Introduction

Since DSM-III, the presence of environmental stressors has been factored into an individual's psychiatric evaluation through Axis IV of DSM's multi-axial system (Williams, Reference Williams1985a). According to DSM-IV (Table 1), ‘Axis IV is for reporting psychosocial and environmental problems that may affect the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of mental disorders’ (DSM-IV, p. 31). The problems that are relevant for reporting on Axis IV include those problems that might be etiologically relevant to the disorder (e.g. as precipitants of the current episode), in addition to those that are relevant to the future course of the disorder. Although DSM-IV limits the problems that should be reported on Axis IV to those that have occurred within the past year, problems prior to the past year may also be reported if they are clearly relevant to the current disorder.

Table 1. Axis IV: Psychosocial and Environmental Problems

Source: Reproduced from DSM-IV-TR, p. 31.

It is unclear what role Axis IV currently plays in clinical practice (Skodol, Reference Skodol1997), and the evidence for maintaining Axis IV is scant. We have been unable to identify any empirical investigations of the validity or clinical utility of the DSM-IV version of Axis IV. In DSM-III and DSM-III-R, Axis IV was formulated as a rating scale of the severity of psychosocial stressors (Moncur & Luthra, Reference Moncur and Luthra2009). The reliability and validity of that rating scale were evaluated, with mixed results (Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Pfohl, Stangl and Coryell1985; Plapp et al. Reference Plapp, Rey, Stewart, Bashir and Richards1987; Rey et al. Reference Rey, Plapp, Stewart, Richards and Bashir1987a, Reference Rey, Stewart, Plapp, Bashir and Richardsb, Reference Rey, Stewart, Plapp, Bashir and Richards1988; Skodol & Shrout, Reference Skodol and Shrout1988, Reference Skodol and Shrout1989a, Reference Skodol and Shroutb). For example, with respect to its predictive validity, Zimmerman et al. (Reference Zimmerman, Pfohl, Coryell and Stangl1987) found that, among patients hospitalized for depression, higher scores on the Axis IV rating scale were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms at hospital discharge but were unrelated to their depression outcomes after 6 months of follow-up.

Axis IV in its current formulation delineates nine categories of ‘psychosocial and environmental’ problems that should be documented as part of a patient's diagnostic evaluation: problems with primary support group, problems related to the social environment, educational problems, occupational problems, housing problems, economic problems, problems with access to health-care services, problems related to interactions with the legal system/crime, and other psychosocial and environmental problems. In theory, information regarding these problems should aid in the development of treatment plans and in the identification of potential barriers to treatment adherence (Moncur & Luthra, Reference Moncur and Luthra2009). The clinical utility of Axis IV, as Zimmerman et al. (Reference Zimmerman, Pfohl, Stangl and Coryell1985, p. 1440) noted, ultimately ‘rests with its relation to prognosis’.

Evidence from clinical samples suggests that environmental stressors such as those indicated on Axis IV are predictive of depression relapse. For example, social support problems were predictive of poor treatment outcomes (i.e. lack of full remission) in an out-patient sample being treated for depression (Ezquiaga et al. Reference Ezquiaga, Garcia, Pallares and Bravo1999). Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Harris, Kendrick, Chatwin, Craig, Kelly, Mander, Ring, Wallace and Uher2010) reported that exposure to serious life events was associated with worse depression outcomes, and Monroe et al. (Reference Monroe, Torres, Guillaumot, Harkness, Roberts, Frank and Kupfer2006) and Lenze et al. (Reference Lenze, Cyranowski, Thompson, Anderson and Frank2008) reported worse depression outcomes in the context of non-severe life events. It is unclear whether these findings extend to non-clinical samples.

We address two issues of concern regarding Axis IV that have specific relevance to depression. First, does the presence of psychosocial problems predict the prognosis of depression? Second, is there evidence for the validity of the taxonomy of psychosocial and environmental problems outlined in DSM-IV? This study is based on a population-based sample of individuals with depression and followed prospectively for 3 years. We investigate whether and which types of psychosocial problems at baseline predict depression prognosis during the follow-up period. In addition to examining DSM-IV's taxonomy of psychosocial stressors listed above, we apply latent class analysis (LCA) to an inventory of life stressors in the past year to evaluate the predictive validity of an empirically derived taxonomy of stressors. Finally, we conduct comparative analyses of a broader range of anxiety and substance use disorders to evaluate the utility of Axis IV beyond the diagnosis of major depression.

Method

Sample

Data come from the National Epidemiology Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a two-wave, nationally representative household survey (Hasin et al. Reference Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson and Grant2005). The Wave 1 sample included 43 093 adult participants. The Wave 2 survey, conducted approximately 3 years later, included 34 653 of the 39 959 Wave 1 participants eligible for follow-up. The combined response rate for both waves was 70.2% (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Goldstein and Grant2007). The primary analytic sample for the current study included participants with a diagnosis of major depressive episode (MDE) in the 12 months preceding the Wave 1 interview who were followed up at Wave 2, and who provided complete data on all study covariates. Secondary analyses were conducted among participants with any mood, anxiety or substance use disorder in the 12 months preceding the Wave 1 interview who were followed up at Wave 2.

Measures

Past-year MDE was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS; Grant & Dawson, Reference Grant and Dawson2001; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Dawson, Stinson, Chou, Kay and Pickering2003). The AUDADIS algorithm for MDE requires ⩾5 clinically significant symptoms of depression occurring during a 2-week period of sadness or anhedonia (Hasin et al. Reference Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson and Grant2005). The test–retest reliability of depression diagnoses over a period of 2–3 months was good (κ = 0.65 for a lifetime diagnosis of major depression and 0.59 for a past-year diagnosis) (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Dawson, Stinson, Chou, Kay and Pickering2003). The following features of depression assessed at Wave 1 were also included in the analyses: number of DSM-IV criterion ‘A’ symptoms of MDE; level of impairment, defined as the number of the NESARC's eight impairment items related to depression that were endorsed; and number of lifetime depressive episodes.

We investigated two outcomes of depression assessed at the Wave 2 follow-up interview. The first was the presence of any depressive episode during the follow-up period. The second was any suicidal thoughts or attempts during the follow-up period. Suicidal thoughts were assessed at Wave 2 from participants who reported either 2 weeks of depressed mood or loss of interest since the Wave 1 interview, and suicidal attempts were assessed from all Wave 2 participants. We also investigated the role of psychosocial stressors in predicting episodes of the following disorders during the NESARC's follow-up period: social phobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol dependence and substance dependence.

The presence or absence of the following psychosocial and environmental problems in the 12 months prior to the Wave 1 interview were assessed: (1) death of a close friend or family member; (2) serious illness or injury of a close friend or family member; (3) separation, divorce or end of a serious relationship; (4) serious problems with a neighbor, friend or relative; (5) being fired or laid off; (6) currently unemployed or unemployed for >1 month during the past year; (7) trouble with boss or co-worker; (8) change of jobs, responsibilities or work hours; (9) experienced a major financial crisis, declared bankruptcy or more than once been unable to pay bills on time; (10) household income <150% of the federal poverty threshold; (11) received public assistance (e.g. welfare, food stamps); (12) lack of health insurance; (13) trouble with the police, arrested or sent to jail; and (14) victim of a crime. The test–retest reliability of the NESARC's assessment of stressful life events over a 6-week period was excellent (intra-class correlation = 0.94) (Ruan et al. Reference Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Smith, Saha, Pickering, Dawson, Huang, Stinson and Grant2008).

We analyzed these 14 indicators of psychosocial and environmental problems in the following two ways. First, we grouped them into the categories of stressors outlined in the description of Axis IV in DSM-IV. The categories were: problems with primary support group (problems 1–3), problems related to the social environment (problem 4), occupational problems (problems 5–8), economic problems (problems 9–11), problems with access to health-care services (item 12), and problems related to interaction with the legal system/crime (problems 13 and 14). There were three categories of problems outlined in DSM-IV that we could not assess: educational problems, housing problems and a generic category of ‘other’ psychosocial problems.

Second, we used LCA to derive empirically based groupings of individuals based on their experiences of the above 14 stressors (McCutcheon, Reference McCutcheon1987). In LCA, correlations among the observed dependent variables (the 14 stressors) are related to a categorical latent variable through a set of logistic regression equations. The number of categories is determined by fitting multiple LCA models and then selecting the best-fitting model using summary statistics of model fit. The results of the LCA were used to assign each individual to a specific class, which was used as a predictor of depression course. The LCA was implemented in Mplus, with adjustments made for the complex sampling design of the NESARC (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–Reference Muthén and Muthén2010).

We also analyzed childhood adversities to evaluate the relevance to Axis IV of stressors that occurred prior to the current depression. These were assessed retrospectively at the Wave 2 interview (Benjet et al. Reference Benjet, Borges and Medina-Mora2010; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Caldwell, Power and Stansfeld2010; Salum et al. Reference Salum, Polanczyk, Miguel and Rohde2010). The childhood adversities included standardized indices of childhood abuse (including neglect, verbal abuse and physical abuse) and sexual maltreatment and a dichotomous indicator of childhood economic deprivation. Abuse and maltreatment during childhood were assessed through a series of items asking participants about their frequency of exposure to different types of adversities, which they rated on a five-point scale anchored by ‘Never’ and ‘Very Often.’ The test–retest reliabilities of these childhood adversities in the NESARC are excellent, with intra-class correlations ranging from 0.80 to 0.94 (Ruan et al. Reference Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Smith, Saha, Pickering, Dawson, Huang, Stinson and Grant2008). Childhood economic deprivation was defined as receiving government financial assistance before age 18 years.

Additional adjustment factors that we included in the analyses were co-occurring anxiety (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder or social phobia) and substance (alcohol or substance dependence) disorders, and participant demographic factors (age, sex, educational attainment and race/ethnicity). These factors were included in the analyses because they are known to be associated with stressful life events and psychopathology, and could therefore be potential confounding variables.

Analysis of depression outcomes and other psychiatric disorders during the follow-up period

The study design involved fitting Poisson regression models for a depressive episode and for suicidal thoughts or attempts occurring between the Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews. This model yields regression coefficients that, when exponentiated, can be interpreted as prevalence ratios (PRs) (Zou, Reference Zou2004). For each outcome, we fitted models that included the DSM-IV categories of the psychosocial and environmental problems (with and without adjusting for past-year co-morbid disorders, indicators of depression severity and childhood adversities), and models that included the stress exposure groupings from the LCA. The descriptive analyses and the Poisson regression analyses were conducted in SUDAAN, which adjusts variances and point estimates for the multi-stage sampling design and differential selection probabilities used to ascertain the NESARC sample (SUDAAN, 2004). Percentages are weighted using the study's Wave 2 sampling weights; actual sample sizes are reported.

Results

The prevalence of past-year depression in the NESARC sample at baseline is 7.9% (n = 3485). Among these individuals, 2497 (73.4%) participated in the follow-up interview and had complete data on all variables included in the present study, and therefore constitute the primary analytic sample. The analysis sample is predominantly female (66.6%) and White (74.4%). One-third of the sample enrolled were between ages 18 and 29 years (30.3%) and approximately half of the sample (54.7%) had at least some college education. Two-fifths of the sample had a depressive episode during the follow-up period (39.5%, n = 1002). Most of these individuals (93.2%, n = 944) had at least one recurrent episode, meaning that they experienced the onset of a new depressive episode following >2 months of improved mood and resolution of accompanying symptoms. Almost one-fifth of the sample reported suicidal thoughts or attempts during the follow-up period (16.4%, n = 419).

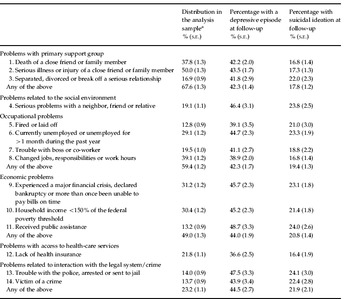

The distribution of psychosocial and environmental stressors at baseline is presented in Table 2. The first column presents the distribution of each stressor in the analysis sample. Support group problems were fairly common, with half the sample reporting a serious illness or injury of a close friend or family member. Economic problems were somewhat less common, with approximately one-third of the sample reporting a major financial problem or a household income <150% of the poverty threshold. The second and third columns indicate the associations of each stressor with the likelihood of a depressive episode (second column) and suicidal thoughts or attempts (third column) during the 3-year follow-up period of the NESARC. Compared to the risks of depression (39.5%) and suicidal thoughts or attempts (16.4%) in the sample overall, risks of depression were elevated among those reporting economic and legal problems (ranging from 44% to 49%), and risks of suicidal thoughts or attempts were elevated among individuals reporting social, economic and legal problems (ranging from 20% to 24%).

Table 2. Distribution of psychosocial and environmental problems among participants with a diagnosis of MDE at the baseline interview of the NESARC, and who participated in the 3-year follow-up interview

MDE, Major depressive episode; NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; s.e., standard error.

a Analysis sample includes n = 2497 participants with major depression who were reinterviewed at follow-up, and with complete data.

b Proportion with major depression during the follow-up period, 39.5% (n = 1002).

c Proportion with suicidal thoughts or attempts during the follow-up period, 16.4% (n = 419).

Risks for a depressive episode during the NESARC's follow-up period are presented in Table 3. Three models were fitted: model 1 for each category of stressor, model 2 adding in childhood adversities, and model 3 adding co-morbid anxiety and substance disorders, and indicators of depression severity (e.g. number of symptoms, level of impairment, number of lifetime episodes). The categories of stressors that were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with a depressive episode in the first model were problems with social support group [PR 1.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04–1.34], occupational problems (PR 1.15, 95% CI 1.00–1.32) and economic problems (PR 1.15, 95% CI 1.00–1.33). The association between social support group problems and recurrent depression remained in the second and third models that controlled for childhood adversities and clinical control variables (PR 1.17, 95% CI 1.04–1.32). In the final model adjusting for all covariates (model 3), higher scores on the childhood adversity index (PR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03–1.11) were also associated with recurrent depressive episodes during the follow-up period.

Table 3. Psychosocial and environmental predictors of a Wave 2 depressive episode during the 3-year follow-up period of the NESARC

NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Additional control variables not shown: age at enrollment, sex, educational attainment and race/ethnicity.

b Additionally controlling for prior anxiety and substance disorders, the number of criterion ‘A’ depressive symptoms, level of impairment, and number of lifetime depressive episodes.

A similar set of models was fitted for suicidal thoughts or attempts during the follow-up period (Table 4). Three categories of stressors were initially predictive of suicidal thoughts or attempts: social or environmental problems (PR 1.30, 95% CI 1.01–1.67); occupational problems (PR 1.34, 95% CI 1.04–1.72); and economic problems (PR 1.39, 95% CI 1.09–1.79). These associations were attenuated slightly when childhood adversities were added in model 2, and were more substantially reduced when co-morbid anxiety and substance disorders and indicators of depression severity were added in model 3. In the final analysis, the only psychosocial predictor of suicidal ideation during the follow-up period was the childhood adversity index (PR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.18).

Table 4. Psychosocial and environmental predictors of suicidal ideation assessed at the 3-year follow-up interview of the NESARCa

NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Additional control variables not shown: age at enrollment, sex, educational attainment and race/ethnicity.

b Additionally controlling for prior anxiety and substance disorders, the number of criterion ‘A’ depressive symptoms, level of impairment, and number of lifetime depressive episodes.

The results presented thus far are based on DSM-IV's ‘taxonomy’ of psychosocial and environmental problems. Using an empirically based approach to classifying stressors revealed stronger risks for poor prognosis in this sample. There were two parts to this analysis: first, an LCA of the 14 stressors to extract latent classes of stress exposure (which demarcate groups of individuals with distinct patterns of stress exposure), and second, using group membership to predict psychiatric outcomes.

The best-fitting LCA model of the 14 stressors had five latent classes. This is based on the entropy statistic (0.71), a measure of overall classification; the sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (BIC) statistic, which had trivial reductions after adding six or more classes; and the Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin (VLMR) likelihood ratio test statistics, which rejected a four-class model in favor of a model with five classes but failed to reject a model with five classes relative to a model with six classes (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–Reference Muthén and Muthén2010).

The results of the LCA are shown in Fig. 1, displayed across two panels for ease of interpretation. Each line represents a distinct class and each point along the graph indicates the probability of stressors in each class. The interpretation of the LCA solution is as follows. In Panel 1, Class 1 is characterized by a low probability of exposure to all 14 stressors (‘low stress exposure’). Class 2 differs from class 1 only with respect to stressors 1 and 2 – death or serious illness of a close friend or family member (‘personal loss’). Class 3 is characterized by a high probability of exposure to stressors 8 (job change) and 9 (major financial crisis), and is the class with the highest probabilities of exposure to stressors 13 and 14 (trouble with police, arrested or jailed, victim of a crime). We therefore label class 3 as ‘financial and interpersonal instability.’ In Panel 2, classes 4 and 5 are shown; these two classes represent two distinct patterns of exposure to economic and occupational stressors. Class 4 is characterized by high probabilities of stressors 10 and 11 (poverty and receipt of public assistance); by contrast, class 5 is characterized by a high probability of stressors 5, 6 and 8 (fired/laid off, unemployed and changed jobs). We therefore label class 4 as ‘economic difficulty’ and class 5 as ‘occupational instability.’

Fig. 1. Results of the latent class analysis (LCA) of 14 psychosocial and environmental problems. Each line represents one of five latent classes of stress exposures. The average probability of endorsing each stressor among participants in each latent class is shown. The proportion of participants in each class is: 19.3% in class 1 (n = 488); 25.2% in class 2 (n = 636); 43.1% in class 3 (n = 1199); 8.8% in class 4 (n = 304); and 3.7% in class 5 (n = 99).

It is notable that some of the stressors had a high frequency in more than one class. What differentiates the classes from one another is the broader pattern of concomitant stressors. For example, changing jobs was common in classes 3 and 5. Individuals in class 3 also had a high likelihood of problems with the police and of being the victim of a crime whereas those in class 5 had a very low frequency of these stressors. By contrast, individuals in class 5 had a much higher likelihood of having been fired and of experiencing an extended period of unemployment.

The LCA generates a set of predicted probabilities of class membership; we used these predicted probabilities to assign each individual to their most likely class, and then used class membership to predict suicidal thoughts or attempts and depressive episodes during the follow-up period (Table 5), and other mood, anxiety and substance disorders (Table 6). The unadjusted proportions of depressive episodes and suicidal ideation across latent classes are shown in the first column of Table 5, followed by PRs comparing the risk of suicidal ideation and depression between individuals in classes 2–5 relative to class 1. In models predicting depressive episodes during the follow-up period, individuals in the classes characterized by personal loss, financial/interpersonal instability and economic difficulty were all at significantly greater risk than individuals in the low-stress exposure class (PR 1.27, 1.33 and 1.52 respectively). A history of childhood adversity was also associated with the prognosis of major depression (PR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03–1.11).

Table 5. Psychosocial and environmental predictors, based on LCA, of depressive episodes and suicidal ideation during the 3-year follow-up period of the NESARCa

LCA, Latent class analysis; NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; s.e., standard error; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve.

a Additional control variables not shown: age at enrollment, sex, educational attainment and race/ethnicity.

b Additionally adjusted for anxiety and substance disorders, the number of criterion ‘A’ depressive symptoms, level of impairment, and number of lifetime depressive episodes.

Table 6. Psychosocial and environmental predictors, based on LCA, of anxiety and substance use disorders during the 3-year follow-up period of the NESARCa

LCA, Latent class analysis; NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; s.e., standard error; PR, prevalence ratio.

a Analyses in this table included data from participants in NESARC with any of the disorders listed at Wave 1 (n = 7364). Unadjusted proportions shown in the top panel; results of regression analyses shown in the bottom panel, adjusted for: age at enrollment, sex, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, childhood adversities, and the presence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders at Wave 1.

b Reduced model omits controls for prior psychiatric history at Wave 1, indicating the predictive value of the model containing only latent classes of past-year stressors, childhood adversities, and demographic factors.

Consistent with the analyses reported in Table 4, associations between past-year stressors and suicidal ideation in model 1 were attenuated after controlling for childhood adversities (in model 2) and clinical control variables (in model 3). Higher levels of childhood adversity were independently associated with the risk of suicidal ideation during the follow-up period (PR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.18).

The ability of the latent class categories to predict 3-year risks of suicidal ideation and depression can be quantified by the AUC statistic; that is, the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. An AUC value of 0.5 indicates prediction no better than chance, and a value of 1.0 indicates perfect prediction. The AUC statistics for suicidal ideation and recurrent depressive episodes ranged between 0.63 and 0.72 (last row of Table 5). This degree of prediction could be characterized as modest, but falls in the same range as validated prediction models for physical health outcomes (e.g. 0.70 for the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction score; D'Agostino et al. Reference D'Agostino, Grundy, Sullivan and Wilson2001; Wilson, Reference Wilson2009).

Finally, we conducted comparative analyses of the association between latent class membership and episodes of anxiety and substance use disorders during the NESARC's follow-up period (Table 6). The sample for these analysis comprised individuals of any of the following disorders without complete data on Wave 1 covariates who also participated at Wave 2 (n = 7364). The most consistent finding across disorders involved financial and interpersonal instability. Individuals in this latent class had elevated risks of generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol dependence and substance dependence during the follow-up period (PRs ranging from 1.11 to 1.45). Participants in the economic difficulty class had significantly higher risks of panic disorder (PR 1.55) and substance dependence (PR 1.19) during the follow-up period. Psychosocial and environmental problems were unrelated to social phobia during the follow-up period. The AUC statistics for these disorders are presented in the last two rows of Table 6. In the fully adjusted model for each (i.e. the model from which the PR's were obtained), AUCs ranged from 0.73 to 0.81. We present AUC statistics from a reduced model in the final row; the reduced model removed the clinical control variables, with the resulting AUC statistics providing an indication of the prognostic value of the psychosocial stressors and demographic factors alone (i.e. before accounting for prior psychiatric history). These AUC statistics ranged from 0.64 to 0.70, indicating that past-year and lifetime stressors have significant prognostic value for ongoing psychopathology.

Discussion

One of the purposes of introducing a multi-axial system of classification into DSM-III was to incorporate into the diagnostic evaluation information on clinical features of a disorder beyond the diagnosis that are important for treatment planning (Rutter et al. Reference Rutter, Lebovici, Eisenberg, Sneznevskij, Sadoun, Brooke and Lin1969; Strauss, Reference Strauss1975; Williams, Reference Williams1985a). Even at the time that DSM-IV was published, Skodol (Reference Skodol1997) commented, ‘It seems reasonable to conclude that a thorough evaluation of Axis IV has yet to be done’. In the years since, we have found no studies that have conducted such an evaluation.

We therefore sought to determine the usefulness of Axis IV in the diagnostic evaluation of major depression. We investigated whether or not psychosocial and environmental stressors were predictive of depression prognosis, indicated by recurrent depressive episodes and suicidal ideation in a nationally representative follow-up study of individuals with depression. Our results support the prognostic value of past-year and childhood psychosocial and environmental stressors in the longitudinal course of major depression. Childhood stressors were also associated with the risk of suicidal ideation among individuals with depression; however, past-year stressors did not predict suicidal ideation independently from other indicators of depression severity. We conclude from these results that the presence of psychosocial and environmental stressors should be maintained as part of the diagnostic evaluation in a multi-axial diagnostic classification.

Limitations

The NESARC's assessment of psychosocial stressors is subject to the limitations that adhere generally to checklist-type measures of stressful life events. These include the problem of intra-category variability; as defined by Dohrenwend (Reference Dohrenwend2006, p. 479), the problem is that ‘the actual experiences that lead a respondent to make a positive response to a given checklist category vary greatly’. Relatedly, the NESARC's assessment of stressors does not provide information on the meaning of the individual stressors to the participants. In prior research the relationship between stressors and depressive episodes has been found to be contingent on the stressors' psychological impact. For example, Kendler et al. (Reference Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner and Prescott2003) demonstrated that stressors most strongly related to depressive episodes were those that evoked feelings of loss and humiliation. The NESARC's assessment of stressors did not make these distinctions, and also did not determine whether some items on the checklist (e.g. job change) might have had both positive and negative mental health effects depending on the individual circumstances.

Axis IV does not posit specific dimensions of stressors that are important for the clinical course of disorders. In part, then, these limitations of the NESARC's assessment of stressors are also limitations of Axis IV. There exists a substantial evidence base to support the development of a more sophisticated Axis IV, one that would go beyond the simple presence or absence of events and incorporate both the nature of the stressors and the context in which they occur. This might include distinguishing chronic from acute stressors, and identifying stressors that impact an individual's core identity or that individuals appraise as highly disruptive (Shrout et al. Reference Shrout, Link, Dohrenwend, Skodol, Stueve and Mirotznik1989; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999, Reference Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner and Prescott2003; Hettema et al. Reference Hettema, Kuhn, Prescott and Kendler2006; Hammen et al. Reference Hammen, Kim, Eberhart and Brennan2009). A related issue that is anticipated by Axis IV is the role of psychiatric disorders in generating stressors. In these instances, the stressors would not have been a contributing cause of the disorder but may still be associated with the risk of recurrent episodes.

An additional limitation is that we could not conduct analyses to distinguish the separate associations of stressors with episode duration, remission and recurrence. Data from population-based studies indicate that the majority of depressive episodes remit within a period of months, and almost all within 2 years (Spijker et al. Reference Spijker, de Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen2002; Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, Shao, Nestadt, Lee, Bienvenu and Zandi2008; Furukawa et al. Reference Furukawa, Fujita, Harai, Yoshimura, Kitamura and Takahashi2008). This time frame exceeds the duration of the NESARC's follow-up period. Consistent with this evidence, 93.2% of depressive episodes reported during the follow-up period were recurrences. Our results therefore pertain directly to the role of stressors in depression recurrence and not the role of stressors in prolonging the time to recovery. Future work in samples with more fine-grained temporal resolution is needed to assess differences in risks for episode persistence and remission. Finally, whereas suicide attempts were assessed from all NESARC participants at the follow-up assessment, suicidal thoughts were assessed only from participants who also reported either depressed mood or loss of interest. Therefore, our measure of suicidal ideation may have missed suicidal thoughts that occurred outside of the context of depression.

Conclusions

The presence of environmental stressors may play a role in worsening the prognosis of depression and other types of psychopathology. Plausible explanations for this are that: (1) stressors themselves endure over time, generate future stressors, and heighten one's vulnerability to the effects of stress on psychopathology (Post et al. Reference Post, Rubinow and Ballenger1986; Safford et al. Reference Safford, Alloy, Abramson and Crossfield2007; McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen and Gilman2010); and (2) psychosocial stressors reduce the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Houck, Szanto, Dew, Gilman and Reynolds2006, Reference Cohen, Gilman, Houck, Szanto and Reynolds2009). Treatment plans that address the presence of social adversity may therefore be more effective at improving the long-term course of the disorder (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Harris, Kendrick, Chatwin, Craig, Kelly, Mander, Ring, Wallace and Uher2010).

Further work is needed to evaluate the validity of DSM-IV's taxonomy of psychosocial and environmental problems. Stressors categorized according to DSM-IV had statistically significant associations with depression prognosis and with suicidal thoughts or attempts, but these associations were modest in magnitude (i.e. PRs indicating 20% elevations in future risk). However, our empirically based taxonomy of stressors identified subgroups of individuals who had much more pronounced elevations in future risk; for example, approximately 50% higher risks of a recurrent depressive episode. The results of the ROC analyses conducted suggest that the psychosocial and environmental stressors identified have prognostic value in terms of predicting recurrent episodes. These results also suggest that the presence of individual types of stressors may be of less prognostic value than the overall constellation of stressors experienced by an individual. This is because the latent classes, which summarize broad patterns of stressors to which an individual is exposed, were more strongly predictive of depression recurrence that individual stressors. We note that Chapter XXI of the ICD-10 describes a much broader range of psychosocial stressors than DSM-IV (WHO, 2007), and that the ICD-10 taxonomy is being considered for adoption by DSM- 5 (APA, 2010). However, we are not aware of evidence to support the validity of the ICD-10 taxonomy.

An additional finding of our study is that childhood stressors were predictive of the course of adult depression. This finding is consistent with studies demonstrating an association between childhood adversity and adult psychopathology (McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen and Gilman2010; Slopen et al. Reference Slopen, Fitzmaurice, Williams and Gilman2010). Fewer studies have examined associations between childhood adversity and the course of adult depression. This issue warrants much further attention as it relates to Axis IV because DSM-IV currently limits reporting stressors that occurred prior to the past year to situations in which the stressors ‘clearly contribute’ to the current disorder (DSM-IV, p. 31).

There is minimal evidence that clinicians can reliably establish whether or not environmental stressors ‘clearly contribute’ to an individual's psychiatric disorder. For example, Skodol & Shrout (Reference Skodol and Shrout1989a) highlighted the existence of substantial variation across clinicians in ratings of ‘etiologically significant stressors’. Schrader et al. (Reference Schrader, Gordon and Harcourt1986) also reported on the difficulty that clinicians experience in judging the etiological significance of a stressor, pointing out the problem of determining the meaning of the stressor to the patient, and also the meaning of the stressor to the clinician.

When the analyses were extended to other mood, anxiety and substance use disorders, there was a similar pattern of results. The latent classes that were most strongly predictive of recurrent depression, those characterized by financial and interpersonal instability as economic difficulty, were also predictive of these other disorders (except social phobia).

We conclude that psychosocial and environmental stressors have prognostic value for depression, in addition to other mood, anxiety and substance disorders, and therefore should be retained in the diagnostic evaluation on an axis separate from the diagnostic criteria. Unfortunately, advancing the theoretical and empirical basis for Axis IV has not played a major role in the activities surrounding the development of DSM-5 (Kupfer et al. Reference Kupfer, First and Regier2002; Regier, Reference Regier2011). Setting aside the broader question regarding the usefulness of a multi-axial system of classification (Williams, Reference Williams1985a, Reference Williamsb; Gruenberg & Goldstein, Reference Gruenberg, Goldstein, Phillips, First and Pincus2003), we articulate the following research agenda for strengthening Axis IV. First, research is needed to enhance our understanding of the psychosocial and environmental problems that are most important for the prognosis of psychiatric disorders. This work should incorporate detailed assessments of stressors that cover the entire lifespan, that include information on the psychological impact of stressors, and that overcome the limitations of stressful event checklists (Dohrenwend, Reference Dohrenwend2006). Second, research is needed to develop standardized measures of psychosocial and environmental problems that could be administered in clinical settings. These will, by necessity, be shorter and less extensive than research assessments but should cover all of the relevant domains of stressors found to predict the prognosis of disorders, and be subjected to reliability testing. Third, research is needed to determine whether information on psychosocial and environmental problems can be used to enhance psychiatric treatment and thereby improve prognosis. For example, this could include incorporating into treatment plans steps to overcome barriers to treatment effectiveness that exist in the context of social and environmental stressors (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Houck, Szanto, Dew, Gilman and Reynolds2006). The third step in this research agenda is most important for establishing the clinical utility of Axis IV.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the contributions of K. McGaffigan for data management and statistical programming, and R. Hawrusik for research assistance. This research was supported in part by grants MH085050 and MH087544 from the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interest

Dr M. Fava has received research support from Abbott Laboratories; Alkermes, Inc.; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; BioResearch; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cephalon, Inc.; CeNeRx BioPharma; Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC; Clintara, LLC; Covidien; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ganeden Biotech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Icon Clinical Research; i3 Innovus/Ingenix; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development; Lichtwer Pharma GmbH; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC; Photothera; Roche; RCT Logic, LLC; Sanofi-Aventis US LLC; Shire; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Synthelabo; and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has served as advisor or consultant to Abbott Laboratories; Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG; Alkermes, Inc.; Amarin Pharma Inc.; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Auspex Pharmaceuticals; Bayer AG; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Biovail Corporation; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon, Inc.; Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC; CNS Response, Inc.; Compellis Pharmaceuticals; Cypress Pharmaceutical, Inc.; DiagnoSearch Life Sciences (P) Ltd.; Dinippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Inc.; Dov Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; ePharmaSolutions; EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GenOmind, LLC; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal GmbH; i3 Innovus/Ingenis; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; Knoll Pharmaceuticals Corp.; Labopharm Inc.; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; MedAvante, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; MSI Methylation Sciences, Inc.; Naurex, Inc.; Neuronetics, Inc.; NextWave Pharmaceuticals; Novartis AG; Nutrition 21; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; Pharmavite® LLC.; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Precision Human Biolaboratory; Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Puretech Ventures; PsychoGenics; Psylin Neurosciences, Inc.; Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ridge Diagnostics, Inc.; Roche; RCT Logic, LLC; Sanofi-Aventis US LLC.; Sepracor Inc.; Servier Laboratories; Schering-Plough Corporation; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Synthelabo; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; Tal Medical, Inc.; Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Vanda Pharmaceuticals, Inc. He has received speaking or publishing fees from Adamed, Co; Advanced Meeting Partners; American Psychiatric Association; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; AstraZeneca; Belvoir Media Group; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cephalon, Inc.; CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Imedex, LLC; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; United BioSource, Corp.; and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He owns stock in Compellis. He has a received royalty, patent or other income from a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD) and a patent application for a combination of azapirones and bupropion in major depressive disorder (MDD), copyright royalties for the MGH Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), Sexual Functioning Inventory (SFI), Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS), and SAFER. He has a patent for research and licensing of SPCD with RCT Logic; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; and World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.