INTRODUCTION

The sixteenth-century Mexican manuscript known as Matrícula de Tributos, or Codex Moctezuma, is composed of a collection of 31 richly painted sheets of native paper (amatl), which depict the tribute that the different provinces of the Anahuac paid to Tenochtitlan at the time of Cortés's arrival. Based on the visual inspection of the original manuscript performed in the National Museum of Anthropology and History of Mexico, this article asks questions that engage with scholarly consensus and received knowledge which holds that the Matrícula is a pre-Conquest manuscript in its entirety. I first ask whether the diverse styles identifiable throughout the manuscript may challenge the traditional dating of it to the eve of the Spanish invasion, as a number of folios from the manuscript appear to incorporate material that could come from related documents made at a later date during the colonial period. A comparison with pre-Hispanic and colonial documents would suggest that, while some folios may date to the late pre-Hispanic period, others may be from as late as the 1560s. In order to assess the different styles identifiable throughout the Matrícula de Tributos, I have focused on its more than 300 toponyms, considering them vis-à-vis the traditional practices and conventions of tlacuilolli, as they may be identified in late pre-Hispanic manuscripts, such as the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, and colonial sources such as the Codex Borbonicus and the Beinecke Map. With the purpose of providing a wider discussion about said practices, I compare the iconographic style of the Matrícula with that of its closest cognate manuscript, the Codex Mendoza.

A second area of focus looks closely at the fragmentary state of the manuscript and asks questions about its conservation and repair. Were the pages of the Matrícula repaired time and again during its early history, because of the wear and tear of a frequently used document, by reattaching pieces of amatl paper that came lose? Or, as it would appear to the naked eye on some pages, by recycling fragments from other versions of the manuscript? If so, considering the Matrícula together with the second section of the Codex Mendoza, it is worth asking whether the Matrícula, as a whole, might be the last extant exemplar of a larger group of taxation-related documents that circulated throughout Mexico on the eve of the Spanish invasion and well into the second half of the sixteenth century. Material and stylistic questions about the Matrícula will benefit from further scientific analysis of the manuscript that may enrich the work of the historian, as has been the case for many other manuscripts in recent years.

As the Spanish dominion of Mexico consolidated itself during the first and second viceroyalties, roughly from 1535 to 1560, economic, genealogical, and political documents were produced and circulated widely throughout the viceroyalty. Some were made to mediate the relationship between natives who were commoners and surviving elite with their Spanish overlords. Some focused on individual claims of landownership or on the right to rule. Yet others, as recent work on the Codex Mendoza has shown, focused on larger questions, such as the right to self-rule for the peoples of the New World, as furthered by Las Casas and his followers (Gomez Tejada Reference Gómez Tejada, Jansen, Lladó-Buisán and Snijders2019). I conclude by asking whether the context in which the Matrícula was kept and repaired is that of documents that registered or presented a record of pre-Conquest tributary practices, both as instruments that recorded past tributary obligations and as a means to assert authority and other political claims within the surviving native elite (Brittenham Reference Brittenham and Tejada2020; Consejo de Indias 1923; Mundy Reference Mundy and Tejada2020).

THE MATRÍCULA DE TRIBUTOS IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The Matricula de Tributos is one of the most important and, at the same time, most problematic manuscripts from sixteenth-century Mexico. Its early history is anything but clear: while the manuscript may have been kept and circulated within the surviving Nahua elite during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, we know very little of its origin and circulation. Prestigious Mexica families, like those of Tezozomoc and Ixtlilxochitl, kept collections of documents that traced their lineages and provided evidence of their land properties, their economic benefits, and their political prerogatives. However, even provincial families kept and commissioned documents that would prove their reputable origins and history, as was the case of the Castañeda family from Cuauhtinchan, who commissioned the document that we know as the Historia Tolteca Chichimeca, in order to justify their privileges within their community. It would not be inconceivable to think about the Matrícula de Tributos within the context of similar collections held by members of the surviving native elite. Likewise, it is not beyond the realms of possibility that more than one copy of the same document may have been kept by different branches of the same family or familial group.

However, the Matrícula's first appearance in written history dates to the eighteenth century, within Lorenzo Boturini's much discussed collection of Mexican documents. These papers were confiscated by colonial authorities in 1749, and kept at the Secretaría de Cámara of the Viceroyalty for years, where several scholars, including Mariano Fernández de Echeverría y Veytía, Antonio de León y Gama, and Archbishop Lorenzana might have consulted them for the benefit of their own works (Moreno Reference Moreno1971). During the period between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, pages from the Matrícula were reproduced and consulted on several occasions. During this time, two of its folios were sent to the United States, only to be returned in the 1940s as part of President Roosevelt's good neighbor policy (Hamann Reference Hamann2018). The first modern studies of the Matrícula date from this period.

Barlow (Reference Barlow1949:4–5) suggested that, based on the Matrícula's European format, the manuscript must have been painted anew for conquistador Hernán Cortés to inform him of the economic structure of the Mexica realm, and then, decades later, Viceroy Mendoza, the alleged patron of the manuscript that bears his name, had it copied to show Charles V what New Spain was like before the arrival of the Spanish. Robertson (Reference Robertson1959) and Gibson (Reference Gibson, Ekholm and Bernal1971) subsequently agreed with this direct relationship between the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza. By contrast, Borah and Cook (Reference Borah and Cook1963) suggested that both the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza had been copied from a now lost indigenous prototype, which they dubbed “Prototype A.” Berdan (Reference Berdan1980:2–4) offered a third hypothesis. She suggested that the Matrícula is a pre-Hispanic document, with signs of post-Conquest influence only to be found in the insertion of Spanish glosses. She proposed that the Matrícula's connection with the Codex Mendoza was to be found in oral tradition—as there were visible differences between both manuscripts that argued against a direct connection. Batalla Rosado (Reference Batalla Rosado2007), accepting the received knowledge of the Matrícula's pre-Conquest origin, used it to argue for a direct connection with the Codex Mendoza, and proposed that the same master painter who painted a number of folios of the Matrícula also painted the Mendoza.

Throughout the history of the Matrícula, the manuscript has been approached as a historical or anthropological document that may cast light onto pre-Hispanic tributary and political practices. With this essay I seek to ask some initial questions which, focusing on the making, repairing, and conservation process of the manuscript, may enrich the wider discussion about the agency of Nahua painters during the early colonial period, as explored by Bleichmar (Reference Bleichmar2015) in her work on the Codex Mendoza, and the political agenda that these manuscripts may reveal through their narrative priorities and stylistic decisions (Gómez Tejada Reference Gómez Tejada, Jansen, Lladó-Buisán and Snijders2019; Mundy Reference Mundy and Tejada2020). Further scientific work on the manuscript will offer verifiable, concrete information about its materiality and making process that may enrich a discussion about the different levels of symbolic representation within its pages, as Magaloni (Reference Magaloni2004) has shown for the Florentine Codex (Domenici Reference Domenici and Tejada2020).

COLONIAL AND PRE-HISPANIC STYLES OF THE MATRÍCULA DE TRIBUTOS

The Matrícula de Tributos shows outstanding examples of late pre-Hispanic artistic conventions, when artists prized stylization and formal conventionalization, regardless of the nature of the subject, as well as parts where considerable adherence to European conventions may be discerned. Figure 1, from the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, provides examples of how the human form was usually represented in pre-Conquest central Mexican art. The figures were rendered in profile as two-dimensional planes, faces drawn with a continuous line; the eyes were not framed by eyebrows, even if their shape and angle varied, depending on the need to represent expression, and their gestures defied the limitations of anatomic accuracy. Within the narrative of the composition, rank, role, or identity may be inferred through context and/or attributes, such as body paint, jewelry, or other elements of the attire. Indeed, while in many examples of paintings in murals, manuscripts, and ceramics from different regions and historical moments of Mesoamerican history, scholars have identified the use of calligraphic or parallel lines of different widths in order to define details and underscore material, or to illustrate textural contrast and depth (Brittenham Reference Brittenham2008:108; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2004:250), in central Mexican manuscript painting, the representation of animate and inanimate forms remained greatly conventionalized.

Figure 1. Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, ff. 23–24. Image courtesy of the National Museums Liverpool, World Museum.

In folios 4–26 and 29–31 of the Matrícula, all the imagery, from beasts, feathers, and bundles of cloth to toponyms and human faces, are unmistakably pre-Hispanic in their style. However, in folios 1, 2, 3, 27, and 28, we may identify distinct signs of European influence. Let us begin by focusing on folios 1, 2, and 3 of the Matrícula (Figures 2–4). It is visible to the naked eye that the artists who drew the faces of the individuals depicted in those folios followed what seems to be a Europeanized style. Human faces were drawn with square jaws, tall and long noses, and expressive eyebrows. Each one was differentiated from the next almost bordering with the notion of portraits. The individualization of these images is very evocative of the style used by tlacuilos of the later sixteenth century. Beyond any possible comparison of the Matrícula's imagery with early colonial sources such as the Codex Borbonicus, where imagery maintains a close resemblance to pre-Hispanic practices, or with later ones like the Beinecke Map, where the artists have expanded their tastes and methods, incorporating elements of European provenance, it is striking how modern they are in comparison with their direct equivalents in the Codex Mendoza, the Matrícula's closest extant cognate manuscript.

Figure 2. Matrícula de Tributos, f. 1. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Figure 3. Matrícula de Tributos, f. 2. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Figure 4. Matrícula de Tributos, f. 3. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

The case of the Codex Borbonicus is especially indicative of an early moment in the contact between pre-Conquest and European traditions (Figure 5). In spite of the presence of Spanish glosses that seem not to have been added, but rather considered for the composition of the manuscript, the imagery of the first section of the Codex Borbonicus shows adherence to traditional conventions. The bodies and faces of individuals were conventionalized, rendered in profile, deprived of individuality, contextualizable only by attribute, surroundings, or regalia. The manuscript's second section, focused on a less emblematic representation of rituals of the Mexica calendar, shows individuals in action, their sinuous bodies moving through the plane of the page, engaging each other in dance and sacrifice (Figure 6). And yet, here, too, the artists drew and painted in accordance with pre-Hispanic traditions, painting the surfaces and drawing the frame lines with brushes of different widths to show volume and depth. We see such pictorial conventions in the Matrícula in places such as folio 21 (Figure 7), where human faces evoke traditional forms of painting, thus rooting the manuscript in pre-Conquest practices.

Figure 5. Codex Borbonicus, f. 4, detail. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 6. Codex Borbonicus, f. 28, detail. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 7. Matrícula de Tributos, f. 21, detail. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

By contrast, a comparison with the imagery of the Beinecke Map (Magaloni Reference Magaloni, Miller and Mundy2012), a 1560s work of tlacuilolli from Tenochtitlan, finds more similarities with the imagery of the Matrícula's first three folios. This may be seen in the representations of Mexica lords Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin and Diego de San Francisco Tehuetziquilitzin, as well as in several of the unknown individuals related to the different pieces of land that are the subject of the map (Figures 8a–8e). It seems impossible to ignore the stylistic connection that exists between these and many of the faces in the first three folios of the Matrícula: expressive eyebrows, severe eyes, squared jaws, individualized lips.

Figure 8. (a–e) Beinecke Map, details. Images courtesy of Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

However, a comparison between the imagery of the Matrícula and Part 2 of the Codex Mendoza, whose dating ranges between the early 1540s and the 1560s, problematizes even more the possibility that the manuscript may date in its entirety from the late pre-Hispanic period. (For the dating of the Codex Mendoza, see Domenici Reference Domenici and Tejada2020; Gómez Tejada Reference Gómez Tejada and Tejada2020; Mundy Reference Mundy and Tejada2020). Figures 9a and 9b compare the representations of the lords of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco from the Matrícula's folio 3 and the Codex Mendoza's folio 19r. While in the Matrícula a total of 34 human faces bear the influence of European style, in the composition of the Codex Mendoza, these same human faces were drawn with the soft, continuous stroke of the conventionalized Mexica depiction of the human face—a two-dimensional plane punctuated by a rounded nose and jaw, almond-shaped eyes, and no eyebrows to frame the face or grant it expression.

Figure 9. (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 3, detail; reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; (b) Codex Mendoza, f. 19r, detail; courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Further comparison between the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza illustrates even more the different representational styles of both manuscripts. In the Matrícula, several zoomorphic glyphs were drawn conforming to European notions that contrast with the traditionally Mexican ones in the Mendoza. In folio 1 of the Matrícula, we see that the “mountain-monster + hand” glyph (Oztoma) bears the signs of Europeanization (Figures 10a and 10b): the position of the hand, foreshortened and flexed, seems to adhere to European practices more than pre-Conquest ones. We see similar cases in folios 27, 28, and 29 of the Matrícula. In folio 27, we see a fully European depiction of a rabbit, drawn with a round body and a convex face, represented in full profile, which functions as the glyph for Tuchtlan (Figures 11a and 11b), as well as a painterly rendering of the glyph for Acazatla, which both stand in stark stylistic opposition to their analogues in Codex Mendoza (Figures 12a and 12b). The rabbit of the Matrícula contrasts with the more elongated body of the rabbit of the Codex Mendoza, whose almost canine snout and the two teeth that have been drawn on the same side of the face, adhere to traditionally pre-Hispanic conventions. In the following folio, a native porcine figure, perhaps a peccary, stands as a glyph for Yxcoyamec (Figure 13a), but again, the rendering of the animal seems more akin to a European representation of a boar than to that of a native porcine; its upward-pointing fang contrasts with those of the animal in the Codex Mendoza (Figure 13b).

Figure 10. Otzoma glyph: (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 1, detail; reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.; (b) Codex Mendoza, f. 18r, detail; courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Figure 11. Tuchtlan glyph: (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 27, detail; reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.; (b) Codex Mendoza, f. 50r, detail; courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Figure 12. Acazatla glyph: (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 27, detail; reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.; (b) Codex Mendoza, f. 50r, detail; courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Figure 13. Yxcoyamec glyph: (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 28, detail; reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.; (b) Codex Mendoza, f. 51r, detail; courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Considered as a group, the representations in folios 1, 2, 3, 27, and 28 of the Matrícula show how Europeanized parts of the Matrícula can be. At the same time, by contrast, they highlight how a colonial manuscript like the Codex Mendoza can be traditionally Mexica in its visual vocabulary. This observation, which considers the possibility that the Matrícula incorporates pre-Hispanic and colonial material, on the one hand challenges the idea that the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza were made in the same workshop, as argued by Batalla Rosado (Reference Batalla Rosado2007). On the other hand, it supports Gómez Tejada's thesis (Reference Gómez Tejada2012:217) of the existence of a group of tributary documents, to which the Matrícula belongs, and which were consulted in the process of making the second section of the Codex Mendoza. Finally, it allows us to ask whether the decision to paint a manuscript like the Codex Mendoza in such a traditionally Mexican manner obeyed practical reasons, such as the age and training of its tlacuilos, or if it was even consciously reactionary for political reasons, as suggested by Gómez Tejada (Reference Gómez Tejada2012, Reference Gómez Tejada, Jansen, Lladó-Buisán and Snijders2019).

REPAIRS AND INTERVENTIONS IN THE MATRÍCULA DE TRIBUTOS

Currently in the care of the National Library of Anthropology and History of Mexico, the Matrícula is stable, although it has visible damage and repairs of different kinds in its folios. Table 1 summarizes, folio by folio, the different interventions identifiable throughout the manuscript. By carefully considering this accumulation of damage, interventions, and expected material wear, we may pose further questions and gain deeper understanding about the original context and history of the manuscript.

Table 1. Repairs, interventions, and evidence of Europeanization in the Matrícula de Tributos.

One initial observation is that all the folios of the manuscript were made from pieces of amatl of different sizes that were pasted together. In some cases, they run through the borders of the folios. In others, we see larger ones that account for over a third of the page. In other cases, still, as in folio 12, we can identify at least three pieces of amatl that were carefully seamed to make up the page. While this is normal in amatl manuscripts, further physical examination of the manuscript would be required to fully understand how its pages were made; I ask whether focusing on this and how it may reveal a process of repair, might pose further questions about the Matrícula's early history.

Folio 1, originally made of two pieces of amatl, has suffered great damage and only its central section survives. Folio 2 has been similarly damaged, but to a lesser degree; most of the damage to the page focused on its margins, and its imagery is mostly legible. Folio 3 by contrast, has been split down the middle, and a good deal of the images that correspond to that section of the folio are missing. In folio 4 we can observe that the page was cut at the bottom, perhaps as part of a repair intervention that took care not to affect the legibility of the toponyms. Such interventions may be seen in most of the manuscript and they provide evidence of a continuous process of maintenance of the manuscript.

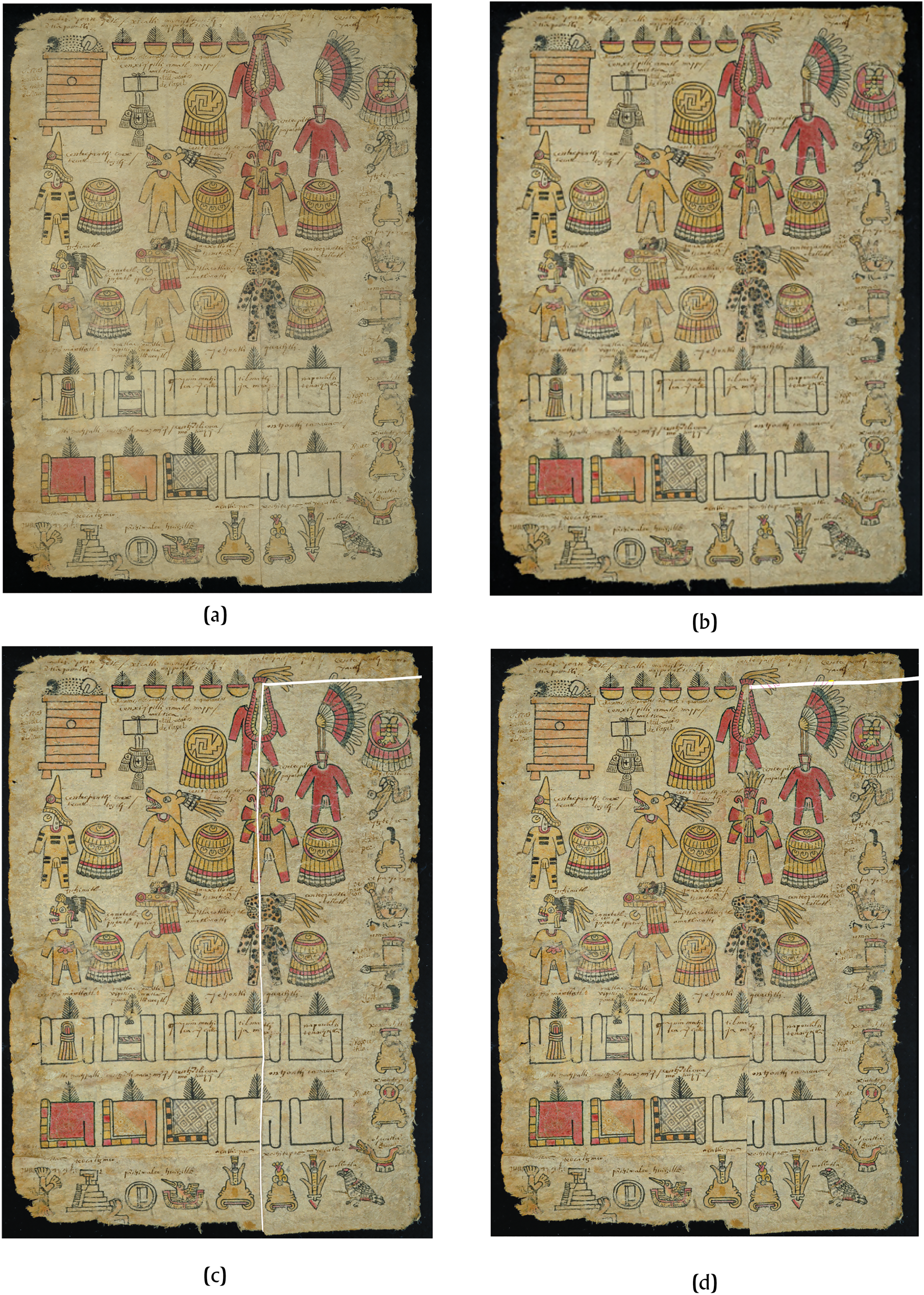

Folios 5 and 12, however, show evidence of further intervention. Folio 5 was made by pasting together two vertical sheets of amatl paper. The first one constitutes two-thirds of the page and the second one the remaining third. Figure 14a shows folio 5 as we see it in the Matrícula. Observe the slight misalignments at the level of the packs of cloth at the bottom of the page, and the slightly more uncomfortable misalignment at the level of the suit of armor and feather headdress at the top of the page. Here, the first question that arises is whether we see the effect of a sloppy repair attempt at some point in the manuscript's history. Figures 14b–14d, however, show what happens when we separate and subsequently align the two pieces of amatl to key elements on folio 5 to correct a possibly failed repair attempt. The first alternative (Figure 14b) shows what happens if we align the two pieces of paper at the level of the lower line of packs of cloth. The next line of packs of cloth, moving upwards on the page, shows an almost imperceptible misalignment. However, this misalignment becomes increasingly marked as one advances upward on the page, at some point making it impossible to fit the overall composition. Figure 14c illustrates what happens if we align the composition at the level of the zapaquapapatol (butterfly) warrior suit. First of all, we notice that the elements of the suit of armor itself do not seem to match each other: the alignment of the butterfly headdress, its feathers, the leg line, seem to come from a very similar depiction, but not from two halves of the same image. The same occurs with the other two suits of armor and the feather headdress. Finally, Figure 14d shows what happens if we align the composition using the headdress of the xopilli (claw) suit of armor at the top of the page. It becomes evident that the headdress itself, while similar, is made of two pieces of different sizes. The other suits of armor beneath it become distorted, as do the packs of cloth. Finally, while the possibility of a repair process which trimmed the edges of the images could have prevented corresponding parts from matching perfectly, here it is difficult to think of such an option. If one were to displace the right third of the page rightward and downward, then the edges of the page itself would not match in the least.

Figure 14. (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 5; (b) Matrícula de Tributos, reconstruction of f. 5, alternative 1; (c) Matrícula de Tributos, reconstruction of f. 5, alternative 2; (d) Matrícula de Tributos, reconstruction of f. 5, alternative 3. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

We see something similar occurring on folio 12 (Figures 15a–15c). There is a slight misalignment at the level of the packs of cloth that becomes more visible further up in the page at the level of the crates of beans and corn. Figures 15b and 15c show what happens if we correct the alignment of the page either at the level of the packs of cloth (Figure 15b) or at the level of the crates of beans and corn (Figure 15c). Furthermore, if one observes the pattern of wear of the edge of the left and right fragments of the page, one notices that they have very different coloration, and that the left side was dirtier than the right, perhaps due to intensive use under a less careful hand.

Figure 15. (a) Matrícula de Tributos, f. 12; (b) Matrícula de Tributos, reconstruction of f. 12, alternative 1; (c) Matrícula de Tributos, reconstruction of f. 12, alternative 2. Reproduced with authorization by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

On the one hand, they may show a process of conservation of the manuscript through cropping and repasting pages. However, while the practice of making pages by pasting smaller pieces of paper is common in amatl manuscripts, and in many a folio of the Matrícula, such as folios 2, 22, 23, 26, and 29, we may see this happening without altering the proportions of the composition, what catches the eye is that in both folios 5 and 12 this is simply impossible.

While one may consider that amatl does not behave like European paper and it may stretch like cloth, it is also true that if that were the case in folios 5 and 12, the edges of the page and the proportions of the images and their placement within the composition would be totally altered. Such stretching of the paper would invariably distort and damage the images: either the suit of armor or the bundles of cloth would be warped or their frame lines or colors within would be crackled. To the contrary, the person who repaired the folios sought to align the images as best they could, maintaining the proportions and overall harmony of the composition, with the least cost to its internal coherence.

Thus, considering that contrasting styles within the manuscript would argue for the Matrícula to be composed of a collection of sheets from at least two sources of colonial and pre-Hispanic provenance, might we consider the possibility that these folios were made by inserting fragments from different exemplars of the same document? If so, they may not only show a process of conservation through the cropping and repasting fragments of the same document, but at the same time, one of recycling documents of interest during the colonial period. Further scientific research into this manuscript will shed light on this question.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the evidence presented that at least parts of the Matrícula de Tributos were made in colonial times and that some of its folios were repaired, we ask what role such a document could play in the colonial period? Perhaps it played a role in the continued extraction of tribute in kind for the benefit of colonial authorities, both Spanish and those from the surviving Mexica elite. The monetization of taxes and tributes was a slow process, which, although high in priority in the orders that Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza received in 1535 and 1536, continued as an unfinished process until the end of the 1540s. The text of the orders that Mendoza received read as follows:

E porque soy ynformado que los dichos yndios pagan los tributos e servicios que deven en mantas e meiz e otras cosas de la tierra que no se saca valor, vos ynformeys que manera se podria tener con ellos para que los dichos tributos que ansy pagan en maiz e mantas e otras cosas dela tierra se comutase todo ello a cierta cantidad de oro o plata en cada un año …

… y otro ynconveniente mayor que a causa de no aver moneda los yndios no tienen con que ny pueden pagar los tributos e servicios que nos deben syno en mantas y otras cosas de que no se puede sacar su valor (Consejo de Indias 1923:pto. 2-2-1, r. 63).

These two excerpts from Viceroy Mendoza's orders, cast at least some light on the role of tributary documents like the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza, possibly as tables of conversion between foodstuffs, finished products like cloth, jewels, or commodities like dies and the newly imported monetized system. Such conversion would also have allowed collectors to place a value on tribute paid in labor and establish the tributary load to different communities in a manner that would be equivalent to what they were charged under the Mexica (Castañeda de la Paz Reference Castañeda de la Paz2011).

Yet another role for documents like the Matrícula de Tributos may have obeyed political needs. In her recent work on the Codex Mendoza, Mundy (Reference Mundy and Tejada2020) has explored the possibility of considering these documents as instruments that validated the claims to power of specific Mexica families, such as that of Diego Huanitzin, who was a direct descendant of Moteuhczoma, and who, from 1542, struggled to keep control over the indigenous government in Tlatelolco. The work of Castañeda de la Paz and Mundy allows us to suggest that a document like the Matrícula could have had specific uses within the context of the political and economic life of Tenochtitlan until almost the end of the first viceroyalty.

Other possibilities for the use and context of these documents are to consider them as records of lineage and its economic prerogatives, as in the case of the Codex Azcatitlan; as representing the inherent need of ethnic groups to maintain their history by keeping such documents, as for the Codex Aubin; or as evidence of the collection of tributes among indigenous communities as painted documents in the mid-sixteenth century, as evidenced by the Codex Huejotzingo or the Información de 1554 (Scholes and Adams Reference Scholes and Adams1957). Most likely, while the initial purpose of these manuscripts may have been tribute collection or record-keeping, their actual operational context must be considered as an amplified field of uses that shaped the life of the manuscript and which, for our analysis, resists the possibility of a single classification. Engaged with the expanded visual vocabulary of the post-Conquest artistic repertoire, or retreating to the pictorial conventions of Mexica tlacuilolli, the Matrícula speaks not only of the practice of tribute collection, but of the permanence and renewal of a set of social practices after the Conquest. The Matrícula may be considered, in this sense, a work of survival.

Seen in this light, it seems plausible that documents like the Matrícula were composed even after the fall of Tenochtitlan, and were kept, used, mended, and recycled by the surviving native elite to articulate their relationship with their new Spanish overlords and their native commoners. Indeed, while the imagery of folios 8–21, 25, 26, 30, and 31 of the Matrícula could safely be presented as remnants of one or more pre-Conquest tributary manuscripts, the continuous use of the Matrícula for several decades after the fall of Tenochtitlan, and until its arrival in Boturini's collection, could explain its tear, wear, and repair. Further examination of the manuscript, with the varying style of its paintings and the interventions into its pages, may offer interesting possibilities for the post-Conquest production of a large portion of the document, as this manuscript was acted upon in more ways than just adding alphabetic glosses in Spanish and Nahuatl. On folio after folio, we see interventions that range from simple repairs, replacements, and repainted images to those that show evident Europeanization.

The variety of these interventions is significant: first, because it could point toward the existence of a number of similar manuscripts from which fragments and pieces were extracted for the purpose of repairing the document; and second, because it allows us to consider the possibility of a larger sample of similar documents from which others, such as the Matrícula's most famous cognate manuscript, the Codex Mendoza, were copied. Such consideration allows us to group the Matrícula and the Codex Mendoza within the category of Mexica historical and tributary documents and within that of the manuscripts painted to serve the needs of the surviving native elites to exercise political authority among indigenous communities (Mundy Reference Mundy and Tejada2020). Indeed, the Matrícula could have operated within the context of the political and economic life of early viceregal Mexico as an instrument of control within indigenous communities.

Because of the variety of sources from which the pages of the Matrícula seems to have been composed, I propose that the Matrícula stands in a unique place within the history of manuscript painting in the sixteenth century. It seems safe to assert that the several folios which show no Europeanizing interventions may be considered the only extant examples of pre-Conquest Mexica tlacuilolli. At the same time, its many repairs signal the permanence and agency of these manuscripts within the social structures of early colonial Mexico, a practice that is greatly amplified in its impact by the adaptation and renovation of parts of the manuscript during colonial times, as may be seen in the many Europeanized images that punctuate several folios of the manuscript. Therefore, it behooves us to ask whether there was a group or family of like documents to which the Matricula and the evidently related Codex Mendoza belonged. Due to the changing landscape of native politics during the sixteenth century, and especially in Tenochtitlan during the period of the first viceroyalty (1535–1564), and because tribute was formally extracted in kind until 1549, and in this process different branches of Mexica nobility would have had claims to power and hence to tribute, it seems logical to consider that tribute lists such as the Matrícula would have been first commonly used among the Mexica elite; second, linked to historical claims over specific lands; and third, used or kept in relation to genealogical documents that validated such claims.

RESUMEN

Este ensayo considera la posibilidad de que la Matrícula de Tributos sea una colección de folios que incorpora material de varios documentos relacionados, algunos de ellos tan tempranos como la víspera de la invasión española en 1521 y otros de un momento tan tardío como la década de 1560. Los distintos estilos discernibles a lo largo del manuscrito, así como las múltiples intervenciones en sus páginas, apoyan esta afirmación. El ensayo propone asimismo que la Matrícula de Tributos sea el último ejemplar sobreviviente de un grupo más grande de documentos tributarios que circularon en México hasta la segunda mitad del siglo dieciséis. Finalmente, el ensayo coloca a la Matrícula de Tributos en el contexto de documentos que mantuvieron o presentaron un récord de las prácticas tributarias prehispánicas, tanto como instrumentos que registraron obligaciones pasadas, como un medio para afianzar la autoridad y liderazgo político dentro de la élite nativa sobreviviente.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Mary Miller, Claudia Brittenham, Barbara Mundy, Diana Magaloni, and Elizabeth Boone for having offered generous and constructive feedback about this essay.