An enormous amount of health information is available via the Internet. This information is accessed predominantly by the public, by prospective patients, and by healthcare professionals.Reference Higgins, Sixsmith, Barry and Domegan 1 – Reference Prendiville, Saunders and Fitzsimons 3 Thus, communication initiatives in infection prevention and control (IPC) should use the most effective strategies for the promotion, protection, and maintenance of health.Reference Higgins, Sixsmith, Barry and Domegan 1 Researchers and clinicians who work in this area need to gain new knowledge while providing and conveying meaningful information to the public, to patients, and to the media. The media are important messengers of public information and are influential in risk perceptions and responses.Reference Burnett, Johnston, Corlett and Kearney 4 Understanding the differences between articles published in scholarly work (eg, peer-reviewed journals) and those published by the media may help researchers bridge the gap between them.

Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs provide crucial advocacy platforms for speaking out about various healthcare issues and concerns. In contrast, peer-reviewed journals are not designed to facilitate discursive commentary outside a specialized circle of readers. Social media outlets are also able to keep track of trending developments in the medical field and to share technical aspects of medicine on a more general level. 5 Amid these broad platforms, IPC, particularly healthcare-associated infections, have taken a prominent position in the mainstream media, creating a driving force for change.Reference Boyce, Murray and Holmes 6

With such a variety of mechanisms available to obtain and communicate IPC information, it is important to understand current publication trends. We undertook both a scoping review to identify trending IPC topics from national news websites, newspapers, and the grey literature and a narrative review of leading IPC journals. The results of the scoping review were subsequently compared with results from the peer-reviewed literature review.

METHODS

Scoping Review

To identify trending topics in the news and in the grey literature (ie, non-news websites), a scoping review was undertaken. This approach helps to establish the existing evidence base, particularly when a narrative approach is difficult.

Eligibility criteria and information sources

To identify themes from non–peer-reviewed literature, publications from newspapers, news websites, and IPC-related websites were included in our review. We selected popular news websites and newspapers from the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, based on the highest circulation numbers (Table 1). 7 – 11 For each newspaper and news website, the following key words were used to search for articles published in the 2015 calendar year: hospital infection, healthcare-associated infection, superbugs, and infection control. All articles retrieved from these searches were carefully examined for their relevance to the prevention or control of infection in healthcare settings; unrelated publications were excluded. When a subscription was required for such searches, it was purchased.

TABLE 1 Publication Included in the Scoping Review

NOTE. BBC, British Broadcasting Corporation; CNN, Cable News Network.

Several infection control websites were included in the review: Infection Control Today (http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com), Reflections in Infection Prevention and Control (http://reflectionsipc.com), and Controversies in Hospital Infection Prevention (http://haicontroversies.blogspot.com.au). These the infection control blogs were selected by the research team because team members were familiar with them. All blogs from the Reflections in Infection Prevention and Control and Controversies in Hospital Infection Prevention websites were included, and publications listed as articles on the Infection Control Today website were also included. All articles, blogs, and commentaries published in the 2015 calendar were carefully examined for their relevance to the IPC in healthcare settings; unrelated publications were excluded.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from IPC and news websites: title and date of publication, IPC topic, website, any reference to peer-reviewed article or research. The same data were extracted from newspapers. For IPC websites, data regarding the number of replies, likes, or shares related to a post were captured.

Narrative Review

Eligibility criteria and information sources

We conducted a narrative review of all papers including editorials, research papers, and correspondence published in 4 IPC journals during 2015. Papers with a listed author were included if they were listed in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL). Several IPC journals were included in this review: the American Journal of Infection Control, the Journal of Hospital Infection, Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, and Healthcare Infection (now called Infection, Disease and Health). These 4 IPC journals had the highest values (in 2014) of source of normalized impact per paper (ie, SNIP rating); they were all powered by Scopus; and they were all broadly linked with the geographical regions of newspapers and news websites included in the scoping review.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from all articles: publication date, journal, article name, abstract, volume, issue, page number, and authors.

Data Analysis

Frequencies of word use in titles were analyzed using NVivo version 11 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Stemmed words were considered the same term, for example, ‘talk’ and ‘talking.’ Weighted percentages were calculated for word frequencies; words with <3 letters were excluded. Comparisons by country and type of publication were made. The results were visually displayed using word clouds. Descriptive statistics to analyze the number of publications, replies, likes, and shares were undertaken using SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Newspapers, news websites, blogs, and academic journals do not target the same audiences. However, the presentation of findings in a consistent manner facilitates an overview of trending IPC topics and how different topics resonate on different communication platforms.

RESULTS

Scoping Review

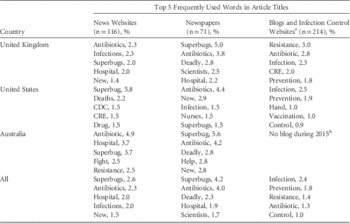

During the 12-month study period, the 6 news websites included in this study published a total of 116 articles. Moreover, 71 articles had been published in the selected newspapers, and we identified 214 publications from IPC websites. Article titles from news websites, newspapers, and IPC websites were analyzed for web frequency and were compared according to country of publication (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Commonly Used Words in Article Titles on News Websites, Papers, and Blogs

a Blogs included articles from Infection Control Today (ICT) and Controversies in Hospital Infection Prevention (CIHIP) websites. In CIHIP, the words most commonly used were vaccination, stewardship, cost, infection, and influenza. In ICT, the words most commonly used were infection, prevention, compliance, hand, and hygiene.

b Infection Digest commenced publication in 2016.

One of the metrics provided on the Infection Control Today website is how many times an article has been recommended (referred to) another person. The 2 most recommended articles published on the Infection Control Today website were articles titled “Your role in infection control” and “Hand hygiene compliance monitoring provides benefits and challenges,” with 111 and 105 recommendations, respectively. These 2 articles also contained the most references among articles on this website. The blog with the most comments on the Controversies in Hospital Infection Prevention website was titled “Root causes underlying the emergence of influenza vaccine mandates.” The blog “Reflections from the front line: why doctors don’t listen to the ‘impending doom’ of antibiotic resistance” received the most comments on the Reflections on Infection Prevention and Control website.

Of the 116 articles published on online news websites, 66 articles (57%) made no reference to a specific study or piece of research. Overall, 16 articles (14%) did refer to a study but made no mention of where the study had been conducted and did not provide any reference for identification. Of the 71 newspaper articles identified, 22 articles (19%) made no reference to a specific study or piece of research. In total, 21 articles (27%) did refer to a study, but they did not provide any reference for location or identification.

Narrative Review

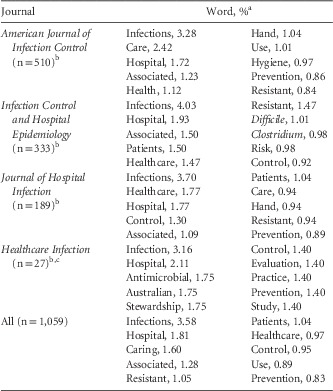

Overall, 1,059 articles were initially identified; 98 articles did not have a listed author so were excluded. Therefore, 961 were included in the review. Most articles (48.2%) were published in the American Journal of Infection Control, followed by Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (31.4%), Journal of Hospital Infection (17.8%), and Healthcare Infection (2.6%) (now called Infection, Disease, and Health). These proportions reflect the total number of papers published in these journals during the year. The titles of these papers were reviewed, and word frequencies were calculated. These results are presented in Figure 1 and Table 3.

FIGURE 1 Combined word frequencies in all journals. Note: Infection, 3.6%; hospital, 1.8%; care, 1.6%; associated, 1.3%; resistant, 1.0%.

TABLE 3 Commonly Used Words in Article Titles of Infection Control Journals

a Percentages are weighted.

b n refers to the number of articles included in the narrative review for each journal.

c Healthcare Infection is now called Infection, Disease, and Health.

DISCUSSION

The terms ‘superbug’ and ‘antibiotics’ were most commonly used in the titles of news websites and newspapers, and the terms ‘infection’ and ‘prevention’ were mostly commonly used in IPC websites or blogs. The latter may reflect original authorship because articles on IPC websites/blogs tend to be written by professionals in IPC. Journalists and editors that may or may not have any health or IPC knowledge are primarily responsible for writing or commissioning articles in newspapers and on news websites. Emotive terms such as ‘superbugs’ and ‘deadly’ were used more widely on these platforms.

Although the term ‘superbug’ has no specific definition in scholarly literature, it has been used since 1985 in the media. Why? The term ‘super’ means above and beyond; perhaps coupled with ‘bugs’ (more accurately used in entomology), this term provides a sense of uniqueness or indestructibility.Reference Washer and Joffe 12 The increased use of apocalyptic discourse related to antibiotic resistance and ‘superbugs’ contrasts with catastrophe discourse regarding global warming, which is undergoing reflexive criticism.Reference Nerlich and James 13 As with global warming, discussing healthcare-associated infections in terms of ‘superbugs’ and ‘deadly,’ terms that have been associated with apocalypse and war, has both advantages and disadvantages.Reference Nerlich and James 13

Naturally, these advantages and disadvantages depend on the perspective of the author and audience and/or the potential implications of using these terms. They could be used in a positive manner to attract attention, (eg, to justify resources or research funding) or in a negative manner (eg, to hold someone accountable, eg, politicians or a national ruling body). We explored several similarities between the use of certain terms (eg, superbugs on news websites and in newspapers from different countries) in the scoping review. The term ‘superbugs’ was less commonly used in American newspapers, and the term ‘deadly’ was rarely used. In contrast, these terms were most commonly used by news websites in the United States. Perhaps the use of sensationalist terms can in part be attributed to the ‘click bait’ phenomenon, a forward-referring technique for online articles.Reference Blom and Hansen 14

The IPC journals reviewed in this study had used similar words in their titles, but some variations were noted. Articles in the American Journal of Infection Control frequently used the word ‘care,’ whereas in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the word ‘patients’ was prominent. The latter may reflect the stronger infectious disease focus of this journal. The word ‘control’ was frequently used in articles from the Journal of Hospital Infection. Arguably, this reflects the focus of this journal, eg, infection, prevention, and control. Articles from the Australian-based publication Healthcare Infection used the word ‘stewardship’ more frequently than other journals, although the small number of articles from this journal made interpretation more difficult.

We identified a clear gap between words commonly used in the titles of articles in the media (newspapers and news websites) and those used in scholarly literature. However, blogs and IPC websites appeared to bridge this gap. Although potentially emotive terms such as ‘superbug’ were not commonly used in blogs, terms such as ‘antibiotics’ and ‘resistance’ were prominent. Blogs are used to engage readers, share knowledge, reflect experiences, and encourage debate. They offer unique and powerful information features.Reference Boulos, Maramba and Wheeler 15 Blogs have been considered a vehicle of democracy because they foster decentralized citizen control as opposed to hierarchical, elite control.Reference Scoble and Israel 16 – Reference Meraz 18 Paradoxically, however, blogs often lack scientific rigor due lack of peer review and/or the promotion of a personal agenda.

Although there is a demonstrable gap between language used in scholarly journals and mainstream media, trends in public access to IPC research are encouraging. At a time when universities face a so-called ‘crisis of relevance,’Reference Hoffman 19 the increasing use of web-based platforms to disseminate scientific research indicates that active links exist between authors and the wider public.21 As universities become increasingly market driven, communication initiatives in the service of public health and IPC offer an emerging model of media integration that could be replicated in other disciplines.21

In conclusion, scholarly journals have a vital gatekeeping role in framing and disseminating health information in a way that is at least ostensibly free from ideological and individual bias. Journals are also supposed to be less affected by political and commercial pressures than mainstream media outlets, which are often driven by competing agendas to attract an audience by framing health news to draw strong emotive responses.Reference Nabi and Prestin 20 From our reviews, we conclude that integration of a range of mediums is necessary to better serve the public interest. Whether the role is one of advocacy, general health information dissemination, or warnings of imminent risk, health researchers have access to multiple forums with different strengths through which to influence public risk perceptions and responses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support: This work was supported by a scholarship provided by Avondale College of Higher Education.

Potential conflicts of interest: SJD has an editorial affiliation with the Journal of Hospital Infection and Infection Disease and Health (formerly Healthcare Infection). BGM has an editorial affiliation with Infection Disease and Health (formerly Healthcare Infection). All other authors have no conflicts to declare.