Do international court judgments influence the behavior of all states subject to the court's jurisdiction, a phenomenon that legal scholars refer to as the erga omnes effect? This Latin phrase, meaning “flowing to all,” signals that the influence of a court decision extends beyond the litigants in a particular dispute. Formally, the judgments of international courts (ICs) are binding only inter partes.Footnote 1 They do not bind other states or the tribunal in future cases. This principle reflects national sovereignty concerns. By ratifying a treaty that creates an IC, a state accepts the court's jurisdiction and agrees to comply with specific judgments against it. But the state does not consent to be bound by rulings resulting from litigation in which it did not participate.

Nevertheless, many IC rulings have—or purport to have—erga omnes effects. For example, the European Court of Human Rights (the ECtHR or the Strasbourg Court) has asserted that it “determin[es] issues on public-policy grounds in the common interest, thereby … extending human rights jurisprudence throughout the community of [European] Convention States.”Footnote 2 The World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body has stated that “the legal interpretation embodied in adopted panel and Appellate Body reports becomes part and parcel of the acquis of the WTO dispute settlement system…. Absent cogent reasons, an adjudicatory body will resolve the same legal question in the same way in a subsequent case.”Footnote 3 A 2010 Council of Europe (CoE) report cites examples of governments that have changed laws and policies following ECtHR judgments against other countries.Footnote 4 Governments also invoke erga omnes to argue that they should be allowed to participate as third parties in IC proceedings.Footnote 5

Yet governments have also rejected attempts to broaden the influence of IC decisions. For example, the United States has argued that the “concept of erga omnes is squarely at odds with the fundamentally bilateral nature of WTO and GATT dispute settlement…. Adjudicators may not … enforce WTO obligations on behalf of non-parties to a dispute.”Footnote 6 Similarly, although the ECtHR has endorsed erga omnes since the 1970s, “it is not regarded by all States Parties as a legal requirement.”Footnote 7

The erga omnes effect of IC rulings is thus highly contested, both politically and legally. This should not be surprising. The erga omnes effect also implies a substantial delegation of sovereignty and a concomitant increase in the agency of international judges. Yet the political science literature has ignored this issue. Studies of IC compliance, for example, focus on a much narrower question: whether a particular state does what a court explicitly asks it to do.

We develop a theory that specifies the conditions under which IC judgments are likely to have an erga omnes effect. Our central claim is that IC judgments can help overcome domestic opposition to policy change under particular institutional and political circumstances. When national courts are authorized to apply international law to strike down domestic legislation, they can and sometimes do rely on the erga omnes effect of IC judgments to bring about change that was unlikely to materialize through political channels. Even in countries where governments are receptive to IC-inspired reforms, policy change may be blocked if political leaders face domestic opposition. IC judgments against other states can raise the salience of an issue and provide opportunities for legitimation or government “hand washing,” thus making policy change more likely. Moreover, IC judgments against one country may embolden international organizations (IOs) to demand policy change in all of its member states.

Our claims about the erga omnes effect are broadly consistent with a growing literature that attributes the influence of international law to domestic compliance constituencies that operate in specific political and institutional contexts.Footnote 8 Yet, our analysis goes beyond compliance to investigate whether ICs, like well-functioning domestic courts, influence the behavior of actors throughout a legal system.Footnote 9 We also examine the effects of lawmaking by international judges rather than by states via the negotiation and ratification of treaties. There is a growing literature on IC lawmaking,Footnote 10 but it has not considered the relationship to IC effectiveness. Moreover, because international judicial lawmaking does not involve commitments that states expressly accept, the theoretical mechanisms through which ICs gain domestic traction for their decisions are different than those for treaty commitments.

We evaluate our theory by analyzing ECtHR judgments on LGBT rights issues. The ECtHR has become increasingly progressive on LGBT issues. It has found violations of the European Convention against countries that criminalize consensual same-sex conduct, that impose a higher age of consent for gay men, that prohibit lesbians and gay men from serving in the military, and that restrict transsexuals' ability to change identity documents or to marry. For each of these issues, the court reversed one or more earlier decisions rejecting challenges to these policies. This pattern suggests a high degree of judicial discretion or agency.Footnote 11 Yet these shifts in ECtHR jurisprudence also track similar progressive trends in the national laws and policies of CoE member states. We thus examine whether ECtHR rulings themselves increase the likelihood of policy reforms in CoE countries, or whether the court merely follows preexisting legal and social trends.

We create a data set that identifies whether and when the policies of the forty-seven CoE member states follow ECtHR jurisprudence on five LGBT legal issues. The data set includes LGBT issues unaffected by ECtHR litigation to control for the confounding effect of other trends that increase LGBT rights protections. We find that an ECtHR judgment against one nation increases the likelihood that all CoE countries will adopt the same pro-LGBT policy. The annual probability that a state changes its policy is about fourteen percentage points higher when there is an ECtHR judgment. These findings are partially explained by CoE and European Union (EU) demands that nations seeking to join these IOs comply with some ECtHR rulings on LGBT issues. However, we also find that ECtHR judgments increase the likelihood of policy reforms for issues and countries not subject to membership conditionality.

Most notably, ECtHR rulings have the greatest marginal effect in countries where public acceptance of homosexuals is low. This finding is contrary to a prevailing critique of human rights treaties and of international laws and institutions more generally—that they matter most where they are needed least.Footnote 12 We find that the effect of ECtHR judgments on low-support countries is greatest where national courts can invoke the European Convention when reviewing domestic laws or where the executive is not supported by a religious, nationalistic, or rural party. Thus, the combination of an ECtHR ruling against another country with favorable domestic political or institutional conditions helps to overcome low public support for LGBT rights and increases the likelihood of policy change. This is consistent with the idea that the ECtHR follows a strategy of “majoritarian activism,” using the laws and policies of most member countries as a benchmark for developing international standards.Footnote 13

The Erga Omnes Effect of IC Judgments

ICs do not have the direct authority to implement their decisions, but they can influence the actors that do, such as domestic courts, executives, and IOs. For example, the behavior of executive branch officials may be constrained by interest groups that hold them accountable for implementing treaty obligations,Footnote 14 or because they fear damaging their reputation for compliance with international law vis-à-vis other states.Footnote 15 Other studies highlight the alliances that ICs forge with national judges or administrators whose interests are furthered by compliance with international rulings or who are persuaded to do so by an IC's interpretation of the law.Footnote 16

These insights do not, however, directly translate to the analysis of erga omnes effects because no legally binding commitments are at stake. To voters, interest groups, or other states that care about compliance with international law, executives can respond that the government has no obligation to follow IC judgments against other nations. In the absence of a formal compliance obligation, domestic courts and administrators are not forced into action and may even have incentives for inaction to avoid charges of overreaching.

Nevertheless, we argue that there are three mechanisms by which judgments can influence compliance constituencies in states not a party to IC proceedings—the threat of future litigation, the persuasive authority of judicial reasoning, and the agenda-setting effect of IC decisions. As we detail later, a number of domestic and international conditions make it more or less likely that these mechanisms, either individually or in combination, have sufficient force to overcome domestic opposition to IC-inspired policy reforms.

Three Mechanisms of IC Influence on Nonparties

Preempting future IC litigation

Although ICs lack a formal stare decisis principle, they generally follow their own rulings.Footnote 17 Repeat litigation of the same legal issue generally leads to the same outcome even if it involves a different state. Anticipating this result, national governments or courts may change their behavior to preempt future IC review. For example, Canada abandoned its “zeroing” dumping policy with explicit reference to earlier WTO decisions against the EU and the United States;Footnote 18 high courts in Argentina and Colombia struck down amnesty laws based on judgments of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights invalidating amnesties in Peru;Footnote 19 and the German Federal Constitutional Court deferred to the International Court of Justice (ICJ's) interpretation of a treaty that Germany had ratified, although the country was not a party to the case.Footnote 20 The prospect of an IC ruling may also empower IOs to demand policy change. As we detail later, the EU Commission relied heavily on ECtHR rulings to identify the human rights conditions for EU membership, partially because it asserted that the ECtHR would invalidate restrictive laws in candidate countries.Footnote 21

Persuasive authority

An IC's reasoned determination that a law or policy is illegal can influence the behavior of compliance constituencies in other jurisdictions with similar laws or policies. For example, the legal analysis adopted by IC judges may help build alliances between international and national judges that persuade national judges to strike down treaty-inconsistent domestic policies.Footnote 22 That this mechanism of influence is divorced from the threat of future international litigation is suggested by the citation of IC judgments in countries beyond the court's authority. For example, ECtHR judgments on LGBT rights have been favorably cited by courts as far away as Hong Kong, India, South Africa, and the United States.Footnote 23 Persuasive authority need not be tied to legal reasoning: citizens and elites can be swayed by the fact that a policy is illegal if that information comes from an impartial source perceived to have expertise. Survey experiments have also found that both elites and publics are more likely to oppose policies when they are informed that these policies violate international law, even if no issue of noncompliance is raised.Footnote 24

Agenda setting

An IC judgment may raise awareness and thus increase the likelihood that an issue will appear on the agenda of national parliaments or executives. Simmons makes this argument with respect to treaties:

It is one thing not to initiate policy change on the national level and quite another not to respond once a particular right is made salient through international negotiations. Silence is ambiguous in the absence of a particular proposal, but it can easily be interpreted as opposition in the presence of a specific accord.Footnote 25

The concrete and fact-specific context of IC rulings can increase political salience in a similar fashion. For example, following an ECtHR ruling against the United Kingdom (UK's) blanket ban on prisoner voting, the Irish Parliament quickly adopted legislation to allow prisoners to vote by mail. The issue had not previously been on the agenda; lawmakers indicated that the reform was motivated by the ECtHR's judgment even as they stressed that Irish suffrage laws would have survived a challenge in Strasbourg.Footnote 26 Similarly, civil society groups, judges, and supportive legislators capitalized on the attention generated by the Inter-American Court's jurisprudence on amnesty laws to pursue bolder human rights policies in Latin America.Footnote 27

These three mechanisms may work separately or in tandem. For example, even if an IC's reasoning fails to persuade interest groups, national judges may revisit their case law to preempt future international litigation.Footnote 28 Similarly, lawmakers sympathetic to reforms may have refrained from acting until an IC catapults the issue to the top of the legislative agenda.

Even when these mechanisms operate together, however, there is no guarantee that IC rulings will influence state behavior. In some countries, for example, the influence of compliance constituencies may be too weak to overcome local resistance to change. Three conditions should make it more likely that the three mechanisms of IC influence causally contribute to policy change. We use these conditions to develop more precise hypotheses about the operation of the erga omnes effect.

First, the erga omnes effect is more likely when national courts can review allegations that domestic policies violate international law and when treaties are deeply embedded in national legal systems.Footnote 29 If treaties have a status equal or superior to domestic constitutions or statutes, national judges should be more likely to defer to IC interpretations of those instruments. For example, the Constitutional Court of Croatia accepts the “binding interpretive authority” of all ECtHR judgments due to the “quasi-constitutional status of the Convention in the Croatian legal order.”Footnote 30 In contrast, if national courts cannot invoke international law to review domestic policies, then judges' aversion to being reviewed internationally and the persuasive power of IC interpretations should have a less pronounced influence on policy change.

Even in countries whose courts have strong review powers, domestic actors may prefer to effect policy change through the legislature. Yet, if such change is unlikely—for example because it is politically unpopular—litigants may turn to national courts, citing IC decisions in an attempt to persuade judges to align domestic policies with international standards. This suggests that the marginal effect of IC decisions is greatest where domestic political support for policy change is low but domestic legal institutions are receptive to the influence of international law.

Second, the erga omnes effect may depend on the government in power when an IC issues its judgment. An IC decision provides a signal about the legality of a policy in force in multiple countries.Footnote 31 Such a signal may tip the balance in favor of reform if voters care about adherence to international law but were unaware or uncertain that the policy violates its dictates. On the other hand, voters with strong predispositions are not easily persuaded by new information.Footnote 32 For example, in contrast to Ireland, where prisoner voting reform sailed through parliament, the issue became hugely controversial in the UK. In opinion polls taken following the judgment, 80 percent of British Conservatives, the main party in government, opposed giving prisoners the right to vote.Footnote 33 While the IC ruling had an agenda-setting effect and the parliament voted on it, the proposal was rejected in the face of this opposition.

We expect IC rulings to have the largest impact where the government in power is at least not actively opposed to reform. This is not a circular argument. For example, religious parties tend to be much more strongly opposed to LGBT rights than are liberal or left-wing parties. Yet, liberal or left parties do not always push for LGBT legal reforms, especially in countries where public acceptance is low. If these parties are in power, the increased issue salience and declaration of illegality that results from an IC ruling may tip the balance in favor of reforms. We thus expect the marginal effect of such rulings to be strongest in countries that are otherwise unlikely to adopt reforms, for example, because of low public support, but where the composition of the government is relatively favorable to policy change. In such circumstances, governments can point to IC judgments to justify their actions as consistent with international law.

Third, we expect the erga omnes effect to be larger when IOs can leverage IC judgments. Such influence is strongest when IOs impose conditions on membership.Footnote 34 IOs often seek to justify such conditions, however, and IC rulings may serve that purpose. For example, an IO can motivate policy change by arguing that in future litigation an IC would find a country in breach of international law. Judicial interpretations may also persuade IO officials that a policy is illegal and thus incompatible with membership. As we illustrate with LGBT rights, this may lead the organization to demand reforms of policies that an IC has adjudicated but not for similar policies that it has not (or not yet) reviewed.

The ECtHR and LGBT Rights in Europe

An empirical investigation of the erga omnes effect is highly demanding. It requires analyzing the legal principles in IC judgments and coding whether the policies in all states subject to a court's jurisdiction adhere to those principles in multiple years. To overcome these challenges, our study chooses depth over breadth. We limit our analysis to a single court—the ECtHRFootnote 35 —and a single issue area—LGBT rights. Within these constraints, however, we focus on multiple judgments and several subissues.

Case Selection

We selected the ECtHR for several reasons. It is the most active IC and it exercises authority over forty-seven countries that vary in the domestic institutions of theoretical interest. In addition, although the ECtHR asserts that its judgments have erga omnes effects, the extent to which its decisions actually influence government policies is uncertain.

We chose LGBT rights on a number of grounds. Challenges to restrictions on those rights in Strasbourg have occurred for more than half a century. Yet the court's response to these challenges has evolved markedly over time, highlighting the agency of ECtHR judges. LGBT rights also feature prominently in legal and social science debates about court-led social change and political backlashes against judges.Footnote 36

This last issue is especially noteworthy. The development of ECtHR case law has been influenced by progressive shifts in European laws and social policies regarding sexual minorities. Yet these changes are by no means universal. Some governments and publics remain skeptical of or openly hostile to LGBT rights. A 2007 Gallup Poll survey of acceptance of gays and lesbians in 117 countries ranked CoE member states at the top (The Netherlands, with 83 percent acceptance) and the bottom (Azerbaijan, with 2 percent acceptance) with other countries spread out along a continuum.Footnote 37 Moreover, several Eastern European nations are now considering proposals to recriminalize homosexual conduct or outlaw favorable public portrayals of gay men and lesbians.Footnote 38 These divergent attitudes provide variation to examine the erga omnes effect on states whose policies have not (or not yet) been challenged in Strasbourg, including countries actively opposed to reforms that the ECtHR has endorsed.

These two attributes—judicial recognition of progressive legal and social trends together with resistance by some governments—characterize many European human rights cases. Prisoner voting is a prominent recent example. But there are many other instances in which the ECtHR has expanded human rights “to ensure that the interpretation of the Convention reflects societal changes and remains in line with present-day conditions.”Footnote 39 Combating discrimination against Roma communities, blocking deportations of suspected terrorists, and bolstering the due process rights of criminal defendants are other examples where the court has found fault with countries whose policies are less progressive than those of their neighbors, sometimes generating negative responses from governments.

The Evolution of Strasbourg Case Law and National Policies on LGBT Rights

Table 1 illustrates the evolution of Strasbourg case law for several lesbian and gay legal issues. Table 2 reveals a similar trend for transsexual rights, including change of sex on identity documents and the right to marry. For each legal issue, the date of the first violation appears in bold text.

TABLE 1. Key ECtHR judgments and European Commission decisions on lesbian and gay legal issues

Note: For each legal issue, the date of the first violation appears in bold.

TABLE 2. Key ECtHR judgments and European Commission decisions on transsexual legal issues

Note: For each legal issue, the date of the first violation appears in bold.

Tables 1 and 2 reveal four noteworthy patterns. First, the ECtHR and European Commission have become more receptive over time to a broader range of LGBT rights. Second, the European tribunals have proceeded in small steps, each of which is a modest advance on cases decided several years earlier. Third, after initially finding a violation, the ECtHR does not backtrack when it later reviews challenges to the same or similar policies in other countries,Footnote 40 even those claiming to be more conservative than CoE members.Footnote 41 Fourth, LGBT rights litigation has focused on a few countries, mainly Austria, Germany, and the UK. Taken together, these patterns enable us to measure erga omnes effects by examining whether governments modify their policies after the ECtHR has ruled against another country.

This analysis is complicated, however, by the fact that the evolution of Strasbourg case law parallels a similar liberalizing trend across Europe. This trend is predominantly a legislative process, and it occurs in the following order: decriminalization, establishing an equal age of consent, enacting antidiscrimination laws, recognition of same-sex relationships via registered partnerships and later same-sex marriage, and finally, parenting.Footnote 42

These national-level trends powerfully influence ECtHR judges. Several judgments listed in Table 1 and Table 2 expressly refer to the existence of regional trends on LGBT rights, trends that scholars have described as a “European consensus.”Footnote 43 In Dudgeon v. United Kingdom, for example, the court stated that it could “not overlook” the decriminalization and “increased tolerance of homosexual behavior … in the great majority of the member-states of the Council of Europe.”Footnote 44 Aware of the importance that the ECtHR attaches to European consensus, advocacy groups often submit amicus briefs that document legal and social trends. This is illustrated by Goodwin v. United Kingdom, where the Strasbourg Court relied heavily on an nongovernmental organization (NGO) study that identified, on a country-by-country basis, whether transsexual persons could change their sex on identity documents.Footnote 45 The fact that the court considers these trends might mean that its judgments influence policy reforms in lagging states. Nevertheless, it complicates causal inference, an issue we address at length in the empirical sections.

The Effect of ECtHR Judgments on National LGBT Rights Policies

Judicial review

First, ECtHR rulings against one nation can influence policy changes across Europe via judicial review. For example, when the Hungarian (2002) and the Portuguese Constitutional Courts (2005) declared unconstitutional the unequal age-of-consent laws in those countries, they relied heavily on the Sutherland decision finding that the UK's age-of-consent statute contravened the European Convention.Footnote 46 In 2007, the Irish Supreme Court overturned national laws that prohibited changing a birth certificate following sex reassignment, relying on the ECtHR's decision in Goodwin v. United Kingdom.Footnote 47

The cases from Hungary, Ireland, and Portugal also suggest a more nuanced point—that ECtHR judgments may be especially influential where public acceptance of LGBT individuals is relatively low but where domestic courts can rely on ECtHR precedents when reviewing national policies. In the 1999 European Values Study, for example, Hungary ranked last among thirty-five CoE countries in public acceptance of homosexuals. The same study identifies Portugal and Ireland as in general the least tolerant nations in Western Europe.Footnote 48 Yet in Hungary (since 1993), Ireland (since 2004), and Portugal (since 1978), domestic courts can review legislation based on its compatibility with the European Convention.Footnote 49 This leads us to hypothesize that ECtHR judgments increase the probability of policy change in countries where public support for such change is low and where domestic courts can rely on the convention and Strasbourg case law when exercising judicial review.

Legislative change

The most important factor facilitating legislative change is the partisan composition of governments. The literature suggests that opposition to LGBT rights is greatest among religious, rural, and nationalist voters.Footnote 50 Governments composed of parties supported by these voters should be less susceptible to the agenda-setting effect of ECtHR judgments favoring LGBT rights. Conversely, the marginal effect of judgments should be greatest in countries where public acceptance of LGBT individuals is relatively low but where the executive is not from a party that relies on rural, religious, or nationalist constituencies.

A telling illustration is the 1999 Lustig-Prean judgment against the UK for banning gay men and lesbians from serving openly in the military. LGBT activists and progressive political parties argued that similar bans in other CoE countries violated the European Convention. In Germany, Winfried Stecher, a lieutenant dismissed after admitting his homosexuality at a public hearing, filed a court challenge to that country's “glass ceiling” policy that denied officer positions to gay men and lesbians.Footnote 51 Defense Minister and Social Democrat (SPD) Rudolf Scharping vowed to fight the case, declaring homosexuals “unfit for leadership” in a leaked letter to fellow cabinet members.Footnote 52 The coalition government (SPD and Green Party) initially backed Scharping, and German courts rejected Stecher's legal challenge.

However, the liberal opposition party (FDP) demanded a debate on the topic in the Bundestag. The FDP's spokesperson, Hildebrecht Braun, invoked the Strasbourg precedent explicitly: “The European Court has already decided that the discrimination of homosexual soldiers is a violation of human rights. Even though the judgment concerned a British soldier, it is clear that it applies directly to the German army.”Footnote 53 Spokespersons for the two governing parties made similar arguments. Defense Minister Scharping initially argued that the British and German exclusionary policies were different,Footnote 54 but he soon announced his intention to reinstate Stecher and revisit the army's exclusionary policy.Footnote 55

Attitudes about gay men and lesbians are relatively progressive in Germany; reforms might therefore have occurred without the ECtHR judgment. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the SPD government initially favored retaining the restrictions but quickly changed course when confronted with the ECtHR precedent. In contrast, the Christian CDU party—which had been in federal government between 1983 and 1998 and had “been a barrier to most of the legislation desired by the gay and lesbian movement”Footnote 56 —might have offered stronger resistance had it been in power. The fact that exclusionary policies remain in force in several countries with more conservative executives and ruling political parties, such as Poland, Romania, and Portugal, supports this conjecture, although those parties are more conservative on this issue than the CDU.

Membership conditionality

IO membership conditionality should strengthen the erga omnes effect of rulings. In 1993, the CoE identified LGBT-related commitments for accession countries that were shaped by ECtHR jurisprudence.Footnote 57 For example, the report on Romania's application for membership stated:

The Rapporteur notes with concern that under Article 200 of the Romanian Criminal Code, homosexual acts conducted in private between consenting adults remain a criminal offence. A number of persons are currently serving prison sentences after having been convicted of this offence. The Rapporteur would draw attention to the fact that the European Court of Human Rights has consistently held that such a prohibition, even in the absence of actual prosecution, violates Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights…. The Court would thus a fortiori come to a similar finding where people have actually been convicted, as in Romania.Footnote 58

The EU accession story is similar. Since LGBT rights were not at the time explicitly part of EU law, the European Commission relied heavily on Strasbourg case law. As Kochenov explains: “in practice, the ECtHR served as a gay rights standard provider in the course of the pre-accession exercise.”Footnote 59 Like the CoE, the EU focused on decriminalization, adding equal ages of consent for same- and opposite-sex sexual conduct in line with the 1996 Sutherland decision.

However, the extent to which EU conditionality in fact influenced policy change is unclear. Bulgaria revised its penal code within a year after being criticized by the EU Commission, and Estonia amended its code before the commission had the opportunity to demand change. In contrast, Hungary refused to alter its laws, leading to the Constitutional Court ruling previously discussed.

Taken together, these examples lead us to hypothesize that CoE and EU conditionality made it more likely that accession countries with low levels of public support for LGBT rights would change their policies. We acknowledge, however, that membership conditionality is relatively specific to Europe. Thus, if conditionality completely explained the erga omnes effects of ECtHR judgments, it would call into question the generalizability of our findings.

Do ECtHR Judgments Influence National Laws and Practices?

We gathered data on whether and in what year the policies of CoE countries conformed to ECtHR precedents on LGBT rights. Coding a state as “no” for a given legal issue implies that the court would find that state in violation of the European Convention were its practices challenged after the initial judgment establishing the relevant legal principle. To make this assessment, we collected data from multiple surveys as well as reports by IOs, NGOs, and secondary sources.Footnote 60 We also searched primary documents and consulted national experts on LGBT legal issues. We discuss specific coding rules as we introduce each issue.Footnote 61

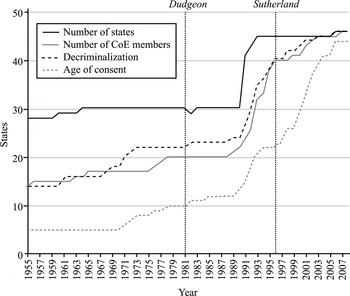

Figure 1 shows the number of countries that, between 1955 and 2008, decriminalized homosexual conduct and equalized the age of consent. Coding criminal law issues involves relatively straightforward assessments of whether an existing statute violates the convention as interpreted by the Strasbourg Court.Footnote 62 Figure 1 also identifies the ECtHR and European Commission decisions that established the key legal principle for each issue. As Table 1 shows, the Dudgeon judgment (1981) first found that criminalizing consensual homosexual conduct violated the convention, and the Sutherland decision (1996) reached the same conclusion for laws that establish unequal ages of consent.

FIGURE 1. Decriminalization and age-of-consent policies

Note: “Number of states” includes all independent European nations with information on criminalization policies. “Decriminalization” is the subset of those states that decriminalized consensual homosexual conduct. “Number of CoE states” includes the subset of “number of states” that were CoE members at any time. “Age of consent” is the subset of ”numer of states” that equalized the ages of consent for same-sex and opposite sex sexual conduct. The legends for Figures 2 and 3 area analogous.

The visual evidence in Figure 1 indicates that when the Sutherland case was decided in 1996, only about half of the CoE's member states had adopted an equal age of consent. This reveals that the European consensus that the ECtHR often cites as a justification for finding a violation of the convention need not be a supermajority of states. It also illustrates that Strasbourg jurists have considerable discretion to decide when to recognize evolving regional trends.

Figure 1 also provides some support for the Sutherland decision as the trigger for an erga omnes effect for equal age-of-consent laws, although the adoption of such laws predated the decision. The impact of the Dudgeon case is more difficult to evaluate, given that most CoE member states had decriminalized by the time the judgment was issued. Nevertheless, Dudgeon could have had an influence through the mechanism of conditionality. The overall pattern in decriminalization in the 1990s closely tracks patterns in CoE membership and is consistent with the hypothesis that countries adopted laws one or two years before they joined the organization. Conditionality did not apply to unequal age-of-consent laws, which had not yet been found to violate the convention. As a result, many countries decriminalized homosexual conduct without equalizing the age of consent. Between 1989 and 1995 sixteen states decriminalized, but only three of them adopted equal age-of-consent laws. This gap closed rapidly after the 1996 Sutherland decision. These patterns suggest, although they do not prove, that ECtHR judgments shaped the timing of policy changes.

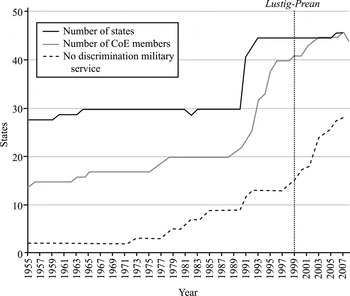

Figure 2 shows the number of states that permit lesbians and gay men to serve openly in the armed services. The total number of countries is somewhat smaller because we excluded states that do not have militaries. Discriminatory practices relating to the military are somewhat more difficult to code than criminal law issues because in some countries express discriminatory policies do not exist but discriminatory practices are pervasive. In the absence of an official policy, we required evidence of a systematic pattern of conduct, not merely a small number of isolated incidents. We also coded as discriminatory those states that classified homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder, which is a ground for dismissal, harassment, or discrimination. The appendix contains all coding decisions and sources.

FIGURE 2. Discrimination in armed services

At the time of the key ECtHR judgment in 1999, less than half the member states had nondiscriminatory policies. The visual evidence is suggestive of a relationship between the ECtHR judgment and policy change. Between 1991 and 1998, not a single country abandoned its discriminatory policies or practices. During the decade following the Lustig-Prean & Beckett judgment, sixteen countries did so.

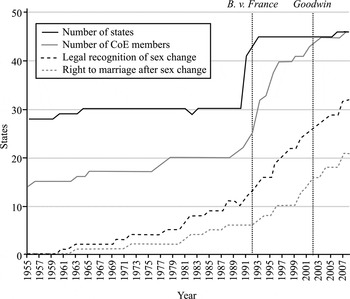

Recognition of transsexual rights is more difficult to code because it requires judgments about the broader context in which laws operate. Figure 3 plots the trends in policy adoption for two transsexual legal issues: the right to change identity documents following sex reassignment surgery (first recognized in B. v. France (1992)) and the right to marry (first recognized in Goodwin v. United Kingdom (2002)). The relationship between these two issues varies. In some states, the right to change one's sex on a birth certificate automatically implies a right to marry. In other countries, this is not necessarily so, either because sex at birth is kept in a different registry that is authoritative for marriage or because birth certificates cannot be altered even if other identity documents can.

FIGURE 3. Transsexual issues

For example, the UK had long allowed transsexuals to change their sex on driver's licenses, passports, and other official documents, thereby complying with the 1992 judgment. However, in 2002 the ECtHR found that the UK's failure to revise the birth registry and to allow transsexuals to marry constituted a violation of the convention—a claim the court had previously rejected. In other countries, such as France, complying with the 1992 decision had the effect of guaranteeing a right to marry. This partly explains the parallel trends in the adoption of these policies.

Figure 3 provides additional evidence that a European consensus can be a bare majority of CoE member states. The visual evidence of the erga omnes effect, however, is inconclusive: while many countries adopt policies to recognize sex changes after the 1992 decision, a similar trend preceded that judgment.

Taken together, the evidence relating to these LGBT legal issues reveals that the ECtHR's adoption of a legal principle does not result in rapid and widespread repeal of policies that conflict with that principle. Yet the evidence suggests that ECtHR judgments may affect the adoption of LGBT reforms in a probabilistic manner. Figure 4 provides support for this. It plots the temporal effects of ECtHR judgments based on a regression model whose dependent variable is the number of states that have adopted each of five LGBT legal issues in any given year. The model includes fixed effects for each issue and dummies for each year.Footnote 63 To control for overall trends in liberalization, the model also includes an index of how many countries had adopted pro-LGBT rights policies that were unaffected by ECtHR decisions.Footnote 64 Finally, the model controls for the number of states. The effect of an ECtHR judgment is measured by a quadratic time counter from the year that the court finds a violation for a specific legal issue. Figure 4 shows that countries do not immediately adopt reforms following an ECtHR judgment. Rather, the estimates suggest that, on average, an ECtHR ruling is responsible for an additional five countries shifting policies in the five years immediately following the ruling, and eight countries over a ten-year period.

FIGURE 4. Effects of ECtHR judgments over time

These are substantively important effects, although they also confirm that the policies of some CoE countries remain at odds with ECtHR decisions even after a decade. The aggregate analysis in Figure 4 obscures two key issues. First, it does not allow us to separate the effect of ECtHR judgments on countries whose policies the court actually reviewed and countries whose policies were not (or not yet) challenged in Strasbourg. Second, the aggregate analysis does not allow us to evaluate our conditional hypotheses.

Regression Analysis

Our unit of analysis is the country (i)-year (t)-issue (j). The dependent variable LGBT ijt denotes the policy or practice that country i has in place on issue j in year t, where LGBT ijt = 1 if the policy favors LGBT rights, and 0 otherwise. The primary independent variable ECtHR jit takes the value 1 if the court has ruled that not having policy j is a violation of the European Convention at time t and if country i has ratified the convention, and 0 otherwise.

We are specifically interested in the effect of ECtHR judgments on countries for which the court did not explicitly find a violation. We therefore include ECtHRCountry tji , which takes the value 1 from the date the court explicitly rules that a particular country's policies on a given issue violate the convention. For decriminalization, for example, this variable takes the value 1 for the UK in 1981 (Dudgeon), for Ireland in 1988 (Norris), and for Cyprus in 1993 (Modinos) (see Table 1). If ECtHR rulings matter only in the narrow sense that they influence the behavior of countries against which the court has found a violation, then we would expect this variable to exert a significant effect rather than ECtHR jit .

The biggest challenge to causal inference is that both the propensity of ECtHR judges to find violations and the propensity of countries to adopt reforms may be motivated by the same changing norms and practices. The model may thus inaccurately attribute policy changes to ECtHR judgments that are in fact the result of norms and practices that are changing for other reasons. We address this potential bias in two ways.

First, we create an index LGBTOther i,t for the presence of LGBT rights that are unaffected by ECtHR review, inasmuch as the court has not (or had not at the relevant time period) found a violation concerning these rights. The index consists of five legal issues that are part of the “standard sequence”Footnote 65 of progressive LGBT policy reforms: antigay hate speech laws, recognition of same-sex cohabitation, registered partnership, second parent adoption, and same-sex marriage. This index reflects broader European trends that are not influenced by ECtHR judgments. The bivariate correlation between the LGBT policies influenced and not influenced by ECtHR judgments is high.Footnote 66

Second, we explicitly model the ECtHR's decision-making process. Given that a case on issue j in year t comes before the court,Footnote 67 the ECtHR finds a violation if a majority of its judges vote in favor of doing so.Footnote 68 If policy changes respond to social trends rather than court rulings, then it shouldn't make much of a difference whether 49 or 51 percent of judges believe that a practice violates the convention. This makes the proportion of judges that favor a finding of a violation an ideal confounding variable: if the court's finding (or nonfinding) has a causal effect, then a dummy variable for the presence of a ruling should be positive and significant even after controlling for the vote proportion.Footnote 69

Unfortunately, we observe only forty-two votes on our five legal issues. Our strategy is therefore to estimate the missing vote proportions (V jt ). We use the previously mentioned policy index, issue dummies, and the average degree of judicial activism.Footnote 70 The latter variable captures that the composition of the ECtHR has changed over the years, with more restrained judges being replaced by more progressive ones.Footnote 71 The three variables are significant predictors of observed vote proportions and the model fits the data well, thus confirming that the ECtHR changes its precedent both due to changing state practices but also because its composition has changed.Footnote 72 Based on the coefficients, we interpolate the missing values to estimate the predicted vote proportion PredVot j,t .

To examine whether IO conditionality affects policy change, we coded a variable that takes the value 1 if a country in a given year and for a specific legal issue is under the scrutiny of the Council of Europe and/or the EU, and 0 otherwise. This situation applies to states seeking membership after 1989 for the CoE on the decriminalization issue, after 1996 for the CoE on the age-of-consent issue, after 1998 for the EU on both criminal issues, and after 2000 for the EU on the military issue. We also include indicator variables for CoE and EU membership.

To investigate the influence of the ECtHR via domestic litigation, we identified whether national courts possess the authority to review whether laws and policies violate civil and political rights (pursuant to a constitution, ordinary legislation, or the European Convention itself), and whether the convention has been incorporated into the domestic legal order (automatically or following the adoption of implementing legislation). For each country-year, we coded a dummy variable as 1 where both judicial review and incorporation existed, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 73 By 1990, 40 percent of countries in our sample satisfied these criteria. By 2000, this had risen to 80 percent.

To measure executive opposition to LGBT rights across countries and years, we coded a variable that takes the value 1 if the party that controls the executive is coded as religious, rural, or nationalist in the Database of Political Institutions.Footnote 74

We measure public acceptance of homosexuality using a question from European Values Studies (EVS) in 1981, 1990, 1999, and 2008 that asked whether homosexuality is “justified” on a ten-point scale.Footnote 75 Although there were substantial temporal shifts toward more acceptance, the cross-sectional differences among the average scores for citizens were remarkably consistent. The bivariate correlation for the thirty-five countries included in 1999 and 2008 is .94 (.90 between 1990 and 2008). We linearly interpolated the missing years. The measure has external validity in that it correlates highly with other cross-national surveys that lack the temporal and/or geographic coverage of the EVS surveys.Footnote 76

We estimate a logit model with fixed effects for countries and issues.Footnote 77 The country fixed effects capture difficult-to-observe cultural reasons why some countries may be more likely than others to adopt LGBT-friendly policies.Footnote 78 The issue fixed effects capture what appears to be a standard sequence of LGBT policy reforms.Footnote 79 An additional issue is how to model time dependence across observations. Once a state enacts a progressive policy, it almost always remains in place.Footnote 80 ECtHR rulings should prevent or at least decrease the likelihood of backtracking. However, given the rarity of backtracking and the problems of temporal dependence, we exclude observations from the data after the last adoption of the LGBT-friendly policy (although our substantive results do not depend on this).

We thus estimate the annual probability that an ECtHR ruling will lead a country that has not yet adopted a pro-LGBT policy to do so. This is identical to a hazard model where the fixed country and issue effects acknowledge that each country and issue has its own base-line hazard rate. As before, we also include PredVot j,t to model issue-specific trends that may make a court ruling more likely. Results are substantively identical when we use the country-specific index of LGBT rights policies unaffected by the ECtHR as the main confounding variable. The model also includes a linear time trend and time-varying country-specific covariates X it that have been found important in the literature. In addition, we include real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as a measure for economic developmentFootnote 81 because LGBT rights often receive wider support as a country becomes more developed economically.Footnote 82

EU membership may also be a confounding influence. In 2000, the EU adopted a directive mandating nondiscrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment.Footnote 83 Although the directive did not expressly apply to the armed forces, it may still influence country policies on whether LGBT individuals may serve openly in the military. We thus create a dummy variable that takes the value 1 for EU members on the military issue starting in 2000.

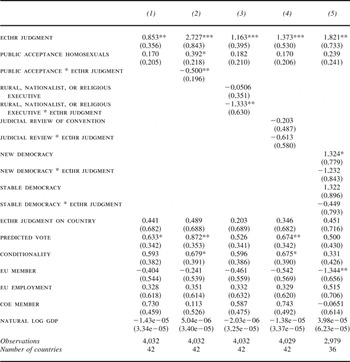

Table 3 presents the results with the alternative LGBT rights policy index as the main control variable and Table 4 shows the predicted vote share. The two variables are highly correlated (R = .8). Introducing both of them in the same model renders each insignificant but does not affect our core findings. Indeed the findings are consistent across both tables. Most importantly, there is a positive and significant probabilistic effect of ECtHR judgments on national LGBT policy reforms in all specifications. All else equal and despite our best efforts to control for other influences, an ECtHR judgment increases the probability of policy change by about fourteen percentage points in any given year (based on Model 1 in Table 4). There is an additional eleven percentage point impact on the country against whom the violation is found, but this effect is not statistically significant (perhaps because these cases are rare).

TABLE 3. Fixed effect logit estimation of decision to adopt progressive LGBT policies

Notes: Fixed effects for countries and issues, and year trends omitted. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < .01,

** p < .05,

* p < .1.

TABLE 4. Fixed effect logit estimation of decision to adopt progressive LGBT policies

Notes: Fixed effects for countries and issues, and year trends omitted. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < .01,

** p < .05,

* p < .1.

Models 2 to 4 in Tables 3 and 4 examine the various conditional hypotheses. Model 2 shows that public acceptance of homosexuals has a positive effect on the likelihood of policy change. Yet, as we hypothesized, the marginal effect of an ECtHR ruling is greater in countries where public acceptance is relatively low. This suggest that the ECtHR reduces policy differences among European countries with different levels of public support for LGBT rights by inducing more conservative states to adopt policy reforms that they would otherwise have avoided or delayed. The other factors in our model, such as the country fixed effects and LGBT issues not affected by the ECtHR, account for much of the variation in policy adoption, but countries where public acceptance is low look more progressive than otherwise expected once the ECtHR has intervened, even if its ruling pertains to another country.

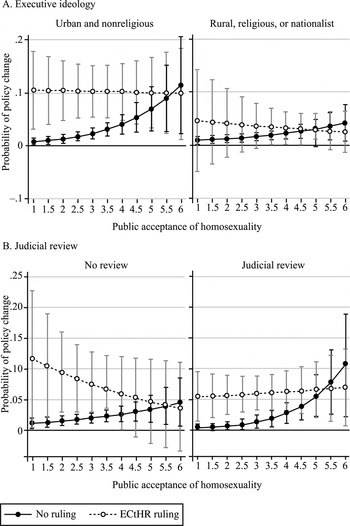

Model 3 suggests that the marginal effect of ECtHR judgments is lower when a rural, nationalist, or religious government is in power. Yet our theory also hypothesized a three-way interaction: that the marginal effects of ECtHR judgments should be particularly high when public support for homosexuals is low and there is no rural, nationalist, or religious executive in power. Figure 5A illustrates the core findings when such an interaction is added to Model 3. To evaluate the figure, it is useful to know that the mean value for public support in the sample is 2.8 with a standard deviation of 1.28.Footnote 84 The figure indicates point estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals that allow us to assess significance. The result strongly indicates that only when the executive is not rural, nationalist, or religious does an ECtHR judgment exert a significant and positive effect on policy change. This is especially true when there is less public acceptance of homosexuality, although it holds along almost the entire acceptance spectrum (for example, Germany's level in 1999 was around 5).Footnote 85 In countries with low levels of acceptance that do not have a religious, rural, or nationalist executive in power, the probability of policy change increases by more than ten percentage points following an ECtHR judgment. The corollary is that ECtHR judgments have no impact in countries with low levels of public acceptance and an executive supported by religious, nationalist, or rural parties. This illustrates the political and institutional limits of the erga omnes effect.

FIGURE 5. The effect of ECtHR judgments at different levels of public acceptance of homosexuals and different institutional and political conditions

Note: Predictive margins with 95 percent confidence intervals.

Model 4 shows that countries in which national courts can strike down domestic legislation based on the European Convention are not more likely to change policies, even after ECtHR rulings. However, Figure 5B shows the results of a three-way interaction with public support: countries with low levels of public acceptance but judicial review are significantly more likely to change policy when there is an ECtHR judgment than when such a judgment does not exist. Indeed, following an ECtHR judgment, low public acceptance countries are equally as likely to change their policies as high public acceptance countries.

Taken together, Figures 5A and 5B provide evidence that the marginal effect of ECtHR rulings is greatest when public acceptance is relatively low but when political and institutional conditions are favorable for policy change. States with high public acceptance are likely to shift voluntarily when other countries adopt reforms (a trend captured by our control variables). But in low-acceptance states with favorable conditions, ECtHR rulings make a noticeable difference.

Our third variable of theoretical interest—membership conditionality—has the hypothesized positive effect on policy change, although it is not statistically significant in all specifications. When either the CoE or EU is monitoring an applicant state's compliance with ECtHR decisions on LGBT rights, the annual probability of policy change increases by 14 percent. We find no major differences between EU and CoE conditionality. More importantly for our study, ECtHR judgments have a statistically significant effect for countries not under membership conditionality. However, the interaction between membership conditionality and public support was not significant (not shown). This may be because there was very little variation among accession countries: almost all these countries had relatively low levels of public support for homosexuals.

Model 5 shows that there is no evidence for an alternative hypothesis prevalent in the literature: that new democracies are more responsive to international legal obligations.Footnote 86 Democratizing countries have strong incentives to delegate sovereignty internationally—such as by accepting the jurisdiction of an international tribunal or joining an IO—to tie the hands of future governments or to send credible signals to foreign or domestic audiences. In accordance with Moravcsik,Footnote 87 we define stable democracies as countries that have had Polity scores of 6 or higher for at least thirty years. New democracies are states that have current polity scores of 6 or higher and the reference category are nondemocracies.

We find no evidence for this hypothesis (Model 5), and including the democracy variables in the other models does not significantly alter their findings. We suggest that the new democracies hypothesis has less relevance for erga omnes effects. States make no formal commitment to IC judgments against other countries. It is thus unclear why complying with these judgments (or failing to do so) would help (or hurt) a state's credibility. Moreover, there is no intuitive relationship between regime type and adherence to IC precedents. It is not obvious, for example, why the sovereignty costs of an IC's expansive interpretation would accrue differently to stable democracies than to new democracies. In fact, all ECtHR landmark judgments on LGBT rights involved stable democracies, but both stable and new democracies have recognized the erga omnes effect of such judgments.

Most of the control variables have coefficients in the expected direction, although they are not always significant. Most importantly, the predicted ECtHR vote has a strong positive effect on the likelihood of policy change. This suggests, unsurprisingly, that the factors that influence judges to change their minds also impact policy change. The results are substantively identical when we control for the LGBT-friendly policies not affected by ECtHR judgments and when introducing all variables together, and in a minimal model with only the predicted vote change as a control. Estimating higher-order polynomial time trends also does not affect the main results.Footnote 88

Conclusion

Two related questions motivated this article. First, do IC judgments influence states that are not party to the dispute? Second, are ICs agents of change or do their decisions reflect preexisting social and political trends? In the context of ECtHR judgments on LGBT rights, we find evidence that even where international judges take social trends into consideration, they nonetheless retain considerable discretion and can encourage policy change by noncompliant countries under the right domestic political and institutional conditions.

In particular, ECtHR judgments increase the likelihood that all European nations—even countries whose laws and policies the court has not explicitly found to violate the European Convention—will adopt pro-LGBT reforms. The effect is strongest in countries where public support for homosexuals is lowest. We are working with observational data, and so cannot entirely exclude the possibility that this effect is caused by unobserved factors that influence both ECtHR judgments and changes to national policies. Yet the statistical impact of ECtHR judgments survives our best efforts to address such concerns, including explicitly modeling likely ECtHR votes and controlling for LGBT issues not affected by ECtHR rulings.

Perhaps our most unexpected finding is that the erga omnes effect of ECtHR judgments is stronger in countries where public support for LGBT rights is relatively low. We attribute this result primarily to national courts' ability to strike down domestic laws based on their incompatibility with the convention, and to the increased political salience of an issue following ECtHR judgments that can trigger policy change when the government in power is not ideologically opposed to reforms. In countries with high public support, sympathetic political parties do not need the incentives provided by an ECtHR ruling, but in low-support countries a judgment from Strasbourg can help legitimize and justify policy change. Moreover, courts with international review authority can step in if the legislature does not adopt reforms.

Our finding does not imply that the ECtHR aggressively pushes countries to adopt policies that governments and publics oppose. Rather, the Strasbourg Court engages in a kind of majoritarian activism. It recognizes LGBT rights claims that it had previously rejected only when at least a majority of CoE member states have already done so. Decisions that embrace an expansive interpretation of the convention at this juncture appear to influence lagging countries to adopt progressive LGBT rights policies earlier than these countries otherwise would have. We estimate that a judgment encourages an average of eight states to alter their policies over a decade. Since these human rights protections have meaningful consequences for large numbers of Europeans, this is a nontrivial effect. But it is also a more modest effect than both boosters and critics of ICs often attribute to international judicial rulings.

Our empirical analysis is motivated by a theoretical framework that analyzes how the discretionary interpretative choices of ICs can have systemic influences on national laws and policies. Consistent with a burgeoning literature on compliance with international law, we argue that this effect is conditional on domestic institutions and compliance constituencies. Our framework advances this literature by emphasizing the influence of international law on domestic judicial review and on the partisan control of government. Our findings also have implications for the rapidly growing number of decisions by ICs and quasi-judicial monitoring bodies. We thus conclude with a roadmap for future research that considers how the erga omnes effect may operate across the broader terrain of international law.

First, the mechanisms of influence we identify potentially apply not only to ICs that issue legally binding judgments but also to IC advisory opinions and to the many international commissions, committees, and expert bodies that review government conduct and issue nonbinding decisions and recommendations. There are many differences between soft and hard international law. But those differences have less relevance for the erga omnes effect, because international decisions are always nonbinding for other states regardless of whether the decisions are obligatory for the parties to a particular dispute. Our findings thus open new avenues of inquiry for research on soft international law.

Second, our findings have particular relevance for other human rights regimes, in which decision makers interpret open-textured and evolutionary norms that are shaped by developments in international, regional, and national law. The inherently expansive nature of these norms means that ICs and international review bodies—such as the courts and commissions of human rights in the Americas and Africa, and the numerous review mechanisms established by specific human rights treaties and by the UN Charter—are likely to encounter erga omnes issues similar to those that the ECtHR has experienced. For example, the principles developed by UN treaty bodies when analyzing state party reports and complaints from individuals and when drafting general comments may influence national courts that review challenges to government policies.

Third, our analysis of the ECtHR may not translate as directly to ICs in other issue areas. For example, domestic courts generally do not interpret WTO treaties or apply the decisions of the WTO dispute-settlement system. Nevertheless, the issues of discretionary interpretation and systemic influence are pertinent to the WTO Appellate Body, which establishes legal principles (for example, the illegality of zeroing) intended to affect the behavior of all member nations. The research design we apply to the ECtHR could therefore be adapted to analyze the erga omnes effects of other ICs, although the precise mechanisms and conditions may differ or have different weights.

Finally, our study reveals that scholars studying ICs should look beyond narrow questions of compliance to consider the systemic influence of IC interpretations of international law. A judgment that a defendant state does not implement may still be effective if the court's reasoning is widely adopted by other states. The UK has not (yet) complied with the ECtHR's prisoner voting rights judgment against it, but the ruling led other European countries to change their policies through the decentralized mechanisms we identify. The opposite result may also occur. A country that litigates a dispute and loses could narrowly comply with the ruling, while other states retain policies that contravene the IC's interpretation of their treaty obligations. Failing to investigate either possibility could drastically over- or underestimate the influence of ICs decisions on state behavior.