Asian Americans have greatly benefited from the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which opened the door to entry into the United States by eliminating both national-origin quotas and long-standing policies of Asian exclusion. Departing sharply from California's “Anti-Coolie Act” of 1862, and the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and subsequent extensions, the 1965 act finally brought more than one hundred years of official anti-Asian legislation to a close. During that period, Asian Americans were unduly taxed, restricted in movement, deprived of property ownership and voting enfranchisement, denied habeas corpus, driven from their homes by anti-Chinese riots, and imprisoned in internment camps by their own government (Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002; Ngai Reference Ngai2004, Daniels Reference Daniels2004; Haney-López Reference Haney-López2006b, Pfaelzer Reference Pfaelzer2007). Supporting these racist policies was a clear construction of Asian Americans as coolies, a degraded race of “godless opium addicts, prostitutes, and gamblers” (Tichenor Reference Tichenor2007, p. 7). Since 1965, however, Asian immigrants have arrived in unprecedented numbers. In 2005, more than 12 million Asian Americans lived in the United States.

With the change in federal immigration policy, the dominant trope for Asian Americans has shifted dramatically from coolie to model minority. In “America's ‘Model Minority,’” Louis Winnick articulates the construction of a new “yellow peril,” one which is invading the corporations and gated communities of the United States:

The flood in recent decades of Asian immigrants to the U.S. was planned by no one, and would likely have been forestalled had a lingeringly racist Congress foreseen it…. This errant immigration policy, however, turned out to be a golden blunder, serendipity writ large. By inadvertence and over uncharted pathways, it brought to the United States millions of new workers, all with an unappeasable hunger for jobs and multitudes with eminently marketable skills, advanced education, and unbounded career ambitions (Winnick Reference Winnick1990, p. 22).

Though situated in an economic position 180 degrees from that of the day-laboring coolie, Asian Americans nevertheless remain racially marked and continue to be viewed as threatening. The change in the social construction of Asian Americans is striking in terms of both the attribution of qualities based on race, and the speed at which the transformation has occurred. How have Asian Americans gone from coolie to model minority in less than fifty years, and what are the consequences of this perceived transformation for racial identity?

Answers to these complex questions can be partial at best; I focus on two points in this article. First I examine the role of the state in creating policies that systematically select particular types of entrants to the United States. U.S. immigration policy privileges highly skilled workers in certain professions, as well as the family members of lawful permanent residents and U.S. citizens. Using U.S. Department of Homeland Security data from 2005, I document the composition of the population of recent immigrants awarded the status of lawful permanent resident (LPR), and disaggregate the data by both country of origin and class of admission. The data demonstrate that a disproportionately large number of Asian immigrants, relative to immigrants from other parts of the world, are granted the status of LPR by the federal government on the basis of employment preferences. In this respect, I shall argue, U.S. immigration policy creates a selection bias, favoring Asian immigrants with high levels of formal education and social standing. Model minority may be an accurate description of a selected set of Asians who successfully immigrated to the United States, but this description cannot be extended to characterize either Asian culture or Asian Americans in general; nor can it be applied in comparison to other minority groups with different trajectories of fortune.

Second, I examine the consequences of this selection bias for the construction of racial identity. Behavioral social scientists interested in political identity typically measure group affinity at the individual level. While few would dispute that identity is a social construction embedded in a large and complex system of interpersonal relations in broad social and political context, we often fail to consider the structural incentives and costs of adopting particular identities. Instead, we simply assume that people classified by race will readily adopt those identities. That assumption is in fact a hypothesis, albeit one that has received consistent support within the context of the African American political experience. At the same time, the extent to which Latinos and Hispanics, Asian Americans, and Afro-Caribbeans identify with the racial and ethnic categories imposed upon them provides less support for the notion that to be classified is to be identified. I argue that the normative content of the dominant tropes of racial identity is critical in establishing the incentives and costs of identifying with racial and ethnic groups. Immigration policy, and the selection biases it may engender, is an important factor in how those tropes are constructed and experienced. Racial identity should, and does, vary as a function of the unique histories of migration, labor market demands, and shared experiences for people classified by race. Studies in comparative and U.S. politics have documented the power of the state to construct racial identities (Hattam Reference Hattam, Foner and Fredrickson2004; King Reference King2000; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2003; Marx Reference Marx1998; Nobles Reference Nobles2000; Prewitt Reference Prewitt, Foner and Fredrickson2004; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2000; Smith Reference Smith1997, Reference Smith, Shapiro, Smith and Masoud2004; Zolberg Reference Zolberg2006). Any study of the politics of identity must, therefore, be informed by a careful examination of the context of racial hierarchy and its relationship to state policies.

Finally, the politics of racial identity cannot be effectively examined by considering a single group in isolation, because racial tropes may have been constructed in opposition to the dominant stereotypes for other groups (Kim Reference Kim1999, Reference Kim2000; Lee Reference Lee1999). While contemporary debate on immigration reform has important implications for all immigrant groups, the discourse on immigration policy reform has revolved substantially around the alleged imperative of controlling illegal immigration from Mexico and Latin America. Indeed, the problem of immigration reform has become nearly synonymous with the problem of illegal Latino immigration (Newton Reference Newton2008). Members of Congress need not even mention specific races or ethnicities, for it is clear that their discussion implicates Latinos. At the same time, new Americans from Asian nations make up one-quarter of the current population of the foreign born, and, while there are few sources of reliable data, far from all Asian immigrants reside legally in the United States. Yet the discourse of immigration reform rarely involves Asian Americans. Contemporary immigration policy has helped to create one of the defining stereotypes of Asian Americans as a “model minority,” but it has done so while simultaneously constructing racialized tropes for other immigrant and minority groups. In this regard, comparative analyses of the politics of racial identity will be most fruitful for understanding the dynamics of group consciousness among all Americans classified by race.

ASIAN AMERICANS AND U.S. IMMIGRATION POLICY

Until the late 1960s, Asian Americans were a novelty outside of Hawaii and states along the West Coast, numbering fewer than 1 million people across the United States. More than one hundred years of exclusionary practices targeting Asians kept the numbers low. Throughout the late nineteenth century, political arguments for keeping Asians out of the United States were unabashedly racist, though the political motives for Asian exclusion were more complex. Leland Stanford, cofounder of the Central Pacific Railroad and benefactor of Stanford University, used Chinese laborers to construct long stretches of what was to become the transcontinental railroad. But Stanford, who was also the eighth governor of California, included the following policy pronouncement in his Reference Stanford1862 inaugural address:

To my mind it is clear, that the settlement among us of an inferior race is to be discouraged, by every legitimate means. Asia, with her numberless millions, sends to our shores the dregs of her population…. There can be no doubt but that the presence of numbers among us of a degraded and distinct people must exercise a deleterious influence upon the superior race, and, to a certain extent, repel desirable immigration. It will afford me great pleasure to concur with the Legislature in any constitutional action, having for its object the repression of the immigration of the Asiatic races (Stanford Reference Stanford1862).

Under Stanford, California was the first state to enact anti-Asian legislation, and the federal government soon followed with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, culminating in across-the-board Asian exclusion with the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917, and the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924. As historian Andrew Gyory has argued,

After permanent renewal in the early 1900s, exclusion no longer appeared an aberration of traditional American policy; it became American policy, it became American tradition, and thus had repercussions for generations to come. The law's legacy, in the form of future restrictions and anti-Asian racism, lingers to this day (Gyory Reference Gyory1998, p. 258; see also Daniels Reference Daniels2004; Lee Reference Lee2003, Reference Lee, Foner and Fredrickson2004; Ngai Reference Ngai2004; Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002).

So much a part of the U.S. tradition was anti-Asian racial discrimination that, sixty years after the passage of the 1882 act, California Attorney General Earl Warren publicly provoked fear about the danger of Asian Americans of Japanese descent. Warren, who later become the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and presided during landmark cases on racial desegregation, was instrumental in locating, detaining, and interning Japanese Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Appearing in 1942 at a hearing before a special congressional committee on the Japanese question, Warren testified that the Japanese in California had the potential to threaten national security (Parrish Reference Parrish1982). In an odd twist of logic, Warren argued that the fact that no Japanese Americans had yet committed any disloyal act was proof that they intended to do so in the future. Warren had no evidence to support the inference, but at the time few required convincing that Japanese Americans were a menace.

The continued climate of anti-Asian discrimination is an important context as one considers the growth of the Asian American population in the United States. The U.S. Census Bureau began to enumerate Asians as a separate racial category in 1860 when the Chinese in California were first counted. In the subsequent census, the category was expanded to Japanese, and, starting with the 1910 census, additional categories, including Filipino and Korean, were added. Throughout the twentieth century, the U.S. Bureau of the Census altered the way it counted Asian Americans, resulting in inconsistent classifications over time.Footnote 2 Despite these irregularities, the patterns of growth in the Asian American population are clear. Table 1 presents data from the U.S. Census on the size of the Asian American population from 1790 to 2005. Throughout the hundred-year period between 1860 and 1959, the size of the Asian American population remained small, taking a jump in 1960 to coincide with the addition of Alaska and Hawaii and the elimination of national-origin and Asian-exclusion laws. The slow growth rate in the Asian American population throughout the first half of the twentieth century contrasted markedly with the heavy international migration of Europeans to the United States during this same period.

Table 1. Asian American Population in the United States, 1790–2005

The influence of Asian-exclusion immigration policies emerges most starkly in comparing the data for those from Asia versus those from other parts of the world who obtained the status of lawful permanent resident (LPR). As distinguished from the census enumeration data presented above, the data in Table 2 document the region of last residence before immigration to the United States for those individuals who obtained the status of LPR. The system of regional classification is determined by the federal government, and the source of the data is the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Table 2 disaggregates legal immigrants in terms of region of last residence for the period between 1820 and 2005; the data are presented for each decade between 1820 and 1999, and for the five-year period between 2000 and 2005. There are a number of interesting patterns in the data. The total number of immigrants obtaining lawful permanent residence in the United States varies directly with federal immigration law. Periods following restrictionist legislation show dips in the number of legal migrants, while progressive laws foreshadow a rise in the population of new Americans from abroad. The pattern of legal entrants by region of the world, however, is not uniform. Before 1850, nearly all immigrants awarded LPR status were from Europe, with a small proportion (5% of the total) coming from North America. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the pattern of migration from Europe continued. There was a steady increase in migration from North America (during this period, mostly from Canada) until 1889; and, during the period between 1870 and 1879, LPR status was awarded to more than 100,000 Asian immigrants. While this was a substantial increase from the previous decade and that to follow, the number of legal Asian immigrants nevertheless pales in comparison to the more than 2.2 million European migrants awarded LPR status between 1870 and 1879.

Table 2. Number of Immigrants Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status by Region of Last Residence, 1820–2005

Immigration surged throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century, when 19 million immigrants were awarded the status of LPR. The basic pattern of European dominance was complicated by substantial growth in migration from North America, primarily Canada. The regional category of “North America” includes Canada and Newfoundland, Mexico, the Caribbean (Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and others), along with Central America (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and others).

During this period, anti-Asian immigration policy and the state apparatus supporting it allowed only a trickle of Asian immigrants into the United States, and, of the nearly 28 million immigrants who obtained the status of LPR in the fifty-year period between 1880 and 1929, persons from the land mass defined as Asia made up just over 800,000.Footnote 3 In the ensuing two decades, and during the height of restrictionist policy against all racialized immigrants, just over 50,000 Asian immigrants were granted LPR status, as compared to over 1.5 million other new entrants, primarily from Europe and Canada.

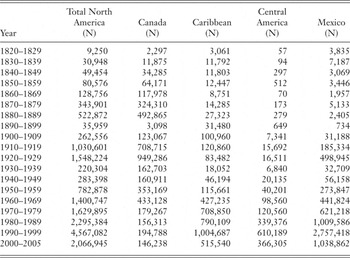

All immigration slowed between the 1930s and the 1950s, but when it picked up again in the 1960s, the patterns changed dramatically. In the decade following the 1965 Immigration Act, immigrants from North America and those from Asia outnumbered new entrants from Europe. Equally noteworthy is the change in composition among North Americans who received LPR status in the United States. Table 2A disaggregates this category into the areas of Canada, the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico for the period between 1820 and 2005. Nearly half a million immigrants from Mexico obtained LPR status between 1920 and 1929, but that number diminishes sharply for the next two decades, and does not reach similar levels until 1970. This growth occurs during the height of nativist power in the U.S. Congress, and, while the Immigration Act of 1924 created formidable obstacles for European immigrants—particularly from southern and eastern European countries—it left migration from North America open. In the ensuing years, immigrants from Mexico made up the largest number of migrants from North American nations receiving the status of LPR in the United States. Immigration from the Caribbean showed a more steady pattern of growth, from less than 50,000 in the 1940s up to more than a million in the 1990s. Standing at about half a million in the five years between 2000 and 2005, immigrants from the Caribbean today outnumber their Canadian counterparts by more than three to one.

Table 2A. Number of Immigrants Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status, North America, 1820–2005

The most important change in federal immigration policy for Asian Americans came with the 1965 Immigration Act. The number of Asian Americans awarded LPR status quadrupled in the decade following the passage of the law, and has increased every decade since. At its pace during the five years since 2000, immigrants from Asian countries are poised to grow by another 1.5 million by the end of 2010. Table 3 details the numbers of immigrants from Asia obtaining lawful permanent residence by decade during the period from 1850 through 1999 for the nations enumerated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.Footnote 4 Note that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security includes all nations of the continent of Asia in this category, including countries ordinarily classified as a part of the Middle East. The number of LPRs from Iran, Israel, Jordan, and Syria, however, is much smaller than that for East Asian and Southeast Asian nations, with high numbers from Iran in the decades following the Iranian revolution.

Table 3. Number of Immigrants Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status by Asian Country of Last Residence by Decade: FY 1850–1999

Not only have the numbers of Asian immigrants increased, but the composition of those migrants has also changed dramatically. In the early years of Asian migration during the 1850s, immigrants came from southern China, and mainly from the Guangdong province, where poverty and political turmoil pushed migrants toward international locations (Chan Reference Chan1986, Reference Chan1991). Until 1890, the Asian American population in the United States was almost entirely Chinese, fed briefly by the Burlingame Treaty (1868), which granted most favored nation status to China. This agreement was unilaterally suspended by the United States with the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and Japanese migration to the United States began in earnest around 1900. After the 1882 act went into effect, Chinese immigration to the United States dropped dramatically, while Japanese migration to the United States increased. Despite the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907, Japanese Americans were awarded LPR status until almost all Asian immigration was halted with the Asiatic Barred Zone Act (1917). Immigration from diverse locations in Asia was not sanctioned until the McCarran-Walter Act (1952) was passed, and did not begin in earnest until the 1960s. Once represented mainly by rural Chinese and Japanese migrants, the newest generation of immigrants came from a diverse set of sending countries. Indeed, immigration from Asia began to explode starting with the decade of 1960, when just over 350,000 Asian Americans became LPRs. During the following ten years, 1.4 million immigrants obtained government authorization to reside in the United States.

In the current period, the country of origin of immigrants from Asia varies, with the highest proportions arriving from India, China, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Korea. Table 3A documents, for each year between 2000 and 2005, the number of immigrants from countries classified as part of Asia by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. The size and composition of the contemporary population of Asian Americans awarded the status of LPR are determined in large part by federal immigration policy. There are a number of ways an immigrant can receive a green card, which provides both permanent residence and the legal right to work in the United States. The most common way is through sponsorship by a U.S. citizen of spouses, minor children, and parents.Footnote 5 Employment-based preferences are another avenue through which to obtain LPR, but the immigrant must have a permanent employment opportunity and the employer must be willing to sponsor the immigrant.Footnote 6 Refugee and asylee status is another category for LPR with no limit on the number of immigrants, and the number of LPR awarded in this category fluctuates by year. Roughly 50,000 immigrants can obtain LPR status in the United States through diversity programs, which are the result of a lottery system in which citizens from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States are allowed to participate. Finally, the registry provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act stipulates that people living in the United States since January 1972 can apply to be LPR even if they initially entered the country undocumented.

Table 3A. Number of Immigrants Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status by Asian Country of Last Residence Annually: FY 2000–2005

Table 4 details class of admission status for LPRs by region of birth for the fiscal year 2005. For each of the five major classes of admission—immediate relative, employment-based, family-sponsored, refugee and asylee, and diversity programs—along with the other category, which includes LPR status awarded through the registry program, the table presents the percentage from each of six regions of the world. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security categorizes these regions as Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America. Table 4A presents the data on class of admission for LPRs disaggregated for North America into the categories of Canada, the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico. In terms of the total number of LPRs admitted in 2005, 36% were from Asia, 31% from North America, 16% from Europe, 9% from South America, 8% from Africa, and 1% from Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). Disaggregating the North America data shows that immigrants from Mexico made up 14% of the LPR population in 2005, while immigrants from Caribbean nations received 10% of all green cards awarded that year. Immigrants from Central America obtained 5%, and Canadians 2% of all LPR awards. The admission category immediate relative of a U.S. citizen comprised the largest proportion (39%) of those who received LPR status in 2005. Following that were employment-based preferences (22%) and family-sponsored preferences (19%). Those immigrants receiving LPR status as refugees and asylees made up 13% of the 2005 LPR population, and diversity programs and registry immigrants made up 4% and 3%, respectively.

Table 4. Class of Admission for Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status by Region of Birth, FY 2005

Table 4A. Class of Admission for Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status, North America, FY 2005

Taken together, two clear conclusions can be drawn from the data. The first is that the proportion of immigrants who obtain LPR status from Asia relative to estimates of the size of the foreign-born population classified as Asian Americans is disproportionate in comparison to other groups, particularly those classified as Hispanic or Latino. Of the total number of immigrants awarded LPR status in 2005, 36% were from Asia, 14% from Mexico, and 5% from Central America. The Pew Hispanic Center has estimated that people born in South and East Asia made up about 23%, Mexicans made up 31%, and those born in countries in Central America made up 7% of the foreign-born population in 2005 (Pew Hispanic Center 2008). The discontinuity in the proportion of immigrants granted lawful residence in the United States in 2005 relative to their share of the foreign-born population hints at the distinctive trajectories of entry for immigrants from different parts of the world. Reflecting the immigration policy favoring skilled professionals, immigrants from the Asian continent granted LPRs have higher levels of education on average than do either LPRs from Mexico or Central America.Footnote 7 Asian Americans with LPR status are overrepresented in this category, for they make up a disproportionately large number of those awarded green cards on the basis of employment preferences. While Asian immigrants made up 36% of those awarded lawful permanent residence in 2005, they made up 53% of those who obtained LPR status on the basis of being a priority or skilled worker. Immigrants from locations in North America other than Canada, on the other hand, have a disproportionately low percentage of LPR status awarded through employment-based preferences. At the same time, and despite the financial and bureaucratic hurdles encountered in successfully applying for LPR status for family members, Asian Americans are not overrepresented in the category of immediate relatives or family-sponsored preferences. Indeed, immigrants from Mexico were awarded 31% of all family-sponsored preference green cards in 2005, despite making up 14% of the total LPR population in that year. Yet immigrants from Mexico and Central America remain underrepresented in terms of their share of LPR status relative to their proportion in the foreign-born population. Meanwhile, Asian Americans have incurred advantages from federal immigration policy on the basis of employment-based preferences. The preference system that prioritizes skilled workers with high educational attainment and work experiences thus creates a selection bias of entry for Asian immigrants awarded the status of LPR.

U.S. IMMIGRATION POLICY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACIAL IDENTITY

Federal immigration policy that creates preferences for some types of immigrants disproportionately awards the status of LPR to those who match those favored characteristics. While current U.S. policy provides green cards for purposes of family reunification, it also privileges legal entry for workers with high-level professional skills and advanced degrees. Immigration policy, geographic proximity or distance, the demands of the international labor market, economic development, and educational policy in individual nations combine to create the particular configuration of immigrants, both lawful and undocumented, in the United States today. The purpose of this article is to turn the spotlight on the power of state policy to create a class- and education-based selection bias among immigrants. Taking this one step further, I shall analyze the significance of this selection bias for the creation of racial tropes, and argue that these stereotypes have implications for the incentives and costs that people face when they identify with a racial or ethnic group. In addition to immigration policy, there are myriad other ways in which incentives for political action and consciousness manifest themselves, including the creation of legislative districts, the segregation of populations through housing and zoning laws, and the creation of bilingual programs. The role of state policies needs to be highlighted, not because it is necessarily the most important factor in the development of racial tropes, but because structural factors are often neglected in the study of racial and ethnic identity. Overlooking structural factors has led analysts to misascribe the success of Asian American immigrants, compared with other U.S. minorities, to cultural difference. Similarly, to assume that racial classification implies racial identification is to neglect the significance of distinctive normative tropes constructed around particular racial and ethnic groups.

Within the context of immigration policy, federal law has helped to reconfigure the meaning of Asian American in the United States. I have documented how these policies have manifested themselves in terms of the composition of the Asian American population, taking effect through the preference-based system, and resulting in a highly selected group of well-educated and skilled LPRs and their families. This is a dramatic change from the immigration policy of earlier periods, and a sharp contrast to the Asian-exclusion policies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I concur with immigration scholars and historians that the 1965 Immigration Act was not aimed at Asian Americans, but the employment-based preference and family-reunification categories nonetheless had the unintended consequences of dramatically increasing the size and composition of the Asian American population. In other words, federal policy has helped to recast the racial trope of Asian American from coolie to model minority.

While the selection bias argument seems obvious in light of the data, scholars and political commentators arrayed at various points along the ideological spectrum have focused on other explanations for the rapid movement of Asian Americans from a targeted and socially undesirable racial group to a model minority. Characteristics inherent to either Asian culture or values, or to genetic biological features, remain surprisingly persistent explanations for the phenomenon. While wildly unpopular in many circles, the perspective of genetic similarity theory continues to resonate, feeding stereotypes of Asian Americans as naturally talented at math and scientific reasoning (Rushton Reference Rushton1995). Samuel Huntington heralds the “Whitening” of Asian Americans and predicts their rapid assimilation:

Even more dramatically than previous European ethnic groups, Asian Americans are “becoming white,” not necessarily because their skin color is whitening, although it is, but because they have, in varying degrees for different groups, brought with them values emphasizing work, discipline, learning, thrift, strong families, and in the case of Filipinos and Indians a knowledge of English. Because their values are similar to those of Americans and because of their generally high educational and occupational levels, they have been relatively absorbed into American society (Huntington Reference Huntington2004, p. 298).

Observers from the political right are not the only ones to have made the claim that Asian Americans are “becoming White.” There is more than a passing similarity to Huntington's story in the case that legal scholar Ian Haney-López makes for labeling Asian Americans as honorary Whites:

In the United States, honorary-white status seems increasingly to exist for certain people and groups. The quintessential example is certain Asian-Americans, particularly East Asians. Although Asians have long been racialized as nonwhite as a matter of law and social practice, the model-minority myth and professional success have combined to free some Asian-Americans from the most pernicious negative beliefs regarding their racial character. In part this trend represents a shift toward a socially based, as opposed to biologically based, definition of race. Individuals and communities with the highest levels of acculturation, achievement, and wealth increasingly find themselves functioning as white, at least as measured by professional integration, residential patterns, and intermarriage rates (Haney-López Reference Haney-López2006a, p. 4).

Whether or not, and the extent to which, the racial trope of the model minority for Asian Americans has been emancipatory remains controversial. Nevertheless, and within the context of the developmental argument offered above, the contemporary racial trope of model minority for Asian Americans is far from uniformly positive. Indeed, the construction of Asian Americans as a model minority works in tandem with another common characterization of Asians as perpetual foreigners (Ancheta Reference Ancheta1998; Kim Reference Kim1999; Lee Reference Lee1999; Lowe Reference Lowe1996; Saito Reference Saito1998; Tuan Reference Tuan1998; Ueda Reference Ueda, Keller and Melnick1999). Similarly, it is clear that the economic and educational advantages widely attributed to Asian Americans by the model-minority stereotype are not shared by all those grouped in the same racial category (Kwong Reference Kwong1987). The distribution of income and educational resources is bimodal within the diverse population of Asian Americans in the United States, reflecting important and often overlooked groups of immigrants and native-born Asian Americans who exist far away from the advantages of the status of an honorary White. Indeed, the fact that racialized stereotypes categorize is itself an expression of their political power, with the readily identifiable phenotypic characteristics of many Asian Americans acting as visible markers of difference. Model minority is clearly a more positive racialized trope than coolie, but it is not without negative consequence. Historians have documented the popular depiction of immigrant Chinese laborers in the late nineteenth century as coolies (Chan Reference Chan1991; Miller Reference Miller1969; Mink Reference Mink1986; Ngai Reference Ngai2004; Saxton Reference Saxton2003; Smith Reference Smith1997; Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002). Most striking in drawing the comparison across time between the coolie and the model minority tropes is the image of Asian Americans as machines.Footnote 8 In Civic Ideals, Smith writes about the debate over the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act:

California Senator John Miller claimed that over “thousands of years,” the “dreary struggle for existence” had led to the “survival” of Chinese workmen who were in some ways “fittest” because they were “automatic engines of flesh and blood” (Smith Reference Smith1997, p. 360).

Once a machine utilized for railroad pile driving, immigrant Asians are now cast as human calculators, programmed to spend every waking hour nose to the grindstone, whether in front of the computer screen or behind the cash register. To be sure, there are positive aspects of the model minority trope for Asian Americans that are apparent both to those who use the stereotype as a compliment, and to those Asian Americans who adopt and internalize the identity. But the stereotypes are at once distinct and dehumanizing. This is complex territory, but the simple take away in drawing the line from coolie to model minority is that Asian Americans remain racialized, distinctive, and threatening. Canadian and European immigrants today come with similar skills and education levels as those of Asian immigrants, but commentators do not fret over their “unappeasable hunger for jobs” in the same way that Winnick described his fear of the “golden blunder” of an “errant immigration policy” (Winnick Reference Winnick1990, p. 22).

Taken alone, the story of the development of racial tropes of Asian Americans over time might end with the keen observation of a selection bias structured by U.S. immigration policy. The data on LPRs by region of birth from 2005 show that green cards have been awarded disproportionately to immigrants from Asian nations, not only relative to their proportion of the resident foreign-born population, but also as a function of employment-based preferences. Asians are portrayed as high-achieving and highly skilled professionals, fittingly described as the “model minority.” In contrast, immigrants to the United States from Latin America have been disadvantaged by federal immigration policy. Constructed as low-skilled workers and unlawful migrants, Latinos face a distinctive set of racialized tropes. Immigration policy creates different incentives for Latinos and Hispanics than for Asian Americans to adopt a racial and ethnic group consciousness, by systematically selecting the labor force population from these two parts of the world. The extent to which Latinos and Asian Americans express a sense of racial identity thus depends in part upon the policies and actions of the nation that emerge when these groups are compared to one another (Wong Reference Wong2006; Junn and Masuoka, Reference Junn and Masuokaforthcoming).

This analysis has attempted to highlight the importance of history, federal immigration policies, context, and the unique experiences and constructions of race for immigrants. Identities are not constructed in a vacuum; instead, the normative claims attached to racial tropes create substantial room for people classified by race to be able either to adopt or to opt out (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, Reference Bronfenbrenner and Ceci1994; Phinney Reference Phinney2005). Just as there is a different dynamic involved in showing oneself to be a Yankee fan in Boston as opposed to New York, the context is also distinctive for the fan of any team heading to the play-offs rather than sitting at the bottom of the league. Of course, racial categories have far more tangible consequences for immigrants than do sports championships for fans. Racial identity should and does differ for major racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Unique histories of migration, labor market demands, and class present particular circumstances and experiences for people classified by race. The state has the power to make race, and the state's actions may be arbitrary and irrational. But the construction of racial categories is almost always driven by the demands of capital, and shaped by the psychology of power, dominance, and ignorance. While not omnipotent, the state is nevertheless among the most important factors in the creation and maintenance of racial categories and hierarchy. We must recognize the government's role in the politics of identity and political mobilization in order to be able to take aim at particular national practices and federal institutions as we attempt to dismantle the mechanisms of structural inequality.