North Korea's divergence from the ‘mono-transition’ pathway

North Korea represents an important and puzzling case of a surviving communist regime that has not followed the ‘mono-transition’ pathway that has enabled China, Vietnam, and Cuba to survive in the post-Cold War world. In contrast to ‘dual transition’ (democratization and economic liberalization), ‘mono transition’ is characterized gradual economic liberalization under continuing one-party rule.Footnote 1 While the pace of economic transition has varied, the followers of mono transition have exhibited a common sequence that began with official acquiescence with spontaneous marketization or ‘marketization from below’, followed by ‘marketization from above’ in which the authorities introduced gradual supporting reforms (China 1980s, Vietnam 1980s to 1990s, Cuba 1990s to 2000s). These regimes began with the encouragement of for-profit activities (by both state and non-state agents, including foreign capital)—measures initially designed to complement the planned economy than replace it altogether.Footnote 2 The advance of marketization to a critical level was then accompanied by the revision of the official economic ideology. Marking the primacy of the market, China replaced ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ (1980s) with the new slogan of ‘socialist market economy’ in 1992.Footnote 3 The more orthodox-inclined Cuban regime adopted the slogan of ‘prosperous and sustainable socialism’ in 2012 to acknowledge the permanence of the market.Footnote 4

China's stellar economic performance compared to Russia's sluggishness touched off debates about the utility of authoritarianism to market transition and the nature of regime durability. For Brus, a noted East European political economist, China showed how authoritarianism enabled the market reforms to be introduced incrementally while Gorbachev's deliberate weakening of the Soviet regime snowballed into the overthrow of communist rule itself.Footnote 5 For Wintrobe, a formal theorist of authoritarianism, the repressive nature of China's regime enabled it to perform the ‘totalitarian twist’ by overcoming the three main market-reform problems (enterprise accountability, dual pricing, and inflation).Footnote 6 Pursuing very similar economic reforms, the pluralized Soviet regime was left completely paralysed. Detailed case studies of communist regimes on the ‘mono-transition’ path (notably China and Vietnam) have shown how that strategy could reinforce one-party rule by enabling the regime to capture new market spaces.Footnote 7 Within the limits of one-party rule, these regimes have also gradually modified their political institutions (for example, from monolithic to collective leadership, greater intra-party democracy, even local-level elections with non-party candidates) to make them more compatible with the social changes brought about by marketization. These modifications facilitated the evolution of the regimes of China and Vietnam from ‘early post-totalitarianism’ of the 1980s to the ‘maturing post-totalitarianism’ of the 2000s.Footnote 8

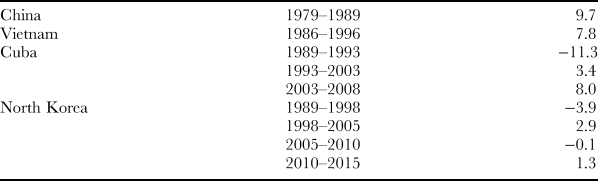

North Korea's divergence from the ‘mono-transition’ pathway is apparent from its slower economic growth during the post-Cold War era. Though not fully reliable for socialist economies, data of estimated gross domestic product (GDP) growth (Table 1) provide at least a rough indicator of the extent to which North Korea has lagged behind not only China and Vietnam, but also Cuba (considered the most reluctant reformer of the three).

Table 1. GDP growth rates among surviving communist countries (per cent per annum)

Source: World Bank; data for North Korea from Bank of Korea (Seoul).

The pattern of growth appears to mirror the inconsistent economic-reform pattern. Just three years after their official launch in 2002, reforms began to stall from 2005. Anti-marketization policies (2005–09) initiated a period of stagnation. The growth rate remained sluggish during 2010–15 despite the return to market toleration from 2010 and succession by an ostensibly pro-reform leader in 2012. This suggests that reform efforts have been inadequate. Apart from the inconsistent reform pattern, North Korea is distinguished by its isolation from foreign direct investment (FDI)—a staple ingredient of ‘mono transition’, owing to its proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD).Footnote 9

Mainstream interpretation: political rigidity as the source of divergence

Many leading authors attribute North Korea's poor economic performance and the inconsistent economic-reform pattern to the effects of its Monolithic Leadership System (MLS). Unlike the ‘mono-transition’ regimes, North Korea has not experienced significant modification of the original Stalinist or ‘totalitarian’Footnote 10 form of governance (i.e. concentration of political and economic power in the vanguard party under top-down leadership).Footnote 11 Threatened by the post-Stalinist trend sweeping the Soviet Bloc after 1956, the Kim Il-Sŏng regime pursued an intensified form of Stalinism that culminated in the establishment of the MLS. Compared with classic Stalinism, the MLS elevated the status of Supreme Leader, or suryŏng, to the extent of creating a high degree of personal power unmatched in the communist world.Footnote 12 Replacing the Marxist–Leninist formulation of the primacy of the vanguard party, ‘Kimilsŏngism’ stressed the decisive importance of the Supreme Leader in advancing the cause of the revolution.Footnote 13 Since the fate of the party, state, and even the nation all depended on the Supreme Leader,Footnote 14 obedience to and protection of the Supreme Leader became the highest duty for all party-state agencies, and for each and every citizen. Identification with national salvation further elevated the status of the Supreme Leader. It bound national sovereignty (chuch'e)Footnote 15 tightly to the Stalinist form of governance. The prevalence of such ‘national Stalinism’ forestalled the emergence of the more innovative forms of ‘national communism’ practised by the regimes of Yugoslavia, China, Vietnam, and Cuba,Footnote 16 all of which would eventually follow the ‘mono-transition’ path.

With the Supreme Leader deified as an indispensable social transformer and national saviour, the MLS developed into a system of ‘totalitarian patrimonial’ rule that combined Stalinist instruments of governance, nationalism, and personal authority.Footnote 17 In contrast to classic Stalinism, the personality cult of the Supreme Leader also extended to key members of his family (wife, son, and ancestors). This justified hereditary succession—a feature unique to North Korea in the communist world. Hereditary succession would supposedly generate a successor of the same revolutionary pedigree as the Supreme Leader, enabling the revolutionary project to advance ‘from generation to generation’.Footnote 18 In practice, hereditary succession was designed ensure the stable transfer of power to a similar type of successor who would preserve the Supreme Leader's legacy (and forestall the post-Stalin and post-Mao experiences of policy revision). The extension of the personality cult to the Supreme Leader's family enabled the regime to portray itself in a benign paternal manner (an image continuously reinforced by propaganda). This has led to characterizations of North Korea as a ‘corporate state’Footnote 19 and as a ‘family state’.Footnote 20 The familial aspect was much stronger in North Korea than in other communist regimes where a degree of familial influence also prevailed (notably Romania and Cuba).

These ‘totalitarian patrimonial’ features would seem to make North Korea uniquely resistant to economic reform. By ensuring the stable transfer of power to a similar type of successor, hereditary succession also forestalled the political-succession struggles that provided the impetus to economic reform in the Soviet Union and China. The typical side effects of reform (rise of non-state economic agents, dilution of loyalty by materialism, weakening of information control) that have challenged the mono-transition regimes (notably China during the Tiananmen Crisis of 1989) have the potential to be fatal to North Korea's ‘totalitarian patrimonial’ rulers. They stand to lose their personalized control over economic resources and they become vulnerable to the inflow of outside information (especially from rival South Korea) that may question the official accounts of their achievements, in effect eroding both the material and subjective bases of their personality cults. It is not that North Korea's rulers do not understand the benefits of economic reform; rather, they are too risk-averse to implement reform in a decisive manner. Trapped in a ‘reform dilemma’, it is political risk aversion and traditional ideology that the ultimately prevails over half-hearted reformism.Footnote 21

Some studies have attempted to show how, over two decades, the political interests of the rulers thwarted the economic reforms needed to boost national welfare. In response to the famine of 1995–97 (‘arduous march’), the regime chose to safeguard food supplies for the military under the doctrine of ‘military-first politics’ (sŏn'gun chŏngc'hi) rather than release them for popular consumption. The regime did not draw on its financial reserves to import food, but instead appealed for international aid. Those least politically prioritized were forced to fend through informal marketization—a process that was hindered by official criminalization of commercial activities and internal migration.Footnote 22 Although the top-down reforms of 2002 were unprecedented by North Korean standards, they were actually motivated by the regime's political impulse to tame and control the spontaneous market mechanisms unleashed by the famine. Alongside the devolution of authority and introduction of incentives, the regime was introducing monetary and financial measures to destroy private wealth (by price appreciation). In other words, pro-market measures were simultaneously countered by anti-market ones.Footnote 23

The period of reform was also very brief. From late 2005, the regime attempted to restore the rationing system and then, in 2008, it announced a restriction prohibiting participation in markets by those under the age of 40. This culminated in attempts in 2009 to turn general markets back into farmers’ markets. Later that year, the regime attempted to destroy accumulated private wealth by currency redenomination. Marketization was happening in spite of, and not because of, the regime.Footnote 24 The ‘reforms’ of the current Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime are said to follow a similar pattern of acknowledging the ‘facts on the ground’ that it cannot controlFootnote 25 while avoiding fundamental market-enhancing reforms (for example, legal safeguarding of private property rights, official marketization of the factors of production, genuine openness to FDI). One empirical study of the post-succession personnel structure of the current Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime suggests that the political economic pattern is continuing as before.Footnote 26 Moreover, the frequent use of terror by Kim Chŏng-Ŭn would not appear to provide a stable environment for marketization.

Unable to fully restore the state allocation system, the regime acquiesces to marketization to the extent necessary for its survival. Writing about the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Hellman observed how the winners of partial marketization constituted the biggest obstacles to comprehensive reform.Footnote 27 Lacking democratic institutions of any sort and with state ownership still prevalent (hence I use the term ‘crony socialism’), North Korea arguably represents the most extreme example of this phenomenon. The core power agencies of the party-state monopolize the most lucrative foreign-exchange activities (raw materials). To lock in their privileges, the regime and its chief stakeholders maintain the existing institutional environment. This enables them to stifle the emergence of competition from independent entrepreneurs.Footnote 28 Denied access to the most lucrative opportunities, most non-state economic agents feed off the economic crumbs of marketization. This ‘economic logic of autocracy’ means low growth, low productivity, and continuing poverty for the majority.Footnote 29 This is because export earnings (or ‘rent income’) are not reinvested into boosting productivity (for example, investment into higher-value manufacturing) but distributed according to political loyalty or consumed wastefully (for example, construction of propaganda monuments or ski resorts).Footnote 30 North Korea's external troublemaking is said to follow from domestic political and economic rigidity. To supplement its inadequate resources, the regime resorts to nuclear leverage in place of serious economic reform.Footnote 31 Thus, North Korean diplomats have constantly underlined their country's difference from ‘mono-transition’ regimes like China or Vietnam.Footnote 32

Alternative interpretation: economic flexibility despite political rigidity

The alternative perspective is based on economic indicators suggestive of better performance. Supplied by Seoul's Bank of Korea, standard GDP estimates have been criticized for neglecting the role of the informal economy.Footnote 33 The inclusion of the service-oriented informal sector would probably add one or two points to the GDP growth rate.Footnote 34 The rapid growth of trade since 2010 would also suggest a much higher rate of GDP growth. Total trade (including inter-Korean trade) grew from US$ 5,093 million (2009) to US$ 8,966 million (2015).Footnote 35 The level of trade would suggest recovery of GDP to the pre-crisis levels (at the worst point of the famine in 1997, total trade was US$ 2,490 million).Footnote 36 Analyses of North Korea's own budget data show revenue growth to have constantly exceeded expenditure growth during the Kim Chŏng-Ŭn era.Footnote 37 Using official budget data as the proxy for GDP growth, Frank calculated a robust 6.1 per cent growth rate (2016) and predicted a slower but respectable 3.1 per cent for 2017 (probably owing to tighter Chinese sanctions).Footnote 38 On the consumption front, international estimates of grain production revealed a four-year upward trend (2010–11 to 2015–16) in domestic grain production that was approaching the pre-1990s crisis levels.Footnote 39 The number of mobile-phone subscribers (a telling indicator of consumerism) increased from 432,000 (2010) to 2.42 million (2013) to 3.24 million (2015)—that is, from 1.76 subscribers per 100 persons (2010) to 12.88 per 100 (2015).Footnote 40

These indicators of economic improvement have coincided with the return to acquiescence with the market in the final years of the Kim Chŏng-Il regime (2010–11) and the consolidation phase of the Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime (since 2012). Measures since 2012 suggest more than acquiescence with the market. Not long after Kim Chŏng-Ŭn assumed the top post of First Secretary of the ruling Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) (27 March 2012), he publicly pledged never to repeat the austerity of the past (15 April 2012). ‘Marketization from above’ was restarted in June 2012 (‘June 28th Measures’) and followed by further measures in May 2014 (‘May 30th Measures’). These micro-economic reforms sought to utilize the profit motive and local autonomy to boost the productivity of state-owned agriculture and light industry—key sectors serving the People's Economy.Footnote 41 While retaining formal state ownership, the measures opened up further opportunities for non-state agents (i.e. entrepreneurs, merchants, and financiers). This ‘socialist management of our own style’ resembled Chinese ‘dual-track’ reforms of the 1980s when the planned and market economies coexisted.Footnote 42 Another aspect of ‘marketization from above’ was the opening-up of new opportunities for non-state agents in key social infrastructural projects (especially housing) and consumption activities (for example, retail and entertainment facilities).

Explanations for the return of ‘marketization from above’ attribute this phenomenon to the combination of structural pressure and political calculus. At the structural level, the 1990s collapse of the formal economy necessitated spontaneous marketization at the grassroots (‘marketization from below’) and devolution of financial responsibility to the core party-state agencies themselves. As a result, the market activities of the people and the core agencies became entwined on many levels.Footnote 43 Marketization became a major source of income for the core agencies (via export monopolies) and greatly enriched their leaders. As a result, those non-state agents with invaluable skills and contacts also prospered as economic partners. Officials at all levels gave protection to market activities in order to supplement their inadequate state salaries. According to Suk-Jin Kim, most restrictions could be ‘bypassed through bribery and punishments are not very severe’.Footnote 44 As North Korea's principal trading partner, Chinese economic entities have been a vital force in fuelling the trend of marketization by promoting for-profit transaction.Footnote 45 More fundamentally, Lee has argued that, since 2013, the principal currencies of transaction have become the US dollar (and other hard currencies) and the dollar-pegged North Korean won. Dollar-pegging means that, regardless of whether economic activity is official (i.e. within the ‘planned’ sector) or informal, it is governed by a capitalist logic (of having to earn dollars or dollar-pegged won).Footnote 46

Against the background of structural pressure, political calculus helps to explain the variations in the marketization trend. Here, the foremost aspect would be the second hereditary succession. In 2008, North Korea faced great uncertainty, both externally (hostile conservative administration in Seoul) and domestically as Kim Chŏng-Il's health sharply deteriorated. To build a solid basis for the accelerated succession by his inexperienced youngest son, Chŏng-Ŭn, Kim Chŏng-Il turned towards closer relations with China from 2009 (while ending the domestic anti-marketization campaign in 2010). Switching its emphasis from aid to for-profit transactions, China pledged investment for ambitious infrastructural and production projects. Trade increased dramatically between 2010 and 2013.Footnote 47 In order to consolidate its power, the new leadership of Kim Chŏng-Ŭn built upon this momentum for marketization. As a third-generation successor, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn could not rely on bloodline inheritance to the same extent as his father (who spent decades moulding his public image).Footnote 48 By contrast, he had to build his legitimacy on performance in the economic sphere. In his first public speech (15 April 2012), he pledged never to return to austerity:

It is our party's resolute determination to let our people who are the best in the world, our people who have overcome all obstacles and ordeals to uphold the party faithfully, not to tighten their belts again and enjoy the wealth and prosperity of socialism as much as they like.Footnote 49

Looking to preserve power over a 40- to 50-year timeframe, the 30-something Kim Chŏng-Ŭn has had to think more about comprehensive economic reform.Footnote 50 Kim Chŏng-Il was reportedly involved in designing his son's formulation of an economy-based ruling strategy.Footnote 51

Delving further into the sources of economic reform: three contentious issues

The alternative explanation invites further consideration of three contentious issues that represent the most common doubts about the advance of marketization in North Korea. First, how does the regime reconcile marketization with the interests of the ‘core constituencies’ that depend on the unreformed economy? ‘Core constituencies’ consist of servicemen,Footnote 52 residents of the capital P'yŏngyang,Footnote 53 munitions and strategic industry labourers, and middle and senior government and party officials.Footnote 54 Some scholars think that these relatively privileged sectors represent ‘the people’ whom Kim Chŏng-Ŭn pledged to protect from austerity.Footnote 55 The regime's interest in perpetuating monolithic rule would not appear to be served by shaking up the inefficient remnants of planning and rationing that benefit these loyalists. For example, the regime appears determined to revive some of the inefficient heavy industries (for example, synthetic fibre, steel) by modifying their operation, instead of focusing on light industry as South Korea had done during the 1960s.Footnote 56 To some critics, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's ‘reforms’ resemble his father's reluctant acquiescence rather than genuine enthusiasm for the market.Footnote 57

Some scholars have expressed doubts as to whether the current regime can free itself from the ‘military-first politics’ inherited from Kim Chŏng-Il. For example, the South Korean government branded Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's ‘line of parallel advance’ (i.e. nuclear-based defence with economic development) as the continuation of the failed military-biased policies of his grandfather and father, but given a nuclear twist.Footnote 58 From a formal theoretical perspective, Wintrobe described ‘military-first politics’ as the ‘militarization of society’—a unique escape act that enabled the Kim Chŏng-Il regime to resort to military rule without incurring the normal trade-off between military and civilian loyalty. However, the insatiable military demand for resources will only make it more difficult for North Korea to carry out economic reforms in the footsteps of China or Vietnam.Footnote 59 These factors lead some writers to predict a future of ‘simple reproduction’ (i.e. slow growth without qualitative change) than the continuous advance of marketization.Footnote 60

Second, the evidence of growth based on trade does not fully dispel the ‘crony socialism’ problem alluded to above. Critics have argued that ‘growth’ represents a superficial improvement based on the temporary increase of raw-materials exports (especially coal and iron ore) to China since 2010. These are said to be classic ‘point-source’ assets, the revenues of which can be easily captured by the state and channelled into showcase projects such as ski resorts, amusement parks, and WMD.Footnote 61 However, the prospect of declining Chinese demand (in response to continuous nuclear provocations) is set to reduce North Korea's foreign-exchange receipts.Footnote 62

More fundamentally, the control of these lucrative raw-material resources under the monolithic regime is based on the proximity to power rather than entrepreneurial skill. To build and maintain the system of monolithic rule, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's predecessors had allocated the most lucrative economic assets to the core party-state agencies, namely the military, KWP, and security agencies. Based on political patronage rather than entrepreneurship, this pattern of profit-taking does not favour long-term investment and growth.Footnote 63 Given that economic benefit is derived from power, the cronies have no incentive to promote market institutions that might nurture competitive entrepreneurship.Footnote 64 On the contrary, they stand to benefit from crackdowns that restrict competition.Footnote 65 Under this ‘economic logic of autocracy’,Footnote 66 the economy remains trapped in low-productivity raw-material exports while the wealth gap widens in favour of the cronies.Footnote 67

As the dispenser of patronage, the Supreme Leader reinforces his own power and resources by encouraging competition among the core agencies.Footnote 68 The highly publicized purge of Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's own uncle, Chang Sŏng-T'aek (reputed number two of the regime), in 2013 illustrates the workings and excesses of this method of rule. Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's father had allowed Chang and his Administration Department of the KWP to acquire an ‘economic small kingdom’ in order to counterbalance the privileged military and the Organization and Guidance Department of the KWP.Footnote 69 While the immediate cause of Chang's downfall was his lieutenants’ defiance of Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's direct order (to surrender a fish farm), the economic background to the collective upsurge against him was his domination of the lucrative export of coal, cutting out other influential agencies, and even the Supreme Leader.Footnote 70 After the purge, some of Chang's assets were reportedly reacquired by the military, while others went to Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's own economic office.Footnote 71 This episode suggests that, despite claims of reform, ‘crony socialism’ has not been replaced by a more rational allocation of foreign-exchange assets.

Third, how does marketization advance in the presence of a regime committed to monolithic rule? Spontaneous marketization has weakened the regime's surveillance capacitiesFootnote 72 and even sparked unorganized political dissent.Footnote 73 Although the current regime has not attempted to reverse marketization, ambivalence persists. For example, in his address to the Seventh Party Congress in 2016, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn repudiated ‘reform and openness’—the slogan associated with China's ‘mono-transition’ path: ‘Despite the filthy wind of “reform and openness” blowing in our neighbourhood, we let the spirit of military-first rifles fly and advanced according to the path of socialism that we had chosen.’Footnote 74

Monolithic rule is not conducive to the development of market-supporting institutions, especially property rights based on the rule of law.Footnote 75 The political environment remains inhospitable to entrepreneurship. For example, surveys of defectors found that party members did not engage in commerce directly, but instead preferred to use their power to extract rents. Thus, the merchant class came predominantly from the middle and lower classes rather than those with the best class backgrounds or sŏngbun (‘composition’) (i.e. history of family service to the regime).Footnote 76 This behaviour would suggest that enterprise exists in spite of the regime, and not because of it. For SmithFootnote 77 and Choi,Footnote 78 the violent purges of the Kim Chŏng-Ŭn era are symptomatic not of monolithic rule, but of divided elites fighting over market opportunities. In their view, this vicious high politics demonstrates that marketization is well entrenched. Need and greed have supplanted the hegemonic (i.e. consent-based) dimension that previously underpinned monolithic rule. However, this type of zero-sum environment of political contestation would not appear to be conducive to the development of market institutions either.

Framework for re-examining the sources of economic reform

The three contentious issues above represent the most common doubts about the reform commitment of the North Korean regime despite the recent announcements of reform and positive economic signals. I will show how the sources of economic reform (structural factors and political calculus) identified above have enabled these constraints to marketization to be overcome. This can be represented as in Table 2.

Table 2. Sources of economic adaptability and three contentious issues

Table 2 illustrates the effects of both structural trends and political calculus. As for the regime's dependence on its core constituencies, the structural legacy of failed planning and economic collapse has forced the majority of core constituents to depend on the market to some degree. Another structural factor is the nature of the MLS itself. As a system that maximizes the authority of the Supreme Leader, it gives him great autonomy to redefine the economic ideology in market terms. In terms of political calculus, the political consolidation of the new regime depends on funds, for which the market and rebalanced expenditure (‘parallel advance’) represent the obvious sources. The rebalance is reflected in the tighter leash on the military, including curtailing of some of its foreign-exchange privileges.

In relation to ‘crony socialism’, the monopolies and oligopolies dominated by core agencies can only function on the basis of cooperation with non-state agents (who possess the requisite funds and skills). This need brings about wealth-sharing and wealth creation as well as bureaucratic profit-taking. Structural interdependence was reinforced by political calculus, which led the Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime to introduce micro-economic measures (in agriculture and light industry) based on profit motive and expanded opportunities for non-state agents. The purges related to foreign-exchange assets represent efforts by the centre (Kim Chŏng-Ŭn) to strengthen its control over the finances of the core agencies while cooperative relationships with non-state agents remained intact.

As for the constraint posed by monolithic rule, mutual dependence and repeated interaction are leading to the emergence of a ‘symbiosis’ between core agencies and non-state agents. Policy reversal has become increasingly difficult. The regime's politically motivated drive to boost consumption further reinforces mutual dependence. For example, the regime seeks private support to deliver in politically prioritized areas such as housing. Finally, by improving the official finances, marketization enables the regime to pursue ‘civilized country with socialism’ as an alternative to regime modification experienced under the ‘mono-transition regimes’. We can now explore each of these issues in more detail.

Marketization and the ‘core constituencies’

By the time Kim Chŏng-Ŭn assumed power in 2012, the ‘core constituencies’ had already been exposed to two decades of crisis-induced marketization. First permitted by the Kim Il-Sŏng regime in the 1980s, informal market activities gained momentum as the termination of Soviet and Chinese ‘friendship prices’ (1990–91) brought the official economy to the edge of collapse. When three consecutive years of bad weather (1995–97) tipped the country into famine (so-called ‘arduous march’), the Kim Chŏng-Il regime drastically streamlined the central-planning process. Apart from some ‘special enterprises’ (for example, defence-related and heavy industries) and infrastructure (especially power generation), central government devolved economic responsibility down to local-level administration, enterprises, and farms to provide for their own production and consumption needs. While some sections of ‘core constituencies’ (especially workers of ‘special enterprises’) could rely on state provision to a greater degree, most economic units and individuals came to rely on informal market activities to some degree.Footnote 79 The informal sector became the principal provider for people's livelihoods by 2000—a telling indicator of exposure to marketization.Footnote 80

This background of structurally driven marketization was reinforced by the political motivations of the new Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime. As mentioned above, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn could not rely on bloodline inheritance to the same extent as his father and had to build his own performance-based legitimacy.Footnote 81 As a hereditary successor, he identified with his father's practical achievements, especially nuclear development and preservation of the North Korean state despite the collapse of the Soviet Bloc. On the other hand, he was seeking to distance himself from economic hardship—the most unpopular feature of his father's ‘military-first’ era. To distance himself from his father's unpopular legacies while establishing his own identity, he looked to economic development. While he did not think it wise to repudiate his father's security legacy, he also sought to rebalance the regime's priorities. His first public speech of 15 April 2012, when he pledged that austerity would never be repeated (acknowledging the pain that austerity had brought), was an early indicator that consumption (People's Economy) would receive greater priority.

The pattern of policy announcements and appointments following the 15 April speech suggested the emergence of a reform pathway designed to enhance the core sectors’ reliance on the market. On 28 June 2012, the authorities announced the introduction of ‘New Economic Management System in Our Own Style’. These 6-28 Measures, as they became known, outlined policies for giving greater autonomy to the agricultural and light industrial sectors (core sectors of the People's Economy). The policies resembled the early stage of China's ‘reform and openness’, even though North Korea never embraced that slogan. In contrast to the aftermath of the 7-1 reforms of 2002, the 6-28 Measures were reinforced by the further measures of 30 May 2014. Under these 5-30 Measures, Kim Chŏng-ŭn referred to the ‘socialist corporate responsibility system’.Footnote 82 The switch towards economic reform was also apparent from the reappointment of Pak Pong-Ju to the position of prime minister (1 April 2013). As one of the architects of the 2002–05 cycle of reform, Pak had served as premier during 2003–07. He was one of the ‘Big Four’ technocrats who led the 2002–05 reforms. At the Seventh Party Congress of May 2016, Pak was further promoted to the five-member Presidium (equivalent to China's Standing Committee) of the Politburo and also to the KWP's Central Military Committee.Footnote 83

Any serious attempt to rebalance towards popular consumption meant shifting resources away from the military sector, in terms of both reduced central defence expenditure and reassignment of foreign-exchange assets devolved to the military under Kim Chŏng-Il's ‘military-first’ policy. Following on from his 15 April speech, Kim Chŏng-ŭn gave further hints of this rebalance. For example, in a meeting with senior officials in mid-June 2012, Kim had reportedly said ‘food grain is more important than bullets today’.Footnote 84 Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's pattern of public activities between 2012 and 2015 revealed a shift towards a greater emphasis on economic rather than military goals.Footnote 85 The rebalancing was officially acknowledged by the announcement of the doctrine of pyŏngjin nosŏn or ‘line of parallel advance’ (i.e. between nuclear-based defence and economy) in April 2013. ‘Parallel advance’ was a term first used by national founder Kim Il-Sŏng half a century earlier. This marked a modification of the Kim Chŏng-Il regime's emphasis on ‘military first’.Footnote 86 Of course, lip service continued to be paid to the achievements of ‘military first’. Marking the announcement of ‘parallel advance’, the headline of the KWP newspaper, Rodong Sinmun (5 April 2013), quoted from Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's speech: ‘The most important and desperate task facing our party today is pressing the development of an economically powerful country and dramatically improving the lives of the people.’Footnote 87

In reality, Kim Il-Sŏng's ‘parallel advance’ initiated several decades of military build-up and austerity. The use of the slogan in the 2010s was designed to connote continuity and association with the optimistic early 1960s but the content represented a shift away from military bias. One year before the announcement of ‘parallel advance’ in April 2013 and the reappointment of Pak Pong-Ju as premier, some tentative changes were already occurring in this direction. The first sign of change came in April 2012 when the Cabinet—the part of the regime responsible for the People's Economy—was designated as the ‘economic headquarters’. Kim Chŏng-Ŭn reportedly said: ‘We must establish discipline and order in a way to concentrate all economic problems in the Cabinet and solve them under its command should we make a revolutionary turn in improving the standard of people's living and turning the country into an economic power.’Footnote 88

Despite being a new leader, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn appeared to have the political authority as well as the political incentive to initiate ‘marketization from above’. To begin with, he occupied the position of Supreme Leader within the MLS. While it has been criticized for inhibiting economic reform, the MLS also invested the Supreme Leader with a high degree of autonomy to redefine the official ideology as he saw fit. The only absolute principle was total allegiance to the Supreme Leader and his prevailing orders. This had enabled Kim Chŏng-Il to dismantle much of the elaborate central-planning system created by his father and justify the move towards ‘self-responsibility’. Similarly, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn also had leeway to redefine what constituted ‘socialism’ and the sacred official principle of chuch'e (‘national autonomy’).

As a share of the government budget, military expenditure has been officially (under) stated as either 15.8 per cent (2009–12, 2016) or 15.9 per cent (2014 and 2015).Footnote 89 However, it is possible to identify tentative shifts away from military bias in other ways. One significant development was the transfer of military rights for most foreign-currency projects (except for arms exports) to the Cabinet. This was a response to the military's corruption and inflexibility as the leading economic institution.Footnote 90 The military chief of staff, Vice Marshal Ri Yŏng-Ho, was dismissed in July 2012, ostensibly for opposing this transfer. Ri's dismissal was the culmination of a longer process of reallocating economic authority. In February 2012, a ‘party life guidance group’ was dispatched to military units with the aim of uncovering the abuse of authority, including activities related to foreign exchange. Foreign-currency factions and clans underwent disciplinary measures, with many senior officers being replaced. The military's wartime rice reserves were released for state ration, thereby contributing to the stabilization of market prices in 2013.Footnote 91 In this respect, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn has been more successful than his father.Footnote 92 The annual number of soldiers mobilized for economic tasks also doubled under Kim Chŏng-Ŭn, to about 200,000.Footnote 93

The transfer of foreign-exchange rights and the dismissal of Vice Marshal Ri constituted a part of a wider process of reining in the military that had been empowered under Kim Chŏng-Il. Since 2012, the military has been subject to change by purge, reshuffle, new appointments, and intensified KWP supervision. As the new Supreme Commander, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn promoted another 23 general-rank officers in February 2012.Footnote 94 By the end of 2012, the regime had removed not only Vice Marshal Ri, but also the other three top military officers who had accompanied the hearse at Kim Chŏng-Il's funeral in December 2011.Footnote 95 The defence minister changed six times between 2013 and 2015. One (Hyŏn Yŏng-Ch’ŏl) was executed in April 2015 for ‘militarism-based bureaucracy’ or putting professionalism over politics and for showing irreverence towards Kim Chŏng-Ŭn. This showed that no measure of disobedience would be tolerated. The General Political Bureau that supervised the military for the KWP was strengthened and placed under the leadership of party professional Choe Ryŏng-Hae (now accorded the highest military rank of vice marshal).Footnote 96

‘Crony socialism’: wealth-sharing and wealth creation

‘Crony socialism’ began in 1974 when heir apparent Kim Chŏng-Il began to reassign trading companies from the Ministry of Foreign Trade to Office 39—a newly created KWP financial unit. This enabled the Kims to divert foreign exchange from the official People's Economy into the hereditary succession project.Footnote 97 The ‘patrimonial’ economy became more pronounced as the official economy deteriorated in the early 1990s. In 1991, the regime created the New Trading System that set foreign-exchange targets for all core agencies. Different branches of the same agency established their own trading companies—a trend replicated at the local level.Footnote 98 During the famine, these core agencies were given control of foreign-exchange assets in order to support themselves and to contribute to central funds.Footnote 99 Kim Chŏng-Il himself would allocate the trading licences or wakku Footnote 100 required for participation in foreign-exchange activities. Core agencies (usually operating through a trading company) would make a business proposal and seek Kim's approval. If approved, the proposals would become ‘party directives’.Footnote 101 Prioritized under ‘military first’, the military came to dominate cash generators like raw materials, fisheries, mushrooms, and ginseng.Footnote 102

‘Crony socialism’ thus appears to concentrate wealth among the rapacious elites instead of creating new wealth. This would coincide with estimates of stagnant GDP. However, this perspective overlooks the extent of financial power accrued by non-state agents as a result of ‘marketization from below’ since the 1990s. The entrepreneurship that sprang up in response to the failure of state planning also penetrated into the state sector. Kim and Yang identified two types of private entrepreneur.Footnote 103 ‘Necessity-driven’ entrepreneurs were motivated by difficult circumstances and confined their activities largely to private farming and handicrafts. The more ambitious ‘opportunity-driven’ entrepreneurs were those whose activities reached into the state sector by way of investment and management.Footnote 104 From this group sprang the private financiers, or tonju (literally meaning ‘owner of money’), or the new rich, who had amassed an average of US$ 1 million—a huge sum by North Korean standards.Footnote 105 They have become important economic partners of the state.

Mutually profitable relationships existed at many levels. At the most basic level, private entrepreneurs would obtain official permission to start businesses using state assets. For example, individuals would rent space from the state to open up a service business or to use as storage space. To do this, they would borrow titles from state agencies and enterprises for a fee.Footnote 106 This ‘name lending’ or ‘wearing the red hat’ resembled the Chinese ‘registration’ (guahao) system of the 1980s. A more ambitious form of cooperation was ‘loan investment’ whereby tonju would invest into state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in return for interest (profit). Because they lacked money, state entities (factories, stores, trading companies, and even banks) would turn to tonju for loans, investments, and outsourcing of contract processing.Footnote 107 For SOEs facing government production quotas (i.e. those key plants within the official economy) without receiving the necessary inputs, they had to turn to tonju for finance.Footnote 108

Given its power, the military made the most attractive institutional patron for aspiring entrepreneurs.Footnote 109 But, even for that powerful core agency, the relationship ran both ways. To profit from its control of assets, it had to cooperate with civilians. Despite having enormous manpower, it relied on support from sub-contract civilian labour.Footnote 110 Sub-contract labour consisted of under-employed workers from the People's Economy who retained their formal work registration out of political requirement. Like other state agencies, the military needed investment and entrepreneurial skills. In this way, the core agencies and entrepreneurs (especially tonju) became interdependent. To maintain their authorization, or wakku, the core agencies would be expected to contribute to the centre's ‘revolutionary funds’.Footnote 111 By extension, the Supreme Leader also came to depend on business cooperation with non-state agents. Despite reversion to anti-marketization from late 2005, the Kim Chŏng-Il regime continued to facilitate private investment into key export sectors. For example, the ‘Regulations for the Development and Operation of Small and Medium Sized Mines’ (2006) allowed any agency or business organization to develop and operate mines independently once they had received state authorization.Footnote 112 Yang has usefully summarized the symbiotic relationships in the export sector as in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interaction between state and non-state agents in the sphere of foreign trade.

The above discussion has established that, in order to prosper, the core agencies need the cooperation of informal business partners and informal workers, with whom profits would be shared. The question remains as to whether ‘crony socialism’ allows qualitative change (towards higher-value-added production) or does it remain trapped in low-productivity raw-material exports? The profile of exports to China—the principal market for these ‘point-source’ assetsFootnote 113—points to qualitative change rather than stagnation. While raw materials remained the dominant export, other exports are also significant. For example, manufacturing export based on textiles (a typical export of early-stage developing economies) accounts for a significant share. As share exports to China, textiles accounted for US$ 108 million (21.6 per cent) (2005), US$ 186.4 million (15.7 per cent) (2010), US$ 587 million (20.1 per cent) (2013), and US$ 799.3 million (32.2 per cent) (2015).Footnote 114

The introduction of reforms aimed at resuscitating the productivity of the People's Economy also differentiates North Korea from typical crony political economies based on primary-resource extraction. Facing competition from the informal markets, the cautious Kim Chŏng-Il regime had already started to do this with the 7-1 measures (2002). Two such policies were the ‘earned income indicator’ and ‘socialist barter markets’. The ‘earned income indicator’ was introduced to evaluate enterprise performance on the basis of quality over quantity. It allowed for autonomous production and distribution. ‘Socialist barter markets’ enabled enterprises to exchange raw materials and parts. They permitted enterprises to exchange a certain ratio of products for materials.Footnote 115 The fundamental problem of the 7-1 measures was that they introduced incentives (higher wages, higher prices, more enterprise and farm autonomy, and so on) without first normalizing production (i.e. restoring productive capacity nearer to pre-crisis levels). Thus, they were more akin to efficiency measures for a sluggish planned economy than recovery measures for a broken one.

The Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime has moved further in the direction of reforms aimed at improving the productivity of the People's Economy. Under the 6-28 (2012) and 5-30 (2014) measures, further incentives were introduced in agriculture and light industry—the sectors responsible for the people's consumption. Table 3 compares the 2002–05 and (ongoing) 2012–15 reform periods.

Table 3. Industrial and agricultural reform in North Korea, 2002–05 and 2012–15

The 2002 reforms showed that, without first investing to normalize production, incentives could not take effect. The official sector continued to be unattractive to workers, as evidenced by their continued drift into the informal sector. In response to the need for ‘pre-investment’, the current government has been more flexible in its economic ideology. While retaining formal state ownership, the government has allowed greater use of private funds. This has enabled private financiers to invest into state-run companies while receiving interest in return.Footnote 116 Alternatively, individual entrepreneurs can lease state facilities and hire workers using their own funds. Provincial governments have also received permission to solicit investment from private sources.Footnote 117 These examples of private participation in state-owned industry show how the state is licensing capitalist activity so long as it remains under nominal state ownership.

This section has argued that, while ‘crony socialism’ undoubtedly exists, the most powerful cronies (the core power agencies) can only profit from their dominance of foreign-exchange assets through input (of money and talent) from non-state agents. This results in profit-sharing between core agencies and non-state agents. This pattern of cooperation persists irrespective of changes in ownership brought about by elite conflict. The growth of trade (with growing volume and composition of manufactures) and the spread of consumerism would suggest that new wealth is being created under ‘crony socialism’ and that it is confined not only to the elites. In respect of wealth creation, the measures taken by Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's regime to boost the productivity (6-28 and 5-30 measures) of the People's Economy have expanded the opportunity for non-state agents to an unprecedented degree. The emphases on rebuilding People's Economy, bolstering the authority of the Cabinet, and reconstruction of infrastructure (especially power generation) indicate that Kim Chŏng-Ŭn is able to set clear priorities for the investment of state resources. As such, his authority appears to be getting stronger rather than being eroded by infighting among elite factions.

Sustainability of marketization under monolithic rule

How sustainable is marketization in the presence of monolithic rule? I will argue that increasing cooperation between state agencies and informal capitalists has created links of interdependence that have become very costly for the regime to rupture. Moreover, the regime has no political necessity to rupture these links because it faces no prospective threat from its entrepreneurial allies. The failure of market reversal during 2005–09 showed how the regime was already tightly locked into market cooperation with non-state agents. Market-reversal policy brought about the very social instability that the regime feared. The capacity of major merchants and financiers to withstand anti-market measures, including currency reform, showed how deeply entrenched marketization had become.Footnote 118 The ill-fated anti-market policies of 2005–09 arose because the Kim Chŏng-Il regime had reluctantly introduced reforms without modifying its economic ideology. By contrast, the current regime has officially committed itself to boosting popular consumption and Kim Chŏng-Ŭn has personally endorsed the profit motive. Whereas Kim Chŏng-Il (26 August 2007) denounced the market as ‘the habitat of anti-socialism’,Footnote 119 Kim Chŏng-Ŭn, referring to agricultural reform, reportedly stated that ‘egalitarianism in the realm of distribution has no connection to socialist principles and has a detrimental impact that reduces farmers’ productivity’.Footnote 120

The regime's growing acceptance of marketization is manifested in the official tolerance of informal property rights under the veneer of state ownership. Although formal ‘property rights’ still do not exist, private property has developed into a ‘social custom’Footnote 121—that is, something that is widely accepted in practice. According to refugees, the three main items of ‘property rights’ are small land plots, market stands, and housing.Footnote 122 The first two items of individual private property also emerged in the early stages of reform socialism in China and Vietnam (i.e. low-value assets that could easily be reconciled with state socialism). The penetration of property rights into the real-estate (housing) sector, however, represents a significant advance. It represents the regime's de facto acceptance of private ownership, usage, and transfer of a high-value asset so long as the appropriate taxes are paid (see below). In the past, the government would have allocated such a valuable asset according to sŏngbun or one's (political) make-up. Now, it is primarily concerned with obtaining revenue.

The range of ‘concealed property rights’ or private property under state guise is expanding. Private ownership of the means of production is permitted if it is incorporated into a state organization.Footnote 123 Many forms of de facto private ownership of productive facilities now exist. First, individuals can engage in cottage industries (family-sized manufacturing activities), private cultivation, and private commerce. Second, individuals can manage a business using a state-run enterprise name (‘wearing the red hat’), using leased state facilities while hiring workers with their own money (in effect, a labour market). Third, recently, it was confirmed that, in 2014, the government had revised the law to permit rich individuals or tonju to invest in businesses. According to Article 38 of the new law: ‘Following the established procedures, the enterprises can get a loan from the bank or mobilize and use the idle currency and funds in the hands of the people to overcome the lack of working capital’ (emphasis added).

This is the first confirmation that the authorities have provided a legal basis for the use of informal savings.Footnote 124 The attitude of the authorities appears to be pragmatic, namely maintaining the appearance of state ownership while relaxing the substance for the sake of reviving production and collecting tax revenue. In effect, the informal capitalists can treat state-owned assets as if they are private assets. At the very least, their ‘property rights’ are secure enough for them to sink money and effort into state enterprises.

Apart from tolerating capitalist activity, the regime is actively soliciting non-state participation in the key projects designed to showcase official concern for popular welfare. The non-state sector is playing a key role in the apartment-construction boom in P'yŏngyang and other cities. A ‘construction alliance’ consisting of central government, core government agencies, financiers, and construction-service providers has emerged in the process. As with trade, most apartment construction begins with core agencies seeking official licences. Having obtained licences, they then contract out to builders (often through brokers) capable of mobilizing funds, materials, and manpower. It is estimated that private contractors are responsible for 80 per cent of apartment construction in North Korea and that one-third of new apartments are traded on the market (i.e. those not directly allocated by the government).Footnote 125 Trading of apartments has become a very lucrative business. The asking price of new apartments reportedly ranges from US$ 100,000 for a downtown 100-m2 apartment to US$ 200,000 for the most expensive apartment located in the upmarket Pot'onggang district.Footnote 126 Given the original purchase price was probably US$ 30,000–40,000, this meant very high profit margins for those with cash to invest in purchase and remodelling for resale. Since the apartments are included in the state construction plan, the private sector is playing a central role in fulfilling the regime's ambitious apartment-construction programme associated with the rise of Kim Chŏng-Ŭn.Footnote 127 The market for apartments shows that the non-state agents feel secure enough to risk sizeable amounts of capital in a long-term venture like construction.

Apart from the real-estate market, the state is actively facilitating popular consumption (especially in P'yŏngyang) in order to build political support and collect tax. Towards these objectives, it has facilitated non-state agents and become a provider in its own right. The reorganization of ‘farmers’ markets’ into ‘general markets’ (2003) expanded the range of products for open sale and created an important source of official revenue.Footnote 128 During the 2010s, this system has developed further. Department stores, general markets, restaurants, and entertainment facilities have proliferated in P'yŏngyang and the surrounding areas.Footnote 129 By 2015, 26 public markets existed in P'yŏngyang, covering all districts, compared to just one in the early 1990s.Footnote 130 Frequent visitors have noticed the development of a thriving Chinese-style facility at the state-owned Kwangbok Area Shopping Centre.Footnote 131 Since 2012, three types of state electronic payment cards have been introduced for cash-free payment at foreign-exchange shops. Easily acquired, these cards speed up purchases and help increase the total volume of financial transactions.Footnote 132 Outside of P'yŏngyang, the ‘state dollar collection system’ also exists. One manifestation is the rental fee levied by the state on vendors at market squares.Footnote 133

What do these developments tell us? First, the authorities have become increasingly confident of living with marketization and consumerism (including the development of a mobile-telephone network), even if it continues to suppress some manifestations (such as South Korean DVDs). Second, by providing consumer products and services previously neglected by the state, the informal sector has also opened up tax opportunities for the state (via the ‘state dollar collection system’). These activities are simultaneously meeting popular demand and contributing to the finances of the state. South Korean estimates of the North Korean government budget (which tend to underestimate) suggest continuous recovery (2009–15) despite international sanctions. The estimates are (US$ billions): 3.7 (2009); 5.2 (2010); 5.8 (2011); 6.2 (2012); 6.8 (2013); 7.1 (2014); and 6.9 (2015).Footnote 134 Third, under the influence of the informal sector (and China), state agents themselves are becoming ‘entrepreneurial’, capable of profitably supplying products and services of increasing sophistication, including credit cards. The improvements concentrated in P'yŏngyang appear to be spreading out to the rest of the country. It would seem the regime is tackling the incentive problem at the heart of state socialism's economic malaise.

The Kim Chŏng-Ŭn regime appears to enjoy a cosy and productive relationship with the nascent capitalists (merchants, entrepreneurs, and financiers). Far from posing a political challenge, these nascent capitalists depend on political patronage.Footnote 135 Given that the assets from which they extract profit remain under state ownership, continuing access depends on maintaining smooth collaboration with the core agencies. In particular, the most profitable activities (for example, export of raw materials, real estate, and construction) depend on collaboration with those core agencies (especially party, military, security) that have the most licensing authority. Without the regime, these nascent capitalists would lose their market space to foreign capitalists. Not only are they locked into interdependence with the regime; they are also divided (by social background, business size, and source of bureaucratic support) to form the basis of any ‘civil society’ capable of confronting the state.Footnote 136 For its part, the regime seems to recognize the nascent capitalists to be safe economic partners. The purges arising from elite conflicts over foreign-exchange distribution affect the leaders of the core agencies rather than their informal capitalist partners. The latter's access to state protection usually remains unchanged.

Historically, the transition towards ‘mature post-totalitarianism’ (characterized by increased consumerism, limited political liberalization, and the modification of political institutions) was accompanied by the de-legitimization of traditional communist values. Regimes instead governed on the basis of ‘pragmatic acceptance’Footnote 137 or ‘social contract’. China and Vietnam have shown how marketization can provide resources for ruling regimes to renew themselves materially (greater capacity for party supervision) and ideologically (promotion of new social values consistent with one-party rule such as nationalism).Footnote 138 In this way, they have avoided the fatal ideological de-legitimization suffered by the Soviet Bloc regimes. The North Korean regime has been even more determined than its Asian counterparts to pre-empt the problems of de-legitimization associated with marketization. Economically, its position resembles the early ‘post-totalitarian’ stage in which the regime has decisively endorsed marketization. In the political sense, however, North Korea remains very much ‘totalitarian’. Marketization, however, has not been accompanied by a political thaw or by the dilution of monolithic rule based on the Supreme Leader. By contrast, intensification of the Kim Chŏng-Ŭn personality cult, the frequency of terror-based purges, and revived leadership role of the KWP since 2010 (as the military's political role has been de-emphasized) serve to demarcate the rigid political sphere from the liberalizing economic one.

This demarcation is also happening in a more sophisticated way. Far from ‘post-totalitarian’ modification of the regime in response to marketization, marketization is utilized to reinforce the monolithic regime's legitimacy (led by the revived KWP). While Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's economy focus appears to be very much attuned to the material aspirations of those in their 30s (i.e. his generation),Footnote 139 his rule is not simply based on ‘social contract’. There is renewed emphasis on ideology. For example, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn has emphasized the achievement of ‘civilized country with socialism’ since 2013. Aimed particularly at youth, ‘civilized country with socialism’ seeks to bind the ‘market generation’ to the regime.Footnote 140 It means boosting social satisfaction by investment of the fruits of economic development into collective benefits (for example, extension of compulsory education; provision of recreational, housing, and retail facilities; improvement of medical provision; development of sporting prowess). Naturally, these collective benefits of growth have been accompanied by parallel ideological efforts to extol the achievements of the ruling Kim dynasty.Footnote 141 In this way, individual consumerism would be balanced by government efforts to nurture pride in the state and loyalty towards the Supreme Leader. Moreover, the nature of the MLS is such that the Supreme Leader has great flexibility in interpreting policy. As such, the regime is less bound by commitment to specific economic principles (such as egalitarianism or central planning). So far, there appears to be no contradiction between marketization and the absence of liberalizing political change. Even those commentators who have doubted the regime's capacity for reform concede that the regime may have hit upon a viable formula for preserving power.Footnote 142

Conclusion

Improved economic indicators and economic-policy trends during the 2010s lend support to the alternative perspective that North Korea is becoming more economically flexible despite its adherence to monolithic rule. This perspective identifies structural forces (the momentum of 20 years of spontaneous marketization) and political calculus (especially regime consolidation following the second hereditary succession) as the driving forces of economic flexibility. This article delved further into three contentious issues often raised in critical response to the alternative perspective. First, it found a subtle but distinctive change in the regime's leitmotif in the direction of economic development (from ‘military first’ to ‘parallel advance’). An indication of this change was the attempt to curb the privileges and power of the military—the ultimate ‘core constituency’. Second, it found that the economic dangers of ‘crony socialism’ are balanced by the core agencies’ interdependence with non-state agents (especially financiers) who are also enjoying more market opportunities owing to official emphasis on boosting popular consumption. Third, regarding the compatibility of marketization with renewed monolithic rule, the current regime appears more habituated to marketization than its predecessor (for example, Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's positive evaluation of profit, extension of informal property rights, non-state agents’ participation in key state projects, and state entrepreneurship in the consumer sectors). In contrast to modification of political institutions under ‘mono transition’, the North Korean regime appears confident that it can reconcile individual prosperity with monolithic politics (‘civilized country with socialism’).

The favourable marketization trends identified above are subject to external conditions not deteriorating further. ‘Parallel advance’ (simultaneous promotion of nuclear defence and economic development) has enabled the regime to rebalance its priorities between military and economy but ensures that North Korea continues to face international isolation, setting it apart from the other ‘mono-transition’ regimes. While North Korea's leaders can take some comfort from the continuation of economic growth amid international sanctions, the tightening of sanctions has inevitably undermined the economy's growth potential. It appears that the North Korean leadership has come to appreciate this dilemma. In the spring of 2018, it initiated peaceful overtures that led to three summits each with China and South Korea and one with the United States of America (as of October 2018), all of which resulted in hopeful statements of agreement. Underpinning this diplomacy was Kim Chŏng-Ŭn's announcement of the road of ‘economy first’ in place of ‘parallel advance’ (March 2018). Having seen authoritarian regimes deposed around the world, however, North Korea will consent to denuclearization only on the basis of ironclad security and economic guarantees.

The reduction of tension and continued advance of marketization will be greatly facilitated by the hopeful diplomatic developments of 2018, the most important aspect of which is the readiness of the United States of America to engage with North Korea. Only this can ease the security obsession driving North Korea's WMD development. In practice, this should mean the improvement of diplomatic and economic relations between the United States of America and North Korea in exchange for a moratorium on WMD testing followed by verifiable denuclearization measures. While it is the most important aspect of engagement, it is also the aspect most vulnerable to derailment, especially on the US side. This arises out of the ability and willingness of the current Trump Administration to stay the diplomatic course in view of the manifold disputes (for example, with China over trade, with its domestic opponents over everything) in which it is embroiled. Moreover, President Trump's lack of liberal-democratic idealism, which has so far facilitated direct engagement with North Korea, is well out of sync with the foreign-policy sentiments prevalent in both major US political parties. Here, the continuing diplomatic efforts of China and South Korea work in the positive direction of bringing P'yŏngyang and Washington together.Footnote 143 The hopeful trends of marketization identified in this article will only be sustained if they are aligned with a peaceful external environment.