Introduction

Dizziness is a common presenting complaint in the primary healthcare setting, with 15 out of every 1000 patients consulting their general practitioner every year on account of such symptoms as vertigo, dizziness or giddiness.Reference Jayarajan and Rajenderkumar1 The non-specific symptom of dizziness can have a multitude of aetiologies, including cardiovascular disorders, neurological disorders, haematological disorders, vestibular pathology, ophthalmic problems, and psychological and psychiatric disturbances.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2, Reference Drachman and Hart3

A subset of those patients suffering from dizziness experience true vertigo. This is an illusion or hallucination of movement, usually rotational, either of oneself or of the environment.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2 There are several diagnoses which can account for vertiginous symptoms. Key diagnoses include vestibular neuronitis, benign positional paroxysmal vertigo, Ménière's disease, migrainous vertigo and vertebrobasilar insufficiency.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2–Reference Hanley and O'Dowd4

Ménière's disease was first described in 1861 by Prosper Ménière.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2, Reference Saeed5 He initially noted a triad of fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus and episodic vertigo.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2, Reference Saeed5 To this is often added a sensation of fullness in the ear.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2 In 1938, the underlying pathology was found to be endolymphatic hydrops.Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2, Reference Saeed5, Reference Hallpike and Cairns6

Ménière's disease can be a difficult diagnosis to make in general practice. Patients whose dizziness has been attributed to Ménière's disease are often found to have other conditions accounting for their symptoms.Reference Drachman and Hart3 The UK National Health Service (NHS) ‘Prodigy’ guidelines have been produced to help healthcare professionals to diagnose and manage the disease.7

The aim of this audit was to consider how Ménière's disease is managed in general practice, and particularly to assess how well general practitioners adhere to the Prodigy guidelines.

Methods

We identified all general practices near the Torbay region of south Devon which had a ‘TQ’ postcode. There were 41 practices, staffed by a total of 203 general practitioners. We wrote to each individual general practitioner, asking them to complete a questionnaire on Ménière's disease. Our questionnaire was designed to reflect the information found within the Prodigy guidelines (see Appendix 1).

We initially received responses from 27 practices, which included replies from 83 general practitioners. Of these 83 replies, eight general practitioners stated their refusal to take part in the study. We subsequently telephoned the 14 practices which had not responded; this yielded a further four responses. Our practice response rate was 68 per cent. Our individual response rate was 43 per cent.

Results

Epidemiology

Seventy-seven per cent of the general practitioners gave a correct Ménière's disease prevalence of one in 1000 or one in 10 000. The majority of the remaining general practitioners (13 per cent) believed the prevalence to be one in 100. Respondents' answers regarding prevalence are shown in Table I.

Table I Responses to question ‘how common do you think ménière's is – give an estimate of its prevalence’

Most general practitioners (67 per cent) incorrectly believed that females were predominantly affected by Ménière's disease (Table II). Only 27 per cent of general practitioners thought that there was an equal sex distribution. Sixty-three per cent of respondents gave a correct age of onset, of 20–50 years (Table III).

Table II Responses to question ‘which sex is predominantly affected?’

Table III Responses to the question ‘what is the peak age of onset?’

Yrs = years

Diagnosis and treatment

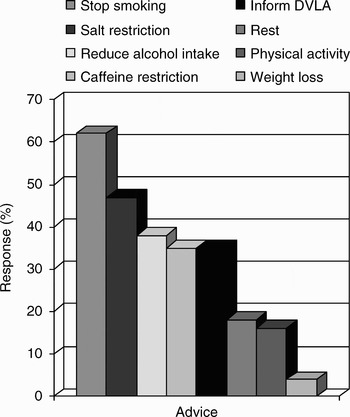

Regarding Ménière's disease diagnosis, 71 per cent of respondents correctly identified the triad of hearing loss, tinnitus and vertigo, with or without aural fullness (Table IV).

Table IV Responses to question ‘what are the essential features a patient must have in order to make a firm diagnosis of ménière's disease? please circle all you think apply’

Thirty-eight per cent of the general practitioners correctly believed that patients must have had two episodes of symptoms in order to make a diagnosis of Ménière's disease (Table V). Fifty-two per cent of general practitioners thought that symptoms lasted up to 24 hours, while 39 per cent believed that symptoms went on for days (Table VI).

Table V Responses to question ‘how many attacks does a patient need before a diagnosis can be made?’

Table VI Responses to question ‘how long do symptoms last?’

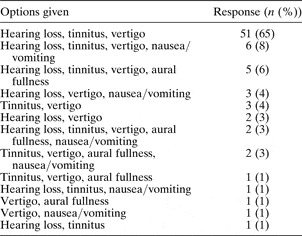

Regarding treatment of an acute attack, 90 per cent of respondents reported using prochlorperazine. More than 50 per cent also reported using cyclizine or betahistine (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Responses to the question ‘what do you use for management of an acute attack?’

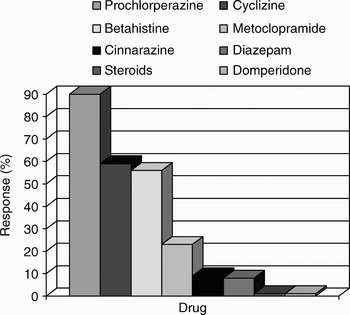

For Ménière's disease prophylaxis, 91 per cent of general practitioners reported using betahistine (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 Responses to the question ‘what drugs do you use for prophylaxis?’

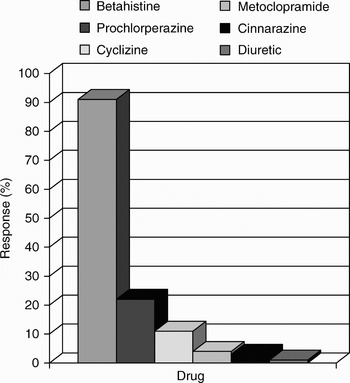

Reponses varied regarding additional advice that might be given to a patient with Ménière's disease. The most common suggestion was to stop smoking (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Responses to the question ‘what additional advice might you give a patient with Ménière's disease?’ DVLA = Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority

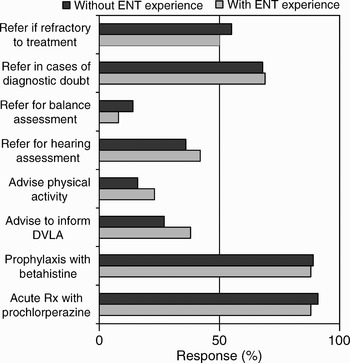

The decision of when to refer to an ENT surgeon was motivated by a variety of factors (Figure 4), the most frequent being diagnostic doubt.

Fig. 4 Responses to the question ‘when would you refer to an ENT surgeon?’

Use of guidelines

Sixty-three per cent of respondents were unaware of any guidelines regarding Ménière's disease (Table VII). Those general practitioners who did refer to guidelines within their practice used The GP Notebook and the American Academy of Otolaryngology guidelines.8 One respondent stated that the guideline they were aware of was to ‘refer all suspected cases’; another respondent stated that guidelines did exist but was unsure what they were. Not one general practitioner mentioned the Prodigy guidelines.

Table VII Responses to question ‘are you aware of any guidelines regarding ménière's disease? if so, what?’

AAO = American Academy of Otolaryngology; GP = general practitioner

ENT experience

Most general practitioners had not spent any time working in an ENT department (56 per cent). Thirty-two per cent had done so. Experience varied, from three months as a pre registration house officer (PRHO) or senior house officer, to working as a clinical assistant or having a specialist interest in ENT within general practice. The remaining respondents did not specify whether they had ENT experience or not. General practitioners with ENT experience had an average of 51 per cent correct answers for questions regarding the prevalence and diagnosis of Ménière's disease, while those without ENT experience scored 56 per cent. The remaining answers are illustrated in Figure 5.

Fig. 5 Responses to questions according to general practitioner's ENT experience'.

Discussion

In 1999, the Prodigy guidelines for Ménière's disease were produced by the NHS National Library for Health. They are summarised in Appendix 2.

Our audit was carried out with the aim of assessing how well Torbay general practitioners adhered to these guidelines.

Our results show that the majority of these general practitioners knew the correct prevalence and age of onset of the disease. However, there was a misconception that females are predominantly affected. This could lead to overdiagnosis of the disease in women.

Whilst the general practitioners had a good knowledge of the symptoms required to make a diagnosis of Ménière's disease, there was some confusion as to how many episodes a patient required in order to fulfil the diagnostic criteria.

Management of Ménière's disease in the primary healthcare setting appeared to be appropriate, with most general practitioners reporting use of prochlorperazine for an acute attack and betahistine for prophylaxis. Regarding additional advice to patients, only a minority of respondents suggested pursuing physical activities. A substantial proportion of respondents recommended that the patient inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority. However, there was a definite trend in advising lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, alcohol restriction and caffeine restriction. Whilst there is no evidence that these play a role in the management of Ménière's disease, they are invaluable recommendations for the overall health and well-being of the patient.

• Dizziness is a common presenting complaint in general practice

• One of the differential diagnoses is Ménière's disease. This can be a difficult diagnosis to make

• The UK National Health Service ‘Prodigy’ guidelines have been produced to help primary healthcare workers in the diagnosis and management of Ménière's disease

• This audit assessed how well general practitioners in South Devon adhered to the Prodigy guidelines

• The average score on a postal questionnaire was >50 per cent

• Diagnosis and management of Ménière's disease in the primary healthcare setting might be improved by further education

The mean rate of correct answers scored by the general practitioners was >50 per cent. They achieved this despite few being aware of any formal guidelines. It is interesting to note that none of the general practitioners knew of the Prodigy guidelines. We appreciate that there are other sources of information, such as the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium Ménière's disease guidelines;8 in addition, general practitioners often attend training days, which may deal with Ménière's disease.

This audit has allowed us to summarise the knowledge of Ménière's disease amongst a community of general practitioners in south Devon. However, our practice response rate of 68 per cent and individual response rate of 43 per cent raise the possibility of responder bias. It is usually argued that those who are confident in their knowledge may be more likely to respond than those who are not.

Appendix 1. Ménière's disease – please circle the answer you think is correct

How common do you think Ménière's disease is? Give an estimate of its prevalence:

1/10 1/100 1/1000 1/10 000 1/100 000

Which sex is predominantly affected?

Males Females Both

What is the peak age of onset?

<20 yrs 20–50 yrs 50–80 yrs >80 yrs

What are the essential features a patient must have to make a firm diagnosis of Ménière's disease? Please circle all you think apply:

Hearing loss Nausea/vomiting Tinnitis

Headache Vertigo

Loss of consciousness Sensation of fullness in the ear

Other – please specify

How many attacks does a patient need before a diagnosis can be made?

1 2 3 4 5 >5

How long do symptoms last?

Seconds <5 minutes 5–20 minutes Up to 24 hours Days

Which drugs may be useful in an acute attack? Please circle all that apply:

Prochlorperazine Cyclizine Diazepam Lithium Betahistine Metoclopramide Other–please specify

Which drugs may be useful for prophylaxis?

Prochlorperazine Cyclizine Diazepam Lithium Betahistine Metoclopramide Other–please specify

What additional advice might you give a patient with Ménière's disease?

Rest Salt restriction Weight loss Inform DVLA Stop smoking Reduce alcohol intake Pursue physical activities Caffeine restriction Other – please specify

When would you refer to an ENT surgeon?

All patients Patients refractory to medical treatment For hearing assessment Diagnostic doubt Patient request More than 10 attacks For balance assessment

Are you aware of any guidelines regarding Ménière's disease? If so, what?

Have you spent any time working in an ENT department, for example, as an SHO? If so, please specify what, and for how long:

Thank you!

Appendix 2. Summary of Prodigy guidelines

– Guidelines produced to allow healthcare professionals to make evidence-based decisions regarding the management of their patients

– Goals of the guidelines are:7

– To stop or reduce the symptoms during attacks of vertigo

– To reduce the frequency and severity of attacks

– To optimise hearing and to control tinnitus

– To maximise quality of life and ability to cope with residual symptoms

According to the guidelines:

– Prevalence of Ménière's in the UK is between 1 in 1000 to 1 in 20 000

– Men and women are equally affected

– Peak age of onset is between 20 and 50 years of age

– Firm diagnosis of Ménière's disease requires all three of the following criteria:

– At least two spontaneous episodes of vertigo lasting at least 20 minutes

– Sensorineural hearing loss confirmed by audiometry

– Tinnitus and/or perception of aural fullness

– Drugs useful in acute attacks of vertigo include prochlorperazine and cinnarazine

– For prophylaxis, betahistine is commonly used, although there is insufficient evidence to assess its effectiveness. Similarly, diuretics, alone or in combination with salt restriction, are often recommended, but again data is inconclusive. The guidelines note that as different people respond variably to different treatments, a number of therapies may have to be tried until one that suits the patient is found.

– After an acute attack, patients should be encouraged to mobilise to promote central compensation

– Drivers with Ménière's disease must inform the DVLA

– Patients should be cautious of activities such as using ladders

– There is no evidence that salt, caffeine, nicotine or alcohol restriction will help the disease

– Certain patients should be referred to an ENT specialist for further assessment and investigation:

– Those in whom there is diagnostic doubt

– Those whose vertigo is refractory to medical treatment

– For hearing, tinnitus or balance assessment, when necessary