1. Introduction

Dative verbs – that is verbs that take agent, recipient, and theme arguments – have received considerable attention in recent years from a typological perspective. Much research on the morphosyntactic realization options that languages make available for these verbs has focused on the expression of recipients, which has turned out to be major locus of cross-linguistic variation (e.g. Croft et al. Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001; Levin Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008a, Reference Levinb, Reference Levin2010; Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath2005; Kittilä Reference Kittilä2006; Beavers & Nishida Reference Beavers and Nishida2010; Malchukov, Haspelmath & Comrie Reference Malchukov, Haspelmath and Comrie2010). Previous studies of how recipients of dative verbs are grammatically accommodated have made significant contribution to the study of the nature of transitivity, grammatical relations and verb meaning. This paper examines the realization of recipients of dative verbs in Korean and explores its implications for the study of the relation between verb meaning, constructional meaning and their morphosyntactic expression. Korean dative verbs express their recipient using the dative case, as shown with the verb cwu- ‘give’ in (1).Footnote 2 Korean has fairly free word order and (1), as well as other examples of the DAT(ive)-ACC(usative) frame, allow alternative orders of the argument NPs.Footnote 3

While all Korean dative verbs may be found in the DAT-ACC frame illustrated in (1), only a subset of dative verbs that can express causation of possession such as cwu- ‘give’, ceykongha- ‘offer’ and kaluchi- ‘teach’ may also be found in the ACC-ACC frame, as in (2) (Y. Kim Reference Kim1990, Hong Reference Hong1991, Cho Reference Cho1996, Park & Whitman Reference Park and Whitman2003, Jung & Miyagawa Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004, L. Kim Reference Kim2015, among others).Footnote 4

These verbs contrast with the other major subset of dative verbs, verbs of sending and throwing, which are found in the DAT-ACC frame only, as shown in (3).

An often-proposed view of the Korean dative verbs in (2) and (3) is that both give-type verbs and send-/throw-type verbs are associated with a caused motion meaning and that give-type verbs are associated with an additional meaning – caused possession meaning (Park & Whitman Reference Park and Whitman2003, Jung & Miyagawa Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004, L. Kim Reference Kim2015, among others). This view, which I refer to as the polysemy approaches to give-type verbs, is summarized in (4).

This approach appears to correctly capture differences in the distribution of nonanimates in the two constructions. Thus, the class of possessors is plausibly restricted to animates like persons (only people can get or receive things), whereas the class of motion targets or spatial goals has no similar conceptual restriction. We thus predict the well-known observation that nonanimates are able to occur in the locative construction as the locative NP, but not in the ACC-ACC frame.

This polysemy approach to give-type verbs has been called into question. Based on evidence from the distributional property of the directional suffix -lo, an asymmetry in dative verb distribution in idioms and verb–abstract theme combinations, Levin (Reference Levin2010) argues forcefully against the picture in (4) − specifically, against the association of caused motion with give-type verbs. In place of the picture in (4), she proposes alternative associations of verbs with event types in (6) and the corresponding partitioning of verbs in (7), presented further below.

On this proposal, the association of the two frames of Korean dative verbs with the two event types is partly verb-sensitive: the ACC-ACC frame is univocal, but the DAT-ACC frame is polysemous, with its sense depending on the particular verb that appears. Thus, verbs like cwu- ‘give’, which are associated strictly with a caused-possession meaning, are predicted to occur in both frames. Verbs of sending and throwing, which express both caused possession and caused motion, are predicted to occur in the DAT-ACC frame with both meanings.

Levin’s (Reference Levin2010) verb-sensitive approach, however, leaves several issues open. First, Levin (Reference Levin2010) does not address why verbs of sending and throwing in Korean do not occur in the ACC-ACC frame even if they can express both caused possession and caused motion. The partitioning of verbs in (6) predicts verbs of sending and throwing to occur in the ACC-ACC frame only with the caused possession meaning. In her earlier work (Levin Reference Levin2008a, Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008), Levin argued that verbs of giving are associated with a caused possession meaning, while verbs of sending and throwing are associated with a caused motion meaning and, in many languages such as English, Hebrew, and Russian, a caused possession meaning. Levin (Reference Levin2010) shows that verbs of giving and verbs of sending and throwing in Japanese and Korean show the same associations with event types as their English counterparts. She further shows that the actual realizations attested in different languages for each verb type are not exactly the same because the morphosyntactic resources of languages differ. But she has left unexplained how the pairings of semantic classes of dative verbs with morphosyntactic frames disallowed in Korean should be ruled out in a principled way.

A second, related issue is the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of a subset of dative verbs that express transfer of possession such as phal- ‘sell’, kennay- ‘hand’, mathki- ‘entrust’ and namki- ‘leave, bequeath’. These verbs express their recipient argument using dative case only, as shown in (7).

Despite the considerable amount of work on the argument realization of Korean dative verbs, little work has asked why, unlike the verbs in (2), the verbs in (7) are not found in the ACC-ACC frame even though verbs of both types inherently signify acts of giving and have been classified as give-verbs (Pinker Reference Pinker1989; Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995; Krifka Reference Krifka2004; Levin Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008a, Reference Levinb, Reference Levin2010; Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008).

This paper develops an alternative, meaning-sensitive approach to the argument realization of Korean dative verbs that can account for the limited productivity of the dative/accusative alternation in dative verbs (i.e. the contrast between (2) and (3) and between (2) and (7)), while at the same time correctly explaining patterns of verb distribution in ditransitive constructions within and across languages. Building on Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) and Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b), I argue that the semantic classes of dative verbs form an implicational hierarchy which ranks verbs in terms of the degree of the compatibility with a caused possession meaning and that potential variation in and across languages may be modeled by the choice of the cut-off point on this hierarchy with respect to expression in the ditransitive construction.

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, I delineate the verbs I focus on in this study and propose a classification of these verbs based on the result they inherently encode: (i) pure caused possession verbs, (ii) transfer of possession verbs and (iii) caused motion verbs. Section 3 analyzes the meanings of the two dative constructions. Based on previously unobserved meaning differences between the two constructions, I argue that they differ in the type of possessive or ‘have’ relations they encode and that the DAT-ACC frame expresses a superset of the events described by the ACC-ACC frame. Section 4 presents an alternative, meaning sensitive approach to argument realization that succeeds in explaining the limited productivity of the dative/accusative alternation in dative verbs. Building on ideas presented in Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) and Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b), I first argue that these semantic classes of dative verbs form a refined implicational hierarchy which ranks verbs in terms of the degree of the compatibility with a caused possession meaning (see Croft et al. Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001): ‘give’ > pure caused possession > transfer of possession > send-type verbs > throw-type verbs. I then suggest three criteria for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning and show that the analysis of verb–construction pairings proposed here, when combined with an account of variation, provides a unified explanation for verb distribution patterns observed for ditransitive constructions within and across languages and the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of dative verbs in Korean. Section 5 investigates the question whether the DAT-ACC frame and the ACC-ACC frame exhibit syntactic asymmetries similar to the ones observed in the English double object construction and the prepositional dative construction. On the basis of a careful examination of quantifier scope interaction in the DAT-ACC and the ACC-ACC frames, I show that both frames do not show asymmetries in quantifier scope and argues for an analysis which posits the same structure for the two frames. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Major classes of dative verbs in Korean

The focus of this study is a major class of ditransitive verbs that are referred to as dative verbs, i.e. verbs that take agent, recipient and theme arguments.Footnote 5 This section examines the association of semantic classes of dative verbs with event types and proposes a classification of these verbs based on their association with event types.

2.1. Evidence for the monosemy view of give-type verbs

The meaning of dative verbs has been analyzed in terms of two distinct but related event types in (8) (Pinker Reference Pinker1989, Harley Reference Harley2002, Krifka Reference Krifka2004, Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008, Beavers Reference Beavers2011).Footnote 6

These event structures embody distinct types of causative events, one involving possession and the other motion to a goal, perhaps in an abstract domain along the lines embodied in the Localist Hypothesis (Gruber Reference Gruber1965; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972, Reference Jackendoff1983). Since both event types involve agent and theme arguments, the x and z arguments, respectively, the essence of the distinction between them is embodied in the semantic role of the y argument: in the caused possession event type this argument is a recipient, generally an animate entity capable of possession, while in the caused motion event type this argument is a spatial goal. This difference between the two schemas is often represented in standard decompositional terms as in (8), indicating caused possession via a primitive have predicate ranking the recipient higher than the theme and caused motion via a primitive go to predicate that ranks the theme higher than the goal.

An often-proposed view of the Korean dative verbs in (6) above is that both give-type verbs and send-/throw-type verbs are associated with a caused motion meaning and that give-type verbs are associated with an additional meaning – caused possession meaning (Park & Whitman Reference Park and Whitman2003, Jung & Miyagawa Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004, L. Kim Reference Kim2015, among others). Proponents of the multiple meaning approaches to give-type verbs propose that what drives the DAT-ACC case alternation on recipients of these verbs is their multiple meanings whereas the absence of this alternation in send-/throw-type verbs is attributed to their monoseny. It is commonly assumed that these meanings are syntactically encoded by distinct syntactic event decompositions (Park & Whitman Reference Park and Whitman2003, Jung & Miyagawa Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004, L. Kim Reference Kim2015, among others).

However, the polysemy approaches to give-type verbs have been called into question. Levin (Reference Levin2010) has proposed that give-type verbs are associated only with the caused possession meaning, lacking a (possessional or spatial) path constituent: concomitantly, these verbs select a recipient and cannot add a spatial goal. Support for this proposal can be found in -lo suffixation discussed by Levin (Reference Levin2010). She shows that only send- and throw-type verbs, which select for spatial goals as well as recipients, allow the addition of the suffix -lo, which denotes the direction ‘to, toward, (heading) for’ (Sohn Reference Sohn2001: 337). In clear spatial uses, the dative marker -eykey may be suffixed by -lo, while -ey, the dative found with inanimates, alternates with -lo (there is no form *-ey-lo), as shown in the motion verb sentences in (9):

Levin (Reference Levin2010) contends that the suffix -(u)lo, used elsewhere with spatial goals, is found with ponay- ‘send’, but not cwu- ‘give’, as shown in (10) and (11). She interprets the unacceptability of (11) as evidence that argues against the proposal that cwu- ‘give’ has a caused motion meaning in the DAT-ACC frame.

Other give-type verbs contrast with ponay- ‘send’ and pattern with cwu- ‘give’ in this respect: unlike typical goals of motion verbs and recipients of send-/throw-type verbs, recipients of verbs such as ceykongha- ‘offer’, swuyeha- ‘award’ and phal- ‘sell’ do not allow the addition of -lo, as shown in (12).

The distribution of -lo would follow if give-type verbs are associated only with the caused possession event type and take recipients in both frames, while send-/throw-type verbs are associated with the caused motion meaning and take spatial or possessional goals. However, there are give-type verbs that allow the addition of -lo. Native speakers of Korean I have consulted accept sentences in (13), in which the verbs kennay- ‘hand’ and nemki- ‘pass’ occur with -lo.

It should be noted, however, that their judgments on -lo suffixation to the dative recipient of cwu- ‘give’ show greater variability, ranging from marginal acceptability to unacceptability.

Therefore, the facts of -lo suffixation do not appear as simple as Levin (Reference Levin2010) describes, and hence other conclusive evidence needs to be provided to support the proposal that Korean give-type verbs unambiguously encode caused possession, while send-/throw-type verbs do not. In the following, I present alternative evidence for this proposal adduced from the (in)ability of give-type verbs to take a purely spatial goal.

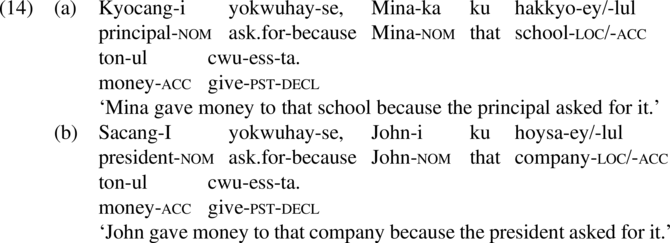

The Korean give-type verbs can take an inanimate location which is reinterpretable as able to possess. Under this interpretation, these verbs can occur in both the LOC-ACC and the ACC-ACC frames, as in (14), contra Jung & Miyagawa (Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004).

Hakkyo ‘school’ in (14a) and hoysa ‘company’ in (14b) are reinterpretable as referring to members of an organization or a company which are understood to be a willing recipient.Footnote 7

With an inanimate location which does not allow such a reinterpretation, both frames of the verb cwu- ‘give’ is unacceptable, as in (15), suggesting that this verb is associated only with a caused possession meaning and concomitantly, it does not select a purely spatial goal.Footnote 8

Unlike give-type verbs, verbs of sending and throwing can take a non-possessional or spatial goal, as in (17), as well as an inanimate location which allows a reinterpretation as a recipient, as in (16).

Other give-type verbs that are found in the DAT-ACC frame only such as kennay- ‘hand’ and phal- ‘sell’ contrast to ponay- ‘send’ and tenci- ‘throw’ and pattern with cwu- ‘give’ in that they are incompatible with a purely spatial goal, as shown in (18b) and (19b).

This difference between the Korean give-type verbs and the send-/throw-type verbs would follow if the former is associated only with the caused possession event type and take recipients in both frames, while the latter are associated with the caused motion event type and take spatial or possessional goals. Thus, the evidence from the (in)ability to take a purely spatial goal provides support for the monosemy view of the Korean give-type verbs summarized in (6a).

2.2. Representing the core meanings of verb types

Current approaches to verb meaning posit a distinction between the core meaning of a verb and a verb’s meaning in specific syntactic context (e.g. Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky1995, Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008, Levin Reference Levin2010, Beavers Reference Beavers2011). A verb’s core meanings refer to meaning components entailed in all uses of the verb, regardless of context, whereas its meaning in specific syntactic context arises from combinations with a particular type of argument.Footnote 9 This section provides representations of the core meanings of the verbs discussed in Section 2.1.

2.2.1. Pure caused possession verbs

Among caused possession verbs, we can distinguish those that lexicalize just caused possession and those that lexicalize transfer of possession. Following Beavers (Reference Beavers2011), I refer to the former type as pure caused possession verbs and the latter as transfer of possession verbs. Pure caused possession verbs (e.g. cwu- ‘give’, ceykongha- ‘offer’, cikupha- ‘pay; grant’, pwuyeha- ‘grant’, sunginha- ‘grant’, yaksokha- ‘promise’, etc.) encode events of caused possession that do not necessarily involve transfer of possession from one possessor to another. This point is illustrated in examples in (20) discussed by Levin (Reference Levin2010).

Example (20a) describes caused possession that is not spatially instantiated and does not involve transfer: when a court gives or grants a parent custody of a child, the court is not the initial possessor of that right; it simply causes the parent to have the right. There is no transfer of possession, but simply caused possession. Similarly, abstract entities such as hope or self-confidence in the example (20b) need not be possessed by the giver or even exist prior to the event. On the basis of this use of cwu- ‘give’, Levin (Reference Levin2010) argues that transfer of possession is conceptually distinct from caused possession and is not part of the meaning of the verb cwu- ‘give’. Comparable examples with other caused possession verbs are given in (21).

Caused possession verbs have been given explicit event decompositional representations in Pinker (Reference Pinker1989), Krifka (Reference Krifka1999, Reference Krifka2004), Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008a), Rappaport Hovav & Levin (Reference Hovav and Levin2008), and Beavers (Reference Beavers2011). Following Tham (Reference Tham2004) and Levin (Reference Levin2010), I assume a primitive predicate have and an additional ontological type, ‘possession-type’, which indicates the type of possession involved. Adopting the neo-Davidsonian representations proposed by Krifka (Reference Krifka1999, Reference Krifka2004), the core meanings of the verb cwu- ‘give’ can be schematized as in (22), where I represent cause as a relation between a causing event and a possessive result state. As made explicit in Pinker (Reference Pinker1989) and Goldberg (Reference Goldberg1995), this verb’s root does not contribute anything beyond what is already encoded in the caused possession event type in (8a).

The result encoded by cwu- ‘give’ is actual possession. This is evidenced by the oddness of denying possession meaning as in (23).

Other pure caused possession verbs (e.g. ceykongha- ‘offer’, cikupha- ‘pay; grant’, sunginha- ‘grant’, yaksokha- ‘promise’, etc.) do not strictly entail possession, and encode possession that is prospective and need not obtain:

Following Koenig & Davis (Reference Koenig and Davis2001), Rappaport Hovav & Levin (Reference Hovav and Levin2008) and Beavers (Reference Beavers2011), the prospective nature of possession can be accommodated by assuming a sublexical modality. In particular, Beavers (Reference Beavers2011: 10) proposes that the possessive relationship is modified by Koenig & Davis’s sublexical modality, requiring only that possession be achieved in some possible worlds, not in all. I adopt this account here, associating to the lexical semantic representation of pure caused possession verbs encoding prospective possession a modal or temporal operator ‘⋄’, which restricts the possible worlds in which possession holds, as in (25). Thus, all caused possession verbs entail at least prospective control, and some have the stronger entailment, i.e. actual possession.

2.2.2. Transfer of possession verbs

Give-type verbs in Levin’s (Reference Levin2010) classification of Korean dative verbs in (6a) also include verbs such as kennay- ‘hand’, namki- ‘bequeath’, phal- ‘sell’, and swuyeha- ‘award’. These verbs differ from pure caused possession verbs in that their meanings necessarily involve a transfer of possession from an original possessor to a new possessor. For these verbs, not only does the recipient come to receive the theme but the causer is the initial possessor and loses the theme. Following Beavers (Reference Beavers2011), I assume that transfer of possession verbs lexicalize two result states: loss of possession by the causer as well as possession by the recipient. As argued by Beavers (Reference Beavers2011) for transfer of possession verbs in English, these verbs encode neither actual loss nor receiving; both are prospective and need not occur. This is illustrated with the felicity of examples in (26), which deny change of possession meaning.

We can thus assume that transfer of possession verbs encode a meaning that entails prospective loss of possession by the causer and prospective possession by the recipient and give these verbs a meaning such as (27), where I represent cause as a relation between a causing event and two result states: a state of there being a prospective loss and another state of there being a prospective possession.Footnote 10

Krifka (Reference Krifka2004) suggests that transfer of possession can be conceptualized as an abstract movement event in a possessional field from the possession of a giver to the possession of a recipient and, concomitantly, the meaning of transfer of possession verbs in English (in the prepositional dative construction) can be represented as movement of objects in possession spaces as in (28), in a way analogous to the meaning of caused motion verbs.

However, the proposal that transfer of possession verbs in Korean have a caused motion meaning is problematic because they do not consistently pattern with verbs that lexicalize a caused motion meaning. Evidence for this can be found in -lo suffixation. As mentioned in Section 2.1 above, speakers’ judgments on -lo suffixation to transfer of possession verbs show considerable variability: verbs such as kennay- ‘hand’ and nemki- ‘pass’, which lexicalize or strongly imply a change in physical location, allow the addition of -lo to the dative recipient, as in (13), whereas verbs such as phal- ‘sell’ and swuyeha- ‘award’ do not allow it, as in (12b) and (12c), repeated here as (29a) and (29b), respectively.

If the transfer of possession verbs are associated with a caused motion meaning and involve a path of motion, then the addition of -lo should be fully acceptable. However, the contrast between these verbs and send-/throw-type verbs illustrated in (10), (11) and (29) strongly suggests that conceptualization of events should be separated from linguistic representation of the core meaning of verbs describing the events and that caused possession and caused motion should be represented differently.

2.2.3. Caused motion verbs

The core meanings of caused motion verbs are associated with the caused motion event type; therefore, by their very nature they entail change of location but not change of possession (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008: 135). This entailment is reflected in the oddness of denying change of location meaning, as in (30).

These examples show that change of location is a necessary part of the meaning of ponay- ‘send’ and tenci- ‘throw’. Thus, following Krifka (Reference Krifka1999, Reference Krifka2004), the lexicalized meanings of these verbs, i.e. caused motion meaning, can be schematized as in (31) (I represent only the shared meaning components of the send- and throw-type verbs, ignoring differences between them); the verb’s root also has an additional semantic field ‘movement-field’, which indicates the semantic field of motion involved.

When caused motion verbs describe events of caused motion to a spatial goal, the event schema associated with such events can be represented as movement of an entity in spatial field as in (32a); when they describe events of caused motion to a possessional goal, the event schema associated with such events can be represented as movement of an entity in possessional field as in (32b).

The classification of Korean dative verbs I have proposed in this section is shown in Table 1. In summary, I have discussed evidence from the (in)ability to take a purely spatial goal and inference patterns that provides support for the monosemy view of the Korean caused possession verbs. Based on this evidence, I have argued that the core meanings of these verbs are associated only with the caused possession event schema and that the core meanings of caused motion verbs are associated with the caused motion event schema. This analysis of the association of verb meaning with event types resembles Levin’s (Reference Levin2010) in that it takes the monosemy view of give-type verbs but differs from Levin’s (Reference Levin2010), which takes send-type verbs to have two meanings, as summarized in (6b). The evidence for the monosemy view of the Korean caused possession verbs I have presented in this section does not provide conclusive evidence for the polysemy of the caused motion verbs. Hence, I leave this as an open issue.

Table 1 Semantic classes of Korean dative verbs.

3. The meanings of the two frames of Korean dative verbs

This section analyzes the meanings of the two frames of Korean dative verbs. On the basis of a careful examination of the events described by the DAT-ACC and ACC-ACC frames of the verbs discussed in Section 2, I argue that the DAT-ACC frame expresses a superset of the events described by the ACC-ACC construction.

Ditransitive constructions in many languages have been shown to express some notion of possession.Footnote 11 It is well-known that there are various types of conceptual relations that come under the general rubric of possession (e.g. Miller & Johnson-Laird Reference Miller and Johnson-Laird1976, Taylor Reference Taylor1996, Tham Reference Tham2004). Below I argue that what the ACC-ACC frame in Korean typically encodes is particular subtypes of possessive relation which involve physical control of an entity (Vikner & Jensen Reference Vikner and Jensen2002, Tham Reference Tham2004), of which ownership is a special kind.

It has been assumed in the literature on the English dative alternation that the notion of possession encoded in caused possession predicates is the same as that encoded by the verb have (e.g. Harley Reference Harley2002, Beavers, Ponvert & Wechsler Reference Beavers, Ponvert and Wechsler2009, Beavers Reference Beavers2011, Harley & Jung Reference Harley and Jung2015). Evidence for this comes from the systematic polysemy of have discussed by Tham (Reference Tham2004). She argues that have can express at least four relations, illustrated in (33a–d).

These include inalienable possession, as in (33a), and alienable possession, as in (33b). She also identifies two other uses of have, which she refers to as a ‘control’ use, where the subject has temporary control of the object but does not necessarily alienably possess or own it, as in (33c), and a ‘focus’ use, where the relationship between the arguments is determined by a rich context, as in (33d), in a context of people being assigned things to deliver. She shows that these four relation types have a privileged status in being the most likely interpretations of constructions typically recognized as being possessive. These relations can thus be treated as representative of a class of possessive relations. Have can also describe relations that do not involve physical control, as in (33e).

Caused possession predicates in English can allow the same meanings, as shown in (34) (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Hovav and Levin2008, Beavers et al. Reference Beavers, Ponvert and Wechsler2009, Beavers Reference Beavers2011) (although this does not mean that all caused possession predicates allow all of these meanings; some may encode only a subset).

The DAT-ACC frame of Korean caused possession verbs can express all of the possessive relations expressed by the English double object frame illustrated in (35), although individual verbs may differ in the types of possessive relations that they can express:

In contrast, the ACC-ACC frame may felicitously express only subsets of the possessive relations described by the DAT-ACC frame. This is illustrated with the infelicity of the sentences in (36a, d, e), describing inalienable possession, focus possession and abstract possession, respectively. These sentences are judged infelicitous even by speakers who accept accusative case-marking of the recipients of transfer of concrete possession uses of caused possession verbs. Notice that the same sentences become felicitous when used to describe alienable or control possession, as shown in (36b) and (36c).

Thus, the ACC-ACC frame in Korean can express only the possessive relations that involve alienable or control possession of the theme, indicating that it is semantically more restricted than the DAT-ACC frame and the double object construction in English.

Hong (Reference Hong1991) and Jung & Miyagawa (Reference Jung and Miyagawa2004) discuss some examples of felicitous ACC-ACC sentences that do not clearly involve alienable or control possession. Such examples include the ditransitive use of verbs of communicated messages and information illustrated in (37).Footnote 12

Goldberg (Reference Goldberg1995) argues that the ditransitive use of English verbs of communicated messages and information may be licensed via metaphors. Following this idea, I suggest that a metaphor relevant to the example of the ACC-ACC frame of kaluchi- ‘teach’ in (37) involves understanding communicated messages or information as being concrete objects. We can title this metaphor ‘possession of communicated messages or information as concrete possession’. The source domain of this metaphor is ‘x cause y to have a/c z’ (for convenience, I notate the possession relation that involves alienable or control possession as the predicate have a/c ), and the target domain is ‘x cause y to understand or perceive information designated by z’. This metaphor is motivated by the fact that giving or causing possession prototypically involves physical entities. It allows the ACC-ACC frame to be used to encode possession of communicated messages or information, thus representing an extended use of the frame. And, as we might expect, the extended multiple accusative expressions are severely restricted in their use and infelicitous with most other verbs of communicated messages. Contrast (37) with (38):

Given the present account these cases can be understood to be a prohibited extension of the basic meaning.

The associations that hold between verbs and the meanings available to them in the ACC-ACC frame can be summarized as in (39). Here, I notate the metaphoric possession relation that involves communicated messages or information as the predicate have m .

As noted above, the DAT-ACC frame describes a superset of the events described by the ACC-ACC frame. These events include (i) causation of the possession which can be understood as general ‘have’ relations including relations that do not belong to standard instances of possession (e.g. abstract possession of properties or emotions), (ii) causation of transfer of possession, and (iii) causation of motion to a goal. The associations that hold between verbs and the meanings available to them in the DAT-ACC frame are summarized in (40). Here, I notate the ‘have’ relations unspecified for the type of possession as have to distinguish such general possessive relations from have a/c , i.e. the possessive relations that involve alienable or control possession.

Thus, the two frames differ in the type of possessive or ‘have’ relations they encode. The difference amounts to increasing specification of ‘have’ relations: the DAT-ACC frame encodes general ‘have’ relations and the ACC-ACC frame encodes a stronger condition (alienable or control possession).

To summarize, on the basis of a careful examination of the events described by the two frames of Korean dative verbs, I have argued that both frames exhibit constructional polysemy: the ACC-ACC frame has causation of the possessive relations that involve alienable or control possession as the basic sense and causation of metaphorical possession (possession of information) as the extended sense, while the DAT-ACC frame has caused motion as the basic sense and causation of general ‘have’ relations and causation of transfer of possession as the extended senses, thus expressing a superset of the events described by the ACC-ACC frame.Footnote 13 I have also shown that this analysis provides a more insightful explanation of the data involving the unacceptability of accusative case on the recipient of abstract themes and other contrasts between the two frames that have been attributed to the meaning difference the verb shows in the syntactic frame in which it occurs.

4. Accounting for verb distribution and argument realization in the two frames

It has been observed that there is crosslinguistic variation in the distribution of semantic verb classes across the ditransitive construction, and thus, in their association with the caused possession event type (Croft et al. 2004; Levin Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b; Kittilä Reference Kittilä2006; Malchukov et al. Reference Malchukov, Haspelmath and Comrie2010). Many languages with a ditransitive construction have been reported to have a closed class of dative verbs. In an extensive crosslinguistic investigation of patterns of argument realization of ditransitives in approximately 300 languages, Kittilä (Reference Kittilä2006) observes that if a language has only one dative verb that can be used ditransitively, it is ‘give’. When a language has more dative verbs that can occur in a ditransitive construction, the ditransitive pattern extends to verbs that can express causation of prospective possession or transfer of possession. Such languages are in sharp contrast to English, which allows a wide range of dative verbs to occur in the ditransitive (double object) construction.

An exploratory study by Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) suggests that the variation in verb distribution in ditransitives takes the form of an implicational hierarchy of dative verbs. Based on an examination of Dutch, English, German and Icelandic, they propose a ditransitivity hierarchy involving three verbs chosen from major dative verb classes in (41): a language only shows the double object construction with a verb at a given point on the hierarchy if it allows it for verbs to its left.

As Croft et al. note, this hierarchy can be accounted for in terms of the nature of the events described by the verbs: that is, giving events necessarily involve transfer of possession, with change of location being incidental; in contrast, throwing is about change of location, which might incidentally be a transfer of possession; sending is both a change-of-possession and change-of-location event. Therefore, all languages allow verbs of giving to be expressed as change-of-possession verbs, but only some languages allow a verb like throw to be used as a transfer-of-possession verb.

A problem for this analysis is that it does not make correct predictions for the distribution of two subtypes of caused possession verbs in ditransitives. On Croft et al.’s account, the ordering of semantic verb classes in (41) reflects how naturally the particular semantic verb type can be associated with transfer of possession. Although Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) do not distinguish between pure caused possession verbs and transfer of possession verbs, a satisfactory analysis of distribution patterns of verb classes in ditransitives requires a distinction between these two classes of verbs because pure caused possession verbs are consistently found in the ditransitive construction, while transfer of possession verbs show varying propensities for being found in this construction. Verb distribution in the ACC-ACC frame in Korean fits this general pattern; other languages that exemplify the same pattern include Fongbe (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1994) and Yaqui (Jelinek & Carnie Reference Jelinek and Carnie2003). For example, in Fongbe, ‘give’ occurs in the double object construction, whereas other verb types (e.g. transfer of possession verbs meaning ‘pass’, ‘sell’ and ‘loan’ and verbs of throwing) are not (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1994: 117–118). In Yaqui, verbs meaning ‘give’ are ditransitive (i.e. take double accusatives), while verbs of sending and throwing are not. Transfer of possession verbs and verbs of communicated messages seem to split across the constructions: verbs meaning ‘lend’, ‘teach’ and ‘show’ are found in the double accusative frame, while verbs meaning ‘sell’, ‘pass/reach’ and ‘tell’ are found only in the DAT-ACC frame (Jelinek & Carnie Reference Jelinek and Carnie2003: 273). Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) predict that transfer of possession verbs will be most consistently found in ditransitives because they denote giving events that necessarily involve change-of-possession and hence best fit the ditransitive prototype. However, this contradicts the previously observed distribution patterns of dative verbs within and across languages.

Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b) proposes an alternative analysis that solves this problem. In her view, the ordering of semantic verb classes in the hierarchy reflects how naturally the particular verb type can be associated with the caused possession event type, not with the transfer-of-possession event type. Building on this idea, I argue that the semantic classes of dative verbs form a refined implicational hierarchy which ranks verbs in terms of the degree of the compatibility with the caused possession event type as in (42) and that potential variation in and across languages may be modeled by the choice of the cut-off point on this hierarchy with respect to expression in the ditransitive construction.Footnote 14

The idea that verbs’ occurrence in a particular construction is determined to a very large degree by their compatibility with the individual senses of the construction plays a central role in the analysis of argument realization in constructional approaches (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg1997; Michaelis & Ruppenhofer Reference Michaelis and Ruppenhofer2000, Reference Michaelis and Ruppenhofer2001; Yoon Reference Yoon2013; Yi Reference Yi2016). In this section, I suggest three criteria for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning and show that the analysis of verb–construction compatibility proposed here, when combined with an account of variation, provides a unified explanation for verb distribution patterns observed for ditransitive constructions within and across languages and the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of dative verbs in Korean.

The first criterion for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning is whether a verb inherently entails the meaning of the construction. This criterion distinguishes caused possession verbs from other verbs: as discussed in Section 2 above, caused possession verbs, not caused motion verbs, lexicalize caused possession and thus inherently entail it. Therefore, caused possession verbs are naturally associated with the caused possession event type due to the very meaning they lexicalize, and concomitantly, they are more compatible with the ditransitive construction than other verbs.

The second criterion is the number of meaning components a verb elaborates or adds: the fewer meaning components a verb elaborates or adds beyond what is already encoded in the construction, the more compatible it is with the construction. Here, ‘elaboration’ means contributing additional information about what is encoded in the semantic representation of the construction, and ‘addition’ means contributing additional meaning components which are not encoded in the semantic representation of the construction. According to this criterion, ‘give’ is most compatible with the ditransitive construction because as Goldberg (Reference Goldberg1995) and Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b) note, it simply instantiates the caused possession event type without contributing anything beyond what is already encoded in it. Other caused possession verbs contribute additional information by elaborating on the caused possession event type or adding further meaning components to it: pure caused possession verbs elaborate on the caused possession event type by contributing the component which specifies the kind of possession involved and the sublexical modality component which restricts the possible worlds in which the change of possession holds. In addition to specifying these components, transfer of possession verbs further add a result state that is not encoded in the caused possession event type, i.e. loss of possession by the causer (Beavers Reference Beavers2011). Thus, transfer of possession verbs both elaborate on the caused possession event type and add further meaning components to it. Caused motion verbs are similar to transfer of possession verbs in this respect, but differ from transfer of possession verbs in that the added meaning component is a caused event (a movement event), not a possessive result.

The criterion of the number of meaning components elaborated or added by a verb also distinguishes the two major subtypes of caused motion verbs, i.e. send-type verbs and throw-type verbs, explaining their placement on the verb class hierarchy. Throw-type verbs are below the send-type verbs in the verb class hierarchy as they lexicalize some manner of motion, i.e. the causer’s instantaneous imparting of a force on an entity, and so add more meaning components that are not encoded in the caused possession event type, compared to the send-type verbs.Footnote 15 Thus, by the very nature of the meaning they lexicalize, throw-type verbs are less likely to focus on the possessive result.

This second criterion for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning only concerns the number of meaning components a verb specifies beyond what is already encoded in the construction; it does not concern the nature of such meaning components, i.e, whether a verb simply elaborates on the constructional meaning or adds further meaning components to it. But this matters as it distinguishes pure caused possession verbs from other verbs and there are languages such as Korean and Yaqui in which the morphosyntactic expression of recipients is sensitive to this distinction. Hence, I suggest the nature of verbs’ contribution, i.e. elaboration or addition, as a third criterion which determines compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning. According to this criterion, a verb class whose members only refine on what is encoded in the caused possession event type is more directly associated with the event type and so more compatible with the ditransitive construction than a verb class whose members contribute an additional event or state. This criterion captures the difference between pure caused possession verbs and transfer of possession verbs, explaining why the former verb class is higher than the latter in the verb class hierarchy.

Do all of these three criteria for verb–construction compatibility have equal status? Clearly not. That the verb must inherently entail the caused possession event type is the most important condition, and serves as a necessary condition in many languages which allow only a closed class of verbs to be used in the ditransitive construction. The reason for this might be that the entailment relationship between verbs and constructions is the most common and the most prototypical way in which verbs and constructions are related (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg1997). The other two criteria are less important, and serve to distinguish verb classes that are indistinguishable by the first criterion.

Given these criteria, we can characterize the different degrees of the compatibility of the semantic classes of verbs with the basic meaning of the ditransitive construction, i.e. the caused possession meaning, as in Table 2. In this table, the most compatible verb is ‘give’: it entails the caused possession event type without contributing anything beyond what is already encoded in it. The second most compatible verbs are other verbs of pure caused possession, verbs which entail the caused possession event type and elaborate on it. The third most compatible verbs are transfer of possession verbs: they are less compatible with the caused possession event type than verbs of pure caused possession as they contribute more meaning components and the nature of their contribution is addition, not elaboration. The fourth most compatible verbs are send-type verbs: these verbs do not meet the first criterion of compatibility and add a caused event which is not encoded in the caused possession event type. The least compatible verbs are throw-type verbs as they do not meet the first criterion of compatibility and add a greater number of meaning components than send-type verbs.

Table 2 Summary of verbs in different degrees of compatibility with caused possession.

Kittilä (Reference Kittilä2006) discusses languages in which only ‘give’ is found in a ditransitive construction. Examples of such languages include Walmatjari, Erromangan and Berbice Dutch Creole (Kittilä Reference Kittilä2006). In Walmatjari and Berbice Dutch Creole, ‘give’ is the only genuinely ditransitive verb, and in Erromangan, there are three other verbs that pattern ditransitively. Kittilä (Reference Kittilä2006) observes that unlike ‘give’, these three ditransitive verbs permit their recipient to bear a marking distinct from the direct object. Further examples of languages with similar variation include Pitjantjatjara, Gurr-Goni, Nungali, and Martuthunira.

Languages differ as to the extent they extend the construction to other verbs. As Levin (Reference Levin2004, Reference Levin2008b) suggests, this variation may be modeled by the choice of the cut-off point on the verb hierarchy with respect to expression in the ditransitive construction. Korean exemplifies a language in which only members of the verb class that is most compatible with the caused possession event type, i.e. pure caused possession verbs, are found in the ditransitive construction. On the present account, the limited productivity of the dative/accusative alternation in the Korean dative verbs is understood as resulting from choosing the cut-off point at the second highest end of the verb hierarchy in (51). Mandarin Chinese is an example of a language which extends the ditransitive (double object) construction to the next most compatible verb class, that is, transfer of possession verbs according to (Chung & Gordon Reference Chung and Gordon1998: 113). Dutch extends the double object construction further down on the hierarchy, admitting send-type verbs but not throw-type verbs (Croft et al. Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001). Languages such as English and Greek choose the cut-off point at the lowest end of the hierarchy, admitting the least compatible verb class, i.e. throw-type verbs, in the ditransitive construction.Footnote 16

Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Barddal, Hollmann, Nielsen, Sotirova and Taoka2001) propose that the caused motion construction is associated with the lower end of a ditransitivity hierarchy. As discussed in Section 3, the DAT-ACC frame of Korean dative verbs has a caused motion meaning as the basic meaning, and thus, can be considered an instantiation of the caused motion construction. Again, the verbs that are found in this frame are determined by their compatibility with the individual meanings (basic or extended) of the frame. Caused motion verbs meet the first criterion of compatibility as they inherently entail the basic meaning of the DAT-ACC frame. Therefore, these verbs are naturally associated with the caused motion event type, and thus, with the caused motion construction.

In contrast, caused possession verbs do not entail the basic meaning of the DAT-ACC frame. These verbs can nevertheless occur in the frame as they inherently entail one of the extended meanings of the frame. Thus, verb distribution in both frames of Korean dative verbs can be captured in a uniform manner in terms of the entailment condition on the semantic compatibility of verbs with constructions. That is, in order for a verb to occur in a particular morphosyntactic frame, it must entail the basic or (one of) the extended meanings of the frame, and the realization of a verb’s arguments in the ACC-ACC frame imposes a stronger requirement on compatibility, i.e. satisfaction of both the entailment condition and the condition that a verb must not add an event or a state which is not specified in the basic meaning of the frame.

In summary, I have argued that the semantic classes of dative verbs form a refined implicational hierarchy ‘give> other verbs of pure caused possession > transfer of possession verbs > send-type verbs > throw-type verbs’ which ranks verbs in terms of the degree of the compatibility with a caused possession event type. I have suggested three criteria for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning and have shown that the analysis of verb–construction pairings proposed here, when combined with an account of variation, provides a unified explanation for verb distribution patterns observed for ditransitive constructions within and across languages and the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of dative verbs in Korean.

5. Ditransitive asymmetries revisited: Quantifier scope interactions

As we have seen in Section 3, the DAT-ACC and ACC-ACC frames differ in their basic meaning. This difference raises the question whether there are syntactic differences between them.

Despite free word order and the absence of an NP–PP alternation in Korean, the two frames of Korean dative verbs have been analyzed as syntactically and semantically analogous to the English dative alternation. In this section, I reassess evidence for the structurally parallel treatment of dative constructions in English and Korean adduced from quantifier scope and argue that the facts of quantifier scope in Korean are not compatible with such a treatment and can be better explained by an alternative theory, which posits the same structure for the ACC-ACC and DAT-ACC frames.

It is well known that double object constructions (DOCs) in English, in contrast with the prepositional dative constructions (PDCs), disallow inverse scope of the second object over the first. In the PDC, a universal quantifier in the recipient can take wide scope with respect to an existential quantifier in the theme, as in (43a). In contrast, in the DOC, scope is fixed to the surface order: an existential quantifier in the recipient must take wide scope with respect to a universal quantifier in the theme, as in (43b).

Bruening (Reference Bruening2001, Reference Bruening2010) argues that this difference between the DOC and the PDC receives a simple account in an asymmetric theory of the English dative constructions. In this theory, the DOC has the recipient NP introduced by an Appl(icative) head (Marantz Reference Marantz1993) that appears between the lexical V, which introduces the internal (theme) argument, and Voice, which introduces the external argument. In contrast, the PDC has a small clause structure, where the theme argument is the specifier of a PP headed by to (see Bruening Reference Bruening2001 for details). The structure that Bruening (Reference Bruening2001, Reference Bruening2010) posits for the quantifier examples in (43a) and (43b) are (44) and (45), respectively.

In (45), the first object asymmetrically m-commands the second. Hence, the second object will be unable to cross over the first in any scope-taking movement, given standard theories of the locality of movement. In contrast, in the prepositional dative structure in (44), the first NP and the PP m-command each other (they are both minimally contained within the same maximal projection) are equidistant for movement to higher positions to take scope. Hence, either the first NP moves first and takes higher scope, or the PP moves and takes scope higher than the first NP.

Building on ideas in Marantz (Reference Marantz1993) and Bruening (Reference Bruening2001, Reference Bruening2010), L. Kim (Reference Kim2015), proposes an asymmetric account of the Korean dative constructions, which posits a different structure for the ACC-ACC frame and the DAT-ACC frame, as illustrated in (46).

On L. Kim’s account, the ACC-ACC frame, like the English DOC in (45) above, has an additional layer of applicative structure with the meaning of possession above VP, seen in (46a), whereas the DAT-ACC frame, like the English PDC in (44) above, has a simpler structure, involving only VP, as seen in (46b).

L. Kim (Reference Kim2015) contends that the two dative constructions in Korean show a scope asymmetry, based on examples (47) and (48).

The examples in (47), taken from L. Kim (Reference Kim2015), show that in the DAT-ACC frame, scope is fixed to the surface order in the canonical order in which the recipient precedes the theme, but flexible in the scrambled order. Thus, in (47a), the canonical order receives only the surface scope reading, in which an existential quantifier in the recipient takes wide scope with respect to a universal quantifier in the theme. This contrasts with the scrambled order in (47b) and (47c), where both the surface scope reading and the inverse scope are possible (in L. Kim’s judgments).

L. Kim (Reference Kim2015) claims that the ACC-ACC frame shows the same scope freezing in the canonical order seen in (48a).

She contends that unlike what we find in the scrambled order of the DAT-ACC frame, scope is frozen in the scrambled order of the ACC-ACC frame, seen in (48b), so that the surface scope reading is unavailable, and only the inverse reading, in which the recipient takes scope over the theme, is possible.

L. Kim (Reference Kim2015) assumes that the scrambling of the theme across the recipient in the DAT-ACC frame is an instance of A-movement, whereas the scrambling of the theme across the recipient in the ACC-ACC frame is an instance of A′-movement (see L. Kim (Reference Kim2015: 38–40) for details), and proposes that the scope difference between the two frames follows from the asymmetric structures shown in (49): (49a) is the structure for the example in (47b) above, and (49b) is the structure for the example in (48b).

In L. Kim’s (Reference Kim2015) asymmetric account, the two objects in the DAT-ACC frame (49a) reside within the same maximal domain, the VP, and so in the resulting structure either the recipient or the theme can undergo movement to check the feature associated with A-scrambling on Voice. This thus predicts that the scrambled order of the DAT-ACC frame will be ambiguous between the surface and the inverse scope readings. The same A-scrambling can take place in the ACC-ACC frame. However, the locality condition on movement results in the theme never being able to cross the higher object (recipient) in A-scrambling. As illustrated in the proposed asymmetric structure (49b), the objects in the ACC-ACC frame are not contained within the same maximal domain: the first object is introduced by Appl, while the second object stays inside the VP. This is why the theme is unable to cross the higher object (recipient) in a scope-taking movement, resulting in the inverse scope being unavailable in the ACC-ACC frame. Instead, the only way for the theme to move across the recipient is by A′-scrambling, meaning that the theme may A′-scramble to to some FP above VoiceP that would check the feature associated with A′-scrambling, as in (49b).

A closer look at the scope properties of the two frames, however, suggests that the Korean data are actually problematic for L. Kimhwith Ae same maximaShe does not thoroughly examine how scope possibilities change according to the quantifiers involved. Consider sentences below, in (50) (the DAT-ACC frame) and (51) (the ACC-ACC frame), in which the recipient is modified by the universal quantifier motun ‘all, every’, and the theme by the existential quantifier etten ‘some’.

Sentences in (50a) and (51a) are canonical order sentences of each frame, and sentences in (50b) and (51b) are scrambled order sentences. Native speakers that I have consulted accept the DAT-ACC and the ACC-ACC sentences in (50) and (51) under both the surface scope interpretation and the inverse scope interpretation in either the canonical or scrambled order. If the ACC-ACC frame were structurally parallel to the English DOC, sentences in (51) should show the same scope freezing that is observed in the English DOC regardless of the quantifiers involved.

Furthermore, the speakers that I have consulted do not agree with L. Kim’s judgments of the example in (48b) above: they accept it under both the inverse scope interpretation and the surface scope interpretation. Whereas the surface scope interpretation is dispreferred in (48b), it is not completely unavailable.

The patterns of quantifier scope interaction discussed in this section are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4 (‘Rec > Th’ indicates the wide scope interpretation of the recipient, and ‘Th > Rec’ the wide scope interpretation of the theme). As shown in these two tables, the Korean data strongly suggest that the relative scope of quantified recipient and theme arguments does not show a sharp contrast in the two frames and is sensitive to the quantifiers involved. Thus, sentences of both frames with a universally quantified theme and an existentially quantified theme show variable scope in either order. These sentences contrast with sentences with an existentially quantified recipient and a universally quantified theme, where only the wide scope interpretation of the recipient is available or strongly preferred. The absence of scope asymmetry in the DAT-ACC and the ACC-ACC frames supports the same structure for these two frames in which both the theme and the recipient are argument of V, as in L. Kim’s (Reference Kim2015) structure for the DAT-ACC frame in (46b) (canonical order) and in (49a) (scrambled order). Thus, in both frames, the theme and the recipient m-command each other (they are both minimally contained within the same maximal projection) are equidistant for movement to higher positions to take scope. Hence, either the theme moves first and takes higher scope, or the recipient moves and takes scope higher than theme.Footnote 17

Table 3 Patterns of quantifier scope interaction in the two frames (Recipient-∃, theme-∀).

Table 4 Patterns of quantifier scope interaction in the two frames (Recipient-∀, theme-∃).

In summary, I have reassessed evidence for the asymmetric account of the dative constructions in Korean adduced from quantifier scope and have demonstrated that the facts of quantifier scope in Korean are not compatible with L. Kim’s (Reference Kim2015) asymmetric account and are better accounted for by an alternative theory which posits the same structure for the two frames. The fact that unlike the DOC and the PDC in English, the DAT-ACC and the ACC-ACC frames do not show an asymmetry in quantifier scope provides strong support to the conclusion that the dative constructions in the two languages are not parallel not only semantically but also syntactically. Whether other phenomena such as idiom formation and nominalization that L. Kim (Reference Kim2015) takes as evidence in support of her asymmetric account require such an explanation I leave for future work.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have presented an analysis of the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of dative verbs which succeeds in accounting for the limited productivity of the dative/accusative alternation in dative verbs in Korean while simultaneously explaining patterns of verb distribution in ditransitive constructions within and across languages. I have suggested that in order to fully understand the alternation, one must recognize more fine-grained distinctions among caused possession verbs than have been recognized, i.e. ‘give’ vs. other verbs of pure caused possession vs. transfer of possession verbs. Semantic classes of dative verbs have been argued to form an implicational hierarchy which ranks verbs in terms of the degree of the compatibility with a caused possession event type. I have also suggested three criteria for compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning and have shown that the analysis of verb–construction pairings proposed here, when combined with an account of variation, provides a unified explanation for verb distribution patterns observed for ditransitive constructions within and across languages and the morphosyntactic expression of recipients of dative verbs in Korean. It accounts for the limited productivity of the dative/accusative alternation in dative verbs in Korean as a consequence of choosing the cut-off point at the second highest end of the verb hierarchy, thus explaining why only pure caused possession verbs may express their recipient argument using accusative case as well as dative case and why the ditransitive (multiple accusative) construction is not extended to other verb classes.

Nevertheless, the present study has an important theoretical limitation in that it allows for a considerable degree of redundancy between the meanings posited for the two frames of dative verbs and the meanings of the associated verbs. For example, the caused motion meaning, which is argued to be the basic meaning of the DAT-ACC frame, is present in the meanings of caused motion verbs; the two extended meanings of this frame, the transfer of possession meaning and the caused possession meaning, correspond to the transfer of possession verbs and the pure caused possession verbs. While some notion of compatibility between verb meaning and constructional meaning is clearly needed to explain the observed patterns of argument realization with dative verbs, more research is needed to investigate how reduction of meanings could be effected.

Final open questions are why some members of the class of transfer of possession verbs (e.g. swuyeha- ‘award’) trigger variable judgments about the acceptability of the ACC-ACC frame and why some members of the class of pure caused possession verbs (e.g. cipwulha- ‘pay’ and yaksokha- ‘promise’) are not found in the ACC-ACC frame and express their recipient argument using dative case only. A full explanation of the variability within the same semantic class of verbs would require a better understanding of the specific contribution of the idiosyncratic meaning of verbs and its interaction with verbs’ structural meanings and constructions’ meanings.