‘There are no Jews in Cuba, but there are homosexuals.’ Footnote 1

– Jean-Paul Sartre

State repression is one of the most unfortunate recurrent features of world politics. Yet we still know relatively little about why states violently repress their citizens. In some cases, repression follows a straightforward logic: states resort to repression when challenged (Davenport Reference Davenport2007a). In other cases, however, it is less obvious why states repress. Why do states sometimes abuse vulnerable populations that are unable to pose a serious challenge to their authority? Recent examples of states cracking down on groups such as sexual minorities, small religious sects, refugees and others with a limited ability to violently contest the state provide ample evidence that states also single out relatively unchallenging populations for collective punishment. This article turns to the first of these instances: state repression against sexual minorities.Footnote 2

Beyond the normative importance of this subject, the repression of sexual minorities deserves attention as an unusually puzzling form of minority discrimination. While the literature on ethnic minority discrimination and repression is extensive (Gurr Reference Gurr2000; Gurr and Harff Reference Gurr and Harff1994), there is frequently a simple logic to why states persecute these groups. For one, scholars have long observed that ethnic minorities are at risk of repression when the state views them as potential sources of rebellion, insurgency or other forms of potentially violent collective action (Gurr Reference Gurr1993). Researchers are divided on the question of whether repression can effectively curtail ethnic violence (Jakobsen and Soya Reference Jakobsen and de Soya2009; Piazza Reference Piazza2011), but there is little doubt that ethnic minorities often harbor the capacity to violently contest the state (Gurr Reference Gurr2000). The potential for violent collective action is also heightened when ethnic groups reside within a national homeland that could separate from the state (Pape Reference Pape2005; Toft Reference Toft2005). Sexual minorities, however, lack the capacity for large-scale, violent mobilization. Since they are unable to present a violent challenge to the state, what can explain their repression? The implications of this question extend beyond homophobic repression, and provide valuable insight into why states harm their most vulnerable civilian populations.

This article maintains that revolutionary governments are more likely to target LGBT people than other minority groups due to strategic and ideological factors unique to these regimes. Strategically, identity-based repression of sexual minorities resembles selective repression that targets individuals based on their actions against the regime, since accurately targeting sexual minorities similarly requires gathering fine-grained information. Why, however, would states absorb the costs of properly monitoring, identifying and targeting individuals who have not defected against the regime? As has long been observed, revolutionary governments are especially susceptible to both external and internal threats following the revolution (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979; Walt Reference Walt1996). This potential instability gives revolutionaries an incentive to preventatively repress identity groups perceived as ‘unreliable’ even before they defect; in other words, identity is used as a proxy for allegiance. This is true even for identity groups that are unable to mobilize for violent collective action, such as sexual minorities, since they could defect against the regime by providing information and auxiliary support to enemies. Moreover, revolutionaries have an incentive to demonstrate their ability to selectively punish in order to deter prospective defectors. One way to signal the ability to punish potential defectors before they have acted against the regime is to target members of ‘invisible’ identity groups. Since sexual minorities have few outward markers of their difference, accurately targeting them signals to potential defectors that the regime can effectively monitor and punish them.

This strategic logic explains why revolutionaries target ‘unreliable’ and ‘invisible’ groups, but not why they would perceive LGBT people as unreliable, or why they would select them for punishment from numerous available invisible groups. Ideology accounts for the construction of sexual minorities as potentially threatening or undesirable. Many revolutionary elites adhere to exclusionary ideologies – such as communism, fascism or Islamism – that justify repression and violence against ‘real or perceived enemies of the new order’ they seek to implement (Harff Reference Harff2003, 57, 63). Exclusionary revolutionaries are inherently revisionist, in the sense that they reject prevailing liberal, individualist legitimizing principles of the state in favor of representing collectivities (for example, socioeconomic, ethnic or religious groups). Exclusionary elites are therefore predisposed to viewing LGBT identities as products of liberal individualism, an inference not without some grounding in reality (Frank and Mceneaney Reference Frank and Mceneaney1999), and therefore to portraying LGBT people as unreliable threats to their revolutionary homogenizing projects.

State Repression

Why do states repress? Examining why states target sexual minorities cannot be separated from a broader understanding of why states repress their subjects at all. Reviewing the entire literature on state repression is beyond the scope of this article; I briefly survey three causal factors identified in the literature that are relevant to this project: strategy, ideology and regime type.

One of the most robust findings in the repression literature is the ‘law of coercive responsiveness’ – the observation that states respond to challenges with repression (Davenport Reference Davenport2007a). This focus on strategic incentives for repression is a thread that runs through research on the various forms of state repression. For instance, it has been argued that the incentives for extreme types of repression are greatest during war. For instance, states are more likely to perpetrate mass killings when faced with guerrilla insurgencies, since indiscriminate violence is an effective means of eliminating insurgents hiding among the civilian population (Valentino, Huth and Balch-Lindsay Reference Valentino, Huth and Balch-Lindsay2004; see also Lyall Reference Lyall2010). Similarly, Straus (Reference Straus2007, Reference Straus2012) has found that genocide has been used as an extension of regular warfare. Shaw (Reference Shaw2003) conceptualizes genocide as a form of ‘degenerate war’ in which civilians are framed as enemy combatants. A recent study that empirically adjudicates among the common explanations for repression finds that civil war is its best predictor (Hill and Jones Reference Hill and Jones2014). In short, there is a consensus that states use repressive violence when confronted with opposition, which suggests there is a strategic logic to state repression.

While not categorically rejecting this strategic element, some studies in the genocide literature have placed greater emphasis on the role that ideology plays in legitimating state violence. In her study of genocide and politicide, Harff shows that exclusionary ideologies – ‘belief system[s] that identif[y] some overriding purpose or principle that justifies efforts to restrict, persecute, or eliminate certain categories of people’ – are pervasive among the state elites who perpetrate genocide (Harff Reference Harff2003, 63). Others similarly posit that ideology helps identify legitimate targets (Straus Reference Straus2012; Straus Reference Straus2015). Extreme repression, according to this view, is most likely when it is easily framed as congruent with ideological goals, such as a Marxist government punishing ‘class enemies’; otherwise the regime’s legitimacy may be jeopardized. Recently it has been argued that the legitimizing force of ideology, which elites use to identify ‘a referent group, an objective, and a program of action’, is necessary for understanding mass killing (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014, 217). Thus it is possible that ideological framing influences repression more than the literature focusing on the strategic incentives for repression would suggest.

Regime type has also received considerable attention as a predictor of state violence. Some scholars support the idea of a ‘domestic democratic peace’, in which democracies minimize repression due to constraining institutions and norms of peaceful conflict resolution (Davenport Reference Davenport2007a; Davenport Reference Davenport2007b; Davenport and Armstrong Reference Davenport and Armstrong2004; Hegre et al. Reference Hegre2001). Evidence of a domestic democratic peace is also validated in the genocide studies literature (Rummel Reference Rummel1994). However, there is some debate regarding the functional form of the relationship between democracy and repression. Some argue that democracy is only effective at reducing repression above a certain threshold (Davenport and Armstrong Reference Davenport and Armstrong2004). Others assert that the relationship takes an inverted U-shape where there is more ‘murder in the middle’, a proposition that has formal theoretical support (Fein Reference Fein1995; Pierskalla Reference Pierskalla2010). Looking more generally at one-sided violence, one study finds that the relationship forms a normal U-shape, with high state violence in autocracies and high insurgent violence in democracies (Eck and Hultman Reference Eck and Hultman2007). Other regime types, such as revolutionary governments, have been linked to mass violence such as genocide and mass killing (Kim Reference Kim2018; Melson Reference Melson1992). Regime type clearly influences the likelihood that the state will engage in repressive actions, but consistent findings beyond the consensus that consolidated democracies are less prone to violence remain elusive.

Revolutionary Homophobia

Why do some states single out sexual minorities for repression? Research on state repression and violence provides little guidance to help explain identity-based targeting. One reason is the distinction between selective and indiscriminate violence that dominates the recent literature (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Kocher2007; Lyall Reference Lyall2009; Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Zhukov Reference Zhukov2018). Whereas selective repression selects individual targets based on their actions (for example, collaboration with the opposition), its indiscriminate counterpart includes any mass events where victims are targeted without regard for their individual behavior. This latter form aggregates two distinct phenomena: (1) widespread, random violence and (2) repression and collective reprisals against identity groups.Footnote 3 Since collective reprisals against identity groups, such as ethnic minorities, disregard their victims’ individual behavior, most scholars consider this violence to be indiscriminate. Sometimes identity-based targeting takes on ‘indiscriminate’ characteristics, such as when warring parties launch attacks against regions where co-ethnics of their enemies reside (Fjelde and Hultman Reference Fjelde and Hultman2014).Footnote 4 However, as others point out, identity-based targeting sometimes serves as a form of selection (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanin and Wood2017, 22–24). This is particularly true when targeted groups are dispersed and difficult to identify, since collective targeting is impossible without incidentally inflicting casualties on individuals outside the target group. Studies of ethnic conflict, for instance, document various ways in which ethnic minorities mask their identities when necessary for their survival (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 48–49). Under such conditions, identity-based violence takes on ‘selective’ characteristics because it requires carefully identifying members of the intended target groups. Attacking indiscriminately when intended targets are difficult to identify risks hitting unintended targets and provoking a civilian backlash.

Repressing sexual minorities almost always bears this resemblance to selective violence. Unlike many ethnic minorities, sexual minorities are geographically dispersed within a given territory and manifest few outside markers of their difference. Similar to selective violence, this indicates that states must expend significant costs to accurately monitor, identify and punish sexual minorities (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006). According to existing theory, states accept the inherent costs of selective violence to punish defectors (that is, those collaborating with the opposition) without risking the civilian defection that can result when the innocent are victimized (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, chap. 7). Understanding why states repress sexual minorities requires tackling the question of why states would willingly absorb the costs of punishing individuals who (1) have not actually defected against the regime and (2) have limited ability to violently contest the state. Although LGBT movements have demonstrated a remarkable ability to mobilize for collective action,Footnote 5 they have little capacity to engage in armed confrontation against the state. This contrasts with ethnic identities, which can form a stronger focal point around which entire groups can effectively mobilize for conflict (Varshney Reference Varshney2003). Anti-LGBT repression therefore presents a puzzling phenomenon when approached from existing perspectives on state violence and repression. In short, we have little systematic explanation for why states would engage in costly repression against identity groups that are incapable of violently challenging their authority.

The strategic logic of revolutionary homophobia

Building on the diverse literatures outlined previously, this article maintains that revolutionary governments – regimes established by overturning existing institutions (Colgan Reference Colgan2012) – are more likely to accept the costs associated with the identity-based repression of sexual minorities (which I consider to be conceptually distinct from ‘indiscriminate’ and ‘selective’ repression).Footnote 6 This relationship between revolution and homophobic repression is expected to hold for both strategic and ideological reasons. On the strategic front, scholars of revolution have long observed that revolutionary transitions produce domestic instability and thereby an opportunity for neighboring states and opposition movements to instigate renewed conflict (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979; Walt Reference Walt1996). Revolutionaries, faced with this potential instability, have an incentive to selectively target individuals they believe support domestic counterrevolution or international intervention, since they could leak valuable information and thereby undermine the regime. Civil war scholars acknowledge that states will target defectors to ensure that valuable information, such as troop movements, remains hidden from the opposition (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, 174–176). Yet the conflict literature largely overlooks the fact that states facing the prospect of internal turmoil have an incentive to deter potential conspirators prior to the outbreak of armed conflict (Greitens Reference Greitens2016, 17–18). As George Kennan wrote of the Soviet Union, the state sought to punish ‘those who might rebel, rather than those who do’ (Kennan Reference Kennan1954, 22, emphasis in original). We can generalize this statement to conclude that revolutionaries prefer to deter individuals who might defect by providing information to distrusted domestic and international agents, rather than reactively punishing those who have already defected by leaking information.

How can revolutionaries effectively determine who might defect? Since prior to the outbreak of conflict there is little opposition with which potential defectors can collaborate – or, in other words, there is insufficient observable behavior with which to select defectors – the regime must rely on proxies to determine which individuals would defect if given the opportunity. During civil war, armed actors may use voting patterns to determine unspoken allegiances to opposition movements (Steele Reference Steele2016). Revolutionary governments, however, generally lack electoral mechanisms for revealing information. Another possible proxy for allegiance is group identity (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanin and Wood2017, 22–24). If certain groups are believed to be ‘unreliable’, then there is an incentive to punish members of these groups to prevent them from defecting; this logic has been used to explain genocidal violence against ethnic minorities (Bell-Fialkoff Reference Bell-Fialkoff1993, 115). Yet even when suspect groups are unthreatening, meaning they are unable to mobilize for violence, they can provide auxiliary support to actors that are capable of rebellion. Sexual minorities are frequently targeted due to suspicions they are unreliable because they are aligned with nefarious actors. For example, right-wing military regimes in Latin America, such as Brazil’s military government following the 1967 revolution, equated homosexuality with leftism and subversion and severely repressed the LGBT community as a result (Brasil 2014, 301). Similarly, in revolutionary Cuba homosexuals were targeted as perceived counterrevolutionaries and punished accordingly (Arguelles and Rich Reference Arguelles and Rich1991, 448). In other cases, sexual minorities are suspected of forming ties with sympathetic international actors, such as international organizations, the presence of which the state views as undesirable (Young Reference Young1981, chap. 1).Footnote 7

Furthermore, identity-based targeting can fulfill another function of selective violence: creating a ‘perception of credible selection’, which signals to potential defectors that the state has sufficient monitoring capabilities and resolve to pinpoint individuals for their actions (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, 190, emphasis in original). Revolutionary governments seeking to suppress potential counterrevolution face the same incentive to demonstrate their ability to selectively punish to deter defection as wartime actors. Demonstrating the capacity to selectively punish prior to widespread defection should deter potential collaborators by signaling the high risks involved. However, this motivation again arises even when there are no actual defectors to punish. When membership in an identity group is relatively ‘invisible’, accurately identifying members indicates that the state has the ability to selectively target even when there are no anti-regime collaborators yet. Though the primary means of demonstrating this ability with identity-based violence is through campaigns against ‘invisible’ minority groups, the communicative purpose of repression is also borne out in repression against high-profile figures from the targeted identity group. Another form of communicating this ability is through ‘branding’ targeted individuals as sexual minorities, such as labeling them with pink triangles in Nazi Germany, parading them in public with identifying inscriptions in communist Yugoslavia or forcing them to wear identifying clothes in Cuba (Haeberle Reference Haeberle1981; Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 80). The dual purpose behind identity-based repression against sexual minorities – deterrent and communicative – is demonstrated in the Soviet Union’s homophobic repression. In 1933, G.G. Iagoda, head of the Soviet intelligence service and secret police, proposed repressive legal measures against homosexuals to Stalin on the grounds that networks of homosexual groups would culminate into ‘outright espionage cells […] for plainly counterrevolutionary aims’; Stalin responded in an ‘enthusiastic and draconian fashion to Iagoda’s initiative’ (Healy Reference Healy2001, 184–6). More than broadly punishing homosexuals as potential subversives, the Stalinist regime made explicit efforts to single out high-profile intellectuals. For instance, informal peasant poet laureate Nikolai Klieuv was exiled to Siberia due to his homosexuality; Klieuv died while still in exile (Baer Reference Baer2015, 742). In short, early Soviet homophobic repression resulted from suspicion regarding the loyalty of sexual minorities and was designed to clearly signal the regime’s ability and willingness to punish them.

Despite these strategic imperatives, two important questions remain. First, how do revolutionaries come to perceive sexual minorities as unreliable? Sometimes previous experience can inform which identity groups states perceive as natural defectors; the Argentinian junta, for instance, included sexual minorities among their targets for ‘disappearance’ due to the history of leftist collective action of organizations such as the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (Ben and Insausti Reference Ben and Insausti2017). In most cases of homophobic repression, however, there is little pre-existing LGBT collective action that warrants an extreme state response.Footnote 8 Violent anti-LGBT repression in states as diverse as Afghanistan, Cambodia, China, Iran, Iraq, the Soviet Union, Uganda and Zimbabwe occurred without significant pre-repression LGBT collective action. Moreover, the threat perceptions against sexual minorities are often empirically unfounded, as when Castro’s Cuba erroneously assumed that homosexuals were aligned with counterrevolution and foreign imperialism (Young Reference Young1981, chap. 2). Revolutionaries likely suspect and target various groups as potential defectors, but this alone says little about why sexual minorities in particular are selected. Secondly, why select sexual minorities to demonstrate the ability to selectively target? While sexual minorities are relatively ‘invisible’, so are many other groups of people. Paramilitaries in Colombia, for instance, sometimes engage in ‘social cleansing’ violence, which includes extrajudicial killings of street children, prostitutes and drug dealers in addition to homosexuals (US Dept. of State 2003). Revolutionary governments may also target diverse social and identity groups, but the reasons for repression against sexual minorities as a particular identity group warrants examination beyond strategic incentives.Footnote 9

The ideological roots of revolutionary homophobia

Ideology helps answer these remaining questions and explains why revolutionary governments select sexual minorities for repression. In line with recent developments in the literature, ideology and strategy are treated here not as competing or mutually exclusive explanations for violence and repression (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014; Verdeja Reference Verdeja2012). Rather than contrasting ideology and pragmatism, we can approach ideologies ‘that frame events, opportunities, and perceptions of other actors’ as broader systems in which pragmatic and strategic actors operate (Verdeja Reference Verdeja2012, 316). Ideology, it is argued, shapes perceptions about sexual minorities and their reliability. Revolutionaries may have a strategic incentive to target ‘unreliable’ and ‘invisible’ groups, but it is ideology that leads these regimes to perceive sexual minorities as potentially threatening and to select them for punishment from the range of potential targets.

Revolutions are in part distinguished from other irregular transitions – including coups, assassinations and revolts – by ideological ambitions to completely transform social and political life (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2000, 170; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2013; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979). Revolutionary belief systems such as communism, fascism and Islamism are sometimes called exclusionary ideologies,Footnote 10 since social and political transformation provides an overriding justification for the exclusion and oppression of social groups that can motivate genocide against ‘real or perceived enemies of the new order’ (Harff Reference Harff2003, 57; Kim Reference Kim2018; Melson Reference Melson1992, 32). We theorize that exclusionary ideological systems lead to homophobic repression for similar reasons. Why should exclusionary revolutionaries be unified in portraying sexual minorities as enemies? One reason is that ideological revolutionaries are, by definition, revisionist actors. One indication that a regime is revisionist is that it harbors ‘a clear preference for radically recasting the shared standards that govern membership in the international community’; an example is a state ‘seeking to replace dynastic principles of legitimacy with nationalism’ (Lyall Reference Lyall2005, 18). Political theorists and political scientists from diverse intellectual backgrounds have argued that exclusionary ideologues, at least since WWI, are revisionist and have fought against existing liberal democratic legitimizing principles (Berman Reference Berman2003; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1989; Mozaffari Reference Mozaffari2017; Žižek Reference Žižek2012, introduction).Footnote 11 In opposition to ‘the autonomous individual with his concern for liberty and privacy’, one of the fundamental postulates of liberalism (Gray Reference Gray1995, 78), exclusionary ideologues treat individuals as belonging to immutable groups that may or may not fall within the legitimate political community represented by the state (Harff Reference Harff2003, 62; Straus Reference Straus2015, 11). Instead of representing individuals and individual rights, exclusionary ideologues posit that ethnic, religious or socioeconomic groups are the communities that lend states their legitimacy. Examples of this anti-individualist, revisionist thinking among exclusionary elites are available in the broader literature on identity-based violence. Elites in Nazi Germany, for instance, believed that ‘Jewish individualism’ was a threat to the cohesion of the German nation, a belief that served as one justification for the Holocaust (Koenigsberg Reference Koenigsberg2009, chap. 1).

Exclusionary revolutionaries are likely to associate sexual minorities with liberal individualism, and therefore to perceive them as untrustworthy actors naturally aligned with Western democracies and counterrevolutionary movements. Although this perception is sometimes a radical departure from reality – as already mentioned, Cuban homosexuals were associated with counterrevolution even though many were active participants in the revolution (Young Reference Young1981, chap. 2) – the perception that sexual identities are articulated as a result of liberalization is not without empirical support. Sociological studies have shown that LGBT movements grow in contexts of individualization and liberalization, a relationship that cannot be attributed to variables such as development or democracy; the central argument in this literature is that sex becomes divorced from collectivities like the family and becomes individualized, leading to the expression of sexual identity (Frank and Mceneaney Reference Frank and Mceneaney1999). Similarly, tolerance of homosexuals is positively associated with increases in liberal, postmaterialist values more generally (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003, 160). Evidence that revolutionaries have constructed sexual minorities in individualistic terms, and therefore as subversives who threaten collectivist goals, is found across ideological affinities. According to scholars of LGBT history, communist leaders harshly criminalized homosexuality, which they considered to be a pathological phenomenon resulting from liberal capitalist societies (Healy Reference Healy2001).

Other exclusionary ideologues similarly framed sexual minorities as threats to the collective wellbeing. An example is found in Tito’s Yugoslavia, which stressed ‘the importance of collective identity and citizenship (‘Yugoslavism’) above and beyond any individual identity such as ethnic, sexual, or gender’; in this context, there was ‘a “desirable” or “correct” way to be a citizen (in other words, Yugoslav) and an “undesirable” or “wrong” way to be (expressing anything outside the idealized nationality such as ethnic division or sexual diversity)’, a belief that was articulated in the years leading up to a period of anti-LGBT repression (Rhodes-Kublak Reference Rhodes-Kublak2015, 92, 94). Such exclusionary anti-LGBT rhetoric in the Balkans contrasts ethnic identity with ‘Western “ailments” such as homosexuality’ (Trost and Slootmaeckers Reference Trost and Slootmaecker2015, 154). Even during an early election campaign, Hitler responded to a request for the official Nazi stance on homosexuality by exclaiming that the Nazi party places ‘[c]ommunal welfare before personal welfare’ (Quoted in Haeberle Reference Haeberle1981, 280). While not an actual state, Islamic State revolutionaries have contrasted their executions for homosexuality with the ‘sexual revolution’ in the West and its attendant decline of the ‘nuclear family’ and its ‘morals’ (Islamic State 2015, 42).Footnote 12 Despite the marked differences among different exclusionary revolutionaries, they are unified in pitting sexual minorities – perceived as liberal, Western and individualistic – against the collective identities their states claim to represent.

From the arguments outlined above, we can derive two hypotheses regarding homophobic repression. First, it is hypothesized that revolutionary governments are more likely than non-revolutionaries to repress sexual minorities. Revolutionary governments face pronounced threats from potential counterrevolutionaries and international intervention. Staving off these threats means that revolutionaries have an incentive to pre-emptively target individuals they perceive as unreliable, and to clearly demonstrate their ability to selectively punish defectors even before defections have occurred. Under these conditions, revolutionary regimes are, on average, more likely to repress sexual minorities due to their relative ‘invisibility’, which allows them to demonstrate an ability to selectively target. Without these strategic concerns, there is little reason for revolutionaries to accept the high costs of monitoring, identifying and punishing sexual minorities who are unable to violently contest the state.

Secondly, it is expected that revolutionary regimes that adhere to exclusionary ideologies are more likely to repress sexual minorities. ‘Invisibility’ alone is insufficient to explain homophobic repression, because many group identities are easily concealed, and strategic calculations fail to explain why sexual minorities are perceived as potential defectors. Exclusionary ideologies that many revolutionaries hold – such as communism, fascism and Islamism – account for the selection of sexual minorities as specific targets for repression. All of these ideologies are revisionist in the sense that they challenge liberal belief in the individual as the foundation for state legitimacy, with collective categories (for example, class, ethnic or religious) as the proper political community represented by the state. Since sexual freedoms are associated with social individuation, exclusionary revolutionaries are liable to assume that sexual minorities are aligned with Western liberalism and thus represent threats to their homogenizing projects. In short, we expect that revolutionary governments that adhere to exclusionary ideologies, which are mostly restricted to revolutionary governments (Harff Reference Harff2003, 57–9, 63; Kim Reference Kim2018), are most likely to perpetrate homophobic repression.

Hypothesis 1: Revolutionary governments are more likely than non-revolutionary governments to repress sexual minorities.

Hypothesis 2: Revolutionary governments with exclusionary ideologies are more likely than those without exclusionary ideologies to repress sexual minorities.

Data and Method

Statistical tests of these hypotheses are performed using new and original data on state repression of sexual minorities. The unit of analysis is the country-year, with the data ranging from 1946 to 2003. There are various ways in which the state can repress sexual minorities. However, this article concentrates on execution, torture, extrajudicial killings, imprisonment, disappearance and displacement. Two considerations inform this decision.

First, these are the most visible and severe forms of repression. It is likely that less extreme forms of repression are more common and therefore infrequently reported, meaning that analyzing these phenomena could lead to biased estimates.Footnote 13 With regard to human rights generally, the expansion of acts considered human rights violations can give the false impression that human rights are being violated with increasing frequency (Fariss Reference Fariss2014). If less severe human rights violations against sexual minorities have only been reported in recent years, then including them in the analysis could similarly lead to erroneous conclusions. This is likely when exploring types of human rights violations, such as repression of sexual minorities, which may not have traditionally received priority attention from human rights organizations.

Secondly, there is a precedent for using these indicators. Cingranelli and Richards (Reference Cingranelli and Richards1999, Reference Cingranelli and Richards2010) use them to create their widely used dataset of physical integrity rights violations. In essence, this article examines a subset of physical integrity rights violations against a particular identity group, LGBT people, which ranges from arbitrary imprisonment to genocidal behaviors that designate the LGBT community as extinguishable. An additional category for displacement is included here to recognize when states deport or otherwise physically remove individuals from the state based on their sexual orientation, since this action is analogous to ethnic cleansing.Footnote 14

Repression onset, the dependent variable, is coded dichotomously in each country-year whenever the state initiates executions, tortures, extrajudicial killings, imprisonments, disappearances or displacements against sexual minorities. While most episodes of homophobic repression are short-lived, some persist for decades. Coding only the onset of periods of repression ensures that these outliers are not driving the results.Footnote 15 As shown in the online appendix, the following results are nonetheless robust to coding every year of state repression; in fact, they provide much stronger support for the hypotheses than coding only the onset, and thus the results presented here underestimate the impact of revolutionary government on homophobic repression. Ideally, a variable measuring the intensity of this repression would be created, but data limitations inhibit using a more complex measure. In other words, the extent of repression remains largely unknown even when the occurrence of repression of sexual minorities is documented.

Both primary and secondary sources were used to gather country-year information on these crimes against sexual minorities. Most frequently consulted were books and articles on individual state practices and the LGBT history, rights and community within those states. There is a sizeable literature on LGBT rights across numerous regions and time periods from various disciplines in the social sciences and humanities. Many of these are detailed histories based on primary source documents by scholars with in-depth contextual knowledge. These works have remained a hitherto untapped resource in the nomothetic literature on LGBT rights and repression. Encyclopedias of LGBT rights with entries for every country were consulted to insure against searching out only information that would corroborate the theory.Footnote 16 Academic search engines such as Factiva and LexisNexis were then used to seek out primary source information on LGBT rights in each country.Footnote 17 Documents from prominent NGOs – Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association in particular – provided indispensable material on the status of LGBT rights worldwide. Several truth and reconciliation commissions recounted episodes of state-led homophobic violence. Research was conducted primarily using English-language sources, but some Spanish and Portuguese sources were consulted as well.Footnote 18 An observation in the dataset is coded 1 when at least two sources are in agreement that homophobic repression was initiated in the state-year. The online appendix further discusses the data collection and coding process.

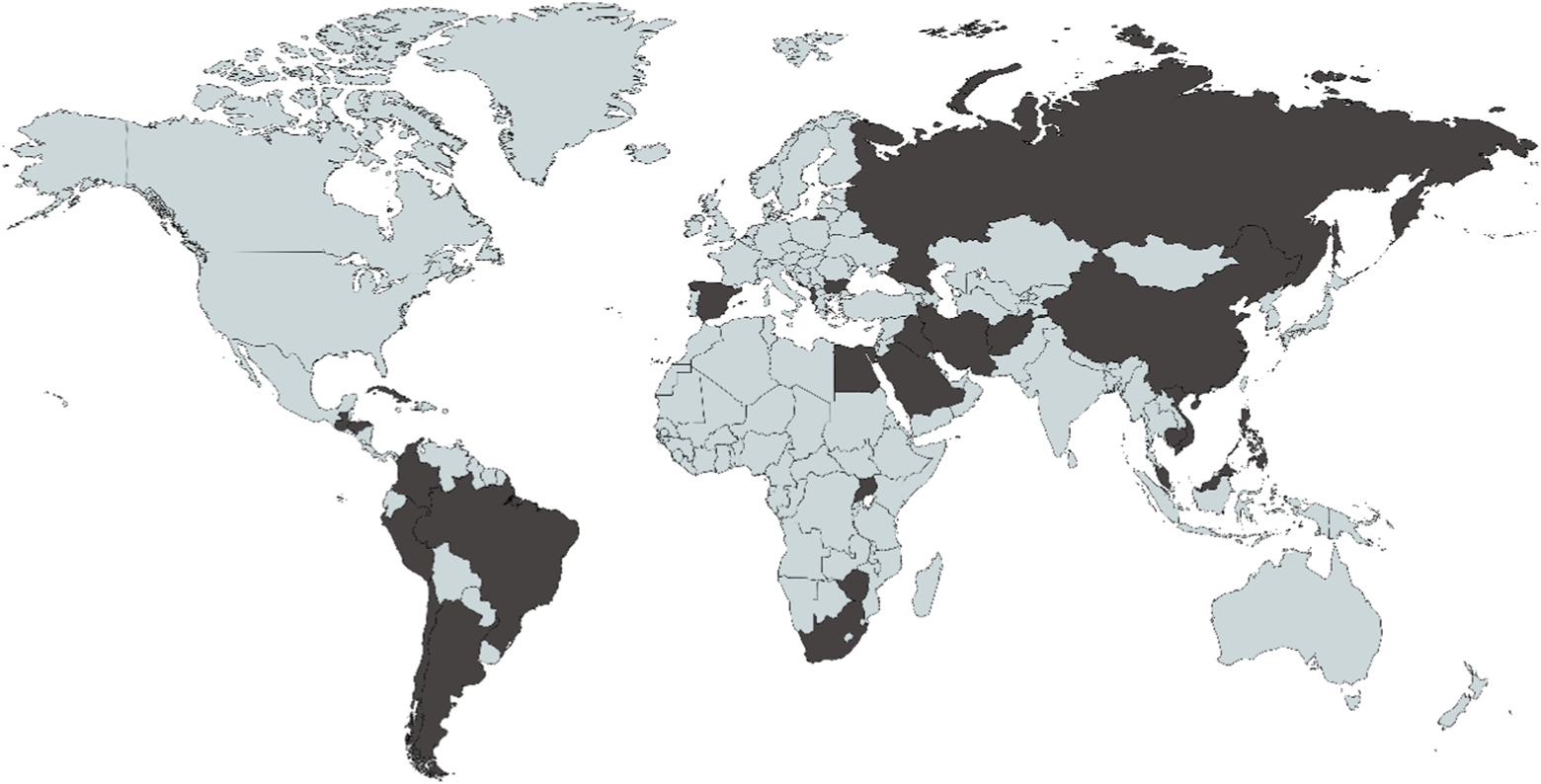

In total, there are thirty onsets of homophobic repression across twenty-eight states (see Figure 1).Footnote 19 The figure displays a wide geographical distribution of the dependent variable: evidence of homophobic repression was gathered in multiple countries in every populated continent apart from North America and Oceania. Repression against sexual minorities is therefore not restricted to a few regions, such as the Middle East and Africa, that share similar historical contexts that might shape their propensity for homophobic violence. Another concern is temporal rather than spatial: it is likely that interest in tracking anti-LGBT repression has increased over time along with the monitoring abilities necessary to uncover where such repression occurs. It is thus reasonable to suspect that the data include false negatives when extending further back in time, when homophobic repression occurred but went undocumented. However, the historically limited interest in, and capability of monitoring, homophobic repression should underestimate the effect revolutions have on homophobic repression, since it has long been observed that revolutionary governments are especially secretive (Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 78). Empirically, with the exception of the 1950s, each decade included in the analysis witnessed at least two onsets of anti-LGBT repression.Footnote 20

Figure 1. States featuring homophobic repression, 1946–2003.

One potential difficulty in coding the repression of sexual minorities is determining whether the victims were targeted specifically due to their sexual orientation. In most cases, state officials are quite explicit in singling out the LGBT community for attack. This explicitness follows from the logic of selective punishment, since states cannot effectively communicate an ability to selectively punish if their repression is ambiguous. At the same time, instances of repression are not ruled out if sexual minorities are targeted because they are perceived as likely members of another group deserving of punishment (for example, the educated). Targeted groups are often associated with segments of society that are widely considered malignant. But we would no sooner disregard violence against sexual minorities as identity-based violence for this reason than we would disregard the Holocaust as genocide simply because Jews were ‘othered’ in part by associating them with communism. Nevertheless, there is still ambiguity as to which cases should be counted as homophobic repression. As mentioned previously, homophobic repression differs from ‘selective violence’ more generally in that victims are targeted based on identity and not on actions such as defecting from the regime (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, chap. 7). For homophobic repression to have occurred, it is necessary for sexual minorities to have been targeted as an identity group. The novel and active implementation of the death penalty for homosexuality or sodomy is coded positively as repression since it accords with this criterion, although this does not include governments that retain a previously established death penalty since this may reflect legal path dependence rather than repression; many states that retain these laws do so for historical reasons and do not actively employ them or repress sexual minorities (Asal, Sommer and Harwood Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Carroll and Itaborahy Reference Carroll and Itaborahy2015). One potential concern is that this coding decision will disproportionately affect Islamic states, since sharia-based law includes stipulations against sodomy. However, the implementation of the death penalty results from the state’s particular interpretation of sharia. Although some states – post-Taliban Afghanistan, Pakistan and Qatar – have codified the death penalty for same-sex activity due to sharia, they are not known to implement this punishment (Carroll and Itaborahy Reference Carroll and Itaborahy2015, 28–29). These cases are not counted as instances of repression. Similarly, imprisonments based on legally sanctioned behavior such as sodomy are not coded as instances of repression. The causes of this criminalization are well examined elsewhere (Asal, Sommer and Harwood Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Hildebrandt Reference Hildebrandt2015).Footnote 21 Rather, this article focuses on instances where individuals are arbitrarily imprisoned simply for being sexual minorities.

The primary independent variable of interest is a measure of whether a given regime is a revolutionary government, using yearly data on revolutionary governments compiled by Jeff Colgan (Reference Colgan2012). Revolutionary government is defined here as a government ‘that transforms the existing social, political, and economic relationships of the state by overthrowing or rejecting the principal existing institutions of society’ (Colgan Reference Colgan2012, 452). States are coded 1 on the Revolutionary Government variable when meeting these criteria until there is turnover to a non-revolutionary leader (that is, one who did not participate in the original revolution). These data and the coding scheme used to derive them have been described extensively elsewhere (Colgan Reference Colgan2012; Colgan Reference Colgan2013). Testing Hypothesis 2 requires a measure of exclusionary ideology. In her study of genocide and politicide, Harff (Reference Harff2003, 63) lists several ideologies that fit under the exclusionary label. These include strict variants of Marxist-Leninism, Islamic states governed by sharia, rigid anticommunist doctrines, ethnonationalism and strict secular nationalism. Regimes adhering to these ideologies are coded 1 on the Exclusionary Ideology variable, combining previous efforts at coding exclusionary ideologies and original research on state ideologies (Harff Reference Harff2003; Kim Reference Kim2018).

Several control variables that could confound the relationship between revolutionary government and homophobic repression are included in the following analyses. Two important ones are British legacy and Islamic tradition. While cross-national physical integrity rights violations against sexual minorities have not been examined, these two variables have been highlighted as determinants of the criminalization of homosexual acts (Asal, Sommer and Harwood Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Hildebrandt Reference Hildebrandt2015). In these articles, the criminalization of homosexuality carries over from British common law or is retained as part of sharia law. It is necessary to control for these factors to ensure that LGBT repression is not simply a reflection of legal tradition. Therefore, the analysis includes two proxy measures for these variables. The first, British Legacy, is a binary indicator for whether the state has a British colonial history. The second, Percent Muslim, is a measure of the Muslim percentage of the population. Both variables are drawn from the original revolutionary governments dataset (Colgan Reference Colgan2012). A positive value for either of these variables would suggest that physical integrity rights violations are caused in part by the same underlying factors as anti-gay legislation.

Since previous studies have consistently shown that states are more likely to commit atrocities during wartime, the following analysis also must control for ongoing civil war (Straus Reference Straus2015; Valentino Reference Valentino2004; Valentino, Huth and Balch-Lindsay Reference Valentino, Huth and Balch-Lindsay2004). Using the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Armed Conflict Dataset, a binary measure for whether the state is engaged in a civil war that reaches at least twenty-five battle deaths during a given state-year is constructed. UCDP’s binary measure of Interstate War is similarly included, given the repeated finding that armed conflict is generally associated with internal atrocities (Kim Reference Kim2018; Krain Reference Krain1997). To account for the potentially pacifying effects of democracy, as found in the repression and genocide literatures discussed above, a dummy variable for Democracy is created by coding country-years with a Polity IV score of 7 or higher as democracies. A standard set of continuous control variables for log Population and log GDP per Capita are taken from Fearon and Laitin’s study of insurgency (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003). Lastly, several time variables are included. A cubic polynomial counting time since the last onset of homophobic repression, along with its square and cube, is included to account for possible temporal dependence in the data (Carter and Signorino Reference Carter and Signorino2010). To further account for potential temporal variation in homophobic repression, a series of dummy variables for each decade are included. Although they are omitted from the following figures – for presentation purposes, and since none reach statistical significance – all the models estimated below include these time variables.Footnote 22

Statistical Results

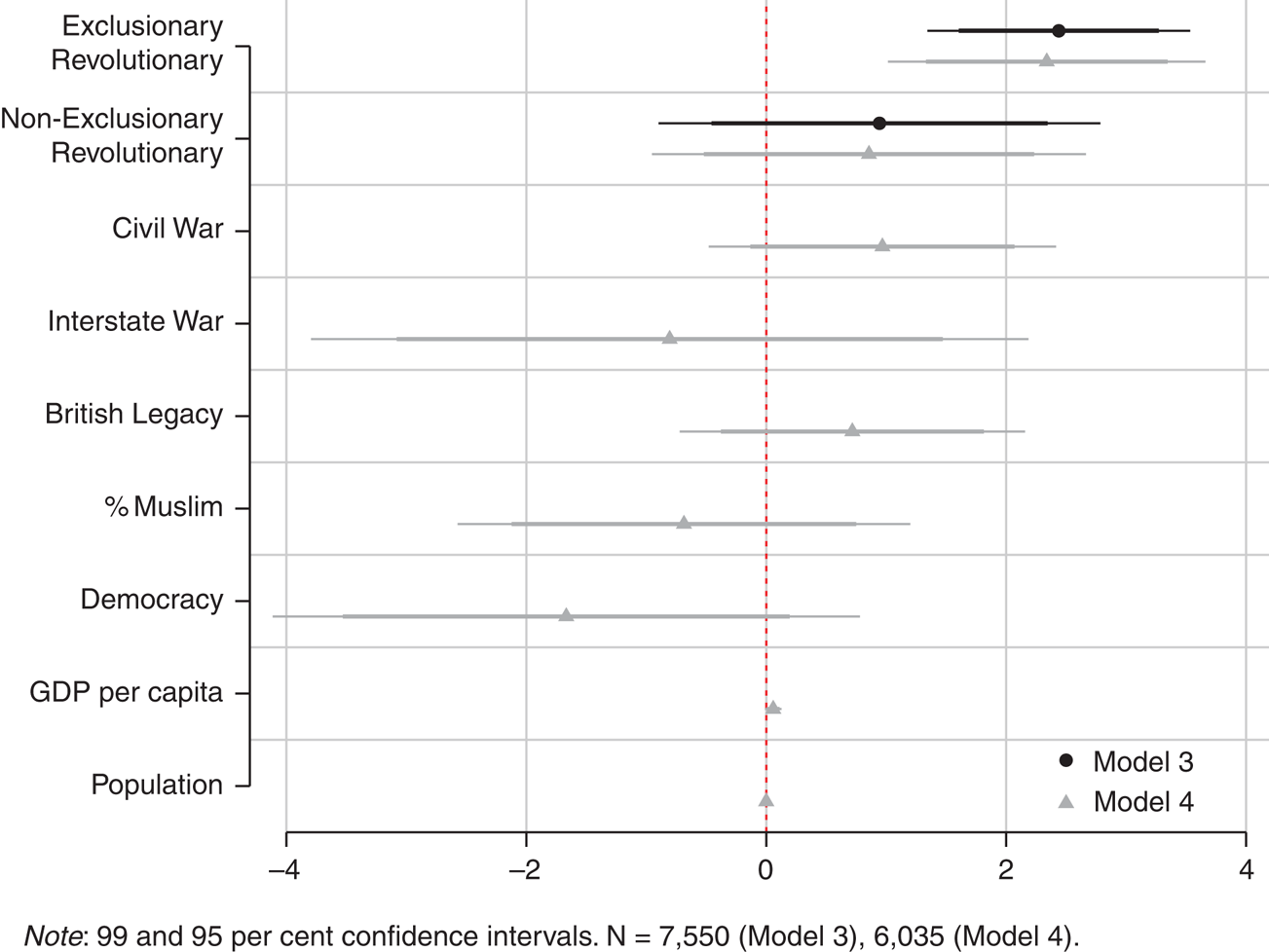

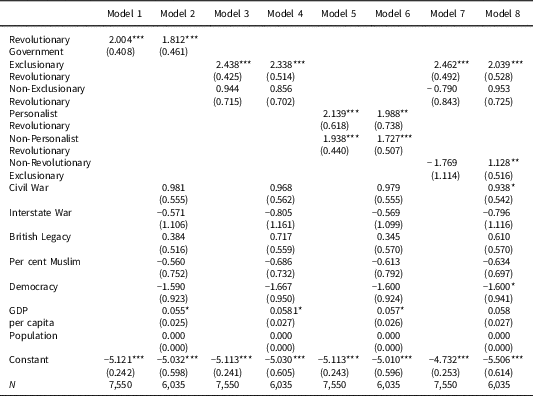

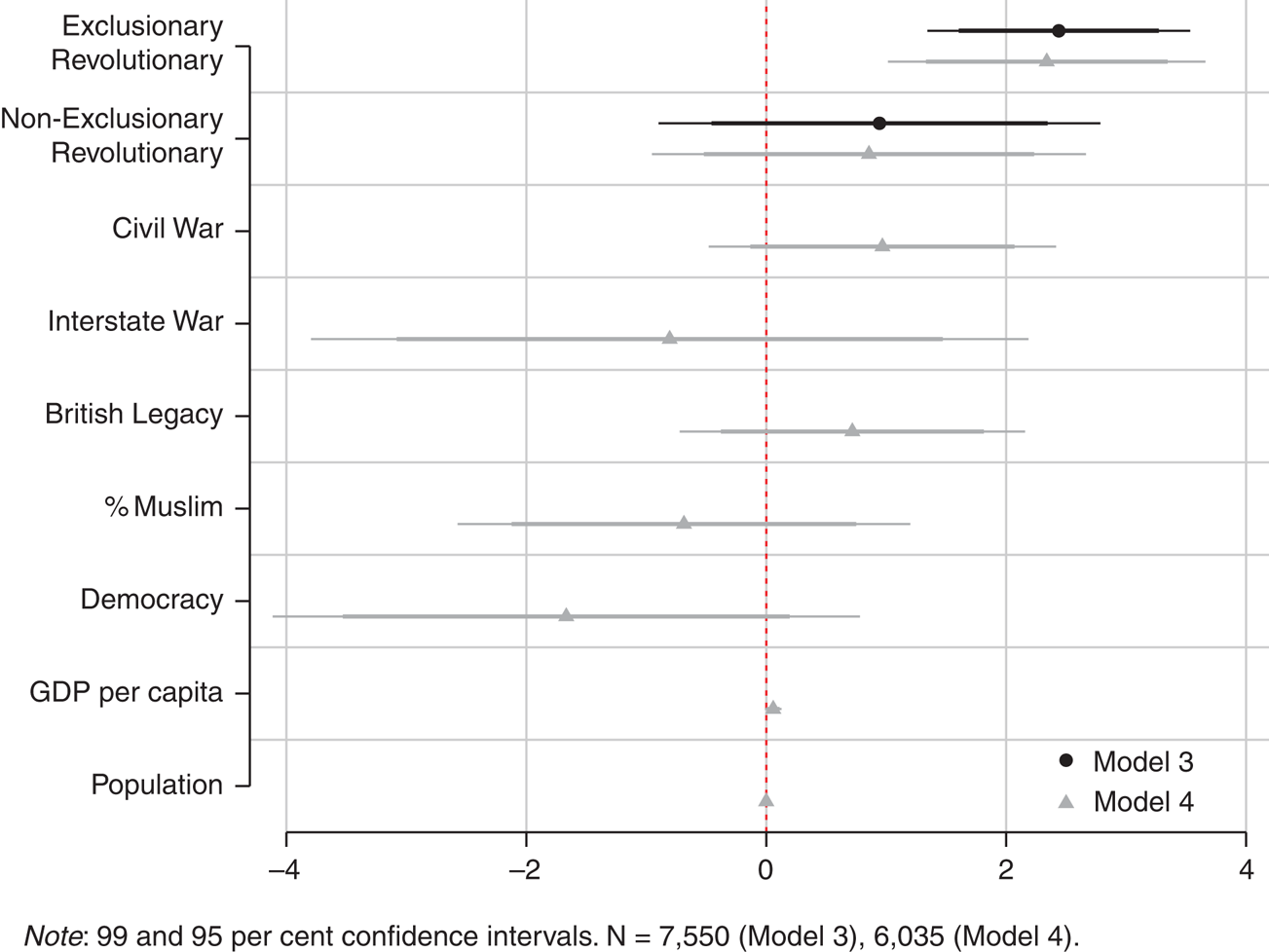

Since the dependent variable in this analysis is binary, the hypotheses can be tested using logistic regression. All the models below are estimated with standard errors clustered at the country level to account for the dependence of observations within state contexts. Since some political scientists recommend conveying statistical results graphically (Kastellec and Leoni Reference Kastellec and Leoni2007), Figures 2 through 5 present the results visually. Table 1 presents all the models to allow greater scrutiny of the relationships among coefficient estimates within and across models. Figure 2 presents the results of testing the primary hypothesis that revolutionary government positively impacts the onset of homophobic repression. Each circle represents a coefficient estimate, and the confidence intervals are rendered at the 99 and 95 per cent levels; lines that do not cross the dashed line at x=0 are therefore statistically significant at the 1 and 5 per cent error levels, respectively. Model 1 regresses the onset of homophobic repression on revolutionary government and the time variables, and Model 2 adds the remaining control variables. Due to missing data, the number of observations for the full models is 6,035 (versus 7,550 for the reduced model); as discussed below, the results are robust to multiplying imputing missing values.

Figure 2. Revolutionary governments and homophobic repression.

Table 1. Regression results

Note: standard errors in parentheses. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

As predicted in Hypothesis 1, Revolutionary Government has a highly statistically significant effect on the onset of homophobic repression in both models. It is the only variable to reach statistical significance in the full model, and in both models it reaches the 1 per cent error level of significance. Notably, the competing explanations derived from the existing literature on anti-gay legislation find no support. Neither British colonial history nor the percent of the population that is Muslim approach conventional levels of statistical significance, which indicates that homophobic repression has underlying causes that are different from those for homophobic legislation. Surprisingly, neither Civil War nor Democracy reaches conventional levels of statistical significance, although their coefficient estimates are in the theoretically expected directions. In other words, there is little evidence that the major contributors to general repression also explain homophobic repression.

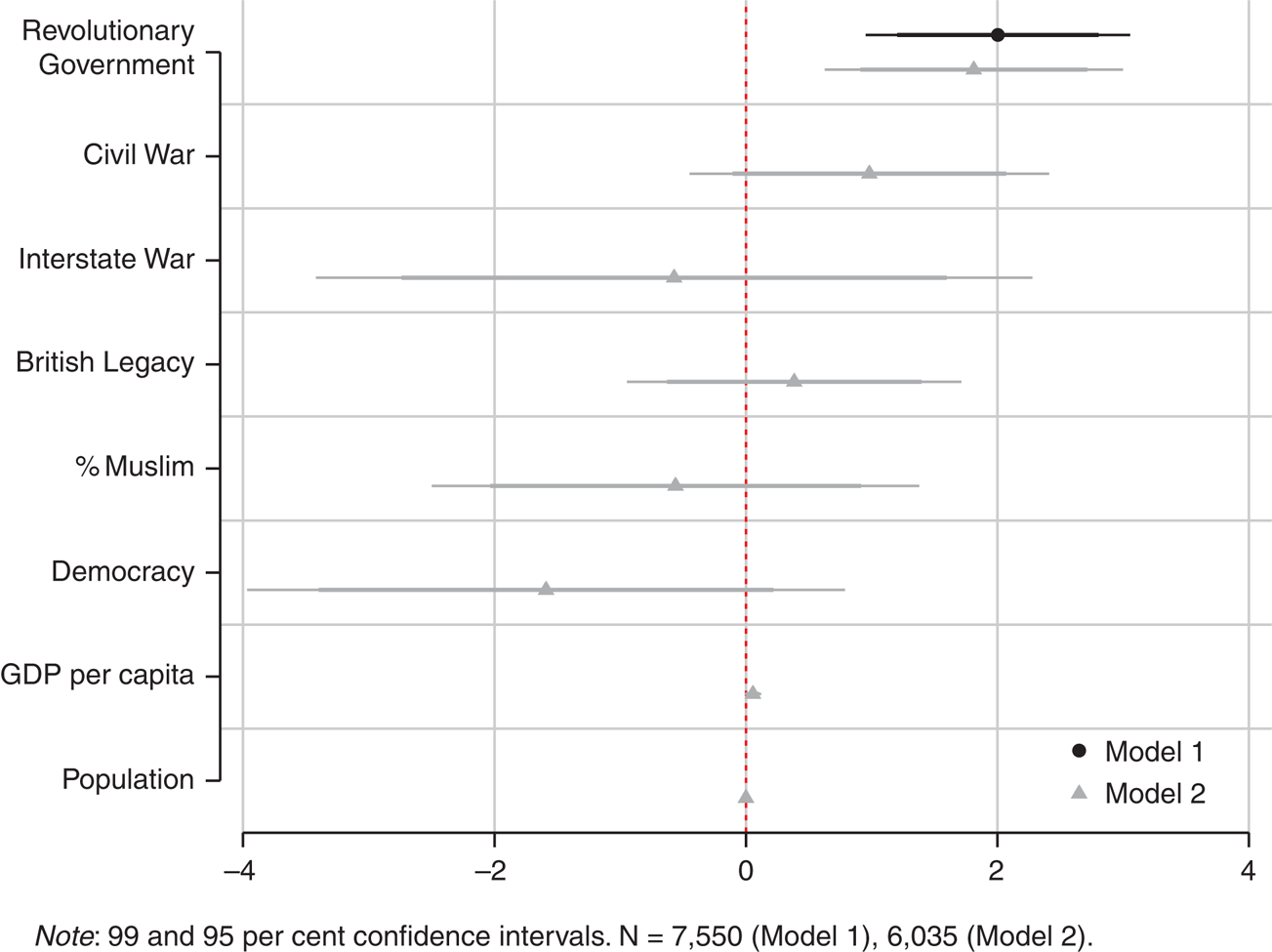

Testing Hypothesis 2 requires comparing the likelihood that revolutionary governments with exclusionary ideologies target sexual minorities more often than those that do not espouse such ideologies. Figure 3 presents the results with the dependent disaggregated into two mutually exclusive variables, one for exclusionary revolutionaries and one for non-exclusionary revolutionaries. Otherwise, the two models are identical to those in the second figure. As expected, there is a statistically significant effect for ideological revolutionaries but not for their non-ideological counterparts. This result holds across both models. In short, we can conclude that exclusionary revolutionaries are more likely than non-exclusionary revolutionaries to repress sexual minorities. Although the post-revolution period provides incentives to selectively punish, this incentive is insufficient for revolutionaries to select sexual minorities as their target. This finding conforms to a growing body of literature emphasizing that strategic and ideological factors interact in producing mass violence (Gutierrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2014). Strategic incentives certainly matter, for otherwise revolutionary governments would have no motivation to absorb the steep costs of monitoring, identifying and punishing non-threatening minorities. Without an exclusionary ideology that helps frame sexual minorities as appropriate targets, however, even states with incentives to selectively target ‘unreliable’ or ‘invisible’ groups are unlikely to select sexual minorities for repression.

Figure 3. Exclusionary and non-exclusionary revolutionaries and homophobic repression.

Robustness checks

Several additional tests are conducted to ensure the robustness of these results. First, an alternative argument is that revolutions select for particularly violent leaders who are more likely to engage in various forms of political violence (Colgan Reference Colgan2013; Kim Reference Kim2018). We therefore decompose revolutionary governments into two types – personalist and non-personalist – using pre-existing data on regime type (Geddes, Wright and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2004). Although we cannot isolate the effects of revolutionary leadership, since by definition all revolutionary governments have revolutionary leaders, we can test the leadership mechanism by comparing personalist and non-personalist revolutionaries. If risk-averse or belligerent leadership is the mechanism leading from revolution to homophobic repression, then personalist revolutionaries should be more likely to engage in repression because their leaders are unconstrained in their use of violence. Personalist revolutionaries have been found to initiate interstate disputes more frequently for this reason (Colgan and Weeks Reference Colgan and Weeks2015). However, the results presented in Figure 4 cast doubt on this mechanism when applied to anti-LGBT repression. In Models 5 and 6, both personalist and non-personalist revolutionary government are statistically significant at the 1 per cent error level. This finding indicates that revolutionary homophobia cannot be attributed to leader selection, since revolutionaries engage in repression against sexual minorities whether their leaders are constrained or not.

Figure 4. Personalist and non-personalist revolutionary governments and homophobic repression.

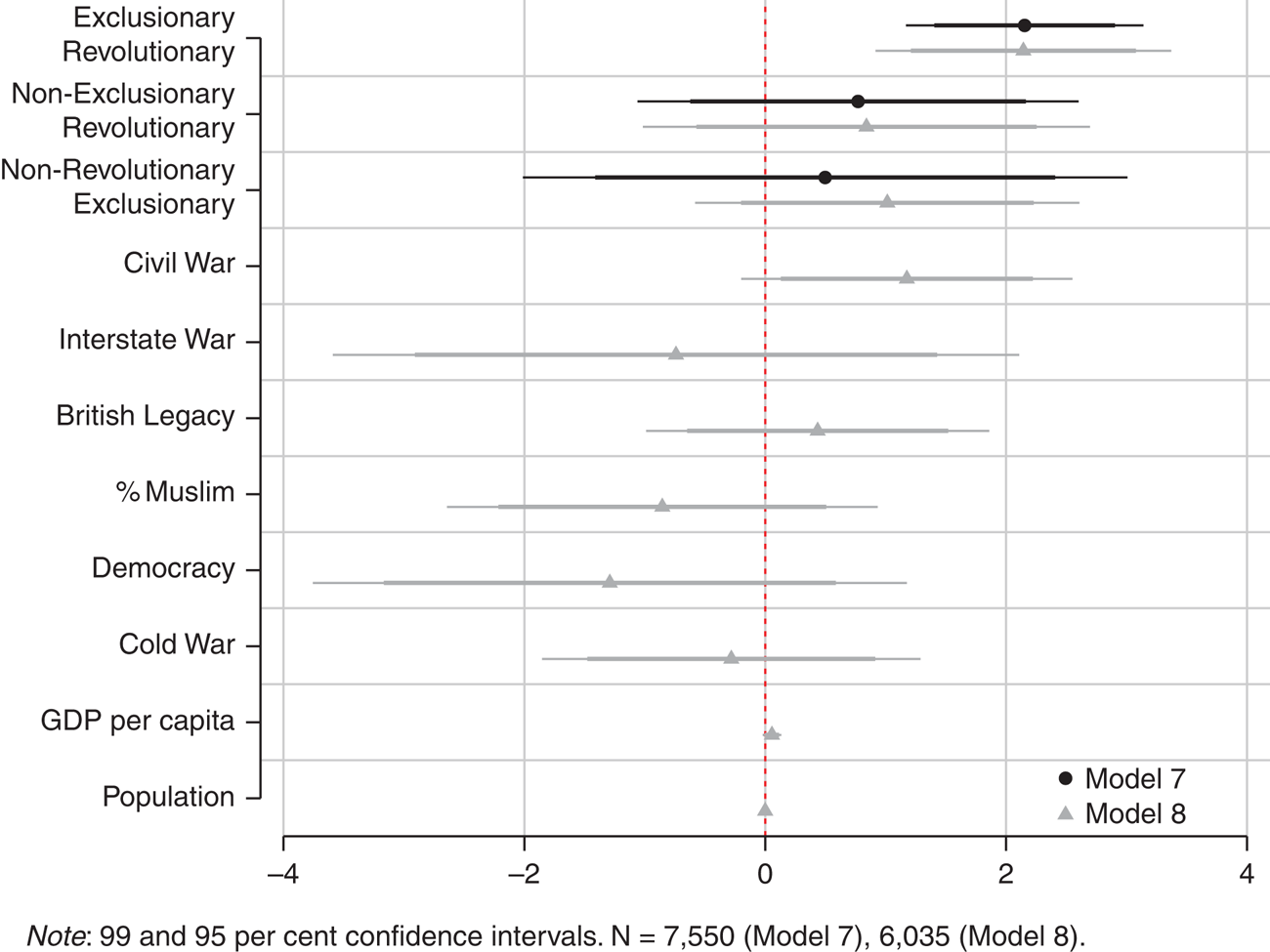

Secondly, another possibility is that ideology is the sole driving force behind anti-LGBT repression, and that the strategic incentives unique to revolutionary governments do not influence state decisions to repress. After all, only exclusionary revolutionary governments are found to have a statistically significant effect on homophobic repression. Testing this possibility requires examining the effect that exclusionary ideology has independent of revolution. Models 7 and 8 include a new independent variable for non-revolutionary exclusionary governments. Although most states with exclusionary ideologies are also revolutionary, several regimes are exceptions to this trend. Harff (Reference Harff2003) lists several exclusionary regimes that are not coded as revolutionary governments, including Bhutan, Serbia, Turkey, the German Democratic Republic, South Africa under apartheid and Taiwan under the military regime; using this scholar’s coding criteria for exclusionary ideologies, it is possible to create a variable for non-revolutionary exclusionary regimes. Yet, as demonstrated in Figure 5, this variable is statistically insignificant in the minimum specification and significant only at the 5 per cent error level in the full model; non-revolutionary exclusionary is insignificant in the full model when omitting the other two revolutionary government variables. Exclusionary ideology is a necessary feature for revolutionary governments to perpetrate homophobic repression, but these ideologies cannot account for the relationship outside the revolutionary contexts that incentivize these atrocities. Additionally, Model 8 reveals that civil war impacts homophobic repression in some model specifications. Confirmation that civil war has some effect on anti-gay repression provides modest additional support for the theory. If revolutionary governments target sexual minorities to selectively punish, then we should also find that states are generally more likely to repress sexual minorities during civil war. Political actors, after all, have a strong incentive to demonstrate their capacity to selectively target during civil war (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006). Post-revolutionary instability is an alternative condition under which such selective violence is strategically useful.Footnote 23

Figure 5. Effects of non-revolutionary exclusionary ideology on homophobic repression.

Due to space considerations, the results from the remaining additional tests are placed in the online appendix. Thirdly, an alternative binary dependent variable coded 1 for the incidence of homophobic repression, instead of its onset, is used. As mentioned previously, this substantially increases the size of the coefficient estimates for Revolutionary Government due to the inflation of positive values on the dependent variable. Fourthly, additional control variables are added to the base models shown above. Perhaps most relevant, taken from the revolutionary government dataset (Colgan Reference Colgan2012), is a binary variable for Irregular Transition, since the positive effect of revolutionary government could be an artifact of irregular transitions generally. Having been established through force, these regimes may be predisposed to extralegal violence including the subset directed against sexual minorities. Other variables that could account for homophobic repression, such as other authoritarian regimes types, are also added. Fifthly, Firth’s (Reference Firth1993) penalized likelihood logit model is used in place of logistic regression to insure against biased coefficient estimates due to the small number of positive values on the dependent variable. Sixthly, jackknife clustered standard errors are used to further ensure that the results are not driven by outliers. This approach repeatedly estimates coefficient values while omitting one state-level cluster of observations for each iteration. Seventhly, multiple imputation is used to fill in missing values on the covariates and to thereby avoid listwise deletion of observations. This check is imperative, given that estimating the full models above listwise deletes 1,000 observations due to missing values on the GDP, Percent Muslim and Population variables. In each case, the results presented in the main analysis hold and in some cases are strengthened after applying these robustness checks.

Repression of Sexual Minorities in Revolutionary Cuba

Do the posited causal mechanisms operate in important cases of homophobic repression? Cross-national statistical analysis is well suited to estimating causal effects across cases, but they are often silent on the mechanisms through which the relationships they identify are realized. For this reason, this section turns to process tracing, which involves sequentially tracking the process leading from independent to dependent variables within cases (Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2014). Since the results from the statistical analysis are supportive and robust, this section follows best practices in mixed-methods research by selecting a case well predicted by the statistical models to investigate the causal mechanisms (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005). As a revolutionary government that carried out extensive homophobic repression, Cuba is a satisfactory case for further examination. While other cases of homophobic repression follow the same mechanisms,Footnote 24 Cuba is one of the few cases for which there is sufficient qualitative information on homophobic repression to explore the mechanisms leading to its occurrence in sufficient depth.

Similar to most revolutionary governments, Cuba’s revolutionary leaders were preoccupied with staving off instability following the revolutionary transition in 1959. During its first year, the government diverted ‘approximately $100 million for military purchases to guarantee the regime’s survival from hostile internal and external forces’ (Morley Reference Morley1987, 76). Such hostile forces included ‘a formidable resistance movement’ that began ‘conspiratorial activities’ against the government’ and ‘American covert operations […] to assassinate revolutionary leaders’ Morley Reference Morley1987, 94, 97). It was in this context that a period of homophobic repression was initiated.

Repression against LGBT people cannot be attributed to fears of collective action or to pre-existing repression, since ‘Cuban gays never experienced […] gay community’ and sexual minorities, while sometimes facing social stigma, lived lives ‘free of interference by the state’ (Young Reference Young1981, 4–6). The earliest persecution of sexual minorities was the 1961 ‘Night of the Three P’s’,Footnote 25 which included a ‘selectiva (selective)’ raid where ‘men accused of engaging in homosexual activity’ were abducted from their homes, sent to prison, and dressed in uniforms embroidered with the letter P (Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 79–80). Some evidence suggests that the Cuban leadership viewed homosexuality as subversive, with Fidel Castro perceiving it as ‘a cabal, perhaps, a conspiracy’ (Young Reference Young1981, 21). Homosexuals soon found themselves ‘implicated by default in counterrevolutionary activities’, a perception of the revolutionary elite that was completely unfounded until the CIA enlisted a homosexual student leader to attempt to assassinate Castro in 1966 (Arguelles and Rich Reference Arguelles and Rich1991, 446–7). Repression was already well underway by 1965, however, when a nationwide campaign against sexual minorities was conducted; this included the establishment of the Military Unit for the Increase of Production, a system of rehabilitation camps that those designated for homosexuals (Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 80–1). In the traditional prison system, homosexuals ‘were confined to two of the worst wards. […] Gays were not treated like human beings’ (Arenas Reference Arenas1993, 180–1). Since this period of repression occurred only briefly after the revolution, it is difficult to attribute this campaign to longstanding, pre-existing cultural norms such as ‘machismo’.Footnote 26

Besides associating sexual minorities with counterrevolutionary elements, there is additional evidence that the repression served communicative purposes. The ‘officially sanctioned campaign of persecution against homosexuals’ was ‘directed especially against well-known intellectuals’ (Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 84), and the campaign against artists and writers became ‘an infamous symbol of the regime’s homophobia’ (Lumsden Reference Lumsden1996, 71). Moreover, many of the victims, including university students dismissed from classes for homosexuality, were ‘forced to make public confessions’ for their behavior (Ocasio Reference Ocasio2002, 80). When artists and intellectuals had their sexual practices ‘detailed in public’, they were ‘invariably linked with […] counterrevolutionary dispositions’ (Arguelles and Rich Reference Arguelles and Rich1991, 448). Such blatant attempts to showcase homophobic repression, and to clearly link homosexuality with counterrevolution, are consistent with the idea that the regime intended to demonstrate its ability to selectively target individuals for acting against the regime, which in a post-revolutionary society can serve as a deterrent against counterrevolutionary defections.

Finally, there is considerable evidence that ideology played a key role in the designation of sexual minorities as appropriate targets. Rather than being a product of ‘Cuban culture’, commentators closest to Cuba’s homophobic repression stress that the revolutionary government’s quest for ‘the total elimination of homosexuality’ was a product of ‘the external tradition of European Marxism’ (Young Reference Young1981, 15). Cuba closely followed the Soviet Union in raising ‘homosexuality to the level of a state security matter’, since the Cuban revolutionary leadership ‘was educated and trained through the network of [the international communist movement]’ (Young Reference Young1981, 16, 19). More than representing a counterrevolutionary threat to revolutionary leaders, sexual minorities were constructed as an individualistic threat to the homogenizing ambitions of revolutionary elites. Regime figures claimed that the imperative to ‘contain any form of deviance’ reflected in homophobic repression was necessary to ‘“preserve the monolithic ideological unity” of the Cuban people’ (Lumsden Reference Lumsden1996, 72).Footnote 27 Sexual minorities, in other words, were viewed as deviant, individualistic threats to an exclusionary homogenizing project.

Conclusion

State repression against sexual minorities is intrinsically puzzling. It requires accurately monitoring, identifying and punishing LGBT people, which imposes costs that existing research on political violence and repression suggest are only worth expending to deter direct challenges to the state or anti-regime collaboration during war (Davenport Reference Davenport2007a; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006). In contrast, this study maintains that states are willing to absorb these costs to preventively punish non-collaborating individuals who are unable to violently challenge the state when two conditions hold. First, when state elites perceive some groups as natural defectors, they are more likely to punish members of those groups preventively during times of crisis. Secondly, states are likely to target individuals whose group identities are relatively ‘invisible’, since accurately identifying them demonstrates the capacity to selectively punish, thereby signaling that defection can also be identified and punished. In addition to these incentives, states are only likely to target sexual minorities when elite ideologues construct them as unreliable or undesirable. Exclusionary ideologues – adherents of revisionist belief systems such as communism, fascism and Islamism – are predisposed to perceive sexual minorities as individualistic, Western and liberal threats to forging states based on collectivist foundations (for example, membership in ethnic, religious or socioeconomic communities).

In addition to the research on state violence and repression, this work seeks to contribute to two additional areas of scholarship. First, a growing body of literature is dedicated to the empirical, positivist study of gender in conflict and political violence (Reiter Reference Reiter2015). For instance, an impressive body of work explores why women participate in armed rebellion (Wood and Thomas Reference Wood and Thomas2017; Thomas and Bond Reference Thomas and Bond2015). Rape in civil war, which is perpetrated by both state and non-state actors, has similarly emerged as an important topic (Cohen Reference Cohen2016). Yet, while a few studies are dedicated to explaining the legalization of homosexuality (Asal, Sommer and Harwood Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Hildebrandt Reference Hildebrandt2015), there has been comparatively little research on human rights violations against sexual minorities. Case studies and policy reports have certainly been dedicated to this issue. However, this study represents the first cross-national, quantitative investigation of why LGBT people are sometimes targeted by governments. This issue retains its salience as some states, such as Iraq and Iran, persecute sexual minorities and as others, such as Nigeria and Uganda, move closer in this direction (Comstock Reference Comstock2016). This study serves as a first step toward better understanding anti-LGBT political violence.

Secondly, the topic of revolutionary violence has been frequently explored (see Goldstone Reference Goldstone2000). It is also a vibrant area of research that continues to provide insight into interstate conflict (Colgan Reference Colgan2013; Colgan and Weeks Reference Colgan and Weeks2015), mass killing (Kim Reference Kim2018) and genocide (Harff Reference Harff2003; Melson Reference Melson1992). While homophobic violence may appear to be a minor addition to this repertoire, it sheds light on important dynamics of revolutionary violence. Just as it elucidates why states repress harmless groups, it more specifically can help understand the puzzling excessiveness of revolutionary atrocities. Although LGBT people are unable to foment counterrevolutionary mobilization, repression of sexual minorities is strategically sensible if the intent is partly communicative. In other words, revolutionaries may select unthreatening targets to signal the ability to selectively target potential counterrevolutionaries. This finding also suggests promise for further integrating the LGBT rights literature into the study of political violence and human rights more broadly. Research from several disciplines has observed that communist, fascist and Islamist regimes often depict sexual minorities as legitimate targets of state violence (Haeberle Reference Haeberle1981; Healy Reference Healy2001; Hildebrandt Reference Hildebrandt2015; Mayer Reference Mayer2013). Yet the shared revolutionary motivations underlying homophobic repression in these states has been largely overlooked in the effort to understand the unique historical trajectories of homophobia within societies. Scholars interested in other forms of political violence, including violence by non-state actors, can benefit from further examination of the expansive literature on LGBT rights.

Supplementary Material

Replication data sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QNKFDL, and online appendices at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000480.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Matt DiGiuseppe, Brian Lai, Marina Zaloznaya, and the editors and anonymous reviewers at the British Journal of Political Science for their helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.