Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is an inherited cardiomyopathy characterised by ventricular arrhythmias and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Diagnosis is based on criteria that take into account electrical and structural cardiac abnormalities, as well as mutation analysis. Appropriate pharmacological and device therapies are important in the management of this disease; however, as exercise is an under-appreciated but important environmental factor for the development and progression of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, and is associated with more severe arrhythmic and structural disease, this review will explore these issues in some detail.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy overview

This condition is a progressive cardiomyopathy characterised by ventricular arrhythmias and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death, especially in young individuals and athletes.Reference Marcus, Fontaine and Guiraudon 1 – Reference Dalal, Nasir and Bomma 3 Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy results from disruption of the desmosome, which causes replacement of cardiac myocytes by fibro-fatty tissue. The right ventricle is more affected than the left.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner. The estimated prevalence is 1/5000.Reference Peters, Trummel and Meyners 4 Several mutations, predominantly in desmosomal proteins, have been identified and can be found in up to 60% of affected individuals.Reference Groeneweg, Bhonsale and James 5 , Reference Den Haan, Tan and Zikusoka 6 Mutations in plakophilin2 account for approximately half of these.

Patients usually present during the second to fifth decades of life. Symptoms at presentation include palpitations, lightheadedness, syncope, and sudden death.Reference Dalal, Nasir and Bomma 3 , Reference Groeneweg, Bhonsale and James 5

Bauce et alReference Bauce, Rampazzo and Basso 7 reported 53 children who were mutation carriers. None of the children under 10 years of age met the 1994 Task Force criteria, whereas 33% of those between 11 and 14 years of age and >14 years of age met criteria initially. Moreover, 40% manifested overt disease by 18 years of age, suggesting that the disease can present during adolescence and young adulthood and is progressive.

Te Riele et alReference Te Riele, Sawant and James 8 identified 75 paediatric-onset cases of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and compared clinical characteristics and outcomes with 427 adult patients seen at two centres. Over three-quarters were mutation positive and most were probands. They found that children were more likely to present with sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest, compared with adults, who presented most commonly with sustained ventricular tachycardia. Once diagnosed, the disease course and clinical characteristics of the disease were similar in both groups.

Diagnosis

Owing to the variable penetrance and expressivity, the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is complex and is made through a scoring system with major and minor criteria, based on a combination of ventricular dysfunction and structural alterations, tissue characterisation, electrocardiographic re-polarisation/depolarisation abnormalities, ventricular arrhythmias, family history, and genetic testing. The 2010 update to the Task Force criteria guidelinesReference Marcus, McKenna and Sherrill 9 replaced non-specific descriptions of morphological changes with very specific echocardiographic and MRI criteria, as it was recognised that many patients were being inappropriately diagnosed with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy previously.

In the early stages of disease, structural changes may not yet be apparent or are localised. Even during this “concealed phase”, there is a risk of sudden death; however, most patients with ventricular arrhythmias will show structural changes.

An important consideration when using the Task Force criteria for the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy in children is that the criteria are primarily based on data from adults. For instance, although a major criterion in adults, T-wave inversions in the anterior praecordial leads (Fig 1) are a non-specific finding in children ⩽14 years of age.Reference Marcus, McKenna and Sherrill 9

Figure 1 Electrocardiogram of a 14-year-old patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy showing pathologic T-wave inversions in the praecordial leads V1–V4.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and exercise

The theory that exercise is an environmental factor in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy came from the observation that athletes are disproportionately represented among patients with the disease. It was thus hypothesised that increased myocardial strain, as occurs during exercise, accelerates disruption of the desmosomes. The resulting fibro-adipose replacement increases the risk of arrhythmias and sudden death.Reference Calkins 10

In addition, one of the first studies to highlight the relationship between exercise and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy showed that young athletes had a fivefold risk of dying of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy compared with non-athletes.Reference Corrado, Basso, Rizzoli, Schiavon and Thiene 11

Saberniak et alReference Saberniak, Hasselberg and Borgquist 12 studied 110 patients, 65 with manifest arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and 45 mutation-positive family members. The authors found that athletes participating in vigorous exercise were more likely than non-athletes to meet diagnostic criteria. They also had lower biventricular function and earlier onset of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

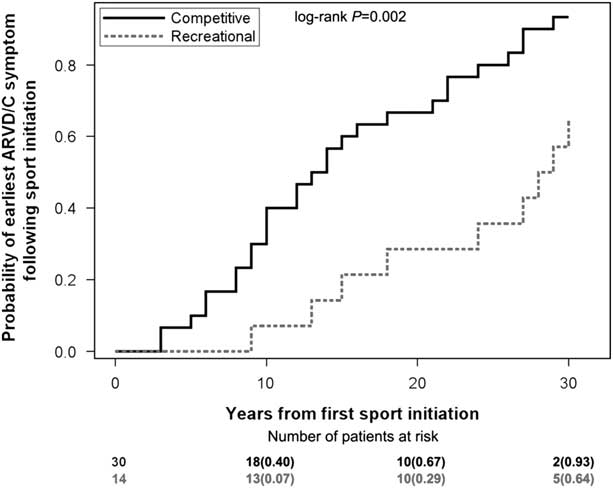

Ruwald et alReference Ruwald, Marcus and Estes 13 studied 108 probands who met the Task Force criteria for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. They found that patients engaged in competitive exercise had an earlier presentation of the disease (Fig 2) and also had a twofold increase in the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias and death when compared with inactive patients and those practising only recreational sports.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier graph showing the time relationship between first sport initiation and first arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy symptom in probands who participated in sports at a competitive (solid line) or recreational (dotted line) level. Reproduced with the permission of Ruwald et al. ARVD/C= arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy.

James et alReference James, Bhonsale and Tichnell 14 interviewed 87 probands and family members with a pathogenic desmosomal mutation to determine their level of physical activity. Endurance athletes became symptomatic at an earlier age and had worse survival from ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure. Furthermore, patients who continued to participate in the top quartile of annual exercise had worse survival compared with individuals who reduced their exercise after presentation.

A recent study assessed the safety of the American Heart Association minimum exercise recommendations for healthy desmosomal mutation carriers.Reference Sawant, Te Riele and Tichnell 15 In total, 28 family members of 10 probands with a plakophilin2 mutation were interviewed. Probands had engaged in more exercise than family members, and the family members who were athletic again had worse outcomes. There were no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in the healthy carriers who restricted exercise to the upper bounds of the minimum exercise recommendations. Their conclusion was that unaffected plakophilin2 mutation carriers should refrain from endurance and high-intensity exercise, but may safely practise the minimum exercise for healthy adults as recommended by the American Heart Association.

The link between exercise and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia has also been examined using transgenic animal models. Several studies have shown that animals that exercise not only have an earlier onset of the disease but also a more severe course, manifested by spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, and right ventricular failure.Reference Kirchhof, Fabritz and Zwiener 16 , Reference Chelko, Asimaki and Wei 17 Another experiment with mice also showed that the training-induced right ventricular enlargement was virtually eliminated by pre-treatment of a cohort with load-reducing agents.Reference Fabritz, Hoogendijk and Scicluna 18

Management

After establishing an accurate diagnosis, the goals of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy management are prevention of sudden cardiac death, minimising arrhythmias and device therapies, and preventing the progression of the disease.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Defibrillators are the only proven therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy.Reference Piccini, Dalal and Roguin 19 – Reference Corrado, Leoni and Link 21 The predictors for appropriate device intervention are overt structural heart disease, history of syncope, previous non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, and increased premature ventricular complexes.Reference Piccini, Dalal and Roguin 19 , Reference Bhonsale, James and Tichnell 20 It is recommended that all probands meeting Task Force criteria have a defibrillator following aborted sudden death or sustained ventricular tachycardia or in the presence of severe left or right ventricular function (Class I); or following syncope or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; or in the presence of moderate left or right ventricular dysfunction (Class IIa).Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22

Pharmacological therapy

Anti-arrhythmic drugs and β-blockers have been used to reduce ventricular arrhythmias and/or defibrillator therapies. Although there are no randomised controlled trials to compare the different anti-arrhythmic drugs available, amiodarone and sotalol are most commonly used.Reference Calkins 10 , Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22 The current Class I recommendation is that patients with recurrent ventricular tachycardia, inappropriate defibrillator interventions resulting from sinus or supraventricular tachycardia, or atrial fibrillation/flutter with rapid ventricular response should receive a β-blocker. β-blockers should be considered in all patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy irrespective of their arrhythmias (Class II).Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22 Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are also used, although there are no clinical trials establishing their efficacy.Reference Calkins 10

Catheter ablation

The outcomes of catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia caused by arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy have been assessed by several studies.Reference Philips, Madhavan and James 23 , Reference Philips, te Riele and Sawant 24 Although catheter ablation in these patients is not curative and it does not prevent sudden death, it improves quality of life by decreasing the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias.Reference Calkins 10 , Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22 Catheter ablation is recommended in patients with incessant ventricular tachycardia or frequent defibrillator interventions despite maximal pharmacological therapy (Class I). An epicardial approach is recommended for those who fail one or more attempts at endocardial ablation, where that expertise exists (Class I).Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22

Exercise restriction

Exercise restriction is key in preventing the onset and progression of clinical arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. The American Heart Association and American College of CardiologyReference Maron, Udelson and Bonow 25 guidelines recommend that patients with definite, borderline, or probable arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy avoid all competitive sports except those with a low cardiovascular demand. Others recommend that even healthy gene carriers be restricted from competitive sports (Class IIa).Reference Corrado, Wichter and Link 22

Cardiac transplantation

Transplantation is reserved for patients with intractable ventricular arrhythmias and/or severe ventricular dysfunction. Tedford et alReference Tedford, James and Judge 26 reviewed 18 arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy patients who underwent heart transplantation. The reasons for transplantation were heart failure (n=13) and severe ventricular arrhythmias (n=5). The mean age at occurrence of the first symptom was 24±13 years, with an average age at transplantation of 40±14 years. Patients who received transplantation had a more prolonged course of the disease and a relatively early onset compared with those not receiving transplantation.

Conclusions

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is an inherited, progressive cardiomyopathy that predisposes patients to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Desmosomal mutations can be found in over half of patients. The updated 2010 Task Force criteria should be followed to avoid over-diagnosis. Treatment of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is focussed on identifying patients at risk for sudden cardiac death who would benefit from defibrillator implantation, but anti-arrhythmic drugs and catheter ablation may also be of value. Patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, including gene carriers, should be restricted from high-endurance exercise.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research or review received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all referenced work contributing to this review complies with the ethical standards of biomedical or medicolegal investigation.