of the organizing principle of some festivals, and the narrative surrounding it is informed by internationalism and (paradoxically) a form of nationalism. As part of the cultural festival to celebrate the 2012 London Olympics, the multilingual World Shakespeare Festival evoked such a “return.” According to festival director Tom Bird and the Globe's artistic director, Dominic Dromgoole, the festival brought Shakespeare's plays—“plays which have travelled far and wide”—“back home” to London's South Bank, “dressed in the clothes of many peoples.”Footnote 85 Touring Shakespeare is an integral part of Britain's campaign for soft power and self-identity. As the Guardian put it, Britain may be “the birthplace of Chaucer, Milton, Austen, the Brontë sisters and Dickens,” but the country has only one “dominant calling card [Shakespeare] on the global cultural scene.”Footnote 86 Lyn Gardner's candid statement in the Guardian aptly sums up the assumption of a homecoming Shakespeare: “One of the best ways of coming to terms with the Globe to Globe season might be less in measuring the success of each individual production, [and] more [in] how it provides an illustration of how Shakespeare has travelled to every corner of the globe and boomeranged back as something familiar and yet strange.”Footnote 87 Part of the touring boom is created by festivals, internationally renowned films, and visiting companies, and part of it is shaped by British directors who incorporate non-Western performance styles into their productions, such as Peter Brook and Tim Supple, or who work with artists from other parts of the world, such as David Tse, and thereby raise awareness of a broader range of performative possibilities among British audiences.

Many theatre artists rely on international spectators to disseminate their decidedly local works, and some festivals thrive on the ideological purchase of being “global.” For example, the Edinburgh International Festival was established in 1947 to “enliven and enrich the cultural life of Europe, Britain and Scotland” after World War II and to “ create a major new source of tourism revenue” for its host city.Footnote 88 Touring has also been an integral part of the trajectories of some Asian and African companies. The 1990 tour of The Kingdom of Desire (a Beijing opera play inspired by Shakespeare's Macbeth and Kurosawa Akira's Throne of Blood) to the Royal National Theatre in London played a decisive role in shaping the international trajectory of Taiwan's Contemporary Legend Theatre and catapulted it to the center of the international theatre scene.Footnote 89 Msomi's 1970 adaptation of Macbeth would not have achieved international recognition without the 1972 production at Aldwych (as part of the RSC's World Theatre Season) and the 1997 revival at the London Globe.Footnote 90 U.K. tours are equally important for local companies. Thelma Holt Ltd.'s partnership with Ninagawa since 1990 has benefited both sides and made the Japanese director a mainstay on the English stage, and in 2004 Thelma Holt CBE received the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays and Rosette at the Embassy of Japan in the UK in recognition of her contribution to mutual understanding through theatre exchange.Footnote 91