1. Introduction

Nyamwezi is a relatively well-documented Bantu language of Tanzania. However, apart from the work of Masele (Reference Masele2001), the dialectology of Nyamwezi has been largely neglected in the academic literature. One of the purposes of this paper is to begin to remedy the lack of information regarding Nyamwezi dialectology and in so doing clarify the exact nature of Nyamwezi's internal and external relationships. As we will see in this study, the previous lack of research into Nyamwezi's dialectological relationships has led directly to several mistaken assumptions. These mistaken assumptions concern which lects should be considered internal to Nyamwezi, as well as the nature of Nyamwezi's relationship to Sukuma.

The Nyamwezi live primarily in the Tabora region of western Tanzania between Lake Rukwa and Lake Victoria. Nyamwezi [ISO 639-3 code: nym] is spoken by nearly one million people, according to recent estimates (Lewis, Reference Lewis2009). Nyamwezi, classified as F.22 in the New Updated Guthrie list (Maho, Reference Maho2009), has been given a fair amount of attention in the literature, most notably due to Maganga & Schadeberg's (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992) work Kinyamwezi: Grammar, texts, vocabulary and has been used as a prototypical example of asymmetric vowel height harmony (Hyman, Reference Hyman1999: 237, Reference Hyman2003: 47; Stewart, Reference Stewart2000: 46). Nyamwezi is also considered to be extremely conservative (displaying a lack of fairly common Bantu phonological innovations such as 7V>5V mergerFootnote 1 and loss of phonemic vowel length), and, as representative of Eastern Bantu languages as a whole, is thought to bear a strong resemblance to Proto-Bantu both lexically and morphologically (Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:29; Schadeberg, Reference Schadeberg2003:143). Sukuma (F.21), a neighboring Bantu language to the north of Nyamwezi, is spoken by over five million people (Lewis, Reference Lewis2009) and is also well-documented (e.g. Batibo, Reference Batibo1985).

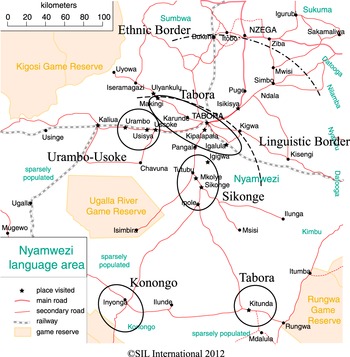

The conventional wisdom regarding Nyamwezi and Sukuma suggests that “no strict linguistic border” separates the two language varieties and that they exist in a dialect continuum with one another (Maganga & Schadeberg, Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992:11; Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:10). I claim instead that a rough linguistic border exists just north of Tabora (see Map 3 in §5) which separates the Nyamwezi varieties from Sukuma. As a result, Sukuma and Nyamwezi do not exist in a dialect continuum with one another, and the Ndala lect described in Maganga & Schadeberg (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992) should be considered Sukuma and not Nyamwezi. In support of these claims, I show that the Makingi and Igalula lects near Tabora are transitional dialects that have filtered lexical items and phonological innovations from Sukuma.

Map 3 The Nyamwezi language area: Major dialects and borders.

The gap in information regarding Nyamwezi dialectology has also had a negative impact on attempts to reconstruct the linguistic history of the region. By clarifying Nyamwezi's internal and external relationships, we can also begin to re-examine the linguistic history of the region. A reasonably strong consensus exists among historical Bantuists that Nyamwezi has a close genetic affiliation with other F.20 languages including Sukuma and Kimbu (F.24) (Ehret, 2009; Nurse, Reference Nurse1999; Nurse & Philippson, Reference Nurse and Hinnebusch2003). Nyamwezi may also share a close genetic affiliation with Nilamba (F.31) and Nyaturu (F.32). Nurse includes Sukuma, Nyamwezi, Kimbu, Nilamba, and Nyaturu in his West Tanzania (WT) grouping (Reference Nurse1988:34, 90; Reference Nurse1999:10). The relative lack of phonological innovation within WT as a whole makes it more difficult to be confident in the phylogenetic relationships of its members. However, this study uses four main early phonological innovations (*c/*j fricativization, Bantu spirantization, Dahl's Law, *p-lenition) to begin to untangle Nyamwezi's historical relationship with SukumaFootnote 2 .

The principles of a time-based, or Baileyean dialectology (Bailey, Reference Bailey1996), are used in this paper to explore the spread of linguistic innovation through space and time. Pelkey (Reference Pelkey2011:31ff.) uses an integrative approach to dialectology, which incorporates insights from Baileyean dialectology, to examine the Phula languages within the Tibeto-Burman language family. This paper uses a similar approach, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, including a distance-based network analysis, implicational hierarchy, and dynamic wave analysis.

§1.1 presents a description of the relevant fieldwork, data points, and existing Nyamwezi dialect information. §1.2 includes a description of the relevant phonological features chosen for this study. §1.3 constitutes a brief review of Masele (Reference Masele2001). §1.4 outlines the structure of the remainder of this paper.

1.1. Methodology and background on Nyamwezi dialects

The main source of data for this paper comes from survey research conducted by SIL personnelFootnote 3 in Tabora and Rukwa/Katavi regions in October 2011 and March 2012. Additional data come from previous survey research in the Mpanda District of Rukwa/Katavi Region (Inyonga) in August 2010 (see Roth, Reference Roth2011). Nyamwezi data from Ndala (the Nzega District of Tabora Region) are taken from Maganga & Schadeberg (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992).

The data corpus consists of wordlists taken in twelve different village/town locations: Igalula, Igigwa, Ilunde, Inyonga, Ipole, Isikisya, Kitunda, Makingi, Mkolye, Urambo, Usoke, and Utende (see Map 1 below). The 2011–12 wordlists were not based on either of the Swadesh wordlists, and do not consist of primarily core vocabulary. In §2, I use these wordlists to carry out a distance-based network analysis.

Map 1 The Nyamwezi language area and research locations.

The village/town locations of Ilunde, Inyonga, and Utende are considered Konongo, although Ilunde is more mixed and much more like Nyamwezi. The 2012 wordlists taken in the Konongo locations were relatively shorter (approximately 100 lexical items) compared to the wordlists from the Nyamwezi locations (around 150 lexical items). Data from the August 2010 survey (approx. 600 lexical items) in Inyonga supplement the Konongo data where needed. In both locations, the majority of the 2012 wordlist consisted of verb forms (85–90%). The 2012 Konongo wordlist was a subset of the Nyamwezi wordlist, with minor additions/variations. Because of the differences between the Konongo and Nyamwezi wordlists, Konongo is not included in the distance-based network (§2) or Appendix B. Although Konongo is not incorporated into the corpus the same way as the Nyamwezi varieties, the lexical similarity among primarily core vocabulary between Konongo (Inyonga) and the Ndala lect was found to be 74% in Roth (Reference Roth2011:123)Footnote 4 .

As much as possible, care was taken during the dialect surveys to get a representative sample from each research location. Table 1 provides the relevant metadata from the Nyamwezi and Konongo dialect surveys.

Table 1. Metadata summary from Nyamwezi and Konongo surveys

The criteria for a representative sample included at least four speakers, a fairly even male/female split, an age range of 25–60, the speakers being from the research location area and speaking that variety, the speakers having not lived in another location for more than a year, and both their parents speaking (or having spoken) that variety. For the most part these qualifications were held. It was not always possible to get an even male/female split, all speakers under age 60, or both parents having spoken that variety. Most speakers were bilingual in Swahili.

This paper identifies at least three main dialects within Nyamwezi: Tabora, Sikonge, and Urambo-Usoke. Konongo could be considered a dialect of Nyamwezi or possibly a language in its own right (see §6 for further research ideas). Maho (Reference Maho2009:44)Footnote 5 identifies eleven dialects of NyamweziFootnote 6 : Galaganza, Mweri, Konongo, Nyanyembe, Takama, Nangwila, Ilwana, Uyui, Rambo, Ndaala, and Nyambiu. Masele (Reference Masele2001) includes Nyanyembe, Takama, Galaganza, and Konongo within his corpus as dialects of Nyamwezi. Both Maho (Reference Maho2009:44) and Masele (Reference Masele2001) separate Takama and Galaganza (in contrast with the description in Abrahams [Reference Abrahams1967]). The Takama lect is located just north of Tabora, while the Galaganza lect is located to the west and southwest of the Tabora Region (Masele, Reference Masele2001:5). Map 2 outlines the rough dialect area locations from Masele (Reference Masele2001:5) and the main data point from Maganga & Schadeberg (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992).

Map 2 Previous research on the Nyamwezi language area.

A one-to-one correspondence between these supposed clan names within Nyamwezi and modern-day town/village names or dialect clusters is not possible. However, much like the situations in other Bantu languages, the language as a whole needs to be thought of as a collection of much older clans that often correspond to modern-day dialects.

1.2. The features chosen and brief explanation

The following features were chosen for inclusion in the implicational hierarchy in §3: *c/*j fricativization, *p-lenition, Dahl's Law, and agentive and causative spirantization.

*C/*j fricativization is a process in which *c became s and *j became z. This is thought by Batibo (Reference Batibo2000:23–4) to have taken place at a time when WT was still intact; thus, a very early process. All of the members of WT have this innovation. *P-lenition is a process in which *p became h. Nurse claims that it is the “earliest lenition affecting the voiceless stops” and that “in East Africa it is useful because it…divides northern and southern languages” (1999:22). It has affected most Bantu languages (Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:22). Dahl's Law is a dissimilation process involving the voicing of an otherwise voiceless plosive if the consonant in the following syllable is voiceless. Dahl's Law can occur morpheme-internally (e.g. *put-a > -but-a ‘to cut’) or across morpheme boundaries (e.g. k℧-tool-a > g℧-tool-a ‘to marry’) in some Sukuma/Nyamwezi lects (see Batibo Reference Batibo2000 and discussion in §4). Dahl's Law is present within “a fairly tight group of languages in the northeast of the Bantu-speaking area” (Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:20).

Bantu spirantization is a lenition process in which stops are replaced by fricatives before the Proto-Bantu high vowels *į and *ų. This process can occur in several morphological contexts: morpheme-internally and across morpheme boundaries before the adjective, causative, agentive and perfect suffixes. Bantu spirantization in Sukuma and Nyamwezi is said to be phonologically restricted, that is, only certain stops are replaced by fricatives, e.g. in Sukuma, *p, *t, *k, *d morpheme-internally and *d before the agentive (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000; Bostoen, Reference Bostoen2008:322).

The dialect research in the present study was designed in part to capture a snapshot of these early period innovations. They were chosen for several reasons. Nurse says the following regarding early period innovations, which include *p-lenition, Dahl's Law, and Bantu spirantization:

These features—few in number—are shared by whole sets of groups. I would not claim that these features never cross language boundaries but rather that they are more likely to be inherited in our languages from an early stage of common development and thus historically diagnostic for the early period (1999: 20, italics mine).

Not only are these innovations historically diagnostic, these early period innovations are also particularly interesting for Sukuma/Nyamwezi for two other reasons: (1) because the Sukuma/Nyamwezi language area is near the geographic north-south border for *p-lenition and Dahl's Law (Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:20–22; Nurse & Philippson, Reference Nurse and Hinnebusch2003:175), and (2) because of their inconsistent, or incomplete application. Examples of the inconsistent/incomplete application of these early period innovations are included in Table 2.

Table 2. Inconsistent application of early period innovations in Nyamwezi

This issue of the inconsistent/incomplete application of early period innovations within Sukuma/Nyamwezi is addressed in Batibo (Reference Batibo2000). Possible explanations include issues of activity/inactivity, bleeding effects, and influx of vocabulary from outside sources. I discuss these issues further in §4.

1.3. Review of Masele (Reference Masele2001)

Masele's (Reference Masele2001) dissertation deals in depth with the linguistic history of many of the WT languages and takes into account Nyamwezi dialectology. Masele includes a total of ten lects: four from Nyamwezi, three from Sukuma, and three from Sumbwa (2001:14). However, many of the participants in Masele's study may have been living outside of their language area for some time. He says that an unknown number were University of Dar es Salaam professors and students, and government employees, and that many of the participants were trilingual in Swahili, English, and their local language (2001:19). It is important not to underestimate the influence of Swahili in Tanzania, especially in and around Dar es Salaam, not to mention the continued use of Sukuma in different places around the country. If Masele did not travel and find participants in the actual language areas, it may very well have affected the accuracy of the data, specifically whether his data are representative of the dialect areas in question (see the discussion of Konongo and Dahl's Law below).

One of the main areas of agreement between Masele's (Reference Masele2001) conclusions and my own (within the more limited scope of the present paper) is the similarity of the Takama lect to Sukuma and not Nyamwezi, both lexically and phonologically (Masele, Reference Masele2001: 401). Masele's Dakama lect corresponds to the towns/villages in the area just north of Tabora (see Map 2), represented in the present paper by the data points Isikisya and Ndala. I argue in this paper that Isikisya and the Ndala lect described in Maganga & Schadeberg (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992) both should be considered Sukuma on a lexical and phonological basis. Phonologically speaking, this conclusion is based on the extent of voiceless nasals and Dahl's Law in which our data generally agree. Masele reports that only Sukuma and the Takama lect have voiceless nasals (2001:55). In the limited survey data for this study, the Isikisya lect and the Tabora dialect attest voiceless nasals, while the Sikonge and Urambo-Usoke dialects do not. In regard to the extent of Dahl's LawFootnote 7 , Masele says that “in our preliminary data, most of F22 shows doubtful Dahl's Law or none at all, except in loans. However, Maganga & Schadeberg (Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992:23) suggest that Dahl's Law in F22 (KɪNyamweezi) is almost exceptionless” (Masele, Reference Masele2001:53).

The main areas of disagreement concern the reliability of Masele's Konongo data and his historical treatment of Bantu spirantization processes. Masele analyzes the inconsistency of Bantu spirantization in Sukuma and Nyamwezi as due to a combination of lexical borrowing and palatalization processes (2001:135). Masele mistakenly assumes that Bantu spirantization “does not allow” or “is unlikely to accommodate such exceptions” (2001:135). In fact, lexical doublets and other examples of exceptions due to inconsistent application of Bantu spirantization occur quite frequently for a variety of historical reasons (see Bostoen, Reference Bostoen2008). Although lexical borrowing certainly had a part to play historically, the reasons for the inconsistent application of Bantu spirantization in Sukuma and Nyamwezi are much more complex (see Batibo, Reference Batibo2000, for a full treatment).

The differences between my Konongo data and Masele's (Reference Masele2001) data are substantial in regard to Dahl's Law. My Konongo data do not show even remnants of Dahl's Law with only one exceptionFootnote 8 . A less substantial difference is Masele's analysis of Konongo as definitively having a 7V system. My Konongo data are inconclusive in regard to the vowel system as 7V or 5V. A regular pattern found in the 2010 Konongo data from Inyonga is a vowel split between Speaker 1 and Speaker 2 in the context of a Nyamwezi [−ATR] high vowel. Speaker 1 uses high [+ATR] vowels in these contexts, while Speaker 2 uses the [−ATR] counterparts, similar to Nyamwezi. A sample of this phenomenon is included in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Konongo vowel variation

In the 2012 survey, the older Konongo speakers (60+) sampled in Inyonga maintain the phonological contrast between [i, ɪ] on the one hand and [u, ℧] on the other in the applicative [-il, -ɪl] and inversive [-ul, -℧l]. The younger generation of Konongo speakers seems to have lost that contrast. A possible hypothesis for these phenomena is the current negotiation of a 7V>5V merger. However, more phonological research needs to be done, specifically to see whether younger speakers (age~20–35) still maintain phonological contrast between /i, ɪ/ and /u, ℧/ in roots or not.

1.4. Structure

The present section has provided an introduction and background to the Nyamwezi dialect situation, the methodology of the present study, the relevant phonological features used, and a brief examination of previous research. §2 uses a distance-based network analysis to provide a working hypothesis for the analysis that follows in the remaining sections. In §3, I use an implicational hierarchy and dynamic wave analysis to trace innovations in Nyamwezi through space and time. §4 provides a relative chronology of the four main early innovations within Sukuma/Nyamwezi (*c/*j fricativization, Bantu spirantization, Dahl's Law, and *p-lenition). In §5, I provide a synthesis of the major conclusions from the previous sections. §6 concludes by providing a brief summary and possible avenues for further research.

2. Distance-based network analysis

A distance-based network analysis is a quantitative analysis used as “an introductory visual means of data exploration” (Pelkey, Reference Pelkey2011:279). The Neighbor-Netalgorithm, as developed by Bryant & Moulton (Reference Bryant and Moulton2004) is applied to a distance matrix, or a standard lexicostatistical matrix with the figures converted into their opposite values. For example, the Isikisya and Ndala lects below are 0.63735 similar and 0.36265 dissimilar (see the lexicostatistical matrix for the majority of the corpus languages in Appendix B). Splits Tree 4 (4.11.3) is the software program used in this paper to implement the algorithm and display the results (Huson & Bryant, Reference Huson and Bryant2010).

Bantu languages, and East African Bantu languages in particular, are characterized by the dual historical processes of divergence and convergence. Standard tree models are only able to represent divergence. “Unlike trees, which only permit branching and divergence among taxa, networks can also have reticulations among branches, making it possible to show more than one evolutionary pathway on a single graph” (Holden & Gray, Reference Holden and Gray2006:24). The diagram, or splits-graph, does appear more tree-like if the distance-based relationships are unambiguous. However, if the relationships are ambiguous, the splits are weighted with the relative weight (or confidence in the split) indicated by the length of the branch. Refer to Holden & Gray (Reference Holden and Gray2006) for more on the Neighbor-Netalgorithm as applied to other Bantu languages. Figure 1 below illustrates the competing relationships of the Nyamwezi dialects (the Konongo lects of Ilunde, Inyonga, and Utende are not included).

Figure 1 Distance-based network of 10 Nyamwezi varieties.

Based on the distance-based network in Figure 1, the evidence points towards at least three main dialects within Nyamwezi: a Tabora dialect consisting of Igalula, Kitunda, and Makingi, a Sikonge dialect consisting of Igigwa, Ipole, and Mkolye, and an Urambo-Usoke dialect. From the distance-based network, Isikisya appears to also belong to the Tabora dialect along with Makingi, but is shown in §3 to be a part of Sukuma along with the Ndala lect on the basis of shared phonological innovations.

3. Implicational hierarchy and dynamic wave analysis

In this section, I use certain concepts within Baileyean dialectology (see Bailey, Reference Bailey1996), namely an implicational hierarchy and an accompanying dynamic wave model, to examine the validity of the dialectal relationships proposed in §2 and refine them.

The difficulty with examining isogloss patterns is that “isoglosses typically fail to bundle in topological or social space and scattered transitional dialects are the norm” (Mühlhäusler, Reference Mühlhäusler1996:11). An implicational hierarchy rearranges those isoglosses so that each lect is distinguished by only one feature. A plus sign represents the presence of a particular feature, while the minus sign represents its absence. The resulting distribution is implicational in the sense that if a lect at the far right of the diagram has a particular feature, those to its left necessarily have that feature as well.

The goal is to see how innovations have spread across dialects in space and time. At a minimum, the most innovative dialects can be separated from the more conservative ones. However, as mentioned in §1, Nyamwezi has a reputation for being extremely conservative. Also, innovations such as *p-lenition, Dahl's Law, and spirantization have applied inconsistently across Sukuma and Nyamwezi (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000; Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:10). The implicational hierarchy can aid in seeing how these innovations have spread across dialects. This implicational pattern can also be represented in a dynamic wave model, another way of illustrating this spread of innovations. These methods yield both quantitative and qualitative measures, and the conclusions are predictive, testable, and falsifiable.

Table 4 below presents the implicational hierarchy for the Nyamwezi lects along with the Utende variety of Konongo. The wordlist data supporting each of the features in Table 4 are included in Appendix A. Isikisya and Ndala (data from Maganga & Schadeberg, Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992) are so similar in terms of shared innovations that they have been combined. For the lexical isogloss ‘hunter’, a minus symbol (−) was given to those lects with the reflexes of *-bɪnd,Footnote 9 while a (+) was given to those lects with the reflexes of either *-guɪm or *-pɪig. The majority of the spirantization features are included in the separated bottom portion of the table as an indication that the spread/diffusion of these features occurred differently (see below). Please note the different ordering of the lects in the bottom portion as a result.

Table 4. Implicational hierarchy for Nyamwezi lects

Notation key: (+) = presence of the feature, (−) = absence of the feature, (?) = lack of evidence or inconsistent data, (x) = the use of a different lexical item in that lect, (*) = feature out of place on the hierarchy, (−/+) = attestation of both the presence and absence of the feature, often lexical doublets.

From the top portion of Table 4, Isikisya and Ndala are shown to be the most innovative lects in the corpus, while Konongo is the most conservative. One could interpret the implicational pattern in Table 4 as evidence for a dialect continuum from Isikisya and Ndala in the north all the way to Konongo in the south. It is important to realize, however, that the implicational hierarchy represents the spread of linguistic innovation over the space and time dimensions, and does not make any inherent judgments regarding language/dialect, dialect chains, transitional dialects, subgrouping, etc. As Bailey, quoted in Mühlhäusler, says: “We must distinguish the relative constancy of the linguistic pattern (i.e. in the grammar) from the many ways in which the variants can be distributed at different times and different places” (1996:11).

The ordering of lects within the implicational hierarchy in Table 4 confirms the conclusion from the distance-based network in §2 that there are at least three main dialects within Nyamwezi: A Tabora dialect consisting of Igalula, Kitunda, and Makingi, a Sikonge dialect consisting of Igigwa, Ipole, and Mkolye, and an Urambo-Usoke dialect. The same groupings can be derived from the lower portion of Table 4 dealing with the distribution of Bantu spirantization features (see discussion below). The inclusion of Kitunda with the Tabora dialect, although the lect is spoken much further south (see Map 1), can be explained by the fact that speakers from this area claim they originally came from Tabora (time depth unknown). The linguistic evidence supports this claim, and also explains their use of mu-βend-i ‘hunter’, a reflex of *bɪnd, and not a reflex of either *guɪm or *pɪig.

Figure 2 below uses the data from the top portion of the implicational hierarchy to show the wave-like spread of innovation over each of the lects.

Figure 2 Dynamic wave model of Nyamwezi dialects.

The Isikisya and Ndala lects should be considered Sukuma linguistically, while the Sikonge lects are distinctly Nyamwezi. Makingi and Igalula should be considered transitional dialects, or mediators between the more historically innovative Sukuma lects and the more historically conservative Nyamwezi lects (see §5). The most representative example is the fact that each of the Tabora dialects has remnants of Dahl's Law, while the Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge dialects have no traces.

As previously mentioned, the agentive and causative spirantization features follow a different pattern, and are included in the separated bottom portion of Table 4 as a result. The key innovations which do not fit into the top portion include *d causative spirantization and the lexicalized, spirantized mlozi ‘witch’. The implication for the Bantu spirantization innovations is that their origin was in the Nyamwezi lects (Konongo, Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge) and not Sukuma. What might this process have looked like?

Bantu spirantization in both Sukuma and Nyamwezi is considered phonologically restricted. Whereas in other languages with Bantu spirantization all or most stops are replaced by fricatives in the proper phonological/morphological environment, in Sukuma and Nyamwezi only certain stops are replaced by fricatives, e.g. in Sukuma, *p, *t, *k, *d morpheme-internally and *d before the agentive (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000; Bostoen, Reference Bostoen2008:322). This corresponds with the restrictions to causative and agentive Bantu spirantization in the bottom portion of Table 4 as well. Furthermore, there is evidence from Bantu spirantization typology which proposes that “[Bantu spirantization] originally affected all plosives across the board, but only became morphologized in the case of the most commonly spirantized plosives” (Bostoen, Reference Bostoen2008:341). There also seems to be a progression of Bantu spirantization in which coronals (*t/*d) are affected first, then velars (*k/*g) and labials (*p/*b). Bostoen (Reference Bostoen2008) goes on to say that if this is true, “then it seems plausible that at a certain stage, the majority of spirantized agent nouns were derived from verb roots with a final coronal consonant” (341).

Bostoen says that “as regards the diachronic evolution of Agent Noun Spirantization (ANS), ‘phonologically restricted ANS’ seems to represent an initial stage in the morphological conditioning of the sound change” (2008:340). Both Sukuma and Nyamwezi are 7V languages, and the retention of a 7V system also hinders the morphologization of Bantu spirantization (Bostoen, Reference Bostoen2008:343). For Sukuma and Nyamwezi this means that agentive nouns with *d (*d > l) such as mtoozi ‘groom’ (-toola ‘to marry’) and msuzi ‘blacksmith’ (-sula ‘to forge’) are fossilized evidence of the possible beginnings of morphologization and subsequent lexicalization of these forms before the language had a chance to level them away. For Konongo and most of Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge, this process was able to take place for at least one agentive noun with *g, mlogi>mlozi. It is possible that such ANS could have been diffused from nearby language groups to the south or west (Bende-Tongwe, Rungwa or Ha).

Table 5 summarizes the relevant changes for each dialect area from the implicational hierarchy data in Table 4.

Table 5. Summary of innovations for each dialect area

The aim of this section was to see how the early period innovations spread across dialects in space and time. We saw from the implicational hierarchy (and dynamic wave model) how innovations spread across dialects in the space dimension. Within the current data corpus, the Isikisya and Ndala area seems to be the focal area for many of the early period innovations (except Bantu spirantization). Those innovations spread to the Tabora dialect area, and then later to Urambo-Usoke and to some extent Sikonge. The implicational hierarchy also makes a claim regarding the relative ordering of innovations across the time dimension. From the top portion of Table 4, this indicates *c/*j fricativization occurred first, then *p-lenition and subsequently Dahl's Law.

In §4, I set out to refine the relative chronology for the early period innovations in Sukuma and Nyamwezi. The purpose is to use the insights from this research on Nyamwezi dialectology to begin to untangle Nyamwezi's historical relationship with Sukuma and the rest of WT.

4. Towards a refined relative chronology

We saw in §1.2 and §3 that most of the early period innovations within Sukuma and Nyamwezi have inconsistent/incomplete application, including *p-lenition, Dahl's Law and Bantu spirantization. Batibo (Reference Batibo2000) offers solid evidence that the inconsistent application of these phonological innovations is due to the timing of their activity/inactivity, bleeding effects, and the incorporation of lexical items from other sources. In regard to Bantu spirantization in particular, we saw from Bostoen's (2008) Agent Noun Spirantization typology that the processes of morphologization, lexicalization, and analogical levelling were also at work.

In §3, we saw that the implicational hierarchy makes an implicit claim regarding the relative ordering of innovations across the time dimension. In the case of Sukuma/Nyamwezi, *c/*j fricativization occurred first, then *p-lenition, and subsequently Dahl's Law. Batibo (Reference Batibo2000) also proposes a limited relative chronology, which is summarized in Figure 3. There is essentially no substantial difference between my proposal and Batibo's (2000) proposal in regard to the relative ordering of *c/*j fricativization, *p-lenition and Dahl's Law.

Figure 3 Summary of Batibo's (2000) relative chronology.

To summarize Batibo's (2000) proposal, the Sukuma and Nyamwezi were still an intact group after their split from West Tanzania and stayed that way until around 1100-1300ad. The WT split occurred around 500ad: the Nilamba/Nyaturu went to the northeast, the Kimbu to the southeast, and the Sukuma/Nyamwezi to the northwest (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000:24). The fricativization of *c/*j took place before the WT split, and Dahl's Law, *p-lenition, and spirantization all were activated before the split of Sukuma and Nyamwezi. The fact that Nilamba/Nyaturu and Kimbu do not have Dahl's Law supports this conclusion (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000:24). Dahl's Law must have taken place after the WT split but before spirantization, while *p-lenition could have occurred anytime after the WT split but before the Sukuma-Nyamwezi split (Batibo, Reference Batibo2000:24–5).

However, §3 of this paper has presented phonological evidence contrary to Batibo (Reference Batibo2000) and to some extent Masele (Reference Masele2001). Based on the data from the implicational hierarchy in Table 4, many of the Nyamwezi dialects do not share the same innovations as Sukuma. For instance, the only sign the Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge dialects show of Dahl's Law is *kupɪ > ŋguhɪ. The process was perhaps “undone in its early stages” as Nurse proposes for some of the Great Lakes (GL) languages (1999:28). It is just as likely that the later diffusion of Dahl's Law never reached the more southern Nyamwezi dialects and that the lexical item ŋguhɪ/ ŋgupɪ ‘short’ was borrowed and maintained at a later point. Along with the fact that Nyaturu, Nilamba, and Kimbu show limited (or no?) signs of Dahl's Law (Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:10), this is fairly good indication that the innovation did not spread any further southward.

Batibo claims that Dahl's Law is/was active across morpheme boundaries in Nyamwezi, giving the example k℧-tool-a > g℧-tool-a (2000:26). This type of Dahl's Law across morpheme boundaries was not found in any of the corpus lects. Combined with the fact that these dialects have inconsistencies with the northern Nyamwezi dialects/Sukuma in regard to *p-lenition and Bantu spirantization as well, it means at very least the Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge dialects did not travel the same path as northern Nyamwezi/Sukuma for as long.

The activation of Bantu spirantization is assumed by Batibo to have followed Dahl's Law (and perhaps *p-lenition?) because of possible bleeding effects. At least one of Batibo's examples of the interaction of Dahl's Law and Bantu spirantization was found to be inconclusive. He argues that *-puta > -buta ‘to cut’ prevented the form -futa from occurring (2000:24). However, the Urambo-Usoke and Sikonge dialects retain -puta (see Appendix A). Data for analyzing morpheme-internal spirantization were not collected for the corpus data (see §6 for ideas for further research). If the bleeding effects are inconsistent, it is possible that the activation of Bantu spirantization took place prior to or simultaneous with Dahl's Law and *p-lenition (see discussion in Nurse, Reference Nurse1999:21–2).

Essentially, Batibo holds to a divergence model for the linguistic history of Sukuma and Nyamwezi. Batibo assumes a coherent Proto-WT which included Nilamba/Nyaturu, Kimbu, and Sukuma/Nyamwezi. He also assumes a Proto-Sukuma/Nyamwezi and assigns approximate dates to various splits. We could represent this fairly easily with a Stammbaum diagram. At the risk of oversimplification, Batibo's (2000) divergence proposal is a valid hypothesis. Of course, there is much more complexity, as we have seen, but if we further posited an older dialect chain and the transitional dialects around Tabora, this would make sense of much of the data. However, it does not explain the palatalization of the *d causative in Isikisya and Ndala (e.g. ku-guja ‘to sell’ with /j/ as a voiced palatal stop; see Note 1 to Appendix A) rather than the spirantization which occurs in the *d causative in the Nyamwezi lects (e.g. ku-gu z ya ‘to sell’). These are completely different outputs and are difficult to explain in a divergence scenario like the one described above.

There is another equally valid hypothesis which also explains the data and owes more to convergence (see Masele, Reference Masele2001). Under this scenario, we do not have to assume the unity of a WT (although this approach is not incompatible with a unified WT). Instead, we assume that either Sukuma or Nyamwezi was already in situ, while the other came from somewhere else, and came into close contact with the in situ variety. This scenario seems to make the most sense if Sukuma were the in situ variety, and Nyamwezi came from elsewhere and came into close contact with Sukuma. The supporting evidence for such a scenario would be the spread of *p-lenition and Dahl's Law which for the most part only reached Sukuma and the Tabora transitional dialects, as well as the differences in Bantu spirantization (*d causative, *g agentive) between Sukuma/Tabora and the rest of Nyamwezi. This scenario would also be compatible with a situation in which Sukuma experienced the diffusion of Dahl's Law and *p-lenition from nearby Great Lakes/Interlacustrine languages to the north and/or west.

5. Synthesis

Thus far, I have demonstrated through the combination of a distance-based network analysis, implicational hierarchy and dynamic wave analysis that Nyamwezi should be considered to have at least three main dialects: Tabora, Sikonge, and Urambo-Usoke. I have also shown that the Isikisya and Ndala lects should be considered Sukuma on the basis of lexical and phonological evidence. By implication, this evidence also points toward a rough linguistic border between Nyamwezi and Sukuma just north of Tabora. Lexically, the Isikisya lect could very well be grouped with Makingi according to the distance-based network analysis. However, the Isikisya lect is also not lexically incompatible with Ndala (see Figure 1). Moreover, the phonological overlap between the Isikisya and Ndala lects is coupled with several key phonological differences with the majority of their southern neighbors: Dahl's Law, voiceless nasals, and lack of *d causative spirantization. The presence of such a linguistic border just to the north of Tabora is in direct contradiction to Maganga and Schadeberg's evaluation that “there seems to be no strict linguistic border which would separate it [Kinyamwezi] from its northern neighbor Kisukuma” (1992:11).

Consequently, the linguistic border just north of Tabora does not match up with the perceived ethnic border around Nzega. The result is a “no-man's land” between Tabora and Nzega where people identify themselves as Nyamwezi but actually speak Sukuma (see Map 3 below).

In Map 3 the borders for each of the dialects, as well as the linguistic and ethnic borders for Nyamwezi and Sukuma, are intended to be approximate.

Instead of positing a dialect continuum the length of the entire Nyamwezi and Sukuma language areas, though, I argue that the Makingi and Igalula lects around Tabora should be considered transitional dialects. Within such transitional dialects, features of a more innovative language variety and a more conservative language variety are negotiated. Language change, however, moves in only one direction, from the more innovative variety to the more conservative. In the case of Nyamwezi/Sukuma, language change filtered from the Sukuma lects influenced the Tabora dialects, e.g. *p-lenition and Dahl's Law. This transitional-dialect analysis explains both why “speakers…refer to any more northern variety…as Kisukuma”, and the fact “they also recognize that ‘Nyamwezi’ and ‘Sukuma’ are two distinct ethnic identities, each with its own language” (Maganga & Schadeberg, Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992:11).

Theoretically, the transitional-dialect analysis does not preclude an internal dialect continuum within either Nyamwezi or Sukuma. It is still likely that Sukuma exists internally as a dialect continuum, stretching from just north of Tabora to the north of Mwanza. Nevertheless, a full dialect survey of Sukuma would need to be done to confirm that hypothesis. For Nyamwezi, this is much less likely. However, if one considers Konongo a dialect of Nyamwezi, it may be possible to consider Konongo and Sikonge the beginning of a dialect chain northward.

In addition, I also made a claim regarding the relative ordering of innovations: First *c/*j fricativization, and then *p-lenition followed by Dahl's Law. There is essentially no substantial difference between my proposal and Batibo's (Reference Batibo2000) proposal in regard to the relative ordering of these three innovations. No firm claim was made, however, in regard to the timing of Bantu spirantization. Contrary to Batibo (Reference Batibo2000), though, my data/analysis is not incompatible with Bantu spirantization operating concurrently with *p-lenition and/or Dahl's Law. Furthermore, a convergence scenario in which Sukuma was already in situ, with Nyamwezi arriving at a later point and coming into close contact with Sukuma was found to correspond more closely with the historical linguistic evidence.

6. Conclusion and further research

This paper set out to remedy the lack of information regarding the dialectology of Nyamwezi, a well-known East African Bantu language. At least three main dialects were identified within Nyamwezi: (1) a wider Tabora dialect including the Igalula, Makingi, and Kitunda lects, (2) a Sikonge dialect consisting of the Mkolye, Ipole, and Igigwa lects, and (3) a dialect consisting of Urambo and Usoke. These three main dialects were identified using both quantitative and qualitative methods: A distance-based network analysis, an implicational hierarchy, and dynamic wave analysis. Konongo could also be considered a dialect of Nyamwezi, but the situation remains unclear. In addition, the Isikisya and Ndala lects were identified as Sukuma, and a rough linguistic border was identified just north of Tabora. The Tabora lects were found to be transitional dialects, mediating innovation from Sukuma to Nyamwezi. Nyamwezi and Sukuma are not dialects of one another, and do not exist in a dialect continuum with one another as has been traditionally assumed. This transitional-dialect analysis better incorporates the new Nyamwezi survey data.

This was not dialectology for the sake of dialectology, however. The additional aim of this paper was to apply a Baileyean dialectology to the early period innovations in Sukuma and Nyamwezi to conceptualize the spread of linguistic innovation. The situation with Nyamwezi and Sukuma was seen to be extremely complex with phonological innovation characterized by activity/inactivity, bleeding effects, lexical borrowing, morphologization, lexicalization, and analogical levelling. The hope is that having used the Nyamwezi-Sukuma situation as a sort of paradigmatic test case in the region, related research can be done in other nearby Bantu languages. If so, we can begin to refine our conception of Proto-Bantu and the early movements of the Bantu peoples from the bottom-up. However, there is much more to do even within Nyamwezi and Sukuma.

As mentioned at the outset in §1, this study was based on data from a rapid dialect survey of the Nyamwezi area, focusing only on segmental phonological features and lexicostatistics from relatively short wordlists. Areas for further research should firstly include a comparative study on the lexical and grammatical tone patterns in Nyamwezi and Sukuma. Much work has already been done on tone in Sukuma (e.g. Batibo, Reference Batibo1985; Maganga & Schadeberg, Reference Maganga and Schadeberg1992). Now that the main dialect areas have been identified one could do research more strategically in fewer locations. Another area for further research would be a comparative study on tense/aspect morphology in these same varieties.

Yet another idea for further research is a full dialect survey of Sukuma. Not only would this provide information regarding the “‘focal’ and ‘relic’ areas” (Hock, Reference Hock1991) of Sukuma, but the results would be a crucial piece of the puzzle for reconstructing the historical scenario of WT and the relative chronology of Bantu spirantization in relation to *p-lenition and Dahl's Law. Further research into the dialects of Nyamwezi could include the examination of morpheme-internal spirantization, agent noun spirantization, and core vocabulary from the Swadesh lists. More of the data from Batibo (Reference Batibo2000) could also be checked for any inconsistencies in each of the major dialect areas of Nyamwezi now that they have been identified.

Another area for research would be a proper phonological analysis of the vowel system in Konongo. Intelligibility testing could also be done between Konongo and other Nyamwezi varieties. Further research is also needed to compare Konongo with Kimbu lects to the south as this would aid in uncovering the exact nature of Konongo's historical relationship within a hypothetical WT.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Cara Ediger, Susi Krüger, Danielle MacDonald, Bernadette Mitterhofer, Netta Shepherd, Richard Yalonde, and all of the Nyamwezi/Konongo participants for all their hard work and participation in the Nyamwezi and/or Konongo survey(s). I would also like to thank Bernadette Mitterhofer and Oliver Stegen for their comments and suggestions on the initial drafts of this paper. Special thanks to Colin Davis for his work on the Nyamwezi maps. I appreciate all of your help, insights, and contribution to this work. Any errors are my own.

Appendix A: Wordlist Data1 Support for Implicational Hierarchy

Konongo and the Sikonge Dialect

The Urambo-Usoke Dialect

Appendix B

Nyamwezi/Sukuma Corpus Data Lexicostatistics