This law makes business a team player in labor relations, legislating decent work and improving the rules of the game for those who most need it.… In a country where things are going well, it is fundamental that we do not have first and second class workers, and without doubt, this law is a clear, decisive, and definitive step in that direction.

—President Michelle Bachelet, signing the Law on Subcontracting (La Nación 2006a)

We want Peru to grow for everyone, to advance with its workers and to eradicate and eliminate the slavery of the 21st century, which is subcontracting and the cover-up of workers. I think this is an objective that everyone with a sense of good will, compassion and social justice agrees on.

—President Alan García, signing the Law on Labor Outsourcing (Andina 2008a)

In June 2007, 28,000 workers at the Chilean state copper company, Codelco, went on strike for 37 days. The miners clashed with police, blocked roads, and torched buses, demanding improvements in pay and benefits. The conflict ended when Codelco’s management agreed to a package of benefits that would cost the company $30 million per year. Though a typical labor conflict in grievances and actions, there was an important difference: subcontractors, not Codelco, employed the workers (El Mercurio 2007a, b).

In the 1980s and 1990s, Latin American governments advanced measures to improve labor market flexibility through the promotion of temporary, fixed-term, and subcontracted employment. In many countries, rigid formal labor laws and contributory benefits favored by unions remained on the books. However, businesses increasingly turned to contract workers to bypass regulations. Contract workers hold written contracts but often lack labor stability, welfare benefits, and collective organizing protections. Roughly a fifth of Latin America’s workforce currently works in a formal firm without a long-term labor contract (ILO 2011). In some countries, like Peru and Ecuador, most workers with formal labor contracts hold temporary positions (Maurizio Reference Maurizio2016, 16).

Much of the existing literature takes the expansion of workers with unstable labor contracts as a new permanent feature of Latin American political economies. The usual assumption is that the segmentation of the labor market makes it difficult to identify coherent interests or organize collective action among unionized and contract workers. Etchemendy and Collier (2007), for instance, identify a “dilemma of working-class representation,” in which workers with precarious contracts lack the political connections, organizational structures, and shared class interests to better their lot. Unionized workers are thought to prioritize the stability and perquisites of their jobs over the interests of more precarious workers, either in the informal sector or on short-term contracts (Murillo 2001; Rueda Reference Rueda2007). Collective action led by unions to protect workers with insecure contracts seems unlikely.

When does collective action occur between unionized and contract workers? And when does it result in labor policy change? I argue that flexibility reforms from the neoliberal period induced changes in union interests. Unions initially accepted flexible labor contracts as a necessary compromise to preserve their own members’ benefits. But firms started to replace union jobs with contract ones, resulting in diminished union membership, wage pressure, and replacement risks. Union leaders then started to see the mobilization and improved conditions of contract workers as critical to their own bargaining power. Collective action started in sectors where unionized and contract workers shared physical workspaces and labor histories, such as mines and factory floors.

Joint mobilization has resulted in changes to labor laws when timed to exploit electoral openings. Although some scholars see mobilization as sufficient for policy change (Donoso and von Bülow 2017; Durán Palma and López 2009), conservative politicians and business groups defend flexible contracts as key to economic growth. To overcome opposition, labor organizations have broadened their coalitions. The numeric importance of contract workers creates electoral pressure for politicians to advance new regulations and for left-wing politicians to express ideological commitments to a broader class of workers. Unions have timed strikes to coincide with presidential elections to underscore the electoral salience of the issue. Additionally, unions sometimes have leveraged splits within the business community. Some multinational firms favor regulations on contract work to equalize conditions with domestic firms that often make more aggressive use of contract hires.

This study develops these arguments through a paired case comparison of two least likely cases for labor mobilization: Chile and Peru. Chile gutted its labor movement under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973–90), and Peru weakened unions under the competitive authoritarian regime of Alberto Fujimori (1990– 2000). These democratic interruptions led to radical reforms to make labor markets more flexible. This study uses process-tracing methods to demonstrate how union preferences evolved with time and how broad coalitions succeeded in passing contracting reforms. I looked for evidence on how union leaders perceived the interests they shared with contractors, why they shifted with time, and how they timed their mobilizations with respect to elections. To do so, I drew on interviews with labor leaders and politicians, as well as newspaper articles, labor market statistics, and union and government reports.

While Chile and Peru share weak labor movements and enduring neoliberal reforms, they diverge in their political party structure. Programmatic left parties often are seen as essential for the defense of organized labor’s interests (e.g., Cook Reference Cook2007; Murillo 2001; Roberts Reference Roberts1998). Chile had a programmatic left that offered a stable ally for organized labor through the 2000s. In contrast, Peru’s party system collapsed. The comparison thus allows me to rule out that a strong left party is a necessary condition for contract reform. Instead, I highlight how a unified labor movement can appeal to electorally motivated politicians and leverage divisions within the business community to pass contracting reforms.

The main contribution of this article is to demonstrate the growing political importance of contract workers. While it is not the first study to notice the growth of subcontracted and temporary workers (e.g., Karcher Reference Karcher2014; Schneider Reference Schneider2013; Schneider and Karcher Reference Schneider and Karcher2010; Sehnbruch et al. Reference Sehnbruch, Pablo González, Méndez and Arriagadae2020), it demonstrates their importance for the labor movement and policy reform. It uses the case studies to build hypotheses about when joint organizing between unionized and contract workers is likely to occur and result in policy change. The conclusion returns to the importance of future research on the extent to which policy preferences differ by contract status, the frequency with which unions ally with contract workers, and the variation in contract regulations and their enforcement across Latin America.

Contract Work and Its Regulation in Latin America

The traditional division between formal and informal work glosses over an important third sector: individuals who work for formal firms but who lack the job stability, benefits, and rights provided to more traditional employees. In many cases, what I will call a principal firm hires a legally constituted intermediary firm (a subcontractor or temporary employment agency), which supplies the workers to the principal firm. The workers hired by intermediaries may be exempt from collective organizing and social benefits de jure or de facto. In other cases, the principal firm hires workers directly on short-term contracts to do work like that performed by full-time employees. I use the term contract workers to encompass this variety of nonstandard labor arrangements, including subcontracted, temporary, fixed-term, or gig workers. The position of contract workers in the labor market can be understood by separating legal and benefit definitions of informality, as proposed in the introduction to this special issue (on the contrast in definitions, also see Gasparini and Tornarolli Reference Gasparini and Tornarolli2009; Perry Reference Perry2007). The first dimension considers whether a contract complies with state laws and regulations. As Portes and Castells (Reference Portes and Castells1989, 12) put it in their classic definition, informal activities are “all income-earning activities that are not regulated by the state in social environments where similar activities are regulated.” Small businesses that evade taxes or street vendors who violate property laws are classic examples of informal activities. In contrast, precarious contracts can be consistent with state laws.

In many cases, new contract forms arose during labor law reforms in the 1980s and 1990s to lower business costs and reduce benefit obligations. Although an individual contract may be legal, it can perpetuate informality: for instance, a firm may subcontract to another legally constituted firm (a fully legal contract), and the intermediary firm then can supply workers without labor rights or benefits to work at the principal firm (for examples, see Levy Reference Levy2008; Portes and Schauffer Reference Portes and Schauffer1993).

The second dimension considers whether individuals have access to welfare benefits. With the growth of precarious contract types, some workers have formal legal contracts that do not include social benefits. They might earn too much to qualify for noncontributory systems while lacking a permanent contract to access contributory systems. Principal firms also sometimes exploit ambiguity in the law about which firm (the principal or the intermediary) is responsible for social benefits for contract workers (Tokman Reference Tokman2007). Table 1 maps these two dimensions and highlights that this article focuses on contract workers who have a legal work status yet are excluded from important benefits and rights.

Table 1. Disaggregating Benefit and Labor Informalities

In most cases, contract workers enjoy reduced benefits and rights compared to workers with stable, full-time contracts. As Karcher (Reference Karcher2014) puts it, the result is the growing segmentation of Latin American labor markets (through the expansion of legal but flexible labor contracts), rather than its informalization (through noncompliance with labor laws). Existing work on segmentation, or what European scholars refer to as dualization, emphasizes that differences in labor status result in conflicting preferences and divisions among workers. For instance, Rueda (Reference Rueda2007) suggests that labor market “insiders” prefer strong employment protections over flexibility, while contract workers prefer policies that ease the reentry of “outsiders” into the labor market. Other scholars soften this argument, suggesting that unions do not oppose the extension of rights and benefits to contract workers. Instead, they defend their traditional institutions and practices while allowing for substantial change and growth in precarious work contracts. They rarely mobilize or take broader legislative initiatives on behalf of contract workers (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Schneider and Karcher Reference Schneider and Karcher2010, 643).

Whether contract and unionized workers hold conflicting preferences in Latin America is an open empirical question. Divisions among types of workers may be overstated. For instance, Baker and Velasco Guachalla (2018) find that formal and informal workers differ little in their policy preferences and political organizing. However, they are not able to differentiate contract workers from those with stable positions. Their null results could stem from the measurement challenge that many workers at formal firms hold short-term positions that could move their preferences and behaviors closer to those of self-employed, informal workers (Baker and Velasco Guachalla 2018, 180). In this spirit, Carnes and Mares (Reference Carnes and Mares2014) suggest that unionized and precarious workers share preferences to extend noncontributory social policy benefits, given the increased risk of possible job loss. Unfortunately, no public opinion data are available on contract workers to directly test if and how their preferences differ from workers with stable, long-term contracts.

What is clear is that contract work constitutes a growing share of the Latin American labor market. The International Labor Organization (ILO) has attempted to distinguish between employment in the informal sector, meaning jobs in unregistered or small private enterprises, and informal employment in the formal sector, meaning jobs that lack basic social and organizing protections that occur in registered or large firms. The latter is a reasonable proxy for contract work. Again, these are cases where labor contracts comply with state regulations, making workers “formal” according to legalistic definitions but “informal” according to benefit-based definitions.

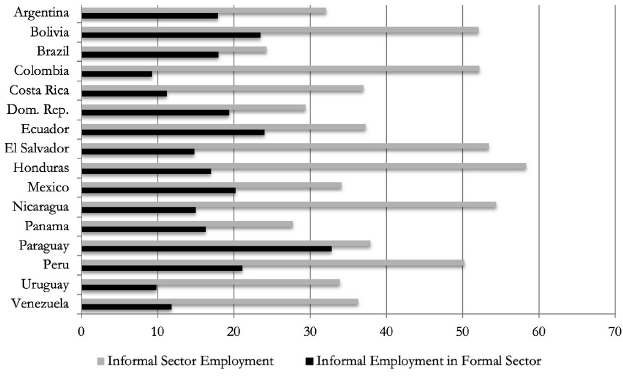

Figure 1 plots these distinctions for the select Latin American countries for which they are available for the period studied (2000–2010). The black bars indicate individuals who lack contributory social benefits but who work in registered firms, or what the ILO calls informal employment in the formal sector. The gray indicates individuals in small firms, or what is more typically measured as the informal sector. Informal work in formal firms constitutes a substantial portion of the labor force, ranging from a low of 9 percent in Colombia to a high of 33 percent in Paraguay. Analysts thus miss a substantial fraction of the workforce that often lacks benefits and organizing rights when studying self-employed informality alone.

Figure 1. Informal Employment in the Formal Sector (Contract Work) and Informal Sector Employment (Self-Employment and Small Businesses) as a Percentage of Nonagricultural Employment

Notes: Informal employment in the formal sector includes jobs in formally constituted enterprises that lack basic social or legal protections or employment benefits; informal employment includes jobs in unregistered or small/unincorporated private enterprises. Data are only available for select Latin American countries.

Source: ILO Department of Statistics 2011

Another way to understand the prevalence of contract work is to look at average job tenure. In the 2000s, the median tenure for workers was just three years in Latin America, well below the average in advanced industrial economies (Schneider and Karcher Reference Schneider and Karcher2010, 628). In the 2010s, data from nine Latin American economies show that a third of workers stay in their jobs for less than three years, which is the critical cut-off to access severance payments (Sehnbruch et al. Reference Sehnbruch, Pablo González, Méndez and Arriagadae2020, 10). These statistics give a sense of the large number of workers who rotate through work positions, often on nonstandard contracts (but also through dismissals right before they gain labor benefits).

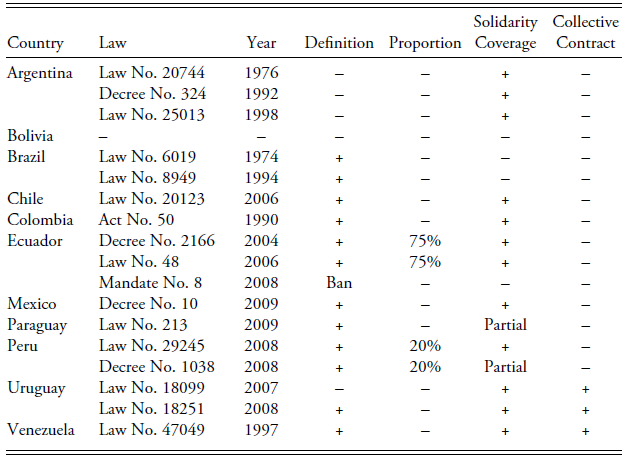

Many Latin American governments regulate contract work through detailed national legislation. Table 2 shows the prevalence of regulations based on an original compilation of legislation. It focuses on subcontracting regulations, which often also include rules for temporary and fixed-term work. I looked for the first major efforts to restrict subcontracting use in each country. I coded whether the regulations include four key provisions. First, I checked whether the regulations have definitional clauses. Most laws limit subcontractors to independent and autonomous companies that provide their own capital, management, and workers. Almost all Latin American countries now define subcontracting, though they vary in how they enforce classifications.

Table 2. Regulations on Subcontracting in Latin America

Source: Author’s compilation based on searches of national legislation.

Note: +/– indicates the presence/absence of a legal provision.

Second, governments can impose quantity restrictions on contract work. For example, proportion clauses cap the percentage of subcontracted workers who can be employed in a workplace. The goal of these provisions is to limit the impact on worker organizing, though some countries make it a trivial requirement through high caps. For instance, Ecuador limited subcontractors to 75 percent of the workforce in 2004.

The third common type of regulation shifts responsibility for labor rights violations to the primary firm that employs contractors through intermediaries. Many regulations require solidarity coverage in which the principal firm assumes responsibility if an intermediary subcontractor fails to provide social security contributions, labor benefits, or minimum wage payments to its workers. Reforms have extended solidarity responsibility in Chile, Uruguay, Venezuela, Mexico, and Ecuador.

A final provision extends to contract workers the right to organize and bargain collectively as part of the principal firm. The most common provision requires companies to extend to contract workers union contract provisions relating to working conditions and safety standards. Very few countries explicitly require workers hired by intermediary firms to be covered by collective bargaining agreements at the principal firm; this mandate has been applied only in Venezuela and Uruguay. The ability of unions at a principal firm to organize contract workers hired by intermediaries is one of the features most desired by unions that seek to expand their membership and reach.

Latin America is not unique in the growth of contract work or attempts to regulate its use. US capitalism also is defined by a new “labor precariat” composed of independent contractors, without full labor rights or benefits (Thelen Reference Thelen2019). European political economists have noted the growth of workers with irregular contracts in “dual” labor markets (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Rueda Reference Rueda2007). Reversing these trends often depends on unions’ ability to lead collective action and form alliances with contract workers. For instance, Levi (Reference Levi2003, 45) underscores that it is critical for organized labor to become a social movement, able to organize others and fight for better conditions for all.

The Argument

When do unionized workers mobilize alongside contract workers? And when do their demands for contract regulation succeed? I make a two-step argument. First, I suggest that unionized workers mobilize contract workers to avoid replacement risks. When contractors are used to substitute for union jobs, labor unions are most likely to see their interests threatened by contract work. These threats are most apparent when unionized and contract workers share a physical workplace. Second, organized labor is most likely to succeed in passing new regulations when it can exert electoral pressure, especially on left-wing politicians, through protests timed around elections. Broad coalitions of political and business allies also make legislative change more likely. Multinational firms may support contract regulations to synchronize national legislation with their own codes of conduct.

The incentives for unions to defend contract workers come from the impact on collective organizing. Contract work can be used to lower labor costs, as well as to weaken unions. For example, a principal firm that uses subcontracted or temporary workers has no direct employment relationship with the workers. Contract workers must negotiate and bargain collectively with the intermediate firm that directly employs them; i.e., a subcontractor or temporary employment agency. Contract work also can reduce the workforce covered by collective agreements or block unionization altogether. Ecuador, for instance, sets the number of workers required for an establishment to unionize at 30. A company can subcontract to shell companies, each of which encompasses fewer than 30 workers, and thus prevent the formation of a union altogether.

Unionized workers can defend the rights of contract workers without explicit harm to their own working conditions. The creation of nonstandard contracts is often analyzed with a broader set of “flexibility” policies, such as reductions in severance pay, changes in dismissal policy, and so on (e.g., Cook Reference Cook2007, ch. 1). But atypical contracts must be disaggregated from other flexibility policies because they do not directly affect the terms of unionized labor contracts. Flexible contracts thus conform to a different political logic from flexibility reforms, which affect the terms of all individual employment contracts and require sacrifices from unionized workers.

Unions push to regulate flexible contracts as the impacts on collective organizing become apparent. When flexible labor contracts are first proposed, unions often accept them to maintain their own perquisites and avoid other reforms. As Schneider and Karcher (2010, 643) describe Latin American labor reforms, “Embattled unions focused on defending their insider, core constituents.” New labor contracts are layered on top of existing union job protections and used to satisfy business demands for flexible hiring without reducing severance pay or other benefits. However, as flexible contracts are used to replace union jobs, unions increase their opposition and look to mobilize contract workers in favor of reform. Therefore my first hypothesis is that unions attempt to mobilize contract workers once their own membership is threatened.

There are many barriers to collective action between unionized and contract workers. Some contract work fragments the workforce by asking workers to use their own equipment or spaces, such as piecemeal work from home or ride-sharing platforms in which drivers provide their own cars. The physical separation of workers makes collective action more difficult because workers cannot converse or learn about the discrepancies in conditions. For these reasons, organizing in the informal sector, particularly for workers who do not share physical spaces, like street-vending associations, is thought to be difficult (Kurtz 2004; Roberts 2002; cf. Hummel Reference Hummel2017). Flipping the logic, I expect that collective action is most likely between unionized and contract workers when they share physical workplaces and when unions recognize the direct membership threats.

The second piece of the argument considers when labor mobilization results in policy change. I expect labor mobilization to lead to regulations on contract work when broad coalitions are constructed that include left-wing politicians and parts of the business community. Politicians on the left may be more likely to believe that higher labor standards will improve workers’ lives for ideological reasons, whereas politicians on the right may be more concerned about the employment effects of new regulations. Yet given the numeric importance of contract workers, politicians across the ideological spectrum also can see an electoral incentive in advocating regulations that promise contract workers greater labor and organizing benefits. While the left may see little reason to compete for union votes in countries in which labor is a stable ally (Murillo 2001), it cannot count on the votes of contract workers. Politicians pressured to take a position on defending a broader class of workers may come to support greater rights to court their votes, a theory similar to Garay’s argument (2016) that competition over the votes of “outsiders” leads to the extension of social policy benefits. When unions can force the issue of contract regulation onto the agenda around elections, the chances of labor policy change improve. Thus, my second hypothesis is that labor mobilization is more likely to result in regulations on contract work when there is electoral competition for contract workers’ votes.

Organized labor also may attempt to leverage divisions within the business community. Many large multinationals have internal codes of conduct or follow labor laws in their home countries to limit the use of contract work (Schneider and Karcher Reference Schneider and Karcher2010). When this is the case, multinationals often advocate contract regulations that can equalize conditions between domestic and multinational firms. Labor actors also can build transnational labor alliances and draw on support from multinational firms in the context of free trade negotiations (Murillo and Schrank Reference Murillo and Schrank2005).

Contract Regulations with Programmatic Parties: Chile

Efforts to regulate subcontracting in Chile illustrate the power of coordinated mobilization between unionized and contract workers. Mobilization began in the mining sector, where workers shared conditions and labor histories. But initial attempts to push subcontracting reforms failed. Only when organized labor built broader coalitions with center-left politicians before presidential elections did new contract regulation overcome the reluctance of domestic business and conservative politicians.

Chile liberalized its labor laws ahead of the rest of Latin America. The military government passed a series of laws between 1979 and 1983, known as the Labor Plan, aimed to reduce labor costs and weaken the organized labor movement. The government also expanded the use of subcontracted, fixed-term, and seasonal work contracts (Durán-Palma et al. Reference Durán-Palma, Wilkinson and Korczynski2005, 70). Perhaps because the military dictatorship decimated labor protections for all workers, contract work represented a small fraction of the labor market throughout the 1980s. At the transition to democracy, only 8 percent of the active labor force worked as a subcontractor. Meanwhile, unionization rates dropped from a high of 30 percent in 1973 to a mere 8 percent in 1989 (Cook Reference Cook2007, 117–20).

Democratization resulted in union pressure to reinstate labor protections, though little change to contract work. In 1990, policies to increase employment ranked second in electoral priorities, just behind the control of inflation (CEP 1990). President Patricio Aylwin, a member of the center-left alliance of political parties, the Concertación, successfully introduced a set of reforms to increase severance pay, restrict firing to just cause, expand job security protections, and strengthen collective bargaining rights (Sehnbruch Reference Sehnbruch2006, ch. 3).

However, the new labor law showed substantial continuity with the one inherited from the dictatorship. No changes were made to subcontracting regulations, although the new law did set time and renewal limits on the use of fixed-term contracts (Durán-Palma et al. Reference Durán-Palma, Wilkinson and Korczynski2005, 73–79). Fierce opposition from business groups blocked initial attempts to restrict subcontracting. They credited flexible labor markets with Chile’s rapid growth. The centrist labor minister, René Cortázar, agreed that any reduction in flexibility could threaten economic competitiveness and employment levels (Barrett Reference Barrett2001, 585).

As the government gradually reinstated labor protections for salaried workers, alternative contracts increased rapidly. As figure 2 shows, subcontracting represented a third of the workforce by 1996, compared to just a fifth with stable labor contracts and less than a tenth in unionized positions (Schneider Reference Schneider2013, 174). The Labor Ministry called the expansion of subcontracting “the most radical change in employment in past years” (Echeverría Reference Echeverría1997). Labor surveys provide some indication that companies used irregular contracts to supplant permanent workers. Short-term contracts, for instance, were supposed to last a maximum of one year, renewable once. Yet a 2003 household survey showed that 36 percent of fixed-term, 22 percent of project-based, and 39 percent of “temporary” contracts had lasted more than two years. Workers complained that employers would hire them for a year, terminate the contract, and rehire them after one month (Casen 2003).

Figure 2. Subcontracted Workers as a Percentage of the Chilean Labor Force and the Codelco Labor Force, 1989–2010

Source: Author’s compilation from Chile’s Labor Directorate (Dirección del Trabajo de Chile) and Codelco annual reports (memorias anuales)

Union discontent with subcontracting and temporary employment began to build, due to its impact on collective organizing. The percentage of the labor force covered by collective bargaining agreements continued to drop, from 9 percent in 1990 to just 6 percent in 2001 (Durán-Palma et al. Reference Durán-Palma, Wilkinson and Korczynski2005, 87). A 1998 survey found that 44 percent of union members believed that subcontracting negatively impacted collective organizing and work conditions (Dirección del Trabajo Reference del Trabajo1998).

Some of the most dramatic changes in labor practices occurred in the copper industry, a historical center of Chile’s labor movement. In 1982, there were 187 permanent mining employees for every subcontracted worker; in 2006, there were two subcontracted workers for every permanent miner at the state mining company, Codelco. Subcontracting expanded from under 4 percent of the mining workforce to more than 30 percent (figure 2). Although no precise estimates are available, union leaders estimate that roughly half of subcontracted workers once were employed as permanent employees (Espinoza Reference Espinoza2012).

Unions initially disregarded the conditions of contract workers. For instance, the Copper Workers’ Federation (Federación de Trabajadores del Cobre, FTC) focused on representing its unionized workers in the 1990s and displayed a “strictly private orientation to interest representation, speaking only for Codelco’s direct blue collar workers” (Durán-Palma 2011, 189). Union leaders across industries showed little concern for low membership numbers and growing contract work (Gutiérrez Crocco Reference Crocco2016).

In the 2000s, however, the main labor confederation, the United Workers’ Central (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores, CUT) began to recognize that contract work gutted their ranks. CUT President Arturo Martínez acknowledged that the confederation was slow to realize the impact of contract labor on the union movement: “We didn’t see how it impacted our membership at first; we thought subcontracting would just be a minor issue and a necessary concession as we worked to restore our key labor rights” (Martínez Reference Martínez2010). But then the CUT saw that subcontracts were used for what “should have been unionized jobs” (La Nación 2006b).

The growing number of contract workers also began to shift the FTC’s position. The FTC pressured Codelco for the right to organize subcontracted workers as part of the federation. Under the threat of a strike by the FTC, Codelco agreed that subcontracted workers could join the FTC. This choice provided a direct organizational vehicle to link labor interests across unionized workers and contractors in practice working for the same principal firm.

Building on its industry-level gains, the FTC began to push for national regulation of subcontracting during the presidential campaign of Ricardo Lagos in 2000. Electoral pressures contributed to the government’s decision to push subcontracting regulations. When interviewed, Lagos noted pressure from the FTC to propose subcontracting regulations, but he stressed that a broader electoral calculation to defend “the fastest-growing” segment of the labor market drove him to support contract regulations (Lagos Reference Lagos2013). In a tightly fought race, there were incentives to appeal not only to the left’s core constituency among unionized workers but also to appeal to the numerically large group of contract workers. Of course, it is difficult to know the extent to which politicians followed their ideological convictions versus their electoral motivations in pushing subcontracting regulations. No electoral data exist to show whether subcontracting regulations played a role in the voting behavior of contract workers.

Upon election, Lagos sent a draft law on subcontracting to Congress. The law would have defined subcontracting, fined companies for subcontracting routine tasks, and allowed subcontracted workers to engage in collective bargaining at the principal firm. The proposal floundered, however, due to strong opposition from business groups, conservative legislators, and factions of Lagos’s coalition. Businesses argued that subcontracting regulations would harm employment generation, shutter small businesses, and eliminate work possibilities for vulnerable sectors. A severe economic crisis in 1999 made concerns about unemployment salient (Durán-Palma et al. 2005, 79).

Stymied by conservative opposition and concerns about protecting Chile’s economic record, Congress passed a watered-down provision that allowed subcontracted workers to organize if the principal firm consented. Unions were to monitor employers to see that subcontracting was restricted to complementary positions at the principal firm, but they lacked legal teeth or clear definitions (Echeverría 2009). Lagos blamed right-wing legislators for butchering the proposed subcontracting law (Lagos Reference Lagos2013). But even some left-wing legislators voted against the law out of concerns that it would increase labor costs, endanger the country’s economic model, and jeopardize a broader labor reform bill (Durán-Palma et al. Reference Durán-Palma, Wilkinson and Korczynski2005, 81). The failure of the subcontracting regulations showed that labor mobilization alone could not generate sufficient pressure to change the law, in contrast to explanations that focus exclusively on the growing strength of social movements (e.g., Donoso and von Bülow 2017; Durán-Palma and López Reference Durán-Palma and López2009).

The labor movement redoubled its attempts to build political and business alliances to pressure for contract work. Copper workers, who labored alongside subcontracted workers, again brought attention to contract work through a national strike during the 2006 presidential campaign. The CUT joined calls for new regulations. It argued that 60 percent of its copper industry members should enjoy a direct employment relationship with the principal firm, or more than 18,000 workers in an industry of 30,000 workers. But it also expanded its appeals to regulate subcontracting beyond the mines. As CUT president Martínez told the press, “Our fight is for decent work with just compensation and social coverage for all.… The proliferation of intermediaries, contracted, and subcontracted workers has only served so that business owners hide and escape their obligations” (La Nación 2006b).

The timing of the strike made contract work a salient electoral issue. During the 2006 presidential campaign, the Concertación’s candidate from the Socialist Party, Michelle Bachelet, appropriated organized labor’s theme of the expansion of decent employment to contract workers. Again, there was an electoral incentive to defend contract workers: as the unionized workforce dwindled, the Concertación could gain votes by appealing to contract workers. Roughly a third of all workers had seen their labor contracts become more precarious (Casen 2003). Bachelet therefore promoted the elimination of what she called “second-class” labor contracts, on the campaign trail and in the face of criticism (La Nación 2006c). Bachelet decried labor subcontracting as an “artificial loss of the right to bargain collectively and to unionize” for more than one-and-a-half-million workers (La Nación 2006a). While Bachelet may have favored broader labor rights for ideological reasons, she also used the issue to differentiate the Concentración from the right-leaning Alianza and strengthen her claims to represent low-income Chileans.

Bachelet made a law on subcontracting the first legislative initiative of her presidency. The legislation defined subcontracting, imposed solidarity requirements on hiring firms, created a registry of temporary and subcontracting agencies, and allowed labor inspectors to order the incorporation of subcontracted workers if employers were found in violation of limitations on their use. Unlike the 2000 initiative, these measures divided the business community. Several business organizations, including the National Mining Society and the Chamber of Commerce, voiced opposition, foreseeing a loss of competitiveness. But the CUT encouraged other prominent businesses, primarily local branches of multinational corporations with their own codes of conduct, to support the regulations. LAN, the Chilean airline headed by future president Sebastián Piñera, spearheaded business support for the legislation. This may have reflected Piñera’s electoral ambitions, but several additional CEOs spoke out that the law would improve competitiveness through the elimination of “false” subcontracting and align with their own codes of conduct (La Nación 2006e).

Conservative politicians also divided on the law. As under Lagos, many right-

wing legislators opposed the proposal. But others emphasized that they could no longer be seen as opposing subcontracted workers. The center-right Alianza supported the law to build popular support from contract workers. Government officials and news analysts speculated that Piñera’s about-face on the measure stemmed from his electoral ambitions and desire to win the votes of contract workers (Radio Cooperativa 2006). The head of the Labor Commission, Juan Pablo Letelier, bluntly explained that the right signed on to the provisions because “it was a political calculus to share the signal to stop labor abuse” (La Nación 2006d). Even senators from the right-wing UDI emphasized the embarrassment that the state’s own copper company relied on subcontracting, and stressed that the law was necessary to “stop an abuse committed by the state with thousands of workers and end precarious work” (La Nación 2006d). The law passed with strong legislative support and votes from all parties in October 2006.

There is some evidence that the subcontracting regulations improved labor practices. The percentage of businesses that hired subcontracted workers showed a modest decline, from 41 percent in 2006 to 30 percent in 2008 (Dirección del Trabajo 2008). Codelco reduced the use of contract employment from 60 to 41 percent during the same period (Codelco 2009). Just three months after the law took effect, the Labor Directorate inspected almost two thousand companies and fined 15 percent of them for illegal subcontracting practices. But domestic business groups then joined Codelco to challenge the power of labor inspectors to sanction subcontracting and won in the Supreme Court. The legal challenge made it harder to enforce subcontracting regulations, although the Labor Directorate insisted on its continuing power to inspect firms and enforce subcontracting definitions (Echeverría 2009, ch. 6).

In sum, the Chilean reform underscores the convergence in interests of unionized and contract workers. As the number of contract workers grew, organized labor saw its own ranks threatened and began to push new regulations. Politicians on the left and then on the center-right took up the cause to appeal to the growing numbers of contract workers. In Peru, by contrast, regulations passed with a far weaker partisan ally.

Contract Regulation Without Parties: Peru

As in Chile, conditions in Peru were inauspicious for broad labor mobilization and legislative change. The labor movement was decimated by state and market reforms under President Fujimori. Unlike those in Chile, Peru’s unionized workers had no coherent left-wing party allies because the country’s party system was deinstitutionalized. But the labor movement saw a need to address the growing ranks of contract workers. It timed mobilizations to coincide with presidential elections and free trade negotiations, when it could draw on the support of multinational companies and foreign pressure to buttress their labor demands. Electoral calculations led the centrist president, Alan García, to use subcontracting regulations to appeal to Peru’s growing ranks of contract workers. Contract regulations became good electoral politics, even though García largely favored business interests during his time in office and legal challenges ultimately weakened the Peruvian law.

Historically, the Peruvian labor code was one of the most restrictive and cumbersome in Latin America. In 1970, the government introduced temporary work contracts following intense business lobbying. By the late 1980s, a fifth of formal sector workers labored under temporary contracts, exempt from most benefits and firing protections, despite a requirement that the Labor Ministry needed to authorize all temporary contracts (Saavedra-Chanduví and Torero Reference Saavedra-Chanduví, Torero, James, Pagés and Washington2004).

Facing an economic crisis and high unemployment, Fujimori implemented deep labor market reforms in 1991. The labor code struck job security provisions and reduced severance payments. It also allowed employers to hire temporary workers without justification and created subcontracts in which employers at the primary firm bore no responsibility for social and labor benefits (Saavedra-Chanduví and Torero Reference Saavedra-Chanduví, Torero, James, Pagés and Washington2004, 135–37; Carnes Reference Carnes2014, ch. 5; Cook Reference Cook2007, 121). Just five years after the reforms, temporary and subcontracted workers constituted 44 percent of the formal salaried workforce (Saavedra-Chanduví and Torero Reference Saavedra-Chanduví, Torero, James, Pagés and Washington2004, 141).

Labor leaders largely prioritized defending their own rights during the neoliberal reforms. The main labor confederation, the General Confederation of Peruvian Workers (Confederación General de Trabajadores del Perú, CGTP), attempted to organize two strikes to protest the labor law reforms and cuts to workers’ benefits. Both failed to attract base support. One survey in the 1990s found that unionized workers had distinct interests from those in more precarious positions. While unionized workers were concerned with benefit levels, contract workers valued employment levels and supported more flexible arrangements (Balbi Reference Balbi, Maxwell, Mauceri and McClintock1997, 147–50).

When Fujimori left power, legislators restored some of the regulations on hiring and dismissals, but new contractual forms remained in place. Businesses relied heavily on temporary workers and subcontractors, especially in the mining industry. Only a fifth of mining workers were salaried employees of a mine; the other fraction (roughly 85,000 workers) worked for subcontractors despite doing similar jobs (CGTP 2008). Unlike Chile, mines are privately owned and operated in Peru. But the Peruvian public sector also relied heavily on contract workers. In 1991, the government “bought out” public sector workers and reduced its payroll by 300,000 workers. A year later, the government hired back almost the same number of workers as contractors with no social benefits, organizing rights, or job stability (Lora Reference Lora2007, 16).

As the number of contract workers ballooned, union leaders realized that they needed to join forces with contract workers. CGTP leaders emphasized that they could not define their interests in narrow terms if they wanted to have enough bargaining power to drive through their members’ demands. In 2008, the CGTP’s strategic priorities included reform to irregular contracts to expand eligibility to join unions (CGTP 2008). Secretary Luis Castillo of the National Federation of Mining Workers (Federación Nacional de Trabajadores Mineros, Metalúrgicos y Siderúrgico, FNTMMSP) explained in an interview to the press,

Workers have become aware that if we don’t unite, we will not have meaningful rights, nor be able to negotiate aspects that contribute to improving the quality of life… subcontracting has proliferated, without any control, which has made employment and the conditions of life more precarious for all mining workers. (El Comercio 2008a)

In 2006, the Federation of Mining Workers mobilized unionized and subcontracted workers in a large general strike. It called for new regulations on subcontracting and greater profit sharing between workers and mining companies. The strike came at a time when commodity prices were on the rise and labor shortages existed in many mines, allaying concerns about the employment effects of expanding benefits to contract workers.

As in Chile, leaders timed the strike to coincide with presidential elections. On the campaign trail, Alan García promised to complete stalled labor law reforms and limit subcontracting. García ran as the leader of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana, APRA), a political party that historically had mobilized organized labor. Yet APRA had lost substantial strength as a party and had distanced itself from its historical labor allies. García governed from the center-right once he returned to the presidential palace (Cameron Reference Cameron, Levitsky and Roberts2011). Pledges to restrict subcontracting curried favor with unions, but they mainly aimed to appeal to the growing ranks of contract workers. One APRA legislator explained the perceived importance of the expanded labor constituency.

Defending unions won few votes because they were such a minority, and it looked like you were trying to harm the majority of workers in the informal sector. But once subcontracted workers also were mobilizing with unions, you could find a way to promise better labor conditions to lots of voters. (González Posada Reference Posada2011)

When García took office, organized workers continued to pressure him to implement his promises to regulate contract work. A general strike in 2007 mobilized an estimated 110,000 mining workers, with roughly a third of the participants employed by subcontractors (IndustriAll 2007). Workers timed their activities to coincide with negotiations over a bilateral free trade agreement with the United States. The agreement brought to the fore many of the quasi-legal labor arrangements that Peruvian businesses use to slash wage bills (Cook Reference Cook2007, 126). The US State Department Human Rights Report (2007) noted three objectionable practices: businesses hire workers under short-term contracts to do permanent jobs, create shell companies to avoid direct labor relationships with their corresponding fiscal and collective rights requirements, and contract informal businesses that evade tax and benefit payments without taking responsibility for contractors’ violations. The United States thus pressed for the passage of legislation to regulate the use of atypical contracts.

Under international pressure, the Peruvian government first agreed to close legal loopholes around subcontracting in negotiations with US legislators. The government agreed to guarantee collective bargaining and organizing rights to subcontracted workers, require labor inspectors to review the use and renewal of temporary contracts, force companies to incorporate workers if they violated the definition of subcontracting, and mandate that subcontractors maintain a plurality of clients to avoid operating as a front for a single company (US House Committee on Ways and Means 2007). The Peruvian Congress then drafted a subcontracting law to implement its commitments in 2008. Mining workers threatened to strike if the bill on subcontracting did not advance.

Congress vacillated on the law, due to domestic business and conservative political opposition. The Chamber of Commerce, for instance, complained that the regulations put the onus on business to patrol subcontractors, and claimed that the law would reduce employment, grow the informal sector, and exacerbate inequality (El Comercio 2008b, d). The president of Peru’s largest business association (Confiep), Jaime Cáeceres Sayán, accused García of pandering to unions that “are not in favor of employment generation” (Perú 21 2008b).

However, the labor movement built a broad coalition of supporters to propel the proposal into law. The CGTP built alliances with several multinational firms that came out in favor of clearer regulations to define and restrict subcontracting. Minister of Energy and Mining Juan Valdivia stressed that the law would benefit companies that used legitimate subcontracting: “There are companies that comply with the spirit of subcontracting and others that don’t. Those that [use the contracts] to escape their obligations to workers should be punished” (IndustriAll 2007). Aware of the business community’s concerns, García’s finance minister said that the law struck a careful balance not to involve “too many protections to let regulations undermine employment prospects” because APRA does not “want Peruvians to be worse off or lose the little that they have” (Perú 21 2006a; El Comercio 2008c). The specter of a failed trade negotiation also counteracted business pressure.

The labor movement broadened the law’s political appeal by stressing its equalizing effects. García’s labor minister emphasized that extending worker protections to contract workers would move Peru toward better-quality employment and unleash a “great transformation” (Andina 2008b). APRA Congressman Javier Velásquez Quesquén underscored that the law would offer contract workers fair pay for their work: “It still can happen that a worker earns 2,500 soles (US$825) and has the right to profit sharing, while another worker who does the same job earns 400 soles (US$130) and has no right” (Perú 21 2008b). Legislators from across the political aisle signed on to the regulations.

It is easy to dismiss subcontracting regulations as a symbolic victory, given that Peru lacks a strong labor inspectorate to put them into force. Weak enforcement can lower the stakes surrounding formal institutional outcomes and thereby reduce the potential losses (Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Steven and María2020; Carnes Reference Carnes2014; Karcher Reference Karcher2014). Perhaps business groups conceded to the reforms knowing that informal labor practices would remain unchanged, even as the formal law shifted. Yet the sharp conflict over the law suggests that the regulations were perceived as more than window-dressing measures. Labor mobilization and pending trade talks heightened public scrutiny of the law. Business again gained the upper hand in Peru once subcontracting fell out of the public and international eye. For instance, Confiep filed a constitutional challenge to the law on the grounds that it violated guarantees of free enterprise. The Lima Chamber of Commerce also presented 12 reforms to limit the application of the law (El Comercio 2008d).

In short, Peru was a least likely case for labor coalitions to form between unionized and contract workers: the labor movement was weak and lacked stable partisan allies. Yet the dwindling numbers of organized workers led unions to link their fate to the mobilization and incorporation of a broader array of contract workers. Once subcontracted workers mobilized alongside unionized workers, García saw regulations as an electorally attractive way to appeal to those outside the traditional workforce. Reforms have proved more fragile in Peru, due to its lower enforcement capacity, making contract work a continued subject of debate and mobilization.

Conclusions

This article has shed light on unexpected alliances that can form between unionized workers and those hired on precarious contracts. It challenges a common assumption that Latin American labor markets have a dual structure and that unionized and precarious workers rarely share interests or engage in joint organizing. Interviews with union leaders in Chile and Peru reveal that organized workers increasingly saw their own labor power under threat from contract workers. Unions therefore have tried to mobilize contract workers and expand their defense of workers’ rights.

Contract workers can be quite different in terms of their potential for collective action than individuals who are self-employed or employed in small firms, such as the street vendors and trash collectors studied in this special issue. Contract workers often share labor conditions and histories with unionized workers, as demonstrated in the case of mining workers in Chile and Peru. This has made it easier for unions to defend contract workers and organize joint protests, particularly in the mining sector. Challenges to collective action may be much larger for contractors in fragmented work environments, such as the ride-sharing industry or domestic work.

The second contribution of this article is explanatory and involves tracing the process of implementing reforms to restrict the use of irregular labor contracts. When confronting alliances between unionized and contract workers, politicians have been more likely to advance regulation in the hope of appearing sympathetic to a broadly defined working class. Labor unions strategically timed their strike activities to correspond with presidential elections in Chile and Peru. There is some evidence that they also leveraged the support of multinational firms to implement contract regulations. Such broad alliances help to explain how contract reforms passed even in Peru, where organized labor is weak and lacks party linkages. Labor mobilization alone was insufficient to achieve reform, as shown by workers’ failure to achieve contract reform in Chile under Lagos and the continuous pressure needed to pass legislation in Peru under García.

Several important areas remain for future research. The first is to measure contract workers’ preferences for labor regulation directly. On the one hand, some studies show that even informal workers support high labor standards in Latin America, despite a consensus among economists that such regulations can reduce job creation and contribute to high levels of informality (Berens and Kemmerling Reference Berens and Kemmerling2019). The mobilization of contract workers for greater rights and benefits is consistent with this general preference to improve work conditions. On the other hand, while union leaders and politicians assumed that contract workers supported greater welfare benefits and collective bargaining rights, this could be tested empirically. Contract workers may weigh the benefits of higher labor standards against the possible risks of more difficult reentry into the workforce. Given the current empirical difficulties of classifying contract workers and documenting their labor histories in surveys, no studies compare the preferences of different classes of workers.

Furthermore, although this article has focused on the specific cases of Chile and Peru, future research may explore how contract workers have been incorporated into politics and mobilized in a broader range of Latin American countries. A quick survey suggests that contract work has become a topic of electoral competition and increased regulation across the region. In Ecuador, Rafael Correa decried subcontracting on the campaign trail and imposed a complete ban when he took office in 2006. In Uruguay, the Broad Front played a key role in the passage of strict subcontracting restrictions in 2007. Yet the region also has not uniformly extended rights to contract workers. Despite leftist credentials, Hugo Chávez came under criticism for the promotion of subcontractors, cooperatives, and workers’ councils to undercut Venezuela’s previously strong union movement. Many reforms implemented at moments of high commodity prices also have come under threat as economies have contracted. Quantitative tests of the broader determinants of contract reform would help complement the case histories traced here, as would qualitative work on countries with stronger unions, such as Argentina.

Studies of joint mobilization may reverse some of the prevailing pessimism about organized labor in Latin America. Unions often are caricatured as primarily acting to defend the labor benefits of their members. Yet many union leaders now hold an enlightened conception of their self-interest: contract workers, and regulations on their use, are critical to a vibrant, organized labor movement. Contract workers have been willing to join with protected workers to expand their own labor rights, security, and benefits.

Of course, my emphasis on prospects for joint mobilization should not be interpreted as naïve optimism. Obstacles to organizing workers in geographically dispersed places, which now may rely on internet platforms to access work, remain substantial. Also, the joint organizing documented here occurred around legislative changes that carried few costs to unions. Unions wanted the extension of collective bargaining rights and labor benefits to contract workers but did not volunteer sacrifices of their own. In this sense, this article coincides with work on social policy reform, which emphasizes that labor market insiders have been willing to support noncontributory social programs for outsiders as long as they do not infringe on their own benefits (Garay Reference Garay2016; Holland and Schneider 2017). Whether these coalitions can endure on more zero-sum distributive issues remains to be seen.