‘In healthcare, many of our best workers have left because the barriers to doing their jobs seem insurmountable and eventually take away their sense of doing purposeful, worthwhile work’ (Studer, Reference Studer2004: 52). Despite healthcare professionals having to deliver high-quality and low-cost care with a shrinking workforce (Briggs, Cruickshank, & Paliadelis, Reference Briggs, Cruickshank and Paliadelis2012), positive impacts on organisation outcomes are being made. Positive stories, positive behaviours and actions, as well as positive outcomes, to illustrate what works well in health service management and leadership and ‘brilliance’ in healthcare are missing (Dadich et al., Reference Dadich, Fulop, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2015: 752; Fulop et al., Reference Fulop, Dadich, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2013), despite these positive changes.

The emerging movement known as Positive Organisational Scholarship in Healthcare (POSH) seeks to understand human excellence in healthcare (Cameron, Dutton, & Quinn, Reference Cameron, Dutton, Quinn, Cameron, Dutton and Quinn2003) and ‘investigat[e] positive dynamics, positive attributes, and positive outcomes in organisations’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2008: 7). POSH ‘represents one approach to examine, understand, and ultimately enhance health service management’ (Kippist, Dadich, Fulop, Hayes, Karimi, & Smyth, Reference Kippist, Dadich, Fulop, Hayes, Karimi and Smyth2016: 4). The tools used to study POSH include: appreciative inquiry, relational coordination, and positive deviance (Fulop et al., Reference Fulop, Dadich, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2013). For the purpose of this research, we centre our attention on positive deviance.

Positive deviance has numerous definitions. The sociological definition by Heckert and Heckert (Reference Heckert and Heckert2002: 466) refers to positive deviance as a ‘type of behaviour … that exceeds normative standards and evokes a positive response’. The organisational scholarship definition by Spreitzer and Sonenshein (Reference Spreitzer and Sonenshein2004: 828) refers to positive deviance as ‘intentional behaviours’ both of which divert away from what is considered the norm within the context of the group or community. Others define positive deviance as a work results measure (‘verifiable, replicable, and scalable’) (Pascale & Sternin, Reference Pascale and Sternin2005: 3), the behaviour itself, the outcomes of the behaviours, or both. In this study, a combination of the latter definitions is applied such that positive deviance is defined as intentional behaviours that are outside the norm and which render positive outcomes.

Despite the desire to understand human excellence in health, there has been limited attention to how positive deviance is enacted within healthcare (Cameron, Dutton, & Quinn, Reference Cameron, Dutton, Quinn, Cameron, Dutton and Quinn2003; Dadich et al., Reference Dadich, Fulop, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2015). In particular, how positive nurse manager behaviours make a difference in the healthcare environment has been under-investigated (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman2004b; see Crewe, Reference Crewe2017 for a review). Nurse managers are, however, strategically positioned to create positive work environments so that employees flourish and grow in their professions and attain both positive human experiences and outcomes (Cameron & Caza, Reference Cameron and Caza2004; Havens, Reference Havens2011).

Studies of nurse managers support that certain leadership behaviours positively influence staff outcomes such as nurse satisfaction, job satisfaction, commitment, intention to stay, turnover intention, and retention (see Belbin, Erwee, & Wiesner, Reference Belbin, Erwee and Wiesner2012; see Feather, Reference Feather2015 and Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, O'Brien-Pallas, Duffield, Shamian, Buchan, Hughes and North2012 for reviews). In a study examining which leadership style ‘contributes to optimum outcomes under differing spans of control’, Doran et al., (Reference Doran, McCutcheon, Evans, MacMillan, McGillis Hall, Pringle and Valente2004: ii) found nurse managers with positive leadership styles ‘stimulate[d] and inspire[d] followers’ to attain a higher purpose, and attain increased patient and staff satisfaction, and lower turnover. Cameron (Reference Cameron2013: 10) showed that organisations in the healthcare industry which implemented positive leadership practices yielded various performance improvements in ‘profitability, productivity, quality, customer satisfaction, and employee retention’. These outcomes mirror those of Cowden, Cummings, and Profetto-McGrath (Reference Cowden, Cummings and Profetto-McGrath2011), Duffield, Roche, Blay, and Stasa (Reference Duffield, Roche, Blay and Stasa2010), Duffield et al. (Reference Duffield, Diers, O'Brien-Pallas, Aisbett, Roche, King and Aisbett2011) and more recently, Halter et al. (Reference Halter, Pelone, Boiko, Beighton, Harris, Gale and Drennan2017) who showed that leadership styles, for example, relational and transformational leadership styles, which support people-centred approaches, delivered positive work outcomes.

While there is countless evidence of the importance and relevance of a leadership style which is attentive to staff needs (see Cowden, Cummings, & Profetto-McGrath, Reference Cowden, Cummings and Profetto-McGrath2011) and which promotes ‘… a strong sense of purpose’ (Duffield et al., Reference Duffield, Roche, Blay and Stasa2010: 26) to achieving positive outcomes, the positive leadership behaviours that promote such outcomes are less well understood. Positive leadership is rooted in positive organisational scholarship and seeks to produce positive (exceptional) performance and outcomes with an emphasis on positive deviance and positive deviant behaviour to drive outcomes (Cameron, Reference Cameron2008, Reference Cameron2013; Martin & Wright, Reference Martin and Wright2018). In this study, we aim to identify how positive nurse manager behaviours that deviate from ‘business as usual’ promote positive nurse outcomes. Using an interpretivist methodology, we focus on uncovering how positive deviance manifests in the work environment to positively impact nursing outcomes.

Review of the literature

The extant literature provides sufficient evidence to support that nursing leaders (both operational and non-operational) are key players in influencing individual outcomes (including satisfaction, engagement, and retention) through positive interventions and leadership approaches (Bish, Kenny, & Nay, Reference Bish, Kenny and Nay2015; Brown, Fraser, Wong, Muise, & Cummings, Reference Brown, Fraser, Wong, Muise and Cummings2013; Chiok Foong Loke, Reference Chiok Foong Loke2001; Lawrence & Richardson, Reference Lawrence and Richardson2014; McNeese-Smith, Reference McNeese-Smith1997). Results from a recent scoping review (Crewe & Girardi, Reference Crewe and Girardi2018) revealed the nurse manager role was a major influencer of staff outcomes. The dominant role of the nurse manager emerged as that of Employee Champion (Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1997), with the nurse manager responding to the needs of staff in the workplace, empowering staff and increasing their commitment. The extent to which nurse managers exercise leadership in influencing organisational outcomes (such as patient and staff outcomes) is a response to the multiplicity of roles that nurse managers have and take on within the healthcare setting.

As an organisational objective, for example, nursing executives (leaders in an executive and non-operational role) have presumed the remit for staff engagement and retention. The progressive devolution of the human resource management (HRM) function to nurse managers as line managers (Francis & Keegan, Reference Francis and Keegan2006) has meant that nurse managers (operational leaders) are often best suited to understand the issues impacting nurses and the factors that contribute to retaining them (Tuckett, Winters-Chang, Bogossian, & Wood, Reference Tuckett, Winters-Chang, Bogossian and Wood2015). Nurse managers themselves recognise they play an important role in the decentralised HRM function within their workplaces, despite not being HRM specialists (Townsend, Wilkinson, Allan, & Bamber, Reference Townsend, Wilkinson, Allan and Bamber2012), and that ‘management of human capital underpins effective healthcare delivery’ (McDermott & Keating, Reference McDermott and Keating2011: 678) to ultimately attain organisational goals.

Traditionally nurse managers were clinical experts positioned in a leadership role (often as a unit head) to mentor, coach, educate, and train junior nurses, even though they were not necessarily directly responsible for day-to-day staff professional development (Duffield, Wood, Franks, & Brisley, Reference Duffield, Wood, Franks and Brisley2001). The move away from the management of clinical activities to responsibility for administrative functioning of the unit (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Standing, Glick, Duffy, Paschall, Sauer and Dumpe2005) is indicative of the role of many nurse managers. In Australia, for example, the nurse manager role has transferred from being solely a clinical expert to that of a unit manager (Duffield, Reference Duffield1991). Typically, the nurse manager is responsible for resources as unit head, although in some organisations this shift to an administrative role no longer requires the unit nurse manager to be a clinical expert.

In parallel, the scope of the nurse manager position has been further magnified to take on a strategic charge (Kearin, Johnston, Leonard, & Duffield, Reference Kearin, Johnston, Leonard and Duffield2007). Nurse managers are required to manage not only the exigencies they face day-to-day in nursing services (for example, staff professional development) (Duffield et al., Reference Duffield, Wood, Franks and Brisley2001) but also the increasing complexities, demands, and pressures of the sector (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Standing, Glick, Duffy, Paschall, Sauer and Dumpe2005; Briggs, Cruickshank, & Paliadelis, Reference Briggs, Cruickshank and Paliadelis2012). Despite sometimes rigid professional and nursing leadership structures, hindered by ‘inflexibility … and … hierarchy (control by roles, rules, and routines)’ (Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich, & Brockbank, Reference Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich and Brockbank2017: 53), nurse managers are forced to exercise strategic agility to meet service standards and deliver excellence.

In a systematic literature review (Crewe, Reference Crewe2017) with the aim of understanding the impact of nurse manager leaders on retention, the findings revealed that there was no one leadership style touted as the most effective in influencing positive outcomes. Almost 40% of all the studies reviewed (n = 25) did not identify a specific leadership style, whilst the remaining 60% focused on leadership styles that can be considered relational. Over 30% of these studies focused on transformational leadership, with the remaining 70% studies on a mix of authentic, committed, and positive leadership.

For example, Cowden, Cummings, and Profetto-McGrath (Reference Cowden, Cummings and Profetto-McGrath2011) show that by practicing relational leadership and meeting staff needs, nurse managers positively influenced the work environment. Duffield, Roche, O'Brien-Pallas, Catling-Paull, and King (Reference Duffield, Roche, O'Brien-Pallas, Catling-Paull and King2009) show the nurse manager role as important in retaining staff, as does, Kleinman (Reference Kleinman2004c) and Taunton, Boyle, Woods, Hansen, and Bott (Reference Taunton, Boyle, Woods, Hansen and Bott1997). Cummings et al. (Reference Cummings, Olson, Hayduk, Bakker, Fitch, Green and Conlon2008) surveyed 615 nurses to examine factors of an oncology ward work environment and showed that relational leadership, which focused heavily on personal relationships (namely, positive relationships between nursing staff, nurse managers, and physicians), influenced a variety of positive outcomes. These included creating a conducive environment and opportunities for meaningful work amongst nursing staff. For example, with increased nurse autonomy and participatory decision-making, nurses developed long-term nurse-patient relationships to ‘make a difference in the lives of their patients and families’ (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Olson, Hayduk, Bakker, Fitch, Green and Conlon2008: 510) which ultimately increased nurses' job satisfaction.

These outcomes affirm the importance of relational leadership styles to promote positive interactions and relationships between the nursing leadership and the staff to attain positive outcomes by creating ‘positive human experiences in [the] organisation’ (Cameron & Caza, Reference Cameron and Caza2004: 734). These outcomes further suggest that effective leadership in nursing and healthcare services is attentive to staff needs (Cowden, Cummings, & Profetto-McGrath, Reference Cowden, Cummings and Profetto-McGrath2011), is people-centred, and focuses on ‘creating a vision, collaboration, approachability, and empowerment’ (Lawrence & Richardson, Reference Lawrence and Richardson2014: 73), whilst ‘instilling a strong sense of purpose’ (Duffield et al., Reference Duffield, Roche, Blay and Stasa2010: 26). This supportive, people-centred approach is characteristic of positive leadership.

Positive leadership is defined by Cameron (Reference Cameron2008: 1) as ‘the ways in which leaders enable positively deviant performance, foster an affirmative orientation in organisations, and engender a focus on virtuousness and eudemonism’. The primary objectives of positive leadership are ‘to produce extraordinarily high performance, generate positively deviant results, and create remarkable vitality in the workplace’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2013: 2). While there is limited empirical research specifically addressing the impact of positive leadership on work-related outcomes, the work of Cameron (Reference Cameron2008, Reference Cameron2013) supports that leaders who practise positive leadership stimulate positive outcomes. Moreover, there has been an increase in research on authentic leadership detailing the impact of positive leadership practices (Wang, Sui, Luthans, Wang, & Wu, Reference Wang, Sui, Luthans, Wang and Wu2014). In organisations where these practices have been implemented, increased positive outcomes such as ‘profitability, productivity, quality, customer satisfaction, and employee retention’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2013: 10) have been identified. Specifically in organisations in the healthcare industry where positive leadership practices were implemented, various performance improvements were demonstrated (Cameron, Reference Cameron2013). For instance, positive organisational outcomes such as increased patient satisfaction, increased staff satisfaction, and lower turnover, were the result of positive leadership styles of nurse managers who inspired staff to attain a higher purpose (Doran et al., Reference Doran, McCutcheon, Evans, MacMillan, McGillis Hall, Pringle and Valente2004: ii).

These outcomes expounded by Cameron and Wooten (Reference Cameron and Wooten2009: 5) are based on the ability of leaders to stimulate positive energy in their followers, and unlock their potential by: fostering a positive work climate through practising compassion, forgiveness, and gratitude in the workplace; enhancing positive relationships among organisational members by modelling and identifying positive energisers to create positive networks in the organisation; through practising supportive positive communication, and facilitating staff engagement through encouraging language and positive feedback; and associating work with positive meaning by demonstrating to staff the connection between the effects of their work, benefits derived from the work, meaningfulness, and legacy. There is a view that the core concept of positive leadership is rooted in positive organisational scholarship and by virtue of its nature, positive leadership necessitates positive deviant behaviour for the attainment of positive outcomes (Martin & Wright, Reference Martin and Wright2018). This is the view subscribed to in this research. However, there is a lack of empirical evidence as to the nature and practice of positive deviance, and how it manifests to facilitate outcomes. While this may be a result of types of leadership studies being pursued in the extant literature, little is known about how nurse manager leadership behaviours contribute towards positive outcomes (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman2004a). This begs the question ‘what is it that nurse managers do to promote a positive work environment?’ (Duffield et al., Reference Duffield, Roche, Blay and Stasa2010: 25). Havens (Reference Havens2011) suggests that investigating instances of positive deviance in healthcare will contribute to shaping its services by drawing out positive behaviours and outcomes. Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas, and Van De Ven (Reference Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas and Van De Ven2013) affirm that focusing on acts of positive deviance will promote the unpacking of how and why things occur, which may assist in better understanding what nurse managers do within the context of their situations and work environments, to positively influence organisational outcomes. Therefore, this study focusses on how positive deviance is manifested in the work environment to positively impact nursing outcomes.

Method

An interpretivist methodology (Bourgeault, Dingwall, & De Vries, Reference Bourgeault, Dingwall and De Vries2010) was used to explore the stories of 24 nurse managers who participated in face-to-face in-depth semi-structured interviewsFootnote 1. A convenience sample of seven nurse managers from a private hospital in Australia (29%) and 17 from the public health sector in Seychelles (71%) was used. Ethics clearance was obtained from relevant authorities for this study.

All the participants (except one) work as full-time nurse managers. The majority are 46 years of age or above and have vast work experience. Eighty-three percent have 20 or more years of experience in nursing. Almost half (43%) of the respondents have a Bachelor's Degree or higher; with 42% holding Diploma level (including Advanced Diploma) qualifications.

Positive deviance

In order to study POSH, positive deviance is used as the theoretical lens to determine behaviour that deviates from the norm and to identify ‘champions’ who stand out from the crowd as exceptions to these norms (Fulop et al., Reference Fulop, Dadich, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2013). While this approach has been identified as potentially limited in highly regulated environments, such as healthcare (see Dadich, Collier, Hodgins, & Crawford, Reference Dadich, Collier, Hodgins and Crawford2018), it has the potential to provide an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of what constitutes deviance in the particular nuances of the context. In this case, the healthcare context as experienced by nurse managers working in public and private sector settings is considered, and a normative approach applied (Cameron & Caza, Reference Cameron and Caza2004).

The analytical framework

The interpretation of data and determining deviant behaviours can be difficult particularly when identifying positive deviance in context-specific scenarios, which have the disadvantage of being unable to be replicated. This creates a challenge for researchers to ensure the verification of the interpretation of the data, in this case, determining positive deviance. ‘The Framework Method’ (see Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013: 4–5) was adapted to analyse the interview data to address this limitation. The framework presented in Figure 1 consists of six main stages including data transcription, interview familiarisation, coding, the development of an interpretive framework to identify incidents of positive deviance, and then charting these incidents to identify themes common to the scenarios of deviance.

Figure 1. Analytical framework.

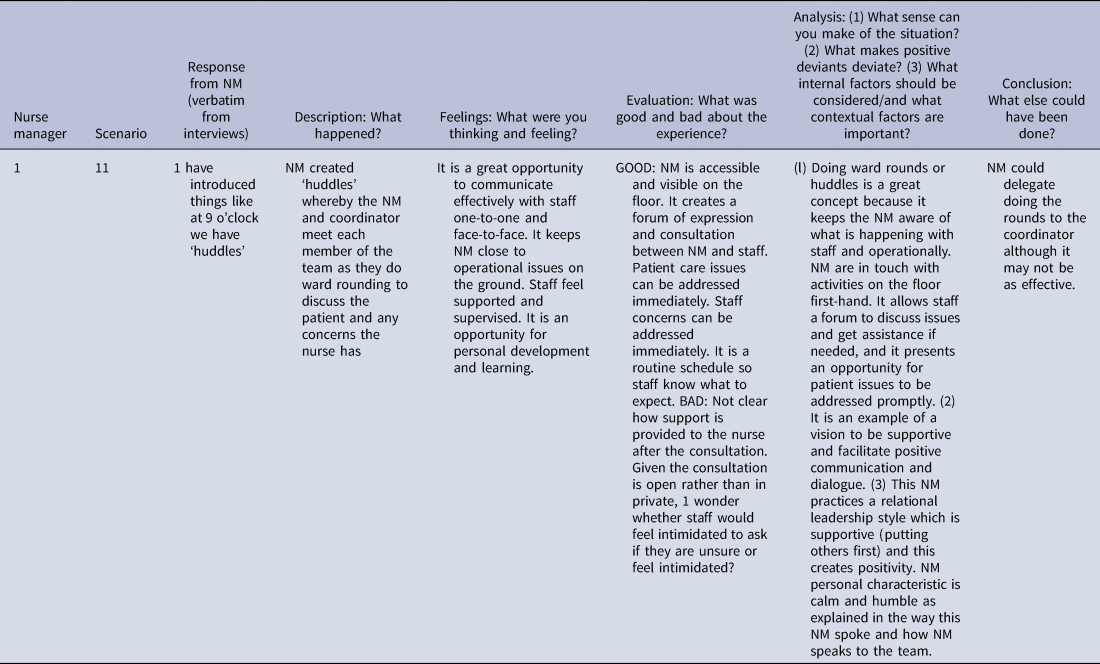

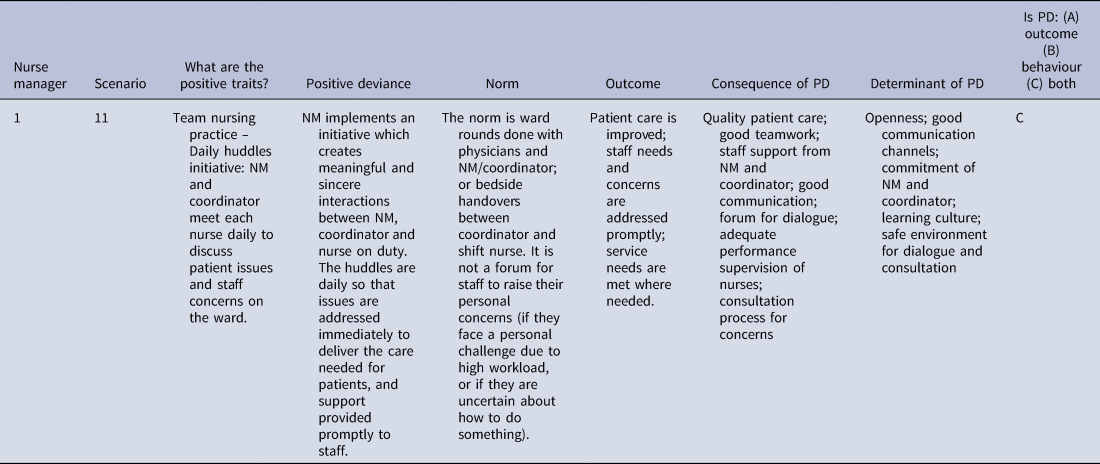

During the coding process, the stories provided by participants were clustered as positive and negative behaviours and outcomes. Scenarios described by nurse managers which represented a positive story (a positive behaviour, positive outcome, or both) were extracted from the transcribed interviews and analysed via a systematic approach using an interpretive framework. Tables 1 and 2 present a sample of the application of the interpretative framework for an individual nurse manager's story.

Table 1. A sample vignette using Gibbs (1988) Reflection Model and Lavine's (Reference Lavine, Cameron and Spreitzer2012) probes

Note. Retrieved from: Gibbs (Reference Gibbs and Gibbs2013). Copyright 2001 by Oxford Brookes University; and Lavine (Reference Lavine, Cameron and Spreitzer2012). Copyright 2012 by Oxford University Press.

Table 2. A sample vignette applying Mertens et al. (Reference Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn and Kummer2016) positive deviance framework

Note. Retrieved from Mertens et al. (Reference Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn and Kummer2016). Copyright 2016 by Taylor and Francis.

This interpretive framework was developed by assimilating Gibbs' (1988) ‘Model for Reflection’ (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs and Gibbs2013: 49–50) and Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn, and Kummer (Reference Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn and Kummer2016) ‘Positive Deviance Framework’ (see Mertens et al., Reference Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn and Kummer2016: 1288) to provide a robust interpretation of the nurse manager interviews, and thereafter, to identify positive deviance. This involved integrating the five phases outlined in Gibbs' (1988) Model (see Table 1, row 1) with the six-stage positive deviance framework (see Table 2, row 1).

Mertens et al.’s (Reference Mertens, Recker, Kohlborn and Kummer2016) framework facilitates understanding of positive deviance within the context of a manifested behaviour – the outcome of the behaviour, the behaviour itself, or both – which deviates from salient workplace norms. Determining the ‘norm’ in a given scenario is essential, since what is the norm in one situation will not be the case in another. For each of the stories, positive deviance was considered in light of nurse manager behaviours that either display uncommon behaviours or highlight nurse managers who are successful despite the challenges they face (see Herington & van de Fliert, Reference Herington and van de Fliert2018). Gibbs' (1988) Model is a sense-making tool designed to assist with judging deviance from norms to document behavioural patterns. This model was used to determine what ‘happened’ in each story provided, to evaluate the scenario, and to make sense of the situation.

This evaluation was guided by Lavine's (Reference Lavine, Cameron and Spreitzer2012: 1023) probes: ‘What makes positive deviants deviate?’ and, ‘What internal factors should be considered, and what contextual factors are important?’ (see Table 1, column 7). These stories were then charted, and thematic analysis was used to better understand the characteristics of the positive deviance. Four main types of positive deviance emerged centred on: positive meaning, positive relationships, positive climate, and positive communication.

Outcomes

The nurse managers' stories provide insights into positive behaviours, experiences, and relationships afforded by the role of the nurse manager and positive outcomes. Across the stories, four themes emerged which align with Cameron's (Reference Cameron2008, Reference Cameron2012, Reference Cameron2013) work on positive leadership. Cameron and Wooten (Reference Cameron and Wooten2009) identify four strategies of positive leadership, namely, enabling: positive meaning, positive relationships, positive climate, and positive communication. These are explicated below.

Positive meaning

Leaders create positive meaning by helping people to engage in work that is purposeful both at an individual and organisation level (Cameron & Wooten, Reference Cameron and Wooten2009). Across the stories, nurse managers identified the importance of building a community to create meaningful interactions. Nurse managers acted strategically to address the challenge of meeting organisational demands for increased productivity with fewer financial and human resources, whilst maintaining service levels and high-quality patient care. Positive work practice interventions emerged from a number of stories. An example of two initiatives on a ward is illustrated in Vignette 1.

Vignette 1

‘I have introduced things like at 9 o'clock we have ‘huddles’ where … I go around with the coordinator and we talk to each of the team – we do team nursing – each of the three teams and we discuss any patient concerns and any worries they have. And I have linked that into another idea … the traffic light system so: Red means ‘you are hiding under a desk crying and you refuse to come out’; yellow means that ‘if you don't get help soon, you will be sitting under the desk soon’; and green means ‘you are absolutely fine’. So we put the magnets up there … on the board and … they've embraced it. Like you put a yellow up there and within five minutes you look around and you don't even need to say anything. People wander off and do some things for them. It's fantastic, it's a lovely ward.’ – Nurse Manager 1

This vignette demonstrates how Nurse Manager 1 took on a positive leadership role and established an innovative cultural change process to reduce frustration and stress amongst nursing staff on the ward. The Nurse Manager 1 championed a ‘traffic light’ system, which stimulated support within the team in a timely and discreet manner. This is an example of excellence. The non-verbal communication mechanism enabled the operational day-to-day service requirements to be met, and facilitated the nurse overcoming the adversity faced at that time. Uniquely, while the challenge was operational, this system had a relational focus and removed the potential loss-of-face for those nurses facing challenging workload conditions. The ‘huddles’ provided an opportunity for the nurses to discuss any concerns with Nurse Manager 1 and the Coordinator at their discretion.

Positive relationships

Leaders enable positive relationships by modelling and pooling positive energisers to build positive energy networks (Cameron & Wooten, Reference Cameron and Wooten2009). High patient volumes, high patient turnover, heavy nurse workloads, and creating high service demands are common features in hospital wards (see Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Standing, Glick, Duffy, Paschall, Sauer and Dumpe2005). In most circumstances, this requires the nurse manager to focus on operational efficiencies to achieve organisational outcomes. However, several nurse managers described activities and behaviours that resulted in outcomes which were only possible when the nurse manager enabled positive relationships, despite high-level operational demands.

The stories that follow showcase nurse managers taking on multiple roles in their respective wards. These roles centred on creating positive relationships with staff and patients to produce excellence in critical operational areas of quality patient care and outstanding service delivery. Leading by example is demonstrative of the nurse managers' commitment to manage the strains between their roles: balancing their administrative (unit head or office manager) role with their clinical leader role. Nurse managers are viewed by staff to be supportive because they are practically and clinically assisting where needed and making a positive contribution to the team (as illustrated in Vignette 2).

Vignette 2

‘I was out making cups of tea … before you came. Get out of the office, talk to your staff, be a role model, do patient rounding, check they're warm enough, check they've got a cup of tea and just keeping an eye on what's going on. There's nothing better than managers around. I'm not an office manager, I think it is great to be hands-on out on the floor.’ – Nurse Manager 5

‘When the staff knows we are busy and the nurse manager comes and helps … they will stay. Or if they say she or he just remains in the office, we are having all the tasks to ourselves, they will burn out. They will go.’ – Nurse Manager 9

‘Yes, in fact this is what they told me. “Miss at least you come out and help us but in the past, we didn't have that.” I've been always like that, you know. … I go round, I assess the situation every day. If they are really hectic, I try to help.’ – Nurse Manager 14

‘I always say I will never leave my staff working out on their own. Yes, you need the time to do paperwork or whatever, but still, it is necessary to support nurses outside. Given the shortage of nurses, I can't say leave one nurse outside and I am sitting in the office myself. Staff out there [are] dealing with all the activities … and so I must give them support.’ – Nurse Manager 23

A more extreme example of positive deviance in the form of fostering positive relationships was recounted by Nurse Manager 9 who was confronted with a potential staff resignation. In this case, Nurse Manager 9 was approached by a nurse, who explained that for family reasons she was unable to continue to do night shifts and was considering resigning from the service. Nurse Manager 9's response was, ‘Please don't quit!’ Nurse Manager 9 explored day shift roles within the organisation and when a suitable vacancy was identified, the Nurse Manager went the ‘extra mile’ to refer the nurse to that unit Nurse Manager. Finally, after the recruitment and transfer formalities, the nurse was employed in the new position and retained in the service. This exceptional nurse manager behaviour was over-and-above what would have been expected, but because of the concern for retention of nurses in the service, Nurse Manager 9's actions led to the nurse staying.

This story supports Nurse Manager 9 as an employee champion in seeking alternative options to retain the nurse in the profession. Rather than operate in a silo as the work system in this organisation dictates, Nurse Manager 9 embarked on a series of actions and decisions to render a positive outcome for the nurse, but more importantly for the profession and the organisation in retaining the services of this nurse. This approach demonstrates positive leadership in action, and the impact of Nurse Manager 9 taking on an employee champion role (Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1997).

Positive climate

Fostering a positive climate involves the practice of compassion, forgiveness, and expressions of gratitude in the workplace (Cameron & Wooten, Reference Cameron and Wooten2009). Facilitating an environment and work climate that supports compassionate behaviours over and above technical performance in managing patient care featured in a number of nurse managers' stories. The technical performance of nurses is measured and audited regularly. In a number of scenarios, however, Nurse Manager 2 shows how a positive climate that includes both technical care but more importantly, compassion and nurturing, is leading to positive outcomes for both patients and staff.

Nurse Manager 2 is able to create a sense of belonging, a safe environment where staff feel valued and appreciated, and are able to approach Nurse Manager 2 if they face any dilemmas or have concerns. Nurse Manager 2 identifies fear and anxiety as emotions to be managed effectively, to ensure patients feel safe or staff are reassured if in doubt. For example, ‘I'm frightened, but I felt loved.’ Nurse Manager 2's emotional intelligence and awareness of the positive impact of creating a safe and secure environment contributed to nil staff turnover on the ward. This focus on the human element of the healthcare service is vital and recognises the provision of quality patient care going beyond quality clinical care.

Vignette 3

‘But for me, it is trying in my behaviour to demonstrate to people that the most important reason that we are here is to give great care to our patients… The technical care is straightforward. You can teach anyone to do anything. We measure that and we audit that … . Patients part of experience…. what they do experience is the way the staff interact with them. So if patients can leave here feeling that [loved, warm, safe], then they go out and tell people that this is a lovely place and more come [return business]…’ – Nurse Manager 2

‘Everyone wants to be treated nicely, they want to be treated fairly. It is the usual human resources one-on-one: acknowledge me, support me, praise me, love me, hold my hand when I am feeling stressed … it is all of that whether they're young or whether they're less young.’ – Nurse Manager 2

Positive communication

Engaging in positive communication requires replacing negative language with encouraging and supportive language and ‘collect[ing] reflected best-self feedback’ (Cameron & Wooten, Reference Cameron and Wooten2009: 5). Across the interviews, nurse managers used a combination of positive reflection, including spiritual reflection, and leading by example to create opportunities for positive communication, which lead to positive outcomes. The stories in Vignette 4 provide evidence of positive deviance, where problematic issues can be addressed using supportive and positive communication strategies. Team reflection and team staff consultation provide the opportunity for teams to meet, to be guided through a team reflection, and facilitated discussions about what went wrong and how to improve the situation, producing positive outcomes.

Vignette 4

‘Anyway, on Fridays … we usually meet … to discuss … sometimes during morning reports or afternoon reports. If a situation has arisen, we reflect on it and we identify our faults, and how we can improve. I think it is working well. Because there are incidents that sometimes occur and truly we realise it is our fault at times whereby we could have done better and we reflect on it.’ – Nurse Manager 23

‘They [the staff] feel at ease because they can voice out. Because what happens, you don't always get an opportunity to organise a meeting, to join as a group to have a meeting. However, there are occasions whereby nurses we can join, or I am able to meet the nursing staff. We discuss issues that happen and how we can fix them.’ – Nurse Manager 23

‘An employee shared the organisation policy and procedures guidelines with a friend external to the organisation. The Nurse Manager 18 explained, “they told me they are going to sack [the staff]. I said I think it's a first mistake. [The staff] didn't do it purposely and then I said, …. I thought [this is] sharing best practices? Then they said they've got copyright on [the guidelines]” which the staff was aware of in the employment contract.’ ‘I talked to [the staff] who wanted to cry; [the staff] came to me and said M'am please talk on my behalf because I don't want to [leave the organisation] with a [damaging employee certificate] so they accepted to ask him to resign.’ – Nurse Manager 18

Nurse Manager 18 describes an offense of a serious nature. Ordinarily, such an issue results in suspension pending investigation. In this scenario, Nurse Manager 18 uses the mistake as a learning opportunity and a way of retaining the nurse in the workforce. Despite the conflicts that existed between the contractual arrangements, human resource policies, the staff and the severity of the offense, Nurse Manager 18 had the inner confidence to use this situation as a learning opportunity and challenged the normal outcome. Whilst a risky decision, Nurse Manager 18 obtained a successful outcome – the staff was able to resign from the organisation but was retained in the profession.

The vignettes presented above, centre on nurse managers practising positive leadership and facilitating positive work strategies to change behaviours and outcomes. In these vignettes and from the many other nurse managers' stories within the sample, positive deviant behaviour, and outcomes, are necessitated by the constant balancing between clinical and operational demands, or between operational and strategic requirements, or between administrative and strategic imperatives. The ability of these nurse managers to manage these multiple frictions shows a high degree of resilience, compassion, agility, determination, and drive. It also demonstrates their vision and focuses on positive outcomes, be it staff, patient or organisational outcomes and their ability to create positive meaning in the workplace, build positive relationships, foster a positive climate, and encourage positive communication.

Discussion

Through the application of a bespoke interpretive framework, the outcomes of this study support the incidence of positive deviance in healthcare. This study evidences how these occurrences of positive deviance manifest in the workplace to positively influence nursing outcomes, determined through the nurse manager stories that were flourishing with positivity and excellence, despite the circumstances and situations being predominantly demanding, difficult, challenging, and even risky. Very often, these challenges were in conflict with one another. Yet these stories demonstrate what Carper (Reference Carper1978: 31) explains as: ‘the obligation to care for another human being involves becoming a certain sort of person – and not merely doing certain kinds of things’.

Through acts of positive deviance, there was unequivocal evidence that nurse managers in this study are striving to achieve excellence within their units or wards. These positive work practices were mechanisms by which positive deviance manifested. Nurse managers were very clear about the priority of providing quality healthcare to their patients. Across the positive deviance scenarios, nurse managers explicitly verbalised the requirement to deliver quality patient care, patient safety, and security. They operationalised various positive work practices including marshalling resources to bring about transformation; confronting issues that were a barrier to successful outcomes; finding alternative approaches to addressing problems and weaknesses; and promoting new ways of doing things in order to mobilise positive work outcomes. These positive strategies focused on care (for their staff as well as their patients), compassionate support, forgiveness, and fostering meaningful work; all of which have been shown to influence positive individual outcomes (Cameron, Mora, Leutscher, & Calarco, Reference Cameron, Mora, Leutscher and Calarco2011; Heidari, Seifi, & Gharebagh, Reference Heidari, Seifi and Gharebagh2017).

The examples of positive deviance in this study support that nurse managers take on multiple roles in order to facilitate these positive strategies. Most often, nurse managers are considered to be the administrative expert focusing on managing staff workloads to achieve patient outcomes with limited resources. Pinkerton (Reference Pinkerton2003: 45) found nurse managers spent between 27–79 h a week (average 41 h) on administrative tasks, and were responsible for an average of 83 employees (ranging between 23–215 employees). This equated to .9 full time employment of an Operations Assistant. Across the positive deviance examples, however, there was evidence of the nurse manager ‘champion’ – a nurse manager who when compared to their peers in the same environment and working under the same conditions, displayed exceptional performance and success in their role (Herington & van de Fliert, Reference Herington and van de Fliert2018: 666). This champion role is supported by other literature (see Smith, Lewis, & Tushman, Reference Smith, Lewis and Tushman2016; Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1997). In order to be successful champions however, in this study the nurse managers also operate strategically to create a positive organisational climate that focused on both strategic and operational imperatives. Such a climate has been shown to bring about positive individual and organisational outcomes (Blake, Leach, Robbins, Pike, & Needleman, Reference Blake, Leach, Robbins, Pike and Needleman2013; Pearson, Laschinger, Porritt, Jordan, Tucker, & Long, Reference Pearson, Laschinger, Porritt, Jordan, Tucker and Long2007).

While nurse manager roles align with those presented by Ulrich (Reference Ulrich1997), positive deviance results support nurse managers to operate in roles with a multi-layered focus and can effectively balance strategic and operational tensions as well as process and people goals. In this study, the deviant nurse manager weaves between these leadership approaches and activities in order to achieve positive outcomes. Ulrich et al. (Reference Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich and Brockbank2017: 53) describes this type of leadership as ‘navigating the paradox’, a feature of positive leadership and the ‘next wave in the evolution of leadership effectiveness’ (see also Leslie, Li, & Zhao, Reference Leslie, Li and Zhao2015). The deviance in challenging the procedures to influence and steer a resolution against the norm is reflective of successfully engaging with exigencies within the work environment.

In this study, nurse managers apply positive leadership strategies, intentionally confronting the challenges and taking appropriate action to attain a positive resolve (Johnson, Reference Johnson2014; Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2012) even if it required they step out of their substantive roles. Ulrich et al. (Reference Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich and Brockbank2017: 57) state ‘paradox navigation is not an innate trait, but a learned set of behaviours that translate into skills’. Through training and development opportunities, these skills can be attained. In their study of 4,000 Human Resource participants and 28,000 associate raters, Ulrich et al. (Reference Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich and Brockbank2017) identified a set of ten behaviours related to specific skills for managing paradoxes in the workplace. This has significant implications for the professional development of nurse managers and the role of training and development in positive leadership in healthcare.

Conclusion

This research addresses the call for the ‘study of positive outcomes, processes, and attributes of organisations and their members’ (Cameron, Dutton, & Quinn, Reference Cameron, Dutton, Quinn, Cameron, Dutton and Quinn2003: 3) deemed valuable in the context of healthcare (Fulop et al., Reference Fulop, Dadich, Ditton, Campbell, Curry, Eljiz and Smyth2013). The interview data supported that positive leadership strategies and practices which facilitated meaningful work, relationships, positive climates, and supportive communication, can impact organisational and individual outcomes. More importantly, however, it was not the interventions alone that brought about positive impacts, but rather the positive leadership that led to the development and implementation of those interventions which influence organisational outcomes.

Nurse managers exhibit positive leadership behaviours and act as positive leaders to navigate the paradox experienced in their roles (Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Kryscynski, Ulrich and Brockbank2017). The nurse manager stories revealed that they understood that they ‘operate within a world of contradictions’ and imply that they have utilised a paradox mindset to generate positivity, ‘gain[ing] new insights and discover[ing] other aspects of a situation’ (Farrell, Reference Farrell2018: 171). Future research, which explores the paradox mindset phenomena as a way to better understand positive deviance, is warranted.

While many studies have identified that leadership styles impact work outcomes, this study shows that it is positive leadership behaviour in the form of embracing and effectively understanding competing demands that has a substantial influence on a positive work environment. This is a significant contribution to better understanding of the prevalence of POSH.

Furthermore, this study employed a unique methodology, using nurse manager stories to operationalise incidents of positive deviance in healthcare. Stories have been identified as important in making sense of ‘…complex context-based issues’ (Dawson, Farmer, & Thomson, Reference Dawson, Farmer and Thomson2011: 159). The application of a bespoke interpretive framework addresses some of the limitations associated with the validation and interpretation of positive deviance (Dadich et al., Reference Dadich, Collier, Hodgins and Crawford2018). It would be useful to evaluate the efficacy of such an approach in future studies exploring incidences of positive deviance, whether they be in healthcare or other settings. It may also be worthwhile comparing and contrasting the application of this framework to others, such as that presented by Fulop, Kippist, Dadich, Hayes, Karimi, and Symth (Reference Fulop, Kippist, Dadich, Hayes, Karimi and Symth2019: 591), in evaluating the effectiveness of new ways to ‘examine, understand and promote positive organisational experiences’.

While the research has focused on positive behaviours and outcomes, it is important to remark that there were incidences of what might be considered undesirable management practices evident in the nurse managers' stories. Future research, which compares and contrasts the leadership approaches of positive and negative deviants, may provide greater insight into how leaders confront tensions as they become the norm in the future world of work.

Sandra Crewe is currently a doctoral candidate at the Murdoch Business School, Murdoch University, Western Australia. Sandra's research focuses on leadership in the healthcare services, with a specific interest in nursing leadership. As a Human Resource practitioner in the public sector, she has a passion for people development.

Antonia Girardi is an Associate Professor in the area of people management in the Murdoch Business School at Murdoch University. Antonia has worked on various national research projects and consultancies focussing on work-related issues within the Western Australian Health Services Sector.