Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 March 2004

We employ qualitative in-depth and focus group data to examine how racial stereotypes affect relations between Black and White undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania. Specifically, we employ the concept of metastereotypes—Blacks' knowledge and perceptions of the racial attitudes that Whites have of Blacks. Our interest is in the accuracy of Black students' beliefs about Whites' racial attitudes to their group, and the consequences of metastereotypical thinking for Black students' academic performance. We find that the Black students in our sample possess some clear and largely negative metastereotypes concerning how Whites generally think about Blacks, and these metastereotypes are quite accurate. Moreover, these negative group images are at the heart of a key campus “problem”—Whites' hostility to affirmative action and the assumption that Blacks are not qualified to be at the university; and, ironically, most Blacks seem to have internalized a piece of these negative stereotypes. These results are a tangible manifestation of double-consciousness—Blacks' perceptions of themselves both through their own eyes and through the eyes of Whites, and evidence of Steele's theory of stereotype threat, in as much as Black students expend considerable energy attempting to debunk the myth of Black intellectual inferiority.

The American Negro is therefore surrounded and conditioned by the concept which he has of White people and his is treated in accordance with the concept they have of him.

W.E.B Du Bois ([1940] 1995)

Stereotypes are an important aspect of analyzing cross-cultural understanding and social inequality. Defined broadly, stereotypes are “cognitive structures that contain the perceiver's knowledge, beliefs, and expectations about human groups” (Hamilton and Trolier, 1986, p. 133). Racial stereotypes, therefore, are the projected thoughts and beliefs that members of one racial group hold about another racial group. They involve “a set of social cognitions that specify personal qualities, especially personality traits, of members of an ethnic group” (Ashmore and Del Boca, 1981, p. 13). Many of these racial perceptions are likely to be common knowledge to all societal groups and are usually passed down from one generation to another. As a general rule, the power of racial stereotyping lies with the dominant racial/ethnic group, since they control access to society's major institutions (Lieberson 1985). Members of subordinate groups are, of course, aware of the dominant groups' perceptions of them.

Du Bois (1989 [1903]) articulates this phenomenon in The Souls of Black Folk, asserting that Black Americans are “shut out from the world by a vast veil” that shrouds them from being fully seen and understood by Whites. Consequently, Blacks experience a “double-consciousness,” viewing themselves through both their own eyes and the eyes of Whites. Racial stereotypes are, therefore, not simply exaggerated beliefs or overgeneralized prejudgments promoting in-group solidarity and out-group disdain (Allport 1954; Ehrlich 1973). Racial stereotypes are also about power and ideology; once crystallized, “these images ultimately indicate (although in distorted ways) and justify the stereotyped group's position in society” (Bonilla-Silva 1997, p. 476; see also Blumer 1958; Bobo and Johnson, 2000).

In this analysis, we employ qualitative in-depth and focus group data to examine how racial stereotypes affect relations between Black and White undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania. Specifically, we employ the concept of metastereotypes—Blacks' knowledge and perceptions of the racial attitudes that Whites have of Blacks (Sigelman and Tuch, 1997). Our interest is in the relative accuracy and social effects of Black students' beliefs about Whites' racial attitudes where their group is concerned. Metastereotypes are salient to the discussion of Black academic outcomes because a Black individual's behavior is not shaped so much by White stereotypes themselves, as by that person's perceptions of White stereotypes about Blacks.

Metastereotypes, we submit, are one manifestation of double-consciousness as described by Du Bois. The dilemma of double-consciousness is especially acute in the predominantly White, highly competitive, Ivy League, where Black students often confront societal stereotypes of Black inferiority and social pathology (Massey et al. 2003; Willie 2003). From an early age, Blacks must learn to deal with the negative attitudes and beliefs about their racial group, and exert substantial energy trying to both contradict the harmful social images held by Whites and, at the same time, keep from internalizing them (Massey et al., 2003; Tatum 1997). Living through the refracted lens of race, Blacks are socialized to understand how others perceive “people like them” and how they may expect to be treated as a result (Fiske et al., 2002; Massey et al., 2003; Operario and Fiske, 2001). The results of our research suggest that Black students exhibit substantial concerns regarding how Whites perceive them, and how, they, as “blue chip” Blacks (Fulwood 1996) can disprove Whites' negative assumptions about Blacks and successfully navigate college.

The belief by many Whites in the intellectual inferiority of their Black classmates and their concomitant opposition to affirmative action are at the heart of our analysis. Most of our White respondents believe that affirmative action opens the doors for Blacks who are less intelligent than they are and ill-prepared for the rigors of the Ivy League. This is a particularly salient metastereotype among Black students who, as a consequence, experience increased anxiety about their own academic performance. These beliefs and associated anxieties are consistent with the stereotype threat hypothesis (Steele 1992, 1998), which posits that a sort of performance anxiety resulting from fears of living up to the stereotype of Black intellectual inferiority is a major source of Blacks' academic underperformance.

Black respondents talk at length about their belief that Whites view them as less intelligent and/or academically incapable of succeeding at an elite private university. They discuss the “pressures” associated with having to prove their worth to White students—that they are, in fact, qualified and intelligent members of the student body. The Black students in our sample are keenly aware that poorer academic performance by Blacks is the expected outcome. Our research questions are three-fold. First, what are Blacks' metastereotypes? Second, are they actually borne out in what Whites say they think about Blacks (and what Whites think most other Whites think about Blacks)? And finally, what are the consequences of metastereotypical thinking for Blacks' academic performance at an elite university, and for patterns of Black-White social interaction?

A substantial body of evidence suggests that, despite meaningful progress, most Whites continue to express negative stereotypes of Blacks (for a recent overview, see Bobo 2001). Much less is known, however, about the racial attitudes of Blacks; in particular, relatively little is known about 1) how Blacks perceive Whites' attitudes toward them and 2) how Blacks respond to Whites' negative images. An important exception to the general tendency to ignore Blacks' racial attitudes is Sigelman and Tuch's (1997) analysis of Blacks' metastereotypes. They found a good deal of overlap in how Blacks' think Whites view Blacks' and Whites' actual adherence to negative stereotypes of Blacks. Sigelman and Tuch hypothesize that Blacks with more sustained contact with Whites will have less negative metastereotypes than those who have little interaction with Whites. This is consistent with the contact hypothesis (Allport 1954), which posits that, in general, increased interracial contact leads to a reduction in racial stereotypes and, as a consequence, improved intergroup relations.1

An important stipulation, however, is that contact must occur between groups of equal status; this means not only that individuals have similarly defined roles, but also that they perceive each other as equals. Evidence regarding the effect of the contact hypothesis is mixed. Sigelman and Welch (1993) find that interracial contact in neighborhood settings has a positive impact on racial attitudes and that such contact enhances desires for integration. Jackman and Crane (1986), on the other hand, suggest that the effects of interracial contact are selective and that intimacy is less important than a variety of contacts.

Yet, contrary to the predictions of the contact hypothesis, Sigelman and Tuch find that Blacks reporting the most contact with Whites also have the most negative metastereotypes. We will argue that these seemingly counterintuitive findings—which we replicate with qualitative data—are tied to Whites' general lack of sustained contact with Blacks (both prior to and while in college), and their tendency to perceive Blacks as intellectually inferior to them. This is witnessed most tangibly in Whites' opposition to affirmative action, as well as their general and college-specific stereotypes of Blacks. In short, we find that White students at the University of Pennsylvania do not perceive their Black classmates as their intellectual or social equals.

Our analysis replicates and extends Sigelman and Tuch (1997) in four important ways. First, we employ qualitative data and methods, and we study metastereotypes in a specific and particularly important context: an Ivy League University. These data provide rich contextual information that allow us to examine how Blacks' metastereotypes operate in a real world context, and to explore the potential consequences of metastereotypical thinking. Second, instead of using respondents' family background characteristics as proxies for prior interracial contact the way Sigelman and Tuch did, we collected detailed information about the actual extent of interracial contact—at school and at home—prior to entering college, in addition to information on the extent of their interracial contact once enrolled in college. Third, we examine the existence and prevalence of Black metastereotypes at two levels—Whites' broad societal images of Blacks, as well as those images that are specific to the collegiate context—and how accurately they reflect White students' stereotypes of their Black peers. Consistent with Sigelman and Tuch, we find that sustained pre-college interracial contact does not appear to decrease Black students' proclivity to negative metastereotypes. Finally, we take the analysis of Blacks' metastereotypes one step further, investigating the extent to which Black students internalize negative stereotypes of their group. By and large, Black students at the University of Pennsylvania do not perceive themselves as “average” Black Americans because they are not on welfare or engaged in criminal activity. Indeed, in their descriptions of themselves as “not like those other Blacks” the Black students we spoke with reveal a tendency toward acceptance and internalization of negative societal stereotypes of Blacks as a group, while at the same time distancing themselves individually from those images. Moreover, there seems to be a deep commitment to “represent the race” in a positive and responsible way by dispelling myths of intellectual inferiority and social pathology. Each of these tendencies—internalizing negative stereotypes of Blacks and the responsibility to dispel those same stereotypes—suggests that these students are especially vulnerable to stereotype threat.

Our data come from in-depth interviews and focus groups with fifty-five Black and White college students at the University of Pennsylvania—one of the most elite universities in the country—collected between Fall 2000 and Spring 2003. Thirty-three of the fifty-five interview respondents are also part of the focus group sample. At the time of the study, all respondents were full-time college students between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two. There are equal representations of students by racial background and gender.

According to University statistics from Fall 2001, Black students represented just 5% of an undergraduate population numbering nearly 10,000 (Princeton Review 2002; Weiss 1995). Respondents were located through snowball sampling—initial contacts led to subsequent ones (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Weiss 1995). There are equal representations of students by racial background and gender.

Though the sample is not representative of all students at the University of Pennsylvania, significant efforts were made to sample students from a wide range of backgrounds and perspectives. We over-sampled Black men as they are out-numbered by their same-race female counterparts on-campus by a two-to-one ratio (Frank et al., 1999; Massey et al., 2003). To protect confidentiality, each respondent has been given a pseudonym.

Although the interview and focus group scripts concentrate on various aspects of how race pertains to the college experience, for this paper we only consider data that directly pertains to the issue of Black metastereotypes. After each intact transcript was transcribed in its entirety, they were analyzed thematically in line with our research questions (Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

The in-depth interview sample includes forty-three in-depth interviews with Black (n = 22) and White (n = 21) University of Pennsylvania students. The first author completed all the in-depth interviews with twenty-four men and nineteen women, using a structured (but open-ended) interview script. Interviews lasted anywhere from two to six hours, often taking place over several sessions. With supervision from the second author, we adapted the survey instrument from the National Longitudinal Study of Freshmen (NLSF), conducted by Massey et al. (2003).

Eight focus groups were conducted with fifty-five students, twenty-nine Blacks, and twenty-six Whites. The in-depth interview script was tailored to the focus group milieu, in keeping with the core themes and concepts of the study. Three trained moderators (including the first author) led the group discussions. Three of the focus groups were stratified by race to study in-group conceptions of race and racial identity. The remaining six focus groups included an even mix of Black and White students. The mixed race groups provided us with the opportunity to witness first-hand the extent to which interracial group context impacts how students from different racial backgrounds discuss race-related topics. Same-race moderators were used for two of the Black groups and for the White group. The first author, a White woman, moderated one of the Black American groups. Data analysis, however, indicates strong continuity in the type and quality of the data collected from each of the Black focus groups. This effort was no doubt aided by the fact that the first author had built rapport with students prior to the focus group—each of the students was also part of the interview sample.

Our focus groups included six to ten students each. Thirty-three of the fifty-five focus group participants also completed an in-depth interview prior to the focus group. The focus group approach gave us the added ability to document how group dynamics affected the ways in which students interpreted and answered our questions. The interviewing process is ideally suited for acquiring detailed narrative data about a particular individual—with the interviewer always determining the course of interaction. In contrast, the focus group setting allows peers to feed off each other; certain ideas are articulated more based on who is in charge of the conversation. The large overlap of respondents in the interview and focus group samples, we believe, gives us a more comprehensive lens for studying how Black and White University of Pennsylvania students understand race as well as the diverse ways that they actualize their racial attitudes and beliefs within the collegiate context2

.Before directly engaging the issue of metastereotypes, contextualizing our findings by considering three issues is critical. First, it is important to consider the social background characteristics of the students in our sample. Second, to fully understand the racial attitudes of our respondents, we must first clarify the nature of their pre-collegiate experiences with people of other races. And third, the attitudes and opinions of our students are also likely to be influenced by the extent of their interracial contact on the college campus itself. We discuss each of these below.

Contrary to White students' perceptions, the Black students in our sample are a varied lot. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of interview respondents, showing that nearly sixty percent of the Black sample report non-native origins, with parents from predominately Caribbean and/or African countries. This compares to only two non-American White respondents; both were of European descent and were not U.S. citizens at the time of the study. White and Black respondents also diverge with respect to their socioeconomic circumstances. White respondents are twice as likely as Blacks to report having parents with advanced degrees, and nearly all of the Black respondents receive financial aid, compared to about one-third of Whites. This pattern of White homogeneity and substantial Black heterogeneity is consistent with recent research by Massey et al. (2003) on college students at elite colleges and universities nationwide. Consistent with other research on racial group differences in collegiate academic achievement (see most recently Massey et al., 2003), the cumulative grade point averages of White students are four-tenths of a point higher than Black students GPAs (3.5 and 3.1, respectively).3

For additional information on respondents, including class year, type of high school, urban/suburban origins, self-reported social class, and region of the country that students came from, see Appendix Tables 1 and 2.

Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics of Interview Respondents

Pre-college interracial contact is measured as respondents' self-reported neighborhood and high school racial/ethnic composition, as well as the racial/ethnic composition of their high school peer networks; summaries of this information are located in the bottom half of Table 1. Overall, both White and Black respondents attended predominantlyWhite high schools; nonetheless, pre-college interracial contact varies greatly by respondent race. Black students tend to come from racially integrated neighborhoods with substantial White and Black populations (and to a lesser extent Latinos and Asians); they also tend to come from racially integrated high schools. In contrast, White students report coming from extremely segregated, predominantly White neighborhoods and high schools. More than two-thirds of Whites attended high schools where less than 10% of the students were Black, compared to Black respondents whose schools were nearly 60% White, on average.

The racial/ethnic composition of respondents' high school friends also differs meaningfully by respondent race.4

For this information, we asked respondents to consider their best friends in high school, those they felt “closest to,” and to report their racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Massey et al. (2003) find that the high school peer network of the average White student in their sample was 81% White, 6% Black, 4% percent Latino, and 8% Asian. Black students, on the other hand, reported high school peer groups that were 61% Black, 22% White, 5% Latino, and 6% Asian (2003, pp. 110–111).

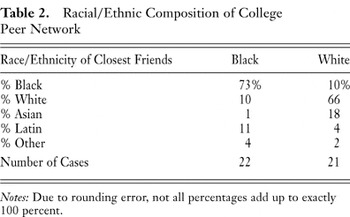

To gauge the extent of interracial contact in college, we asked respondents to tell us about the racial/ethnic composition of their college friendship network, as well as the racial composition and focus of their extracurricular activities. Coming to the University of Pennsylvania for our Black respondents generally means an expanding Black peer group, relative to their high school experience. Though still predominately (indeed, overwhelmingly) White, the University's Black population is substantially larger than was the case at their high schools. Black students tell us that college is a more “Black-friendly” place because they have more potential Black peers to choose from, as well as a plethora of university-sponsored, Black-oriented clubs and organizations. Table 2 details the increasing “Blackness” of Black students' peer networks; the average Black respondent has a college peer network that is nearly three-quarters Black. When asked about their extracurricular activities, most Black respondents reported activities and organizations that were exclusively “Black-oriented”; moreover, half of the Black students said they had lived in the Du Bois College House (a residential space devoted to the celebration and study of Black issues).

Racial/Ethnic Composition of College Peer Network

For the average White respondent, on the other hand, the number of same-race peers decreased in college compared to high school. In college, the average White respondent has a peer network that is nearly 20% Asian, but only slightly more Black. The substantial increase in Asian friends may be attributed to two possible factors—one demographic, the other attitudinal. First, roughly 20% of the undergraduate population at the University of Pennsylvania was Asian at the time of the study (Princeton Review 2002), making them the second-largest racial group on campus and numerically offering the greatest opportunity for interracial contact. Related to the demographic composition of the campus, patterns of social distance attitudes reveal that Whites—both generally and in college—perceive little, if any social distance between themselves and Asians (Bobo 2001; Bobo and Johnson, 2000; Massey et al., 2003). Moreover, the stereotype of Asians as the “model” minority—intelligent, hard-working, and economically mobile (Bobo 2001; Bobo and Johnson, 2000; Kao 1998, Massey et al., 2003) is especially relevant in the college context. Indeed, only one White respondent reported extensive contact with Black students. Due to a shortage of housing his freshman year, this student ended up living in the Du Bois College House; as a consequence, he says, his friendship circle is majority Black and, at the time of his interview, he was residing in Du Bois for his second year in a row.

Attention now turns to Black students' metastereotypes: their perceptions of what Whites think of their group. We asked Black students to list the most common stereotypes that White people have about Blacks in the United States. Because the questions were open-ended, responses varied in content. The most widely cited metastereotypes are reported in the top panel of Table 3. Consistent with the analysis by Sigelman and Tuch (1997), the metastereotypes elicited by Black University of Pennsylvania students can be classified into two main categories: social pathologies associated with Blacks (e.g., violence-prone, welfare-dependent, dangerous, sexual promiscuity, criminality, materialistic/not investment savvy, and/or urban and poor) and more traditional images of Black inferiority (e.g., natural athletes, intellectually inferior, lazy, and as a consequence of their inferiority, whether cultural or intellectual, not deserving of “special treatment”).

Blacks' Metastereotypes

Comparison of Whites' Stereotypes and Blacks' Metastereotypes

The most popular metastereotype is that Blacks are entertainers—generally more musically and/or athletically inclined than Whites. Implicit in this perception is that Blacks are also less equipped for more cerebral pursuits. We include athleticism in the entertainment category because Black respondents tended to equate Black athleticism with White entertainment; there was also a tendency for Blacks to suggest that Whites perceive Blacks' musical talents as limited to Black-oriented, generation-specific pursuits such as rap and hip-hop. In his commentary, John, a sophomore, explains:

… A lot of White people perceive Black people as entertainers. Whether it be on the athletic field, or you know, on stage or somethin'. I think they're perceived as different—you know, [we're] amusement, [we're] entertainment.

Joe makes similar statements: “I think that most White people view Blacks as entertainers, rappers, basketball players, singers—things like that.”

Jill says that Whites tend to automatically assume that she can sing and dance because of her skin color. When confronted with these assumptions, she explains how she defies these stereotypes.

Jill: [White] people ask if I can sing and dance. [Laughs] … I say ‘?no. I can't sing. I guess I can dance, but I'm not this out-of-control dancer. I guess they think, culturally, we're limited. Or, we're culturally narrow-minded….’

Kim believes that White perceptions of Blacks as entertainers are also directly correlated with beliefs about Black inferiority.

It's always like a level of inferiority. Oh, well, I'm in the entertainment field. Or, I'm in the athletic field. You know … that's what's seen, you know, well, okay, they're making some money. They're successful.

Another common metastereotype—that Blacks are criminally-predisposed—is linked to two additional social pathology metastereotypes: that Blacks are violent and/or to be feared/dangerous. Nineteen Black respondents believe Whites perceive Blacks to be criminals, fifteen said that Whites believe that Blacks are to be feared/dangerous, and twelve said that Whites see Blacks as violence-prone. Those Black students articulating the criminality metastereotype also suggest that, for Whites, this is tied to the perception of Blacks as unable and/or uninterested in earning a “legitimate” living. As Kim explains:

White people, just automatically assume we're inferior. Whether it's growing up, in the youth stage, or the street level, or they're all like criminals [Black people], or drug addicts, or this or that…

Sandra states that metastereotypes relating to criminality are primarily directed at Black men and those of darker hue.

It seems as though people who are darker, well historically that there seems to be more, like it seems like it's harder for people to relate, you know, like there's a stereotype of like the Black man that he's violent or whatever, or if he's dark, he's very big.

Black student's responses related to Black criminality are not derived simply from their perceptions of what White people think of Blacks, but are often tied to their own personal experiences with racial profiling while students at the University of Pennsylvania. This is especially true for our Black male respondents. The University of Pennsylvania's expansive picturesque campus is located adjacent to West Philadelphia, a sprawling, predominantly Black, working-class neighborhood—often labeled a ghetto by university students and outsiders. Anecdotally, respondents said that prospective students are warned by campus tour guides, current students, and faculty not to live above 40th Street, the apparent physical divide between the affluent safety of the university and the perceived crime and danger of West Philadelphia. Matt rationalizes White fears as partly situational, a result of the university's location.

… Considering where we are, we're right next to this large Black population which is lowerclass, a lower-class Black population, and so … when I walk down _______, and I don't have a backpack with me, people think that I'm, you know, from the neighborhood. And, so, people just treat you differently. Like, they might—they'll look at you cautiously. And, when you're in the buildings, they're like: Why is he in here? Things like that … I mean, if I'm wearing a bubble jacket and wearing some boots and no backpack, you know, I guess, I look like—I dress like someone else from the neighborhood, which is understandable.

He goes on to share that he often modifies his behavior to curb White anxieties.

I kind of find myself thinking a lot before I leave my house, like: Do I look too threatening? Like, maybe I shouldn't wear this, maybe I shouldn't wear that. Sometimes, when I didn't even need my backpack, but I'd carry it with me anyway because…

Mike is also sensitive to how his presence on campus may magnify White fears, especially those of White women. Like Matt, he works to alleviate their fears by modifying his own behavior.

You get the vibes a lot of White students feel uncomfortable around you, like I mean especially walking down Locust Walk at night. Many times many [White] girls pull over and stop so … I mean that's everybody, I mean everybody does that, that's just across the board. But in me recognizing that, I know, sometimes I might do something extra to alleviate that fear for them … I know if I'm walking past and I'm coming behind you, I'm gonna move to the side so you can [pass] because I know that they're probably [scared].

Several Black men asserted their belief in the metastereotypes about Black men being dangerous, and/or predisposed to crime and violence. The gendered nature of this metastereotype has its complement among our Black female respondents. Specifically, several Black women described Whites' image of the ‘strong Black woman’ as fuel for White discomfort with and alienation from Blacks. Kim explains:

Oh … with the Black female—the strong Black female image … But, the Black woman who just has so much attitude, this and that, and you know, she's too progressive, too proactive, too this, and too that. I think we see a lot of that. And, that as a negative thing… That being proactive and fighting for your certain causes, is a negative thing.

Sara's comments relate specifically to her encounters in the classroom:

… it's just a feeling you get sometimes being in a classroom from teachers or other students even… Sometimes everything you say is interpreted as the angry Black female. I find myself in that role in so many classes.

Thus, Black students—both male and female—express strong beliefs that Whites find reason to feel minimally uncomfortable (for the women) and often unsafe (for the men) around Blacks, and that this has serious consequences for their own behavior.

Consistent with perceptions of Blacks as criminal, dangerous, and/or violent noted above, is the belief that most Blacks are part of the urban underclass. Indeed, twenty-one of the twenty-nine Black respondents agree that Whites perceive most Blacks as urban and poor. This metastereotype relates to several other widespread societal images of Black inferiority, including the perceptions that Blacks prefer welfare dependence over work, are not deserving of what they have, are unintelligent, sexually promiscuous, lazy, and materialistic, but not smart with money. The ghetto image was powerful in the minds of Black respondents; they perceived Whites as viewing Blacks as not only poor, but also responsible for their own impoverished condition. Jessica's comments touches on several of these metastereotypes:

[Whites think] that they [Blacks] all come from the working class or the ghetto, think that they're not, that you're never going to see a rich Black person, that there are no Black millionaires, that they don't go to school, they don't get degrees, they're not as qualified to do the same types of jobs, even if they may have been accepted into a position.

Susan believes that she herself is often perceived as a young welfare mother when she is with her infant son.

People see me, you know what I mean… I also look a lot younger than I am, you know what I mean, so a teenaged mom, not really doing anything while living at home with my mother, you know what I mean… ? And you get a stereotype. And I knew that … beforehand, but to experience it is something different.

Other common themes include the tendency for Whites to believe that Blacks are, generally, less intelligent than Whites themselves are and, as a consequence of their intellectual or cultural inferiority, less deserving. This is a general (meta)stereotype that is particularly salient for the Black students we interviewed.

Carol also feels that Whites do not think Black people can make it on their own without assistance.

Everything we have is hand-outs. We didn't necessarily work for it and we're not necessarily deserving of it.

Finally, the perception that Blacks cannot and do not manage money well—that they prefer to live in the moment, are too caught up with the fast life and are, therefore, financially irresponsible—was a common metastereotype. John provides the popular image of a rapper and how his lifestyle is perceived by Whites.

I think they're [Black people] typically categorized as having baggy jeans, probably rockin' Tims a lot, a lot of jewelry, things like that. The ‘Bling-Bling’ or whatever…. And, like, um, if you see a rapper, the thing is, their sole purpose in life is attaining the material life which comes in the form of money and girls … jewelry, cars, all that type of stuff. I think that Black people are perceived as very materialistic…

Christine expresses similar sentiments.

Oh, if a White person has money, you know, they know what to do with their money and how to invest it. But, if a Black person gets money, oh, they blow it all on drugs and stereos, cars, crazy clothes.

Together, our findings to this point suggest that Black metastereotypes are overwhelmingly negative. Our respondents do not feel that Whites look at Blacks in a positive light on any dimension: the overarching theme is that Blacks are categorically inferior to Whites, engaging in deviant behaviors such as crime and drug-dealing because they can not achieve parity in mainstream [White] society. Moreover, Black male respondents discussed specifically how they deal with racial stereotypes as students at the University of Pennsylvania. They work to allay White fears, going out of their way to appear less threatening, always treading on “thin ice” when out on campus. So, whether or not they've internalized stereotype threat, it does make them more conscious of how they interact with their White peers. The negative emphasis of Blacks' metastereotypes is consistent with results of Sigelman and Tuch's (1997) analysis, with an important exception: using a survey instrument, the Blacks in their study also acknowledged positive Black metastereotypes—Blacks are patriotic, good parents, and religious. In our open-ended conversations with Black students, there was no mention at all of positive metastereotypes, suggesting that these images are far less salient in these Black students' day-to-day interactions with Whites.6

Athleticism is also a common theme in Sigelman and Tuch's (1997) analysis; however, the authors assert that it is unclear whether Blacks feel that this metastereotype is positive or patronizing. Our results suggest that it is more likely the latter.

To what extent do Blacks' metastereotypes accurately reflect White's stereotypes of Blacks? To address this important question, we compare the metastereotypes of Black students to the racial stereotypes of our White respondents. As we did with Black respondents, we directly questioned White respondents about what they believe are the most common popular stereotypes held by Whites about Blacks. A summary of this comparison is located in the top panel of Table 4. On the whole, we find that our Black respondents' metastereotypes are quite consistent with the perceptions of Blacks elicited from our White respondents. In general, White respondents express racial stereotypes that are unequivocally negative, and this is largely consistent with their patterns of interracial contact, both prior to and once at college. Black criminality is at the forefront of this discussion, with nearly 70% of White respondents (18 of 26) acknowledging the primacy of this stereotype. Here again, the “Blacks as criminals” stereotype is tied to perceptions of Blacks as violent and poor as well. Tim reveals the common White perception that Black men are ‘dangerous’ and prone to physical violence.

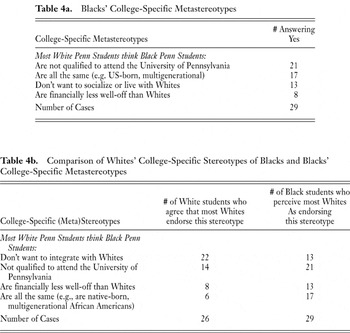

Blacks' College-Specific Metastereotypes

Comparison of Whites' College-Specific Stereotypes of Blacks and Blacks' College-Specific Metastereotypes

Interviewer: What are some common stereotypes that White people have of Black people?

Tim: Dangerous… Especially, if you're male… If you're walking, a Black person is going to come up to you and beat you up.

In a focus group with other White students, Lisa shared her fear of the Black people in her neighborhood. She lives in an off-campus apartment just above 40th Street. Lisa is from a small wealthy suburb in the Northeast.

Lisa: … And, I think of when I'm by myself, walking home at night and I see a Black person—I do get nervous at times… Because of the crime reports that you read in the _____ [name of campus newspaper] everyday. You know, things happen on the block that I live on.

Rich also lives above 40th Street and admits that he sometimes fears for his safety if he sees a Black man walking near him, especially late at night.

Yeah, I mean I think that there is—I mean I think like in terms of like the young Black male as being a thug or, you know, a gangster or something is very common. Like I definitely see it even in myself, like when I go home to _____ Street, I normally often get home like midnight … even if I'm on my bike and I see like a Black man coming towards me just like walking … like my heart rate probably increases, you know, I'm more nervous. And if it was like a White female or something, I'm not gonna even like bat an eyelash, you know. So I think that there's definitely, that's like the, I mean the young Black male is like definitely stereotyped as being like a criminal…

Similarly, the majority of White respondents also endorsed the stereotype of Black people as poor, and tended to associate poverty with being uneducated and engaging in deviant (criminal) behavior. Amanda and Zak have similar perceptions:

Amanda: Stereotypes [about Blacks] are very negative. So, poor, they're uneducated. And, all the men are criminals, too. I think those are the pretty common stereotypes. I mean, among White people.

Zak: Poor, violent, would be like common stereotypes. Yeah, poor, violent, uncultured, sort of the same things that have been around forever.

Rachel, however, wasn't sure if this White perception of Black urban poverty measures up with reality.

… I know that it's most people's perception that most Black people living in America are urban and poor… But, then I was trying to think if that's actually the correct—if that's the truth or that's our perception.

Some White students admitted that their assumptions about Black people stemmed from their lack of personal contact or interaction with middle class or affluent Black people. Chris told the other students in his (all White) focus group about his first experience in a Black middle-class neighborhood, not far from campus:

Just about two weeks ago, I discovered the Black middle-class for the first time. We were going to see a movie and it was only playing at the _____ Street Theatre. So, we went all the way out there—we took the ____ [name of transit line], or whatever. And, it was the Black Middle Class. There were nice stores and everything and you could tell all the stores were typically African American. It was kind of weird for me because I've never been in a Black middle-class place before… You guys should go! It exists.

Beth also questioned her ignorance of middle-class and/or affluent Black people. She grew up in a medium-sized city in the Mid-Atlantic and is one of the few White participants who went to a public high school that was fairly well integrated.

And, I don't know how big it is, and I have a feeling that because I tend to pay attention to different issues, I guess the middle class is bigger than I think…. The Black middle class. Yeah. And, I have plenty of [Black] friends who are not as poor as people living in boxes in the street, you know what I mean? But, I was listening to how we are describing the average Black person, and it's all like, poor, poor, poor, poor, poor. I think in my head, that is kind of the average, but I know that I'm not acknowledging more of the middle class experience…

Once again, even though our interview questions are open-ended, three of the six most widely-cited Black metastereotypes and White stereotypes (Blacks are lazy, unintelligent, and violent) are consistent with those reported by Sigelman and Tuch (1997).7

Sigelman and Tuch find that over half (54%) of White respondents characterized Blacks as violent, 31% of Whites believed Blacks were less intelligent, and 47% of Whites perceived Blacks to be lazy.

Sigelman and Tuch report that 76% of Blacks perceived most Whites as endorsing this stereotype; however, only 31% of Whites actually accepted this image of Blacks.

Overall, these findings suggest that our sample of Black students hold metastereotypes that are strikingly accurate, particularly those related to perceptions of Black criminality, poverty, and proclivity to violence. The comments from our White respondents also suggest that their lack of interracial contact may play an important role in the perpetuation of these attitudes. Finally, it appears that our Black respondents are justified, not only in their beliefs about White students as fearful of them, but also about their adherence to beliefs about Black intellectual inferiority.

What do Black students think White students think of them as students? How do these metastereotypes form the more general metastereotypes outlined in the previous section? Equally important, how accurate are Black students' college-specific metastereotypes, and what, if any, are their consequences for Black students' collegiate experience? First, to get a sense of what Black students' college-specific metastereotypes are, the bottom panel of Table 3 summarizes responses to our query about what they think most White students think of Blacks as students at the University of Pennsylvania. For comparative purposes, the bottom panel of Table 4 compares these responses to White respondents' answers to this same question. The most salient issue mentioned by both Black and White students was Affirmative Action. Fully, three-quarters of Black respondents and more than half of White respondents agreed that most White students endorse the stereotype that Black students are “not qualified to attend the University of Pennsylvania.” That is, that Blacks did not earn their place at the university on their academic merits; rather, they are there to fill a ‘quota’ whether it is because of their athletic prowess or, because the University of Pennsylvania wants a certain number of Black students enrolled each year for purposes of racial/ethnic diversity.

Another salient theme is that of Black ‘self-segregation’ on campus. While the majority of both White and Black respondents indicate a preference for living and socializing primarily with same-race peers, they have varying interpretations of this decision on the part of Black students. Most of the White students relied on two explanations: 1) they believed that the Du Bois House allows Black students to self-segregate and promotes anti-White attitudes, and/or 2) some White students suggested that, like Blacks more generally, Black University of Pennsylvania students assume that all Whites are racists and this, too, discourages interracial social interaction. Conversely, many Black respondents blame White students' anti-Black hostility for promoting racial separation, while also lamenting the everyday frustrations of being in a place designed to honor White history, White knowledge, and White cultural practices at the expense of the Black experience (Feagin et al., 1996). To many of these Black students, Du Bois College House serves as a refuge from the enduring stresses of being Black in such a “White space.” We discuss each of these themes in greater detail below, in a manner consistent with the previous section: first, Black students' college-specific metastereotypes, followed by a discussion of their accuracy.

In their commentaries, Black students speak at length about their belief that Whites do not think they are intelligent or academically-prepared enough to be at the University of Pennsylvania. Related to this perception is the pressure that derives from having to ‘prove’ oneself to White students—demonstrating that they are qualified, intelligent members of the student body. Particularly noteworthy is that Black students reporting a high level of pre-college interracial contact are at least equally inclined to adhere to this metastereotype.

Devon believes that Black people are not given the benefit of the doubt regarding academic ability:

[Whites believe] we just want to take welfare and be happy and merry and I think that they also have the impression that we're not as smart… Like, I think that a lot of them [White people] are really surprised if you've been to a good school or your SAT scores are or your grades are good. I think they're like: Wow! How did you manage to pull off something like that?

Devon grew up in an affluent, majority White Northeastern suburb and attended an elite day school prior to coming to the University of Pennsylvania. He has no Black friends and does not participate in Black-oriented activities on campus.

Sara, a senior sociology major with an A− grade point average, shares her feelings about White students' perceptions of Black students as unqualified to be at the University of Pennsylvania.

… Both of my parents make a lot of money as physicians right now and live in a nice area. But, I had to work so much harder in high school to get where I was and right now, people still question whether I belong at UPENN. They question things like my SAT scores, they think I'm here because of affirmative action… I think I'm a lot more qualified than a lot of White students here. I think that I'm questioned… You can never be sure. But, things like that have happened repeatedly in my life that illustrate to me that a lot of things that I've had to overcome have to do with race. Even though, as far as class, I'm on a comparable level with most White people, if not in a better situation.

At the time of her interview, Sara receives no financial aid. Both of her parents are physicians; she attended one of the top public high schools in her area and has done consistently well throughout her academic career.

Jessica shares an experience of direct confrontation by a White student who believed that Affirmative Action explained Jessica's presence at the University.

… This girl, she said in reference to me, she said I was going to UPENN, said it was only due to affirmative action… [it] wouldn't have been too big a deal, only she had gone on about all her connections to the Admissions Office here because her brother went to UPENN… all I did was check a little box that said Caribbean American… I think that we feel the need to prove that we're really ten times better than people think we are because of affirmative action, things like that, oh, you probably got in here, you know, whatever.

Stressed out by Whites' assumptions that his race marks him as inferior to White students, Matt explained how his skin color negatively affects the treatment he receives in the classroom, and the added pressure he feels to perform well academically and counter what he sees as the prevailing campus stereotype among Whites: that of Black intellectual inferiority:

… Going to class because I'll be the only Black person in class. That's almost every class. I guess it isn't too hard because most of my high school classes were like that, but … It is different here because there's this idea that, you know, affirmative action is why you're here … sometimes you just seem to get that vibe from people… When you perform at the same level as them, they're surprised that you can perform at that level… Like, if we're having a discussion in class, and I'll say something like, relatively intelligent, you know, people will be like: Gee, I didn't know he could… I didn't know he was smart. You know? You, being Black, they have the idea that, you know, you're inarticulate or can't graduate.

Brian is similarly convinced that the myth of Black intellectual inferiority will haunt him even after graduation, despite the good grades he earned at this Ivy League University. In order to convince employers' that he is as qualified as White candidates, Brian assumes that he has to academically outperform his White counterparts.

… I think most of the Black students here, and that's just in general, I mean if you're a White person coming out of UPENN with a 3.0 and you're a Black person coming out of UPENN with a 3.0, I think most people are gonna look at the White person with the 3.0 saying, oh, you know, he's well-rounded, had a good time… academics probably weren't like the most important thing… Whereas the Black person, oh, he's an affirmative action case, that's why he got a 3.0. So it's important for that Black person to have that 3.5 and the 3.7 where I don't necessarily think it's as important for the White person. I don't know, that's what I think. It's a deep, heavy subject.

Scott's comments about affirmative action, however, are more nonchalant. Rather than thinking about whether or not he was judged differently based on his race, Scott perceives the playing field as level since his matriculation. Scott is a junior in the Wharton School, the University of Pennsylvania's top-rated business school program.

If we go to colleges, [Whites think] we probably got in through affirmative action, and stuff like that … if it's because of that, so be it. I mean, I'm getting my education… At the end of the day, I got, I got a piece of paper that says I graduated from Wharton.

Nearly half of the Black students in our sample (thirteen of twenty-seven) stated an explicit preference for living and socializing primarily with other Blacks; however, their reasons for this preference were markedly different from Whites' perceptions of Black separatism. Many Black students spoke of the University of Pennsylvania as a ‘White’ place that does not welcome or acknowledge the diversity of Black students or their needs—as such, banding together helps to alleviate some of the strain of being Black on an elite, highly-competitive, and overwhelmingly White campus. These feelings resonate fairly consistently with Black students from a variety of backgrounds; the sustained interracial contact prior to college reported by many of these students did not increase the desirability or the perceived ease of socializing with Whites on campus. Instead, Black students from predominately White backgrounds were even more likely to gravitate toward Black peer groups in college. Weary of existing in a White world with little Black companionship, they rushed to align with the Black community at the University of Pennsylvania. In fact, for many, college was the first time that they could choose to interact with a sufficient number of other Blacks.

In her interview, Jessica partly attributes Whites' perceptions of Black segregation on campus to Whites' lack of interracial contact prior to University of Pennsylvania. At the same time, however, she does not deny that many Black students do prefer to live only with their same-race peers. Jessica, a junior, has never lived in Du Bois College House, but spends a great deal of time socializing with friends there.

It ends up being the perception that we're very segregated—to a certain degree, we want to hang out with people like us—but, I think a lot of what surrounds us, is a mystery for them…. I feel like they're kind of afraid to approach us because they might possibly feel like we're a big Black cloud of students!

Susan concurs that White naiveté about Black people influences how Whites perceive Du Bois. Susan attended high school at one of the most elite prep schools in the Northeast, where she was one of only a handful of Black students. She spent her first two years of college in Du Bois, and would have lived there her third year, but moved off campus because she was pregnant with her first child.

… People from the outside are quick to pass judgment on us… And just, you know, they're sort of perceiving Du Bois as like this monolithic environment [but] ignoring the fact that we have students who are Caribbean American, African American … [Du Bois] is very underrated by people who've never been there … like the stereotypes, of course, are just like oh, you know, Black people trying to segregate themselves, you know, and whatever.

Susan's comments clearly feed into the metastereotype and corresponding White stereotype that ‘all Black people are the same.’

Stacey argues that White students fail to realize the importance of their status as the numerical majority on campus, and do nothing to promote more interracial contact. The onus is always on the Black students to make the initiative.

… They think [Du Bois] shouldn't be there… But, no one's really trying to do anything different. So, why get on Du Bois, if you're not leaving the Quad? … I mean, it's got to come from both sides.

In the focus group with other Black American students, Stacey and Laura explained more about how White students associate anti-White sentiment with living in Du Bois.

Laura: [They think you] hate White people, especially at UPENN.

Stacey: You live in Du Bois. You don't let White people in because you block the doorways when they try to come in.

Interviewer: Yeah. I have been blocked several times. [said jokingly].

Stacey: Yeah. That was my watch. [said jokingly]. I said: Hey! [The White girl's] comin'! [laughter].

A majority of Black students said being able to socialize and live with other Black people is crucial to succeeding at the University of Pennsylvania. Constantly confronting a hostile racial climate, they believe, necessitates the existence of the Du Bois House not just as a living space, but a meeting place where Black students can come together away from the pressures of rest of the campus environment. Susan associates her love of the University of Pennsylvania with that of the Du Bois House.

… First of all, Du Bois has been my absolute favorite part of my life at UPENN, so far. And I still consider it my home … It's a nice family environment, which is good when you're away from your family, you know… Du Bois is so much more than just a place to live, you know what I mean, like everything is like—you can get involved in the activities through there. They have academic channels there… there's so much going on in the House that people just think, you know, we just want to go in a place where, you know, it's all Black people and stuff.

In addition to living space, Du Bois has several classrooms, study, and rehearsal spaces for academic and extracurricular groups. Du Bois frequently hosts outside speakers and various cultural events. As one Black student put it, “it's the social mecca for the Black community.”

Du Bois has served as an important social support for Paul as well. Paul has lived in Du Bois for two and half years. He is very active in Black student life and all of his close college friends are Black—most of whom are brothers in his fraternity.

… you usually can find someone to relate to … I can always find someone in Du Bois who has already taken the class or is taking the class and might get the notes from them, even if I don't know them.

Many Black respondents likened Du Bois House to a refuge where they could get away from the stresses related to being Black in such a White place. In the presence of other Blacks they felt they were able to unwind and take solace in the fact that there were others who were in the same boat. They welcomed the time when they did not have to feel compelled to ‘represent the race’ in the classroom, or deal with various other race-related issues. Sara, a senior explains:

I think [Du Bois] is really important. I think especially at a school where there's so few ethnic minorities, I think it's important for those people to have a community. And just people to feel comfortable with—that understand like your culture or norms or some of your values because I think people overestimate the amount of isolation that happens. They think when people live in places like Du Bois that they never have interaction with anyone else… For me it was the only time of day where I could go home and be like: Whew, I know everyone here, no one's going to ask me about my hair today or look at me funny or think I don't belong here.

Sara's high school experience was predominately White. Like many of the Black students in our sample, Sara was one of the few Black students in her honors classes. Susan had a similar high school experience. Despite attending an overwhelmingly White, elite private day school, Susan still feels uncomfortable in classes where she is the only or one of a few Black students.

I'm still, even after going to a high school like _______ [name of high school], I'm still uncomfortable with being the only African American student in my class.

Although Mark has never lived in Du Bois and has a predominately White peer network, he also sees the importance of having a space on campus that is oriented toward the needs of Black students. Contrary to the need for a save haven, however, Mark points to the opportunity for Blacks from majority-White backgrounds to get to know and socialize with other Blacks at college:

And the argument is that, well, for the first time in their lives they have the opportunity to be around other people who look like them, you know, and probably the only time, on a regular basis, you know?

Although Peter went to an elite boarding school, he shares how tiring it is to navigate college as a Black student:

… One difference between Black and White people that I see is that Black people have the burden of Blackness. You know what I'm saying? And, the need to feel like you gotta represent … I don't know exactly. But, I know I got high blood pressure. You know what I mean?… There's just a lot of external pressure that goes on with Blackness.

Clearly, the ‘burden’ of Blackness is a powerful theme resonating throughout Black students' commentaries. The Du Bois House, students argue, helps them to cope with their minority status, providing a comfort zone for feeling safe and understood. This perception of ‘self-segregation’ as a response to White hostility is vastly different from that of White students belief that it represents and/or fosters anti-White sentiment among Black students.

Though somewhat exaggerated, Black students' college-specific metastereotype that White students perceive them as unqualified for the University of Pennsylvania, is largely consistent with Whites' stated perceptions. The bottom panel of Table 4 shows that over half (fourteen of twenty-six) of White respondents do support the prevalence of the affirmative action stereotype. It was the White male students who made the most powerful statements regarding this issue, reaching consensus regarding the intellectual and academic inferiority of their Black peers.9

As Sigelman and Tuch argue in their paper, it is possible that White students may have understated their feelings on this particular issue as well as on other issues for fear of being labeled as racist by the interviewer or focus group moderator. Moreover, because we relied on open-ended questions to get at these issues, it is possible that we did not capture all of the students' beliefs about any single issue.

Black people with lower scores and lower GPA's are taken over White people with higher qualifications, and that does cause concern for me… I'm not against affirmative action entirely because I do feel that there are inherent disadvantages… I believe that the school sort of oversteps its boundaries…. The one class I took on race and ethnic relations, which was predominantly Black students… I honestly felt that some of those people, certain people in that class were not qualified to be at this school … and I think that's because they had poor argumentative skills and I just thought wow, a lot of the people in the class were terribly inarticulate, expressed their thoughts poorly. I was thinking to myself, honestly, these people are not on the same level as me intellectually… There were probably ten White people to thirty Black people.

Tony asserts that he, too, believes Black students are not on the same level as Whites. He states:

I would guess that just sort of saying that perhaps the majority of Black students at UPENN are from a lower income, lower educational background.

And, while Tim argues that he is not against affirmative action programs in all cases, he is not in favor of race-based initiatives.

… I think that like there is definitely like inequalities in like the educational system … there's so many factors that go into like, that determine like how you do academically that I think you can't tell just based on like merit… I mean therefore I support affirmative action but not, like I support it more like affirmative action based on economics…

Lastly, Chris says programs like affirmative action put Black people in jobs they are not really qualified for. In his commentary, he refers to his friend's term, “the psuedo-educated Black male,” as a way of capturing his feelings about Blacks who have not earned their positions in corporate America:

I think there's definitely something to that [affirmative action]. A friend of mine has a word that he uses… He's says when he's in a situation where he meets a well-dressed Black man, he'll say: Oh, it was one of those “pseudo-educated Black males.” … I think it's something like a Black male who dresses the part and tries to be ‘White’ and be in a certain situation, beyond a certain social status… So, I think, I don't really use that term myself, but when he said that, it made me—I took notes at that time … it was some kind of thing where this guy was serving him and was dressed up or whatever. And, [mimics White friend]: He didn't know what he was talking about. These guys, they come across like they know what they're doing… But, when you scratch the surface, then they fall apart. I could see where he was coming from … I can imagine him being in a situation like that.

The White women in our sample are more inclined to talk about “what they've heard” regarding Black students' qualifications. Lisa says she has been privy to hearsay about Black students' qualifications. As a member of the track team, she is aware of the stereotype that some Black students got into the University of Pennsylvania not because of their academic strengths, but because of their superior athletic capabilities.

Most of the Black people I talk with are athletes … there are stereotypes about athletes, [the] stereotype is, “They're here because they're athletes,” or “Oh you got in because you're an athlete,” or “They just want to fill a quota”… lots of athletes that I know are Black, if anyone thinks of a reason, it's because they're an athlete.

Mary, a junior, shares a direct statement about Black students and affirmative action from one of her friends:

I think one of the stereotypes of Black students is that they don't deserve to be here, they're here due to Affirmative Action… I had one friend who said, in reference to a Black student, “Oh there's affirmative action”…

While these results suggest that Black students' college-specific metastereotypes related to affirmative action and, more generally, Black intellectual inferiority are confirmed by a majority of White respondents, they should be interpreted cautiously. This sample is by no means representative of all White or Black University of Pennsylvania students. At the same time, however, it is evident that these respondents expressed their views with considerable ease; White students, and particularly White men, were very open about their disapproval of affirmative action, and used it to symbolize [what they perceived as] Black inferiority. This tendency suggests that, Black students' concerns are justified, since even a small minority of Whites with such beliefs can adversely affect the campus racial climate.

White students tend to blame the existence of Du Bois College House for the lack of interracial student interaction. Located at the edge of campus, Du Bois is far from the goings-on of the Quad and other more centrally located residences that are also predominantly White. The House is one of the smaller residences on campus, with living space for about 200 students. In addition, White respondents say they are wary of cross-racial interaction because they perceive Blacks as believing that all White students are racist. The bottom panel of Table 4 shows that three-quarters of White respondents (twenty-two of twenty-nine) believe most Whites view Blacks as ‘separatists' with no interest in socializing or living with Whites. However, thirteen of the twenty-nine Black respondents subscribed to this metastereotype. While Black respondents remarked that the Du Bois House was a valued residential and social space, they did not agree that the House cut Black students off from the rest of campus. Moreover, they cited White students’ lack of knowledge about Black people and anti-Black hostility as key reasons for living in Du Bois.

Colin, a junior at the time of the interview, argued that Du Bois should not be a housing option for Black students because it decreases the likelihood that they would choose to live in other residences. College, Colin believes, is supposed to be about ‘diversity’ and interacting with people from different backgrounds. Colin's freshman dorm was overwhelmingly White, not unlike the student body of his high school. He admitted that he does not have any Black friends, nor has he gone out of his way to get acquainted with a single Black student; his primary friendship circle is all White.

… I think that just completely goes against, if UPENN really wants to strive to be diverse and wants to attract all different kinds of people, then why would they essentially give them a place where they can segregate themselves? … I don't think UPENN should make that a viable option… there were no Black people in my hall freshman year. And I think that's a shame… The diversity in my hall was about the same as my high school, it was overwhelmingly White and there were a couple of Asians…. I believe that Black students self-segregate themselves … and I do believe that Black students actively segregate themselves and White students do not do the same thing.

Later in his interview, Colin said that Du Bois House promotes ‘latent racism’. Colin has never been inside Du Bois because he thinks that Whites are not welcome there. He does not want to experience any discomfort associated with being White in a majority Black space.

… I just don't, like I would be uncomfortable, for instance, hanging out in the Du Bois House. I think that's a form of latent racism… It's there, but it's not expressed… I don't know. I think that truthfully a very, very pro-Black environment alienates White people, it certainly alienates me… I just think that it's an uncomfortable racial climate in that sense, but it's very minor. I don't day-to-day ever feel uncomfortable being White.

Laurie, a sophomore, also thinks that her Whiteness bars her from entering Du Bois. She grew up in a suburb of Denver, Colorado, with no Black neighbors. Laurie attended a nearby public high school where about 20% of the student body was Black, but she has never had any Black friends.

Laurie: … I don't know like sometimes I am afraid to go [to Du Bois] for some reason just because I feel like I wouldn't be accepted just because I am not Black.

Interviewer: And that matters there?

Laurie: I don't know I have never been there.

Emily, a freshman at the time of her interview, lived in the Quad. She had never been to the Du Bois House either, nor is she sure how she feels about its existence on campus. Emily attended an elite parochial high school, though she and her family are religious Jews.

I guess I have mixed feelings about [Du Bois] because I am not Black. So, I don't exactly know… I wouldn't know if there is a certain comfort in having that there for them or if it would be hard for them because I guess Blacks are a minority here… But I think it is a shame that it makes the rest of the campus not as diverse.

Like Colin and Emily, George faults Du Bois for not making his college experience more racially diverse. The dormitory, he says, is crucial to how students' make friends at the University of Pennsylvania; if his friend Devon hadn't lived near him in the Quad freshman year, George believes he would not have any Black friends. The Quad is actually a collection of centrally located residences halls where over 1,000 students—mostly freshman—live. Each class year is about 2,400 students. With the exception of Devon, George's friends are all White and Jewish.

I really think [Du Bois] is the worst thing that's happened to race relations at UPENN because all the Black people live there and you're friends with the people you live with. That's pretty much the way it works out. Almost all my friends live in the Quad—easily 95 percent of them lived in the Quad freshman year.

Moreover, George assumes that the students who elect to live in Du Bois are from majority Black environments and thus feel uncomfortable around White people. His friend Devon is especially well-versed in White ways because he lived in places and attended schools where Whites were the majority. George is from an affluent suburb not far from the university. And, although he did have a few Black friends in high school, George explained that they were all from economically privileged backgrounds like his own, and Devon's.

[Devon] he came from a much more White background than most of the Black kids … the majority of the Black kids here, come from predominantly Black backgrounds. [Devon] comes from [White] boarding school… I mean I think that those who come from more White backgrounds are more comfortable around White people.

But, George also admits that being Black in a predominately White place may involve ‘compromising’ a bit of your racial identity in order to fit in. Black students who live in the Quad tend to ‘act more White’ than those who live in Du Bois. According to George, being Black at the University of Pennsylvania is very different than being White at the University of Pennsylvania. With few exceptions, George perceives Black University of Pennsylvania students as coming from majority Black, urban areas—they speak slang and dress in fashions characteristic of urban America. White students are generally preppy in clothing style, speak ‘proper’ English, and are not as into the Hip Hop music scene.

What does it mean to be Black at UPENN? If you're a Black guy living in, if you're a Black person living in the Quad it means compromise… I think Black people who are in that scene, who live in the Quad, have to compromise a little bit of their identity in order to fit in…. they give up some of their Black identity to fit in … there's a very distinct difference in mannerisms between Black people who live in Du Bois … and the Black people who are here from the Quad. [For example], I say hi to them, they shake my hand fifteen different ways, they have an afro pick sticking out of their head, they're wearing baggy FUBU jeans and a sweatshirt. They're into Common, they're into Mos Def, lots of good hip-hop… And, you know, they use Black slang, you know? The [Black] kids I meet in the Quad, they dress fairly conservatively and they're not listening to hip-hop … it's not so much part of their identity. They speak like White people, they act like White people… I mean it's basically just if their skin wasn't dark, you'd think they were White, you know?

George's perception of ‘most’ Black students at the University of Pennsylvania is inaccurate. Although our data are not representative of the entire Black University of Pennsylvania student population, the Black students in our sample have had sustained interracial contact throughout their lives. Over two-thirds of Black respondents attended high schools that were predominately White and lived in integrated neighborhoods. The average Black student resided in an area that was nearly 40% White and about 50% Black with smaller Latino and Asian percentages (see the bottom panel of Table 1). Moreover, the findings here suggest that Whites believe the onus of promoting integration and diversity on campus is on Black students, rather than perceiving it as a two-way process. White students repeatedly fault the Du Bois House for making the university a less ‘diverse’ place, but are oblivious to the existence and overabundance of White spaces that they've created and maintained for themselves.

To this point, we have detailed Black students metastereotypes and the degree to which they are consistent with White students' stereotypes of Blacks, both in general and at college. In the final portion of our analysis, we move beyond metastereotypes and examine Black students' perceptions of themselves and their place at the University of Pennsylvania, in an effort to further understand how race impacts Black student's collegiate experience. Whether and how Black students internalize Whites' negative racial stereotypes of Blacks further reveals how race rules their everyday lives (Dyson 1996). As members of an historically oppressed group, Blacks in the contemporary U.S. are not immune to the pervasive images of Black inferiority. Despite their best efforts, many Blacks internalize these negative societal images while striving to succeed in a society that consistently devalues both their individual and their collective worth. Thus, Du Bois' metaphorical ‘veil’ providing Blacks with ‘second sight’ is also a ‘curse,’ forcing Blacks to contemplate their place in society—always through the eyes of Whites. A vast literature deals explicitly with the psychological scars inflicted on the Black psyche by racism, including ‘the mark of the oppressor’ (Du Bois 1970, 1989, 1995; Fanon 1963, 1967; Freire 1993; Kardiner and Ovesey, 1951).

In general, the Black students in our study do not think of themselves in stereotypic terms. Tabulations of the extent to which Black respondents have internalized negative stereotypes of Blacks, summarized in Table 5, reveals that over 40% (thirteen of of twenty-nine) of Black respondents believe that they are both financially better off than Whites and well-versed in the ways of Whites. As students attending an Ivy League institution, they are worlds away from the welfare dependent, criminally-prone Blacks that Whites hold in disdain—they have “beaten the odds.” Several Black students were surprised by the number of same-race peers from affluent backgrounds. As Matt notes:

The Internalization of Stereotypes: Black Stereotypes about Black University of Pennsylvania Students

I had never been exposed to bourgie Black people—rich Black people, I guess. Bourgie… Because I mean, I knew they existed, I just never met them. You know?

Julie was also surprised by Black students' affluence at the University of Pennsylvania, and sees herself as less affluent than her same-race friends.

A lot of my friends … like their parents can afford to pay their tuition, you know… They may have a little financial aid but they don't get as much as like I get, you know?

Despite having money, eighteen of the twenty-nine Black respondents believe that being Black puts them at a disadvantage at the University of Pennsylvania. They believe that they have to study more and work harder to overcome the stigma associated with being Black. And, unlike many of their White peers they do not have the ‘connections' to corporate America or the ‘legacy’ status many White students have. Responsibly ‘representing the race’ is critically important: Black students feel constant pressure to dispel Whites’ beliefs about Black inferiority and are always striving to present a positive image.

To the extent that the Blacks in our sample do internalize negative stereotypes, it is more likely to be a problem for the men than it is for the women we studied. The Black men we interviewed spoke at length about how stereotypic notions of Black masculinity make them ‘exceptional,’ since Black men in particular are not expected to make it into the elite echelons of White society. Joe explains his feelings about being a Black man at the University of Pennsylvania. At the time of his interview, he had a 3.7 grade point average and had just received acceptance letters from several top-tier medical schools.

… I feel like I have to be, I don't know, just feel like—especially 'cause there's not that many Black people here, I just feel like I have to be a leader … like, ‘okay, there's a Black man, doing his thing’… I guess that's why I over extend myself like everybody, maybe because I'm, supposedly doing well, and like everybody wants me to… I basically contradict the entire stereotype of a Black male… I am intelligent, motivated, I got to an Ivy League school, I going to go medical school at an Ivy League school… I think I can in some way serve as a blueprint for other Black people to propel themselves in society. I can show people what I have done and they can use the same tactics or strategies to do something good with their lives.

Mark is also cognizant that his presence as a Black male student at the University of Pennsylvania debunks societal stereotypes of Black men in America, and believes that the lack of interracial contact fosters White racism on campus.