Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 May 2005

Objective: The standards of care for patients at risk for or with a pressure ulcer in hospitals and nursing homes focus on prevention and ulcer healing using an interdisciplinary approach. Although not a primary hospice condition, pressure ulcers are not uncommon in dying patients. Their management in hospices, particularly the involvement of family caregivers, has not been studied. The objective of this study is to identify the factors that influence care planning for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in hospice patients and develop a taxonomy to use for further study.

Methods: A telephone survey was conducted with 18 hospice directors of clinical services and 10 direct-care nurses. Descriptive qualitative data analysis using grounded theory was utilized.

Results: The following three themes were identified: (1) the primary role of the hospice nurse is an educator rather than a wound care provider; (2) hospice providers perceive the barriers and burdens of family caregiver involvement in pressure ulcer care to be bodily location of the pressure ulcer, unpleasant wound characteristics, fear of causing pain, guilt, and having to acknowledge the dying process when a new pressure ulcer develops; and (3) the “team effect” describes the collaboration between family caregivers and the health care providers to establish individualized achievable goals of care ranging from pressure ulcer prevention to acceptance of a pressure ulcer and symptom palliation.

Significance of results: Pressure ulcer care planning is a model of collaborative decision making between family caregivers and hospice providers for a condition that occurs as a secondary condition in hospice. A pressure ulcer places significant burdens on family caregivers distinct from common end-of-life symptoms whose treatment is directed at the patient. Because the goals of pressure ulcer care appear to be individualized for a dying patient and their caregivers, the basis of quality-of-care evaluations should be the process of care rather than the outcome of an incident pressure ulcer.

Pressure ulcers are not uncommon (Hanson et al., 1994; Bale et al., 1995; Leff et al., 2000) in dying patients because of acquired risk factors of immobility, functional incontinence, and compromised nutrition (Hanson et al., 1991, 1994; Bale et al., 1995; Walding & Andrews, 1995; Chaplin, 2000). However, their management, especially the unpleasant aspects of care (Dallam et al., 1995; Szor & Bourguignon, 1999; Kayser-Jones et al., 2003), has received little attention from palliative care researchers. Consistent with the traditional standards of pressure ulcer care, most of the relevant studies are studies of the effectiveness of nursing prevention programs in single hospices (Hanson et al., 1991, 1994; Bale et al., 1995; Walding & Andrews, 1995; Chaplin, 2000) or factors affecting the incidence of pressure ulcers at the end of life in long-term care (Kayser-Jones et al., 2003).

In all settings, the management of a patient with a pressure ulcer requires an interdisciplinary approach (Baranoski et al., 1998; van Rijswijk & Braden, 1999), and in the home environment, care is highly reliant on family caregivers. The burdens in general experienced by families caring for patients with terminal illness at home have been explored (Covinsky et al., 1994; Emanuel et al., 2000). Similarly, both the burdens (Baharestani, 1994) and positive contributions (Clarke & Kadhom, 1988) of families providing pressure ulcer care at home for chronically ill patients have been described. We report a qualitative description of the factors contributing to pressure ulcer care planning for hospice patients, which was collected as part of a broad explorative study of pressure ulcers in hospice (Eisenberger & Zeleznik, 2003).

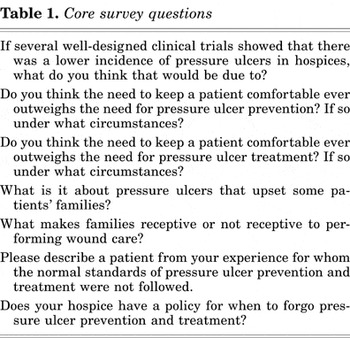

We developed a telephone survey instrument consisting of questions based on a Medline and bibliographic review of the medical and nursing literature using combinations of the search terms “hospice,” “palliative care,” “pressure ulcer,” and “decubitus ulcer.” The instrument was reviewed for face validity and pilot-tested on two physicians and five nurses with experience in wound care and end-of-life care, and a family member of a patient who died with a pressure ulcer. The format and language were revised in consultation with an educational researcher. Three versions were produced for interviews with directors of clinical services, direct-care nurses, and family members. The versions had approximately three-quarters overlap in content in order to explore different perspectives on the same clinical issue. The question formats were open-ended and dichotomous response. The core survey questions are shown in Table 1. The study was approved by the Montefiore Medical Center institutional review board.

Core survey questions

A pool of hospices was purposely selected from the American Hospice Foundation's Web site (American Hospice Foundation, 2004) to represent various geographical regions of the United States. A letter of introduction was sent to notify the director of clinical services of our intention to perform a phone interview. After verbal consent, a single investigator conducted semi-structured telephone interviews as prearranged with each participant. At the end of the interview, the director of clinical services was asked to provide the name of a nurse at their institution as well as a family member of a hospice patient who had experienced a pressure ulcer. Despite previous participation of the families of terminally ill patients in focus groups and surveys (Emanuel et al., 2000; Steinhauser et al., 2000), none of the hospices agreed to allow us to interview family members of their patients. Responses were entered verbatim as text into a Microsoft Access Database. Interviews were continued until no new thematic concepts were obtained.

Twenty-seven of 28 hospices contacted agreed to an interview. Saturation was reached after 28 individuals from 17 hospices were interviewed. The participants were 18 directors of clinical services, of whom 9 were physicians and 9 were nurses, and 10 direct-care nurses. The characteristics of the hospices are shown in Table 2. The direct-care nurses had a mean of 4 and 18 years of hospice and total nursing experience, respectively. Six of the direct-care nurses worked with outpatients, three with inpatients, and one with both. None had advanced practice training in wound care.

Characteristics of the survey participants

Data were analyzed using an approach based on grounded theory (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). While the interviews were still being conducted two investigators independently used a process of open-coding to iterate broad themes by marking key phrases, sentences, or terms on printouts of the responses. This led to the choice of hospice team–family caregiver as the unit of analysis. After saturation had been reached, axial coding was done by a negotiated group process on the entire data set. Credibility was sought by presentation to an interdisciplinary group of health care providers at a hospital that specializes in the care of advanced cancer patients and the analysis was subsequently revised. The illustrative quotes have been edited for ease of reading without making substantive changes.

Three broad themes related to pressure ulcer care planning were identified (Table 3). The hospice nurse is an educator rather than a wound care provider. Family caregivers are perceived to have barriers and burdens related to participating in pressure ulcer care. Family caregivers collaborate with hospice providers to establish individualized achievable goals of care for the hospice patient. Although we collected data on institutional policy and risk screening for pressure ulcers, the participants did not emphasize this as significant to care planning; consequently these data are presented separate from the qualitative analysis.

Factors related to pressure ulcer care planning in hospice

Four of 18 hospice directors of clinical services were definitively able to state which standardized pressure ulcer risk assessment instrument they used. These were one each of the Braden scale (Bergstrom et al., 1987), a “modified” Braden scale, a “4-point scale,” and an “in-house tool.” Four hospice directors of clinical services stated that their hospice used no formal risk assessment scale, two said that the patient's “mobility” was assessed, and seven did not know if they used a risk assessment scale. Five direct-care nurses did not know what risk assessment scale they used, three said that they used none, and two performed assessments without an instrument. Only one hospice collected data on pressure ulcer incidence and prevalence.

There was significant variation in the use of specialty beds and mattresses. Indications for use were related to the ulcer, the patient, or the caregiver. The circumstances related to the ulcer ranged from “once the skin turns red” to “a severe ulcer and [a patient with] an unclear prognosis.” Bed utilization could also be motivated by the “frequency of pressure ulcer occurrence and rapidity of pressure ulcer advancement.” Patient considerations were “once the patient can't move themselves,” or when “the patient is at high risk and usual prevention would be very uncomfortable.” Caregivers having “difficulty [with] turning” was also cited as an appropriate indication. Certain specialty beds were thought to add to patient's social isolation because of “noise,” the patient being unable to “see and get out of it,” or a sense of “people getting sunk.” The actual decision to use a specialty bed was usually at the discretion of the primary nurse, but could also be a “joint decision” involving family caregiver preferences.

The direct-care nurse was universally identified as an educator rather than as wound care provider. These nurses “do lots of hands-on teaching,” and “preventative teaching.” The only two nurses who did not teach family caregivers to provide pressure ulcer related care worked solely at an inpatient hospice. Educational content included instruction about risk factors, turning and positioning, and topical dressing changes by the “see one, do one approach.” It was felt that families initially have a poor understanding of the causes of pressure ulcers, and education was considered important to reduce the psychological impact of pressure ulcers on patients and their families. The occurrence of a new pressure ulcer was considered a “teachable moment,” which included emphasizing that “it's not the family's fault.”

The factors cited as promoting a family's willingness to perform wound care were the educational impact and the availability of the nurse. Other promoting factors were pressure ulcer location, for instance, “feet are easier than ischium,” caregiver characteristics of “commitment,” “education level,” and “[possessing] a feeling of control when life is out of control.” In addition wound care performed by family caregivers obligates the hospice team to provide a care plan that addresses unpleasant aspects of the ulcer. Characteristics involving “sight and smell” such as “odor,” “disfigurement,” “ooze,” and “blood” were cited as limiting a family's willingness to perform dressing changes. There were felt to be limits to how much a family could participate in pressure ulcer care. These were best described by a direct-care nurse who stated that there are circumstances when “the level of pain and emotional difficulties for the family outweigh pressure ulcer management.” Another nurse remarked that “the family may refuse management because of discomfort and the knowledge that death is imminent.” Other limiting factors were gender and cultural barriers, “fear of incompetence,” and fear of causing pain, expressed as “it's scary to help someone you love.”

Incident pressure ulcers were considered burdensome to families because of the “awful connotation reflecting neglect and wasting.” The family caregivers were reported to experience “guilt” that they are “not doing a good job” or that “they [had] failed.” Pressure ulcers could also “pull the family out of denial regarding the dying process” or “serve as a reality check that the patient is failing.” The development of a progressive or advanced stage pressure ulcer was also viewed as a “care crisis” that could force admission into inpatient hospice.

For pressure ulcer prevention, care provided by well-educated families was the most frequent reason given for a theoretical lower incidence of pressure ulcers in hospice patients compared with patients dying in other settings. Pressure ulcers complicate end-of-life care because “they are a family issue.” No participant could describe a formal protocol for deciding when to forgo preventive and healing efforts in favor of comfort; rather they relied on the “clinical judgment” of health care providers and considered family preferences and abilities. One director called this the “team effect.” This process was individualized, discussed at a “team meeting,” “deferred to the patient and family,” or occurred when “the family doesn't want to cause more suffering.” In this situation hospice health care workers “need to be flexible.” Similarly, it was also said that, “The family and patient must be in charge. If the patient wants to stay at home and the family can't turn them, it's better for them to stay at home and get a pressure ulcer.” Respondents suggested that at this point it is appropriate to “focus on symptoms” of pressure ulcers, rather than curative management. A shift away from care related to the prevention of pressure ulcers or goals of healing was also made when the hospice provider's clinical judgment indicated that “death is imminent.”

These findings suggest a taxonomy of factors related to pressure ulcer care planning in hospice that can be used for in-depth, structured surveys of pressures ulcers at the end of life. We have identified the scope of the hospice nurses' role as well as the barriers and burdens for family caregivers' participation in press ulcer care. Care planning for pressure ulcers, a condition that may occur secondarily to the hospice diagnosis, is a model of collaborative decision making between family caregivers. This collaboration, the “team effect,” leads to individualized goals for pressure ulcer care in hospice patients. In contrast institutional pressure ulcer policies and procedures were not significantly reported to contribute to the care plan.

The role of the hospice nurse for pressure ulcers is as an educator rather than wound care provider. This role includes teaching preventive strategies, wound care, addressing the prognostic significance of a pressure ulcer, and perceived feelings of guilt, failure or neglect on the part of family caregivers. Many of these issues have been explicitly mentioned in published care standards and guidelines (Hoffman et al., 1991; Hanson et al., 1994; Chaplin, 2000). Clearly, in hospice, teaching on the topic of pressure ulcers must by necessity compete with topics such as proper use of analgesics, dietary modifications, and review of advance directives. The relative amounts of time spent by hospice nurses on education about the primary illness and secondary conditions in hospice patients may warrant further study.

Family caregivers were reported to have a range of involvement in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Well-educated family caregivers were the most frequently cited reason for a perceived lower incidence of pressure ulcers in hospice patients. This reported observation supports the view that care-related factors are at least as important as patient-related factors for prevention (Clarke & Kadhom, 1988; Kayser-Jones et al., 2003). Unlike the occurrence of symptoms of pain or dyspnea, which are attributable to the disease process at the end of life, our participants reported that families could attribute the occurrence of a pressure ulcer to failure of their care and this can be a source of additional burden. With the exception of active hemorrhaging or fungating cancers, the burden of a specific sign or symptom is usually borne by the patient at the end of life. In addition to pressure ulcers, there may be other conditions such as terminal delirium for which the care plan appropriately concentrates as much education for the caregiver as it does treatment of the patient.

The “team effect” describes family caregivers as part of the health care team rather than surrogates of the patient or a component of the “patient–family caregiver unit” (Raudonis & Kirschling, 1996; Brandt, 2001) who simply receive care from the health care professionals. This term expresses that the family caregiver has joined the interdisciplinary team not only for delivery of care related to prevention and wound care, but also to express their own needs and to establish individualized goals of care. Although the participation of family members on the team was explicitly perceived to contribute to a lower incidence of pressure ulcers in home hospice patients, the goals of care could include acceptance of a new pressure ulcer at the end of life in some circumstances. The team effect reported here may be the converse of hospice nurses becoming part of the family (Raudonis & Kirschling, 1996). The description of the team effect confirms implicit suggestions for health care professionals to establish a partnership with families in order to meet mutual goals (Hoffman et al., 1991; Hanson et al., 1994; Levine & Zuckerman, 1999; Tuch, 2003), for patients with pressure ulcers (Maklebust & Magnan, 1992; Remsburg & Bennett, 1997; Bennett et al., 2000; Decanay, 2000), or that hospice nurses should “relinquish varying amounts of control to family members and to include them as equal members on the home care team” (Sergi-Swinehart, 1985 pp. 465).

The use of standardized pressure ulcer risk screening instruments among participating hospices was low and not identified as significant for determining the pressure ulcer care plan. This indicates an area for improvement (Hoffman et al., 1991; Wright, 2001). Risk screening instruments designed for use in hospitals, nursing homes, and individual hospices (Bale et al., 1995; Walding & Andrews, 1995) have been shown to effectively reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers, which are accepted as a source of pain (Dallam et al., 1995; Szor & Bourguignon, 1999). A validated strategy for prevention should be considered even at the end of life (Chaplin, 2000). One published standard of care for pressure ulcers in hospice patients begins with a systematic risk assessment, but then individualizes achievable prevention and healing goals (Hoffman et al., 1991). Our data suggest that the latter, but not the former, may already be occurring in current practice. Finally, it is important to note that even if all pressure ulcers are not preventable, malpractice cases for alleged injuries from pressure ulcers in other care settings have been on the basis of pain and death (Bennett et al., 2000).

Our study has several limitations. Participants were exclusively in U.S. hospices and they may not represent the experiences and practices in hospices in other parts of the world. Our findings regarding the use of pressure ulcer screening instruments and specialty beds are only suggestive and must be confirmed by formal survey of a larger random sample of hospices. Most significantly, we are lacking a direct report from family caregivers, which limits accuracy, but our findings are consistent with previous direct reports of the effects of a pressure ulcer on patients and their families (Baharestani, 1994; Langemo et al., 2000). Our inability to interview family members is a reminder that collaboration between hospices and researchers limits progress toward a scientific basis for improving patient care at the end of life (Sachs, 2003).

Although our survey was conducted with nurses and physicians practicing in hospices, it has quality-of-life and quality-assurance implications for pressure ulcer care in terminally ill patients and their families in hospitals, nursing homes, and home care (Keay et al., 1994; Hayley et al., 1996; Fried et al., 1999; Baer & Hanson, 2000; Emanuel et al., 2000; Ferrell et al., 2000; Leff et al., 2000; von Gunten et al., 2002; Kayser-Jones et al., 2003; Pillemer et al., 2003). The tracking of pressure ulcer incidence rates and initiation of preventive care plans based on established guidelines (Bergstrom et al., 1992) is the standard of care in all hospitals and nursing homes (Moody et al., 1988; Bergstrom et al., 1994; Bennett et al., 2000) with the goal of absolute prevention regardless of the overall goals of patient care. In contrast, some experts have hypothesized that not all pressure ulcers are preventable (Hanson et al., 1994; Bennett et al., 2000). Our data suggest that a single standard for pressure ulcer prevention is not appropriate in all populations, or even in all hospice patients. Contained in practice guidelines (Bergstrom et al., 1994, p. 26) and expert recommendations are statements that comfort goals may be more appropriate than goals of absolute prevention or healing (Clarke & Kadhom, 1988; Moss & La Puma, 1991; Walding & Andrews, 1995; Regnard & Tempest, 1998; Waller & Caroline, 2000). Our results do support that quality of care evaluation should be based on the process of care for the individual dying patients and their caregivers rather than solely on the outcome of an incident of pressure ulcer.

The authors thank Penny Grossman, Ed.D., Linda Dallam, R.N., G.N.P., Catherine Badillo, R.N., G.N.P., Cathy Kalinski, R.N., Mary Schnepf, R.N., and James Cimino, M.D. for assistance with survey instrument development. The authors also thank the participants who shared their clinical experiences with us. Dr. Zeleznik is supported by a Geriatric Academic Career Award, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, K01-HP00001.

Core survey questions

Characteristics of the survey participants

Factors related to pressure ulcer care planning in hospice