Introduction

Naming is a linguistic universal. Every known human society distinguishes and individuates its members by their names. In the context of Africa and beyond, names are not just ordinary labels for the identification of their bearers; they mirror the culture, tradition and worldview of the people. Essien (Reference Essien1986: 5) argues that ‘naming is not an arbitrary affair, it is at once a mental, an emotional, a linguistic and a cultural matter’. It is widely believed that names and naming can influence the personality development and behaviour of their bearers. This claim justifies Camden's (Reference Camden and Dunn1984: 43) admonition that ‘names should be chosen with good and gracious significations to inspire the bearer to good action’. This implies that people are assumed to live according to the message contained in their names. Significantly, names also embed deep cultural insights that reflect their bearers’ social lives, philosophy, religion, emotions and worldview. African names, for instance, are important cultural and symbolic resources that reflect the peculiarities of the African people, and capture their beliefs, values, identity and personality.

The precolonial and colonial eras of Nigeria witnessed increasing contact between English and Nigerian languages, mostly due to the activities of many Christian evangelical missions and the impact of British colonial rule, although indigenous Nigerian names were not immune to this contact phenomenon being that they are lexical items that are part of a language (Mensah, Reference Mensah2015a). Missionaries to Nigeria changed many indigenous names during baptism. Katoke (Reference Katoke1984: 7) reports that ‘the most important changes for the African Christians converts among other things, was an acceptance of a European name’. Beyond getting rid of African traditional values and religious concepts, the missionaries also provided alternative forms of some African names ‘for ease of pronunciation’ (Ukpong, Reference Ukpong2007; Mensah & Rowan, Reference Mensah and Rowan2019). On the part of the colonial administrators, there was deliberate renaming of some African families where indigenous African names were replaced with European names. Nair (Reference Nair1972) maintains that in Old Calabar, Southeastern Nigeria, names like Ironbar, Yellow Duke, King Duke, Ephraim and Fuller became popular family names among the Efik as a result of the colonial conquest. However, it is common knowledge that some indigenous people of Nigeria deliberately invented mechanisms to Englishise their names to make connections with modernity and affiliate with a style and prestige that define Englishness. This follows the increasing influence of English in the sociolinguistic landscape of Nigeria which is a result not only of language contact and shift but also cultural assimilation and diffusion.

The literature on onomastics has been replete with people from several countries and cultures of the world adopting English names at the expense of their ethnic personal names for various reasons, given the domineering influence of English in driving processes like globalisation, global media, education and migration. Lujan–Garcia (Reference Lujan–Garcia2015) identifies high fashion and social prestige as the main values that influence the adoption of English first names by Spanish youth. This may be the effect of environmental pressure and satisfaction with one's experiences with English speakers. Diao (Reference Diao2014) argues that transnational Chinese students in the United States prefer English names to negotiate identity options and membership in various communities of practice. English name adoptees in this context also believe that such practices are trendy, and make them appear English, educated and sophisticated. For Kim (Reference Kim2019), the choice of English names by Chinese TESL students in the US and UK is to create an English identity, and take control of their language learning experience and of the new environment in which they have found themselves. Other motivations include satisfying occupational requirements (Huang & Ke, Reference Huang and Ke2016); the inability of Westerners to pronounce indigenous personal names (Heffernan, Reference Heffernan2010), and as a strategy for identity management (Cheang, Reference Cheang2008), which demonstrates that people the world over choose English names as a way of confronting new realities, and to integrate into a global culture.

Thonus’ (Reference Thonus1991) study of the influence of English on female names in Brazil in the period 1967–1987 reveals a considerable impact of English in terms of orthographic and phonological patterns on female naming in spite of the small influence of English on the Portuguese language. This naming trend has been attributed to an increase in fashion, a decline in tradition and a process of integration into global culture by Brazilian women. In a related study, Chen (Reference Chen2015) identifies homophonisation as a common phenomenon in the choices and patterns of English names adopted by Taiwanese students in the United States. While male students’ names are likely to end with consonants, female names are more likely to end with vowels, and monosyllabic English names are common among both genders. The study concludes that a preference for English names is socially motivated by a sense of English identity preservation, and as a mark of cultural assimilation. The adoption of English names makes, therefore, a significant contribution to the dynamics of an expanding sociocultural system. The present study is not concerned directly with the adoption of English names but with the ‘Englishisation’ (Kachru, Reference Kachru1994: 135) of Nigerian names. The term Englishisation in the context of this study reflects the impact of English on indigenous Nigerian names and culture.

In this article, the Englishisation of some indigenous personal names in Nigeria is explored using case studies from the Efik and Ibibio onomastic traditions. The Englishisation of names under three main threads is discussed: Anglicisation, hybridisation and tonal alteration. The study aims to show that beyond the effects of Christianity and colonialism, the Englishisation of personal names in Nigeria is a tacit acceptance of English for a global identity.

Names and naming culture in Nigeria

Personal naming practices are a significant aspect of different cultures around the world, and naming practices, traditions and patterns vary across culture. Names are symbolic resources that provide a lens for accessing a people's view on life, the world and humanity, and are sources of ethnic, religious and linguistic identities. Personal names may also provide a subtle reference to a people's history and traditions. Fakuade, Friday–Otun and Adeosun (Reference Fakuade, Friday–Otun and Adeosun2019: 260) use the proverb, Orúkọ ọmọ nín ro ọmọ ‘A child's name determines what he/she becomes or does’ to emphasise the importance of naming among the Yoruba people of Southwestern Nigeria. A similar proverb is also found among the Igbo people of Southeastern Nigeria, Éjí áhá ábàgbù mmádù ‘One's fate can be ruined by the kind of name given to the person at birth’ (Ebeogu, Reference Ebeogu1993: 133). These proverbs represent a cognitive-reflective view of naming on their bearers’ lives. Names are central in defining the concepts of self, personhood and future-life course of their bearers. In this case, names do not only denote identity and individuality; they also influence an individual's life history and future directions. They explore the diversity of life pathways and are related to social roles across life domains (Mensah & Iloh, Reference Mensah and Ilohforthcoming). In many cultural contexts in Nigeria, personal names provide the link to family history and connections. They are passed down from one generation to another, thus symbolising continuity within the family and more broadly within the society.

Among the Ibibio people of Nigeria, personal names provides a window into their cosmology, social histories and worldviews. Identity construction among the Ibibio, therefore, implicates their culture, history and language (Boluwaduro, Reference Boluwaduro2019). Naming is an important tool for the transmission of cultural heritage. Mensah & Offong (Reference Mensah and Offong2013) remark that among the Ibibio, naming is a mark of identity, solidarity and social cohesion. All cultural activities, traditional ecological knowledge system and beliefs have a representation in personal names. For instance, children are named after geographical or meteorological features such as rivers, swamps, mountains, and weather, or important spiritual icons such as Supreme God, deities, witchcraft, and divinities. They are also named after the traditional days of the week, circumstances of birth, places of birth (e.g. market, farm, stream, road), family occupations, and communal conflicts. The Efik people use personal names to trace children genealogically to their founding ancestors (Mensah, Reference Mensah2010). Children are equally named based on the day or time of the day they were born. Efik names can also be bestowed to celebrate heroic deeds of the name-givers at some points in history. In this culture, children are often named after deceased or living members of the extended family as a mark of honour, and to strengthen family bond through generations.

Naming among the Yoruba is significantly a cultural affair. Akinnaso (Reference Akinnaso1980) argues that Yoruba names have semantic contents and reflect the real-world knowledge of the Yoruba people. In other words, a name must be meaningful to both the giver and the bearer. Hence Yoruba names are not given arbitrarily but are carefully selected to ‘achieve personal strategic aims’ (Herzfeld, Reference Herzfeld1982: 288), and to mould the life of the bearer and locate him or her within a particular socio-cultural space. Balogun and Fasanu (Reference Balogun and Fasanu2019) observe that rites associated with naming among the Yoruba underscore the people's belief in birth, life, and living, as well as the totality of their existence. Yoruba names have been categorised as an essential means of communication (Akinola Reference Akinola2014), grammatical constructs (Oduyoye, Reference Oduyoye1982; Ajiboye, Reference Ajiboye2011; Okewande, Reference Okewande2015), sources of gender differentiation (Orie, Reference Orie2002), and a representation of many belief systems (Fakuade et al. Reference Fakuade, Friday–Otun and Adeosun2019). Among the Igbo, names are products of the linguistic and cultural reservoir, with immense social, historical and philosophical significance. Ubahakwe (Reference Ubahakwe1981) demonstrates how Igbo names can provide insights into the structure of the Igbo language. Names are comprised of words, phrases, clauses and sentences, and their construction is governed by the grammar of the Igbo language. Other studies have explored Igbo names from the perspectives of gender (Ogbulogo, Reference Ogbulogo1999; Onukawa, Reference Onukawa2011), cultural semantics/pragmatics (Onumajuru, Reference Onumajuru2016; Iloh, Reference Iloh2021), sociology (Mbabuike, Reference Mbabuike1996) and power relations (Obododinma, Reference Obododimma2009; Solomon–Etefia & Ideh, Reference Solomon–Etefia and Ideh2019). In all, it has been demonstrated that names are essential components of social and cultural systems that permeate every facet of human experience and life domains.

A significant aspect of naming in Nigeria is the use of names to reflect spiritual beliefs. A belief in reincarnation is dominant across culture, and children who are believed to have reincarnated are often bestowed with death-prevention names to ensure their survival. This phenomenon has been studied among the Ibibio (Mensah, Reference Mensah2015b), Mbube (Akung & Abang, Reference Akung and Abang2019), Tiv (Mensah et al., Reference Mensah and Rowan2019), Yoruba (Óyètádé, Reference Óyètádé, Lawal, Sadiku and Dopamu2004) and Igbo (Aji & Ellsworth Reference Aji and Ellsworth1992), among other traditions. Such names are not ordinary labels but are ritualised representations that are used to hide the identity of name-bearers from underworld forces. This is the subtle psychology that enables name-bearers to live (Mensah, Reference Mensah2015b). Nigerian names are also bestowed to mirror the religious identity of name-givers. Adherents of Christianity, Islam and African Traditional Religion select names for their children based on their beliefs and faith. Mensah (Reference Mensah2020) maintains that such religion-based names permit adherents to project a healthy self-image and create psychological unity as a result of the sense of protection they are believed to confer. In the context of this review, I agree with Palsson (Reference Palsson2014: 623) that ‘practices of naming are firmly rooted in epistemologies of belonging, relatedness and becoming human.’ Contemporary perspective on naming practices among Nigerians reveal the effect of contact with the English language which has overriding consequences on indigenous names and cultures. This justifies the claim by De Pina–Cabral (Reference De Pina–Cabral1994: 131) that ‘as political, economic and cultural conditions change, so does each person positioning towards ethnic belonging, both in terms of socialisation and in terms of subsequent strategic aims’. In this study, I aim to demonstrate the dominance of English as a powerful social force that has influenced modern patterns and practices of naming in some cultural contexts in Nigeria.

English in the Nigerian context

The English language is increasingly advancing in status as a global language and medium of international communication. It is the most widely spread language in the world, and has been adopted as an official language in many countries across five continents (Xue & Zuo, Reference Xue and Zuo2013). The emergence of information and communication technology coupled with Western economic influence, political strength, scientific inventions and innovations has increasingly consolidated the dominance of English in the ‘outer circle’ (Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985, Reference Kachru1992), where English has important functional utility in diverse cultural settings. Larson (Reference Larson1990) argues that science and technology are new areas and in rapid expansion phase, and most developments receive English names. In Nigeria, English has an administrative status, and is widely studied as a second language. The English language in Nigeria has been localised to what is popularly referred to as Nigerian English (NE). It is a variety of English that has its own sub-varieties such as Igbo English, Yoruba English, Efik English and Ibibio English among others. It is a dominant language, and Bamgbose (Reference Bamgbose and Fishman1996: 371) predicts that NE's ‘future appears to be more as a component of a bilingual resource.’ NE has received enormous attention in the literature of World Englishes among scholars in Nigeria and beyond (Gut & Fuchs, Reference Gut and Fuchs2013; Jowitt, Reference Jowitt2019; Unuabonah & Daniel, Reference Unuabonah and Daniel2020).

There is an upsurge in the use and propagation of English following many decades of British colonial rule and missionary evangelical activities during the colonial and pre-colonial eras. Northrup (Reference Northrup2013: 75) argues that ‘British colonies chose English as a necessary and powerful tool for uniting their disparate population and modernising their societies.’ From Nigeria's independence in 1960, English became Nigeria's official language, not only to facilitate cross-cultural communication, but also to unite the densely linguistically heterogeneous population of Nigerians. Jowitt (Reference Jowitt1991) records that Standard English was entrenched in Nigeria by the colonial administrators who came from the upper and middle strata of British society. They ensured that Standard British English – combined with Received Pronunciation (RP), given its prominence and prestige – was the norm in schools and the civil service for Nigerian learners. To date, English is the predominant language within government circles, and in other critical domains like education, media and international communication.

English is a compulsory subject at all levels of education up to university level. It is a key requirement for all entrants, promotional and matriculation examinations. The country's National Policy on Education (NPE) gives English a pride of place in the intellectual development of Nigerian children and learners. The language-in-education policy specifically states that:

The medium of instruction in the primary school shall be the language of the environment for the first three years. During this period, English shall be taught as a subject. From the fourth year, English shall progressively be used as a medium of instruction and the language of immediate environment and French shall be taught as subjects (NPE 2004: 16).

This provision highlights the importance accorded to English in the educational space in Nigeria. English is also a requirement for employment. It has also dominated the mediascape in Nigeria, both electronic and print, given its expressive capacity and market potential. In social media, the use of English has displaced most of Nigeria's indigenous languages. This is a result of its widespread acceptance by the younger generations who are the largest engagers of online communication. The flexibility and adaptability of English has promoted its value as a language of digital communication. In this regard, Taiwo (Reference Taiwo2009: 7) maintains that English ‘remains the only relevant language that allows Nigerians to participate in the contemporary social process within and outside the country.’

Language is not just a tool for communication, it is a carrier of cultural emblems and identity. In this regard, the global spread of English is impacting negatively on Nigerian languages and cultures. An essential consequence of this influence can be found in reverse transfers including calquing, borrowing, transliteration, code-mixing and code-switching. There is no Nigerian language that is not affected by these phenomena. Commenting on the effect of code-mixing on indigenous Nigerian languages, Ahukanna (Reference Ahukanna and Emenanjo1990: 185) maintains that there is no conscious and vigorous effort in language use to stem the tide of unidirectional code-mixing which favours English to the detriment of the mother tongue; a linguistic situation may be reached which may result either in the pidginisation of the mother tongue or its complete elimination by the dominant English language. Mensah (Reference Mensah2010), however, argues that such phenomena can help to increase the vocabulary of the indigenous language to enable it to develop to meet the demands placed upon it as a means of communication. The hegemony of English in Nigeria has also helped to reinforce the attitudes and perceptions that speakers of indigenous languages have towards their own languages. Some evaluate their language as inferior and incapable of expressing certain concepts, values and thoughts. Some believe that competence in their local languages does not guarantee their functioning as international citizens (Canagarajah, Kafle & Matsumoto, Reference Canagarajah, Kafle, Matsumoto and Yiakoumetti2012: 82). In this context, some speakers of Nigerian languages have integrated themselves into a global world that is modern through their knowledge of English at the expense of their mother tongue which is basically identified with local tribal traditions. The result may be the endangerment or subsequent extinction of these native languages.

The cultural invasion of Nigerian languages by global English may be seen in some quarters as a continuation of a colonialisation policy by relatively civilised means (Xue & Zuo Reference Xue and Zuo2013), and the effect on Nigerian languages is overwhelmingly leading to locally developed standards of use which have been institutionalised. In certain situations, English has been localised and simplified to Nigerian Pidgin. Nigerian Pidgin flourishes as a medium of interethnic communication, especially among less educated people in large cities with many non-indigenous residents, and states with people from many ethnic nationalities (Jowitt, Reference Jowitt1991). The nativisation of English to accommodate other non-users of English aims to give a greater sense of belonging to speakers of non-Standard English and establish it as a universal language. This study demonstrates the influence of English on one aspect of Nigerian culture, personal names, and how this naming practice is reinforcing a global identity among name bearers.

Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative ethnographic approach towards data collection and analysis. Data for the study was collected during a six-month ethnographic fieldwork in Calabar and Uyo where the Efik and Ibibio languages are predominantly spoken respectively. Efik and Ibibio are mutually intelligible languages of the Niger–Congo family. Efik has a population of 500,000 first-language speakers and 2 million second-language speakers, and Ibibio has 3.7 million speakers (Simons & Fennig, Reference Simons and Fennig2017). The Efik people are found in Cross River State, while the Ibibio live in Akwa Ibom State, both in the southeastern geographical area in Nigeria. The Efik and Ibibio people share similar cultural values and beliefs such as chieftaincy institutions, marriage and funeral systems. Their naming practices, however vary considerably. They are distinct groups of people who belong to the same South South Region geopolitical zone. 20 people were selected as participants in this study: five men and five women each in Calabar and Uyo respectively. They were all bearers or givers of Englishised names. This was an important criterion for selection in the purposive sampling in addition to the willingness of participants to be involved in the research. Socio-demographic data of participants such as age, gender, education, occupation, marital status and religion were also documented. Some of these variables were useful considerations in the bestowal of Englishised names. Participants’ ages ranged from 18–79 years. Five participants (25%) were graduates from institutions of higher learning, and another five (25%) were secondary-school leavers. Another five participants (25%) did not attend school beyond the primary level, and five more (25%) claimed to be educated informally. Only six participants (30%) had paid employment. Two were unemployed, and the remaining 12 participants (60%) were either artisans or engaged in natural resource-occupations such as farming, fishing and mining. 14 participants (70%) were married and six (30%) were single. 17 participants (85%) were Christians and three (15%) claimed to have agnostic religious views with no specific identity.

Three ethnographic methods were used in the data collection orientation. Participant observations, semi-structured interviews and small talk (metalinguistic conversations). Participant observations afforded the researcher a first-hand opportunity for interaction with name-bearers and givers over an extensive period of time. There were encounters with name-bearers and givers in their homes, town halls, playgrounds and market squares. Through this approach the researcher studied participants in greater detail to understand how they make meaning of their Anglicised names. Semi-structured interviews offered participants the opportunity to share their perspectives, reactions and perceptions of their names. Participants were asked questions on the sources of their names, meanings, and linguistic processes involved in their construction. Small talk enabled the researcher to gain other contextual information that was hidden in the previous modes of inquiry. Questions were generated on the spur of the moment concerning the choice of names and their subjective interpretations. The researcher sought to understand the mechanism of name formation and the preference for Englishised names. Data was also sourced from textual material such as Ukpong (Reference Ukpong2007), school registers in the study areas, and internet resources, particularly from Facebook profile names.

Ninety-three Englishised names were collected in the field with an audio recorder and field notes which also preserved transcripts of interviews and recordings. Data was coded into relevant thematic frames, checked for accuracy and transcribed. The descriptive method was used to analyse the data. This approach enabled the research to interpret the main features of the data and to offer in-depth explanation based on the perspectives and experiences of participants.

Data analysis and discussion

The Englishisation of Nigeria's indigenous names are categorised and discussed under three main threads: anglicisation, hybridisation and tonal alteration. Each of these processes are analysed in detail as follows.

Anglicisation

Anglicisation is a cultural and linguistic assimilation process (Veltman, Reference Veltman1983), and it entails the diffusion of English words (or names) through borrowing and adaptation into other languages.

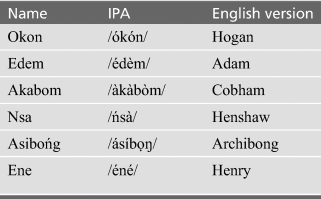

There are many strategies of anglicising Efik and Ibibio names. The most pervasive is the substitution of indigenous names with English names. This process provides ‘equivalent’ renditions of indigenous names in English, as we can see in the Efik data in Table 1:

Table 1: Name substitution as an anglicisation process

Based on the findings, this name changing technique was introduced by the early missionaries in Old Calabar as a result of ‘mispronunciation of the original names’ (Ukpong, Reference Ukpong2007: 277). There is no systematic linguistic principle that is involved in the substitution of these names. This is not to say that the process is entirely arbitrary. There is close correspondence in the pitch level of the set of names and phonetic resemblance between the original names and their English counterparts. All the original names begin with vowels (as a matter of rules all nouns [including names] in Efik begin with vowels as a phonotactic requirement) while some of the English equivalents start with consonants. There is no semantic relationship between the set of names. The set of names can be used concurrently but as Essien (Reference Essien, Wolf and Gersler2000: 120) rightly points out, ‘the anglicised or corrupted forms are held in much higher esteem than the local original forms.’ This evidence reveals that the social preference for English names reflects the desirable qualities name-givers associate with such names. A participant (Hogan: Male 40) believes his anglicised names in Table 1 bestow certain social privileges given their popularity and universality, and integrate him into the English world.

Other crucial anglicisation strategies based on the data involve different forms of spelling modifications. In other words, the correspondence between the sound and the symbols it represents is somehow indirect. There are many instantiations of spelling modifications in anglicised names, as can be seen in Tables 2 and 3:

Table 2: Names that end with velarised nasal

Table 3: Names that attract a double letter after the initial sound (Efik and Ibibio)

In Table 2, the original Efik names are written phonemically while their anglicised versions are represented orthographically based on the English alphabetic system of writing. A participant (Ekong: Male 35) stated that he prefers the English version of his name because it is easier to read, type and write than its ‘local’ version. This is made possible because the velar nasal sound in English /ŋ/ is always realised as (ng) in writing. This evidence highlights the facts that the English versions do not carry tonal and diacritical marks hence; they are easy to spell, write and remember. He also said that the use of diacritic in writing his ethnic name usually poses problems for appropriate writing and pronunciation – a challenge that the anglicised spellings has remedied.

The data in Table 3 demonstrates the doubling of the intervocalic labio-dental sound /f/ in writing in the English version of the names. Participants were only able to explain this writing convention (which is a violation of the Efik orthographic principle) as a form of innovation. Most of the names also ended in velar nasal sound (ŋ) as in Table 2 thus, justifying the claim of the English version being preferred because it is easier to print, write, spell and read. Further examples of spelling modifications of names can be seen in Tables 4 and 5:

Table 4: Names that end with a redundant letter (h) (Efik)

Table 5: Names that end with a redundant letter (h) (Ibibio)

Tables 4 and 5 illustrate the derivation of Anglicised names by the addition of an extra letter /h/ at the end of the original name. The letter is redundant and does not represent any sound in the name. Williamson (Reference Williamson1984) observes that the use of the letter (h) in the orthography of Nigerian languages indicates that the preceding vowel is narrowed. This claim is not validated in some of the examples in which the letter (h) is proceeded by open vowels. Conversely, the use of this symbol does not have a principled systematic explanation other than being analysed as a stylistic convention. A participant (Amah: Female 48) explained that the addition of the extra letter has prevented her name from being localised. The majority of bearers of this category of names seem to prefer the anglicised versions in spite of its lengthening effect.

Other forms of the anglicisation process can also be found in our data corpus. This involves those that use the graphemes (-gha) and (-tt) as we can see in Tables 6 and 7 below:

Table 6: Anglicised names that end with (–gha) (Efik)

Table 7: Anglicised names that end with (–tt) (Ibibio)

The data in Table 6 demonstrates how the English version of names are formed by representing both the syllabic velar nasal sound (ŋ) and the uvular sound /ʁ/ as the symbols (-gha). Based on the findings, participants argue that the English version best represents the way their names are pronounced and written. One participant (Esuabangha: Male 38) maintained that his name was often mispronounced especially in the school context when he was using the original version which made him feel less valued and respected. This was what prompted him to adopt the English version which has been consistent in terms of spelling and pronunciation.

The data in Table 7 shows names which are anglicised by doubling the last letter of the original name. The extra (t) letter is redundant as it does not represent any sound in the original name. This is another case of stylistic convention which merely lengthens the name in other to give it the required English flavour. A participant also reported being more comfortable with the English version of her names because ‘it somehow hides the local meaning of such a name’ (Ibatt: Female 53). This evidence points to the fact that participants could react socio-cognitively towards the meaning of their names and the Anglicised version becomes a source of relief to such worries.

There are also instances of indigenous innovations in the Anglicisation process of indigenous Nigerian names as we can see in Tables 8 and 9 below:

Table 8: Anglicised names derived from indigenous innovations (Efik)

Table 9: Anglicised Names derived from indigenous Innovations (Ibibio)

The data in Table 8 and 9 illustrates anglicised names that are derived from indigenous innovations. There are many linguistic devices that are employed in the derivation of these names. These includes the use of double letters (e.g. Kooffreh, Essien), replacement of original sounds (e.g. Eskor, Bassey), deletion of original sound, and the introduction of unfamiliar sounds and letters (e.g. Damond, Etudor, Beka, Fion). Another adaptation is for example names such as Ninedays which is derived from phonetic resemblance with the original name but bears no semantic relationship with it. Participants spoke positively in favour of the English versions of the original names. For example, Damond (Male 39) remarked that the English equivalent is shorter and enhances his social personality. He believed that ‘it is a brilliantly creative name that is easy to remember and pronounced’. Other participants claim that the ‘English’ variant of their names made them stand out. Kooffreh (Male 54) maintained that the style and spelling of his name is more dignified, and in tune with the present time. The consensus was a preference for the English version over the indigenous names.

There is another trend of anglicisation of names which is quite pervasive among the younger population. This involves the adoption of English translated versions of their indigenous names. Examples of such names are illustrated in Table 10:

Table 10: Anglicised names which are semantic translations of indigenous names (Ibibio)

This trend is mainly promoted by the youthful population as a crucial aspect of their freedom of choice. A participant (Bright: Female 32) informed me that the translated names are used officially and among contemporaries. However, the older generation still refers to name-bearers with the original names especially in the rural setting. She described the trend as ‘a fashionable integration into English which is good for my social well-being.’ The use of translated forms of names is also perceived as a way of helping non-ethnic others to be able to pronounce and remember names.

Hybridisation

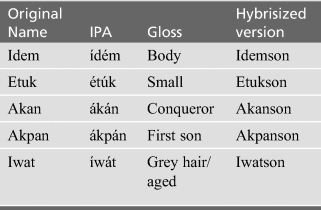

The process of hybridisation involves mixing of elements from two languages to derive a new variety of names. Patronymic English names uses the suffix ‘-son’ for conveying lineage. This suffix is also combined with certain Ibibio names and adapted as heredity family surnames. Examples of such names are demonstrated in Table 11:

Table 11: Hybridized names with ‘-son’

Participants agreed that these are names that are passed from father to son. For example, Idemson is a son of Idem, Etukson is a son of Etuk and so on. This shows that the use of the suffix ‘son’ has the same semantic import as it is used with English surnames. Beyond the masculine and hereditary attributes of this category of names, a participant (Ufford: Male 48) described it as ‘a stylish choice that fits the modern era’. Others believed that this class of names tells people about their ancestors and where they come from. Another participant (Ekanem: Male 50) said that ‘this set of names is fashionable and belongs to a class of its own’. Among the bearers of this category of names either as forenames or surnames, there was greater preference for the hybridised names than the original names.

A similar trend was also observed with the use of the suffix ‘-ton’ which may possibly be borrowed from English names ending in -ton such as Newton, Waxton, and Dalington, but unlike ‘son’, the meaning or function of the suffix ‘-ton’ was difficult to determine even by the name-bearers and givers, whereas in English its etymology is that it is toponymic as it refers to a farmstead or village. Examples of this category of names is finished in Table 12.

Table 12: Hybridized names with ‘-ton’

The set of names in Table 12 do not represent the concept of family names and surnames as the use of ‘-son’. The use of their names was prevalent mainly among younger people, and as a participant, (Henry: Male 56) puts it ‘they [names] started off as nicknames and become so popular that they were later bestowed as given names’. This account reveals that invented names have a link to the past.

Another process of hybridisation involves combining initial elements of original names with final English output to derive the hybridised version as we can see in Table 13 below:

Table 13: Innovative hybridised names

This hybridisation process involves blending a part of the sound of the original name with a stressed syllable that produces some phonetic effect. A participant (Eddy: Male 28) described this naming trend as ‘a funkified [flowery] concept which makes one's name to shine like a star.’ This creative enterprise is popular among students in institutions of higher learning. Another participant (Skenzy: Female 26) said that she preferred her trendy name because it specifies her class, taste and sophistication. This details the fact that beyond using this category of names to reconstruct a new form of identity, participants also used it to enact other subcultural capital like fashion, beauty activities and economic empowerment.

Tonal alteration

Another important way of Englishising Nigerian names is through tonal alteration which also indexes power relations. A high-low (HL) tone superimposed on a two syllable names indicates a high social status, but a high-high (HH) or low-low (LL) tone on the same name represents a low or inferior social class. This power differential in naming is illustrated in Table 14.

Table 14: Englishised names derived from tonal alteration

An important observation here is the asymmetrical use of the same name by their bearers. This provides an essential insight into power dynamics, social distance and level of familiarity. Only people of equal status can use the original name or Anglicised form reciprocally. If a man with power (and authority) shares the same name with a man without power (namesakes), the man with power uses HH or LL tones (depending on the tonal variation of the name) to address his subordinate who in turn can only address the man with power with HL tonal alteration of the same name. This power dynamics reinforce social division and inequality given the non-reciprocal use of the same name by their bearers. The name that carries power is generally assumed to be the anglicised form. Mashiri (Reference Mashiri1999: 94) calls this dimension of inequality ‘non-reciprocal power distinction’. It describes power semantics that is driven by dominance and inequality and ‘illustrate[s] hierarchical characterisation of relationships’ (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Nagata, Nagao, Miyai and Iizuka1981). This account shows that beyond prestige and global identity, Englishised names can also confer social power.

Discussion

The rising profile of English as ‘a global language’ (Graddol, Reference Graddol2006: 59) has reinforced its domination and important role in numerous cultural contexts across the world, including sports, trade, media, business, academics and science (Rubdy & Saraceni, Reference Rubdy and Saraceni2006). This has resulted in the spread of Anglo-American hegemony to all parts of the globe (Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2011), which has suppressed and very often displaced some indigenous languages and cultures. In Nigeria, English is no longer seen as a tongue of the oppressor but as performing a useful function in a multilingual setting (Spichtinger, Reference Spichtinger2003). The influence of English in Nigeria covers every facet of Nigeria's socio-political, economic and cultural life. Proficiency in English in most sociolinguistic domains confers privileges and social benefits.

The global dominance of English has ‘compromised the cultural integrity of the non-native speaker’ (Modiano, Reference Modiano2001: 339), and in Nigeria, this clearly manifests in the Englishisation of ethnic personal names. The Englishisation of names in Nigeria can best be described as the ‘legitimisation of linguistic superiority’ (Hamel, Reference Hamel2005: 8), which has the effect of eroding Nigeria's cultural values, norms and heritage. The practice remains one of the linguistic legacies that imperialism has bequeathed Nigerians as a people (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson1997). It is also a form of cultural hegemony by which globalisation has permitted the exercise of domination in cultural relationships wherein the values, practices, and meanings of a powerful foreign culture are imposed on the native cultures (Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson1991). The Englishisation of indigenous personal names in Nigeria, therefore, explains the enforced adoption of cultural habits and customs of imperial occupying powers (Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson1991). It displays power asymmetry, permits English to overshadow Nigeria's local cultures and exhibits a pernicious impact on weaker Nigerian cultures.

The Englishisation of Nigerian names is also an output of language contact. Mensah (Reference Mensah2015a) maintains that names are lexical items that exist in a language and are susceptible to contact influence. Contact is determined by a given sociolinguistic situation and not necessarily by linguistic constraints (Thomason & Kaufman, Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988). In situations of intense contact between speakers of English and Nigerian languages, the people with more socio-economic and political power are usually the source of influence, and the more intense the contact, the more opportunity there is for bilingualism to develop. Most of the a,nglicisation processes discussed in this paper are direct consequences of the adoption of a new vocabulary or stylistic borrowing of features from English which are held in high esteem and believed to confer a sense of prestige and power.

Most bearers and givers of Englishised names ideologically believe that English is superior and more prestigious than Nigeria's indigenous languages and cultures (Essien, Reference Essien, Wolf and Gersler2000), at the expense of their cultural identity. It is this ideology of embracing a foreign culture that has promoted the anglicisation, hybridisation and alteration of their indigenous names, which has become a way of life for some Nigerians. This highlights the fact that in an increasingly globalised and inter-connected world, naming can traverse ethnic and linguistic boundaries and offer strong links and pathways to modernity and social privileges. The Englishisation of names as a cultural practice will continue to sustain the marginalisation and domination of Nigerian languages and cultures if a deliberate intervention programme is not soon initiated. This article is therefore a clarion call on Nigerians to reawaken interest in practices that preserve and promote Nigerian languages and cultures and not those that will diminish them.

Conclusion

In this article, the Englishisation of indigenous personal names in Nigeria was explored using the Efik and Ibibio onomastic traditions as reference points. The research identified Anglicisation, hybridisation and tonal alteration as the key process of Englishising Nigerian names. The socio-historical dimension of name changing, substitution, translation, modification and alteration has been traced to precolonial and colonial periods, when contact between European missionaries and colonial administrators on the one hand and Nigerian languages and cultures on the other was most active. The study discovered an overwhelming preference for Englishised names among the sampled population, who mainly see these innovations in naming as fashionable styles and trends that connect with modernity. The article concludes that the Englishisation of personal names in both the Efik and Ibibio cultures is strongly related to favourableness toward English and the relative perceptions of prestige and power that often accompany such names. The study has implications or language contact and bilingualism in Nigeria, and aims to deepen our understanding of the intersection of linguistic ideology, cultural diffusion and identity. It will contribute to current debate and theory on global English.

DR. EYO O. MENSAH is an associate professor of structural and anthropological linguistics at the University of Calabar, Nigeria. He is a Marie A. Curie FCFP Senior Fellow and Guest Professor at FRIAS, University of Freiburg, Germany. He is the pioneer president of Nigerian Name Society (NNS). His research interests include morphosyntax, pragmatics, language and naming, language and sexuality and youth language. He is AHP/ACLS postdoctoral fellow, Leventis postdoctoral researcher, and Firebird Anthropological research fellow. His latest publications have appeared in Anthropological Quarterly, Gender Issues, Linguistics Vanguard, International Journal of Language and Culture and Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics. He is the Review Editor of Sociolinguistic Studies, and also serves as a member of the University of Calabar Governing Council. Email: eyomensah2004@yahoo.com

DR. EYO O. MENSAH is an associate professor of structural and anthropological linguistics at the University of Calabar, Nigeria. He is a Marie A. Curie FCFP Senior Fellow and Guest Professor at FRIAS, University of Freiburg, Germany. He is the pioneer president of Nigerian Name Society (NNS). His research interests include morphosyntax, pragmatics, language and naming, language and sexuality and youth language. He is AHP/ACLS postdoctoral fellow, Leventis postdoctoral researcher, and Firebird Anthropological research fellow. His latest publications have appeared in Anthropological Quarterly, Gender Issues, Linguistics Vanguard, International Journal of Language and Culture and Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics. He is the Review Editor of Sociolinguistic Studies, and also serves as a member of the University of Calabar Governing Council. Email: eyomensah2004@yahoo.com