I. Introduction

After some fifteen years of the second era of military rule,Footnote 1 Nigeria finally returned to civil rule in 1999, upon the completion of electoral processes and the promulgation of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFRN) 1999.Footnote 2 Since that time, one of the recurrent issues besetting the Constitution has been the question of its legitimacy. The Constitution, after all, came into being through military fiat, after the work of a 25-member deliberative committee.

Beyond this questionable original legitimacy is the fact that, 22 years after its promulgation, the Constitution seems to lack derivative legitimacy as the volume of condemnation and attacks towards it has not abated.Footnote 3 This, coupled with the frequent disregard of its norms by political actorsFootnote 4 and restiveness in the polity due to dissatisfaction with the same norms,Footnote 5 makes a more incisive engagement with the issue of its legitimacy imperative if the nation is to successfully chart a worthy course out of its current constitutional conundrum.

Critics have indeed spared no effort in denouncing the Constitution as being low on the legitimacy spectrum.Footnote 6 As Ayua and Dakas state,Footnote 7 any claim of a ‘We the People of the Federal Republic of Nigeria’ resolving and enacting the CFRN 1999 is fraudulent, since the Constitution is a product of a military decree and does not in any way come near a proper making of such a claim.

Afe BabalolaFootnote 8 recently expressed a similar sentiment when he stated that the problems currently being experienced by Nigeria are in large part attributable to the CFRN 1999. According to him, ‘what Nigeria needs is a bill sponsored by the government, asking the Senate to pass a law for the convocation of a Sovereign National Conference that the membership will be elected on zero party system’.Footnote 9

Undoubtedly, the legitimacy of a constitutional order is a fundamental question and, as Randy BarnettFootnote 10 notes, it is a proper question to ask and answer, or ‘we will never know whether we should obey it, improve upon it, or ignore it altogether’. It is, however, noteworthy that most of the discourse on the legitimacy question of the CFRN 1999 has not been grounded in any engagement with relevant constitutional, legal or political theory. This article makes a modest attempt to redress this. Without any question, the issue of constitutional legitimacy is multidimensional in nature. It is a jurisprudential question to which answers are as unsettled as there are commentators and writers on it, from its sceptics to its apologists, both drawing from critical interpretations of the nature of constitutional and legal order.

In fact, before World War I, the matter of constitutional legitimacy was a question that was rarely posed, as such a question was regarded as ‘unscientific’ and hence not permissible.Footnote 11 Even today, there are still some who regard the question of constitutional legitimacy as irrelevant to the good governance of a state as long as a country has an ‘effective’ government.Footnote 12

This article, however, takes the position that the matter of whether a Constitution is legitimate or not is germane and pertinent not only to good governance but also to peace, order, stability and progress – especially in deeply divided states such as Nigeria. It also contends that such a constitution is bound to be founded on the consent of the people in whom the pouvoir constituent (constituent power) resides.

This article contests this point. Section II highlights the nature of the constitutional legitimacy crisis in Nigeria before section III examines the circumstances surrounding the making of the CFRN 1999. Section IV then attempts to locate the legitimacy crisis in Nigeria in the light of different perspectives on constitutional legitimacy. Section V draws lessons from comparative perspectives, while section VII advances the discourse by exploring the applicability of constitution-making theories and models to the making of a legitimate constitution for Nigeria.

II. The constitutional legitimacy question in Nigeria

The constitutional legitimacy question in Nigeria is closely linked to the autochthonyFootnote 13 one. In the words of Visser and Bui,Footnote 14 ‘the autochthonous character of a constitution’ syncs with the concept of the sovereign status of a state, an expression of the sovereign will of its peoples. As contended by Udombana,Footnote 15 paraphrasing Nwabueze,Footnote 16 autochthony in fact constitutes the ‘source of constitutional authority’. A constitution can thus be deemed autochthonous where

its substantive content is freely agreed and adopted by the people either in a referendum or through a constituent assembly popularly elected for the purpose. This is notwithstanding that the constitution is subsequently promulgated by an existing authority, in the interest of formalism and regularity.Footnote 17

This link, of course, is derived from the historical roots of the Nigerian state. Before 1914, there was no geographical space known as Nigeria. Rather, what obtained was a multiplicity of kingdoms, empires and communities with widely differing cultural, religious, linguistic and governmental systems. The amalgamation was by imperial fiat in advancement of British colonial interests, and not a voluntary act of self-determination by the peoples concerned.

A quick look at Nigeria’s constitutional history also reveals the continued relevance of the legitimacy question. Nigeria’s constitutional history can be broken into two main eras: the colonial and the post-independence eras. None of the constitutional arrangements during the colonial era, including the Independence Constitution of 1960,Footnote 18 derived from the popular or sovereign will of the peoples of Nigeria.

Constitutions made in the post-independence era naturally divide into those derived from civilian authorities and those imposed by military authorities. Republicanism as Nigeria’s constitutional norm came in 1963 with the amendment of the 1960 Constitution, whereby the Queen of England ceased to be Nigeria’s titular head and appeals of decisions of the Federal Supreme Court no longer lay with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Supreme Court of Nigeria thus became the highest court of the land.Footnote 19

The 1963 Constitution has however been heavily criticised. First, since the Constitution was amended via the amending clause of the 1960 Constitution with cosmetic changes, some have doubted any ascription of autochthony or legitimacy to it.Footnote 20 As put by Bola Ige,Footnote 21 the 1963 Constitution was particularly conceived in bad faith and its ‘gestation and birth broke all rules for Constitution-making’.

However, the military broke faith on 15 January 1966 and hijacked power in a bloody coup d’état. This military incursion into power lasted until 1979, with the promulgation of the Presidential Constitution of that year and commencement of a civilian regime. The 1979 Constitution has been the nearest to the legitimate claim. It was drafted by a 49-member Constitution Drafting Committee (CDC) and subsequently deliberated upon and approved by a 230-member Constituent Assembly.

The 1979 Constitution has nonetheless been denounced for the manner of composition of both the CDC and the constituent assembly. All members of the CDC were appointed by the military, as were the leadership of the constituent assembly, the membership of which consisted of 203 members who were indirectly elected by local government councils while the rest were appointed. Also regarded as fatal to any legitimacy claim is the fact that the military adjusted the Constitution approved by the constituent assembly and went ahead to promulgate a different version.Footnote 22

The 1979 Constitution was equally short-lived, as the military struck again on 31 December 1983 and forcefully seized power. This era continued until 1999. Thus, when the opportunity to make another constitution arose between 1998 and 1999, many people were enthusiastic that the faults of the past would be remedied and a truly people-driven constitution reflecting the genuine wishes and aspirations of Nigerians would be fashioned. As discussed below, such expectations were soon dashed in the making of the CFRN 1999.

Another factor that continues to put the constitutional legitimacy question on the front burner is the division of the Nigerian state along varied ethnic identities. That Nigeria is a deeply divided state is perhaps begging the question. With over 350 ethnic groups and indigenous languages,Footnote 23 Nigeria definitely depicts a highly plural and heterogeneous society. Coupled with the presence of active social and political actors who continuously exploit the psychological elements of ethnic affiliationFootnote 24 to promote ethnic sentiments, mobilise members of different ethnic communities and deepen ethnic consciousness, the fact that Nigeria is divided principally along ethnic lines is easily understood. After all, according to Osaghae,Footnote 25 ethnicity connotes ‘the employment or mobilization of ethnic identity and difference to gain advantage in situations of competition, conflict or cooperation’.

The Nigerian political space offers a very fertile ground for such ethnic rivalry and competitiveness. Despite a century of togetherness under the banner of a single country, average Nigerians stills see themselves in the light of their ethnic identity. Indeed, ethnicity has been identified as the primary group and personal identity icon in African countries.

Writing on the Nigerian situation, Osaghae and SuberuFootnote 26 contend that ‘both in competitive and non-competitive settings, Nigerians are more likely to define themselves in terms of their ethnic affinities than any other identity’. This is corroborated by Lewis and Bratton,Footnote 27 and asserted by Osinubi and Osinubi,Footnote 28 who report on an in-depth study carried out in 2000 for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) by the International Foundation for Elections Systems (IFES), which identified ethnicity as the strongest type of identity among Nigerians. This goes for about half of all Nigerians (48.2 per cent), with 28.4 per cent and 21 per cent respectively opting for class and religious identities.

It goes without saying that in a deeply divided state such as Nigeria, the constitutional arrangement by which the state is to be governed must be one of which there is widespread acceptance and assent to its normative and institutional ethos. In other words, it must be high on the legitimacy spectrum if the goals of a peaceful, cohesive and prosperous society are to be attained.

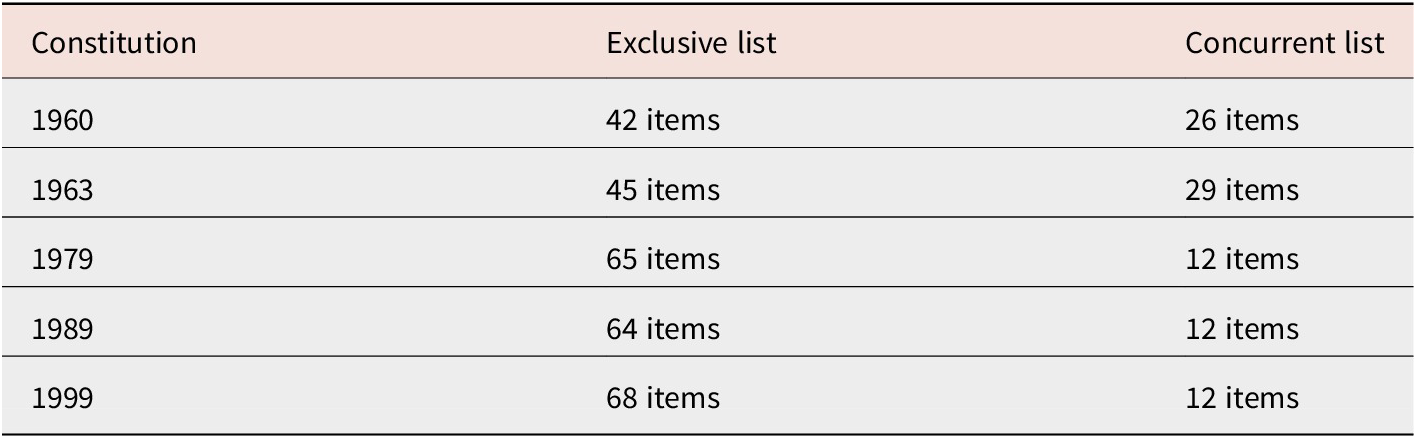

The fact that the current constitutional arrangement derives its authority not from the people but from the elitist military class is seen as making Nigeria worse than it was under the 1960 Constitution. That Constitution, after all, contained the terms of the Nigerian state as negotiated for transition into an independent and sovereign state. Some of these terms, such as the number of federating units and the division of powers between the centre and subnational units, have been substantially tampered with by the military. For example, while Nigeria under the Independence Constitution had three federating units (regions), under the current Constitution it has 36 federating units (states). The manner in which the centralist orientation of the military has played out in the division of powers is vividly portrayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Matters on exclusive and concurrent lists by constitutions

Source: MO Adediran, Constitutional History of Nigeria (Cleanprint, Ile-Ife, 2004) 98

Thus, while the 1960 Constitution had 42 and 26 items respectively on the exclusive and concurrent lists, the 1999 Constitution has 68 and 12 respectively. The increasing centralisation of powers and subsequent reduction of subnational competences thus became the trend.

All the issues discussed in this section continue to activate discontent with current arrangements under the CFRN 1999. This discontent manifests in various calls for ‘restructuring’, ‘true federalism’ and a sovereign national conference (SNC), where the basis, terms and other issues concerning the Nigerian federation are expected to be renegotiated.

The primary basis for the discontent against the Constitution is no doubt the procedure adopted for its making. This is not to discount the importance attached to the normative prescriptions; rather, the emphasis is the belief that the right procedure will produce prescriptions that will be acceptable to all.

III. The making of the CFRN 1999

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFRN) 1999 is the Constitution that is currently in force in Nigeria. Upon the death of General Sani Abacha on 8 June 1998, the mantle of leadership of the military junta fell on General Abdulsalami Abubakar. The political climate at that time did not permit the military to stay any longer than necessary in power. The government thus felt it had to fashion a Constitution and successfully transit to civilian rule as soon as possible. Towards this, General Abubakar on 7 September 1998 made known his transition to civilian rule programme.Footnote 29

General Abubakar thereafter set up a 25-member Constitutional Debate Coordinating Committee (CDCD), composed of experts drawn from academia, the legal profession and retired military officers. The Committee’s mandate essentially was to come up with a Constitution that would be acceptable to the generality of Nigerians by reviewing the 1995 draft Constitution.Footnote 30

The CDCDFootnote 31 which commenced its work on 11 November 1998, organised public hearings in ten cities, including a special hearing in Abuja; held several workshops; and received over 405 memoranda. The Committee thus purportedly interacted with or received information from different sectors of Nigerian society.Footnote 32

It did this within a period of less than two months. It is said that the preponderance of opinion received took a staunch objection to the 1995 Constitution, particularly on the basis that the conference that drafted it ‘was unrepresentative, since voting for the 273 elected members had been marred by boycotts and cynicism to include only 400,000 voters’.Footnote 33

The Committee’s report submitted to the military government thus indicated preference for a reversion to the 1979 Constitution (with minor amendments) instead of the still-birthed 1995 Constitution, as the latter purportedly ‘lacked credibility as a means to introduce democratic reforms’.Footnote 34 It should be noted that although the (military) Provisional Ruling Council (PRC) accepted most of the Committee’s recommendations, it also typically tinkered with some. The Council, even after the Federal Ministry of Justice had produced a draft Constitution based on the Committee’s report as amended, still re-examined the draft. The Constitution was thereafter promulgated into existence with effect from 29 May 1999.Footnote 35

It should briefly be noted that any attempt to found the legitimacy of the CFRN 1999 on the 1979 Constitution may not stand. First, the 1979 Constitution itself was a military constitution with a faulty process in its making. For instance, as previously mentioned, all members of the 1975 Constitutional Drafting Committee (CDC) that initially drafted the constitution were handpicked by the military, while members of the 1978 Constituent Assembly – apart from containing nominated members – were not elected through popular votes. Some matters were also not up for discussion by both the CDC and Constituent Assembly,Footnote 36 and the military later tinkered with the draft constitution of the assembly before promulgating it.

Further, the military cannot approbate and reprobate at the same time. If the military took power in violation of the 1979 constitution, it surely could not base the 1999 Constitution on the constitution it had flagrantly violated. It could, of course, have recognised the continuous validity of that constitution up to the time of handover. This would have translated into the liability of all who participated in the coup of 31 December 1983 for the crime of treason. Notably, the basis of the Nigerian federation was not addressed during the making of the 1979 Constitution.

A question may equally be raised that if a 1995 Constitution crafted through an elaborate process involving a 369-membership strong National Constitutional Conference is considered as lacking in credibility, how will the one hurriedly packaged by a select team of 25 be described? It is therefore not surprising that the CFRN 1999 has, since the date of its promulgation, consistently been resisted, denounced and rejected by various sectors of Nigerian society.Footnote 37 So how does the CFRN 1999 stand in providing an answer to the legitimacy question in the light of theoretical perspectives on constitutional legitimacy?

IV. Some perspectives on constitutional legitimacy

Based on the above discussion, the constitutional legitimacy question in Nigeria, while historical, is located more in the dissatisfaction with the undemocratic process from which previous constitutions emerged – particularly the current one. Does this find support in Western thought? Put otherwise, how do notable theoretical positions on constitutional legitimacy apply to the Nigerian case?

Legal, sociological and moral perspectives

According to Richard Fallon Jr,Footnote 38 the legitimacy of a Constitution is a question that may be determined legally, sociologically or morally. Carlos BernalFootnote 39 presents a similar typology except for the replacement of the moral sense of discussion on legitimacy with the normative one. For example, assessing the legitimacy of a Constitution on a legal basis considers the question from the perspective of its conformity or non-conformity to some legal norms. It is, however, easier to assess the legal legitimacy of a statute based on its conformity or otherwise with extant constitutional provisions than to gauge the legal legitimacy of the Constitution itself – especially in its making.

This is largely because the Constitution presents a priori evidence of its own legality or validity. Circumstances surrounding its making, especially when made as an act of self-determination or as a consequence of a revolution, are viewed as law creating facts, and its compliance with any legal norm normally takes a back seat.

It is therefore taken in this article that as much as it is desirable to comply with extant legal norms, both in the making and execution of a constitution, legal legitimacy may after all not offer much succour to the concerns of the constitutional legitimacy debate. Constitutions made by military juntas such as the CFRN 1999 are, after all, made to conform to some legal requirements for their enactment, yet this fact does not mean such constitutions evade the legitimacy question by constantly assailing such requirements. The noisy character of the claims of legal legitimacy is further evinced when the ultimate norm during Nigeria’s military regimes is taken into consideration. This, briefly stated, is whatever the military regime, through its supreme military council, permits or sanctions.Footnote 40

The sociological sense of the legitimacy question applies where the general public regards the constitutional system ‘as justified, appropriate, or otherwise deserving of support for reasons beyond fear of sanctions or mere hope for personal reward’.Footnote 41 From a sociological perspective, a constitution is legitimate when it is accepted as worthy of respect or obedience, or where it is otherwise acquiesced to.Footnote 42 However, the issue of whether an obligation exists to obey law qua law is one that continues to beset jurisprudential discourse. The problem as put especially by natural law critics of positivism is that even supposing the claims of the latter are true, there surely cannot be a moral obligation to obey law qua law.Footnote 43

A subjection of the CFRN 1999 to the set of criteria embedded in the claims of constitutional legitimacy from the sociological perspective may also not be favourable. The fact of military origin is no doubt ordinarily inimical to a legitimacy claim. This is surely exacerbated by the circumstances surrounding the making of the Constitution. As previously noted, the CFRN 1999 was the product of a 25-member committee and subsequent adjustment by the military council. There was no Constituent Assembly, not to mention any recognition of the people’s constituent power. All we have are the fraudulent ‘We the People’ claim in the preamble and the false assertion in section 14(2)(a) that ‘sovereignty belongs to the people of Nigeria from whom government through this Constitution derives all its powers and authority’. How can a Constitution that does not derive from the people make such bogus claims? No wonder the condemnations and objections that greeted its promulgation have continued to the present time.

Richard Fallon Jr identifies the moral sense as the third conception of constitutional legitimacy. In other words, in order to be regarded as legitimate, the Constitution is held up in the light of certain moral standards of governance and law-making. A constitution’s legitimacy in this sense is regarded as a ‘function of moral justifiability or respect-worthiness’.Footnote 44

Frank MichelmanFootnote 45 has, for instance, posited that ‘governments are morally justified in demanding everyone’s compliance with all the laws’. According to him, citizens will also ‘be morally justified in collaborating with the government’s efforts to secure such compliance … if, and only if, that country’s general system of government is reliable or shall I say, “respect-worthy”’.Footnote 46

Theories in this regard have been advanced prescribing ideal, minimal and intermediate standards. For ideal theorists, moral legitimacy is grounded on the highest possible standard of justice.Footnote 47 The unfortunate conclusion of this view, however, is that a perfectly just (if at all possible) constitutional state is considered legitimate even where its bearers of power govern without consent.

On the other hand, some base moral legitimacy on consent. Of course, based on the principle of volenti non fit injuria, grounds for objection or disobedience may not arise when the state applies principles to which its citizens have furnished prior consent.Footnote 48 A variant of the consent theory is the hypothetical consent theory espoused by John Rawls.Footnote 49 In his classical work on justice, he conceives it by reference to ‘the principles that free and rational persons would accept in an initial position of equality as defining the fundamental terms of their association’.Footnote 50

Rawls’s ‘liberal’ theory of legitimacy thus posits that the ‘exercise of political power is proper and hence justifiable only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution the essentials of which all citizens may reasonably be expected to endorse in the light of principles and ideals acceptable to them as reasonable and rational’.Footnote 51

In contradistinction to ideal theorists, advocates of minimal theories usually premise their thesis on the absolute necessity for a government to assure decent human lives in modern times.Footnote 52 They are willing to accord the legitimate garb to any government that guarantees a minimal threshold of justice ‘in the absence of better, realistically attainable alternatives’. Raz,Footnote 53 for example, asserts the self-validating feature of constitutions provided ‘they remain within the boundaries set by moral principles’.Footnote 54

As previous discourse indicates, the matter of consent is crucial in the constitutional legitimacy debate, especially for a highly divided state such as Nigeria. This article thus considers the consent foundation of constitutional legitimacy as being germane in explaining and resolving Nigeria’s constitutional legitimacy crisis. It is, of course, to be noted that mere acquiescence does not translate to consent. Rawls’ hypothetical consent theory, particularly his ‘original position’ proposition, may in the final analysis be crucial for attaining a cohesive and progressive society, particularly in ethnically divided societies. The means, process or procedure by which a constitution is made is therefore important in deciding or swinging the pendulum of its legitimacy question.

Assured procedure for just laws?

BarnettFootnote 55 has, however, denounced the possibility of a legitimacy derived from general consent of the governed. This is because he views any argument of constitutional legitimacy being traceable to the consent of ‘We the People’ as factitious.Footnote 56 In the absence of the otherwise required unanimous consent, the Constitution may only be legitimated by ‘putting enforceable limits on government powers-limits that would not be necessary if unanimous consent existed’.Footnote 57 Such constitutional limits manifest in assured law-making procedures that result in the enactment of just laws or that ensure unjust laws do not ensue. Only when this happens, according to Barnett, would a moral duty to obey the resulting laws arise – an outcome of a legitimate legal system. This is because ‘a constitution that lacks adequate procedures to ensure the justice of valid laws is illegitimate even if consented to by a majority’.Footnote 58

Barnett’s thesis presupposes that once enforceable constitutional norms are made, their prescriptions would necessarily be followed. While this may be a self-assertive quality of Western legal systems, experience points to its absolute negation in the constitutional regime of most African countries, including Nigeria, where the rate at which constitutional norms and legislation are breached by political actors who have sworn to uphold and defend the Constitution indicates that some other factors are in play in the determination of the legitimacy question.

At the forefront among these, no doubt, are the manner by which the constitutional norms themselves are derived and the existence or absence of a constitutional culture that favours enforcement. This article thus argues that whether or not the procedure by which a constitution is made is consensual is fundamental to the question of its legitimacy. It may be noted, however, that Barnett was not ‘asking why people perceive a constitution to be legitimate and constitutional laws binding in conscience’.Footnote 59 Rather, his concern was on ‘what qualities a constitution should have to justify this perception’.Footnote 60

Prevailing attitudes and beliefs

The contribution of Richard KayFootnote 61 to the legitimacy question is quite incisive. To him, constitutional legitimacy closely relates to the acceptability of the applicable pre-constitutional rule. His conception of ‘preconstitutional rule’ syncs with the ‘basic norm’ of KelsenFootnote 62 and Hart’s ‘rule of recognition’.Footnote 63

Kay posits that two issues must be evaluated while discussing ‘the legitimacy of a preconstitutional rule’. These are the contents and origins of the pre-constitutional rule, both of which must conform with the ‘values and beliefs’ of the particular society it seeks to regulate.Footnote 64

A pre-constitutional rule is therefore legitimate where its acceptability is ascertained on the basis that it derives from the ways (attitudes, beliefs, traditions and values) of the society ‘in which the legal system is to be effective’.Footnote 65 Kay’s thesis is quite useful in explaining the legitimacy crisis of the CFRN 1999, the pre-constitutional rule of which, as previously captured, is ‘whatever the military regime through its supreme military council permits or sanctions’.

If this is contrasted with the heterogenous nature that informed the federal system of Nigeria, the reason why the CFRN 1999 is low on the legitimacy spectrum may not be so far-fetched. A federal constitution that is an agreement between the different levels of government may certainly not be solely drafted and promulgated by a central autocratic government without hiccups in the polity necessarily resulting. Hence, is the need to ensure that the procedure by which the constitution of a plural society is made captures not only the support of the various nationalities but also their aspirations and needs.

Traditional, charismatic and rational legal authority

An application of Max Weber’s trio categorisations of legitimate authority to the legitimacy question of the CFRN 1999 also seems useful.Footnote 66 Weber, on the whole, contends that a legal system is ‘legitimate if those subject to the system have made a value judgment that the laws promulgated by the system ought to be obeyed’.Footnote 67

To Weber,Footnote 68 legitimate power could manifest as traditional authority, charismatic authority or rational legal authority. The legitimacy of traditional authority derives from the faith or consciousness of subjects in the rightness of the legal order by virtue of its existence from time immemorial, while that of charismatic authority flows from the charisma (extraordinary abilities) of the one holding the power.

Charismatic leadership, can no doubt be contagious in eliciting widespread obedience and acceptance. Things go well as long as the leaders retain their charm, while matters of order and authority in the legal system may quickly go south where the charm is lost due to real or apparent perceptions of incompetence, misdeeds and the like.

The legitimacy of rational legal authority, on the other hand, either rests on faith in the absolute applicability of the norms prescribing the power or on the state’s coercive order based on formally correct rules established in a customary way. Both scenarios presuppose some ascription to a priori rules of validity at the base of the legal system.

Traditional authority certainly syncs with the African ethos, but the CFRN 1999 is certainly not vested with traditional authority – certainly not in the manner of its making nor in the norms it espouses. In contrast, despite the Constitution not recognising the traditional governance system, the precolonial traditional system, instead of fizzling out, has remained evergreen and relevant to the Nigerian polity.

It may also not lay any claim to charismatic authority, either in its making or implementation so far. The military junta, by the time of the making of this Constitution, had (if it ever had any) in fact lost its charm for the Nigerian people. By the time of Abubakar’s regime in 1998, the cumulative effect of the economic downturn of the Buhari regime, the endless transitions of the Babangida regime and the totalitarian junta of the Abacha era had clearly demonstrated to Nigerians the futility of pinning any hope on the military for the redemption of the Nigerian state.

The CFRN 1999 would ostensibly have laid claim to legal authority, but considering the hurried, non-democratic and non-inclusive manner in which the Constitution was fashioned, any such claim may equally fail. As noted by Julius Ihonvbere,Footnote 69 the rules of the game were not even ascertainable as at the time of the conduct of the general elections in 1999, as the CFRN had not been promulgated.Footnote 70 It is indeed interesting that the military junta had opened up the space for democratic elections to form governments at both federal and state levels without anyone knowing the contents of the legal and political charter (the Constitution) dictating the terms thereof.

Normative, nominalist and semantic constitution

Another interesting contribution to the discourse on constitutional legitimacy is the theory of normative, nominalist and semantic constitution put forward by Karl Loewenstein.Footnote 71 A nominalist constitution in this respect is one in meaning only, and is not a means of substantive legal or political ordering, as ‘conflicts between the constitutional norm and constitutional reality are resolved in favour of the latter’.Footnote 72

Loewenstein, curiously, considers this type of constitution justified (legitimate) as a means of political education, due to the factual existence of some goodwill on the part of both the addressees and bearers of power to make the constitution normative in the future. However, this article takes the view that a Constitution that is not predictive of political and constitutional reality may not come near being termed justified or legitimate.

A semantic constitution is one that depicts no discrepancy between norms prescribed by the constitution in question and factual legal realities. The problem rather lies in the ends to which the constitution is put, being utilised as a tool for perpetuation of the bearers of power’s will for the continuous domination of the addressees of power. The constitution serves not to limit exercise of state power but instead is employed to validate it.Footnote 73

The ideal form, according to Loewenstein, is found in the normative constitution, where constitutional norms inform or guide state actions and processes. The result is a constitutional state where the rule of law, as opposed to the rule of men or rule by law, obtains as ostentatiously practised and canvassed by Western democratic nations. To Loewenstein, while normative and nominalist constitutions can lay claim to legitimacy, semantic constitutions, being ‘apparent constitutions’, surely cannot.

Loewenstein’s postulates beg at least two questions, however. First, does constitutional fidelity equate constitutional legitimacy? It may indeed be unequivocally stated that, while a legitimate constitution may determine the extent to which the norms prescribed thereunder inform political and governmental relations, the fact that they do does not necessarily determine that constitution’s legitimacy.

The second question borders on whether constitutional legitimacy is in any way a function of adopted governmental forms or tied to the constitution’s philosophical basis? Yes, a fascist or totalitarian system may, among others, seriously compromise human rights and undermine the principles of democracy as advanced by Western societies. All the same, the question of constitutional legitimacy raises a different set of issues distinct from that of the operative governmental system. In addition, the philosophical or ideological base of a Constitution does not usually obviate nor expedite its legitimacy.

Determining where the CFRN 1999 lies in the Loewenstein’s typologies of nominalist, semantic and normative constitutions is problematic. It cannot be said to be completely nominalist, as there is nothing interim about it. Also, while it portends a normative claim, experience in the past 22 years of its operation indicates that there is often a wide gap between its norms and political cum legal realities.

Three examples may suffice to illustrate this. In 2004, former President Obasanjo gave instructions to the Minister of Finance to forthwith stop the release of revenue meant for local governments to Ebonyi, Katsina, Lagos, Nasarawa and Niger states, simply because these states, taking advantage of the provisions of section 8(3), had created new local government areas in their respective states. The Supreme Court in Attorney-General of Lagos State v Attorney-General of the Federation Footnote 74 invalidated the step taken by the federal government and sharply rebuked it for resorting to self-help instead of seeking judicial redress as provided for by the Constitution.Footnote 75

Also, on 25 January 2019, some weeks to the holding of nationwide general elections, the current President Buhari, in flagrant abuse of constitutional provisions, suspended Justice Walter Onnoghen, the Chief Justice of Nigeria, from office. The move, which attracted national and international condemnation, was premised on allegations of failure to declare certain assets levelled against the CJN some fifteen days prior to the suspension.Footnote 76

The President took this step despite the clear constitutional norm forbidding the removal of the CJN from office except where the President is acting upon an address supported by two-thirds majority of the Senate that the office holder be so removed ‘for his inability to discharge the functions of his office or appointment (whether arising from infirmity of mind or body) or for misconduct or for contravention of the Code of Conduct.’Footnote 77 The President equally conveniently forgot that the power to discipline erring judicial officers is, in the first instance, constitutionally vested in the National Judicial Council.Footnote 78

The third example relates to the discrepancy between the legal regime prescribed by the CFRN 1999 for local government administration and the factual situation in many states of the Federation from 1999 to the time of writing this article. By the unambiguous prescription of section 7, local government councils must be democratically elected, constituted and administered. However, in many states today, local government councils are constituted with handpicked members nominated or appointed by the Governor. This anomaly continues despite several decisions of the court, which have held the practice as being unconstitutional.Footnote 79

For instance, the Court of Appeal in Barr. Enyinna Onuegbu & Ors v Governor of Imo State & Ors Footnote 80 held that, since the Constitution in section 7 guarantees ‘the system of local government by democratically elected local government councils’, any attempt by a state government to do otherwise would be null and void. Such an attempt includes the running of the councils by transitional or caretaker committees whose members are nominated and not elected. This decision is in line with several others, indicating the non-normative character of the CFRN as perpetuated by the political actors themselves.

In relation to appointed local government councils, the crux of the matter, though objectionable, has not been whether state governments can dissolve democratically elected local government councils by following due process in qualifying circumstances; rather, it is that in such a case, a by-election should be conducted to reconstitute the council rather than the council being replaced by nominated members by the state government.Footnote 81

It may indeed be argued that the CFRN 1999, to the extent that it serves as a tool in the hands of the bearers of power for their perpetuation in office or corridors of power solely for the advancement of their own interests, seems to be more of a semantic constitution. Such a constitution, according to Loewenstein, may of course not lay any claim to legitimacy.

However, as already seen, the CFRN equally has nominalist and normative characters. It all depends on the circumstances as perceived by the bearers of power. This leads to an interesting typology (Figure 1) of its amorphous character in sharing traits of a nominalist, semantic or normative constitution. This brings to mind the position of Richard Fallon JrFootnote 82 that ‘the sorting of legitimacy claims into neat linguistic categories sometimes proves impossible’, as the debates on the legitimacy question ‘reflect concerns with the necessary, sufficient, or morally justifiable conditions for the exercise of governmental authority’.Footnote 83

Figure 1 Amorphous character of CFRN 1999

V. Comparative perspectives

Contingent upon the consent basis for constitutional legitimacy, it is understandable that the dissatisfaction with the CFRN 1999 is tied primarily to issues surrounding its making. The Abubakar military regime in 1998 was not particularly interested in any democratic and process-led constitution-making exercise, hence the CFRN 1999 was principally ‘made’ by the 25-member coordinating committee with final inputs by the military junta.

This clearly contrasts with the making of the 2010 Kenyan Constitution, which in its two phases attracted far much more inclusive popular participation and intense engagement with substantive provisions. The first phase,Footnote 84 from November 2000 to November 2005, was a people-driven process under the auspices of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC),Footnote 85 the National Constitutional Conference (NCC)Footnote 86 and the National Assembly (KNA).Footnote 87 The process suffered a setback when the KNA, which initially did not possess the power to modify the draft Constitution adopted by the NCC, was eventually granted this power, resulting in a very different draft to the one approved by the NCC. At a referendum on 21 November 2005, the Kenyan people subsequently roundly rejected the Constitution as modified and passed by parliament.Footnote 88

The second phase, with wisdom garnered from the pitfalls of the first phase and the nasty violence that visited the announcement of the results of the 2007 elections, kicked off under a new arrangement under the Constitution of Kenya Review Act 2008 and complementary amendment of the 1963 Constitution.Footnote 89 This phase was principally driven by a Committee of Experts (CoE), whose job was to reconcile the drafts of the first phase, focusing only on the contentious areas.Footnote 90 The committee,Footnote 91 having adopted its draft, was to submit it to a Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC), which had 21 days to deliberate on it, reach consensus and return the draft to the CoE for incorporation of its agreed inputs.Footnote 92 A special Interim Independent Constitutional Dispute Resolution Court was set up to handle any litigation that might arise as part of the review process.Footnote 93

As noted by Murray,Footnote 94 ‘The first clear indication that the process was on track was in November 2009 when the CoE released a draft constitution to the public for the brief month of consultations provided for in the Review Act.’Footnote 95 The committee amended the draft thereafter, incorporating inputs from the public into it, and was able to submit its draft to the PSC by early 2010. The amended draft adopted by the PSC was later reviewed by the CoE (accepting some and rejecting some) before it submitted its final draft to parliament for approval. On 1 April 2010, parliament passed the draft, which after a period of public education was submitted for adoption at a referendum on 5 August 2010. The Constitution was adopted by 67 per cent of the Kenyan people.

The legitimacy of the constitution was thus ensured and enhanced through the massive public participation in the first phase and the close linkage of the second phase to the first phase. In fact, if any defect may be attributed to the second phase, the final adoption by referendum – a recognition of the people’s sovereign will – was certainly designed to cure it. Indeed, the referendum criteria were a sine qua non of the entire process. This was the thrust of the decision in Njoya v AG, Footnote 96 where the court held that the constitutional power to alter the constitution does not amount to the power to replace it by a new one. This can only be done as an act of the people’s constituent power.Footnote 97

Similarly, the legitimacy of the South African Final Constitution (FC) was founded upon an inclusive, broadly based and highly participatory two-step process. The 1993 multi-party negotiations signalled not only the end of the apartheid regime, but also the commencement of a liberal, democratic society. Solace was found in an interim constitution, with sufficient guaranteesFootnote 98 that the multi-party agreement would be honoured even after power had slipped out of the hands of the National Party, then the ruling party.

The path of legality was followed as the apartheid government adopted the agreement, but it was clear to all that a break with the old order would occur and a new one would result with the holding of the 1994 elections and the coming into effect of the interim constitution. The elections and the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) thus indicated the end of the first step and the commencement of the second step of the constitution-making exercise.

The FC itself was to be made within two years and the bicameral parliament served as the Constitutional Assembly (CA) in its drafting and passage. The 490-member strong CA, chaired by Cyril Ramaphosa,Footnote 99 in some fifteen months of active debate and decision-making, engaged with over two million submissions (including 11,000 substantive submissions), and generally reached decisions over contentious issues through negotiations and compromise.Footnote 100

By September 1995, the first draft had been produced for review by a Panel of Constitutional ExpertsFootnote 101 and, despite all odds, the CA met the 9 May 1996 deadline by passing the draft Constitution. The process then moved to the newly established Constitutional Court (CC), which had the function of certifying the draft as some took the opportunity to contest the consistency of some provisions of the draft with the constitutional principles. The court, having failed to certify the draft,Footnote 102 kickstarted another round of further negotiations and compromises, which culminated in the adoption and certification of the amended draft by the CC on 4 December 1996. The FC was signed on 10 December 1996 and took effect on 4 February 1997.

The making of the US Constitution in 1787 was no less eventful. To cure the deficiency of the Articles of Confederation, the delegates at the September 1786 Annapolis convention convened by the Virginia legislature had proposed to Congress to convene another convention in Philadelphia ‘to devise such further provisions as shall appear to [the delegates] necessary to render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the union’.Footnote 103

The Philadelphia convention did hold, and delegates went forward to devise a federal constitution that significantly depart from the extant confederal one. Also, in defiance of the amending clause under the Articles,Footnote 104 the approved mode of adoption of the new constitution was through ratification ‘by specially elected conventions in each state.’Footnote 105 The Constitution eventually ‘became the supreme law of the land’Footnote 106 upon the inauguration of the federal government in 1789.

Even, where the amending clause was followed and the amendment has the character of a different constitution than the one being amended, in the Rawlsian view this would have amounted to a revolutionary change and not just a mere amendment.Footnote 107 According to Richard Albert, this occurs where ‘the alteration is so transformative that we must recognize that conceptually the effect of the change is not merely to amend the constitution but rather to create a new one’.Footnote 108 Regarding the making of the US Constitution, however, the combined effect of state delegates who fashioned the Constitution and the special conventions of each state that ratified it no doubt served to ground its legitimacy on solid grounds, particularly when it is noted that the Constitution was only binding on the states that ratified it.

VI. The making of a legitimate constitution

It may thus be expedient to consider the constitution-making model that could best suit the Nigerian situation. Constitution-making is often regarded as pivotal work to design a durable governmental structure for the good governance of a society. It has, however, been contended that the ‘constitution moment’ need not be so momentous. It may also occur purely as part of normal politics.Footnote 109 So how may the Nigerian constitutional legitimacy crisis be remedied: through a momentous process or a normal political (legal) process?

It may quickly be mentioned that, since 1999, two national (constitutional) conferences have at different times been held unsuccessfully by both the Obasanjo and Jonathan administrationsFootnote 110 in an attempt to redeem the Constitution. Frantic efforts have also been made (and continue to be made) to amend it. For example, in 2017 alone, the Nigerian Senate proposed 32 new amendments to the Constitution. Only five survived at the end of the day.Footnote 111 Currently, there are nothing less than eight Bills proposing amendments to different provisions of the Constitution before the House.Footnote 112

Thus, on how best the legitimacy crisis of the CFRN 1999 might be remedied, two options readily surface. The first is to continue the current drive towards amendment by utilising the relevant clause of the constitution. The second is to jettison the constitution completely in favour of a new one.

The first option is presently favoured by the bearers of power, who understandably are desperately looking for a way to save the fortunes of the CFRN 1999 in a bid to save their own vested interests in the polity. It is crucial to note that many prominent members of the current ruling party, while in the opposition,Footnote 113 had been vociferous in demanding the abandonment of the CFRN 1999 in favour of a new constitution negotiated and approved at a Sovereign National Conference (SNC).Footnote 114 It is interesting that since their party came into power in 2015, nothing has been done about the SNC.

So, if Nigeria continues on the path of reforms through constitutional amendments, will the CFRN 1999 overcome its legitimacy crisis? It is undeniably difficult to answer this question in the positive. It holds, however, that a disinclination to put the process of convoking a SNC into place is itself sufficient to disclose a disinterest in an open, frank and honest discourse on the basic governance issues that afflict the Nigerian polity not to talk of addressing them.

The second option is to discard the CFRN 1999 in favour of a new constitution that meets the genuine yearnings of the people of Nigeria. This is captured in the call for a SNC. Indeed, the clamour for a SNC goes beyond any possible cosmetic changes to the constitution, since these may never adequately address underlying factors such as growing ethnic tensions and distrust.Footnote 115 The clamour goes to the very essence and terms of the Nigerian state, which are expected to be robustly discussed and renegotiated at the conference. It also calls for a radical paradigm shift in constitutional engineering.Footnote 116

How does the idea of a SNC stand in constitution-making terminology? Hannah ArendtFootnote 117 has identified three ways by which constitutions tend to emerge historically. She posits that constitutions ‘can be products of a long process of organic evolution, acts of an already established government, or created by revolutionary assemblies in the process of constituting a government’.Footnote 118 Andrew Arato identifies five different mechanisms of making constitutions in modern times: constitution-making through the constitutional convention, the sovereign constituent assembly, normal legislature, the executive, and an evolutionary process.

Since the SNC is conceived as an autonomous body, the decisions of which may only be subject to ratification by the people at a referendum, it may be said that it would fit into either Arendt’s revolutionary assembly or Arato’s sovereign constituent assembly categories. This nowhere denies the fact that all constitutions, in a sense, are products of the ‘evolutionary process’ of particular societies. The sense here is when the term is considered in its historical sense, the attribution of the term to unwritten constitutions notwithstanding. In this sense, written constitutions no doubt are products of history, of an historical moment with peculiar socio-political interplays.

The SNC, nevertheless, seems to sync more with the idea of a sovereign constituent assembly. Here, important questions bordering on the validity and legitimacy of the resultant constitution rest on the determination of certain factors. These factors, according to Jon Elster, are multidimensional.Footnote 119 The first is the manner of constituting the assembly, a matter he believes raises the problem of ‘upstream legitimacy’. The problem of ‘process legitimacy’, on the other hand, concerns the nature (democratic or otherwise) of decision-making rules adopted by the assembly. Others are whether the resultant constitution is for the ‘common good’ or an outcome of elitist bargaining, whether or not the assembly’s deliberations are public and whether or not the constitution is ratified by popular votes at a referendum (‘downstream legitimacy’).

These questions are somehow related to pouvoir constituent, as espoused initially by SieyèsFootnote 120 and consequently by SchmittFootnote 121 – the theory that locates sovereignty (all powers) in the people.Footnote 122 Constituent power, in this regard, simply refers to ‘the power to establish the constitutional order of a nation’.Footnote 123 While sovereignty (constituent power) in this model inheres in the people, power to make (consult, negotiate, argue, discuss and draft) constitutions is vested in an autonomous constituent assembly, which exercises this power as deemed fit. In this way, the constituent assembly, after successful deliberations and drafting, submits the constitution to its principal (the people) for ratification in a ‘national, majoritarian referendum’.Footnote 124

According to Sieyès, the people exercise their constituent power in two ways. The first is through normal legislative assembly, while the second is through revolutionary constitutional assembly, which in exercise of its sovereignty operates outside the existing constitutional order to constitute a new order according to its light.Footnote 125 The Constitution thus derives its authority from the constituent power and not otherwise.Footnote 126

To Schmitt, the sovereignty of the constituent assembly is further exercised in it not being subject to any other governmental authority, as during the pendency of constitution making, it stands as the one vested with constituent as well as legislative, executive and judicial powers. Is he then proposing some kind of tyranny of a few? Not really, as long as the assembly is completely identified with the people on whose behalf it subsists.Footnote 127

As AratoFootnote 128 states, the model of constitution making considered fully democratic by Schmitt consists of five elements. All previously constituted powers are first dissolved, followed by a popularly elected or acclaimed assembly with a plenitude of powers. The assembly then begins to function as the government on a provisional basis. Next, the constitution that has been drafted is offered for a national, popular referendum and finally, if ratified, the assembly becomes dissolved as a new government is duly constituted under the Constitution.Footnote 129

It may be said that this model has three main implications.Footnote 130 First, new constitutions should not be made by ordinary legislative bodies but by especially constituted constitutional conventions. Second, the constitution-making process should be participatory. This, as espoused by Ackerman,Footnote 131 is a kind of higher track politics. The third implication concerns the independence, or what some designate as the sovereignty, of the constituent assembly.Footnote 132

It seems reasonable to assert that the democratic and impartial nature of this model, if utilised for the SNC, may go a long way towards ensuring that sectional, selfish or banal interests are eschewed – that the resultant Constitution will only contain provisions which advance common societal goals. This, in turn, may ensure stability and progress of the polity. This position founds upon the reality of reaching consensus across ethnic lines in order to achieve an inclusive constitutional order.Footnote 133

Solongo Wandan,Footnote 134 who termed constitution-making based on recognition of pouvoir constituent as the democratic-originalist position, has identified a contrasting model named the democratic-constructivist position. The democratic-constructivists deny the existence of any ‘logical and necessary relation between popular democratic origins and constitutional democratic outcomes’.Footnote 135 They contend that the ‘self that gives itself a Constitution’Footnote 136 is not a pre-existing agent but one constructed as part of the constitution making process. As put by Hahm and Kim,Footnote 137 it is definitely not a ‘pre given, clearly bounded, and self-sufficient agent prior to the drafting of the constitution’.

Supporting their position from historical and empirical bases, the democratic-constructivists contend that no ‘democratic state has accomplished comprehensive constitutional change outside the context of some cataclysmic situation such as revolution, world war, the withdrawal of empire, civil war, or the threat of imminent breakup’.Footnote 138 They also point to the international character of modern constitution-making as negating the concept of a ‘pre-existing unified constituent agent’.Footnote 139

Yet the democratic-constructivists’ rejection of the constituent power theory needs to be approached with caution, especially in its consideration of people who make constitutions for themselves as agents. This is particularly so as a careful reading of the constituent power construct shows a clear distinction between it and the concept of constituted power as previously ascertained.Footnote 140

The people in whom constituent power inheres are thus agents of no one. Instead, a principal–agent relationship exists between them and constituted powers, which manifest as the constituent assembly or as the constituted government.Footnote 141

As previously asserted, the constituent assembly model thus has some appeal for the advocated SNC. However, to what extent would a sitting government agree to its dissolution for a constituent assembly to assume and exercise plenary state powers? First, it is obvious that the government may be more inclined to go this way provided its dissolution occurs at the end of its term than at any other time. Second, a government may equally be so persuaded provided the ruling party is confident of being able to significantly influence the composition of the constituent assembly at a free and fair elections. Third, the political will to unequivocally make a people-driven constitution must be particularly strong. The fourth and least desired option is for the government to be forced to concede to it through a revolution.

A revolution is the least desired option, inasmuch it is aimed at hijacking governmental powers by force beyond the extant provisions of the constitution. In this sense, it does not matter whether or not the revolution is a bloody one. Two reasons for the undesirability of this option may here suffice. First, such a recourse offends current norms of international and regional law, such those contained in the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.Footnote 142 Second, Nigeria’s experience – like those of many other African countries – has clearly indicated the futility of hoping any good will come from any government that comes into power through sheer force. This does not, however, mean a revolutionary movement within the confines of the law is not possible.

Although attempts at defining political will may be problematic, the term surely connotes the extent of readiness or willingness on the part of the government of the day to embark on a particular policy direction or outcome.Footnote 143 We can then ask what factors may determine the presence or absence of the political will to convoke the SNC in Nigeria. The crystallisation of the political will in this direction may no doubt be easier in the presence of ideological persuasion among notable leaders.

As previously stated, there does seem to be some persuasion among various leaders across the political spectrum that addressing the legitimacy question of the CFRN 1999 requires frontally confronting the fundamental problems confronting Nigerian society, without which the quest for a cohesive and development-oriented society may not be kickstarted. In fact, a new political movement that announced its birth on 1 July 2020 also expressed its commitment to initiate:

A new ideological mass Movement … to embark on immediate mass mobilisation of the nooks and crannies of the country for popular mass action towards political constitution reforms that is citizens-driven and process-led in engendering a new Peoples’ Constitution for a new Nigeria that can work for all.Footnote 144

Among the notable names in the new movement are former Speaker of the House of Representatives Ghali Na’abba; former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank, Dr Obadiah Mailafia; Colonel Abubakar Umar (retd.), Dr Oby Ezekwesili; Professor Jibo Ibrahim; Yabagi Sanni; Amb Nkoyo Toyo, Isa Aremu, Professor Chidi Odinkalu and Senator Shehu Sani.

How successful will the conceived ‘ideological mass movement’ be? Obviously, only time will tell. However, it may be said that although the road to a democratic and legitimate constitution may be tedious and long, it is one that must be certainly traversed in order for the activating factors in the Nigerian polity to be settled.

There is, however, a snag in following the constituent assembly model for the convening of the SNC. This is because the conceived plenary powers of the SNC do not extend to the exercise of governmental (legislative, executive and judicial) powers. Rather, its powers are limited to giving the country an acceptable constitutional foundation. This will lead to a consideration of the normative theory of post-sovereign constitution-making or the round-table model advanced by Arato.Footnote 145

The model seeks to synthesise the best features of the two main democratic models of constitution-making via constitutional convention and constituent assembly.Footnote 146 The round-table model prescribes a two-level process whereby an interim Constitution that binds the constitution makers is first made before the final Constitution is ultimately made. A constitutional court is also establishedFootnote 147 to ensure the makers of the final Constitution comply with all rules and procedures prescribed in the interim constitution.Footnote 148

While the makers of the interim Constitution may be undemocratically constituted, the makers of the final Constitution must be democratically determined. The latter assembly, like the first, is also not sovereign.Footnote 149 This model emerged from constitution-making experiences of Spain between 1975 and 1977, some countries of Central Europe between 1989 and 1990, and South Africa from 1991 to 1996.Footnote 150

The model, according to Arato,Footnote 151 is noted for ‘substituting principles like pluralistic inclusion of the main political forces, publicity and adherence to the rule of law’ to solve the problem of democratic legitimacy.Footnote 152 Indeed, important principles to observe in any legitimate democratic constitution making process have been identified as consensus, plurality of democracies, publicity, reflexivity and the veil of ignorance.Footnote 153

The round-table model may obviously not apply completely to the Nigerian situation. However, borrowing from its principles and those of the constituent assembly model may prove useful. As previously discussed, it is not going to be a mean feat for a government under the current constitution to agree to the convening of the SNC. Assuming that the combination of factors such as political will and the confidence of the government to have a big say in the deliberations of the SNC make the government willing to commence the process of making a new constitution, it is most likely that it, and not another government, would desire to go down in history as the one that fulfils the long-standing desire for a truly autochthonous and legitimate constitution.

Conceptually, therefore, it makes sense to regard the current constitution as an interim one, so the next stage for the commencement of the final constitution can be commenced. Indeed, the conclusion of the CDCC that a fair reading of the signals coming from a generality of the Nigerian people is a total rejection of the 1995 Constitution in preference for the 1979 Constitution (with amendments) should have at best been taken as tentative. It should have been understood as a recommendation for a kind of stop-gap constitutional arrangement to ease out the military and successfully transit to civilian rule.Footnote 154

The constitutional document emerging from such an arrangement should thus have at best been an interim one. Such a provisional Constitution, according to Milan Petrović,Footnote 155 gives the state ‘the legal organization it needs and, on the other, the question of legitimacy of the constitution is put off until the proclamation of the intended, full constitution’. Thus, taken that the CFRN 1999 is an interim constitution, the government can simply amend it to provide for the convening of the SNC within a reasonable timeline and the expiration of this constitution upon the ratification of a new one by the people of Nigeria at a referendum.

However, the SNC – unlike the latter assembly of the round-table model – must be autonomous and, unlike the assembly under the constituent assembly model, it must not be vested with powers beyond that of making a new constitution. As contended by Ebeku,Footnote 156 such a democratic and all-inclusive conference is ironicallyFootnote 157 a recipe to avoid disintegration by ensuring that all issues confronting the health of the political union are robustly discussed and resolved in the national interest.

A legitimate constitution is therefore one with which the people for whom it is made identify; one they recognise as their own, and to which they have a sense of obligation to not only conform with its norms but to also cherish and defend. Certainly, not one that even the political actors trample uponFootnote 158 and only selectively decide the part to enforce in particular circumstances. The making of such a constitution forms the basis upon which a reasonable expectation of the good governance of the state can be based. The essence of this position is captured in the following words by Ilufoye Ogundiya:Footnote 159

The state that has been under the control of corrupt civilians and military rulers who had fed ferociously on the economy and resources of the state with reckless abandonment cannot enjoy the support of the people. The consequence is glaring-poverty of legitimacy.

VII. Conclusion

This article has adopted a theoretical and pragmatic approach in revisiting the legitimacy crisis facing the Nigerian 1999 Constitution. The contention in doing this is that a rigorous application of theoretical perspectives is necessary in considering the issue of constitutional legitimacy and in demonstrating the consequence of a constitution that is low on the legitimacy spectrum regarding the ‘health’ of the polity.

While locating the essence of the discourse in the country’s historical facts and plural nature as activated by ethnic divisions and tensions, it becomes obvious that a legitimate constitution in such a climate must be one to which there is general agreement, one that is people driven and inclusive. The non-democratic and non-participatory nature of the process adopted in making the CFRN 1999 has indeed been its bane, and it does not seem that it will ever overcome its legitimacy crisis despite the frenzied attempts to amend it by the political class.

Buying into the claims of the consent basis of the discourse on constitutional legitimacy, a legitimate constitution that will meet the yearnings of the Nigerian peoples may surely be made by adapting principles of the constituent assembly model and the round-table model. Based on this, the CFRN 1999 is considered an interim constitution made specifically for the purpose of enabling Nigeria to transit from military rule to civilian rule. This satisfies the first stage of the round-table model.

Recognising the pouvoir constituent that inheres in the Nigerian people, the next stage would be the amendment of the constitution to permit the convening of the SNC for the making of a new constitution. The SNC – contrary to the second assembly of the round-table model – should, however, be autonomous. Although this syncs with the constituent assembly model, it does not totally conform to it, as the SNC may not exercise plenary governmental powers. Its autonomy relates only to the making of a new constitution subject to ratification by the people at a referendum based on universal adult suffrage.

Acknowledgements

The main material for this article derives from the author’s doctoral thesis at Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria. The author wishes to thank the editors of Global Constitutionalism, Professor Michelo Hansungule and the anonymous reviewers for their highly valuable comments on the successive drafts of the article.

Competing Interest

The author(s) declare none.