RM: I think, first, we’re doing K-pop, right? And K-pop is a great mix of music, music videos and performance, choreographies, and social media and real life contents. So, I think, when you get into our music, for example, you search YouTube and you can search, you can look for our chemistry and the, like, contents, and they and you could look for the, like, social medias. And so, it’s like really easy for them to, like, get to us, so, I think, that’s why K-pop is popular. And, for us, I think we’re talking about, uh, we write and produce our music ourselves, and we’re talking about the young people, young people’s lives, like, every day, like, us, like you. So, uh, I think there is a specific contemporary characteristic for the young, between all the young people in the world. And, thanks to our fans, they translate our lyrics and our interviews into their languages, and that’s how they could resonate and feel the same feelings with us. And that’s why they pay attention to us. And the performances, of course.

In a December 2017 web interview with iHeartRadio.com, the leader of the K-pop idol group BTS, Kim Namjoon (RM, also known then as Rap Monster), defined K-pop as “a great mix of music, music videos and performance, choreographies, and social media and real-life contents.” I emphasize the phrase “real-life contents” because it highlights the equivocation between “real life” and “contents” that I argue is at the heart of K-pop’s appeal and the media practices of fan comportment that are the focus of this chapter. Further in his comment, RM encapsulates the impacts of K-pop’s transmedia modalities (music, video, performance, social media) and fans’ participatory responses (content translation and sharing): They allow fans to “feel the same feelings with us.”

This chapter analyzes fan and idol participation in the video ecosystem of K-pop fandom in order to argue that the ideal of co-feeling, “feel[ing] the same feelings” with K-pop idols and with other fans, produces unique and emergent media forms characterized by vicarity, seriality, and surplus enjoyment. These vicarious media – or media intent on producing vicarious experiences – rely on structures of visual identification as well as the ability of twenty-first-century media platforms to transform acts of consumption into spectacles in their own right. Fan acts of identifying with and consuming K-pop idol celebrity and youth culture take multiple forms, ranging from K-pop dance covers to meokbang (broadcast-eating videos) to reaction videos (fan-recorded reactions to K-pop content), all of which illustrate RM’s claim that the relay of vicarious experience binds K-pop idols to their fans and fans to each other, in the process producing ever more “real-life contents.” I argue that vicarity relies on the ubiquitous reflexivity that defines social media platforms as sites of subject formation via media production and consumption. While the term “metamedia” has historically referred to computing mechanisms by which digital media remediate older media forms, I argue that the habitual use of digital media necessarily produces metaconscious awareness of metamediation; social media participation constitutes an immersive, everyday form of metamedia as a prompt for reflexivity, by which vicarious substitution through video induces intense affective experiences of identification.

Moreover, vicarious media seem to suggest a proxy for politics as an expression of collective sentiment – the ways media platforms bridge the private and the public through the antinomies of the social. Traditional modes of political organizing, which until recently seemed foreign to a fan habitus, are newly central to the activities of fan collectives since the youth-led uprisings in Chile (2019) and the United States (2020). My goal is therefore to articulate how K-pop fandom exemplifies contradictory impulses for intense individuation – for example, social media platforms’ structures of monetizable recognition – and the corresponding longing for utopian community and collective agency that we see across multiple nodes of media consumption.

The Participatory Condition

In the 2016 edited collection The Participatory Condition in the Digital Age, volume editors Darin Barney, Gabriella Coleman, Christine Ross, Jonathan Sterne, and Tamar Tembeck argue that digital media in Western liberal democratic societies have generalized participation from mere “relational possibility” to a requirement of contemporary cultural life and practices of selfhood.2 In their words, “The participatory condition names the situation in which participation – being involved in doing something and taking part in something with others – has become both environmental (a state of affairs) and normative (a binding principle of right action)” (i). According to Barney et al., participation goes beyond specific practices of engagement. Instead, it is the very core of democratic society itself: “fundamentally, [participation] is the promise and expectation that one can be actively involved with others in decision-making processes that affect the evolution of social bonds, communities, systems of knowledge, and organizations, as well as politics and culture” (viii). Here, the authors seem to suggest that the idea of participation is crucial to the act of participation. In other words, the ideology of participation as social contract inheres in every participatory utterance or gesture.

However, the ways digital technologies generalize participation – from the interpellating call of social media platforms to the infrastructures of data collection in which we participate through the mere act of searching for information or streaming music on a smartphone or internet-connected PC – require us to revise this traditional concept, as participation now clearly exceeds the domain of rational discourse in the Habermasian public sphere. Moreover, the authors of the volume use the qualifiers “the West” and “Western” to situate their analyses of the participatory condition, when a “West and rest” binary no longer offers descriptive value in today’s media ecologies. In their view, the impasse of the participatory condition – the fact that media participation is a means of both empowerment and subjection – calls for resistance to the “depoliticization” of digitally mediated participation, again hewing to a narrow understanding of normative participation as the sort in which rational citizen-subjects engage in order to articulate political claims. In what follows, I argue that we must overcome this dualism between properly and normatively political participation and illiberal, excessively passionate and insufficiently reasoned participation. Digitally mediated participatory cultures do not simply sort into the polarized categories of what Jodi Dean calls “communicative capitalism,” on one hand, and politically progressive, anticapitalist, rhizomatic media networks, on the other.3 K-pop media cultures range across these categories and often combine them. Thus, we must think beyond this binary to theorize the full implications of the participatory condition in global media and fan cultures such as those that constitute the transmedia worlds of K-pop. K-pop refuses the abstract generality of “the West” and demands specific historical and geopolitical consideration, as a media phenomenon that operates both in the center (of East Asian culture industries and on corporate-owned platform giants of US provenance) and at the margins (eliciting participation from audiences across the global south).4

Henry Jenkins introduced the framework of participatory cultures of popular media consumption in the influential fan studies work Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Cultures, published in 1992 (notably, a time before widespread internet use). He proposed a division between media consumers and “poachers,” arguing that the latter appropriate and repurpose commercial media in fandom, for the sake of community building through the formation of fan counterpublics.5 This division, in Jenkins’s account, maps onto a common division prevalent in media and communications theory and critiques of mass culture between the passive consumer – trained by mass media formats and technologies to be ever more receptive to the dictates of capitalist cultural industries and their manufacture of desire – and the active audience that uses commercialized culture as textual material to be refashioned for progressive or resistant ends. This triumphalist approach to fan engagement and secondary creation as “participatory” has since been criticized for its one-sided celebration of fan activity and identity, while nevertheless remaining a keystone in the field of Anglophone fan studies.

Jenkins himself issued such a critique of participatory culture and participatory media, or media texts that aim to elicit fan participation, as media texts and franchises began to expand across a rapidly transforming media ecology with the advent of digital distribution. Since the mid-2000s, he and other scholars have continually returned to the problematic of participatory culture, especially as the internet and networked communications shape the collective consciousness of youth. Participatory culture requires a focused media literacy curriculum, in Jenkins’s view, yet subsequent work in fan studies often gets stuck in the now deeply etched groove that connects the poles of celebration and condemnation of the participatory condition of technologically mediated, networked fandom.

Jenkins’s foundational analyses of convergence culture in Euro-American contexts also anticipated the further co-option of fan activity as commodified attention in the platform ecosystem of twenty-first-century media consumption. More recent analyses of social media continue to confront the dilemmas of a thoroughly mediated social arena that seems to confound the distinction between private and public that has been so important to modern political theory. Media scholar and theorist Laikwan Pang has written about the political potential of privatized social media platforms in Hong Kong’s umbrella movement, returning to political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s discussion of the social as the liminal space between the private and public.6 For Arendt, the individual’s desires and needs as an embodied self – the domain of the private economy of the household – must be rigorously excised from the public domain, in contrast to the social, which is constituted by the intermingling of the private and public. The problem, for Arendt, is the steady replacement of the public with the confounding fuzziness of the social, where the projection of the individual’s private concerns clouds extra-individual claims in the properly public realm of the political.7 Studies of the democratic uses of social media and platforms often take as a signal case the counterhegemonic use of Twitter in the Arab Spring to celebrate expressly political activity that appropriated global north technologies for left-populist ends, such as online organizing through hashtag campaigns.8 This scholarship does not often attend to the political potential of platform engagement in fannish modalities – for entertainment, parasocial fantasy and world building, or lateral connectivity among fans.

Gender and sexuality studies scholarship, as well as feminist and queer political discourses, emphatically reject the divisions between public, private, and social, as the second-wave feminist slogan “the personal is political” has become a crucial epistemological orientation for developing knowledge about the ways social categories and identities condition citizenship and subjectivity in numerous contexts. In foundational texts in cultural studies, especially as formulated by the Birmingham School (now often referred to as British Cultural Studies), popular culture is undeniably political in its hegemonic force, as regimes of representation convey social divisions and power relations within society. The primary tenet of cultural studies scholarship throughout the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries is that culture is a system of signs that produces meaning in a contingent manner with nonetheless material effects. Thus, culture is not fixed, essential, or inherent to the materiality of forms, objects, or practices, nor does it conform to categorical distinctions between private/individual and public/collective modes of human experience. Crucial to this understanding of the ways seemingly private experience cannot be thought outside the realm of publicity is the question of race and other forms of visible difference, and the political claims and impositions that such forms produce. Thus, critical race theory extends the insight that all of culture operates as an apparatus of meaning production to the problematic of embodiment, and the ways visible difference undergirds contemporary power relations built on a foundation of colonial semiotics of racial signifiers.

I situate my analysis within the above cultural studies frameworks to extend my conclusions on the specific phenomenon of K-pop beyond the narrow signifying function of ethnicity or national consciousness. The cultural history of K-pop has been discussed elsewhere in this volume; I seek to contribute an analysis of how K-pop’s digital mediation produces a corresponding cultural mediation that is shifting norms through emergent cultural forms in the mediated community of K-pop fandom as microcosm. The signifying function of these new media forms, however, is relational. K-pop’s participatory fan culture has no central locus in any nationally defined signifying system, not even that of contemporary South Korean culture and the role of popular media within it, since K-pop fandom is dispersed, transcultural, and translational. New norms of mediated participation, however, are emerging in the ways that fans attempt to overcome such dispersal by foregrounding the singularity and commonality of their embodied fan experience. The next section specifies these forms of mediation and analyzes the mechanisms by which fan reactivity – a specific type of participation – establishes vicarious experience as a core collective pursuit in K-pop fandom.

Metamedia and Fan Mediation

What I am defining as a “reactive” tendency in K-pop fandom relies on individual fans’ metaconsciousness of the ways platforms and social media networks operate. To discuss the mechanisms of such a reactive impulse and its technological supports, or the medium-specificity of K-pop’s participatory fan culture, I begin by revisiting new media theorist Lev Manovich’s early 2000s discussion of metamedia.9 He writes that “a meta-media object contains both language and metalanguage – both the original media structure (a film, an architectural space, a sound track) and the software tools that allow the user to generate descriptions of, and to change, this structure.” In the context of computing, when analog media are digitized (or when digital media seek to mimic the function or aesthetic of analog media – e.g., digital photographs), they are transformed into metamedia or metadata by their processing by software that enables images, text, or video to be mapped, searched, selected, zoomed into, zoomed out of, filtered, and so on. The transformation of media into metamedia also allows for accessing old media in forms that are now embedded in our quotidian use of digital technology.

Beyond particular software interfaces, metamedia also express a logic that manifests aesthetically. According to Manovich, “the logic of meta-media fits well with other key aesthetic paradigms of today – the remixing of previous cultural forms of a given media (most visible in music, architecture, design, and fashion), and a second type of remixing – that of national cultural traditions now submerged into the medium of globalization.”10 In Manovich’s terms, metamedia echo the logics of remix dispersed across temporal and spatial axes, that is, historical and geographical extension, as a third type: “the remixing of interfaces of various cultural forms and of new software techniques – in short, the remix of culture and computers.”11 To restate Manovich’s argument, then, the cultural logic of pastiche or remix necessarily inflects the aesthetic and operational design of metamedia. A key practical example of the overarching cultural principle of metamedia as remix is hypertext, or the embedding of links to other digital media into online text. Hypertext – the nesting of other media within textual media – is a common technique of intertextuality that is all too familiar in the interactive sphere of social media engagement. It is almost impossible to participate on social media platforms without also referencing, citing, or juxtaposing other mediated communicative utterances or gestures. Social network interfaces are designed to maximize sharing through hyperlinking, through the repost, reblog, and retweet, as well as the like and the filtering capacity of the hashtag. One of the primary aims of fan organization in K-pop fan culture as well as other media fandoms is the skillful use of metamedia to amplify the visibility of one’s favorite artist or celebrity within algorithmic ecosystems.

Political theorist and communications scholar Jodi Dean argues that the thorough integration of visual signs – such as emojis, gifs, and photos – within the structures and practices of participatory media results in a new language of communication irreducible to any of the individuated forms whose combination has quickly become the conventional idiom of the internet: speech, writing, and image. Dean calls this visual-linguistic remix “secondary visuality.”12 Drawing on the concept of secondary orality – “the transmission of spoken language in a print culture” – from cultural and religious historian and literary scholar Walter J. Ong, Dean develops the framework of secondary visuality to theorize the transforming function of visual images into (meta)textual objects in social media and platform communications.13 This capsule communicative genealogy goes from “face-to-face interaction, to print (the written letter, perhaps with photographs included), to voice (telephone), to immediate text (e-mail, SMS), to photo-sharing (Flickr) to social media incorporating writing and photos, to personal communication conducted through combinations of words, photographs, images and short videos (GIFs).”14 In the context of secondary visuality, images lose their singularity in order to become common ideas that mobilize their force as generic concepts through rapid and easy shareability. The common use and expression of generic images – the most “spreadable” – constitute a digital commons.15 “Out of repetition,” Dean asserts, “emerge trends, bubbles and aggregates, common images through which collectivity momentarily shines.”16

For Dean, a forceful example of secondary visuality is the photographic form of the selfie – a radical overturning of the individuated aura of the portrait into a generic face, a “commonface” (playing on the notion of commonplace): “A selfie is a photo of the selfie form, the repetition of a repeated practice.”17 In order to elaborate the above “common-ing,” or making-generic of faces, Dean offers examples from daily life – her use of Facebook, her daughter’s daily SnapChat conversations with friends, and, most pertinent for the discussion of “real-life contents” in K-pop, Dean’s experience of following the British boy band One Direction on Twitter and absorbing the metamediatic reactions (tweets and retweets) of the group’s passionate fandom. Dean explains, “When tweeting their reactions to various One Direction–related happenings … fans would use photos of the band members … to express their feelings. For many fans, words alone could not convey the intensity of their emotions.”18 This describes the curious capacity of the celebrity persona to signify both generality and singularity at the same time. The uptake of images of One Direction members as both substitute emojis and fan avatars illustrates this duality: “One Direction photos communicated the feelings of One Direction fans to each other, to the world, or at least to Twitter.… Funny or clever tweets accumulated thousands of retweets and likes. Sometimes there would only be three or four. The overall effect was of immense flows of feeling streaming off the screen” (emphasis added).19 These three examples “point towards the constant generation and regeneration of a visual commons of circulating images.”20

Surprisingly, Dean, who condemns circulating communicative texts in her theory of communicative capitalism, sees the same mechanisms as a visual commons, most convincingly supported by the case of fandom. Integrating the conceptual tools offered by Manovich and Dean allows us, then, to foreground the everyday experience of metamedia as metatextual awareness and interface design and the potential “common-ing” use of metamediated social connection to expand the sphere of collective activity. Incorporating embodied activities of K-pop fandom, social media’s remix culture builds a visual commons through fandom’s gift economy. RM’s use of the term “real-life contents” straightforwardly and unsentimentally remarks on the way that social media transforms experience into data or metamedia – “real life” rendered by digital media representation and social media interfaces into “contents” or bits of textuality.

“Real-Life Contents”

In the iHeartRadio interview, RM does not elaborate whether “real-life contents” are distinct from or a subcategory of “social medias”; however, it is fair to connect the term to two categories of content production that distinguished BTS from their K-pop peers in their early years: “Bangtan Bombs,” backstage antics captured in short video clips produced and curated by their management company, and “Bangtan Vlogs,” video content of BTS members directly addressing fans in the simulated intimacy of a video chat. Although prior K-pop groups also produced backstage and “making-of” footage, this content was usually distributed as extra features on official concert DVDs. The other customary venue that purports to highlight pop idols’ “real-life” personalities are guest segments on variety shows broadcast on South Korean cable or network television. In contrast, Bangtan Bombs and Bangtan Vlogs have been produced and distributed on the Bangtan TV YouTube channel alongside official music videos, music video teasers and album previews, dance practice/choreography videos, and longer “making-of” or “behind (the scenes)” videos that are labeled “Episodes.” Big Hit Entertainment (now HYBE), the group’s management company, established Bangtan TV in December 2012, before the group’s official debut, suggesting that the company planned to foreground the group’s “real-life contents” as its core marketing strategy from the beginning.

As of February 2021, Bangtan TV had 44.1 million subscribers, 1,403 uploaded videos, and 8,340,701,825 aggregated views. Other platforms that house the ever-expanding archive of BTS-related video content are VLive, the celebrity live-streaming, vlogging app developed by Korean portal giant Naver; Twitter; TikTok; the HYBE-owned fan engagement platform WeVerse; Weibo; Tudou; and Niconico, not to mention nonsanctioned, fan-uploaded content on the aforementioned video-sharing apps as well as Vimeo and Dailymotion.21 Big Hit/HYBE formats BTS’s “real-life contents” to maximize fan participation as secondary creation and media production, from fanfic to fanvids/video edits to reaction videos, dance cover videos, concert vlogs, theory posts/videos, and merch unboxing videos, to offer a nonexhaustive list, to which I will turn in the next section. “Real-life contents” are also structured to maximize parasocial engagement through direct address to fans, which the K-pop industry (as well as other East Asian pop industries including J-pop and C-pop) codifies as “fanservice.”

Parasociality has been theorized from a variety of perspectives in fields as diverse as media/communications, marketing and consumer research, psychology, and human development. First introduced by anthropologist Donald Horton and sociologist R. Richard Wahl in 1956, when television was rapidly popularizing as a mass medium in the United States, parasociality has also been key to conceptualizing celebrity culture.22 What may be unique to Asian pop idol industries’ cultivation of parasocial bonds is the foregrounding of the fan-idol relationship; the K-pop industry specifically invests resources in producing parasocial relationships through the emphasis on “real-life contents.” The category thus reconsiders the agency of the parasocial; rather than such engagement being an effect of media reception, media producers elicit it by design, and providing “real-life contents” is their primary tactic.

As the K-pop industry focuses all the more on cultivating empathetic connection as a basis of community, to what extent is “feeling the same feelings” becoming the only form of connection? And how does feeling recode participation? These questions are crucial for thinking about the effects of digitally mediated community beyond fandoms, since “community” names a bond of common interests based on shared positionality vis-à-vis institutions and modes of subjection. This is the realm of the political, requiring the ability to organize regardless of whether one can imagine the self as the other. The dangers of overemphasizing empathic identification are very clearly taken up in studies of populism as a derangement of social bonds by their substitution with empathetic/sympathetic identification, which is also a form of narcissism – imagining that the other feels exactly the way that you do. But, as RM emphasizes in his interview, the point is to give fans the idea that they can “feel the same feelings as us. And that’s why we’re popular.”

Key to establishing empathic connection and parasocial intimacy as the primary form of participation in mediated fandom community is the capture of ever more diverse forms of liveness. As Jane Feuer argued in her seminal essay, “The Concept of Live TV: Ontology or Ideology,” liveness is not simply a description of the ontology of television as the broadcast of one source to many viewers in temporal synchrony. It is instead an ideology that suffuses the broadcast medium itself, regardless of content.23 Important work by Suk-Young Kim delineates the ways K-pop’s performance culture maintains liveness as its core ideology of fan engagement, despite relying ever more explicitly on media technologies, even in the space of live concert performances. Kim also connects the ideology of K-pop’s liveness to the medium of television by explaining the crucial intermediation of K-pop’s choreographic and emotional labor by South Korean broadcast networks.24

If ideology, as Gramsci alerts us, tries to conceal itself by masquerading as fact, then the ideology of liveness has become the naturalized core of “real-life contents.” In the case of live performance, liveness has undergone a process of conceptual revision as mediated forms supplement or supplant the traditional notion of liveness as designating the spatial convergence of audience and performer in theater and other genres of stage performance.25 Dean’s proposal of the “commonface” offers a useful summary of the paradox of liveness in a “mediated habitus” by capturing the coexistence of the singularity of the individual as connoted by the face as a metonym of the individual’s interior experience and the generality of the common.26 The deindividuating operation of secondary visuality in digital (meta)media nevertheless relies on the specificity of individually felt and transmitted feelings, in a generalized relay of serialized affects and vicarious experience, which I elaborate on in the following section.

Serial Affect and Vicarious Media

I turn now to seriality and vicariousness – the ways forms of collectivity and co-feeling have multiplied as platforms generate liveness beyond temporal synchrony. The form of serial affect that I identify in K-pop fandom is best illustrated by reaction videos, in which individuals record their act of consuming other media, converting their spectatorship itself into spectacle as a genre of “contents.” The reaction video is native to YouTube, and I have written elsewhere on how the genre codifies authenticity by popularizing the capture of, and thus theatricalizing, “spontaneous” affect in media reception – usually the viewing of another video.27 Seriality, in the context of reaction videos’ performance of empathic connection, amplifies the pleasure of spectatorial identification: the more layers of reaction can be captured and transmitted in a video relay, the more the image of others’ pleasure supplements one’s own emotional and affective response. Thus, serial affect refers to both sequential affect in a video series – videos produced in response to other videos – and seriality without linear duration but featuring intertextual simultaneity, in the multiplying levels of co-feeling and re-mediation enclosed by the frame of a single reaction video. To illustrate these two interconnected types of serial affect, I share the following examples.

The first is from a subgenre of reaction video: the reaction video compilation (Figure 12.1). Here, I refer to the video “BTS (방탄소년단) ‘DNA’ Official MV reaction mashup,” posted on September 27, 2017, but this is simply one among many examples.28 Reaction video compilations are videos in which fans edit individual fan reactions to the same work (usually a music video or live performance) into a single video, to produce a new spectacle of aggregate reactivity. “BTS ‘DNA’ Official MV reaction mashup” compiles separately filmed and uploaded reactions to BTS’s music video for their single “DNA” and arranges them as tiles in a single frame, so that the multiple reactors take on the semblance of a mass audience. The compilation preserves each reactor’s recorded sound, so the cacophony of their exclamations amplifies each individual reaction into a crowd response, simulating a concert experience. BTS’s “DNA” music video had been viewed 22.3 million times within twenty-four hours of being uploaded to YouTube on September 18, 2017, so the reaction video mashup also draws significance from the metric culture created by the platform’s built-in quantification tool, to extrapolate the image of mass reaction to this imagined community of millions of viewers. Moreover, the reaction video mashup itself has garnered 1.2 million views as of February 2021; through the view count, YouTube viewers, even those who eschew recording their reactions as secondary content, become participants in the ever-growing “crowd” response, reactivating liveness, no matter how temporally removed they are from the filmed fans’ reactions.

Foreshortening the duration of the individually filmed reaction series, the compilation video amplifies the affective force of the series of video reactions, compressed to the length of the original music video/musical track. By condensing the series into a composite image, the fan author of this compilation creates a new spectacle that visualizes the additive structure of surplus enjoyment. The fan’s enjoyment of the spectacle of the original music video is filtered through the enjoyment expressed and captured in each reaction video, which adds to the original enjoyment; I call this “surplus enjoyment” because the spectacle of the composite reaction, while new, is never complete without the image of the original stimulus – the BTS music video. Therefore, all of the reactions index and extend the music video, rather than supplanting it. Surplus enjoyment is also transformed into surplus value, as the platform extracts the fandom’s collective labor of looking to produce surplus value or profit.29

The second illustration of serial affect in fan video production is somewhat more complex, but its relational dynamics are similar to that of the reaction video mashup. This series refers to the co-feeling of embodied experience of consuming and producing kinesthetic intimacy through K-pop dance cover videos. Here, I present a series of group dance covers solicited by the K-pop management giant SM Entertainment in 2017, when they sponsored a cover dance contest to market their group NCT 127’s music video and single “Cherry Bomb.”30 Such contests are a way of producing the type of serial reaction and surplus enjoyment of serial fan affect employed by several K-pop companies, underscoring the importance of dance to K-pop’s parasocial relations and participatory fan culture. Indeed, capturing on video the kinesthetic intimacies of popular dance is now a staple of pop cultural participation beyond K-pop. For example, this is the impetus behind the many viral dance challenges on TikTok, a microblogging, video-sharing platform that uses the format of very short videos and features a suite of editing tools that allow users to score their own soundtrack. To briefly sketch the video series I present here, the first video features members of the group NCT 127 reacting to selected videos that were submitted for the dance cover contest. This video culminates in the group’s reaction to the contest-winning video by East2West. In the second video, the East2West dancers react to NCT 127’s reaction to their cover, in a relay that aptly demonstrates the seriality of affect that I want to highlight. The streams of co-feeling between idol and fan are grounded in what Karen Wood calls “kinesthetic empathy” – her term for a viewer’s bodily experience or sensation while watching screen dance – which emerges as the primary criterion for judging the excellence of East2West’s performance. The idol stars’ admiration for the cover dance group’s ability to kinesthetically empathize with the idols by accurately reflecting the idol group’s physical comportment in their dance cover becomes a mirror of the fans’ delightful recognition of co-feeling by “playing” the idol in the cover performance. The compression of the idols’ reaction video in East2West’s reaction-to-the-reaction video also exemplifies the production of surplus enjoyment characteristic of K-pop reaction videos.31

East2West was established in 2010 in Montreal, Canada, and has maintained a YouTube channel – East2WestOfficial – since that year, where the group uploads dance cover videos as one of its main activities. East2West also hosts regular K-pop choreography workshops and produces an annual live performance showcase. The group’s members are all nonprofessional dancers. In 2017, a subunit of nine East2West dancers tied for first place in the NCT 127 “Cherry Bomb” Dance Contest hosted by SM Entertainment and 1TheK – a Korean entertainment video content production company whose YouTube channel boasts over 20 million subscribers. As a prize for winning the contest, which was advertised as being judged by the members of the group themselves, 1TheK filmed NCT 127 reacting to the top entries in a video posted to its YouTube channel. In response, the “Cherry Bomb” cover dancers in East2West filmed their own reaction to NCT 127’s reaction, in a video titled “[EAST2WEST] NCT 127 REACTED TO OUR COVER???” I describe both reaction videos and the serial relay of affective response displayed in the videos’ mise-en-abyme visual structure (Figure 12.2).

The NCT 127 reaction video places all members of the group in front of a monitor, presumably playing the videos to which they are reacting. In the video’s mise-en-scene, the video being reacted to is shown in a small window at the bottom of the screen, as is customary for the reaction video genre.32 While the general format follows the conventions of fan-made reaction videos, the video producers also introduce cuts, close-ups of particular members’ reaction shots, and onscreen text of the sort commonly found in Korean variety content (yeneung). As East2West’s cover video begins, the leader of NCT 127 states the name of the group, and the video within the video clearly identifies the cover performance by nationality. As East2West’s performance begins, several members react verbally – “Woah,” “Oh my god!” – as onscreen intertitles in pink lettering echo their expressions. Throughout, NCT 127’s reactions take the form of both nonverbal exclamations and spoken commentary.

Notably, East2West’s winning dance cover is the sole entry featured in the reaction video that swaps the dancers’ gender: The East2West cover is performed by nine women playing the roles of NCT 127, a male idol group. At first, the members of NCT 127 seem focused on this point, commenting on the way that the East2West dancers infuse a feminine energy into the choreography. As their reaction continues, however, the group leader, Taeyong, incredulously remarks that the dancer who is covering his part is dancing very similarly to him – putting the same energy into the dance: “if she dances like that, I know it must be painful. The next day your neck is … [miming a stiff neck].” Later, at the end of the song’s last chorus, where the dancer playing Taeyong does a standing backbend into a seated position, another group member tells Taeyong that he’s given the cover dancer a huge burden in having to master that movement, as members express their amazement: “She’s doing the best because she’s so flexible!” These comments center on vicarious bodily sensation and embodied identification between dancer and idol as the idols take in the novel spectacle of the fans cosplaying them in their dance routine. This contrasts slightly with NCT 127’s comments about the contest submission they react to just prior to East2West’s video. This entry (tied for first place) is by K-boy, a male dance group from Thailand, and what impresses the idols most about their dance cover is how K-boy has painstakingly re-created their music video’s mise-en-scene, with the same videographic elements and extremely accurate costumes – the emphasis is on the care taken to reproduce the “Cherry Bomb” video text. For East2West, on the other hand, the group members focus on the vicarious experience induced by the dance cover video, expressing kinesthetic intimacy with the dancers.

East2West’s filmed reaction to NCT 127’s reaction to their winning video submission assembles the group of dancers in an entirely different guise than they appear in the dance cover. Instead of channeling the charismatic energy of NCT 127 members, the East2West dancers are young, excited fans reacting to their celebrity idols. As the 1TheK video did not have English subtitles at the time of the women’s reaction, they are limited to responding solely to the nonverbal affective cues in NCT’s reaction – the oohs, ahhs, and jaws dropping, which the women then echo in their spectatorial excitement. Interestingly, however, East2West emit the loudest reactions in response to themselves, when the 1TheK video presents full-screen images of the dance cover to emphasize particularly striking parts of the performance. In these moments, the cover dancers express vicarious identification with the idols as spectators who are consuming the content of their dance cover video. These moments of vicarious substitution are intense, though fleeting. The video’s capture and containment of these mobile identifications in the video within the video within the video bring into simultaneous view the amplifying delight of the fan dancers’ co-feeling in their cover performance, refracted through the idols’ experience of kinesthetic empathy, and then compounded again in East2West’s double identification as idol and fan. As Dean writes, “enthusiasm arises out of experience of collective imitation because the collectivity comes into being as collectivity by feeling itself amplified, strengthened … Pleasure accrues through repetition … we see others as they see with us.”33 The reaction to the reaction’s vicarious structure allows the accumulation of experiences of substitution; the fan feels a collective fan delight over the spectacle of the idols while also accessing the idol’s affect, which the reaction video makes available. Hence the fan is doubly delighted by the idol’s recognition of the fan’s delight.

Conclusion

My goal in this chapter has been to articulate how K-pop fandom exemplifies the contradictory impulses for intense individuation – for example, social media platforms’ structures of monetizable recognition – and the corresponding longing for utopian community and collective agency that we see across multiple nodes of media consumption. Serial affect and vicarious media are key frameworks for understanding how these impulses are negotiated in the networked, metamediatic spaces of fan-idol parasocial engagement. In the video examples, which feature the visual common-ing of fan reactions, the genre conventions of the reaction video blur the boundary between self and other in a serial affective relay. This relay or series has no formal conclusion, but can be imagined repeating and amplifying forever in the streams of feeling that reverberate through K-pop fandom’s digital platform ecosystem. Vicarious experience is a way of resisting the alienating impacts of surveillance capitalism and platforms’ attention economies, whose capacities have always been latent in digital media’s metamediatic operations. K-pop’s ancillary fan videosphere produces forms of microcelebrity like that of East2West – they are widely known among K-pop fans through their YouTube channel (with over 1.5 million subscribers). But at the same time their gestures are not only their own but also a form of kinesthetic mediation. Their bodies become platforms that express the choreographed movements, pleasure, and excitement that fans share as collective embodied intimacy.

To return to the question of the participatory condition, we might now ask, What sort of participation is this? Fan mediation has geopolitical dimensions – the dance cover contestants identifying by nationality, for instance – and reflects the unevenness of K-pop’s reliance on media infrastructures. Without access to media equipment, studio space, time/leisure to learn the choreography, and social media savvy, fans cannot elevate their fandom to the level of platform visibility. But there is also an investment in a dispossessive individualism in these fan responses, a delight in the other’s delight that characterizes fandom’s participatory condition. Identities are mobile and ever-changing in fandom’s gift economy. As a global phenomenon, K-pop and its uniquely mediated practices, as well as its symbolic significance as a non-Western popular culture produced by a “middle power” (in international relations parlance) punching well above its weight in the cultural sphere, call for serious consideration, beyond the framework of national culture as a subfield of area studies knowledge production. K-pop’s media matrix offers many new directions for research about media, transnational fandom (or imaginations of transnationalism), and imagined communities beyond national and linguistic borders.

K-pop fandom models reactivity as the operative form of participation as social behavior – the act of responding to a prompt to create a relay of reactions that constitute collective identity. In terms of civic participation, there are also usually prompts for the subject’s participatory reaction. This goes far beyond interpellation as the subject’s reaction to the hailing call of the law, but could give us a new way of thinking about participation as primarily spurred by lateral relations. Rather than defining participation as “taking part” in or “being part” of the social body as determined by hierarchical social organization, K-pop’s participatory condition allows us to think about the way that normative horizons emerge in relation to collective identities based on shared delight. However, this is not to assert that fan-inflected participation – the forms and conventions of new media forms that aim at vicarious experience as the basis for community bonds – constitutes a utopian space of collectivity. Although these media forms often aspire to a kind of universalism to transcend the political limitations of cultural and linguistic particularity and subordinate identity positions and focus on ostensibly acultural elements of bodily sensation and sensory motor impulses or reflexes, the videos cannot but emphasize fandom as a practice of self-making – identity formation through embodiment and mediated self-representation. The significance of these practices depends entirely on context, for example, in the phenomenon of Kazakh fandom of K-pop promoting nonnormative gender representation in post-Soviet Eastern Europe, or of Chilean K-pop fans coming together as youth who are often dismissed by the political establishment. In the case of East2West, K-pop cover dance allows a group of young people, who are mostly members of visible minority groups, to take up space in public in a context in which the dance and theater communities are predominantly white and display documented bias against minority interests. These are just some of the many areas of much-needed future research in fan, media, platform, and performance studies, spurred by K-pop’s vicarious media.

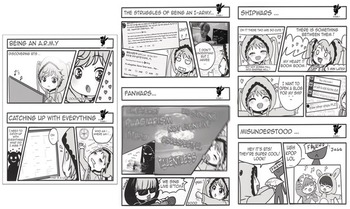

Within a webcomic published in early 2018 (Figure 13.1), a passionate fan of Korean boy band BTS who identifies online as Myra (@MyraKM9597) charts the process by which she came to identify as a member of ARMY, the BTS fandom group. Beginning with her enraptured discovery of BTS, continuing with her learning to be part of ARMY through engaging with the band’s social media, and ending with a rebuffed attempt to convert her friend into a supporter of the global superstars, Myra’s webcomic depicts a narrative that would be easily recognizable to most K-pop fans.1 From exploring the struggles of international fans who lack Korean-language proficiency to strong feelings of wonderment and attraction to the handsome and talented members of BTS, Myra’s webcomic also dramatizes the pleasures and pains central to the fandom culture that has emerged around K-pop idols both within and without South Korea. But one section is particularly interesting. In the fifth portion, entitled “Shipwars,” Myra explores an aspect of K-pop fandom called “shipping” that may seem somewhat confusing to outside observers but is integral to the celebration and consumption of K-pop idol culture. In this artistic retelling of her journey, Myra explores how her strong attraction toward how two of the boy band’s members interact produced an immense affective response that led her to begin “a blog for her ship.” Via the narrative she creates within this comic, Myra argues that the phenomenon termed “shipping” is integral not only to becoming part of ARMY but also to becoming a K-pop fan.

Known variously as “coupling” in South Korea (keoppeuling) and Japan (kappuringu) and “slash,” “real person shipping,” or simply “shipping” in Anglophone contexts, the practice to which Myra alludes is the fannish celebration of the relationship – the word from which the term “shipping” derives – between two members of a K-pop idol group. More than just referring to the celebration of idols’ real-world friendships, however, the terms “coupling” and “shipping” are more commonly utilized by K-pop fans to refer to the practice of imagining the members of their favorite bands in romantic or sexual relationships.2 As idol shippers, fans like Myra create visual art such as comics or illustrations and write fan fiction in which they explore the erotic potentials of imaginary same-sex idol relationships.3 Indeed, shipping practices that reimagine the members of popular K-pop boy groups such as H.O.T., TVXQ, and BTS within romantic or homoerotic relationships are especially common among both heterosexual female fans and fans from queer communities.4 As Myra’s webcomic suggests, shipping is a common practice within K-pop fandom culture. Ultimately, it is a social practice whereby fans deploy homoerotic imaginaries, or what theorist Jungmin Kwon terms “gay FANtasy,”5 not only to explore their sexual desires for the attractive idols but also to express the intensely affective experience of fandom itself.

In this chapter, I explore the homoerotic practice of shipping idols as a lens into the broader study of gender and sexuality in relation to K-pop, demonstrating the importance of fans’ sexual desires to fandom culture. I draw on ethnographic research into K-pop fandom in Australia, Japan, and the Philippines that I conducted between 2015 and 2020 to theorize the role queer sexuality plays within fandom culture. These three countries represent under-researched contexts for the reception of transnational K-pop, and my hypothesis was that the significant cultural differences among them would strongly influence shipping, allowing for interesting contrastive analysis. I pay especially careful attention to how societal norms influence both fans’ shipping practices and their understandings of shipping itself. In focusing on queer sexuality, I go beyond a simple exploration of sexual orientation and deploy queer as a radical hermeneutic focused on “whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant” to account for sexual desires and practices that foundationally challenge the societal status quo.6 Although the desires and beliefs of fans from queer communities form an important part of the analysis, my main focus in this chapter is to explicate how the sexual desires evoked through shipping challenge and subvert both patriarchy and heteronormativity within the myriad cultural contexts in which K-pop fans are embedded around the globe.

I begin by charting the emergence of shipping practices within South Korean fandom, exploring how K-pop production companies strategically encourage young women to consume K-pop through shipping, thus producing spaces within the patriarchal society where women’s sexual desires can be safely explored. The chapter then turns to an analysis of international shipping practices, presenting a comparative case study of BTS shipping within Japanese and Anglophone (Australian and the Philippines) fandom spaces. While BTS shipping in Japan tends to draw on rigid logics that conceptualize homoerotic relationships between men via sexual practices and behaviors divorced from identity, Anglophone shipping tends to instead overtly deploy LGBTQ identity politics to make sense of fantasy relationships between band members. Nevertheless, I argue that both practices possess queer potentials that allow fans to affectively explore their sexuality, affirming their sexual desires for K-pop idols. This process, I suggest, is particularly important for fans from queer communities seeking visibility within the global K-pop fan community.

The Emergence of Idol Shipping in South Korea: A Queer Feminist Practice

The practice of imagining idols within homoerotic pairings developed together with the broader emergence of K-pop and idol culture in the early 1990s as South Korea’s entertainment industries underwent reforms tied to the democratization of society and the concomitant liberalization of the Korean popular culture landscape.7 That is to say, from the very genesis of K-pop, shipping was central to the development of fandom culture. Kwon identifies the emergence of idol shipping in the 1990s as part of a broader social phenomenon where young heterosexual female consumers became increasingly interested in “gay FANtasy,” a term Kwon coined to denote “female fans’ interest in and desire for gay male erotic relationships” and “the subjectivity and cultural power of these enthusiastic media consumers.”8 Other examples of this influential culture include South Korean young women’s investment in Japanese Boys Love manga comics – a genre I discuss further in the following section which is also sometimes called yaoi – and gay-themed American sitcoms such as Will and Grace.9 As these further examples make clear, South Korean young women’s interest in male homoeroticism emerged in the 1990s partly as a result of the gradual removal of the nationalist protectionism that had typified the postwar South Korean media landscape until the late 1980s.

The historical emergence of idol shipping thus owes much to the ideology of globalization known as segyehwa and resultant policies aimed at structurally reforming the Korean economy implemented by the administration of President Kim Young-sam (Gim Yeongsam). As Suk-Young Kim highlights, despite the economic failure of these structural reforms, segyehwa was ideologically instrumental in the historical development of K-pop, particularly through policies lifting the ban on the importation of Japanese cultural products.10 This opening up to Japan played a crucial role in introducing South Korean women to the pleasures inherent to shipping. Almost at the same time as entertainment companies began producing idol boy bands in the 1990s, a fandom for the homoerotic Boys Love manga of Japan exploded among young women in South Korea.11 Thus, as these young women were enthusiastically supporting and discussing the handsome idols from the so-called first generation of K-pop bands such as H.O.T., Sechs Kies, and Shinhwa on online forums, they were also enthusiastically consuming the fan-translated Boys Love manga from Japan that were available on these sites.12 Unsurprisingly, these two fandoms merged as young women began to ship handsome male idols from their favorite bands together, imagining them in romantic or sexual relationships similar to those depicted on the pages of translated homoerotic manga as a way to express both their fannish devotion and their sexual desires.13

The literacies from these Boys Love manga, which I introduce more fully below, strongly affected the ways that young female consumers learned to “read” interactions between the handsome idols central to K-pop’s emerging performance norms in the 1990s and thus educated K-pop fans about the affective and erotic potentials of male-male intimacy.14 Within the heteronormative social context of South Korea, where expressions of same-sex desire are socially censured, the importation of Japanese popular culture queered young women’s viewing habits, introducing a queer gaze that celebrated radical sexual expression and continues to challenge the conservative gender ideologies of the society. But shipping also represents a queer transformative practice in other important ways. South Korea’s patriarchal society has traditionally denied women the ability to express their sexual desires actively, instead positioning them as objects upon which the desires of heterosexual men are enacted.15 For Kwon, shipping represents a radical feminist act since its explicit facilitation of women’s exploration of their attraction to handsome male idols provides young female fans the sexual agency to express their desires within a social context where such expression is often routinely silenced.16 Thus shipping centers women’s sexual desires at the heart of K-pop fandom culture.

As businesses chiefly targeting young female consumers, K-pop production companies strategically manage the star personae of their idols. Historically, this has meant implementing dating bans and controlling media reporting through their considerable economic clout to ensure that idols remain unattached and thus potentially available as objects of romantic investment to their fans. As the K-pop industry matured, Kwon argues, shipping was co-opted into the developmental logics of South Korea’s idol culture as a safe way for female fans to consume media about their idols without compromising this theoretical availability.17 K-pop production companies now explicitly support shipping practices, such as when SM Entertainment invited fans of their megagroup TVXQ to participate in an officially sanctioned fanfic contest focused on imagining members of the band in romantic relationships (sexually explicit fictions were, however, strictly banned).18 In strategically deploying shipping in their marketing and production practices, Korea’s popular culture industries have expanded and diversified their markets by absorbing what was once an underground subculture into the mainstream.19 It has become routine for K-pop idols to perform “fan service,” often involving “skinship” and other acts of “performed intimacy” that passionate fans subsequently draw on in the production of fan fiction and fan art.20 In so doing, K-pop production companies are borrowing already well-established fan service practices from the Japanese idol industry (most notably from Johnny’s and Associates, the largest producer of boy bands in Japan).21 Further, as a result of the cultural influence of K-pop idol shipping, in recent years companies have created “bromance films” wherein handsome idol actors perform “intimate but not sexual” relationships designed to attract young female fans of gay FANtasy while not alienating more conservative audiences.22

The above historical narrative reveals that shipping is primarily practiced by female fans of male idols, the chief market in South Korea for K-pop. But emerging research by anthropologist Layoung Shin reveals that shipping also initially informed the practices of same-sex-desiring female fans active within the “fancos” (fan costuming) community. Many lesbian-identified K-pop fans would enjoy cross-dressing as their favorite male idols in the 1990s not only to celebrate their fandom but also to express their own sexual attraction to members of the same sex through the strategic embodied performance of shipping through costume play.23 Kwon’s interviews with gay Korean men show that many view gay FANtasy culture such as idol shipping positively, recognizing its potential to shift public attitudes toward homosexuality in positive directions, although none of Kwon’s gay interlocutors actively participated in such practices.24 There is a dearth in research into queer fans of K-pop within South Korea itself, but, as my research in Australia and the Philippines reveals, idol shipping has become increasingly popular among queer communities around the globe. It is thus likely that shipping is practiced by queer fans in contemporary South Korea.

Shipping BTS in Japan: The Influence of Boys Love Manga

In the early 2000s, a passionate Japanese fandom for Korean popular culture developed; anthropologist Millie Creighton identified the ratings success of Winter Sonata (Gyeoul Yeonga) in 2004 and the subsequent domination of Japan’s pop music charts by South Korean superstars BoA and TVXQ as catalysts for the Korean Wave in Japan.25 By the mid-2010s, Japanese fandom for Korean popular culture had become embedded within preexisting women’s consumer cultures, with female teenagers and women in their twenties emerging as the primary fans of K-pop idol groups.26 Discussions I had with young women fans during a trip to Tokyo in 2020 revealed that they did not see K-pop fandom as separate from their broader consumption of Japanese women’s media.27 In fact, many indicated that it was “obvious” (atarimae) that Japanese women would be attracted to Korean popular culture since it represents just one facet of what one interlocutor termed “girls’ culture” (shōjo bunka).28 My observations and conversations with fans between 2015 and 2020 revealed that K-pop fandom had entered into dialogue not only with Japan’s own established idol culture but also with the shōjo manga (girls’ comics) at the heart of Japanese girls’ culture.29

One genre of shōjo manga played an especially prominent role in influencing how young women consumed and enjoyed media about K-pop idols in Japan: the aforementioned Boys Love manga. It is via Japanese fans’ engagement with this popular culture form that they learn about and begin to practice shipping. The connection is unsurprising since K-pop developed in part due to production companies’ earlier adaptation of these very practices to the South Korean context. Indeed, in a book focused on the lasting appeal of TVXQ in Japan, cultural critic Ono Toshirō points to “K-pop idol yaoi” among female fans of the boy band as one reason for the group’s continued success in the Japanese market.30 Highlighting that Japan’s long tradition of Boys Love manga provided women the “necessary knowledge” to produce homoerotic fantasies, Ono notes that “playing with yaoi” (yaoi de asobu) represents an important “method of experiencing pleasure” through K-pop idol consumption.31 Interestingly, the Japanese character that Ono uses in his writing to refer to pleasure (愉) typically connotes sexual forms of pleasure, especially orgasm. Just as idol shipping allows women in South Korea to explore their sexual desires, Ono argues, shipping idols through the logics of Boys Love provides young Japanese women a form of sexual release often denied them within Japan’s patriarchal society.32

Emerging out of shōjo manga in the mid-1970s, Boys Love focuses on intimate relationships between beautiful male youths and possesses narrative logics born out of Japanese conceptualizations of gender and sexuality.33 One particularly important narrative trope is the so-called seme-uke rule, which stipulates that one member of a male-male couple is characterized as an uke (receiver) who is passively initiated into male-male romance by an aggressive seme (attacker) who subsequently “leads” their relationship.34 Cultural critic Nishimura Mari argues that this seme-uke relationship is typified by a power imbalance usually signaled to readers via set representational strategies known in Japanese as the “noble path” (ōdō).35 First, the seme is typically depicted as taller, older, and considerably stronger than the uke.36 Second, the seme is regularly characterized as reserved and stoic, but with a strong and uncontrollable sexual desire that is awakened by the virginal innocence of the uke.37 Third, the uke represents the partner who is penetrated during sex and is typically presented as “soft” and “effeminate” compared to the penetrating seme, usually depicted as comparatively “harder” and more “masculine.”38 This seme-uke rule was transplanted to South Korea, where K-pop idol shippers similarly position couples as containing a gong (seme) and a su (uke) member.

When examining how the members of BTS are typically shipped in Japan, it becomes apparent that this seme-uke rule also strongly influences how Japanese fans of K-pop both practice and understand idol shipping. According to a representative chapter on shipping in The BTS Fanatic’s Manual, one of fifteen BTS “mooks” (magazine books) I have gathered during trips to Japan between 2018 and 2020, all of which contain a section addressing shipping, the so-called love-love relationships between the members naturally fall into seme-uke couples.39 The “mook” lists eleven particularly popular ships, providing a brief introductory text as well as ratings for each potential couple’s “love level” and “likelihood of appearance.” The following ships are presented to the reader in order of apparent popularity among Japanese fans: Jimin x Jungkook, RM x J-Hope, Jin x V, Suga x Jungkook, Jimin x V, Suga x V, V x Jungkook, J-Hope x Jungkook, Jin x J-Hope, J-Hope x Jimin, and RM x Suga. The use of the “member x member” method of framing the ships is significant and ultimately derives from Boys Love fan practices where “seme x uke” has become the standard way of naming a male-male couple.40 Speaking about the role of the seme-uke rule with three Japanese idol shippers I met at a K-pop merchandise store in Ikebukuro in 2020, I learned that it was rare for the authors of Japanese shipping fan fiction or comics to position members as switching their sexual roles. Further, these women reinforced the idea that an uke is somehow “feminine” (onnarashii), with one fan suggesting that the youngest member of BTS, Jungkook, was like a “young princess (ohime-sama kyara) protected by six knights.”41

Except for two prominent examples both involving RM, the leader of BTS, an older member of BTS is always presented as the seme and a younger member is presented as the uke within each of the BTS ships listed above. The texts in the “mook” stress the brotherly nature of each pairing, such as in the following description of the Jimin x Jungkook couple: “whenever he has free time, somehow Jimin nii-san (older brother) comes over to Jungkook. Usually Jungkook treats Jimin as if he is some kind of nuisance, but it is clear that Jungkook enjoys being spoiled by this loving older brother.”42 Following the narrative and characterization conventions of the seme-uke rule, the status of one member as an “older brother” provides him with power and thus positions him as a logical seme for Japanese fans. Further, the focus on “watching over” (mimamoru) and “spoiling” (amaeru) in the descriptions in this “mook” of each couple’s uke replicates common-sense understandings of romantic relationships in Japan, where a man (or “masculine” seme) is expected to take charge of a relationship with an innocent woman (or “feminine” uke). The two cases where this age-based shipping is not practiced in the eleven potential couples from The BTS Fanatic’s Manual are where the group’s leader RM is positioned as the seme. Within the texts of these two ships, rather than RM’s age, it is his status as leader of BTS that positions him as a powerful seme, particularly in the description of the RM x Suga couple, where the two members are described as the group’s “father and mother” (fūfu kappuru) figures, respectively.43

This brief example shows that Japanese idol shippers follow logics that appear somewhat rigid, slotting K-pop band members into a predetermined gendered formula based on traits such as age or position in the band. What appears most important within the Japanese context is the broader positioning of boy band members as either seme or uke, which in turn influences how consumers present the gendered identities of the characters within their derivative fan works. It is for this reason that the fans I met in Ikebukuro fantasized about Jungkook being a “princess” protected by six older “knights.” The categories of seme and uke are not understood by fans as identities, however; many young women I interviewed strongly disavowed the idea that the characters appearing within fan works were gay men defined by their sexual desires. Rather, our conversations revealed that the descriptors seme and uke were used to make sense of idol behaviors, either in reality or within fan works, with debates over who represents a seme or an uke producing an affective response known in Japanese as moe. Indeed, these K-pop shipping practices mimic how Japanese Boys Love manga fans also derive explicit pleasure from their supposed “moe talk” (moebanashi).44 Fans thus creatively manipulate the character tropes of the seme and uke to produce homoerotic relationships between male idols that are charged with romantic or erotic potential, providing meaningful ways for them to celebrate the K-pop idols they adore.

While the logics of Boys Love manga have rightly been criticized as replicating heteronormative relationship structures by implicitly positioning the seme and uke as figurative men and women,45 I do not want to dismiss the queer potentials of such fandom practices. Through fantasies of homoeroticism created through the manipulation of the seme-uke rule, Japanese female fans mobilize queer sexuality as an important method to express their own attraction to K-pop idols and thus produce pleasures that theorists such as Ono acknowledge as explicitly sexual.46 The seme-uke rule therefore provides a framework and vocabulary with which to vocalize and celebrate the inherently erotic affects induced by K-pop fandom. Ultimately, Japanese fans draw on a preexisting tradition with a long history in Japanese girls’ culture as one of many methods to make sense of their attraction to the members of popular K-pop groups. K-pop idol shipping thus represents a significant emerging practice in Japan’s girls’ culture that deploys queer sexual expression to conceptualize young Japanese female fans’ sexual and gendered identities.

Shipping BTS in Anglophone Fandom: Queer Sexuality and the Politics of Identity

One Saturday in January 2020, I joined over a hundred passionate fans of BTS at an inner-city gallery in Sydney to attend a photography exhibition dedicated to members Jimin and Jungkook that had been collaboratively organized by Australian and South Korean social media fan sites. As I wandered and interacted with fans throughout the day, I learned that many of those who had gathered in the gallery had come to celebrate what an organizer termed the “close relationship” between Jungkook and Jimin,47 as well as to purchase fan-produced merchandise featuring this popular pair. Although the event was advertised as targeting all ARMY, a significant portion of the attendees with whom I interacted identified as shippers of Jimin and Jungkook, a pairing known in Anglophone fandom as “Jikook.” Unlike in Japan, however, many of the shippers I met at this Sydney gallery were gay men who viewed their K-pop fandom as intrinsically tied to their queer sexual identities (throughout the day I met eight such fans). This did not surprise me, as previous research I had conducted among LGBTQ consumers of Japanese and Korean popular culture in the Philippines, where K-pop fandom is particularly prevalent in the LGBTQ community,48 showed that queer Philippine fans also practice K-pop idol shipping. My experiences with English-speaking BTS fans in Australia and the Philippines confirmed that K-pop idol shipping was common in Anglophone fandom spaces.

Unlike in Japanese and South Korean fandom, where the logics of the seme-uke rule and influence from Boys Love manga fandom have strongly shaped shipping practices, idol shipping within Anglophone contexts appears more closely aligned to an identity-based conceptualization of queer sexuality born out of LGBTQ identity politics. By LGBTQ identity politics, I refer to the common tactic within Western queer liberation activism where concrete identity categories such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender are deployed as a form of strategic collective action.49 My conversations with fans in Australia and the Philippines who actively participate in idol shipping culture online – typically reading and writing fan fiction or engaging in shipping debates on social media such as Twitter – found that Anglophone fans tend to conceptualize shipping as an explicit reimagining of idols as identifying as members of the LGBT community. Marcus,50 a gay Australian fan of both K-pop and Japanese manga, explained to me during a conversation in 2019, “When I ship BTS, it’s kind of like a fantasy where I imagine my bias [favorite member] is gay and likes boys.”51 Likewise, a bisexual fan of BTS in the Philippines named Maria noted that she liked “taking the members of BTS and making them gay,” explaining that shipping was a process of “turning the boys queer.”52 Interestingly, Maria viewed idol shipping as a political act that helped to “raise the visibility” of “queer identity” in the context of the “heteronormative culture of the Philippines.”53

Another queer Filipino fan named Leon likened K-pop idol shipping to “gay porn,” noting that both queer and straight fans “imagine our favorite members fucking” as a way to enjoy explicit sexual fantasies of “hot boys who turn us on.”54 I also encountered this positioning of K-pop idol shipping as a form of pornography during a conversation with a gay male fan and his heterosexual female friend at the gallery event in Sydney, with both suggesting that the “power” of “shipping Jikook” came from repurposing the two members’ close “brotherly” relationship as a “hot gay fantasy.”55 Even many heterosexual female fans I met in Australia made similar comments. For instance, a Chinese Australian K-pop fan named Lisa explained to me in 2018 that while she did not practice shipping herself, she understood it as a form of “gay porn” among some Australian fans.56 As these narratives suggest, K-pop idol shipping is one method through which fans celebrate and express sexual attraction to idols through erotic fantasy play. In so doing, they consciously utilize the language of LGBTQ identity politics to label the members as explicitly same-sex attracted, making this the central focus of the fantasy.

In English-language fan fiction for BTS on Archive of Our Own, one of the world’s largest online fan fiction repositories,57 most of the uploaded shipping fics position at least one of the members as directly identifying with their same-sex attraction (e.g., identifying as gay, bisexual, queer, or poly[amorous]). A search for the word “gay” reveals that 60.3 percent (61,497/101,964) of male-male BTS fan fiction hosted on the site deliberately deploy the term to either identify a character or describe the sex acts that occur between members. A minority of BTS fan fiction takes this even further, strongly tying the shipping of idols within erotic, romantic, or pornographic contexts to explicit LGBTQ activism. One example is a fan fiction entitled The Paradiso Lounge, which explicitly situates a highly pornographic romance between BTS members Suga and Jimin within the context of New York City’s 1990s BDSM community. Tagged as specifically concerned with “social justice,” the fic reimagines Yoongi (Suga’s real name) as a queer activist photographer who eventually falls in love with Jimin, a sex worker at an underground leather bar. The following excerpt provides an example of how The Paradiso Lounge ties K-pop idol shipping to broader LGBT activism:

“Oh, you document the community?” Jimin asked in an interested tone, retrieving an ashtray from the edge of the table to place it down in the middle for them to share. “Does that mean you travel around the city a lot? Snapping photographs of gay establishments and safe spaces? Going to the HIV and AIDS protests, and all the other marches and protests? Is that what you document?”

“I’ve been ’round,” Yoongi said with a lazy nod, finding it far easier to study the glowing cherry of his cigarette than to hold the other man’s gaze. “I’ve been right to the heart of the community, y’know, the protests, the condom and needle drives, the fundraisers – the social aspect that keeps us going in this toxic society. But I’ve been to the fringes too like, uh, the radicals, the militants. The radical feminist lesbians, the pinko faggots; the kinda gays that exist in our community that the gatekeepers don’t talk ’bout ’cos they’re a threat to the heteronormative society far too many think we should accept a part in, rather than refuse to conform to.”58

Throughout my conversations with Anglophone fans, I learned that most who practiced idol shipping were keenly aware that it was based in fantasy, and none believed that the members of BTS who they shipped together were actually attracted to the same sex. Rather, as Marcus explained to me, idol shipping was a kind of “play” designed to enjoy their fandom for BTS in “exciting and sexy ways.”59 In this sense, despite the logics that influenced their conceptualization of shipping being radically different, both Japanese and Anglophone BTS shippers are involved in a highly creative and affective practice tied to their desires as fans. For Sandy, a bisexual female fan in Australia, shipping BTS (and she noted that she also shipped members of the K-pop girl group 2NE1) represented just one of many methods to “express my love for the members of the band.”60 She explained it was a “release valve” for the sexual tension that fans of BTS often express, suggesting rather humorously that “you have to do something to scratch that itch when you see the boys grinding against each other on stage!”61 Ultimately, K-pop idol shipping possesses queer potentials through its celebration of male-male erotica, which allow fans to vocalize and explore their sexual attraction, acknowledging that sexual desire plays an important role in broader K-pop fandom.

Not all fans of BTS in Anglophone contexts view K-pop idol shipping positively. Within Western fandom spaces there have been long-running historical debates concerning the ethics of “real person shipping.”62 In an article polemically titled “Your OTP Is Not Real: Why Idol ‘Shipping’ Has No Place in K-Pop,” a contributor to the K-pop blog Seoulbeats argues that shipping is “a potentially harmful activity to both the fans and idols in question” because it supposedly promotes skewed understandings of same-sex relationships among fans.63 The author concludes by arguing that shipping is a “self-indulgent activity when real people with real feelings are the ones being manipulated for the sake of entertainment and fantasy,” suggesting that instances where K-pop production companies produce content aligned with shipping represent “a step too far.”64 This is a pervasive discourse within Anglophone spaces that seems to be absent within both South Korean and Japanese K-pop fandom, and some BTS shippers I interviewed in the Philippines had strong criticisms for those who held such views. A bisexual fan named Zoe argued that such critiques neglected the fact that fans understand that they are involved in fantasy play, strongly disassociating shipping from reality.65 As Maria strongly believed shipping was a queer political act, she likewise viewed such attempts to censure shipping as a form of heteronormative backlash designed to silence fans engaged in subversive practices.66 While there are important ethical debates to be held over shipping real people, especially within highly pornographic fan fiction, this does not negate the fact that the fantasy shipping produces is a legitimate way to explore the sexual desires central to K-pop fandom.

Concluding Remarks