The question of whether powerful states' influence in international affairs is extended or tamed through international organizations (IOs) is central to the study of international cooperation. Powerful states are often identified as the prime movers in institutional design and are expected to design rules that facilitate their control over outcomes.Footnote 1 The increasing proliferation of international institutions and related forum-shopping opportunities would seem only to strengthen powerful states’ hand. If their preferred rules are not incorporated in a given IO, they can pursue favored policies through another. Yet upon close examination two puzzles emerge. Voting rules are the standard, and often the sole, indicator used to operationalize rules that allocate control across member states. Weighted voting rules like those used at multilateral development banks (MDBs) grant asymmetric control over outcomes to large, wealthy economies but the one-country-one-vote rule common to the United Nations system and other IOs built in its image does not. As Koremenos notes in her comprehensive analysis, “the findings are mixed with respect to how often power is reflected in institutional design,” and “power-based decision-making rules like weighted voting are less frequent than one might expect.”Footnote 2 Although powerful states occasionally shun IOs with egalitarian voting rules, more often they participate and provide the bulk of necessary financial support.

These puzzles call for a return to fundamental questions about power, control, and institutional design. Which rules allocate control in international organizations? How do power asymmetries among member states affect design? What constraints do powerful states encounter in their bid to design asymmetric control? How do these rules affect an IO's attractiveness within a regime complex? To answer these questions, we begin by expanding our knowledge of the rules menu used to allocate control in IOs. Building on work that theorizes the relationship between IO funding and multilateralism,Footnote 3 we conceptualize how different types of funding rules systematically allocate control across member states. Funding rules can permit or prohibit the practice of earmarking whereby a donor stipulates a particular country, program, or theme for its contribution. Under permissive earmark rules, translating financial power into control over outcomes is straightforward.

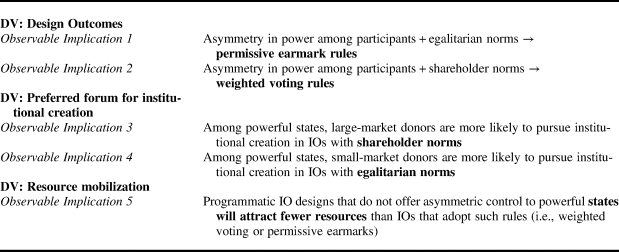

We develop a theoretical framework in which weighted voting rules and permissive earmark rules are treated as design substitutes from wealthy states’ perspective. The framework applies to IOs with a programmatic component, that is, those that involve operational activities that require funding. When developing states negotiate favorable voting rights, wealthy donor states protect their control over resource allocation through rules that permit earmarks. Permissive earmark rules act as a backstop for donor control even when developing states otherwise control governing-body decision making. This argument reaffirms the importance of asymmetric power as a causal force in institutional design, but with an important twist. The framework explicitly theorizes normative constraints on how powerful states design control and derives observable implications about when permissive earmark rules are used as a design substitute based on whether egalitarian norms—those emphasizing political and legal equality—or shareholder norms—those emphasizing influence commensurate with financial power—characterize the IO. In addition to explaining the design of control, the framework explains why powerful states rarely financially abandon IOs that employ one-country-one-vote: they maintain asymmetric control over resource allocation through funding rules.

We demonstrate our framework's utility across eighteen international climate finance institutions (ICFIs), a set of multilateral institutions established to finance efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change in developing countries. ICFIs are an important set of institutions in their own right; they are critical to addressing one of the most daunting and important challenges of our time and are growing in number and resources. They are also politically interesting and methodologically advantageous. ICFIs serve as contemporary sites of North-South contestation where the disagreement about whether “those who created the problem [of climate change] have a historical responsibility to repay their ‘climate debt’” plays out.Footnote 4 They also provide variation on the key intervening variable of interest, normative constraints, while allowing us to hold constant competing explanatory variables, like policy area competitiveness.Footnote 5

We find strong support for our substitution framework: in four of the five ICFIs with egalitarian norms that prohibit weighted voting, powerful states pursued permissive funding rules as a substitute. Of the thirteen ICFIs with shareholder norms, all incorporate weighted voting rules and prohibit strong earmarks by donors. In sum, when funding rules are taken into account as a design substitute, we see that asymmetric power translates into asymmetric control at seventeen of eighteen ICFIs. Whether voting or funding rules are used to achieve asymmetric control depends on whether egalitarian or shareholder norms characterize the IO. We evaluate the design process implied by our substitution framework with case studies of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and Green Climate Fund (GCF). In the GCF case, we use GCF board documents and secondary sources to trace how wealthy states pursued permissive earmark rules in attempts to compensate for developing states’ influence in board decision making. At the GEF, which employs weighted voting and prohibits earmarks, we identified whether permissive earmark rules were ever considered and by whom. To do so, we reviewed 463 official GEF documents and corresponded with GEF staff. Consistent with expectations, we found that donor states were content with the control accorded to them through formal voting and replenishment rules such that they did not pursue (and in some cases opposed) permissive earmark rules.

Our primary contributions are threefold. First, our theory advances the rational design research program by theorizing a logic of substitution under normative constraints. We employ this logic to explicate the posited relationship between two prominent rational design variables: asymmetric power and asymmetric control. We demonstrate that states with asymmetric power usually succeed in achieving asymmetric control in institutional design, but that norms constrain how it is obtained. We further elaborate how our substitution framework can be deployed to explain a broader range of design outcomes, including the incorporation of rules that provide flexibility, accountability mechanisms, and private actor access.

Second, our attention to funding rules exposes an important tool powerful states use to control IOs that is often omitted in studies of design. Taking permissive earmark rules into account is especially important since they are often incorporated in institutional designs that appear otherwise favorable to developing states.Footnote 6 In the context of ICFIs, when developing states win ostensibly important victories on voting rules, wealthy states have gone on to pursue permissive earmark rules, undercutting voting rules’ importance. ICFIs that fail to incorporate either voting or funding rules favorable to wealthy states risk losing funds relative to peer institutions that do. Our findings lend credence to Drezner's remark that “even instances in which weaker actors successfully exploited regime complexity appear, in retrospect, to have been ephemeral.”Footnote 7

Third, our empirical focus on climate finance in testing a general theory of international institutional design answers recent calls to “reverse the marginalization of global environmental politics in IR.”Footnote 8 Our empirical work advances knowledge of ICFI design, integrates new knowledge within the broader IR literature, and extends the scope of design theory to the area of international climate finance.Footnote 9

Control in International Institutional Design

Control in international organizations holds the promise of projecting national priorities on the international stage. At the macro-level, control determines who is positioned to guide the thematic direction of an IO, and at a micro-level, how its benefits are distributed across member states on a case-by-case basis. Reflecting its fundamental importance, the rational design (RD) volume highlighted “rules for controlling the institution” as a key dependent variable.Footnote 10 We adopt the RD definition of control, which centers on states’ relative influence in decision making, and can be allocated symmetrically or asymmetrically across member states.Footnote 11 The RD volume focused on “voting arrangements as one important and observable aspect of control”Footnote 12 and subsequent work has followed its precedent.Footnote 13 Weighted voting systems are understood to allocate control asymmetrically, typically based on economic indicators, and egalitarian voting systems allocate control symmetrically, with each state receiving one vote.Footnote 14

Control also receives attention from scholars of informal governance. In Stone's influential framework, IOs operate with “two sharply divergent sets of rules.”Footnote 15 Formal rules govern ordinary times and informal procedures facilitate powerful states’ temporary control during exceptional circumstances. Informal consultation practices between IO staff and government officials facilitate temporary control, which is made possible by powerful states’ ability to exercise outside options.Footnote 16 In competitive policy areas, states can credibly threaten to withhold funds from one IO in favor of another, improving their leverage.Footnote 17

When informal governance arguments emerged, they provided an important corrective to a rationalist literature disproportionately focused on the formal. Since then, improvement in our understanding of informal control practices has outpaced new knowledge about how formal rules allocate control across member states, which remains largely confined to voting. Expanding our knowledge about formal rules can facilitate better explanations of design and improve expectations about when informal rules are invoked. Without this, we might overestimate powerful states’ need to use informal mechanisms of influence, disregarding elements of design carefully crafted to protect their interests. But what other rules allocate control across actors? A complete answer is complex; substantive rules may explicitly favor certain members over others and vary across international agreements, rendering apples-to-apples comparisons difficult.Footnote 18 We thus confine ourselves to rules that might be usefully compared across IOs, offering three possibilities before focusing on a fourth: rules that govern (1) punishment; (2) executive head appointment; (3) replenishment; and (4) funding.

In addition to voting rules, Koremenos explicitly offers rules that allocate differential control over punishment as a proxy for control.Footnote 19 When international agreements delegate punishment to the UN Security Council (UNSC)—and only a few parties to the agreement are permanent members—it results in asymmetric control over punishment decisions. Rules governing IO executive head appointments often include similar requirements.Footnote 20 The UN Secretary-General is approved by the General Assembly and the UNSC, thus providing asymmetric control to permanent UNSC members. A third set of relevant rules involves replenishment thresholds, which determine eligibility to participate in replenishment negotiations, the standard process used to mobilize resources at MDBs. These negotiations often shape important issues including burden-sharing arrangements and programmatic priorities. When replenishment rules specify high contribution thresholds, few developing states participate.

There are limits to punishment, appointment, and replenishment rules as proxies for control. Relatively few agreements delegate enforcement and punishment at all, and any control stemming from a veto on appointments is less reliable in its impact than a de facto veto via weighted voting rules. The terms of replenishment rules are comparable across MDBs, but fundraising processes at other IOs are distinct. Still, these rules suggest caution: one should not infer symmetric control in design from the absence of weighted voting.

Drawing on extant literature,Footnote 21 we propose that rules governing funding provide a promising additional proxy of control for three reasons. First, like voting rules, funding rules are present at IOs across a wide range of issue areas, regions, and regimes. They are most relevant to IOs with a programmatic component, that is, those that involve operational activities requiring funds.Footnote 22 This includes IOs across a range of issue areas, including those engaged in economic development, global health, environment, human rights, and humanitarian assistance. Global and regional development banks, the specialized agencies and programs of the United Nations system and regional organizations, like the African Union, Arab League, and Organization of American States that engage in peacekeeping or election monitoring, fit the bill. The presence of a programmatic component in IO work provides a scope condition on funding rules’ importance to the allocation of control. IOs that are strictly regulatory or norm generating tend not to require significant funds. Yet funding rules are also significant at regulatory IOs that involve a programmatic component, often around centralized monitoring or enforcement, or capacity building to support compliance. For instance, the Non-Proliferation Treaty delegates a critical enforcement role to the International Atomic Energy Association and its inspections require financial contributions from member states. The Montreal Protocol is a regulatory agreement but its technical assistance program supports state compliance. Both are examples in which fulfilling regulatory tasks requires financial support, heightening funding rules’ importance.Footnote 23

Two other advantages of funding rules as a proxy are noteworthy. First, like voting rules, they vary in standard ways, which facilitates systematic study. Second, while far less studied than voting rules, within the IO and donor communities, funding rules are already regarded as critical for understanding control within IOs.Footnote 24 We now outline how funding rules affect control, laying the groundwork for our argument that from wealthy states’ perspective, permissive earmark rules provide a design substitute for weighted voting.

How Funding Rules Allocate Control

Delegation scholars recognize state decisions to provide or withhold funding to IOs as critical mechanisms to exert influence over IO bureaucracies.Footnote 25 Attention to funding rules reflects this fundamental insight. Funding rules dictate the financial relationship between a donor and an IO.Footnote 26 They influence how much money an organization receives, how reliably it is contributed, and importantly, which actors control resource distribution. The allocation of financial resources affects the range, types, and beneficiaries of IO activities. At ICFIs, control of resource allocation determines what types of projects receive funds (e.g., mitigation or adaptation), who the recipients are (e.g., public or private actors), and where they are located. Control of resource allocation affects these questions on a case-by-case basis, but also has a cumulative impact on an IO's trajectory over time. In this way, control over resource allocation is critical to guiding the goals and thematic direction the organization pursues.

Funding rules interact with voting rules to affect and alter states’ relative influence in collective decision making. Mandatory rules that require contributions as a legal obligation of membership reinforce voting rules’ allocation of control across member states. For example, the executive committee of the Montreal Protocol's Multilateral Fund employs one-country-one-vote rules and industrialized states are legally bound to contribute according to the UN scale of assessments. Mandatory funding rules reinforce the executive committee's control over resource allocation by obligating states to financially back its decisions.

All voluntary funding rules weaken governing body control over resource allocation because states can refrain from contributing without violating a legal obligation. But the extent to which it is weakened depends on whether rules permit or prohibit the practice of earmarking contributions. When IOs prohibit earmarks, donors cannot place conditions on how contributions are used, reinforcing voting rules’ allocation of control. Contributions are distributed according to multilateral decisions by the governing body. Importantly, if a governing body grants developing states strong representation and voting rights, they should exert substantial control over resource allocation. Yet IOs’ inability to enforce collective decisionsFootnote 27 also suggests a downside: if wealthy states are dissatisfied with majoritarian decisions they may not provide funds.

Rules that permit earmarks undermine voting rules’ importance. In fact, they challenge the assumption that resources are distributed according to collective or multilateral decisions at all.Footnote 28 Permissive earmark rules allow donors to unilaterally specify how their contributions are used. These contributions “are not under the purview of the board of the organization in question”Footnote 29 and thus allow for the transfer of control over resources to individual donors. Permissive earmark rules enhance donor control in two ways. The first is straightforward: when donor priorities are distinct from those articulated by governing bodies, a donor can earmark to assert control over how their contribution is used. The second method is subtler but no less important. The logic is similar to the enhanced influence that states with outside options exercise at IOs.Footnote 30 With permissive rules, donors have a credible alternative to governing-body control over resource allocation. Knowledge of this alternative increases the likelihood that the governing body will accommodate the donor's preferences in group decisions. This means the presence of permissive earmark rules is likely to enhance donor influence in governing-body decision making even if donors do not exercise the option to earmark. Importantly, donor states can determine resource allocation even when developing states enjoy strong representation on governing bodies and one-country-one-vote rules.

Between Asymmetric Power and Control: The Logic of Substitution Under Normative Constraints

When will institutional designs incorporate rules that allocate asymmetric control? Asymmetry of power among participants remains a prominent independent variable.Footnote 31 The expectation that asymmetric power among participants in the design process will produce rules that grant powerful states greater control over outcomes and weaker states less, “follows from an intuition about how the importance of an actor to an institution translates into greater control over how it operates.”Footnote 32 Related expectations stem from the regime complexity literature. If rules fail to allocate asymmetric control to powerful states, the powerful will “shop” for more favorable venues or create new institutions that better suit their needs.Footnote 33 Yet as we noted, many IOs are designed with one-country-one-vote rules and nevertheless enjoy financial support from wealthy states. This suggests three possibilities: (1) powerful states do not want control or do not view it as useful; (2) powerful states want control but are not able to obtain it and participate anyway; or (3) powerful states exert control through a different set of rules. We assume that because funding is central to IOs with a programmatic component, powerful states care about exercising control. Our theory is centered on the third possibility but recognizes normative constraints on how powerful states achieve control, as suggested by option two.

We begin by defining asymmetric power among participants as an independent variable and identify its sources in the context of programmatic IOs. In doing so, we make clear that such asymmetry is present in negotiations of nearly all programmatic IOs. If RD conjectures are correct, we would expect a design outcome of asymmetric control for powerful states in all cases. Next, we elaborate a logic of substitution whereby powerful states employ permissive earmark rules as a substitute for weighted voting. Finally, we propose variation in normative constraints—the presence of egalitarian or shareholder norms at the IO—as the critical intervening variable that determines when powerful states employ a substitution strategy.

Conceptualizing Asymmetric Power Among Participants in Programmatic IO Design

The design literature identifies states with asymmetric power by using standard balance-of-power metrics, most typically economic indicators like gross domestic product (GDP) or market share.Footnote 34 But reliance on uniform indicators across international agreements is problematic because “the kind of power relevant for various sub-issues is likely to vary.”Footnote 35 In the design of programmatic IOs, these proxies underestimate the power of small-market donors that loom large in providing official development assistance (ODA) and overestimate the importance of large-market states that make negligible contributions to multilateral organizations.

We conceptualize the capacity to contribute and a track record of financial support to multilateral organizations as the main sources of power in programmatic IO design. The fundamental reason is straightforward: recipient state demand for IO services outstrips the supply of funds across a range of economic and humanitarian assistance programs, and in climate finance. Buy-in from wealthy states is essential to the launch and success of any such IO, yet their participation is voluntary. The most powerful wealthy states are those that have demonstrated a willingness to provide substantial support to multilateral organizations. These states vary in important respects. However, they share an interest in asymmetric control over IO policy that stems from the financial support they provide. Joint concerns regarding fiduciary standards and efficient resource use are consistently demonstrated through initiatives at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Multilateral Organization Performance Assessment Network. Campaigns to target wasteful spending are often associated with the US, but Western European and Scandinavian donors have repeatedly joined those efforts.Footnote 36 These shared interests lead wealthy donor states to care about whether they exercise asymmetric control as a group as much as about the individual control they exercise over outcomes.

The Logic of Substitution in Institutional Design

Given that asymmetric power is present among participants in the design of programmatic IOs, how will powerful states design asymmetric control? We propose that from wealthy states’ perspective, weighted voting and permissive earmark rules can be used as design substitutes. In common usage, a “substitute” refers to “a person or thing acting or serving in place of another.” The verb “to substitute” is to “use instead of,” or “use as an alternative to.”Footnote 37 IR literature employs the language of substitutes in two contexts related to design. The first focuses on whether international and transnational policies are better thought of as “substitutes” or “complements.” When gridlock prevents successful intergovernmental policy, transnational policies are designed as an alternative or substitute to pursue the same goal.Footnote 38

The second context comes from literature on trade agreement design. In these cases, the inclusion of a particular design feature depends on member states’ access to a policy substitute outside the agreement. For example, Pelc explains, “if a government has access to flexibility through an alternative policy mechanism, it is less likely to seek to negotiate additional flexibility in multilateral talks.”Footnote 39 Here the implication is distinct. It is not that a state is unable to negotiate flexibility via tariff rates in WTO negotiations. Rather, states with flexible currency regimes find flexibility via tariff rates unnecessary.Footnote 40 As such, they choose not to expend political capital negotiating redundant design features.

Although the possibility is not often examined, both logics can apply within institutional designs when designers choose from a menu of rules that fulfill similar functions.Footnote 41 This is most obvious for the flexibility dimension of design where Helfer's list of formal flexibility mechanisms provides a ready-made playbook for designers eager to employ substitutes or scholars eager to theorize them.Footnote 42 For example, if a treaty fails to include an escape clause delimiting a provision's scope of application, an individual state may incorporate a reservation to the same provision during the ratification process as a substitute. If the escape clause is present, the reservation is less likely simply because it is less needed.

With regard to control, taking funding rules into account as a design substitute holds the potential to solve both puzzles we noted in the introduction. First, it would demonstrate that asymmetric control is present across more institutional designs than the conventional wisdom suggests. Second, it would help to explain why powerful states so often participate in and fund these IOs despite one-country-one-vote rules. When do powerful states substitute permissive earmark rules in place of weighted voting? We propose forum-specific normative constraints as the critical intervening variable.

Choosing Between Substitutes: How Norms Constrain Design

Norms scholarship outlines how logics of appropriateness can have regulative effects by constraining otherwise instrumentally advantageous behaviors. For example, in elaborating the “nuclear taboo,” Tannenwald argues its primary regulatory effect “is the injunction against using nuclear weapons first” even when it may be useful to do so.Footnote 43 Forum-specific norms can have similar regulative effects on institutional design.Footnote 44 In particular, egalitarian norms that emphasize legal and political equality are embedded in the UN system outside the Security Council. Egalitarian norms exist at multilateral development banks too, but they compete with norms from the private banking sector.Footnote 45 These norms have direct regulative effects on voting rules. To use Tannenwald's language, egalitarian norms provide an injunction against weighted voting, reflecting states’ equality under the law. Private sector banking norms, which base voting rights on shareholding, have decidedly inegalitarian implications and imply the same weighted voting rules that the UN system prohibits.

That distinct normative environments characterize the UN and World Bank is widely accepted.Footnote 46 Grigorescu demonstrates how egalitarian norms associated with democracy and sovereign equality led to the design of one-country-one-vote rules throughout the UN system, extending to programs, conferences, and specialized agencies.Footnote 47 This precedent was set at the UN's founding, and has persisted through the decades.Footnote 48 Path-dependent dynamics reinforce egalitarian norms. The vast majority of UN member states have a stake in the persistence of one-country-one-vote and incentives to reproduce it when establishing new IOs to extend their influence.

Egalitarian norms reinforced by path dependence lead to a first observable implication of our framework, consistent with the logic identified by scholars of transnational policies as substitutes. When IO membership is characterized by asymmetries in power and egalitarian norms are dominant, we expect permissive earmark rules to be incorporated as a design substitute.Footnote 49 Three further comments regarding this observable implication are required. First, it highlights the importance of sequence in the design process. Theories of design are often written as if all components are selected simultaneously, but in practice this is rarely the case. Representation and voting rules are typically part of an initial institutional bargain, while funding rules and other consequential features are negotiated later. Given this sequential process, it follows that funding rule design will depend on the voting rules in place.

Table 1. Summary of observable implications

Second, the observable implication provides an important reminder about the nature of path dependence. Too often path dependence is equated with inertia; in fact, it does not prohibit change, it only constrains and channels how change can be pursued. An IO that appears rigid and out of touch with power realities may look that way because our gaze is confined to a truncated set of design features. We evaluate whether things look different if we expand beyond the usual suspect of voting rules. Third, one might question why egalitarian norms do not prohibit permissive earmark rules. The answer is found in the fact that permissive rules were not perceived as inegalitarian when they were first introduced at the UN and were initially used to support issues of substantive interest to weaker states.Footnote 50 For this reason, they escaped criticism and their inegalitarian consequences were not foreseen. The enormous rise in the practice of earmarking has begun to change this (which we discuss in the empirical section).

At multilateral development banks, the presence of private sector shareholder norms prescribes weighted voting rules. Weighted rules were designed at the World Bank because “all negotiators were familiar with the proportioning of voting power to shares held in banks and commercial enterprises.”Footnote 51 Accounts based on archival evidence find little opposition to the US and UK proposal to incorporate weighted voting, reflecting the widespread view that shareholder norms were appropriate given the Bank's financial function.Footnote 52 Over time, these rules have been replicated across new MDBs despite developing countries questioning their fairness. Weighted rules are flexible relative to one-country-one-vote because they allow “weights” to shift according to change in the balance of power.Footnote 53 But it is worth noting that this flexibility is confined to the reallocation of weights. It is implausible to think that MDBs will adopt one-country-one-vote in the same way that a new UN program is unlikely to adopt weighted rules. Norms are again reinforced by path-dependent dynamics—powerful states have little incentive to radically alter rules to the benefit of others.

This leads to a second observable implication, which follows the logic of the earlier trade agreement design example. When IO membership is characterized by asymmetric power and shareholder norms we expect institutional designs to incorporate weighted voting rules, rendering permissive earmark rules unnecessary. Readers might raise the concern that wealthy states always prefer more control and will pursue permissive earmark rules even if weighted voting rules are in place. There are a number of reasons this is unlikely to be the case. North-South negotiations involve a host of politically sensitive issues—pursuing rules that minimize developing country influence generally produces bad optics for wealthy states. But more important to our argument is that although weighted voting and permissive earmark rules both skew control toward wealthy states, they are imperfect substitutes. They serve a similar purpose, but their consequences are not identical. Weighted voting rules allocate greater control to wealthy states in general, but on a sliding scale based on economic importance in the balance of power. Under weighted voting, the United States and Japan—large financial contributors—have a greater say in multilateral decision making than smaller wealthy states like Sweden and Norway. By contrast, permissive earmark rules allow all donors equal opportunity to restrict resources. For this reason, when weighted rules are in place, the largest beneficiaries—those who exercise the greatest control through weighted rules—have little incentive to design or to support the design of permissive earmark rules. Further, permissive earmark rules usually allow private actors the option to depart from state-determined multilateral priorities. Under a system in which wealthy states exercise disproportionate control through weighted voting, there is little reason to support permissive earmark rules that would enhance private actors’ control over resource distribution.

Implications for Institutional Creation and Forum Shopping

Beyond explicating design process and outcomes, the substitution framework has implications for understanding proliferation and forum-shopping dynamics within broader regime complexes.Footnote 54 We begin by exploiting differences in wealthy donors’ economic size to derive expectations about which powerful states will seek to establish new institutions in which venues. Drawing on the imperfect substitutes discussion, we expect large-market donors to have a first preference for weighted voting as a means to exercise control. This stems from their substantial individual influence via weighted voting rules. In contrast, the possibility of control through permissive earmark rules suggests that small-market wealthy donors may be more favorable to the UN. States like Sweden and Norway are critical donors but they lack large quotas at the World Bank and so do not exercise disproportionate individual control over outcomes through weighted rules. We consider whether small-market donors have a first preference for control via permissive earmark rules as a result. If this is the case, they will pursue institutional creation in IOs with egalitarian norms.

Finally, a straightforward expectation from the forum-shopping literature is that powerful states will select venues where rules are favorable to them. Programmatic IOs that offer powerful states asymmetric control over outcomes should receive more money than those that do not. An important rejoinder comes from Lipscy, who theorizes how a policy area's “propensity for competition” affects the desirability of forum shopping. IOs in competitive policy areas should “adjust frequently and flexibly or risk irrelevance” as a result of competitive pressure.Footnote 55 The UN system with its “rigid” voting rules appears to challenge this framework. Lipscy deals with this in two ways. First, he rightly points out that rich states have occasionally shunned IOs with one-country-one-vote rules (e.g., UNESCO). Second, he invokes the practice of earmarking and notes that “states have circumvented formal procedures by entering into co-funded or earmarked projects.”Footnote 56 This latter tack mistakes earmarking as detached from institutional design rather than a product of it. When funding rules are incorporated in the analysis, we expect UN institutions to look less rigid. This leads to a final observable implication. All else equal, we expect powerful states to provide less funding to IOs when they have failed to achieve asymmetric control via the design of weighted voting or permissive earmark rules.

Case Selection and Variable Operationalization

We evaluate these implications across eighteen international climate finance institutions (ICFIs) using the list of multilateral climate funds tracked by Climate Funds Update.Footnote 57 Asymmetric power, the independent variable, is constant across ICFIs. ICFI membership necessarily includes wealthy states that provide funding and developing countries as the intended recipients. Importantly, ICFIs offer variation on normative constraints, our intervening variable of interest. There are distinct advantages to evaluating the framework within the climate regime. It enables us to hold the “functional purpose,”Footnote 58 and relevant “policy area”Footnote 59 constant, which provide potential alternative explanations for design and for forum-shopping dynamics. Like development aid more broadly, climate finance can be regarded as a “competitive” policy area in which many IOs compete for attention and funding. Although not all ICFIs have an identical functional purpose, they share the goal of addressing climate change and a function of transferring funds to implement projects. The cases also offer variation on the normative constraints variable across narrower functional categories of adaptation, mitigation, and mitigation with a focus on reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD).Footnote 60

Institutional design scholarship is frequently criticized for offering hypotheses that impute functionalist intentions to designers and specific design processes only to infer intentions and processes based on outcomes alone.Footnote 61 Keenly aware of this shortcoming in the literature, we provide two cases that evaluate the design process of the Global Environment Facility and Green Climate Fund. We selected the GEF and GCF because they offer variation on the intervening variable of normative constraints, and because of their substantive importance to the climate regime as financial mechanisms of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In the case studies, we develop theoretically informed “causal process expectations” that link the independent and dependent variables.Footnote 62 In doing so, we are able to verify the proposed design process and distinguish the logic of substitution from other design processes, like boilerplate adoption, that might produce similar outcomes.

Operationalizing Power

Our conception of power in programmatic IOs emphasizes two sources: capacity to contribute and track record of contributions to multilateral organizations. To evaluate our implications related to design outcomes, we operationalize asymmetric power among participants at the group level, treating net donors as possessing asymmetric power as a group.Footnote 63 Assessing observable implications related to institutional creation requires that we distinguish between different types of powerful donors. To begin, based on our conception of power, we identify ten states that are among the most powerful donors in programmatic IO design. All ten states exceed the World Bank's high-income threshold (capacity to contribute) and are top providers of UN operational activities for development (track record of multilateral contributions), which, like climate finance, rely on voluntary contributions. We treat G7 members as large-market donors and non-G7 members as small-market donors and derive expectations accordingly.

Operationalizing Normative Constraints

We rely on accepted understandings of norms governing representation and voting rights at the UN and MDBs, respectively. We treat ICFIs established within the UN system as governed by egalitarian norms and those established within MDBs as governed by shareholder norms. The coding of ICFIs independent of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) is straightforward: egalitarian norms are present at ICFIs established within the UN system and shareholder norms are present at ICFIs created within the MDBs. For ICFIs with a formal relationship to the COP, we pay attention to both the model that designers sought to replicate (UN versus MDB) and to the accountability relationship with the COP itself, which reflects UN norms and operates using one-country-one-vote. UNFCCC financial mechanisms that are associated with the MDB model and not directly accountable to the COP are coded as having shareholder norms. ICFIs associated with the UN model and accountable to the COP are coded as subject to egalitarian norms.

Coding Voting and Funding Rules

To identify relevant voting rules, we first identified governing bodies that ultimately approve ICFI projects before they are implemented. For independent ICFIs, like the GEF, the relevant body is the GEF Council. For ICFIs hosted by an IO, like the Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Program (ASAP) hosted by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the relevant governing body is the executive board of the host institution (i.e., the IFAD executive board).

ICFIs represent an interesting class of cases when coding earmark policies.Footnote 64 All ICFIs distribute resources from trust funds to finance mitigation and adaptation. The trust fund language is significant because, in most analyses, all contributions to trust funds are categorized as earmarked.Footnote 65 This categorization reflects that trust funds are already separate from general IO budgets. For example, IFAD member states “earmark” funds into ASAP in that they are specifically tagged for ASAP rather than the regular IFAD budget. However, this broad definition overlooks that funding rules vary even at the trust fund level. We adopt a narrower definition of earmarked funding that requires earmarks to be allowed within the ICFI. That is, rather than categorize all ASAP funding as earmarked because it is technically a trust fund, we look to see whether donors can earmark contributions within ASAP. We code ICFI funding rules as permitting earmarks when they allow donors to specify how their contributions are used in various ways. We distinguish between rules that permit “strong” and “weak” earmarks. The latter category allows donors to earmark into only predetermined windows, which often represent broad themes like mitigation or adaptation. Strong earmarks permit donors to stipulate what they wish, including the project or recipient of their contributions.

The Design of International Climate Finance Institutions

The provision of climate finance to developing countries is central to the climate change regime. From a practical perspective, it is needed to prevent large developing states from becoming major carbon emitters by investing in clean technologies. For the most vulnerable developing states already experiencing effects of the climate crisis, effectively applied adaptation finance is paramount to survival. ICFIs are multilateral institutions designed to invest in projects to meet these ends: to mitigate current and future emissions and to assist developing states in adapting to climate change impacts.Footnote 66

The Asymmetric Power of Donor States in ICFI Design

ICFI mandates have a clear programmatic component and the need to generate resources makes states capable of contributing significant sums of money powerful. Demand from recipients to access ICFI resources far exceeds supply.Footnote 67 Treating net donors as possessing asymmetric power relative to net-recipient states also reflects climate finance literature highlighting the shared interests of wealthy donor states on the one hand and developing states on the other. Wealthy states generally share the view of ICFIs as trustees of financial contributions aimed at reducing carbon emissions, and more recently, adaptation. Conceptually, ICFI financial contributions are considered voluntary rather than obligatory, not unlike other official development assistance.Footnote 68 With this perspective, donors expect to control project selection and demand efficient management and measurable results in return for contributions. Developing-country recipients generally have a different perspective. They see financial contributions as reparations for damages caused by developed states’ carbon emissions.Footnote 69 They see ICFIs as vehicles to distribute these funds and wealthy states have little right to dictate their use.

The importance attached to control is enhanced by how donors’ and recipients’ divergent conceptions of climate finance translate into distinct preferences about distributing resources. Donor states prefer to support mitigation activities, which they benefit from, and have sought to prioritize “bankable” mitigation projects.Footnote 70 Recipient countries have pushed for a larger share of climate finance for adaptation, which typically produces local benefits rather than global ones,Footnote 71 and for resource allocation that prioritizes national priorities rather than efficiency.Footnote 72 These differences mean that who controls international climate finance institutions matters. If ICFIs are controlled by wealthy countries, resource allocation decisions are likely to look different than if they are controlled by developing countries.

Normative Constraints

Table 2 lists the ICFIs, their host institution, relationship to the COP, and resulting normative constraints on voting rules. This clarifies the empirical point that once a forum is selected, voting rules are effectively settled. This happens in one of two ways. First, for ICFIs independent of the COP, the relevant host institution's executive board exercises ultimate authority over the establishment, extension, or closure of the ICFI, and over project approval. For instance, the IFAD executive board exercises authority over ASAP. World Bank ICFIs are formally established by the board of directorsFootnote 73 and projects must be approved by the executive board of the relevant implementing agency, which is often the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development or the International Development Agency, but may include other regional development banks.Footnote 74 Second, the voting rules of ICFIs with governance independent of their host institution reflect the rules of the forums in which they were established. The GCF and Adaptation Fund were established by the COP/CMP, which operate using one-country-one-vote. Both have a strong accountability relationship to those bodies. The GEF is also a financial mechanism of the UNFCCC, but its establishment as a pilot program at the World Bank predates the treaty, and its accountability to the COP is weak.Footnote 75 After gaining independence from the Bank in 1994, the GEF adopted a constituency voting system similar to the Bank's.

Table 2. ICFIs and normative constraints

Asymmetric Control: Weighted Voting or Permissive Earmarks

The theory provides observable implications regarding how donor states will design rules that allocate control based on an IO's operative normative constraints. The first implication follows the framework's substitution logic, expecting that in the presence of egalitarian norms, permissive earmark rules will be incorporated in ICFIs as a design substitute. The second implication provides that when shareholder norms are present, wealthy donor states will find success in designing asymmetric control through weighted voting rules. Table 3 summarizes the findings. With regard to the first implication, four of the five cases with egalitarian norms allow permissive earmarks (UN-REDD, ICCTF, MDG Achievement, GCF), consistent with expectations. Further, all four permit strong earmarks that allow donors to attach stipulations that go beyond predetermined funding windows. The Adaptation Fund incorporates neither weighted voting nor permissive earmark rules. We explore the consequences later.

Table 3. ICFI design outcomes

Note: *In its initial resource mobilization, the GCF accepted contribution arrangements from member states that specified conditions on funding. Funding rules at the GCF are contested, which we discuss in detail later.

With regard to the second implication, eleven of thirteen cases with shareholder norms incorporate weighted rules and prohibit both strong and weak earmarks. The two ICFIs that technically allow earmarks (SCCF and BioCarbon Fund) include multiple financing windows, and donors must indicate their preferred window. All thirteen ICFIs with shareholder norms (including the SCCF and BioCarbon Fund) prohibit strong earmarks, defined as the country- or project-specific level. In sum, all ICFI outcomes—except at the Adaptation Fund—conform to our expectations. When funding rules are taken into account, asymmetric power is reflected in asymmetric control in seventeen of eighteen ICFIs. Although eighteen cases are not sufficient to conduct standard regression analysis, we conducted two statistical tests appropriate to our small-N study and the results are consistent with the substitution argument.Footnote 76

Examining the Design Process: The GEF and GCF

We now evaluate causal process expectations of our framework for the GEF and GCF, the two largest UNFCCC financial mechanisms. The GEF predates the UNFCCC. It was established as a pilot program at the World Bank in 1991. It was named the first financial mechanism of the COP when the treaty entered into force in 1992 and it became independent from the Bank in 1994. Due to its origins, and because its constituency-based voting system and replenishment rules reflect the shareholder norms of MDBs, the GEF has consistently faced criticism from developing countries that it is dominated by wealthy states. This perception provided an important impetus for the establishment of the GCF, which became operational in 2015. The GCF design incorporates stronger representation and voting rights for developing states. However, consistent with our substitution framework, wealthy states have pursued asymmetric control through funding rules.

The Global Environment Facility

The GEF design includes weighted voting rules and funding rules that prohibit earmarks. We began by investigating possible alternative explanations for the absence of permissive earmark rules. One possibility is that the GEF informally permits earmarks, rendering a formal rule unnecessary. To attend to this possibility, we contacted GEF staff on the question of informal earmarks. They responded that, “No, the donors and GEF can't and don't earmark for specific projects, formally or informally.”Footnote 77 A former US Treasury official confirmed that to their knowledge, informal earmarking within the GEF Trust Fund did not occur.Footnote 78

A second alternative explanation for the absence of permissive earmark rules is that wealthy states pursued permissive rules but faced resistance and failed. Such attempts are inconsistent with the logic of substitution, which expects wealthy states to be content with their influence through weighted voting. We evaluate this alternative explanation against our own causal process expectations, which include the following: (1) wealthy states should express satisfaction with their control at the GEF in the absence of permissive earmark rules; (2) as a result, funding rules should not be a major topic of debate; and (3) if permissive funding rules are discussed it should not be at the behest of major donors.

Evaluations from donor groups and bilateral aid agencies indicate satisfaction with donor control at the GEF. The Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network's 2017–2018 donor survey notes that “decision-making on resource allocation is rated as highly satisfactory.”Footnote 79 A former US Treasury official remarked that aside from council voting rules, GEF replenishment rules and the process they engender allows the US to exert substantial influence.Footnote 80 Other bilateral donors express similar satisfaction. An evaluation of the GEF from Denmark notes that “key Danish priorities” are reflected in the GEF's organizational strategy, “where Denmark succeeded in influencing the GEF seventh Program” through replenishment negotiations and as an active participant on the GEF Council.Footnote 81 Similarly, an evaluation from the Department for International Development (DFID), the United Kingdom's aid agency, notes the UK's satisfaction with GEF resource allocation and with the GEF's general responsiveness to donors: “reform measures requested by the UK (and other donors) under GEF4 have been achieved.”Footnote 82

To evaluate the second and third causal process expectations, we reviewed 463 GEF documents from between 1994 and 2017. This includes the joint summary of the chairs and highlights from the GEF council meetings (74 documents), the chair's summary of the GEF assembly meetings (5 documents), replenishment meetings (269 documents), and the GEF council work programs (115 documents). We searched each document for “earmark” and “target.” We then read the passage in which the term was used and the previous and subsequent passages to ascertain whether use of the term was consistent with our meaning. “Earmark” sometimes refers to action by the GEF Council rather than by a donor. After filtering for consistent usage, we found just ten instances when the term was used to refer to the possibility of changing GEF rules to permit donor earmarks. All ten instances occurred in the period leading to the GEF's fifth replenishment in 2008–09.

GEF replenishment occurs every four years. Replenishment meetings include only “Replenishment Parties,” defined as those member states that contribute more than USD 4 million SDR to the GEF Trust Fund.Footnote 83 During the GEF-5 replenishment, thirty-four states participated. However, proposals regarding changing GEF Trust Fund rules to allow a limited form of earmarks came from the Secretariat, rather than the Replenishment Parties. The Secretariat was contemplating how to increase resource mobilization in the context of the global financial crisis.Footnote 84 It proposed several options, including auctioning carbon allowances, transportation taxes, and “Allowing Supplemental Targeted Contributions within the GEF Trust Fund.”Footnote 85 The Secretariat proposed that the GEF lift its earmark prohibition when donors exceeded the normal burden-sharing arrangement at the GEF. But the Secretariat's main goal was likely to broaden its donor base by offering private actors the ability to earmark. The Secretariat noted that “many governments and particularly private donors, such as foundations” might be willing to earmark contributions to specific focal areas (like biodiversity or climate change). The Secretariat argued that the GEF was missing out on such funds “because the GEF is not in a position to earmark bilateral donations to specific focal areas.”Footnote 86 The link between permissive earmark rules and expanding the resource base to include private actors was again noted in a draft GEF-5 programming document in 2009.Footnote 87

The proposal to allow earmarks was not adopted in 2009 or thereafter. Interestingly, and consistent with our conception of earmarks as imperfect substitutes for weighted voting, some GEF donors explicitly opposed the proposal. The United States had expended great effort in persuading the GEF Council to adopt a Resource Allocation Framework (RAF) to distribute GEF funds. The RAF allocates resources based on countries’ ability “to generate global environmental benefits and their capacity, policies and practices to successfully implement GEF projects.”Footnote 88 Donors who supported the RAF, including the US, were concerned that permitting earmarks would undermine the framework. They feared that even a policy that hardened the GEF focal areas into separate trust funds “could encourage donors to earmark resources for their respective preferred programs, thereby possibly undermining the RAF and the integrity of the GEF Trust Fund.”Footnote 89

The Green Climate Fund

The initial composition of the GCF board reflects the UN's egalitarian norms. Its twenty-four members, which include an equal number of developing and developed states with attention to regional groupings, each possess a single vote. The GCF Instrument, which outlined basic governance, included only limited language on funding. It states that, “the Fund will receive financial inputs from developed country Parties to the Convention.” And, “the Fund may also receive financial inputs from a variety of other sources, public and private, including alternative sources.”Footnote 90 Our framework expects wealthy states to pursue permissive earmark rules as a design substitute in this context. We evaluate the following causal process expectations: (1) permissive rules should be pursued by wealthy states rather than weaker recipient states; (2) recipient states should oppose permissive earmark rules; and (3) should indicate that they oppose permissive earmarks because they undermine control by governing bodies, causing resources to be distributed unfairly. In what follows we trace policy debate in the GCF board and find support for the logic of substitution.

Wealthy states’ pursuit of permissive earmarks at the GCF began prior to its initial resource mobilization period in 2014. At that time, the GCF board agreed to “consider the policies for contributions based on recommendations from the first meeting of interested contributors.”Footnote 91 One possibility was a clear prohibition on earmarking/targeting, like that adopted at the Adaptation Fund. Yet at Interested Contributor meetings “there was consensus on removing the suggested prohibition against targeting.”Footnote 92 The Interested Contributor group proposed that the GCF permit earmarks but used the language of “targeting contributions” rather than earmarking. The contributor group acknowledged that the board had already agreed “to aim for a 50:50 balance between mitigation and adaptation,” but they proposed that “contributors may request that their contributions be targeted to the Fund's two windows (mitigation and adaptation)” and to its third option, the Private Sector Facility.Footnote 93 Technically, the policy proposal constitutes a weak rather than strong earmark, but one with a significant impact. Permitting donors to earmark across windows would make the GCF's ability to meet its 50:50 distribution between mitigation and adaptation (something developing states fought hard for) contingent on donors’ individual funding decisions.

Developing states did not receive the proposal favorably. At the board's eighth meeting, concerns were raised that “targeting is a soft phrase for earmarking,” and a number of states indicated that “the earmarking of contributions would not be acceptable to them.” Meeting minutes show that the developing country co-chair “noted that earmarking politicizes the Fund by favoring particular countries or projects” and expressed concern that the board would lose its ability to ensure resources were distributed as previously agreed.Footnote 94 The facilitator of the process, Ambassador Lennart Båge (Sweden), attempted to assuage concerns, noting that “the concept of earmarking has been rejected,” and “a concept of targeting was in the text instead” though he did not indicate a difference between the two concepts.Footnote 95 He further emphasized that the board would remain in a strong position to control resource allocation,Footnote 96 but did not explain how. Some members sought to address the issue by supporting a targeting country cap but others insisted that the term be removed from the text entirely.Footnote 97 The board did not reach a decision on the issue. However, when the GCF Trust Fund entered into contribution arrangements with donors, a number included “targets” as proposed by the Contributor Group. Board members identified these “targets” as earmarks in subsequent meetings.Footnote 98

The Contributor Arrangements demonstrate the targets specified by donors to date. The arrangement with the US notes that the United States “expects that the GCF will utilize at least 50 percent of any US financial support to the GCF to support private sector activities.”Footnote 99 Other contributors like Canada and the United Kingdom similarly target their resources for the Private Sector Facility.Footnote 100 The Australian contribution arrangement requests the narrowest stipulation by specifying the region it wishes to support rather than a funding window. It notes that “the Australian Government has requested that our contribution should facilitate, including through the GCF's Private Sector Facility, private-sector led economic growth in the IndoPacific region.”Footnote 101

The behavior of developed and developing states maps extremely well onto the causal process expectations of the substitution framework. As the GCF continues to evolve, however, its operative norms and their constraining effects may shift. On the one hand, negotiations demonstrate that developing states increasingly view permissive earmark rules as violating egalitarian norms. If this continues, it may limit powerful states’ ability to use permissive earmarks as a substitute. On the other hand, the rules governing the GCF's initial resource mobilization are in flux and subject to change in subsequent periods. The GCF has already transitioned from an ad hoc pledge system, similar to that used by UN development institutions, to a formal replenishment process based on the MDB model. Preparation for replenishment requires that states “review and update the policies for contributions with regard to items such as … earmarking, [and] relationship to decision-making.”Footnote 102 The suggestion that states revisit the relationship between contributions and decision making indicates that some donors are still willing to float weighted voting as a possibility. There is also suggestive evidence that if wealthy states fail to achieve asymmetric control, some will shift funds elsewhere, consistent with our expectation regarding resource mobilization. ICFIs designed with sunset provisions to avoid duplication with the GCF were recently extended, possibly to allow donors to retain an alternative to the GCF if they are dissatisfied with their influence there. Ultimately, tensions between fundraising imperatives and accountability to developing states mean that the GCF design and its fundamental character remain subject to contestation.

Expectations for ICFI Creation and Forum Shopping

We now broaden our analysis to evaluate whether funding rules and the logic of substitution affect ICFI creation and forum-shopping dynamics as expected. To assess our third and fourth observable implications (see Table 1), we identify ten powerful states in programmatic IO design based on past contributions for UN operational activities for development. Table 4 lists each state in order of its contributions, along with its respective GDP and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) vote share. The list demonstrates that states of similar importance in the provision of voluntary multilateral contributions (e.g., Japan and Sweden) vary widely in the size of their economies, and in turn, in the individual control they receive via weighted voting at the World Bank.

Table 4. Top contributors to UN operational activities for development

Notes: Top contributors data come from Report of the Secretary-General (A/73/63–E/2018/8) and UN Pooled Funding Database 2016. *GDP (USD millions) and IBRD vote share in 2019 from the World Bank (last accessed 8 January 2019).

This variation suggests wealthy states’ preference for weighted voting or permissive earmark rules may differ depending on the size of their economy.Footnote 103 We expect large-economy donor states in particular—here operationalized as G8 members, shaded gray in Table 4—to pursue ICFIs in venues with preexisting weighted voting rules. Conversely, we consider the possibility that small-economy donors have a first preference for permissive earmark rules. If correct, these donors will pursue new ICFIs within the UN system despite egalitarian voting rules with an aim to design permissive earmark rules.

To evaluate these expectations we traced the origins of all eighteen ICFIs. Table 5 summarizes our findings. Consistent with expectations, large-economy donors played a key role in the design of ICFIs hosted by MDBs. The US, Japan, and the UK played a lead role in establishing the Clean Technology Fund,Footnote 104 Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR), Forest Investment Program (FIP), and Scaling-Up Renewable Energy for Low Income Countries (SREP), all at the World Bank.Footnote 105 Another Bank-hosted ICFI, the Forest Carbon Partnership Fund (FCFP), was spearheaded by Germany.Footnote 106 More generally, the G8 countries make favorable reference to the World Bank and the GEF as the proper vehicles through which FCCC goals can be pursued.Footnote 107 For example, the G8 2005 Gleneagles Communique stated “The World Bank will take a leadership role in creating a new framework for clean energy and development, including investment and financing.”Footnote 108 Supportive evidence also comes from the behavior of large-economy donors with regard to UNFCCC financial mechanisms. The United States, Japan, Germany, and France were early proponents of the GEF's placement at the World Bank and thereafter advocated for the GEF to host additional ICFIs, including the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), and Strategic Priority on Adaptation (SPA).Footnote 109 However, we are careful not to overstate support for observable implication 3 in the context of the UNFCCC. In general, all wealthy states have demonstrated support for the GEF, consistent with our broader emphasis on the interests that donors share as a group.

Table 5. ICFI creation by large and small economy donors

Support for expectations regarding the behavior of small-market donors is somewhat weaker. The GCF and AF are products of the COP and CMP respectively. Developing states took the lead in lobbying for their creation. COP negotiation dynamics also make distinguishing large- and small-economy donor preferences difficult because the major groups incorporate both types of states.Footnote 110 Outside the FCCC, two ICFIs, UN-REDD and the MDG Achievement Fund, provide supporting evidence. Norway, a small-market donor, is responsible for the establishment of UN-REDD.Footnote 111 Spain is solely responsible for establishing the MDG Achievement Fund. While not a top-ten donor, as a non-G8 member Spain is expected to behave like other small-market donors on our list and to have a preference for permissive earmark rules over weighted voting.

Not surprisingly, other ICFIs were created not solely or primarily as a result of donor states’ wishes, but primarily in response to developing states’ demands (Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund—ICCTF, AF, GCF), or were championed by actors within the IO bureaucracy (PMR, ASAP). The former is consistent with the general expectation that developing states will pursue the creation of ICFIs within the UN system. The latter falls outside the scope of our theoretical framework and is consistent with scholarship that emphasizes the importance of IO bureaucrats in the creation of new IOs.Footnote 112

Forum-Shopping Expectations: Whither Adaptation Fund?

A final implication of our framework speaks to broader questions about when powerful states will turn toward informal or external methods of influence at IOs. We expect this to occur when ICFIs lack both weighted voting and permissive earmark rules. ICFIs that lack asymmetric control should face funding shortfalls relative to ICFIs that incorporate either weighted voting or permissive earmarks. Among the eighteen cases we examine, only the Adaptation Fund (AF) clearly lacks both sets of rules and, consistent with expectations, it has struggled to mobilize resources. All else equal, we would not expect the AF to face such a challenging financial situation. For donors inclined to provide adaptation finance, three factors pull in its favor. First, the AF is a formal mechanism of the UNFCCC. Second, it was designed to cover the full range of adaptation projects rather than a narrow subset (like ASAP) or pre-investment plans (like the LDCF). Third, it is regarded as competent and effective. A 2015 independent evaluation of the AF provided strikingly positive findings. The AF Secretariat is characterized as capable of “thinking outside the box,” and is “collaborative versus competitive,” and crucially, was deemed to “provide good value for money.”Footnote 113 Despite its high marks for competence and efficiency, Marcia Levaggi, manager of the AF board, characterized the fund in 2015 as “facing a difficult situation in terms of financial sustainability.”Footnote 114 Indeed, its weakness in resource mobilization is regarded as an “exception” to an otherwise effective ICFI.Footnote 115

The AF struggles to compete with ICFIs that incorporate rules that allocate greater control over outcomes to wealthy states. Two sets of ICFIs provide relevant comparisons. Table 6 compares the AF to the other UNFCCC financial mechanisms.Footnote 116 Independent of institutional design, we would expect total and average pledges to the AF to be lower than to the GEF or GCF. Mitigation is more popular than adaptation. Yet the gap is striking. The GEF averaged USD 280 million each year for its climate theme during its last replenishment cycle, or about five times the average annual contributions to the AF. It also attracted support from twice as many donor states.

Table 6. Comparison of FCCC financial mechanisms

The comparison to the GCF is more apt and provides an even starker gap in support. The first GCF row reports total numbers. The second row (italicized) reflects the mandated 50:50 mitigation/adaptation split on GCF funds. USD 5.151 billion reflects GCF pledges mandated for adaptation with average pledges per year of USD 1.288 billion. Some criticize GCF accounting and suggest that “adaptation” is generously interpreted to create the perception that the GCF is meeting its goal. Even if one accepts this criticism, and the accompanying assertion that just 30 percent of GCF projects are allocated for adaptation,Footnote 117 average pledges per year for adaptation would remain fourteen times the level of those the AF received. Evaluators have noted the GCF's attractiveness relative to the AF in assessing its financing difficulties. The independent evaluation notes: “The GCF has sucked up all the oxygen in the system. There just isn't enough left over to support the Adaptation Fund.”Footnote 119

Table 7 provides a second set of relevant comparisons: ICFIs that focus solely on adaptation activities. Although all are adaptation focused, apples-to-apples comparisons are difficult because some have narrow purposes such that we would expect lower contribution levels. For instance, the LDCF was designed to fund National Adaptation Programs for Action, an institution-building exercise aimed at improving knowledge and capacity to identify urgent adaptation needs in least-developed countries. The Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Program (ASAP), as the name suggests, focuses on a narrow range of adaptation projects relevant to IFAD's mandate. By contrast, when it became operational, and for reasons we noted before, the Adaptation Fund was viewed as “the big game” for adaptation finance.Footnote 120

Table 7. Comparison of adaptation ICFIs

Funding data demonstrate the AF struggles to attract pledges on par with the alternatives. The PPCR, governed by the World Bank, receives larger contributions from its donors. Surprisingly given its modest aims, pledges to the LDCF exceed those of the AF. Average pledges per year at the AF just exceed those of ASAP, the smallholder agriculture fund governed by IFAD. Only the MDG Achievement Fund (now closed) significantly trails the AF. Given its broad adaptation mandate, the PPCR provides perhaps the most relevant comparison. Although the AF receives contributions from more states, a few key contributors—including the United States—are absent from the AF and fund the PPCR generously in relative terms. Indeed, consistent with our theoretical expectations, the PPCR was “widely interpreted as a move to compete with the AF.”Footnote 121

The unique design of the AF has contributed to its “high symbolic value for developing countries,”Footnote 122 and a few powerful states, notably Germany, make sizable contributions.Footnote 123 Yet consistent with our framework's expectations, the absence of asymmetric control for wealthy donors contributes to the AF's financial struggles and the general trends demonstrate that donors favor alternatives like the PPCR and GCF.

Conclusion

Expectations that powerful states seek to control IO policies are common in IR, but empirical knowledge about which formal rules facilitate control has been largely confined to voting. As a consequence, conjectures proposing a causal link between asymmetric power and asymmetric control have found only mixed support. We proposed that a menu of formal rules has an impact on the allocation of control across member states. When the rules are overlooked, our ability to assess expectations about design, or about the relative financial support an IO receives within a regime complex, are significantly hampered. Funding rules are especially important in this regard because they can offer asymmetric control to wealthy states even at IOs that otherwise appear favorable to developing countries. When they are not taken into account, we miss an important power dynamic.

Leveraging our empirical insight of funding rules’ importance, we propose a novel framework to explain institutional design based on the logic of design substitutes under normative constraints. We demonstrate how wealthy states pursue permissive earmark rules in ICFIs subject to egalitarian norms that call for strong representation and voting rights for developing states. Conversely, we show that when weighted voting is in place, wealthy states rarely raise the issue of permissive earmark rules. We also demonstrate how donors’ economic size, and the individual control they receive through weighted voting as a consequence, affects whether they favor establishing ICFIs within the World Bank or the UN system. Finally, we show how the Adaptation Fund, an outlier among our cases in its symmetric allocation of control, struggles to mobilize resources relative to the alternatives. Our analysis of eighteen ICFIs sheds new light on power dynamics in the climate regime and helps to integrate environmental institutions and the UN system into a literature dominated by studies of the World Bank, IMF, and trade agreements.

Three research avenues stem from our analysis. First, future work should consider substitution dynamics across other design features. With regard to rules that allocate control, we outlined three alternatives to voting rules: differential punishment, replenishment, and executive head appointments. One possibility suggested by our case studies is that rules specifying high contribution thresholds to participate in replenishment negotiations may provide an additional substitute to weighted voting rules for wealthy states. We do not claim to have exhausted the relevant possibilities, however, and believe that qualitative case studies can illuminate relevant rules that can subsequently be coded across larger groups of cases.

Scholars can also consider substitution dynamics for other design dimensions. Three possibilities come to mind. A burgeoning literature on the design of flexibility identifies numerous mechanisms, and careful thinking is required about which are potential substitutes—even imperfect ones—and which fulfill distinct purposes.Footnote 124 A second possibility is to consider substitutability in the design of oversight mechanisms that states use to hold IO bureaucracies accountable.Footnote 125 A third avenue could illuminate possible substitutes for granting nonstate actors’ access to IOs. In each of these three possibilities, but perhaps especially in the last two, norms or other forum- or issue-area-specific constraints are likely to shape rule selection. For example, norms of independence at international courts effectively prohibit many control mechanisms—like firing judges—that are permitted at other IOs, which may lead states to pursue subtler, less visible substitutes. Similarly, IOs in some issue areas—environment and health—are more open to providing transnational actors membership or observer status, but there may be alternative rules used to gain access in more constraining environments.Footnote 126 These are but a few examples where substitution dynamics are likely to emerge in the design process over time.

Second, taking funding rules into account, research can investigate the relationship between institutional design and forum-shopping behavior to assess the extent to which permissive earmark rules promote fundraising on par with weighted voting rules. We show the Adaptation Fund's weak fundraising capacity relative to ICFIs that grant asymmetric control through permissive earmarks or weighted voting, but further testing across a wider range of IOs is necessary to determine the relative fundraising appeal of these different rules. Our analysis suggests that permissive earmark rules may be more attractive to important small-economy donors like Norway, and weighted rules are especially appealing to large-economy donors like the United States. Future work can test these expectations across other issue areas.

Third, our analysis indicates the relationship between formal and informal rules is worthy of greater attention. Our work does not undercut the importance of informal control mechanisms at IOs, but it does suggest that a bifurcated framework in which formal rules govern ordinary times and informal procedures manage extraordinary circumstances may not always hold. When voting produces outcomes that powerful states dislike, the states may move to exert control using alternative formal rules. More complete knowledge of formal design is useful for deriving and assessing expectations about when departures from formal rules are likely. Questions of how formal design shapes the bounds of informal practices of control, whether formal and informal mechanisms provide complementary or contradictory influence, and whether they empower the same set of actors, are all central to understanding how states exercise control over IO policy outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XJ1UQK>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000181>.

Acknowledgments