Introduction

Diffuse inflammation of the external auditory meatus (otitis externa) has been estimated to have an annual UK primary care prevalence of 1 per cent, with 3 per cent of sufferers referred to secondary care.Reference Rowlands, Devalia, Smith, Hubbard and Dean1 Key recommended treatments are ototopical drops, analgesia and avoidance of precipitating factors.Reference Kaushik, Malik and Saeed2

We were concerned with the increased promotion of fluoroquinolone drops for the treatment of ear infections because they are still a key part of systemic therapy for necrotising otitis externa, and resistance driven by prior topical use may reduce efficacy in severe infection. In this study, we therefore aimed to explore the following. In primary care, we aimed to analyse: (1) otitis externa decision-making, guideline content, awareness and adherence, and (2) consultation rates and costs. In secondary care, we aimed to analyse: (1) otitis externa and necrotising otitis externa inpatient activity, and (2) the antimicrobial resistance profile of otitis externa-related bacterial isolates and content of available guidelines.

Materials and methods

Relevant components of the study were registered with the Clinical Effectiveness and Audit department of the Newcastle hospitals.

Data sources

Primary care

For primary care, the data sources were as follows. The first data source was from an otitis externa decision-making in primary care online survey (Figure 1) of a convenience sample of general practitioners and general practitioner trainees in North East England. It comprised research contacts in 12 clinical commissioning groups in North East England and North Cumbria. The office that distributed the questionnaire was not able to provide the total number of general practitioners to whom the questionnaire was sent. The questionnaire was designed based on the contents of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical knowledge scenario. It was then discussed with and revised by the senior author and then piloted in a group of general practitioner trainees. The final version was posted online. A link to the survey was emailed to 500 general practitioner trainees in North East England.

Fig. 1. The otitis externa questionnaire for primary care. NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

The second data source for primary care was the otitis externa workload estimated from a primary care diagnostic database in North West England3 that covered 23 general practitioner practices with 152 238 patients. We assessed consultations over a 12-month period from 2015 to 2016 stratified by age: 0–18, 19–64 and over 65 years.

The second data source for primary care was the National Health Service Digital website,4 which was interrogated for any trends in community prescription of otitis externa topical preparations in the British National Formulary.

Secondary care

For secondary care, the data sources were as follows. The first data source was Hospital Episode Statistics5 data in England for secondary care of otitis externa and necrotising otitis externa admissions from 2002 to 2020.

The second data source was the antimicrobial resistance patterns of 162 consecutive bacterial otitis externa-related bacterial swab isolates at the Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, from 2 June 2017 to 29 June 2018. The sensitivity testing results were interpreted according to systemic breakpoints. When using topical therapy, the higher concentrations supplied to the ear can often overcome a degree of non-susceptibility, as long as there is some activity in vitro.

Guidelines

Ten online UK otitis externa guidelines were assessed for: (1) ease of use, (2) concordance, and (3) inclusion and quality of any prevention advice.

Results

Primary care

Otitis externa decision-making in primary care

Our 101 respondents (Table 1) showed that 42 per cent of general practitioner trainees and 54 per cent of general practitioners prescribe oral antibiotics, most often amoxicillin (14 of 27 trainees) and flucloxacillin (12 of 19 general practitioners). Systemic treatments were used similarly (40 per cent) among the 20 respondents who had an ENT trainee placement.

Table 1. Summary of surveys of general practitioner trainees and general practitioners

Workload of otitis externa

The primary care data are summarised in Table 2. The annual incidence of otitis externa in the North West primary care catchment area was 1.25 per cent. Extrapolation to the population of England in 2015 equates to around 700 000 patients.

Table 2. Incidence of otitis externa by age group*

*North West Primary Care Data, n = 152 238

Cost of topical preparations

From 2006 to 2016, there was a steady increase in total prescription costs for community otitis externa topical prescriptions, from £7 million to £11 million (Table 3). Expenditure on ciprofloxacin drops rose most rapidly, increasing 12-fold in 3 years.

Table 3. National Health Service indicative price of topical ear preparations ranked by 2016 total expenditure

*Available over the counter; †over the counter price; ‡price quoted from pharmacy. NHS = National Health Service; IP = indicative price

Secondary care

Hospital Episode Statistics data

In-patient otitis externa admissions in England showed a 122 per cent overall increase from 2611 patients in 2002 to 5786 patients in 2020 (Table 4). In 2002 to 2003, the mean length of stay was two days. The 2019 to 2020 bed occupancy equates to approximately 3.1 million at £346 per day.6 Necrotising otitis externa workload increased by 950 per cent in the same interval, at a cost of approximately £6.1 million.

Table 4. Hospital Episode Statistics data for admissions with otitis externa and necrotising otitis externa

*Finished consultant episode bed days

Antimicrobial resistance profile

Pseudomonas species were isolated in almost 80 per cent (128 of 162) of the consecutive hospital swabs. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from 41 swabs (25.3 per cent). Three out of five isolated streptococcus species were resistant to gentamicin. Multiple pathogens were grown from 20 swabs. One pseudomonas isolate was resistant to all antibiotics tested. Table 5 summarises resistance patterns in isolated bacteria according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines for systemic antibiotic use.7

Table 5. Resistance patterns in 169 isolated bacteria

*n = 128; †n = 41

Guidelines

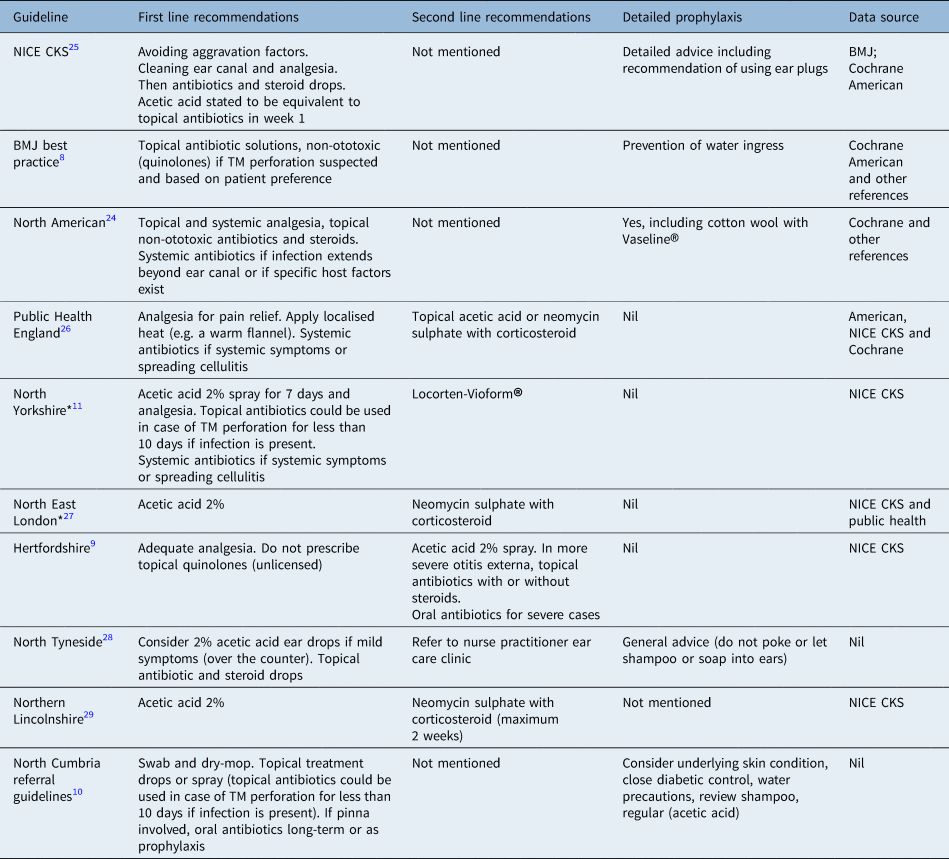

The guidelines reviewed (Table 6) show discrepancies in first line and second line recommendations. SomeReference Ghossaini8 lacked clarity concerning prophylaxis (i.e. water exclusion from the ears). Some lacked specificity; for example, the local Hertfordshire guidelines9 advise consideration of an oral antibiotic if otitis externa is ‘severe’ but without defining severity. Suspected tympanic membrane perforation was associated with considerable divergence: some guidelinesReference Ghossaini8 recommend non-ototoxic topical treatment while others10,11 state any topical antibiotic class can be used for up to seven days.

Table 6. Comparison of 10 commonly used otitis externa UK guidelines

*This is prescription guidance. NICE CKS = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Knowledge Scenario; BMJ = British Medical Journal; TM = tympanic membrane

Discussion

This study is a multi-method review of several facets of the diagnosis and management of otitis externa. It included prospectively assessed data from general practitioners, national level data for both primary and secondary care, and detailed investigations into the microbiology and cost implications of otitis externa.

The 101 general practitioners who responded to the survey reported frequently prescribing oral antibiotics for otitis externa. General practitioner consultations for otitis externa increased 25 per cent over 15 years. General practitioner ototopical preparations cost over £11.3 million in 2016. The 1.25 per cent otitis externa prevalence we estimated in North West England is similar to a prior UK reportReference Rowlands, Devalia, Smith, Hubbard and Dean1 and higher than the prevalence in the USA.12 Hospital admissions for necrotising otitis externa increased 700 per cent over 14 years, and otitis externa admissions increased in number and duration.

Our survey of general practitioners and general practitioner trainees highlighted a number of significant issues around implementing otitis externa guidelines, which have also been noted in the USA.Reference Bhattacharyya and Kepnes13 Most of our respondent general practitioners report having accessed guidelines, yet 42 per cent of surveyed general practitioner trainees and 51 per cent of general practitioners would prescribe oral antibiotics, which is notably higher than previous surveysReference Rowlands, Devalia, Smith, Hubbard and Dean1,Reference Collier, Hlavsa, Piercefield and Beach14,Reference Pabla, Jindal and Latif15 and contrary to most guidance. Not only is oral treatment less effective than topical treatment,Reference Yelland16 it encourages the development of antimicrobial resistance.Reference Simpson and Markham17 There was also some variation in terms of prescription of topical agents and the type of agent prescribed. A number of factors could influence the selection of topical agent in primary care, such as being mentioned in available guidance, cost and availability in local formularies. In total, around a quarter will routinely prescribe EarCalm® spray (acetic acid). It is possible that its cost (£6–8 per bottle) might be a contributing factor as it is relatively expensive in comparison to other topical preparations as shown in Table 3.

• Otitis externa is the commonest cause of ear discharge in adults

• Otitis externa carries a significant financial burden

• Recommended first line treatment for otitis externa is with topical preparations

• Otitis externa incidence and rate of complications are increasing

• Oral antibiotics in primary care are used commonly for treatment

• Available guidance is inconsistent

Hospital Episode Statistics data confirm a marked increase in otitis externa secondary care referrals. Potential factors may include increased antimicrobial resistance including to neomycin (Otomize®),Reference Cantrell, Lombardy, Duncanson, Katz and Barone18 the observed steady increase of earphone or headphone users in the UK from 12 million in 2013 to 16 million in 2016,19 and the increased popularity of showering which may allow more water ingress into the external auditory canal.

The frequency of resistance to gentamicin (18 per cent of pseudomonas species) is noteworthy as it is one of the more widely prescribed ototopical agents. Resistance to ciprofloxacin (7 per cent in this study) was higher than in a previous report.Reference Berenholz, Katzenell and Harell20 As otitis externa is so common, guideline adherence is important to achieve good antimicrobial stewardship.21 The rapidly expanding use of ciprofloxacin drops (National Health Service Digital prescribing data) is concerning. The use of topical fluoroquinolones is being actively promoted by pharmaceutical companies on the basis of a relatively low ototoxicity compared with aminoglycoside preparationsReference Ghosh, Panarese, Parker and Bull22 and the fact that non-specialists may find it difficult to exclude a tympanic membrane perforation. However, such increased use will increase the risk of evolved resistance to fluoroquinolones. This would deprive clinicians of one of very few oral treatments for necrotising otitis externa,Reference Chen, Chan, Chen, Chin-Kuo and Che-Ming23 potentially leading in turn to longer in-patient admissions for intravenous therapy.

We found marked variation in guidelines. NICE has a ‘clinical knowledge skills document’ rather than formal guidelines. This less structured format leaves more room for interpretation. Neither NICE nor the North American guidelines recommend topical antibiotics as first line treatment, while five of six local and regional guidelines more explicitly recommended acetic acid as a first line treatment. Avoidance of topical antibiotics aligns with the UK Commissioning for Quality and Innovation initiative to tackle antimicrobial resistance.24 Prophylactic measures against otitis externa are alluded to only in some of the available guidelines.10,12 Even where the use of earplugs or cotton wool smeared with water repellent materials, such as Vaseline® (petroleum jelly)Reference Ghossaini8 are referred to, consistency and adequate explanation are lacking.25

Limitations

We sampled selected guidelines and were not in a position to explore the reasons behind their variation, although lack of robust evidence is a likely contributor both to their deficiencies and to lack of adherence by community healthcare professionals. A further limitation is the local nature of the microbiological data, which may not be reflected nation-wide, but could form the basis for similar studies at other institutions.

Conclusion

In this study, we highlighted a number of important issues in otitis externa practice, including the increasing disease burden, complications and cost of topical treatment, the overuse of oral antibiotics in primary care and the promotion of broad-spectrum topical quinolone antibiotics in the community. The proportion of otitis externa isolated with an antibiotic resistant pathogen in this study is greater than has been reported in other studies. There is a need for improvement in evidence-based guidelines and their implementation in otitis externa, especially in terms of the avoidance of oral antibiotics.

Further research is needed to explore the perceptions of stakeholders concerning the misuse of systemic and topical antibiotic preparations, and the optimal methods of prevention.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jade Barker, Healthcare Science Associate, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Competing interests

None declared