Older adults in nursing homes are predisposed to healthcare-associated infections due to a multitude of risk factors including multiple comorbid conditions, indwelling devices, more frequent hospital visits, functional impairment, and increased use of medications including antibiotics.Reference Montoya and Mody 1 , Reference Strausbaugh and Joseph 2 An estimated 2 million infections occur in US nursing homes each year, increasing mortality, antibiotic resistance, and healthcare costs.Reference Montoya and Mody 1 – Reference Herzig, Dick and Sorbero 5 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most common pathogenic organism, and up to 58% of nursing home residents are reported to be colonized with MRSA.Reference Dantes, Mu and Belflower 4 , Reference Evans, Kralovic and Simbartl 6 , Reference Stone, Lewis and Johnson 7 In healthcare settings, MRSA is mainly spread by person-to-person contact, most often between healthcare workers (HCWs) and patients, and by indirect contact with contaminated environmental surfaces and fomites. Many acute-care hospitals attempt to limit the spread of MRSA and other multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) by using contact precautions for patients colonized or infected with MRSA.Reference Siegel, Rhinehart, Jackson and Chiarello 8 In nursing homes, contact precautions are less desirable because of the communal setting and the emphasis on a homelike environment. Potential disadvantages of placing nursing home residents in isolation include stigmatizing residents, fewer HCW visits, increased costs, and greater burden on staff.Reference Morgan, Diekema, Sepkowitz and Perencevich 9 – Reference Dumyati, Stone, Nace, Crnich and Jump 13 Using isolation on nursing home residents might undermine the goal of emulating a homelike setting, creating significant challenges for infection prevention programs.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates 133 community living centers (nursing homes), which provide care for up to 12,000 veterans per day.Reference Evans, Kralovic and Simbartl 6 , Reference Tsan, Langberg and Davis 14 In these nursing homes, the VA is committed to providing veteran residents with long-term, skilled nursing and rehabilitative care in a homelike setting. The VA practice differs from most non-VA nursing homes, where active surveillance is rarely performed and under a third report using isolation for residents with MDRO carriage.Reference Cohen, Dick and Stone 12 , Reference Ye, Mukamel, Huang, Li and Temkin-Greener 16

In this study, our objective was to conduct direct observation of HCWs in the nursing home setting to measure frequency and duration of resident contact and infection prevention behavior as a factor of isolation status.

METHODS

This observational study was conducted over 15 months (February 2016 to April 2017) in 24 skilled nursing units in 8 VA nursing homes in 6 states: Miami, Florida; Boston, Massachusetts; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Baltimore, Maryland; Perry Point, Maryland; Vancouver, Washington; Kerrville, Texas; and San Antonio, Texas. Hospice and palliative care only units were excluded from observation. The VA Central Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from approval under category 2. During the study period, all VA nursing home facilities were required to perform MRSA active surveillance culturing on admission and to implement barrier precautions (often referred to as isolation) including gowns and gloves for most care of colonized or infected residents or contact with their environment. 15

Direct Observation

Trained research staff who did not have clinical responsibilities on the units randomly selected nursing home rooms from a list of rooms at their site. All observers completed “secret shopper” observation training with the data collection tool and worked with a supervising local primary investigator. Each observation lasted 15–30 minutes. Observers recorded time of entry and exit, isolation status, visitor type (HCW, staff, visitor, etc), hand hygiene, use of gloves and gowns, and care activities performed in the room when visible using a standard form. Care activities observed were bathing, hygiene, toileting, feeding, dressing change, transfer, IV care, medications, Foley catheter care, physical exam, glucose monitoring, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and respiratory care. Observations did not include resident–provider encounters outside resident rooms.

For this study, nursing home staff and visitors were considered compliant with isolation precautions if they donned gloves and gowns at time of room entry or were observed using gowns and gloves within the resident room when care activities were observed or the environment was touched. Nursing home staff and visitors were considered compliant with hand hygiene if hand hygiene was performed immediately before or after entering or exiting a resident room during observations where any care activities were observed or the environment was touched. We did not observe all World Health Organization (WHO) 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene because in-room observation would not be possible without being conspicuous.Reference Chang, Reisinger and Jesson 17 We did not inform nursing home staff of observation.

We defined HCWs as medical doctors or medical students (MDs), registered nurses (RNs), or patient care technicians (PCs). All other visitors were considered non-HCWs.

Isolation Precautions

We collected and reviewed the isolation policies from each participating nursing home. All nursing homes have similar policies for infection control precautions for MDRO residents, as recommended by the VA. 15

Statistical Analyses

The average number of visits per hour of observation was calculated. Care activities were calculated as a proportion of total visits. Visits per hour and care activities were compared between isolation and nonisolation observations using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test after testing the normality of the distribution. Compliance with hand hygiene was calculated as a proportion of hand hygiene observed of opportunities observed and compared between isolation and nonisolation observations using a χ2 test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In-Room Observation Data

In total, 999 hours of observation were conducted across 8 VA nursing homes, during which 4,325 visits were observed. The hours observed at each site ranged between a minimum of 35 hours and a maximum of 222 hours, with a median of 114 hours per site. Observations occurred between 7:00 am and 6:00 pm. There were 677 hours observed for rooms of residents not in isolation and 322 hours observed for rooms of residents in isolation. Of 4,325 visitors observed, 3,084 (70%) were HCWs.

Frequency and Duration of Visits

Residents on any type of isolation received an average of 4.73 visits per hour of observation compared with 4.21 for nonisolation residents (P<.01), a 12.4% increase in visits for residents in isolation (Table 1). A similar result was seen in average number of HCW visits per hour, which were 15.1% higher in residents in isolation than those who were not (3.43 vs 2.98; P<.01). Non-HCW visits per hour were not significantly different, averaging 1.22 visits per hour in nonisolation residents and 1.30 in residents in isolation (P=.12).

For every hour of observation, residents on any type of isolation received an average of 22.1 visit minutes compared with 19.9 visit minutes for residents not in isolation (P<.01). Healthcare worker visit minutes per hour were in line with this finding. Those in isolation received an average of 16.1 HCW visit minutes per hour compared with 12.6 for residents not in isolation (P<.01). Non-HCW visit minutes per hour were not significantly different, averaging 5.9 for residents in isolation compared with 7.3 visit-minutes per hour for residents not in isolation (P=.20).

TABLE 1 Visits Per Hour and Minutes of Healthcare Worker (HCW) Contact by HCW Type for Isolated and Nonisolated Residents

Note. MD, medical doctor; RN, registered nurse; PC, patient care technician.

Resident Care Activities

Residents in isolation received, on average, 3.53 resident care activities per hour of observation, compared with 2.46 for residents not in isolation (P<.01). The 5 most common resident care activities were the same for residents in isolation and nonisolation. For residents in isolation, the most common care activities in order were (1) oral medication, (2) assistance with toileting, (3) hygiene, (4) transfer, and (5) physical exam. For residents not in isolation, the most common care activities were (1) oral medication, (2) transfer, (3) physical exam, (4) assistance with toileting, and (5) hygiene. For all of these activities except for physical exam, residents in isolation had significantly higher numbers of activities performed when compared with residents not in isolation (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Proportion of Healthcare Worker (HCW) Contact by Type of Resident Care and Isolation Status

Gown and Glove Compliance

For residents in isolation, gowns and gloves were indicated when resident care was given or the environment was touched (N=1,368). For residents in isolation, gowns were worn for 469 of 1,368 visits (34%), and gloves were worn for 793 of 1,368 visits (58%). For residents not in isolation where neither gowns nor gloves were required, gowns were worn for 62 of 2,538 visits (2.4%), and gloves were worn for 946 of 2,538 visits (37.3%).

Hand Hygiene

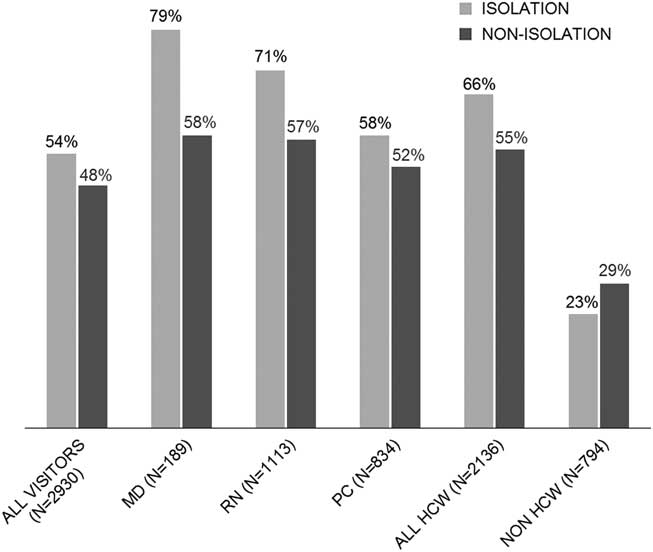

Hand hygiene opportunities were defined as observed entry and/or exit to resident rooms during a visit where resident care was given or the environment was touched. (Figure 1; Table 3). The overall compliance rate with hand hygiene on room entry was 38% (1,113 of 2,920 observed opportunities) and was 50% (1,476 of 2,930) on room exit. For residents in isolation, the compliance rate was 38% (399 of 1,047) on room entry and was 54% (558 of 1,024) on room exit. For residents not in isolation, the compliance rate was 38% (714 of 1,873) on room entry and was 48% (918 of 1,906) on room exit. Hand hygiene compliance on entry between residents in isolation and residents not in isolation was the same (38% vs 38%; P=.99). On room exit, hand hygiene compliance was significantly better for residents in isolation than residents not in isolation (54% vs 48%; P<.01).

FIGURE 1 Hand hygiene compliance on exit for isolation versus nonisolation status by type of healthcare worker. NOTE. HCW, healthcare worker; MD, HCW provider; RN, registered nurse; PC, patient care technician.

TABLE 3 Hand Hygiene (HH) Compliance on Room Entry and Exit by Type of Visitor for Residents in Isolation Versus Nonisolation

Note. HCW, healthcare worker; MD, medical doctor; RN, registered nurse; PC, patient care technician.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the effect of isolation precautions on HCW resident interactions across 8 VA nursing homes in the United States. Residents were primarily in isolation due to MRSA colonization. Isolated residents generally required more care and were seen more often by HCWs. Moreover, HCWs wore gowns 34% of the time and wore gloves 58% of the time when caring for residents in isolation. Gloves were worn during the care of 37% of nonisolated residents. Overall hand hygiene compliance was 38% on entry and 50% on exit. Encouragingly, hand hygiene compliance was clearly better for HCWs versus non-HCWs. Also, HCW compliance with hand hygiene was slightly higher after visiting isolated residents.

Residents in isolation received more HCW visits than residents not in isolation. Studies of acute care have consistently found fewer visits for residents who were in isolation, presumably due to the effort required to don gloves and gowns.Reference Harris, Pineles and Belton 18 , Reference Morgan, Pineles and Shardell 19 We hypothesize that more contact was observed because residents colonized with antibiotic-resistant bacteria may be more dependent on staff for care and assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs). In this study, residents in isolation received more visits for hygiene, toilet assistance, transfers and giving oral medications, mostly from patient care technicians and nurses, supporting this hypothesis. Also, in a large retrospective study of non-VA nursing homes, Cohen et alReference Cohen, Dick and Stone 12 found that less independence with ADLs was associated with isolation.

The rate of compliance with gowns and gloves was low, but it was consistent with other studies of resident isolation.Reference Dhar, Marchaim and Tansek 20 , Reference Anderson, Weber and Sickbert-Bennett 21 Likewise, compliance with hand hygiene was lower than often reported; however, our compliance rate was within the range of what is reported when more rigorous, secret shopper methodology is used.Reference Montoya and Mody 1 , Reference Schweon, Edmonds, Kirk, Rowland and Acosta 22 Notably, patient care technicians have a low compliance with hand hygiene that was not impacted by isolation status; this may indicate an opportunity for further education in this group. Our findings of lower compliance on entry as well as a small increase in compliance on exit when residents are isolated was consistent with other studies.Reference Thompson, Dwyer, Ussery, Denman, Vacek and Schwartz 23 , Reference Mody 24 The finding that hand hygiene increased after glove use could be due to the HCW perceptions of being more contaminated after caring for residents on isolation. Previous studies in acute-care settings yielded similar results.Reference Harris, Pineles and Belton 18 , Reference Almaguer-Leyva, Mendoza-Flores and Medina-Torres 25 These findings suggest that focusing efforts on proper precautions during high risk for contamination activities and basic hand hygiene rather than resident-directed activities may be useful. In late 2016, the VA revised its Community Living Center MRSA Prevention Initiative to define certain activities (eg, giving oral medications as “low risk” for transmission) that do not require gowns and gloves, reducing the burden on HCWs. 26 However, gowns and gloves are still recommended for most care activities for residents colonized or infected with MRSA or other antibiotic resistant bacteria.

One limitation of our study may have been the use of “secret shoppers.” In reality, these observers were most likely recognized as some type of external monitor given the relatively small staff and less busy hallways at nursing homes compared to acute-care facilities. However, being recognized as an observer would be expected to have increased compliance due to the Hawthorne effect. Another limitation is that observations did not include the evening shift when less staffing may affect compliance with isolation and hand hygiene.

Additionally, our results may not generalize to non-VA nursing homes as the approach to isolation in the VA is more comprehensive than most nursing homes, using both active surveillance for MRSA and gowns and gloves for most care of residents found to be positive. Although we were not able to observe the WHO Five Moments of Hand Hygiene, we were able to limit hand hygiene compliance opportunities to visits where resident care was performed or the environment was touched, eliminating instances where hand hygiene may not be indicated. Also, all observations were of residents in their rooms. Residents in nursing homes have many interactions in common areas which potentially may play a greater role in transmission. A strength of our study was the rigor of independent observation; we formally trained research staff for observations and standardized data collection in 8 geographically diverse nursing homes.

In summary, a comprehensive approach to the use of contact precautions in nursing homes was associated with limited compliance with gown and glove use, did not appear to negatively affect frequency of visits and was associated with improved hand hygiene. However, adherence to hand hygiene was less than optimal, regardless of the isolation status of residents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the study coordinators Jwan Mohammadi (Oregon), Diana Sams (Michigan), Melissa Hibner (Texas), Carol Ramos (Florida), Alexandra Rochman (Massachusetts), Corey Lonberger (Massachusetts), Makaila Decker (Massachusetts), and Georgia Papaminas (Maryland). The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Financial support: This work was supported by Collaborative Research to Enhance and Advance Transformation and Excellence (CREATE) Initiative (grant no. HX-12-018) and Merit Review (grant no. I01 HX001128) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D).

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.