Introduction

The Cameroonian artist Alioum Moussa opened his solo show Fashion Victims in November 2011 at the Centre Culturel Franco-Nigerien Jean Rouch in Niamey, Niger. Developed during a residency at the Pistolleto Foundation (Biele, Italy) in 2010, it had first been shown in Douala, Cameroon, in early 2011. Growing from what was initially a smaller installation commenting wryly on Cameroonian conspicuous consumption, Moussa’s exhibition expanded its scope to become an incisive, yet compassionate, analysis of the global fashion industry that challenged viewers to see beyond the myopic consumerism pervading much of the world. As an identity-based ideology in which people’s purchasing capacity and choices are valued above all other attributes, consumerism obscures and attenuates the connections between production and consumption, capital and labor, and function and desire (Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001). The garments in Fashion Victims suggested the commonalities among consumerist phenomena in Cameroon, Niger, and Italy, but they also reflected the ways that consumerism shapes and perpetuates global disparities in power (see Bauman Reference Bauman1998). Moussa describes the processes of consumerism as “games of seduction,” and he invited viewers of his work to critically analyze their own consumerist practices by playing “games of history” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011) or creating shared responses to the globalized capitalist systems that shape our lives and link us to the past.Footnote 1

I viewed Fashion Victims in Niamey a few weeks after it opened. In this analysis, I argue that Moussa’s exhibition offered a complex humanist analysis of consumerism in the intersecting realms of art and fashion. I first address his exploration of branding in the commodification of both things and people in the global exchange of art and fashion. Next I examine Moussa’s re-use of secondhand clothes within the context of global contemporary art practices and fashion marketing trends. I then look at the specific kinds of fashion victims portrayed in the show along with Moussa’s critiques of dehumanizing consumerism. I conclude by suggesting that Fashion Victims, in its embrace of its own paradoxes, points to creative strategies that people, whether on the African continent or elsewhere, can adopt to counter the victimization threatened by what we wear.

In late 2011 Moussa had recently relocated to Niamey. Born in Maroua in the north of Cameroon in 1977, he traces his interest in art to his early childhood (personal communication, Feb. 24, 2014). It remained a passion throughout his years of formal education, which he completed with secondary school. In 2004 he joined other artists at Goddy Leye’s famous Art Bakery in Bonendale, Cameroon, which provided a vibrant community in which to develop work and to build networks (Babina et al. 2011; Leye et al. 2011). In 2006 Moussa joined the Art Bakery‒affiliated collective EXITOUR, whose members, led by Leye, traveled through seven countries in West Africa to learn about art in the region and to make their own.Footnote 2 The group visited Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Senegal. In Senegal they attended the Dak’Art Biennial. Moussa has completed several international residencies, including one in Basel, Switzerland in 2006, another in Denmark in 2013, and the one in Italy in 2010 at which he developed Fashion Victims. The experiences at Art Bakery were formative for Moussa, and he speaks warmly of Leye, who passed away shortly after writing about Fashion Victims in Douala (Leye Reference Leye2011), as a great friend and artist. Leye, too, was engaged with ideas about history, and wrote of creating decolonial “counter histories” (Leye Reference Leye2006).

Compared to Cameroon and most of its other neighbors in West Africa, Niger has fewer artists engaged in international contemporary art discourses. This is due to several circumstances. Comparatively fewer people attend formal schools in Niger, and even those who do rarely have the opportunity to study art (Gilvin Reference Gilvin2012, Reference Gilvin2014a, Reference Gilvin2014b; Bruns et al. Reference Bruns, Mingat and Rakotomalala2003; Hima Reference Hima2000). No university training is offered in the visual arts. Most artists seeking international markets identify themselves as artisans. Due to the advocacy and organizing led by the fashion designer Sidhamed “Alphadi” Seidnaly, Niger hosts one of the most important fashion festivals on the African continent, the 2011 edition of which coincided with Moussa’s exhibition. As in other African cities, a lively market supports numerous tailors, fashion designers, and others who make clothes on order for clients of all social classes (Grabski Reference Grabski2009; Mustafa Reference Mustafa2001). In Niamey, Fashion Victims found Nigerien and international audiences much more likely to have links to world fashion than to global contemporary art, even as the exhibit sought to intervene in both spheres.Footnote 3 Moussa’s commentary on fashion through contemporary art highlights the numerous ways that globalized high fashion and high art intersect, nurture, and challenge one another. While some artists, like Moussa, may criticize the fashion industry, they are well aware that fashion houses own contemporary art institutions (e.g., the Fondation Cartier Pour L’Art Contemporain and the Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton in Paris) and that contemporary artists design products for fashion houses. Art museums increasingly mount exhibitions on historic and contemporary fashion. This article adds to the growing scholarship analyzing the intersections between art and fashion.Footnote 4

Games of Seduction: Branding Fashion Victims

In one untitled piece in the Fashion Victims installation, a coat heavily reached toward the ground on its simple wire hanger next to the other garments (see figure 1). As the figure shows, the embellishments on the coat weigh it down with both mass and metaphor. One could imagine the coat in a former life, when it was an understated khaki women’s jacket with a quilted lining. Moussa’s hand embroidery alludes to the jacket’s history as a garment while simultaneously emptying it of a human body to temporarily isolate it from complex webs of exchange, travel, and use. The embroidery visually divides the jacket into distinct sections. On one side, a large letter “G” formed by a burgundy appliqué is framed by white hand embroidery suggestive of plant vines. A transparent pocket of tulle has been sewn on all four sides on top of the large pocket of the jacket. Along with transport tickets, a label for “Do Good Goods” is legible through the tulle. On the other pocket an embroidered arrow points away from the jacket, and on that side of the jacket compact embroidery blends with faux fur. A large swath of white tulle drapes from the collar where it is attached, and it offers uses as a playful cape or a wedding veil incongruously made a part of this warm coat.

Figure 1. Alioum Moussa, Untitled, 2010

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

In Niamey, a large-scale photograph of a model in the coat hung next to the coat itself (see figure 2). With her upturned gaze and outstretched arms, the model’s calm face seems beatific, but her robe is the same khaki jacket and a white tulle hood forms her halo. The sheer fabric, formerly a cast-off that as easily could have been part of a mosquito net as a dress, invokes diverse sartorial regimes of women’s modesty, as well as the current casual fashion trend of the hoodie. The photograph reiterates the valorization of the object inherent in its display as part of an art exhibition, its literal elevation from a pile of used clothing to a singular, precious artwork. Moussa’s photograph also picks up conventions from fashion photography, including the trope of the worn brick wall. This hints at the historic Italian industrial environment where this work took form, but also suggests that this jacket gains the kind of steady, though fleeting, attention that garments in a fashion magazine do. The photograph seduces the viewer, even as the jacket resists assimilation into viewers’ expectations of what fashionable haute couture, prêt-à-porter clothes, or fine art portraits look like.

Figure 2. Alioum Moussa, Untitled, 2010

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

Along with that khaki coat, Fashion Victims included numerous other secondhand garments Moussa found in Italy, Cameroon, and Niger, which he modified to various extents. He purchased a large bale of T-shirts at the Grand Marché in Niamey for materials especially for the Niamey show, and the numerous T-shirts neatly draped over windows and a circular stairway railing served to illustrate the sheer material abundance of secondhand garments that arrive all over Africa every day (see figure 3). He commented that “the clothes here . . . interest me because they come from different regions and different families, but they end up in one bale, one bale destined for the Grande Marché in Niamey” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). The title of the exhibition refers to the English slang term “fashion victim,” referring to someone who wears too many fads at once or otherwise tries too hard—or perhaps not hard enough—to meet current fashion trends, especially branding standards. Fashion Victims was inspired by Moussa’s observations of many young Cameroonians’ obsessions with European brand names. He noted the irony that while a Cameroonian’s Dolce & Gabbana shirt, whether new, secondhand, or counterfeit, authenticates the wearer’s identity as “in” in Cameroon, the shirt’s presence in Cameroon simultaneously represents the devaluation of the shirt and destabilizes the authenticity of the luxury brand (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011).

Figure 3. Alioum Moussa, Installation View of Fashion Victims, Centre Culturel Franco-Nigérien Jean Rouch, Niamey, Niger, 2011

Courtesy of the artist

Moussa addresses the relationship between the industrial and artisanal production of textiles by modifying industrially produced garments with hand techniques that refer to the significance of textile arts in his own history. As a young man Moussa hand embroidered garments on commission, especially for Muslim holidays like Tabaski (Eid al-Adha) and Eid al-Fitr. In his discussions of this body of work, he emphasized this long history of embroidering for different clients and audiences. His mother also embroidered, knit, wove, and sewed, and these hand techniques represent for him a “former time”: “Everybody uses machines, videos, the Internet. So me, I said, I need to embroider; I need to return to a former time” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). Moussa’s fascination with embroidery is also rooted in his observation of its association with luxury throughout West Africa (see Rovine Reference Rovine and Cooksey2011). Moussa’s interrogation of the handmade is not the nostalgia of the nineteenth century Arts and Crafts Movement, which idealized a preindustrialized past, for Moussa uses the remnants of industrial fashion production and use—secondhand clothing and excess thread from an Italian clothing factory—in his carefully handmade works. The embroidery asserts the links between the contemporary moment and history, portraying a temporality that is also flexible and adaptable. It emphasizes the past in a future-oriented world art market in which many artists (a significant portion of the “everybody” to whom Moussa referred) are innovating in digital media.

One of the first works a visitor encountered upon entering the show in Niamey was a short brown dress suspended from a large black frame over a mirror (see figure 4). Circles cut out from the large floppy tan collar had been appliquéd to the dress. If you approached the dress and looked down, you saw yourself in a mirror. You also could read some text written on a circular insert sewn to the bottom of the garment: “des copies made in china ou des Friperies ayant Transiter par l’Armée du Salut” (copies made in China or old clothes transported by the Salvation Army). These words express the stereotype (and partial reality) of African fashion and dress practices. Immense amounts of counterfeit branded clothing and secondhand garments arrive in Africa every day, and they are the cheapest and most convenient clothing options for many (Hanson Reference Hansen2000). Nigeriens and other Africans use these imports with much creativity, but as the art historian Suzanne Gott (2011), the anthropologist Karen Tranberg Hansen (Reference Hansen2000), and others have pointed out, the adoption and use of this clothing has been accelerated by economic factors that constricted Africans’ control over capital. As the World Bank and International Monetary Fund dictated programs of austerity in the 1980s and 1990s that devalued currencies, eliminated employment, and promoted mineral extraction, Africans turned to secondhand clothing out of duress.

Figure 4. Alioum Moussa, Untitled

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

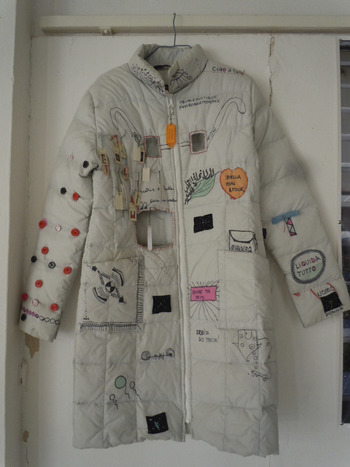

On another coat made during his residency in Italy, Moussa invited visitors and other artists to write, thus multiplying the hands involved in the reinvention of the coat (see figure 5). Specifically, he asked them to draw logos for imaginary brands, and then he attached small tags with these emblems to the coat, confounding the purpose of branding a commodity. The coat became Tommy Hilfiger, Wrangler, Puma, and others, all at the same time: it became many brands to many people. Individuals and societies must invest meaning in brands for the system to work. In the hypervaluation of objects through branding, and in the construction of selves through consumption, Moussa sees games of seduction. Companies often seduce their customers with images that depict sexual seduction. Customers then wait for the next advertising campaign to compel them to purchase new shirts and discard their old ones, turning former luxury items into disposable objects that will be donated to “charity.” Consumerism cultivates desires, and the actual consumption is a transient act that only momentarily forestalls further desires (see Bauman Reference Bauman2008).

Figure 5. Alioum Moussa, Untitled, 2010

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

The secondhand industry, which is perceived as charitable, is in this way actually a nebulous zone in which businesses profit by selling and recycling commodities that are valuable in one season and waste matter in the next.Footnote 5 These are games of seduction—the ways that industrial capitalism multiplies desires that can never be sated. Discussing the globalization of consumerism, the sociologist Zigmunt Bauman writes that “coercion is being replaced by stimulation, forceful imposition of behavioral patterns by seduction, policing of conduct by PR and advertising, and the normative regulation, as such, by the arousal of new needs and desires” (2008:50). Consumerism provides pleasures, and those experiences stimulate further desires, creating addictive cycles of purchasing (see also Storper Reference Storper, Comaroff and Comaroff2001). A company uses its brand to seduce customers to purchase clothing that can itself become a tool of seduction, and personal games of seduction rely on the acquisition of brand name clothing to convince others of one’s own desirability. Hearkening to anthropological theorists of exchange such as Igor Kopytoff (Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986), Moussa remarked that when a shirt finishes its life in Italy, it begins an entirely new life in Cameroon or elsewhere in Africa. Devalued on the global market, it serves with its new discounted price in new games of seduction until it is discarded again. This is the moment at which Moussa seeks to change the game:

Ultimately, it is a path that doesn’t end. When it [the shirt] finishes its value in Cameroon, in Africa, it is there that I create another value, one that is more ethical. It is no longer an aesthetic value. From these leftover pieces I make art objects that will enter museums and other cultural spaces. This visibility is something other than a game of seduction. It is no longer a game of seduction, but a game of history, this relationship between the clothing and us. All of us who wear clothing. (Personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011)

In this comment Moussa of course downplays the games of seduction at the core of art exhibition and sales—after all, cultural spaces are not immune to consumerism, and they are often constituted by consumerist practices. However, I understand Moussa’s call for a shift from a “game of seduction” to a “game of history” as a demand for self-reflexivity and critical analysis in a viewer’s engagement with both art and fashion, rather than a denial of consumerism in art or a singular condemnation of fashion. The importance of the notion of play derives partly from the near-homonyms in French of the words for “game” (jeu) and “I” (je). Moussa explained that “I am interested in jeu . . . because it is different from je, individual me, alone and selfish. Thus, jeu plays with something that is both a challenge and a pleasure. And one doesn’t play alone. For the game to be enjoyable, there must be several players. One shares the game and is not isolated” (personal communication, Feb. 24, 2014). The games of history being played in the exhibition were set up by Moussa’s conceptual interventions, his questions and stories about people and what they wear. Leye (Reference Leye2011) wrote of the incarnation of Fashion Victims in Douala,

In effect, it could be that the fashion victims of whom the artist speaks are only those who wear name brand (or supposedly name brand) clothing. Perhaps above all, he trains a laser-like focus on a society in which each member attends to their sartorial or material condition without taking care of the intellectual, economic, and philosophical foundations that truly constitute modernity.

In a Niamey buzzing with guests in town for FIMA, the exhibition’s critiques of multiple intersecting societies and networks became even clearer. The artworks made of clothes were metonymic pawns used to comment on the social issues addressed in the exhibition. These intellectual discourses and other actions that compose games of history do not efface the games of seduction in either art or fashion, but have the opposite effect, in that they call attention to them.

Like Hank Willis Thomas, the American artist whose Branded and UnBranded series call attention to the function of branding and consumer capitalism in African American culture, Moussa examines the effect of the valuation of brands on the bodies that wear them. Willis Thomas incisively portrays the psychological consequences of branding on the perception of black bodies. In his 2003 work Branded Head from the series Branded, he adds a Nike swoosh as a brand to a man’s head, evoking troubling conflated images of historic chattel slavery and contemporary consumer culture (see figure 6). In contrast, the body largely remains abstract in Fashion Victims, and it is the objects themselves that evoke the body’s relationship to them. Moussa reflects on the power of branding,

Here, it is also the irony of Dolce & Gabbana, because Dolce & Gabbana is the dream of all youth. To wear a Dolce & Gabbana belt, a Dolce & Gabbana shirt, Dolce & Gabbana glasses is to be chic, to seduce with them. And for me, how can one say that this is a poor country . . . when we use the same objects given to the rich. I say I am poor, and you, you are rich, and when you manufacture things, it is me that is your client. . . . [This] directly changes the question of poverty. Today, many say they will help Africa. . . . All the works that are sold, the earnings are intended to fight malaria—but the little poor person, with his malaria, he buys Dolce & Gabbana—or at least something that represents Dolce & Gabbana, even if he buys something made in China. (Personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011)

Figure 6. Hank Willis Thomas, Branded Head, 2003

Lambda photograph, courtesy of the artist and the Jack Shainman Gallery

A fundamental aspect of global industrial capitalism, philanthropy can obscure ongoing exploitative and unjust political and economic systems precisely by appearing to function outside of consumerism. Philanthropy is as much a tool of branding as it is a transaction between a giver and a receiver. Moussa “changes the question of poverty” by devictimizing Africans, who are frequently portrayed as disempowered, starving women and children in need of Western aid. In this, Moussa joins many other artists, activists, and politicians who defy longstanding stereotypes of an abject continent. This includes the aforementioned Nigerien fashion designer Alphadi, who promotes an Africa that is “on the move, an up and coming continent” (Sidhamed “Alphadi” Seidnaly, personal communication, Oct. 28, 2013; also see Gilvin Reference Gilvin2014c; Rovine Reference Rovine2010a). Conventional discourses of philanthropy lack a critical framework that accounts for the historical context out of which vast global inequalities in wealth have emerged—or the sheer vastness of consumerism around the world. They also obscure the contributions of those construed as victims, for recipients of charity, too, shape their worlds, and often they also seek the branded luxuries and pleasures with which an industrialized globe overflows.

Games of History: Reuse and Do Good Goods

In his reuse of garments as art objects, Moussa draws on diverse African and European dress and artistic practices. He explains that

for us [West Africans], we do not throw clothing away, even if it is old, because clothes translate the history of identity. We can see in clothing the personality of someone who has departed, and in the embroidery you see the class and social place of the person. . . . The grand boubou, for example, is very important. But we, the young, do not have the opportunity to inherit the clothing of our parents because there were others who were waiting for it. (Personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011).

Here Moussa demonstrates the central importance of dress in African visual cultures, a point that has been argued by a number of scholars.Footnote 6 Moussa’s embroidery alludes directly to the embroidery on men’s robes, variations on which exist across West Africa. In particular, the composition and motifs of the khaki coat (figure 1) refer to the aska takwas, or “Eight Knives,” design associated with Hausa embroiderers in Northern Nigeria, which can be found in both Cameroon and Niger (see figure 7). The coat’s asymmetrical design anchored in the burgundy appliqué of the letter “G” recalls the spiraling design on many Hausa robes. The latticework on this grand boubou is echoed in the embroidery on the coat’s sleeve and below its transparent pocket. The white botanical embroidery on the coat looks like what might happen if the designs on the grand boubou began to move, as if animated. The arrow on the coat refers to the knife motifs as well as the horizontal motifs that point to the center of this boubou. In the absence of inheriting the richly embroidered, handmade luxurious status symbols of his ancestors, Moussa evokes his inheritance in his appropriation of garments abandoned by the living. He links them to his past through the application of innovative embroidery of factories’ excess thread, which also connects Italian industry with West African artisanry. His raw materials convey shared histories and suggest individual identities. Rather than standing for a persistent claim on social status within a family and community, these garments represent broad shared commitments to fleeting fads and identities shaped through global brands. The scale of the importation of secondhand clothing to Africa from North America and Europe builds on economic relationships and philanthropic discourses rooted in the colonial era, and this, too, reflects identity formations: but those of whole continents, rather than individuals.

Figure 7. Hausa-Nupé, Babban Riga, cotton, embroidered with the aska takwas (eight knives) design

Photographer: Dieter Spinnler, © Museum der Kulturen, Basel, Switzerland

Diverse art traditions in Africa have long reused and repurposed objects. David Doris writes of the Yoruba protective sculptures ààlè that they are “objects transformed, even if only by the desires and at times minimal acts by which they are resituated as ààlè” (2011:17). Allen F. Roberts argues that the “distinctions between use and aesthetic value must be seen as contingent, hence as arbitrarily determined in some particular situation” (1992:55). Infused with the power of their histories and previous uses, objects can live second, third, and fourth lives as they are reinterpreted and reworked. Yet this frequent reinterpretation of objects has found equally frequent misapprehension in Western scholarship and popular media, from colonial portrayals of Africans’ supposed failure to understand the use of European commodities to contemporary romanticized marketing for commodities made from recycled goods in Africa. Focusing on those objects exported to the West, the anthropologist Corinne Kratz cautions that “beauty and ingenuity born out of squalor, the nobility of earnest endeavor—these are stories so familiar we should be wary of believing them” (1995:8). Whether in souvenirs in an airport shop or in a gallery at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, reuse in African creative practices often inspires generalized assumptions about meaning, which include a critique of consumerism, an ironic reuse of a familiar commodity, and a pitiable need to recycle. Yet the Africans reusing materials may intend neither critique nor irony, and they may even be choosing to forgo new materials in order to meet a market desire for recycled products in their tourist and export markets.

Victoria Rovine (Reference Rovine and McLean2015) argues that Western art critics and buyers are especially receptive to African artists working in reused media and textiles because the practice satisfies stereotypical assumptions about African art. The Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, for example, one of the primary examples that Rovine considers, has risen to global prominence with his large-scale sculptures made from foil liquor bottle caps attached with wire (see figure 8). But while the reuse and repurposing of media is indeed a prominent method in much contemporary African art, modern and contemporary art worldwide has also included many recycled and repurposed objects for generations. For example, the Chinese artist Xu Bing creates sculptures from cigarettes and construction materials, and the American artist Tara Donovan makes work from pencils, Styrofoam cups, and fishing line, among other materials (Tomii Reference Tomii2011; Donovan et al. 2008). Moussa’s practice refers not only to African traditions but also to traditions of récupération and bricolage developed by Surrealist and Dadaist artists; Christian Hanussek (Reference Hanussek2001) makes this point about the artist Goddy Leye in his discussion of récupération as a central concept and method used by artists in Cameroon’s “emerging art scene” in 2000. El Anatsui, for his part, takes care not to frame reuse and repurposing as specifically African art practices. On the subject of his own use of found objects, he states, “As an artist I think I should work with processes and media that are immediately around me. And in Africa, just like everywhere in the world . . . we create waste. . . . And as an artist, I . . . have always even advised my students to work with materials that you don’t have to spend anything . . .” (quoted in Stokes Sims & King Hammond Reference Stokes Sims and King Hammond2010:27). El Anatsui chooses media already infused with history and ripe for experimentation (Rovine Reference Rovine and McLean2015; Vogel Reference Vogel2012). He upends assumptions about material value as part of a conceptual art practice equally grounded in West African aesthetic histories and world modernist art historical narratives. When an association of African art with reuse is applied too generally and associated with a Western idealized understanding of recycling as an environmentalist gesture, it elides the critical engagement of contemporary African artists with global art history and the conceptual content of specific works in different repurposed media.

Figure 8. El Anatsui, Untitled, 2007

Foil and copper wire, courtesy of the artist and the Jack Shainman Gallery

African designers also have been at the forefront of the reuse of clothing for haute couture. For example, the fashion designer Lamine Badian Kouyaté introduced his brand Xuly Bët in Paris in 1989 when he inaugurated the Xuly Bët Funkin’ Fashion Factory. The Wolof phrase xuly bët is a multivalent term that means to look with understanding (Levin Reference Levin2005). Kouyaté has developed a distinctive style in which secondhand clothes are transformed into luxurious and hip ensembles that play with the grunge aesthetic that resonated throughout the 1990s in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. He explains that “in Africa, secondhand clothing is passage obligé for the people, it’s all they can afford. In the West we throw it all away, it’s too much waste, so I decided to do something with it. Fashion is itself a cycle, after all” (quoted in Jennings Reference Jennings2011:26). Much of Kouyaté’s work has showcased his method through the emphasis of its components’ former lives in other garments. In one example of his work from 1998 (see figure 9), disparate textures and patterns combine in a single garment, and the heavy, outward-facing seams make the patchwork that much more daring. A burly plaid flannel collar emerges from a slim red wrap sweater over a full skirt, knitted parts of which pool on the floor. Xuly Bët is a commercial, fashion, and conceptual project, and in this piece Kouyaté plays games of seduction and of history with graceful irony. Discarded sweaters have become precious couture garments in one of the most prestigious fashion centers, Paris. Kouyaté’s work was an early example of interest in sustainable fashion around the world, and this reinvention of clothes came to be known as “upcycling” in the 2000s (Black Reference Black2013; DuFault Reference DuFault2014).

Figure 9. Lamine Badian Kouyaté, Ensemble for Xuly Bët, 1994

Multicolor recycled wool and red nylon; courtesy of the designer and the Fashion Institute of Technology

Moussa is not the first conceptual artist to join fashion designers like Kouyaté in the transformation of garments. The American artist Shinique Smith has made secondhand clothing her signature medium since the early 2000s, although she combines it with painting and other media in her sculptures and installations (Pinder Reference Pinder2008). Reading about the bales of secondhand clothing exported to Africa first inspired her to turn to the material, and she considers her Bale Variant series a response to specifically American modes of consumption (Sheets Reference Sheets2013). Bale Variant No. 0020 (see figure 10) indeed resembles the industrially compressed bales that arrive in markets all over Africa, including the one made up of T-shirts that Moussa bought in Niamey in 2011. However, it is thinner. At around six and a half feet tall, and with a width of thirty inches, it stands just larger than a person. It could contain a human form within it. The garments threaten to escape the ribbon binding them. The bright colors contrast with one another, asserting the individuality of the objects crushed together.

Figure 10. Shinique Smith, Bale Variant No. 0020, 2011

Fabric, paper, ribbon, and found objects; photographed by Christian Patterson

Like Moussa’s works, Smith’s treatments of secondhand clothes, which include smaller abstract sculptures that hang from the ceiling, call attention to the garments themselves in order to compel viewers to imagine the bodies that they once dressed and the larger systems that they represent. Most of Smith’s work relies on the accumulation of garments to form large sculptural installations, defying their former shapes that conformed to human bodies. Moussa, on the other hand, largely allows the former wearers’ bodies to echo in coats, dresses, and T-shirts that, however transformed, are not only recognizable, but also could easily be slipped off their hangers and worn by a brazen visitor. Fashion Victims emphasized, above all, the act of wearing clothes and the multiple commercial and symbolic networks implicated in such an apparently simple, universal act that is so often taken for granted.

In Fashion Victims Moussa summoned fantasies of Africans solving the environmental harm of industrialization through the recycling of discarded Italian clothes, only to deflate them with incisive observations that Cameroonians and Nigeriens too seek the comforts and identities made possible by industrial production. He validated the compassion that motivates both philanthropic donations and philanthropic consumerism while insisting simultaneously on a larger critique that reveals the limitations and contradictions in both clothing donations and the fair trade industry. Like Anatsui’s liquor bottle caps, Moussa’s secondhand clothes and, most important, their social histories, find new visibility in fine art. Like Kouyaté’s haute couture collections and Smith’s sculptures, Moussa’s installation demanded that we imagine the travels of bales of used clothing much of the world never sees. In his reuse of secondhand clothes as the raw material, Moussa asked viewers to participate in a rigorous analysis of industrial systems that now touch everyone on the planet in some manner or another, but the exhibition also reveled in the pleasure and comforts of industrially produced new clothes.

Jewelry, toys, and other commodities made from recycled materials in Africa are often marketed in tourist and export markets through systems of “fair trade” and other philanthropic consumerist appeals to the compassion of potential clients. “Yes,” Moussa says, “I created a utopic brand. Do Good Goods: to do good with goods. Do Good Goods” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). Moussa hopes to introduce a line of ethically produced clothing, although his thus far fictional brand, Do Good Goods, also questions just how much good one can do with a purchase. The concept is utopic, but still worth enacting, even if, as he notes, philanthropic consumerism is still “entering into the machine” of consumption (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). The brand name is in English, conveying the power and mobility of that language in both Francophone West Africa and Italy. It is also a play on that other D & G, the Italian brand Dolce & Gabbana that struck Moussa as ubiquitous in the streets of both Douala and Milan.

Fair trade organizations and other self-described alternative trade organizations attempt to ameliorate systemic inequities by defining fair wages and work conditions for farmers and artisans and by promoting the resulting commodities, usually in markets in the developed world—although some sell products closer to home. They often succeed in getting capital for producers, but they sometimes do so by treating artisanal and agricultural expertise as natural resources. For people in industrial cultures, such ventures limit their political imagination by denying their ability to act as anything but consumers. Slavoj Zizek Reference Žižek2009b) has called this “cultural capitalism at its purest. . . . You buy your redemption from being only a consumerist.”Footnote 7 This redemption adds unique dimensions of pleasure to purchasing, owning, using, or giving a beautiful object, actions that are themselves meant to be pleasurable. You get to do good even as you acquire goods. It is one way to construct an identity as a socially responsible person in a conformist, consumerist vein.

Alternative trade organizations and other forms of philanthropic consumerism, or marketized philanthropy, do not necessarily offer alternatives, and they can reinforce and perpetuate capitalist exploitation (Nickel & Eikenberry Reference Nickel and Eikenberry2009). In the networks where Cameroon, Niger, Italy, and the United States intersect, it is not adequate to call for fairly traded clothing and museum shop souvenirs without also calling for fairly traded petroleum, uranium, and cocoa. Otherwise, even well-intentioned projects risk replicating the extractive practices of mining companies by assuming the greatest importance of the movement of commodities from Africa to other continents, to those all-important “consumers.” The secondhand garments in Fashion Victims remind us that commodities move in and around Africa, and that Africans, too, participate in consumerism, even if many wish to consume more than they actually are able to (Bauman Reference Bauman1998). The needs and desires for nutritious, delicious food and protective, stylish clothing on the part of Africans must not be subsumed by a hegemonic consumerist system that prioritizes the delivery of new commodities to Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, leaving Africa the “copies made in China or old clothes transported by the Salvation Army,” as described by Moussa on the untitled brown dress.

Furthermore, it is not adequate to call attention to the ways that garments circulate without also investigating how people circulate—with and without papers—in many of these same networks. Advertising products made in Africa through appeals to consumers’ philanthropic urges obscures the larger system that has caused the poverty that is then portrayed in ways that evoke pity from customers. As Nickel and Eikenberry have argued, “consumption philanthropy is not a discourse about transformation but rather a discourse about continued, even increased, consumption” (2009:980)—or as Moussa says, it is another way of entering into the “machine” of consumption. Despite genuine intentions to improve the lives of laborers, marketized philanthropy necessitates prioritizing commodities over people, and capital over lives. It also demands the conceptualization of people as either producers or consumers, rather than as workers, artisans, farmers, parents, citizens, eaters—and wearers. Do Good Goods points to all of these challenges, and its imperative to “Do Good” calls on us to imagine action beyond consumption, to imagine meaning beyond the valuation of seductive brands like Dolce & Gabbana.

Fashion Victims and Dangerous Games

Moussa’s 2011 work Top Model humorously but directly implicates the viewer in the dangerous systems of production and exchange that make up the world fashion industry (see figure 11). It demonstrates one method by which people, especially women, are trained to imagine themselves as consumers—and as objects to be dressed and viewed by others. Top Model emphasizes the viewer’s own position as a wearer of clothing. On a gold-framed black ground, a rough silhouette of a woman’s torso wears a white plastic sack as a blouse, which is cinched tightly with another plastic bag—this one in a contrasting bright yellow color. The base of the work is a mirror, and the perfectly round head reveals what is beneath the whole work. In a wry, ironic gesture, Top Model allows everyone, as Moussa said, to “become a top model” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011).

Figure 11. Alioum Moussa, Top Model, 2011

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

But what kind of top model is this, whose garments consist of the ubiquitous detritus of twenty-first century consumer culture? Plastic bags are not valued commodities, but disposable objects intended for carrying more valuable objects, often food. The roundness of the mirror-head invites a viewer to enter the work, but the perfect roundness also reminds the viewer that the work is one of imagination. No human head conforms to such a shape, and for most of us, the transformation into a “top model” would remain two-dimensional and incomplete. The art historian John S. Weber (Reference Weber and Aronson2012) interprets Nnenna Okore’s 2009 installation Mbembe (see figure 12) as presenting bags as shadows of the incomprehensible scale of contemporary industrialized consumption.Footnote 8Top Model focuses instead on the relationship of the human body to the bag, insisting that you reckon with your own desires, your own body, and your own plastic bags. For you, the “top model,” the game of seduction quickly reveals itself as a game of history. The fantasy of admiration and luxury has tricked you into imagining what it would really be to wear a plastic bag—do any of us ever feel that we actually own a plastic bag? Bags are instead objects with fleeting presences, accompaniments to actual commodities. Top Model does not point out only that bodies can be commodities—but also that we actively and constantly offer up our bodies for various kinds of commoditization.

Figure 12. Nnenna Okore, Mbembe, 2009

Plastic bags, courtesy of the artist

One seductive game of history that interests Moussa is the ongoing deskilling of the population at large and artists specifically. This applies across many media, but it is perhaps most notable in textiles and dress. While Moussa’s mother spun yarn, and also knit and wove textiles before sometimes dyeing and embroidering them, members of Moussa’s generation in Cameroon can purchase all of their clothes in prêt-a-porter form, even if they are secondhand or counterfeit. Around the world, the transition from artisanal production of textiles to industrially produced textiles has resulted in greater access to greater numbers of garments for most of the world’s population. It has also resulted in a rapid decrease in general understanding of how textiles are produced. The bales of secondhand clothing that arrive in Africa are the result of the production of more garments than the populations to which they are first marketed could possibly need.

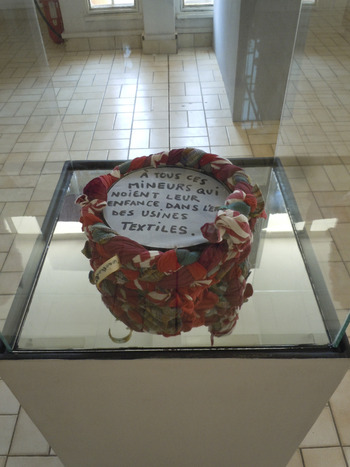

In addition to embroidering full garments to introduce the hand of the artist to these industrial commodities that hang on our bodies in paradoxically scrutinized but simultaneously unrecognized ways, Moussa reduces garments to less recognizable elements of artworks. He rips and cuts them, and then braids those rags into small sculptures (see figure 13). Through braiding, a technique associated with women’s hair, he shapes the sculptures into surrogates for a human body altered to attract others (Alioum Moussa, personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). Like most of the works in Fashion Victims, this untitled sculpture from 2011 invites a close approach. The braided cloth lends a rough but cozy texture, which is mediated by a vitrine that conveys the “art objectness” of the sculptures. As with Top Model and the untitled brown dress, looking at this small sculpture requires looking at oneself. It sits on a mirror, so that one inevitably catches a glance of one’s own face peering into the vitrine when trying to get a better look at the words on the raised circular braided frame.

Figure 13. Alioum Moussa, Untitled, 2011

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

In this work Moussa pays homage to a group of people whom he considers victims of fashion: children who may have worked to produce the garments he cut up to make it.

I saw several documentaries on Indonesia, where children work in severe conditions. It touched me very much. The pride of the parents of those children. Their difficult work. Their fragile health. . . . All of us are contributors to this phenomenon. When you look in the mirror, you also exist. I want to say that if I purchase an Italian brand, I also contribute to this torture. (Personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011)

Wearers of clothing in Europe, the United States, Asia, and Africa largely view the poor labor conditions in garment factories with a sense of fatalism and helplessness, despite the large scale and high stakes of dangerous factory conditions. Fires in 2012 and 2013 at factories in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan for suppliers to global chains like Wal-Mart and Zara have gained American and European journalists’ attention, but so far there has been little action from policymakers or outcry from the public (Manik & Yardley Reference Manik and Yardley2013; Motlagh Reference Motlagh2013; Walsh Reference Walsh2012; Walsh & Greenhouse Reference Walsh and Greenhouse2012). In April 2013 more than one thousand workers were killed and more than twenty-five hundred workers were injured in the collapse of a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh (BBC 2013). Angered by the persistent abuses and repeated tragedies, Dhaka residents launched street protests calling for accountability and reform (Paul & Quadir Reference Paul and Quadir2013).

After the spate of fires Charles Kernaghan, founder of the Institute for Global Labor and Human Rights, wrote in the industry publication Women’s Wear Daily that while corporate brands are protected by copyright laws, there are no comparable protections for the workers producing the clothing sold under those brand names (Kernaghan Reference Kernaghan2013). The value of people is reduced to capital in a system that casts people outside of history as atemporal consumers in a globalized economy (Coronil Reference Coronil, Comaroff and Comaroff2001; Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001). Laborers are expected to remain invisible. Moussa’s modest sculpture reinserts globalized production and distribution into a historical narrative and rehumanizes laborers and clothing wearers by refusing the simplistic identity of “consumer.” This game of history intrudes on our seemingly vital games of seduction, for which a young man in Douala in Cameroon buys fake D & G sunglasses or a middle-aged woman purchases clothes at a Zara in Italy. These factory workers in Bangladesh and the children in Indonesia in the documentary Moussa saw are clearly among those he considers victims, but what about the visitor to the exhibition, the person looking down this well? This dehumanizing, disempowering self-conception as a mere consumer also results in a kind of victimhood, however luxuriously clothed in the silk tunics and skinny jeans of fast fashion the victim may be.

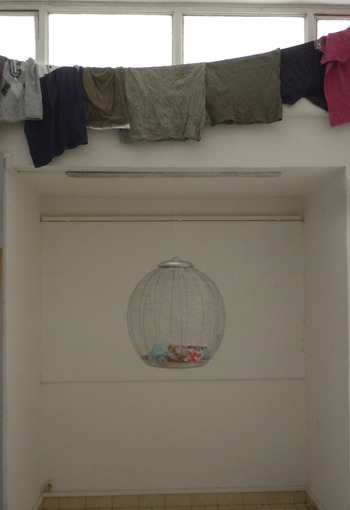

Two cages hung in the Niamey version of Fashion Victims (see figure 14). Such cages are well known to Niamey residents. You can buy them—and birds to keep in them—at a popular intersection of the Chateau Un neighborhood. In the installation these cages held garments and scraps instead. Moussa explained that “it is the enclosure of the young in these brands. I constructed these cages not for birds, but for the people who are in fashion” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). Represented by inanimate discarded garments, the most fashionable and wealthy visitor was again meant to pause, to face the possibility of being a fashion victim. Yet these cages alluded to the many youth aspiring to fashionableness, phantoms for whom globalization has contained many motivations for travel, but simultaneous restrictions on their mobility.

Figure 14. Alioum Moussa, Untitled, 2011

Mixed media, courtesy of the artist

While Moussa was in Biele, Italy, for an artist’s residency in 2010, many other Cameroonians and West Africans were also there seeking work in far more tenuous circumstances. Around one hundred thousand undocumented immigrants arrived in that year alone, many of them from sub-Saharan Africa (Caritas/Migrantes 2009; Lucht Reference Lucht2012). The clothes manufactured in Italy and the secondhand clothes imported in Africa were allowed far greater movement around the globe than the bodies of most young African men and women, adding poignancy to the clothing scraps standing in for fashionable young Africans in the birdcages in Fashion Victims. The Structural Adjustment Programs of the 1980s and 1990s and their associated regimes of austerity first pushed increasing numbers of African migrants to look for work in Europe, and those numbers only grew in the 1990s and 2000s. Neoliberal economic policies contributed directly to economic, political, and ecological disasters that motivated young men and women to attempt the life-threatening journey. From both Cameroon and Niger, the first leg is a long trip by land across the Sahara, during which migrants risk abandonment and vehicle breakdown, both of which can lead quickly to death in the harsh desert conditions. Days, weeks, or months in port cities waiting for a boat present their own dangers, although none as grave as the perilous sea voyage across the Mediterranean, usually to Spain or Italy. Desperate travelers crowd onto unreliable vessels, and many have died in ships that have capsized and sunk.

The transition to a fully cash-based economy in much of West Africa was swift, pervading the most rural reaches in a matter of decades in the late twentieth century. These were decades that saw a near-simultaneous constriction of access to capital just as cash was becoming essential to obtain basic goods, including food—and clothing. The cages represented the capture of fashionable bodies into the “machine of consumption,” from which they cannot escape. They also suggested the attempted control over African mobility by international organizations and by European nation-states that are all too willing to export secondhand goods and limited charity to Africa but are desperate to restrict continued African immigration to Europe. Once in Italy, many young Africans quickly become disillusioned by the economic challenges and xenophobic abuse they face. Some quickly move to other countries and others find diverse employment throughout Italy—including in the clothing factories in and around Milan.

By the time Fashion Victims was shown in Niamey, the Italian government was implementing its own austerity programs in response to the global financial crisis in which its debt repayment terms had changed drastically. In the constricted economy, some Africans were relying on financial assistance from their relatives in Senegal, Cameroon, and elsewhere, and there may have been a temporary increase in the rate of return of African migrants from Italy back to Africa (Davies Reference Davies2012). The anthropologist Hans Lucht (Reference Lucht2012) found that Ghanaian workers in Naples wear secondhand clothes in neighborhoods where they are targets of thieves who prey on them because of their vulnerable legal status, but that in their own communities they wear the brand new, stylish clothing afforded by an income paid in euros. The secondhand clothes provide a disguise of poverty, suggesting that the wearer has little or nothing to steal. Yet Lucht also noted that especially for migrants who remain undocumented, the relocation to Italy does not afford full access to either “material” or “symbolic” goods, and the unequal distribution of power can be even more stark in the suburbs of Italian cities than in the fishing communities from which his interlocutors had come.

With the bird cages’ allusions to the vast numbers of young Africans who have left the continent in the last decades, both those who survived and those who did not, the T-shirts, coats, and dresses in Fashion Victims hung heavier, their emptiness evocative of people who have left hoping to gain opportunities to purchase brand new clothes, to send money to their families, and to construct homes for those families. In her series Yoff, the Dutch artist Judith Quax photographed garments that washed up on the shore in Yoff, Senegal, a small fishing village from which many migrants depart on their way to Europe. The art historian Salah M. Hassan explains that these images depict “washed-up clothes amid otherwise clean water and bare surroundings, hinting at the vast emptiness of the beach they have appeared on. Though the vacant garments are shot relatively close up, this disparity is unsettling, as it underscores the impact of the loss they suggest” (2009:132). This blue shirt, like the scraps in Moussa’s cages, becomes a still, abstract object in Quax’s photograph Clothing 5 (see figure 15). On the beach and in the cage, the garments suggest absence. They are indices of the youth who have left—although they may remain in other metaphorical cages.

Figure 15. Judith Quax, Clothing 5, 2009

Photograph, courtesy of the artist

Conclusion

Even as Moussa interrogated his own and others’ culpability as accessories to the dehumanization and exploitation that constitutes the world fashion system, Fashion Victims was not a harsh accusation. He remarked that his work is “truly a critique of globalization, but a critique that I am developing in a flexible manner so that it becomes a discussion about identity. Because if I continue to critique too much, I cannot advance the discourse or create a brand of ecologically sound clothing” (personal communication, Nov. 29, 2011). Moussa did not suggest that a customer at a Zara in Milan suffers the same victimization as a young woman working at a garment factory in Dhaka, but he situated both as active participants in globalized economic systems with asymmetrical power relations. The discussion about identity in Fashion Victims began with an expectation of self-reflection: the recurring mirrors required encountering one’s own image repeatedly. Even more important, it proposed a reconceptualization of how the identities of others are imagined, and how identities are constructed over time, whether through relationships, labor, or consumption. Consumerism allows only identities of “consumers in a planetary market place: persons as ensembles of identity that owe less to history or society than to organically conceived human qualities” (Comaroff & Comaroff 2012:13). Consumerism’s games of seduction mask how it drains away other identities, and they conceal the unjust dynamics created and perpetuated by capitalist exchange. For Moussa, games of history open up spaces for critical analysis and potential change.

The topic of the particular game of history proposed in Fashion Victims—the relationship between garments and people—has proven to encompass subjects including art, fashion, industry, economics, and power. Moussa’s critique of the production, exchange, and use of fashion is built on long histories of dress innovation in Africa, mercurial fashion in Europe, and exchanges between them. Like other contemporary artists, he self-consciously locates himself in art historical narratives, both those about West African embroidery and others about modernist and contemporary récuperation (Smith Reference Smith2009, Reference Smith2011). He challenges the objectification of people through consumerism by highlighting the absurdity in global luxury branding. By choosing to create art from secondhand clothes and discarded thread, Moussa joins contemporary art practices of reuse and reflected world fashion trends of “up-cycling.” The intimacy and ubiquity of humanity’s relations with industrially produced clothing provide rich material with which Moussa portrays specific victims, especially those laboring to make garments and those struggling to wear the right ones. The garments in Fashion Victims are for people whose identities cannot be contained by labels like “victim” or “consumer.”

In its expansive and playful exploration of victimhood in world fashion, Fashion Victims demanded empathy and compassion. In its purposefully disheveled aesthetic, Fashion Victims summoned for consideration the games of seduction with which its visitors occupy much of their time. The game may be dressing well to attract friends, lovers, and colleagues. Or it can be the purchasing of commodities—sometimes out of a simultaneous desire to give and to possess. Moussa’s invitation to a game of history opened up the transformative potential of his ongoing larger project, which includes the founding of a contemporary arts space in Niamey, named La Cour Commune, in 2013. He cites his experience at Art Bakery as an important influence for this project. In particular, he mentions Leye’s humanism, which manifested itself in “his generosity in sharing his experiences as an art historian, his sense of pedagogy, and above all, his belief in making art a vector for development.” La Cour Commune emulates the Art Bakery’s “sharing of experiences, for the opening to what is different” (personal communication, Feb. 24, 2014). Fashion Victims was just one part of an ambitious artistic agenda intended to effect social change in West Africa.

When consumed by games of seduction, people are too easily victimized by themselves and others, as they chase the brands they hope will define them to others. By entering a critical discourse with others about the dangers of industrial fashion, visitors to Fashion Victims were invited to enter a game, or jeu, whose rules disallowed the solipsism of the je encouraged by luxury branding. Most important, this playful game of history bet on the future. Only people can shift imbalances of power, and educating ourselves about those harmed by the systems in which we participate is an important step. If achieved on a large scale, récuperation of discarded garments, the production of better quality clothes, and longer-term use of clothes can slow the pace of the global machine of consumption and waste. If people with economic and political power demand improvements in the conditions of industrial production, they can effect change. We may be culpable, we may be victimized, but a utopic branding gesture to “Do Good” demands that we think of ourselves foremost as doers rather than consumers. As the repeated mirrors in Fashion Victims insisted, we must first visualize ourselves in order to imagine—and change—our relationships to our clothes, to our histories, and to one another.

Acknowledgments

The research for this study was funded by a Fulbright-Hays Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship, the Cornell University Departments of the History of Art, Africana Studies, and American Studies, and the Cornell University Graduate School. It was also conducted with the support of the Salon International de l’Artisanat Pour la Femme (Niamey, Niger).