IntroductionFootnote 2

The title of this contribution echoes two excellent articles written by Juan Cole (1986) and Meir Litvak (2001) on the role of ‘Indian money’ in shaping the institutional contours of Twelver Shīʿīsm in late Ottoman Iraq.Footnote 3 Those studies were respectively interested in the religious controversies stoked by Indian remittances to Najaf and Karbala from the mid-eighteenth century, and the Oudh Bequest, a massive endowment founded in 1850 by the Twelver Shīʿī rulers of the Princely State of Awadh. Overseen by British officials in India and Iraq, the bequest doled out funds to Shīʿī clerics in Iraq's shrine cities and was a central prop in the regional political economy until the end of colonial rule. But whereas Cole and Litvak focused on tensions among Indian Twelver Shīʿīs, the mujtahids, and British colonial officials, here the concern is with the various Bohra and Khoja Shīʿī pilgrimage institutions connecting western India and the ʿAtabāt-i ʿAlīyāt (the “sublime thresholds”) in the late Ottoman and British Mandate/early Hashemite periods. These institutions facilitated the pilgrimage, relocation and burial of Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Shīʿīs from western India to the matrix of sacred sites in Najaf, Karbala, Kazimain, Kufa, and Samarra associated with the first six Shīʿī imāms.

The western Indian Shīʿī communities studied here include two Ismāʿīlī communities —the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī Khojas (better known as the followers of the Aghā Khāns) and the Ṭayyībī Mustaʿlī Ismāʿīlī Bohras (popularly called the Dāwūdī Bohras). In addition, the influential constituency of Twelver Shīʿī Khojas, some of whom were formerly Nizāri Ismāʿīlīs, are central protagonists here.Footnote 4 Among the Khojas, priority is given in this article to the Twelver Khojas because of their more concerted interest in establishing pilgrimage institutions in the shrine cities. As for the Ismāʿīlī Khojas, although pilgrimage to the shrine cities was demoted on occasion by the Aghā Khān III, the community continued to visit Iraq, and the expansion of Ismāʿīlī foundations in Iraq after 1918 strengthened their presence. They are studied here partially as a foil to the Bohra and Twelver Khojas, but also because the religious and economic history of all three groups was so intertwined. Following a survey of Bohra and Khoja economic and religious activity in Iraq and the wider Indian Ocean from 1850–1918, this article first examines, through Gujarati and Urdu sources, the operation of the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī (founded in Karachi in 1897). It then turns to Twelver Khoja institutions such as the musāfirkhānas (hostels) founded in Iraq by community merchants, and the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjatanī (established in Bombay in 1912). A final section concludes with an analysis of a lengthy anti-Bohra and Khoja polemic written in Persian by a Twelver Shīʿī mujtahid and published in Najaf in 1932, the same year Britain's Mandate in Iraq ended.

As argued here, the construction of Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage infrastructures between India and Iraq supplied a new paradigm of trans-national, caste-centric Shīʿī pilgrimage in each group. Mass pilgrimage was itself made possible by the mobilisation of community wealth and the integration of community institutions into colonial administrative and transport networks. Bohra and Khoja success in crafting this infrastructure increased their presence as never before in the sacred terrain revered by all Shīʿa. It represented an iteration of what has been called “locative piety”, whereby “new spaces of sacerdotal and soteriological significance” were transposed from the homeland to foreign territories.Footnote 5 Here the meaning of locative piety refers more specifically to the Bohra and Khoja effort to embed India-based pilgrimage institutions within the religious economy of southern Iraq. For centuries, Bohras and Khojas had visited sacred sites in India, Yemen, Egypt, Arabia and Iran. But in line with other so-called “New Muslims” — a contemporary Urdu term reserved for the Bohras, Khojas, and Memons — their sacred geography was centred on places singular to their history and dedicated to their own religious dignitaries, with several locations in Gujarat of special prominence. The shrines to the first six imams in the ʿAtabāt-i ʿAlīyāt were arguably a marginal node in the wider constellation of Bohra and Khoja religious life until around 1900, when overseas pilgrimage to Iraq and the Haramayn grew in importance. This gave both groups an increasingly public, albeit controversial, profile in the leading pilgrimage sites of the Islamic world. While generating novel itineraries of Bohra and Khoja devotional life, the institutional demands of locative piety guaranteed that each group's prominence in the urban fabric of Karachi, Bombay and other ports of the Indian Ocean was replicated in Iraq.

The Bohras’ and Khojas’ pivot to Iraq at the turn-of-the-century was dependent upon three interconnected processes dating to the mid-nineteenth century: the emergence of differentiated western Indian Shīʿī communities as a consequence of both strengthened religious hierarchies and the proliferation of sectarian polemics, associations and kinship networks in the Indian Ocean; the elevation of the proprietors of Shīʿī commercial firms into trans-imperial economic players and functionaries of colonial civic orders from Zanzibar to Hong Kong; and, in an echo of developments charted by John Slight for Hajj,Footnote 6 the ability of Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage entities to integrate themselves into the transport and administrative systems linking British India and Ottoman/Mandate Iraq. This latter development assumed several forms, including membership on the influential Port Haj Committees of Bombay and Karachi.Footnote 7

With the colonial nexus playing a significant role as it did in the studies by Cole and Litvak, this period thus marked another moment in which ‘Indian money’ transformed the religious landscape of Iraq's Shīʿī shrine cities. Nevertheless, several factors distinguished this phase from that studied by Cole and Litvak. The most obvious difference was that from 1918–32 Iraq was a British Mandate, which intensified colonial management of Iraq's pilgrimage traffic and eased Bohra and Khoja attempts to construct a pilgrimage infrastructure. Even so, the singular constitution of the Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure was of equal relevance in differentiating this age of ‘Indian money’ from its earlier iteration. For one, the institutional underpinnings of Bohra and Khoja money differed from the inland Twelver Shīʿī religious endowments in India that remitted funds to Iraq, the khūms levy that Twelver Shīʿī faithful allocated to choice scholars, and the substantial private donations of Arab, Iranian and Indian Twelver merchants. The circulation of this money undoubtedly reshaped the infrastructure of the shrine cities, but did not translate into a well-supervised, material apparatus that oversaw the pilgrim's journey from India to Iraq. By contrast, the Bohra and Khoja trusts headquartered in Bombay and Karachi were able to translate economic power into a trans-imperial pilgrimage infrastructure made up of both religious and mercantile entities. Besides pious endowments, the portfolios of these institutions included the assets of commercial firms, individual jamāʿat (congregations), civil associations, musāfirkhānas and madrasas. Print capitalism further enabled the functioning of the system, as a new breed of Gujarati pilgrimage manuals published by Bohra and Khoja authors helped pilgrims navigate these itineraries.

As several contemporary observers attest, with all this infrastructural density at the pilgrim's disposal, the experience of a Bohra or Khoja travelling to Iraq from Amreli or Benares was demonstrably unlike that of non-Khoja Twelver Shīʿī journeying to Iraq from Lucknow or Hyderabad. The latter were at the mercies of local accommodation, provisions and transport throughout their journey. While there was a heightened concern among Shīʿī communities in Iran and India about the exigencies of travel to Iraq, and charitable entities were created to mitigate the costs of pilgrimage, Twelver Shīʿa did not enjoy the assistance of robust community organisations available to Bohras and Khojas.Footnote 8 One Twelver Shīʿī notable travelling from Hyderabad to Iraq in the 1920s echoed many a contemporary Indian observer when two weeks into his pilgrimage he wrote “Up until now, only the administration [intiz̤ām] of the Khoja and Bohra jamāʿat merit excessive praise, and, in this specific instance, are worthy of emulation [qābil-i taqlīd]”.Footnote 9 British officials took the prospect of emulation one step further. One admirer was John Gordon Lorrimer, who managed the Oudh Bequest and Indian pilgrimage traffic in the years before the First World War. In one instance, Lorrimer marvelled at the Bohras’ work in the shrine cities and acknowledged that “the Oudh Bequest committees might well follow in the [Bohras’] steps by providing suitable hostels for ordinary Shi'ahs [sic] at the principal places, and by furnishing guides to interpret for them, make their travelling arrangements, and protect from the thousand and one rapacious harpies to whom they at present fall an easy prey”.Footnote 10

Although Iranian and Indian Twelver Shīʿī pilgrims utilised the infrastructures generated by various state entities and merchant investment in the region, Bohras and Khojas alone enjoyed the added benefit of a relatively streamlined pilgrimage, with community wealth acting as institutional underwriter from India to Iraq. Nonetheless, there were also salient differences between the Bohra and the Khoja pilgrimage circuits, as kinship and caste solidarities distinguished each community from the other, and from other Shīʿa in the shrine cities. Caste identity was by no means all-encompassing, but it did function as a primary boundary mechanism, often in surprising ways. In addition, whereas the Bohra network was run by a centralised committee overseen by the dāʿī al-muṭlaq, Khoja pilgrimage infrastructures were divided between rival Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Khoja factions. For the growing constituency of Twelver Khojas in particular, increased pilgrimage to Iraq's shrine cities became a means to deepen their links with Twelver mujtahids and reorient their sacred geography away from the Ismāʿīlī imām, whose authority many of them had only recently renounced. In that sense, locative piety was held up as an alternative to the embodied piety centred on the figure of the Aghā Khān: With that said, Twelver Khoja enthusiasm for visiting the shrine cities was no guarantee that their caste affiliation was diluted in a wider Twelver melting pot. Just the opposite was the case: Twelver Khojas regularly invoked caste to keep non-Khoja Twelvers from using their pilgrimage institutions in both India and Iraq. But when compared to the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī, evidence suggests that Twelver Khoja institutions, though presenting several advantages to community pilgrims, ultimately lacked the Faiż-i Ḥussainī's organisational depth.

Yet equally compelling for present purposes is that, as with the Oudh Bequest studied by Cole and Litvak, the expansion of Bohra and Khoja institutions in Iraq was a source of conflict with the local Twelver Shīʿī religious hierarchy. Unlike the money sent annually from the long-deposed rulers of Awadh—which nonetheless caused considerable resentment among the Twelver Shīʿī learned hierarchy despite the avowedly imāmī credentials of Awadh's royal family—the burgeoning Bohra and Khoja presence in Iraq's shrine cities was regarded by some local mujtahids as a threat to Shīʿī Islam. To these clerics, the Bohras and Khojas were heretical sects “who adorn themselves in the garments of the Shīʿa” and whose presence in the shrine cities was only growing “at a time when the armies of Satan have invaded the abode of faith”. Those words were written in 1932 by Muḥammad Karīm Khurāsānī, a prominent Twelver Shīʿī scholar in the holy city of Najaf. His biting 364-page polemic against the Nizārī and Ṭayyībī Mustaʿlī Ismāʿīlīs, titled Kitāb Tanbīhāt al-Jalīyah fī Kashf Asrār al-Bāṭinīyya fī Tārīkh al-Aghākhānīyya wa-l-Buhra (The Book of Manifest Recriminations in Revealing the Secrets of the Esoteric Sects in the History of the Aghā Khānīs and Bohras) speaks to the swirl of competition and recrimination among various Shīʿī groups seeking in their own irreconcilable ways to speak authoritatively for Shīʿī Islam.Footnote 11

Displaying a deep familiarity with medieval Ismāʿīlī history and the chronicles of the leading Mamluk-era Sunni historians of the Fatimids, Khurāsānī also evaluated the Bohras and Khojas through the prism of Muslim intellectual movements that had emerged in the Middle East and South Asia from the mid-nineteenth century. These included earlier offshoots of Twelver Shīʿīsm such as Bābīsm and Bahāʾīsm, but also the Ahmadiyya and the Sudanese Mahdi. As shown below, when read against the backdrop of fierce Gujarati polemics exchanged between Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Khojas in this period, Khurāsānī's diatribe was perhaps the most fulsome statement of the temporally episodic and geographically disparate conflicts between Ismāʿīlī and Twelver Shīʿīs in the Indian Ocean from the 1860s onwards. At the same time, the polemic suggested that the Shīʿī mujtahids were uninformed of the precise fissures prevailing among western Indian Shīʿa, and sometimes failed to distinguish their own Twelver congregants among the Khojas. Even so, Khurāsānī cast his eye far and wide, even to Bombay and Khorasan, where he also detected an Ismāʿīlī assault on Twelver Shīʿīsm. Above all else, Khurāsānī's treatise verified that the advent of Bohra and Khoja infrastructures in the shrine cities had altered the public complexion of Shīʿī Islam in southern Iraq, aggravating perceptions among the mujtahids that their monopoly over the contours of Shīʿī Islam was at risk.

Ismāʿīlī and Twelver Shīʿī Commerce and Religious Activism in the Indian Ocean, 1850–1914

While several scholars have examined how Shīʿī Muslims in Iraq, Lebanon and India created sectarian institutions in the interwar period to strengthen elective ties and obtain organisational autonomy from Sunni Muslims, far less attention has been reserved for internal stresses and strains within modern Shīʿī Islam.Footnote 12 This applies especially to the rich literature on ‘the other Shīʿīs’, that is non-Twelver communities.Footnote 13 An outstanding special issue in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society—which later became an edited volume—was, with the exception of one piece, less concerned with Ismāʿīlī-Twelver Shīʿī interactions than with the equally worthy task of reconstructing the diverse strands within Indian Shīʿīsm and their international articulations.Footnote 14 Likewise, while recent years have seen first-rate studies on the elaboration of a trans-imperial infrastructure for Hajj from the mid-nineteenth century, little attention has been paid to Shīʿī infrastructures as such, or the pilgrimage to the shrine cities.Footnote 15 What is more, while exceptional studies of Karbala as an object of memory for South Asian Twelver Shīʿa have appeared, there remains little sense of the physical mechanisms of pilgrimage from India to Iraq.Footnote 16

Finally, most studies of the Bohras and Khojas tend to treat them in isolation, and rely largely on either contemporary ethnographic observation or colonial/English-language records.Footnote 17 Scholarship has benefited enormously from these contributions, but unfortunately historians have overlooked the many unstudied Gujarati texts published throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by Bohra and Khoja authors.Footnote 18 These represent a hitherto largely untapped resource for the study of Islam in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Rather than quaint expressions of an ‘Indic’ Islam-set-apart, these works had significant consequences for the character of trans-regional Shīʿī Islam in the early twentieth century—as did the foundation of Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage infrastructurse in Iraq. These texts reveal that Bohras and Khojas (Twelver and Ismāʿīlī alike) engaged with a range of Islamic texts—some written by those from outside their community—and supply an unrivalled perspective into how pilgrimage to Iraq became a leitmotif for the articulation of a cohesive, if particularistic, vision of Shīʿī Islam in each group. As a rubric for studying processes by which religious institutions founded in India were exported to Iraq, locative piety supplies a way of reimagining Bohra and Khoja Islam beyond the rigid paradigms of Indic/Arab Islam or that of self-contained communities standing outside of broader currents of global Islam.Footnote 19

That new paradigm also requires reimagining prevailing narratives about Islam and capitalism. To a degree that far outweighed their comparatively small numbers, the multi-form Shīʿī communities who hailed from the patchwork territories that now make up Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, and who comprised a many-centuries admixture of foreign emigres and local converts, were conspicuous international economic and religious players in the period under review. Their outsized presence was aided in no small measure by the fact that they boasted a disproportionate number of the colonial era's leading Muslim commercial firms. With some exceptions, in contrast to the Shīʿa of the United Provinces, Bihar and Bengal, the Bohras and Khojas of western India became leading merchant actors in the Indian Ocean from the mid-nineteenth century. To be sure, there was a sizable contingent of non-Khoja Twelver Shīʿī merchants in the environs of Calcutta, and Twelver Shīʿī institutions like the Hughli imāmbāṛah boasted Shīʿī merchants as trustees and acted as a creditor in the local economy, but was, like the Oudh Bequest, supervised by the colonial state.Footnote 20

But despite these examples, the outsized predominance of three mercantile communities from western India—the Sunni Memons and the Shīʿī Khojas and Bohras—in modern company formation has been acknowledged since the 1970s, with several arguments of varying quality put forward for this.Footnote 21 Instead of finding answers in primordial traits or ‘Hindu’ inheritance practices as is sometimes assumed,Footnote 22 the best explanation for this divergence is found in institutional differences among Muslim populations. The Bohras, Khojas, and Memons all exemplified a common formula in which they were able to enmesh themselves in the colonial civic order, leverage their aberrant status in the colonial legal system to obtain particular privileges, and fuse their homegrown caste institutions with modern banks and firms. The homegrown caste institution common to all three groups was the jamāʿat, which functioned as the principal, though by no means exclusive, economic and religious pivot of community life.

What is clear is that Bohra and Khoja merchant capital—as vested in the jamāʿat—had the effect of intensifying intra-Shīʿī sectarian identities through a dual process of horizontal differentiation and vertical integration. While many excellent studies on Indian Ocean commerce in recent years have emphasised the trans-religious, often ‘cosmopolitan’ moral economies undergirding business enterprise,Footnote 23 that same literature has tended to miss the many instances in which commerce functioned as a motor accelerating intra-group sectarian conflict. The Bohra and Khoja experience offers one such example in which merchants assumed a central role in not only producing and exacerbating religious conflict, but also in strengthening the position of community religious elites, least of all the latter's oversight over geographically dispersed congregations in the Indian Ocean. This was distinct from the parallel process in which a Twelver Shīʿī sectarian identity was elaborated in colonial north India. There, as Justin Jones has shown, sustained conflicts among Twelver Shīʿī figures—including over the management of economic resources as vested in pious endowments—significantly molded the public character of Twelver Shīʿīsm, and intensified the sectarian encounter with strains of Sunni Islam in the subcontinent.Footnote 24 But given their constituent members’ presence as merchant actors from Zanzibar to Japan, Bohra and Khoja struggles were played out on a wider geographic canvas. At stake were several antagonistic notions of religious authority, with newly assertive Ismāʿīlī religious leaders in particular presenting a more integrated model of community hierarchy than that associated with Twelver Shīʿīsm, at least when bereft of explicit political patronage.

As Jonah Blank has remarked, whereas Twelver Shīʿīs have a multitude of competing mujtahids from whom to choose, Ismāʿīlīs “take their guidance from a single apex cleric”.Footnote 25 The Ismāʿīlī Bohra and Khoja religious leadership oversaw a plethora of jamāʿat scattered across the Indian Ocean, each possessing their own accountants, treasurers and committees that transmitted funds annually to Bombay and Karachi, and which ensured proper adherence to religious practice, settled disputes and acted as capital pools in their own right.Footnote 26 (Twelver Khojas and Sunnis from both the Khoja and Memon communities also benefited from the jamāʿat to manage commercial and religious affairs, but they lacked a single ‘apex’ cleric that fused these entities together.Footnote 27) For both Ismāʿīlī Bohras and Khojas, this had distinct institutional consequences, arguably in terms of both religious and commercial organisation. With that said, the installation of a single apex cleric among both the Ismāʿīlī Bohras and Khojas was never an organic process, but one rife with conflict. And even the institution of the jamāʿat—with its rigid emphasis on obeying community norms and proclivity to fracture into sectarian groupings — was no guarantee of economic success.

The paradox was that sectarian tensions among the Shīʿa of western India occurred in groups that had deep links with non-Muslim capital, who participated actively in a multitude of international pan-Islamic charitable campaigns (including nominally ‘Sunni’ ones), and who were prominent in All-India Muslim causes. Nonetheless, this preoccupation with internal boundaries over and above external opponents is in keeping with what scholars of religious polemics have recognised in recent years, especially those who work on nineteenth and twentieth-century South Asia.Footnote 28 Surprisingly, little evidence appears of Bohra and Khoja conflict with each other, and if contemporary Twelver Khoja accounts are any indication, Khojas did possess at least a passing literacy in the Bohras’ religious doctrines and history, but rarely, if ever, presented these in the form of a heresiology.Footnote 29 Ismāʿīlī and Twelver Khoja authors alike were far keener to refute the heresies propounded by their own constituents than to engage in polemics with other Muslim communities.Footnote 30 Unsurprisingly then, almsgiving and philanthropy became prominent sources of friction among Khoja constituencies. What was at stake was not mere considerations of mammon, but rather what should serve as the magnet of community devotion as expressed in monetary donations. As shown below, to many newly-minted Twelver Khoja merchants, building a musāfirkhāna in Bombay, Karachi, Zanzibar or Iraq was a means to express, in brick and mortar, their new Twelver Shīʿī dispensation. It was a gesture of locative piety.

For all the similarities, religious conflicts played out quite differently among the various Bohra and Khoja communities. Arguably, this had implications for the varied position the shrine cities of Iraq held in the pilgrimage itineraries of Ismāʿīlī Khojas, on the one hand, and Bohras and Twelver Khojas, on the other. In contrast to the Khojas, with their fracturing among various Sunni and Shīʿī constituencies, the Dāwūdī Bohras remained a far more integrated community under the authority of a single religious head in the form of the dāʿī al-muṭlaq (cleric of absolute authority), the earthly vicars of the imāms who Bohras believed had entered into the state of occultation from the twelfth century.Footnote 31 Based on the current state of historical knowledge concerning the Bohras, one can say tentatively that, unlike the Aghā Khān, the Bohra religious leadership was able to allay any serious threats to its leadership—with the exception of periodic disputes over the 1840 succession and the 1897 schism of the Mehdī BaghwālāsFootnote 32—until the ascent of a reformist group in the interwar period, which still never threatened the dāʿī al-muṭlaq's control over religious matters.Footnote 33 The cardinal objection of that group was the dāʿī al-muṭlaq's arrogation of community assets to his own person, very far from the Twelver Khoja opposition to the Aghā Khān's claim to be visible imām.

Like their Nizārī Ismāʿīlī counterparts, the succession of Bohra dāʿī al-muṭlaqs received regular donations from the faithful throughout the Indian Ocean, and substantially benefitted from the meteoric rise of Bohra commercial firms throughout the region. This link between commercial capital and religious leadership was something that piqued the interest of late nineteenth-century Indian Sunni Muslim historians, even if they discovered that little else could be known about the Bohras’ internal history, save that gleaned from medieval Sunni historians.Footnote 34 The expansion of Bohra merchant fortunes from that period did not prompt the fragmentation of the dāʿī al-muṭlaq's authority as it did among the Khojas, but, for a time at least, strengthened links between Bohra communities in the diaspora and the dāʿī al-muṭlaq's office in Bombay. By the First World War, the dāʿī al-muṭlaq, though in no way insulated from threats to his authority by select members of the religious hierarchy and mercantile laity, stood at the apex of a vertical hierarchy that integrated the panoply of jamāʿats established by Bohras from Singapore to Galle and Basra.Footnote 35 The tenure of Ṭāhir Saif al-Dīn (r. 1915–65) would only strengthen this hold further, not least by his acquisition of direct administration over the religious institutions that facilitated pilgrimage to the shrine cities. This particular dāʿī al-muṭlaq visited Iraq on several occasions, as commemorative volumes published in his honour lavishly document.Footnote 36

For the Khojas, meanwhile, the famous Aghā Khān Case in 1866 was merely the catalyst for a series of strained, sometimes bloody, intra-caste religious confrontations that persisted into the interwar period.Footnote 37 As Nile Green has shown, the resurgence of neo-Ismāʿīlī currents stemmed in large measure from Bombay's meteoric rise as the premier industrial metropolis of the Indian Ocean.Footnote 38 The growing commercial and political power exercised by the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī religious and mercantile elite very soon expanded to east Africa and Burma, but conjured up acute discord with Twelver Shīʿī clerics and communities. Nizārī Ismāʿīlī fundraising capabilities in particular, buttressed by a fusion of specially appointed accountants, an embrace of capitalist institutions, and links with non-Muslim capital, gave them the resources to define a new brand of public Shīʿī Islam to that propounded by the Twelver Shīʿī clercial hierarchy in Iraq, Iran and north India. From the 1840s, merchants became leading actors in the drama of intra-Khoja religious rivalry.Footnote 39 The formation of charitable and religious institutions was an inseparable prop of the business empires of many Khoja Ismāʿīlī magnates in East Africa.Footnote 40 Similar acts of sectarian philanthropy were undertaken throughout all sites of the Khoja diaspora.

Deepening the ties between an embryonic Ismāʿīlī Khoja interpretive community and a newly minted, publicly visible imām entailed a deliberate ploy to minimise interactions between Ismāʿīlīs and Twelver Shīʿīs. Ismāʿīlī Khoja circulars (printed in both Gujarati and English) dispatched to the faithful in cities like Karachi, Rangoon and Poona threatened any congregant with immediate excommunication if they made contact with Twelver Shīʿī clerics.Footnote 41 In time, however, Twelver Khoja religious and commercial firms responded with initiatives of their own to integrate ‘wayward’ Shīʿī back into the fold. Regulations for the ballooning Twelver Khoja jamāʿats at the turn of the century display retaliatory attempts to restrict interactions with those outside the group. They also feature the names of prominent members of local civil society institutions and professions and detail the panoply of funds founded by Twelver Khoja businessmen for the benefit of the jamāʿat.Footnote 42 What is more, from the 1890s, an energetic group of Khoja polemicists undertook persistent efforts to turn Khojas away from the Aghā Khāns and wrote caustic attacks on Khoja Ismāʿīlī beliefs and practices. The development of a Twelver Khoja publishing culture, as embodied by newspapers like Bhavnagar's Rāhe Najāt, also fostered the emergence of this Twelver Khoja counter-public,Footnote 43 not least by cataloguing the names of those Khojas who donated funds to the poor of Karbala, and running regular pieces on the shrine cities.Footnote 44 From this point, pilgrimage to Iraq became a cornerstone of that strategy to turn the Khojas back to the ‘true path’. Unlike the Bohras then, for the Khojas pilgrimage to Iraq had the potential to augment internal division rather than integrate the community under the apex religious head.

In traversing the terrain of inter-Shīʿī institution building and sectarian differentiation, this section has demonstrated that the boom in Bohra and Khoja commercial fortunes facilitated the emergence of an infrastructure of public Ismāʿīlī and Twelver Shīʿī Islam which vied for the hearts and minds of the nominally Shīʿa populations scattered from Karachi to Bombay and further afield. A host of community and commercial institutions underpinned these novel forms of public Shīʿīsm and were—in keeping with processes of locative piety—transferrable and extendable to new spaces. With their presence stretching from Darussalam to Singapore, Bohras and Khojas were well-positioned to pivot to Iraq at the turn-of-the-century. There, late Ottoman developmental policies and trade links with the subcontinent, intensified substantially by the advent of the British Mandate, encouraged the arrival of Bohra and Khoja merchant houses, and with them, recently created pilgrimage institutions.

The Bohra and Khoja Presence in Late Ottoman and Early Hashemite Iraq

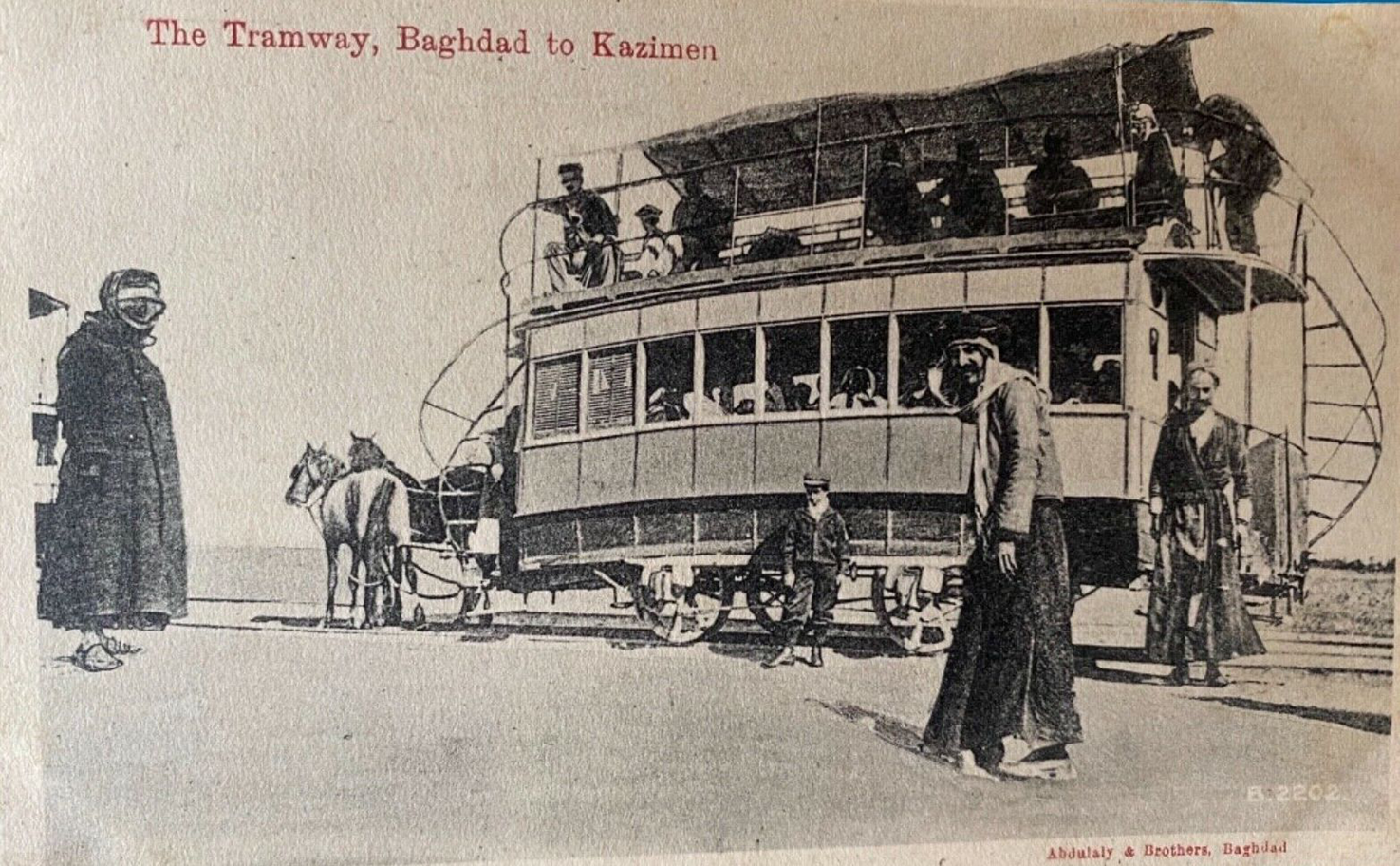

Southern Iraq became a site of Bohra and Khoja commercial operations in the final decades of Ottoman rule. Several turn-of-the-century infrastructural changes in both the Ottoman and British empires facilitated their entrance. The last decades of the century had seen a boom of private enterprise in southern Iraq and tussles among British and Ottoman authorities over trade privileges, the control of internal markets, import duties and sovereignty.Footnote 45 The foundation of an Ottoman consul-general in Karachi in 1891 (a Bombay branch had been founded in 1850) further strengthened trade and transport links between Iraq and western India.Footnote 46 Ottoman transport developments in the provinces of Baghdad and Basra from the 1890s also spurred the influx of Bohra and Khojas firms. Bohra and Khoja travelogues regularly mention the Baghdad Railway and tram networks in Najaf and Karbala, including the horse-tramway network running between Kazimain and Baghdad.Footnote 47 Without this expansion, Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage institutions would have been unable to integrate themselves into the dense infrastructural threads linking Iraq and India that only escalated after 1918.

Ottoman almanacs from this period bear witness to the litany of new railways, canals, roads, hostels, companies, and schools constructed by local authorities, as well as the high numbers of Persian and Indian pilgrims from various strands of the ‘Shīʿī madhhab’ visiting the shrine cities.Footnote 48 The influx of Shīʿī pilgrims also dovetailed with the conversion of large numbers of tribespeople from southern Iraq to Shīʿī Islam, an effort that Ottoman authorities tried unsuccessfully to forestall.Footnote 49 Even so, as a history of Najaf published by a Twelver scholar in the 1930s regularly noted, in the Hamidian era Ottoman authorities had financed the restoration of several Shīʿī sites in Iraq, richly supplementing the regular donations by private Arab, Indian, and Iranian merchants.Footnote 50

In the case of Bohras and Khojas, religious institutions followed on the heels of a new mercantile presence. Individual Bohras were already present in the shrine cities by the early nineteenth century, as Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Ḥussain Karbalāʾī Karnātakī Hindī attested in passing in his pilgrimage diary compiled between 1815 and 1817.Footnote 51 But a more emphatic Bohra presence can be found from the turn-of-the-century with the arrival of several Bohra commercial companies. A leading pre-war Bohra firm, Messrs. Abdul Ali & Co., operated two ice factories in Baghdad and one in Karbala before the onset of the war. The firm also ran a famous postcard business that produced images of the Shīʿī sacred sites in southern Iraq (see Figures 1–4). The records of the American Chamber of Commerce for Turkey in 1911 listed the firm in the same company as European and American companies, a telling indication of its prominence.Footnote 52

Fig. 1. Postcards from the shrine cities produced by the Bohra firm, Abdul Aly Bros. Reproduced with permission of The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 2. A postcard produced by the Bohra firm, Abdul Aly & Co., showing ‘goofas’ being produced outside the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. Author's personal collection.

Fig. 3. A postcard produced by the Bohra firm, Abdul Aly & Co., displaying the tramway that ran from Baghdad to Kazimayn. This transport method was used widely by Bohra and Khoja pilgrims. Author's personal collection.

Fig. 4. A postcard produced by the Bohra firm, Abdul Aly & Co., displaying the carriages that transported pilgrims to Karbala. Author's personal collection.

In fact, Abdul Ali & Co.'s ice-factory was one of the few private machine-driven industries in all of Iraq, with the remaining operations under the control of the Ottoman government in the form of an army clothing-factory and army flour mill.Footnote 53 Perhaps for this reason, beginning in 1910 the firm was on the receiving end of an effort on the part of the Ottoman government to artificially depress the price of ice.Footnote 54 According to a consular report, several Ottoman officers had entered the firm's premises and threatened to pluck out the eyes of an employee, one Faiż Muḥammad ibn Nūr Muḥammad.Footnote 55 To enforce further compliance, the Ottoman governor had threatened to close the factories after Abdul Ali & Co. refused to comply with the price decrease, insisting that the factory was a violation of the Ottoman law of 1864, something that British authorities entirely rejected. British authorities assumed that local Ottoman officials in Baghdad had an interest in creating a monopoly over all local industries, making Abdul Ali & Co. a prime target.Footnote 56 In this and other episodes, the local British consular offices served as an important conduit for the redress of Bohra and Khoja grievances with Ottoman (and later Hashemite) authorities.Footnote 57 For example, when in 1912 Ottoman authorities attempted to expand a road, partially demolishing Bohra and Khoja property, British officials intervened on the Indians’ behalf. It appears the favour was returned: the namesake of Abdul Ali & Co. later claimed to be the first to raise the Union Jack in Baghdad following the city's fall to the British in 1917.Footnote 58 As Britain's mandate in Iraq began, Bohra invocation of their status as British subjects became more frequent, with the Bohra dāʿī al-muṭlaq petitioning colonial authorities on one occasion to intervene with Iraqi authorities on behalf of Bohra pilgrims harassed in the shrines of Karbala.Footnote 59

In fact, the end of Ottoman dominion in Iraq accelerated the arrival of western Indian capitalists in the region. They joined Punjabi and Bengali military and civilian labour, and ran the gamut from pilgrimage agents to banking firms with branches stretching to Basra and Baghdad. Alongside Bohras and Khojas, Iraq's transition to British rule also brought Parsi firms and travellers to Baghdad and Basra, as Māṇekjī noted in his own 1922 Zoroastrian pilgrimage account to Iraq and Iran.Footnote 60 Arriving in southern Iraq from an extended tour of Sasanian sites in Iran, Māṇekjī stressed the construction of new road networks and the influx of motorcars, as well as the cluster of Parsi firms in Basra. Another Parsi travel-book on Iran and Iraq spoke to a Parsi readership of the “conducted tours” run out of Bombay by the Jeena Company.Footnote 61 Around the same time, the Tata consortium sought to expand its banking business in the region, though the Viceroy's office threw cold water on the idea.Footnote 62 Perhaps the Twelver mujtahid Khurāsānī (examined below) was not merely employing a standard heresiological trope about the Ismāʿīlīs when he dismissed the Bohras and Khojas as majūs (Zoroastrians). He likely saw the influx of Gujarati-speaking Parsis, Bohras and Khojas into Iraq as part of the same phenomenon, as it surely was.

While Ismāʿīlī Khojas saw much commercial promise in Iraq, the precise place accorded to the Shīʿī shrine cities in Ismāʿīlī Khoja devotional life during the imāmate of Aghā Khān III is difficult to gauge. Periodically, despite the fact that his own father was buried at the family mausoleum in Najaf,Footnote 63 the head of the Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs downplayed the importance of both pilgrimage to Iraq, such as in a farmān delivered in Mombasa in 1899 where he said “People go to Karbala, where they physically see the golden houses (shrines), stones and clay, so what? Make an inner house, which is profitable indeed”.Footnote 64 (Unlike his father and mother, the Aghā Khān III was not interned in the family mausoleum in Najaf, but rather at a monumental facility in Aswan in Egypt.) This contrasted, however, with the Aghā Khān III's pronouncements before and during the First World War that Iraq represented a natural arena for Indian commercial expansion, beaming that the region's value would amount to “five East Africas”.Footnote 65 His India in Transition, written in 1918, heralded the age when India's imperial borders would stretch “from Aden to Mesopotamia, from the two shores of the Gulf to India proper”.Footnote 66 It was perhaps for this reason that the British Foreign Office suggested the Aghā Khān as a potential leader of Iraq in the late 1910s, though his name was quickly dropped from the list of candidates.Footnote 67 All the same, some quarters of Muslim public opinion in India were scandalized by the announcement and the Aghā Khān was compelled to deny the charges publicly. In turn, some of his followers rose to his defense, with a lecture given at Bombay's Young Ismaili Vidhya Vinod Club on the subject.Footnote 68 Nevertheless, soon after Britain's conquest the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī imām repeatedly emphasised that Iraq should not become a formal colony of the British empire, and in the early 1930s in a speech given as head of the League of Nations, the Aghā Khān congratulated Iraq on its independence and entry into the League, while stressing the “intimate spiritual, cultural, and economic ties” linking the country with India.Footnote 69

Barring some pre-war merchants in Basra, the modest influx of Khoja Ismāʿīlī merchants into Iraq began in earnest with Britain's conquest of Ottoman Iraq in 1917–18. The site for the first Khoja Ismāʿīlī jamāʿat khāna was the Basra offices of M/S Pesan Allana Bros., a merchant who migrated from Karachi to Iraq after hearing the Aghā Khān encourage Ismāʿīlīs to seek out business opportunities in the country.Footnote 70 The declaration was actually disseminated as a farmān (official decree), with the Aghā Khān stating

Those murīds (followers) who are not running a business here [in Karachi], go to Mesopotamia, so as to make very good profits….Now this is nothing new, twenty or thirty years ago in Africa, Burma island, etc. no businesses of murīds were in operation. They were begging us in such a way, then we gave an order to go to Africa, Rangoon, Burma Island, etc, and in turn our murīds became millionaires (lakhpati). Similarly, if you are not running a business here [Karachi], go there [Mesopotamia], and you will make very good profits. Khānāvādān (May your house be blessed).Footnote 71

Although the Ismāʿīlī Khoja jamāʿat in Iraq did grow somewhat as a result, Iraq seems to have held a secondary importance in the pilgrimage landscape of Khoja Ismāʿīlīs in this period, even if Karbala itself maintained its pride of place in the devotional literature of Ismāʿīlī Khoja writers, and images of the Battle of Karbala were printed by Khoja commercial firms (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Late Nineteenth-Century Depiction of the Battle of Karbala. Produced by a commercial firm in western India. Author's private collection.

As for the Twelver Khojas, despite the fact that Iraq had been a key site of interaction between Twelver mujtahids and Twelver Khoja merchants from the 1870s, the latter do not appear to have set up branches of their commercial enterprises nor jamāʿat khānas until the turn of the century, with an slight upward trend following the British conquest of Iraq.Footnote 72 Jethabhāʾī Gokal, among the Twelver Khojas who set up a business in Karachi during the Khoja controversies of the 1890s, moved his operations to Basra in 1918 after the British conquest of the city. There he opened a shipping business and became the head of the Twelver Khoja community. In the 1930s the firm became the agents in Karachi, Muhammarah and Basra for both Japanese and Swedish shipping companies.Footnote 73 One of the firm's partners in the 1940s was a director for The Indian and Persian Gulf Bank, which was founded as a means to shore up the region's weak banking sector. The Gokal consortium continued operations in Iraq—even starting joint cement ventures with Iraqi companies—until 1968, when the family patriarch was executed, along with thirteen Pakistanis, by the Iraqi Baathists on charges of spying for Israel. The firm's assets were subsequently nationalised by the Iraqi government. Gokal's nephews left Iraq and would later be leading underwriters of the al-Khoei Foundation, an important transnational Twelver Shīʿī organisation, and carry on a brisk business with Iran during its war with Iraq in the 1980s.Footnote 74 Only after 2003 did the Twelver Khojas re-establish their pilgrimage infrastructures in Iraq's shrine cities.Footnote 75

But during the first decades of the twentieth century, as sovereign power in Iraq vacillated among the Ottomans, British and Hashemites, Bohra and Khoja firms remained a small, albeit consistent and successful, presence. The ability of commercial firms from these groups to assimilate themselves to local conditions assisted their efforts to construct a pilgrimage infrastructure between Iraq and western India and to participate in the transregional economy of locative piety. With the aid of existing community networks across the Indian Ocean and the increasing ease of travelling between Bombay, Karachi and Iraq, Bohra and Khoja commercial firms transitioned easily into the business of managing pilgrimages, which marked yet another addition to their ever-expanding, multifaceted business portfolios. It was not without cause that the new brand of Gujarati Bohra and Khoja pilgrimage guides studied in the next two sections were penned and financed by merchants. The narrative first examines the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī before taking up the Khoja experience.

The Faiż-i Ḥussainī and the Making of the Bohra Pilgrimage

This section analyses the inner workings of the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī in Iraq through interwar Urdu and Gujarati travelogues. The Faiż-i Ḥussainī best illustrates the close cooperation between Bohra merchants and the community's religious leaders in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 76 The institution owed its beginnings to two Bohra merchants, ʿAlībhāʾī Karīmjī and Shaykh ʿIsajī Adamjī, who around 1882 first established a reception hall at a Bohra mosque in Karachi. There, Bohra pilgrims travelling to Iraq could obtain comfortable accommodation and avoid the dire conditions of quarantine most travellers experienced while passing from Bombay through Karachi.Footnote 77 In 1887, ʿAlībhāʾī Karīmjī purchased a site in Karachi for Rs. 35,000 and built a complex for pilgrims, then handed its management over to the Bohra dāʿī al-muṭlaq, ʿAbd al-Ḥussain Hussām al-Dīn. By 1897 a ten-person executive committee was established (Kārobārī kameṭī) with a president and secretary, thus formally inaugurating the Faiż-i Ḥussainī.Footnote 78

According to an Indian court case filed in Bombay in 1946 and concluded in 1950, this committee of trustees, in one form or another, administered the institution until May 1924. That year a minority of trustees altered the original 1897 deed of declaration and transferred the ownership stake in the trust to the Bohra dāʿī al-muṭlaq, Mullā Ṭāhir Saif al-Dīn.Footnote 79 This act led the non-signatory trustees to resign their posts, presumably in protest. The 1924 alteration continued to be a source of conflict until 1951 when the court case was finally settled. Notwithstanding these acrimonious quarrels, under the guidance of the trustees and the dāʿī al-muṭlaq, the Faiż-i Ḥussainī's initial income of Rs.10–15,000 grew to mammoth proportions, with the property in its possession by 1928 said to be valued at 30–35 lakhs.Footnote 80 Part of that success stemmed from its linkages to other Dāwūdī Bohra religious institutions, such as the Dawoodi Fund, which was under the direct supervision of the dāʿī.Footnote 81

A map printed by the Faiż-i Ḥussainī in the 1960s gives a sense of the institution's scale of operations, and its role as the animating force behind Bohra overseas pilgrimage (Figure 6). Nowhere else was the Faiż-i Ḥussainī more central to the smooth running of Bohra religious pilgrimage than in Iraq's Shīʿī shrine cities, although in time it enlarged its operations to include all-expenses-included pilgrimage tours to Mecca, Medina, Egypt, and Yemen, the latter two salient sites for Bohras on account of their links to the Fatimids. As mentioned earlier, Bohras had a tiny presence in Iraq throughout the nineteenth century. But only with the Faiż-i Ḥussainī was a fully-fledged institutional framework created to ensure that Bohras visiting Iraq had adequate accommodation and provisions during their pilgrimage. Commercial interests facilitated the growth of this network, with the aforementioned Bohra firm, Abdul Ali & Co. functioning as the Baghdad agent of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī.

Fig. 6. Map of Bohra pilgrimage itinerary produced by the Faiż-i Ḥussainī in the 1960s. Pākistānī Dāudī Vohrā Vastī Patrak (Karachi: 1966), p. 129.

One attains an unparalleled glimpse of the everyday workings of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī in Adamjī Musajī's Gujarati 1924 pilgrimage guide titled Rāhe Karbalā (The Road to Karbala).Footnote 82 Composed and published in Karachi following the author's third pilgrimage to the shrine cities, Musajī's guide offers unique insights into how Bohra-run institutions in Bombay, Karachi and Iraq facilitated the journey of Bohras from western India to the Iraq at a level of organisation unimaginable for many Indian Muslims who undertook Hajj and other pilgrimages in the same period. Indeed, Rāhe Karbalā was but a small blip in the cosmos of Urdu pilgrimage guides written for Hajj. But when these are read alongside Musajī's work it is evident how susceptible other Muslim communities were to the vicissitudes of weather, the dearth of banking facilities, the machinations of pilgrimage guides, and the paucity of local accommodation when undertaking pilgrimage.

Corroboration for this comes from many non-Bohra sources, such as the travelogue of Mīr Asad ʿAlī Khān, a notable from Hyderabad who travelled to Iraq and Iran in the late 1920s. Visiting Najaf, where he lamented the poor state of hygiene compared to India, ʿAlī Khān complained that there was no special organisation set up for the benefit of pilgrims, other than those institutions created by the Bohras for their own community.Footnote 83 In Karbala he observed a similar phenomenon of disorganisation, but there, in addition to the Bohra musāfirkhānas, he found that leading Indian Shīʿī amīrs had purchased properties for the benefit of pilgrims.Footnote 84 (In fact, many Indian landed gentry had sent money to refurbish select sites in theʿAtabāt, with the Raja of Mahmudabad funding the construction of a cupola (guṃbad) and an enclosure at the shrine of Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq.Footnote 85) Still, neither the accommodation facilities, nor the prestige projects subsidised by Indian Shīʿī amīrs, did much to alleviate the relative disorder that was a constant refrain in ʿAlī Khān's account. This was not entirely fair, and other non-Khoja Twelver pilgrimage accounts do praise southern Iraq's transport infrastructure and the ready availability of good food and accommodation. But what unites them all is the conviction that Bohra and Khoja institutions were in a league of their own.

In actuality, Musajī's text was not the first Bohra printed pilgrimage guide: an earlier pilgrimage text focusing on the shrines of southern Iraq was composed in Lisān al-Dawat (‘Bohra Gujarati’; Gujarati written in Arabic letters) and published in the years before the Faiż-i Ḥussainī was established. Its opening line assured the reader “There is a tradition narrated by the honorable Prophet of God—Peace be upon him and his family—where he decrees that the person who intends to undertake pilgrimage (safar), and offers prayers and supplications with veneration and humility, will have the hardships of his pilgrimage eased, adversities banished, and fear of the road traded for security by God Almighty”.Footnote 86 But, despite passing references to the transport itinerary, this text was largely a description of the shrines themselves and a digest of prayers to say within them. It did not give the Bohra a sense of the practical logistics of pilgrimage as Musajī's 1924 guide did.

More akin to Musajī's text was ʿAbd Allāh Ḥussain Hākīmjī Buṭwāla's 1908 Gujarati Dalīlul Hujjāj, written for Bohras performing Hajj, Umrah and pilgrimage to sites in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Iraq.Footnote 87 Given his opening dedication to the dāʿī al-muṭlaq, Sayyidnā ʿAbd Allāh Burhān al-Dīn, it is fitting that Buṭwāla's guide contains passing references to the forty-ninth dai's creation, the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. Jeddah was one site where the local branch manager assisted pilgrims with billeting and luggage.Footnote 88 But it is plain that the Faiż-i Ḥussainī was still in a provisional stage at the time of Buṭwāla's travels. In Mecca, for example, the musāfirkhāna built by the Bohra millionaire Adamjī Pīrbhāʾī housed pilgrims, not the Faiż-i Ḥussainī.Footnote 89 What is more, sizable portions of Buṭwāla's text show that he was dependent on local accommodation throughout his pilgrimage. Only once he departed Syria and entered Iraq did the Faiż-i Ḥussainī appear again on his itinerary, with the author encouraging pilgrims to cable the institution's local office in Baghdad upon arrival in Ramadi.Footnote 90

By contrast, Musajī, who published Rāhe Karbalā some fifteen years later, supplied a detailed insider's view of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. As he explained, he had undertaken a pilgrimage to the ʿAtabāt on three occasions: once as a child before the First World War, once during the conflict, and once more thereafter. His latest trip, completed a year before, formed the basis of his 1924 account (see Figure 7). How much changed from one journey to the next he does not say, but he did extol the British occupation of Iraq as a boost to the pilgrimage, noting that “the gracious British government took possession” (māyāḷu Briṭiś angrej sarkārnā hathmāṇ) of the country and governed it according to the same customs of rule as Hindustan.Footnote 91 But with the exception of his introductory section on passport control, the British presence is a phantom one throughout the pages of the guide. At least in the way Musajī depicted it, the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, which acted as both chaperone and intermediary between the pilgrims and state authorities in India and Iraq, was far more instrumental.

Fig. 7. Gujarati map of Iraq and its main railways included in Musaji's Rahē Karbalā.

With a print run of over 2,000 copies, the opening pages of Musajī's text featured extensive advertisements from Bohra commercial firms, such as Karachi's ‘B. Abdul Rahim & Sons. Co’ and Poona's Fancy Leather Goods Factory under the ownership of one ʿAbd al-Ḥussain Jaʿfarjī, yet another indication of the intimate links between Dāwūdī Bohra mercantile firms and the infrastructure of religious devotionalism between Iraq and western India.Footnote 92 These advertisers were included in part because, as one early section declared, pilgrims had to purchase an array of items to make their journey as comfortable as possible.Footnote 93 These included everything from incense to ghee, and should the pilgrim fail to purchase any of these articles in advance, they were stored in abundance at the branches of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī within Iraq. In one memorable instance Musajī even remarked, “Fear on the roads should be no problem at all, for there…by the grace of God, our community has made the necessary provisions in all places, and the warmest of food and coldest of water is given to pilgrims by the Faiż-i Ḥussainī”.Footnote 94 Considering the paucity of fresh water in the shrine cities that other Indian Shīʿī pilgrims (such as Mīr Asad ʿAlī Khān and a Khoja commentator below) complained about, this was a distinct edge.

Musajī supplied some useful background information on the beginnings of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. At its creation, the fund was originally titled the ‘Phaṇḍ (fund) Husenī’ and the brothers of the dāʿī al-muṭlaq and prominent merchants were appointed as custodians.Footnote 95 From the first, as part of its annual practice, the caretakers released an annual expenditure report, which supplied details on the inner workings of the fund.Footnote 96 Not unlike a modern-tour company, as part of the image of transparency that the managers of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī wished to project, pilgrims also had recourse to a telegraph complaint line, with Musajī bidding his readers to write to the “sekraṭarī” in Karachi should they experience any problems in the course of their interactions with the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. For the contemporary ḥajjī, recourse to such resources would be largely unthinkable.

Karachi's meteoric advance by the century's end made it a natural contender for the head office of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī. The decision to place the headquarters of the fund in the city was applauded by Musajī, who hailed Karachi as a place whose development was intimately linked to that of his own community (kom). After all, Karachi was home to the waqf of Shaikh Jiwānjī Ibrāhīmjī (a prominent Dāwūdī Bohra merchant), the Ḥussainī mosque and madrasa, and a booming Bohra merchant presence in the bazaar.Footnote 97 In fact, the Faiż-i Ḥussainī quickly became the nerve centre of Bohra life in the metropolis, with pilgrims passing through Karachi from Bombay on their way to Iraq—and even “brothers coming to Karachi for work” finding a free meal and a bed at the city's branch.Footnote 98

Musajī's text offered the would-be pilgrim a handy vade mecum (guidebook) containing in-depth discussions of passport regulations, steamer ticket fares from Karachi to Basra, and the state of the Iraqi railways. When all expenses were taken into account, the costs incurred by a single pilgrim travelling in ‘normal class’ on steamers, trains, and horse carriages would amount to some Rs. 285.Footnote 99 This was a competitive price in light of the many goods and services the Faiż-i Ḥussainī furnished, and the various transport costs associated with the trip. While the ferrying of Bohra pilgrims from Karachi to al-Muqal, the port of Basra, was handled by the British India Steam Navigation Company, the agents of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī immediately picked up the thread once the pilgrims touched down on Iraqi soil. A team of managers and bearers greeted pilgrims at the port and Basra's train station and, for a fee, transported their luggage to the local branch of the Faiż, and supplied horse carriages (ghoḍā gāḍī) and motor cars to convey the new arrivals.Footnote 100 The Faiż's employees also collaborated with the pilgrim inspectors appointed by the Iraqi railroad, likely acting as translators for the Gujarati-speaking pilgrims and negotiating ticket rates and itineraries.Footnote 101

Once at the local branch of the Faiż, the pilgrims typically were served a meal, performed ablutions, and changed their clothes, while the institution's managers arranged for transport to the nearest holy sites. Such was the routine in Baghdad, Najaf, Karbala, Musayyib, Kufa and Samarra, where the local branches of the Faiż assumed the role of minder.Footnote 102 Once again, the contrast with the experience of most Indian Muslim pilgrims on Hajj, or even Indian Twelver pilgrims in Iraq—who regularly complained about the lack of clean water and the inability of Indian-owned companies to supply food to pilgrimsFootnote 103 —is rather striking.

All the same, the Faiż-i Ḥussainī could not mitigate all problems associated with travelling in Iraq. As Musajī emphasised, one of the great disadvantages of undertaking pilgrimage there was that the currency in circulation was very sparse, the state of banking quite poor, and the exchange rate in the bazaar very unfavourable to Indian pilgrims (a Khoja traveller examined in the next section of this article offers an alternative impression of these matters). What Iraq did have to its advantage was a steady fleet of hirable automobiles that Bohras and Khojas alike chartered with great ease from the early 1920s. In Baghdad, a pilgrim could hire a four-passenger motor car for some Rs. 20, while one could travel by car from Najaf to Karbala in around three hours.Footnote 104 In many instances, Bohras also utilised horse-drawn carriages and tramways to move within cities and motorcars to shuttle between cities (see Figure 3).

Thanks to the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, pilgrimage to Iraq only grew among the Bohras from the 1920s onwards. The fifty-first dāʿī al-muṭlaq, Ṭāhir Saif al-Dīn, visited Iraq in 1934 with an entourage of 400 Bohras and met with Iraqi government representatives to discuss the state of Bohra awqāf.Footnote 105 In 1936 and 1940, he donated two massive ḍarīḥ to shrines of Imām ʿAlī and Imām Ḥussain in Najaf and Karbala, the expenses of which came out to “2 lakhs of tolas of silver and 500 tolas of gold” for Imām Ḥussain's tomb, and “6 lakhs of tolas of silver and 2,000 tolas of gold” for that of Imām ʿAlī, as one official Bohra publication beamed.Footnote 106 Three decades later, he donated a newly refurbished ḍarīḥ for Imām Abbās in 1963. This was part and parcel of Ṭāhir Saif al-Dīn's enthusiastic support for donating to a range of Islamic holy sites throughout the Middle East, acts that earned him a reputation as something of a connoisseur of Islamic antiquities. There were sizable donations to the Supreme Muslim Council of Palestine,Footnote 107 and to the Saudi government for the refitting of the kiswan, the ornamental carpet draped over the Kaʿba in the Masjid al-Ḥarām in Mecca.Footnote 108 Not all were impressed: the Egyptian critic Zakī Mubārak (who taught in Iraq in the 1930s) asked “What benefit is there for Iraq that the Sultan of the Bohras spends thousands of dinars to beautify holy places in Najaf and Karbala?”Footnote 109

It is worth briefly noting that the Faiż-i Ḥussainī was also a significant fixture in the pilgrimage life of Mecca and Medina in this period. During Hajj in 1934, Ghulām Rasūl Mehr, the prolific historian and Ghalib biographer of Sunni background, was greatly impressed by the Faiż-i Ḥussainī's operation in Mecca. To his mind, no building in Mecca matched the beauty and density of the premises of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, with its capacity to hold thousands of Bohra pilgrims. As in Iraq, pilgrims were provided three meals a day and it was open only to Bohras. The institution left such an impression on Rasūl Mehr that he wrote “Many would wish for the construction of a spacious, roomy ribāṭ for all Indian Muslims, with no consideration of distinction between Bohras or any other jamāʿat, indeed for any Muslims from India who descend there”. To achieve this he proposed that, with Saudi approval, the site of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī could be expanded to house 20,000 Muslims. Similar arrangements could be made at the ribāṭs constructed by the rulers of Hyderabad, Bhopal and Bahawalpur in Mecca. These would assume the care of Indian pilgrims and distribute provisions as the Faiż-i Ḥussainī did.Footnote 110 Although as a non-Bohra Rasūl Mehr was not permitted to stay in the Meccan branch of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, he was invited to a large banquet there, where he marvelled at the quality of the food and Bohra dining practices, which included drinking from a communal glass cup. Rasūl Mehr's account once again underlines the ability of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī to craft a trans-imperial pilgrimage infrastructure in several places in the late Ottoman/post-Ottoman Middle East that other Indian Muslims saw as worth replicating.

In many ways, the Twelver Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure offers instructive parallels and divergences from the Bohra case. If the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī gives the appearance of near total self-sufficiency (except in matters of transport), then the Khoja infrastructure was more diffuse, relying initially on unintegrated community institutions that only became organised under an umbrella trust in the 1930s. As with the Bohras, infrastructural development and the influx of Indian military and civilian labour and capital that accompanied Britain's Mandate in Iraq strengthened Twelver Khoja initiatives. But, as a travelogue examined in the next section demonstrates, a Twelver Khoja might be forced to turn to Hindu pearl merchants, Bengali sepoys, English railway station masters and Iraqi Jewish taxi drivers when in duress. Even so, none of this meant that caste ties were irrelevant, and Khoja caste status was a decisive means of differentiation, least of all from other Shīʿa, Ismāʿīlī and Twelver alike.

“In your Faiż will there be space for me this evening?” :The Twelver Khoja Pilgrimage

The Twelver Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure in India and Iraq was the handiwork of leading community merchants, who funded local Arab guides and mujtahids alike. Just as the Bohra firm Abdul Ali & Co. acted as local manager for the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, the head of Basra's Twelver Khoja jamāʿat, Jethabhāʾī Gokal administered the local branch of the the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjatanī, which provided goods and services to Twelver Khoja during their pilgrimage to the shrine cities. The term Panjatanī invoked the five figures from the ahl al-bayt revered by Shīʿīs: the Prophet Muḥammad, ʿAlī, Fāṭima, Ḥassan and Ḥussain. This institution was founded in Bombay in 1912, and, in keeping with Twelver Khoja communal life generally, was managed by leading Twelver Khoja merchants in Bombay, Karachi and Basra from its inception. Operating from its headquarters on Samuel Street in Bombay, the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjatanī was registered as a trust in 1932 and expanded its services to Hijaz, Iraq and Iran.Footnote 111 Throughout these years the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjatanī continued to rely on the support of Twelver Khoja business magnates, such as Ismāʿīl ʿAbd al-Karīm Panjū, senior partner of the firm Husein Abdulkarim Panju and E. A. Karim. Although a native son of Zanzibar, Panjū migrated to Bombay during the First World War, where he built a diverse business portfolio. He later served as treasurer of the anjuman, in addition to being a Director of Habib Bank, founded in 1941 by the Twelver Khoja Muḥammad Habīb, which later became the cornerstone of Pakistan's early commercial banking sector and was active in the Gulf from the 1950s.Footnote 112

Despite having a local jamāʿat in Basra from the late 1910s, and though the managers of the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjatanī and Twelver Khoja merchants were energetic in the creation of musāfirkhānas (rest houses) in the shrine cities, the Twelver Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure was not quite as stage-managed as the Bohra Faiż-i Ḥussainī. Twelver Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure, nonetheless, functioned as a boundary mechanism to distinguish the community from Bohras, Ismāʿīlī Khojas and other Twelver pilgrims. This is best demonstrated in the work, Kāshīthī Karbalā (From Kashi to Karbala), a Gujarati pilgrimage guide written by a Twelver Khoja, Khojā Lavjī Jhīṇā Māstar Banāras, who travelled to Iraq from his home in Benares (or Kashi as he, and many other Indian Muslims, called it).Footnote 113 Even if Jhīṇā Māstar emphasised the crucial role of Twelver Khoja institutions in supplying accommodation and pilgrimage guides in Iraq, there is unfortunately no direct mention in Kāshīthī Karbalā of the Anjuman-i Faiż-i Panjantanī, which suggests that by the time of Jhīṇā Māstar's journey the institution had not yet achieved the critical mass that it did in later decades. It is likely that subsequent Twelver Khoja pilgrimage guides—such as one published in the early 1930s titled Rāhnumā-i Faiż—accorded greater value to the anjuman.Footnote 114 Nonetheless, this is not a fatal omission, for in Kāshīthī Karbalā one glimpses the consolidation of a Twelver Khoja pilgrimage infrastructure where caste and merchant wealth were decisive arbiters.

Tetchy and sardonic, Jhīṇā Māstar's account is in keeping with contemporary works of Twelver Khoja devotion, with its free use of vocabulary like dharm and darśan (as opposed to ‘dīn’ and ‘dīdār’), terms that in the ensuing century have increasingly been coded as ‘Hindu’. In his late 50s at the time he travelled to Iraq, Jhīṇā Māstar described himself as a “merchant and commission agent”, and his text is replete with references to southern Iraq's commercial landscape, which he compared to his more familiar haunts in British India, such as Calcutta's Canning Road.Footnote 115 In fact, a branch of his current employer, Seth R. Maherali & Sons, was located in Basra.Footnote 116 The appendix to Kāshīthī Karbalā boasted that the author's name “Māstar” was registered in all the famous commercial directories of India, and also contained some self-interested remarks on the quality of his business. Based on references in the text, Jhīṇā Māstar's business portfolio stretched, in one form or another, from Benares to Calcutta, Malaya, Ceylon and Siam. For all this gallivanting, his conclusion was an overture to wealthy Twelver Khojas to not overlook the “sacred land” of Iraq in preference for travelling to Japan, China, America and England on business. Fortunes, both spiritual and material, were to be had in Iraq as well. Equally noteworthy is Jhīṇā Māstar's passing comment that he was at one time the Benares branch manager for the enormous mercantile firm, Meherali Fazulbhoy Chinoy & Co., the namesake of which was a prominent Ismāʿīlī Khoja and loyal supporter of the Aghā Khān. If Jhīṇā Māstar was once an Ismāʿīlī, then his employment history presents the tantalising question of whether, upon the ‘conversion’ of one member of the firm, Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Khojas continued to collaborate as business partners or whether ties were severed.

Intra-Khoja rivalries are evident in the first pages of Jhīṇā Māstar's text, where he cited for effect an opinion delivered in 1920–1 by a judge in the Bombay High Court who criticised the Khojas’ religious illiteracy. To the author's mind, as the Khojas became more educated about Islam they would begin to identify themselves as Twelvers, as many in recent decades already had. Inexorably, Twelver Khoja mosques, madrasas, hostels, and thrifts (such as ‘the Hidayat Fund’ and the ‘Khoja Indigent Fund’) were being established in various regions to solidify this new status, and the circulation of monthlies like Rāhe Najāt and Nure Hidayāt deepened the Khojas’ familiarity with Twelver Shīʿī doctrine.Footnote 117 According to Jhīṇā Māstar, the growing subset of Twelver Khojas likewise began to see Karbala as a focal point of their faith and to revere Imām Ḥussain as the saviour (bacāvanār) of Islam.Footnote 118 They were not alone, with Jhīṇā Māstar remarking that even Mahatma Gandhi grasped the sanctity of Karbala and the example of self-sacrifice embodied by Imām Ḥussain.Footnote 119 Pilgrimage, he added, was the surest expression of this love (muhabbat) for the line of ‘true’ imāms and an assertion of Twelver Khoja identity.

Jhīṇā Māstar embarked upon his pilgrimage on 6 October 1921, proceeding, with his wife and young son, from Benares eastwards on the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway to Karachi, whence he took a steamer to Iraq, travelling intermediate class. From the start, the high proportion of Twelver Khoja civil servants assisted him handily: a friend who was a magistrate in Benares obtained a passport for him in a single day.Footnote 120 All the same, as Jhīṇā Māstar himself stressed, pilgrimage was not merely for the wealthy Khoja, and pilgrims of any class could undertake the journey provided they did not leave much to fate (kismat). By and large, the vicissitudes of kismat could be mitigated because of Twelver Khoja merchant wealth, traces of which dotted the route from India to Iraq. “In Bombay”, the author wrote, “there are 2–3 musāfirkhānas constructed by our [Khoja] brothers for pilgrims. Among these, Śeṭh Hajjī Devjībhai Jamāl's musāfirkhāna is open for all types of Twelver Shias, whereas two are only for Khoja pilgrims”.Footnote 121 Karachi meanwhile boasted a “beautiful musāfirkhāna” constructed by Śeṭh Hajjī Ghulām ʿAlī Chalga, which could house “eight families at once easily”. This hostel offered pilgrims water taps, electricity, toilets and cooking facilities, even fully furnished rooms. Yet once he departed Karachi, Jhīṇā Māstar learned the hard way that in Iraq itself Twelver Khoja infrastructure was not as well-managed.

When read alongside Musajī's Rāhe Karbalā, Jhīṇā Māstar's text conveys notable similarities and differences with the Bohra pilgrimage. While the Faiż-i Ḥussainī appeared to shadow Musajī on every stage of his journey, Khoja institutions were more dispersed in Jhīṇā Māstar's account. They no doubt attenuated many inconveniences that Jhīṇā Māstar and his family endured, but more often than not the author had to turn to non-Khojas when in need. Helpfully, in sections Jhīṇā Māstar drew a contrast between Khoja institutions and the Faiż-i Ḥussainī and even interacted with Bohra pilgrims. His high opinion of the Faiż-i Ḥussainī was not entirely replicated in his depictions of the latter. In his section on passports he wrote:

An association [saṁstha] has been established by the Faiż-i Ḥussainī of our Bohra brothers. Every wealthy member of the community, by giving it extensive financial help, has placed that association on a very sound footing. First-rate assistance is rendered by it to Bohra pilgrims in order to acquire passports and find passage on the steamer in Karachi. Besides this, superior arrangements for Bohra pilgrims are made by this association in Basra, Najaf Sharīf, Karbala Muʿallā and other places too.Footnote 122

Be that as it may, Jhīṇā Māstar learned firsthand that Bohra and Khoja caste distinctions died hard in the course of pilgrimage. Before discussing this in detail, however, some descriptive background from the travelogue is needed. Touching down in Basra, a city where he knew various Twelver Khojas by name only, he had a humorous exchange with a British customs officer over the tobacco that he was bringing into the country, though he suffered the indignity of having his family's luggage rummaged through and unpacked. Before disembarking and entering the city, Jhīṇā Māstar was warned by a Hindu merchant from Surat—who was on his way to collect pearls in Bahrain—that accommodation was very sparse in the city. The merchant advised the author that he should leave his son on board the vessel and find lodgings in the city on his own. Jhīṇā Māstar was troubled by this, writing that he never experienced such a thing in his travels to Penang, Singapore and Bangkok. When coupled with his annoyance at the lack of local Twelver Khoja-run accommodation, these remarks display show that, although Iraq was a site of increasing Twelver Khoja religious and economic interest, it as yet lacked the community institutions on which Jhīṇā Māstar and other Twelver Khojas depended in their travels from Southeast Asia to East Africa. This ensured that the Twelver Khoja pilgrimage experience necessitated moving in and out of caste boundaries, even if this was rarely by choice.

Khojas were certainly to be found in Iraq, though at times with difficulty. In contrast to Musajī's accent on the poor monetary situation, Jhīṇā Māstar was keen to point out that Khojas were able to conveniently purchase hundis from “our brothers’ shops in Basra”.Footnote 123 Accommodation proved more difficult to come by. While struggling to find lodgings, the author managed to hire a car with the intervention of a Bengali sepoy at Basra's train station (he evidently knew Bengali because of his time in Calcutta). In the train station Jhīṇā Māstar happened upon a group of finely dressed Bohras who were attempting, in a mix of broken English and Hindi, to purchase either first or second class train tickets from the British station master. When they were told that all first and second class tickets were sold out for the next two days, and that only third class tickets were available, Jhīṇā Māstar approached the window and asked the attendant, “Anything for this old man Sir [?]”Footnote 124 Sensing the author's anxiety, the station master asked “Do you want to go in third class?” Though he offered this option, the station master later warned Jhīṇā Māstar that travelling in third class in Iraq was not like India, as some trains lacked toilet facilities. By Jhīṇā Māstar's own admission, he froze upon hearing these words.

In the midst of this exchange, a white-bearded Bohra dressed in a black tunic stood at the window. Taking Jhīṇā Māstar to be a fellow Bohra, he asked the author: “How are you brother, why don't you come to the Faiz Mandi (fej mandi)?”Footnote 125 In turn, Jhīṇā Māstar shrugged off the overture, saying that he could not come to the Faiż-i Ḥussainī, but the Bohra persisted in his offer. When he eventually asked Jhīṇā Māstar why he refused to come, Jhīṇā Māstar retorted: “Sir, do you want to know the reason? I am of the Khoja caste. In your Faiż will there be space for me this evening?” Jhīṇā Māstar records that upon hearing this the Bohra went cold from head to toe, and silently began stroking his beard. While the Bohra remained speechless, Jhīṇā Māstar pressed him again for an answer, and when the interlocutor finally managed to muster a response the topic of conversation suddenly changed. Following the Bohra's departure, the British station master asked Jhīṇā Māstar why he did not accompany him. Jhīṇā Māstar answered: “You stayed in Mumbai and Calcutta so you can understand. He was a member of the Bohra caste and I was a member of the Khoja caste. This was the reason I could not go with him up to his dharmaśāḷā for the evening”.Footnote 126

Just as he praised Bohra pilgrimage infrastructure, while also stressing the prevalence of caste distinctions, Jhīṇā Māstar also accented how Khoja caste identity differentiated Twelver Khojas both from Ismāʿīlīs and non-Khoja Twelvers. In particular, without the Twelver Khoja mercantile footprint in Iraq, Jhīṇā Māstar's pilgrimage would have been a good deal more onerous than it already was. On occasion, Twelver Khoja merchants and their agents came to fetch the author from the train station and supplied accommodation.Footnote 127 Like the Bohra Musajī, Jhīṇā Māstar was able to rent automobiles at an affordable rate. In league with the clerk of a “Zanzibari Khoja”, on his way to Karbala from Hilla he chartered a taxi owned by an Iraqi Jew who could speak a smattering of broken English.Footnote 128 But once in Karbala there was no guarantee of finding accommodation, and with two lakh pilgrims (200,000) huddled in the city, the author once again fretted about where to stay.Footnote 129 When the Iraqi Jewish taxi driver attempted to unceremoniously drop off his charges in this bustling crowd, the author and his fellow passengers refused. Eventually, the driver relented and dropped them off at the entrance of the bazaar.

Left unpropitiously at the bazaar gate, they were approached by an Arab mutawallī (trustee; pilgrimage guide), whom Jhīṇā Māstar initially compared to Hindu pilgrimage guides in Benares who sat in wait for pilgrims with children and automobiles, evidently the most lucrative catch. These mutawallīs performed the same task of shepherding Jhīṇā Māstar and his family as Faiz employees did in Musajī's account. According to Jhīṇā Māstar, such mutawallīs were employed by Twelver Khoja institutions. As an illustration, while in Karbala the mutawallī at the bazār greeted Jhīṇā Māstar and the other pilgrims in Kachchhi, asking “Are you Khojas?”Footnote 130 Jhīṇā Māstar remarked that though the mutawallī was an Arab, he was not surprised he spoke Kachchhi, surmising that the man had travelled to Karachi, Bombay and Calcutta. Consequently, Jhīṇā Māstar replied in Gujarati that they were indeed Khojas from Benares, by way of Bhavnagar. Upon hearing this, the mutawallī recalled the founder of the [Twelver Khoja] Hidayat Fund, Hajjī Ghulām ʿAlī Ismāʿīlī. Purportedly, the mutawallī had done rather well because of the Hidayat Fund, with Jhīṇā Māstar commenting that it was as if the mutawallī had been drenched in “the rain storm of the Hidayat Fund”.Footnote 131 It was money well-spent, as the mutawallī handled Jhīṇā Māstar's luggage with great care and found the group lodgings in the musāfirkhāna erected by Śeṭh Qāsim Nanjī, a Twelver Khoja merchant from Bombay. Several other Khoja musāfirkhānas also existed in the city.Footnote 132