In 1976, the first conference on “Islamic media” convened in Riyadh. Muslim professors, journalists, and activists from all over the world gathered in the Saudi capital to discuss “Islamic views on media,” “prophetic media methods,” and “how to effect social change.”Footnote 1 One prominent participant, Muhammad Qutb, Sayyid Qutb's younger brother, struck a discordant note by questioning the terms of the discussion: Islamic media, he argued, is not necessarily about Islam. Qutb criticized his colleagues for thinking unimaginatively about Islamic media. He worried that Islamists were becoming “like the communists, who made their media one extended lesson on Karl Marx.”Footnote 2

“Why is it that when we think of Islamic media [al-iʿlām al-Islāmī] we think of moral guidance and religious speech but nothing beyond that?” he asked attendees, a diverse mix of Azhari scholars, Islamist leaders, and Muslim-American academics.Footnote 3 “Nowadays when Muslim youth find religious programs on television or the radio, they switch [them] off. . . . This has become Islamic media, but why?” He continued: “The reason is that Islam in our imagination is not more than this. We do not live Islam in its fullness like the first generations did—we live Islam in narrow parameters. That is why when we think of Islamic media, we think of moral guidance and religious speech, because that is what Islam has become in our sensibility.”Footnote 4

Here, Qutb pivots the conversation about Islam and media from content to concept. What we need, he argued, is not more programs about Islam. What we need is to rediscover a deeper framework, at once ethical and epistemic, with no need to call attention to itself as Islamic. Instead of a “narrow” vision, Qutb asked his colleagues to take seriously the notion that media could be Islamic without a single Qur'anic verse quoted, prophetic saying narrated, or pious practice exhorted. Islamic media could be Islamic without being about Islam.

In my ethnographic fieldwork in Egypt almost four decades later at Iqraa, the world's first Islamic television channel, the question of what made media “Islamic” continued to be debated. Iqraa is a transnational satellite channel headquartered in Jeddah with an important production and administrative presence in Cairo. Shaykh Saleh Kamel (1940–2020), a prominent Saudi media mogul and billionaire businessman, established the channel in 1998. Broadcasting “culturally authentic” content that reflects “Islamic values” was a consistent theme in interviews Kamel gave about his media ventures, which run the gamut from music to sports to drama. From its inception, Iqraa branded itself as promoting a “centrist Islam” (Islām wasaṭī) as a bulwark against secular Westernization and religious dogmatism alike. By the start of my fieldwork in 2010, Iqraa had been broadcasting for over ten years, and Islamic idioms of publicity were unremarkable. For many, Islam had become a communicative “call” above all, and religion was already a routine component of the Arab world's everyday mass-mediated sights and sounds.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, efforts to disentangle Islamic media from the expressly religious continued. In an echo of Qutb, Iqraa's Saudi managing director explained this distinction: “We don't call Iqraa a religious channel but an Islamic channel, and there is an important difference between the two. Religious channels present purely religious programs—Qur'an, prophetic sayings, fatwas and so on—while Islamic channels present all types of programs as long as they are Islamically correct.”Footnote 6

This was not just managerial talk. The producers I worked with at Iqraa's Cairo branch aspired to make programs that would reconfigure what Islamic media sounded and looked like for their imagined audience of middle-class Muslims.Footnote 7 They tried to do this through music videos, celebrity talk shows, and reality television. From their perspective, such appropriations distinguish Iqraa as a visionary innovator in what became over the next two decades a crowded Islamic television field. Unlike other Islamic channels (and especially unlike dedicated Salafi channels, which it positioned as its main antagonists) Iqraa appreciated that Islamic media does not just mean religious programs whose purpose is to correct doctrinal understanding and enjoin ritual observance through citation of Qur'anic verses and prophetic praxis. And, unlike secular television, Iqraa understood that divine parameters of permissibility and prohibition were neither irrelevant nor indifferent to media creation.Footnote 8 But even as it was making Islamic media every day, the channel's concept of Islamic media remained unsettlingly uncertain.

One understanding of this instability is as a symptom of new media's broader fragmentation of religious authority in the Arab world.Footnote 9 Over the past thirty years the region's media landscape has dramatically transformed from a state monopoly on terrestrial television to a competitive satellite sector.Footnote 10 The emergence of privately funded Islamic television channels has been a much-commented-upon part of this shift. Scholars usually analyze these channels as a petrodollar story: dedicated Islamic channels are simply the result of Saudi Arabia's oil-boom-fueled domination of Pan-Arab satellite television. These accounts invariably focus on the political economy of the Islamic satellite sector as the key to unmasking the commercialized or politicized motives of its media producers and exposing their “invisible agenda.”Footnote 11 Similarly, Egyptian social discourses about Islamic satellite channels consistently depict them as evidence of an insidious religious colonization by an economically ascendant Saudi Arabia.Footnote 12

In this essay I offer a more multifaceted account of Iqraa's rise as the world's first Islamic television channel that takes seriously the role new ways of thinking about religion and media played alongside changing economic and regulatory structures. Petrodollars, although important, are not the whole story. Ideas matter too. From the mid-1960s onward, scholars across Arab countries dedicated their careers to theorizing the concept of Islamic media, giving it collective life through books, presentations, conferences, and newspaper columns. They established new departments, taught new students, and eventually helmed new media channels. It has been an effort at once impressive and puzzling. After all, media as a domain of social scientific research was already alive and well in the Arab academy by the early 1950s. Why not be satisfied with appending the adjective Islamic to media? Why go further to think about a specifically Qur'anic epistemology of media? Or, alternatively, why not stay within familiar jurisprudential discussions about the Islamic permission and prohibition of media content or technologies? More perplexing still was that this intellectual production took place in decades that witnessed the successive flourishing of self-consciously Islamic mass media in the Arab region, whether as print magazines, radio and television programs, or audiocassettes.Footnote 13 So why did it matter so much to go beyond the question of how to mediate Islam to what makes media, as a concept (mafhūm), Islamic?

I argue that the intellectual and institutional career of Islamic media as a category of knowledge was inextricably bound to aspirations for what I call epistemic emancipation. Epistemic emancipation hinged on understanding how media, iʿlām, was an Islamic concept despite being semantically absent from the Qur'an and the prophetic lexicon. The concept of Islamic media created by this effort reimagined modern disciplines and divine imperatives alike, unsettling the boundaries of the secular and the religious even while insisting on their mutual irreducibility.

Omnia el-Shakry has called for rethinking the dominant historiographical narratives of decolonization in the Middle East to include Islam-oriented intellectuals and activists. Maintaining that “we can no longer afford to think of decolonization as a purely secular affair,” she and other Arab intellectual historians have contested an assumed “incommensurable divide” between secular and religious thinkers by tracing their overlapping concerns with how modern knowledge could be harnessed to social reform and political resistance.Footnote 14 Contributing to this literature, I illuminate how Arab theorists of Islamic media aimed to dismantle a particularly insidious form of neocolonial power: the power to determine the very basis of knowing. As modern mass media became the necessary circulatory infrastructure of knowledge, making knowledge claims about mass media from within the conceptual resources of the Islamic tradition seemed important, even urgent. In contrast to the religiously reasoned objections of more conservative contemporaries, these scholars argued that modern media technologies were not just Islamically permissible or subject to divine proclamation but in fact a divinely dictated imperative akin to fasting or prayer and, in the opinion of some, even more consequential than these ritual pillars of Islam. These media scholars showed how a transparently modern category like media was nevertheless essential to Islamic tradition from its inception. In doing so, they troubled not only the certitudes of secular social science but also of Muslims who would simply use media to promote Islam, who would merely make Islamic media about Islam.

The history of how Islamic media became an epistemological object invested with so much power starts not in the neoliberal 1990s but the decolonial 1960s. Indeed, taking Islamic media seriously as a conceptual formation necessitates taking seriously the political, social, and economic hopes of its theorists for their countries after colonialism. To see how, in the first two sections I look at ʿAbd al-Latif Hamza, chair of Cairo University's journalism department in the 1950s and one of the Arab world's first professional media scholars. Hamza also was the first to argue that Islam was a “mediatic religion” (dīn iʿlāmī).Footnote 15 At its simplest, to pose Islam as a mediatic religion was to claim for it prototypical communicative prowess. At its most complex, the idea of a mediatic religion was part of a broader reimagination of the Qur'an as an exemplary media text and a suitable epistemic ground for theorizing modern mass communication. As we will see, the emergence of Islamic television involves scholars like Hamza who, although mostly overlooked in Western historiographies, were quite influential within the Arab academy. Indeed, Egyptians dominated this academic field initially. Some of them were, like Qutb, oppositional Islamists finding refuge in Saudi Arabia, where they significantly affected the kingdom's educational terrain.Footnote 16 But the most important exponents of Islamic media were Egyptians who spent most of their careers rising within the ranks of Egyptian universities. They were celebrated while alive as mass communication pioneers and after death had city streets named in their honor. For this founding generation of Arab media scholars, Islamic media's legibility was predicated less on adopting then-new mass media technologies like television and more on theorizing mediation as an ineluctable facet of Islam.Footnote 17

The next two sections examine how Hamza's junior colleague Ibrahim Imam scaled up such claims to make media production a divine imperative collectively incumbent on the Muslim community and knowledge of mass communication a constitutive part of Islamic faith. He did this through recourse to the methodological hallmark of Islamization: authentication, or ta'sil. Within this discursive formation, the Qur'an became a media text in the sense of both a historical exemplar of the best practices in mass communication and a criterial resource for evaluating future practices. I show how al-Azhar University's new mass communication department offered Imam an ideal platform for institutionalizing media studies across the region as a legitimate subfield of religious inquiry. From there, I trace how these intellectual networks around Islamic media played a direct role in the founding of Iqraa as the world's first Islamic satellite channel in 1998, focusing on the transnational academic career of the channel's inaugural Saudi director, ʿAbd al-Qadir Tash.

I conclude by considering how this intellectual history may provincialize Euro-American decolonizing projects that interrogate epistemic universalism in favor of pluralism.

“New Citizens for a New Society”

Mass communication matured as a social scientific discipline during the 1950s and 1960s. Its main concern then, and arguably now, was how to understand the link between media and social transformation.Footnote 18 In the Arab region, this assumed linkage was harnessed to the demands of decolonization. From Egypt's revolutionary Pan-Arabism to Saudi Arabia's monarchist Pan-Islamism, policymakers and scholars approached old media like newspapers and radio and new ones like television as powerful tools for cultivating the correct collective consciousness that they saw as the first step to overcoming the political, economic, and social challenges facing their developing countries.Footnote 19 Looking to media for its transformative potential resonated with a longer history of Arab intellectual engagement with communication that predated its disciplinary thematization. For example, Emilio Spadola shows that in interwar Morocco anti-colonial reformists saw “communicability, or consciousness of the force of mass communication, as a moral quality of modern national subjects.” For them, the key to social reform lay in the very awareness of the power of mass communication.Footnote 20 With decolonization, academics began to systematically investigate this power. And it was not just mass communication's local champions who saw it catalyzing the Arab world's postcolonial promise: leading Western communication scholars like Daniel Lerner, whose work on media-led modernization took the Middle East as its focus, made a strategic case for their new discipline as crucial to stymieing Soviet influence in newly independent Third World countries.Footnote 21 As we will see, however, Arab media scholars turned some of modernization theory's foundational assumptions on their heads while insisting that media was crucial to “social change” (al-taḥawwul al-ijtimāʿī), an incantation conjuring up everything from illiteracy alleviation to individual habits to international power.Footnote 22

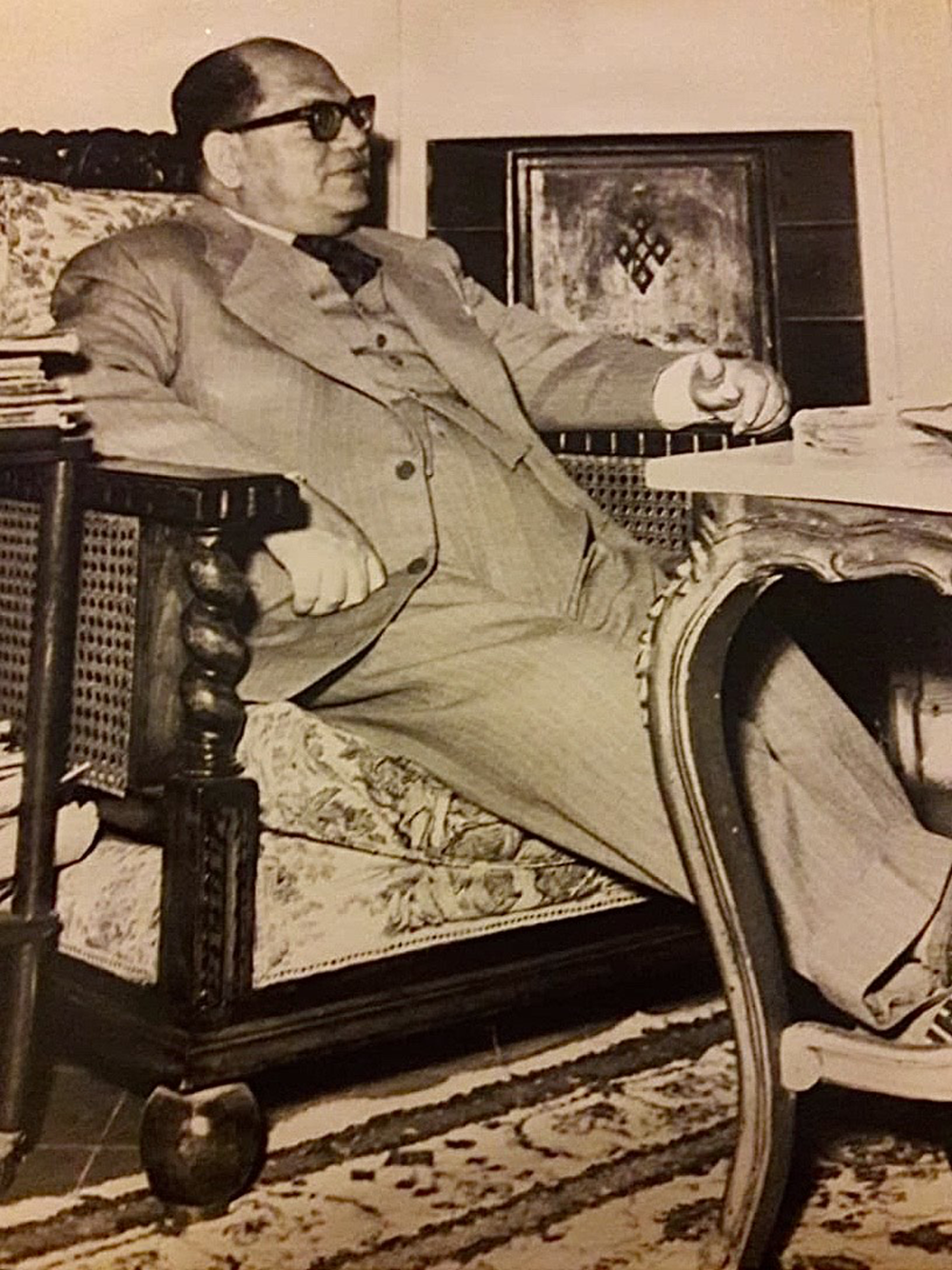

ʿAbd al-Latif Hamza (1907–1970) was the most prominent Arab academic of communication within this politicized media landscape (Fig. 1). Born in Upper Egypt, Hamza earned a doctorate in Arabic literature from Fuad I (later Cairo) University in 1939.Footnote 23 His career as a media scholar began in 1941 at the Institute for Journalism and Translation, established just a few years earlier at Fuad I and replaced after independence with the Arab world's first media department, of which Hamza became chair in 1956.Footnote 24 By then he was a leading Egyptian journalism scholar and keenly committed to showing how journalism, and later media more broadly, had deep conceptual and practical resonance with indigenous traditions, Islamic and Arab. For him, this is what would give the new discipline of mass communication resonance and durability.Footnote 25

Figure 1. ʿAbd al-Latif Hamza in his Cairo home. Courtesy of Kariman Hamza.

Hamza's chosen field was coming of age at a time of both concerted state investment in new broadcast infrastructure and increasing government control over media content. The long-invoked potential of media as a social catalyst became in the officially socialist Egypt of the 1960s justification for state ownership of all broadcast media. Two years after newspapers were “nationalized” (i.e., put under state control), the 1962 National Charter (al-Mithaq al-Watani ) did the same for newly established television channels. Mass media's long assumed refashioning powers for revolutionary nationalism were now harnessed in the service of the Mithaq's wide-ranging vision of a specific socialist transformation that went beyond the economic and political sphere to encompass education, culture, and even everyday habits. The success of tethering media to this transformation was predicated on its structural autonomy as a state-owned enterprise, free of “exploitative” commercial investment and the whims of advertising revenue. The “public ownership” of the “means of public guidance” is what gave media producers the freedom to create the “revolutionary” content that citizens should be consuming, irrespective of actual audience preferences.Footnote 26 And the field of media studies itself, like other university disciplines, must cultivate within its practitioners and students socialist dispositions. This involved asking, as Hamza did, “how can the press and other forms of media become socialist” and thus shape “new citizens for a new society?”Footnote 27

Hamza, like other academics during this period of heightened state interest in and regulation of knowledge production, had to navigate between critique and compliance. These were tricky waters. For example, Hamza echoed the Mithaq in lamenting that the press had “lost its way,” transformed from a lofty vocation, risāla, to a mere business, tijāra.Footnote 28 But he also wanted to reclaim the epistemic grounds of this assessment, writing in an ironic tone that “We university faculty were amazed at how the Mithaq could be such a deep study of the press and its problems. We were amazed because the department of journalism at Cairo University had spent many years studying these problems. The Mithaq is a precise summary of these studies.”Footnote 29 More directly, in his 1967 Qissat al-Sahafa al-‘Arabiyya (The Story of the Arab Press), written while on sabbatical at the University of Baghdad, Hamza called for media freedom from the control of both “capital” and “rulers.” He devoted a mere six lines to media developments in Egypt since 1952, demurring that not enough time had passed for historical analysis.Footnote 30

Throughout his career, however, Hamza explicitly argued that the scientific study of media was emancipatory on several levels. One level was institutional. Even before independence, Hamza lobbied for a stand-alone Faculty of Media (Kulliyat al-Iʿlām) at Cairo University.Footnote 31 This faculty was finally established in stages between 1969 and 1974, making it the first in the region.Footnote 32 Hamza also played an instrumental role in setting up media departments in other Arab countries, such as Iraq and Sudan. Paralleling developments on the ground, the teaching scope of these departments expanded beyond print journalism to include radio, television, public relations, and advertising, the cutting edge of communication science at the time. But the most significant level of emancipation lay in the production of original media scholarship. Hamza characterized the contemporary stage of Arab knowledge production as one of “intellectual adolescence” marked by dependency; Arab scholars and students took for granted the value of the West's knowledge and culture while “disregarding as worthless whatever comes from our own selves and our own environments.”Footnote 33 “Our epistemic dignity (karāmatnā al-‘ilmiyya),” Hamza argued, necessitated “that we rewrite our histories with our own pens from time to time.”Footnote 34

This motivation undergirded his 1965 al-Iʿlam la-hu Tarikhuhu wa Madhahibuhu (Media's History and Its Approaches). He introduced media as a category whose meaning was not always clear even in a “media age.”Footnote 35 The book claimed to clarify for the first time in Arabic “the scientific and philosophical principles” of media, positioning it as a “human science” with a distinctive methodology and object, similar to the more familiar fields of psychology and education. The stakes of getting mass communication right were high: far from a simple transmission of information from sender to receiver, media involved profound sociocultural transformation.Footnote 36 Like other Arab intellectuals of his time, Hamza was preoccupied with authenticity, aṣāla. Authenticity came to index a sovereignty yet to be achieved despite the formal political independence decolonization brought.Footnote 37 In this spirit, Hamza concluded with a section on media in Islamic history, planting the seeds of what would become the systematically elaborated premise of a whole new field of media studies. The Qur'an should be understood as media, as religious publicity, and Islam as nothing less than a mediatic religion (dīn iʿlāmī).Footnote 38 Media, a powerful source of emancipatory change, was authorized and prefigured by Islam.

Hamza's invocation of religion might at first glance seem discordant with the leftist ethos of the late Nasserist state. But from the beginning of the Mithaq-inaugurated “socialist revolution,” the interest of academics and public intellectuals in the mutual relevance of socialism and Islam was not discouraged. A 1967 select bibliography of Egyptian books on socialism published by the Ministry of Culture gives the heading “Islam and socialism” twenty-eight separate entries.Footnote 39 As one recent article on Arab socialism notes, “even at its height, the Arab left had to found its vision on religious grounds.”Footnote 40 Hamza's book is a good example of this: he prefaces the work as a “peaceful revolutionary socialist” and concludes with a meditation on the Qur'an and media. Although the 1960s may have been socialist, they were not necessarily secular.

“God's Newspaper”

Hamza's early writings on mass communication gave birth to the novel idea of media as central to religious doctrine and the possibility of religious experience. He reprised this argument in depth in his final book, al-Iʿlam fi Sadr al-Islam (Media at the Dawn of Islam), published a few months after his death in 1971.Footnote 41 Hamza had written a first draft while in Sudan, where he gave a series of well-received lectures on “propaganda and media at the time of the Prophet” at Omdurman University. Still, Hamza confessed that he was nervous about this attempt to think through the Islamic tradition from a “media angle” (zawiyya iʿlāmiyya), for it required deep knowledge of Islam and modern mass communication. But he also believed he was the only one who could plausibly lay claim to this dual expertise.Footnote 42

Hamza's book engaged two distinct streams of thought skeptical of an intrinsic link between Islam and media: Western mass communication research and Muslim religious conservatism. He saw the work as a long overdue challenge to “the conspiracy of silence” around Islam and media on the part of Western scholarship and a reclamation of “the dignity of the Arab scholar who shouldn't wait for European scholars to inaugurate this uncharted area of intellectual inquiry.”Footnote 43 Indeed, the little that Western mass communication research in Hamza's day had to say about Islam was negative. For leading media scholars like Daniel Lerner and his colleagues, Islam's ostensible religious determinism coupled with its suspicion of the “Western way of life” made “the Muslim Near East . . . an entity which will tend to resist communication from the outside.”Footnote 44 Within this familiar Orientalist trope of Muslim dogmatism is, nevertheless, a locally resonant observation: “To the Arab . . . economic and political conditions may be bad but there is nothing fundamentally wrong with Islamic precepts except perhaps that some Muslims do not conform to them.”Footnote 45 Indeed, media theorists like Hamza took for granted the transformational capacity of mass media while reading a different telos into radio waves and television signals, a future when Islam would be more relevant, not less. Like the totalizing frame of modernization theory itself but antagonistic to its secularizing ambition, Islam, properly understood, could make sense of everything, including mass media.

But conceiving the Qur'an as prototypical mass media and enshrining mediation as an essential feature of Islam was not a questionable endeavor only from the perspective of Western media theorists.Footnote 46 From the late 19th century onward, religious scholars have been ascertaining the Islamic permissibility of mass media technologies, from the telegraph to the radio. Religious objections were often overcome by showing how novel technologies could be used for long-standing religious ends. For example, the prominent turn of the century Islamic reformist Rashid Rida embraced the new media of his time as the material force of Islamic renewal. In a futuristic historical reasoning that continues today, Rida argued that the Prophet Muhammad would have used a phonograph to record his recitations of the Qur'an had one been available; as long as new media technologies served beneficial ends, their use was sanctioned by Islam.Footnote 47

Hamza, not above making this kind of instrumental argument, lauded other famous religious reformists like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad ʿAbduh for presciently recognizing media's potential to be a conduit of Islamic renewal and a weapon against colonial and missionary polemics.Footnote 48 But Hamza was proposing something more: to take Islamic media from content to concept. Indeed, he did not merely want to show that Islam accommodated the novel technological inventions of non-Muslims—he wanted to show that Islam prefigured the epistemic grounds of such inventions. This attempt resonates with the early 20th-century popular tradition of so-called scientific exegesis, which argued that “the Qur'an had anticipated the findings of everything from physics and astronomy to botany, zoology, and spiritualism.”Footnote 49 Rather than interpret the Qur'an in light of mass communication science, however, Hamza attempted to theorize media—and thus shape its still emerging social scientific study—in light of the Qur'an. In doing so, he reimagined the Qur'an itself.

In urging appreciation for the mediatic dimensions of the Islamic tradition, Hamza put forward a capacious definition of media and its technologies that was not limited to the modern inventions of the printing press, radio, television, or the cinema. In addition to the communicative formations of sermons, poetry, the bazaar, and even pilgrimage, divine revelation itself was a form of mass media. Hamza wrote about the Qur'an as “God's newspaper” (ṣaḥīfat Allāh).Footnote 50 Like the modern newspaper and other media with their assumed power to bring about social change, the Qur'an at its 7th-century revelation led to “revolutionary change” and “created a new society.” Indeed, Hamza argued, God obliged every prophet to convey his message, to mediate it, in the form most resonant with its intended addressees. Moses performed magical feats for a society that valued them; Jesus healed the sick at a time when people were plagued by disease; Muhammad's miracle was the Qur'an itself, which with its linguistic inimitability overwhelmed a society that esteemed poetic eloquence above all.Footnote 51 Four decades later at Iqraa, my interlocutors would invoke this analogy when reasoning about the new forms of Islamic media they aspired to create. For them, as for Hamza, the Qur'an was at once God's media text, his communication, and his meta commentary on human communication and its media forms. These interconnections were summed up in the pithy phrase al-dīn iʿlām, “religion is media,” which was bandied about in casual conversation and serious reflection alike during my fieldwork. The phrase creates what it purports to describe: an intrinsic link between religion and mediation. Paradoxically, as we will see, it also created an expectation of Islamic media as more than Islamic outreach, as more than da‘wa .

Conceptualizing the Qur'an as mass communication from God and Islam as a media religion quickly became a truism within Arabic-language media scholarship.Footnote 52 This premise instigated a systematic field of knowledge complete with its own inter-citational literature, journals, book series, collegial networks, standardized curricula, departments, even whole colleges. But Hamza's idiosyncratic ideas about how Islam and media made sense of each other might have died with him if it were not for the writers of the foreword and afterword to his book. They respectively contributed two key ingredients for intellectual longevity: a credentialing department and a methodology.

“The Qur'anic Logic of Media”

After his death, Hamza's daughter Kariman reviewed the proofs of al-Iʿlam fi Sadr al-Islam. In the process, she presciently decided to ask the media-savvy Azhari scholar ʿAbd al-Halim Mahmud to write the foreword. Mahmud was an early religious figure with a regular mass media presence, hosting his own daily radio talk show starting in the 1960s.Footnote 53 Kariman, who would have a media career of her own, first as head of Egyptian state television's religious programming and later at private satellite channels like Iqraa, felt that an endorsement from this high-profile figure would increase the impact of her father's book and mollify potential religious skeptics.Footnote 54 In his contribution, Mahmud praised Hamza for being the first to approach Islamic media, a phrase he put in quotational brackets. He echoed the book's call for the Arab academy to make the “history of media and publicity in Islam” a research priority. Mahmud did so two years later, in 1973, when he became the rector of al-Azhar. Under his watch, al-Azhar expanded greatly, partly funded through Mahmud's monetary appeals to Gulf kingdoms. He cast his institution as at the forefront of the regional struggle against unbelief and communism.Footnote 55 This expansion included the creation of a department of mass communication in 1974. Whereas Nasser may have seen the modernization of al-Azhar through the incorporation of modern disciplines as a dilution of its religious power, for reformists at al-Azhar itself these changes actualized a “reunion of religion (dīn) and life (dunyā)” against their lamentable secular separation.Footnote 56

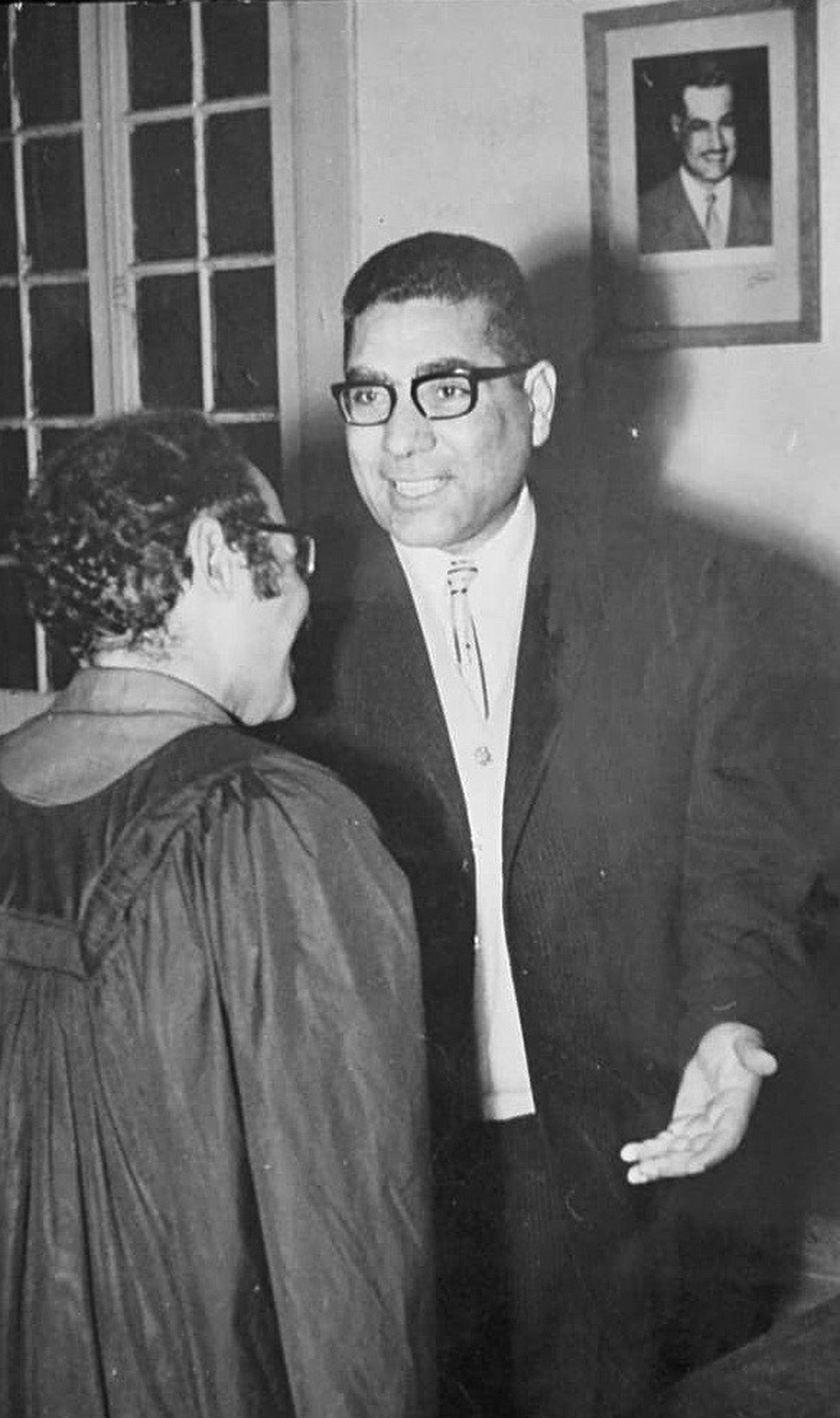

To lead the new department, Mahmud turned to the author of the afterword to Hamza's book, Ibrahim Imam (d. 2000). Hamza's junior colleague at the journalism department, Imam was already a leading Arab communications scholar. Like Hamza, he built institutions, setting up media departments in Libya, Iraq, and Sudan, and published some of the first Arabic books on mass media. For example, his 1957 al-‘Alaqat al-‘Amma wa-l Mujtama‘ (Public Relations and Society) introduced “an established field in American universities” to Arabic-language readers for the first time. For his journalism students at Cairo University, he offered the first seminar on public relations, which he framed, like media more broadly, as key to “societal balance and revolutionary progress.”Footnote 57 Imam's influence on media policy was so pervasive by the late 1960s that Egypt's first minister of information and national guidance, ‘Abd al-Qadir Hatim (d. 2015), reportedly referred to him as “Egypt's other [media] minister.”Footnote 58 Illustrating his stature, Imam became dean of Cairo University's Faculty of Media (Figs. 2 and 3).Footnote 59

Figure 2. Ibrahim Imam at a Cairo University dissertation defense. Courtesy of Tuhami Muntasir.

Figure 3. Imam lecturing at the Cairo UNESCO office. Courtesy of Tuhami Muntasir.

At the same time, Imam's growing interest in Islam as a terrain for theorizing mass communication earned him much derision from leftist colleagues. These tensions dramatically escalated in 1974 when Imam was fired after hitting his colleague Mukhtar al-Tahami with his shoe during a heated argument over socialism and media.Footnote 60 And although the power leftist doxa wielded over university life during the latter part of Nasser's rule waned with the greater visibility Sadat allowed Islamic idioms, as late as 1980 Imam was bemoaning “Soviet imperialism” over media studies in Egypt and advocating that the academic study of media should reflect a nation's values and concepts instead of “imported ideas.” This meant looking to Islamic tradition.Footnote 61

In 1976, Imam was invited, like Hamza before him, to lecture on Islamic media at Omdurman University. While in Sudan, he met the head of the Higher Institute for Islamic Propagation at Bin Saud University in Riyadh. The latter extended Imam a visiting professorship to guide institute students researching mass media.Footnote 62 Imam became a regular fixture at Saudi universities over the next thirty years. It was at al-Azhar University, however, that Imam would establish himself as the leading theoretician of Islamic media. As a newcomer, he faced pushback from faculty who did not care for the introduction of this new field into their religious domain and showed little respect for the professor or his students. One of these students remembers derision from other Azharis for “studying something religiously useless.”Footnote 63 Although such misoneism is commonly depicted as specific to Saudi Wahhabism, representatives of Egypt's mainstream Azhari tradition had their own doubts about the religious sanction of new technologies. These, like those of their Saudi counterparts, were often only assuaged by seeing media innovations serving religion.Footnote 64 For example, the objections of the minister of religious endowment to Egypt's adoption of television were mollified through assurance that established Azhari scholars “instead of those mosque preachers who sometimes present Islam incorrectly” would have their own programs for Qur'anic interpretation and that the daily calls to prayer would interrupt scheduled broadcasts.Footnote 65 Yet, like Hamza before him, Imam saw his mission less as broadcasting the Qur'an and more as theorizing modern mass communication concepts through a Qur'anic epistemology. And his demonstrations of how to do so went further than those of his mentor.

Imam's afterword to Hamza's final book, al-Iʿlam fi Sadr al-Islam, previews this methodological development. He frames the book as a laudable attempt to make media studies “relevant to the Islamic world, through the authentication (ta’ṣīl) of this new media culture.”Footnote 66 Recall that Hamza himself used aṣāla and not ta’ṣīl to describe the stakes of his book. The difference is important: authenticity, aṣāla, hinges on fidelity to cultural identity or historical traditions; authentication, ta’ṣīl, is more specifically concerned with epistemic warrant, with fidelity to the truths of revelation. As a methodology, authentication involves grounding concepts within the Qur'an and the sunna. In this case, authentication excavated the divinely disclosed parameters of specific modern media forms, and, more broadly, of mass communication as a discipline.Footnote 67 In contrast to Hamza, Islamic media was, for Imam, less a question of historical precedent and more a question of theory, of interrelated concepts with explanatory prowess. And, shoe-throwing notwithstanding, Imam positioned not secular leftists as most in need of convincing, but other religious Muslims who, precisely because they took the Qur'an seriously, might not take this intellectual effort as seriously as they should. For how can media, iʿlām, be authenticated as Islamic when the category by name is absent from the Qur'anic text? Imam and scholars that followed in his footsteps expected that the average reader would be skeptical about what “media has to do with Islam and what Islam has do with media.” After all, Imam conceded, Islam predated modern mass media. Would not the concepts of this new field of study be an assault, a hostile takeover (iqtiḥām) of Islam?Footnote 68 To the contrary: not only is Islam an intrinsically mediatizing religion but mass mediation also is a religious imperative, a farḍ dīnī, “made incumbent on Muslims by God and no less important than other ritual obligations such as fasting and alms-giving. . . . This [media] responsibility is what distinguishes the Muslim community from all others.”Footnote 69 It follows that divine revelation is an apt epistemic terrain for mass communication studies. Authentication required a methodological focus on discerning the Qur'anic logic (al-manṭiq al-Qu'ranī) of media and the media logic (al-manṭiq al-iʿlāmī) of the Qur'an.Footnote 70

Under Imam's leadership the media department at al-Azhar became the epicenter for the credentialing of a new generation of Arab mass communication scholars trained specifically as specialists in Islamic media. A 1978 UNESCO report on the state of mass communication teaching in the Arab world noted a “recent trend to connect mass communication studies and Islamic studies,” including at educational institutions not specifically concerned with religion.Footnote 71 It also cited al-Azhar's department and the Higher Institute for Islamic Propagation at Bin Saud, which in 1984 became the College of Daʿwa and Media, instituting a two-year certificate in Islamic mass communication, while al-Azhar offered a course called Mass Communication Theories in Islam. The report notes, however, that there was a shortage of PhDs to teach these courses, with departments relying on in-training MA students. Indeed, Imam ran al-Azhar's new media department as a one-man operation in the first years, teaching all courses himself. Al-Azhar did not have its own broadcast equipment, so for hands-on experience Imam used his networks to secure internships for his students at state television and radio.Footnote 72 As in other disciplines, these Egyptian graduates were in demand as faculty instructors across the region and were regularly called upon to consult with television broadcasters in the Gulf.Footnote 73 For example, Muhyi al-Din ‘Abd al-Halim chaired al-Azhar's media department from the mid- to late 1980s after a stint as a visiting professor in Saudi Arabia. His book al-Iʿlam al-Islami wa Tatbiqatuhu al-ʿAmaliyya (Islamic Media and Its Practical Application), published in Cairo and Riyadh, was for many years the standard textbook for Islamic media departments, superseding even Imam's books.Footnote 74 Imam himself held several visiting appointments in the Saudi academy and taught there full time by the 1990s. Far from being a simple petrodollar story of Saudi hegemony, then, the idea of Islamic media, and with it of a specifically Islamic television, was born at this nexus of decolonial social science, regional flows of intellectual capital, and a changing political economy.

“Beyond Religious Discourse”

By the 1990s, twenty years after Hamza's pioneering foray, Islamic media was an established subfield of mass communication and mass communication a subfield of Islamic studies. A 1993 bibliography lists 136 books and 242 master's and doctoral dissertations deposited in Egypt and Saudi Arabia on Islamic media.Footnote 75 Titles ranged from the general (al-I'lam fi al-Qur'an [Media in the Qur'an]) to the specific (Usul al-Iʿlam al-Islami wa Ususuhu: Dirasa Tahliliya li Nusus al-Akhbar fi Surat al-An'am [The Principles and Foundations of Islamic Media: An Analysis of Informational Verses in the Sixth Chapter of the Qur'an]).Footnote 76 These and other books framed the Qur'an as a media text in interrelated ways. One was a broad positing of the Qur'an as media content in the sense of being “God's message to humanity” and an inerrant historical chronicle of important events. This content was transmitted in the best possible way, with the Qur'an itself avowing its exemplarity: “And We have certainly presented for the people in this Qur'an from every [kind of] example, that they might remember.”Footnote 77 More specifically, the Qur'an laid out ideal media practice, offering a meta commentary on the essential ethics, attributes, and strategies for compelling communication, including in this modern age. In addition, the temporality of the Qur'anic revelation demonstrated mastery of effective media presentation: it was not revealed in a single occurrence but over time in a strategic order attuned to the dynamics of human psychology and sociological change.

Specific examples aside, the dual aspiration to show “the concern of Islam with media from the moment of revelation” and “how the foundations of contemporary media practices can be traced back to the Qur'an” united this body of work.Footnote 78 Beyond that, much remained unsettled. Could impious Muslims or even non-Muslims create media that was nevertheless Islamic? Or did Islamic media have to be created by morally upright “committed” Muslims? If so, what hands-on competencies in media work should such Muslims have mastered? The questions that provoked the most debate, however, centered on content: Is Islamic media synonymous with religious or daʿwa media, with moral exhortation? Or can any media content—sports, entertainment, news programs—be Islamic, and, if so, what made it so? This was precisely the issue Muhammad Qutb zeroed in on as particularly vexing at the 1976 Riyadh conference. Qutb argued that “we have to think beyond religious discourse—that will always be a part of Islamic media, but it cannot be the only thing.” He gave this example: “The newsreel has to be Islamic . . . but I know the question now is how can the newsreel be Islamic? You can say ‘in the name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful’ at the beginning of the newsreel, but that is not what will make it Islamic.”Footnote 79

The intervening decades of scholarship did not settle such questions, partly because of continuing religiously reasoned skepticism about modern media technologies. The sustained intellectual output around the idea of Islamic media that I have been charting contrasted with the recurring arguments of some scholars and preachers in Saudi Arabia and Egypt that different modern media were religiously prohibited, were antithetical to piety.Footnote 80 But a second obstacle came from the insistence on authentication that characterized Islamic media studies. In approaching the Qur'an as data and a theoretical framework for making sense of data, ta’ṣīl aimed for the scientific systematization of the emerging science of mass communication itself. The main way media scholars authenticated their object of study (which is not mentioned at all in the Qur'an) as Islamic was by making it analogous to daʿwa, which the Qur'an mentions by name numerous times. They did this all the while insisting that Islamic media definitionally exceeds daʿwa, exceeds the exhortation to the Islamic. But the authenticating analogy to daʿwa naturally became tied to the practical imperative of making mass communication a central part of the pedagogical formation of sermonizers and preachers. Indeed, the overriding goal of al-Azhar's media department was graduating media professionals well-versed in religion. In contrast to the more or less secular humanities background of the first Islamic media theorists, the authors of new books in the field were more likely to be professors of daʿwa, such as the Egyptian Ahmad Ghalwash, who served as dean of the Faculty of Islamic Daʿwa at al-Azhar and a professor of daʿwa at the University of Umm al-Qura in Mecca. As the conceptual and institutional link to daʿwa strengthened, the original insight that Islamic media definitionally exceeds the exhortation to the Islamic became more contentious, or at least harder to appreciate. The establishment of Iqraa as the world's first self-declared Islamic television did little to settle the question.

“Do We Need an Islamic Satellite Channel?”

During the decades that Saudi Arabia was hiring Egyptian professors to teach mass communication, it also was financially supporting Saudis pursuing doctorates in this field at American universities.Footnote 81 As these students returned home, Islamic media's intellectual center of gravity began shifting from Egypt to Saudi Arabia. ‘Abd al-Qadir Tash (1951–2004), the founding director of Iqraa, was one of those students. After obtaining a doctorate from the Southern Illinois University–Carbondale in 1983, Tash returned to Saudi Arabia to chair the department of mass communication at Bin Saud University.

Lauded as a national pioneer of Islamic media studies, Tash's academic and public writing posed questions of cultural change, media dependency, and asymmetries in knowledge production between Muslim countries and the West.Footnote 82 In tackling these themes, Tash drew on influential Egyptian Islamic thinkers like the Qutb brothers, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, and Muhammad al-Ghazali as well as the Islamization of knowledge movement which took off in the late 1970s. He also referenced Third World–ist critiques that current media flows enabled a Euro-American cultural imperialism masquerading as globalization.Footnote 83 In tandem with structural critiques, a new generation of media scholars in the West focused on “de-provincializing” the field by unpacking how this imperialism operated not just on the level of media content and economies but also on the theoretical apparatus of media studies.Footnote 84 At Carbondale during Tash's graduate years this concern focused on inter-cultural communication, the subject of a required seminar taught by K. S. Sitaram. Sitaram, who hailed from India, served on Tash's dissertation committee and shared his student's concerns about the unacknowledged ethnocentrism of communication studies (Fig. 4).Footnote 85 Tash thus would have encountered in his graduate training the same questioning of the universality of Western media concepts, standards, and practices that had animated pioneering Arab media scholars like Hamza and Imam much earlier. But unlike for their Western colleagues, the stakes of such questioning went well beyond the intellectual: these Arab scholars were firsthand witnesses to political decolonization and aimed from the start to make media studies relevant to this process. For them, media reflected the many problems facing the postcolonial Middle East, from loss of geopolitical power to cultural marginalization to intellectual stagnation. In addition, media made visible fundamental Muslim-Western differences and the overwhelming power of the West to erase, through the export of its media content, those differences in its favor. At the same time media, with its capacity for connectivity across time and space and potential for individual and collective reform, offered a way out of these predicaments. Media was at once peril and promise.

Figure 4. ʿAbd al-Qadir Tash and his adviser at his doctoral ceremony at Southern Illinois–Carbondale. Courtesy of Sharon Murphy.

Tash inherited this legacy and the sense of urgency that accompanied it within the context of newly accessible satellite technology, which heightened both media's threat and potential. Asking, “Do we need an Islamic satellite channel?” he identified his as a “satellite age,” when most powers, including Arab governments, used transnational television broadcasting to express their identities and realize their interests.Footnote 86 He explained that establishing an Islamic channel was important because Muslims were increasingly “confused” by the struggles among different groups in their countries. On the one hand, there were the secularists who promoted Westernization and eschewed Islam as a distinctive ethical and theological framework. On the other hand, there were those claiming to act in the name of Islam while purveying religious extremism and obscurantism. An Islamic satellite channel would protect ordinary Muslims against these trends by “promoting the spirit of true religiosity that is built on moderation in belief and conduct,” defined by a flexible responsiveness to, as opposed to fanatical rejection of, modern circumstances and culture.Footnote 87 The absence of an explicitly Islamic satellite channel was glaring, Tash matter-of-factly pointed out, considering that media-making was a veritable pillar of Islam, its creation a divinely mandated obligation of the Muslim community.Footnote 88 And just like media theory could be liberal or Marxist, an Islamic theory of media was possible. Tash argued passionately for the necessity of a specifically Islamic media philosophy as “a general intellectual framework [for] determining the nature of media practice in terms of assumptions and ends.” And he was clear that Islamic media would always include but never be limited to religious media—Islamic media, just like liberal or leftist media, could be about anything.Footnote 89

Although intellectually ambitious, Tash also was pragmatic. He bemoaned the lack of interest of wealthy Muslims in investing in media, arguing that an Islamic satellite channel had to be carefully set up and financially sustainable to succeed long-term.Footnote 90 So two things were necessary: an epistemic emancipation and the financial capital to back it up. The first seemed easier than the second. Nevertheless, Tash, on a first-name basis with one of Saudi Arabia's most important media investors, Shaykh Saleh Kamel, participated in an annual conference Kamel sponsored to develop links between businessmen, media practitioners, and academics in the region. The conference focused on Islamizing media through development of an Islamic media ethics and jurisprudence. Called “Iqraa,” as Tash's envisioned Islamic channel also came to be named, the conference recalled that the first revealed word of the Qur'an was an exhortation to religious publicity: “Recite!” From Tash's perspective, Kamel embodied an ideal combination of financial and moral capital, a serious media player who also had cultivated a reputation of concern for Islamic parameters and keeping at bay the corrupting influences of Western media by presenting Islamically correct alternatives.Footnote 91 When Saleh established Iqraa, the television channel, in 1998 and put Tash in charge, the professor finally could practice ideas he and other Islamic media theorists had long advocated.

When setting up Iqraa, Kamel also turned to more senior Egyptian scholars. In 1994, Kamel asked Imam to recruit a Cairo team to work alongside Tash's Jeddah team and figure out what Iqraa's Islamic media would be. That this wasn't obvious is significant. Imam tapped a former student from al-Azhar's media department to bring together a group of stakeholders, including poets and pundits, men and women.Footnote 92 They expressed diverse aspirations during the many months of preparations about what should be broadcast on the world's first dedicated Islamic television channel, but one thing held constant: Islamic television should not, must not, be limited to being about Islam.

But the idea that Islamic media and Islam were only contingently related remained for many counterintuitive. Commenting three years after Iqraa's launch, Tash was frustrated that some wanted to limit its programming to religious preaching. “There is a fundamental difference between the concept of da`wa media and Islamic media.” Although the latter strives to conform to “Islamic conceptions of the universe, life and human existence,” it is not, unlike the former, necessarily about those conceptions. Noting the preponderance of talking-head religious programs six months after Iqraa's launch, Tash argued for a reduction of such programs in favor of more entertainment, social content, and participatory formats.Footnote 93

Tash got his wish posthumously with the broadcast of the “new preacher” ‘Amr Khaled's program Sunnaʿ al-Haya (Life Makers).Footnote 94 It was everything Iqraa's producers wanted: innovative in its interactive format, eliciting viewer participation on and off screen, and innovative in its content, educating viewers about grave issues like drug addiction and domestic violence and entertaining them with performances by “Islamic pop stars.” Khaled's program, which brought in more than 80 percent of the channel's advertising revenue during its 2004–2005 broadcast year, put Iqraa on the Arab world's media map. The preacher himself was put in charge of Cairo-based program development.Footnote 95 Although Khaled's tenure at Iqraa was brief, over the next twenty years a succession of newer new preachers joined the channel. During my fieldwork, much of the channel's production resources were directed to another one of Egypt's new preachers, Mustafa Husni, who continued long-standing efforts to reach new audiences through new forms of media. This attempt to retain Islamic probity while attaining broader appeal provoked secular cynicism and Salafi censure. The divergent critiques were animated by a shared anxiety about how the media broadcast by Iqraa unsettled its stability as an Islamic channel. The concern was mirrored in scholarly depictions of Iqraa and its Islamic broadcasting as symptomatic of an unseemly neoliberal “commodification” of religion.Footnote 96 But, as we have seen, far from being a self-evident category, the conceptual history of Islamic media has always been animated by internal debates about its scope. These debates are part of a decolonial story predating the neoliberal political and economic transformations that made privately funded Islamic television possible.

Conclusion: Whose Knowledge, Which Decolonization?

During fieldwork in Egypt, I affiliated with Cairo University's Faculty of Media. The dean of the faculty was candid, criticizing state media coverage of the blatantly rigged 2010 parliamentary elections. Remaining cordial, he also bluntly dismissed my chosen topic of Islamic television channels with an impatient wave of his hand. “Those channels are all the same,” he said. “Just a bunch of shaykhs talking about the same things over and over. They have made religion a business while not contributing anything interesting from a media perspective.” He rehashed the familiar framing of the Islamic satellite television sector as a Wahhabi “cultural invasion” (ghazw thaqāfī) fueled by Saudi petrodollars. At the time, I did not know of the influential role his predecessors at Cairo University had played in making the Islamic channels he derided possible. I suspect he did not either.

The dean's inattention to the intellectual history of Arab media studies and its formative intersections with Islam is the norm, not the exception.Footnote 97 Indeed, whereas Islamic media as content attracts academic notice disproportionate to the diversity of media Arabs produce and consume, Islamic media as concept is barely on the academic radar in Middle East studies.Footnote 98 Even historiographers of Arab media overlook the history I chart here. For some, “the history of communication studies in the Arab world is more about institutional evolution than intellectual development,” with scholars from the region making “no genuine intellectual contributions.”Footnote 99 In another telling, “the Arab academe and its intellectuals have been very slow (almost stubborn) in realizing the centrality of media to experience in the modern Arab world.”Footnote 100 Such summary statements ignore the painstaking theoretical attention given to media and its relation to power and society by the Arab world's first communications scholars. As we have seen, successive generations of Arab media scholars viewed their intellectual work as a practice of epistemic emancipation. Their conceptual interventions and the involute reimagination of the religious and the secular that animated them are an important part of the region's decolonization struggles.

These Arab Islamic media scholars recognized early on the particularism of Western mass communication theory and sought to disrupt it through rethinking the very concept of media. Whereas provincializing in the Euro-American academy may renew its dominant categories “from and for the margins,” as Dipesh Chakrabarty put it, within the globally marginal Arab academy provincializing may lead us to rethink the very epistemic foundations of categories we take to be relatively straightforward or unproblematic.Footnote 101 Media is one of those categories. The decolonial may be another. In the global Western academy we often take decolonization to mean interrogating and decentering our dominant ways of knowing to open up possibilities for other, more inclusive, futures. Decolonization moves in this fashion from imperialistic universalism to a liberatory pluralism.Footnote 102 In contrast, for Islamic media theorists decolonization was predicated on cultivating not an open-ended epistemic diversity that celebrates the copresence of different ways of knowing, but rather on certainty in God's self-disclosure, however differently interpreted by humans.

The religious, Qur'an-oriented grounding of this attempt at epistemic emancipation has led some to denounce Islamic media scholarship as nothing more than a “divisive fundamentalism.”Footnote 103 It is, like the broader Islamization of knowledge movement with which it came to be associated, a symptom of an “Orientalism in reverse.” Just as there is no such thing as “Islamic art” or “Islamic economics,” but only art produced by Muslims and economies run by them, to take seriously “Islamic media” as a category of knowledge, versus merely as a consequence of practice, reifies Islam and nullifies Muslims—the essentialist and ahistorical hallmarks of Orientalism and fundamentalism alike.Footnote 104 From a different (and more sympathetic) perspective, the problem with a category like Islamic media is less essentialism and more imitation: it merely borrows from Western social science and does not radically challenge its standards.Footnote 105

But what if instead of lamenting the idea of Islamic media as either insufficiently secular or too much so, we remain attentive to how, for its theorists and practitioners, the power of the idea of Islamic media came at once from its grounding in the distinctive authoritative resources of Islam and from its recognizability as a species of mass communication science more broadly? To uphold mass mediation as a Qur'anic imperative, even if to then debate or contest the particulars, is to be in an affirmative, not indifferent, epistemic relationship to divinity; such a relationship does not foreclose critical inquiry into media but opens up a different calculus of its ends. These ends traverse the secular splits of the scientific from the theological and of social theory from ethical evaluation. This in turn entails a creative unsettling of both mass communication as secular discipline and Islam as religious tradition, even if the proponents of an Islamic media theory did not always see it this way. Put differently, when Islamic media theorists conceived mediation as a divine imperative and constitutive of Muslim belief—when they insisted in the face of secular and religious criticism alike that Islamic media was about more than Islam—they were radically reimagining the epistemic ambit of divine revelation as much as mass communication. In doing so, they conjured not only an alternative, more emancipated, future world but an otherwordly horizon to decolonization that provincializes the immanence of our own.

Acknowledgments

For their feedback on various oral versions of this article, I am grateful to colleagues at the American University of Beirut, the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan, and the 2019 annual meeting of the Middle East Studies Association. Tessa Farmer, Michael Lempert, and Aaron Rock-Singer helped me clarify my arguments and untangle my thinking. I also am thankful for the detailed critical feedback from the anonymous IJMES reviewers and editor Joel Gordon.