INTRODUCTION

Due to their vulnerability, children are entitled to receive special treatment, both internationally and nationally. Though Bangladesh has ratified many international instruments and adopted several national policies, child rape is still a major issue. Bangladeshi children are trapped in a male-dominated society where they are continuously prey to sexual exploitation by men. Children in Bangladesh are not safe or protected on the streets, in schools, on playgrounds, in neighborhoods, and even in their own homes (Amin Reference Amin2020). From the filing of the first information report (FIR) to the framing of charges and the conclusion of a trial, victims of rape face tremendous challenges and complications (Bangladesh Mahila Parishad 2020). There are a variety of reasons for these circumstances, including police failing to collect circumstantial evidence or catch offenders. Next, due to the lack of witness protection and proper rape laws, inadequate prosecution dealings, and the conservative approach of judges, rape cases continue to remain pending before courts each year (Bangladesh Mahila Parishad 2020). Victims are frustrated and disinterested in filing complaints, and actual and potential rapists are encouraged by victims’ unwillingness to file a rape complaint.

However, Bangladesh has taken steps and enacted special laws to address rape. It has ensured severe punishment in the form of life imprisonment for those who commit rape. The imposition of penalties is not the only remedy to stop such crimes. New law provisions are also required to fight child rape. There is a dire need to work toward changing attitudes about rape culture and toward ensuring the reformation of offenders.

OBJECTIVE AND METHODS

This article aims to examine the present circumstances of child rape in Bangladesh. It focuses on the drawbacks of the laws addressing rape, complicated criminal justice procedures, and the downside of social customs. The article relies on a qualitative approach and draws upon Bangladeshi case law relating to rape. Moreover, it focuses on the reports of incidents irrespective of whether a formal complaint was filed or not. The article uses secondary sources, including case law, legislation, books, journals, newspaper articles, and reports. The article also relies on statistical data from several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and organizations working with women and child rights. As these organizations have collected data from daily national newspapers, the author does not claim that these data are accurate. This article emphasizes only male molesters who rape children irrespective of gender.

REASONS WHY MEN COMMIT CHILD RAPE IN BANGLADESH

“The word ‘rape’ refers to forcible seizure, and the simplest explanation of rape is having sexual intercourse with a child with/without her consent” (Safazuddin and Another vs. The State, 27 Bangladesh Legal Decisions, High Court Division 2007). Rape violates the victim’s fundamental rights, namely the “right to life,” as guaranteed under Article 32 of The Constitution of The People’s Republic of Bangladesh (1972) (Safazuddin and Another vs. The State, 27 Bangladesh Legal Decisions, High Court Division 2007). In Safazuddin and Another vs. The State, some causes were identified for the rise in the number of rapes by men in Bangladesh: uncontrollable sexual desire, adolescent pressures, opportunities created by chance circumstances, momentary passion, and, in some instances, vengeful attitudes.

Pedophilia is typically defined as the recurrent sexual interest in prepubescent children, as reflected in persistent thoughts, fantasies, urges, sexual arousal, and behavior (American Psychiatric Association 2013; Seto Reference Seto2004). Mental health professionals refer to the term pedophilia as having a sexual interest in prepubescent children and pubescent teenagers (Lanning Reference Lanning1992:10). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III-R, pedophilia is a form of paraphilia or psycho-sexual disorder (American Psychiatric Association 1980). Not all pedophiles are rapists as some may only have a sexual interest in children, but some pedophiles cannot control their urges and do commit rape (Lanning Reference Lanning1992:10). Dr Park Elliot Dietz (Reference Dietz and Sanford1983) divided child sex offenders into two broad categories: situational and preferential. The former do not have an exclusive sexual preference for children. They engage in sexual activity with children for complex reasons such as wanting to try sex with a child as a “once in a lifetime” experience. They commit rape because they are bored of sex with adults. They take the opportunity when a victim is too young or weak and take advantage of the availability of the victim when a guardian is not protecting them. The latter have an exclusive sexual preference for children; their sexual desires, fantasies, urges, and erotic imagery center on children. These rapists fulfill their sexual desire by targeting innocent children. Children can be lured or convinced to have sexual intercourse by offering them rewards such as candy, toys, or by threatening them.

A women’s organization held a policy dialogue called “WE CAN” at the Ministry of Planning, a Bangladeshi governmental department, in December 2019, where it was stated that the percentage of reported incidents of violence was only 3% (Khatun Reference Khatun2019). According to the Supreme Court report, as of March 2019, over 38,000 cases filed under the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act (2000) (hereafter, Act of 2000) that deals with violence against women and children in Bangladesh have remained pending before lower courts for more than five years (Hossain Reference Hossain2020). Under this law, a total of 164,551 cases are pending (Hossain Reference Hossain2020). This brings to mind the legal maxim that “justice delayed is justice denied,” as, during this long wait period, evidence can be destroyed, and witnesses may turn hostile. In March 2017, three influential people allegedly raped two girls, and the case is still pending because the witnesses have vanished, and the accused were released on bail (Dhaka Tribune 2020). Additionally, there is no witness protection program in Bangladesh, and so, offenders often threaten witnesses who are often unwilling to testify in court and offer evidence out of fear for their lives, property, or family’s safety (Law Commission Bangladesh 2011). Justice seems inaccessible to most victims of violence, and this creates a culture of impunity for rapists, and this encourages men to commit rape.

In most cases in which family members are abusers, grievances remain ignored. It is easy to target children from one’s family or neighborhood. On November 25, 2019, a National Dialogue on Action Against Sexual Violence was held jointly by the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs and the United Nations in Bangladesh (Amin Reference Amin2019). The meeting revealed that family members were offenders in 90% of the cases of the sexual abuse of children (Amin Reference Amin2019). When the offender is a family member, most incidents are handled behind closed doors for the sake of the family’s reputation.

A lack of traditional morality is the reason why some fathers rape their daughters. For example, a court sentenced one man to life imprisonment for raping and impregnating his 12-year-old daughter (Akand Reference Akand2019).

Criminals commit rape without the fear of being detected because the children they abuse cannot identify them (Daily Star 2019c), which explains why sex offenders predominantly target children. Disabled children are also targets for offenders as they may not be able to describe their sufferings accurately (Wasim Mia and Another vs. The State, 23 Bangladesh Legal Decisions 2003). Disabled children find it difficult to express grief, and if the child is mentally challenged, then he or she may not even understand the nature of the crime.

Many child domestic workers also face sexual violence as offenders have the opportunity to rape them when they are alone (Motiur Rahman Mithu vs. The State, 15 Bangladesh Legal Decisions 2015). According to the Domestic Workers Federation and Welfare Policy (International Domestic Workers Federation 2015), the minimum age for light domestic work is 14 years. An employer can appoint a 12-year-old as a domestic worker by negotiating the terms with a legal guardian in the presence of a third-party witness. Bangladesh is an economically backward country with constrained resources. Therefore, child domestic workers suffer for extended periods of time because they do not want to lose their jobs.

Women and Children Repression Prevention Tribunals (established under the Act of 2000), from five districts, reported that only 3% of cases relating to violence against women and children result in conviction (Amin Reference Amin2019). The rapist takes advantage of Bangladesh’s intricate criminal justice system. Because the rape victim must prove their case “beyond any reasonable doubt,” if any elements of crime remain unproven, the offender is discharged.

Social instability, political unrest, erroneous religious teachings, economic uncertainty, the custom of practicing violence, geographical conditions, and feelings of inferiority are significant causes of sexual crimes (Paranjape Reference Paranjape2014:50, 193, 194), and revenge and anger are reasons why people commit crimes in general (Agnew Reference Agnew1985, Reference Agnew1992). In 2011, a study conducted by the United Nations Population Fund and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh revealed that 77% of urban and 82% of rural men in Bangladesh believed that “sex is men’s entitlement” (Bari, Moyukh, and Sajen Reference Bari, Moyukh and Sajen2017). Of those surveyed, 29–30% sexually abused women out of anger to punish them (Bari etal. Reference Bari, Moyukh and Sajen2017). Sometimes, to take revenge against a family, a rapist will target a child (Daily Star 2019a). The availability and unauthorized use of drugs influence men to commit child rape, as drugs can obscure a person’s sense of morality (Daily Star 2019d). Two people were sentenced to death by the Women and Children Repression Prevention Tribunal for killing two children after raping them (Jagonews24 2020; Tipu Reference Tipu2019).

STATISTICAL PICTURE AND SOCIETAL PERCEPTION OF CHILD RAPE

Though 49 years have passed since Bangladesh gained independence, the condition of women and children remains in need of much improvement. Since time immemorial, child rape has prevailed in Bangladesh. As society has failed to break the chains of patriarchal culture, gender discrimination continues to be a component of many aspects of life. Even infants are not safe from rape. A 40-year-old man allegedly raped an eight-month-old girl (Akand Reference Akand2016). In June 2019, a nine-month-old girl was allegedly raped by her paternal uncle in her own house when her parents were absent (Daily Star 2019b).

It is not that rape is more frequent now, but that several NGOs and organizations have been working to collect information and help provide access to justice. Owing to the emergence of a considerable number of online news portals, people can now access more information. Women feel more encouraged to file complaints because of education and empowerment (Bangladesh Mahila Parishad 2020). However, children are vulnerable and cannot understand the nature of the offenses committed against them because there is no sex education in Bangladesh, and Bangladeshi society considers sex talk shameful.

The data used in this article were gathered from several NGOs and organizations working for women’s and children’s rights, such as the Bangladesh Shishu Adhikar Forum (BSAF), Bangladesh Mohila Parishad (BMP), and Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK). These organizations have collected data on child rape from several daily newspapers and sometimes have also sent field investigators to verify the reality of the offenses. However, the number of child rapes is far higher than the number that has been reported by these organizations. The author has collected data from their online websites and also talked to members of the organizations about unreported crimes. According to the data, the number of cases filed remains low. Even though journalists can collect information in big cities, the number of cases in the countryside, small towns, and villages remains underreported because of the fear of social stigma, the taboo on speaking up about rape, local power structures, cultural values, and the fear of being blamed and disowned by family and society.

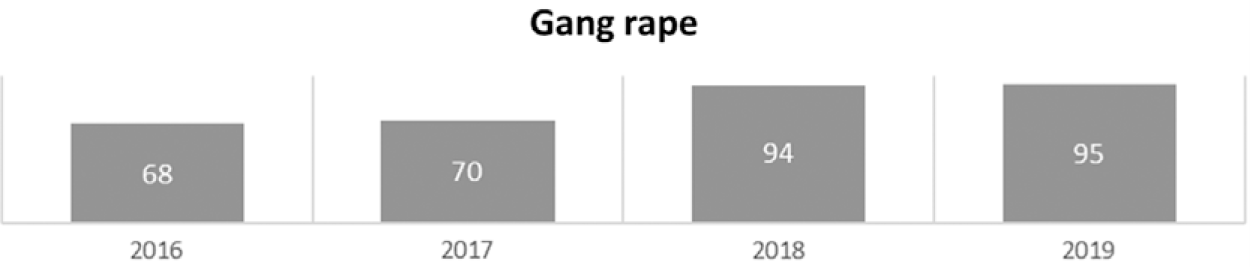

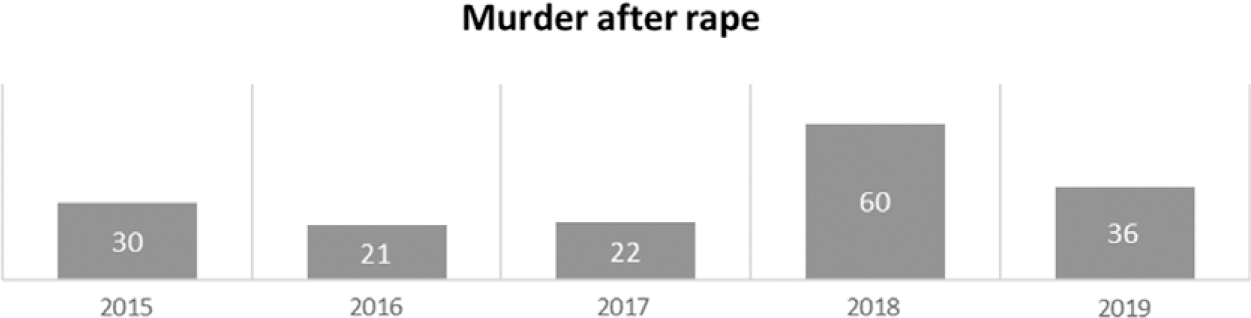

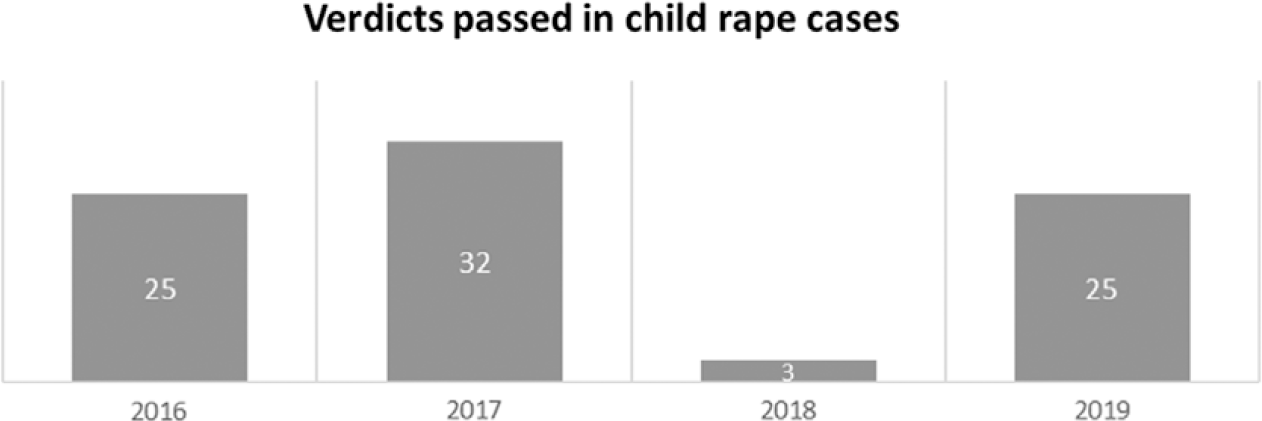

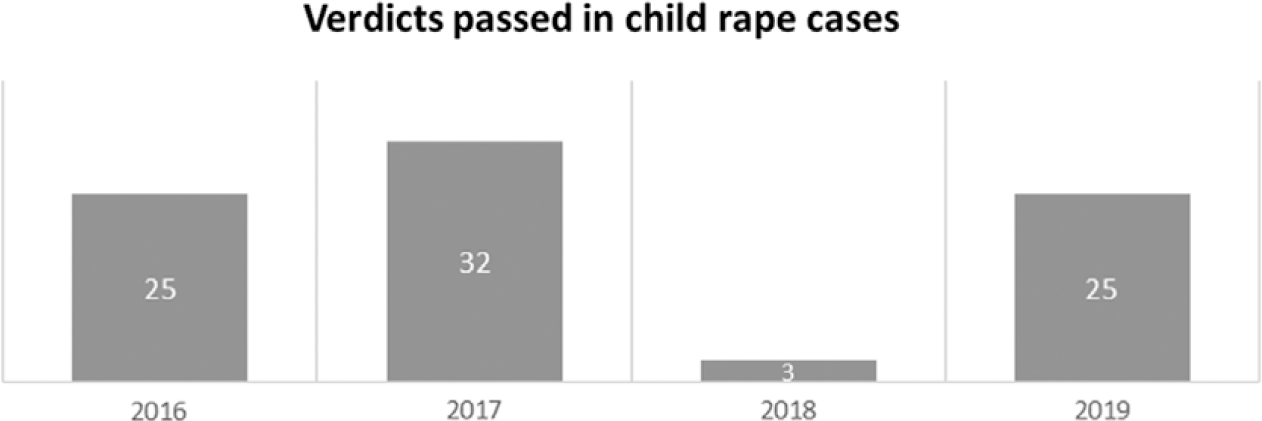

The following data were gathered from the BSAF, an NGO working for child rights in Bangladesh (see Figures 1–7).

Figure 1. Numbers of child rapes

Figure 2. Number of gang rapes

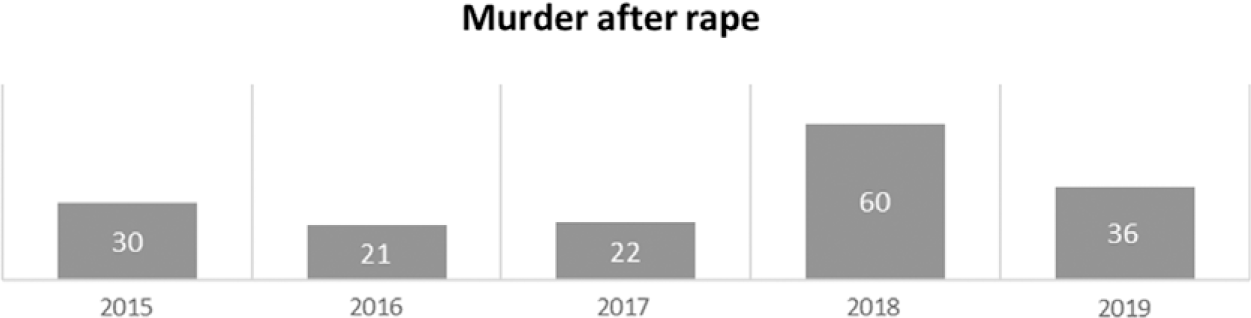

Figure 3. Number of murders after rape

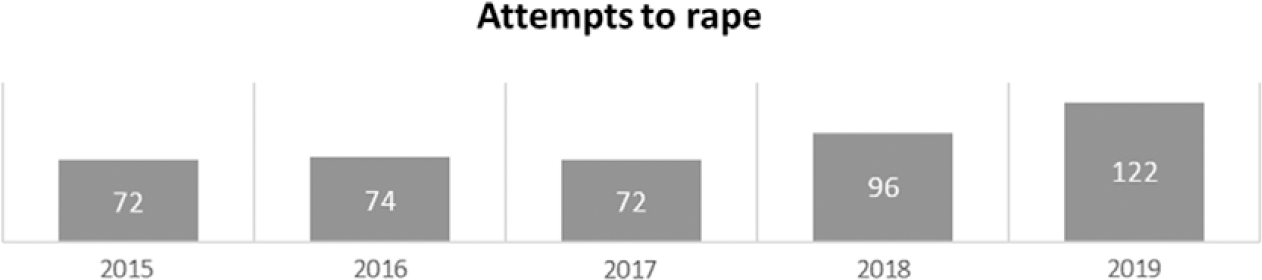

Figure 4. Number of attempted rape

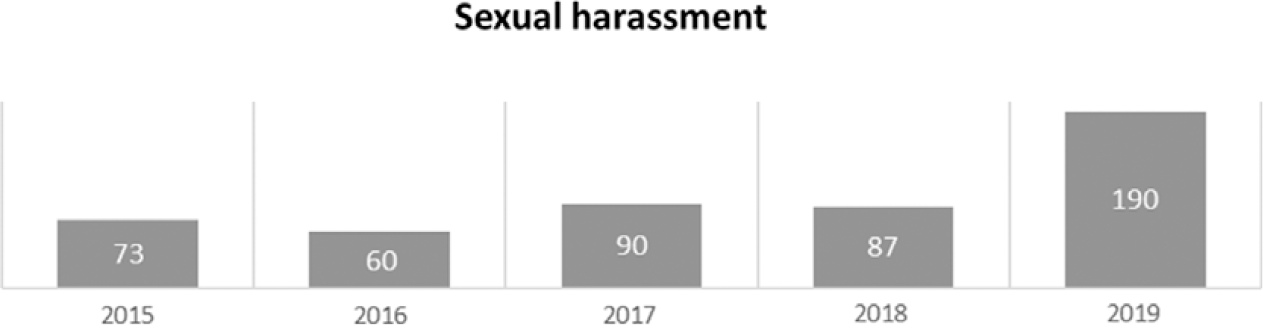

Figure 5. Number of sexual harassment cases

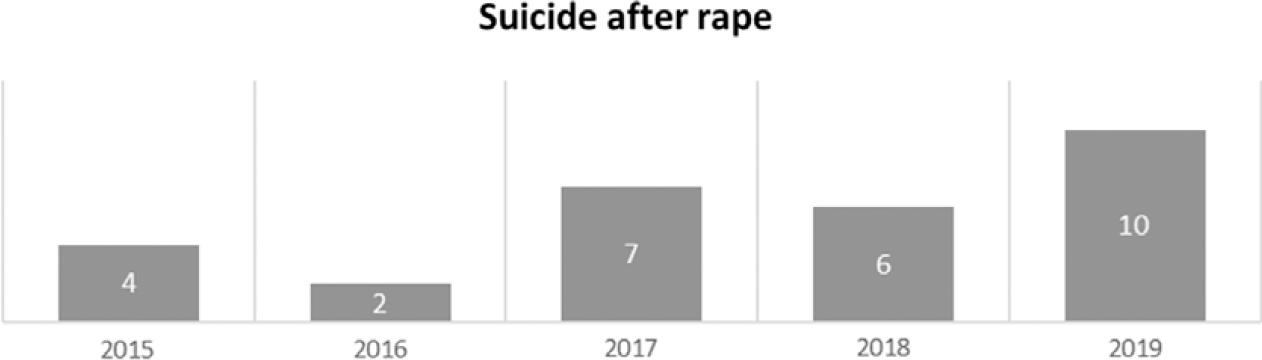

Figure 6. Number of suicides after rape

Figure 7. Number of verdicts passed in child rape cases

The BSAF published the findings in a report titled the “State of Children’s Rights in Bangladesh 2019,” where it mentioned that incidents of child rape in 2019 had doubled from 2018 (Amin Reference Amin2020). According to this report, 141 children were raped by neighbors, 120 by intimate relations, 75 by teachers, and 54 by close relatives (Amin Reference Amin2020). The BSAF report also shows that the highest number of child rape cases (116) and child murder cases (63) were reported in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Other regions from which information on child rape and murder emerged were either major cities like Chittagong or areas near Dhaka. The number of these crimes reported were nominal in villages and small towns.

According to ASK, which is a legal aid and human rights organization in Bangladesh, a total of 986 child rape incidents had occurred in 2019, among which 721 cases were filed (Ain o Salish Kendra 2020). ASK also collected its data from several national newspapers and their investigative reporters.

According to a report titled the “State of Violence against Women and Girls in Bangladesh 2019: Rape, Gang Rape, and Attempt to Rape” (Bangladesh Mohila Parishad 2020), 684 female children were raped in 2019. Most of them were around 10 years old. As many as 15% of the victims were in grades 1 to 5, whereas 20% were from grades 6 to 10 (Bangladesh Mohila Parishad 2020). According to this report, most victims were from Upazila Parishad (i.e. sub-district councils) (50%), and other villages (26%). As many as 46% of the gang-rape victims were from Upazila (sub-districts), and 22% were from villages. In the case of child rape, neighbors were the offenders in 45% of cases. Most offenders involved in gang rapes (27%) were transients. The BMP report does not mention an estimate of unreported crimes as it is challenging to extract such information from the families of victims, especially when the offenders are influential and put pressure on victims and their families. Often, family members are beaten or even killed by the offender if the victim’s family refuses to withdraw the case or is determined to file a complaint (Bangladesh Mohila Parishad 2020).

The reports published by these organizations indicate that there is inconsistency in the findings. According to the BSAF, most cases of child rape were reported in Dhaka, whereas the BMP indicated that most cases were reported in villages and small towns. ASK noted that most cases were reported and filed, while the BSAF and BMP stated that more cases were not reported or filed and were thus difficult to identify. Therefore, it is tough to claim that there is a single definite figure depicting the number of child rapes. It is difficult to identify the accurate number of such crimes.

According to Action Aid Bangladesh, until 2019, only 3% of cases relating to violence against women and children resulted in a conviction. Only 2.1% of victims informed local leaders of their experience, while 1.1% sought help from the police (Asha Reference Asha2020). As stated by the NGO Naripakkha from 2011 to 2018, there were 4,372 reported rape cases across six districts, including Dhaka (Yeasin Reference Yeasin2020). Among these, 1,283 cases were disposed of; 989 of these cases were dismissed because the police lacked sufficient evidence to frame charges (Yeasin Reference Yeasin2020). Also, 289 accused were acquitted. Only five people were punished after being convicted of rape against these 1,283 rape cases (Yeasin Reference Yeasin2020). According to ASK’s former executive director and human rights activist Sultana Kamal, many cases of sexual violence go unreported. Generally, of reported cases, only 3% saw sentencing for rape, and 0.3% for “murder after rape” (Shopon Reference Shopon2020). These upsetting figures reveal the reality that most rape victims and survivors encounter difficulties in seeking justice while rapists remain unpunished.

Some of the hurdles for victims and the reasons why offenders have impunity are discussed below:

First, the family of the victim is often reluctant to take legal action because of social stigma and reluctant to go against conventional social norms. The fear of being disowned by society restrains them from reporting a case. If the offender is a relative, then family honor and reputation come before the victim’s grief.

Second, even if the family fights the fear of stigma, some influential people may threaten them to retreat. These influential people may seek to protect the offender for political, economic, or social reasons. This usually happens when the family of the victim is indigent or lives in a rural community.

Third, the rape victim may face hurdles in filing a case owing to mismanagement in law enforcement agencies. The police often refuse to take complaints, especially when the offender is influential and holds a prominent position in society (Bangladesh Mohila Parishad 2020).

Finally, sometimes, it is difficult for the family of the victim to bear the cost of litigation because one out of every four cases under the Act of 2000 lasts for over five years (Khan Reference Khan2019). Thus, complainants, especially from rural areas, choose out-of-court settlements in the form of salish, which is a local justice system in rural Bangladesh. They find it convenient, less costly, and time-saving when compared to formal court procedures. Unfortunately, in salish, the offender is set free after paying some money or marrying the girl. For example, a schoolgirl was abducted and allegedly raped by a young man, and the village forced the girl to marry her rapist (Hasan Reference Hasan2020). Offenders may choose out-of-court settlements to escape punishment. A 50-year-old man raped a 15-year-old autistic girl and gave the village leader and a lawyer USD 1,061 to dispose of the matter in the form of salish (Daily Star 2020).

LAWS RELATING TO CHILD RAPE AND THEIR DRAWBACKS

Since independence, three different governments of Bangladesh have enacted and passed several laws against rape. They revised the punishments to make them harsher in order to deter potential rapists. Under the Penal Code of 1860 (PC 1860), which was enacted during the British Colonial period, the punishment for rape was either rigorous life imprisonment (hard labor for life) or imprisonment up to 10 years plus a fine. The first reform came in the name of the Cruelty to Women (Deterrent Punishment) Ordinance (1983). Though it retained the definition of rape under the PC 1860, it introduced the death penalty as a punishment for offenses like rape. After many years, another reform, the Women and Children Repression Prevention (Special Provision) Act (1995), repealed the Ordinance of 1983. It also retained the old definition of rape but increased the age of consent for sexual intercourse to 16 years. The 1995 Act also focused on reforming penalties, introducing the mandatory death penalty provision for murder after rape. For rape, the minimum sentence was life in prison. Finally, the prior act was repealed and replaced by the Act of 2000, which was amended in 2003, finalizing life imprisonment for rape. However, the act removed the mandatory provision for murder after rape. However, it remains true that rape law adheres to an ancient definition of and stance on rape. The definition under the PC 1860 is still in use. The legislature has only amended the punishment and procedure but not the definition or concept. A suitable law is necessary for the modern era.

Definition of Rape

Section 375 of the PC 1860 defines rape as follows: “A man is said to have committed ‘rape’ if he has sexual intercourse with a woman, first, against her will; second, without her consent; third, with her consent obtained by putting her in fear of death or harm; fourth, with her consent when she believes she is the lawfully married wife of that man and the man knows that she is not; and finally, with or without her consent when she is under 14 years of age. Penetration is necessary to prove rape.”

In the 21st century, this definition is not comprehensive at all. Besides, the section does not address child rape, though it does mention that when a man has sexual intercourse with or without consent with a girl younger than 14 years, this constitutes rape. Unfortunately, this legislation lags behind many contemporary issues around sexual abuse and exploitation. For example, this law only refers to vaginal penetration of a woman by a man, and does not include male children or transgender people within the scope of rape. Additionally, the definition of rape does not address oral or anal penetration by a penis. If any person inserts any object or any body part apart from a penis to any extent into a child’s vagina, urethra, or anus, this does not constitute rape.

Issue of Age and Consent

This article only focuses on child rape; hence, the complexity of negating consent will not be addressed as the consent of a child is immaterial as a defense in rape. Unfortunately, there is no harmony regarding the definition of “children” across different national laws in Bangladesh. Different national laws define the age range for children differently.

Under the Act of 2000, a person under 16 years old is considered a minor, both male and female. Therefore, the statutory age of consent is now 16 years. If any man engages in sexual intercourse with a woman older than 16 years without her consent, forcefully, or after deceitfully obtaining her permission, or engages in sexual intercourse with a person younger than 16 years, it is deemed as rape. Interestingly, the Child Marriage Restraint Act (2017) ratifies that a woman must be 18 years old to be legally married. A valid question arises as to why the ages for legal marriage and consent in having sexual intercourse are different in a country where sex education is taboo?

Bangladesh is a signatory member of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (1989). Article 1 mentions that “child” refers to any human being who is younger than 18 years unless the law of a particular land provides for the majority at an earlier age. Under the Majority Act of 1875, any person who has not completed his or her 18th year is a child. However, those minors for the superintendence of whose property courts have appointed guardians are considered to attain majority when they are 21 years of age.

In compliance with the UNCRC, Bangladesh enacted the Children Act (2013), in which the definition of a child is a person under 18 years old. Under the Act of 2000, every person 16 years old or older can consent to sex, and it will not constitute rape (Hanif Sheikh vs. Asia Begum 1999:129). Even if the offender induces a person older than 16 years to have sexual intercourse under the promise of marriage, the action does not amount to rape (Hanif Sheikh vs. Asia Begum 1999:129).

On the other hand, under the Prevention and Suppression of Human Trafficking Act (2012), a child is defined as a person who has not yet completed his or her 18th year. Also, any kind of consent from a child is not valid. In addition, under the Pornography Control Act (2012), a child is defined as a person who has not attained the age of 18 years. Thus, it is clear that different legislation indicates different ages in its definitions of a child; however, in the several laws in which a child is a victim of a rape, the Act of 2000 reduces the age of consent to 16 years.

Punishment for Rape

According to Section 9 of the Special Law (2000), the punishments for child rape are as follows:

For the rape of a woman or a child, the punishment is rigorous imprisonment for life and a fine.

As a consequence of rape or acts after rape, if a child dies, the offender shall be punished with death or rigorous life imprisonment with a fine not exceeding approximately USD 1,177.

If a gang rape causes the death or injury of a child, each offender shall be punished with death or rigorous life imprisonment with a fine not exceeding approximately USD 1,177.

An attempt to cause death or harm after rape shall be punished with rigorous life imprisonment and a fine.

An attempt to rape shall be punished with rigorous imprisonment between five and 10 years and a fine.

If rape takes place while in police custody, every person responsible for the safe custody of the victim shall be punished for failure to provide safety, unless otherwise proved, with imprisonment for either description from five to 10 years of rigorous imprisonment and a fine not exceeding USD 117.

There are several weaknesses in this provision. First, the notion of giving consent is not clear in the text. There are no variations in the punishments provided. The punishment is hard labor for life imprisonment for both rape and attempting to cause death or harm after rape. The punishment is either the death penalty or rigorous life imprisonment for causing death during or after rape. Hence, as the punishment for rape is, to some extent, similar to that for attempting to harm a person after rape or attempting to cause death, the offender may commit the higher crime and attempt to kill the victim to eradicate all evidence, as he knows that he will be sentenced with, at minimum, life imprisonment. Next, the degree of offense that constitutes an “attempt to rape” is uncertain. Section 10 of the Act of 2000 discusses sexual assault. If a man touches the sexual organ or any other organs of a woman or child with any organ of his body or any other substance to satisfy his sexual urge, he commits sexual assault. If a man outrages a woman’s modesty, it constitutes a sexual offense, and he shall be imprisoned for a term not exceeding 10 years but not under three years of rigorous imprisonment and fines. If any person touches a child’s sexual organ with his or her sexual organ or with an object, does it count as sexual assault or an attempt to rape?

Concept of Marital Rape

Section 375 of the PC 1860 mentions that if a man has sexual intercourse with his wife with or without her consent, as long as she is not younger than 13 years, this does not constitute rape. Cultural and legal aspects suggest that a wife can never freely refuse to have sex with her husband. The consent of the wife is immaterial if she is aged 13 years old or older. However, Section 3 of the Domestic Violence Act (2010) refers to sexual abuse that humiliates, degrades, or otherwise violates the dignity of the victim committed by any person with whom the victim has a familial relationship.

There is no punishment for this offense, as the court only provides a protection order. If the offender violates the protection order, he faces six months imprisonment or a penalty of approximately USD 117 or both. If he repeats the offense, then he faces up to two years imprisonment and a fine of around USD 117 or both. In Bangladesh, because of the conventional judicial system and inadequate laws, marital rape cases are not addressed.

On the other hand, the “special circumstances” provision in the Child Marriage Restraint Act 2017 makes child marriages legal. The special rule proposes that underage females may be married off in “special contexts” with the permission of her parents or guardians in conjunction with a magistrate. Such a marriage is not considered an offense under Section 19 of the Child Marriage Restraint Act (2017).

Concerns reached a peak for the protection of female children after the Child Marriage Restraint Act was enacted. To save a female minor from harassment and to keep her out of sight of potential offenders, some village people marry off their daughters at an early age. As many as 59% of girls in Bangladesh were married off before they turned the age of 18 years. Also, 22% were married off before they reached the age of 15 years, according to UNICEF Bangladesh in 2017 (Haider Reference Haider2020). Though the Child Marriage Restraint Act mentions that a rapist cannot marry a minor victim; however, to save the reputation of the family, some rural people now make an excuse to marry off their underage daughters to their rapists by out-of-court settlement.

Ambiguity in Male Child Rape Law

Frequent reports on incidents of rape and sexual abuse of male children in madrasas and other places are a relatively new revelation. Though the Act of 2000 defines children as males and females, male child molestation cases mostly fall under Section 377 of the PC 1860. According to the section, whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman, or animal will be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term that may extend up to 10 years, and shall also be liable to a fine. Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary for proving the offense described in this section. An offender may receive any term of imprisonment not exceeding 10 years under this provision. The customary law addressing rape punishes vaginal penetration. The definition of rape protects women and girls alone. Therefore, the rape of male children falls under the PC 1860, and the offender receives a lesser degree of punishment than he would get under the Act of 2000.

In Abdus Samad (Md.) vs. The State, High Court Division Criminal Miscellaneous Suo Moto Rule No. 23508 of 2013, a madrasa teacher raped a boy of eight years. The offender was punished under Section 377 of the PC 1860 despite the presence of the Special Law of 2000. The High Court Division, in its motion, issued a rule that male child rape cases fall under Section 9(1) of the Act of 2000. Regardless of this ruling, cases are still filed under the PC 1860. In May 2018, a madrasa teacher raped a boy of 12 years, and the case was filed under Section 377 of the PC 1860 again (Magurarkhabor 2020). The offender was punished with three years of rigorous imprisonment, with a penalty that amounted to approximately USD 117 in 2020. Society is rather conservative when it comes to male child rape. The abused children generally come from disadvantaged sections of society and are silenced in the name of the “family’s honor.” The offense is mostly addressed behind closed doors through community-level settlement, where the chairman of the Union Council, which is a part of local government, pronounces punishments such as discharge from duty and minimum fines (Kalerkantho 2015). It is thus clear that both society and the criminal justice system are discriminatory when it comes to male rape victims.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As discussed above, the drawbacks of efficient child rape laws, the conservative judicial system, and societal norms are all responsible for the inability to effectively combat child rape. What follows are recommendations for defensive and precautionary measures to lessen and stop child rape.

From a Social Perspective

The author strongly recommends the establishment of a national mandatory reporting system to generate reliable data on child rape. NGOs and other organizations collect data from daily national newspapers. The data directly collected by the organizations working with child rights themselves are either not trustworthy or fail to portray the actual extent of child rape and unreported crime in the country. Therefore, we are badly in need of a national monitoring body to resolve this issue.

Bangladesh continues to reflect patriarchal perceptions. Bangladeshi society has normalized violence against women and children. As children are more vulnerable and physically weak, offenders choose them as targets. The United Nations Development Programme surveyed 2010 to 2013 and found that 82% of rural and 70% of urban Bangladeshi men who had committed the crime of rape felt entitled to rape. Further, 61.2% of urban men who committed rape did not feel guilty, and 91.5% faced no legal consequences (Fulu etal. Reference Fulu, Warner, Miedema, Jewkes, Roselli and Lang2013). The rape taboo, social stigma, men’s power over women, and the value of family reputation should be ignored. Only justice should be a priority. This can be accomplished through education; however, society as a whole must change its conservative approach to women and children by not considering them merely as sexual objects.

It is necessary to incorporate sex education and information on sexual and reproductive health rights, gender equality, and consent in school and madrasa textbooks and curriculums, as well as in teacher training programs. Society has to break its conservative approach to sex education, as it is still considered taboo to talk about sex-related issues.

Due to the conservative nature of society and lack of awareness of mental health issues, people are afraid to seek help for psychological problems. In the case of pedophilia, people are not ready to come forward and ask for help out of shame. Society should understand the nature of mental disorders and support those who suffer from them appropriately.

It is necessary to circulate the national hotline number for reporting violence against women, girls, and children (109) throughout the nation through print, electronic, and social media. Educational institutions should also conduct sessions on using these hotlines in case of sexual abuse.

From a Legal Perspective

There should be only one uniform legislation addressing child rape, irrespective of gender. Multiple laws will only lead to ambiguity and injustice and will increase the number of pending cases. The definition of rape needs to be amended. The age of consent should also be increased to 18 years.

“Marital rape” should also be adequately addressed by the law. After a salish (local justice system), rape victims are sometimes forced by family and community leaders to marry their attackers. Under no circumstances should a victim of rape be forced to marry the man who raped her.

A consideration of the degree of punishment should be introduced into child rape laws to ensure that the appropriate justice is administered. Bangladesh has few analytical provisions but provides harsh punishments in the form of life imprisonment, irrespective of the place of occurrence and the relationship between the victim and the offender. If several degrees of punishment are awarded, it will be easier for courts to pronounce judgments based on the elements constituting the crime. For example, punishment may vary according to the relationship with the offender. It may also vary by the nature of the act, such as penetration by a penis or by an object. Under Article 34 of the UNCRC, state parties should take national, bilateral, and multilateral measures to prevent child sexual abuse and exploitation. There should be separate legislation addressing only violence against children. Child rape, child sexual harassment, child trafficking, child prostitution, child pornography, and ensuring the rights of the child victims should be addressed together in one uniform law. Unfortunately, Bangladesh has failed to introduce a proper child sexual abuse law. Moreover, there should be separate tribunals only for children who have suffered sexual violence.

Pedophilia is a mental disorder, that is, a psycho-social disorder. Therefore, child sex abusers need proper psychiatric treatment. The therapeutic approachFootnote 1 should be inserted in the Jail Code, 2006, for the child sex offenders during the period of their detention in jail. By this psychotherapy treatment, rapists may not repeat the offense in the future and may feel repentant for their wrong actions (T.K. Gopal v. State of Karnataka, 2000, 3 Supreme 706). According to the Bangladesh Jail Code 2006, in every central jail, there should be a welfare officer, a psychologist, and a sociologist. In all district jails, there should be one welfare officer and one psychologist. There are provisions that call for the scientific classification of prisoners and their training and treatment based on prisoners’ psychological test results and criminal backgrounds before implementing measures for their reformation. Provisions have also called for assessing the success of rehabilitation and reformative programs in the post-release period. However, practical reality presents a different picture. The official capacity of the prison system of Bangladesh was 40,944 people as of February 2020. The total prison population (including pre-trial detainees/remand prisoners) was 88,084 as of February 2020, as confirmed by the Ministry of Home Affairs of Bangladesh (World Prison Brief 2020). These numbers make it clear that prisons in Bangladesh are holding nearly double their capacity. For such densely populated prisons, the presence of only one welfare officer, one psychologist, and one sociologist is not adequate at all. There are no programs for the post-release psychological treatment of child sex abusers.

Guidelines were issued by the High Court Division and the Supreme Court of Bangladesh in the case of Naripokkho and Others vs. Bangladesh (Writ Petition No. 5541 of 2015) to police personnel. These guidelines sought to make them aware of their duties concerning the recording of FIRs without any delay and referring victims promptly for medical examination. If a police officer refuses to make a complaint or behaves uncooperatively, immediate administrative measures are mandatory against such an officer. Fully trained female police personnel should be employed to handle victims’ cases with due diligence.

A gender-sensitive environment must be created by training judges and lawyers in order to guarantee proper delivery of justice.

On July 17, 2019, a High Court bench issued an order with six directives to the tribunals under the Act of 2000 and all district courts to complete rape trials within 180 days (Yeasin Reference Yeasin2020). Section 20 of the Special Act of 2000 clearly stipulates that trials must conclude within 180 days from framing the charge. If there is a delay, judges must submit a written explanation for the delay to the registrar general of the Supreme Court as per the Act of 2000. While hearing three separate bail petitions filed by alleged rapists from rape incidents in Dhaka, Noakhali, and Bogura, the bench stated that tribunal judges had continuously failed to submit their reasons for not concluding the trials on time (Moneruzzaman Reference Moneruzzaman2019). Moreover, the bench also directed the authorities to form a monitoring committee in every district to ensure the presence and security of witnesses (Moneruzzaman Reference Moneruzzaman2019). The bench also directed that, if any official witness such as a magistrate, doctor, police officer, surgeon, or other expert failed to appear before the tribunal without satisfactory reasons, departmental action would be taken against them. Therefore, it is evident that the High Court is directing authorities and lower courts to conduct speedy trials; however, due to legal loopholes, lack of witnesses, inadequate physical evidence, and delays in framing charges, rape cases linger and are not disposed of. Hence, the Ministry of Law should take immediate measures to implement the directives given by the High Court.

A witness protection program is mandatory. Otherwise, rape cases will remain pending for extended periods of time because of the absence of witnesses.

CONCLUSION

Child rape has been addressed through social, cultural, and legal perspectives in Bangladesh, which has enacted laws and has even imposed extreme punishments on offenders. Despite this, the situation remains pitiful. Society should not treat the discussion of rape as taboo, nor should it accept cultural violence by any means. Instead, society must strive to enhance awareness through textbooks, television programs, and social media posts in order to address the crime. The Ministry of Law should strive to abolish several similar laws and create a compact, effective, and uniform legislation to address child rape. The criminal justice system should address child rape cases with utmost diligence and sincerity. Offenders with mental disorders should be treated accordingly not only through mere textual provisions of the law but also through effective psychiatric treatment. At present, because of overcrowded prisons, an adequate number of psychologists and sociologists should be appointed to conduct appropriate psychological welfare programs. The knowledge of child rape and child safety measures should be disseminated to children from an early age both by their families and educational institutions so that they can report incidents to those near and dear to them quickly.

It cannot be denied that a society cannot be changed in a day. However, laws alone cannot prevent such inhuman crimes; instead, the perspective of the society must also be gradually changed. The article is unable to analyze the patterns of crime, actual crime rates, and information about filed child rape cases because of minimal resources. The websites that contain cases of child rapes in Bangladesh are not updated; therefore, it is difficult to find appropriate cases online. Examining the social context theories of criminology and victimology may play a vital role, which could be subject matter for research in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research paper has been a journey and undertaking, and I have found it an enriching experience. I would like to thank everyone who advised, encouraged, and supported me along the way. Notably, I would like to thank the International Society of Criminology. Having been given the opportunity to present my paper at the 19th World Congress of the Society, I was inspired to work on this issue. I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Mr Mahbubur Rahman, chairperson of the BSAF, for allowing me to use their statistical data related to child abuse in Bangladesh. I also thank the editor of the International Annals of Criminology, Professor Emilio C. Viano, for his encouragement, guidance and editorial comments, suggestions, and recommendations. Finally, I express my deepest gratitude to my parents for their inspiration, patience, and love.

Monira Nazmi Jahan is a senior lecturer in Law at East West University, Bangladesh. In addition, she is an enrolled advocate in the Dhaka Judge Court and a member of the Bangladesh Bar Council. She completed her LL.B. Honors from BRAC University, Bangladesh, and LL.M from Rajshahi University, Bangladesh, as well as a specialized master’s degree in Criminology and Criminal Justice from the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The author has presented several papers at international conferences and national stages. She is a regular columnist to numerous popular newspapers in Bangladesh and on international platforms.