On 24 June 1559, less than a year after the state-sponsored restoration of English Catholicism came to an abrupt end with the death of Mary Tudor, Elizabeth I's government passed ‘An act for the uniformity of common prayer and divine service’. This new law required that ‘all and every person…shall diligently and faithfully, having no lawful or reasonable excuse to be absent’, be present at their parish church ‘during the time of the Common prayer, Preachings or other service of God’ – services which, if not strictly ‘Protestant’, were certainly no longer Catholic.Footnote 1 In the face of this religious settlement, English Catholics have long been depicted as both confused and divided; as early as 1600, the English Jesuit Robert Persons explained how the former clergy of Mary's reign descended into ‘sharpe bickerings’, whilst the laity, deprived of clear clerical leadership, drifted towards quiet conformity.Footnote 2 Persons lamented how ‘all (excepting very few) went to [the Protestant] Churches, sermons, and Communions’.Footnote 3 In the Jesuit's opinion, it was mainly thanks to the ‘practise, zeale and authority of priests comminge from the Seminaries beyond the seas’ after 1574, and later his fellow Jesuit missionaries, that the issue of Catholic attendance at Protestant services ‘hath byn cleared and the negative parte fully established’.Footnote 4 Without this injection of religious steroids from abroad, English Catholicism would have died a slow and unheroic death.

This decidedly Jesuitical interpretation of the origins of Elizabethan recusancy has exerted, and continues to exert, a profound influence over historians’ understanding of the period from 1558 to 1574. In 1975, John Bossy labelled these years ‘the death-throes or posthumous convulsions of a church’, seeing conscientious, nonconformist Catholicism as the creation of continentally trained missionary priests from c. 1574 onwards.Footnote 5 Christopher Haigh criticized this ‘fairy story’ in 1981, instead suggesting that, thanks to the efforts of dedicated Marian clergymen, ‘by the time the seminary mission and later the Jesuits had an impact upon England, there already existed the essential concept of a separated Catholic church’.Footnote 6 However valiant as the efforts of this ‘small rump of recalcitrant priests’ were, even Haigh admitted that their activities were highly localized and sporadic, and their beliefs ‘curious and confused’ until at least the early 1570s.Footnote 7 Like both Bossy and Persons, Haigh thereby re-emphasized the importance of continentally trained missionaries for transforming recusancy from a disparate and amorphous phenomenon into a distinct and articulate movement.Footnote 8 It was still these missionary priests, the first to bring into England that potent combination of doctrinal rigidity and creative evangelism at the heart of the continental Counter-Reformation, who saved English Catholicism from eternal obscurity. Such an interpretation remains largely unaltered today, one historian reiterating as recently as 2014 that ‘the drive for comprehensive separation [from the Church of England] did not really gather momentum until the arrival of the first contingent of seminary-trained missionaries in 1574’. Persons's ‘fairy story’ continues to be told.Footnote 9

Recent reassessments of the reign of Mary I have the potential to reinvigorate this interpretation. Until relatively recently, Mary's reign was viewed as a failed attempt to resuscitate a dying faith. Historians such as A. G. Dickens and David Loades saw in Marian Catholicism little more than an ill-educated and disinterested priesthood, cut off from the currents of the continental Counter-Reformation and preaching an outdated creed.Footnote 10 However, recent work by Thomas Mayer, William Wizeman, Eamon Duffy, Elizabeth Evenden, and Thomas Freeman has opened our eyes to the vibrancy, strength, and zeal of Mary's leading clergy. They have identified in the Marian church many traits which would later become the hallmarks of the continental Counter-Reformation in the wake of the Council of Trent.Footnote 11 Duffy even went so far as to suggest that Mary, alongside her cousin, the papal legate Cardinal Reginald Pole, ‘“invented” the Counter-Reformation’ in England.Footnote 12

Whilst Duffy may have been exaggerating for effect, he nevertheless makes an important point. The Catholicism of Mary's reign was ‘subtly but distinctively different from the Catholicism of the 1520s’.Footnote 13 This is not to say that the medieval church was spiritually moribund, nor that it failed to inspire the devotion of large swathes of English people across the social spectrum.Footnote 14 However, as numerous historians have begun to demonstrate, under the guidance of Cardinal Pole and a number of influential Spanish clergymen, Marian Catholicism built upon the most promising developments of its past, such as the move towards a greater inner spirituality, whilst tackling those abuses which most inspired the ire of Protestants, particularly the low moral and intellectual standing of both clergy and laypeople. In its attempts to reform the church, Marian Catholicism borrowed strategies and ideas from Protestantism itself, as well as from the reforming experiments of other continental Catholic powers. It also pioneered several of its own measures, some of which were later endorsed and adopted by that bastion of continental Catholic reform, the Council of Trent. Indeed, several former Marian clergymen and theologians, including the polemicist Nicholas Sander and bishop of St Asaph Thomas Goldwell, attended the final sessions of Trent, where the acts of Pole's 1555 legatine synod were read and discussed.Footnote 15 Marian Catholicism coupled these reforms with a greater doctrinal rigidity, clarifying the core of Catholic doctrine and transmitting it to the laity through the creative use of preaching and catechesis, as well as the unflinching repression of deviance. The result was a far more clearly defined, perhaps even ‘confessionalized’, faith.Footnote 16 It is this combination of a rigorously enforced, proto-Tridentine doctrinal rigidity, together with a willingness to experiment with creative strategies of reform and evangelism appropriated from both reformed Catholic and Protestant sources, which justifies referring to Marian Catholicism as a Counter-Reformation church.

This on-going reassessment has significant implications for our understanding of early Elizabethan recusancy. If the clergy of Mary's reign were already engaging with the ideas and strategies of the Counter-Reformation, then these same ideas would presumably have conditioned their response to the Elizabethan religious settlement throughout the 1560s and beyond. If this is the case, the foundations upon which current understandings of English Catholicism in the first decade and a half of Elizabeth's reign rest appear to be in need of substantial modification. This article re-examines the importance of the Marian clergy for early Elizabethan recusancy through an analysis of a group of priests at the very heart of the Marian restoration – the cathedral clergy.Footnote 17 Following an investigation of just how integral these priests were to the development of Mary's church, it will examine the activities of those cathedral clergymen deprived by Elizabeth for their religious beliefs. Through a re-reading of church court proceedings, state papers, and polemical treatises, this article suggests that the cathedral clergy's ‘upbringing’ under Mary prepared them to become the leaders of a co-ordinated and creative campaign in favour of principled nonconformity with the Church of England from as early as 1560 – a campaign which was developing its own distinctive ‘ideology of recusancy’ and exhibiting a cutting-edge evangelism long before the first missionaries set foot on English soil.

I

Mary's death and the subsequent imposition of the Elizabethan religious settlement brought with it the deprivation or resignation of 49 per cent of the higher (title-holding) cathedral clergy in England.Footnote 18 This represented twenty-one archdeacons, thirteen deans, four chancellors, four treasurers, and two precentors over the first five years of Elizabeth's reign. They were joined by as many as ninety lesser English cathedral canons and prebendaries.Footnote 19 The remaining 51 per cent of the higher cathedral clergy were split between those who died within a few years of Elizabeth's accession (most from the influenza epidemic which coincided with Mary's death) and those who nominally conformed and retained their ecclesiastical positions. Whilst this article is concerned only with those clerics deprived by Elizabeth, the apparent conformity of those who retained their positions cannot be taken as evidence of a lack of religious conviction. As Peter Marshall and John Morgan explain in a recent article, many of these clerics may never have been offered the Oath of Supremacy at all, whilst others retained their positions even after having rejected it.Footnote 20 Moreover, at least some of these ‘conforming’ cathedral clergymen were directly involved in ‘nonconformist’ activities. Treasurer of Hereford and chancellor of Exeter, William Lewson, retained both his benefices until his death in 1583, yet he was repeatedly admonished by Bishop Scory for harbouring recusant priests and refusing to read the officially prescribed homilies.Footnote 21 The contribution of ‘conforming’ clerics such as Lewson to early Elizabethan Catholicism is a topic worthy of study in its own right.

Cardinal Reginald Pole, advised by his bishops and those clerics who accompanied Philip II to England in 1554, is usually cited as the ‘single most influential figure in the Marian restoration’, his hand discernible in every aspect of the practical programme which brought about the revival and reform of Catholicism in England.Footnote 22 However, whilst Pole may have been the visionary at the head of Mary's church, the cathedral clergy became the most enthusiastic and effective instigators of his reforms at ground level.

These clergymen's commitment to the restoration is shown most clearly in their activities as polemicists. As William Wizeman has argued, through a steady stream of printed catechetical, devotional, and polemical works, Marian theologians succeeded in articulating ‘much of the Counter-Reformation avant la lettre’. Collectively, these tracts not only defined a remarkably uniform Catholic theology which ‘followed, paralleled and anticipated the decrees of the Council of Trent’, but they also advocated the same Christocentric spirituality as that icon of the continental Counter-Reformation and founder of the Jesuit order, Ignatius Loyola. Moreover, in their emphasis on lay catechesis and clerical instruction, these texts echoed the priorities of numerous Protestant critics of the ‘old faith’.Footnote 23 Although the bishops feature heavily in this printed polemic, six prominent authors who contributed to the development of Marian spiritualty in print were cathedral clergymen.Footnote 24 Four of these, John Feckenham (dean of St Paul's, 1554–6, and subsequently abbot of Westminster until 1559), John Harpsfield (dean of Norwich, 1558–9), Roger Edgeworth (chancellor of Wells, 1554–9), and John Standish (archdeacon of Colchester, 1558–9), would suffer deprivation at the hands of Elizabeth, whilst the other two, Hugh Glasier (canon of Canterbury, 1541–58) and Henry Pendilton (prebendary of Reculversland, St Paul's, 1554–7), died before she took to the throne.Footnote 25 Harpsfield's and Pendilton's works were particularly influential, their homilies being included in Bishop Bonner's Profitable and necessarye doctryne – a collection which not only laid out the fundamentals of Catholic doctrine clearly and simply, but also, in its extensive use of scriptural quotations, exhibited a willingness to ‘wrench the reformers’ weapons from their hands and turn them on them’.Footnote 26

Once again appropriating the strategies of their adversaries, the cathedral clergymen resorted enthusiastically to the pulpit in order to disseminate Marian theology and spirituality amongst the laity.Footnote 27 John Feckenham, John Harpsfield, Henry Pendilton, John Standish, and William Chedsey (archdeacon of Middlesex, 1556–9) are frequently noted throughout the ‘diary’ of the London merchant taylor and chronicler Henry Machyn as having preached from London pulpits, particularly Paul's Cross where there was often a ‘grett audyense’.Footnote 28 Others, in a form of creative evangelism more usually associated with the Protestant martyrs and later the Jesuits, used preaching in order to exploit the ‘theatre of punishment’ that was public execution.Footnote 29 For example, Henry Cole (dean of St Paul's, 1556–9) treated the spectacle of Thomas Cranmer's burning in Oxford as ‘an example to teach them [i.e. the onlookers] all’ as to the dangers of breaking from the unified teachings of the Catholic church.Footnote 30 This commitment to preaching was not confined to London – cathedral clerics in Salisbury, Lichfield, and Chichester were involved in similar activities.Footnote 31

Other cathedral clergymen became involved directly with catechesis. The eleventh decree of Cardinal Pole's legatine synod of 1555 proposed that ‘in cathedrals a certain number of initiated persons be brought up, whence as from a seminary, men may be chosen who may be worthily put in charge of churches’ – a decree which Duffy suggested may later have inspired a similar Tridentine enterprise.Footnote 32 Although this decree was never formally instituted in England, four cathedrals (York, Lincoln, Wells, and Durham) founded such dean and chapter schools on their own initiative in the wake of the synod, demonstrating a zeal and enthusiasm which put the later efforts of their continental counterparts to shame.Footnote 33

The cathedral clergy were also amongst the most active defenders of the faith. As David Loades has observed, ‘the most enthusiastic heresy hunters’ were not bishops, but ‘deans, archdeacons and lay officials’.Footnote 34 At least a quarter of those higher cathedral clergymen later deprived by Elizabeth were directly involved with the burnings, with many others almost certainly acting behind the scenes. For example, Nicholas Harpsfield (archdeacon of Canterbury, 1554–9) was cited by John Foxe as having ‘excelled in perscutyng the poore members and saintes of Christ’.Footnote 35 Foxe attributed Canterbury's disproportionately large number of persecutions to the ‘furious and firy’ nature of the archdeacon.Footnote 36 Equally deserving of Foxe's condemnation was Michael Dunning (archdeacon of Bedford, 1558–9), a key figure in the heresy campaign in Norwich.Footnote 37 According to Foxe, countless ‘simple and faithfull Saintes of the Lord’ had been ‘rigorously condemned and murthered’ by the archdeacon.Footnote 38 It is clear, even from Foxe's heavily glossed account of the persecutions, that these clerics saw their role in the burnings as a form of ‘charitable hatred’ – an unsavoury yet necessary duty for the protection of their church.Footnote 39 Foxe himself provides us with numerous examples of the lengths to which these clerics went to avoid sending Protestants to the flames if their salvation could be procured by other means. When faced with a group of three intractable Protestants, Archdeacon Dunning ‘burst out in teares’, desperately pleading them ‘to turne agayne to the holy mother church’, and ‘not wilfully cast away themselues’.Footnote 40 The discord embodied by heresy was seen as posing a very real threat to the harmony and agreement of the church. Canterbury Canon Hugh Glasier likened it to a ‘pestiferous disease’ which threatened to poison and ‘destroy’ not only the heretics themselves, but also the entire country.Footnote 41 If such heretics could not be reclaimed to the ‘unitie of Christes church’, their execution served as charity toward the Catholic community – it protected true believers from infection and preserved that doctrinal unity so integral to the aims of the Council of Trent and the wider Counter-Reformation.Footnote 42

II

From the brief survey above, it seems clear that the cathedral clergy were amongst the most active and vociferous agents of Marian Catholicism. In their roles as polemicists, preachers, persecutors, and teachers, they appear to have recognized the need to respond creatively to the challenges of Protestantism, learning from the conduct of their adversaries and embracing the mantra at the heart of the continental movement for Catholic reform – doctrinal uniformity coupled with creative and energetic evangelism. But how did this Marian ‘upbringing’ influence these cathedral clergymen's actions following deprivation?

Of the higher cathedral clergy, seven died within two years, whilst ten fled abroad. By far the largest number, twenty-two, remained in England, half of whom managed to avoid arrest for at least part of the 1560s and early 1570s.Footnote 43 Along all these paths, the higher cathedral clergy were followed by groups of lesser prebendaries and canons. What follows is an analysis of these various post-deprivation trajectories. Although these pathways will be dealt with separately, this article suggests that such divisions are artificial – that, despite their differing paths, these deprived cathedral clerics may have been united in a singular campaign to promote recusancy in England.

Those individuals who remained in England but avoided arrest form the first group for investigation. Since priests who remained in London or the Home Counties tended to be arrested fairly quickly, most of the evidence for this group comes from the north where the government's authority was weaker. It seems fitting to start with a county central to many of Christopher Haigh's conclusions regarding early Elizabethan Catholicism, Lancashire, in order to ascertain the roles former cathedral clerics may have played in a diocese known for its early manifestations of Catholic nonconformity.Footnote 44 However, the discussion will then move on to examine the activities of cathedral clergymen throughout the north of England and beyond.

The earliest foundations for recusancy in Lancashire seem to have been laid by a group of clergymen headed by two cathedral prebendaries: John Morren and Laurence Vaux. Under Mary, John Morren held the prebend of Weldland in St Paul's and served as the personal chaplain to Bishop Bonner.Footnote 45 He first came to the government's attention in June 1561 when he distributed a polemical tract about the streets of Chester. It affirmed that English Catholics could not, under any circumstances, communicate at services with Protestants since ‘[i]n receiving the communion as now used, you break your profession made in baptism, and fall into schism, separating yourselves from God and his church’.Footnote 46 Not only would such an act separate one ‘from the unity of the catholic church’, but it ran the risk of infecting the whole flock through evil example.Footnote 47

It has been assumed that this was as far as Morren went in his advocacy of recusancy; however, a closer reading of the tract suggests otherwise.Footnote 48 Alongside Morren's utter dismissal of communication with Protestants lay a subtler, but equally fervent, belief that no true Catholic would allow themselves to be present at heretical services. He railed against the ‘manner of service now used in the church’, arguing that it had no precedent in scripture. It was therefore ‘to be rejected and put away, as a new-fangled doctrine and schismatical’.Footnote 49 He explained how no Catholic priest could read from the schismatical Book of Common Prayer, and, backing up his argument, quoted from the canons of the apostles, ‘[i]f any of the clergy or laity shall enter into the synagogue of the Jews, or the company of the heretics, to say prayers with him, let him be deposed’.Footnote 50 Avoiding his own voice to advise Catholics to forsake heretical services, he appropriated the voice of scripture.Footnote 51

Working alongside Morren in Lancashire was Laurence Vaux, prebendary of Minor Pars Altaris in Salisbury diocese from 1556 until his deprivation, as well as warden of the refounded collegiate church in Manchester.Footnote 52 At some point prior to October 1564, Vaux fled to Louvain where he taught the families of English Catholic exiles. However, by 2 November 1566, he had returned to Lancashire, armed with a circular letter from the Louvain polemicist Nicholas Sander. This letter explained in no uncertain terms that attendance at the services of Protestants was wrong. Although the original letter is no longer extant, a further missive, written by Vaux, which reiterated Sander's message is amongst the state papers. It clearly recounts Sander's belief that ‘if ye associate yourselfes at sacramente or servise that is contrarie to the unitie of Chryste his Churche ye fall in Scysme’.Footnote 53

In November 1568, John Morren, alongside another priest, John Peele, were reported circulating the aforementioned letter from Nicholas Sander which Vaux had brought into the county. Apparently Morren and Peele had also been administering a ‘vowe’ to various gentlemen in southern Lancashire, binding them to ‘take the pope to be supreme heade of the churche’, and ‘doe all thynges accordynge to the wordes of [Sander's] letter’ – i.e. to avoid associating themselves ‘at sacramente or servise that is contrarie to the unitie of Chryste his Churche’.Footnote 54 Several chose to go ‘past a vowe’ and ‘toke a corporall othe on a booke’. Such an oath had apparently been administered to as many as twenty-two members of the Lancashire gentry.Footnote 55 Jonathan Gray has explained how the use of oaths in this period could prove an effective method for legitimizing resistance to a monarch. Having sworn an oath, as Gray has explained, ‘keeping that oath became a matter of being obedient to God, and obedience to God trumped all other forms of obedience’. It seems likely that Morren encouraged these gentlemen to make a ‘corporall othe’, rather than a mere ‘vowe’, in order to help legitimize their conscientious rejection of the Elizabethan settlement.Footnote 56 Just like the later seminary and Jesuit missionaries, these cathedral clergymen were devising creative ways by which to disseminate their message amongst the laity.

Although Vaux again retreated to the continent after this second foray into north-west England, he remained constant in his belief that conformity with Protestantism was wrong. In 1568, he published an English catechism. This work has traditionally been dismissed as ‘old-fashioned, even for its day’ – completely out of touch with both the realities of English Catholicism under Elizabeth, and the new direction of continental Catholicism post-Trent.Footnote 57 However, Alexandra Walsham has recently questioned this interpretation. By tracing the influence of the catechetical works of Dutch Jesuit Peter Canisius on Vaux, she has demonstrated how the former College warden ‘adapted and domesticated’ Canisius's work, thereby bringing ‘both the catechetical impulse and the political agenda at the heart of the Society of Jesus into England even before the Jesuits set foot in it themselves’.Footnote 58 Just like the later Jesuits and seminary-trained priests, Vaux adopted an uncompromising attitude towards English Catholics who had not stood up for their beliefs. He repeatedly emphasized that a true Catholic must profess his faith ‘in harte, word, and deede’. Those who refused to do so publicly were guilty of breaking the First Commandment. This remained true regardless of the dangers involved, ‘for a Christian man ought to be of such constancie, that he should rather suffer his life to be taken away from him, than his faith’.Footnote 59 Not even the ‘feare of Princes, Lordes, Magistrates or Maisters’ was enough to coerce a true Catholic to deny the church of Christ, since the displeasure of God would far outweigh that of a temporal ruler.Footnote 60 Nor could a faithful Catholic hide his or her beliefs, since it was ‘forbidden to use dissimulation in woordes or deedes’.Footnote 61 Thus, although Vaux's catechism drew short of explicitly instructing English Catholics to forsake Protestant services, it left the conscientious and devout reader with little other option if they wanted to live up to its strict Tridentine standards of piety. The message was simple – stand up and be counted, or count yourself out.

Alongside clear borrowings from the Jesuit Peter Canisius, Vaux's militant stance might also have been influenced, at least unconsciously, by an awareness of those tracts condemning conforming ‘Nicodemites’ which had been produced on Protestant presses during Mary's reign. Although Vaux makes no explicit references to any of these tracts, Protestant anti-Nicodemite literature was relatively widespread in England throughout the 1550s, and would therefore almost certainly have been known to this cathedral clergyman.Footnote 62 It seems as though that same willingness to appropriate the strategies of both Protestants and continental Catholics, so apparent in Marian England, seems to have been alive and well in the person of Laurence Vaux.

The efforts of Vaux and Morren helped encourage the development of a wider network of recusant priests in Lancashire and the surrounding counties, united in their condemnation of the Protestant church services. This much is clear from the proceedings of the local ecclesiastical commission in 1568. Following his visitation of Chester diocese, and in response to a royal admonition to stem the spread of Catholicism therein, Bishop Downham arranged for a trial of eight gentlemen of prominence who had been highlighted in the visitation returns as unfavourable to the Protestant religion. They stood accused of failure to attend or communicate at church, and of harbouring a group of priests who the authorities knew to be operating in the area. At the heart of this group were Vaux and Morren. However, they were now joined by nine other priests including Richard Marshall (former dean of Christ Church, Oxford), Thomas French, and James Hargreaves (deprived vicar of Blackburn).Footnote 63 The answers given by the Lancashire gentry to these allegations suggest that the clergymen listed above had been working as a team throughout the diocese in order to push the laity into recusancy. Seven of the Lancashire noblemen admitted that they had not received the holy sacrament in the past year, and four of these (John Talbot, John Westby, Matthew Travers, and Edward Osbaldeston) had not attended church at all. All except one (John Rigmaiden) admitted to hosting one or more of the aforementioned priests over the course of the 1560s.Footnote 64

Having concluded the 1568 trials, Bishop Downham, anxious to appease the queen, suggested to Cecil that the recusancy problem had been resolved. He confidently stated that, the principal offenders having been punished and brought to conformity, ‘I trust I shall never be trobled agayne with the like.’Footnote 65 However, other local officials did not share Downham's optimism. In November 1568, Mr Glasior, ecclesiastical commissioner and vice-chamberlain of Chester, wrote that ‘great confederacyes are prestntly in Lanceshyer by sundry papistes their lurkinge who have sturred dyvers gent to their facion and sworne theym together not to come to the Churche’. He feared that ‘this confedracye is so great that it will gro to a commocion or rebellion’.Footnote 66 It has been assumed by J. Stanley Leatherbarrow that Glasior's remarks were merely the ‘alarmist’ tactics of an individual seeking to win the queen's favour through the intensity of his religious zeal.Footnote 67 However, closer investigation reveals that such an organized ‘confederacye’, although unlikely to incite rebellion, did exist, and that it stretched throughout the diocese.

The same group of priests implicated in the 1568 trials appears repeatedly throughout the early 1570s and beyond, consistently in connection with the recusant activities of the laity. In 1576, Anthony Travers of Preston was charged with obstinate absenteeism and associating with Laurence Vaux, John Morren, James Hargreaves, Thomas French, and others. He admitted that he had absented himself from church and not received communion for four and a half years. His recusancy had been sustained through his frequent relations with French and Hargreaves, with whom he ‘hath bene conversant and familier’. His associates, ‘Mr Singleton, Mr Clifton, and Mr Westbye [presumably the same Mr Westby who had admitted to recusancy in 1568]’, with whom he had attended numerous masses, seem to have become central pillars of the Lancashire recusancy network. According to Travers, they had ‘dvers tymes had companyon in ther howses with distinguysed preistes whom they called Maisters’. Although Travers could not give the names of these priests, the fact that ‘he suspecteth vehementlie that the said gentlemen were reconciled by some aucthoritye from the pope’ suggests the hand of Laurence Vaux and John Morren.Footnote 68 Travers had himself ‘dyvers tymes’ spread the message of recusancy, defending the ‘popishe Religion’ and speaking ‘against the Religion now established’. In 1574, John Petty of Ulverston was similarly charged with having forsaken communion, being ‘an open misliker of the religion’ and of associating with Vaux, Morren, and Hargreaves, together with other former parish priests such as Robert Copley. Whilst Petty denied all charges, the trial indicates clearly that the high commission continued to associate recusancy directly with these cathedral clergymen and their ever widening group of followers.Footnote 69

Although Vaux had travelled to the continent by the end of the 1560s, Morren is reported, as late as 1580, as having been harboured by Lady Mary Egerton of Ridley in Bunbury. Lady Mary, ‘hir gentlewomen, and divers others of her retynue’ were reported to ‘resorte not to Churche’ throughout the 1580s and 1590s.Footnote 70 Vaux later returned to England, along with another seminary-trained priest, as part of the English mission in 1580, when he was immediately arrested and imprisoned.Footnote 71 Richard Marshall, who was in Douai by 1575, may too have returned to his homeland in 1591, forming part of a ‘company’ of ten individuals, at least one of whom was a Jesuit.Footnote 72 It would seem, therefore, as though both the Jesuits and seminarians respected and valued these former cathedral clerics as effective missionaries – perhaps they too were impressed by their proselytizing zeal?

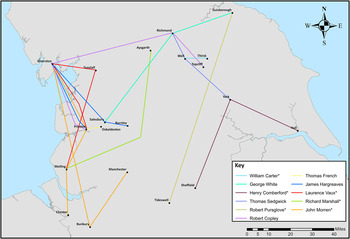

Charting the locations where these clergymen were operating reveals a surprising degree of mobility and interconnection. Figure 1, created using data drawn from the surviving records of Lancashire and Yorkshire recusancy trials, plots the paths of various cathedral clergymen (as well as the priests who worked alongside them) throughout northern England for the period 1559–80.Footnote 73 It seems that, far from ‘localised and sporadic’ (as previous historians have suggested), these priests operated over large areas which straddled county boundaries.Footnote 74 Laurence Vaux, together with John Morren, Richard Marshall, and John Peel, had been at the house of John Mollineux in Melling, southernmost Lancashire, repeatedly between 1565 and 1568, but Vaux had also spent the summer of 1567 nearly fifty miles north at Francis Tunstall's house in northern Lancashire.Footnote 75 John Morren appears to have been particularly mobile, supposedly residing in Chester in 1561, at the house of John Mollineux in Melling between 1565 and 1568, in Ulverston, modern-day Cumbria, in 1574, and in Bunbury near the Welsh border by the early 1580s.Footnote 76

Fig. 1. Map to show movement of deprived Marian clergy in northern England, 1559–80. Those priests marked with an asterisk in the key are cathedral clergymen. All others are priests known to have associated closely with these men. Contains National Statistics and OS data @ Crown copyright and database 2012.

Figure 1 also reveals considerable connections between Lancashire and the neighbouring county of Yorkshire. In 1572, the same John Talbot who had admitted to recusancy at the Lancashire trials of 1568 was once again in trouble with the authorities. He admitted that he had avoided church services and not taken communion for five years.Footnote 77 He stood accused of harbouring a priest named George White. White appears on a list, drawn up by the York high commission in the same year, as one ‘makinge there abode in the liberties of Richmonde’ and reconciling others to Rome.Footnote 78 Although it is impossible to be certain that the same man is intended, a priest by the same name also appears on the 1561 statutes for a school in Guisborough.Footnote 79 This school had been founded, alongside another similar one in Tideswell, Derbyshire, by Robert Pursglove, deprived archdeacon of Nottingham and suffragan bishop of Hull. An anonymous manuscript dating from c. 1588 and entitled An answer to a comfortable advertisement, labelled Pursglove a ‘schismatyke’ and ‘scandalous newter’.Footnote 80 However, this reputation is perhaps unfounded; George White was not the only individual associated with one of the former archdeacon's schools to be accused of recusancy. Roger Tocketts, whose name appears as one of the original wardens of the Guisborough school, was in the prison of York Castle for refusal to attend church from 1571 to 1576, and later transferred to Hull.Footnote 81 Another master of the school, Michael Tirry, later joined him there for the same reason.Footnote 82

Pursglove's other school in Tideswell proved a similar breeding ground for recusancy. William Fieldsend, vicar of Tideswell and guardian of the affairs and property of the foundation, ended up imprisoned in the North Blockhouse in Hull on account of his religious beliefs.Footnote 83 Similarly, the children of Robert Tunstead, himself partly responsible for the election of the schoolmaster, were repeatedly involved in Catholic conspiracies; John Tunstead appointed several known recusants to important positions in local government, whilst his brother was suspected of involvement in the Babington conspiracy.Footnote 84 The Catholic martyr Nicholas Garlick may also have taught at the school for seven years, during which time he influenced three of his students to travel with him to the English College at Rheims and later return as part of the English mission.Footnote 85 Far from being a ‘scandalous newter’, Pursglove seems to have harnessed the proto-Tridentine educational impulses which had begun to emerge during Mary's reign in order to inspire both his teachers and pupils to forsake Protestant services throughout the north of England.Footnote 86

Another connection between Lancashire and Yorkshire can be found in the person of Robert Copley, the former parish priest who had supposedly been operating alongside Laurence Vaux and John Morren in 1574. Earlier in the 1560s, this priest had been at the residence of the earl of Northumberland in Ripon, Yorkshire. Following his arrest for involvement in the 1569 rebellion, Northumberland was questioned by the high commission. He admitted that he had been persuaded ‘how enormouslye [the Protestants] mysconstrew the word of God’ through his reading of certain tracts by ‘Harding, Sander, Stapleton, and others’, and that he had been ‘reconsyled by one Master Copley, two yeares and more, before our sturr’.Footnote 87 It seems probable that it was through Copley that the earl acquired these Louvainist tracts which led to his conversion, demonstrating how links with Catholics on the continent were maintained throughout this period.

Copley was not the only priest to be operating in the vicinity of Ripon throughout the 1560s. Judging from an anonymous letter sent to Cecil on 6 February 1570, the recusant ringleaders in this region were William Carter (archdeacon of Northumberland, 1558–9) and Dr Thomas Sedgwick, Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge during Mary's reign.Footnote 88 The letter explained how, having ‘lurked’ within sixteen miles of Thirsk and Richmond respectively, these two ‘archpriests’ had ‘so practised that those two towns and the towns adjoining’ had risen in the northern rebellion ‘for recovery of their popish mass’.Footnote 89 Although it seems unlikely that these two priests could have inspired such unrest unaided, it is certainly suggestive that the vast majority of Yorkshire rebels involved in the northern rebellion hailed from the two towns of Richmond (101 individuals) and Thirsk (97 individuals).Footnote 90 By 1572, the number of priests actively reconciling individuals to Rome in the Richmond/Thirsk area had swelled to eleven, including both Robert Copley, reconciler of the earl of Northumberland, and George White, the Guisborough school warden, noted above.Footnote 91 Again, it seems that the actions of a core group of Marian clergymen, the most prominent of whom had been cathedral clerics, laid the foundations for a persistent network of recusancy in the area.

Robert Copley was also not the only priest directly associated with the earl of Northumberland's recusancy. On 10 November 1570, the countess of Northumberland's house at Broomhall in Sheffield was searched. Henry Comberford, a ‘masse priest’ who had held the precentorship of Lichfield Cathedral during Mary's reign, was subsequently arrested.Footnote 92 At his later examination in front of the York ecclesiastical commission, Comberford affirmed both ‘the Masse to be good’ and ‘the Pope to be supreame Head of thuniversall Churche’, beliefs he vowed to maintain ‘untill deathe’. The former precentor further claimed that it was through his efforts that the countess of Northumberland had renounced Protestantism and embraced the Catholic faith.Footnote 93

Although the countess was allegedly responsible for persuading and encouraging her husband to stand up for his Catholic beliefs and take part in the northern rebellion of 1569, her religious convictions had not always been so strong.Footnote 94 Comberford lamented that she had been ‘possessed with an evell spirite' which had caused her to ‘utter infinite and blasphemous othes to denye god and the Catholik Church’. It was only through fasting, praying, reciting of psalms, and reading of the gospel ‘where the castinge owt of devells is menciond’ that he had brought her to her senses.Footnote 95 Several historians have noted how the use of exorcism as a ‘proselytizing tool’ was a ‘crucial arm of the Tridentine missionary campaign to reconcile schismatics’ both in England and on the continent.Footnote 96 The first notable English example of exorcism used in this way was the Jesuit William Weston who, together with a team of twelve seminary priests, conducted a series of exorcisms in gentry households throughout 1585 and 1586.Footnote 97 By employing exorcism to convert the countess, it would seem that Comberford was anticipating the imaginative evangelism of later Counter-Reformation missionaries, at least four years before the first seminary priests arrived on English soil, and ten before the Jesuit mission was launched.

This was not the only way in which Comberford appears to have pre-empted the beliefs and practices of the later missionaries. In his examination, he revealed that ‘abowte tenn yeres paste whilste he was at his praiers’ he had been visited by a messenger from God. This messenger had supposedly bidden him to ‘ponder well the third Chapter of Danyell’.Footnote 98 Daniel 3 tells the story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego who, when instructed by King Nebakanezar to worship the golden idol, trusted in God and defied the king's command, ‘resolving to suffer with patience what soever [God] would permitte to fal unto them’.Footnote 99 Placed within the context of early Elizabethan Catholicism, it seems that Comberford was using this biblical story to justify his resistance to the Elizabethan settlement. The use of Daniel 3 to justify non-compliance with a ruler had been employed by Protestant anti-Nicodemite propagandists during Mary's reign and it may be that Comberford drew inspiration from these tracts.Footnote 100 However, Comberford seems to have been the first to deploy this biblical passage in a Catholic context – the next Catholic writer known to do so being the English Jesuit Henry Garnet. In the final chapter of his 1593 tract, A treatise of Christian renunciation, Garnet cited Daniel 3 to demonstrate how ‘neither could ever the fury of persecutours or extremity of torments drive the champions of Christ, to yeeld…to as indifferent thinges as going to the Church may seme to be’.Footnote 101 Thus, it would seem that a justification for Catholic recusancy usually seen as distinctive to the Jesuits can be found fully formed in the mind of a Marian cathedral clergyman at least as early as 1570.

The evidence above has dealt predominantly with those cathedral clergy who operated in northern England, an area which has long been recognized as a stronghold of Elizabethan Catholicism. It might therefore be levied that the former cathedral clerics of Mary's reign were only able to promote recusancy in areas where Catholicism already had a firm foothold. However, this suggestion is not borne out by evidence of similar clergymen operating elsewhere in England. An investigation into Marian cathedral chapters by Thomas Mayer has suggested that cathedral clergymen may have constituted ‘nuclei of Catholic resistance’ across the country, particularly in Lincoln, Hereford, and Salisbury.Footnote 102 Predominantly interested in calculating the number of cathedral clergymen who themselves became recusants, Mayer did not, however, investigate how far they may have inspired wider nonconformity throughout the 1560s and 1570s. By developing his findings for Herefordshire further, we can investigate whether the activities of cathedral clerics in the north were replicated by their brethren elsewhere in England.Footnote 103

John Blaxton (subdean, 1547–58, and treasurer, 1558–60, of Exeter), whose Marian activities as an energetic heretic-hunter earned him a scolding from John Foxe, appears to have moved to Herefordshire upon his deprivation around January 1560.Footnote 104 He was joined by Walter Mugg (prebendary of Exeter 1555–60), Thomas Arden (prebendary of Weighton, York, 1556–62, and a canon of Worcester), as well as three more obscure priests.Footnote 105 This group was to become a considerable concern to the authorities in that diocese. In August 1561, Bishop Scory wrote to Cecil describing how these clerics had been ‘so maynntained, fested, and magnified’ by the local justices of the peace that they had led a torch-lit procession through Hereford, the likes of which ‘cold not moche moare reverently have entertained Christ himselfe’.Footnote 106 In October 1564, John Scory again complained that Blaxton, aided by a band of followers which had now swelled to include six more priests, was a ‘mortall and deadly enemy to this religion’. Together, they were spreading their heretical opinions ‘from on gentlemans house to another’.Footnote 107 Blaxton was once again noted in February of the following year as having disseminated seditious works by two Catholic polemicists based in Louvain, Thomas Harding and Thomas Dorman, amongst the canons of Hereford Cathedral. Unless Blaxton had come across these works by chance, his use of them would suggest that links between the former treasurer and his co-religionists abroad were maintained throughout the 1560s. These books had been so well received by the Herefordshire canons that they were ‘extolled to the skie’, and Blaxton and his followers entertained ‘as yf thei [were] goddes angels’.Footnote 108

It seems that several who had contact with Blaxton and his growing group of supporters came to forsake Protestant church services entirely. John Scudamore of Kentchurch, a Herefordshire JP, was first noted in connection with Blaxton in 1561. Alongside William Lewson, treasurer of Hereford, he was accused of maintaining both Blaxton and the Exeter prebendary Walter Mugge.Footnote 109 That Blaxton continued to have contact with this JP is clear from his will of 1574, in which he bequeathed to Scudamore, ‘all suche money of myne remayninge in his hand’.Footnote 110 When asked to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity as required of all JPs throughout the country in 1569, Scudamore ‘did there and then expreslye and more earnestlye then becam hym Refuse to subscribe’.Footnote 111 He later confessed that he was ‘resolved not to subscribe’, adding that, ‘if hit will please you to take my bounde of 100 marks for the good aberyng, saving comyng to churche or not comyng, and saving matters of religion or any maner thing towching the same, or towching my poor conscience therin, I can be contented’. He emphasized that his reason for refusal was not obstinacy, ‘but for conscience sake’, and thus submitted himself wholly to the examiners, declaring that he was willing to go to prison for his beliefs.Footnote 112

Thomas Havard, another JP and four times mayor of Herefordshire, was also mentioned in Blaxton's will as his ‘dear friend’ next to whom he wished to be buried in Hereford Cathedral.Footnote 113 He too refused to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity in 1569. His will of 1570 leaves no doubt as to his Catholic beliefs – he bequeathed his soul ‘to almightie god his blessed mother saynt Mary and to all her holy company of heaven’, and willed that his body be buried ‘according to the laudable customes of the Catholick Church of Christ’, with prayers ‘for [his] soule and all Christian Soules’.Footnote 114 It seems probable that both Havard's and Scudamore's contact with Blaxton throughout the 1560s contributed, at least in part, to the hardening of their religious beliefs and eventual refusal to attend the services of Protestants.

Whilst the cathedral clergy's attempts to promote recusancy in the north of England were aided by the comparatively large number of deprived clerics operating in the area, as well as the latent conservatism of the northern laity, the north cannot be seen as exceptional in this respect. Although the example of Herefordshire does not alone prove that cathedral clergymen were encouraging nonconformity throughout England (more local studies are required to test this hypothesis), it does at the very least demonstrate that such clerics were able and willing to promote and orchestrate recusancy outside the traditionally conservative north.

III

This article now turns to those cathedral clergymen who were imprisoned following deprivation. At least eleven higher cathedral clerics ended up behind bars over the 1560s, and we might therefore expect their influence to have been severely limited. However, several historians have demonstrated how imprisonment could ‘facilitate rather than confine religious activism’ in England.Footnote 115 Protestantism in particular may have benefited from the incarceration of its leading exponents during the reign of Mary I. As Thomas Freeman has suggested, through the creation, copying, and circulation of letters, treatises, sermons, and prayers within English prisons, Marian Protestants were able to ‘wage a propaganda war against their opponents, stiffen the resistance of their followers to Catholicism [and] maintain intimate pastoral relations with individual Protestant laypeople’.Footnote 116 The cathedral clergymen of Mary's reign, perhaps having learnt from the conduct of their adversaries during the 1550s, seem to have pursued a similar brand of prison evangelism.

Following his arrest, Henry Comberford, the former Lichfield precentor who had been visited by a divine messenger in the early 1560s, was imprisoned in York. From his prison cell in the upper sheriff's Kidcote on Ouse Bridge, he seems to have spread his beliefs amongst his fellow prisoners and, as his fame grew, those outside the prison walls who sought audiences with him. As John Aveling has noted, the confessions of at least two York prisoners suggest the influence of Comberford's teaching.Footnote 117 For example, William Tessimond, imprisoned for recusancy in the Kidcote in November 1572, was a local saddler. The sophistication of the Catholic opinions revealed by his examination belie his low social standing and presumed lack of formal education – he confessed how he disliked the order of service now used since it was ‘not like unto the order of service of the Catholic church and for that sacrifice is not offered in the same for sins of the quick and the dead’. Aveling contended that Tessimond learnt these ideas directly from Comberford.Footnote 118

More concrete evidence of Comberford's influence is the case of John Fletcher, a teacher in York. Fletcher claimed that his conversion to Catholicism was initiated by his reading of certain Catholic books which persuaded him that, having attended heretical church services, ‘I was in damnable state for my dissimulation.’Footnote 119 One of these books was entitled De schismate, a 1573 Latin work by John Young which condemned attendance at church services – a tract which it was once suggested travelled no further than Louvain.Footnote 120 However, his reading had been insufficient to persuade Fletcher to renounce the Protestant services entirely. He continued to conform and dissemble in front of ‘the heretics’ until he was ‘brought home by a godly, grave, and wise Father, Mr Henry Comberforthe, who charged [him] sore that [he] would not forsake [his] fair wife, goodly house, and the great company of [his] comfortable scholars’. Comberford only agreed to reconcile Fletcher once he was persuaded that the former teacher ‘would renounce all these utterly’.Footnote 121 Fletcher was true to his word and by October 1575, had been incarcerated in St Peter's Prison as a recusant where he began disseminating ‘unlawful books’ amongst the prisoners and ‘causing great access to the said place by his doings’.Footnote 122

John Aveling also acknowledged the importance of Comberford for the development of recusancy in York. He attributed to the former precentor no small part in the growth in number of recusants in the city from only fifteen in 1568, to sixty-seven in 1576.Footnote 123 However, Comberford's influence was not confined to the vicinity of the Kidcote. It stretched out beyond the city limits and into the surrounding parishes. Christopher Watson, a wealthy gentleman of Ripon (over twenty miles from the city), explained how a local priest had brought him to York to meet Comberford, ‘who with godly prudence and good deliberation took him by the hand and brought him within the saving Ark of Noah’. This encounter convinced him to spend all his wealth relieving afflicted Catholics, and by 1580 his activities had earned him a place in York Castle where ‘his continual exercise was…to pray, to praise God, and to work the works of mercy’.Footnote 124

Comberford also seems to have made a significant impact upon another Yorkshire town, Hull. On 7 January 1576, the York high commission, recognizing that ‘he (by fame) hath seduced divers…causing them by his persuasion to be disobedient in coming to the church’, commanded him ‘to cease from such seducing and to be quiet’.Footnote 125 Finding him ‘utterly disobedient’, they moved him out of the prison at York and into the closer confinement of Hull Blockhouse.Footnote 126 It seems that he began at once to develop yet another recusancy network in his new surroundings, despite the harsher conditions of the Blockhouse.Footnote 127 Archbishop Sandys wrote to the privy council on 28 October 1577, decrying the many ‘stiffe necked, wilful’, and ‘obstinate’ people of his diocese who were ‘reconciled to Rome and sworne to the pope’. It is unknown whether the former treasurer had been granted such faculties for reconciliation, but it was certainly Sandys's belief that ‘the moste of them have ben corrupted by on Henry Comberforde, a moste obstinate popishe prieste’.Footnote 128 Sandys wrote again to Burghley in April 1578, explaining apprehensively how ‘[t]he obstinate which refuse to come to churche, whereof the most parte are women, neither canne I by persuasion nor correction bringe them to any conformitie. They depende uppon Comberford and the rest in the Castle at Hull.’Footnote 129 The case of Comberford clearly demonstrates how an individual cathedral clergyman could become a key promoter of nonconformity across a wide area, even when their actions were restricted by imprisonment. The following examples focus on a group of prominent cathedral clergymen incarcerated in London prisons throughout the early decades of Elizabeth's reign. It is clear that these priests were just as capable of promoting lay recusancy from their cells as Comberford was in the north.

Former dean and abbot, John Feckenham, was imprisoned in the Tower on 20 May 1560. Between this date and his removal to the custody of Dean Gabriel Goodman in 1563, he composed one of the clearest justifications for recusancy of Elizabeth's reign.Footnote 130 Feckenham's Certaine considerations and causes, movying me not to bee presente at, nor to receive, neither use the service of the new booke, otherwise called the common boke of praiers, dated 8 February 1563, was circulated in the form of ‘a certain small pamphlette’ amongst his friends at court.Footnote 131 Whilst its readership may therefore have been initially quite limited, it was eventually published in 1570 in the form of a rebuttal made by William Fulke.Footnote 132 Drawing upon ‘the Canons of the apostles, and…the generall caunselles also’, Feckenham argued that ‘a christian man shoulde not communicate in Sacramentes nor yet in common praiers, with Heritikes and Schismatikes’, since, in doing so, ‘they shoulde breake the unitie of Gods spirite, whiche is the chief treasure in his Churche, commended by our saviour Christe unto his Apostles, wishynge and praiynge the same unitie to be amongest theim, whiche was beetwixt him and God the father’.Footnote 133 The former abbot condemned the notion of Catholics conforming with a false church. Such an act was ‘not onely contrarie to [his] owne conscience and also to [his] damnable sinne, but also…to the weak and ignorant an occassion of ruyne and deadly sinne’. By setting a bad example, they would have inaugurated a rift in the church.Footnote 134 Such a rift could come about from divergence over even the smallest of matters; Feckenham quoted Tertullian's tale of a soldier who refused ‘to weare but a Garlande of flowers upon his head, because he should therin then have followed the maner of the gentiles, and heathen people’. The only lawful course of action regarding this ‘matter of greate importance’ was thus plain to see.Footnote 135

Five Marian cathedral clergymen spent at least part of the 1560s imprisoned in the Fleet, including Dean Henry Cole, Dean John Harpsfield, Archdeacon Nicholas Harpsfield, and Archdeacon William Chedsey. The impact these individuals made upon recusancy in the capital is difficult to assess; however, they certainly seem to have been a concern to the authorities. In July 1562, the deputy warden of the Fleet was called in front of the privy council and instructed that Cole, the Harpsfield brothers, and several others, were ‘to be kept in closse prisonment so as they may not have conference with anye, nor be suffred to have suche resorte unto them as they have ben accustomed’.Footnote 136 Ten years later, in a letter written to the bishop of Ely in March 1572, the privy council discussed the possibility of moving religious prisoners out of the capital in the hope of stopping their ‘craftie intelligences with other prysoners’ and their ‘practyses abrode to corrupt others in stobbernes’.Footnote 137

These cathedral clergymen, despite close imprisonment, retained contact with the outside world. The commonplace book of John Harpsfield, imprisoned in the Fleet from 1559 until at least 1574, demonstrates how the former dean retained remarkable connections with his co-religionists abroad, and kept abreast of developments within the continental Catholic church. In an entry dated 14 February 1573, he had copied out excerpts from several works by Jodocus Ravesteyn.Footnote 138 Ravesteyn had been involved in the 1551 session of the Council of Trent and was a staunch defender of Tridentine orthodoxies in print. He spent much of the 1560s producing various tracts on core Catholic doctrine at the University of Louvain.Footnote 139 Since one of the works quoted by Harpsfield was only published after 1568, it is clear he was in contact with the university during his imprisonment.Footnote 140

Once these individuals grew older, many achieved varying degrees of liberty. For example, John Harpsfield and his brother were released to live under close surveillance in 1575.Footnote 141 John Feckenham was granted permission to travel to Bath for the waters in the same year ‘for his good behaviour’.Footnote 142 However, it seems that age had not dampened their desire to spread the message of recusancy. In June 1577, the privy council was informed that Bishop Watson, Feckenham, and other ‘late prisoners for matters of Religion’ had used their newfound liberty to make contact with certain ‘evil disposed subjectes’ whom they had ‘perverted in Religion’.Footnote 143 Later that same year, Francis Walsingham wrote how he was unsure what to do with the likes of ‘Watson, Fecknam, Harpesfielde, and others of that kinde, that are thought to be the leaders and the pillers of the consciences of great numbers of such’ who ‘obstinately refuse to come to the church in the tyme of sermons and common praiers’. He contemplated banishing them from the realm in order to prevent any further corruption by their hands.Footnote 144

IV

It would appear that, despite deprivation, the Marian cathedral clergy retained the uncompromising and ardent faith which they had developed during Mary's reign – a faith which translated into an unbending conviction that any conformity with the Church of England was damnable. These clergymen were in frequent and sustained contact with one another across wide areas, and promoted the common cause of recusancy throughout the 1560s and early 1570s through a number of imaginative strategies, ranging from oath-giving and exorcism, to prison preaching and the production of printed catechisms. In short, long before the first seminary-trained and Jesuit missionaries, they had initiated what can legitimately be described as a ‘campaign’ for nonconformity.

Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that only towards the end of the 1570s did something we might call an English ‘ideology of recusancy’ start to emerge. Beginning with Gregory Martin, an Oxford professor turned seminary priest trainer, who published his Treatise of schisme in 1578, the debate over the legitimacy of nonconformity with the Church of England grew, reaching its high point at the so-called ‘Synod of Southwark’ in 1580.Footnote 145 This clandestine meeting of secular clergy and the recently arrived Jesuits Robert Persons and Edmund Campion concluded firmly that attendance at Protestant services was unacceptable for true Catholics. The resultant flood of polemical tracts helped develop a comprehensive set of historical and biblical justifications for nonconformity.Footnote 146

However, several cathedral clergymen had already begun to justify their recusancy in such intellectual terms long before the seminarists and Jesuits became involved. John Morren, Laurence Vaux, and John Feckenham were each attempting to provide scriptural and canonical precedents for their nonconformity from as early as 1561. In these efforts, they were aided by the final group of cathedral clergymen with whom this article deals, those who fled abroad following deprivation. The majority of these men eventually settled in the University of Louvain where they published a series of polemical tracts in response to Bishop John Jewel's well-known ‘Challenge Sermon’.Footnote 147 As Karl Gunther has recently suggested, the tracts of these ‘Louvainists’ were both ‘widely distributed and widely read in England during the 1560s’.Footnote 148 References to their books are rife in the examinations of suspected Catholics throughout this decade. For example, in February 1569, following a search of historian John Stow's London house, several Louvainist books were discovered, including former chancellor of Salisbury Thomas Heskyn's A parliament of Christe and Chichester prebendary Thomas Stapleton's The fortresse of the faith.Footnote 149 Similar works also found their ways into the libraries of numerous Oxford and Cambridge scholars, whilst Protestant theologians were increasingly uneasy about the ‘havocke of bookes’ entering the realm.Footnote 150 The activities of these Louvainists should not be seen as separate from the efforts of their counterparts in England, but rather as the intellectual arm of the same campaign to promote nonconformity.

In 1565, Thomas Stapleton (prebendary of Woodhorn, Chichester, 1559–63) published his polemical work The fortresse of the faith. As well as explicitly demonstrating how Catholics should ‘in no wise communicat with the heretik’, this tract beseeched its readers, ‘for no worldly respect or interest’, to ‘put in hazard the losse of so precious a jewell [as their true Catholic faith], by flattering with the world, by yelding to the time, by false persuasion of worldly wisedom’.Footnote 151 Stapleton went on to provide examples of ‘notable personages, touching their constancy in profesion of their faithe, when…a bitter blast of adversite forced them to utter their conscience’.Footnote 152 Stapleton recounted the story of Saturus, a high steward to the prince of the Arians. Saturus was condemned for his Catholic beliefs to lose his livelihood, house, goods, and lands, and have his children sold into slavery, unless he obeyed the king's proceedings with regards to religion. Despite being implored by his wife to ‘[y]elde unto the time and present state’ in the knowledge that ‘oure Lorde knoweth you do it againste your will and constrained thereto’, the former steward remained constant in his faith.Footnote 153 There can be little doubt that, in Stapleton's eyes, a Catholic who was willing to dissemble his beliefs by attending heretical services risked eternal damnation; in a tone strikingly similar to Laurence Vaux's Catechisme, he declared that ‘undoubtedly without the confession of our faith when such is required, no salvation can be hoped for’.Footnote 154

Similar opinions can be found in former Salisbury chancellor Thomas Heskyns's 1566 A parliament of Christe. Quoting St John Damascene, this former chancellor of Salisbury warned that we should ‘beware with all diligence that we do not communicate with heretiques’. By appearing ‘to consent to their wicked heresie’, Heskyns believed that one effectively ‘entre[d] into felowshippe with Devells’, thereby rupturing the unity of the one true faith.Footnote 155 Just like Feckenham and Vaux, Heskyns argued that there was to be no dissembling over this issue: ‘ther ys no dallieng in Gods matters’.Footnote 156 He also went further, questioning whether we should ‘withdrawe our selves from them, which do not onelie walke inordinately but do with all that in them lieth laboure to subvert the wholl order of Chrystes Churche’. Generalizing the advice of St Paul, he concluded ‘withoute doubte, that we should have no felowshippe, nor medle with them, and speciallie [but not exclusively] in the communion of sacramentes’.Footnote 157 Heskyns clearly saw any association with Protestants as damnable.

However, perhaps the clearest declaration in favour of nonconformity can be found in the work of Nicholas Sander. Although himself not a cathedral clergyman, Sander had nonetheless worked closely alongside several cathedral clerics whilst studying at Oxford during Mary's reign and subsequently in Louvain (including that prominent agitator for Lancashire recusancy, Laurence Vaux). In the preface to his 1567 Treatise of the images of Christ, Sander stated that, although there was ‘a rumour spread by certain men, that this going to schismatical Service is, or may be wincked at, or dispensed in the Catholikes, of certaintie it is not so’.Footnote 158 The former Oxford scholar made it clear that attendance at the services of Protestants was effectively an endorsement of the heresies contained therein and a denial of the Catholic faith.Footnote 159 He condemned those who, ‘for feare of a small temporal losse’ would ‘put in hasard their everlasting salvation’.Footnote 160 In a tone similar to Feckenham, Vaux, Morren, and Heskyns, Sander plainly confirmed his belief that ‘if ever the faith shalbe recovered, it must be don by confessing and professing it, and not by dissembling’. This requirement, he argued, was proved by ‘the Canon of the Apostles, and the Councel of Laodicea…and the example of the Primitive Churche’.Footnote 161 Thus, although more explicit about the implications of his beliefs, Sander's message was no different from that of the other cathedral clergymen – it was the duty of all Catholics openly to proclaim their faith, an action which was incompatible with conformity.

V

All fairy tales eventually lose their magic, even if it takes 400 years. The evidence presented above suggests that the prevailing narrative of early Elizabethan recusancy – a narrative still largely based upon a ‘fairy story’ told by Robert Persons in 1600 – is in need of significant revision.

This article has put forward the case that the cathedral clergymen of Mary's reign deserve a prominent place in the history of Elizabethan recusancy. Under Mary, these clerics had become the fiercest proponents of a vigorous and energetic faith which combined the militant enforcement of a newly clarified Catholic doctrine with the readiness to appropriate and develop the reforming experiments of Protestants and Catholics throughout Europe. Their upbringing within such a church provided these clerics with the determination and skills with which to launch a co-ordinated, country-wide campaign in favour of principled nonconformity following Elizabeth's accession. Not only did this campaign imitate tactics pioneered by Protestants during Mary's reign, and continental Catholics such as Peter Canisius, but it also anticipated many strategies and ideas of the later English mission. From developing cutting-edge evangelical techniques to forming large and interconnected networks of priests, these cathedral clergymen set precedents later developed by the seminarians and Jesuits after 1574. Most significantly, long before Gregory Martin wrote his Treatise of schisme, the Marian cathedral clergy were developing and propagating their own scripturally and historically justified ideology of recusancy.

Such a conclusion raises several important questions for the study of early Elizabethan Catholicism. Principally, it suggests that there may have been more recusants in the 1560s and early 1570s than previously acknowledged. Historians have depended largely upon official reports in order to substantiate their claims that recusancy was not a feature of these early decades – the diocesan survey of 1577 identified fewer than 1,600 individuals across England and Wales.Footnote 162 However, these statistics cannot be taken at face value. A shortage of well-educated ecclesiastical administrators, the lack of any real impetus to find nonconformists, and the reluctance of churchwardens to report on their neighbours may all have contributed towards a dearth of recusancy in the records.Footnote 163 Moreover, as Christopher Haigh once ‘tentative[ly]’ suggested, rather than a real rise in numbers, the increase in detected recusants around 1580 might simply reflect a more concerted attempt to discover them.Footnote 164 The papal excommunication of Elizabeth in 1570, the arrival of seminary priests in 1574, and the Jesuits in 1580, as well as mounting tensions with Spain, all served to heighten the perceived threat posed to England from Catholicism.Footnote 165 This growing concern may well have inspired the government and its agents to ‘crack down’ on recusants who, having been encouraged by the cathedral clerics and their disciples, had been quietly dissenting since the beginning of Elizabeth's reign.

Such a suggestion highlights another area for further research – the mechanics of nonconformity. The evidence above implies that the laity required, or at least were heavily reliant upon, the clergy in order to push them towards recusancy. Such an idea is, perhaps, yet another legacy of Persons. The influential Jesuit certainly believed that, without proper clerical guidance, the laity were bound to slide into conformity.Footnote 166 A deeper and more nuanced understanding as to how laypeople made the move into recusancy, and how they were sustained thereafter, is very much needed if we are ever to gauge accurately the importance of the clergy for the English Catholic community under the cross.Footnote 167

Finally, it is interesting to note how the apparent uniformity of message and purpose exhibited by the cathedral clerics in the early decades of Elizabeth's reign is in stark contrast with the later Appellant controversy. After 1580, former cathedral clerics such as Archdeacon Alban Langdale, and even that early champion of recusancy, John Morren, began to advocate a degree of conformity with the Church of England, suggesting that, whilst absolute recusancy was still the ‘councel of higher perfection’, attendance (without communion) at Protestant services might be permissible – a stance which brought them into conflict with the newly arrived Jesuits.Footnote 168 Whilst some members of the laity and parochial clergy may have been advocating such a compromise earlier on in Elizabeth's reign, such opinions, as this article demonstrates, represent a definite change of heart for the cathedral clergy.Footnote 169 Why and how this came about demands further research, particularly since it coincides exactly with the arrival of the Jesuits in England. Perhaps these cathedral clerics realized that pushing the laity too hard at a time when recusancy charges were increasing would have been counter-productive, something which the newly arrived Jesuits, out of touch with the feelings of the average English layperson, were unable or unwilling to acknowledge?

To conclude, if we accept the now-substantial evidence that the church of Mary I was very much a part of the continental movement for Catholic reform, we can no longer ignore the presence of its priests in Elizabethan England. If Mary, her cardinal, and leading clergymen ‘invented the Counter-Reformation’, as Eamon Duffy has proposed, then there is much to suggest that they also invented recusancy.