1. Introduction

This article considers urban sound art installations as acts of ‘sonic placemaking’, where placemaking is understood as localised interventions that create a sense of place by interconnecting communities and urban spaces (Fleming Reference Fleming2007). The article presents three approaches for creating urban sound art installations and ten attributes of permanently situated sound installations. The research draws on an international field trip conducted by the author in October 2015, which, through an inductive process, documented several ‘enduring’ sound installations, located in the North-Eastern United States, the UK and Europe (Table 1). Endurance is associated with success, insofar as each investigated sound installation has permanently transformed a geographically specific locus of a soundscape. The proposed approaches and attributes are constructed from the analysis of existing sound installations, which are embraced by local, and international, visitors. As such the research extracts the qualities of existing successes rather than theorising abstract qualities of possible future installations. In addition to the site visits, a number of artists, architects and curators (referred to as ‘creators’ in this article), who are responsible for the works, were interviewed. It was discovered that each of these creators exhibited deep relationships with their chosen sites of intervention. It is proposed that by developing a relationship with a site, the creators are able to augment a pre-existing ‘spirit of place’,Footnote 1 which informs the ‘life’ of the installation.

Table 1 Sound installations visited

There is no claim here that the installations visited are representative of international diversity; it is recognised that the field trip might be considered Eurocentric considering there are no examples from Asia, Africa or South America. Sites were selected from the author’s own investigations of influential sound installations discovered in previous research (Lacey Reference Lacey2014), and from a request sent to a responsive World Forum for Acoustic Ecology (WFAE) listserv email (2015). This article concentrates only on those sound installations that were visited during the fieldwork, from which the approaches and attributes have been formulated. While the conclusions that have been drawn from the applied fieldwork methodology (see below) adequately encapsulate the findings of this study, it is not considered to be exhaustive. For instance, the claims made here would benefit greatly from a study of user experience. Furthermore, future studies may well identify additional attributes (and possibly approaches) and/or even expand on the attributes described here. The primary aim of this study is to emphasise the value of sonic placemaking to urban design, by way of identifying, and describing, the approaches and attributes of internationally recognised enduring sound installations. For broader studies of international sound art installations (which reference some of the discussed works) see Ouzounian (Reference Ouzounian2008) who provides an extensive and useful list of sound installations realised in a wide range of contexts, and LaBelle (Reference LaBelle2006) whose vast inventory of sound art works include public sound art installations; a comprehensive list of urban sound installations can be found in Lacey (Reference Lacey2016).

2. Field Work Methodology

An inductive process, developed prior to the field trip, informed my interactions with each of the sound installations. This approach was taken so that common approaches and attributes could be more easily identified in the post-field trip analysis. For each site the following fieldwork was completed:

-

1. Where possible, interviews with the sound installation creators as listed in Table 1.

-

2. Four-channel recordings of each site with two Zoom H6 microphones and RØDE dead kitten windjammers.

-

3. Two-channel transition recordings with one Zoom H6 microphone, RØDE shock mount and RØDE dead kitten windjammer.

-

4. Extended listening (up to one hour) in each location as a means to connect with each site. During this time notes were entered into a journal that included factual information and emotive responses.

-

5. Photography and video works for visual documentation of each site.

-

6. Observation of visitors who engaged with the installations.

Post-field trip analysis included extended studio listening, recreating recorded sound environments on a multichannel spatial sound system, cross-referencing interview transcriptions, and cross-checking field notes with interviewee comments and site photographs.

3. Description of Works

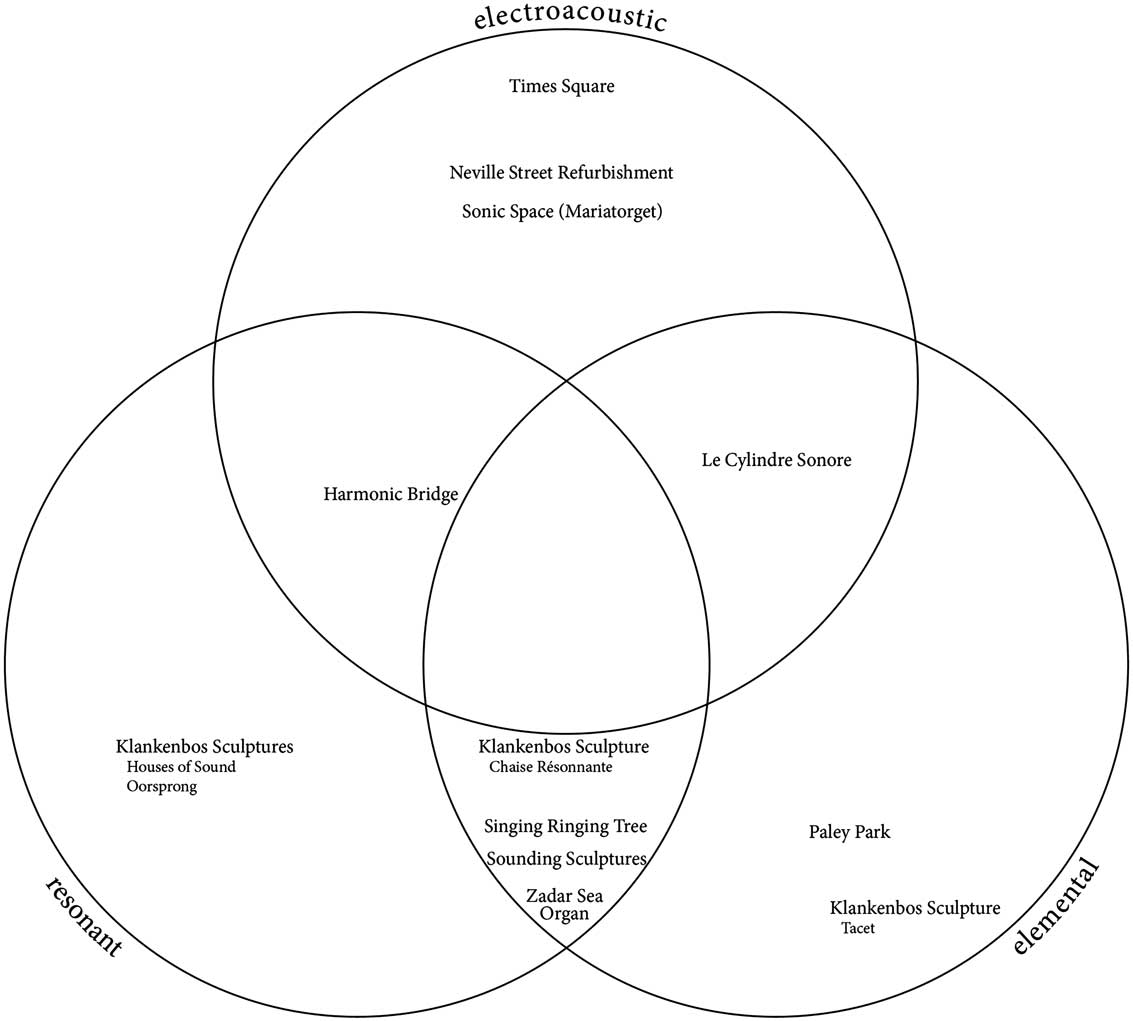

Installations were visited in the same order as listed in Table 1. Each site description contains an accompanying field recording, except for the Klankenbos Sound Forest, which contains a weblink to a blog with accompanying sound files. The reader is encouraged to listen to each of the accompanying sound files to hear the types of sounds the installations generate, which informs the three approaches to creating urban sound installations: electroacoustic, resonant and elemental (Figure 1). All visited works (except the Garden of Sonic DelightsFootnote 2 ) have been included in Table 1 as it was by analysing all of the works in their totality that the three approaches were discovered. However, it is the individual works (in contrast with the curated Klankenbos Sound Forest and Garden of Sonic Delights), especially those with an accompanying interview, that were subjected to the most thorough analysis and became crucial for revealing the attributes.

Figure 1 Three approaches for creating enduring sound installations.

There is a significant difference between the individual sound installations and the multiple curated works of the Klankenbos Sound Forest. The sound forest is considered here as a laboratory, which contributes useful information for possible urban applications. Four specific works from the Klankenbos Sound Forest (see Figure 1) are considered alongside the individual works. Additionally, an interview with the director sheds interesting light on issues pertaining to urban sound installations which have contributed to the development of the attributes. Similarly, Paley Park, being an urban design project, may seem inconsistent with other individual works; nevertheless, it is interesting to consider it as an urban sound installation given its impressive impact on the immediate sonic environment. It should also be noted that Björn Hellström’s Sonic Space (Mariatorget) was visited on an earlier field trip (2012). Finally, although Max Neuhaus’s Times Square was advertised as closed on the Dia Art Foundation website, and despite the inaccessibility of the fenced subway grates, the installation sounds could still be heard (see image and audio in Table 1).

4. Three approaches for transforming sound environments

In exploring and analysing the discussed sound installations three distinct approaches to sound making were revealed – electroacoustic, resonant and elemental. A Venn diagram has been produced which represents the relationship of each sound installation with the approach(es) utilised for its creation (Figure 1). Some of the sound installations exclusively utilise a single approach while others are located across two of the approaches. Each installation has been placed nearest the approach that is most related to its realisation. The uninhabited segment of the Venn diagram where electroacoustic, resonant and elemental overlap might be suggestive of unexplored approaches to designing sound installations.

4.1. Electroacoustic

This includes sound installations that generate new sonic environments through the addition of loudspeakers and playback technology. Introduced sounds are composed/designed by the artist in relationship to the existing sounds of the site. In the Venn diagram’s electroacoustic circle three works are included:

-

∙ Times Square is the most exclusively electroacoustic in that it comprises a single speaker playing a consistent industrial-type drone.

-

∙ The Neville Street Refurbishment is also exclusively electroacoustic although it also includes acoustically treated tunnel walls that provide increased acoustic clarity (see resonant approach for further discussion).

-

∙ Sonic Space (Mariatorget) uses speakers to apply an informational masking technique (Hellström Reference Hellström2012) that distracts listener attention from surrounding motor traffic.

4.2. Resonant

This approach identifies two types of resonance which were discovered in the works included in this study. First, the use of the resonant properties of open-ended tubes or pipes; and second, structural vibrations. It does not include ‘spatial resonance’ (Augoyard and Torgue Reference Augoyard and Torgue2005: 110). As every work in this study has some type of enclosure,Footnote 3 the inclusion of this resonant type would require every work to be located in the resonant sector of the Venn diagram. This is not to downplay the importance of spatial resonance to many of the sound installation works;Footnote 4 rather, spatial resonance is thought of as a ubiquitous phenomenon that exists in urban spaces with or without the addition of installation works.

The first resonant approach is most clearly realised with the use of open-ended pipes in the Sea Organ and the Singing Ringing Tree (both of which also utilise the elemental approach), and Harmonic Bridge (which also utilises the electroacoustic approach). These works will be explained in more detail in the attributes, below. The Klankenbos Sound Forest houses multiple sound installations that take advantage of the resonant properties of tubes: Tony DiNapoli uses open-ended tubes to amplify two lithophones in his work Chaise Résonante; and Hans van Koolwijk’s Oorsprong is a giant resonating metal flute with an interactive, immersive sound field.

Two examples of the second type of resonant approach include:

-

∙ Harry Bertoia’s sounding sculptures that generate resonant sound fields created by the vibrations of colliding metal rods;

-

∙ Pierre Berthet’s Houses of Sound (Klankenbos), comprising two vibrating steel structures excited by wires that transmit sound.

4.3. Elemental

The elemental approach can be considered as two types – those installations driven by the elements (wind and water) and those that use the elements to generate sounds. These works require no amplification or electrification:

-

∙ Harry Bertoia’s sounding sculpture is the most obvious example of a work that is driven by the element of wind (it also utilises the resonant approach).

-

∙ Paley Park directly applies the element of water to mask city noises with an expansive water wall built in a ‘small urban space’ (Whyte Reference Whyte1980). Adding to the elemental approach, trees sway in the wind and birdsong is present.

-

∙ A sculpture at Klankenbos called Tacet by Hekkenbergarchitects and Paul Beuk brings to our attention the importance of environmental sound in shaping our everyday outdoor experiences. A glass cube is accessed via a staircase that travels underground and re-emerges within the cube. It subtracts those elements – particularly wind and, broadly speaking, environmental sound propagated through the medium of air – which connect listeners with their immediate surroundings. Fully soundproof, one is left to observe a seemingly lifeless forest, which foregrounds the importance of environmental sound in shaping our perceptions.

5. The relational model

In addition to the three transformational approaches just described, ten attributes have been discerned within the installations. Whereas the three approaches to transforming sound environments are directly related to the artistic process of working with materials to make sound, the ten attributes are considered to be emergent properties that become active after the creation of the installations. The ten attributes of enduring sound installations emerge within a necessary relationality that considers:

-

1. The artistry of the creator(s) (which includes the approaches discussed above).

-

2. The site-specific environmental conditions.

-

3. The social practices and relations of space.

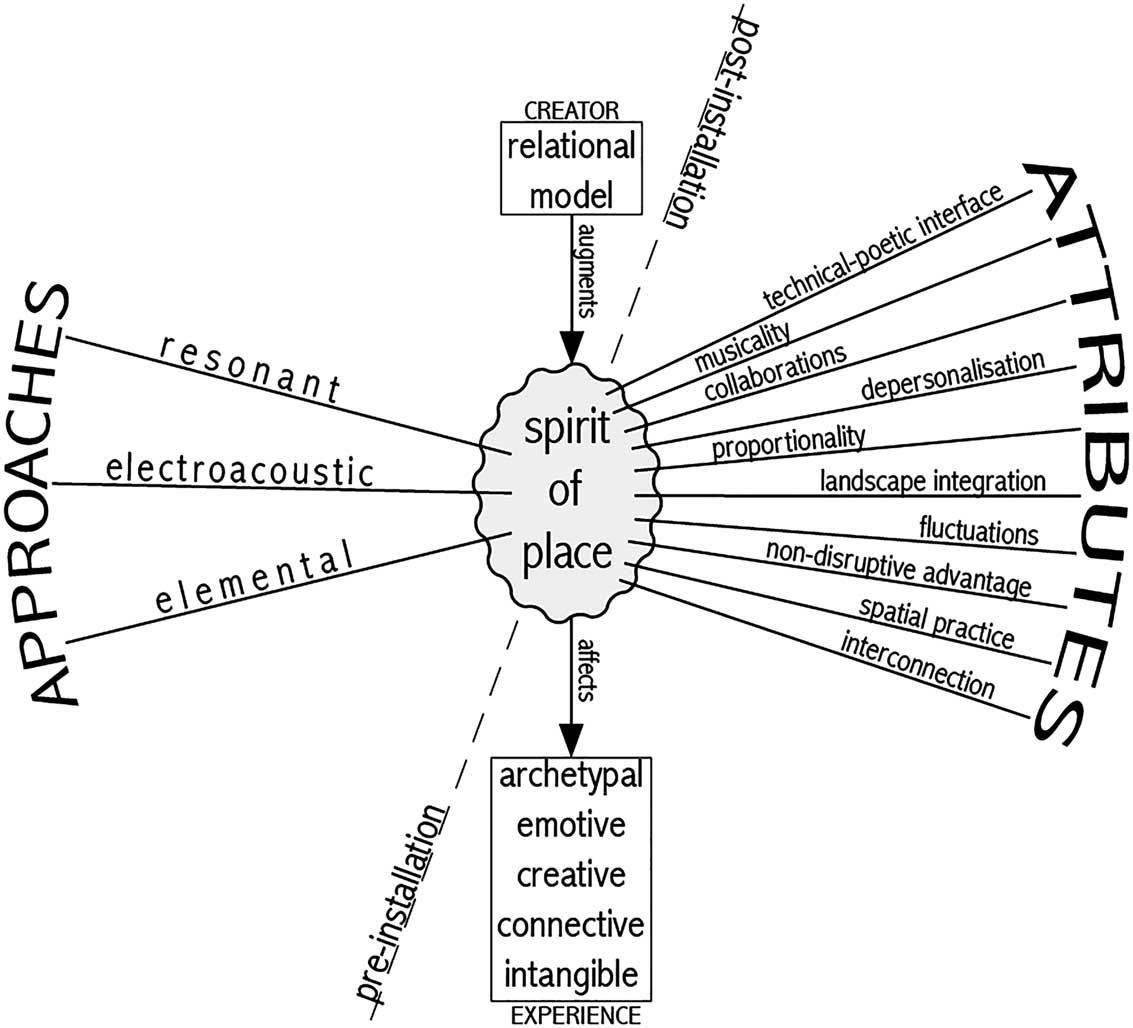

These have been placed at the three vertices of the triangle in Figure 2. The relationality is non-hierarchical and co-dependent. Accordingly, the triangle could be imagined to have a rotating axis with any relation able to take the upper position.

Figure 2 Ten attributes of enduring sound installations.

The relational model represents the necessity of a site-specific sound installation to be a product of those relations that exist between the intentions of the artist, the existing environmental conditions and the social parameters of the site. In Figure 2, the ten attributes have been plotted within this tri-polar field according to which of the three factors they most strongly exhibit. For instance, the technical-poetic interface, which is mentioned by a number of the discussed creators, is a product of the artistic act; fluctuations, which refers to the constantly shifting sound fields of nature, is closely related to environmental conditions; and finally, interconnection has been placed nearest the social pole. So while all attributes emerge within the field formed by the tripolar relationship, it should be remembered that some attributes are more specific to some relations than they are to others. The attribute descriptions below have been ordered into three clusters, dependent on which pole they are most closely aligned with.

Before describing the attributes, it should be noted that there is some ambiguity in relation to the categorisation of three of the attributes: musicality, collaborations and proportionality. Compared to the other attributes, they have a stronger correlation with artistic processes, which might warrant them being categorised as approaches. This ambiguity, it will be noted, has been accounted for in Figure 3. However, the approaches have been strictly delimited to physical sound-making artefacts. Therefore, artistic processes that were in operation prior to the creation of the works have been excluded from the approaches. Instead these artistic processes are considered to manifest. These three attributes emerge from the visited sound installations as audible and visual effects and emotional and bodily affects. It is these emergent qualities that determine their categorisation as attributes.

Figure 3 A sonic placemaking tool for the creation of urban sound art installations.

6. Ten comparative attributes of enduring sound installations

6.1. Technical-poetic interface (artistic)

Interviewed creators testify to seeking a balance between the technical and the poetic when realising their works. Poetic relationships form between creator and site, and technical aptitude is applied to express this relationship. Excessive concentration on the technical risks the creation of a spectacle that lacks a necessary connection with place. The enduring sound installations explored in this study each skilfully employ technology as a means to create experiences that exceed the technical. This attribute suggests that successfully augmenting a spirit of place depends on the creator first developing a poetic relationship with space which may be further explored through technical processes.

The creators of the Singing Ringing Tree, Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu, describe their practice as the ‘making of something technical that’s an exploration in itself that goes somewhere different … if they intermesh in the middle, then it becomes a “technical artwork”. You play with forms ’till you find the right form but technically you need to break new ground [so] technical exploration is as important as the storytelling.’ Tonkin and Liu’s term ‘technical artwork’ is suggestive of an interface that, if ignored, may lead to a reification of technological possibilities at the expense of a spirit of place – technology is employed to tell a story. When successfully working at this interface, technology becomes poetic expression.

Matt Murphy of BaumanLyons Architects reiterates this point when describing the Neville Street Refurbishment as an ‘artwork in itself that is designed to mingle in with the background sounds [so that] people don’t realise there is anything going on straight away. [This] gives it more resilience. If it was a showpiece people would be bored of it.’ Although this sound (and light) installation demonstrates an impressive technical aptitude, the real skill comes in hiding the technicalities of the work so that the listener is left with the ‘magic’ of the immediate sonic experience.

The Sea Organ is another excellent example of this attribute. It is a giant musical instrument built with engineering precision (Kapusta Reference Kapusta2007), and yet, from a visitor’s perspective, one is immersed in seemingly disembodied sounds that effortlessly synchronise with the swirling colours of the Adriatic Sea. Without doubt its location is a contributing factor, but it is the work’s seamless enmeshing with location that affords those languorous (relaxed) responses that were observable in the public who visited the site. In general, it is speculated here that while technology is essential to many of the works, it is the poetic intentions (and intuitions) of the creators which are essential for augmenting a site’s spirit of place.

6.2. Musicality (artistic)

Insofar as the installations (re)organise site-specific sounds, each of the works expresses musicality. However, the term ‘musicality’, as it is employed here, does not refer exclusively to the act of sound-making. It refers to the ‘dialogical’ listening relationship (Carter Reference Carter2004) that forms between creator and space. This relationship is understood as a plurality that includes listening, spatial awareness and site-sensitivity. Accordingly, the musicality attribute has a close relationship to poetics as discussed in the technical-poetic attribute; both attributes express the results of intuitive artistic processes that are predicated on meaningful relationships between creator and site. However, where the musicality attribute is expressed, the creator is thought to have formed a site-specific listening relationship, such that the emergent sounds feel like a natural expression of the site (see also the landscape integration attribute below).

Odland and Auinger foreground the connection between their musical practices and everyday life: ‘we both come from composition [and] are very precise about tuning and how we make the piece speak. We think about what the audience is listening for and how much they are being tuned by everyday life.’ They reiterate: ‘we are very precise about the placement of the speaker, the tuning, and how you actually make the piece speak’. Space becomes instrument – something tuned to capture the attention of the listening public.

Although the creators of the Singing Ringing Tree are architects, from the beginning they considered the structure’s sound-generating potential. Mike Tonkin explains, ‘the lower rings act as the structure, and the upper rings is where the sound is mainly generated, that’s where the flutes are cut, and we only cut the flutes in the ones that are pointing towards the wind’. Tubes are cut at varying lengths to create dissonant sound fields that vary with localised environmental conditions (which finds commonalities with the fluctuations attribute, see below).

It is clear that the musicality attribute, across many of the visited installations, is closely connected with the transformationFootnote 5 of sound. Anna Liu explains that ‘we weren’t after the music, we were after what we can do with the wind, and its transformation’. This view resonates with Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger’s comment that their process is ‘alchemical; by turning noise into music or turning the dross into some phenomenon that has beauty in it we find fragments of beauty within the urban soundscape’. In a similar way Hans Peter Kuhn’s compositions weave in and out of the sounds of passing traffic, which, as evidenced in the audio file, turns the sounds of traffic into new and surprising sonic expressions.

Bernhard Leitner’s Le Cylindre Sonore comprises a number of interweaving compositions whose spectral and temporal arrangements have musical impact. The cylinder becomes an instrument that enters into a dialogical relationship with the bamboo forests that surround it. Finally, Paul Craenen, the director of the Klankenbos Sound Forest, articulates the musicality attribute’s relation to site-sensitivity. He states that as part of the commissioning process ‘every sound installation has a research period in which the sound artist has to find a dialogue with the environment without having an aggressive impact on it, but at the same time loading it with new meanings’.

6.3. Collaborations (artistic)

An interesting discovery was the number of works that are collaborations between architects, sound artists and others. Both professions/practices bring spatial awareness and site analysis training to bear on their work. Given that architecture is predominantly a visual profession, there are clear benefits in such collaborations. Although the act of collaboration occurs before the creation of a work (aligning it, perhaps, with the approaches) the enduring effects and affects that emerge from the collaborators’ efforts are experienced post-installation, thus it is considered to be an attribute.

An obvious example is the collaboration between sound artist Hans Peter Kuhn (who was also responsible for some of the light installations) and BaumynLyons Architects in the creation of the Neville Street Refurbishment. Matt Murphy explains that, ‘we acted very well as a team, fighting for the absolute most we could get out of the space. It wasn’t just sound and light artists; it was also acousticians, structural engineers and lighting engineers from Arup, and a number of specialist consultants that we were working with that delivered the LED and sound technology.’

Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu have a different take on collaboration, stating that they think less about the collaborative act than the morphing of different creative disciplines into the creation of a work. They say ‘I think if you’re an architect or an artist or a landscape architect, you want to go and find the nature of the place, and that’s more important than actually being called an architect or being called an artist or being called a designer, it doesn’t really matter … I think it’s the process you use to find that spirit of place.’ This final point has a strong correlation with the interconnection attribute (see below).

Even in the case of Harmonic Bridge, which is most clearly a sound art project, the artists describe perceiving the underside of the bridge as similar in proportions to a Gothic cathedral, an architectural observation that informed their subsequent sonic explorations. Further to this, a consciousness of architectural understandings is pervasive in their approach to sound art and urban design: Sam Auinger states ‘we really want to have an integration of the senses so that designers and architects are not thinking with their head, but rather with their whole body, because you also hear with your whole body’.

The link between architectural object and acoustic space is clear in much of Bernhard Leitner’s works (who is both architect and sound artist); the Cylindre Sonore structure expresses his expertise across both disciplines. The Sea Organ is a collaboration between the architect Nikola Bašić and acoustic engineers from the Zagreb Civil Engineering University (Stamac Reference Stamac2005) for the creation of a harmonically tuned instrument that is played by the sea. In general, the collaboration attribute means a range of expertise leads to more sophisticated works that can respond to a range of site-specific needs and sensory phenomena.

6.4. Depersonalisation (artistic)

In the context of this article, depersonalisation refers to the absence of the identity of a ‘creator’ when encountering a publicly situated sound installation. When entering a gallery or concert hall, we know that we are about to encounter an artist or composer whose work we will experience. One of the distinct differences with publicly situated sound installations is that the creator of the work is seemingly absent. This attribute does not relate to the possible personalisation of works by the listening public, which properly belongs to the interconnection attribute (see below). It refers exclusively to the anonymity of the artist, which is a feature of all those sound art installations visited during the field trip.

It was difficult to locate plaques or information boards that described the works, if they existed at all; this seems a necessary extension of the subtlety of many of the installations. Matt Murphy explains that, ‘the fact it [Neville Street Refurbishment] is so subtle is testament to how Hans Peter wanted to work. It was about the work subconsciously dawning on people after they’d been down here a few times. They might not even realise the work the first few times they walked through.’ The depersonalisation attribute contributes to a sense that the introduced sounds are a natural expression of the space.

Of course one can easily search for information about the creators of the works, but this is not necessary in forming a connection with site. In fact the depersonalisation attribute expresses an admirable trait of the installation artist: humility. The work seems to exist without needing the reputation of the creator to support it. It weaves its own relationship with the site, and with those who come to form a connection with it. For instance, this is illustrated by an observation made by Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu regarding the post-installation life of the Singing Ringing Tree: ‘we quite like the people, the locals, tagging it; they’ve taken ownership of it’. Following from this I speculate that through the relationship the public forms with the installations, the works take on a life of their own. Rather than the listening public being enamoured by an individual’s name or reputation, they interconnect with a work via their own sensory and imaginative experiences.

6.5. Proportionality (environment)

The proportionality attribute refers to specific mathematical relationships that have been applied to the creation of works, which produce aesthetically pleasing outcomes including beauty and harmony. These mathematical relationships can be identified in the tonal and/or structural characteristics of many of the sound installations. The term ‘proportionality’, as applied in this study, appropriately captures the proportional mathematical relationships discussed by the interviewees, especially symmetry, ratios and the tonal system.

Tonal expressions of this attribute are unsurprising given the relationships between mathematics and music, particularly apparent in the Sea Organ (Kapusta Reference Kapusta2007). Structural expressions of this attribute are integral to the visual characteristics of some installations, especially the Singing Ringing Tree (see below). It should be noted that this attribute expresses a particular type of ‘classical’ (Euclidean) mathematics that does not necessarily reflect other types of mathematical knowledge, such as fractal geometry and Chaos (Mandelbrot Reference Mandelbrot1977; Gleick Reference Gleick1987). Despite this, certain mathematical relationships, all of which are concerned with tonal and/or structural proportions, have an inescapable presence in both the installation works and the reflections of the interviewees.

Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger, and Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu speak of proportional mathematical relationships in relation to creating beauty. Without doubt, specific ordering principles of mathematics helped them to achieve their aesthetic outcomes. There are numerous examples of this:

-

∙ Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger explain that while exploring the different harmonic proportions for optimum microphone placement in the tuning tubes, they had rediscovered certain ideas of Pythagoras.

-

∙ Various structural aspects, particularly its height and some horizontal cross sections, of the Singing Ringing Tree were designed according to the golden ratio 1:1.6.

-

∙ The Sea Organ uses the harmonic musical system to create its sea-driven soundscapes. It comprises eight sections, each comprising five harmonically tuned pipes.

-

∙ The symmetry of Le Cylindre Sonore is mathematically precise, with eight equidistant perforated concrete panels, each housing lines of three speakers.

-

∙ Tony DiNapoli, who created the work Chaise Résonante for the Klankenbos Sound Forest, precisely tunes his lithophones at microintervals to create beating patterns, which modulate the immediate soundscape.

Perhaps a more accurate term to describe this attribute is ‘aesthetic’, given that mathematical relationships have been utilised for the creation of beauty and/or harmony. This point is elaborated by Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu, who, after explaining the use of the golden ratio in the creation of the Singing Ringing Tree, state: ‘I think you’ve got to, whether you’re an artist or an architect, make something strike you as beautiful so it does engage you physically and visually.’ However, the term ‘proportionality’ has been maintained as it reflects the fact that the desired beauty has emerged from the application of proportional mathematical relationships.

6.6. Landscape integration (environment)

Enduring sound installations have the quality of belonging to the site in which they are realised. This contributes to the sense of place they create. Note in the relational model that this attribute is near to the depersonalisation attribute. There is a sense that an enduring installation belongs to the site in which it is embedded rather than to the maker who creates it. The work seems to be emergent, and ‘makes place’ by weaving a relationship between site and visitor. Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu explain that the Singing Ringing Tree emerged from the physicality of the land: ‘In all our practices we are trying to find the nature of place; in this case the nature of place was the incredibly windy conditions, and you’re surrounded by these tall, reedy grasses. We took that form, turned it on its side and amplified it [visually and sonically], so it feels like it’s a part of the place.’

Some works provide no visual cues as to their existence. Neuhaus’s Times Square provides only sonic information that blends with its surroundings. It was clear to me that most people did not notice the installation sounds, and if they did there was a belief that it was simply another industrial drone of the city. And yet, upon close listening, the work creates a new impression of the turbulence of Times Square: an unlikely point of stillness, and, given the work’s placement beneath a subway grate, an imaginative reworking of the subterranean city. The Neville Street Refurbishment uses acoustic panels to enhance the listening environment without providing any visual cues as to their existence. Matt Murphy explains that: ‘With the design of the panels themselves, there is a number of things they are doing that you cannot see or hear, namely absorbing the sound and in so doing creating a much nicer atmosphere to what was previously there.’

The Sea Organ and Harmonic Bridge contain some visual cues, given the steps of the Sea Organ and the concrete speaker boxes of Harmonic Bridge; yet these works are skilfully integrated into the site such that they appear as embodied expressions of the accompanying architecture. The sculptures of Klankenbos and the architectural object of Le Cylindre Sonore are more obviously object-like, yet their purposeful placement amongst forest-like backgrounds gives them a sense of belonging to a broader environmental assemblage. The landscape integration attribute suggests that considering sound is not enough; the physical artefacts attached to a sound installation should also carefully consider the visual landscape.

6.7. Fluctuations (environment)

This attribute is expressed where sonic placemaking recreates the diversity of natural soundscapes. The attribute first emerged in discussions with Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger. They describe some urban sounds (air-conditioners, transmitters) as ‘low-information, steady-state and time-erasing trances that separate you from the fluctuating world of nature and the environment around you’. We might conclude from this statement that a sound installation ought to reflect nature’s capacity to provide constant fluctuations, which provide invigorating and stimulating sound fields. Sound installations that express this attribute provide a stimulus missing from the repetitive soundscapes of urban life; as expressed by Bruce Odland, ‘Is our city full of repetitive motor sounds on a day-to-day basis that somewhat resemble each other from day-to-day? Yes, way more so than the natural environment.’

The fluctuation attribute has a strong relationship to the elemental approach, described above. This is particularly apparent in Harry Bertoia’s sounding sculptures. The resonant copper-beryllium rods are shaken by the winds much like a field of grasses. The shimmering sound field they generate is immersive, and its spatial character constantly shifting due to the natural fluctuations of the wind. Similarly, the sound fields generated by the Sea Organ and the Singing Ringing Tree are constantly changing depending on the natural fluctuations of immediate environmental conditions.

However, this attribute is also perceivable in the electroacoustic approach. For instance, Björn Hellström’s informational masking technique ensures that the attention of the listener is shifting between traffic and installation sounds due to the constant morphing of geographically defined sound fields. Similarly, Hans Peter Kuhn’s sound works transform the roaring pulse of passing traffic into new sonic phenomena. Even Max Neuhaus’s Times Square, which could be mistaken for an industrial drone, emits, upon careful listening, shimmering mid- to high harmonics that subtly fluctuate in and out of the installation’s low-frequency drone (refer to Table 1 audio). More broadly, the fluctuation attribute, as expressed through urban sound installations, challenges worldviews that distinguish between the qualities of natural and urban sounds. Instead, this attribute suggests ways that the urban can come to express the complexities of natural soundscapes through careful design.

6.8. Non-disruptive advantage (social)

An installation must consider those businesses and residents who are close by the installation. A sound installation that constantly invades the sonic space of local residents is always at risk of removal. In being located away from businesses and residents, all investigated installations have avoided this problem. This means that local populations have control over their encounters, rather than generated sounds being forced upon them. In general, when creating a sound installation in populated areas, one should be alert to the danger of creating sound installations that are either too repetitive or aggressive (Lacey Reference Lacey2014: 48).

This was a concern that even the creators of the Singing Ringing Tree had to contend with, despite the fact that their installation is the most ‘non-urban’ of all visited works. Mike Tonkin reports that the local councillors wanted to know, ‘How are we going to turn it off? And we said, “You can’t,” so someone else said “Surely it’s going to disturb all the birds”. And actually it was nice, on the opening day, there were birds all over the place, and sheep and horses, it’s almost like the animals were attracted to it.’ This anecdote is an apt illustration that most sound installations will be scrutinised for possible disturbances.

The non-disruptive advantage attribute sets up an interesting counterpoint between sound installations and ‘experience design’ approaches (Pine and Gilmore Reference Pine and Gilmore1998) that design soundscapes to encourage consumer spending, and soundscape interventions for social control such as the dispersal of teenagers from railway stations.Footnote 6 Such approaches are purposefully disruptive: space is programmed to produce certain behaviours. In contrast, sound installations are intended to create experiences that are non-programmatic and afford imaginative responses in those listeners willing to engage with the works. In the explored works, desired responses are not pre-determined; instead, a space is created in which ‘new’ experiences might emerge. Another distinction from experience design approaches is that, by locating the sound installations away from human habitation, the journey to the sound installation becomes part of the experience, and also allows for the possibility of accidental encounter. For example, the Neville Street Refurbishment and Harmonic Bridge provide a transitory encounter that can, if the public wishes, turn into a longer-term interaction (particularly the concrete speaker boxes of Harmonic Bridge that invite people to sit – see Table 1).

6.9. Spatial practice (social)

Enduring installations can transform the social practices of everyday life (De Certeau Reference De Certeau1984; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991, Reference Lefebvre2004). In the context of the spatial practice attribute, the changing spatial properties (particularly sonic) of an installation site are considered to be inseparable from commensurate changes in the everyday social practices of site visitors. The Neville Street Refurbishment makes the clearest intervention into daily life by first acoustically lining a busy underpass to reduce reverberation, and then installing an electroacoustic system that interacts with the transformed traffic sounds. Traffic becomes an evolving symphony rather than merely an irritation to be escaped. This invites the curious listener to experience these everyday phenomena in new ways (refer to audio sample in Table 1). In so doing, new spatial practices, such as changing pedestrian behaviours (conversations, active listening) have since emerged. Matt Murphy explains: ‘[acoustic] dampening has made a big difference in the underpass […] We wouldn’t have been able to do this interview down here; you couldn’t hear yourself think. The underpass connects the two halves of the city (but) you couldn’t talk to the person you were with, it was a very oppressive environment, people scurried through here as quickly as they could.’

Odland and Auinger state that their desire with Harmonic Bridge was to ‘turn noise into music or turn dross into a phenomenon that has beauty in it [see proportionality attribute for further discussion], allowing people to find fragments of beauty in the urban soundscape’. To achieve this, the underpass of the motorway was imagined as a Baroque cathedral: ‘I remember being really struck by the fact that the proportions underneath this elevated roadway were similar to a Gothic cathedral … I thought, “there are invisible walls underneath here it’s just like a cathedral!” If we were able to let the harmonics sing underneath, then they would activate a profound Gothic airspace.’ Incidentally, this was related to Odland and Auinger’s decision to ‘tune’ the space to the key of C. Odland explains, ‘a sixteen foot C is sort of like the gold standard of Baroque organ design’ (note the relationship with proportionality attribute).

Examples of transformed spaces that invite new spatial practices are prevalent among all the works:

-

∙ The Singing Ringing Tree’s haunting soundscapes and striking structure, overlooking the town of Burnley.

-

∙ The Sea Organ’s stretch of marble steps and immersive musical experience.

-

∙ Bertoia’s shimmering sounding sculptures set amongst the urban hubbub of Chicago.

-

∙ Le Cylindre Sonore’s bamboo-electroacoustic soundscapes submerged beneath well-utilised parkland.

-

∙ The thundering waterwall of Paley Park masking the traffic sounds of New York.

Each installation provides spatial experiences – visual and acoustic – that clearly differ from surrounding site conditions; however, each work is skilfully integrated into its location (see also landscape integration and non-disruptive advantage attributes) to ensure that the intervention is respectful to existing site conditions. This is a difficult balance to achieve: the simultaneous transformation of space and spatial practices without creating annoyance or disruption.

6.10. Interconnection (social)

The interconnection attribute is the optimum achievement of sonic placemaking (and placemaking in general). It occurs when the senses and imagination merge with place, causing full integration between listener(s) and city. Where interconnection occurs, a sense of belonging has been achieved. Despite this attribute’s importance, it is difficult to demonstrate its existence without a thorough analysis of visitor perceptions (unfortunately beyond the resources of the discussed research); however, through the interviews and my own observations, there is some evidence to suggest that interconnections have formed within the discussed installations. The three clearest examples are Harmonic Bridge, the Singing Ringing Tree and the Zadar Sea Organ.

Odland and Auinger report that ‘the director of MassMOCA [Joe Thompson] told us a local woman had been sitting there [within the installation] and wrote a long poem about the sounds [and] we have evidence of dogs sleeping next to the speaker and babies sleeping on the speaker […] it’s like “this is traffic sounds guys – what’s going on!”’ Odland and Auinger’s story provides us with a profound example of how noises can induce positive responses that affect us enough to change our daily activities, and, in this case, literally through the writing of poetry. This is consistent with their desire to encourage the public to ‘start to listen to the world around them and connect to the environment and gain information, joy, even bliss from the pleasures of listening’.

Tonkin and Liu explain that they like to explore designs that are ‘primal, so that they resonate with people on a psychological level; for instance, a tree, everyone can relate to a tree, and a lot of the archetypes we use will be a tree or a hill or a mountain or a wave, so they’re things that everybody has a relationship to’. While at the Singing Ringing Tree I witnessed four groups of people make the journey to the tree. I learned through conversation that many were repeat visitors, which is a demonstration of the work’s attractive power. If indeed archetypal forms resonate with the public (which the Singing Ringing Tree seems to have done, given its four million views on YouTube and the architectural firm’s commissioning [as reported to me during the interview] to build similar structures in Saudi Arabia and Texas), then the Singing Ringing Tree points to the importance of carefully considering visual designs in the creation of sound installations (a point discussed in more detail in the collaboration attribute). Tim Edensor, who has written extensively on atmospheric qualities (Edensor Reference Edensor2012; Edensor and Sumartojo Reference Edensor and Sumartojo2015), and who kindly accompanied me on the day, reflected this sentiment in an in-situ conversation. He stated that ‘the very form of the Singing Ringing Tree suggests the ways we might respond to the landscape if we were more sonically attuned to it’.

The most striking example of the interconnection attribute, at least from my own observations, was the Sea Organ. It is a work that has been embraced by the local population and, like the Singing Ringing Tree, has captured the global imagination. A constant stream of people visit the site, swim by its shores, and it is clearly observable that many people are simply sitting and listening. It warrants further study to understand exactly how the sounds of the Sea Organ are affecting the listening public, which is a question that might be asked of all the installations. But I would like to speculate that the Sea Organ, similarly to all the sound installations discussed here, points the way to improving interconnectivity, social cohesion and well-being in our cities. There are some conclusive comments, regarding my own experiences of the visited installations, which support this:

-

1. The visited sites are accessible to all people.

-

2. It is clear, from my own observations, that all of the works attract both passers-by and lingering visitors.

-

3. Each site affords unique listening experiences, within geographically specific locations, that diversify urban life.

The interconnection attribute, which is the optimum outcome of placemaking, might be embraced as a leading principle for the design of small city spaces (like those visited during the field trip) that operate as gathering points for collective immersion in transformative (spatial and emotional) sonic experiences.

7. Conclusion

The approaches and attributes for understanding the value of enduring sound installations proposed in this article have been discovered in a real-world bottom-up research process, rather than presented as a design methodology based on theoretical abstractions. These concepts have been combined in Figure 3, a sonic placemaking tool for situating sound installations in urban spaces.

A diagonal line bisects Figure 3, which marks the point at which the creator(s) complete their work and the sound installation becomes autonomous. The spirit of place is present both pre- and post-installation, but is considered to be augmented post-installation though the act of sonic placemaking. The vertical arrangement, running from top to bottom, represents the relationship that the creator builds with a site by connecting with its sprit of place (through listening), and the subsequent affects experienced by those who encounter the site. The listed affects are built from conversations with interviewees and my own onsite observations and personal experiences. The ‘intangible’ experience opens up the possibility that a sound installation can connect the listener with profound listening and imaginative, even transformative, experiences.

The horizontal relationship between the approaches and attributes, running from left to right, represents both the field trip findings and the diagram’s potential application as a creative placemaking tool. Regarding the field trip findings, the three discovered approaches are responsible for generating the sounds of the installations, and the ten discovered attributes are expressed (in various combinations) by each of the explored sites (though not necessarily all attributes are expressed by every installation). Note also that Figure 3 locates three of the attributes – musicality, collaborations and proportionality – closer to the approaches. As discussed above, these three attributes are manifestations of pre-installation intuitive artistic processes, which aligns them more closely with the ‘making of works’ than the other attributes.

However, when viewed as a creative design tool, distinctions between approaches and attributes become less important. The approaches and attributes, now discovered, can act collectively as approaches to making and ways of thinking about sonic placemaking. For instance, a collaborative group could seek a site that provides a non-disruptive advantage, while experimenting with materials that recreate the fluctuations of nature. Or, perhaps the technical-poetic interface attribute could encourage technological experimentations that seek more profound integration between installation and landscape.

Figure 3 might be thought as an imaginative tool with which planners, designers and artists can perceive the city as containing a sprit of place, which can be augmented to enrich city life. In this sense, the sound installation does not act as spectacle, place of entertainment or, broadly speaking, as function, but becomes part of a broader agenda to create spaces within global cities that enhance human well-being. The installations discussed in this article prove that, far from being a fantasy, this is an achievable aim for those urban planners and designers who have the necessary foresight.