1 Introduction

Currently in the US, there is much debate about expert testimony in court. To prevent a ‘battle of the experts’ and avoid the problem of obscure and arcane expert testimony during truly complex cases, both parties may agree to having a judge-appointed expert manage the technical evidence. Judge Posner (Reference Posner2016) himself recently proposed developing a process for court-appointed experts to manage complex technical evidence. The proposition is, however, not uncontroversial (e.g. Kennerly, Reference Kennerly2016) with debates focused on the need to protect and strengthen the neutrality of experts (Sidak, Reference Sidak2013).

As the US reflects on the establishment of court-appointed experts, examination of the practical aspects and tensions between legal and technical experts in the French model of expertise may yield useful lessons. We do not want to defend the French model, as various professional associations have done more or less recently in France (Cour de Cassation, 2007; European Expertise and Expert Institute, 2012), notably to promote this model in the European regulations. But, as sociologists, we propose to analyse how this figure of expert (Dumoulin, Reference Dumoulin2007) works, writes reports and produces legal evidence from technical knowledge not only in the courts, but beforehand, in their laboratories or their offices. This paper contributes thus to the understanding of both institutional frameworks and routine practices by juxtaposing two distant fields and comparing them in dual scales of the institutional framework (macro) and empirical practices of experts (micro). In order to consider the role of the institutional framework in which expertise is to take place, this paper focuses particularly on the relations between judge and expert in the French institutional model (Leclerc, Reference Leclerc2005). A careful examination of the practices attached to this model of regulation in which experts are mainly appointed by the judiciary will feed current debates in the US, where some have suggested alleviating the connection between experts and the parties. Beyond that, it is the more general question of the hybridisation of legal models that is raised here – the empirical examination of the question of the appointment of the expert by the judge and its effects on the making and use of the expertise. We first illustrate the strength of the institutional and legal framework by focusing on two seemingly very different fields of expertise – legal medicine and economics – in order to show that, beyond differences in the nature of the subject matter, the ways of demonstrating expertise are similar due to a common institutional framework. In other words, and this is absolutely not obvious in our opinion, from the point of view of the consequences of the legal framework on concrete practice and on expert reasoning methods, the French forensic accountant is closer to the French forensic doctor than to the US forensic accountant. A second theoretical as well as empirical contribution emerges from our attempt to open the black box of judicial expertise, which closes controversies and renders invisible the choices made in technical activities (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff1997). In this regard, we have put together a set of original material that provides a large part of the experts’ practices, so that we do not have to stop studying the expert reports once they are completed. This perspective on expertise in action (Jasanoff and Leclerc, Reference Jasanoff and Leclerc2013) makes it possible to study practices of producing legal evidence in these two very different specialties, before trials and in their daily activities, which are technical activities but governed by the law and the judicial horizon. While seeking to open the black box of expertise, in the footsteps of American Science and Technology Studies (STS) researchers (Lynch, Cole, Jasanoff, etc.), we therefore propose to insist on the institutional dimension of these expertise practices in order to fully understand the French case.

In order to articulate these two perspectives on expertise captured both as a set of practices and as an institutional model of the expert/judge relationship, this paper presents the results of two research studies that implemented this approach to expertise in action through different methodologies. What both studies have in common is that they offer stories of expertise, whether they be action sequences glimpsed through ethnography, texts produced in expert assessments or narratives delivered in interviews. Because this is a comparative analysis, we begin by justifying this comparison, which provides a good starting point for describing the methods of our two fieldwork studies (Section 2). We show that, in the French model, where the judge has a much more central role, experts are quite dependent on the judge to obtain information about the case in which they are involved (Section 3). In the US, experts are torn between the litigant's best interests and the universality of science that they are supposed to represent. In France, experts are torn between remaining within their remit or overstepping it (Section 4). After analysing the ambivalence of the expert's autonomy in this French ‘judge as expert’ model, we discuss the kinds of issues that recent changes in judicial expertise in the US are likely to raise (Section 5).

2 Why a comparison? Comparative methodology and data

By highlighting two areas of expertise in France – forensic pathology and economic legal expertise – this paper aims at examining in depth the French model of expertise in its diversity, taking into account different technical and scientific specialties, as various legal procedures grounded on criminal, civil or administrative law.

2.1 The French model of expertise

In the French legal context, the expert is appointed by the judge and the legal procedures are inscribed in a Civil Code, not common law. As such, there is less need to question the admissibility of evidence in each case, notably because the role of the expert is more institutionalised in France. This paper seeks to understand the specific methods common to both fields of expertise – here forensic pathology and economic expertise – on which professionals base their actions in a legal context. In the French institutional framework, these two expert activities are regulated by identical legal texts, subjected to a code of ethics and legal procedures that are a priori identical (Leclerc, Reference Leclerc2005; Moussa, Reference Moussa2015). They are legal operators who are appointed by officers of the court and whose role is to shed technical light on the facts so as to enable these court officers to establish the legal truth, reflected in their decisions. The Criminal, Civil and Administrative Procedure Codes define how, by whom and for what occasions experts are appointed, as well as what they are expected to produce and how the ‘evidence’ and technical explanations should be brought to the judge's attention (Vergès, Vial and Leclerc, Reference Vergès, Vial and Leclerc2015). Finally, judges designate experts through a list in each of the thirty-five appellate courts in France – a list that the judges built every year and on which experts who are accepted stay for five years before to have to ask again to be inscribed on it (see Dumoulin, Reference Dumoulin2007 and Pélisse et al., Reference Pélisse2012 on the procedure based on merits and more and more on special training to ensure competence and quality of the experts enlisted by the judges). The French system thus differs specifically from other national judicial systems in placing expertise within the judge's purview. The expert is situated above either litigant and is deemed fit to conduct cross-examinations, whether to settle economic disputes between litigants or to evaluate bodies and corpses. Expertise must be impartial – it cannot be provided in order to support either judicial argument (particularly in terms of liability) – and the light that it is expected to shed on the facts is meant to constitute legal evidence. This impartiality is, in part, guaranteed by the fact that legal experts are tasked by the judge rather than either litigant. This statute partially relieves legal experts in the French system of having to prove how and by which methodology they come to reach their conclusions. For American legal experts, justifying the methodology and process used to reach their conclusions is a central point of their reports (Lynch, Reference Lynch1998; Lynch and Cole, Reference Lynch and Cole2005). The French system's positioning of the expert within the judge's domain therefore enables the creation of a ‘black box’ (Lynch, Reference Lynch and Jasanoff1998), as it makes the expert into what Renaud Dulong (Reference Dulong1997) called an ‘operator of factuality’, meaning that the factual nature of expertise reports is guaranteed without experts having to justify what they say on every occasion.

Our fieldwork on these two areas of expertise has taught us that the French model has several variations, which we illustrate below. This paper presents two contrasting case-studies, highlighting the heterogeneity of the French model so as to elucidate the multiple conceptualisations of expertise. Moreover, our theoretical argument is strengthened by the institutional logics perspective (Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury, Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) according to which institutional frameworks constitute a major dimension that should be taken into account to understand, here, how evidence and proof are built by experts in judicial activities – even in such contrasting cases as forensic pathology and economic expertise.Footnote 1

2.2 The scalpel and the calculator: two contrasting cases

We compare here two specialties of expertise whose association may seem incongruous. They are nevertheless commonly required in the courts and rarely analysed (see nevertheless the historical study of forensic pathologists erected as the basis of the French judicial expertise by Dumoulin, Reference Dumoulin1999; Chauvaud, Reference Chauvaud2000; Porret, Reference Porret2008), unlike social science-based expertise (Socio, 2014) or other specialties, like DNA (Renard, Reference Renard2011; Lynch, Reference Lynch2013) or psychiatry (Protais, Reference Protais2016). We nevertheless do not compare pathologists and economists in a sociology of profession perspective (Pélisse et al., Reference Pélisse2012) or by centring us on their ‘expert capital’, as proposed by Stambolis-Ruhstorfer (Reference Stambolis-Ruhstorfer2018), who analyses opposing same-sex-marriage experts in France and the US. Finally, our starting point for proposing this comparison is rooted in the description of their practices and, in particular, in the words of an economist judicial expert who, in a way, aroused our curiosity and led us to imagine pooling two separate investigations, but whose rapprochement seemed heuristic to analyse the French expertise at new costs. Indeed, as this expert in accounting and finance management says:

‘the expert by definition does not work in the immediate, he does not work in the prospective – he works almost exclusively in the retrospective: things are fixed. I used to say that forensic examination looks very much like forensic pathologist: the patient does not move.’

If the retrospective dimension of forensic expertise – whether economists, pathologists or other specialties – is inherent in the fact that this knowledge is mobilised in the framework of trials, aiming at judging past events, and beyond the good word of the expert in economy comparing himself to a forensic pathologist, analysing together these two specialties constitutes a strategy for contrasting two cases probably among the most opposed, as the description of the research on which this comparison is based allows to underline. Two pieces of research are therefore the source of this paper.

The first study focuses on economic experts and was set up as a collective project seeking to compare different specialisations of ‘forensic expert witnesses’ (Pélisse et al., Reference Pélisse2012). It was conducted between 2008 and 2011 on a sample (n = 145) of forensic economic experts through in-depth questionnaires (written surveys), with a subsample (n = 19) participating in oral interviews (Charrier and Pélisse, Reference Charrier and Pélisse2012). The initial body of work was expanded through a subsequent and ongoing exchange of narratives and reflections between Y and an economic expert, who became a very useful informant on the practices and evolution of this activity. Because of his biography and current activity (he was trained in law, then in accounting and is now teaching part-time in a postgraduate training programme), the reflexivity of this expert's contribution has offered a particularly interesting point of view for analysing the practical reasoning and activities of expertise. Finally, the author supplemented this study with an analysis of past and current expertise cases in economics in 2016.

Meanwhile, Romain Juston Morival, the first author of this paper, defended a thesis on forensic pathologists, working on ‘how does a bloodstain become evidence?’ (Juston, Reference Juston2016) and publishing his dissertation in 2020 (Juston Morival, Reference Juston Morival2020). The research builds on the implementation of an empirical investigation system, combining ethnographic observations, interviews and documentation. Different locations were analysed (autopsy rooms, doctors’ offices, government agencies, public prosecutors’ committee rooms). This paper deals mostly with the practices of experts and prosecutors’ departments, within the organisations in which the medico-legal expert assessments are produced and used – from hospitals to courts of law. Finally, Romain conducted in-depth investigations of five medical departments, spent fifty days with forensic pathologists and medical examiners, and conducted seventy interviews with them. On the judicial side, Romain spent eight days observing a public prosecutor's department and observed ten trial sequences in which experts delivered oral presentations of their reports to the courtroom.

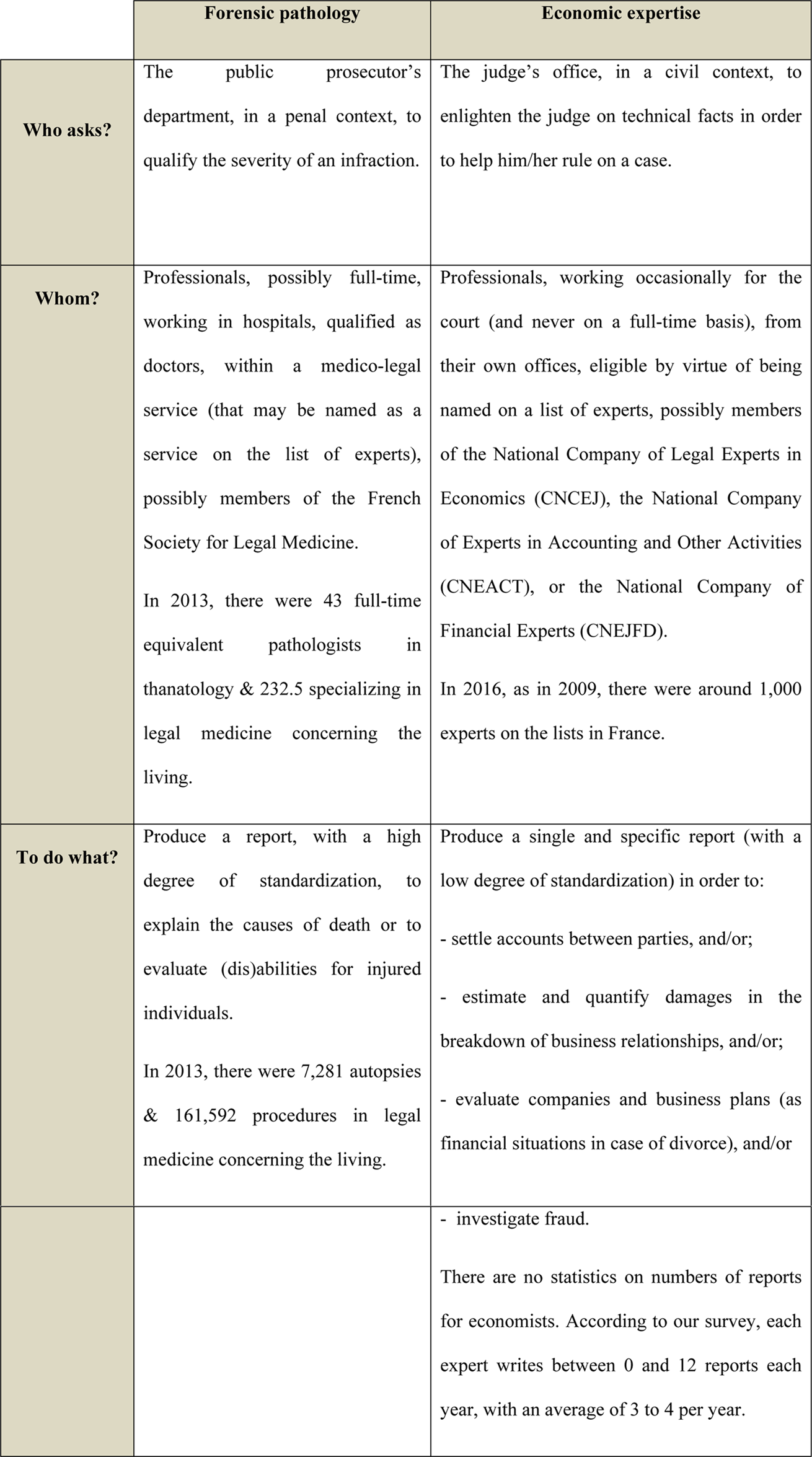

This paper argues that being a ‘judge's expert’ implies a certain way of providing expertise and producing legal evidence, despite its application to very different specialties and activities. By testing this hypothesis for the most contrasting specialties of expertise, we focus on the framework of court-appointed expertise as the thread that unites them. The chart in Figure 1 details the most significant differences between forensic pathology and economics expertise – differences and contrasts such that they justify our comparison.

Figure 1. Differences between forensic pathology and economic expertise in France.

There are fundamental differences between forensic medicine and economic expertise, including in such areas as guidance, legal procedure, what judges expect from each kind of expert and even the professional and socio-demographic characteristics of each of these experts (see Pélisse et al., Reference Pélisse2012; Juston Morival, Reference Juston Morival2020). Despite their common status as officers of the court, strong contrasts exist between judicial economists and forensic pathologists. Moreover, they have different relationships with judges, lawyers and litigants – or even other actors such as dead bodies. But our approach, by focusing less on external social factors (like socio-demographic characteristics or the more or less cohesive milieu that experts build notably through professional associations) and more on the role of institutional dimensions – and particularly the fact that they are judges’ experts – proposes to analyse relationally and internally their practices as embedded in institutional frameworks. From this perspective, despite their differences, when looking more closely at how they construct judicial evidence, we observe both kinds of experts as legal intermediaries insofar as they help the judge as officers of the court. In other words, one can see these two kinds of experts as individuals who, though not legal professionals, handle the law on a daily basis, have their activities driven by a judicial perspective and, as a result, position themselves as intermediaries or mediators between law and science – between justice and technical methods (Stryker, Reference Stryker, Bessy, Delpeuch and Pélisse2011; Talesh and Pélisse, Reference Talesh and Pélisse2019). Like other legal intermediaries often located further away from the legal field, such as human-resources managers, trade-union representatives, industrial-organisational psychologists, safety engineers or street bureaucrats, legal experts – who define themselves more as court officers than legal intermediaries, a recent analytical category developed by sociologists (Pélisse, Reference Pélisse2019) – use their technical knowledge and professional logic to hybridise the way in which the law is implemented in action by the fact that they are called upon by the judge to help them make a decision based on ‘the facts’ and how their technical or scientific knowledge illuminates these ‘facts’.

Nevertheless, because experts are in France appointed by judges, from whom it derives its institutional legitimacy, they do not need to demonstrate their impartiality every time they present a report. They do not have to open the black box of expertise as the American expert must systematically do, or very rarely during counter-expertises, which are totally exceptional. This does not mean that they cannot be contested by the parties, for example when they may encounter questions or challenges by lawyers or other experts for accountants, but this is mostly during the expert meeting, in private space and time, and experts have always the authority of the judge to legitimate their choices and ways of conducting expertise. But this appointment and legitimacy given by the judge have a cost: there is a need to not recognise that the line between law and technique – between legal reasoning and technical facts – is blurred and that the judicial perspective influences technical practices used to demonstrate and provide proof. In the US, this blurring is recognised, explicit and intrinsic to legal experts’ intermediate position between litigants and the judge. By having to open the black box of their expertise during the trial, experts show and imply that they mix legal and technical arguments to prove and demonstrate in favour of their clients (Lynch and Jasanoff, Reference Lynch1998; Lynch and Cole, Reference Lynch and Cole2005). In France, this blurring is not quite recognised – moreover, it is not authorised: experts must stick to the technical, to narratives based on the ‘facts’ without commenting on the legal dimension of these ‘facts’ and narratives. To open analytically the specific black box of French expertise allows the way in which the judicial perspective and the law influence technical practices used to demonstrate and provide proof to be shown, as we will now see. In other words, if French law organises an apparent ‘black box’ of expertise, contrary to the American institutional framework that leaves it more transparent, we assert that many controversies and choices arise in the course of French expertise practices, not only because the experts’ statements are always liable to be challenged by the opposing party, but also by the way in which expertise is made, evidence is produced and reports are written.

3 The expert and the law: how does the judicial perspective influence technical practices?

We thus focus on the practices of experts in order to open the black box of expertise and to test the approach to the encounter of science and law. STS references are useful for opening the black box of expertise and supporting the conceptual framework of co-production developed by Sheila Jasanoff (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff1997; Reference Jasanoff1998; Jasanoff and Leclerc, Reference Jasanoff and Leclerc2013; Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2006). These works have shown how legal expertise is co-produced by science and law. However, our work considers the situation not only from an STS point of view, but also from a socio-legal point of view, as M. Lynch has explicitly proposed (Lynch, Reference Lynch2008, notably pp. 14–22). Moreover, we analyse the practices of legal experts not only in the court or during their judicial performance at the bar, but beforehand, during the process and preparation of their reports. Finally, we show how the judicial perspective penetrates into the practices of legal experts not only in the US, as established by this literature, but also in France – that is to say, even in the case of court-appointed experts, in an institutional and legal framework very different from the US context.

3.1 Forensic pathologists: the intermediation of law in the translation of the body into a judicial fact

In order to proceed with an autopsy, an expert must become involved with the case and cannot work without context. On the contrary, experts need information resulting from the investigation to guide their expertise, and this information is assembled in a form that looks like a story. This narrative, which begins in the laboratory, has everything to do with the law. Experts cannot just observe and record – they are involved in the narrative either by relying on it or by producing it. The storytelling approach promoted by Jean-Marc Weller (Reference Weller2011)Footnote 2 is very useful in identifying the terms and rules of the cohabitation between the law and the laboratory. This storytelling process, which is explicitly developed by the expert as a mixture of information emanating from the judicial context and facts related to the scientific activity, has proven, in observations, to be necessary to the success of the expert testimony, as the following specific case illustrates.

The ethnographic material presented below falls under what Anselm Strauss would call a ‘case of the year’ because of its extraordinary aspects. It highlights the need for judicial ingredients of expertise and the fact that the narrative is produced by both investigators and experts. This case concerns the autopsy of a man found hanged in his garden; a few metres away, a gun lies on a branch; inside the house, the man's wife is found dead, killed by seventeen blows from an axe. It is a ‘case of the year’ because there are two victims and three possible causes of death: a rope, an axe and a gun.

Before the autopsy, the investigators reveal crucial narrative elements – notably, a letter in which the man explains that he killed his wife before ending his own life. But the smoking gun found in the garden does not fit the story, so the forensic expert invites ballistic experts to attend the autopsy and give their opinions on the firearm. The autopsy starts in a room full of forensic experts and investigators working on the case. The information produced by the investigators directs the forensic examination to the rope marks in order to assess whether the rope is the cause of death. However, if this forensic examination confirms the police narrative, other forensic descriptions call it into question. A gunshot wound is found on the temporal lobe of the victim. It is assumed that the wound was made by the gun found at the crime scene, yet the distance between the body and the location of the gun at the crime scene is problematic. The autopsy takes a very enigmatic turn. When the sociologist asks the police officer if the man really hanged himself, she says: ‘I hope so, my entire case is built on it.’ The forensic experts are faced with one body and two causes of death, both equally plausible but incompatible. This leads to interpretations based on the additional scientific material and the intervention of a third party. The discussion continues with forensic experts providing scientific descriptions and investigators producing a narrative that would be consistent with the descriptions. Forensics and investigators have to mix their respective registers in order to tell a story that works. This case allows us to question the opposition between narration and description, as the description of the forensic examiner is first based on the narrative elements and then rectifies the narrative. In the end, after the intervention of the ballistic experts, the diagnosis differs from both from the investigators’ story and the forensic pathologist's purely scientific account. The man, having murdered his wife, tried to kill himself with an antique firearm. ‘It is amazing it even fired,’ remarks the ballistic expert. They surmise that the man lost consciousness and then awoke a while later to hang himself from a tree after putting the firearm on a branch.

To sum up, if the final output is both a scientific report detailing wounds and an investigative report that provides an interpretation of them, the autopsy aims to reconstruct the story. The autopsy first relies on the preliminary narrative elements and then amends them by implementing scientific techniques. This case highlights the part played by narrative elements in the conduct of an autopsy – they are necessary for investigating the causes of death, and ultimately for solving the case. We could even say that law's entrance into the laboratory, or the use of narrative elements in the conduct of an autopsy, is necessary for science to enter the court, as it helps to provide comprehensible material that meets judges’ needs. Forensic pathologists, like economic experts, are legal intermediaries precisely because they perform their activities on material of a highly judicial nature, which they need to both express a scientific point of view about and translate it for laypersons who do not have such expertise (police officers, judges, sociologists) (Collins and Evans, Reference Collins and Evans2006). This need for narrative is equally important for economic experts, who use legal categories on a daily basis to build their technical point of view and provide evidence for judges.

3.2 Economic expertise: a continuous mix of legal and economic, accounting or financial reasoning

In economics, the modes of reasoning and the technical activities based on accounting, numbers and finance are crossed in the same way by judicial and legal dimensions. As the expert comparing his activity with forensic pathologist explained (see above), if an economic expert discovers new facts – like the pathologist whose scalpel may discover an unknown tumour – and also needs the information collected in the context of legal proceedings to interpret them, he ‘must place the accounting facts in the regulatory, legal, and customs contexts of the time of their occurrence’. He adds:

‘In economic terms, we work on accounts that date back many years, and we must take care to bring in the texts and case law applicable at the time. While a case law may have modified the former two or three years later, we have to give it to the judge, if necessary, without any appreciation of the law, because we do not have the right to do so. We have to say, “Maybe this provision…” We do it in our file but we do not necessarily write it down because the litigants and lawyers can blame us for recording legal appreciations, so we distinguish between the assessment and the communication – they are two totally different things.’

‘[Bringing] in the texts’ is what we aim to analyse as the approach used by the experts to mitigate and mutually constitute their technical activity and daily use of law and legal regulations. In this sense, not only can the patient (the company, the CEO, the business relationship) still move, but these experts constantly approach, monitor and work on the boundaries between what is economic, accounting or financial and what constitutes ‘the legal assessment’. The need to describe economic relationships and accounting facts irreducibly implies a legal framework that provides categories, concepts and procedures.Footnote 3 Experts perform a work of ‘settling’ and ‘filtering’ (a work of ‘decantation’, as with wine, to borrow one expert's term) with convening litigants, meeting deadlines, compiling claims and ultimately telling the story leading to such and such damage quantifiable in such and such amount or quantifying the accounts between parties. The expert gradually separates and eliminates the different alternatives that result from the different ways of qualifying the facts and establishes logical evidence that takes the form of a coherent narrative to ultimately offer two or three possible amounts – and no more – in a report sent to the judge (Charrier and Pélisse, Reference Charrier and Pélisse2012).

In one case, for example, two building companies working together alternately as prime contractor and subcontractor are in dispute. Company A demands payment of invoices, while B claims that these are offset by its own claims concerning other sites. Before ruling, the court appoints a chartered accountant with the express task of ‘settling the accounts between the parties’. The expert convenes a forensic meeting and requests the invoices of both companies concerning the disputed construction sites. The accountant from A cannot provide all the invoices that were claimed to have been left unpaid. The expert points out that he must have a paper trail and consequently reduces A's claims. The accounts from B, on the other hand, clearly identify the amounts it claims. Company A subsequently reports that the court had previously appointed an expert to assess the construction work done by A for B on the disputed site. Taking stock of the report delivered by this second expert, the forensic accountant notes that the court had rejected any additional charges due to a number of deficiencies of B on the said construction site. The expert notes that B had not challenged the first expert's observations concerning these deficiencies. He thus concludes by reducing B's balance to what he considers was implicitly agreed after the first expert's report. His very brief report notes the reluctance of both litigants to submit the necessary documentation in full and the expert's forensic procedure. The report concludes in favour of A, though the net balance is slightly lower than A's original claims.

By contrast, a second case shows how the judge expects such a narrative and does not expect to have to make many choices after reading the report. An expert told us the story of one of his colleagues who had built an impressive array including all possible hypotheses arising from the various ways of legally qualifying the facts, each leading to an amount. The case concerned cancelled insurance contracts with different possible reasons for cancellation, each contributing to different calculations for the parties. However, the judge, as the story was reported to us, expressed his dissatisfaction when he read the pre-report and, after choosing one of the columns in the table, asked the expert to redo his work to indicate only the path that led to the chosen amount. In other words, the judge asked the expert to construct a narrative to support a chosen hypothesis, insofar as he waited a clear result, helping him to take a decision without having to explore all the hypotheses produced by the expert.

The case of forensic medicine, on the other hand, allowed us to consider how the forensic pathologist also fabricates a narrative, although in a different way from that of the forensic accountant, which is not regulated by the same institutional framework. Indeed, the forensic pathologist is not framed by an adversarial frame like the accountant in civil-case procedures, but the medical examiner is also developing a narrative. The difference is that he anticipates the reactions of the judge rather than those of the parties. Nevertheless, behind these procedural differences, our approach to expertise in action has identified a common requirement for these two specialties of expertise to assemble technical and narrative elements. Furthermore, they permanently base their expertise on qualifications and judgment, categories and rules – that is, procedures and law, present at all the technical stages as much as a horizon guiding the way in which the expert will write his report.

3.3 The scalpel and the calculator: tools between technical evidence and legal narration

The legal narrativist approach illuminates the activity of producing evidence in a judicial context for both types of expertise (Weller, Reference Weller2011; Jackson, Reference Jackson1988). From this perspective, the expert's production of proof could be described as the use of tools, like a scalpel or a calculator, to align a story (elaborated on by the expert after assessing the narratives proposed by litigants or police officers), documents (as in accounting documents or medical reports) and legal rules, creating a description of situations that is in turn used to qualify and to (be) interpret(ed). Experts assemble thus figures, facts, opinions and proposals to create additional resources aimed at explaining reality and establishing evidence, with can be useful in the search for truth and the judicial decision. In this sense, they could play a role of the first, small or technical judge.

In the US, where the expert is on the side of the litigants, there seems to be no room for the expert to take the place of the judge. But recent reforms and projects ushering the US towards a system in which the expert can be appointed by the judge open up new questions to which we can begin to seek answers from the French system. For both economists and forensic pathologists, the fear that their reports would lead them to take the place of the judge gives rise to a constraint about which experts are very careful, and which has consequences on how evidence is provided in a judicial context. We will now examine the consequences of this institutional framework on the expert's position.

4 Remain within one's remit or overstep? The practices of medical and economic experts when facing judges and litigants

The judicial framework for legal expertise in France is based on a distribution of tasks in which legal experts’ activities are restricted to the technical aspects of their tasks. ‘Scientific matters and the choice of methods and protocols fall to experts, the mastering of legal aspects and the sense of case expertise fall to magistrates’ (Dumoulin, Reference Dumoulin2007, p. 151, translated by the authors). Therefore, the experts should demonstrate their allegiance to the judicial authority by ‘remaining within their remit’. In practice, however, they frequently ‘overstep’Footnote 4 the rigid position of spokesperson for a technical area that only they master and venture into the field of law or into considerations of the legal consequences of their technical propositions.

4.1 Overstepping by forensic pathologists

We present here a case in which the magistrate has been building a rapport with the medical expert even before having ordered a report and thus the expert's task has yet to be formalised. This situation is actually quite common and is clear evidence of the ambivalence that weighs on the doctor/magistrate relationship, as magistrates have expectations that often exceed the strict role of the ‘expert’. Indeed, judges often delegate decisions pertaining to the judicial classification of facts and these decisions affect the choice of legal procedure to be implemented. As such, when asked to outline the purpose of the forensic pathologist's task, or even to start a judicial procedure, judges do not consider the forensic pathologist a simple clerk; they both work at the same level and for the same goal: the judicial process.

In the following case, Romain witnessed a telephone conversation between a magistrate and a forensic scientist regarding an autopsy. Although the request for an autopsy fulfilled procedural requirements, the forensic pathologist encouraged the magistrate to cancel the autopsy. On the phone, the magistrate wished to get more information from the medical examiner about a death investigation that had just been launched by a colleague at the public prosecutor's office:

‘I will give you an oral account. A 64-year-old man was trimming a tree. He gives the chainsaw to his daughter, who's with a friend. When she comes back, he falls from two meters off the ground, onto a pile of leaves. They call an ambulance. The old man seemed to be breathing, but his breathing stops. The man dies. They look for something at the cervical vertebra – the most probable cause of death from such a fall – but nothing comes up. No fracture of any kind that can explain the death. I told the judicial police officer. They conduct another round of interviews, because he tells me he had no health problems. During the external examination they note that he's slightly overweight; they interview the family again, and apparently he had trouble sleeping, chikungunya, tiredness with some pain and itchiness on his left arm. Yeah. I checked if there were any issues at the cervical vertebra, nothing; however, I noticed lesions that shrink the coronary artery and cause infarctions. When they're that significant, they're very noticeable. So he was clearly a man who had cardiovascular issues he wasn't aware of, where he was exerting himself without breathing – forcing it, so to speak. So I agree he fell accidentally, but it's not the fall that killed him. It's a medical thing. The judicial police officer didn't mention a thing. To me, it has to be a medical thing, although the fall was concomitant. But he tells me there was a witness. I say this to really get to the bottom of things. When addressing the family, I'd approach it on a medical basis.’

The medical examiner then talks to the magistrate. She does not ask him to conduct an autopsy: ‘How are you settling in? When did you arrive? Where from? It's very formative here! [laughter]. Good luck. I shouldn't plan on reserving the autopsy room, right?’

Once a death is established, the prosecutor's department starts an investigation into the death, where medico-legal observations and police inquiries are initiated. At this stage, it is the doctor who informs the magistrate about the case. It is thus not uncommon, as in this case, for the expert to know more than the judge because he or she has a more accurate picture of the various legal or medical investigations conducted. This case is also notable because it shows that the expert has a better understanding of the region – the second most crime-prone in France – than the young, freshly instated magistrate and he does not shy away from telling her this moments before she says there will be no autopsy. The doctor thus goes beyond the standardised report and comments on the investigation itself in order to validate his theory of the accident. He advises against conducting an autopsy, even though the mystery of the man who died from a fall without any damage to his cervical vertebra remains intact. In short, to the doctor's knowledge, this is not a criminal case, but an ‘accidental thing’ that he then refers to as a ‘medical thing’ – something that does not require an autopsy. In other words, in his capacity as a medical expert, he is not interested at this stage in determining the medical nature of the issue, which he confirmed after the phone call documented above.

In conversation with Romain, the medical examiner recognised that he ‘may have pushed the advice on the judge a little too much’, especially given the fact that they had effectively brought the legal proceedings to a close, since the medico-legal obstacle had been lifted. The body was given back to the family without an autopsy. That said, he explained that he had based his reasoning on the suspicious/non-suspicious dichotomy of the nature of death, where most pathologists would have emphasised the determined/undetermined dichotomy. Setting aside his scientist's hat – a role driven by the scientific explanation of death – and taking on the role of the expert conscious of practical judicial considerations, the doctor moulds himself into what he believes a good expert to be and, as such, shifts the determining factor for allowing an autopsy to the suspicious/non-suspicious nature of the case. This choice is therefore much more justifiable from the perspective of the judiciary, as it takes care not to burden the legal procedure with an autopsy in the event of a natural death, than it is from the medical perspective, which is more interested in the nature of the death. In engaging in legal dichotomy (suspicious/non-suspicious) to the detriment of the scientific dichotomy (determined/undetermined), this pathologist goes beyond his technical role to inform the measures to be taken by the prosecutor. Where most medical pathologists seek to conduct scientific test after scientific test, this medical examiner explains that his goal with the magistrate is to not be ‘that annoying guy’ who always wants to do everything. In other words, he does not consider his action to be an overstepping of his role, but rather considers it part of what is expected of a good expert – to be the kind of intermediary who qualifies legal procedures before they actually begin, acting as more than just a ‘helper’ who merely adds one piece of technical information to the legal puzzle. This case is specific when considering the position of the parties – the inexperienced judge and the seasoned medical pathologist – but it showcases the benefits that can be reaped by the judge and the medical pathologist when the medical pathologist oversteps his or her technical role. By stepping out of the purely scientific sphere, the medical pathologist becomes a central actor in shaping law.

4.2 The constantly debated position of economic experts

For experts in economics, overstepping often takes the form of controversies and discussions concerning the ways in which they play their role or exercise their authority – while providing expertise – that position them above the judge. This is notably the view of those who denounce these misbehaviours, which are always a risk in expertise. The lawyers of each litigant monitor the actions, arguments and written reports of legal experts, sometimes very closely. Finally, the increasingly frequent presence of forensic counsel – that is to say, experts appointed by litigants and not the judges (Hubert and Charrier, Reference Hubert and Charrier2015) – helps to challenge forensic economists (appointed by the judge) and particularly encourages them to not overstep, but rather to strictly respect, their role as purely technical experts.

In one case, for example, the forensic counsel tried to ‘put the court expert in his place’, from which he had strayed by refusing to consider one possible way of exploring an accounting problem that had caused the dispute between two litigants. A chef's scooter accident led to a major shift in his career and he disputed the action taken by his insurer to offset the consequences of this accident. As the owner of several restaurants, the chef emphasised how his absence for months caused all of these restaurants to lose their reputation, although he himself worked in only one of them. The insurance company wished to remunerate only the losses at this restaurant, stating that he did not cook in the other two restaurants that he owned. The judicial expert appointed by the judge ignored this argument and focused, according to our informant, on an assessment of loss based purely on historical accounting from the three restaurants (extrapolated losses based on an average of the last three years plus inflation), refusing to examine the thesis of the expert counselling the chef. The forensic counsel proposed indeed to use the indicators measuring the development of one business in a specific market (restaurants with one Michelin star in Paris) to construct a growth curve significantly above inflation. This opposed a numerical approach with an approach of economic substance, attacking the court expert in the technical arena and criticising his accounting and narrow vision in favour of an analysis of the entrepreneurship and differentiation mechanisms that lead some companies to success. The forensic counsel thus criticised the refusal of the judicial expert to examine the alternative proposal, for which his only justification was to say that he was the expert appointed by the judge and thus was the one to make such decisions. In the view of the forensic counsel, by refusing to consider the elements of contradictory evidence, the judicial expert left his own role and position to take the place of the judge. The counsel thus sent a letter to the judicial expert regarding his position, stating that the next step was to write to the judge, which was a last resort that he would prefer to avoid.

This case demonstrates how a question may be posed about expert reasoning and evidence when forensic counsels confront the judge's experts, who must then explain their methods and move beyond their institutional authority to manage their expertise. As Vergès, Vial and Leclerc (Reference Vergès, Vial and Leclerc2015) have explained, the evidence brought by forensic counsel is the subject of a rich jurisprudence, which has certainly given forensic counsellors recognition and supported their development (particularly in economics, as indicated by Hubert and Charrier, Reference Hubert and Charrier2015), but has also diminished their probative force. After conflicting decisions in different divisions of the French Supreme Court (Cour de Cassation), a mixed chamber decided in September 2012 not to allow judges to rely solely on evidence from forensic counsel as the basis for their judgment. This ‘unfinished building’ – between freedom of proof and respect for the adversarial principle, which requires evidence to be combined with other elements to found the judge's decision – ‘reluctantly leaves a place for forensic counsel and disrupts the boundaries between free proof and legal proof’ (Vergès et al., Reference Vergès, Vial and Leclerc2015, p. 628, translated by the authors).

These decisions show a contrario how legal proof is considered when it is provided by a judicial expert appointed by the judge to be independent, impartial and objective. Even if the judicial expert does not necessarily have to open the black box of expertise by describing his/her method or proving his/her assertions – as in a common-law context – he or she must nonetheless comply with legal procedural rules of expertise, which are substantial in framing the practice of technical expertise. The adversarial principle that the legal system has gradually but systematically imposed in all stages of expertise in France – at least in civil matters (but also, increasingly, in criminal procedures) – is now integrated as a practical rule that profoundly transforms the practical exercise of expertise. In a sense, and notably thanks to these decisions, which illustrate the growing place of adversarial principle, and the more and more systematic presence of forensic counsel during the stage of legal expertise, the French system is moving closer to the US model of expertise (in addition to the US, which is moving closer to French).

4.3 The scalpel, the calculator and the judge

Judges generally expect clear opinions and conclusions that allow them to make decisions rather than simple factual analysis, which does not provide this help (as in the case of the expert who gave multiple quantifications reported above or, in the pathology case, where the judge was much more interested in the legal dichotomy than the scientific one). The call to remain within one's remit is also visible in the laboratories of forensic pathologists and is not unlike the principle of ‘jury usurpation’ that Lynch, McNally and Dupret (Reference Lynch, McNally and Dupret2005, p. 673) found in their case-study that shows how ‘scientific’ evidence (here DNA) and the evidence of ‘common sense’ are redefined in practice.

But it is not just in exceptional cases such as the one analysed by Lynch and McNally that we can identify how actors come to regularly discuss the boundaries of what can or cannot be said by experts, and thus discuss the expert's place and limits when carrying out tasks ordered by a judge and producing – or not producing – acceptable evidence. Indeed, we may also observe this in routine expertise, as reported earlier in this paper concerning economics and forensic pathology. The fact remains that, through controversies and debates over these boundaries, which are more or less explicitly re-enacted in each case, some definitions are fixed, some possible roles for experts are made precise and other behaviours and techniques are disallowed. These conventions are built routinely in the course of action and practices, but they also can result from decisions of high courts when debates are submitted to them, as in the case of evidence from forensic counsels.

5 Discussion

For both forensic economists and pathologists, overstepping is quite common, even in the French system, where the division between legal activity and technical activity is very clear in the law books and is formally required to be so during the expertise process, though it is actually quite blurred during experts’ activities. In the US, the boundary between what is legal and what is scientific is also a very hot topic, even if it has played out otherwise, notably since (and through) the famous Daubert case and then the Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael case (Munagorri, Reference Encinas de Munagorri1999; Leclerc, Reference Leclerc2005).Footnote 5 With these decisions, American judges have taken responsibility for accepting or rejecting proof delivered by experts, imposing the need for these experts to more and truly open the black box of their activities and to justify their methodologies, to explain how and why they use certain types of data. It is also a way for experts to show their technical reasoning, which has to be based on published, tested and shared references. This greatly contrasts with the French system, but we aim to highlight other developments in the American framework of judicial expertise. Indeed, we can base our discussion about the French expertise model not to show how it is different from the US model (see Hubert and Charrier, Reference Hubert and Charrier2015 in the domain of accounting), but to highlight some of its specific attributes that could become characteristics of the US model in the future or that are already at this very moment in debates about the expert's status in the US. As stated in the introduction, some changes have been made to this US legal framework – notably to increase the neutrality and independence of experts. These changes involve a new mode of regulation of relations between experts and judges, much closer to the model of the expertise of the judge questioned here in the French case. Let us discuss our paper to conclude, from the evolving perspective of both forensic medicine and accounting in the US.

5.1 Speaking for the dead, speaking for the judge: the transformation of the institutional frame of forensic pathology

In the US, ‘suspicious deaths fall under the jurisdiction of a forensic death investigator charged with determining the identity of the deceased and the cause and manner of death’ (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2006, Preface, p. viii). The term medico-legal death investigation is ‘an umbrella term for a patchwork of highly varied state and local systems for investigating deaths’ (Hanzlick, Reference Hanzlick2003, p. 7).Footnote 6 The first characteristic of the US model is that we find both coroners and medical examiners. Coroners are usually elected and usually not physicians. Medico-legal death investigation is governed by state law:

‘There are broad differences between medical examiners and coroners in training and skills and in the configuration of state and local organizations that support them. Medical examiners are physicians, pathologists, or forensic pathologists with jurisdiction over a county, district, or state. They bring medical expertise to the evaluation of the medical history and physical examination of the deceased. A coroner is an elected or appointed official who usually serves a single county and often is not required to be a physician or to have medical training.’ (Hanzlick, Reference Hanzlick2003, p. 7)

It would be no small matter for the US to replace coroners with medical examiners. In 2006,

‘Approximately, half the U.S. population is served by coroner systems and the other half by medical examiners. Regardless of who runs the system, most death investigations are handled at the county level. Approximately 2,185 death investigation jurisdictions are spread across the nation's 3,137 counties.’ (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2006, p. 9)Footnote 7

In his report on medico-legal death-investigation systems, Randy Hanzlick (Reference Hanzlick2003) defends a statewide medical-examiner system. According to him, the advantages of such a model ‘are the quality of death investigations and forensic pathology services and their independence from population size, county budget variation, and politics’ (Hanzlick, Reference Hanzlick2003, p. 23). The proposition to replace coroners with medical examiners presents a new vision of expertise that should be considered separately from the adversarial logic of trials. Hanzlick tries to envision a system that is ‘structured to produce objective evidence that will not produce such battles [of experts]’. The defenders of a statewide medical-examiner system base their opinions on the idea of objective expertise where ‘there should be no differences between the defence perspective and the prosecution perspective on scientific facts. The only medical examiner findings with potential for debate should be the manner and cause of death, because they require interpretation of facts’ (Ibid., p. 33).

There is a change taking place in those who are charged with ‘speaking for the dead’ due to a need ‘to replace the political figure of the coroner with the scientific figure of the medical examiner’ (Johnson-McGrath, Reference Johnson-McGrath1995, p. 455), but there is some opposition to such attempts from the legal profession. ‘The medical profession continually tried to have courtroom procedures and evidentiary rules changed to its advantage, attempting to privilege medical testimony over that of lay witnesses, exempt physicians from cross-examination, or circumvent the jury process altogether’ (Ibid., p. 452). This change in the American institutional framework could thus be interestingly highlighted by our analyse of the French judge's experts system in the case of forensic pathologists.

5.2 Speaking about money: current stakes between experts, forensic counsels and judges in economic litigation

For judicial experts in economics, our examination of the French system and practices is just as interesting. On the one hand, the French and American systems are growing closer and, on the other hand, the issues and debates within the American system make an examination of how the French system works all the more pertinent. As regards the former point, forensic counsellors in France are increasingly involved in the judicial process, particularly in the field of economic litigation, both because parties are seeking additional resources to establish their point of view at trial and because, as we have noted above, since 2012, judges have been required to consider elements contributed by these experts.Footnote 8 In part, these counsellors resemble the American experts because they are chosen by the litigants and face the same ethical and deontological questions as their American counterparts. Should these forensic counsellors be neutral or defend the interests of their clients at trial (Colella and Ireland, Reference Colella and Ireland1998)? How should their deontology be ensured? What is the scope of the technical evidence and reasoning that they bring – for one party – into the case? This is also a question of regulation, which is becoming increasingly important. The American ‘market’ of economic expertise thus seeks a means of regulation, which has included, among others, the multiplication of professional journals and research into this activity. The emergence of this sector in research makes it possible to identify, discuss and validate the techniques, reasoning and types of data verifying the criteria emanating from Daubert and Kumho, even if nothing is simple in a ‘soft-science’ field such as economics or a technique like accounting (Neckers and Wikander, Reference Neckers and Wikander2006). The multiplication of expert associations in accounting (more than seven exist in the US, but already three in France) and the certifications that each offers do not, however, make it possible to guarantee deontology and the quality of the judicial experts – a crucial problem related to this activity and a real concern for the professional journals in this field (Thornton and Ward, Reference Thornton, Ward, DeMartino and McCloskey2016). These experts could, however, increasingly be integrated with real professionals (Thornton and Ward, Reference Thornton and Ward1999; Shap, Reference Shap2010; Tinari, Reference Tinari2010; Hubert, Reference Hubert2012). According to Dennis Hubert, this would justify the intervention of the state or a public authority to regulate this market and activity. Should this be done, as in France, by transforming forensic counsellors into court-appointed experts?

Finally,

‘it seems that U.S. and French forensic accounting services are closer than one thinks, aren't they? Except for the fact that it is less common for U.S. courts to name experts to assist them, U.S. forensic accountants are usually named by litigants as expert witness, but must act in the interest of justice even if it could be contrary to the interest of their client.’ (Hubert and Charrier, Reference Hubert and Charrier2015, p. 109)

The French model of the judge-appointed expert could offer a way of solving this problem, instituting a decision-making model whereby, in practice, the expert is largely responsible for holding a ‘small trial’, permanently oversteps his or her remit and is not far from occupying the role of a technical judge of a pre-trial. The American model, for its part, has multiple rules, decisions and intermediary bodies to ensure that the expert is ethically aligned with the interests of justice, not just the appointing party. This system seems to have its limits, not least because the market it creates appears to be poorly regulated and, as with money, good expertise is thrown after bad; but also because the application of the Daubert and Kumho criteria is not obvious and depends on a field of research that discusses what makes good expertise in economics. This is why the French system – and the challenges it encounters at the European level, which is becoming another institutional level for the possible organisation of judicial expertise – is of interest to help us to better understand this complex technical and legal activity.

5.3 Conclusion

By focusing on the activities undertaken by experts to fulfil their tasks, this paper highlights how, even in the very different cases of forensic pathologists and economists, the activity of producing evidence for a judicial audience could be described as a transformation of technical facts (a corpse, an account between litigants or economic damages) into elements of judicial evidence (a cause of a death, a financial amount, etc.). As such, the legal division between the facts, the preserve of experts and the acts of qualifying and interpreting, which are the sole prerogative of the judge or legal officials, is not relevant to understanding judicial experts’ activity of proving and analysing facts in order to enlighten judges. Better yet, it is a matter that is continually discussed by the actors and does not represent a hard line, even if routines, experience, training, and multiple and daily acts of socialisation occur – at the lab or the office, or during interactions with legal officers or litigants – thereby shaping the practices of experts. We thus confirm many results and demonstrations from the works of other scholars, and notably the interest of the approaches developed by M. Lynch, B. Dupret and others, to better specify the singularity of this activity, which links fact and law, technical or scientific activities and the legal and judicial processes used to resolve conflicts. Law and facts are intertwined, especially along the crucial action of qualification the facts, which show how law but also ‘facts’ are socially built through the socially embedded practices of judges, experts and litigants. The second contribution of our study is to emphasise the institutional framework – and notably the judge's expert model – as essential to understanding the activities and role of the expert in the French context and beyond. The weight of this institutional framework is very high, as it frames expertise whatever the scientific domain at hand. Our result is not only that we must not underestimate it, but that procedures, legal rules and institutional framework are crucial and may be heavier than the scientific practices, technical knowledge and practical questions raised in accounting or cause of death. The French legal context – and notably the fact that the expert is appointed by the judge and is not a forensic counsel – considerably changes the weight of the institutional framework and how it should be considered when analysing these activities. It is not only ‘the position of experts in a trial – which side summons them – [that] may be a more important factor than their branch of expertise to account for certain types of these practices’, as stated by F. Brandmayer (Reference Brandmayer2016), analysing how social scientists made causal claims in court during the L'Aquila trial in Italy. In much more contrasting cases such as those involving forensic pathologists and forensic economists, the institutional position of the experts, reporting to the judge or the litigants, influences how experts carry out their tasks and their active contribution to the boundaries of what belongs to science and technique and what belongs to law and legal reasoning. Indeed, even if the adversarial principle is growing in France and Europe, in the texts and in the practices of judicial expertise, French experts have a special authority to black-box their expertise, based in their knowledge and technical competencies, but also grounded in their institutional role and the professional milieu created by their original position in the judicial system. Closing the black box of expertise within the context of the trial implies prior institutionalisation of the procedure by which the expert and the admissible technical knowledge for producing forensic evidence are chosen. The current debates of the American expertise model therefore invite us to study these new black boxes in order to understand the conversion of scientific fact into legal proof.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Robin Stryker and Susan Silbey for their comments on this paper and to Michael Lynch for his comments on a first presentation during a workshop organised by Baudouin Dupret at EHESS (Paris) in March 2016.