How should we write analytically about musical modernism? More specifically: how might commentators avoid a potentially embarrassing hiatus between, on the one hand, analytical methodologies (most prominently those of Heinrich Schenker and Allen Forte) that achieved their most widespread musicological affirmation in an intellectual atmosphere of positivism and, on the other, theories of modernism (those, for example, of Theodor W. Adorno and Jean-François Lyotard) that are grounded in a post-Kantian tradition of philosophical aesthetics to which positivism is anathema? The present article proposes a solution to this dilemma, by way of a methodological historicism. Music of the early to mid-twentieth century will be analysed according to theories with which composers and critics of the period were widely familiar. But the aim here is not just to recover a sense of why certain works of the 1910s and 1920s were experienced as difficult, even ugly (in a word, modernist), useful though such an exercise may be in terms of historical understanding. A case will also be made for the revival of long-neglected theories of the musical ‘surface’. Although spurned by practitioners of the ‘deep’ approaches fashionable in the 1970s and 1980s, it is the work of phrase analysts of the Formenlehre tradition whose concepts, it will be argued, offer the best hope for a meaningful dialogue between musical analysis and theories of artistic modernism.

The choice of Frank Bridge as a case study is motivated by a conviction that his music, as much as any, offers a British instantiation of the high modernism of the generation of Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky. Bridge has had his analysts, to be sure, yet his work has still to receive the kind of attention it deserves.Footnote 1 The deployment of Formenlehre concepts, within a theoretical framework provided by Adorno's notion of musical ‘reification’, will illuminate important aspects of his later musical development. More questionable, perhaps, is the choice of a British context to frame an analytical-aesthetic investigation of this type – for composition in Britain during the period 1910–30 has traditionally been viewed as largely innocent of modernist impulses. The aim is not to argue that Bridge was a lone voice. His work of the 1920s will be analysed in tandem with that of his contemporary Ralph Vaughan Williams, which, it will be suggested, is also modernist, albeit in a very different way. And yet the recent historical revisionism, which – particularly in studies of British music – has seen the applicability of the term ‘modernist’ widely extended in scope, will not be endorsed. Indeed, it will be argued that the new usage is historiographically unhelpful. The following two methodological sections, which precede an initial approach to the music of Bridge himself, thus have a twin purpose. Analyses of music by Schoenberg and Charles Villiers Stanford serve not only to reintroduce theoretical concerns of bygone generations and to argue for their revival, but also to establish limit cases in a stylistic field within which the complementary modernisms of Bridge and Vaughan Williams, carefully defined, can be heard to orientate themselves.

Music as language I: Schoenberg

A return to Formenlehre can produce some odd bedfellows. Have the names Ebenezer Prout and Theodor W. Adorno ever been found before in the same sentence? The late-Victorian music theorist and the mid-twentieth-century philosopher of aesthetic negativity surely had little in common. It is not hard to imagine Prout's reaction to the Second Viennese School. ‘Without a clearly defined tonality’, he writes, ‘music is impossible.’Footnote 2 Yet at a fundamental level, the two men's understanding of musical syntax is the same. Here is Prout in his treatise Musical Form, the first edition of which dates from 1893:

All music, even the simplest, resembles poetry in requiring regularity of accent and system in cadence. […] A passage ending with a full cadence, and which can be subdivided by some form of middle cadence into at least two parts, is called a SENTENCE or PERIOD.

The end of a sentence corresponds to a full stop, that of a phrase to a semicolon, and of a section to a comma.Footnote 3

And here is Adorno in his 1956 ‘Fragment über Musik und Sprache’:

Music resembles a language. Expressions such as musical idiom, musical intonation, are not simply metaphors. […] The analogy goes beyond the organized connection of sounds and extends materially to the structures. The traditional theory of form employs such terms as sentence, phrase, segment, ways of punctuating – question, exclamation and parenthesis. […] When Beethoven calls for one of the bagatelles in Opus 33 to be played ‘parlando’ he only makes explicit something that is a universal characteristic of music.Footnote 4

Prout and Adorno would disagree as to whether music needs tonality in order to exist, but for both, the music/language resemblance is essential to their arguments.

Let us treat Adorno first. As he explains, music is not literally linguistic. It cannot unambiguously mean anything, as words can. Yet music is ‘permeated through and through with intentionality’: it seems to be about something, even if that something must remain hidden.Footnote 5 The point is crucial to Adorno's understanding of musical modernism, defined as the moment at which the relationship with language breaks down. Music that no longer stands ‘under the sign of pseudomorphosis with verbal language’ is meaningless, he argues. Indeed, it is along precisely these lines that Adorno opposes the ‘closed artwork’ of the bourgeoisie to the ‘fragmentary’ composition of musical modernism, which ‘signifies Utopia in the state of total negativity’. While examples of the new music, such as the Second Symphony, op. 12 (1923), of Ernst Křenek, are strictly incomprehensible in terms of a traditional music/linguistic syntax, they nevertheless manage to speak, Adorno believes, with a truth-bearing power of expression all the greater for its having been released from any socially imposed requirement to make sense.Footnote 6

The recourse to an analogy between music and language is as old as the tradition of musical rhetoric. The emergence of a vocabulary nowadays associated with the tradition of Formenlehre – section/segment, phrase, sentence, period – is usually traced to theorists of the mid-eighteenth century: Joseph Riepel, Johann Kirnberger and Heinrich Christian Koch.Footnote 7 In Adorno's case, it seems fair to suggest a debt to the pedagogy of Schoenberg, whose Fundamentals of Musical Composition often reads as a systematization of the work of the mid-nineteenth-century Berlin theorist A. B. Marx, particularly with respect to the terms period (‘Periode’) and sentence (‘Satz’).Footnote 8 In Anton Webern's 1933 lectures, ‘these two forms’ are described as ‘the basic element, the basis of all thematic structure in the classics and of everything further that has occurred in music down to our time’.Footnote 9 Surprisingly, in the writings of Schoenberg's other pre-eminently celebrated pupil, Alban Berg (who would, in turn, teach Adorno), the distinction barely figures. But when, at the start of his celebrated analysis of the opening of Schoenberg's D minor String Quartet, op. 7 (1904–5), Berg declares that the listener's goal should be that of ‘being able to follow a piece of music as one follows the words of a poem written in a language that one knows perfectly’, there is, pace Jonathan Dunsby, no appeal to ‘noumenal qualities’. The linguistic analogy is to be taken at face value. ‘The only reason’ for ‘the relatively limited accessibility of [Schoenberg's] music’ is to be found in its prosodic character, its avoidance of the conventional ‘periodic symmetry of construction and […] thematic organization that moves in units of even-numbered measures’.Footnote 10

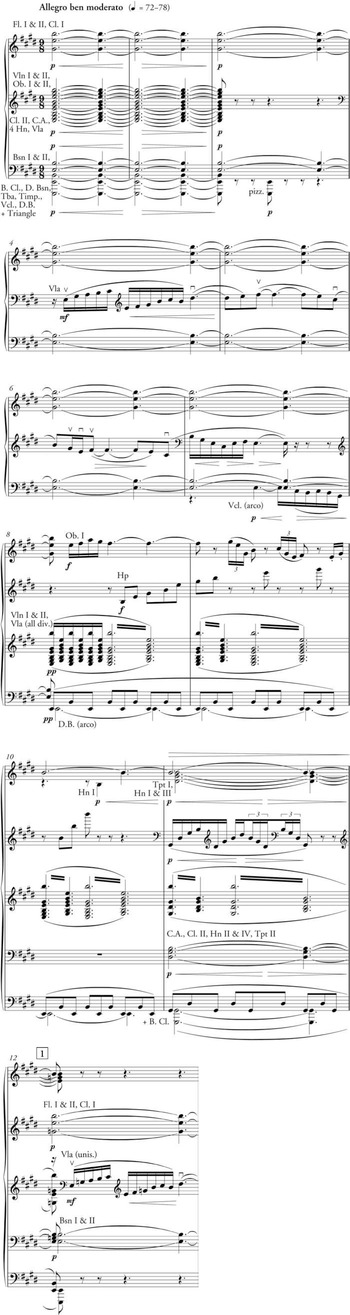

Berg's refusal to tackle a single bar of post-tonal repertory as he ponders the question ‘Why Is Schoenberg's Music So Difficult to Understand?’ must rank as one of the great evasions in the history of writing about music. Schoenberg's own most detailed analysis of one of his ‘free atonal’ compositions is also disappointing in its lack of Formenlehre concerns. In the text of a radio lecture written to precede the 1932 première of his Vier Lieder für Gesang und Orchester, op. 22 (1913–16), he certainly speaks of ‘sections’, ‘interludes’, ‘segments’ and so forth. The opening nine bars of the first song, ‘Seraphita’ (see Example 1), are described as falling into nine ‘phrases’. Any sense of a musical analogue to verbal discourse tends, however, to be played down in favour of a discussion of motive forms: Schoenberg pays particular attention to a ‘fixed motivic unit’ consisting in ‘the sequence of a minor second and third’.Footnote 11

Example 1. Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), ‘Seraphita’, from Vier Lieder, op. 22, for voice and orchestra (1913–16), short score, bars 1–18. From Arnold Schönberg, ‘4 Orchesterlieder für mittlere Stimme und Orchester op. 22’. © Copyright 1917, 1944 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 6060. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

Although he is by no means famed as a close reader of musical texts, it is Adorno, in a piece of relatively extended analytical discussion, who demonstrates how this same instrumental opening section of ‘Seraphita’ may be heard to ‘speak’, an issue largely bypassed in Schoenberg's lecture, let alone in the abstract accounts produced by Forte's pupils.Footnote 12 Schoenberg's nine phrases become a single thematic unit, a period, consisting of an antecedent (bars 04–5) and a consequent (bars 6–9). The parallels between these two phrases are felt especially in the way they open and close. Bars 6–73 are a ‘free variant’ of bars 04–21, while bars 52–4 and 84–9 both have a cadential function. Adorno reads the antecedent as falling into two parts, with a division after the clarinets’ d″ in bar 3. This might suggest the basic idea/contrasting idea dichotomy familiar from Schoenbergian accounts of the period.Footnote 13 But Adorno does not press the point, and with good reason, since the consequent acts here not so much as the classical ‘answer’ to the antecedent as its development: it has an ‘unmistakable continuation character, it leads on’. Indeed, ‘the entire melody is itself just part of a larger form’, to which it stands ‘open’.Footnote 14 Perhaps ‘period’ is not the right term to describe bars 04–9. We might instead attempt to hear bars 04–183 as a single extended sentence, within which bars 6–9 function as a varied repetition of bars 04–5. Bars 10–183 would then constitute a ‘continuation phrase’, marked by typical ‘fragmentation’.Footnote 15 Schoenberg himself notes how the first-violin lines at bars 94–102 and 11 are ‘merely variations of the preceding’ (i.e. the clarinets’ music at bars 04–13 and 61–2).Footnote 16 At bars 12–13 the principal melodic intervals of this music – semitone and minor third – are employed (as f″–f♯″, g″–b♭″) to build slowly to a climax (bars 14–16), crowned by the reappearance (in bar 15) of the even quaver movement of bar 1. The music then swiftly dies down in preparation for the entrance of the singer.

Schoenberg appears to have had no theoretical opposition to the application of this kind of phrase analysis to his post-tonal music. In the Gedanke manuscript he writes of how

In more complex forms, as, for example, the theme of my Wind Quintet, one will have to sense the end of the third phrase (sixth eighth-note, bar 6) in bar 8 (first to sixth eighth-notes), and bar 9 (third and fourth quarters), as well as bar 11 (third to eighth eighth-notes) and bar 13 (second to fourth quarters) as the main matters for which everything else at any time is upbeat, approach, preparation.Footnote 17

It is a pity that he chose such a difficult example. Rather than explore it (since Schoenberg has had his due), we can take the strikingly Riemannian concern for upbeats here as our cue to turn to Prout. For if it was the case in the early 1980s (when Hans Keller made the complaint) that ‘the English-speaking world's ignorance of Riemann's role in the history of analysis is well nigh universal, and proportionally disgraceful’,Footnote 18 80 years previously the success of Prout's textbooks had made Hugo Riemann's ideas – those concerning rhythm and metre, at least – widely known among English-speaking musicians.

Music as language II: Stanford

Taking as his point of departure the volumes Musikalische Dynamik und Agogik (Hamburg, 1884), Katechismus der Kompositionslehre (Leipzig, 1889) and Katechismus der Phrasierung (Leipzig, 1890), Prout produces a thoroughly Riemannian treatment.Footnote 19 Rhythm is defined as ‘the more or less regular recurrence of cadence’, ideally embodied in eight-bar periods or sentences (Prout makes no systematic distinction between these terms) divided into balanced four-bar phrases, of which the second will end with a stronger cadence than the first. Prout fully endorses Riemann's doctrine of Auftaktigkeit. That is to say: not only is the ‘after-phrase’ (‘Nachsatz’) weightier than the ‘fore-phrase’ (‘Vordersatz’), but also this end-orientated quality extends to the level of the ‘motive’, defined as ‘the “protoplasm” – the germ out of which all music springs’. Prout's motive is metrical rather than pitch-based: ‘an accented note preceded by an unaccented note’. The motive corresponds to the poetic foot. As in Riemann, so in Prout, music is essentially iambic. The eight bars of a period/sentence consist in ‘an alternation of accented and unaccented bars’.Footnote 20

Connoisseurs of Riemann's analyses will be familiar with the theoretical knots into which Prout ties himself, especially following from his refusal to allow that the first beat of bar 1 of a composition might, of itself, constitute a strong downbeat. An initial downbeat is an ‘incomplete motive’, and has to be labelled as bar 8 (or 8=1, the = indicating an elision) of ‘a preceding sentence, of which all the rest is wanting’.Footnote 21 Yet Prout's work is not only characterized by pedantry and dogmatism. He demonstrates real ingenuity in the analysis of phrase expansion and contraction,Footnote 22 and when faced with the work of Mendelssohn and Wagner, where the cleanly articulated phrases of the Classical period give way to a more expansive and continuous musical discourse, he recognizes the need for revisions to the system. In his analysis of the subordinate theme (at bars 1072–1231) of Mendelssohn's overture Die schöne Melusine, op. 32 (1833), Prout shows how this 16-bar section expands an eight-bar model, such that it can be viewed as a single bipartite unit, rather than as two conjoined sentences; he also allows the first eight-bar phrase ‘instead of containing a distinct middle cadence, as usual’ to ‘end on a discord’.Footnote 23

As the odd couple of Adorno and Prout is intended to indicate, various kinds of phrase analysis were the stock-in-trade of writers on music from the late nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth. It should come as little surprise to find Stanford, in his textbook Musical Composition of 1911, pointing out that ‘rhythm of phrase […] exactly answers to metre in poetry’ and, further, that this type of medium-scale rhythm is that ‘which enables a composer to write sentences which are intelligible and logical in their relationship to each other, and at the same time to preserve their relative proportion’. ‘Remember’, he warns the student, ‘that sentences to be intelligible must have commas, semicolons, colons, and full stops, and apply this principle to your music.’Footnote 24 By this stage he could count both Bridge and Vaughan Williams (not to speak of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Gustav Holst and John Ireland) among his former pupils; his charges then included (or would soon include) Ivor Gurney, Herbert Howells and Arthur Bliss.

Stanford's work on Musical Composition seems immediately to have followed the completion of his Symphony no. 7 in D minor, op. 124.Footnote 25 In certain respects, the textbook appears designed to fix in prose the precepts embodied in this music. Particularly striking is the insistence that students appreciate the importance of learning to compose variations, characterized as ‘the master-key of the whole building’ of ‘free composition’.Footnote 26 As Jeremy Dibble has observed, ‘With the exception of the first movement, which deploys a conventional sonata structure, the other three movements are entirely preoccupied with variation form.’Footnote 27 In Musical Composition, Stanford analyses sets of variations by Beethoven and Brahms; in his only treatment of a large-scale form not laid out as variations (the opening Allegro of Beethoven's Piano Sonata in E♭, op. 31 no. 3), his primary concern is not periods or sentences but ‘the varied treatment of rhythmic phrases’.Footnote 28 A look at the opening theme of the Seventh Symphony (Example 2a) can nevertheless illustrate how Stanford's ‘varied treatment’ of his own thematic material interacts with musical syntax to generate a diction of considerable complexity.

Example 2a. Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924), Symphony no. 7 in D minor, op. 124 (1911), short score, bars 1–19.

In this case, Schoenbergian terminology seems less useful. Stanford's theme opens as a sentence, with a basic idea (bars 3–5) and its varied repetition (bars 7–10), yet the second half of Example 2a (from the upbeat to bar 11) lacks the fragmentary, developmental character associated with a continuation phrase, comprising instead two closing phrases, again related by variation (bars 104–13 and 14–171). For Prout, such problems of taxonomy do not arise. With regard to the thematic content of phrases or sections, he follows Riemann and simply assigns a capital letter.Footnote 29 Thus Stanford's theme would have a divided fore-phrase A+A, and a divided after-phrase B+B. Bar 1 of Example 2a (as the annotations below the system suggest) would be analysed as (8), the final accented bar of an unheard sentence. Thus bar 2 is (1) and the entry of the first violins at bar 3 coincides with (2), the first true accented bar of the symphony. Taking Stanford's theme as a 16-bar sentence/period, on the model of Prout's example from Die schöne Melusine, we can decide on patterns of accentuation without difficulty, at least at the beginning and end of the extract. Bars 5 and 7 would be marked as (4) and (6), bars 13, 15 and 17 as (12), (14) and (16), with bars 18 and 19 as (16a) and (16b). It is in the middle of the passage that analysis becomes more problematic, such as to cast doubt on the 16-bar model. For it is not a question here (as it is in Die schöne Melusine) of the middle cadence (at (8)) being replaced by a dissonance, while the four-bar phrase rhythm remains intact. At bar 9 of Example 2a there is no sense of a phrase ending at all.

Let us propose instead a single much-expanded eight-bar unit encompassing the entire extract. In bar 8, Stanford moves towards the relative major. But the expected tonic harmony in F is replaced in bar 9 by dominant harmony in D minor.Footnote 30 The eight-bar unit is thus incomplete: Prout would presumably have marked bar 9 as (8=5), to indicate that rather than finding fulfilment in a cadence, the music has returned to the point in the eight-bar cycle immediately prior to the pre-cadential bar (6). Bars 9 and 10 (5a) constitute an accentually weak prolongation of dominant harmony, which is redirected by the diminished seventh at bar 104 to the strong (6) of bar 11. This brings us pre-dominant harmony in F major, leading to the dominant 6–4, 5–3 progression of bar 12 (7). But once again, at bar 13, the resolution to the new tonic is foiled, this time by the addition of the flattened seventh to the harmony, which becomes V7 of IV in F. The suggested notation here is (8=4) rather than (8=5), since bar 13 is accentually stronger than bar 9. From this point the music flows smoothly to the resolution (8) in bar 17 via a shift back to D minor in bar 15 (6).

The conventional analytical approach to the opening of Stanford's Seventh would be Schenkerian. The middleground sketch in Example 2b permits a comprehensive picture of the symphony's opening theme with an efficiency of which Prout's method is incapable. But the recourse to visual metaphor here indicates a shortcoming of the Schenkerian method. As we have seen, Adorno is wedded to musico-linguistic theory. In a critique of Schenker he argues that for the author of Der freie Satz ‘what constitutes the essence […] of the composition is […] more or less its very abstractness’, whereas it is through the kind of ‘individual moment’ reduced by Schenker to ‘the merely accidental and non-essential’ that the work ‘materializes and becomes concrete’.Footnote 31 If the present article calls for a revival of ‘surface’ approaches of a kind that Schenker himself wasted no opportunity to abuse, this is mainly because of their concern with the kind of detail Adorno has in mind. Despite the fact that the reader of a Schenkerian reduction is meant to move back and forth between the background, middleground and foreground levels of a composition, it is clear that the information presented in Example 2b is of a primarily visual, which is to say spatial, rather than audible and temporal nature. As Robert P. Morgan observes, the ‘contrapuntal principles’ on which Schenker's theory rests are ‘extremely abstract’.Footnote 32 To suggest that Schenkerian analysis ‘is based on listening’, as J. P. E. Harper-Scott does, is already to stretch a point; to further claim, in explicitly Heideggerian vein, that ‘the Schenkerian analytical method’ constitutes ‘a phenomenology which basically works for tonal music’ is to commit oneself to a very problematic position.Footnote 33

Example 2b. Stanford, Symphony no. 7, Schenkerian middleground reduction of bars 1–19.

This is not to deny that an approach based on the work of Martin Heidegger can be of use in coming to terms with musical modernism. But it needs to be granted that Heidegger's phenomenological ontology is directed at our pre-theoretical understanding of entities. Heidegger scarcely ever writes about music. But he does touch in detail on listening, or rather ‘hearkening’ (as his translators have it; ‘Horchen’), as opposed to the sense of ‘hearing’ employed in psychology. Heidegger insists that, contrary to the assumptions of the latter discipline, the ability to hear a sound as ‘a “pure sound”’ requires ‘a very artificial and complicated attitude’. ‘Hearkening’ is ‘more primordial’.Footnote 34 As Harper-Scott rightly points out, from a Heideggerian perspective, ‘We don't have to construct musical objects out of an imbroglio of toots, twangs, and scrapes: we simply hear music.’Footnote 35 Such ‘hearkening’, to repeat, is pre-theoretical, immediate. Though Harper-Scott wishes to assimilate Schenkerian analysis to this level of perception, it is hard to see how that could work from a Heideggerian standpoint. For as a highly theoretical construction, Schenkerian analysis necessarily imposes a Cartesian separation of subject and object onto the business of listening to music, an attitude no less ‘artificial and complicated’ than that allegedly assumed by psychology. The phenomenological ontologist's concern, by contrast, is with music's being: the very fact that we do not hear it as discrete sounds. Music has a primordial ‘musicness’, without which Schenkerian or any other kind of analysis would never be possible in the first place.

In the language of Heidegger's essay ‘Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes’ (‘The Origin of the Work of Art’), this opposition of discrete sounds and music would correspond to that of ‘earth’ and ‘world’. As Heidegger might have put it (his treatment of music here is extremely sketchy), ‘world’ stands for the sense in which music ‘musics’: it is the ‘clearing’ on the basis of which we understand music as music. Meanwhile ‘earth’, which stands for the ‘thingly’ aspect of art forms, does not name ‘pure’ sounds, for that would be to repeat the error of psychology. ‘Earth’ must relate to sounds that are already musical, those of a singing voice, say, or a violin; or better, sounds that have an unlimited potential to become music, a potential that is not ‘used up’ in any given composition, and which therefore remains to a certain extent opaque, or ‘self-secluding’.Footnote 36

Here we may trace a path to modernism. As Timothy Clark has suggested, in its mode as poetic creation or Dichtung, the bringing into being of Heidegger's essential ‘strife’ between ‘earth’ and ‘world’ is the model for Lyotard's notion of the ‘differend’ or, as he calls it in respect of works of art, the ‘sublime’. Lyotard's preoccupation is the connection of verbal phrases or ‘locutions’. Each ‘co-presents a whole contextual universe of references, senses, addressee and sender which remains at stake in the manner in which the locution is received’.Footnote 37 There is an element of ‘presentation’ in each locution that cannot arrive at ‘representation’ until it is ‘situated’ by the next. What is crucial is that each act of situation is also a refusal of some of presentation's possibilities. If Lyotard's ‘situation’ corresponds to Heidegger's ‘world’, inasmuch as it sets up the possibility of understanding, ‘presentation’ corresponds to ‘earth’ in its inherent self-seclusion. But what happens when a presentation finds itself ‘momentarily without situation’?Footnote 38 This is the ‘sublime’, assimilated by Lyotard to the Heideggerian ‘event’ (‘Ereignis’), and marked by a ‘privation’ of thought, in which we do not ask ‘what is happening?’, since ‘the event happens as a question mark “before” happening as a question’.Footnote 39 Strictly speaking, as Clark points out, Lyotard goes well beyond his model. Heidegger's Ereignis is not an event within a linear sequence, but ‘the continually self-differing relation of […] presentation to situation’. Ereignis is not ‘earth’ as it waits for ‘world’, but the happening of truth as ‘unconcealment’ in the ‘strife’ between them.Footnote 40 Yet in musical modernism, as we shall see, a phrase (or subphrase) may indeed be heard momentarily as ‘sound’, as perhaps only potentially musical, before another appears to ‘situate’ it. This is not the kind of idea that belongs within the purview of the Schenkerian composing-out of fundamental structures. But it is not hard to see how a theory based on the temporal connection of presentation to situation might be aligned with a notion of music as language. And while Schenkerian analysis can take us to the edge of tonality and no further, the particular advantage of musico-linguistic approaches is that they may deal happily with repertory that straddles tonal and post-tonal idioms. The music of Bridge, to which we now turn, is a case in point.

Early Bridge

A glance at the opening bars of ‘Seascape’, the first movement of Bridge's orchestral suite The Sea (1910–11), is enough to show that the pupil was no imitator of his teacher's style (see Example 3a). In his orchestral music, Bridge tends to avoid the syntactical complexity of our Stanford example. While the leisurely pace, colourful orchestral textures and harmonic audacities of the opening 30 bars of Bridge's movement (which reach their culmination in the passage shown in Example 3b) suggest that the model of Wagner has replaced that of the Mendelssohn who still stands in the background of Example 2a, the phrase structure is plain: as we shall see in a moment, it is a Schoenbergian sentence. In the light of such formal conventionality, it may seem inappropriate to refer to the notion of modernism at this point. And yet here, in the shape of a recent article by Stephen Downes, we encounter the historical revisionism mentioned earlier.Footnote 41 Downes's sophisticated reading is focused on the recapitulation of the climactic moments of Example 3b, which occurs two thirds of the way through the movement. But in order to take proper account of his interpretation, we need to understand his grasp of the opening.

Example 3a. Frank Bridge (1879–1941), ‘Seascape’ from The Sea (1910–11), short score, bars 1–12.

Example 3b Bridge, ‘Seascape’, short score, bars 24–32.

No detail may escape Downes's hermeneutic gaze. After the E major ‘framing’ device (bars 1–2), he identifies a pair of Naturklänge: a ‘wave form’ in the violas (bars 4–7) and ‘perhaps an evocation of a sea-bird song’ on the oboe (bars 8–10).Footnote 42 If these two musical ‘images’ suggest disinterested contemplation or mere representation of a marine environment, the shift from a primarily pentatonic mode in the violas’ opening run (e′, f♯′, g♯′, b′, c♯″, connoting ‘nature’) to ‘lingering dissonant pitches of the seventh and ninth’ (d♯″ and f♯″) hints at a subjective presence. This ‘human’ character is heightened by the melancholy turn to the tonic minor at figure 1, where the Naturklänge are heard once again, and overwhelmingly confirmed at bars 26–7 (Example 3b), where, as the music moves towards the climax of the process of intensification begun at figure 2, ‘the “surface” melodic wave shape disappears’. At figure 3, the height of a ‘larger wave form’ encompassing the whole of the movement's ‘opening paragraph’, Bridge's response to the sea turns from the descriptive to the symbolic. The majestic transformation of the second Naturklang evokes ‘the heroic’, the ‘naval and national’, even ‘the monumental’. The return of the pentatonic mode betokens ‘an attempt to “naturalize” this heroism’. Yet the shift to the ‘melancholic’ submediant at bar 30 ‘betrays the truth that the effect at the peak of the wave – whether of the monumental or the “natural” – is ephemeral’.

Downes's reading is usefully problematic in a variety of ways. It is not just that this type of ‘hermeneutic’ writing runs the risk of making music ‘speak too plainly’.Footnote 43 One would not want to deny the imperial resonance of moments like figure 3 in ‘Seascape’. The sociopolitical background to the ‘ubiquitous interest’ in maritime topics shown by British composers around 1910 has been sketched in elsewhere.Footnote 44 That the ephemerality of the British Empire may be read into a shift to the submediant nevertheless appears somewhat forced. Is the expressive character at bar 30 necessarily melancholic? One might speak instead of a sober grandeur. At the recapitulation (3 bars after figure 9), the submediant chord (corresponding to that of bar 30) is unexpectedly flattened. It is a thrilling moment, the sudden revelation of a new sonic vista. But for Downes it has dark implications. ‘This is the crux of the movement,’ he writes. ‘The deformation of the wave form evokes the problem of memorializing a vanishing, unrepeatable, heroic past, symbolized by the nation's maritime history.’ Indeed, these two climaxes (after figures 3 and 9) are ‘moments of symbolic crisis’, evocations of ‘the modern sublime, where the solace of “good form” – to draw upon Lyotard – is no longer available’.Footnote 45

This is the point at which Examples 1 and 2a become useful as stylistic ‘limit cases’. The above account of the opening of ‘Seraphita’ requires qualification, however. If, as Dunsby once pointed out, the analysis of Schoenberg's music in terms of the composer's own ‘preoccupation with the gesture of musical language’ grants the ‘reward’ of ‘a historical glance through the music’, such that Example 1 may appear within ‘a flow of tradition’,Footnote 46 it is important to be honest about how much of that tradition has been lost in ‘Seraphita’, or transformed out of recognition. The contrast with the opening of the Stanford symphony, completed just two years earlier, could hardly be more striking. That Example 2a submits so readily to Schenkerian reduction is an index of this music's conventionality. Stanford's Seventh ruffled feathers only in respect of its perceived stylistic regression.Footnote 47 But in the case of the Schoenberg, even such a Second Viennese School member as adept as Adorno had to acknowledge this music's difficulty. As he puts it, the clarinet melody has to be helped ‘to become a melody’, since ‘to many this music will at first […] come across as double Dutch [Chinesisch]’. There is an excess of short phrases and a lack of rhythmic regularity, altogether a richness, which makes the music confusing. Only when its articulation is understood – only when it is analysed – will the melody ‘begin to breathe’.Footnote 48

In the language of Lyotard's celebrated 1982 article ‘Réponse à la question: Qu'est-ce que le postmoderne?’, cited by Downes, German Expressionism (typified by the work of Schoenberg) amounts to a modernist ‘nostalgia for presence’, a longing for a lost unity of consciousness, which is to say, a historical situation wherein the ‘bourgeois’ subject entertained no serious doubts as to the efficacy and uniqueness of its inherent powers. By contrast, an art that ‘denies itself the solace of good forms’ corresponds to the ‘postmodern’ sublime: it ‘puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself’.Footnote 49 Little is to be gained by an attempt to paint Bridge as postmodern, especially since, as Fredric Jameson points out, ‘Lyotard was himself in many ways a quintessential modernist, passionately committed to the eruption of the genuinely, the radically, and dare one even say, the authentically New.’Footnote 50 For all the supposed nostalgia of Expressionism, it would seem more appropriate to look to ‘Seraphita’ for music that engenders a feeling of the sublime in purely formal terms. In other words, one may learn to appreciate this music's syntax, as Adorno suggests, and still find it essentially ungraspable in its thematic profusion, its rhythmic irregularity and – last but not least – its freedom from the kind of foundation and direction granted by functional harmony.

Does anyone truly hear bar 10 of Example 1 as ‘merely’ a variation of bar 1, as Schoenberg would have it?Footnote 51 This frenetic outburst of dissonance would seem an obvious candidate for analysis in terms of Lyotard's ‘event’, which testifies in its formal disruptiveness to an absolute that cannot be represented.Footnote 52 By contrast, a composition like The Sea belongs in Lyotard's despised category of ‘realism’: art that confirms to audiences that their view of the world is the right one. Submediant harmonies, flattened or not, are little threat to formal solidity. This music serves precisely ‘to preserve consciousness from doubt’.Footnote 53 How else could it have become such a firm Proms favourite?Footnote 54 It is difficult to imagine how The Sea might be held to ‘investigate what makes it an art object and whether it will be able to find an audience’.Footnote 55 That Schoenberg's atonal music is inherently involved with both kinds of questioning is immediately clear from what Deborah Heckert calls ‘the extremely hostile reception’ of his Five Orchestral Pieces, op. 16 (1909), at the Queen's Hall on 21 September 1912, exactly three weeks after The Sea's triumphant first appearance at the same venue. Although the Schoenberg secured a much better hearing in London (under the composer's baton) just a few months later (as Heckert details), the Five Orchestral Pieces would go on to be heard just twice more at the Proms before the mid-1990s.Footnote 56

Part of the problem is one of periodization. Downes wants to read The Sea as infusing ‘musical forms and effects inherited from high romanticism […] with the structural subversiveness and psychological anxieties characteristic of modernism’.Footnote 57 Yet in 1912, ‘high romanticism’ was long dead, while modernism, in Bridge's case at least, was still a little way off. To be sure, a distinction needs to be made between Bridge's pre-1914 work and the frankly academic, even neoclassical, work of his teacher.Footnote 58 In contrast to the essentially mid-Victorian Stanford, we might suggest, the Bridge of The Sea espouses a post-Wagnerian liberal progressivism, the kind of late-bourgeois position theorized by Carl Dahlhaus under the rubric of ‘musikalische Moderne’.Footnote 59

But the principal point of disagreement here with Downes's reading is formal. Returning to the opening of ‘Seascape’ (Example 3a), we need to pay closer attention to the ‘larger wave’. Downes's two Naturklänge can be read as the two elements in a ‘compound basic idea’.Footnote 60 Their repetition at figure 1 constitutes the counterstatement that completes the presentation phrase. An intensification at figure 2 launches the continuation phrase, characterized by fragmentation and sequence. The function of the climax at figure 3 (Example 3b) is cadential, the return to the tonic signalling an intent to round off – or ‘clamp together’, to use Stanford's phrase – the whole sentence.Footnote 61 The crucial point is that the cadence is held up at its penultimate stage. The pre-dominant supertonic ninth at bar 31 does not move to the dominant, but remains in place as the music flows on. In a post-Wagnerian idiom, as Prout might have observed, not just phrases, but sentences too can end on a discord.

Nor is this the end of the story. In the recapitulation (at figure 9), the cadence is placed first. Knocked off course by the dramatic move to the flattened submediant, the music nevertheless returns to the tonic (at figure 10) by way of the same augmented sixth heard immediately before figure 3. In varied form (rescored and compressed), the compound basic idea and its repetition are heard once more, before the music fades to a fifth in the bass. Above this emerges the only genuinely modernist (perhaps even mildly avant-garde) passage in the movement (see Example 4): a dissonant intervention on high woodwind that in its vivid mimesis of a flock of gulls briefly challenges the idealized seascape with something like reality.Footnote 62 The intrusion (which Downes does not mention) is short-lived. At bar 101, the oboes enter with the second of the Naturklänge. Amid the shrieking gulls, it is briefly estranged. The open fifths D–A lend the figure a Lydian character (with sharpened fourth degree). Yet after the string harmonics of bars 102–3 have died away, Bridge simply reverts to the first oboe's music of bar 9, heard unaccompanied. The horn enters, then the full brass, with the mediant harmony of bar 11, and the movement closes by shifting from iii to I.

Example 4. Bridge, ‘Seascape’, full score, bars 99–103.

That is hardly a satisfactory cadence. And indeed, we have still not heard the last of this material. In the concluding moments of the work, after the final ‘Storm’ has faded to silence, Bridge returns once again to the cadence of the first movement's opening sentence. Again, Downes wants to find disjunction. The return is ‘ex nihilo’, standing as an ‘object trouvé […] musical flotsam left by the passing storm’.Footnote 63 But why not read it as a grandiose wrapping-up (or ‘clamping together’) of unfinished business? This time there is no shift to the flattened submediant, no perfunctory leap to the tonic. Nor does the music find itself becalmed on the supertonic ninth. Instead, ii9 passes to the subdominant and the music surges to a Wagnerian IV–I cadence.

‘Germanic’ or ‘French’?

Back in the ‘postmodern’ 1990s, such a response to musical ‘hermeneutics’ would have met with the Stalinist put-down: ‘formalist’.Footnote 64 This critical tactic would seem particularly obtuse in the case of Bridge. Some composers are indeed formalists, their music best appreciated primarily in formal terms. ‘He represented to me the last of the formalists’: thus the pianist Harold Samuel described Stanford, in a passage chosen by Dibble as the epigraph to his study of the composer.Footnote 65 If the description appears not entirely apt, that is not on account of the character of Stanford's music, but because Bridge, the ‘possessor of the least literary sensibility and education of several generations of English composers’, as Stephen Banfield puts it, was evidently something of a formalist too, in spite of the poetic titles he often gave his compositions (The Sea even has a programme).Footnote 66 But what kind of a formalist was Bridge? ‘Unlike his many British contemporaries who had received a similar German-based grounding in composition’, observes Anthony Payne, Bridge ‘does not seem to have questioned its premises. No antidote was required to the prescribed manner of thematic argument, functional harmony and tonal architecture, as it was in the case of Holst, Vaughan Williams, Ireland and others’; ‘the “syntax” of Bridge's music, throughout his career, was primarily “Germanic”’.Footnote 67

We have already seen how music-linguistic models derived from the study of Austro-German repertory may bear fruit in the analysis of Bridge's early music. Further examples will be provided in due course. First, though, we need to draw the negative consequences of Payne's observation, which amount to a pair of claims: (1) that the ‘French’ and ‘Russian’ music of the early twentieth century is poorly described by the sentential or periodic models used by such theorists as Prout and Adorno; and (2) that if we were to attempt the analysis of music by, say, Vaughan Williams in the terms employed above, we would find our tools not always well suited to the task, ‘tinged’ as is the ‘modernism’ of most British composers of the first half of the century ‘with Debussy, Ravel or Stravinsky’.Footnote 68

There is no space to examine the first claim here. Suffice it to mention Adorno's difficulties. ‘Those listeners schooled in German and Austrian music are familiar with the experience of frustrated expectation in Debussy,’ he writes. ‘Listening must re-educate itself to hear Debussy correctly, not as a process of damming up and release but as a juxtaposition of colors and flashes, as in a painting.’Footnote 69 The second claim will be tested in detail, by reference to a characteristic work of the mature Vaughan Williams: the opening movement of the Pastoral Symphony (completed in 1921).

As commentators have long recognized, this approximates a sonata form.Footnote 70 In the exposition, the various conventional elements appear to be quite clearly articulated: a modulating transition begins with the cor anglais solo just before figure C; the subordinate theme, which has something of the shape of a period (antecedent on cellos, consequent on clarinet), enters with the upbeat to the Poco più mosso one bar after figure D; a codetta follows (one bar before figure E). Yet a closer look at the opening theme (see Example 5) will indicate the inadequacy of these labels. The periodic structure of the theme is not immediately obvious. It is only the older commentators who recognize (following the composer's own note) that the ‘opening subject’ contains both the material given in the bass at bar 4 onwards and that of the solo violin at bar 9.Footnote 71 After three bars of introduction, the basic idea is at bars 4–8 (harp, cellos and basses) and the contrasting idea (led by the solo violin) at bars 82–12. The materials of this antecedent are then repeated (this is the consequent), considerably varied in both cases, at bars 122–16 and 17–251. Overlapping the conclusion of the second statement of the contrasting idea is a ‘cadence’ (named as such by the composer) at bars 233–29.Footnote 72

Example 5. Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958), Pastoral Symphony (completed 1921), first movement, short score, bars 1–29. Copyright © 1924 by J. Curwen & Sons Ltd. US copyright renewed 1952. Copyright © 1990 in the UK, Republic of Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Jamaica and South Africa by Joan Ursula Penton Vaughan Williams, assigned 2008 to The Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust. All rights for these countries administered by Faber Music Ltd, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA. Copyright © 1924 for the World excluding the UK, Republic of Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Jamaica and South Africa by Chester Music Limited trading as J. Curwen & Sons. US copyright renewed 1952. Reprinted by permission of Chester Music Limited trading as J. Curwen & Sons.

It is worth comparing this opening to that of The Sea. There, too, the contrast between basic and contrasting ideas (the Naturklänge) was considerable, particularly in terms of rhythm and texture. Yet bars 4–7 and 8–11 in Example 3a are linked in terms of both harmony (which does not shift from the opening tonic triad until bar 11) and mode (the viola and oboes lines are predominantly pentatonic); they are also metrically balanced (four bars each). In Example 5, the similarities between the basic and contrasting ideas (notably their pentatonicism) would seem outweighed by their differences (in texture, harmony, scoring, rhythm and also tempo). Particularly noteworthy in Example 5, in relation to the opening of The Sea, is the lack of regular phrase rhythm. Vaughan Williams's music is not without conventional points of articulation, not least the way in which the return to the basic idea at bars 12–13 coincides with the return of the accompaniment, from a triad of C♭ major (at bar 122), back up its whole-tone scale of 6–4 triads to the tonic. But the individual elements in Example 5 do not call attention to their relation one to another; indeed they barely seem to belong together, despite the composer's care in fashioning transitions between them. The ‘cadence’ is a case in point. There are in fact motivic and harmonic links here with previous music. The violins’ figure at bars 232–25, taken up in varied form by the horn and cellos in bars 26–7, relates rhythmically and intervallically to the material in the bass at bars 4–5; the ♭iii–I motions at bars 25–291 confirm the tonic of the opening theme as G. Yet the textural and rhythmic contrast between the ‘cadence’ and the surrounding music sets this passage apart. From a syntactical point of view, one might even view the ‘cadence’ as superfluous, since the second part of the preceding statement of the contrasting idea (it divides at figure B) has already signalled a clear cadential intent in the melodic circling around g′at bars 22–3.

In sum, Example 5 gives us a composer concerned with the linking together of varied repetitions of heterogeneous fragments, not with the spinning out of homogeneous paragraphs from smaller units. Vaughan Williams's practice stands in strong contrast to the openings of the large-scale works Bridge was composing a decade or so earlier. In the C minor Phantasie for piano trio (1907), Payne identifies as ‘typical’ a procedure whereby ‘the melody moves forward in easy-going periods with a leisurely counter-statement leading to the dominant and to subsequent polyphonic growth’.Footnote 73 This is a sentential model. With respect to the Phantasie, the opening eight-bar phrase (bars 13–20) of the theme – or ‘paragraph’ – to which Payne refers is followed by a repetition (bars 21–8), the second half of which modulates to the dominant minor in preparation for a continuation phrase. Expanded to take in unexpected shifts to ♭vii and ♯ III, this eventually moves to the tonic for a cadential section beginning at bar 53, the paragraph closing with an orthodox V–i progression that ushers in a transition (at bar 66) based on the somewhat melodramatic material of the introduction (bars 1–10).

The parallels with the opening of The Sea (though the latter is formally simpler) should be clear; Payne finds a similar procedure at the start of the F♯ minor Phantasy for piano quartet (1910).Footnote 74 Here the continuation phrase, beginning at bar 21, may be heard (though Payne does not put it this way) as ushering in an episode in D major (at figure 2), based motivically on the fourth bar (bar 10) of the eight-bar basic idea. The D major episode itself has a sentential form: the four-bar basic idea (bars 26–9) is repeated at bars 30–3 in a varied form that takes the music to F major for the start of a continuation phrase. Bridge uses the latter (bars 34–9) to modulate back to D in preparation for the final section of the theme (bars 40–52), which combines the functions of cadence (it opens with a dominant 6–4 in F♯ minor) and recapitulation (it includes a complete statement of the basic idea).

That Bridge is not solely dependent on sentential expansion to launch his formal structures may be seen from Example 6, which gives the first theme from the Second String Quartet in G minor (1915). Payne shows how the melodic line shared between the violins at bars 152–21 is a disguised repetition of the first violin line at bars 1–4. For Payne, keen to emphasize Bridge's apparently ever-increasing closeness to the ideals of the Second Viennese School, the motivic link reveals ‘a new inclination to develop and vary when repeating’.Footnote 75 But how does this varied repetition interact with the music's syntactical organization? Example 6 appears to constitute a Schoenbergian period: one that is difficult to hear, not because the elements hardly seem to belong with each other (as in Example 5), but because the complexity of the language is pushing the music to the limits of what can be comfortably framed by such conventional organization.

Example 6. Frank Bridge, String Quartet no. 2 in G minor (1915), first movement, bars 1–28.

The varied return identified by Payne could thus be described as an (initially disguised) consequent to the antecedent beginning in bar 1. A 16-bar model (8+8) has been much expanded. And Prout can help us see how this expansion works, though for him, one suspects, the underlying model would once again be a single eight-bar unit. The strong downbeat at bar 1 requires the annotation (8=1); thereafter, the music's progress is regular, at least to start with. If the motivic/rhythmic structure of the first-violin line at the start of the quartet suggests an initial six-bar phrase, divided into two-bar units, the harmonic structure presents a conventional 4+4. The metrically strong position of bar (4) is confirmed by the arrival of dominant harmony on its second beat. Bar (6) is marked, conventionally, by a pre-dominant harmonic function (here V7 of V, with flattened fifth); the dominant follows at bar (7), again as standard. But there is no resolution, no (8): the music leaves the expected course, and only begins to feel its way back to the tonic at bar 11, tentatively labelled (8=6) in view of the pre-dominant diminished seventh at bar 114, preparing the (7) that follows. Again, this does not resolve: Prout might have labelled bar 13 as (7a). As for bar 14, we can label it (8=1) and its successor (2) only because of the way these two 3/2 bars lead to the relatively straightforward bar 16, which we can call (3).

Bar 17 (4) has much the same bass line as the equivalent moment in the antecedent, and is similarly a point of arrival (signalled by the dynamics), though the harmony has changed. Yet progress from here is far from plain sailing. Bar 18 (5) does not lead smoothly into bar 19 (6), and while the latter produces the required pre-dominant function (the German sixth at bar 193), it also coincides with an augmentation, in the second violin, of the melodic line of bars 33–42. In response to this, the music not only slows down in terms of harmonic rhythm, but also moves off in unexpected directions, somewhat as it did at bars 8–10. The harmonies at bars 193–202, 21 and 223–4 can all be read as augmented sixths: in G minor, C minor and E♭ minor, respectively; Bridge finds his way back to G minor via the minor Neapolitan at bar 233–4 (another pre-dominant: for Prout, this would be (6d)). And following this expansion of (6), (7) too is opened up to four bars; the (8) we have been waiting for ever since bar 8 finally arrives at bar 28.

Modernism

Bars 8–10 of Bridge's Second Quartet – and, to a lesser extent, bars 193–23 – seem far more threatening to ‘the solace of good form’ than the passages highlighted by Downes in The Sea. It is not just that the music lurches into the wrong key in the middle of bar 8 (enharmonically perhaps a premonition of the B minor that will dominate the development section). Tonality here is put seriously into doubt. A pitch-class set (or serial) analyst would be interested in the treatment of the (016) trichord in the melody line here. The sequence a″–b♭″–e♭‴at bar 83–4 becomes d ♭‴–a♭″–g″ (a transposed retrograde) in the following bar, and is then repeated (with initial octave displacement) as d ♭″–a♭″–g″ in bar 10, and transposed (using the contour of bar 9) to f″–c″–b′ in bar 11. Perhaps most strikingly, the first two beats of bar 10, taken on their own (and without the e♭′ in the cello), are a direct anticipation of a prominent idea in the first movement of one of Bridge's most modernistic works (from which the next example will be taken), the Piano Sonata of 1921–4. The ‘shared mediant’ harmony at bar 103 is a close relative of the celebrated ‘Bridge chord’.Footnote 76

Downes is, of course, not the only recent commentator on British music to attempt to redefine as ‘modernist’ (or ‘early modernist’) repertory that would previously have been referred to as ‘late Romantic’. In his provocatively titled Edward Elgar, Modernist (discussed above in relation to its use of Heidegger), Harper-Scott provides an initial justification for this revisionism by reference to the work of James Hepokoski, which in turn relies on that of Dahlhaus.Footnote 77 And yet, as Matthew Riley has pointed out, Hepokoski's influential deployment of the term ‘modernist’ to name the generation of composers (including Elgar) born around 1860 rests on an awkward translation, if not an error.Footnote 78 It is by no means Dahlhaus's intention (neither is it Hepokoski's) to suggest, as Harper-Scott has it, that ‘the same musical questions that troubled Schoenberg also troubled Elgar’.Footnote 79 Confusion has arisen here as a result of the decision by Dahlhaus's translators to render as ‘modernism’ his notion of musikalische Moderne – literally, ‘musical modernity’ – which he wished to substitute for Spätromantik.Footnote 80 Dahlhaus clearly preserves a chronological as well as stylistic distinction between musikalische Moderne (1889–1907) and the Adornian Neue Musik (1908 onwards), such that when the term ‘modernism’ is not reserved for the latter concept (as it is in the present article), the situation can become complex indeed. Thus Schoenberg can be viewed as ‘opening the path that led from “modernism” to the “new music”’, which in English would normally be tautologous.Footnote 81 As the above comparison of Schoenberg and Bridge indicated, the distinction between Neue Musik and musikalische Moderne is useful; it can be retained by more careful translation of the latter, as ‘liberal progressivism’, for example.

Nor is it only the period 1890–1914 that has been subject to revisionism. Jenny Doctor has issued a plea for British music of the interwar years ‘to be reconsidered, remarketed, and rebranded today in terms that are markedly and unequivocally different from styles that have come to exemplify Continental avant-garde practices of the period’.Footnote 82 The insularity of this proposal should surely be resisted. For one thing, it plays into long-standing assumptions that British composers of the 1920s and 1930s were, in general, stylistically more conservative than their Continental peers. A comparative account of French, German or Italian music – especially that of the 1930s – would, one suspects, demonstrate that they were not. More importantly in the present context, Doctor neglects the instance in interwar Britain of a ‘senior figure who had faced up to the most advanced continental developments and proved that an English composer of integrity could emerge from the experience not only unscathed but immeasurably enriched’: Bridge himself.Footnote 83 Concomitant with her plea for ‘rebranding’ is a notion that ‘British musical modernism’ may be ‘rediscovered, reassessed, and eventually re-audited’ in ‘uncelebrated layers of activity […] often derided […] as tonal, conservative, and unimportant’.Footnote 84 The aim is generous. Yet as Christopher Chowrimootoo has pointed out, recent critical attempts to undermine the boundaries and hierarchies erected by both modernism's supporters and its detractors run the risk of producing a category ‘so broad as to become meaningless’.Footnote 85

Doctor's position has been supported by Byron Adams, in a manner which suggests that the issue at stake here is less British musical history than recent disciplinary upheavals in English-language musicology. Doubtless the academic modernism of the cold-war period licensed unpleasant exclusionary attitudes, inherently linked to an evolutionary philosophy of history couched in narrowly technical terms. But to conclude from the ‘postmodern’ rejection of all these things that scholarly attention to the formal innovations so prized by generations of modernists and their supporters should be diverted towards the vision of ‘a playing field located at the intersection of cultural assumptions, historical context, and musical praxis’ is arguably to obscure the particular kinds of relationship between world and work that made modernism what it was.Footnote 86

Jameson (of whose work Adams approves) has little sympathy for ‘the ideology of modernism’, his term for the attitude typical of Adams's ‘conservative modernism’: in brief, an insistence on the transhistorical validity of the autonomy of the aesthetic that derives not from the ‘high modernists’ of the first half of the century, but from the epigonistic ‘late modernists’ of the post-1945 period. Jameson argues that ‘as an ideal and a prescription, a supreme value as well as a regulatory principle, aesthetic autonomy did not yet exist in the modernist period, or only as a by-product and an after-thought’. From a musical perspective, the ‘ideology of modernism’ can be understood as the theory of the practice of postwar academic serialism, which was itself made possible by the retrospective identification of high modernism in terms of the autonomy of the aesthetic. Operating a radical disjunction between music and culture, this ideology constructed a notion of ‘the music itself’, which corresponds (as Jameson puts it in respect of ‘Literature’) to ‘that quite delimited historical phenomenon called modernism (along with such fragments of the past as [late] modernism has chosen to rewrite in its own image)’.Footnote 87

The ‘semi-autonomy’ of high modernism, by contrast, always insisted on some kind of extra-aesthetic justification for its practice.Footnote 88 This distinction might appear to legitimate Adams's ‘playing field’, but no: his is surely too generalized an approach. For Jameson, high modernism seeks the Absolute, in a quasi-religious, prophetic (and quite often political) manner that sets it apart not just from the ‘late modernism’ of the 1950s and 1960s, but also from the ‘liberal progressivism’ of the 1890s and 1900s and the ‘realism’ of the 1930s and 1940s. Figures like the poets Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot are ‘genuine modernists’ inasmuch as their work is driven by a ‘transcendental motivation’, which in Eliot's case amounts to ‘a vision of a total social transformation’. We have already witnessed something of this line of thought in Lyotard, but Jameson prefers to cite Adorno, whom he regards as reinventing the classical vocation of modernism amid the cold war. ‘In order for the work of art to be purely and fully a work of art, it must be more than a work of art.’Footnote 89

It would seem constitutive of modernism that its leading figures should have rejected the musical language of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as exhausted. More precisely, as Adorno explains, the language was rejected in the academic form in which it was handed down by teachers such as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: ‘a consensus mediated by education’.Footnote 90 To use the terminology Adorno borrowed from Georg Lukács's 1923 book Geschichte und Klassenbewusstsein, the traditional musical language had been ‘reified’. When musical material arrives at the state which the earlier, pre-Marxist Lukács called ‘second nature’, or in other words ‘the world of convention’ (as Gillian Rose has it), its meaning, or ‘significance’, becomes ‘rigid and strange, […] it no longer awakens interiority’.Footnote 91 In Adorno's philosophical analyses, Rose points out, the charge of ‘reified’ thinking ‘always designates some kind of dislocation […] in the relation between the subject and the object’.Footnote 92 Musical modernism has its source in the alienation of young composers from their material. What had once been alive was now dying or dead: tonality no longer possessed ‘the pounding force [it] had exercised in the heroic age of the bourgeoisie’.Footnote 93 Like that of all modernists, Stravinsky's aim was to recapture something of that force. He wanted a musical ‘authenticity’, to equip his work ‘with the power to claim for itself that it is as it must be and could not be otherwise’.Footnote 94 Yet composers of the early twentieth century were fighting a losing battle. ‘Even the most perfect song by Webern is inferior in its authenticity to the simplest piece in Franz Schubert's Winterreise.’Footnote 95

As David Roberts explains, for Adorno ‘the dialectic of enlightenment unfolded by the history of bourgeois music is the history of progress in the age of progress’. This dialectic operated in terms of an opposition of ‘the latent and the manifest’. During the period of common practice, musical material appeared substantially opaque, as if it were ‘nature’, or ‘the Kantian thing in itself’. Progress in music was possible because composers, as they brought the material under increasingly rational control (the ‘manifest’ pole of the dialectic), remained guided by the external law of tonality (the ‘latent’).Footnote 96 As Adorno insists, it is by means of the ‘penetration’ of ‘free artistic production’ by what is heteronomous to it that this same production ‘exclusively receives its meaning’.Footnote 97

Late bourgeois tonality was weakened not only by reification. It is clear from music like the opening of Bridge's Second Quartet that further ‘progress’ would not be possible without breaking some of tonality's fundamental precepts. Bridge, as we have seen, belongs in the ‘Austro-German’ camp. But what of ‘French’ or ‘Russian’ modernism? In contrast to the Second Viennese School, who attempted – vainly – to follow the dialectic beyond its conclusion, Stravinsky, so Adorno reckons, had recourse to violence. He expected to recover an elemental musical authenticity via ‘the demolishing of intentions’. These ‘intentions’ are inherent in traditional musical language insofar as the ‘immanent dynamic of musical material’ presents composers (and listeners) with expectations or demands. But Stravinsky is averse to ‘the entire syntax of music’. In his ‘fierce suspension’ of the ‘humanely eloquent’, he mounts an assault on traditional music's expressive communicativeness: its ability to ‘speak’. Drawing on Debussy's ‘atomization of the motif’, Stravinsky goes a stage further, transforming ‘a means of achieving a seamless flowing texture into a means of disintegrating organic continuity’.Footnote 98

From a traditional Austro-German perspective, the result is strictly meaningless. And it is thus that Stravinsky's music comes to be ‘more than’ just music. The illusion created by the closed, ‘bourgeois’ work of art is that of the union of subject and object (‘manifest’ and ‘latent’) in a seamless form that, precisely on account of its seamlessness, remains ‘blind’ to the world in which it is created. In the ‘fragmentary’, modernist work, a ‘chasm’ opens up between subject and object, such that music may be counted a mode of knowledge.Footnote 99 This is the point at which we may invoke the Absolute. The ‘objective catastrophe’ of ‘a world worthy of death’, witnessed by the Second Symphony of Křenek, nevertheless ‘signifies Utopia in the state of total negativity’, inasmuch as this music's ability to speak meaninglessly brings as its ‘corollary […] the liberation of the subject from all the confining forms of repressive self-identity’.Footnote 100 But this is the point at which Stravinsky appears most problematic, for the knowledge his music delivers is not ‘critical’. To be sure, The Rite of Spring, with its dehumanizing recourse to ‘barbaric’ qualities of melody, rhythm and form, begins as liberal cultural criticism, the ballet's portrayal of human sacrifice a registration of ‘the growing superiority of the collective’ in industrial modernity.Footnote 101 The difficulty is that of the ‘unmistakable affinity of The Rite of Spring to its subject’, the way ‘the aesthetic nerves quiver to return to the Stone Age’.Footnote 102 The Stravinskian Absolute resides in power (which the composer thinks to wield himself), before which ‘a blindly integrated society […] of eunuchs and the mindless’ stands trembling.Footnote 103

Writing effectively

Stravinsky's basic problem, it has been suggested, was not so much the reified character of late bourgeois academic musical language as his inability to deploy it effectively. ‘Capable only of featureless mediocrity when composing “by the book”’, as Robin Holloway puts it, Stravinsky found his compositional feet (in Petrushka) in an attitude of ‘subversion’ towards official musical culture.Footnote 104 It is in these terms that we may venture a return to British repertory, and in particular to the French- or Russian-‘tinged’ Vaughan Williams. Certainly no composer was ever more frank in his admissions of technical failings. ‘I have struggled all my life to conquer amateurish technique,’ he wrote at the end of the 1940s, ‘and, now that perhaps I have mastered it, it seems too late to make any use of it.’Footnote 105 Transition sections posed a special challenge. ‘You either think of a tune or you don't: it's the getting from one to another that's the difficulty in composition.’ This was advice to pupils, yet as Anthony Barone observes, Vaughan Williams ‘was speaking from experience’.Footnote 106 In marked contrast to Stanford, but in company with Hubert Parry (whose work Vaughan Williams could describe, tellingly, as both ‘peculiarly English’ and ‘sometimes musically inarticulate and clumsy’),Footnote 107 Vaughan Williams evidently lacked the kind of fluency that would have smoothed over formal problems of this kind. Adams's insistence that the revisions to the score of the Sixth Symphony reveal ‘an anxious, even restless, perfectionist, ever striving for greater clarity and concision’ only reinforces the image of a composer who indeed struggled to meet the kind of professional demands that Bridge imposed on his pupil Benjamin Britten: ‘the absolutely clear relationship of what was in my mind to what was on the paper’.Footnote 108

The youthful Britten's opinion of Vaughan Williams's ‘technical incompetence’ is well known: the ‘amateurishness & clumsiness’ of the F minor Symphony, its ‘pretentiousness […] & abominable scoring’. Britten's ‘struggle […] to develop a consciously controlled professional technique’, he later recalled, ‘was a struggle away from everything Vaughan Williams seemed to stand for’.Footnote 109 But what was it that the older composer represented? In the case of Stravinsky, Holloway argues, innate deficiencies are ‘converted to benefits’. If the student compositions demonstrate ‘short-windedness’, this ‘becomes the basis for a brusque terseness of articulation and punctuation, a gestural authority […] unrivalled before or since’.Footnote 110 Perhaps Vaughan Williams's difficulties with transitions may be viewed in a similar light. In his study of the sketches for the finale of the F minor Symphony, Barone notes how the composer, as he worked on the score, tended to abridge transitions ‘in favor of abrupt dislocation and contrast’, even as the broader context of the work was that of ‘the organicizing procedures of the symphonic tradition’.Footnote 111 The effect derided by Britten as ‘clumsiness’ was something Vaughan Williams laboured to achieve.

Let us return to Example 5. Daniel Grimley has already brought up Stravinsky's name in relation to ‘the additive phrase structure and irregular metrical organization’ at the start of the Pastoral Symphony.Footnote 112 The opening eight bars, with their two lines moving independently, could be taken as an instance of Stravinskian ‘layering’.Footnote 113 Of the two lines, the bass entry, with its subphrases five, seven and three crotchet beats in length, constitutes a slow-motion example of the varied yet static repetition that so aggravated Adorno. Meanwhile, the treble layer, when it repeats the music of bars 3–4 at bars 52–72, has been metrically displaced in a very Stravinskian manner by the ‘extra’ crotchet beat at the start of bar 5, such that what was metrically strong is now weak, and vice versa.Footnote 114 Vaughan Williams here practises his own undemonstrative ‘subversion’. There are elements that, from the perspective of the academic technique of, say, Stanford, would appear ungainly, even rough: the ‘primitive’ doubling of contrapuntal lines in parallel triads (which has so often moved commentators to speak of organum); the bitonal dissonances created by the further ‘layering’ at bars 9–12 and 17–23. More generally, there is something formally not quite transparent about the music in Example 5. Neither is it really a period, nor are the sections cleanly juxtaposed. As Britten might have said, the music does not ‘seem to hang together’.Footnote 115

If that seems an unfair judgment on one of Vaughan Williams's most polished scores, one need only compare the passage from Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé (1909–12), from which Vaughan Williams appears to have ‘cribbed’ his opening: the ‘Danse légère et gracieuse de Daphnis’ at figures 43–51.Footnote 116 In the Ravel, too, there are juxtapositions of material – Nijinsky's leaps! – yet these are contained within balanced phrases of classical propriety and clarity: an overall ternary structure with coda, featuring artfully varied sentential repetitions. When the opening of the Pastoral Symphony is placed next to the Ravel, we may indeed hear how Vaughan Williams's aim for a ‘lack of artifice’ reveals the Englishman pausing ‘over the crucial modernist conundrum of “authenticity”’.Footnote 117 It is in the sophisticated unsophistication of the musical diction in the Pastoral Symphony that a ‘modernist’ element in this music may be located. Some found the work ‘incomprehensible’ at its première; its ‘whisperings […] were audible to the intelligences of but few’. But as Hubert Foss put it, it was not ‘the idiom itself’ that was ‘unfamiliar’. ‘The words are not strange, so much as the way they are grouped into sentences, paragraphs, and chapters.’Footnote 118

Appreciative quotation from Foss's book is unusual these days. For Alain Frogley, the positive connection Foss draws between Vaughan Williams's technical ‘clumsiness’ and his ‘Englishry’ has done much to harm the composer's reputation. In the work of recent commentators, one is more likely to read defences of Vaughan Williams's technical ‘mastery’.Footnote 119 Yet from the present perspective, such defensiveness misses a crucial feature of the composer's mature aesthetic. Indeed, it is from Foss that we learn most clearly how the traits rejected by Britten may be regarded precisely as those of modernism. Foss is that rare thing: in Jameson's terms, not an ideologist of modernism but a genuinely modernist critic. He is strikingly disappointed by Vaughan Williams's late achievement of fluency. The ‘technical accomplishment’ of the E minor Symphony (no. 6) may be ‘firm and secure’, but the music seems to be ‘dictating to the man, who seems happy to be “bullied” by his ideas’. In the previous symphonies, Foss suggests, ‘the materia musica was contrived to express the thought conceived, invented as the only means of conveying the true meaning of one mind to others’.Footnote 120

The search for truth is the key to Vaughan Williams's achievement. As a young man, he set himself to learn to compose according to academic rules, and succeeded. Yet the rules ‘would not contain the music he wanted to produce from within himself’. In response, Vaughan Williams took ‘a conventional musical technique’ and made ‘an entirely novel music out of it’.Footnote 121 The results are ‘impolite’: the composer's work ‘conforms to no Leipzig standards’. Especially noteworthy is Foss's insistence that ‘inquiry devoted only to the music, to the notes printed on the staves in the scores […] will lead to no more than partial enlightenment’.Footnote 122 In Foss's reading, Vaughan Williams's work has the modernist quality, identified earlier, of being ‘more than’ just music, which is precisely not to say that it is illustrative. In the Pastoral Symphony, ‘there is no “meaning” save in the music, which is logical and not impressionistic’.Footnote 123 Foss seeks the music's ‘Englishry’ in its form:

The out-of-door life is […] like carpentry, firm and moderately exact: but it is not like illumination or silver-work – not perfect in detail and carefully cherished during the process of creation. We scan a five-barred gate from a distance, admiring its strength and the solidity of its morticing, and do not notice its rough edges.Footnote 124

He has a particular affection for the last of the Four Hymns for tenor, viola and strings (1914):

Out-of-door carpentry, perhaps, it is. […] I feel I am standing outside a massive building, enjoying the smooth, living grass in the precincts and hearing this elemental song come to me through the stained glass of the windows as I stand in the sun and air. I am filled with naturalistic adoration. An ancient voice is ‘crying and calling to me’, the voice of a man alive in my day who can speak, in intelligible language, of England's history, of her men and women and her slowly changing landscape.Footnote 125

In Vaughan Williams's work we can scarcely talk of ‘knowledge’ in Adorno's sense: there is little fragmentariness here. The composer aims for a rough-hewn quality, and in this Foss hears an attempt to bear witness to the truth – to the Absolute, let us say – with regard to which he wants his readers to recognize that its content, undefinable as it is and must be (and hopelessly ideological as such a notion now appears), is essentially English.

What of Bridge? Here is a composer who suffered none of the difficulties or dissatisfactions of a Stravinsky or a Vaughan Williams with the established musical language of the late nineteenth century. The Second Quartet gives us a composer – still a ‘progressive’ rather than a ‘modernist’ – in virtuoso command of basically traditional material. Yet already in 1912 or 1913, Payne suggests, ‘Bridge seemed to have sensed that something was missing from his music.’ Payne finds ‘a certain predictability’ in the harmonic and thematic characters of Bridge's earlier work, a failure to create the kinds of contrast that make possible ‘genuine symphonic thinking’. The music is ‘one-dimensional in its processes’.Footnote 126 A routine had apparently set in, which Bridge can be seen to unsettle deliberately for the first time in those compositions from the period of the First World War in which he shifts his points of stylistic reference to the latest music of Debussy and Scriabin: in the orchestral Dance Poem (1913); the first of the Two Poems (1915), again for orchestra alone; and in the piano miniatures gathered as Three Poems (1913) and Four Characteristic Pieces (1915). In his music of the 1920s and 1930s, Bridge severed the lucrative commercial link he had previously enjoyed with the musical public as the composer of ‘salon’ pieces for piano and songs. Freed by the patronage of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge from the need to write for money, he composed a series of works whose reception was marked, in good modernist style, by audience hostility and critical rejection. As Frank Howes was to write with notorious incomprehension, Bridge ‘began to uglify his music to keep it up to date’.Footnote 127

What kind of modernist was he? For Payne, Bridge's middle years were a ‘journey towards self-discovery’. The critic praises the composer for his ‘willingness to place integrity of personality at risk, by identifying with other styles’.Footnote 128 There are Freudian hints here. In his early work, Bridge is held to have ‘suppressed’ the ‘dark sources of inspiration and revelation’ characteristic of ‘the deeper recesses of his personality’. Only in the 1920s did he find himself able ‘to balance his rational and orderly flow of ideas with a dark, irrational fantasy’.Footnote 129 Yet the notion of ‘balance’ sits uncomfortably with the conception of modernism outlined above. The Piano Sonata may give us the eruption of ‘the full force of Bridge's creative personality’;Footnote 130 by the same token, the music would seem to be graspable in terms of the deepening expression of a single creative voice. There is no requirement to go beyond the notes, to call upon notions of ‘truth’ or ‘the Absolute’ in order adequately to sum up this composer's achievement.

Some words of another critic of the late 1970s, the moment of Bridge's belated ‘rediscovery’, suggest agreement with this assessment. ‘Bridge's music’, writes Hugh Wood (like Payne also a composer), ‘sounds professional to a degree that the music of all too many of his contemporaries simply did not. His music really works, and you don't find yourself having to make allowances for naïve lovableness or primitive folksiness or the greyness of everything doubled at the octave or overscored.’Footnote 131 The polemical intent here is all too clear. But there is another way to look at these same issues. Here is one of Wood's targets, Vaughan Williams himself, writing in the early 1930s to another, Gustav Holst, apropos of John Ireland's ‘early’ Violin Sonata (presumably the D minor of 1905–6), the outer movements of which Vaughan Williams considered ‘a little spoilt by the desire to shine & show he understands the instrument’:

I wonder how much a composer ought to know instrumental technique – do you remember we had a long talk about that last year – of course the deepest abyss of the result of writing effectively is Frank Bridge – but there is a slight snobbishness about Ireland's music which worries me if you know what I mean.Footnote 132