For much of the 4th millennium bc, people in Ireland and Britain used monuments and material culture with a clear continental ancestry, but exclusively insular interregional traditions were also developed. Among these was Grooved Ware, a ceramic originating on the Orkney Islands c. 3200 cal bc (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010; MacSween et al. Reference MacSween, Hunter, Sheridan, Bond, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2015; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, MacSween, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016). This was a defining aspect of a series of cultural innovations, including distinctive material culture and monumental architecture, which subsequently spread southwards across Britain and Ireland (Bradley 2007, 116; Thomas Reference Thomas2010). While the exact currency of this ceramic in Ireland remains unclear, it is generally accepted that it was not adopted until c. 3000/2900 cal bc (Brindley Reference Brindley1999a; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 31, see below), some centuries after its first appearances in Orkney, or mainland Scotland, but around the same time as in southern England (Garwood Reference Garwood1999, 152). In Ireland, Grooved Ware occurs in a restricted set of contexts, including pits, spreads, timber circles, and developed passage tombs. It has been recovered from deposits within the chambers and outside the entrances of these megalithic monuments, in what have been treated predominantly as secondary contexts. It is the timing and character of the Grooved Ware activity at developed passage tombs which forms the focus of this paper.

While simple passage tombs – such as those at Carrowmore, Co. Sligo or Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow – were in use from at least 3750 cal bc (see Bergh & Hensey Reference Bergh and Hensey2013a; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, McClatchie, Sheridan, McLaughlin, Barratt and Whitehouse2017b), larger, more elaborate forms, known as developed tombs, began to be built later in Ireland, as well as Anglesey and Orkney. Epitomised by the Orcadian Maeshowe-type and the mega-constructions at Dowth, Knowth, and Newgrange in the Boyne Valley, these developed tombs have larger mounds, longer passages, and far more complex internal architecture than their simple forbearers. Recent dating of human bone from Quanterness in Orkney revealed that the primary use of the Maeshowe-type passage tomb seems to date from sometime between 3400 and 3100 calbc (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010). Similarly, recent dating of human bone from developed passage tombs in Ireland in conjunction with Bayesian modelling of the available radiocarbon evidence suggests that the zenith of their construction and use occurred broadly from 3200–2900 calbc . This includes a comprehensive programme of radiocarbon dating of bone from Knowth in Brú na Bóinne (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a) and the Mound of the Hostages, Tara, Co. Meath (Bayliss & O’Sullivan Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013). The recently published dates from Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo corroborate this (Hensey et al. Reference Hensey, Meehan, Dowd and Moore2013; Kador et al. Reference Kador, Geber, Hensey, Meehan and Moore2015), though an earlier date range is represented by currently unpublished data (Robert Hensey pers. comm.). The small number of recently obtained dates from human bone from Cairns F and G at Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo also corroborates this (Hensey et al. Reference Hensey, Meehan, Dowd and Moore2013; Kador et al. Reference Kador, Geber, Hensey, Meehan and Moore2015), though the chronologies of these two sites require further investigation (Robert Hensey pers. comm.).

Chronologies for the period 3300–2700 bc are quite poor, thereby making it difficult to separate between earlier and later events. This is partly due to the inherent imprecision in all radiocarbon dates covering the periods 3100–2930 and 2850–2650 calbc caused by the plateaux within the calibration curve around 4400 and 4200 bp (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1998; Brindley Reference Brindley1999a, 30), but it is also reflective of the need for more targeted dating. However, the results of recent radiocarbon dating and Bayesian modelling are remedying this situation. These new dates are synthesised here to clarify our understanding of the temporality of changes in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia bc, but are not critically evaluated because they have already been subject to systematic assessments which are clearly cited within the text. Unfortunately, constructing a precise radiocarbon chronology for the period is far beyond the scope of the current paper. Instead, broad trends in social practice are identified and assessed to better understand the nature of change at this time.

This paper examines the nature of the relationship between developed passage tomb-associated activity and the adoption and use of Orcadian material culture, including Grooved Ware in Ireland between 3300 and 2450bc (from the peak of passage tomb construction until Grooved Ware was replaced by Beaker pottery in Ireland). It is argued that these innovations were incorporated into the Irish passage tomb tradition throughout the floruit of the developed tombs. This occurred during a sustained period of contact with northern Britain which saw the partial convergence of practices associated with these monuments in the Boyne Valley area and Orkney. The realisation that this interaction network strongly influenced the development of the Grooved Ware phenomenon has major implications for understanding its effect upon the use of passage tombs. Traditionally seen as heralding large-scale social transformation, including the cessation of passage tomb activity, it is argued here that evidence for such major changes is lacking, and there is strong evidence for the continuation of the ceremonial practices associated with these tombs. Based on this, it is observed that current chronological frameworks impede our understanding of the complexity of social developments at this time by creating an artificial division between the late 4th and early 3rd millennia.

A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY

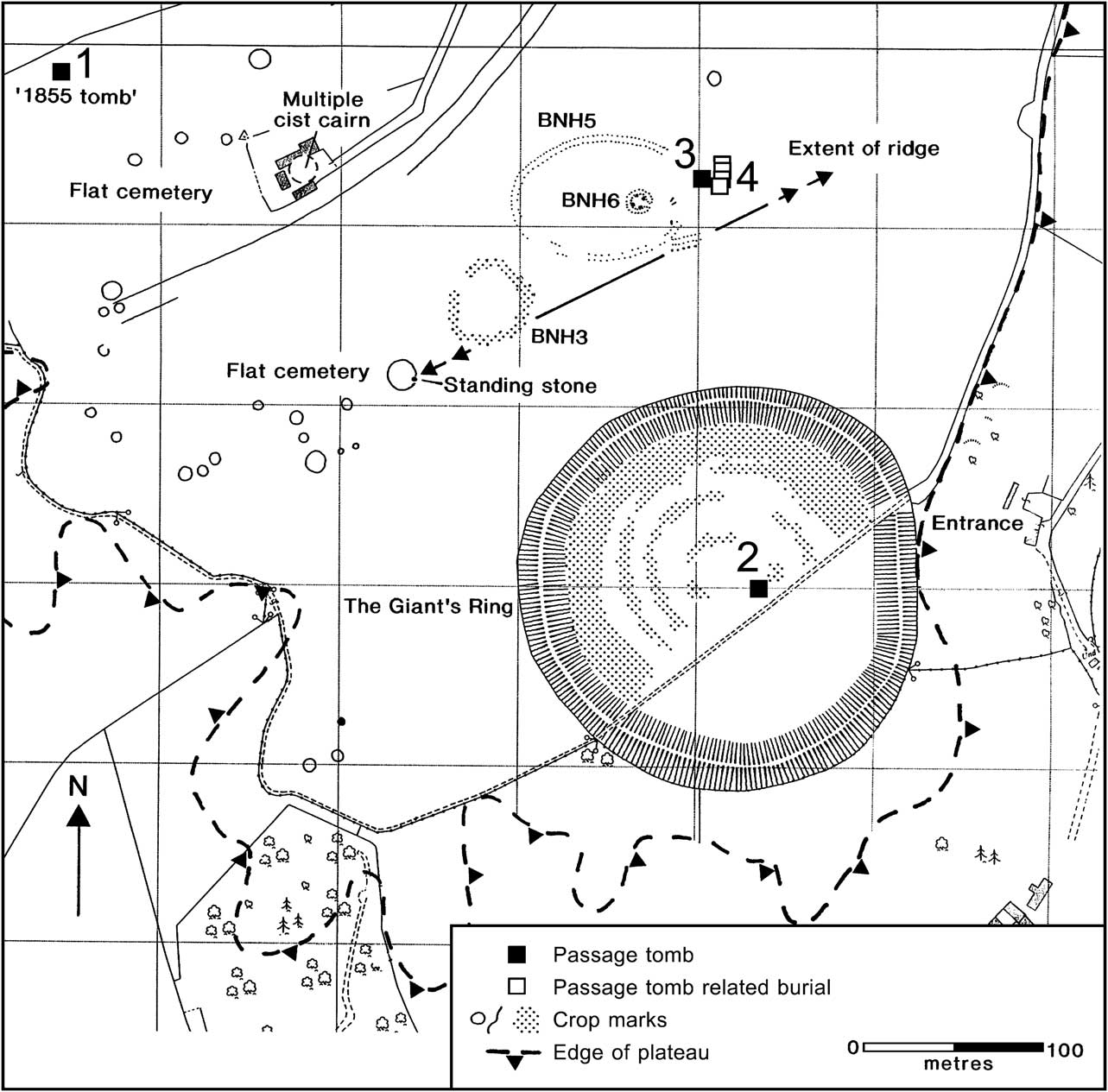

Before examining the relationship between the use of passage tombs and the adoption of Grooved Ware in Ireland, it is necessary to appraise briefly the development of the current view that the arrival of this ceramic marked the decline of passage tomb activity and the beginning of a new phase of the Neolithic. Although Grooved Ware was occasionally noted in Ireland throughout the latter half of the 20th century (eg, Ó Ríordáin Reference Ó Ríordáin1951; Liversage Reference Liversage1968; O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Lynch and O’Kelly1978; Cleary Reference Cleary1983, 63; Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 313; Sweetman Reference Sweetman1985), it was only recently that this ceramic began to be more widely identified from sites across the island, many of which were located within the passage tomb complexes of Brú na Bóinne (Roche Reference Roche1995; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995; Brindley Reference Brindley1999a). Arguably, this breakthrough can be largely attributed to the discovery in the early 1990s of Grooved Ware-associated timber circles beside passage tombs at both Ballynahatty, in the Lagan Valley, Co. Down (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998) and at Knowth (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997) in Brú na Bóinne (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Map of Ireland showing key sites mentioned in the text. Inset shows Brú na Bóinne in relation to north-western Britain and the islands of Orkney

Initially, it was widely regarded that the development of Grooved Ware in Ireland was strongly related to the Irish developed passage tomb tradition (eg, Cleal Reference Cleal1999, 6–7; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1999, 109–11; Bradley Reference Bradley1997; Reference Bradley1998; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 167–8). Strong relations between people using passage tombs in Brú na Bóinne and Orkney had long been recognised (eg, Piggott Reference Piggott1954, 219; Bradley & Chapman Reference Bradley and Chapman1984; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986; Reference Sheridan2004a). The passage tomb context of these new discoveries of timber monuments and Grooved Ware seemed to echo the evident connection between the use of Maeshowe-type tombs and this ceramic, which is characteristically associated with these megaliths (Bradley Reference Bradley1984; Davidson & Henshall Reference Davidson and Henshall1989, 64, 77–82; Richards Reference Richards2005; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010). However, Quanterness, Quoyness, and the probable example at Pierowall are the only such tombs where it has been found (Childe Reference Childe1954; Henshall Reference Henshall1979; Sharples Reference Sharples1984). Grooved Ware occurred within the main chamber at the former, but on external platforms at the latter two sites and does not seem to be associated with the earliest stages of activity at any of them (Cowie & MacSween Reference Cowie and MacSween1999, 52). Nevertheless, the cruciform arrangement of space (with a greater emphasis on the right-hand side – as one enters the tomb) and highly defined entrances of these tombs is very similar to that of Orcadian Grooved Ware-associated dwellings such as those at Barnhouse dating from c. 3200–2800 calbc (Richards Reference Richards1993; Reference Richards2005; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2004; Reference Ashmore2005; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010).

The relatedness of the Irish passage tomb tradition and Grooved Ware was subsequently thrown into doubt by the results of the excavation and dating of the two Grooved Ware-associated timber circles at Ballynahatty and Knowth, which revealed that their construction post-dated passage tomb-related activity. These findings resulted in the assumption that most, if not all, Grooved Ware in Ireland was associated with wide-ranging social transformations, including the decline of the passage tomb complex, decreased emphasis on mortuary practices, increased collective gathering and feasting, and the construction of open-air ceremonial circular structures in the form of timber circles and possibly also embanked enclosures (Bradley Reference Bradley1998, 101–31; Cooney & Grogan Reference Cooney and Grogan1999, 87–92; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1999, 108–9; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 167–73). Accordingly, Grooved Ware and much of the evidence for links between Brú na Bóinne and Orkney was assigned to (what was for Ireland, at least) a newly created post-passage tomb period known as the Late Neolithic (eg, Simpson Reference Simpson1996, 69 & 74; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997, 220; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 18). In retrospect, the imposition of a chronological segregation between developments before and after 3000 calbc greatly hampered subsequent understandings of developments in Ireland between 3200 and 2700 calbc.

ORKNEY AND BRÚ NA BÓINNE: A SPHERE OF MUTUAL INFLUENCE 3300–2900 CAL BC

The key to understanding the relationship between the use of passage tombs and the adoption of Grooved Ware in Ireland may lie in the interactions between those who built and used these related monuments in Brú na Bóinne and Orkney during the late 4th and early 3rd millennia, when this was the main ceramic used by Orcadians.

The similarities between the developed passage tombs in Orkney and Ireland suggest that there were strong connections between these islands at this time (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986; Reference Sheridan2004, 16–17; Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 35; Eogan Reference Eogan1992; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 156; Bradley 2007, 117–18; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010). In common with other European passage tombs, the spatial arrangement of these Orcadian and Irish tombs was structured along a central axis running from the entrance to the rear (Dehn & Hansen Reference Dehn and Hansen2006; Hensey Reference Hensey2015), and megalithic art was used to highlight major architectural junctions (Robin Reference Robin2010). The Maeshowe tombs also share features that are highly typical of developed Irish passage tombs, such as a cruciform layout of chambers (with a larger right-hand recess) accessed via a long, narrow, highly defined passage. Notably, the later Orcadian and Boyne tombs both comprise large, highly visible, elliptical covering mounds of complex construction with flattened fronts. The passages of the tombs at Newgrange and Maeshowe – both of which terminate in a corbelled cruciform-shaped chamber – are broadly aligned on the midwinter solstice; the former faces southeast towards the sunrise (O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 123–5) while the latter is orientated southwest towards the sunset (Davidson & Henshall Reference Davidson and Henshall1989). This is also known at seven other Irish passage tombs (Prendergast Reference Prendergast2011), including Knockroe, Co. Kilkenny, where one of each of the two passages forming the tomb were aligned on the midwinter sunrise and sunset (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2004).

This interconnectedness is further demonstrated by the occurrence of miniature and full-size Orcadian-influenced objects, such as carved stone balls and ovoid or pestle-shaped stone maceheads, in primary contexts inside and outside Irish developed passage tombs, along with the traditional repertoire of artefacts commonly found in these megaliths, including pendants, pins, and smooth stone balls (Simpson Reference Simpson1988; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a & Reference Sheridanb; 2014). This is exemplified at Knowth, where two fragmented stone maceheads were found within the eastern and western tombs beneath the main mound.

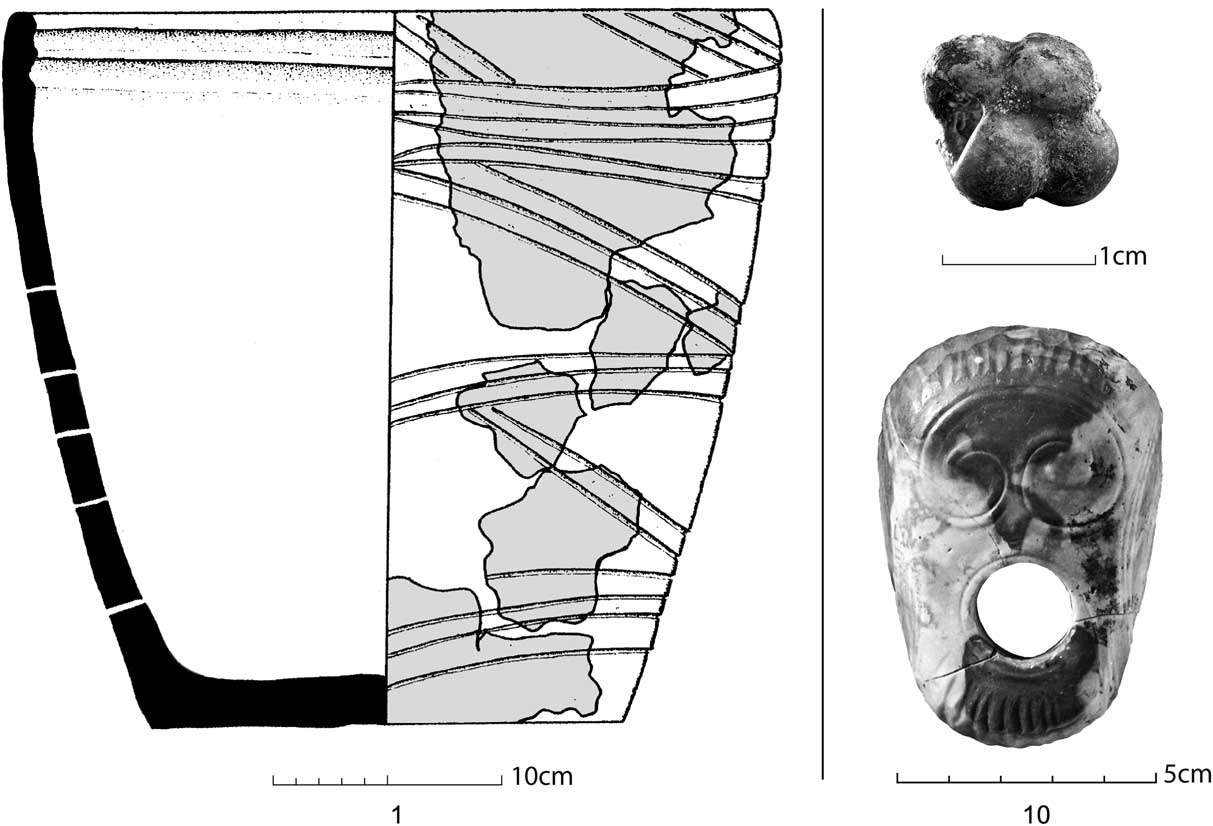

An ovoid ‘Maesmawr’ type flint macehead was found within the right-hand recess of the eastern passage tomb which seems to have been broken before deposition (Eogan & Richardson Reference Eogan and Richardson1982, 124; see Figs 2 & 3). It was decorated with spectacle spiral motifs suggesting that it may have been made somewhere in Northern Britain or Orkney (Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 29; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 32; Reference Sheridan2004b, 17). Although previously suspected to have been a Late Neolithic secondary insertion into the tomb (eg, Simpson Reference Simpson1996, 69; Brindley Reference Brindley1999b; 143; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 129), it was found in a primary context on the chamber floor covered by a layer of shale stratified beneath six other deposits (Eogan & Richardson Reference Eogan and Richardson1982, 123–4; Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 43 & 40, fig. 20). Two of these overlying deposits contained two fragmented stone beads (Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 41, fig. 21, nos 13 & 14). Sheridan (Reference Sheridan2014) identified these as miniature versions of the 6-knobbed stone balls that are mainly found in Aberdeenshire and Orkney (Marshall’s Reference Marshall1977 type 4B, see Fig. 3) (further examples are discussed below). Recently obtained radiocarbon dates from these layers indicate that both the macehead and the miniature balls were deposited sometime before 3090 calbc (Sheridan Reference Sheridan2014; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a).

Fig. 2 Plan of the passage tomb complex at Knowth (after Eogan & Cleary Reference Eogan and Cleary2017, reproduced with permission). The numbers in bold show the spatial location of the maceheads, human bone dating from 3000–2450 cal bc, and Grooved Ware at Knowth: (1) vessel in tomb 6; (2) burial in tomb 15; (3) concentration A; (4) burial inside tomb 17; (5) vessel in tomb 18; (6) timber circle; (7) concentration C; (8) burial inside tomb 1C West; (9) pestle-shaped macehead; (10) Maesmawr macehead & knobbed bead

Fig. 3 Knowth’s Orcadian-style objects from Locations 1 and 10 in Fig. 2: highly decorated Grooved Ware pot (after Eogan Reference Eogan1984, fig. 116); complete miniature carved stone ball bead (photo by K. Williams for Eogan & Cleary Reference Eogan and Cleary2017, reproduced with permission); and ovoid ‘Maesmawr’ type flint macehead (after Eogan & Richardson Reference Eogan and Richardson1982, fig. 45)

The second Knowth macehead comprises two fragments of a burnt pestle-shaped example from the chamber of the western tomb (Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 44; Kerri Cleary pers. comm.). Significantly, both this and the ‘Maesmawr’ example were broken across their perforation, as is frequently the case in Orkney (Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 31; Simpson & Ransom Reference Simpson and Ransom1992; Sheridan & Brophy Reference Sheridan and Brophy2012). Two further pestle-shaped maceheads have also been found in the townlands of Dowth and Monknewtown within Brú na Bóinne (Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 37).

The only other macehead from an archaeological context in Ireland was a pestle-shaped example found in an oval stone setting of late 4th millennium date at the Eagles Nest stone axe quarry site on Lambay Island, off the coast of Dublin. The resemblance of this setting to the small sub-circular arrangements of stones outside the entrances to the large tombs at Knowth and Newgrange (see below) underlines the strong connection between the deposition of these Orcadian style maceheads and the developed passage tomb tradition (Cooney Reference Cooney2009, 14 & 16; Gabriel Cooney pers. comm.).

Excavations at the Eagles Nest also uncovered a number of miniature maceheads made from jasper, one of which was found in direct contextual association with Carrowkeel Ware, an Irish variant of Impressed Ware dating from c. 3300–2900 calbc (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005; Grogan & Roche Reference Grogan and Roche2010). Such pendants seem to represent scaled-down versions of the pestle and ovoid shaped maceheads of Northern Britain (Piggott Reference Piggott1954, 220; Herity Reference Herity1974, 126–9; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986; Reference Sheridan2004a). These have also been found in association with Carrowkeel Ware in passage tombs such as Loughcrew cairn R2 and Fourknocks I, Co. Meath; Carrowkeel cairn K, Co. Sligo (Herity Reference Herity1974, 285, 287, 290; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 28); and within primary contexts in the tombs at Knowth, Newgrange, and the Mound of the Hostages (eg, O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 192, fig. 59; Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 41, fig. 21; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 149, fig. 122) (see Fig. 7). At the latter tomb, pendants and complete Carrowkeel ware pots were found within a sealed context in Cist III in association with cremated bone dating from 3220–3020 calbc (GrA-17747, 4530±60 bp; Bayliss & O’Sullivan Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013). From this, it is clear that the deposition of these miniature maceheads formed part of a wider set of practices associated with the Irish developed passage tomb tradition which referenced Orkney and Scotland.

Apart from the diminutive knobbed stone beads from Knowth, Sheridan (Reference Sheridan2014) highlights two other potential examples of knobbed beads/pendants from Knowth and Mound of the Hostages which may also be miniature versions of Scottish stone balls. To date, only two full-sized carved balls have been found in Ireland: an uncontexted 6-knobbed example from Ballymena, Co. Antrim (Marshall Reference Marshall1977, 68; Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 31) and another recently confirmed example of incised sandstone found during the excavation of a late prehistoric enclosure on the Hill of Uisneach, Co. Westmeath (Macalister & Praegar Reference Macalister and Praeger1928–9, 117, pl. xvii, fig. 2; Childe Reference Childe1931, 103; Donaghy & Grogan Reference Donaghy and Grogan1997) (see Fig. 4).Footnote 1 Furthermore, it has also been suggested that the Scottish carved stone spheres may have been inspired by the smooth stone balls which are a persistent aspect of the Irish passage tomb repertoire (Piggott Reference Piggott1954; Sheridan & Brophy Reference Sheridan and Brophy2012, 84; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2014). The Irish smooth stone balls occur in two distinct sizes: 11–25 mm or 70–80 mm in diameter. Most are smaller marble-like examples which have frequently been found in passage tombs of all form and scales, often in association with pins. Based upon the radiocarbon dating of 25 calcined bone and red deer antler pins from apparently primary contexts in two passage tombs at Carrowmore to 3650–3100 calbc (Bergh & Hensey Reference Bergh and Hensey2013a), it is likely that at least some of the small balls share the same date range. These may even represent precursors of the larger examples which are only known from developed tombs such as Cairn F and Cairn L at Loughcrew and Fourknocks, Co. Meath (Herity Reference Herity1974, 136; O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 195; Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 144) (see Fig. 5). These larger spheres are highly comparable to the similarly sized, smooth, carved stone balls found at Orcadian Grooved Ware sites: Skara Brae, Rinyo, and more recently at Ness of Brodgar, Barnhouse, and Wideford Hill (Childe Reference Childe1931, 100–1; Piggott Reference Piggott1954, 332; Card Reference Card2013; cf Sheridan Reference Sheridan2014; Clarke Reference Clarke2015, 456). Collectively, these various balls seem to reflect Scottish-Irish passage tomb related interactions.

Fig. 4 Carved stone ball from unknown context on the Hill of Uisneach, Co. Westmeath (photo by N. Carlin with permission from the National Museum of Ireland)

Fig. 5 Polished stone balls (with diameters of 78 mm & 67 mm) from Cairn F and Cairn L, Loughcrew, Co. Meath (after Herity Reference Herity1974, fig. 98)

The affinity between the Boyne Valley and Orkney also seems to be reflected by the occurrence of particular motifs from the developed passage tomb tradition on various forms of Grooved Ware-related material culture (Shee Twohig Reference Shee Twohig1981; Saville Reference Saville1994; Ritchie Reference Ritchie1995; Brindley Reference Brindley1999b, 134–8; Shepherd Reference Shepherd2000; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Phillips, Richards and Webb2001, 56, 63; Bradley 2007, 116–17; Thomas Reference Thomas2010; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Díaz-Guardamino and Crellin2016). Occasionally, spiral motifs were translated to other media, the most well-known example of which is the Maesmawr macehead found in a late 4th millennium context at Knowth. The decoration of this object strongly echoes the opposed spirals carved onto the structural stones from probable Maeshowe-type passage tombs in Orkney such as Pierowall, Westray, and Eday Manse, Eday (Shee Twohig Reference Shee Twohig1997, 383; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a). These carvings are also replicated to a lesser extent on the antler macehead from Garboldisham, Suffolk (Edwardson Reference Edwardson1965), which was recently confirmed through radiocarbon dating by Jones and colleagues (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Díaz-Guardamino, Gibson and Cox2017) to be of very similar date to the Knowth macehead. Spirals (and lozenge-mesh faceting) resembling those on the Knowth example have also been found on Grooved Ware bowls in a pit at Barrow Hills, Radley, Oxfordshire, though these apparently post-date 2600 calbc (Cleal Reference Cleal1991; Reference Cleal1999; Barclay Reference Barclay1999, 19–20).

Similar spiral motifs also occur on carved stone balls such as the highly decorated example from Towie, Aberdeenshire (which also has facetted decoration) (Kinnes Reference Kinnes1995; Longworth Reference Longworth1999). The spiral and lozenge decorated sherd from Skara Brae in Orkney (Piggott Reference Piggott1954, pl. 12.4) is highly comparable to the motifs occurring on Kerbstone 67 at Newgrange (Brindley Reference Brindley1999b, 136) and at Barclodiad Y Gawres, North Wales which is also part of the Irish developed passage tomb tradition (Shee Twohig Reference Shee Twohig1981). Similarly, the single spiral decorating the upper portions of the basin stone from the right hand recess of the eastern chamber from Knowth (Eogan Reference Eogan1986, pl. vi; Brindley Reference Brindley1999b, 136) is very like that on Grooved Ware from Durrington Walls, Wiltshire and Wyke Down henge, Dorset (Wainwright & Longworth Reference Wainwright and Longworth1971, 246; Cleal Reference Cleal1991, 144, fig. 7.17; Kinnes Reference Kinnes1995, 51).

Far more common than this was the transference of the stylistically earlier, internal, angular megalithic art of Brú na Bóinne onto a range of Grooved Ware-associated cruciform-shaped structures and monuments, as well as objects in Orkney and beyond, including pottery, stone plaques, carved stone balls, and Skaill knives. These motifs, comprising incised and pecked motifs such as triangles, zigzags, chevrons, and lozenges, were current around the time that developed passage tombs were being built c. 3300–3000 calbc, but largely pre-dated the ‘plastic’ style of art, including pick dressing which was carved in situ, sometime after their construction (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan1986; Reference O’Sullivan1989; Reference O’Sullivan1996; Reference O’Sullivan1997; Eogan Reference Eogan1997; Reference Eogan1999; Brindley Reference Brindley1999b, 136; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Phillips, Richards and Webb2001, 63). These angular carvings have their ultimate origins on the continent (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan1997; Reference O’Sullivan2006) and belong to a wider body of European passage tomb art.

Robin (Reference Robin2008; Reference Robin2010) has labelled these as ‘threshold motifs’ because of their occurrence at significant architectural spaces such as thresholds, lintels, corbels, and backstones. He argues that the art and architectural features combine to demarcate important junctions along a passage to or from the backstone which itself symbolises a doorway to another world (Robin Reference Robin2012). These ‘threshold motifs’ also occur within the Boyne- and Maeshowe-type passage tombs (Eogan Reference Eogan1986; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Phillips, Richards and Webb2001; Bradley 2007, 108 & 116–17; Robin Reference Robin2008), as well as the Orcadian stone-built dwellings at Skara Brae, Barnhouse, and Ness of Brodgar, shared similar spatial arrangements to these tombs (Shee Twohig Reference Shee Twohig1981, 238–9; Richards Reference Richards1991; Reference Richards1996; Reference Richards1998; Shepherd Reference Shepherd2000; Bradley Reference Bradley1997; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Phillips, Richards and Webb2001; Bradley 2007, 108, 112, 119; Card & Thomas Reference Card and Thomas2012; Robin Reference Robin2012).

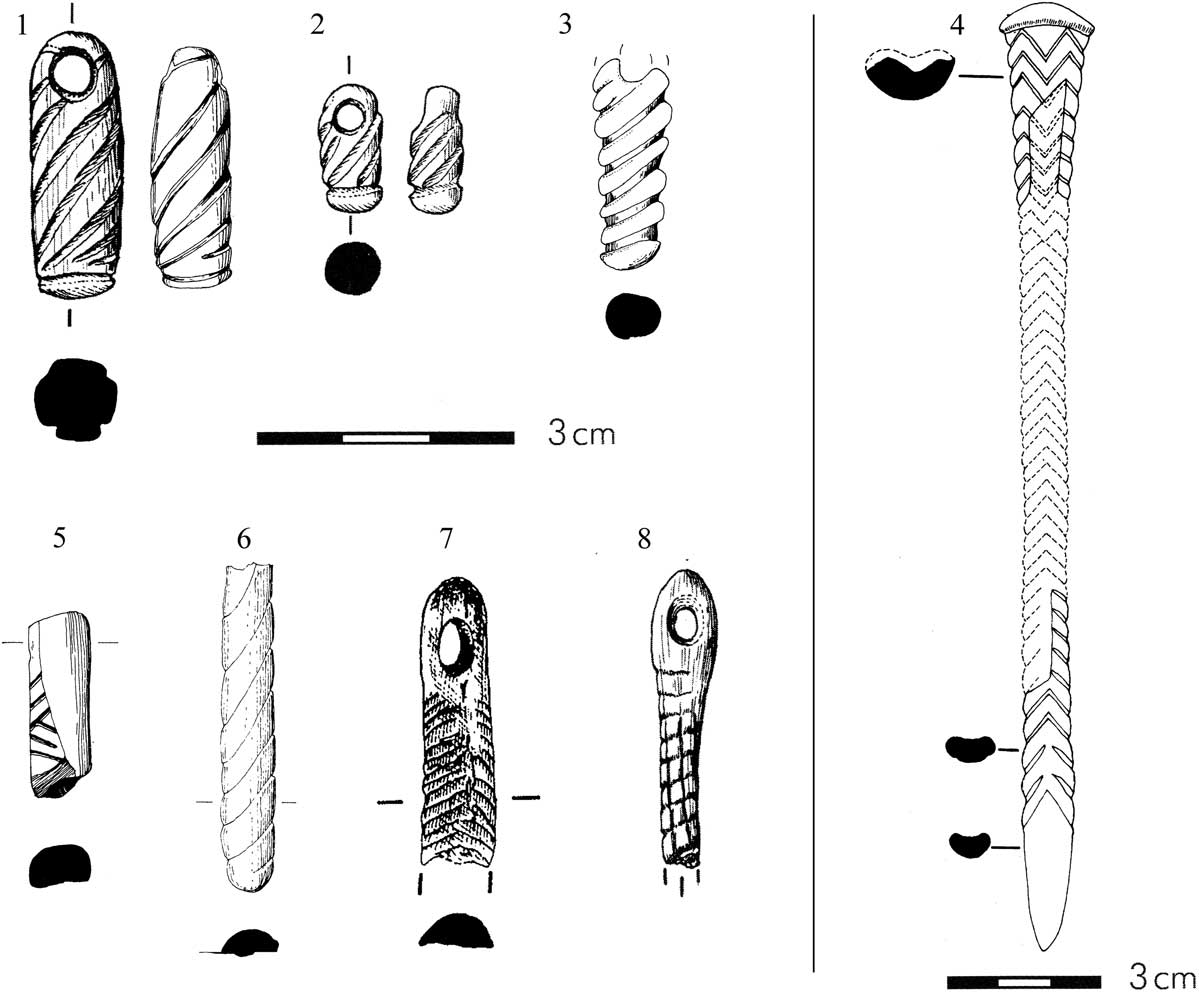

This geometric artwork was also used to decorate portable objects from Irish passage tombs (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2009, 26) (Figs 6 & 7). While some of these pieces have been compared to decorated objects from the Lisbon region in Portugal (eg, Eogan Reference Eogan1990; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2014), the practice of incising objects with megalithic motifs, predominantly ‘threshold signs’, was a recurrent aspect of the developed Irish passage tomb tradition. A notable example of this is the burnt fragmentary antler/bone pin which was decorated with incised chevrons and found within the cremations at Fourknocks I, Co. Meath (Hartnett Reference Hartnett1957, 203, 242). This is very like a burnt bone pin from Knockroe (Muiris O’Sullivan pers. comm.) and a pin fragment from Carrowmore tomb 27, Co. Sligo, which were both decorated with incised chevrons (Fig. 5). Another similar antler/bone pin was found in a similar condition with a cremation deposit in the chamber of Knowth Tomb 3 (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 28–9). It was decorated with incised zig-zags like those on a grooved sandstone conical object found in the Knowth Site 1 mound, near the western tomb’s entrance (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 163). Both of these echo the carved rows of parallel lines occurring on orthostats at thresholds in Newgrange and other passage tombs (Robin Reference Robin2008) (Fig. 6). The motif on the Knowth 3 pin is also comparable to the carved pestle macehead pendants from the Mound of the Hostages and Carrowkeel Cairn G which are similarly decorated with incised spiral grooves (Herity Reference Herity1974, 126) (Fig. 7.1–3). Incised geometric art also occurs on three bone pendants from Loughcrew Cairn R2 and Cairn S, as well as the Mound of the Hostages, the latter of which displays square-shaped patterns comparable to the lozenge-mesh faceting on the Maesmawr macehead from Knowth and others of this type (Roe Reference Roe1968, 149) (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 6 The sandstone conical object (220 mm long) and the antler/bone pin (200 mm long) from Knowth 1 and 3, both displaying incised motifs comparable to megalithic ‘threshold signs’ (photo by K. Williams for Eogan & Cleary Reference Eogan and Cleary2017, reproduced with permission)

Fig. 7 Pendants and pins with incised geometric artwork from Irish passage tombs: pestle macehead pendants with incised spiral grooves from the Mound of the Hostages (1 & 2) and Carrowkeel Cairn G (3); antler/bone pins with incised chevrons from Fourknocks I which is 190 mm long (4) and Carrowmore tomb 27 (5); incised bone pendants from Loughcrew Cairn R2 (6) and Cairn S (7) and Mound of the Hostages (8) (after Herity Reference Herity1974, fig. 97; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, fig. 122)

In a significant contrast to their counterparts in Orkney and other parts of Britain, objects sharing these megalithic art motifs in Ireland were almost exclusively confined to passage tomb contexts. This may be explained by observations made by Thomas (Reference Thomas2010) and Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Phillips, Richards and Webb2001, 64) that megalithic motifs in Ireland were predominantly associated with the passage of the dead to another world, but the transmission of these symbols to Orkney saw them being translocated into everyday contexts associated with the living. Consistent with this is the fact that Grooved Ware was predominantly deposited there in non-passage tomb contexts, particularly settlements from a very early stage, unlike Ireland where it was largely confined to passage tomb contexts until c. 2750 calbc (see below). Similarly, despite the strong associations between Grooved Ware and passage tombs in Ireland, notably few vessels displaying passage tomb-inspired designs have been found in Ireland compared to Britain.Footnote 2 Rare examples include the well-known Grooved Ware pot from a passage tomb at Knowth (see below) and two other vessels from a pit at Coole, Co. Cork (Cleary Reference Cleary2015) and a timber-circle-like structure at Slieve Breagh, Co. Meath (de Paor & Ó h-Eochaidhe Reference de Paor and Ó h-Eochaidhe1956), all of which displayed incised decorations comprising zigzags and lozenges (Brindley Reference Brindley2008; Reference Brindley2015) (Figs 3 & 8). Notably, two of these are from non-passage tomb settings suggesting that in exceptional circumstances, megalithic incised or angular artwork was also translated onto Grooved Ware-associated material culture in contexts associated with the living in Ireland. Another rare example of this is provided by the recent discovery at Ballynacarriga, Co. Tipperary, of an unusual carved stone object displaying vertical and oblique grooving. This was found alongside Grooved Ware sherds in the post-hole of a four-post structure dating to around the mid-3rd millennium, representing the remnants of a timber circle-like building which probably fulfilled a range of residential and ritual functions (Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin and Cooney2017; Johnston & Carlin forthcoming).

Fig. 8 The Grooved Ware vessel from a pit at Coole, Co. Cork decorated with nested lozenge designs which echo the motifs found in the Brú na Bóinne passage tombs and on Grooved Ware from Orkney (after Cleary Reference Cleary2015, fig. 3.4)

Additional differences in the shared material culture and social practices of Ireland and Orkney c. 3300–2900 calbc include the absence of miniaturisation and the dominance of mortuary rites on the interment of whole bodies in passage tombs (Jones Reference Jones2012, 48; Crozier Reference Crozier2016). This contrasts strongly with the tradition of incorporating disarticulated, unburnt human remains, particularly long bones and skulls alongside cremations, as well as complete inhumations in Irish passage tombs (see Cooney Reference Cooney2014; Reference Cooney2017). Cumulatively, all of these similar but different ways of doing things indicate a high level of interaction including the flow of ideas and objects between people in these places. Although Orkney is 450 km from the northern coast of Ireland, seasonal travel between there and the Boyne by paddle boat via Argyll has been shown to have been feasible over a duration of 6 or 7 days (Callaghan & Scarre Reference Callaghan and Scarre2009). Indeed, Sheridan (Reference Sheridan2004a; Reference Sheridan2004b) has highlighted the strong evidence for a chain of connections between Orkney and Brú na Bóinne which stretched along the western fringes of Scotland c. 3000 calbc.

ON THE INSIDE: GROOVED WARE AND OTHER DEPOSITS WITHIN PASSAGE TOMBS 3100–2450 CAL BC

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the strength of these links and the practice of depositing Orcadian-style objects during the primary use of Irish developed passage tombs, Grooved Ware has been found in varying quantities at Knowth, Newgrange, Loughcrew, and Mound of the Hostages. While most of this was found outside of these megaliths, there is a growing body of evidence for Grooved Ware (albeit in only a few instances) from the interior of developed passage tombs. While these deposits largely post-date the floruit of these monuments, they represent the persistence of pre-existing forms of depositional activity. This indicates that the early occurrence of Grooved Ware in Ireland c. 3100–2800 calbc was part of the continuation of the active use of passage tomb interiors by people using this ceramic until c. 2700 calbc. During this time frame, there was a gradual, rather than sudden, decrease in the frequency of passage tomb activity.

At Knowth, Grooved Ware came from recesses within two of the smaller cruciform-shaped passage tombs (6 & 18) which had been badly disturbed (Fig. 2). In the right-hand recess of Tomb 6, sherds forming a highly decorated vessel (Fig. 3) occurred within and around a deposit of cremated and unburnt human bone representing the remains of several individuals, including adults and a child, as well as a bone pestle pendant and a fragment of a spheroid stone bead (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 43, 312, fig. 116). Three recently obtained radiocarbon determinations from the cremated bone of two of the individuals and the unburnt bone of another returned almost identical dates c. 3090–2910 calbc (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a).

Inside the left hand recess of Tomb 18, six sherds forming part of a largely undecorated Grooved Ware (Brindley’s Dundrum-Longstone type/Roche’s Knowth Style 1) pot were found on top of a flagstone along with a rounded scraper, charcoal, animal bones, and an unburnt human skull fragment of unknown date (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 312–13, fig. 118; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 128).Footnote 3 Elsewhere, 19th century antiquarian investigations at Cairn L, Loughcrew, Co. Meath, uncovered pottery, including at least two sherds of Grooved Ware (Dundrum-Longstone type), in an apparently secondary position among the loose stones which filled up the chamber of that tomb (Conwell Reference Conwell1864; Herity Reference Herity1974, figs 139.3, Roche Reference Roche1995; Brindley Reference Brindley1999a, 24).

Previously, the strength of association between the human remains and the Grooved Ware in Knowth Tomb 6 seemed questionable. They were found in a very poorly preserved chamber whose orthostats and capstones had been removed prior to its discovery. They also occurred within a deposit (partially overlain by two early medieval inhumations) which may have been subject to considerable post-depositional disturbance (see Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 41–5). However, the consistency of the dates from the three individuals within the recess suggests that the deposit has some chronological integrity. As highlighted elsewhere (Gibson Reference Gibson1982, 182; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1994, 328; Roche Reference Roche1995; Brindley Reference Brindley1999a, 24; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 30–1; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010, illus. 20), the fragmentary and incomplete Grooved Ware pot from Tomb 6 is stylistically similar to other vessels sharing the same kind of incised decoration from northern Britain, including Barnhouse, Stones of Stenness, and Quanterness and Balfarg henge. Bayesian modelling of the recently obtained dates from these sites indicates that while comparable pots from Barnhouse may pre-date 3100 calbc, those from Stones of Stenness and Quanterness seem to have been current c. 3000/2900 calbc (see Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010, 37, 38 & 40; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jones, MacSween, Sheridan, Dunbar, Reimer, Bayliss, Griffiths and Whittle2016). The close correlation between these dates and those from the bones with which the Tomb 6 vessel was found supports previous suggestions that it was deposited with the bone c. 3000/2900 calbc and represents one of the earliest Grooved Ware pots in Ireland (Brindley Reference Brindley1999a, 31 & Reference Brindley1999b, 138; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 31).

Significantly, this vessel was deposited in combination with both cremated and unburnt bone, a practice observed by Cooney (Reference Cooney2000, 106–24; 2014) to be an intrinsic feature of the Irish passage tomb funerary tradition, as well as artefacts – a pestle pendant and a bead fragment – typifying this. This suggests that this pot and the bone with which it was associated almost certainly represent a Grooved Ware-associated burial in a primary context within an Irish passage tomb during the floruit (3200–2900 calbc) of these monuments at Knowth (contra Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1999, 106; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 167–8; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 137). As highlighted by Schulting et al. (Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a), it is even possible that Grooved Ware-users built the tomb.

Unfortunately, compared to Tomb 6, the chronology of the Grooved Ware-associated deposits within Knowth Tomb 18 and Loughcrew Cairn L are quite fuzzy. However, it is plausible that these also represent primary passage tomb activity. In the case of Tomb 18, it is possible that the human skull fragment was also placed there with Grooved Ware at the start of the 3rd millennium. Sheridan (Reference Sheridan2004a, 31) has observed that the deposition of pottery with more limited ornament (eg, Brindley’s Dundrum-Longstone & Donegore-Duntryleague types/Roche’s Knowth Style 1) like that from these two passage tombs, could have occurred at broadly the same time as at Knowth 6 (contra Brindley Reference Brindley1999a, 31; 1999b, 138). Plainer Grooved Ware resembling these pots is known from a range of sites in northern Britain, including Balfarg, Fife, and Quanterness and the Stones of Stenness, Orkney, where it occurs in conjunction with more highly decorated vessels, such as that from Tomb 6, within contexts dating to c. 3000–2900 calbc (see above; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 27, 35).

During the centuries when Grooved Ware was current in Ireland, unaccompanied deposits of human bone were also placed within the tombs at Carrowkeel and Carrowmore, Co. Sligo; Mound of the Hostages and Knowth, Co. Meath; and Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow in much the same ways as before, presumably by users of this ceramic.

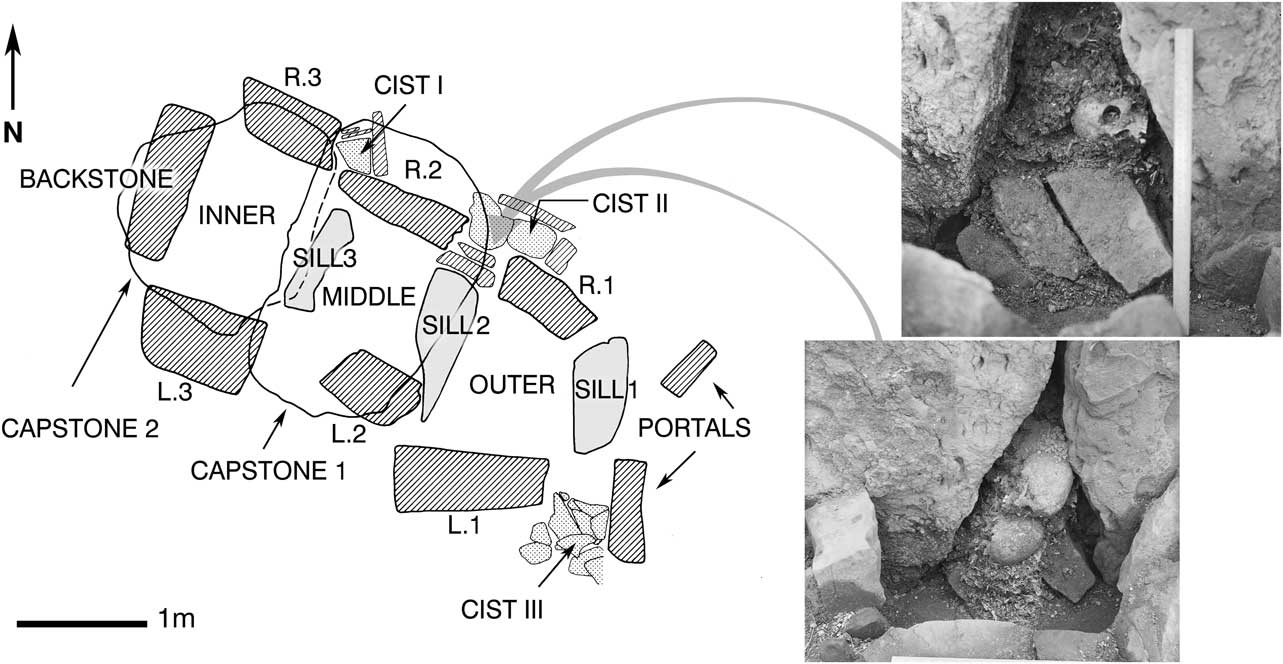

At the Mound of the Hostages passage tomb, both burnt and unburnt human remains continued to be deposited within the monument between 2900 and 2600 BC (Brindley et al. Reference Brindley, Lanting and van der Plicht2005, 286). Three cists (I–III) were added to the exterior of the tomb at some stage after the erection of the orthostats that formed the tomb’s chamber, but before a covering cairn was placed over them (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 68–79; Scarre Reference Scarre2013, 160) (Fig. 9). Cist II was located along the exterior of the tomb beside the junction between the sillstone (S2) separating the outer and middle compartments of the chamber and the orthostats (R1 & R2) forming their northern side. A large gap between these uprights was only partially sealed by smaller stone slabs which divided the external cist from the tomb’s interior, and four unburnt adult skulls were found in this space (Fig. 9). Radiocarbon dates ranging from c. 3100–2500 calbc were obtained from three of these (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 114–16), two of which (Skulls P: GrA-18353 & G: GrA18374) dated from 2870–2470 calbc and 2920–2670 calbc. O’Sullivan (Reference O’Sullivan2005, 225) does not view these as being in a primary context within cist II, but as belonging to a cluster of more than ten unburnt human skulls that were recovered on the right hand side of the tomb’s middle compartment beside the gap between orthostats R1 and R2. This view is supported by the absence of evidence for skulls or any other bones post-dating 2900 calbc within either of the other two pre-cairn cists (I & III). However, this is complicated by the evidence from Cist II.

Fig. 9 Detailed plan of the Mound of the Hostages passage tomb showing Cist II along the exterior of the outer and middle tomb chamber and the location of the skulls dating from 2900–2600 cal bc which are shown in the photos between the orthostats R1 and R2 (after O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, figs 59, 70 & 71)

Cist II contained the cremated remains of at least 34 adults, as well as some unburnt children’s and infant’s bones, and a range of typical Irish passage tomb artefacts such as bone pins and stone balls (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 70–3). A fragment of the cremated bones returned two statistically consistent radiocarbon determinations with a mean date of 2890–2635 calbc (GrA-17272, 4180±35 bp; GrA-17746, 4200±50 bp; Bayliss & O’Sullivan Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013). O’Sullivan (Reference O’Sullivan2005, 71–2) observed that the cremation deposits from this cist probably represent an intact collection from a single depositional event, with minimal contamination from the main tomb. However, Bayliss and O’Sullivan (Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013, 43) regard the dated sample as intrusive material representing a secondary episode of deposition post-dating the main use of the passage tomb, which subsequently entered the cist through the gap between the two orthostats (R1 & R2). As no other bone from Cist II was dated, additional dating is required to clarify this. However, others such as Cooney and colleagues (Reference Cooney, Bayliss, Healy, Whittle, Danaher, Cagney, Mallory, Smyth, Kador and O’Sullivan2011, 640) regard both the dated unburnt skulls and the cremation as part of the monument’s primary phase; they used Bayesian modelling to estimate that their deposition occurred between 2895–2835 calbc . Regardless of which view is correct, the significant point here is that these deposits reflect the ongoing use of the monument 2900–2600 calbc in a manner typical of passage tomb practices.

Similar practices spanning sometime between 2900 and 2600 calbc can also be observed within the passages of three developed tombs at Knowth. At Tomb 1C West, a similar cremation deposit (E70:50159) occurred in the outermost extension of that tomb’s passage (Fig. 2). Multiple longbone fragments occurred at an upper level in a deposit filling a gap behind one of the orthostats, two of which produced radiocarbon dates of 2920–2760 calbc (OxA-21992, 4261±31bp) and 2880–2630 calbc (UBA-12681, 4160±23bp) (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a). At Tomb 15, a cist-like stone compartment, incorporating a sillstone and two orthostats within the passage, contained the cremated remains of an adult female and a child (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 308–12). These burnt bones occurred in an upper level within a deposit sealing the floor of the passage, which had supposedly formed from material falling through gaps between the roof stones and the orthostats (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 309). Although traditionally regarded as a Beaker burial because of its apparent association with a fragmented Beaker pot (see Carlin Reference Carlin2012), a longbone fragment from the adult yielded a radiocarbon date of 2920–2870 calbc (UBA-12683, 4265±24 bp; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Eogan, Cleary, Cooney and Sheridan2017a). At Tomb 17, a further deposit of cremated human remains, including a skull bone, was found high up in the material filling the passage and the chamber just inside the orthostatic entrance (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 136). The skull bone produced a radiocarbon date of 2875–2635 calbc (UBA-12688, 4152±23 bp; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, McClatchie, Sheridan, McLaughlin, Barratt and Whitehouse2017b).

Other radiocarbon dated human remains from Carrowkeel and Carrowmore provide potentially similar evidence for the extended continuation of passage tomb activity.Footnote 4 However, these radiocarbon dates represent estimated age ranges spanning from 3100–2890 calbc which, because of the uncertainties associated with radiocarbon calibrations, may reflect a shorter time frame of depositional activity that may pre-date the adoption of Grooved Ware in Ireland c. 3000/2900 calbc. For example, Bergh and Hensey’s (Reference Bergh and Hensey2013a) radiocarbon dating of pins from the Carrowmore passage tomb complex revealed that most of these were probably deposited between c. 3650–3100 calbc . However, one of the pins from Carrowmore 3 returned a date of 3090–2900 calbc (Ua-36371, 4365±35 bp; Bergh & Hensey Reference Bergh and Hensey2013a) hinting at the possibility that the deposition of objects forming part of the classic passage tomb assemblage continued within this monument beyond 3000 calbc. This is supported by the fact that five of the 11 charcoal-based dates obtained from this tomb, as part of the Swedish Archaeological Excavations at Carrowmore Project, indicate that depositional activity continued beyond 2900 calbc in this tomb, though it is difficult to directly relate these to specific phases of the monument with confidence (Bergh & Hensey Reference Bergh and Hensey2013b, 33).

Similarly, at the Carrowkeel cairn G cruciform passage tomb, Co. Sligo (Macalister et al. Reference Macalister, Armstrong and Praeger1912) a deposit of over 200 cremated bone fragments was found on the floor of the rear recess (Lucas Reference Lucas1963, 124). Two human skull fragments from an adult and a child were selected for radiocarbon dating (Hensey et al. Reference Hensey, Meehan, Dowd and Moore2013, 16). The adult returned a typical passage tomb date of 3350–3090 calbc (UBA-15656, 4494±29 bp), and the child yielded a slightly later date of 3030–2890 calbc (UBA-15657, 4342±28bp) (Hensey et al. Reference Hensey, Meehan, Dowd and Moore2013, 18). Elsewhere, a radiocarbon date of 3015–2885 calbc (UBA-14756, 4310±25 bp; Whitehouse et al. 2014) was obtained from cremated human bone found within the chamber of a cruciform passage tomb (Chamber II) at Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow (Walshe Reference Walshe1941; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, McClatchie, Sheridan, McLaughlin, Barratt and Whitehouse2017b).

It starts from the inside

While there is a little uncertainty regarding whether some of the most recent radiocarbon-dated Neolithic deposits of human remains within passage tombs reflect activity before or after the advent of Grooved Ware, perhaps the key thing to take away from this is that the chronologies of these deposits are hard to separate out for reasons that go beyond the limitations of radiocarbon dating. This is because the nature of the later passage tomb deposits dating from sometime between 3000–2600 calbc differs little from those of earlier date. This evidence for the ongoing deposition of both burnt and unburnt human bone belonging to adults and children, particularly skulls and longbones in the passages, chambers, and in the gaps between orthostats, indicates the direct continuation of the passage tomb tradition of mortuary practice (see Cooney Reference Cooney2014; Reference Cooney2017).

Consequentially, the presence of some of these deposits in apparent stratigraphically late contexts need not be interpreted as a secondary phase of deposition. After all, Grooved Ware and other Orcadian material culture had already been incorporated into the Irish passage tomb tradition during its peak with little change in practice. Instead, the later deposits should be seen as representing the tail end of the main phase of depositional activity within their respective tombs c. 2900–2600 calbc, which was occurring at an increasingly limited scale. The active use of these monuments clearly continued into what is erroneously regarded in Ireland as a secondary phase, generally known as the Late Neolithic.

This strongly parallels the evidence that Maeshowe-type passage tombs apparently remained in active use until c. 2700 calbc (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Sheridan, Crozier and Murphy2010, 25–9; Griffiths Reference Griffiths2016, 292–5).Footnote 5 Dating of the Maeshowe-type tomb at Quanterness suggests that the main phase of burial activity continued there until c. 2850–2790 calbc , at least five centuries after this monument had become part of the surrounding landscape on Mainland, Orkney (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2016, 18–19). Similar dates on dog bones from a lower fill of the main chamber at Cuween Hill indicate depositional activity there sometime between 2840 and 2450 calbc. From the perspective outlined within this paper, the continued use of developed passage tombs into the 3rd millennium during the currency of the Grooved Ware complex is wholly unsurprising given the strong links between Grooved Ware-type or Orcadian material culture and these monuments.

AROUND THE OUTSIDE: GROOVED WARE-ASSOCIATED DEPOSITION AT PASSAGE TOMB EXTERIORS

In conjunction with the apparent decrease in deposits within passage tombs (c. 3000–2700 calbc), external activity increased after 3000 calbc, and Grooved Ware has been found in varying quantities outside of the tombs at Knowth, Newgrange, Mound of the Hostages, and Ballynahatty. Like the internal deposits associated with this ceramic, much of this external activity seems to post-date the floruit of these monuments by at least 250 years, but it can still be seen to reflect the continuation and development of passage tomb practices.

At Newgrange, removal of the so-called ‘cairn slippage’ from the front of the main passage tomb (which possibly represent Iron Age additions to the mound) revealed an underlying series of spreads of occupational debris, which were labelled as the ‘Beaker layers’ or ‘the earth/stone layer’ (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Cleary and Lehane1983, 27–9, fig. 9). Mixed within these layers were Middle Neolithic Impressed Ware, Beakers, and other materials dating to as late as the Iron Age (Cleary Reference Cleary1983, 58–117; Carlin Reference Carlin2012; Bendrey et al. Reference Bendrey, Thorpe, Outram and van Wijngaarden-Bakker2013; Ó Néill Reference Ó Néill2013), as well as transverse arrowheads and almost 2000 sherds from an estimated 67 Grooved Ware vessels, which were primarily concentrated within five areas in front of the tomb’s entrance (Cleary Reference Cleary1983, 84–100, 115; Roche Reference Roche1995).

Spatially with the Grooved Ware-associated concentrations were several rectangular stone-lined hearths and posthole arrangements. Based on the presence of a similar rectangular hearth at the centre of the Grooved Ware-associated timber structure at Slieve Breagh in Co. Meath (de Paor & Ó h-Eochaidhe Reference de Paor and Ó h-Eochaidhe1956), which was comparable to the distinctive hearths found within Orcadian dwellings (Richards Reference Richards2005; Smyth Reference Smyth2010, 25–7), it has been suggested that the Newgrange examples may also represent evidence for Grooved Ware-associated activities around the frontal perimeter of the main tomb (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Cleary and Lehane1983; Cooney & Grogan Reference Cooney and Grogan1999, 80).

The chronologically mixed deposits of occupational debris overlay (and extended outwards beyond) an extensive layer of quartz and granite stones which flank the south-eastern perimeter for 50 m either side of the tomb’s entrance (Fig. 10). This stone layer had originally been interpreted incorrectly as slippage from the mound’s façade which occurred long after the monument had been built (O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982). It has subsequently been convincingly argued that while quartz was used as a revetment at some developed Irish passage tombs, this quartz-granite layer actually represents the remains of a platform deliberately constructed during the use-life of the tomb (see below; Cooney Reference Cooney2006; Eriksen Reference Eriksen2006; Reference Eriksen2008; Stout & Stout Reference Stout and Stout2008). If true, this indicates that the Grooved Ware here could have been deposited earlier than previously presumed (eg, Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 137). This point will be returned to shortly, because its appraisal requires us to firstly consider the evidence for the relative dating of the quartz-granite layer and some other related features.

Fig. 10 Plan of Newgrange passage tomb and adjacent features showing the location of the quartz and granite platform and the Site Z passage tomb encircled by the large timber circle (after Lynch Reference Lynch2014, fig. 2)

Most of these related features are associated with a small undifferentiated passage tomb, Site Z, to the east of the main mound (Fig. 10), which is thought to have been built after the larger tomb’s construction (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986, 27). Grooved Ware was revealed outside the entrance to the Site Z passage tomb, where over 30 sherds from 12 vessels were found in a disturbed context (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Lynch and O’Kelly1978, 311–13; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 129). This tomb was enclosed by a large timber circle consisting of a series of concentric rows of post-pits and post-holes which have been partially excavated (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Cleary and Lehane1983, 16–21; Sweetman Reference Sweetman1985). Radiocarbon dates ranging from 2865–2450 calbc (Grogan Reference Grogan1991, 131; Carlin Reference Carlin2012) were obtained from charcoal within the postholes. Based on ongoing analysis and Bayesian modelling of the radiocarbon dates from at least 20 of 30 Irish timber circles by the author and Jessica Smyth, it is likely that this monument, like most other Irish timber circles, was constructed c. 2700–2450 calbc. Complementing geophysical surveys have revealed the full extent of this enclosure including an elaborate posthole-defined entrance leading inwards to the tomb’s entrance (Smyth Reference Smyth2009, fig. 1.35). Grooved Ware was also found within at least three of the post-pits forming the timber circle. Within the interior of the circle, further Grooved Ware sherds were recovered from stakeholes and spreads of habitation debris – one of which belongs to a vessel from outside the tomb’s entrance (Elaine Lynch pers. comm.) – along with transverse arrowheads (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Cleary and Lehane1983, 18, 21; Sweetman Reference Sweetman1985; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 129).

This large timber circle is pertinent to understandings of the date of the deposition of the Grooved Ware outside the main passage tomb, because the enclosure spatially respected the quartz-granite layer (Fig. 10). This suggests that either the construction of this stone ‘platform’ pre-dated (Cooney Reference Cooney2006, 704) or was coeval with the timber circle (Lynch Reference Lynch2014). This is supported by the occurrence of the spreads of occupational debris containing Grooved Ware (overlying the quartz-granite layer and extending beyond it) over some of the postholes forming the large timber circle. Also, one of the aforementioned stone-lined hearths apparently associated with these deposits was dug into one of the timber circle’s post-pits (O’Kelly 1983, 18; see Fig. 13). These imply that the Grooved Ware deposition at the entrance to the main tomb occurred after the erection of the large timber circle, but before the cessation of this ceramic’s use in Ireland sometime between 2700 and 2450 calbc (Carlin Reference Carlin2012).

This date range is apparently countered by Ann Lynch’s (Reference Lynch2014, 66) argument that the quartz-granite layer post-dates 2450 calbc, based on her investigation of a small area along the main mound’s north-eastern periphery. During her excavations outside Kerb 79, a controlled bipolar flint core and a cow’s tooth dating between the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods – 2570–2290 calbc (UB-25186, 3933±37 bp) – were found underneath a quartz deposit, presumed to be the eastward continuation of the quartz-granite layer (Lynch Reference Lynch2014, 39–40). Lynch places both the bipolar flint core and the radiocarbon date firmly within the Chalcolithic. However, it should be pointed out that instead of confirming each other, these two pieces of evidence appear to be in direct contradiction. Within the same published report, the lithic specialist who examined the material from the excavation, Farina Sternke (Reference Sternke2014, 41), considers this flint core to ‘probably date from the late Neolithic period’. This is because of the prevalence of controlled bipolar-on-an-anvil reduction in assemblages of that date compared to split bipolar cores, which are typically Chalcolithic. In contrast to Lynch, Sternke (Reference Sternke2014, 45) considers all the lithics associated with bipolar technologies from this excavation to be ‘almost certainly contemporary with the initial construction phase of the tomb’ long before the Chalcolithic.

This discrepancy raises serious questions about the chronological integrity of this radiocarbon date and whether its range of 2570–2290 calbc is truly reflective of when the quartz-granite layer was placed around the tomb. Further questions about the interpretation of this radiocarbon date are raised by the presence of Grooved Ware stratigraphically above the quartz-granite at the tomb entrance (see above; Cleary Reference Cleary1983, 84–100, 115; Roche Reference Roche1995). This suggests that this layer was deposited during the Late Neolithic, sometime before 2450 bc. However, this date is complicated by a number of uncertainties, including the chronological security of the Grooved Ware deposits overlying the quartz-granite layer, the chronologically diagnostic qualities of pebble cores, and the strong likelihood that the quartz-granite layer is not of unitary origin. After all, the layer of quartz which overlay this dated tooth was 2.70 m wide, did not contain any granite, and was at the extreme north-eastern limit of the quartz-granite layer which had a much greater average width of 4–5 m (Lynch Reference Lynch2014, 39). Thus, given the multiphase sequence of interventions with the tomb’s exterior (see above and Hensey Reference Hensey2015, 133–6), the deposits excavated by Lynch could potentially reflect a discrete later phase of activity.

Despite all this uncertainty and the clear need for a systematic dating programme to clarify the chronological sequence at Newgrange, there is little reason to doubt that Grooved Ware-associated activity was occurring outside the entrances to the main tomb and Site Z between 2700–2450 bc. Most likely, this pottery was deliberately deposited in the context of ongoing communal gatherings and ceremonial undertakings at the site.

At Knowth, a Grooved Ware-associated timber circle was discovered just 12 m outside the main mound, in front of the entrance to the eastern passage tomb (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997) (Fig. 2). Its postholes produced 500 sherds representing c. 44 Grooved Ware pots along with lithics and baked clay objects, as well as burnt and unburnt animal bone. Radiocarbon dates indicated that these were deposited sometime between 2700 and 2450 calbc (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997; Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Schulting, McClatchie, Barratt, McLaughlin, Bogaard, Colledge, Marchant, Gaffrey and Bunting2014).

Grooved Ware also occurred within two surface deposits of culturally-rich occupational debris in front of two of the smaller passage tombs, Numbers 15 and 20, at Knowth. Labelled as Concentrations A and C (Fig. 2), these probably represent the eroded remains of middens (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 270; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 129; Carlin Reference Carlin2012). At least 160 sherds from 14 fragmented Grooved Ware vessels and a transverse arrowhead were all found in Concentration A, along with Beaker pottery in a deposit surrounding the entrance and much of the southern and western perimeter of Tomb 15 (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 245–60; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997, 202–3). Concentration C was situated directly opposite the entrance to Tomb 20 and contained the fragmentary remains of 18 sherds from six Grooved Ware vessels, as well as a much larger quantity of Beaker pottery (Eogan Reference Eogan1984, 270–86; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997, 206). While these deposits were formed after the construction of the Knowth megaliths (Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 137), their chronological relationship to the use of the tombs is unclear. Unfortunately, the only associated radiocarbon determination comes from charcoal dating to the 2nd millennium bc that was found in the same location as some Middle Bronze Age pottery in Concentration A.

The occurrence of the Grooved Ware with Beaker pottery in both spreads resulted in the idea that their creation must date closely to the inception of the Beaker complex in Ireland.Footnote 6 However, there are two different types of Grooved Ware within these deposits (Roche Reference Roche1995): vessels with limited decoration which seem to have been current from 3000 to 2450 calbc, and those with stylistically early decoration generally considered to date to c. 3000/2900 calbc, such as that in Tomb 6. Thus, it may be more appropriate to place the initial formation of these deposits within an earlier rather than later part of the period 3000–2500 bc.

At the Mound of the Hostages passage tomb, two conjoining rim sherds from a Grooved Ware pot and a few fragments from two Early Neolithic Carinated Bowls came from a pit located at the eastern edge of the earthen mound covering the tomb, in front of the entrance to its passage (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 30, 40, 42, figs. 15, 19 & 23) (Fig. 11). The pit was overlain by a stone setting associated with an undated burial comprising a few small fragments of cremated limb and skull fragments. This cremation was one of 17 heavily fragmented cremation burials located around the perimeter of the mound, 11 of which also had associated stone settings (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 29–38). Bayesian modelling of the radiocarbon dates from 11 of the perimeter burials indicates that they were deposited during a relatively short period from 3300–3000 calbc , probably at broadly the same time as the earliest deposits in the tomb (Bayliss & O’Sullivan Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013).

Fig. 11 Plan of the Mound of the Hostages passage tomb showing the perimeter burials (1–17), including No. 1 which was located in front of the entrance as well as the two palisades to the north (No. 2) and to the east (No. 3) of the tomb dating from 2620–2280 cal bc (after O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, fig. 15)

Although the undated burial overlying the Grooved Ware-associated pit has been considered to be contemporary with the dated perimeter burials (eg, Cooney & Rice Reference Cooney and Rice2013, 149–50), Bayliss and O’Sullivan (Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013, 54) and Smyth (Reference Smyth2013a, 412) have all argued that this burial must be of a different date, because it was the only interment located at the tomb’s entrance, and its stone setting was more elaborate than any of the others, most of which were exclusively located south of the tomb (Fig. 11). Smyth further argued that these sherds could not be early in date because they are more comparable to insular than Orcadian styles of Grooved Ware. This and the apparent absence of evidence for Grooved Ware in Ireland pre-dating 3000 calbc led her to assume that the pit and the burial reflected a secondary phase of commemorative activity occurring later, in the early 3rd millennium. However, Bayliss and O’Sullivan (Reference Bayliss and O’Sullivan2013, 54) suggested that the burial dates to the first half of the 3rd millennium and that the presence of the Grooved Ware sealed beneath it may indicate the early adoption of this ceramic in Ireland during the monument’s primary use.Footnote 7 This possibility may seem more credible considering the evidence for the continuity of practices within this and other passage tombs between 2900 and 2600 calbc.

A similar relationship between external Grooved Ware deposits and passage tombs can be observed at the Ballynahatty monument complex. A small simple passage tomb which potentially dates to the first half of the 4th millennium (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986; Reference Sheridan2003) seems to have provided a locus for at least two subterranean passage tomb-related monuments and pit burials dating from c. 3300–3000 calbc, as well as an oval-shaped timber enclosure apparently built and destroyed during the first half of the 3rd millennium (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998; Reference Hartwell2002; Hartwell & Gormley Reference Hartwell and Gormley2004) (Figs 12 & 13). The simple passage tomb was also deliberately encircled by an embanked enclosure (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1991) which is generally seen as an Irish example of a henge monument and assumed to have been constructed during the currency of Grooved Ware on this island (eg, Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 172; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004a, 29).

Fig. 12 Plan of the Ballynahatty passage tomb complex comprising a simple passage tomb which is encircled by an embanked enclosure; the ‘1855’ sunken segmented passage tomb; a miniature passage tomb; a line of four passage tomb related pit burials; and a large oval-shaped timber enclosure (BNH 5 & 6) (after Plunkett et al. Reference Plunkett, Carroll, Hartwell, Whitehouse and Reimer2008, fig. 1)

Fig. 13 The passage tomb related monuments at Ballynahatty: (1) sunken circular segmented megalith chamber; (2) simple passage tomb; (3) sub-megalithic rectangular chamber tomb with western passage and a lintelled orthostatic entrance; (4) one of the slab-lined pits containing a Carrowkeel Bowl filled with cremated human remains (after Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998, fig. 3.2)

Antiquarian investigations in the 19th century uncovered one of the subterranean passage tombs 500 m to the north-east of the simple passage tomb. This comprised a sunken circular megalith chamber with a corbelled roof that was radially segmented into peripheral compartments containing burnt and unburnt human remains dating from c. 3380–3050 calbc, as well as three to four Carrowkeel bowls filled with cremated bone (MacAdam Reference MacAdam1855; Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998; Reference Hartwell2002; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Murphy, Jones and Warren2012, 37) (Fig. 13). This is remarkably similar in size, shape, and design to another subterranean chamber tomb from Crantit, Orkney that was also radially divided into peripheral compartments and was probably built and used at the turn of the 4th millennium (Ballin Smith Reference Ballin Smith2014). The striking correspondence between these provides further evidence of connections between Orkney and Ireland at this time.

The second subterranean chamber tomb, 250 m to the north of the simple passage tomb, was excavated by Barrie Hartwell. This comprised a sunken sub-megalithic rectangular chamber with a clearly defined western passage and a lintelled entrance defined by two orthostats which seemed to form a miniaturised passage tomb (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998, 35–6) (Figs 13 & 14). Inside were two Carrowkeel bowls containing cremations, bone from which produced a radiocarbon date of 3346–2954 calbc (GrA-14812, 4460±40 bp) (Hartwell & Gormley Reference Hartwell and Gormley2004).

Fig. 14 Detailed plan of the large timber enclosure with elaborate entrance annex and façade (BNH 5) at Ballynahatty enclosing the smaller timber circle (BNH 6). Note the location of the sunken miniature passage tomb and the Grooved Ware associated stony deposits in front of this tomb (after Plunkett et al. Reference Plunkett, Carroll, Hartwell, Whitehouse and Reimer2008, fig. 2)

Near this miniaturised passage tomb was a line of four small, equally spaced cremation pits containing bone from at least two adults and a juvenile (Figs 13 & 14). Although partially destroyed, two of these pits were slab-lined, one of which contained a Carrowkeel Bowl filled with cremated human remains. Another of these bowls also occurred in one of the unlined pits, suggesting a date of 3300–2900 bc for these features. Parallels can certainly be drawn between these cist-like pits and other similarly slab-lined features at Millin Bay and Mound of the Hostages which both contained the cremated remains of individuals dating from the latter centuries of the 4th millennium (Collins & Waterman Reference Collins and Waterman1955; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2005, 29–38; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Murphy, Jones and Warren2012). All of these, including those from Ballynahatty, have been interpreted as small scale versions of the passage tombs with which they were spatially associated (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998, 36; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2007, 167; Cooney Reference Cooney2009; Jones Reference Jones2012, 54; Cooney & Rice Reference Cooney and Rice2013, 149–50).

The excavation of cropmarks 200 m to the north of the Ballynahatty simple passage tomb revealed the large timber enclosure, as well as a smaller timber circle and other timber settings within its interior (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998; Reference Hartwell2002) (Fig. 14). The enclosure had an elaborate entrance which comprised an outer post-built annex with a façade of large posts (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998). Grooved Ware was recovered from the post-holes forming the timber circle and the entrance annex, as well as from a series of stony surface deposits associated with the latter. By far the greatest concentration of this pottery came from these stony deposits that occurred right in front of the entrance to the miniature passage tomb, just like the Grooved Ware-associated surface deposits at Knowth and Newgrange (though the entrance to the Ballynahatty tomb was subterranean!).

The destruction of the Ballynahatty timber structures is dated to sometime between 3039 and 2339 calbc, based on eight radiocarbon determinations which were obtained from bulk charcoal samples. Some of these may have included mature oak with a potential own age of 500 years, and this is probably true of the two earliest dates which pre-dated 2900 calbc (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1991; Reference Hartwell1998). Most of the other dates cluster between 2883 and 2500 calbc (Hartwell & Gormley Reference Hartwell and Gormley2004) and appear to fit broadly within the dating of other Irish timber circles.

Despite this chronological imprecision, it is clear that the Grooved Ware-associated activity at this complex was directly related to the pre-existing monuments of the passage tomb-tradition. Significantly, the timber entrance façade was constructed just behind, but almost parallel to, the line of four equally spaced cremation pits and beside the underground cist with passage tomb affinities. Although the posts were erected either side of this cist, possibly in an effort to respect it or incorporate it within the outer annex, one of the postholes was dug into its edge (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998, 44). The strong physical connection between the timber enclosure and the features with passage tomb affinities is accentuated by a line of posts leading from the entrance façade of the timber enclosure towards the entrance of the simple passage tomb, which may even have joined these monuments together (Hartwell Reference Hartwell2002, 530) (Fig. 14). Although the dating of the associated embanked enclosure is also unclear, it is tempting to view it as very much part of this sequence.

Exteriority as an original feature of developed passage tombs

The Grooved Ware activity outside Knowth, Newgrange, Mound of the Hostages, and Ballynahatty has occasionally been regarded as evidence for both continuity of place and practice (Bradley 2007, 106, 112; Carlin & Brück Reference Carlin and Brück2012). However, this has predominantly been seen as a secondary development reflecting the replacement of the passage tomb complex as part of a major ideological shift in focus away from the closed, private, internal world of the chamber to more inclusive, larger-scale, public performances of ceremonies within open-air monuments such as henges or stone circles (eg, Bradley Reference Bradley1998, 104–9; Simpson Reference Simpson1988, 35; Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1999, 108–9; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 167–73; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 139; Stout Reference Stout2010; Smyth Reference Smyth2013a, 412; Reference Smyth2013b, 319). In opposition to this, it is argued here that these Grooved Ware-associated acts were not just commemoratively echoing long-distance actions or reinventing neglected older traditions in a bid to maintain links to an ancestral past. Instead, these are best considered as the continuation of the existing passage tomb practices.

Emphasising the exteriors of these monuments, particularly the area around the entrances (to heighten distinctions between the outside and inside), is a primary characteristic of developed passage tombs in Ireland, including the smaller examples at Knowth and Newgrange (Bergh Reference Bergh1995, 156; Bradley Reference Bradley1998, 114; 2007, 106; Cooney Reference Cooney2006, 705; Stout Reference Stout2010; Hensey Reference Hensey2015). Examples of this include the decoration of external kerbstones, the flattening of the fronts of tombs, and the inturning of the entrances, as well as the construction of encircling platforms, banks or ditches, and standing stones (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1986, 23–5; Bergh Reference Bergh1995; Bradley Reference Bradley1998, 110; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 119; 2006, 704–5; Roche & Eogan Reference Roche and Eogan2001, 139). Other instances include: the creation of sub-circular settings of stones outside the entrances to the large tombs at Newgrange, Knowth, and Loughcrew Cairn T and Miosgan Maedbha, Co. Sligo (Rotherham Reference Rotherham1895, 311; O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 75–7; Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 46–8, 65; Bergh Reference Bergh1995, 90–1); the deposition of exotic objects and/or non-local stone such as quartz outside Loughcrew cairns L and T, Newgrange, Knowth, Dowth, and Knockroe (Conwell Reference Conwell1873, 29; O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 68; Eogan Reference Eogan1986, 46–65; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2009, 22; Hensey Reference Hensey2015); or the encircling of the perimeter of the Mound of the Hostages with a ring of pit burials. Much of this is consistent with Robin’s (Reference Robin2010) reflection that concentricity was a core feature of many Irish passage tombs, including those of early date like at Carrowmore, because they comprise a system of concentric spaces whereby a series of rings encircled the central chamber.

Robin’s observation is particularly well demonstrated by the multi-phase construction of the Newgrange passage tomb. While the excavation of a limited area at the rear and side of the mound did not produce evidence to corroborate Eriksen’s arguments that the redeposited turves within the mound indicate different phases of construction (Lynch Reference Lynch2014), there remains a very strong body of convincing evidence to support the arguments for an extended sequence of building at the front of the tomb (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2006; Reference Eriksen2008; Andersen Reference Andersen2013, 521–3; Hensey Reference Hensey2015, 133–6). This included the erection of the orthostatic kerb as a free-standing external enclosure at least 9 m outside an earlier, smaller mound before the expansion of this mound and the extension of the passage outwards to meet the kerbed perimeter (O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1982, 87–91). Concealed beneath the expanded version of the mound were two rings of boulders which coincide with the probable previous locations of the passage entrance and seem to be precursors to the orthostatic kerb with which they are concentric (Robin Reference Robin2010, 374–5).

Both the boulder rings and the orthostatic kerb at Newgrange can be seen as early manifestations (presumably dating from 3300–3000 bc) of an enduring series of concentric spatial divisions around the periphery of this tomb. This tradition was continued episodically with the subsequent addition of the quartz-granite layer, the Grooved Ware and Beaker deposits, as well as a yellow clay bank throughout the 3rd millennium (Cooney Reference Cooney2006, 706; Carlin Reference Carlin2012). It may even have continued beyond this with construction of the stone circle, which occurred sometime after 2200 bc, but before the Iron Age augmentation of the mound.Footnote 8 As Cooney (Reference Cooney2006, 706) observed, to argue whether the quartz-granite layer flanking the entrance to Newgrange is a passage tomb or a post-passage tomb feature is to miss the point that its formation is critical to a continuing sequence of enclosing actions emphasising this location (Fig. 10).