Introduction

Population ageing has prompted many countries to develop social-care policies focused on enabling older people to maintain independence for as long as possible (Hokenstad Reference Hokenstad, Hokenstad and Kendall1988; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Xie, Reilly, Hughes and Challis2009; Tsutsui and Muramatsu Reference Tsutsui and Muramatsu2007). At the same time in Western countries, availability of informal support in the community has diminished due to falling birth rates, greater geographical mobility and higher levels of female employment, increasing risks of social isolation and loneliness among vulnerable older adults (Grundy Reference Grundy2006).

The importance of tackling social isolation and loneliness to improve older people's wellbeing and quality of life is increasingly recognised in international policy (World Health Organization 2002). In England, a recent report by Age Concern (now Age UK) identified 1.2 million older adults as ‘feeling detached from society; trapped at home; cut-off from services; lonely and isolated’ (Yates et al. Reference Yates, Harrop, South and Spinney2008: 2). Risk factors for sustained social detachment include: age (80 and over), living alone or in residential care, few or infrequent social contacts (particularly an absence of local kin), poor health, and impaired sensory or cognitive functioning (Wenger Reference Wenger1997). Given that the proportion of the population aged 85 and over in the United Kingdom (UK) is set to double to 3.2 million by 2033 (Tomassini Reference Tomassini2006), social isolation and loneliness in older adults are a growing problem.

Loneliness can be described as a lack of satisfying social relationships and is known to affect both physical and mental health (Griffin Reference Griffin2010; Heinrich and Gullone Reference Heinrich and Gullone2006). Loneliness is a strong predictor of depression, poor health outcomes and increased rates of cognitive decline among older adults (Luanaigh and Lawlor Reference Luanaigh and Lawlor2008). Both chronic and more recent onset loneliness increase risks of mortality (Patterson and Veenstra Reference Patterson and Veenstra2010). Loneliness is associated with higher rates of primary health-care consultations (Ellaway, Wood and Macintyre Reference Ellaway, Wood and Macintyre1999).

Statutory health- and social-care services for older adults in the community are not primarily focused on preventing or alleviating loneliness. Rather, this has traditionally been the remit of community and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which seeks to foster and maintain social relationships through schemes like befriending (often referred to as ‘friendly visitor’ or ‘senior companion’ programmes in the United States of America (USA)).

Befriending has been defined as:

a relationship between two or more individuals which is initiated and supported and monitored by an agency that has defined one or more parties as likely to benefit. Ideally the relationship is non-judgmental, mutual, and purposeful, and there is a commitment over time. (Dean and Goodlad Reference Dean and Goodlad1998: 13)

Befriending services are part of the social landscape in many countries, particularly the USA, Canada, Australia and Europe. They have been offered to older adults in the UK for over 70 years (Salvage Reference Salvage1998: 36), and are increasingly perceived as central to healthy ageing strategies, through the prevention of social isolation and loneliness (Cm 7655 2009; Department of Health 2010; Godfrey Reference Godfrey2001; McCormick et al. Reference McCormick, Clifton, Sachradja, Cherti and McDowell2009).

The ‘effectiveness’ of befriending

An overview of interventions that target social isolation among older adults concluded that there was little evidence that they worked (Findlay Reference Findlay2003). The lack of evidence may have been because the review considered a small number of both quantitative and descriptive studies that targeted socially isolated older people, not specifically the alleviation of social isolation. A more recent systematic review of the effectiveness of health promotion interventions targeting social isolation and loneliness among older people found that nine of the ten effective interventions were group activities with an educational or support input. The evidence regarding one-to-one interventions, such as home visiting or befriending schemes, was less clear (Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005).

The link between loneliness and mental health means that befriending is increasingly situated within the broader context of ‘psycho-social interventions’ alongside psychological therapies (Griffin Reference Griffin2010). Although befriending has been evaluated in controlled trials, the evidence base for its efficacy on mental and physical health outcomes is relatively limited. Our recent systematic review identified 24 trials of one-to-one befriending interventions, and found a small but significant overall reduction in depressive symptoms across a range of populations (Mead et al. Reference Mead, Lester, Chew-Graham, Gask and Bower2010). Not all studies reported positive findings, including those targeting older adults (see Charlesworth et al. Reference Charlesworth, Shepstone, Wilson, Reynolds, Mugford, Price, Harvey and Poland2008; Onrust et al. Reference Onrust, Smit, Willemse, van den Bout and Cuijpers2008). Inconsistencies may be partly explained by variability in methodological quality, population characteristics and befriending interventions. Contradictory findings may reflect current lack of understanding of the mechanisms by which befriending facilitates emotional wellbeing.

The mechanisms of befriending

No overarching theory of how befriending works currently exists. However, studies have shown that social relationships confer both mental and physical health benefits (House, Landis and Umberson Reference House, Landis and Umberson1988) and various pathways have been proposed, focusing on different properties of the social environment. The key concept in the relevant literature on social relationships is social support which has both structural and functional characteristics. The former concerns the number and connectedness of social ties, the latter refers to provision of resources, for example, instrumental support, information and advice, or emotional support (House, Umberson and Landis Reference House, Landis and Umberson1988). There is some debate as to whether social support improves mental health by ameliorating the psychological effects of stressful experiences (the ‘stress buffering’ hypothesis) or whether it is beneficial regardless of pre-existing stress (the main effect hypothesis) (Cohen Reference Cohen2004). However, a key assumption underpinning much empirical work in this area is that providing individuals who have deficient social networks with additional enacted support (such as a befriender) will increase their perceived social support (Brand, Lakey and Berman Reference Brand, Lakey and Berman1995).

Although there is strong evidence that perceived social support is associated with psychological wellbeing (Cohen and Wills Reference Cohen and Wills1985), our recent systematic review found no evidence that the reduction in depression symptoms is mediated through increases in perceived social support, at least, as assessed by standardised questionnaires (Mead et al. Reference Mead, Lester, Chew-Graham, Gask and Bower2010).

Previous studies of befriending have highlighted the importance of ‘matching’ befrienders with befriendees on key characteristics like demographics and life experiences (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003; Dean and Goodlad Reference Dean and Goodlad1998). Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Newell, Bond and White2003) suggest that older people emphasise the need for reciprocity in social support, which is more likely to occur when the volunteer visitor and the ‘service recipient’ belong to the same generation, have common interests, and share a common culture and social background. Interpersonal similarity may increase propensity for attachment and bonding, improving mental health outcomes through the mechanism of ‘empathy’, regarded as a key ingredient of psychotherapeutic relationships (Davis Reference Davis1990).

According to Cohen (Reference Cohen2004) different social variables (such as social support or interpersonal similarity) influence health through different, probably independent pathways. For this reason, the multilevel, multi-dimensional model of how social networks impact on health proposed by Berkman et al. (Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000) may be the most useful framework within which to explore potential mechanisms of befriending. The model is particularly noteworthy for assimilating socio-structural conditions and psychological mechanisms. It incorporates four levels: social-structural conditions (macro), which influence the structural and functional make-up of individuals’ social networks (mezzo), which in turn provide opportunities for psycho-social mechanisms (micro) which impact on health through behavioural, psychological and physiological pathways (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Berkman and colleagues's model linking social networks to health.

Berkman et al. (Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000: 846) propose five types of psycho-social mechanisms by which health may be affected, often operating simultaneously. Along with (a) social support, networks provide opportunities for: (b) social influence (on health-related behaviours); (c) social engagement, participation and fulfilment of roles; (d) regulation of contact with infectious disease, and (e) access to material goods and social resources (including health care). These micro-psychosocial and behavioural processes then influence even more proximate pathways to health status including: (a) direct physiological stress responses; (b) psychological states and traits, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, security; (c) health-damaging behaviours, such as tobacco consumption or high-risk sexual activity, and health-promoting behaviour such as appropriate health service utilisation, medical adherence, and exercise; and (d) exposure to infectious disease agents.

In light of the potential importance of befriending as a preventive health strategy for older adults, and lack of clarity concerning underpinning mechanisms, this study aimed to explore service users' experiences of befriending using the model proposed by Berkman et al. (Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000) as a potential explanatory framework for the data. A better understanding of how befriending works may help health and voluntary- and community-sector providers develop better targeted and more effective interventions (Medical Research Council 2000).

Methods

In line with the earlier definition, we focused on a simple ‘being with’ model of befriending, providing emotional support rather than instrumental help with tasks such as cleaning or shopping (Dean and Goodlad Reference Dean and Goodlad1998). This definition was employed in our systematic review and by the majority of the older adult befriending services we contacted.

The national policy unit of Age UK nominated two face-to-face and one telephone befriending service as examples of good practice. We additionally purposively recruited two non-Age UK services befriending people living in intermediate and residential care, to explore issues concerned with befriending in different settings. These five services were in four geographically diverse areas of England (Newcastle, Birmingham, Oxfordshire and the Mid-Mersey region).

Befriending was undertaken by unpaid volunteers matched with befriendees, where possible, on issues such as gender, interests and assessments of personality ‘fit’. All services delivered befriending on an open-ended basis. Contact was usually weekly (one to three hours duration for face-to-face, and 10–20 minutes by telephone). We asked service co-ordinators to nominate people of different ages and genders who might want to participate. The topic guide was generated from a priori questions arising from our systematic review, and modified as the study progressed. Interviews explored older adults' views of befriending and befrienders, including positive and failed relationships. No formal measures were used, but interviewees were asked about their health, including current and previous episodes of depression. Interviews were carried out by N.M. (a health services researcher) or H.L. (a General Practitioner and health services researcher) in interviewees' place of residence, between March and October 2009. Interviews, which were recorded and fully transcribed with participants' consent, lasted on average 60 minutes (range 20–120). Approval was obtained from the University of Manchester ethics committee.

Analyses combined deductive and inductive principles. We examined interviewees' accounts for confirming and disconfirming evidence relating to social support and ‘matching’ as key ingredients of successful befriending, while seeking alternative explanations through the application of Charmaz's modified constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz Reference Charmaz1990, Reference Charmaz2006). Constant comparison across transcripts identified themes using an iterative process in which codes that developed based on analysis of one transcript were applied to another to either validate or expand the coding scheme (Ryan and Bernard Reference Ryan and Bernard2003). Comparison occurred throughout data analysis, across respondents and sites so that interpretations were constantly scrutinised and refined. We began with initial coding after studying each transcript line by line. Initial and then more focused codes were gathered together and described, and verified by other members of the research team. Coding then became more focused, moving from using coding as a descriptive tool to using it help synthesise the data. This led to the development of analytical and finally core categories. Interviewing continued until no further themes emerged and data saturation was reached. Quotations are representative and illustrative rather than exhaustive.

Results

Demographic and health characteristics

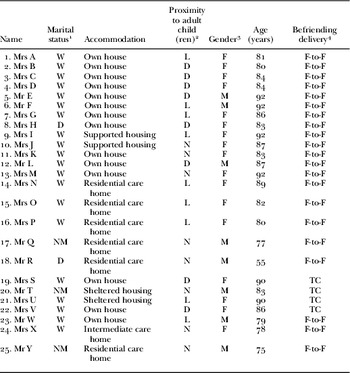

Twenty-five older adults across the five different befriending services were interviewed (see Table 1). Mean age of interviewees was 83.5 years (median 84; range 55–92 years)Footnote 1; eight were male. Twenty-one described experiences of face-to-face befriending while four were telephone service users.

Table 1. Study sample characteristics

Notes: 1. W: widowed; D: divorced; NM: never married. 2. L: local (perceived by interviewee); D: distant; N: no (surviving) children or no contact. 3. F: female; M: male. 4. F-to-F: face-to-face contact; TC: telephone contact.

All interviewees had at least one long-term physical health problem and most had multiple morbidities. The majority were unable to leave their homes without support. Of the 16 who lived alone in their own homes or warden-monitored sheltered housing, four received daily assistance from a paid carer. Others reported paying for help with cleaning or gardening. Five interviewees were currently being treated for mental health problems (mostly depression); a further seven reported past mental health difficulties, often related to bereavements.

Social network structure

All interviewees were unpartnered, the majority being widowed (Table 1). Eleven interviewees had a son/daughter or sibling living relatively locally, although only eight saw their family member on a regular basis. Among those living alone, this contact was usually weekly and was primarily task-focused (such as assisting with shopping). Six lived some considerable distance from all their adult children (indeed in three cases, the only child lived abroad). The remaining eight had no (surviving) children or were permanently estranged. Contact with the befriending service had usually been initiated by a relative or professional, often following spousal bereavement or a period of hospitalisation.

Five themes emerged: the first, ‘the context of loss’, described a core experience of all respondents which shaped the difficulties they faced and the social environments in which they were situated. The second described particular characteristics of network ties in befriending relationships. The other three themes related to mechanisms by which befriending ameliorated those difficulties: ‘(emotional) social support’, ‘connectedness’ and ‘maintaining a positive self-concept’.

The context of loss

The impact of befriending on interviewees’ lives was framed by their experience of ageing as an extended period of loss: of important relationships, social roles, responsibilities and status, physical and cognitive functioning, independence, and for some, loss of the family home. An elderly widow described her losses in the following terms:

You lose everything when you move house at 85. Especially when you're losing your sight because you have to change your entire life, ‘cos all the things you used to do like reading a book, and walking, and sewing and knitting and all these things you can't do. Yes, I was in a terrible state when I first came here. (Mrs I)

Such repeated losses continually shaped and re-defined the structure and characteristics of networks within which interviewees were embedded, with negative consequences for emotional wellbeing as this widower describes:

They're [ex-colleagues] gradually dying off, you know? Well this is the point … F [wife] was six years younger than me – I didn't expect this to happen. I have two brothers, an older one and a younger one – they're both gone. Parents obviously gone, uncles, cousins have disappeared. I'm forever going to funerals you know. It's tough … I'm very much becoming isolated. (Mr L)

As noted previously, most interviewees were largely housebound. Many regarded daily life as monotonous, had few meaningful contacts and felt ‘trapped’ in their homes. This elderly widow had not been out beyond her garden gate for many months:

You can go weeks without speaking to anyone. I don't see my neighbours – they are nearly all new neighbours and younger than me, and you see most people work now don't they? So everybody's out doing something … If you don't go out, by the end of the day in the house you look at it and you think ‘this place is making me scream’. (Mrs B)

Interviewees often had a radio or television on in the background ‘for company’, and many referred to the central importance of the telephone for maintaining contact with remaining friends and family. For example, this lady explained how the noise of her television was a constant companion:

In these four walls it seems … everything's so quiet. I put the telly on. I might not want to see what it is, but it's just the noise … company, it's a sound going, you know, that there's life there sort of thing, you know? (Mrs U)

Characteristics of network ties

Reciprocity and sharing intimacies

Berkman and colleagues’ model stresses the importance of the extent to which social exchanges or transactions are even or reciprocal. The notion of reciprocity and shared intimacies was clearly important to many of the interviewees. Despite being essentially a monitored relationship, created with the specific purpose of benefiting the older person, for many interviewees, as the gentleman quoted next describes, befriending had become ‘like a friendship’.

I enjoy his company and he enjoys mine, I think … I feel as though he is a friend rather than a voluntary worker. (Mr E)

Interviewees emphasised how their befriender benefited, for example through sharing food and drink, or advice on domestic and relationship issues. Mrs M used to work in a fabric department of a large department store and was keen to pass on her knowledge:

She's asked me about curtains. She lives in a big house – a Victorian terraced house – she's got as far as the curtains and she's not very experienced with this so she's asking me. (Mrs M)

These demonstrations of reciprocity can be seen as a means of affirming self-worth and autonomy: the interviewees strived to present themselves as equal partners in an interdependent relationship rather than recipients of a service.

In contrast, past unsuccessful befriending relationships, described by four interviewees, were perceived to have been non-reciprocal in nature. In these relationships the befriender talked rather than listened, and was felt to lack interest in the interviewee and their life stories. It is noteworthy that none of the befriendees actively asked for the befriender to stop calling and all asked for a new befriender when the original person stopped visiting.

There was evidence that face-to-face befriending may be more amenable than telephone befriending to developing reciprocity in the relationship, the latter perhaps having more in common with ‘friendliness’ than friendship since it ‘involves a restricted conviviality which flourishes by carefully respecting each party's right to preserve the privacy of the back stage realm’ (Bulmer Reference Bulmer1986: 96). However, telephone befriending still provided some opportunities to develop elements of ‘friendship’ through the sharing of intimacies as Mrs V describes:

It is more difficult in a way, but I mean, after you have been talking to somebody for quite a while you sort of get to know them. I feel like, if she came to the door, I would sort of, as soon as she spoke, I would know her straight away and I would feel friendly towards her – because we are on friendly terms on the phone. (Mrs V – on telephone befriending)

In general, telephone befriending was seen as distinct from face-to-face support in terms of shorter duration of contacts, the tendency to involve more than one befriender per interviewee, and greater emphasis on the notion of checking-up rather than developing a meaningful friendship. It did, however, have the advantage of being more in the control of the befriendee (for example, the ability to curtail the call) which may link to issues of autonomy. These elements were particularly important to Mrs S:

I wasn't worried about it – I thought, if you're at the other end of the phone, you can always slam it down … It's someone keeping an eye on you. (Mrs S)

This is in contrast to a recent study, which found that the service helped some older people to gain confidence, gain a friend, re-engage with the community, feel safer and become socially active again (Cattan, Kime and Bagnall Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2010).

Homogeneity

It was not important that befrienders had ‘shared experience’ of problems associated with ageing such as ill health, bereavement or loneliness. All interviewees were significantly older than their befrienders (age differences ranged from 20 to 60 years), and some reported actively avoiding contact with peers, such as invitations to attend day centres, as they felt little in common with ‘old people’. Mrs M was a particularly sprightly 92-year-old lady who was adamant that she preferred talking to younger people than older adults:

I didn't want an old person because I haven't got an old mind you see. I can't sit with a lot of old people. (Mrs M)

Interviewees, however, did regard it as important to have ‘things in common’ with befrienders, in keeping with Berkman and colleagues’ observation of the importance of homogeneity – the extent to which individuals are similar to each other in a network. Yet, perceived commonalities more often seemed to arise as the result of successful befriending relationships rather than being a necessary precursor. Cited examples could be as obvious as a shared hobby, but frequently involved more tenuous connections like family links to the same part of the country, or a shared dislike of the same film.

She's absolutely the double of me … Well she comes from Yorkshire and my father was a Yorkshire man. Everything she seems to do seems to be what I've got. You know, I say: ‘I've got a new one’ and she says: ‘Oh I've got one of them’. She's just perfect … We seem to eat the same things and everything. (Mrs M)

Interpersonal bonding therefore appeared to be determined by interviewees' perceptions of the befriender's personal qualities rather than whether they had a similar background or interests. They wanted a befriender who was ‘friendly’, one who could talk animatedly yet was also ‘a good listener’, someone they could trust who seemed genuinely interested in them.

This resonates with findings from a randomised trial of telephone peer support between pairs of isolated elderly women, in which similarity in social competence (that is, conversational skills and the ability to express empathy) was a stronger determinant of friendship continuance after the trial finished than was similarity in background or personality (Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb1991).

Psycho-social mechanisms: social support

Having a befriender did not appear to increase respondents' perceptions of the social support available to them in times of need. Most identified a relative, neighbour or long-standing friend as someone they would call on rather than their befriender. Reasons reflected the desire not to be a ‘burden’ given that befrienders were unpaid volunteers and had work, family and other commitments outside their befriending role. Unspoken understandings of ‘mutual obligations’ underpinned certain relationships (e.g. with adult children and professionals) but not those with befrienders. Mr E was keen to emphasise this point:

I think the first thing I would do, um, I would call S [daughter in USA]. Then I would call V's partner up the road [84-year-old brother-in-law] … because you call the family first, don't you, naturally. And also, I've got a good neighbour on this side here. (Mr E)

The regularity and reliability of befriender contact was highly valued, especially compared with friends and family who could ‘let you down’. Yet the scheduled aspect of befriending placed clear boundaries around it as a support resource, in contrast with the more spontaneous and flexible nature of relationships with family and friends.

Although services discourage volunteers from giving out personal contact details, most interviewees had their befriender's telephone number but stressed they would not call them just to ‘chat’ or make ad hoc requests for assistance as Mrs D describes:

I wouldn't ring her to, um, have a big problem, but I can have a word with her on the phone if I want. I phoned her to tell her not to come when it was snowing. (Mrs D)

In the Berkman model (Figure 1) ‘reachability’ is part of the ‘mezzo’ structural nature of support networks. However, as noted earlier, social support has structural and functional characteristics. For many respondents, a key function of befriending was the opportunity to confide and receive emotional support: effectively providing a ‘safe context’ for dealing with loss.

Age-related losses gave rise to feelings of frustration, lack of motivation, depression, vulnerability and loneliness. Particularly difficult for those with adult children was the loss of their parental role in the reversal from ‘carer’ to ‘cared for’. Interviewees strived where possible to minimise ‘burden’ and maintain balance in relationships with their children (e.g. continuing to provide financial or emotional support), while simultaneously minimising their own distress. As someone relatively ‘distant’ and unbiased, the befriender could be confided in without fear of burdening loved ones or causing tensions in relationships if children failed to respond with support. As Mrs V, who had a number of long-term physical health problems, pointed out:

They'll say ‘ How are you mum?’ and I'll go ‘Oh, the catheter is out again’, but I don't make a big thing of it because it isn't fair when they're all those miles away for them to think that I'm either not well or unhappy. (Mrs V)

In her seminal study of the social origins of depression in the elderly, Murphy (Reference Murphy1982) identifies lack of a confiding relationship is key vulnerability factor, observing that a confidante ‘can act as a buffer against social losses’. Berkman et al. (Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000) suggest that in social networks, emotional support (the amount of love and caring, sympathy, understanding, esteem or value available from others), is most often provided by a confidante. In this study, befrienders seemed to provide such support through a reciprocal, confiding and safe relationship.

Psycho-social mechanisms: connectedness

As health problems increased and mobility declined, older adults in this study had become increasingly dependent on others to maintain initiative in social relationships. Fears of rejection appeared to be a significant barrier to initiating social contact, as Mrs D clearly describes:

I've never been one to go out and play bingo and everything like that. With being on your own so much in the house I think you do lose a bit of confidence … When you go somewhere like these social places, there's lots of little cliques – you feel a little bit out of it. (Mrs D)

Befriending therefore offered a relatively low-risk opportunity for regular two-way social conversation, helping interviewees feel emotionally connected to another person even in the absence of face-to-face contact (as with telephone befriending).

A number of interviewees acknowledged that self-preoccupation and rumination could result from long periods spent alone. The opportunity to get to know someone new could help to counter such tendencies. Mrs I, who lived in a small supported housing unit, said:

I think one of the great advantages is that someone from outside your own world comes and sits with you and tells you all about their world. It's so easy to get bored with life when you're old and all your activities are closing down and anything that makes you think about other people is very good for you. It makes you aware that the world isn't just yourself and your little room and your own dislikes and likes. (Mrs I)

This quote highlights how, in the midst of ‘closing down’ of social networks and activities, befriending offered interviewees the opportunity to expand horizons and gain new perspectives through befrienders relating their own life experiences and bringing news of changes in the local community. Mrs B, who very rarely left her house, said:

It gives you a little bit of boost when they're talking to you, telling you things about what's going on that you would be interested in … things you don't get out to see anymore … and she tells me what she's been doing. She goes out with the nurses you know, and they go out for a meal and she tells me about the meal and it makes me feel, you know, a little bit more connected to the world because otherwise you're sort of shut away in a box aren't you? (Mrs B)

This connection back to social life was often described by interviewees as keeping them ‘sharp’. Cognitive stimulation was facilitated through keeping up with befrienders' life events and relationships, discussing news and current events and, in some cases, reading, solving puzzles and playing games together. In bringing this ‘external focus’ to interviewees' lives, anticipation of visits was a critical part of the befriending experience.

Befriending therefore facilitated both a sense of belonging (emotional connectedness) and engagement in the wider social world (social connectedness). Although befriending represented a relatively limited addition to the structure of interviewees’ social networks, this should be viewed in the context of the restricted opportunities pre-existing networks provided for social contact. Mrs G summarised the views of many of the interviewees:

It's something to look forward to. It seems daft me saying that when I've got all this family but you see, I don't see them, do I? (Mrs G)

Drawing on Berkman and colleagues’ work, befriending in this study therefore provided both cognitive stimulation during and in anticipation of visits and, critically, helped to connect the individual back to their community so that they felt part of it once again.

Psycho-social mechanisms: maintaining positive self-concept

Loss can have a negative impact on self-concept and feelings of worth. Increasingly reliant on instrumental support, many interviewees worried about being ‘a burden’ and perceived themselves as a ‘problem’ to be solved by others.

I don't want to be taken over by other people, you know? (Mrs C)

In this context, befriending appeared to help some interviewees maintain a sense of autonomy and privacy. Befrienders' role was perceived in terms of ‘companionship’ not ‘help’, a role that allowed interviewees to exert an element of control over their social environment through choosing when and how to spend time with their befriender. This contrasts with other network members (such as adult children, carers and professionals), who usually determined the timing and purpose of interactions. With limited time available, these interactions were largely task-focused, as described by two of the gentleman interviewees:

My son comes every week without fail – does my shopping for me and gets whatever out of the bank … He will be ringing up today to get it tonight, and he will bring it the following day in his dinner hour. (Mr F)

Only that one carer who comes in and washes up. What can you do in quarter of an hour? You can't even speak to them. Gone! (Mr T)

Interviewees therefore clearly welcomed the opportunity to talk with befrienders at leisure about things other than their health problems or what shopping they needed.

As someone who had not witnessed their ‘decline’, befrienders facilitated interviewees’ efforts to maintain a more positive sense of ‘self’. This was achieved through narratives of past experiences, productive activities, roles and responsibilities that reinforced notions of autonomy and self-worth (e.g. contributions to the war, to work and raising children and grandchildren). Mrs A had been a busy homemaker and Mr L had flown fighter planes in the Second World War:

I mean with our S [daughter], I'm an old woman and you don't know nothing … When I'm with A [befriender] I don't talk like an old woman – we talk as normal (Mrs A)

He was quite interested in my job and what happened during the war, you know – I was in the RAF. He likes to hear about what happened in the past … I was born in 1921, just after the First World War, the ‘hungry twenties’, so I've got quite a tale to tell of the family. (Mr L)

Facilitating this sense of autonomy and positive self-concept may be of particular salience in a residential care environment. Depression and loneliness increase with age and disability, and are highest of all among older adults in care homes (Godfrey Reference Godfrey2005; McCormick et al. Reference McCormick, Clifton, Sachradja, Cherti and McDowell2009). Furthermore, it has been noted that staff in residential homes tend to conceptualise ‘independence’ very narrowly, in terms of individuals’ capacity to undertake basic self-care activities (e.g. bathing, dressing, feeding) and not in terms of retaining control and making decisions for themselves (Bland Reference Bland1999). It has recently been suggested that residential care and nursing homes should be opened up to befrienders, creating a network of advocates for older adults (Neuberger Reference Neuberger2008).

In this study, the seven interviewees living in residential or intermediate care all described feeling lonely despite being surrounded by other people all day. Staff were perceived as too busy to chat and tended to do things ‘to’ rather than spend time ‘with’ residents. Befriender visits gave purpose and shape to the residents’ days, broadening their perspectives on life. The visits also encouraged a sense of social inclusion, As Mrs N noted:

It's different answers and talk. Different things that you don't know … It's nice to think that somebody thinks about us at all. (Mrs N)

Berkman et al. suggest that ‘through opportunities for engagement, social networks define and reinforce meaningful social roles including parental, familial, occupational, and community roles, which in turn, provides a sense of value, belonging, and attachment’ (2000: 849). Our findings support this suggestion within the context of befriending for older adults, where befriending not only reinforced meaningful social roles but in particular reminded people of their achievements and, in a sense, reconnected them with their past selves.

Discussion

This empirical study has identified various mechanisms by which befriending may achieve emotional health benefits for isolated older adults. Using Berkman and colleagues' model, socio-cultural conditions include changes in social structure in society where the norms of informal support from family friends and neighbours are no longer applicable to many older adults in the UK and indeed in many other Western countries.

Increasingly research suggests that in older age, health benefits may be restricted to elective social relationships rather than those with family or care professionals (Golden, Conroy and Lawlor Reference Golden, Conroy and Lawlor2009; Mendes de Leon Reference Mendes de Leon2005). However, friendships are exactly the relationships most at risk as functional ability declines in older age (Godfrey Reference Godfrey2005). Indeed many of the interviewees in this study had at least one physical illness and several had multiple morbidities that had an impact on their daily activities and functional abilities. This study has shown how befriending can go some way toward compensating for the loss of elective relationships from social networks.

Befriending provided interviewees in the present study with much desired opportunities to develop social ties that they perceived as reciprocal, to share intimacies and establish trust – all of which are important attributes of ‘friendship’ (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003). However, careful ‘matching’ on the basis of shared interests or backgrounds may be less critical to successful befriending in older adults than previous literature suggests. Interviewees placed greatest value on a friendly disposition and good social skills. As bonds became established, commonalities (however tenuous) were identified with befrienders as confirmation of relationship success. This resonates in part with Carsten's work on cultures of relatedness (2000). Carsten argues that relatedness should be described in terms of indigenous statements and practices, some of which fall outside what anthropologists have conventionally understood as kinship. She suggests instead that relatedness is a fluid process that emerges over time and through, for example, the receiving and giving of food, an important element of befriending in this study, where cups of tea and a glass of wine were offered by befriendees to befrienders.

Our data confirm the importance of social support as highlighted in Berkman's theoretical model, but suggest this is largely concerned with emotional rather than with instrumental support. Befriending provided some interviewees with the opportunity to confide the emotional impact of loss on their lives in a ‘safe context’ and within an often reciprocal relationship without negative repercussions on the structure or functioning of other valued relationships (particularly with children). The importance of this perceived social support may be why anticipation of contacts with befrienders featured so prominently in the interviews.

This study adds to Berkman's model by suggesting the particular importance of the ‘social engagement’ aspect of befriending, which reconnects older adults back with their communities. Engagement with a befriender enabled interviewees to reinforce meaningful social roles (as parent, homemaker, worker, etc.) and reconnect with a past life that had often been significantly disrupted by loss. These mutually reinforcing psycho-social mechanisms may then impact on health through psychological pathways such as increased self-efficacy and self-esteem. The ways in which befriending may work are shown in an adaptation of Berkman and colleagues’ model in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Model linking befriending to health in older adults.

The study has a number of limitations. The majority of participating organisations were recruited through Age UK. However, as the largest provider of older adult befriending services, this may increase the transferability of the findings to other areas of the UK and to cultures where family support is declining. Interviewees were self-selected. We were unable to recruit subjects who had declined an offer of befriending but we did discuss past unsuccessful befriending relationships with interviewees, albeit not in great depth. We interviewed a limited sample of people in residential care (N=7) due to difficulties identifying befriending schemes operating in such settings. From discussions with care home staff and voluntary service managers it is clear that little provision currently exists in residential care despite the fact that befriending appears to be particularly valued in this environment. We interviewed a relatively small number of people who had used telephone befriending (N=4), and were unable to recruit any ethnic minority interviewees, although this reflects the individuals who used the services we evaluated.

In summary, emotional befriending may be one means of addressing loneliness and improving the psychological health of older adults. A sound theoretical basis increases the likelihood that interventions will be targeted and implemented appropriately (Medical Research Council 2000). Viewing our empirical data through the lens of Berkman and colleagues' theoretical model, this study has suggested features of befriending networks and key psycho-social mechanisms that may facilitate positive psychological outcomes. In particular, it appears that befriending offers some compensation for loss of elective relationships from older adults' social networks, providing opportunities for emotional support and reciprocal social exchange through development of safe, confiding relationships. Good conversational skills and empathy were the foundation of successful relationships within which commonalities were then sought. Befrienders broadened befriendees' perspectives on life (particularly among older adults in residential care). Social engagement was a powerful mechanism of action.

This study has raised a number of questions. The concepts of homogeneity and relatedness seem particularly relevant to befriender recruitment processes. There is a need to better understand the value of befriending in residential contexts and the relative cost-effectiveness of telephone versus face-to-face befriending.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank each of the Age UK and the other services that we worked with and all the older adults who gave up their time to talk with us.