After a drug's initial FDA approval, safety data can emerge from postmarket surveillance activities that may alter the risk-benefit ratio of a drug for some patients. The FDA issues Drug Safety Communications (DSCs) to disseminate this emerging safety information to health care professionals, patients, and the public to help enhance their decision-making.1 The DSC messages are also communicated through a variety of traditional and social media outletsReference Sinha, Freifeld, Brownstein, Donneyong, Rausch, Lappin, Zhou, Dal Pan, Pawar, Hwang, Avorn, Kesselheim, Woloshin, Schwartz, Dejene, Rausch, Dal Pan and Kesselheim2 and through other tactics. DSCs typically contain information that includes: (1) a summary announcement of the safety issue and the recommended actions for health care professionals and patients; (2) facts about the drug; (3) additional information for patients and caregivers; (4) additional information for health care providers; and (5) a summary of the data that were and/or are being reviewed by FDA. The FDA issued 261 DSCs between 2010 and 2018.3

DSCs impart what FDA considers essential information for health care providers, pharmacists, patients, and health systems. Yet limited data exist regarding the impact of the DSC messaging on the safe post-market use of pharmaceuticals, including where changes in drug prescribing and clinical utilization might be expected. Prior studies of drug safety announcements from regulatory bodies have shown effects on prescription pattern changes ranging from limitedReference Valiyeva, Herrmann, Rochon, Gill and Anderson4 to more extensive,Reference Wax, Doshi, Hossain, Bodian, Krol, Reich, Cohen, Rabbani and Shah5 perhaps related to the importance, severity, or extent of the risk(s) conveyed; or to the type of drug, how long it had been taken, or the disease or condition for which it was being used.

In a series of studies conducted after two DSCs focused on the widely-prescribed sleep medication zolpidem that imparted essential information about dangerous next-morning drowsiness and heightened risks for women, we found in claims data between January 2011 and December 2013 that low-dose zolpidem dispensing increased by 30% after the DSCs and high dosing declined by 13% among new users. However, the average initial dose did not change substantially in population-level analyses (from 9.7mg to 9.4mg, p<0.001), and these changes were not observed for eszopiclone prescriptions in the six months after the DSC was released.Reference Kesselheim, Donneyong, Dal Pan, Zhou, Avorn, Schneeweiss and Seeger6 To provide insight into the generalizability of factors identified through the qualitative studies that might affected these prescribing changes, we conducted a large cross-sectional patient survey. The primary aims of the survey were to assess patients' general awareness of the safety of their sleeping pill; their awareness of zolpidem and eszopiclone DSC messaging; and the sources from which patients obtain — and the manner in which they use — drug safety information generally.

To provide insight into the generalizability of factors identified through the qualitative studies that might affected these prescribing changes, we conducted a large cross-sectional patient survey. The primary aims of the survey were to assess patients' general awareness of the safety of their sleeping pill; their awareness of zolpidem and eszopiclone DSC messaging; and the sources from which patients obtain — and the manner in which they use — drug safety information generally.

Methods

Survey Background

To assess patient knowledge about drug safety information contained in DSCs, we chose to evaluate patient knowledge and understanding of two DSCs from 2013 relating to zolpidem (marketed as Ambien, Ambien CR, Edluar, and Zolpimist) and one in 2014 on eszopi-clone (Lunesta). The 2013 zolpidem DSCs announced lowering the recommended evening dose of zolpidem due to next-morning impairment of activities requiring alertness, especially in women, that could lead to dangerous accidents when driving, followed by label changes lowering the recommended doses for women in particular.7 A 2014 DSC announced similar information for eszopiclone, including warnings of next-morning impairment of next-day driving, memory, and coordination, and lack of awareness regarding such impairment.8 All DSCs recommended starting patients at lower doses, discussed that higher doses could increase the risk of next-day impairment, and suggested driving and other activities requiring mental alertness should be avoided the next day because the drug levels can remain high enough to impair them.

Population Data Source

Survey participants came from the Optum Research Database (ORD), a proprietary research database consisting of comprehensive, date-stamped administrative claims information for beneficiaries insured from a large health insurer in the US. ORD enrollment in 2013 included approximately 12.7 million members from insurance plans, large employers, federal and state governments, and public organizations. We obtained Institutional Review Board approval from Brigham and Women's Hospital, the New England IRB, and the FDA's Research Involving Human Subjects Committee.

Within the ORD, we sampled patients with at least two prescriptions for either zolpidem (N=1,000) or eszopiclone (N=1,000) during the qualifying period (July 1, 2012-June 30, 2013). We estimated that this sample would be sufficiently large to enroll a minimum of 400 respondents (200 per group), given an expected response rate of 20%, providing sufficient power to identify important differences across comparator groups. We used stratified random sampling to assure representation across patients aged under 40, 40 to 64, and 65 years or older, as well as across new initiators and patients who had been taking the drug before (non-initiators). Data extracted from the ORD included demographics, health utilization indicators in the qualifying period, the type of sleeping pill used, and sleep disorder diagnosis. We supplemented this information with survey questions on education, occupation, income, and reported health status (excellent, good, fair, poor).

Survey Development

The team developed a structured, self-administered survey. Using a Likert scale (always / almost always / occasionally / rarely / never), the first set of questions covered how often patients hear about drug safety information after starting a new drug, how often such information comes from health care providers or pharmacists, the format of such information (oral communication or written material), and how often patients seek updates. We asked similar questions about the sources from which patients receive drug safety information (health-related email list-serves, friends/family members, advertisements in traditional media, news reports, websites, and online message boards), as well as the utility of the drug safety information from each source (Likert scale: very / moderately / just a little / not at all).

The second set of questions specifically addressed zolpidem or eszopiclone (survey wording adapted as needed depending on which drug the respondent was prescribed; see Appendix for full questions for both surveys). After completing questions related to utilization and effectiveness, patients responded to nine True/False/Don't know statements describing zolpidem/eszopiclone drug safety information. Five described true statements in the drugs' DSCs, while four were false statements. For those who reported learning new drug safety information, we asked about the source of that information and described 10 potential behavioral responses, including seeking more information, looking for alternative insomnia treatments, changing the pill frequency/dose, or stopping the pill entirely (yes/no). Finally, we asked whether respondents recalled hearing drug safety information in which zolpidem and eszopiclone safety were specifically compared against each other (and if so, from what source).

The third set of questions inquired about preferred sources of drug safety information (health care provider, pharmacist, health-related list-serve, friend/family member, FDA website, any website, newspaper/magazine/TV, printed information attached to prescription, and other). We also asked respondents to pick a most- and least-preferred source from which to receive drug safety information.

Survey Administration

Participants received complete study packets in a personalized envelope with first class postage: a cover letter, the IRB-approved informed consent form, the self-administered paper survey/questionnaire, a $5 bill, and a postage-paid business reply envelope. The cover letter included a link that would allow participants to take an online version for those who preferred to respond electronically. Survey packets were re-mailed to all non-respondents two weeks and four weeks after the initial mailing. Participants were allowed approximately 10 weeks from the first mailing to complete the survey. Completed questionnaires (for which participants earned another $25 honorarium) were evaluated for duplicates from a single participant using subject identifiers: mail and online submissions from the same respondent (N=4) defaulted to the online response, and multiple completed paper questionnaires (N=48) defaulted to the most complete questionnaire. The study recruited participants from May through July 2015.

Data Analysis

Unique subject identifiers that could potentially link the self-administered questionnaire to patient-identifiable data from the ORD were removed before analysis. Paper surveys were entered into the database, and 10% of records were quality-checked. Data from every returned questionnaire with at least one question answered were used for the analysis. If any question was not answered, or the response could not be interpreted, the question was coded as missing. Descriptive analyses included counts, frequency, and 95% confidence intervals (CI), and comparative analyses were completed to identify differences across outcome strata.

We created a knowledge score variable based on the five fact questions that were true: (1) [Drug] can lead to drowsiness/impairment in driving the morning after the medication is taken; (2) [Drug] can lead to drowsiness/impairment in patients even if they feel fully awake; (3) Women should use a lower dose because they are more susceptible to side effects; (4) Side effects related to drowsiness/impairment the morning after taking [Drug] are more pronounced in women; and (5) All drugs taken for insomnia can interfere with driving and activities that require alertness the morning after use. Respondents scored a point for each question correctly answered as “True,” with 5 out of 5 being a perfect score. We used Wilcoxon tests to compare the knowledge score differences between demographic and respondent characteristics groups. Data were analyzed using SAS v. 9.4.

Results

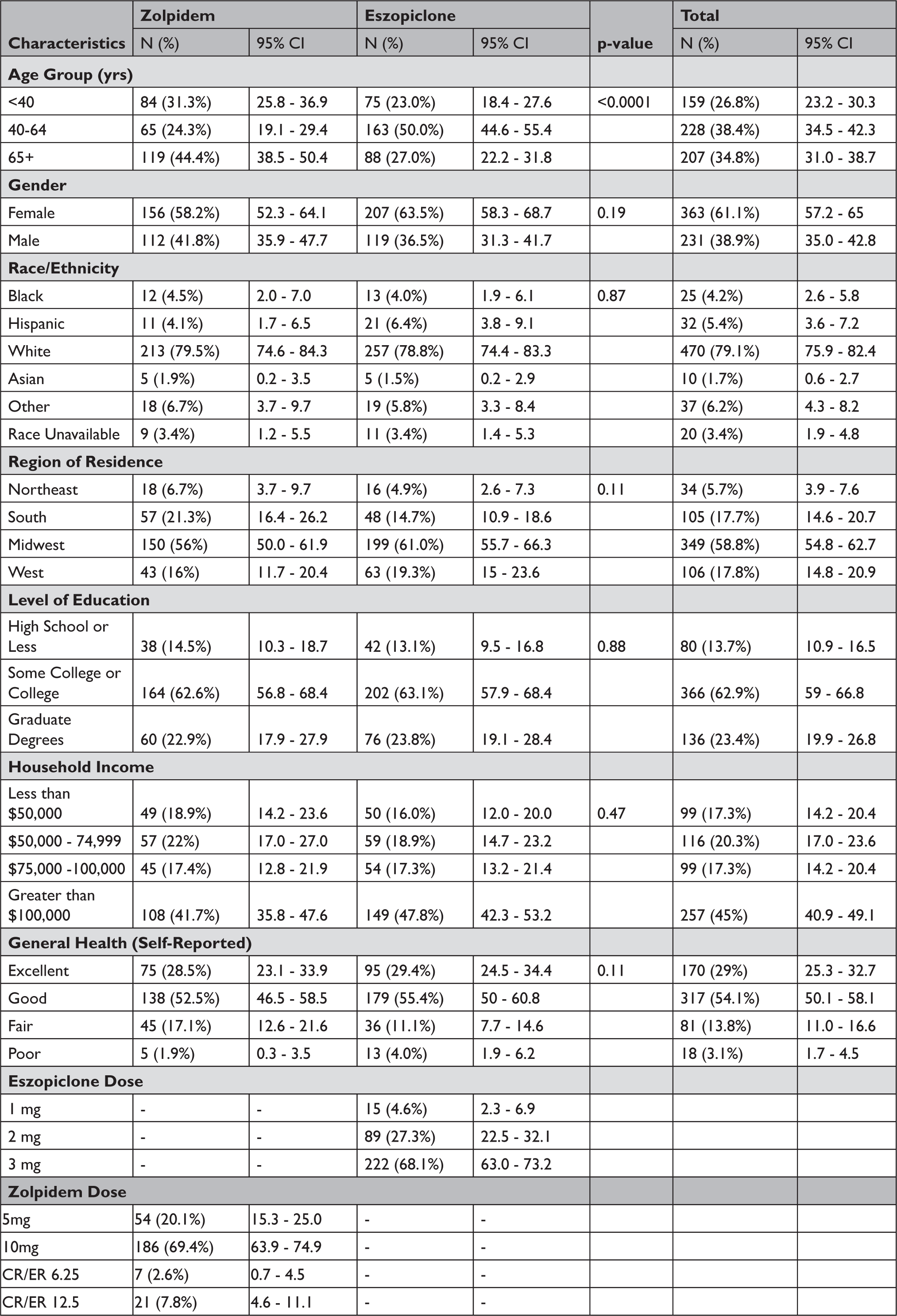

Of the 2,000 potential participants, 594 responded and 185 could not be reached, leading to a response rate of 32.7% (594/1815), with 29.6% (268/905) among zolpidem users and 35.8% (326/910) among eszopi-clone users. Other than age distribution, in which zolpidem users were much more likely to be 65 or older (p<0.0001), zolpidem and eszopiclone responders had similar baseline characteristics (Table 1); a non-responder analysis suggested minimal response bias (Appendix Table A1).

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of Survey Responders (Crude Responses, Total N=594)

Sources of Drug Safety Information

Two-thirds of respondents reported that they heard about drug safety after starting a new prescription at least occasionally (Table 2). The most common sources of drug safety information for patients were health care providers and pharmacists. Among the respondents who reported hearing updates to drug safety information, one-third (34%) said they either “always” or “almost always” receive the information from their pharmacists, while a quarter (24%) of respondents said that they either “always” or “almost always” receive this information from their providers. The majority of respondents receiving information from health care providers (61%) and pharmacists (65%) found the information “very useful” or “moderately useful.” As seen in Table 2, news reports (17.8%), advertisements (16.2%), and websites (12.1%) were less common sources of drug safety information. Respondents identified these secondary sources of drug safety information as less useful than information from health care providers and pharmacists. Of note, those that cited receiving drug safety information from a website were far more likely to utilize websites about health or drugs (73%) or search engines (18%) than government websites (2%).

Table 2 Sources of Drug Safety Information

Knowledge About Sleep Aid Drug Safety Information

Respondents' answers to the nine drug safety information questions varied greatly (Table 3). Among the five zolpidem and eszopiclone facts, close to half of respondents agreed that all insomnia drugs can cause morning drowsiness; 49.2% and 44.2% of zolpidem and eszopiclone respondents, respectively. Significantly more zolpidem respondents accurately identified the risk of morning impairment or drowsiness even if they feel fully awake (51.0% and 37.0% of zolpidem and eszopiclone respondents, respectively, p-value =0.004). Fewer than one in five correctly answered the questions assessing knowledge of women-specific side effects, with a broad majority of both zolpidem and eszopiclone patients choosing “don't know” for those two questions. Answers to the four false statements were much more consistent, with a majority of respondents answering “don't know” for all four.

Table 3 Knowledge of Key Drug Safety Information Facts for Zolpidem and Eszopiclone

* Answers to these questions were “true.” The median number of correct answers related to this question was 2 among zolpidem users (interquartile range [IQR]: 0-3) and 1 among eszopiclone users (p=0.05). Among the characteristics listed in Table 1, educational level was associated with having more correct answers (graduate degree median correct 2 [IQR: 0-3] vs. college [median 1, IQR 0-3] and high school or less [median 1, IQR 0-2]), p=0.005. Gender was also associated with a difference in median number of correct answers to these five questions, with men getting a median of 2 correct (IQR: 0-3) and women getting a median of 1 correct (IQR: 0-3) (p=0.004). See Appendix.

Distribution of knowledge scores, calculated out of the number of correct answers to true questions, was low overall, with a median of 2 correct out of 5. There were significant differences by education level, with more educational experience associated with answering more questions correctly, and by gender, with men answering more questions correctly despite some of the DSC information being related to side effects more likely to affect women. In addition, zolpidem respondents were more likely to have a higher score than eszopiclone respondents (Appendix Table A2).

Behaviors in Response to Drug Safety Information

Approximately two-thirds of zolpidem users and one-half of eszopiclone users reported hearing drug safety information about their respective prescription sleep aid, most commonly from health care providers, pharmacists, and printed information with prescriptions (Table 4). Among the actions favored by responders were seeking out more information about the safety of sleeping pill they are taking (75.1%), learning about alternative ways to help them sleep (72.1%), and asking their health provider about the safety of their sleeping pill (61.7%). There were no substantial differences between zolpidem and eszopiclone responders for those questions. In contrast, zolpidem users were more likely than eszopiclone users to respond that they would take the drug less often (55.7% vs. 36.2%, p-value =0.0006) or take a lower dose (58.0% vs. 30.3%, p-value <0.0001). Eszopiclone users were more likely than zolpidem users to respond that they would keep taking the medication as they had been (61.3% vs. 48.7%, p-value 0.03).

Table 4 Behaviors in Response to Learning Drug Safety Information

Preferred Sources for Drug Safety Information

The most preferred sources of drug safety information were health care providers (58.8%), pharmacists (37.2%), and printed information included with the prescription (32.7%). Among the least preferred sources were family/friends (42.0%), advertisements (29.6%), and websites (32.0%) (Table 5).

Table 5 Preferred Sources for Obtaining Drug Safety Information in the Future

Discussion

Through a national survey of patients using zolpidem and eszopiclone, we evaluated their sources of drug safety information and their knowledge of specific information affecting their prescription sleep aids that had been disseminated 12-28 months previously. We found that respondents generally relied on physicians and pharmacists to receive drug safety information and indicated that the information might lead them to investigate other treatment options or ask more questions about the risks and benefits of their medications. However, respondents overall demonstrated lack of accuracy/recall related to the key information contained in the drug safety information imparted in the zolpidem and eszopiclone DSCs.

This study offers several important lessons for informing patients about post-market safety information related to prescription drugs. First, a majority of patients reported occasionally, rarely, or never (68.9%) hearing about drug safety information after starting a new prescription drug. This suggests a need for broader dissemination of drug safety information to patients through all elements of the US healthcare system, including government, insurance and drug companies, and health organizations, and care providers and drug dispensers. Of the remaining 31.1% of respondents that reported always or almost always hearing about drug safety information prior to starting new prescription drugs, similar percentages obtained that information from health care providers (24.5%) or pharmacists (34.0%), respectively. However, substantial numbers of respondents reported that they rarely or never ask their health care providers (71.7%) or pharmacists (77.6%) about drug safety information. This reinforces the importance of communicating drug safety information to prescribers and pharmacists, who can relay that information pro-actively and directly to patients taking affected medications. In addition, health providers can consider this emerging safety information as they are making prescribing decisions. A minority of patients reported receiving drug safety information from online information sources; however, for those who do, this study results suggest it would be beneficial to make drug safety information more broadly available through traditional websites and via social media platforms.Reference Sinha, Freifeld, Brownstein, Donneyong, Rausch, Lappin, Zhou, Dal Pan, Pawar, Hwang, Avorn and Kesselheim9

The top three preferred sources of obtaining drug safety information were health care providers, pharmacists, and printed materials patients receive with their prescriptions. Unlike drug labeling, which is subject to FDA review, printed materials from pharmacies are often commercially developed and are not reviewed by the FDA or the drug's manufacturer prior to dissemination. This may be particularly relevant to patients who receive prescriptions by mail (about one in five respondents to our survey), since they may have limited or no interaction with a pharmacist. Our survey responses suggest that including prominent displays of new and emerging drug safety risks in printed materials may encourage patients to ask questions of their health care providers and pharmacists.

Patients generally could not correctly select answers relating to the DSC messaging for zolpidem and eszopiclone. For the zolpidem messaging, for which media analyses were conducted as part of a prior study, this may have been due to limited media coverage, particularly for the second zolpidem DSC, incomplete and inconsistent messaging from the lay media regarding DSC content or limitations on recall due to the survey's release 2+ years after the release of the information.Reference Woloshin, Schwartz, Dejene, Rausch, Dal Pan, Zhou and Kesselheim10 Lower performance on knowledge/recall-based questions also may point to the need to re-emphasize communication of key points through a variety of tactics, including on websites, social media, and through physician-patient or pharmacist-patient encounters. Finally, given that nearly 20% of respondents reported always or almost always receiving drug safety information from news reports, it is important that widespread and accurate coverage by news media of drug safety messaging is actively promoted.

Our survey's limitations could have contributed to the low levels of knowledge about key drug safety information facts. By including a “don't know” option choice, the robustness of comparisons between true and false answer choices was limited. In addition, recall of facts that may have been known at one time could have been affected by both the extent of time between the release of the information and the survey, and/or personal determinations when it was released that the information was not considered relevant to patients taking these medications, especially to those who had been taking them for some time. Also, the study sample was based on the identification of patients with dispensing claims for sleeping pills, and the characterization of a population based on data available in claims data. The presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not indicate that the medication was consumed or that it was taken as prescribed. Each of these factors could result in recall bias, making it difficult for respondents to correctly answer the knowledge questions.

Conclusion

The FDA issues DSCs and supporting information, such as podcasts, social media posts, email messages, and targeted outreach to media and healthcare professional and patient organizations to communicate new or emerging drug safety risks for prescription and over-the-counter drugs. These messages are intended for broad uptake by prescribers and patients alike. This survey — part of a comprehensive methodological approach of multi-modal studies conducted to gain insight into the impact of the DSC messaging and about drug safety information more broadly to identify opportunities for improvementReference Kesselheim, Campbell, Schneeweiss, Rausch, Lappin, Zhou, Seeger, Brownstein, Woloshin, Schwartz, Toomey, Dal Pan and Avorn11 — found that providers and pharmacists are trusted sources of drug safety information. That suggests that broader efforts may be needed to disseminate this information to health organizations, providers and pharmacists. In addition, strategies should be pursued to expand the reach of drug safety information through patient-preferred online sources such as search engines and health-related websites.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Judy Wong and Ms. Laura Karslake at Optum for coordinating the conduct of the survey.