Introduction

Theories laying out why terrorists use suicide bombings as an attack methodology are complex and literature on this topic is diverse with some of the most prominent hypotheses receiving mixed empirical support. Reference Horowitz1,Reference Pedahzur, Martin, LaFree and Freilich2 A suicide bombing can simply be defined as an attack in which an individual knowingly takes their own life with the intention of killing others, while deploying an explosive device. Reference Markovic3 Suicide bombings share some universal fundamental characteristics: depending on the type of bomb and attack type, they can be inexpensive and effective, requiring little expertise and few resources to cause significant damage, and can be logistically relatively uncomplicated with guaranteed media coverage while showing a commitment to the cause. Reference Hoffman4–Reference Kiras6

While suicide bombings in the context of warfare have existed throughout history, the first modern suicide bombing targeted the Iraqi Embassy in Beirut in December 15, 1981. Reference Vallance7 The tactic gained traction after Hezbollah targeted the US Marine Barracks and French Paratroopers in 1983, killing over 300. During the Al Aqsa Intifada, Palestinian groups used suicide bombings effectively, increasing the number of suicide bombings world-wide. There was an exponential rise in such attacks in the decade following the initiation of the War on Terror. Reference Kapusta8 After the 2001 suicide terrorism attacks in the US on 9/11, and the subsequent military invasion in Afghanistan and Iraq, these events systematically transformed this once unique tactic of political violence into a prominent attack methodology for terrorist groups. Reference Helmer9,Reference Ahmadzai10 The health care implications of terrorist attacks are a growing concern amongst Disaster Medicine and Counter-Terrorism Medicine (CTM) specialists. Reference Court, Edwards, Issa, Voskanyan and Ciottone11

This study is an epidemiological examination of all terrorism-related bombings sustained from 1970-2019, comparing the rates of fatal injuries (FI) and non-fatal injuries (NFI) between suicide bombing attacks (SBA) versus non-suicide bombing attacks (NSBA).

Methods

Data collection was performed using a retrospective database search through the Global Terrorism Database (GTD). 12 This database is open-access, with publicly available data collection methodology utilizing artificial intelligence that identifies events from news media around the world daily, as confirmed by human evaluation of the events by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (College Park, Maryland USA). 13 The GTD defines terrorist attacks as: “The threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” The GTD database does not include acts of state terrorism. The GTD contains no personal identifiers for victims and links specific events to open-source news articles.

The GTD database was downloaded and searched using the internal database search functions for all events that occurred from January 1, 1970 - December 31, 2019. Years 2020 and 2021 were not yet available at the time of the study. Bombing/explosion as a primary “attack type” and explosives as a primary “weapon type” were selected for the purpose of this study, and events were further sub-classified as either “suicide attack” or “non-suicide attack.” Attack and weapon type classifications were pre-determined by the GTD.

Results were exported into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA) for analysis. Attacks met inclusion criteria if they fulfilled the three terrorism-related criteria below, as set by the GTD. Ambiguous events were excluded when there was uncertainty as to whether the incident met any of the criteria for GTD inclusion as a terrorist incident. These criteria were determined within the database and not by the authors:

-

Criterion I: The act must be aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal.

-

Criterion II: There must be evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to a larger audience (or audiences) than the immediate victims.

-

Criterion III: The action must be outside the context of legitimate warfare activities (ie, the act must be outside the parameters permitted by international humanitarian law, particularly the admonition against deliberately targeting civilians or non-combatants).

Results

There were 82,217 bombing/explosion terrorist attacks using explosives documented during the study period with 135,807 fatalities and 352,500 NFI. The mean FI was 1.65 per event and mean NFI was 4.29 per event (Table 1).

Table 1. Fatal Injuries and Non-Fatal Injuries by Bombing/Explosion

Suicide bombings attacks inflicted higher FI and NFI counts than NSBA (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Suicide versus Non-Suicide Bombing Attacks: Mean Fatal and Non-Fatal Injuries.

A total of 5,416 events (6.59% of all events) were sub-classified as SBA causing 52,317 FI (38.52% of all FI) and 107,062 NFI (30.37% of all NFI). Mean SBA FI was 9.66 per event and mean SBA NFI was 19.77 per event (Figure 1).

A total of 76,801 events (93.41% of all events) were NSBA causing 83,490 FI (61.48% of all FI) and 245,438 NFI (69.63% of all NFI). Mean NSBA FI was 1.09 per event and mean NSBA NFI was 3.20 per event (Figure 1).

Target Types

Private citizens and property (26.8%) were the most common target types in NSBA, followed by business (15.1%), police (12.3%), and government entities (10.0%; Table 2).

Table 2. Top 10 Target Types in Non-Suicide Bombing Attacks

Conversely, SBA most commonly targeted police (21.9%), followed by private citizens and properties (20.6%), military (12.2%), and government (10.9%; Table 3). While police were most commonly targeted, the mean FI and NFI inflicted on private citizens and properties (31.49 and 91.42, respectively) were over three-times higher in comparison (Table 3). The highest mean FI (49.04) and NFI (166.61) in SBA were related to attacks on transportation modalities.

Table 3. Top 10 Target Types in Suicide Bombing Attacks

Regional Breakdown

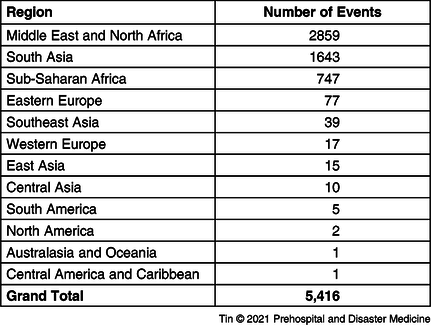

A total of 26,126 NSBA were recorded in the Middle East and North Africa, followed by 18,996 events in South Asia, 8,542 events in South America, and 7,645 in Western Europe (Table 4). A total of 2,859 SBA were recorded in the Middle East and North Africa, followed by 1,643 events in South Asia, 747 events in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 77 events in Eastern Europe (Table 5).

Table 4. Regional Breakdown of Non-Suicide Bombing Attacks

Table 5. Regional Breakdown of Suicide Bombing Attacks

Discussion

Suicide bombings provide the perpetrators with strategic and tactical advantages. From a strategic standpoint, groups use suicide bombings as a method of coercion. They can also be used to instill fear within a populace or to gain political concession. A primary example of strategic gains occurred following the Hezbollah attacks on the US Marine and French Paratrooper barracks in Beirut in 1983, with the US and French pulling their troops from Lebanon afterwards, proving that the tactic was effective in attaining the organization’s goals. Reference Markovic14

Suicide bombing attacks are tactically harder to defend against and inflict a higher number of casualties than other forms of terrorism. For example, although suicide bombings accounted for less than one percent of all terrorist attacks perpetrated during the Al Aqsa Intifada (Second Intifada), they accounted for fifty percent of the casualties. Reference Ganor15,Reference Kimhi and Even16 Suicide bombers are also considered “smart bombs.” They can move, change directions, infiltrate, or change time and location of targets in ways stationary bombs cannot. Furthermore, no exit strategies are needed from a planning perspective. Stationary bombs, if discovered, can be isolated and deactivated, whereas suicide bombers may still be able to detonate on the spot, even if the intended target is not reached, though premature detonation leads to lower victim counts. Reference Almogy, Belzberg, Mintz, Pikarsky, Zamir and Rivkind17 Additionally, groups may use suicide bombings as a means of targeted assassination, which also may lead to lower victim counts.

By virtue of their ability to carry out attacks where and when they choose and migrate towards large crowds relatively undetected, SBA are more lethal, more efficient, and harder to detect. Furthermore, the unpredictability and methodology of suicide bombings can undermine public morale and inflict psychological damage to the population, far beyond the physical threat or damage it caused. Reference Grimland, Apter and Kerkhof18

The high rates of fatalities and NFI per SBA targeting transportation modalities indicate the compounding factors of targeting a closed-space (ie, bus or train) and the utilization of a “smart-bomb” that can move, change positions, and aim for an area for detonation with the greatest amount of impact. Similarly, suicide bombers can infiltrate dense crowds and areas where citizens commonly gather, like marketplaces, shops, restaurants, or internally displaced person (IDP) camps for maximum impact, as demonstrated by the high number of FI and NFI per attack on private citizens and properties.

Soft targets like civilians and systems frequently utilized in the daily life of citizens (ie, transportation, religious institutions, and businesses) are more vulnerable to SBA than traditional hard targets, such as police and the military. Higher FI and NFI counts with SBA as a methodology are likely to gain the attention of a wider audience, spread fear into the direct victims of the attack and those who may feel vicariously victimized abroad, and cause wide-spread psychological distress within the community. Furthermore, research suggests that women are potentially more effective in their attacks than men because of their ability to covertly infiltrate dense civilian areas and hit targets where groups of people generally gather, and are therefore seen as a methodology with a perceived tactical advantage by terrorist organizations. Reference Davis19–Reference Pape22 The sharpest increase in female suicide bombers has been seen in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, Nigeria in particular, with some estimates placing women at over one-half the number of bombers. Reference Warner and Matfess23 Given the high impact of female bombers and their ability to blend in well with soft targets, it is possible that other groups will increase the utilization of females. It would therefore be beneficial for CTM specialists and first responders to be aware of “hot spots” of female suicide bombers as part of their risk assessment strategies. Reference Galehan24

The approach to victims of SBA leans on the guidelines for trauma victims in general, though special considerations should include the large number of victims, the combined effects of penetrating trauma, blast injury, and burns, the numerous penetrating wounds sustained by each victim, and the need for mass blood transfusions and burn management. Reference Almogy, Belzberg, Mintz, Pikarsky, Zamir and Rivkind17,Reference Bala, Kaufman and Keidar25

Bombs may be composed of a variety of sources, including camping fuel, Ammonal, Semtex, petrol, jet fuel, and dynamite, and loaded with nails, nuts, bolts, glass, or other “frags,” inflicting secondary blast injuries along with any glass, concrete, or wood from surrounding structures or environments. Reference Arnold, Halpern, Tsai and Smithline26,Reference Arnold, Tsai, Halpern, Smithline, Stok and Ersoy27

Studies have suggested injuries to four or more body areas, and specific types of injuries such as facial and skull fractures and peripheral vascular injury, can herald severe trauma and the need for intensive care unit admission. Reference Bala, Willner, Keidar, Rivkind, Bdolah-Abram and Almogy28 This has led to calls to incorporate these injury parameters into trauma triage protocols, given the potential bottleneck of intensive care availability.

Beyond conventional mass-casualty care, special considerations unique to suicide bombing such as the implantation of biological material from the suicide bombers themselves (also known as “human remains shrapnel”) need to be taken into account. Reference Turégano-Fuentes, Caba-Doussoux and Jover-Navalón29

Forensic documentation, preservation of evidence, suspect tissue identification and viral status, victim counselling, and post-exposure prophylaxis are also important considerations. Reference Kao and McAlister30

Blast injuries unique to terrorism that require complex and often prolonged critical care with input from various sub-specialties present a therapeutic challenge to clinicians and a resource challenge to hospitals and health care systems. Reference Chim, Yew and Song31–Reference Bala, Shussman, Rivkind, Izhar and Almogy33 Terrorist attacks are also unique in their intentionality to kill or damage compared to other man-made disasters, and CTM specialists aim to better understand the health care repercussions of such events in order to streamline prioritization of immediate treatment, patient evacuation, and hospital care. Reference Tin, Hart and Ciottone34,Reference Tin, Hart, Hertelendy and Ciottone35 Furthermore, health care responders and hospitals are themselves vulnerable to terrorist attacks and risk reduction strategies should be considered. Reference Tin, Hart and Ciottone36

Addressing the health care complexities within CTM requires collaboration among specialists and experts in Disaster Medicine, counter terrorism, tactical medicine, and law enforcement to ensure streamlined, coordinated strategies in dealing with future attacks. Reference Tin37

Limitations

The GTD is a comprehensive record of global events. It is maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, and is the basis for other terrorism-related measures, such as the Global Terrorism Index (GTI). Reliance wholly on the GTD is partially mitigated by confirmation with other lay sources, and searches for other online searches, but if there are incidents not reported in the GTD, this could limit the veracity of the findings. One of the main limitations of the GTD dataset is their Criterion III, which removes all suicide bombings that occurred within the context of war. Another classification in the GTD dataset “Doubt Terrorism Proper” will exclude cases based on five alternate designations. The two most relevant to suicide bombings are “insurgency/guerrilla actions” and “intra/inter group conflicts,” which may have terrorist attacks attached to these but will not be counted for the purposed of the GTD dataset. Although publicly available datasets, such as Chicago Project on Security and Threats (CPOST; Chicago, Illinois USA), report on a greater number of suicide bombings, they do not collect datasets on other terrorist events. Therefore, for comparative purposes, using the GTD was the publicly available dataset. Furthermore, injuries and fatalities were cross-matched with news records rather than formal hospital or coroner reports, so rely on the completeness and accuracy of these sources.

Conclusion

Suicide bombing attacks are a unique terrorist methodology that can inflict wide-spread psychological damage as well as significantly higher death and injury tolls when compared to more traditional NSBA. They have been increasing in popularity amongst terrorist organizations and groups, and CTM specialists need to be aware of the unique injury patterns and potential risk mitigation strategies associated with SBA depending on the target type, location, and gender of the perpetrator.

Conflicts of interest/funding

The authors have no conflict of interest or financial disclosure to declare.