Introduction

Severe epistaxis has traditionally been treated with nasal packing, often with discomfort to the patient.Reference Douglas and Wormald1

We report the case of a patient who developed a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak following nasal packing for epistaxis.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old woman presented to our department following her first episode of spontaneous epistaxis. She had suffered severe posterior epistaxis originating from the right nasal cavity, which had started in the early hours of the morning. She had been managed initially at another institution's emergency department, where a Rapid Rhino (Arthrocare ENT, Austin, Texas, USA) inflatable nasal pack had been inserted into the right nasal cavity without the use of any instrumentation. The pack had adequately controlled the bleeding, and the patient had been transferred to our unit for admission and further management.

On admission, the patient was stable, her blood pressure and other vital signs were within the normal range, her haemoglobin concentration was 11 g/dl, and her platelet count and clotting tests revealed no abnormalities. She was comfortable with the nasal pack in situ and had no evidence of bleeding. The only past medical history of note was that she was a non-insulin-dependent diabetic, well controlled on medication. She reported experiencing extreme discomfort on insertion of the pack.

The nasal pack was left in overnight and deflated and removed the following morning. On deflation of the pack it was noted that 16 ml of air had been inflated.

During a period of observation, the patient was noted to have no further epistaxis. However, she developed right-sided rhinorrhoea shortly after pack removal. The rhinorrhoea was watery in nature and became more profuse as the day progressed. The patient also experienced nasal blockage on the same side.

The rhinorrhoea fluid was collected for analysis and was found to be positive for B2-transferrin, confirming suspicion of a CSF leak.

Endoscopy was attempted but proved very difficult due to a significant amount of trauma and swelling of the right nasal cavity.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the sinuses was performed. This revealed opacification of the right nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses but no visible injury to the anterior skull base.

A decision was made to manage the case expectantly, as the CSF rhinorrhoea was decreasing and endoscopic examination remained difficult due to severe nasal congestion unresponsive to vasoconstriction. The patient was given Pneumovax (Sanofi Pasteur, Lyon, France) to prevent pneumococcal meningitis.

On the sixth day post-admission, the patient's rhinorrhoea had resolved, and she was discharged the following day. She did not develop any other complications during her admission.

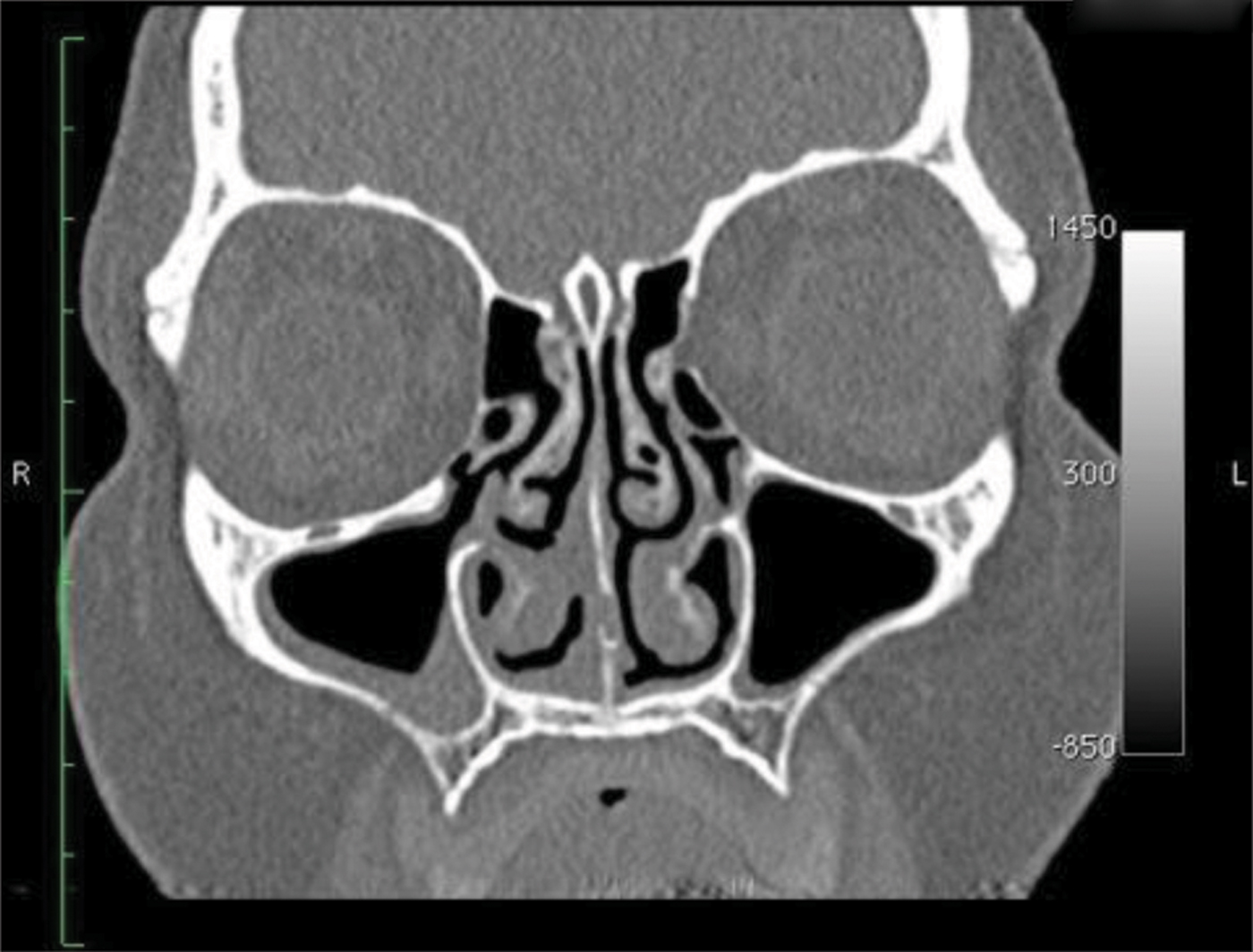

Follow-up imaging was arranged. A CT scan performed two to three weeks post-injury revealed a fracture of the right middle turbinate at its superior insertion into the skull base (Figure 1). The patient had no further CSF leakage over the following three months.

Fig. 1 Coronal computed tomography image showing the base of skull fracture at the superior insertion of the right middle turbinate. R = right; L = left

Discussion

Severe epistaxis has traditionally been treated with nasal packing, especially in the case of posterior bleeding. However, recent advances in nasal packing devices, haemostatic agents and endoscopic techniques have provided effective treatment options that are better tolerated by patients.Reference Douglas and Wormald1 Nasal packs such as the Merocel (Medtronic, Mystic, Connecticut, USA) and Rapid Rhino brands have been found to be as effective in controlling epistaxis, with greater ease of insertion, when compared with ribbon gauze coated in bismuth iodoform paraffin paste.Reference Douglas and Wormald1 These two brands of nasal pack have been compared in more than one study, and have been shown to have equal efficacy in controlling epistaxis; however, the Rapid Rhino pack was found to be more comfortable for patients during insertion and removal.Reference Douglas and Wormald1, Reference Moumoulidis, Draper, Patel, Jani and Price2

There is a recognised risk of CSF leakage following trauma to the middle turbinate, due to its superior attachment to the skull base at the cribriform plate.Reference Cavusoglu, Yazici, Demirtas, Gunaydin and Yavuzer3, Reference Patiar, Ho and Herdman4 This superior sagittal attachment is suspended from the articulation of the cribriform plate and lateral cribriform lamella, and this region is the area most likely to develop CSF leaks during endoscopic sinus surgery, due to its thin bony structures.Reference Welch and Palmer5

In this case report, we describe a fracture of the middle turbinate at its superior insertion, with confirmed CSF leakage, following nasal packing. No previously reported cases of this kind could be found in the literature, using a PubMed database search.

The manufacturer's instructions on insertion of the Rapid Rhino pack were reviewed. After insertion, the balloon catheter must be inflated, with pressure and not volume used as the guide to adequate inflation. The instructions state that the inflation pressure should be judged by palpating the pilot cuff. The maximum volume of air that can be infused is given as 30 ml; however, this amount should rarely be required. Higher volumes may be required only when the Rapid Rhino pack is used for post-operative packing of large tumour resections, with a resultant larger nasal cavity.

• A case of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage after balloon nasal packing for epistaxis is presented

• Such packs carry a risk of CSF leakage, especially when over-inflated

• Staff using such packs should receive adequate training and understand sinonasal anatomy

In the presented case, the significant pain and discomfort felt by the patient at the time of packing, and the evidence of trauma in the affected nasal cavity, leads us to the conclusion that the injury occurred during the initial insertion and inflation of the nasal pack. The balloon was probably inserted between the middle turbinate and the nasal septum, thereby lateralising and fracturing the turbinate. The inflated pack tamponaded the bleeding as well as the CSF leak, the latter becoming apparent after deflation and removal.

Conclusion

This case is to our best knowledge the first report of its kind, and demonstrates a potential risk associated with nasal packing, especially with over-inflation of balloon packs. It also highlights the need for an appreciation of sinonasal anatomy, and adequate training in the use of commercially available nasal packs, for medical practitioners attending patients with epistaxis.