1. Introduction

A growing body of literature deals with the changing profile of social democratic parties as they aim to attract new voters. One important argument in the literature is that parties have changed their profiles; for example, they have reached out to voters beyond the working class (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014; Gingrich and Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Schumacher, Reference Schumacher2015). This literature suggests that these political parties started addressing members of the middle class and individuals affected by new social risks, who prefer policies aimed at actively putting individuals back into jobs over transfer payments to the needy (Gingrich and Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). However, this policy shift alienated their traditional working-class constituency, which benefited the most from strict employment legislation and high benefits (e.g. Schwander and Manow, Reference Schwander and Manow2016). This estrangement is unsurprising because policies that invest in increasing the employability of jobseekers differ fundamentally from measures that protect those who already have a job. Whereas traditional policies aim to de-commodify workers by granting them a livelihood without reliance on the market in case of need (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), activation policies aim to recommodify workers by increasing their labour market participation, either by means of skill development or sanctions (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013). Furthermore, research shows that social democratic parties’ strategies are context-dependent. In dualising countries such as Germany, France, and Italy, social democratic parties still have incentives to cater to traditional constituencies because of the strong labour market dualisation, i.e. the division of the labour market into a primary labour market with stable and well-paid jobs with adequate social benefits and a secondary labour market with precarious and underpaid jobs with very limited social benefits. This labour market segmentation results in diverging preferences: namely, for traditional transfer payments and job security for individuals who work in the primary labour market on the one hand and social investment and activation policies for workers facing new social risks and/or working in the secondary labour market on the other hand (Rueda, Reference Rueda2007; Emmenegger, Reference Emmenegger2009; Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Haeusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012; Fossati, Reference Fossati2018).

In this paper, we analyse how social democratic parties benefit electorally from traditional policy measures to fight unemployment in the context of an economic crisis. In fact, if traditional labour market policy is as important in dualising countries as argued by researchers, this should be a particularly promising background for electoral gains for social democratic parties (Rueda, Reference Rueda2007). Thus, we analyse whether traditional policies that aim to protect workers still produce electoral gains for social democratic parties, focusing on the effect of short-time work policy (STW) on incumbents.

We focus on the German elections that took place in late September 2009. In the 18 months prior to this election, one of the worst economic crises of the post-World War II period hit Germany: the GDP declined sharply, and unemployment increased steeply in some regions of the country. The national coalition government, the grand coalition of the social democratic (SPD) and conservative (CDU/CSU) parties, responded with various macroeconomic policies, including an extensive expansion of STW programmes to avoid a further increase in unemployment (Sacchi et al., Reference Sacchi, Pancaldi and Arisi2011). The regional variance in both unemployment and STW rates across Germany and its 299 constituencies was substantial. We exploit this regional variance in an original dataset to analyse the extent to which a) the economic shock and b) the labour market policy response impacted electoral behaviour. The presence of a coalition government makes this case a difficult test to assess the electoral gains of political parties because the responsibility of parties is blurred for voters (Powell and Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Giuliani and Massari, Reference Giuliani and Massari2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Stegmaier and Debus2017).

Our results indicate that – against the backdrop of a grand coalition – social democratic parties still benefit from specific transfer-oriented labour market policies, such as STW, and they benefit more than conservative parties. Nevertheless, electoral credits for such labour market policies did not suffice to win the election. Overall, our paper contributes to understanding the dilemma of social democratic parties. On the one hand, according to our findings, these parties seem to be rewarded for specific protective labour market policies. On the other hand, we know they receive credits for broader programmes of investment-oriented social policies (e.g. Abou-Chadi and Wagner, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019). The challenge for social democratic parties seems to be finding the right mix of both dimensions.

2. Short-time work policy during the economic crisis

During the financial and economic crisis of 2007-2009, policymakers undertook actions to counteract its negative impacts on national economies in many countries. For instance, governments passed measures to save banks and other financial institutions from collapsing and implemented stimulus policies to restart the economy (Braun and Trein, Reference Braun and Trein2014; Trein and Braun, Reference Trein and Braun2016). In Germany, the federal government responded to the financial and economic crisis with two stimulus programmes. The government decided on the first package of measures (Konjunkturpaket I) in November 2008, which contained investments in infrastructure, social and labour market policies, tax relief measures, and affordable credits for small and medium enterprises amounting to a value of approximately 32 billion Euro (Illing, Reference Illing2013, 57). In addition to the mentioned financial measures, the Konjunkturpaket I entailed action to avoid the loss of employment, above all STW (Illing, Reference Illing2013, 58). In January 2009, the federal government passed a second set of measures (Konjunkturpaket II) to stimulate the economy, which were worth approximately 50 billion Euro. This package entailed a new round of investments in infrastructure, support for research in innovative technologies and a 2500 Euro benefit for individuals who bought a new car and scrapped their old vehicle (Illing, Reference Illing2013, 59). A minimum wage was not part of this package.

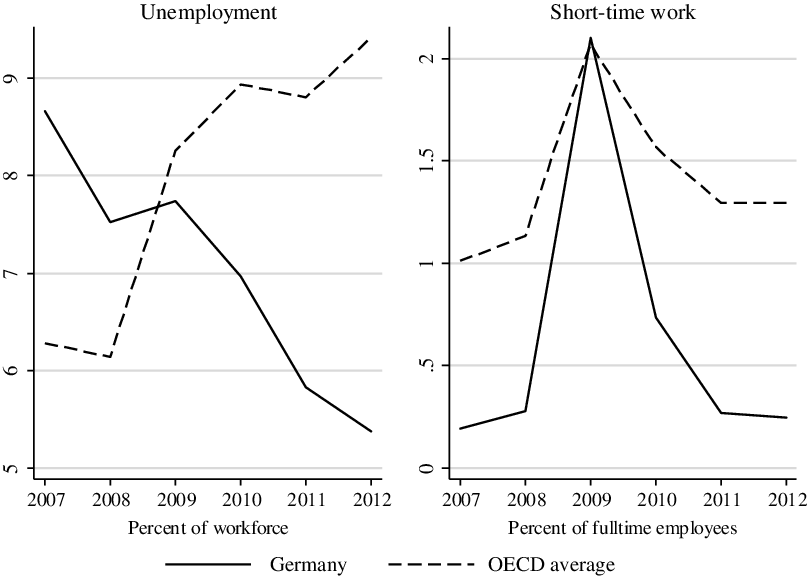

Governments in Germany and other Bismarckian-type welfare states, such as Austria and Italy, thus introduced employment promotion programmes to prevent the economic downturn from turning into rising unemployment rates. One particularly effective measure that is typical for these countries is STW, which consists of payments to companies that allow them to compensate workers for reduced working hours instead of laying them off (Sacchi et al., Reference Sacchi, Pancaldi and Arisi2011). Consequently, especially in Germany, unemployment rates remained rather stable throughout the demand crisis (2007-2009), whereas STW increased considerably and reached the OECD-27 average in 2009, which was a year when most European countries had to address a recession (Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Short-time work and unemployment changes, Germany and OECD average.

In Germany, STWFootnote 2 is an income replacement scheme paid for by national unemployment insurance to compensate for working-time reduction. It was the most important labour market intervention in Konjunkturpaket I, which allowed companies to obtain wage subsidies for their employees if they reduced working hours instead of laying them off (Illing, Reference Illing2013, 58). These decisions were made by the Ministry of Employment under the leadership of the SPDFootnote 3 to prevent increasing unemployment rates.Footnote 4 This policy intervention generated a high level of attention in the news mediaFootnote 5 as well among experts.Footnote 6 Therefore, it is plausible that both governing parties and the SPD in particular profited electorally from the STW intervention.

STW take-up varies regionally (Figure 2). Therefore, this policy context is an interesting case that allows us to assess whether the local variation of these policies influence the aggregate effects of political parties’ electoral fortune given that elections to the German national parliament occurred in September 2009, only nine months after STW rates began to increase sharply (Sacchi et al., Reference Sacchi, Pancaldi and Arisi2011, 31).

Figure 2. Short-time work and unemployment changes in Germany.

Legend: Darker shades indicate higher increases in unemployment levels between September 2008 and September 2009 and higher levels of short-time work in July 2009, respectively.

In the 2009 elections, the SPD lost 11% of the votes compared to the 2005 electionsFootnote 7 , whereas the CDU suffered only a minor reduction in their vote share. Scholars analysing electoral behaviour in the 2009 elections debated how the crisis impacted the result of the election. Nevertheless, they agree that the economy was a salient issue at the time (Beckmann et al., Reference Beckmann, Trein, Walter, Bytzek and Roßteutscher2011; Goerres and Walter, Reference Goerres and Walter2016; Trein et al., Reference Trein, Beckmann and Walter2017).

3. Theory and hypotheses

To understand how the economic crisis and STW policy influenced the 2009 German federal elections, we use insights from economic voting research. According to this literature, voters reward incumbents for positive economic developments and punish them for negative ones (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Key, Reference Key1966; Tufte, Reference Tufte1978; Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981; MacKuen et al., Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992; Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck et al., Reference Lewis-Beck, Martini and Kiewiet2013a), either by accounting for past or future economic outcomes (MacKuen et al., Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992, 606-7; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2000). This effect should be particularly pronounced if the responsibility for economic policies is clear – that is, if it is easy for voters to determine who is responsible for economic downturns (Powell and Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Anderson and Hecht, Reference Anderson and Hecht2012).

As our main interest is the impact of the STW policy, we adopt a “policy voting” rather than an economic voting perspective. In times of economic crisis, governments cannot remain passive and do nothing as they are aware of scrutiny by the public. Thus, they try to implement measures to address public concerns and ensure their re-election. In times of crisis, governments can focus on either fiscally conservative (Brender and Drazen, Reference Brender and Drazen2008; Giger and Nelson, Reference Giger and Nelson2011) or fiscally expansive interventions, such as STW (Bechtel and Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Hübscher and Sattler, Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017; Talving, Reference Talving2017). In the following, we focus on expansive policies and explain how STW policies affect the electoral reward for political parties.

3.1. Reward and punishment in the context of an expansive labour market crisis policy

A large body of literature has argued that politicians are aware of and react to popular demands for welfare state provisions (Soroka and Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2005; Brooks and Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2006). Blekesaune and Quadagno (Reference Blekesaune and Quadagno2003) have shown that public support for the welfare state is particularly high among individuals who expect to benefit from such policies (ego-tropic reasoning) and if there is a context of high unemployment (Fraile and Ferrer, Reference Fraile and Ferrer2005).

Following this logic, we hypothesise that incumbent parties profit electorally when implementing expansive labour market policies whenever they face a crisis (Soroka and Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; Bechtel and Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Marx, Reference Marx2016; Hübscher and Sattler, Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017). Put differently, a crisis context increases the demand for social protection, and the government has an incentive to expand welfare interventions to counteract its negative effects. Thus, when facing high levels of unemployment, incumbents have an incentive to implement policy responses that address this problem to avoid being punished on election day for not taking the necessary steps to deal with the economic crisis.

In the case of the 2009 German federal election, STW was a promising way of swiftly and efficiently addressing the adverse impacts of the downturn. STW is firmly anchored in the policy repertoire of continental welfare states (Sacchi et al., Reference Sacchi, Pancaldi and Arisi2011) and can thus be easily implemented. This is exactly what the German government did: faced with a crisis, the government quickly expanded the length, targeting and scope of this measure to buffer the economic downturn and prevent electoral backlash. Therefore, we hypothesise the following:

H1a) Voters in constituencies with higher levels of STW should, ceterisparibus, be more likely to reward incumbents than in constituencies with lower STW take-up (macro-level hypothesis).

However, an alternative prediction can be made if we follow the literature suggesting that voters prefer fiscally conservative over expansive policies during times of crisis (Durr, Reference Durr1993; Sihvo and Uusitalo, Reference Sihvo and Uusitalo1995; Stevenson, Reference Stevenson2001). In the context of general austerity and against the backdrop of the International Monetary Fund interventions in many European countries, voters are likely to be sensitive to the necessity of pursuing financial consolidation and avoiding a public debt explosion. Voters will thus also engage in prospective and socio-tropic reasoning (MacKuen et al., Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992, 606-7; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2000) and disapprove of government if it decides to expand STW, particularly in times of economic slumps. This reasoning corresponds to the more general observation made by Giger and Nelson (Reference Giger and Nelson2011) that governments, particularly right-oriented parties, may actually win votes when retrenching the welfare state. In line with theories emphasising prospective reasoning, we hypothesise the following:

H1b) Voters in constituencies with higher levels of short-time work should, ceterisparibus, be more likely to punish incumbents than in constituencies with lower STW take-up (macro-level hypothesis).

3.2. Partisan differences regarding labour market policies in the context of crisis

An alternative theoretical approach accounts for partisan differences regarding policy interventions. In fact, voters consider some parties to be particularly competent concerning certain policies and use them strategically to attract specific groups of voters (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Bélanger and Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). Hence, voters support a party because of its policy propositions (Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2011; Lewis-Beck et al., Reference Lewis-Beck, Nadeau and Foucault2013b) or because they infer from past experiences (or beliefs) that a party is particularly competent in handling a specific policy challenge (Tilley and Hobolt, Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011). According to the literature on party choice and policy preferences, two competing arguments are plausible regarding the link between voters’ party and policy preferences.

The first argument proposes that social democratic parties tend to represent workers and working-class issues and therefore have the greatest intention to pass protective labour market policies because employment and labour market policies constitute their core competencies. If voters perceive that unemployment is going to be an important problem for the new cabinet, they support social democratic parties in government during an economic downturn because they expect these parties to resolve unemployment issues (Lewis-Beck and Bellucci, Reference Lewis-Beck and Bellucci1982; Broz, Reference Broz, Kahler and Lake2010; Wright, Reference Wright2012). This characterisation applies to insiders, especially in countries such as Germany with a strong labour market dualisation (Rueda, Reference Rueda2006; Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014; Fossati, Reference Fossati2018). In contrast, reforms that reduced unemployment by liberalising the labour market and reducing benefits resulted in declining support for social democratic parties (Schwander and Manow, Reference Schwander and Manow2016). Therefore, we hypothesise the following:

H2a) Social democratic parties in government should be rewarded for expanding STW schemes in contexts of crisis (macro-level hypothesis).

The second argument suggests that conservative parties cater to their electorates by showing competence regarding the stability of prices and financial markets (Hibbs, Reference Hibbs1977; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1982), which implies the following as an alternative hypothesis:

H2b) Right parties in government should be punished for expanding STW in crises (macro-level hypothesis).

3.3. Theoretical chain and empirical implications for the macro and micro levels

Even if a relationship can be identified at the macro level, it is important to assess its micro-foundations since the link between the actual economic situation and the aggregate voting decision may not always be direct. From a micro-level perspective, voters need to perform at least two cognitive links, mediating the connection between the economy and their vote choice (cf. Coleman, Reference Coleman1986). First, voters need to evaluate the effect of the economic context on their personal situation or the national economic situation (i.e. ego- or socio-tropic reasoning) (Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). Second, voters must evaluate the governmentʼs performance and decide whether to hold it responsible for their (the) economic situation. Therefore, they need to identify an incumbent party that is responsible for the negative economic situation or policies they do not approve of (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Blais, Nadeau, Gidengil and Nevitte2003; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013). Third, based on this performance evaluation, they chose whom to vote for.

At the macro level, as illustrated in Figure 3 (Link 1), the reward-punishment hypotheses (hypotheses 1a, 1b) imply that we will find better (or worse) results for both incumbent parties’ vote share at the level of electoral constituencies in case of higher STW take-up. In contrast, the macro data should show wins / losses for the opposition parties (Greens, FDP, and Linke) depending on whether the expectations of the reward-for-intervention (reward-for-fiscal-consolidation) reasoning apply. According to our alternative hypotheses, we expect that only the SPD should be rewarded electorally for high STW because voters consider it most competent regarding labour market policies, even though the social democrats govern together with the CDU. Conversely, according to this logic, the CDU should not profit electorally from STW because its competencies prioritise monetary and financial policies.

Figure 3. Theoretical model linking the micro and the macro levels.

At the micro level (Coleman, Reference Coleman1986; Walter, Reference Walter2010), we connect STW intervention to voters’ personal economic situations (ego-tropic evaluation, Link 2), their evaluations of government performance (Link 3), and their vote choices (Links 3). Therefore, a context with higher STW shares should influence the assessment of the personal economic situations of voters, which, in turn, impact the evaluation of the governmentʼs performance. Consequently, the assessment of government performance should result in vote decisions and support for a particular party. This logic varies according to the hypotheses that we discussed above.

4. Data and methods

To test the hypotheses, we use two different empirical strategies, one at the macro level and one at the micro level. The first analysis focuses on the link between STW and voting behaviour at the constituency level, controlling for unemployment and other relevant confounders at the macro level. Note that the electoral outcome, i.e. the seats, is distributed according to the proportion of the vote share that the parties obtain in the second vote (proportional logic).Footnote 8

The second analysis focuses on the micro level and aims to assess the theoretical chain underlying the postulated macro relationship. To achieve this aim, we use cross-sectional survey data from the GLES (Rattinger et al., Reference Rattinger, Roßteutscher, Schmitt-Beck and Weßels2011 and Reference Rattinger, Roßteutscher, Schmitt-Beck, Weßels, Wolf, Wagner, Giebler, Bieber and Scherer2014)Footnote 9 and combine the pre-and post-election surveys. The surveys were conducted six weeks before and after the federal election in Germany on 27 September 2009. A total of 4288 individuals were interviewed,Footnote 10 and the distributions of survey responses are relatively close to the actual voting results.Footnote 11 The analyses include only the SPD, the CDU/CSU, the Greens, the FDP and die Linke, which are the parties that passed the 5% hurdle necessary to form a parliamentary group in the national German parliament.

4.1. Constituency-level analyses

The dependent variable at the macro level is measured as the percentage change in the average coalition parties’ (CDU/CSU and SPD) electoral outcomes and the average outcome of the opposition parties (Greens, FDP and die Linke) compared to that in the previous election that was held in 2005 in the 299 German electoral constituencies (Figure 3, Link 1).Footnote 12

To measure whether labour market policy intervention affects voters’ choices at the aggregate level, we introduced a variable that captured the share of individuals who newly registered as working on an STW contract as a percentage of all employees in a specific region between September 2008 and September 2009. We then merged municipal-level data obtained from the Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2010) for the corresponding electoral region with the STW data. To control for poor labour market performance, we included the regional unemployment rate change (September 2008 – September 2009, cf. Figure 2) and the 2009 absolute unemployment level in the 299 constituencies (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2010). The raw data measured STW at the municipal level (Landkreise), and we merged the data to the constituency level using ArcGIS software.Footnote 13 Moreover, we controlled for East Germany, the regional participation level, and the 2005 vote shares of both CDU/CSU and SPD.

For this analysis, we estimated seemingly unrelated regressions, which produced estimates for each party separately but accounted for the correlations among the error terms. This step was necessary because the decision to vote for one party cannot be considered independently from the choice not to vote for another party.

4.2. Analyses connecting the constituency and the micro level

The second empirical test analysed the micro-foundations (Coleman, Reference Coleman1986; Walter, Reference Walter2010) of our argument by running a series of regression models that operationalised the different analytical linkages connecting the macro level to the micro level (cf. Figure 3, Links 2, 3 and 4). The context hypothesis (Link 2) links the constituency-level STW rate (macro) to the respondents’ evaluations of their personal economic situations (micro). In turn, this ego-tropic evaluation triggers the individual evaluation of government performance (both micro-level variables, Link 3). The last step involves the re-aggregation of micro-level preferences that are expected to influence the electoral outcome. We tested Link 4 by regressing individual vote choice on the respondents’ government evaluations (both micro-level variables). If all these relationships pass the statistical tests, our argument about the macro-level relationship of STW intervention and the impact on electoral outcomes can be corroborated.

We used different dependent variables to test these analytical links. First, we assessed the impacts of context factors on the individual evaluations of personal economic situation (Figure 3, Link 2). As suggested by MacKuen (1992), we included retrospective (vn178),Footnote 14 current (vn179) and prospective (vn181) ego-tropic thinking as well as average scores (0=very bad to 4=very good) for all three indicators. Subsequently, we tested Link 3 by regressing the continuous variable of satisfaction with the governmentʼs performance (vn112) on the ego-tropic assessment, i.e. the previous dependent variable. Finally, concerning electoral behaviour (Figure 3, Link 4), we considered the five main parties and excluded non-voters. Electoral choice focused on the second vote (proportional rule) and combined the respondents’ intentions to vote in the pre-election sample (v254_2A) and the reported vote choices in the post-election sample (n169_2A). To achieve this aim, first, a dependent variable distinguishing the governing parties (SPD and CDU/CSU=1) and the opposition (die Linke, Greens, FDP=0) was created. Second, we recoded a nominal variable to test for different preferences concerning the incumbent parties by distinguishing between votes cast for the SPD (=0), the CDU (=1), and the opposition (=2). Our sample contained 2545 observations.Footnote 15

The micro-level models included a number of possible confounders that account for basic sociological differences among voters (Falter and Schoen, Reference Falter and Schoen2005). Specifically, the models controlled for gender (ref. male, v1), age (in years, v436B), and age squared to account for nonlinear effects of electoral preferences. Education was modelled as continuous (5 levels, vn9A), whereas personal unemployment (vn17) and union membership (v337) were included as dichotomous variables. We also included a measure of socio-tropic reasoning by creating an index that averaged the assessment of the expected past (vn182), current (vn184), and future (vn185) development of the national economy. We distinguished individuals with very strong or strong party identification from individuals with average or lower levels of party identification (vn136). Moreover, several political variables, including level of political interest (5 levels, vn217), individual position on the left-right dimension (1=left, 11=right, vn190), and the square of the left-right position, were modelled. Controls were also added for whether the respondent lived in East Germany and for the data sampling strategy, i.e. the pre- or post-election survey wave (recoded from “Erhebung”). To complete the model, we added changes in the STW rate and in unemployment at the macro level.

The empirical strategy consists of estimating hierarchical linear models that account for the nested data structure (Steenbergen and Jones, Reference Steenbergen and Jones2002; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal2008). Thus, we estimated multilevel logit regressions for the decision to vote either for the governing party or for the grand coalition and multinomial logit models with clustered standard errors for the choice among SPD, CDU and the opposition.

5. Results of the empirical analysis

5.1. Constituency-level evidence

Table 1 shows the results for the macro-level analyses. Model 1 shows that a high level of STW take-up boosts the governing coalitionʼs electoral support. In other words, voters rewarded the incumbent coalition of SPD and CDU-CSU in the 2009 German election, whereas they punished the opposition parties (10% significance).

Table 1. The effects of short-time work at the constituency level on the German electoral outcome in 2009 (Link 1)

Standard errors in parentheses, seemingly unrelated regressions, macro-level.

Dependent variable: absolute change in electoral outcome per party (2009-2005).

° p<0.1, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Regarding the control variables, we find that a high change in unemployment compared to one year prior to the election decreases the coalitionʼs support. Interestingly, high absolute levels of unemployment do not seem to affect government parties. For the opposition, the situation is reversed: they win when unemployment changes are large but lose when absolute unemployment levels are high. In sum, Model 1 corroborates the expectation that voters favour extensive STW intervention in the context of a crisis.

To analyse the second set of hypotheses, i.e. to test whether there are partisan effects “hidden” in the finding that both incumbent parties are rewarded for STW intervention, we disentangled the party-specific results for the government by modelling the performance of the CDU/CSU and the SPD separately (Model 2). The results indicate a difference between the two governing parties. More STW take-up ameliorates the electoral performance of the conservative CDU/CSU, although the effect is statistically significant only at the 10% level. The effect is stronger for the SPD, whose voters clearly rewarded them for labour market intervention. In other words, the party lost less electoral ground in constituencies with high STW.

Moreover, the results reveal that conservatives suffered electoral punishment in constituencies with higher levels of unemployment change or with high absolute unemployment levels. As a member of the governing coalition, the SPD also lost electoral ground in areas with high unemployment changes but gained in regions with high absolute levels of unemployment. A striking difference between the two governing parties is that the SPD tended to lose votes in East Germany, whereas the CDU/CSU gained votes in those regions compared to 2005.

Overall, these analyses support a reward-punishment logic for STW policies. Voters reward both governing parties for higher STW, but they make a clear partisan distinction and attribute more credit to the SPD. These results suggest that voters evaluate STW policy action retrospectively and especially reward the party that is more competent and primarily responsible for implementing policies that support insiders (Rueda, Reference Rueda2007; Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014, Fossati, Reference Fossati2018). In terms of the theories previously outlined, these results show that voters favour extensive labour market policies and reward governing parties for them, especially social democratic parties in government. We did not explicitly test whether voters prefer STW policies over domestic austerity measures, but the findings of this analysis indicate that this could be the case, which will be an interesting venue for further research.

5.2. Micro-level evidence

We now turn to the analyses of the theoretical chain that connects the macro and micro levels. The purposes of these analyses are to link STW and unemployment to the aggregate electoral outcome discussed above and to test the contextual (Figure 4, Graph 1), individual (Graph 2) and aggregation links (Graph 3) with micro-level data.

The first graph (Link 2) shows that increasing STW in the constituency significantly affects the evaluation of a respondentʼs economic situation in a positive direction (see Tables S6-S10 in the Supplementary Materials). In fact, on average, the higher the share of STW is in the constituency, the better an individual evaluates his/her personal economic situation. Concerning the control variables, we find that a high absolute unemployment level (non-significant) and an increase in unemployment at the macro level decrease voters’ satisfaction with their personal economic situation, as do individual-level variables that capture labour market risk exposure, especially personal unemployment.

The coefficients in the second graph (Link 3) suggest that the better voters evaluate their personal economic situation, the more satisfied they are with government performance. Concerning the control variables, a higher STW incidence increases satisfaction with the government (10% significance level). Conversely, a higher increase in unemployment at the regional level and high absolute unemployment levels lower voter satisfaction with government performance.

Finally, we tested the reaggregation link (Graph 3). The model indicates that respondents who evaluate government performance positively are more likely to vote for the coalition than for the opposition (base outcome). In these models, however, the effects of STW and unemployment change are no longer significantly different for the coalition and the opposition, and only a high absolute unemployment level makes voting for the government more likely.

In sum, our analyses at the individual level indicate that the postulated theoretical chain holds as all the different independent variables are significantly related to the previous linkage. We also find that at the micro level, STW affects vote choice indirectly through both ego-tropic and government evaluations. However, we do not find a direct effect of STW on voting for the coalition government. Concerning the unemployment controls, the results show that unemployment change affects both ego-tropic and government performance evaluations negatively but that only absolute unemployment change has a rewarding effect on the outcome of the coalition. Overall, our results suggest that both members of the governing coalition benefit from labour market policy intervention, although the SPD profits more, and both coalition members are generally punished for a bad economic situation.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we started from two sets of hypotheses to explain how labour market policy intervention is linked to electoral behaviour at the macro level. First, we hypothesised that, on the one hand, governing parties profit electorally from higher STW because voters want compensation and therefore expansive policies in times of crisis. On the other hand, voters might punish governing parties for STW policies because they fear their future cost and prefer austerity measures. Second, we hypothesised that there is a partisan difference and that the social democratic SPD especially profits from STW electorally because voters regard them as particularly competent in the matter and responsible for the implementation of these policies.

At the constituency level, our results show that higher STW rates correlate with more support for both governing parties but especially for the social democrats when controlling for the difference and level of unemployment, the region, and the party vote share in the constituency during the 2005 elections. This evidence corroborates the hypothesis that voters support expansive labour market policies during times of crisis (H1a) because they want the government to spend money to protect citizens. Furthermore, the finding supports the hypothesis that social democratic parties in particular profit from higher STW take-up (H2a) because voters associate these policies with the core competencies of this left party.

The individual-level analysis somewhat relativises this finding. We show that higher STW leads to a better individual evaluation of the personal economic situation, which leads to a better evaluation of government, which, in turn, leads to a higher probability of voting for the government coalition. Nevertheless, the individual-level analyses do not show a direct link between a higher STW rate in the constituency and more votes for the governing coalition.

Our results contribute to the literature by demonstrating how voters reward governing coalition parties for expansive labour market policies during times of crisis. During the German elections of 2009, the social democrats especially profited from STW policies. Nevertheless, these anti-crisis policies were not sufficient to avoid major losses, which the SPD suffered (11.2%). We demonstrate that STW programmes generated some electoral rewards for the social democrats, but we also show that there is only an indirect influence of STW in the constituency and individuals’ intentions to vote for the governing parties. Electoral losses for social democrats were particularly high in East Germany, where the level of unemployment is higher overallFootnote 16 (Trein et al., Reference Trein, Beckmann and Walter2017, 421) but STW rates are lower (BWL, 2009). Clearly, STW policies address labour market insiders in the richest region of the country, where voters tend not to reward the SPD for these policiesFootnote 17 (Figure 2; BWL, 2009). STW policies signalled to voters in poorer regions that even in times of crisis, the richest regions are served first, for which social democrats received the blame. Our macro-level models support this interpretation as the SPD lost in the eastern part of Germany, whereas the CDU gained in that region (Table 1, Model 2).

7. Conclusions

This article addresses the questions of whether and how STW policy affected the electoral fortunes of political parties in the 2009 federal German elections, which coincided with the global economic recession. That election is a particularly interesting case because the two largest German parties – the conservative Christian democratic CDU and the social democratic SPD – formed a grand coalition in the period prior to the election. Furthermore, the election is interesting as anti-crisis policies and economic conditions varied strongly between German constituencies. This constellation allows for the testing of several hypotheses of how STW intervention affects the electoral fortunes of the governing parties in a context of economic downturn. Notably, it permits analyses of whether voters reward incumbents for anti-crisis policies and whether left or right parties in government are treated the same way. We analysed these questions using empirical tests at the macro (constituency) and micro (individual) levels using a unique dataset that combines unemployment and STW rates in the 299 electoral regions with information from the German 2009 pre- and post-electoral survey.

Our macro-level analyses show that the SPD in particular gained electorally in regions with high STW rates. Overall, however, this policy measure was not enough to receive the symbolic reward for a successful anti-crisis policy. Our individual-level analyses demonstrate that there is only an indirect link between STW policy and voting intentions for the social democrats that runs through the ego-tropic evaluation of voters’ economic situation and their evaluation of government performance. Therefore, precautionary labour market policies are not sufficient to avoid further losses in votes for the SPD.

Our results are also in line with researchers who suggest that voters reward social democratic parties for labour market insider policies (Rueda, Reference Rueda2006; Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014, Fossati, Reference Fossati2018) but tend to favour right parties in times of economic downturns (Barnes and Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2012; Kayser, Reference Kayser2009; De Neve, Reference De Neve2014; Lindgren and Vernby, Reference Lindgren and Vernby2016). Overall, we demonstrate that social democratic incumbents cannot compensate for losses that are due to their shrinking core constituency against a right incumbent even a context of labour market downturn and with a massive and successful investment in labour market policy. In the German case, the history of Agenda 2010, which alienated voters from the social democrats (Schwander and Manow, Reference Schwander and Manow2016), clearly reinforced this dynamic. In fact, the 2009 election, which occurred against the backdrop of a major economic crisis, induced voters to punish the social democrats.

To conclude, this article also opens avenues for further research. For example, as our results are merely correlational, scholars should analyse parts of the theoretical chain to determine causation and posit whether causal effects can be found between STW and voting results at the macro level. In addition, future scholarship should assess how other labour market policy instruments, such as a minimum wage, or tax relief also impact the electoral fortunes of social democratic parties.

Acknowledgments

Both authors contributed equally to this work. We thank Stefanie Walter and Ruth Beckmann, whose ideas contributed in many ways to the writing of this paper. We especially want to thank Ruth for creating the dataset with the contextual information on unemployment rates and short-time work in the constituencies. We thank Patrick Emmenegger, Rafael Lalive, the participants of the Labour Market Colloquium at the University of Lausanne, and the participants of the Social Policy Panel at the Swiss Political Science Association for their very helpful feedback on previous versions of this paper. All remaining errors are ours.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279420000070