Introduction

Nasal foreign bodies are frequently encountered, particularly in children. Most nasal foreign bodies are deliberately inserted by the child, while a few are accidental. A foreign body can become trapped or incarcerated in one or both nasal cavities via the anterior (vestibular) or, more rarely, posterior (choanal) route.Reference Abou-Elfadl, Horra, Abada, Mahtar, Roubal and Kadiri1

An inserted object that is not witnessed or retrieved can either remain relatively asymptomatic or can cause local tissue damage and potentially yield more serious consequences. Positive diagnosis is often easy, but may be delayed by the type of foreign body or non-specificity of the symptomatology. Early diagnosis can prevent potentially serious complications related to the nature of the foreign body itself and a real risk of superinfection.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

The study protocol, including access to and use of medical records, was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Yiwu Central Hospital, China.

Case selection

The clinical records of children with nasal foreign bodies, who presented to the Otolaryngology Outpatient Clinic in Yiwu Central Hospital, China, between January 2014 and December 2017, were accessed through the Records Department of the hospital.

The data for cases that met the following inclusion criteria were retrieved for analyses: nasal foreign bodies in children; intact clinical data and demographic data, including age, sex, condition duration, nasal cavity side, foreign body location within the nasal cavity, foreign body type, nasal symptoms, and therapeutic method; and non-iatrogenic foreign bodies. Cases with inadequate documentation of clinical data were excluded.

Procedures

Anaesthesia type was chosen based on the child's age and cooperativeness. Nasal cavity secretions were removed using suction. The nasal cavity was then sprayed 2–3 times every 5–10 minutes using lidocaine with adrenaline, to reduce bleeding and improve visualisation.

Various types of equipment were selected and utilised based on the type and nature of the nasal foreign body, and related complications. For example, suction was used for paper scraps and vegetal forms, nasal forceps were used for soft and non-breakable nasal foreign bodies, while a cerumen hook or custom-made hook was used for hard and non-breakable nasal foreign bodies. Most of the nasal foreign bodies could be extracted with the aid of a hand mirror; however, the use of an endoscope should be considered for nasal foreign bodies in the upper nasal cavity.

With the child in a sitting position, the head, hands and feet should be held tightly, and the head should be angled slightly backward or looking straight ahead to afford a clear view of the type and position of the nasal foreign body. The head should be kept angled downward to prevent the nasal foreign body from falling into the nasopharynx from the posterior nares. In non-cooperative children, the head should be angled downward slowly with the mouth shut, to prevent the nasal foreign body reaching the nasal vestibule and entering the oropharynx. Finally, secondary granulation tissue and rhinoliths should be cleaned carefully.

Oral amoxicillin and 0.5 per cent ephedrine were administered to all children for 3 days, and 0.9 per cent saline nasal drops were prescribed for 1 week. In addition, physiological seawater nasal spray was prescribed for three months in cases involving button batteries.

Follow up was scheduled at one week, except in cases with button batteries, which were scheduled at two weeks, four weeks, three months and six months. Foreign body and treatment-related complications (including synechiae formation, necrosis, ulceration and nasal septum perforation) were evaluated at each visit.

Results

In total, 341 cases met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The average patient age was 3.7 ± 1.2 years (range, 1–19 years). For one patient, a lead pencil refill was put into the nasal cavity at 6 years of age but not treated until 19 years of age; thus, the patient was included in this study. A total of 247 cases (72.4 per cent) involved the right nasal cavity and 83 (24.3 per cent) involved the left, while 11 cases (3.3 per cent) involved both cavities. Of the patients, 211 (61.9 per cent) were male and 130 (38.1 per cent) were female. Incidents of nasal foreign body were reported by: a family member or teacher in 113 cases (33.1 per cent), the child themselves in 78 cases (22.9 per cent), and a schoolmate or playmate in 11 cases (3.2 per cent); 139 cases (40.8 per cent) were discovered incidentally when treatment was sought following the onset of nasal symptoms.

The distribution of patient age and nasal foreign body type are shown in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2. All the bilateral nasal foreign bodies were paper scraps or melon seeds. The diagnosis of nasal foreign body was made based on a physical examination in 312 patients, while X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scans were utilised in 29 cases. The positions of the nasal foreign bodies are shown in Table 2, and the symptoms and signs at the initial visit are shown in Table 3. Figures 3 and 4 respectively show bead and bean nasal foreign bodies in two children.

Fig. 1. Distribution of patient age.

Fig. 2. Distribution of nasal foreign body type.

Fig. 3. A bead had remained between the inferior turbinate and the septum for 8 years in a 12-year-old girl. (a) Endoscopic examination showed the nasal foreign body with rhinolith (arrow). (b) Image of the bead after excision of the rhinolith. (c) The outer diameter of bead is 5 mm.

Fig. 4. A five-year-old boy with purulent secretion of left nasal cavity. (a) A purulent block mass (asterisk), following the suction of purulent secretion, was observed in the posterior naris. (b) Image shows a bean foreign body (arrow).

Table 1. Distribution of patient age and nasal foreign body types

Data represent numbers of cases, unless indicated otherwise. *Including melon seeds, a peanut, beans and peas; †including a rubber, lead refill and sponge; ‡including sweets and crisps; **including jewels, beads and tiny toy part

Table 2. Foreign body location within nasal cavity

Table 3. Symptoms and signs of nasal foreign bodies at initial visit

Of the nine cases with button batteries, patient age ranged from four to six years. Seven button batteries were from toys, while two were from other electronic devices. The most common symptoms were brown secretions with traces of blood, followed by unilateral nasal obstruction and local pain. Septal perforation was seen in four cases at the initial visit. The time between insertion and removal was 2 days in three patients, 3 days in five patients, and 4 days in one patient.

In all 341 cases, the nasal foreign bodies were successfully extracted at the initial visit; they were removed under general anaesthesia in 28 cases (8.2 per cent) and with local anaesthesia in 313 cases (91.8 per cent).

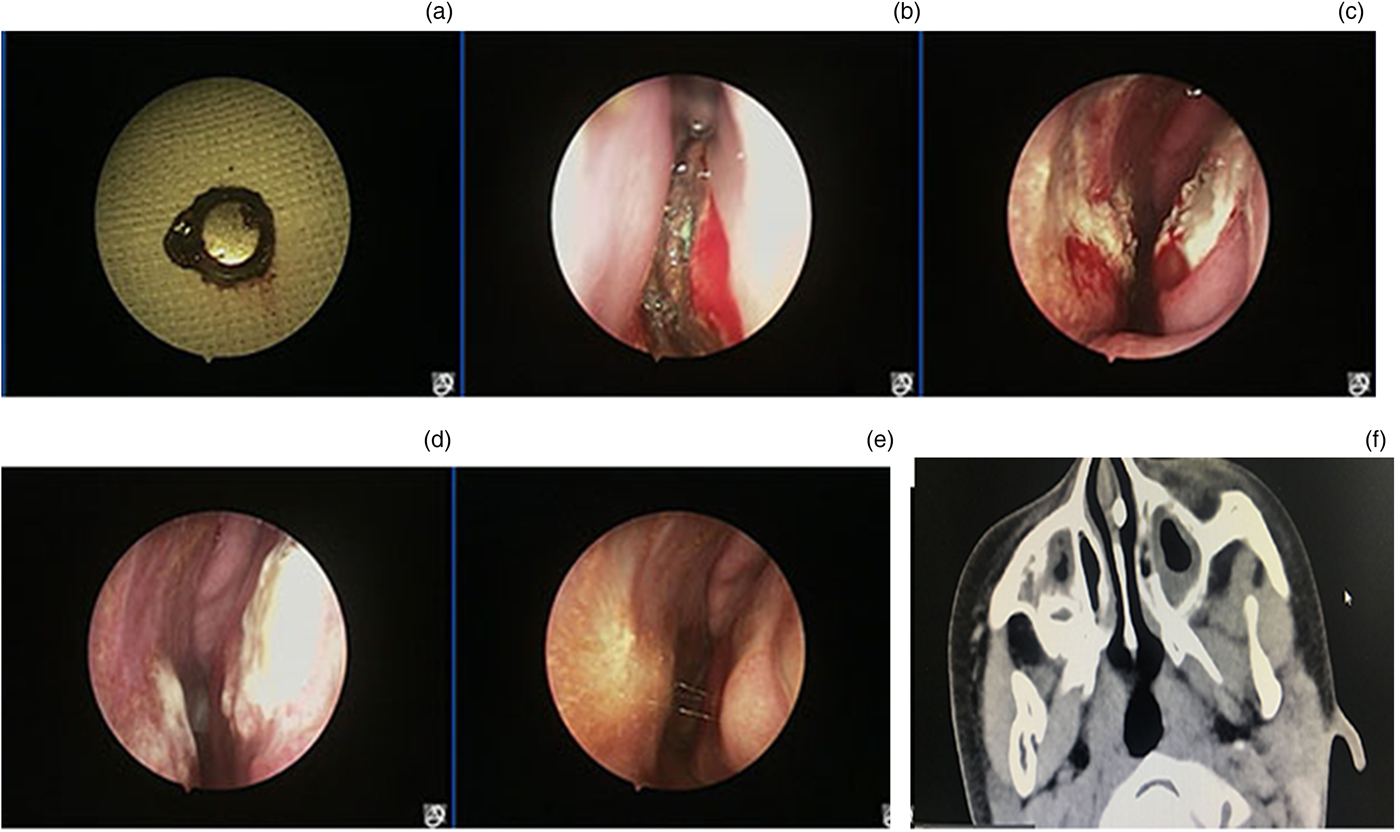

Nasal mucosa was damaged in 113 cases involving removal with a hook (33.1 per cent). In all nine cases involving button batteries, the nasal foreign bodies were removed under local anaesthesia. At the one-week follow up, nasal septal ulceration was observed in all nine cases with button batteries. With the exception of 4 pre-existing septal perforations, no severe complications (including synechiae formation and septal perforation) were observed in the remaining 337 cases. At the four-week follow up, three cases involving button batteries without the use of physiological seawater nasal spray developed septal perforations, while the two patients using the nasal spray did not (Figure 5). In total, seven cases involved septal perforations. At the three- and six-month follow-up appointments, the number of septal perforations did not increase. Of the seven patients with septal perforations, all perforations were on the chondroseptum, with the size of the perforation being similar to the size of the button battery.

Fig. 5. A 4-year-old child with a button battery nasal foreign body (a). Endoscopic images from: (b) 2 days, (c) 2 weeks, (d) 3 weeks and (e) 2 months after extraction. (f) Computed tomography showed a white mass between the inferior turbinate and the septum.

Discussion

Nasal foreign bodies in children are commonly encountered in the emergency department. Previous studies have shown that the most common age of patients diagnosed with a nasal foreign body is two to five years.Reference Abou-Elfadl, Horra, Abada, Mahtar, Roubal and Kadiri1–Reference Claudet, Salanne, Debuisson, Maréchal, Rekhroukh and Grouteau3 The current study showed similar age characteristics. Nasal foreign bodies mainly occurred in the right nasal cavity; this could be related to the fact that most foreign bodies are inserted into the nasal cavity by children themselves and that most people are right-handed. The results of this study, and those of previous studies, suggest that the type of nasal foreign body is related to the child's age. Older children are more likely to have access to electronic products, thereby increasing the risk of button battery nasal foreign bodies.

Unilateral nasal obstruction was the most common symptom at the initial visit, followed by blood traces and unilateral mucopurulent secretion, which were often overlooked by parents and children. A fetid smell with mucopurulent secretion is characteristic of a perishable foreign body, including pieces of paper, vegetal forms and sponges. It is noteworthy that some hard and non-perishable foreign bodies remained in the nasal cavity without any symptoms for many years, thereby resulting in the formation of granulation tissue and rhinoliths. In this study, the longest time between insertion and removal of a nasal foreign body was 15 years. Other scholars have reported nasal foreign bodies persisting in the nasal cavity for 35–50 years.Reference Derosas, Marioni, Brescia, Florio, Staffieri and Staffieri4–Reference Pitsinis and Patel6 In addition, 9.1 per cent of our patients complained of a headache, which may suggest that the nasal foreign body was located between the superior turbinate, middle turbinate and nasal septum.

• Most nasal foreign bodies were in the right nasal cavity; only a few cases involved the left and bilateral cavities

• Vegetal forms were the most common nasal foreign body type

• The most common symptom was unilateral nasal obstruction, followed by mucopurulent secretion and fetid smell

• Most nasal foreign bodies may be successfully extracted at the initial visit under local anaesthesia, without severe complications

• Button batteries increased the possibility of septal perforation; however, physiological seawater nasal spray appeared to reduce this likelihood

In this study, septal perforation was observed in seven of the nine patients with a button battery nasal foreign body. The mechanism by which a battery can cause septal perforation is unclear. Four mechanisms of injury have been suggested: leakage of the battery contents with direct corrosive damage; direct electrical current effects on the mucosa and resultant mucosal burns; pressure necrosis; and local toxic effects.Reference Thabet, Basha and Askar7,Reference Loh, Leong and Tan8 Some scholars have suggested that if mucosal damage is present, the likelihood of septal perforation may be related to the time interval between insertion and removal.Reference Guidera and Stegehuis9,Reference Mackle and Conlon10 Four of the seven septal perforations were evident at the initial visit while three presented at follow up. Interestingly, of the five patients without septal perforations at the initial visit, the two using nasal spray did not develop septal perforations, while the other three subsequently developed septal perforation within four weeks. As the button battery is alkaline and seawater nasal spray is weakly acidic, we speculate that the seawater may prevent septal perforation by neutralising the toxic effects of the button battery. Nevertheless, our sample size was very small, and the question of how to prevent septal perforation requires further study.

The diagnosis of nasal foreign bodies was not difficult in our cases. The nasal foreign bodies were definitively diagnosed via direct visualisation, following the suction of nasal secretions and application of lidocaine with adrenaline, in 312 patients. X-ray or CT imaging was required in only 29 patients. Thus, radiological evaluation is not necessary for most nasal foreign bodies.Reference Oh, Min, Yang and Kim11

The extraction of nasal foreign bodies was also straightforward. Nasal foreign bodies should be removed using the relevant appropriate equipment (including suction devices, hooks and forceps), based on the foreign body type, to avoid complications during extraction. Proper technique can prevent nasal mucosal lesions and stop the foreign body from falling into the oropharynx and trachea. All nasal foreign bodies were successfully removed in this study, and no severe treatment-related complications, including synechiae formation and nasal septal perforation, were observed.

Conclusion

The type of nasal foreign body in children was related to age, and the diagnosis of most nasal foreign bodies was mainly dependent on nasal cavity examination. Only button batteries increased the possibility of septal perforation; however, the use of physiological seawater nasal spray appeared to reduce the likelihood of septal perforation. Proper technique can prevent nasal mucosal lesions and stop the nasal foreign body from falling into the oropharynx and trachea during extraction.

Competing interests

None declared