Introduction

In Johannes Ewald’s epic poem, The Death of Balder (1773), heroine Nanna rails against useless conflict and male bellicosity. Balder loves Nanna; Nanna loves Hother; Hother wants to fight Balder for honor’s sake; Nanna would only suffer from Hother’s “heroic” death. This 250-year old poem highlights an essential truth about the cultural underpinnings of Danish labor market cooperation—conflict is a waste of time. How different is the message in “No Enemies” by Charles Mackay, who urges workers to fight the good fight: “You have no enemies, you say? Alas, my friend, the boast is poor. He who has mingled in the fray of duty that the brave endure, must have made foes. If you have none, small is the work that you have done.”

Fiction writers and messages imbedded in their work about conflict and coordination have implications for the central question of this paper: why did some countries (e.g. Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) develop institutional capacities for industrial coordination, while others (Britain) remained mired in class conflict? Coordinating countries ultimately produced full-blown macro-corporatist industrial relations systems with encompassing employers’ and labor organizations, tripartite channels for social partner engagement with government policy-making, and industrial cooperation for skills development.Footnote 1 Britain created a pluralist, fragmented industrial relations system with limited labor market cooperation.

Origins of cooperative versus conflictual labor market institutions remain a topic of much dispute, and two theories about radicalism versus reformism particularly concern us. One theory suggests that coordinated countries have stronger preindustrial cooperative institutions (guilds) and norms enabling early consensual engagement across class divisions [Thelen Reference Thelen2004; Cusack, Iversen and Soskice Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007]. Another, power resources theory, suggests that coordinated institutions are forged through the fires of labor radicalism [Lipset Reference Lipset1983; Korpi Reference Korpi1980; Stephens Reference Stephens John1979; Paster Reference Paster2011]. These theories predict differences in how values manifest in preindustrial corporatist and pluralist countries. The preindustrial-institutions approach suggests that future corporatist countries should have norms of cross-class cooperation, valued skills, and a government role in labor relations long before full-blown industrial coordination emerges. Power resources theory implies the opposite: future coordinated countries should have strong class identities, sharper class cleavages and higher levels of radicalism that enable strong labor movements to wrest power away from business and secure institutions for labor market coordination [Lipset Reference Lipset1983].

This paper explores cooperative norms in future liberal and coordinated countries by exploring depictions of labor in literature in 18th and 19th century Britain, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. We suggest that cultural actors matter at two levels, and we acknowledge both structure and agency in the mechanisms by which cultural actors contribute to institutional change. First, authors act collectively (and sometimes subconsciously) to frame labor issues in light of their nation’s literary heritage. As a group, authors in each generation inherit cultural tropes from past literature; they rework these symbols and narratives to address contemporary problems and to reflect on collective identities, class cleavages, and preferences for cooperation or conflict. Cultural tropes include messages about the value of workers, cooperation versus competition, skills development and the role of the state. Because these symbols and narratives are recursive and repeating, they help to explain long-term continuities in views toward labor even at moments of paradigm shift or discontinuous institutional change. While cultural depictions of labor are not the impetus for political battles and negotiations, they act as an intervening variable that sets context for industrial system development. Cultural works influence preferences of economic actors for cooperation and affect the salience of social cleavages [Spillman Reference Spillman, Alexander, Smith and Jacobs2012; Beckert and Bronk Reference Beckert, Bronk, Beckert and Bronk2018; Fourcade Reference Fourcade2011].

Second, some authors work individually in political struggles to frame labor problems and industrial relations solutions. While the structure of cultural tropes helps to shape preferences for new directions in industrial relations policy, this process is neither automatic nor deterministic. Authors sometimes mobilize public support for their views, legitimize their allies’ approach, and may build linkages among class factions. Thus, we show (admittedly briefly in this paper) how cultural agents mobilize cultural scripts to support political allies.

We explore theories of industrial system development by considering depictions of labor in large corpora of literature in Britain, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. We hypothesize that if the preindustrial coordination theory holds, Danish, Dutch and Swedish authors (dating back to 1700) should depict labor with similar cultural tropes (narratives and symbols); these tropes should differ from British authors’ depictions. Authors in the coordinated countries are more likely to associate labor with references to cooperation, skills and the state than those in liberal Britain. We analyze large corpora of literature with computational text analyses to test for significant, cross-national differences in the cultural depictions of labor. Our corpora consist of all works available in full-text files between 1700 and 1920 for Denmark (522), Sweden (411) and the Netherlands (296) and a large sample of works drawn from online lists for Britain (562). Our findings confirm the preindustrial coordination hypotheses: snippets of text surrounding labor words in literature from the coordinated countries had much higher frequencies of words associated with cooperation, government and skills than did snippets surrounding labor words in British literature. Our space-constrained case studies document how British, Danish, Dutch and Swedish authors repeated narratives over hundreds of years and engaged in struggles over industrial relations system development.

The paper strikes new ground with an empirical method to evaluate historical attitudes toward labor. Critics charge that it is difficult to falsify cultural arguments or to assess the specific contribution of cultural depictions to political development [e.g., King, Keohane, and Verba Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994: 36-41; Coppedge Reference Coppedge2012: 228-237]. Cultural arguments are sometimes tautological, in that they use the object of explication—differences in policy outcomes—to defend cultural assertions. Moreover, it has been difficult in the past to assess the prevalent values of the 18th and 19th centuries that predate labor mobilization, and our methods allow us to do this. Our method for operationalizing and testing cross-national cultural differences within very large corpora of literature allows us to consider how cultural actors reflect on labor, make predictions about cross-national differences, and test our hypotheses.

The paper also contributes to our understanding of the processes by which writers influence the expression of social cleavages [Spillman Reference Spillman, Alexander, Smith and Jacobs2012]. Nations vary in the salience of economic, religious, and ethnic cleavages [Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Manow and van Kersbergen Reference Manow, van Kersbergen, van Kersbergen and Manow2009; Oude Nijhuis Reference Oude Nijhuis2013]. They also differ in the sharpness and violence of divisions, revolutionary impulse, relative exclusion of marginal groups, and distance between rulers and opposition. Cultural touchstones influence societies’ predilections for cooperation and conflict.

Finally, our approach addresses intra-model similarities and differences among varieties of capitalism. Shared cultural tropes shed light on why Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden—with radically different industry profiles and historical trajectories of industrialization—have similar coordinated industrial relations systems. Yet subtle differences exist in the cultural touchstones of the coordinated countries, and these provide clues to somewhat different paths to coordination. As predicted, references to coordination are significantly higher in the three future corporatist countries than in Britain except for Sweden from 1820-70. Yet when we exclude terms such as “federation” that refer specifically to groups (as opposed to the other dimensions of coordination), Sweden has fewer references to cooperation than Denmark or the Netherlands. This suggests (and our qualitative investigations confirm) that a power resources argument works better in Sweden than in the other two coordinated countries. This is consistent with Lipset’s [Reference Lipset1983: 5] claim that Denmark has one of the most moderate labor movements in Europe. Moreover, the Netherlands, with its more commercial economy, has much higher frequencies of market words and lower frequencies of skill words than the other coordinated countries. Finally, while the three coordinated countries have significantly higher frequencies of government words for most periods, the state in Dutch labor relations takes off in the late 19th century at a point at which Denmark developed mechanisms for industrial self-regulation among the social partners [Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012]. Various paths lead to coordinated labor market institutions, as workers, employers, bureaucrats and authors struggle to find meaning in the dynamics of socioeconomic change.

Diverse Categories of Industrial Relations Systems

Scholars classify postwar industrial relations systems into two or more groupings. For Hall and Soskice [Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001], liberal market economies (LMEs) and coordinated market economies (CMEs) each have a distinctive industrial relations system [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Estevez-Abe, Iversen and Soskice Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001]. Such industrial relations systems have been labeled pluralist and macro-corporatist, and some add a third level of sectoral coordination [Schmitter Reference Schmitter and Berger1981; Crouch Reference Crouch1993; Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012].

We focus on three dimensions with respect to which industrial relations systems vary: the characteristics of industrial groups, their incorporation into public policy-making processes, and types of skill formation. First, coordinated/corporatist societies have encompassing, centralized and consensus-oriented national employers’ and workers’ associations, while pluralist systems have weak and decentralized associations. Collective bargaining tends to be more centralized and cooperative in corporatist than in pluralist countries, and unions express policy preferences that extend to workers beyond their own membership [Schmitter Reference Schmitter and Berger1981; Stephens Reference Stephens John1979].

Second, corporatist/coordinated systems integrate “social partners” into state-sponsored tripartite commissions to form policy; whereas pluralist systems lack these extra-legislative forms of policy-making [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012; Oude Nijhuis Reference Oude Nijhuis2013]. Coordinated market economies consequently presuppose consensual, cooperative relations among classes in political processes and recognize state legitimacy, whereas liberal market economies presuppose higher levels of class conflict.

Third, coordinated countries, often with open economies, bolster their skills to compete in global markets with significant human capital investments, rather than developing protections against trade exposure. Liberal countries historically develop Fordist manufacturing processes using semi-skilled labor, and are more likely to produce for domestic markets [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Cusack, Iversen and Soskice Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007]. [See Table 1 in Online Appendix.)

Industrial relations systems were fully formed after WWII, yet industrial unions and employers’ associations emerged during the 19th century, and peak associations and courts for labor disputes developed around the turn of the 20th century [Crouch Reference Crouch1993; Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012]. Employers and workers were incorporated into public policy-making processes even earlier; for example, Danish, Swedish, and Dutch peasants participated actively in the implementation of land reforms in the 18th century. Education and skills have deeper roots in coordinated market economies than in their liberal counterparts [Martin Reference Martin2018].

Theories About Industrial Relations Systems

Coordinated and liberal governments created different types of labor market institutions, and our puzzle is to understand differences in strategic choices. Scholars commonly acknowledge that the broad timing of industrialization drove the emergence of labor market institutions at the end of the 19th century [Gerschenkron Reference Gerschenkron1962; Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1986]; yet the industrial structure of national economies does not predict coordination among our cases as Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden had very different economies. While Britain and the Netherlands were early developers of capitalism, industry came late to Denmark and Sweden. The Netherlands led in commercialization and urbanization, and with industrialization, Denmark developed small and medium-sized firms while Sweden developed large corporations [Bairoch and Goertz Reference Bairoch and Goertz1986]. Country size seems to accord an advantage to would-be coordinators. (See Table 2 in Online Appendix.)

Political institutional structures also provide some insight into choices of coordination and conflict. Party systems shape the expression of preferences among labor market actors for conflict versus coordination in industrial negotiations. Electoral systems mediate groups’ political strategies: proportional systems are associated with coordinated industrial relations systems and majoritarian systems are associated with pluralist industrial relations systems [Crouch Reference Crouch1993; Boix Reference Boix1999; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Swenson Reference Swenson2002; Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012; Cusack, Iversen and Soskice Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012]. Yet this argument does not account for the roots of cooperation and conflict that predate electoral and party systems.

Scholars also offer two theories of the impacts of preindustrial labor relations (and attendant cultural norms) on later industrial relations system development. A power resources perspective suggests that the organizational density and structure of the labor movement shape the development of industrial relations systems. Strongly organized unions and parties representing workers achieve concessions from employers and are accorded considerable input into industrial policies and management [Korpi Reference Korpi1980; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Paster Reference Paster2011]. Lipset [Reference Lipset1983: 2] suggests that preindustrial status groups or stands create a shared corporate identity within classes and greater labor radicalism. This explanation fits well with events in Sweden, where 19th century Swedish elites used coercive labor market arrangements to depress wages and ensure profits for landowners and capitalists. The mobilization of the working class upended this coercive relationship and brought about higher levels of labor market coordination [Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson2019; Uppenberg Reference Uppenberg and Whittle2017]. Yet, while Denmark had serfs until 1788, the stands in both Denmark and the Netherlands contributed to more pragmatic, moderate labor politics. Religious cleavages, moreover, famously inhibit the emergence of a shared class identity and capacities for coordination [Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Manow and van Kersbergen Reference Manow, van Kersbergen, van Kersbergen and Manow2009]. Yet in our cases, the Netherlands achieved coordination despite a strong religious cleavage whereas the other three countries had a state church with a strong presence of dissenting sects.

Other scholars suggest that coordinated countries have much stronger preindustrial institutions and norms of cooperation than liberal countries and that during industrialization, these norms permit cooperative industrial relations institutions. Preindustrial labor market institutions such as guilds create assumptions about patterns of cross-class cooperation, as employers develop shared interests with labor in a production strategy relying on a skilled workforce [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Thelen Reference Thelen2004; Cusack, Iversen and Soskice Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007]. The consensual nature of Dutch policy-making is often attributed to norms and institutions that developed in the pre-modern era [Prak and Van Zanden Reference Prak and Van Zanden2013; Prak Reference Prak, van Gerwen, Wals, Seegers and van Tielhof2014]. The Netherlands, however, abolished guilds earlier than Britain, indicating that cooperative norms did not rely solely on such institutions. Moreover, while the Danish manorial system created legacies for agricultural cooperation before industrialization [Sundberg Reference Sundberg, Sundberg, Germundsson and Hansen2004], the Swedish state regulated the agricultural labor market and stipulated relations between small holders and owners [Uppenberg Reference Uppenberg and Whittle2017; Utterström Reference Utterström1962].

We believe that both power resources and preindustrial institutions and norms contribute to industrial relations system development; yet we recognize that these explanations suggest different predictions about cross-national differences in perceptions of labor found in societies before the emergence of corporatism and pluralism at the end of the 19th century. A power resources approach would lead us to expect that future coordinating countries should have lower levels of cooperation before labor activism wrests power away from business [Lipset Reference Lipset1983]. A view emphasizing cooperation among preindustrial institutions would predict that centuries-old cultural distinctions separate coordinated countries from liberal ones [Østergård Reference Østergård1992; Stråth Reference Stråth2004, Reference Stråth, Synnøve, Bringslid and Vike2017; Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane1973; Macpherson Reference Macpherson1962].

We propose to compare the language describing labor in liberal and coordinated countries in order to shed light on these diverse views of the normative underpinnings of coordinated countries. But first we must develop a theory of how cultural depictions are brought to bear on choices in the development of labor market institutions.

A Cultural Model of Influence on Industrial Relations

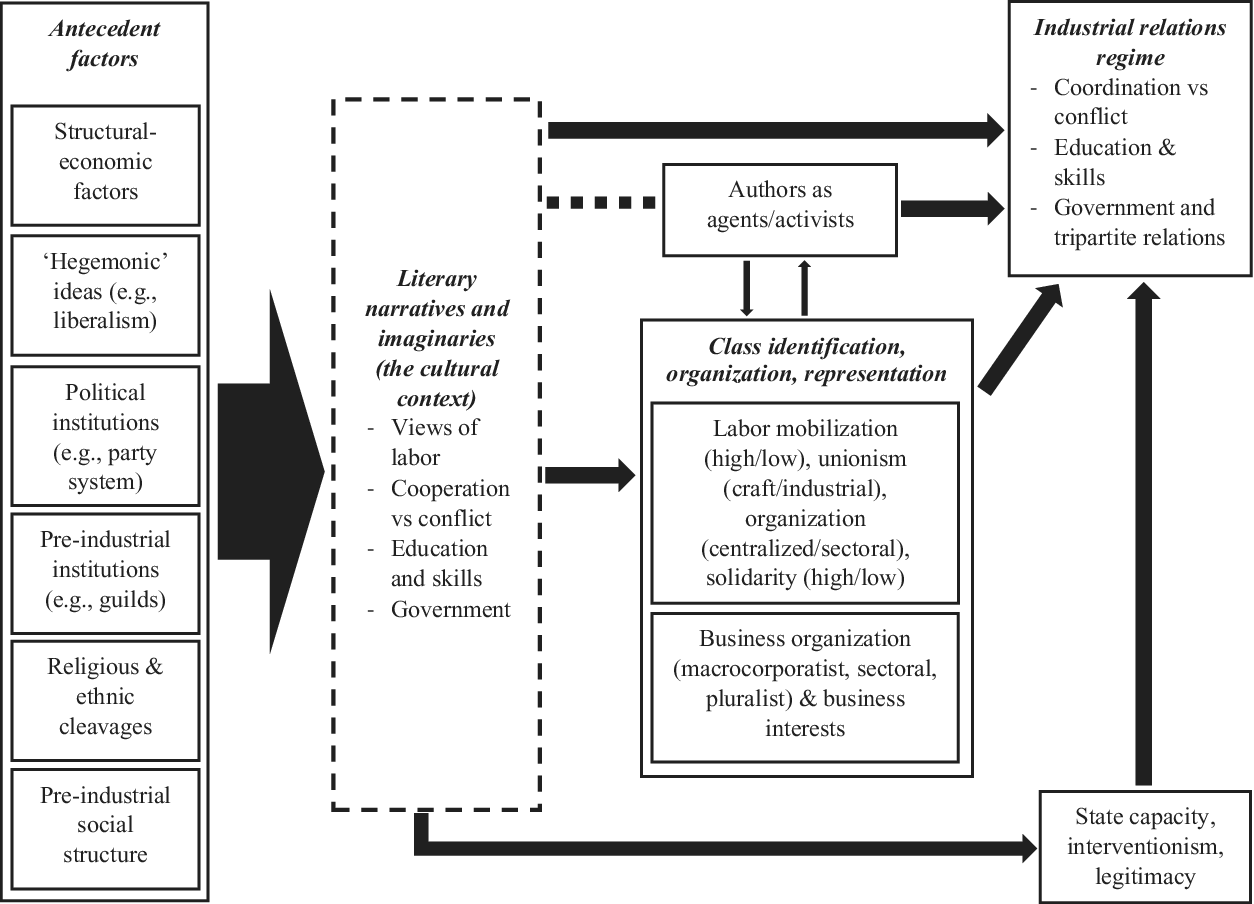

We offer a dynamic model of industrial relations system development, in which cultural depictions help to set the context for struggles among social actors. Significant economic transformations broadly inspire the construction of labor market institutions; however, diverse industrial structures may choose coordination over conflict in industrial relations institutions. Paradigm shifts in the prevailing hegemonic ideas, such as the move from laissez-faire liberalism in the mid-19th century to the search for order in the late 19th century, also inspire new forms of industrial relations. Coalitions of actors lobby for their preferred resolutions to industrial conflict: labor power, business organization and party structures matter to these choices. Yet actors’ expression of preferences and the outcomes of political struggles are influenced by cultural norms as well as by power relations. Sometimes authors become activists in political coalitions and have special relevance in framing problems, popularizing solutions for mass consumption and legitimizing power relations. Thus choices in industrial relations system development reflect both coalitional struggles and the cultural interpretation of new paradigms about industrial relations. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1 Cultural Model of Influence on Industrial Relations

To grasp precisely how cultural values set the context for choices in industrial relations systems, we turn now to our theory of culture in political change processes. Cultural sociologists recognize that cultural-cognitive systems (or symbolic elements together with social practices and material resources) constitute a core component of institutions [Scott Reference Scott2001: 48-51]. Cultural-cognitive systems provide a source of frames for ascribing meaning and interpreting the social world [Scott Reference Scott2001: 57-58]. Our ambition is to further stipulate how (and whether) cultural elements are transmitted from one generation to another, mobilized in specific historical contexts, observed independent of the institutions in which they are embedded, and exist independently from the policy legacies that reinforce institutional continuities. We suggest symbolic elements appear in the work of cultural actors such as authors [Griswold and Wright Reference Griswold and Wright2004] and that these cultural artifacts are somewhat independent from political, economic and social institutions. This somewhat independent source of cultural artifacts allows us to measure cultural inputs over time, to trace the ways that these artifacts are mobilized in specific policy struggles and to evaluate cross-national differences and similarities in cultural depictions.

We posit that cultural actors may engage with industrial relations system development at two levels: the structural level of the “cultural toolkit” (symbols and narratives) specific to a national literature and the individual level of agency. At the structure level, each country has a “cultural toolkit” (norms, symbols and narratives) that actors use to ascribe meaning and develop solutions to problems [Swidler Reference Swidler1986: 273-276]. The toolkit includes “repertoires of evaluation,” or scripts that define positives and negatives, and draw boundaries between groups [Lamont and Thévenot Reference Lamont, Thévenot, Lamont and Thévenot2000: 5-6]. The heterogeneous cultural toolkit cannot predict specific choices; however, symbols, narratives, and repertoires of evaluation are unevenly distributed across countries and citizens in one country are more likely to access specific cultural tools than citizens in others [Ibid.: 5-6]. Cultural scripts or “imaginaries” help to organize economic action and markets [Beckert and Bronk Reference Beckert, Bronk, Beckert and Bronk2018: 4]. The national level aggregation of symbols and narratives persists through time in literature (as well as in other cultural forms). The cultural lens differs from more transitory social and economic paradigms that periodically gain credence across countries, but the cultural toolkit facilitates the translation and adoption of paradigms into culturally-specific national solutions [Blyth Reference Blyth2002; Ban Reference Ban2016].

Fiction writers constitute a mechanism by which the cultural toolkit is transmitted from one generation to the next. Authors act collectively as purveyors of cultural symbols and narratives, and draw upon cultural artifacts inherited from the past to depict new challenges and solutions [Martin Reference Martin2018]. Authors define political, economic and social issues in culturally-specific ways; the collective voices and silences of the corpora transcend the agency of individual writers [Williams Reference Williams1963; Guy Reference Guy1996: 71; Poovey Reference Poovey1995]. Familiar touchstones inform the “political unconscious,” (or gap between authors’ intended goals and their subtext messages) that is unacknowledged by the text [Jameson Reference Jameson1981]. Kipling recognizes the power of the national corpus when he writes: “The magic of Literature lies in the words, and not in any man […] a bare half-hundred words breathed upon by some man in his agony […] ten generations ago, can still lead whole nations into and out of captivity” [Kipling Reference Kipling1928: 6].

Other influences besides inherited symbols and narratives matter to authors’ interpretation of political and social problems. Authors write about their “real world” experiences, and their depictions reflect the core values of their societies, assumptions about political engagement, patterns of class conflict, religious beliefs and norms of political institutions. Cultural sociologists, however, strongly denounce the idea that authors’ works merely “reflect” life and structural preconditions [McDonnell et al. Reference Mcdonnell, Bail and Tavory2017]. Cultural expectations co-evolve with—and reinforce or undermine—social, economic, and political institutions. While great authors shape new directions in fiction [Gravil Reference Gravil and Gravil2001], even the most original writers draw from national literary traditions in constructing their narratives. Cross-national differences in literary depictions of labor predate the invention of many capitalist and democratic institutions such as political parties, labor unions, and employers’ associations. The sweeping bird’s eye view reveals enduring cross-national differences in views of labor.

At the level of agency, writers were (often neglected) political actors in specific policy struggles and they marshalled cultural tropes in historically-contingent ways to support new political agendas [Berezin Reference Berezin2009]. Fiction writers contributed to the cognitive framing and the emotional salience of social problems, and they were particularly influential in pre-20th century debates before the explosion of mass media. They historically joined other intellectuals as the avant-garde in putting neglected issues on the political agenda. Fiction offered a crucial medium for intellectuals to debate issues, to shape public consciousness, and to influence rulers [Keen Reference Keen1999: 33]. Granted, authors used cultural tools either to legitimize or challenge the status quo; moreover, domains had contradictory logics and groups competed over national identities. Yet some writers joined coalitions to win policy battles and particularly to develop narratives to legitimize claims for political power [Poovey Reference Poovey1995: 15; Keen Reference Keen1999: 2].

Cultural work has bearing on the construction of collective social identities and class cleavages. Narratives and symbols convey expectations about the psychological articulation of “self,” the relationship between individual and society, conformity to the social order and collective identities [DiMaggio and Markus Reference DiMaggio and Markus2010: 351; Griswold and Wright Reference Griswold and Wright2004; Polletta et al. Reference Polletta, Chen, Gardner and Motes2011; Korsgaard Reference Korsgaard2012]. Cultural production influences views of economic actors on norms of economic exchange [Beckert and Bronk Reference Beckert, Bronk, Beckert and Bronk2018; Spillman Reference Spillman, Alexander, Smith and Jacobs2012: 159; Fourcade Reference Fourcade2011]. Novels’ depictions may politicize or demobilize marginal groups, and stories of resistance become crucial weapons in movement mobilization [Swidler Reference Swidler1986; Lamont and Thévenot Reference Lamont, Thévenot, Lamont and Thévenot2000; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey2003].

Certainly, there is also a reciprocal impact of power relations on cultural development, because dominant interests give preference to certain cultural voices. Power relations influence the ways in which ideas are organized and transmitted to the public. This organization has a powerful impact on the translation of new ideas about industrial relations during periods of paradigmatic change [Morgan and Hauptmeier Reference Morgan and Hauptmeier2021]. Although the barriers to publishing were lower in the 18th and 19th centuries, publishers gave a platform to chosen authors [Altick Reference Altick1986]. (See Online Appendix.) Moreover, social movements may influence the emergence of new genres, as one finds with the American labor problem novel [Isaac Reference Isaac2009]. Yet one may see a continuity in characteristics of cleavage formation—the strength of antagonisms and distance between core and peripheral groups—across epochs of industrial relations.

On causality, we do not argue that cultural actors and artifacts have a causal impact on the development of coordinated and liberal industrial relations systems; material interests are clearly crucial to these processes. But with our cultural quantitative evidence, we can verify cross-national differences in cultural depictions of labor and show that these correspond to cross-national variations in industrial relations development. Thus, we can disprove the null hypothesis that culture does not matter. Moreover, following Falleti and Lynch’s [Reference Falleti and Lynch2009] model of context in causal processes, we view cultural artifacts as a part of the “context” of policy-making. Culture, in our model, does not have an independent causal effect; but it structures how other factors influence industrial relations system development. (See Figure 1.) This is similar to how public opinion structures the effect of political parties [Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020]. Thus, we suggest an “effects-of-causes” rather than a “causes-of-effects” approach, by stressing the relevance of a factor without claiming that it fully explains the outcome [Martin and Chevalier Reference Martin and Chevalier2021; Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2006].

Methods

We use two methods to substantiate our claims. First, our quantitative analysis uses computational linguistic and machine learning techniques (in Python) to systematically test observable differences in corpora of British, Danish, Dutch, and Swedish novels, poems and plays between 1770 and 1920 (after which copyright laws limit access). We choose Britain, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden because we wish to include both coordinated and liberal market economies. The lists of fictional works in the corpora were compiled from country collections of national literature (e.g. the Archive of Danish Literature) and from online lists of important works and authors from the 18th to early 20th centuries. Full text files are provided by national archives and HathiTrust, and virtually all works with available full-text files were included in our Danish, Dutch and Swedish collections. For the British corpus, we included all of the volumes on internet lists of 18th, 19th and early 20th century works, and augmented this with works of authors listed as representing this period. Because available full-text files are often not first editions, we manually alter the dates of works to reflect their initial publication. The timing of publication is crucial for establishing the sequential relationship between cultural artifacts and reform moments. (See Online Appendix for methods discussion.)

We recognize that some biases exist both in the initial publication of works (i.e. upper class and male authors find it easier to be published) and in the lists of works considered important centuries later; however, we avoid adding to these biases by deferring to expert judgments about the collections. For the British corpus, where some choices were made, we included works that were highly influential at the time but are less famous today.

We hypothesize that if distinctive literary depictions are associated with choices in industrial system development, we should find cross-national variation in the cultural scripts of large corpora of national literature that correspond to our predicted differences in the evolution of industrial systems. We build snippets of 50-word texts around words that reference the concept of labor, stem the corpora, and take out stop words. The words (in English) include worker, guild, craftsman, journeyman, apprentice, farmer, peasant, serf, mechanic and labour; we translated these words into our other languages (presented in the Online Appendix). We analyze the topics and word frequencies within these labor-snippets, guided by our hypotheses. We calculate temporal and cross-national variations in word frequencies referencing coordination, state, markets and skills. We have widely read fiction from this era and use historically-appropriate words.

To compare theoretically-derived concepts in snippets of text surrounding labor in national corpora, we choose words that represent these concepts and use a supervised learning model to compare word frequencies across countries. A supervised learning model is appropriate because our categories are specified by theory: our object is not to assess how an individual document fits into a corpus, but to assess cross-national and temporal differences among works that are presorted by country, language and time [Hopkins and King Reference Hopkins Daniel and King2010; Laver, Benoit and Garry Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003]. We calculate difference of proportions tests (reported in the Online Appendix) to evaluate significant differences between the liberal and coordinated countries.

We use a dictionary-based approach to obtain measures for our core concepts. We select words for each core category by searching core terms in an online dictionary and thesaurus. For example, for the concept of cooperation embedded in coordinated market economies, we search for words associated with cooperation, agreement, and collective. We reduce the number of words in each category to highly prototypical words by circulating the words among the three authors and asking each to choose the top 20 words. We then translate the words into Danish, Dutch, and Swedish, and ensure that the stemmed versions of these words not have unintended meanings. Although existing psychosocial dictionaries enable measures of norms and values, our categories specific to modes of collective political engagement require a custom-made specification [Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016].

Second, we supplement our quantitative findings with brief case studies of authors’ writing on and action related to industrial relations development in our four countries. The case studies explore how cultural constructions in fiction are associated with national choices about industrial relations. Because diverse varieties of capitalism presuppose different cultural expectations about class relations, we expect to find cross-national variations in words associated with labor that correspond to modern distinctions.

We posit hypotheses that we may test with our quantitative data. First, we predict that the liberal country of Britain will have different cultural tropes than the coordinated countries of Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. Snippets of text containing labor words from the liberal versus coordinated countries should vary in their references to cooperation, skills, government, and markets. Second, if the paths toward coordinated and liberal market economies were influenced, in part, by enduring norms, cross-national variations should extend back to the 18th century, when our data begin. Third, the references to concepts should vary according to the economic ideas that dominate during a specific period of time. Thus, coordinated countries should have fewer references to cooperation during the mid-19th century than they do around 1800 during the Enlightenment or the late 19th century with the search for order.

Finally, we also expect to see differences among the coordinated countries that can be attributed to their different pathways toward coordination and institutional features. The Netherlands has a more “liberal” version of corporatism than Denmark and Sweden [Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1985]; therefore, Dutch literary narratives should express a larger role for markets compared to the Nordic countries. Danish policies enjoyed greater multi-party and cross-class support than Swedish ones, where the Social Democrats drove political innovation; therefore, we should expect to see higher levels of class conflict in Sweden than in Denmark [Anthonsen and Lindvall Reference Anthonsen and Lindvall2009]. Yet despite differences on many economic and social dimensions (which undoubtedly contribute to the diverse paths toward coordination), the coordinated countries converge on norms of cooperation, attention to social investment and importance of the state. The following hypotheses should hold true (in snippets of text surrounding labor words):

1. Coordinated countries should have more words associated with cooperation than liberal countries.

1. a. We expect lower levels of cooperation in the 1820-1870 period when liberalism became a dominant political philosophy.

2. Coordinated countries should have more words associated with skills than liberal countries.

2.a. We expect fewer references to skills in the Netherlands because the economy has fewer blue-collar workers and more commercial services.

3. Coordinated countries should have more references to the state than liberal countries.

3.a. We expect references to government to be particularly high in the Nordic countries.

3.b. We expect references to government to decrease in the coordinated countries in the 1870-1920 period when industrial self-regulation was established.

4. Liberal Britain and the Netherlands should have more references to markets than the Nordic coordinated countries.

Quantitative Findings

The quantitative data show differences between the CME and LME models, within the CME model, and across time periods. We find stark differences between the liberal market economy of Britain and the coordinated market economies. We also find interesting intra-model differences among Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, which all converge on a coordinated industrial relations system by the early 20th century but which take somewhat different paths to arrive at this point. Finally, we note that the liberalizing period of 1820 to 1870 generally had lower levels of cooperation words in the coordinated countries than the periods of land reform (1770-1820) and industrial coordination (1870-1920). (Please see Difference of Proportion results in the Online Appendix.)

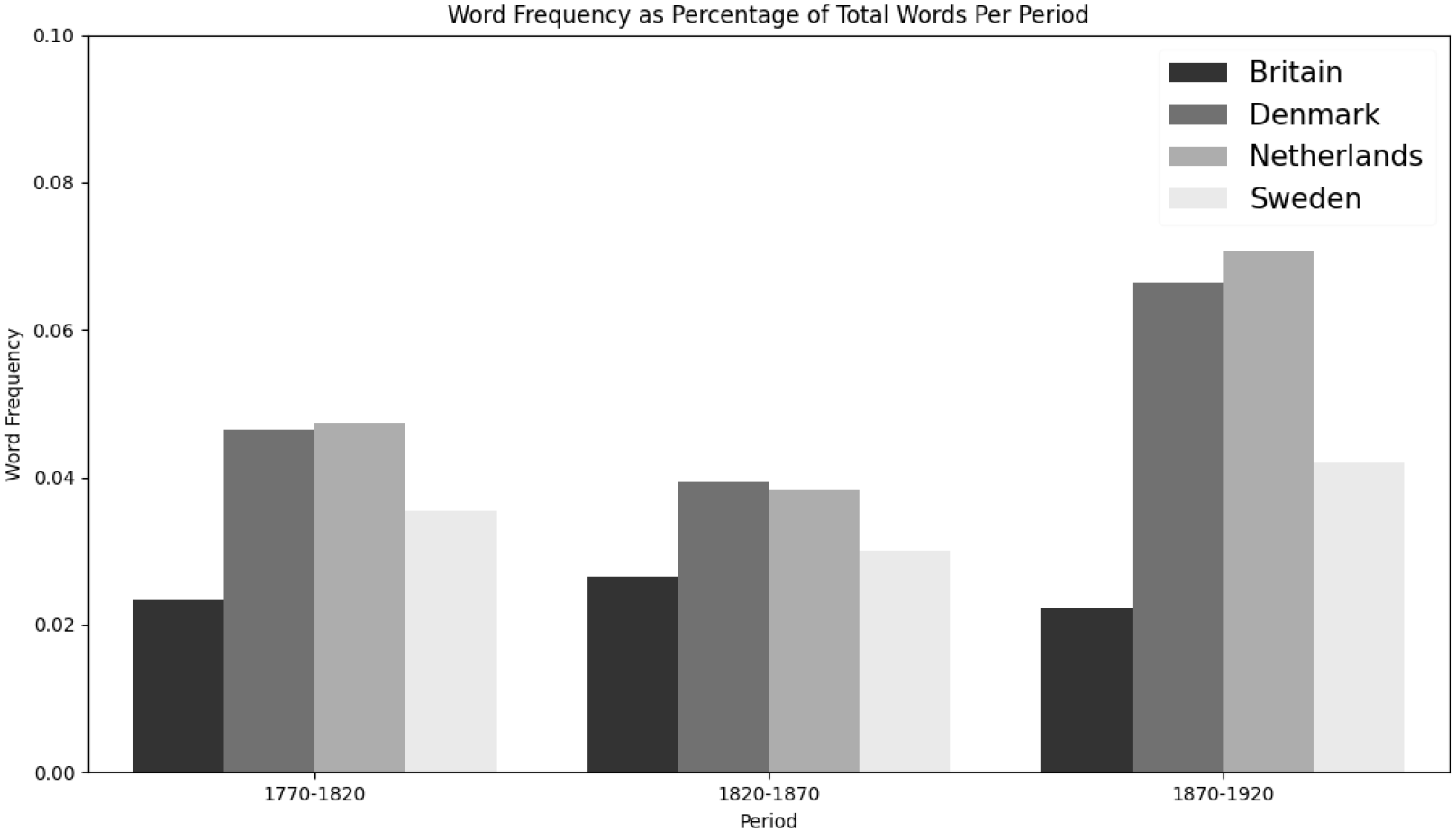

Figure 2 reports frequencies of labor words as a percentage of all words in each national corpus. Some of the coordinated countries have higher levels of labor words compared to liberal Britain; however, labor words are a small proportion of total works in the volumes.

Figure 2 Frequencies Of All Labor Words In Britain, Denmark, Netherlands And Sweden

Source: Labor words (and bases of snippets) include: work worker guild craftsman journeyman apprentice farmer peasant serf mechanic labour

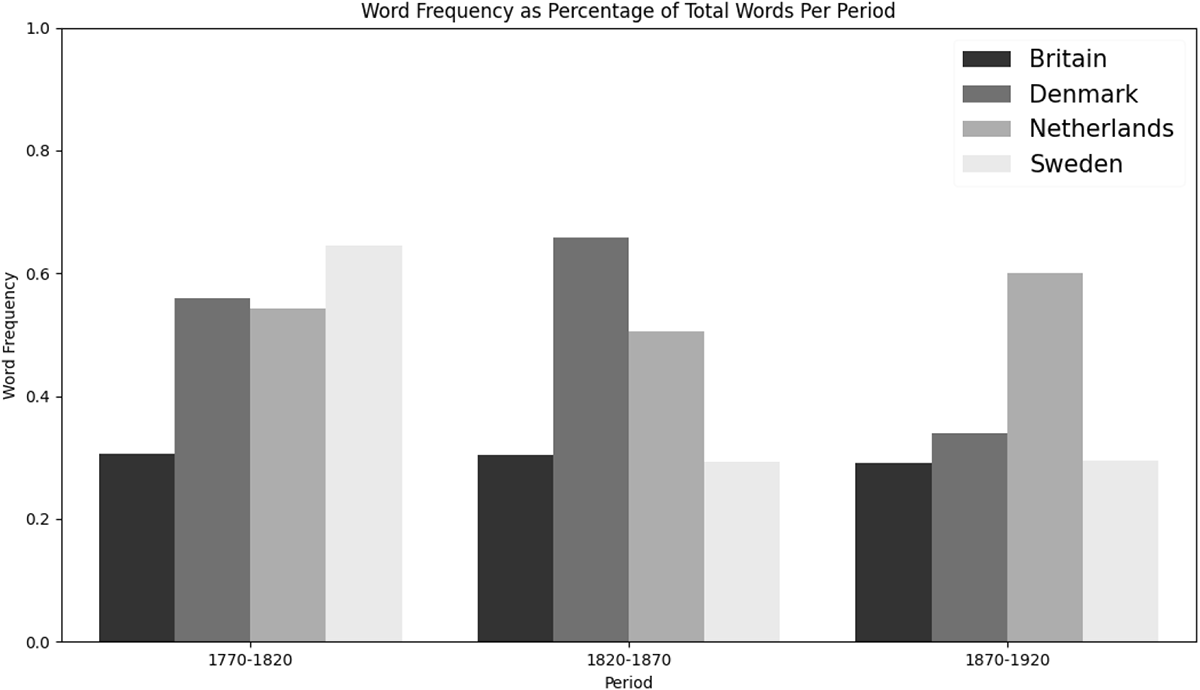

Figure 3 reports the frequencies of cooperation/corporatism words in snippets of text surrounding labor words in Britain, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. The coordinated countries have significantly higher levels of corporatism words than Britain except for Sweden in 1820-1870, a time of increasing tensions between elites and a growing landless rural population as well as widespread popularity of liberal ideas. Cooperation words spike in the coordinated countries during the 1870-1920 period, a time when ideas about labor market coordination became popular and countries were beginning to form early institutions for industrial cooperation. Levels of cooperation remain low in Britain during this period.

Figure 3 Labor Snippets With Coordination Words

Source: Cooperation words include: agreement arbitration bargaining coalition collaboration collective compromise cooperation coordination negotiation pact settlement unanimous unity confederation federation union

Figure 4 presents our findings of the frequency of words referring to skills. Skill words are significantly higher in the Nordic countries than Britain during all periods. The Dutch corpus includes fewer references to skill words than to Denmark and Sweden. Perhaps this is because trade and services requiring a general rather than vocational education.

Figure 4 Labor Snippets With Skills Words

Source: Skills words include: skill ability competency proficiency qualifications

Figure 5 reports on our findings for the frequency of government words. As predicted, the coordinated countries (particularly the Nordic ones) have significantly higher frequencies of words associated with government than liberal Britain. The frequencies of government words decline in late 19th century Denmark, as industrial self-regulation becomes a central aspect of the Danish model; however, the level remains significantly higher than that of Britain. The frequency of government words declines in Sweden and the Netherlands during 1820-1870, a period characterized by liberal ideas in the two countries, and increases again in the late 19th century when liberal ideas are increasingly challenged.

Figure 5 Labor Snippets With Government Words

Source: Government words include: nation government ministry authority law legal illegal judgment judge council commission committee public municipality parish king kingdom crown throne

Figure 6 illustrates word frequencies of market words in snippets of text surrounding labor words. For all periods, references to markets are significantly higher in the Netherlands and Britain, both early commercial economies, than in Sweden and Denmark. The high Dutch scores on this dimension reflect both its more commercialized and urbanized nature, and the polder model’s high levels of both liberalism and coordination [Windmuller, de Galan and Zweeden Reference Windmuller, de Galan and van Zweeden1987].

Figure 6 Labor Snippets With Market Words

Source: Market words include: market sell buy exchange supply demand price cost trade commerce

Overall, the quantitative data confirm our hypotheses about the coordinated countries’ greater emphasis compared to Britain on cooperation, skills and the role of the state. In the following, we provide context for the results by studying the cultural politics of industrial relations system development.

Case Study Findings

The institutional prototypes of modern liberal and coordinated market economies emerged around 1900 in response to globalization and labor market conflict. The coordinated countries of Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands developed peak employers’ associations and labor federations. Over time, the compromise-oriented industrial relations systems of the three countries developed corporatist tripartite decision-making and national-level bargaining. In liberal Britain, agents also sought to organize business and labor interests on the national level, but these attempts ultimately failed. Britain was left with decentralized business representation, fragmented unions, firm-level bargaining, and state-centered policy-making (Table 2).

Ideas about political and economic liberalism had been popular in the mid-19th century. Yet technological innovations allowing for long-distance food transport combined with abundant agricultural crops created a long, worldwide depression beginning around 1873; and labor unrest rose with industrialization and landless agricultural laborers. Countries looked again to coordination to cope with expanded international competition, new forms of production and growing labor power [Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1986].

Denmark

Generations of Danish authors valued workers and peasants, cooperation, skills and the state in matters of labor relations. Authors across the political continuum had been cheerleaders for the working class since at least the 18th century, and they viewed farmers and workers as valued contributors to the strength of the nation and to its economic and political ambitions. Ludvig Holberg’s Niels Klim’s Journey Underground [Reference Holberg1741] advocated for a free and educated peasantry. Niels Klim travels to a subterranean world where classes do not exist, respect is conferred on those “noted for virtue and industry,” profession is accorded by talents, and each should “impartially judge of his own merits and faults” [Holberg (Reference Holberg1741) 1845]. Laws once favored some classes to the exclusion of others, but this favoritism resulted in “frequent disturbances” and citizens resolved to end such distinctions “as conducive to the general interest” [446 to 457 out of 1846]. Adam Oehlenschläger [(1807) 2010] created an evil character in Hakon Jarl, who tried to rule with slaves [105]. When Hakon seized the throne, he was thwarted by a peasant uprising [113], after which peasants met at the Thing to choose another king [170]. Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig, poet, priest and scholar of Nordic mythology, envisioned peasants and workers—“workmen of the sun”—as an essential part of Danish organic society, a body unified by spiritual unity and a common language [Grundtvig Reference Grundtvig and Bugge1968]. Some equality was necessary to the unity of the people, as expressed in the stanza, “We Danes though can point to everyday’s bread In even the lowliest dwelling—Can boast that in riches our progress is such That few have too little, still fewer too much” [Lindhardt Reference Lindhardt Poul1951: 27].

Realist authors of The Modern Breakthrough movement became alarmed at the increasing industrial risks harming workers and peasants and expressed sympathy with unions, farmers’ organizations and other cooperative institutions. Yet authors held positive views of industrial development itself as a vital collective project, and sought mass education to meet collective goals of building society and national economic prosperity. In Thomasine Gyllembourg’s Montanus the Younger [1837, Reference Gyllembourg2019], Conrad has great ideas about technological innovation, and envisions how expanded production will increase employment [loc 696]. Conrad disrupts social harmony and insults a local bureaucrat, who nevertheless offers Conrad a state subsidy for the factory because “I honor my land’s well-being, and such a factory I hope will become a great gift for the land” [loc 2028]. The book describes Conrad’s personal growth and offers a blueprint for how society could integrate new technology, preserve social harmony, avoid harm to redundant workers and espouse a national project for economic growth. Nobel Prize winner Henrik Pontoppidan’s Lucky Per [Reference Pontoppidan and Lebowitz1898-1904, 2019; celebrated industrialization as a way of improving Denmark’s economic fortunes [333-334], but decried the collateral damage imposed by industrialization on workers. Protagonist Per admired workers and their collective spirit: “It struck him what a fresh and active sympathy the workmen manifested from the beginning, although most came out of Copenhagen’s lower classes […] They did not quarrel with anyone and were held together by mutual respect” [480]. Per’s fiancée admired the labor movements’ “close ties with modern technical development” and felt “alliance with the sooty, subjugated army of workers craving light, air, and humane treatment” [209, 199-200].

Cooperation was also a leitmotif running through literature across the ages. Holger Drachmann’s There once was [1884], the most performed play in Danish history, ends with a song, “We love our land,” that is still sung every year on the summer solstice to reinforce community and collective identity. The third stanza emphasizes Denmark’s love of peace: “Each town has its witch and each parish its troll, We keep them from life with joy that we hold, We will have peace here in this land, Saint Hans, Saint Hans, Peace can we win if hearts never be cold” [Drachmann Reference Drachmann1902: 121]. Socialist writer Martin Andersen Nexø in Pelle the Conqueror [1906-1910] also advocates for cooperation between strongly organized workers and employers to lift Denmark out of rural poverty. Pelle is transformed by education but remains loyal to the working class; despite temptations to violence, he strives for a peaceful transition to a better world.

Writers also valued workers’ skills and lobbied intensively for mass education. Grundtvig’s ideas for practical mass education inspired disciple Christian Kold to start the folk high school movement within rural peasant communities, and authors such as Bernhard Severin Ingemann and Steen Steensen Blicher supported this effort. Ingemann wrote to Grundtvig that without education, “Denmark’s sons” could “drown in the contemporary political and economic maelstrom” [Aakjær Reference Aakjær1904]. In Ingemann’s King Erik and the Outlaws, a character reflects on the futility of education dominated by “theological subtleties” and scholars who “still chew the cud of mysticism,” arguing instead that “an intimate knowledge of the essence of things is of the highest importance” [Ingemann, loc 20435-9]. Johan Ludvig Heiberg’s vaudeville, April Fools [Reference Heiberg1826], ridiculed an education that failed to provide real skills to students and celebrated experiential learning: “Try as we may in our little school, The school of life dares much more. Teachers can give us some learning tools, Yet the promise of school falls short. Life is short but art will last. Life itself is a school class” [Heiberg Reference Heiberg1826, loc 627]. In H.C. Andersen’s Only a Fiddler [(Reference Andersen1837) 1908], Christian’s kind landlady read books from the local library to follow “the advance of literature as well as she could in a provincial town” and wondered “why should not poverty enjoy the advantage?” [Andersen 1908/Reference Andersen1837, 117-118].

Finally, authors offered a positive view of government that was grounded in the will of the people. In Ingemann’s The Childhood of King Erik Menved, a character noted that in state authority “The mere external domination, which has not its roots in the deepest heart of the people […] is worthless and despicable” [Ingemann (1828) Reference Ingemann and Haggard2014, 8264]. Blicher’s The Pastor of Vejlbye [1996, Reference Blicher Steen1829] described a judge’s anguish on condemning an innocent pastor who had been set up for a crime, after the villain demanded a hearing because “we have law and justice in this country” [10]. While a miscarriage of justice occurred, officials acted honestly, albeit tragically, and the case prompted improvements to the criminal justice system. In Gyllembourg’s Montanus the Younger [1837, Reference Gyllembourg2019], Conrad received financial support and encouragement from the government for his visionary industrial project [365].

A network of modernist (or free-thinking) Danish authors participated in late 19th century political struggles relevant to cooperative labor relations. Authors of the Modern Breakthrough (or free thinkers), led by Georg Brandes, viewed industrialization as an opportunity to move beyond rural poverty and regarded favorably institutions for industrial coordination (such as unions) [Skilton Reference Skilton, Hertel and Kristensen1980: 37-43]. For Brandes, economic emancipation was more vital than political suffrage and parliamentary democracy [Brandes, Levned, III, 124]. Victor Pingel interpreted Darwin as providing evidence for social cooperation and balance between the individual and society [Sevaldsen Reference Sevaldsen1974: 233]. Modernists were alarmed by the growing labor market conflict, which peaked in the 1885 iron industry lock-out, and rejected Prime Minister Estrup’s dictatorial rule. Drachmann wrote to Georg Brandes that he was worried that the Estrup government would take dreadful measures such as jailing activists [Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2020: 74-75].

Georg and Edvard Brandes formed a faction of the Liberal Party (Venstre) called the Literary (or Intellectual or European) Venstre (including authors, students and other intellectuals); the faction sought alliance with the peasant wing of Venstre, led by Christian Berg. Berg persuaded Edvard Brandes to run for Parliament, and the Literary Venstre helped the peasant wing to forge a new ideological platform that was crucial to the battle for constitutional reform. Berg noted that, in the past, the Conservative Party (including old National Liberals) had won the war of words and it “was a hopeless case to make people understand that the true opinion was on our side.” But with the inclusion of the intellectual wing, Venstre now “had our poets, our professors, our jurists, journalists, students like the others […] Like manna from heaven, the Literary Venstre came down into this desert” [Hvidt Reference Hvidt2017: 127-128.]

Literary Venstre also issued their message of cooperation and education to groups in society. Modernist writers worked with the evangelical Grundvigian folk high schools (with Henrik Pontoppidan’s brother, Morten, a key liaison) [Skovmand Reference Skovmand1944: 422-428]. Julius Schiøtt, a Student Association leader who became secretary of Industriforeningen (the precursor to Danish Industry), invited intellectuals to address contributions of education to economic competitiveness, and the Federation of Danish Industry’s Arbejdsgiveren published an article on the topic [Nørr Reference Nørr1979: 204-205]. The Student Society (led by Victor Pingel) sponsored free, evening classes for workers, serving between 1,500 and 2,000 workers in Copenhagen each year [Skovgaard-Petersen Reference Skovgaard1976: 51-52]. Leading authors such as Georg Brandes, Karl Gjellerup and Sophus Schandorph offered lectures to the workers [Sevaldsen Reference Sevaldsen1974: 244.]

The message of social harmony resonated with Niels Andersen (Right Party politician and founder of the Federation of Danish Industries (Dansk Arbejdsgiverforeningen or DA), who remarked that “it is almost more important to have a good employers’ association than a good government” [Agerholm and Vigen Reference Agerholm and Vigen1921: 211-212]. DA encouraged labor unions to create a parallel encompassing peak association, and embraced an early vision of tripartism, in which organized business, labor and the state would work together to manage industrial relations (Andersen to Foreningen af Fabrikanter i Jernindustrien i Kjøbenhavn. DA—Korrespondance, General udgående 1896 6 30 til 1899 9 21). The employers’ federation responded to a minor strike in Jutland with a lockout extending across the economy, but quickly ended the conflict by setting up a process for industrial coordination [Due et al. Reference Due, Madsen, Jensen and Petersen1994: 80-81]. An observer noted, “Had the employers really been convinced of winning, it seems odd for them to have abstained from dictating humiliating terms […] The main outcome of the conflict of 1899 was, in reality, that both parties became equally strong” [Arbejdsforhold indenfor dansk industri og håndværk 1857-1899: 525-526, trans. by CJ Martin; Martin and Swank Reference Martin Cathie and Swank2012].

Britain

British authors dating back to the 18th century depicted workers, cooperation, skills and government very differently from their Danish counterparts. With some exceptions (William Godwin and Thomas Holcroft), 18th century authors largely ignored the lower classes. Stories of poverty usually entailed the failing fortunes of the middle classes, and even writers concerned with political rights did not much question the class system (Brown). Jane Austin’s eponymous Emma made a fatal error by raising undue expectations of marital bliss in her low-born friend. Thomas Malthus’s 1797 An Essay on the Principle of Population [1797-1809] provided a logic that blamed members of the working class for their own malaise: population would rise unheeded with expansion of the means of subsistence, unless population growth was limited by checks of moral restraint, vice, and misery [Malthus Reference Malthus1809: 27-28]. Even while reforming bureaucrats such as James Kay (Shuttleworth) sought to end poverty, they accepted working class distress as a social disorder resulting from the disorganized culture and the lack of education among the poor. Critics denounced Malthusian pessimism, yet the right and left converged on concerns about overpopulation and excessive reproduction among the lower classes [Steinlight Reference Steinlight2018]. Even Victorian social reform novelists, who were famously sympathetic to the tribulations of the working class, worried about working class culture. Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley [1849/Reference Brontë1907] had sympathy for the poor but would battle their rampage. The novel’s starving, unemployed Luddites were not portrayed as foot soldiers in an agricultural revolution who contributed to the economic good of the country, as might have occurred in Denmark. In The Netherworld, George Gissing stressed the cruelty of the urban poor: “Clem’s brutality [and] […] lust of hers for sanguinary domination was the natural enough issue of the brutalizing serfdom of her predecessors in the family line” [Loc 95]. HG Wells in 1934 feared cultural degradation associated with mass culture and described the “extravagant swarm of new births” as the “essential disaster of the nineteenth century” [Carey Reference Carey1992, 1].

Authors celebrated conflict and offered little praise for cooperation in their works. Young protagonists, such as David Copperfield, struggle against all odds to triumph over personal hardships. Even reforming authors held a negative view of unions, as is exemplified in Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South. A poor worker, John Boucher, remarked regarding organized labor that “Yo’ may be kind hearts, each separate; but once banded together, yo’ve no more pity for a man than a wild hunger-maddened wolf” [180]. Upon Boucher’s death, the novel’s heroine lamented, “Don’t you see how you’ve made Boucher what he is, by driving him into the Union against his will” [336]. British novelists doubted workers would ever support technological innovation. In Brontë’s Shirley, the Luddite “sufferers hated the machines which they believed took their bread from them; they hated the buildings which contained those machines; they hated the manufacturers who owned those buildings” [Brontë 1849/Reference Brontë1907, 26-27].

For British authors, education and skill-building were largely an individualistic affair to further self-development rather than an investment in a strong society. Coleridge warned that “a man … unblest with a liberal education, should act without attention to the habits, and feelings, of his fellow citizens”; education would “stimulate the heart to love” [Coleridge, Reference Coleridge1796, #IV]. John Stuart Mill [Reference Mill1829] posited education as the mechanism for the cognitive and moral development of the (primarily upper and middle class] individual. Matthew Arnold explained, “The best man is he who most tries to perfect himself, and the happiest man is he who most feels that he is perfecting himself” [Arnold, 1867-Reference Arnold1868: 46]. Authors generally favored humanistic studies over skills development for the working class; for example, Kipling wrote stirring testimonials about the importance of literature for workers and soldiers, a message that resonated with his cousin’s husband, John Mackail, who drafted the 1904 secondary education regulations emphasizing humanistic studies over technical training [Martin Reference Martin2018].

Finally, British authors doubted government’s capacity to ameliorate social ills. In Caleb Williams, William Godwin suggested that, regarding laws intended to safeguard the interests of the poor, “Wealth and despotism easily know how to engage those laws as the coadjutors of their oppression” [75]. Dickens ridiculed self-interest in the legal system as when David Copperfield’s Mr. Spenlow remarks, “the best sort of professional business […] [was] a good case of a disputed will […] [with] very pretty pickings” [366], and in Bleak House the lawsuit Jarndyce v Jarndyce consumes a disputed estate.

Even authors on the left did little to cultivate a spirit of industrial cooperation and cross-class consensus. Fabian Socialists such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and HG Wells certainly sought a better world for workers, but envisioned a solution in which civil servants would rule over both politicians and the ignorant lower classes. The Fabian Society distinguished itself from the Social Democratic Federation and Socialist League in its aim to represent progressive voices within the middle class rather than the working class [Garver Reference Garver2011: 92-93]. Bernard Shaw praised the Fabian Society for its exclusive and non-doctrinaire demeanor, in sharp contrast to the large workingmen’s organizations. Shaw once refused to address a group of unemployed by explaining, “No, as long as I have a watch in my pocket which I do not intend to pawn, I will not pretend sympathy with men who are actually hungry” [Clarke Reference Clarke1978: 32-35]. The Fabians also did not get involved with the Labour Party, as they tried instead to infiltrate the Liberal and Conservative Parties [Hannah Reference Hannah2018: 6]. Writer and designer William Morris joined workers in the Democratic Socialist Federation and later the Socialist League; yet in Morris’s utopian novel, News from Nowhere, all institutions (unions, states, schools and markets) disappeared [Morris Reference Morris1890]. Nor were authors involved in employers’ efforts to organize themselves collectively.

Sweden

Swedish writers were generally skeptical of unfettered capitalism and, increasingly, the traditional social order, but they also criticized disruptive labor mobilization. This seeming dichotomy mirrored the path to labor-market coordination in Sweden, which was rife with conflict [Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson2019; Dahlqvist Reference Dahlqvist2020]. Authors praised workers’ contributions to society and advocated for labor-market compromise, class solidarity, mass education, and government intervention. Peasants became an important cultural symbol in the construction of modern Sweden at the dawn of the 19th century [Stråth Reference Stråth2004: 7-9; 2017: 48-50], and writers praised the peasantry as the backbone of society. Count Johan Gabriel Oxenstierna provided an idyllic image where the farmers’ labor “for beauty or benefit betters the land” [The Harvest, Reference Oxenstierna1796]. Thomas Thorild wrote that “The farmer is everyone’s father still/Still in this day” [Gothic Men’s Songs Reference Thorild and Engdahl2000/1806, translated by Nolin Reference Nolin and Warme1996]. Erik Gustaf Geijer praised the social and political autonomy of the farmer, which he described as an individual self-sustaining landowner [The Yeoman Farmer, Reference Geijer and Landquist1924/1811]. Carl Jonas Love Almqvist praised the virtues of the laboring poor, arguing that “To be poor, this means to be dependent on one’s own resources” [Reference Almqvist and Roberg1996/1838, quoted in Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 210].

Social, economic, and political transformations led authors to address new social problems and agendas in the late 19th century. The realist literature of the 1880s criticized conservative social and political institutions, and highlighted the hardship of workers and the poor [1961: 244-253], but this trend was followed in the 1890s by heightened labor-market conflict and by a conservative literary reaction focusing on imagination, beauty, escapism, individualism, and defense of tradition [Brantly Reference Brantly and Warme1996; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 253, 292-293]. Despite these differences, writers throughout the period represented labor as an essential resource for the nation. In Selma Lagerlöf’s Gösta Berling’s Saga [Reference Lagerlöf1933/1891], a group of men, including the defrocked priest Gösta Berling, make a deal with the devil to gain control over a large estate. In return, the men promise not to do anything productive with the estate and its foundries. The men lead a life of luxury, but their negligence results in the deterioration of the estate, the surrounding countryside and its people. Gösta Berling realizes that his salvation lies in a life of work and in caring for others, not in frivolous entertainment and self-indulgence [Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 310].

Themes of solidarity, cooperation, and compromise were central to many Swedish writers. Early 20th century authors reinvented the realist tradition and grappled with social change, industrialism, and the situation of the working classes; they thereby provide new cultural imaginaries to underpin the emerging “Swedish model.” Working class authors wrote from an insider perspective [Brantly Reference Brantly and Warme1996, 302-305; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961, 348-349; Nilsson Reference Nilsson, Lennon and Nilsson2017], and this literature emphasized the shared experiences of workers and the need for solidarity. Martin Koch’s novel Workers: A Story of Hatred [Reference Koch1912] tells the story of an employers’ association conspiring against workers. The workers recognize that by rising in unison they can improve their collective well-being and status in society. As working class literature became increasingly popular in the early 1900s [Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 345-350; Nilsson Reference Nilsson, Lennon and Nilsson2017], it legitimized workers’ claims to equality, political influence, and social change.

Middle class realist authors of the same period instead promoted opportunities for compromise and coordination between industry and workers. While they provided optimistic visions of Sweden’s future development, they were critical of both unfettered capitalism and organized labor mobilization [Brantly Reference Brantly and Warme1996: 298-302; Forsgren Reference Forsgren2016; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961 352, 369-370]. Ludvig Nordström emphasized both the importance of industrialization for the development of Sweden and of the productive role of workers in industrial development; he sought a relationship between labor and capital characterized by cooperation and compromise [Forsgren Reference Forsgren, Bergenmar, Jansson, Gondouin and Malm2009: 191; Forsgren Reference Forsgren2016: 6-8; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 373-375]. Elin Wägner also promoted cooperation and compromise in her writing, with a focus on both class and gender [Forsgren Reference Forsgren2016: 8-9; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 376-379]. Sigfrid Siwertz, in novels such as An Idler [Reference Siwertz1914] and Selambs [Reference Siwertz1920], criticized unfettered capitalism and its tendency to revert civilization to a Darwinian survival of the fittest. In Selambs, Siwertz tells the story of the Selambs family whose greed corrupts the family and its business. Despite his critique of capitalism, however, Siwertz ends the novel by emphasizing the threat of “mass egoism” (i.e., socialism) [Brantly Reference Brantly and Warme1996: 300-301; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 371-372; Mattsson Reference Mattsson, Forssberg and Mattsson2017].

Skills and education were also crucial both for national prosperity and for individuals’ economic opportunities. Sweden had a long tradition of promoting mass education, but the Education Reform of 1842 created greater access to non-religious, formal schooling [Andersson and Berger Reference Andersson and Berger2019; Sandberg Reference Sandberg Lars1979]. In the 1830s, authors such as Geijer and Almqvist advocated a new educational philosophy for individual freedom and responsibility as well as social equality [Ullman Reference Ullman2014]. In the 1880s, authors such as Gustaf af Geijerstam in Erik Grane [Reference Geijerstam1885] and August Strindberg in The Red Room [Reference Strindberg and Smedmark1879] turned their criticism toward the universities, which they considered overly rigid, conservative, and useless in a new and rapidly changing society [Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1961: 249-250]. Authors sought equal access to education and schooling focused on the needs of the new industrial society.

Swedish authors were also highly concerned with the proper role and nature of government. Swedish government had for centuries been based on extensive national representation and a large degree of local self-government for land-owning peasants [Aronsson Reference Aronsson1992]. Some authors, such as Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom, criticized liberal republicanism and materialism. In The Isle of Bliss [Reference Atterbom1875/1827], Atterbom tells the story of King Astolf who travels to the Isle of Bliss where he marries Felicia. When he returns to his old kingdom after 300 years, he is horrified to discover that materialism, populism, and the end of monarchical rule have taken hold [Hermansson Reference Hermansson2015]. Other writers, such as Anna Maria Lenngren and Almqvist, drew attention to problems relating to poverty, the ingrained class system, and the anti-democratic tendencies of the aristocracy. While authors differed in their views on democratic principles, they jointly held that government must be strong, and rulers could not neglect their duties toward the people. Geijer praised the autonomy of the freeholding peasant, tied the history of the Swedish people to the history of its kings, and praised the rule of law [Torstendahl Reference Torstendahl1993: 252-256].

The Netherlands

Dutch authors dating back to the 18th century also displayed great concern with the plight of the working class, including peasants, and the virtues of social harmony and class cooperation were persistent literary themes. Farmers and workers were central characters in novels and poems during the early 19th century, appearing as strong characters with much agency [Hanou Reference Hanou2002: 174-176]. The typical farmer in this literature was crafty and stood his ground, including in his dealings with representatives of authority [van den Berg and Couttenier Reference Berg Willem and Couttenier2009: 579]. The most widely read literature genre well into the 19th century, known as “preacher-poetry”, displayed a strong preoccupation with matters such as class, poverty, and egalitarian justice. Peasants, workers, or lower middle class citizens (“kleine luyden”) were praised as constituting the backbone of Dutch society [Ibid.: 34-35]. A typical theme was that “honest modesty” was to be preferred over “wasteful wealth,” and influential preacher poets such as Cornelis Koetsveld displayed great concern with the plight of the poor, emphasizing their right to assistance [Visscher Reference Visscher2005].

By mid-century, as realistic novels became more popular and the gradual process of industrial development had created a new urban proletariat, authors began to highlight the hardships of the working class and actively addressed social problems. Authors such as Everhardus Potgieter emphasized the need for the middle class to display concern with the fortunes of the working class [Smit Reference Smit1983]. In his influential novel Factory Children [Reference Cremer1863], the author and painter Jacob Jan Cremer not only loudly decried the harsh conditions experienced by the working class in this period; in the final pages of his work, which are written as a pamphlet, he directly addresses the King and parliament with a request for government regulation to deal with the social mishaps described in the novel. His novel Hanna de Freule [Reference Cremer1873: 23] advocates the right to engage in collective action when workers in the novel successfully “put their heads together” and successfully determine “not to move a hand”, until their situation is improved. As was the case in preacher poems, the major characters in these realistic novels were often “kleine luyden” rather than the upper middle class and elites, and novels emphasized the importance of connections between societal groups [van den Berg Reference Berg1999: 120-121].

Dutch authors also consistently emphasized the importance of social harmony and compromise in their writings. These themes were often explicitly linked to the tradition of participatory democracy and consensual policy-making in the country. Popular literary journals, such as the Philosooph, Rhapsodist, and Borger, emphasized the importance of civil participation and lauded the “cultural of compromise” that they attributed to the many forms of participatory democracy that existed at the lower level [Kloek and Mijnhardt Reference Kloek and Mijnhardt2001: 240]. Popular writers such as the preacher-poet Cornelis Ris and the classicist Jan Willem van Sonsbeek also emphasized the need to distribute political power and ensure that all citizens were able to participate fully in civil society [Ibid.; Mathijsen Reference Mathijsen2004].

In response to social and economic transformations, authors increasingly display sympathy for the worker movement and concern for societal harmony and the culture of compromise. The preacher poet Cornelis Koetsveld [1849] complains in his novel The Beautiful Unknown that society “has been torn apart” and criticizes the “harshness of the new societal order.” Publications in new literary magazines such as The New Guide also emphasized the need to build a more “just society” that connected with new values such as “collectivism” [Anbeek Reference Anbeek1999]. Contributors such as Nicolaas Pierson and Hendrick Quack supported the right to engage in collective action but explicitly rejected the notion of class struggle, arguing for an “organic society” that was based on the spirit of cooperation and compromise [Winkels Reference Winkels1985: 174-176].

By the turn of the century, a new generation of modernist authors came to participate actively in political debates on national renewal, economic emancipation, and labor union organization. The growing segregation of Dutch society in different “pillars” reinforced authors’ engagement as it fostered links between authors, artists and political parties with the same worldview. Authors of the important literary movement, Poets of the Eighties (“de tachtigers”), forcefully argued against reactionary thinking and in favor of a more just society; prominent members such as Frank van der Goes and Pieter Lodewijk Tak were actively involved in the social democratic party. The key journal of this movement, The New Guide, was nicknamed “journal of the literary and scientific proletariat” and frequently published articles on the need to organize the proletariat, invest in education, and find collective solutions for the development of “a new industrial nation” [Winkels Reference Winkels1985].

Crucially, the activities of the Poets of the Eighties were mirrored by Confessional writers, who also frequently addressed social issues. Indeed, compared to their liberal and socialist counterparts, confessional writers displayed even stronger concerns with fostering social harmony in economic and political affairs. This was certainly the case with the previously mentioned preacher-poets, whose work continued to enjoy much popularity up to the end of the century [van den Berg and Couttenier Reference Berg Willem and Couttenier2009: 505-506], but even more conservative confessional writers shared the enthusiasm for social harmony. Thus by mid-century, conservative publicist Groen van Prinsterer already lamented the free reign of competition in labor markets as problematic, because it created a world “in which social ties have been ruptured [and] society is divided into two hostile armies.” His ideas would greatly influence later generations of writers and politicians, such as the publisher and founder of the Anti-Revolutionary Party, Abraham Kuyper, who later became prime minister [Prak Reference Prak, van Gerwen, Wals, Seegers and van Tielhof2014].

Conclusion

Cultural depictions of labor in the 18th and 19th centuries anticipated policy choices for labor relations made by coordinated and liberal countries. Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands—countries with radically different economies—developed similar patterns of industrial coordination and cooperation. These coordinated countries shared similar depictions of labor in their national literature, and these depictions differed dramatically from those found in pluralist Britain. The patterns separating the coordinated countries from the liberal one began long before modern systems of industrial relations emerged at the end of the 19th century. We do not claim that cultural depictions “caused” the cross-national variation in industrial relations systems, yet our findings suggest that authors’ depictions helped set the context of other political actors’ expressions of preference for cooperation and conflict.

Our findings have important ramifications for the study of industrial relations systems development. Students of political economy debate the relative importance of industrialization, power resources, and preindustrial systems for cooperation in the evolution of modern industrial relations systems. We believe that power struggles definitely contributed to the evolution of industrial coordination, as workers sought rights from employers; however, cultural actors and artifacts contributed to the constitution of class relations. Class conflict was not absent in Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands; yet, labor was perceived as a societal resource in the coordinated countries in a manner that was lacking in Britain. Thus cultural work sheds light on the moral economies underlying diverse varieties of capitalism.

Our observations on the role of cultural artifacts are designed to complement rather than to replace existing theories of industrial system development, as we believe that cultural depictions interact with economic and political explanatory variables. For example, there is undoubtedly a reciprocal relationship between the evolution of cultural touchstones and labor market institutions. Historical traditions of cooperation dating back to the early modern period anticipated modern industrial relations. These institutions also helped to shape the culturally-specific themes in literary works. Thus, we suspect that preindustrial labor institutions such as guilds and the manorial system both influenced and were influenced by cultural depictions in the early second millennium.