Introduction

Kurt Schneider (1887–1967) may be considered among the founders of precision research in the definition of psychiatric symptoms: ‘…Psychopathology has to continue trying to differentiate and to establish more certainly the vague and complex terminology that has gathered around psychotic symptoms. Only in this way will terminology grow more uniform and become more of a precision instrument than it has been up-to-date…’ (Schneider, p. 144). Schneider studied medicine in Berlin and Tubingen, and philosophy under Nicholas Hartmann and Max Scheler. In 1931 he became director of the German Psychiatric Research Institute in Munich, founded by Emil Kraepelin, and in 1946–1955 chair of the institute of psychiatry at Heidelberg (Cutting, Reference Cutting2015; Hoenig, Reference Hoenig1982). Karl Jaspers had an exceptional consideration of Schneider: ‘…I want to thank Professor Kurt Schneider of Munich. Not only has he stimulated me with penetrating criticism and valuable suggestions but he has greatly encouraged my work through his positive and exacting attitudes…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. xix).

The exactness and precision in symptoms definition is a key problem of medical semiotics since antiquity: ‘….if the sign (σημεῖον) is not apprehended with exactness, neither will it be said to be significant of anything, inasmuch as there is no agreement even about itself; and because of this it will not even be a sign…’ (Sextus Empiricus, 1933, p. 229).

The construct of schizophrenia is still only psychopathologically established, due to the failure of biological research to identify unequivocal biological indexes. Contemporary phenomenology research is aware of the centrality of psychiatry in the description of the experienced symptoms of schizophrenia, and of the absolute need to enhance the precision and exactness of their definition through the formulation of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (descriptive micro-psychopathology, Moscarelli, Reference Moscarelli2009).

This study examines a key ‘Schneider's FRS’ criterion (‘…schizophrenic symptoms of first-rank importance…Where they are unequivocally present they are always psychological primaries and irreducible…’ Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 136), formulated by Schneider in the context of psychiatric ‘phenomenology’, a specific chapter of psychopathology introduced by Jaspers: ‘…Phenomenology is the study which describes patients’ subjective experiences and everything else that exists or comes to be within the field of their awareness. These subjective data of experience are in contrast with other objective phenomena, obtained by methods of performance-testing, observation of the somatic state or assessment of what the patients’ expressions, actions and various productions may mean…’ (Jaspers, 1997, p. 53).

This conceptual investigation review will consider:

(i) Schneider's first-rank symptom (FRS) criterion, Schneider's first- and second-rank symptoms in the context of phenomenology, indicators of schizophrenia diagnosis.

(ii) Description in the classic psychiatry literature (Bleuler, Kraepelin, Jaspers, and Mayer Gross) of the symptoms targeted by the Schneider's FRS (in particular thought insertion, withdrawal, passivity, and influence).

(iii) Process of international adoption of the ‘Schneider's FRS’ [PSE, International Pilot Study on Schizophrenia, Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), DSM, and ICD], recent elimination in DSM-5 and de-emphasis in ICD-11, verification of the correct compliance with the ‘Schneider's FRS’ criterion since the initial ‘Schneider's FRS’ adoption by the PSE.

International readers of this paper are likely to be familiar with current diagnostic tools. They might be less familiar with historical nosology or definitions of psychopathology concepts, and their psychiatry training may have not included ‘phenomenology’ as a specific chapter of psychopathology. The original text by Schneider, classic authors, and modern researchers will clarify the Schneider's FRS criterion and its phenomenology context.

First- and second-rank symptoms, indicators of the diagnosis of schizophrenia

Schneider put some abnormal ‘modes of experience’ in the first rank of importance because they have a ‘special value’ in helping us to determine the diagnosis of schizophrenia as distinct from nonpsychotic abnormality or from ‘cyclothymia’: ‘…The value of these symptoms is, therefore, only related to diagnosis; they have no particular contribution to make to the theory of schizophrenia, as Bleuler's basic and accessory symptoms have or the primary and secondary symptoms which he and other writers favor…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 133). The Schneider's FRS ‘…cannot be used for purposes of prognosis…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 142).

The Schneider's FRS include: ‘…audible thoughts, voices heard arguing, voices heard commenting on one's actions, the experience of influences playing on the body (somatic passivity experiences); thought withdrawal, and other interferences with thought; diffusion of thought, delusional perception and all feelings, impulses, (drives), and volitional acts that are experienced by the patient as the work or influence of others…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 134).

Schneider reported the difficulty of ‘presuming a common structure’ for the FRS. Some of them (e.g. thought withdrawal, passivity thinking, diffusion of thought, and all the passivity experiences, whether feeling, drive or volition may be involved) ‘…can certainly be regarded as a group which represent the “lowering” of the “barrier” between the self and the surrounding world…’. However, hallucinations and delusional perception ‘…cannot be brought into this group formally without resorting to speculative constructions…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p.134).

The Schneider's FRS have a ‘special value’ (p. 133), a ‘decisive weight’ (p. 135), and ‘must have an undisputed precedence’ (p. 135) in a diagnosis of schizophrenia: ‘… Schizophrenic symptoms of first rank importance have a decisive weight beyond all others in establishing a differential typology between schizophrenia and cyclothymia, and must have undisputed precedence when it comes to the allocation of the individual case…The symptoms of second rank importance will appear in both types … In cyclothymia, there seem at present to be no known symptoms of first rank importance…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 135).

The Schneider's FRS do not always have to be present for a diagnosis of schizophrenia: ‘...We are often forced to base our diagnosis on the symptoms of second-rank importance, occasionally and exceptionally on mere disorders of expression alone, provided these are relatively florid and numerous…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 135). The abnormalities of the expression: ‘…must take second place, since they are so largely a function of the interviewer's impressions and provide an easy source of [NoA: the interviewer's] subjective error…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 132).

The Schneider's concept of symptom and diagnosis in schizophrenia refers to the context of illnesses with not known somatic base and only psychopathologically established: ‘…What meaning can “symptom” have with these “endogenous psychoses”, i.e., those that have no demonstrable somatic base? …It would be wiser…to understand by “symptom” some generally characteristic constant feature of a purely psychopathological nature that can be structured into an existing state with a subsequent course. In this case the medical connotation of “symptom” is abandoned. A psychopathologic structure consisting of a “state” and “course” is not an illness [NoA: with a known somatic base] which can produce symptoms. Thought-withdrawal, for instance, is at bottom not a symptom of the purely psychopathologically conceived state of schizophrenia, but it is a factor frequently found and therefore a prominent feature of it…If I find thought-withdrawal in a psychosis of not known somatic base, there is only an agreed convention that I then call this psychosis a schizophrenia. It seems well worthwhile preserving this particular meaning of “symptom” (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, pp. 131–132). …let me repeat that cyclothymia and schizophrenia can only be distinguished as types in principle. In most individual cases, however, one can decide univocally for one type or the other. This is what we call diagnosis…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 143).

The Schneider's approach to diagnosis is not compatible with a process of ‘diagnosis reification’ (Frances, Reference Frances2016; Hyman, Reference Hyman2012).

Criterion of the Schneider's first-rank symptoms

The criterion of the Schneider's FRS is reported below:

…schizophrenic symptoms of first-rank importance…Where they are unequivocally present they are always psychological primaries and irreducible… (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 136).

This criterion appears consistent with two Jaspers' definitions of the term ‘primary’: ‘…Sometimes the term primary symptom is used simply to denote those elementary symptoms which, as alien interruptions, are particularly important for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. In this case, all psychic events that have not this elementary quality no matter where they come from are classed as secondary…’; and ‘…primary is what is immediate, what can no longer be reduced by understanding, for example the instincts. Secondary, then is what emerges from the primary in a way which we can understand and for which we can have empathy, for instance, the symbolization of a drive … Thus delusional experiences [NoA: Jaspers’ primary delusion proper] and hallucinations are primary but the delusional system in so far as it is a work of reason is secondary…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 584).

The two definitions above are not to be confused with a completely different meaning of ‘primary’: ‘…Primary is what has been directly caused by the disease process. Secondary, on the other hand is the outcome of an environmental situation, as it is understandably linked with the defect in question…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 584).

Delusions

Schneider divided the construct of delusions into two major forms: Schneider's FRS delusional perception and delusional notion, considered a second-rank symptom.

FRS delusional perception

The FRS delusional perception takes place when some abnormal significance, usually with self-reference, is attached to a perception that is not altered: it is not a disturbance of perception but a disturbance of thought (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, pp. 104–105). Schneider's delusional perception is a two-stage phenomenon (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 110; Jaspers, p. 99, note 1) and does not share the FRS criterion of something primary, psychologically irreducible.

Second-rank symptoms and delusional notions

The second-rank symptoms included other hallucinations (‘…but by no means all hallucinations are symptoms of first-rank importance…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 134), delusional notions, perplexity, depressed and elated moods, and experiences of flattening feeling. If only symptoms of this order are present ‘…diagnosis will have to depend wholly on the coherence of the total clinical picture…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 134).

Delusional notions: ‘… arise from the prepsychotic thoughts, feelings, and impulses of the deluded person…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 114).

The criterion of something primary, psychologically irreducible, cannot be applied to delusional notions (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 114).

By delusional notions Schneider means notions such as those of religious or political eminence, or of having special gifts, or of being persecuted or loved. These delusions ‘…cannot be picked out as sharply as “delusional perceptions” and are of far less significance for the diagnosis of schizophrenia…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 107). According to Schneider, ‘…Any psychosis may produce such delusional notions, but the distinction between these and ordinary notions, overvalued ideas, or compulsive thoughts is sometimes impossible to preserve. We cannot rely on the patient's imperviousness to proof nor on the apparent exaggeration, improbability or impossibility of the notion. A notion may be possible and yet be delusional…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959 p. 107). Schneider's second-rank delusional notions include those delusions that may be defined “bizarre” in contemporary literature: ‘…Certainly, one gains the impression that schizophrenic delusional notions are different in some way from nonpsychotic or other psychotic notions, however odd, alien and grotesque these latter may be, but no precise psychiatric concept has been yet formulated…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 115).

Schneider's FRS and Kraepelin, Bleuler, Mayer Gross, and Jaspers

Kraepelin, Bleuler, Mayer Gross, and Jaspers described the symptoms (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, passivity, and influence) subsequently considered among the Schneider's FRS. These symptoms were already described in the psychiatry literature of the nineteenth century (Kendler & Mishara, Reference Kendler and Mishara2019).

There is evidence of a substantial convergence between Schneider and these authors regarding the following specific issues: (i) elementary nature of these symptoms (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, passivity, and influence), (ii) special value of these symptoms for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and (iii) inclusion of these symptoms, in themselves, in psychopathology domains that are not the domains of delusions.

Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) examined these symptoms in the sections on ‘Influence on Thought’ (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, p. 12), and ‘Constraint of Thought’ (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, p. 22). Kraepelin reported: ‘…Still more characteristic of the disease which is here discussed seems to be the feeling of one's thoughts being influenced, which often occurs… (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, p. 12). … Their thinking is constrained, has been withdrawn from the dominion of their will by irresistible influences…thoughts arise in them which they feel as strange, as not belonging to themselves …their thoughts are withdrawn from them…’. (p. 22). In the Kraepelin's view, these peculiar ‘sensations’ of influence lead the patients to the ‘idea’ that witchcraft and charms are being practiced (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, p. 28). He described separately the ‘Ideas of Influence’: ‘…very often the delusion of influence through external agents is developed: [NoA: the patient reports] “in a natural body such things do not happen”…’ (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, pp. 28–29). The content of delusions offers in general few effective points for the differentiation of schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness, however: ‘…the delusion of physical, specially sexual, influence points with great probability, the idea of influence on thought and will almost certainly, to dementia praecox…’ (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989, p. 269).

Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) included ‘deprivation of thought’ and ‘thought pressure’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1951, p. 378) among the formal disturbances of association of schizophrenia. Thought deprivation (Kraepelin's ‘withdrawal of the thoughts’, the symptom perceived by the patient, externally observed as ‘blocking’) was considered by Bleuler of particular value in the diagnosis of schizophrenia: ‘…Among the formal disturbances of the mental stream the obstructions (deprivation of thought) are the most streaking and when they occur too readily or too often or become too general and too persistent, they are positively pathognomonic of schizophrenia…’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1951, p. 378). The Bleuler's formal disturbance of association ‘thought pressure’ includes symptoms that evidently indicate symptoms of thought insertion and influence (… The feeling of “thought pressure” ‘in which the patient has the feeling that hre has to think, where against his will “it” thinks within him, and where thoughts are incessantly “made” for him …' Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1951, pp. 377–378). The patient's attributions are separately reported: ‘…It is something quite common to find that the blocking is attributed to foreign influence…’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950, p. 34). The ‘accessory’ symptoms’ include the patient's delusional attributions (e.g. mysterious apparatus and magic) to explain what causes the patient ‘…every conceivable unbearable sensation…’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950, p. 118).

Wilhelm Mayer Gross (1889–1961) included the ‘passivity phenomena’ among the disturbances of volition, and considered them ‘very characteristic of schizophrenia’ (Mayer Gross et al., Reference Mayer-Gross, Slater and Roth1977, p. 270). In his description, the patient tells that his thoughts, feelings, speech, and action are not his own. His thoughts are put into his head by an outside influence; his emotions are artificially made; he is made to laugh, to cry, to remain mute, to utter nonsensical words or obscene phrases, to perform bizarre movements, or to act against his will. He clearly distinguishes the process of patient's interpretation: ‘…The patient may interpret the experience of passivity in a delusional manner by maintaining that he is influenced by hypnosis, guided by God, wireless waves, telepathy, or manipulated by certain persons or agencies…’ (Mayer Gross et al., Reference Mayer-Gross, Slater and Roth1977, p. 270). In his view, the single symptom is only significant if assessed against its background, past history, and all the circumstances and findings of the present, while ‘…Tables of diagnostic symptoms may contain only the rarer passivity phenomena or combination of those with thought disorder and hallucinations’ (Mayer-Gross, Slater, & Roth, Reference Mayer-Gross, Slater and Roth1977, p. 320).

Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) described these symptoms in the ‘phenomenology’ section of his Psychopathology (specifically, in the chapter: ‘Alteration in the Awareness of One's Own Performance’): ‘…It is extremely difficult to imagine what is the actual experience with these “made thoughts” (passivity thinking) and these “thought withdrawals”…Any mode of activity may acquire this sense of being “artificially made”. Not only thinking is affected, but walking, speaking and behaving. These are all phenomena that exhibit influences upon the will…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 123). These ‘…primary…elementary symptoms ...alien interruptions... are particularly important for the diagnosis of schizophrenia’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 584). These phenomena ‘…are not the same as those of which people complain who suffer from personality disorders and depression, who declare it is as if they themselves were no longer acting but have become mere automata. What we are discussing here is something radically different, an elementary experience of being actually influenced…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 123). Jaspers did not classify these phenomena in themselves among delusions, explicitly grounded by Jaspers on a process of thinking and judging: ‘…Delusion manifests itself in judgments; delusions can only arise in the process of thinking and judging…’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 95). It is noted that the Jaspers’ primary delusion proper (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 96), strictly grounded on Jaspers' primary delusional experience of meaning (‘… All primary experience of delusion is an experience of meaning…’, Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 103), is not related to these phenomena (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and passivity), is not endorsed by Schneider, and is not included in the Schneider's FRS.

Schneider's FRS criterion and the international literature

Present state examination (PSE) and Schneider's FRS

The PSE was aimed to produce a simple and reliable subclassification of chronic schizophrenia, consistent with a classifying instrument focusing on four typical symptoms: flatness of affect, poverty of speech, incoherence of speech, and coherently expressed delusions. The instrument included the following questions: ‘…whether there was any interference with his thoughts, whether he had experienced anything in the nature of hypnotism or telepathy, or electricity playing on his mind…’ (Wing, Reference Wing1961). Work on the fifth edition of the measure resulted in the first publication, concerned largely with the reliability of the PSE (Cooper, Reference Cooper, Pichot, Berner, Wolf and Thau1985; Wing, Birley, Cooper, Graham, & Isaacs, Reference Wing, Birley, Cooper, Graham and Isaacs1967). By the time the seventh and the eighth editions were produced, it had been adopted for use in the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia of the World Health Organisation, and in the US/UK Diagnostic Project (Cooper, Reference Cooper, Pichot, Berner, Wolf and Thau1985; Gurland et al., Reference Gurland, Fleiss, Cooper, Sharpe, Kendell and Roberts1970; Kendell et al., Reference Kendell, Cooper, Gourlay, Copeland, Sharpe and Gurland1971; WHO, 1973).

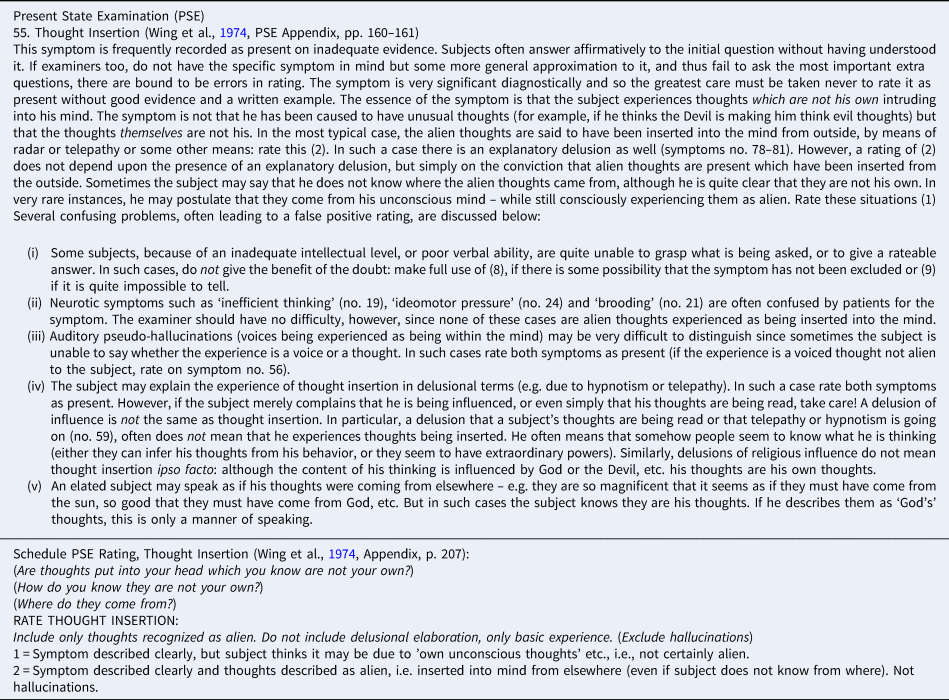

Schneider or Schneider's FRS were not mentioned in these initial articles (Wing, Reference Wing1961; Wing et al., Reference Wing, Birley, Cooper, Graham and Isaacs1967). To clarify with an example the relationship between: (i) original Schneider's FRS criterion and (ii) PSE symptoms construct, it is examined the definition and scoring of the symptom ‘thought insertion’ (PSE 9th edition, Wing et al., Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974, pp. 160–161, 207; Appendix Table A1).

The Schneider's FRS criterion (‘always psychological primaries and irreducible’, Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 136) is neglected by ANY description, definition or rating of this PSE symptom. On the contrary, the PSE definition is likely grounded on the patient's psychologically reducible process of thinking and judging, modulable in terms of: (1) simple postulation in terms of uncertainty, and (2) certainty and conviction. The core psychological reducibility of this PSE symptom appears consistent with the Schneider's definition of the second-rank delusional notions, that are neither psychologically primary nor irreducible (Schneider, p. 114). The symptom is reported as a ‘basic experience’ (Wing, Cooper, & Sartorius, Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974, p. 207), without further definition of the precise, intended concepts of ‘basic’ and of ‘experience’.

This 9th PSE version includes a unique mention of the Schneider's FRS: ‘… “delusions of control” and “thought insertion, etc.”….Both are first rank symptoms in Schneider's sense…’ (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974, p. 101). However, if these PSE symptoms are named FRS ‘in Schneider's sense’, they may be considered only homonymous of the original Schneider's FRS, because they have the name in common and a different definition (‘…When things have only a name in common and the definition of being which corresponds to the name is different, they are called homonymous…’, Aristotle, Reference Barnes1984, p. 3).

International pilot study on schizophrenia (IPSS)

The Schneider's diagnostic position was almost unknown in the USA before the 1970 (Carpenter, Strauss, & Bartko, Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Bartko1981, p. 951). The International Pilot Study on Schizophrenia (Colombia, Denmark, India, Nigeria, Russia, Czech Republic, Taiwan, UK, and USA, IPSS, WHO, 1973) employed the standardized interview schedule grounded on the PSE and modified for use in the ISPP (WHO, 1973).

Carpenter, Strauss, and Muleh (Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973) and Carpenter and Strauss (Reference Carpenter and Strauss1974) examined in the context of the IPSS: whether or not FRS are: (i) highly discriminating in the diagnosis of schizophrenia and (ii) absolute indicators of schizophrenia. The first direction, taken in the IPSS study, found: ‘…most FRSs are highly discriminating of either schizophrenia or paranoid psychosis…FRSs are strong diagnostic indicators, although they did not appear only in schizophrenia….’ (Carpenter, Strauss, & Muleh, Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973, p. 851). The second direction, found the FRS also in patients with other psychiatric diagnosis (e.g. 9 out of the 39 DSM-II manic-depressive patients). The authors concluded: ‘…while highly discriminating, leads to significant diagnostic errors if FRSs are regarded as pathognomonic…’ (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973, p. 847); ‘…the postulated hypothesis of the pathognomonic of the FRS is refuted…’ (Carpenter & Strauss, Reference Carpenter and Strauss1974, p. 687).

Wing replied that the view of Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973) and Carpenter and Strauss (Reference Carpenter and Strauss1974) was based on two linked assumptions, each of which can be questioned: ‘…. In the first place, they used no threshold point, so that a single rating of 1 on any of the items representing a first-rank symptom was regarded as necessarily indicative of a diagnosis of schizophrenia, whatever the rest of the symptomatology, and in spite of the fact that this would represent a “partial” delusion. It is unlikely in the extreme that any clinician (let alone Kurt Schneider who always emphasized the importance of whole clinical picture, including the previous history) would use so minimal a diagnostic criterion. Second, the authors assume that the clinical diagnosis, in the case of any discrepacy, must always to be “right” …’ (Wing & Nixon, Reference Wing and Nixon1975, p. 858).

The controversy clarifies incontrovertibly that the original Schneider's FRS (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and passivity) were equivocated by the PSE as ‘delusions’, and followed the PSE instructions for delusions: ‘…Most delusional symptoms are rated according to whether there is a partial or full conviction. Partial delusions are expressed with doubt, as a possibility which the subject is prepared to entertain but is not certain about…’ (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974, p. 167). The diagnostic threshold prescribed by Wing is not consistent with the compliance with the original Schneider's FRS criterion (“always psychologically primaries and irreducible”), criterion that passed unnoticed among the WHO–IPSS collaborating centers.

Diagnostic criteria and Schneider's FRS

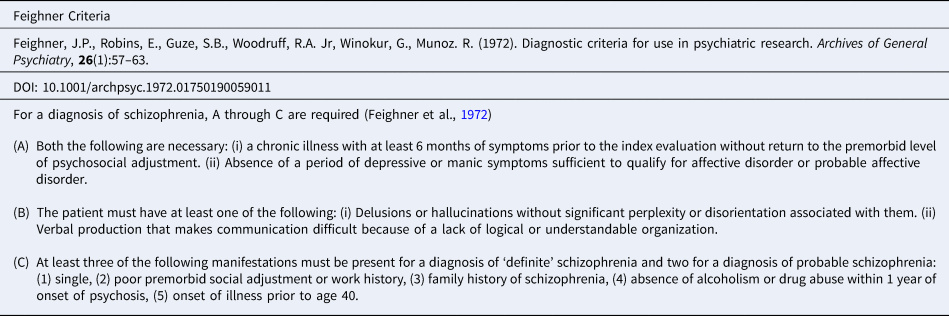

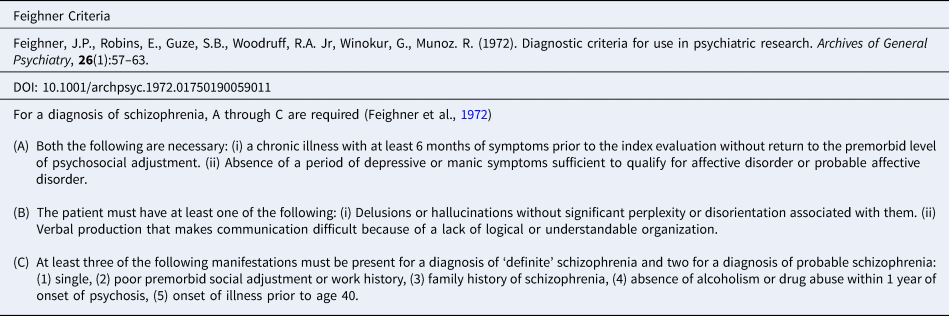

The Feighner diagnostic criteria (Feighner et al., Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz1972) were aimed to provide a framework for comparison of data gathered in different research centers. The criteria considered 14 psychiatric illnesses and certain diagnoses were mutually exclusive (e.g. primary affective disorders and schizophrenia). The Feighner diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (Appendix Table A2) required the following symptoms: ‘…The patient must have at least one of the following: (i) delusions or hallucinations without significant perplexity or disorientation associated with them, (ii) verbal production that makes communication difficult because of a lack of logical or understandable organization…’ (Feighner et al., Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz1972, p. 59).

Spitzer (Reference Spitzer1989) acknowledged that these criteria filled a void, since the DSM-II only contained general and often vague descriptions of the clinical features of the various mental disorders. In contrast, the Feighner criteria explicitly indicated which symptoms needed to be present to make the diagnosis, and, in many cases, which symptoms, if present, precluded making the diagnosis. Spitzer recalls that working on the previously published Feighner criteria, there was concern that these criteria contained the terms hallucinations and delusions without any further specification. Spitzer was particularly impressed by the evidence that Schneiderian symptoms could be assessed by the PSE with high reliability, and the Schneiderian FRS were adopted into RDC which then formed the basis of the symptomatic criteria for schizophrenia in DSM-III (Kendler, Reference Kendler2009).

The diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia was grounded on the following reasons: ‘…goals as the need to relate diagnosis to treatment and outcome, argued for restricting the diagnosis to individuals who at some time in their lives have been psychotic… by psychotic we mean either delusions, hallucinations, or gross disorganization of speech and behavior…’ (Spitzer, Andreasen, & Endicott, Reference Spitzer, Andreasen and Endicott1978a, pp. 490–491).

The Schneider's FRS were likely included in the diagnostic criteria because equivocated as delusions: ‘…Certain delusions appear to be very characteristic of this disorder. These include…thought insertion…thought withdrawal…delusions of being controlled or delusions of passivity…’ (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Andreasen and Endicott1978a, p. 496); ‘…given our current knowledge (ignorance?) some of the Schneider's First Rank Symptoms are useful in the diagnostic criteria….’ (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Andreasen and Endicott1978a, p. 492). In conclusion, diagnostic criteria ‘…relied heavily, but not exclusively, on the presence of the Schneiderian first-rank symptoms….’ (Spitzer, Endicott & Robins, Reference Spitzer, Endicott and Robins1978b, p. 776).

The RDC and the DSM-III did not notice the original Schneider's FRS criterion. Spitzer, Endicott, and Robins (Reference Spitzer, Endicott and Robins1975) identified the problem of ‘criterion variance’ only at the diagnostic level (considered responsible for the largest source of diagnostic unreliability), and examined inclusion and exclusion criteria only for psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., disagreement whether or not formal thought disorder is necessary for the diagnosis of schizophrenia). On the contrary, at symptom level, they neglected that the Schneider's FRS criterion excluded that the ‘Schneider's FRS’ (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and passivity) were delusions.

The equivocation of these Schneider's FRS as ‘delusions’ was communicated to the DSM-IV: ‘… Schneider identified a particular group of delusions and hallucinations that he considered to be of “first rank” significance in defining the disorder. These included thought insertion, thought withdrawal, thought broadcasting, voices communicating with or about the person, and delusions of being externally… controlled…’ (DSM-IV-TR Guidebook, 2004, p. 161), and subsequently to the DSM-5: ‘…Delusions that express a loss of control over mind or body are generally considered to be bizarre: these include the belief that one's thoughts have been “removed” by some outside force (thought withdrawal’), that alien thoughts have been put into one's mind (thought insertion), or that one's body or actions are being acted on or manipulated by some outside force (delusion of control)…’ (DSM-5, 2013, p. 87).

Elimination of a special treatment of Schneider's FRS in the DSM-5

Bizarre delusions and passivity symptoms were added in the RDC and in DSM-III, and dropped in DSM-5 (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016).

The rationale for the elimination of a special treatment of Schneiderian FRS (‘which overlap with the construct of bizarre delusions and “special” hallucinations’) in the DSM-5 included: (i) ‘…the diagnostic specificity of Schneiderian FRS for schizophrenia has long being questioned (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973)…’, (ii) lack of prognostic relevance of the FRS, and (iii) poor reliability of distinguishing bizarre from non-bizarre delusions (Tandon et al., Reference Tandon, Gaebel, Barch, Bustillo, Gur, Heckers and Carpenter2013).

The DSM-5 Psychosis Workgroup claimed that three major roots are reflected in all definitions of schizophrenia evolved through the DSM editions ‘… (a) Kraepelin emphasis on avolition, chronicity and poor outcome (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1989); (b) incorporation of the Bleulerian view that dissociative pathology is primary and fundamental and accent on negative symptoms (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950); and (c) Schneiderian stress on reality distortion or positive symptoms (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959)…’ (Tandon et al., Reference Tandon, Gaebel, Barch, Bustillo, Gur, Heckers and Carpenter2013).

Schneider's gave the FRS a special value as indicators of a diagnosis of schizophrenia, however with a clear caveat: ‘…. where unequivocally present…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 136).

The DSM-5's claim about the Schneiderian stress on ‘reality distortion’ or positive symptoms reveals an equivocation of the Schneider's FRS: ‘…The first rank symptoms can be viewed as ego boundary disturbances and this was considered the beginning of a subtle, but important, shift in the definition of schizophrenia from dissociative pathology to reality distortion symptoms… (i.e. delusion and hallucinations…)…’ (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2006); ‘…psychotic reality distortion symptoms, especially the Schneiderian first rank symptoms…’ (Keller, Fischer, & Carpenter, Reference Keller, Fischer and Carpenter2011); ‘… Did the endorsement of FRS shift the concept away from Kraepelin and Bleuler to reality distortion syndrome?…’ (Carpenter & Strauss, Reference Carpenter and Strauss2019).

Schneider, (i) never used the term ‘reality distortion’ to define the FRS (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and passivity), and (ii) never used the FRS to make a contribution to the theory of schizophrenia. Schneider would have considered doubly inappropriate a shift in definition from ‘dissociative pathology’ to ‘reality distortion’. The poor reliability in distinguishing bizarre from non-bizarre delusions is consistent with the Schneider's decision to include delusions (except than delusional perception) among the second-rank symptoms. Schneider claimed that the FRS were not to be used for purposes of prognosis.

There is evidence that the DSM-5 equivocated the Schneider's FRS as ‘reality distortion’, a mechanism grounded on the Bleuler's theory of symptoms, and not included in the Schneider's phenomenology. The mechanism of ‘Distortion of the Reality’ (‘Wirklichkeitsfälschungen’, Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950, p. 389; original publication 1911), was used by Bleuler in his ‘theory of symptoms’, focusing on: (i) delusions, (ii) sensory deceptions, and (iii) deceptions of memory. The Bleuler's ‘Genesis of the content of distortions of reality’ is aimed to explain this mechanism: ‘…Although of old, in isolated cases, some insight was gained into the mechanism of distortion of reality, we still owe it only to Freud that it has become possible to explain the special symptomatology of schizophrenia…’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950, p. 389). The subsequent Bleuler's Handbook of Psychiatry (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1951; original publication 1916) does not mention the ‘theory of symptoms’ and the ‘Distortion of the Reality’. We have reported above that symptoms that evidently indicate thought insertion and influence were instead included in the Bleuler's formal disturbance of association ‘thought pressure’ (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1951, p. 378).

The original Schneider's phenomenology and FRS may not be really considered among the roots of the DSM.

Soares-Weiser et al. (Reference Soares-Weiser, Maayan, Bergman, Davenport, Kirkham, Grabowski and Adams2015) examined the diagnostic accuracy of one or multiple Schneider's FRS for diagnosing schizophrenia, verified by clinical history and examination by a qualified professional. The analysis included 21 selected studies conducted from 1974 to 2011. The authors considered these studies of limited quality: study methods were not reported sufficiently and many had high applicability concerns. The FRS correctly identified schizophrenia 75–95% of the time, while the specialists did not agree with a diagnosis of schizophrenia for 5–19 people in every 100 who had FRS. This review did not control the compliance in these studies with the original Schneider's FRS criterion.

De-emphasis of the FRS in the ICD-11

The ICD-11 schizophrenia symptoms have remained largely unchanged from the ICD-10, though ‘…the importance of Schneiderian first-rank symptoms has been de-emphasized…’ (Reed et al., Reference Reed, First, Kogan, Hyman, Gureje, Gaebel and Saxena2019).

The ICD-11 reasons to de-emphasize the Schneider's FRS (Gaebel, Reference Gaebel2012) refer to the conclusion of the Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest, and Parnas (Reference Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest and Parnas2008) review: the diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms did not allow for either a reconfirmation or a rejection of the Schneider's FRS. Nordgaard et al. (Reference Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest and Parnas2008) noted the ‘...simplistic way in which the FRS were conceived in the operational diagnostic systems and in many of the commonly used rating scales…’ and considered essential a phenomenological approach for the assessment of the FRS. Until the status of the FRS is clarified in depth (‘…how we conceive the FRS, what is their phenomenological nature, and what method is adequate to assess their presence and diagnostic importance…’), '...we suggest that the FRS, as these are currently defined, should be de-emphasized in the next revisions of our diagnostic systems...' (Nordgaard et al., Reference Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest and Parnas2008).

We generally agree with these recommendations. However, it is not possible to agree with the following consideration: ‘…it is necessary to emphasize that the descriptions of FRS provided by Clinical Psychopathology are casual, vague, and do not live up to the rigorousness of “operational criteria” or “protocol statements”. This laconic form remained unchanged in the PSE…’ (Nordgaard et al., Reference Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest and Parnas2008). The criterion of the FRS reported by Schneider ‘…Where they are unequivocally present, they are always psychological primaries and irreducible…’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 136), criterion that cannot be applied to delusional notions (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 114) may be laconic, however it is neither casual nor vague, and it indicates a crucial construct of the "phenomenological" nature of the Schneider's FRS.

Conclusion

Edgar Allan Poe describes in the tale ‘The purloined letter’ the bafflement of the intellect to pass unnoticed what seems too palpably self-evident. A similar bafflement was described by Jaspers ‘…Theoretical prejudice…wherever we prejudge because of a theory, the appreciation of facts is curtailed. Findings are viewed from the angle of that particular theory; anything that supports it or seems relevant is found interesting; anything that has no relevance is ignored; anything that contradicts the theory is blackened or misinterpreted...’ (Jaspers, Reference Jaspers1974, p. 17).

Schneider defined the FRS, where unequivocally present, always psychological primaries, and irreducible. To our knowledge, this criterion passed unnoticed during the following decades internationally (e.g., Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2006; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, McGuffin, Mellor, Fuller Torrey, O'Grady, Geddes and Crow1996; Carpenter & Strauss, Reference Carpenter and Strauss1974, Reference Carpenter and Strauss2019; Carpenter, Strauss, & Bartko, Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Bartko1981; Carpenter, Strauss, & Muleh, Reference Carpenter, Strauss and Muleh1973; Crichton, Reference Crichton1996; Cutting, Reference Cutting2015; Heinz et al., Reference Heinz, Voss, Lawrie, Mishara, Bauer, Gallinat and Galderisi2016; Hoenig, Reference Hoenig1982, Reference Hoenig1983, Reference Hoenig1984; Jansson, Reference Jansson2018; Katschnig, Reference Katschnig2018; Keller, Fischer, & Carpenter, Reference Keller, Fischer and Carpenter2011; Koehler, Reference Koehler1979; Koehler & Seminario, Reference Koehler and Seminario1978; Koehler, Guth, & Grimm, Reference Koehler, Guth and Grimm1977; Mellor, Reference Mellor1970; Nordgaard et al., Reference Nordgaard, Arnfred, Handest and Parnas2007, Reference Nordgaard, Henriksen, Berge and Nilsson2019; Peralta & Cuesta, Reference Peralta and Cuesta1999; Picardi, Reference Picardi2019; Silverstein & Harrow, Reference Silverstein and Harrow1981; Taylor, Reference Taylor1972).

The Schneider's FRS criterion was not purloined and it is still available for the reader at p. 136 of the Schneider's Clinical Psychopathology. This criterion excludes delusional notions (Schneider, Reference Schneider1959, p. 114).

The equivocation of the ‘Schneider's FRS’ (e.g. thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and passivity) may rise a number of questions regarding the respective role of authorities and experts in the scientific progress (e.g. ‘Is the authority truly an expert? How truthful can we expect this expert be?’, Cialdini, Reference Cialdini2009, p. 196), and regarding the social expectations on the product of their contributions (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro1982).

Authorities and experts, over the decades, expressed enthusiastic support and fierce denial regarding the special value of the Schneider's FRS as indicators of the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the revision of the diagnostic systems. Consensus is critical for scientific progress (Salvador-Carulla et al., Reference Salvador-Carulla, Fernandez, Madden, Lukersmith, Colagiuri, Torkfar and Sturmberg2014, Reference Salvador-Carulla, Bertelli and Martinez-Leal2018). The neglect of the Schneider's FRS criterion, equally shared by the two parties, may have determined a pattern of ‘cyclic consensus’, characterized by inconclusive and recurring sparks of debate. The persisting equivocation of the key Schneider's FRS criterion may have compromised the development of a ‘spiral consensus’ (continuous increase in knowledge after a unification stage). The ‘damnatio memoriae’ of the original Schneider's FRS may be premature.

Conflict of interest

None.

Appendix