I. Introduction

Traffic violations are a part of everyday life in Mexico City. In 2016, law enforcement officers issued about eight thousand traffic fines per day, mainly related to parking violations, running red lights, and exceeding speed limits. Yet, Mexico City’s government estimates that the number of unreported violations is at least equal to the reported numbers.Footnote 1 In other words, there is plenty of bribing going on.

Police officers and citizens know the dance: the driver asks for mercy—because she was in a hurry, distracted, or not familiar with the neighborhood. The officer says he’d like to help, but he doesn’t know how. He may mention the hefty official fine associated with the violation. Ultimately, the typical interaction ends with the driver offering the equivalent of twenty dollars and the police officer letting the driver go without a citation. Both acted in morally questionable ways and engaged in an act of corruption that reflects poorly on their character and integrity. Flawed individual character seems to drive the bribery.

Imagine the same driver traveling from Mexico City to San Antonio, Texas. While driving in an unfamiliar area, she runs a red traffic light and is stopped by a police officer. Do you think she will offer a bribe? After all, judging by her previous behavior, her character is not exactly exemplary. In this new circumstance, the last thing on her mind is figuring out how to bribe the police officer. She may try avoiding the ticket, but by means other than offering a bribe. Did our imaginary driver experience a moral enlightenment when crossing the border? Or was she simply adjusting to a different set of formal rules?

The example illustrates two alternative views of corruption and its likely causes: Is corruption merely a flaw of character, or is it a rational response to a given institutional environment? If both aspects are important, which one has more weight? These questions are at the heart of academic and public-policy literature on the subject, as I discuss in Section II. Scholars from various disciplines mainly side with the narrative that, ultimately, corruption is a problem of character flaws. Policy prescriptions around the world are designed based on this understanding.Footnote 2

In this essay I challenge this understanding, arguing that it is at best incomplete, and is dangerously misleading at worst. I argue that the prevalence of virtuous acts is profoundly tied to people’s institutional environment and the incentive structure that derives from it, and that to understand the nature of corruption we should instead focus on three aspects of this connection. First, I observe that virtue itself is hard to come by. Second, I argue that it is not obvious that corruption is always a character problem, and understanding the institutional environment and circumstances (formal institutions and rules, as well as social and cultural norms) that encourage people to perform virtuous acts is extremely relevant in dealing with the problem of corruption. Finally, I explore ways in which the institutions that increase the transaction costs associated with everyday life also increase the prevalence of corruption.

I do not claim that the two explanations of the nature of corruption—character versus institutional environment—are mutually exclusive. My claim is more modest, but still important: by accepting that corruption is not merely a character problem and that formal and informal rules affect incentives in ways that make engaging in corrupt acts more or less likely, we can derive insights that can inform policy-makers working on anticorruption strategies. In developing this narrative, a first step is to examine the way corruption is characterized in the literature and to consider what that account may be missing.Footnote 3

II. The Definition and Nature of Corruption

The literature identifies three types of corruptionFootnote 4:

1. Grand corruption. Political elites sometimes use their power and influence to craft public policies that economically benefit individuals or groups and then take a share of the benefits. A classic example is the executive branch granting generous government contracts to friends and political allies. Kleptocratic regimes are traditionally prone to grand corruption.

2. Bureaucratic, or petty, corruption. Public servants that have discretionary power may use it to their advantage when dealing with citizens and even other bureaucracies. Perhaps the most pervasive manifestation of this type of corruption is asking for bribes in exchange for providing or expediting services the public is entitled to. Examples are bribes asked and paid to avoid traffic tickets or to get licenses. Notice this describes a transaction involving both public servants offering special treatment and citizens paying for getting it.

3. Legislative corruption. Sometimes political and economic interest groups can influence the way legislators vote and what type of legislation they enact.Footnote 5 In exchange for special privileges granted by legislation, interest groups may offer not only bribes, but also gifts, lavish travel for legislators and family, and other forms of compensation.

Going further, J. S. Nye identifies three different dimensions of corruption—namely, bribery, nepotism, and misappropriation.Footnote 6 Bribery relates to cases such as grand, petty, or legislative corruption. Nepotism refers to corrupt acts that assign valuable public resources based on family or friendship relationships, rather than merit, while misappropriation speaks to acts of corruption where public assets are used for private gain.

Corruption’s multiple dimensions make the concept difficult to define precisely. Further, attempting to define corruption in excessively precise terms risks compromising the richness of the phenomenon. My purpose here, then, is not to settle on a definite conception, but to suggest that corruption has multiple facets. With that limited aim in mind, for my purposes I define corruption as a situation in which a public servant has discretionary power in allocating costs and benefits among citizens, an exchange occurs between the public servant and citizen that involves both demanding and offering a bribe, and this exchange provides a privilege not readily available to citizens who do not pay the bribe. I also assume the existence of economic rentsFootnote 7 and the possibility of capturing them, as well as a relatively low probability of getting caught and/or a low penalty associated with that possibility. This working definition runs parallel to the classic one coined by Rose-Ackerman: corruption is “the misuse of public power for private or political gain”Footnote 8 and to a definition like Jain’s: “[corruption] refers to acts in which the power of public office is used for personal gain in a manner that contravenes the rules of the game.”Footnote 9

Why should we care about corruption? Rothstein and others suggest that corruption violates the principle of nondiscrimination in “the exercise of public authority.” Morally equal individuals ought to receive the same treatment from public officers. To make distinctions and offer preferential treatment in exchange for bribes or gifts—or based on family or friendship ties—is to act in a corrupt way. Kurer relates this idea of impartiality to aspects of distributional justice, and along with Lee Kwan Yew finds corruption deeply troubling because it affects fairness, transparency, and accountability—all factors that run against democratic practices and ideals.

Underkuffler suggests that “corruption, as commonly understood, is not simply a violation of law or the breach of a public duty; it is the engagement in evil, the transgression of deeply held moral norms.”Footnote 10 For her, corruption is a sin and a betrayal of trust: the corrupted have been captured by evil, succumbing to “self-involvement, self-indulgence, the loosening and discarding of the restraint of social bonds.”Footnote 11

Parker presents a similar notion, stating that corruption “is marked by immorality and perversion” and the corrupt person is “depraved; venal; [and] dishonest.”Footnote 12 Rotberg advocates adopting “ethical universalism” as the “only sustainable method of curbing corruption,” and suggests the phenomenon is deeply rooted in poor moral character. Robert Brooks describes corrupt transactions as “sins,” and engaging in corruption as the manifestation of “moral weakness.”Footnote 13

Rotberg also refers to Samuel Johnson’s eighteenth-century definition of corruption in which words and phrases such as “wickedness,” “perversion of principles,” and “depravation” describe the concept.Footnote 14 Finally, Heywood and Rose suggest that the issue of corruption is ultimately a problem of lack of personal integrity.Footnote 15 In these conceptions, corruption is a problem of character flaws.

An alternative to the above scholars’ understanding of the nature of corruption is to think of it as a vice, but one embedded in an environment, especially an institutional environment, which includes informal rules—such as cultural norms—and formal rules, such as laws and regulations.

III. The Aristotelian View of Human Action and Virtue

Being virtuous is hard. According to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, virtuosity requires not only that one does the right thing and performs a noble action, but three additional requirements: full awareness, intention, and firmness. The truly virtuous person knows what she is doing, intends what she is doing and does so with conviction and determination. This is a very high standard. Not surprisingly, according to Aristotle, not everybody can be truly virtuous.

How can one become virtuous? By practicing. Virtue “is a habit disposed toward action by deliberate choice, being at the mean relative to us, and defined by reason as a prudent man would define it.”Footnote 16 With practice one may become a better person and eventually virtuous, despite opposite natural passions or inclinations: “Virtues arise in us neither by nature nor contrary to nature; but by our nature we can receive them and perfect them by habituation.”Footnote 17 In these and the following passages Aristotle is referring to “hoi polloi,” the majority of people.

Aristotle also suggests that becoming habituated in virtue requires performing virtuous actions beginning at an early age. But how could a person acquire virtue by habit if she is not already a virtuous person habituated to perform virtuous acts? Aristotle’s answer—relevant for this essay’s narrative—is that acting virtuously and being virtuous are different things. The distinction between virtuous acts and virtuous character is useful. The latter is the disposition to perform the former.

Acting virtuously is a necessary but not sufficient condition for being virtuous. As I mentioned, knowledge, intent to act virtuously for its own sake, and firmness are additional necessary conditions. Individuals who are in the process of becoming virtous are constantly challenged by its requirements. Every day, we have obligations to perform virtuous acts. When choosing how to act, to some extent, we also choose how to navigate toward virtue.

Again, choosing to repeat virtuous acts—practicing—is what makes us better at performing these acts, and ultimately may transform us into virtuous individuals. Julia Annas suggests that trying to become virtuous is like attempting to become a master piano player: it requires constant, daily hard work.Footnote 18 It also demands awareness, passion, and dedication. But what informs choosing between alternative acts? Are there outside elements that make it easier—or harder—to become a master violin player? The answer is yes.

Aristotle suggests that legislation is a crucial factor in creating conditions to habituate citizens to act virtuously: “It is difficult for one to be guided rightly towards virtue from an early age unless he is brought up under such [that is, right] laws; for a life of temperance and endurance is not pleasant to most people, especially the young. For these reasons, the nurture and pursuits of the young should be regulated by laws, for when they become habitual they are not painful.”Footnote 19

According to Aristotle, laws inform our choices and set mutual expectations about proper conduct. Therefore, legislation may provide the right amount of coercion so that individuals can overcome their passions, and make the right choices. But is forcing people to act virtuously a true measure of virtuosity? Not according to Aristotle’s conception of virtue. That is why he also emphasizes the importance of moral education in attaining virtue.

Through moral education we learn the reasons to appreciate and receive pleasure from what is good, and to reject and be disturbed by what is bad: “we should be brought up from our early youth in such a way as to enjoy and be pained by the things we should.”Footnote 20 In this sense, virtue benefits its possessor. We can learn why moral acts are worthy choices. While an individual can be compelled by law to perform a virtuous act, she can also learn to enjoy doing the right thing—hence the role of moral education—and may continue choosing the right act. Acting virtuously becomes a habit.

Aristotle is cautious about the permanent prospects of this marriage of coercion and reason. He says that without moral education, “laws would be needed for man’s entire life, for most people obey necessity rather than argument, and penalties rather than what is noble.”Footnote 21 Humans need a constant reminder of what it means to be good and what that really entails. Here it is useful to remember that Aristotle is thinking of most individuals. Most people are not virtuous, and thus need coercion and knowledge—in his mind in the form of legislation and moral education—to navigate the path toward virtue.

At the same time, Aristotle is aware that legislation and moral education may not be enough to lead individuals to live a virtuous life. In his view, because virtuous action must be specific to the individual actor, and laws must be universal, it is impossible to enact legislation that goes beyond providing general guidelines of conduct. Additionally, while moral education provides valuable ways to assess choices, it is only through experience that one can truly find one’s own intrinsic motivation to be virtuous. Both law and education have their limits in both influencing and informing the pursuit of virtue.

For example, a gap between the enactment and enforcement of legislation may be incompatible with the incentive to seek virtue: legislation—even sound laws—in the hands of bureaucrats with discretionary power creates the incentive to act corruptly. And using moral reasoning to recognize the inadequacy of a choice may not be enough to deter the agents of the law from choosing the non-virtuous acts. The point is not that the law or reason may prompt corrupt acts, but that the incentive structure affects costs and benefits at the moment of choice and determines what actions the agents choose.

The driver in Mexico City may know that what she is doing is wrong and that it violates the law. She may even feel guilty. But this does not provide enough of an incentive for her to act virtuously. In this sense, then, corruption is more than just a problem of a morally rotten individuals or legislation that fails to reverse the rot. It is also an institutional problem where many actors facing choices assess the costs and benefits of the options under a given incentive structure. If choosing to do the virtuous act (not paying a bribe) imposes unreasonable burdens—and is not already pleasurable in its own right—then it is hard to facilitate the Aristotelian habituation process.

I suggest that in modern economic terms, Aristotle’s points speak to the importance of incentive structures in inducing non-virtuous individuals—the majority of people—to perform virtuous acts. By influencing costs and benefits, not only legislation and moral codes but also social norms (among other institutions) can make some choices more palatable than others. This is true not only in economic respects, but also in relation to moral aspects of choice. Institutions and incentives, both internalized and external, affect the prospects of becoming a master piano player or a virtuous person.Footnote 22

Aristotle’s account of virtue and virtuous acts helps us anticipate the potential for success or failure of anticorruption initiatives. Setting up an anticorruption program that assumes individuals are fully virtuous would be disastrous. In tackling corruption, it is more reasonable to recognize that most of the time we will not have individuals with perfectly virtuous character. A more useful way to think about the problem is to ask ourselves what type of institutions and rules discourage corruption. Then we can economize on virtue—that is, depend less on the existence of virtuous public servants and citizens—while incentivizing individuals to do the right thing.

IV. Agency Problems and Corruption

The economic theory of agency problems can inform a systematic exploration of the role of institutions. The theory analyzes situations in which one actor—the principal—delegates decision making to another actor—the agent. The principal then intends the agent to act and assign resources in ways conducive to achieving the principal’s objectives. Classic examples of principal-agent pairs are a car owner and a mechanic, a patient and a doctor, and stockholders and managers. In these cases, the car owner, patient, and stockholders delegate authority to the mechanic, doctor, and manager, respectively, so the latter can then act and pursue the former’s goals.

Several problems emerge within agent-principal relationships.Footnote 23 The main one is that they may create occasions for opportunistic behavior because of informational asymmetries and divergent interests.

The agent normally has better information than the principal about the agent’s own skills and talents, how to allocate resources efficiently, what type of decisions would be better in pursuing the principal’s interest, and how to evaluate alternative courses of action. Additionally, monitoring and evaluating the agent’s behavior is costly. Taken together, these conditions incentivize the agent to act opportunistically. The most prevalent outcomes are that the agent exerts low effort in pursuing the principal’s goals or completely deviates from pursuing them. The challenge is to design mechanisms that align the agent’s goals with the principal’s objectives. Economists have developed two concepts in studying the problem: adverse selection and moral hazard.

Adverse selection happens when asymmetric information and divergent interests are present prior to an exchange or contract between the two parties. Moral hazard occurs when the problems emerge after a deal is struck, thus modifying the agent’s behavior.

Imagine a case of adverse selection. A seller, or agent, has a better understanding of the value of a good or service than a buyer, or principal, does. He could potentially exploit this information asymmetry at the expense of the buyer. Used-car markets are prone to adverse-selection problems: owners know better than buyers the true condition of the used car and can take steps to misrepresent the car’s quality to a potential buyer, in attempting to sell a “lemon”—a car in poor condition.

In general, this may prevent transactions from happening at all, because the principal anticipates a likely abuse. When the principal is certain about quality, the transaction will occur and will be a win-win event. But if the principal is uncertain of the true value of the good, then its willingness to trade decreases or completely disappears.

Principals’ inability or high cost of screening agents makes the situation worse. Principals would like to know better what type of agents they are dealing with, while honest agents would like to signal they are trustworthy. Nobel Prize winner George Akerlof developed a framework to understand how to overcome adverse-selection problems in the “market for lemons” by using signaling and screening mechanisms such as reputation, all of which have at their core attempts to reduce asymmetric-information problems.Footnote 24

In contrast to adverse selection, moral hazard is when the agent’s behavior changes after the exchange occurs or the contract is entered into. Insurance and car-rental markets are good examples of moral-hazard problems. Once an insurance policy or a warranty is obtained, this may modify the buyer’s behavior in ways at odds with the ideal type of behavior the seller would like to observe. Car insurance tends to incentivize reckless behavior because the insured individual would not bear the full cost of an accident. And people tend to be less careful with rental cars than with their own vehicles. Insurance and car-rental companies react by increasing premiums on and rates for “high risk” customers, such as drivers under a certain age.

In the moral-hazard case, it is the inability to monitor, or the high cost of monitoring, behavior that makes things worse. An agent may even try to conceal her “true type” to the principal, exploiting asymmetric information once an agreement is reached. Moreover, moral hazard may emerge even in the absence of asymmetric information if the agent realizes, after the exchange occurs, that it is in her interest to deviate from the principal’s preferred behavior, even if that potentially imposes costs on the latter. In these situations, the principal lacks the necessary information to fully anticipate the agent’s behavior.

Corruption research has used the principal-agent model to explore corruption’s origins and offer prescriptions. Ugur and Dasgupta present a comprehensive analysis of one hundred fifteen corruption studies where all “adhered to an explicitly-stated principal-agent approach to corruption, or their account was closely related to that approach.”Footnote 25 Similarly, Persson, Rothstein, and Teorell as well as Ivanov and Lawson all find that most anticorruption programs are designed based on a principal-agent framework.Footnote 26

The principal-agent approach to corruption assumes a group of actors as the principal, delegating public tasks to another collective body, the agent. Becker and Stigler’s analysis assumes that political rulers are the principal and the bureaucracy is the agent.Footnote 27 Corruption emerges when an “agent betrays the principal’s interest in the pursuit of his or her own self-interest,”Footnote 28 exploiting the previously described informational asymmetries. Rose-Ackerman suggests that bribery makes agents put their own interests ahead of those of their principal.Footnote 29 Similarly, Klitgard argues that corruption occurs when an agent betrays the principal’s public interest.Footnote 30

Anticorruption strategies informed by this framework fall within traditional ways to deal with principal-agent problems—namely, attempts to align incentives and reduce opportunistic behavior. Examples include screening to avoid hiring bad agents, and monitoring to assess their behavior and performance. This approach to the study of corruption has its critics.

Per the discussion in Section III, relying on the existence of virtuous principals that will perfectly enforce anticorruption measures may not be the best strategy. That would be to assume, using Persson’s term, the existence of “principled principals.”Footnote 31 He argues that “we should expect the key instruments to curb corruption in line with the principal–agent anticorruption framework—that is, monitoring devices and punishment regimes—to be largely ineffective since there will simply be no actors that have an incentive to enforce them.”Footnote 32 Mungiu-Pippidi goes further and suggests that “more often than not . . . ‘principals’ may serve as a patron or gatekeeper for corruption, if not the actual capo di tutti capi.”Footnote 33

As a response, these and other critics offer a different conceptualization of the problem of corruption suggesting that it more closely resembles a collective-action problem. More specifically, borrowing a concept developed by Elinor Ostrom, they suggest the existence of a collective-action problem of the second order.Footnote 34 In a nutshell, a second-order collective-action problem is a coordination challenge: I do what I do because everybody else is doing the same, even if all of us could be better-off acting differently. No one has incentives to deviate from current behavior, even if it is suboptimal, because they expect others to maintain their current course of action.

Rothstein puts it very clearly: “Why would agents that either stand to gain from corrupt practices or who can only lose by refraining from corruption at all be interested in creating such ‘efficient’ institutions?”Footnote 35 Underkuffler offers a similar notion: “If corruption is the usual medium of exchange in the world that citizens know, they will also know that they are in a serious comparative disadvantage if they fail to engage in it.”Footnote 36

These problems can be modeled using analytical tools such as game theory.Footnote 37 A full exploration of the game-theory framework is beyond the scope of this essay, but the intuition behind it is simple: shared expectations about how others may act may trap societies in inefficient arrangements. Corruption may be difficult to eliminate not only because agents’ types and actions are difficult to monitor, but because an overall credible commitment in which all agents and principals stop taking and asking for bribes may not be possible to craft. The prospects for escaping the corruption trap may collapse with the possibility of a few individuals not honoring the agreement, thus imposing costs on others who do. Trust is crucial.

The principal-agent and collective-action approaches to corruption are not necessarily competing explanations. On the contrary, they can be complements. It is possible that the collective-action problem of being stuck in suboptimal, corrupt equilibriums includes plenty of perverse principal-agent interactions. And agency theory can benefit from considering the role of trust and coordination when dealing with corruption at large. After all, individual agents’ decisions to act in corrupt ways do not occur in a vacuum, but within a larger social context.

Marquette suggests that “monitoring, transparency, and sanctioning—all variables that impact individual calculations of whether or not to engage in corruption—are also weighed against the potential influence of group dynamics that may impact on the likelihood of free riding.”Footnote 38 Poor screening and costly monitoring may coexist with individual lack of incentives to deviate from others’ corrupt behavior. Both theories offer valuable insights. Moreover, there is an underexplored insight from the principal-agent approach that helps us think about the corruption-as-a-character-flaw narrative. This insight is related to the ex-ante and ex post elements of agency problems.

A simple example to further clarify both concepts: Imagine a restaurant that offers an all-you-can-eat buffet. Now imagine patrons that overeat and while doing so waste food—a problem the restaurant’s owner wishes to minimize. It is possible that the buffet attracts individuals that are already predisposed and had the intention to overeat without caring if they waste food. But it is also likely that some individuals were not planning to overindulge, but once there and in the face of abundant food, they became careless and filled their plates beyond their appetite, resulting in waste.

Is this an adverse-selection or a moral-hazard problem? In other words, is overeating and waste an ex ante or an ex post behavior? The answer is important, because adequate strategies to prevent the problem may be radically different. The same question can be asked of the corruption problem.

Is corruption an ex ante or an ex post problem? An adverse-selection explanation suggests that public service may attract the already corrupted, those seeking to take advantage of their power for personal benefit. A moral-hazard account would be different. Individuals might not pursue public office to misuse their position, but once they have access to privilege-granting opportunities or are immersed in an environment where corrupt behavior is the norm, they choose to act in corrupt ways. It seems the adverse-selection narrative is closer to the poor-character explanation of corruption, whereas the moral-hazard problem is more closely related to the institutional-environment explanation. Let us further explore both possibilities.

Adsera, Boix, and Paine suggest that lack of accountability may increase opportunistic behavior among politicians and bureaucrats, thus increasing corrupt behavior.Footnote 39 This is a monitoring problem and characterizes corruption as a moral-hazard, institutionally driven problem. If this is the case, institutions such as checks and balances may serve to deter corrupt behavior. Similarly, political agencies may try to monitor bureaucrats. Shleifer and Vishny frame the problem as an ex post challenge,Footnote 40 and as Barro suggests, voters’ ability to impose costs on government behavior ex post is critical in reducing incentives for corruption.Footnote 41

Conversely, if the corruption problem is framed as ex ante (adverse selection), the challenge is preventing the already-corrupted opportunistic individuals from taking office and having discretionary control over valuable resources and corruption rents. Teorell suggests that reducing discretionary power may prevent individuals from behaving badly.Footnote 42 Poor institutions and suboptimal rules may increase the value of corruption rents, and thus adverse selection may be more prevalent. Of course, no politician or bureaucrat would readily admit tendencies toward corruption. That explains the emergence of screening strategies such as asset disclosure before running for office, and supposedly independent anticorruption monitoring agencies that review profiles before hiring public officers.

The ex-ante and ex post views of corruption are not mutually exclusive, and it is possible to observe both dynamics in the real world. However, as I elaborate in Section V, prevalent public-policy prescriptions treat corruption as an adverse-selection problem: the problem is viewed as preventing the corrupt from taking control. Conditions that provide agents opportunities for rent extraction (that is, gaining wealth from citizens by virtue of the agents’ power) without related risks attract corruption-predisposed individuals. In fact, some cultural contexts see entering corruption-prone institutions as the only way to gain wealth. Those seeking to enter bureaucratic structures do so expecting to extract illegal rents.Footnote 43

It is valuable to complement this view with an ex post analysis of corruption. If uncertainty about behavior, costly monitoring, and asymmetric information are prevalent, corruption may be inevitable. If the existence of and prospects of appropriating economic rents are influenced by the institutional framework, then corruption may be better characterized as a moral-hazard problem. Choices are not merely determined by the character of the individual but by the institutional framework that creates an incentive structure.

Under bureaucratic structures that have highly corrupted officers, low-level subordinates may not have another alternative than to adapt to the institutional environment where corruption rents are demanded across the organization. Imagine a police officer that is honest and willing to perform virtuous acts entering a rotten corporation. If the corporation’s leadership demands bribe quotas from the officer in order to keep his job, he faces a difficult choice. Acting virtuously may not be possible, or may be dangerous. Furthermore, the corruption of some encourages additional officials to accept bribes until all are corrupt, and only those willing to take part in the corruption will remain in charge. This situation resembles what we previously characterized as a collective-action problem.

Again, providing external incentives for honest behavior or establishing mechanisms to increase the probability of detection and punishment may also be ineffective. If the monitoring agency also is constrained by poor institutions, prescriptions grounded in screening strategies such as transparency may be inadequate and even counterproductive. Transparency initiatives may offer dishonest agents something else to sell: the right to have them look the other way.

Honest officials will get displaced if the corruption is prevalent at all levels. Ex post corruption may then contribute to the survival of a suboptimal social equilibrium, a difficult one to escape.

Again, my argument is not that adverse-selection and moral-hazard explanations are at odds. Both concepts are useful and should be used carefully when assessing specific situations. But a portrayal of corruption as character driven, and thus as an adverse-selection problem, is incomplete. Certainly, corruption may have a bad effect on individual character: it may decay moral integrity.Footnote 44 But it is not obvious that poor character is the only or main cause of corruption. Therefore, it is necessary to enrich the adverse-selection framework with a narrative driven by rules and institutions, such as the moral-hazard conceptual framework.

While some individuals may be fully committed to virtue and honesty under all conditions, posing no ex ante or ex post challenges, others may be more strategic in their choices. In addition to moral considerations, balancing other costs and benefits may inform individual choices regarding corrupted acts. And in fact, under certain circumstances, corruption may entail some benefits, both at the individual and the social level.

V. Transaction Costs and Economizing on Virtue

To be sure, as Rotberg suggests, “an occasional corrupt act, in isolation, may be efficient, but routinized corruption never is, and is always distortive.”Footnote 45 Regarding the latter, Klitgard says corruption only increases uncertainty among individuals about the “likely benefits of their productive activities,”Footnote 46 creating a misallocation of valuable resources within a society. For example, corruption can both prevent the most efficient service providers from getting access to government contracts and impede the entry of new contractors. Rose-Ackerman and Palifika’s empirical work links high corruption with high income inequality, also suggesting that corruption can increase the costs of transactions and everyday life in a society.Footnote 47

These arguments suggest little or no social benefits of corruption. But are there any circumstances where corruption may be beneficial for a society? Nye hints at such circumstances: “it is probable that the costs of corruption in less developed countries will exceed its benefits except for top level corruption involving modern inducements and marginal deviations and except for situations where corruption provides the only solution to an important obstacle to development.”Footnote 48

There is something worse than an inefficient corrupt government: an inefficient honest one. In the latter, nothing will get done, since overcoming bureaucratic inefficiencies—that is, obtaining permits and dealing with cumbersome regulations—may require the use of bribes and side payments. Leef and Huntington’s research suggests that a little corruption may improve overall efficiency,Footnote 49 and Marquette identifies it as a means to solve real problems that couldn’t be solved using regular methods. Scott also suggests that corruption may be the best—if not the only—way to gain access to necessary public services.Footnote 50 I would add that in several contexts it may be the only way to avoid real harm.

The so-called functionality argument suggests that “corruption provides an understandable method of allocating scarce goods, like a birth certificate, a medical practitioner’s permit, a driving license, public jobs, or even a massive construction contract.”Footnote 51 Under these inneficient circumstances, the overall efficiency gains may be greater than the social costs. The concept of transaction costs can be helpful in exploring this possibility.

When exchanging goods and services, individuals incur direct costs, most notably the price paid for such items. There are, however, additional costs associated with exchange. Ronald Coase developed the concept of transaction costs to identify the costs associated with reaching agreements, implementing the agreements, monitoring counterparties, and enforcing contracts and exchange arrangements.Footnote 52

When buying a good or service, buyers need to search for and process information about availability, quality, and so on. When opening a new business, entrepreneurs must obtain permits and follow regulations. When negotiating a contract, terms need to be defined and assessed. And if a contract is not honored, legal processes must be followed to enforce the terms. All these are examples of transaction costs.

Transaction costs are extremely important. Evidence suggests they are related to a society’s ability to innovate, engage in commerce, and generate prosperity.Footnote 53 They are important enough to influence whether deals will be made, businesses opened, and contracts properly enforced. Thus, it is important to understand what factors may increase and reduce transaction costs. North suggests institutions are the main factor driving transaction costs. He defines institutions as “the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints. (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights).”Footnote 54

Examples of formal institutions are legislation, regulations, and codified norms. Examples of informal institutions are social norms and cultural codes. Formal rules tend to have established formal enforcement structures, often associated with coercion mechanisms controlled and exerted by collective bodies—that is, states. Certain mechanisms enforce informal rules as well, but these tend to be more organic and informal, often based on conventions and reputational concerns. The distinction is not neat, but it captures some interesting features of both formal and informal institutions.

Institutions vary across societies: for example, regulations and cultural norms affecting behavioral expectations are distinctive. But regardless of their differences, they have something in common: they affect transaction costs. How is this related to corruption? I argue that corruption—particularly petty corruption—may emerge as a strategy to cope with inefficient institutions.

In other words, if institutional quality is poor, corruption may be the way citizens both reduce transaction costs and avoid potential real harm. And while Nye, Leef, Scoot, Marquette, and others have discussed the potential social benefits of corruption beyond the individual transaction, suggesting that corruption may be beneficial in some instances, they have largely missed the connection between transaction costs, corruption, and virtue.

Under inefficient institutions, performing the corrupt act may be the rational response. Choosing between alternative courses of action always involves an opportunity cost. That is also true when choosing between a morally right action and a morally wrong one. Sometimes the cost-benefit assessment may lead us to choose the non-virtuous act. For example, if paying a bribe reduces significantly the transaction costs of opening a business, acting virtuously—not paying a bribe—imposes an unreasonable burden on the business owner.

The cost of the bribe may be well below the economic benefits. In this scenario, being corrupt is not merely a problem of character, but one of high transaction costs derived from inefficient formal institutions. Therefore, choosing between acting virtuously and not may be contingent on the institutional environment affecting transaction costs.

Under these conditions, depending on citizens’ virtue to avoid corruption may not work. If acting virtuously is one choice among many, and a costly one, what is needed are institutions that economize on virtue while reducing corruption.Footnote 55 By this I do not mean to suggest that virtue is something for sale in a market transaction or a necessarily scarce resource. What I mean is that rules that rely less on the existence of fully virtuous individuals to prevent corruption may be more effective than institutions that assume such virtuous individuals as the starting point. As discussed in Section III, the assumption that individuals are fully virtuous can be very problematic when thinking of the majority of people.

Moreover, tolerating and engaging in corruption—choosing the non-virtuous act—may be the individually efficient path in societies with poor institutions that increase transaction costs for engaging in otherwise-productive activities. Appeals to doing what is right and using moral education to induce virtuous behavior will most likely not be sufficient. Under inefficient institutions that increase the transaction costs of making mutually beneficial exchanges, corruption may even be socially acceptable, because it helps in dealing with inefficient bureaucracies and cumbersome government regulation. What seems immoral for outsiders is acceptable and efficient for those engaged in corruption.

Critics such as Rotberg argue that “people accept it [petty corruption] because they see no way to avoid it.” Furthermore, “the total cost to society in cash and time wasted is still significant and damaging economically. The practice also undermines the very structure of trust of every society so riddled with routinized petty bribery.”Footnote 56 He has a valid point and presents an important word of caution. We can elaborate it by further considering the ideas of transaction costs and institutions.

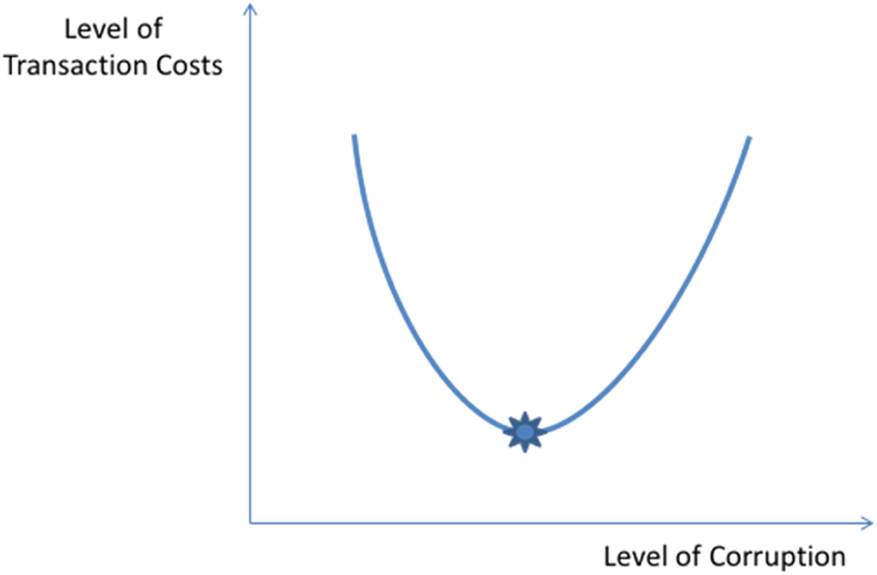

While petty corruption may have some positive overall effects, these effects may not be permanent and, more importantly, most likely are not linear, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Transaction Costs and Corruption

In the left-hand segment of the curve (before the inflection point), more corruption reduces the transaction costs of making individually and socially beneficial exchanges. That is the situation previously depicted: inefficient institutions are overcome by engaging in acts of corruption. Here, acting virtuously may be extremely costly. Corruption is a means to make things happen: it facilitates the process, for example, of opening a business, getting a building permit, or obtaining a professional license. This is the world described by scholars such as Leef, Huntington, and Marquette.

In the right-hand segment of the curve (after the inflection point), more corruption increases transaction costs. In this case, officials asking for bribes make it extremely difficult and costly for ordinary citizens to carry out everyday productive activities. When a society generally enforces functional institutions, corruption may become a net loss. Instead of facilitating transactions and economic exchanges, corruption impedes them. It becomes a source of wasteful special privileges where the gain of one person is the loss of another. Here, I agree with one of Rotberg’s arguments: “Societally, corruption is clearly harmful. It distorts priorities, produces manifest class and personal inequalities, impedes economic growth, and often creates direct harm.”Footnote 57

It is not obvious that corruption is always socially damaging or always a positive net force. If paying a bribe reduces the transaction costs of obtaining an important benefit or reaching a relevant goal, it is hard to refrain from paying the bribe. Moreover, transaction costs are relevant in understanding whether corruption can yield benefits beyond individual transactions, positively affecting the overall performance of a society, and at what point those potential social benefits reach a limit.

To explain how exactly the inflection point is affected by institutional quality goes well beyond this essay’s objectives. Answering that question may be a separate research program. But the considerations presented in this section about the potential effects institutions have on transaction costs and corruption may inform policy makers in important ways.

VI. Some Policy Guidelines

This essay’s narrative develops a few insights. First, there is a difference between being virtuous and acting virtuously, and being virtuous is extremely hard. Thus, assuming fully virtuous individuals as the starting point to fight corruption is problematic and potentially misleading. Second, it is not clear that corruption is always a character problem. While public office may attract corrupt individuals (an adverse-selection problem), an inadequate institutional incentive structure may induce the honest to act in corrupt ways (a moral-hazard problem). Third, if some forms of corruption reduce transaction costs, acting virtuously may become too costly a choice.

These insights can inform anticorruption strategies. The intention is not to provide a recipe that if followed will solve the corruption problem. The aim is more modest: to provide three general guidelines that, if followed, may increase the probability of success of anticorruption programs. I number them just for the sake of clarity, not suggesting a series of steps. And while explored separately, they are in fact complements whose success depends on the others.

(1) Doubt solutions that start with the assumption of virtuous public officers and citizens. Placing the burden of solving corruption mainly on reforming the character of those in charge is particularly problematic.

This runs counter to the main elements of policy prescriptions made by other scholars. For example, Rotberg ends his excellent book The Corruption Cure with a fourteen-step anticorruption program. The first step states, “The nation seeks, elects, or anoints a transformative political leader embodying the new political will; this leader will commit herself or himself to an all-out battle against corruption in and throughout her or his administration.”Footnote 58 In his analysis, “The broad socialization of the norm of ethical universalism is the ultimate goal of all anticorruption crusades.”Footnote 59

While Rotberg alludes to some institutional changes, the character-based narrative dominates his program’s prescriptions, including a new anticorruption commission, auditor general, and judges, all composed of responsible individuals with skills, vision, and “implacable integrity.” It is not until step thirteen that an institutional reform is suggested—abolish and simplify regulations while reducing discretionary power—without an appeal to good character as indispensable.Footnote 60

Now, of course strong and honest leaders would help in fighting corruption. But where can we find such extraordinary individuals? As explored in Section III, placing our hope for change in the existence of virtuous individuals may not be for the best. In some sense, the existence of virtuous individuals may be the consequence of effective anticorruption measures, not its precondition. Meanwhile, coercion to act virtuously may be necessary.

(2) Seek institutional changes that reduce transaction costs and opportunities for abusing discretionary power.

As discussed in Section IV, not all individuals acting in corrupt ways do so because of poor character. Some are reacting to an inadequate existing structure that creates moral-hazard problems. Therefore, effective anticorruption programs should privilege institutional change that modifies such an incentive structure. This includes approaches seeking to reduce the economic rents of corrupt behavior, such as reducing both the range of policies that can be enforced by corrupted officials and their discretionary power, and strengthening laws and enforcement mechanisms while offering better wages to public servants.

At the same time, we should simplify regulations and reduce transaction costs, particularly those related to everyday activities that impact productive exchanges among citizens, such as granting licenses and permits. If, as we explored in Section V, individuals use corruption to reduce transaction costs, simplifying and eliminating cumbersome regulations may eliminate or at least reduce the need for bribes and side payments.

Now, it is important to recognize that institutional change faces its own very important challenges. For example, Pereira, Melo, and Figueiredo suggest that attempts to reduce discretionary power “can induce high officials to become even more corrupt as a means of co-opting their inner circle and ensuring their own economic well-being once they are out of office.”Footnote 61 Enacting more rigorous penalties and creating anticorruption structures may not be enough.

In fact, if corruption is an adverse-selection problem and an attempt to reduce transaction costs, stricter laws may be counterproductive. They simply create something else to sell. This includes strategies creating anticorruption and transparency agencies. As Rose-Ackerman suggests, the very institutions charged with creating and upholding the law tend to be the most corrupt ones: bureaucracies, legislatures, judiciary power, police corporations, and so on.Footnote 62

If the concern is the misuse of public office, giving monitoring power to political actors could just aggravate the problem. New legislation and bureaucratic structures may create new incentives for agents that previously did not have the ability to grant special privileges. Similarly, offering better salaries without pairing them with more effective monitoring and strict penalties for misbehavior may be useless. Society may end up with better-paid corrupt public servants.

Despite these challenges, changes in formal institutions must be pursued relentlessly as part of an effective anticorruption strategy. If, as described in Section IV, corruption has some elements of a collective-action problem, institutional change may appeal to a collective sense that corruption is ending, thus making the emergence of a credible commitment more likely. Here moral education may play an important role as well.

(3) Pursue a wide moral-education initiative as a complement to institutional change.

A moral-education initiative may nurture a useful transformation in public perception, changing the belief that the only way to advance one’s interest is to abuse others and to demand and offer bribes. This effort should target public officers and citizens at large. If corruption has some features of a collective-action problem, such as the ones described in Section IV, the education initiative may also help change expectations of what others will do when facing a choice between acting virtuously or corruptly. This can help craft a credible commitment to leading a society out of a suboptimal, corrupt equilibrium.

However, to succeed, this education program needs to do more than just promote the importance of acting virtuously on moral grounds. Appeals to doing what is right and not being corrupt may fall short if the new institutional incentive structures are not perceived as an effective change. This may hurt the legitimacy of the whole anticorruption program. In fact, Collier and Mungiu-Pippidi argue that a failed reform without effective institutional change may only create more outrage and cynicism in a society.Footnote 63

Changing cultural norms and informal institutions is a hard and slow process. Education may help. A change in ideas about the effectiveness of honest behavior may impact informal institutions, including norms and beliefs. If ideas are transformed in the aftermath of effective institutional change, perhaps a virtuous circle may emerge, where citizens demand further changes. Then, even if politicians are not virtuous individuals, it would be in their interest to enact and enforce effective institutions that do not rely on corruption to reduce transaction costs.

VI. Conclusions

Corruption must be studied as an interdisciplinary phenomenon. Economic, moral, and political incentives matter in understanding corruption. While total elimination of corruption may never be possible, changes that increase the overall efficiency and legitimacy of state and social institutions may have positive effects in this regard. In this sense, attempts to solve the problem of corruption are ultimately attempts to reduce transaction costs of prosperity-enhancing economic and social exchanges. The challenge in crafting effective anticorruption strategies is this: Where do we start?

This essay’s analysis suggests that if corruption is not merely a problem of bad character, assuming and placing the burden of solving it on the existence of virtuous individuals that will fight and resist the temptations of corruption may not be a good starting point. This caution likewise applies to programs mainly grounded on moral education and appeals to ethical transformations. A more effective strategy privileges institutional change, particularly a transformation of formal rules to reduce transaction costs associated with productive activities and to increase the costs of choosing corrupt acts.

Inefficient institutions—including inadequately designed or poorly implemented public policies—can incentivize non-virtuous action. We should favor institutions that economize on virtue in pursuing their objectives, reducing the opportunities for the vicious to profit and increasing the incentives for ordinary individuals to behave virtuously. If corruption is a way to deal with injustices—to avoid abuses of power—then offering a functional alternative to corruption is crucial to reduce it or eliminate it. But that poses an additional puzzle.

Where does institutional change come from? Inefficient public policies abound. Yet they do not change. Similarly, social norms that violate minorities’ rights still exist without effective attempts to transform them.Footnote 64 And the type of corruption that increases transaction costs is rampant, particularly in the developing world. It seems institutional change in general is not easy to achieve, and transforming institutions prone to corruption is no exception.

Rose-Ackerman’s research shows that “corrupt rulers may seek an excessively large government as a means of extracting benefits for themselves” or to have means to support allies by allocating jobs and other benefits.Footnote 65 Similarly, Tsebelis suggests that numerous veto players—actors whose agreement is needed for reform—with the capacity to exert significant pressure may prevent reform from happening, particularly if they benefit from a corrupt status quo.Footnote 66 If the status quo is entrenched, what makes reform more likely? Research from scholars such as North, Acemoglu, and McCloskey, among others, suggests a few likely sources of deep institutional change:Footnote 67

First, a crisis may make the status quo unsustainable and create demands for change from powerful groups, such as the private sector, religious groups, and civil society. Crisis can trigger violent struggle, such as revolution or civil war. The problem here is that, violent or not, the direction of institutional change can go several ways, not necessarily transforming the status quo for the good. For example, corruption scandals or the disclosure of big abuses may trigger reform, but this doesn’t guarantee a positive outcome.

Second, it is essential that charismatic leaders emerge who understand that change is urgent, have the political will to pursue such changes, and are able to create coalitions that support such efforts. That said, as discussed in this essay, relying on the existence of enlightened honest politicians to solve corruption is problematic. Also, new research exploring how the character and values of political leaders impact reform processes is needed.

Third, we need a radical change of ideas within large segments of society. The rise of new ideas that reject an unjust and inefficient status quo, at the same time that better rules are crafted, accepted, and nurtured, may facilitate additional institutional transformations. Thus, real institutional change and moral education, as described in Section V, is needed. We still need a better understanding of the relative effectiveness of moral-education programs across societies.

The possible sources of institutional change are often intertwined. Their interactions are not always neat, and the path of change is not easy to navigate. In overcoming these problems, character does matter—not by assuming its existence, but by nurturing its possibilities. When corruption is a disease, it may be that the cure lies not in the hands of a perfectly virtuous leader, but in the day-to-day interactions among regular citizens who recognize that they can be made better-off by promoting a society with a new set of rules that privilege voluntary, productive exchanges over abuse, and where respecting such rules is the norm and not the exception.