Many Americans agree that incivility in politics is a problem and has been one for a long time (Herbst Reference Herbst2010). Many speak of incivility as a singular concept; that is, a set of words and phrases that apparently “everyone” knows have no place in good democratic governance. Recent work has found systematic variation in what people perceive as uncivil. I argue that these variations stem not only from partisan reasoning but perhaps more importantly from stereotypes about race and gender, indicating that incivility itself is an identity-laden construct for most Americans. If perceptions of incivility depend on the identities not only the person observing the uncivil speech but also on the identities of those involved with the communication—the speaker and target—then these perceptions are perhaps susceptible to manipulation by political elites to either use uncivil speech in their own politicking or disparage political opponents who can be framed as uncivil. But these downstream consequences are dependent on understanding the extent to which incivility perceptions are context and identity dependent.

Most existing work on incivility perceptions focuses on partisanship or specific types of rhetoric (e.g., insults or threats) (e.g., Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Gubitz, Levendusky and Lloyd2019; Muddiman Reference Muddiman2017; Mutz Reference Mutz2015). Some recent work has also studied how the gender of the person exposed to uncivil speech can moderate those perceptions (Kenski, Coe, and Rains Reference Kenski, Coe and Rains2020), and how the identity of those speaking uncivilly can result in varied perceptions of incivility (Muddiman, Flores, and Boyce Reference Muddiman, Flores and Boyce2021; Sydnor Reference Sydnor2019a). This study extends the existing body of research by systematically testing a whole host of potential identities at once, instead of opting for more traditional experimental designs that vary one or two features of uncivil speech at once. Further, this study furthers our understanding of how race intersects with perceptions of what constitutes uncivil speech. This is important because incivility is a historically racialized concept surrounding minority political actions, and racialized perceptions of incivility could affect the political fortunes of efforts to secure racial equality (Kirkpatrick Reference Kirkpatrick2008; Lozano-Reich and Cloud Reference Lozano-Reich and Cloud2009; Rood Reference Rood2013).

To address these gaps, I employ a conjoint experiment embedded in a nationally representative survey of 450 White, non-Hispanic/Latino Americans to test how the identities of a speaker, target, and observer of uncivil speech induces variations in perceptions of incivility. I find that the identity of those involved in uncivil discussions—their partisanship, race, and gender—moderates perceptions. Specifically, White Americans are more likely to perceive incivility when a speaker directs it at their co-partisans, more likely to perceive incivility when the speaker or target are women, and less likely to perceive incivility a speaker directs it at a Black American. These latter perceptions are moderated by prejudiced attitudes such that those with strong prejudiced attitudes least strongly perceive incivility directed at Black Americans. The implication of these findings is that White Americans are not perceiving norm violations equally in all cases, and especially in terms of identity. They seem to hold women to a higher standard in their expectations of civility and, among those with less prejudiced attitudes, are more sensitive to incivility targeting Black Americans. Moreover, I argue that incivility, due to these variations in perceptions, can act as a tool for bolstering the status quo.

Defining political incivility

I define political incivility as perceived, norm-violating political communication (Mutz Reference Mutz2015, 6). Political incivility occurs when an individual (i.e., an audience member) perceives a statement from a speaker to a target as norm-violating; this entails a reaction to a dyadic combination of speaker and target. In political settings, a common definition of norm violations involves “violations of politeness that include slurs, threats of harm, and disrespect” (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Gubitz, Levendusky and Lloyd2019; also see Stryker, Conway, and Danielson Reference Stryker, Conway and Danielson2016). But if people perceive uncivil speech differently depending on who says it and who it targets, then the consequences of perceived incivility are unevenly distributed and consequences of such speech on democracy are not as easily studied.

While much of the existing research on political incivility focuses on clear cases of norm violations—that is, experimental treatments designed to be as uncivil as possible—there are also instances where perceptions of norm violations depend on the political context. After all, what a person construes as a “threat of harm” or “disrespect” is largely a subjective assessment, and it will likely vary depending on the context. Further, I argue that we should better understand how and why perceptions of incivility vary so that we can then better understand any effects of incivility. These effects include efficacy (Sydnor Reference Sydnor2019a), trust in government (Mutz Reference Mutz2015), and negative affect toward partisans (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Gubitz, Levendusky and Lloyd2019), all of which can have notable consequences on American democracy. This study aims to elucidate the antecedents to these effects.

Politics and incivility perceptions

Existing research has also looked at how partisanship may moderate people’s perceptions of incivility. A number of researchers find that people are less sensitive to incivility that comes from their co-partisans (Gervais Reference Gervais2019; Muddiman Reference Muddiman2017; Mutz Reference Mutz2015). This makes clear that there is some sort of in-group bias at play when partisans perceive incivility (Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004; Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015). For an audience member perceiving a speaker/target dyad, this means that she will likely have a bias in favor of a co-partisan. As such, if the speaker says something potentially uncivil, an audience member sharing the speaker’s partisanship may be inclined to diminish the severity of the uncivil communication.

Hypothesis 1a: Audience members will less strongly perceive incivility when the speaker is a co-partisan, relative to when the speaker is not, all else constant.

As for how perceptions vary due to the partisanship of the target, I predict that audience members will be more likely to perceive incivility when a speaker directs it at a co-partisan. The logic here follows work in social psychology that finds people are more sensitive to threats that target their in-group (Voci Reference Voci2006; Wann and Grieve Reference Wann and Grieve2005). This should extend to perceptions of incivility insofar that uncivil statements are norm violations and thus threatening in nature to one’s in-group. Further, Gervais (Reference Gervais2017) finds that incivility that targets in-party members triggers stronger emotional reactions. Because of this sensitivity to in-group members being treated poorly, audience members will be more likely to detect incivility when a speaker directs it at a co-partisan. While existing work has explored the question of uncivil speakers thoroughly, this question of those targeted by incivility remains unaddressed.

Hypothesis 1b: Audience members will more strongly perceive incivility when the target is a co-partisan, relative to when the target is not, all else constant.

Gender and gender stereotypes

Gender identity is subject to a set of norms about what is and is not appropriate for women to say or for others to say to women (Mendelberg and Karpowitz Reference Mendelberg and Karpowitz2016). Moreover, gendered stereotypes and gender roles likely play a prominent role in many Americans’ perceptions of what is means to be uncivil. After all, gender is one of the primary means by which people forms perceptions about others; that is, it is one of the go-to heuristics people rely on, even when gender has nothing to do with the issue at hand (Ito and Urland Reference Ito and Urland2003). Further, even when people are primed to think about gender stereotypes, they often dominate discourse (Mendelberg and Karpowitz Reference Mendelberg and Karpowitz2016).

While there are numerous stereotypes about women, most fall into one of two major stereotype categories that women are (1) warmer and (2) less competent than men (see Ellemers Reference Ellemers2018 for a thorough review). Many people, either implicitly or explicitly, understand women through these two stereotypes regarding warmth and competence: that is, women care more about others, are better at expressing concern, are more sensitive than men, and are physically weaker than men. Moreover, these stereotypes become prescriptive insofar that many believe women should act in a manner consistent with their stereotype (Prentice and Carranza Reference Prentice and Carranza2002).

Incivility, as discussed earlier, is a harsh sort of rhetoric, the sort that is often frowned upon by others because it violates certain social norms (Mutz Reference Mutz2015). This becomes a gendered issue when we consider that many believe women should be warmer and nicer than men. Women who engage in uncivil speech challenge the dominant stereotype about how they should behave. And women who challenge these sorts of stereotypes are judged more harshly than women who conform to them. For example, Phelan, Moss-Racusin, and Rudman (Reference Phelan, Moss-Racusin and Rudman2008) find that supervisors punish women who express higher levels of competence in mock hiring processes by giving them less favorable evaluations, shifting attention to their perceived deficiencies in other areas; this pattern was not observed with male applicants. Further, Boussalis et al. (Reference Boussalis, Coan, Holman and Müller2021) find women in politics express less anger than men do, arguing that these prescriptive stereotypes of how women behave have real consequences in politicking. Thus, I contend that people will perceive incivility more strongly when the speaker is a woman, due to the woman breaking not only norms of politeness applied to everyone but also breaking specific stereotypes about how women should act.

Hypothesis 2a: Audience members will more strongly perceive incivility when the speaker is a woman, relative to when the speaker is a man, all else constant.

One consequence of the stereotype that women are weaker and more sensitive than men is that women are often perceived as needing protection from harm (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996). This stereotype, and subsequent bias, is often internalized during childhood when gender norms are typically instilled in children, even from parents who consciously try to raise their children in counter-stereotypical ways (Bos et al. Reference Bos2021; Endendijk et al. Reference Endendijk2014, Reference Endendijk2017). In fact, even adult women can express these sort of sexist attitudes in response to perceived hostility toward women (Fischer Reference Fischer2006). Thus, I expect Americans will be more sensitive to incivility when a speaker targets a woman compared to that speaker targeting a man.Footnote 1

Hypothesis 2b: Audience members will more strongly perceive incivility when the target is a woman, relative to when the target is a man, all else constant.

Race and prejudice

As stated earlier, incivility as a concept has been historically racialized by those in the majority to silence racial minorities’ speech (Lozano-Reich and Cloud Reference Lozano-Reich and Cloud2009; Rood Reference Rood2013). It stands to reason, then, that the race of the speaker or target can affect someone’s perceptions of incivility. Specifically, I argue that the key to understanding this dynamic lie with some White Americans’ prejudiced attitudes.

America’s racial hierarchy is useful for understanding White Americans’ potential attitudes toward a speaker or target involved in uncivil speech. White Americans are, by and large, the most socially powerful group in America (Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant2014). White Americans dominate the country’s history books as heroic figures and figureheads of democratic citizenship (Allison and Goethals Reference Allison and Goethals2011). And because most White Americans live in segregated communities, much of their exposure to Black Americans is through media, which often portray them as dangerous criminals (Jackson Reference Jackson2019).

The theory of social dominance orientation (SDO) provides a partial explanation for why this racial hierarchy may matter for some White Americans assessing the uncivil nature of some political speech. This theory posits that dominant groups in society have such a strong preference for the status quo that they outright desire a hierarchical society that places them at the top at others’ expense (Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto2001). That is, those with these attitudes express an outright desire in many cases to dominate racial minorities in the United States.

It follows that perceptions of incivility could be subject to these prejudiced attitudes as incivility is generally considered a negative behavior in America (Bybee Reference Bybee2016).Footnote 2 Those with strong prejudiced attitudes are motivated to see Black Americans or other racial minorities as uncivil because incivility is often threatening; these people want to see these groups as uncivil because it confirms what they already believe: that these groups are threats.Footnote 3

Hypothesis 3a: Audience members with strong prejudiced attitudes will more strongly perceive incivility if the speaker is Black, relative to an audience member with weaker prejudiced attitudes (i.e., a moderation effect), all else constant.

Extending this logic from speakers to targets, those with strong prejudiced attitudes are likely to express outright hostility toward Black Americans and other minorities; they want to hate these groups. As an extension of that, I posit that those with prejudiced attitudes want to see others expressing hostility toward Black Americans and other racial minorities. That said, while they may enjoy the uncivil statements themselves, they will be unlikely to admit that they perceive the statements as uncivil.

Hypothesis 3b: Audience members with strong prejudiced attitudes will less strongly perceive incivility if the target is Black, relative to a target with weaker prejudiced attitudes, all else constant.Footnote 4

Method

My framework to study incivility involves a dyad consisting of a speaker and a target of the incivility, and an audience that is exposed to that communication. I predict that the audience’s reaction to any dyad depends on both ascriptive and descriptive features as well as the type of incivility. I study the impact of the hypothesized features via a conjoint experiment. This approach allows one to vary several features of stimuli and assess the causal effects of each feature independent of the others (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Green2021). The advantage of this approach, as compared to a factorial vignette experiment, is that it allows me to study that large menu of dimensions about which I hypothesized. Specifically, respondents are randomly exposed to a set of features, multiple times. As Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Green2021) explain, multiple exposures in conjoint experiments do not appear to lead to satisficing.

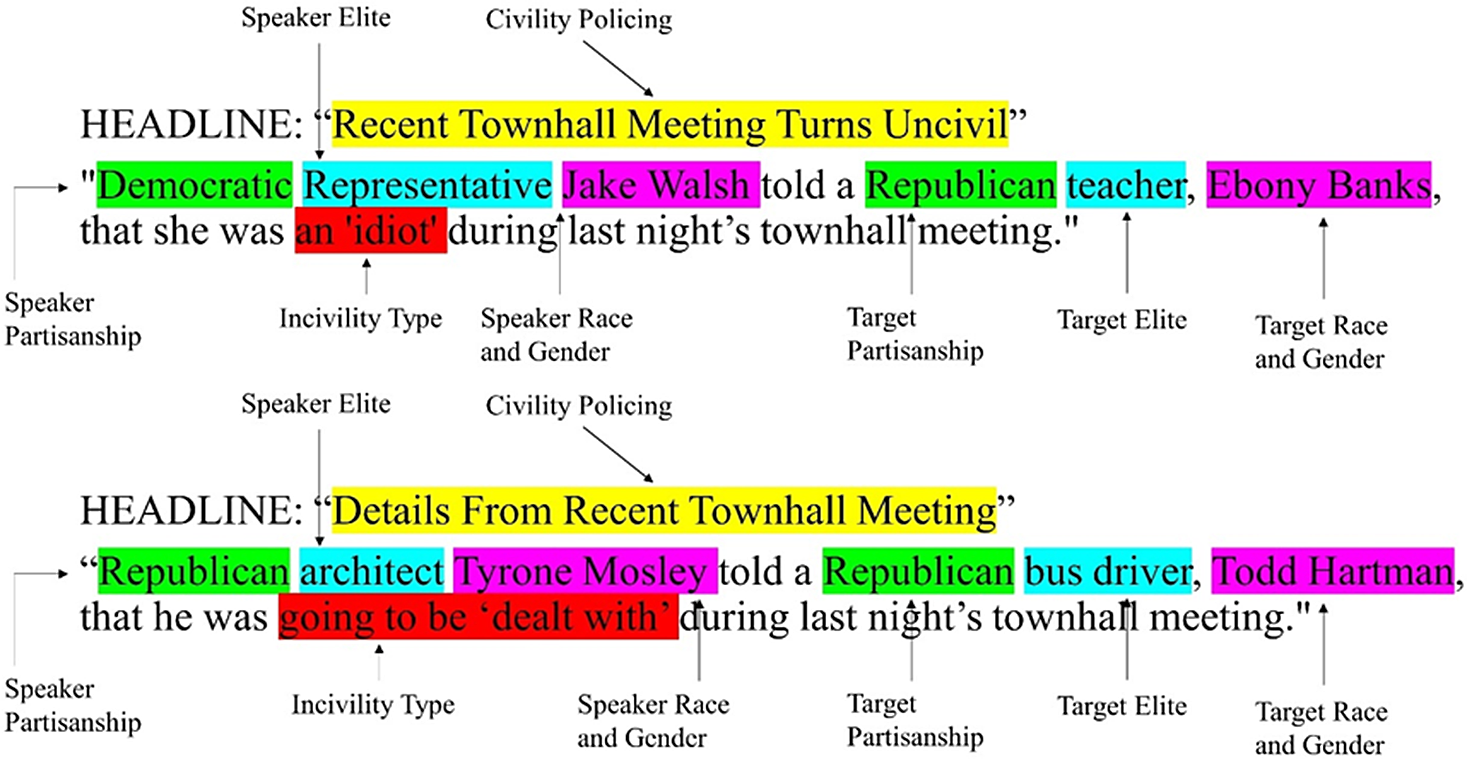

I test the effects of 10 features of an uncivil communication: (1) the speaker’s partisanship; (2) gender; (3) race, and (4) elite status (e.g., elected official or not); (5) the target’s partisanship; (6) gender; (7) race, and (8) elite status; (9) the type of incivility; and (10) the presence of civility policing (i.e., an explicit pointing out of an uncivil statement). Each of these 10 features has two or more possible values that are always varied with each iteration of the conjoint experiment.Footnote 5 I will detail the specific connection of each attribute to their respective hypothesis below. I preregistered the hypotheses at AsPredicted.org.Footnote 6

Note that I included three features that I did not discuss above: elite status, civility policing, and the type of incivility. I include the former to make the experimental design more externally valid, as job titles are frequently attributed to those mentioned in news articles. And I include civility policing also to enhance ecological validity as headlines often vary in whether it explicitly calls out incivility. Moreover, civility policing itself is worth further exploration in future work on the subject, but it is not the subject of interest in this particular study (see Braunstein Reference Braunstein2018 for an introduction to this concept).

I omit the type of incivility as a formal hypothesis because the existing literature is clear on expectations. Namely, that due to exceedingly strong violations of social norms, different types of incivility evoke stronger reactions (Muddiman Reference Muddiman2017; Stryker, Conway, and Danielson Reference Stryker, Conway and Danielson2016). For the purposes of this study, I follow Muddiman’s (Reference Muddiman2017) work by studying personal-level and public-level incivility; specifically, I study insults and threats as forms of personal-level incivility, and slurs as a category of incivility that falls somewhere between the two major categories. First, insults deride political opponents. Second, threats often aim to increase make a target concerned for their own safety. Finally, slurs are derogatory, taboo words or phrases that a given culture perceives as incredibly offensive to a certain group of people (Henderson Reference Henderson2003). I am not the first to draw these distinctions, which Muddiman’s (Reference Muddiman2017) research validates. As such, we should expect slurs to elicit the strongest perception of incivility, followed by threats, and then insults.

Conjoint design

After a pretreatment survey, respondents are told that they are going to read excerpts from recent articles about politics. They then receive six different excerpts, each of which is randomly generated from the 10 different attributes mentioned above.Footnote 7 Table 1 shows each attribute and respective possible levels, as well as the relevant hypotheses. For occupation, I included numerous “ordinary” jobs, such as teacher, accountant, and nurse so that respondents did not consistently receive a description of the same nonelite job in each scenario. Also, I varied incivility type in a similar manner, with many different operationalizations all falling under the three main categories: insults, threats, and slurs. I discuss the variations in name/race/gender below.

Table 1. Attributes and levels in conjoint experiment

A couple of examples of this short vignette are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Examples of treatment variation.

After reading each vignette, the survey asked respondents to assess how uncivil they thought the scenario was. This process was repeated another five times for six total excerpts.Footnote 8

Names and race

To vary race and gender in the scenarios, I followed the audit study literature, using names (Bertrand and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004; Butler and Homola Reference Butler and Homola2017). Specifically, this study relies on findings from Gaddis (Reference Gaddis2017) to select 64 first names to use in the study (16 for each gender/race combination), along with 15 last names that reliably denote a White or Black identity. I chose names from his results that control for class with six exceptions (see Appendix I for those six names), and I also account for the class confound by adding last names that are distinctly Black or White. The 64 names are all perceived to be the intended race at least 90 percent of the time, according to the Gaddis findings. I adopted the last names straight from Gaddis’ study as well. Names were randomly generated according to what race and gender were randomly assigned to the participant for any given task. First name and last name were randomly assigned separately to increase variation while still ensuring that the race of the first and last name was kept constant such that no one could receive a treatment where a speaker had a distinctly Black first name and a distinctly White last name, for example. I detail all first and last names chosen for this experiment in Appendix I.

Procedure

The survey started (prior to the scenarios) with respondents answering a set of pretreatment questions including partisanship (seven-point scale), gender, and the SDO7 scale (α = 0.83, μ = 0.264, sD = 0.192) (Ho et al. Reference Ho2015). This latter scale is used to test Hypotheses 3a and 3b. I also asked for respondents’ basic demographic information, their partisanship, and their political ideology pretreatment (full question wording can be found in Appendix D). Participants then received the experimental treatments. After each scenario, participants answered the main posttreatment item, a five-point perceived incivility scale (μ = 3.611, sD = 1.336), which is fairly standard in the existing literature (e.g., Muddiman Reference Muddiman2017; Stryker, Conway, and Danielson Reference Stryker, Conway and Danielson2016; Sydnor Reference Sydnor2019a).Footnote 9

Participants

The sample is 450 White, non-Hispanic/Latino American adults. The nationally representative sample was collected by Bovitz, Inc. between October 21 and 25, 2019. I collected an all-White sample because my predictions concerning prejudiced attitudes (H3a and H3b) are predicated on White Americans’ attitudes; I wanted to maximize my ability to detect the predicted moderation effects. I determined the sample size based on recommendations provided by Orme (Reference Orme2010), who advises that conjoint analyses looking at subgroups use about 200 respondents per subgroup (65). Since I am analyzing the data using interactions to test two of the hypotheses, it is prudent to think of the analyses as having two main “subgroups,” one group with “low” levels of out-group hostility, and one group with “high” levels.Footnote 10 Full demographics for the sample can be found in Appendix A.

Results

I analyze the data using ordinary least squares with all variables recoded from 0 to 1; all standard errors are cluster robust on the respondent (to account for the fact that each respondent produced six different rows of data).Footnote 11 I first present a model that tests Hypotheses 1 and 2, or the hypotheses that do not require moderation analyses to test. The reported significance tests are two-tailed in order to present a more stringent test of the hypotheses. The model shown in Figure 2 tests whether respondent’s perceptions of incivility (i.e., five-point scale from “not at all uncivil” to “very uncivil”) is affected by the following: the partisanship of the speaker (H1a) and the target (H1b); the gender of the speaker (H2a) and the target (H2b); the type of incivility used (no hypothesis) the race of the speaker (no hypothesis) and the target (no hypothesis); the presence of “civility policing” (no hypothesis); and the elite status of the speaker and target (no hypothesis). I include variables for which there are no associated hypotheses, including two race variables, because although unrelated to my central hypotheses (some of which are contingent on prejudiced attitudes), it is still important to account for them in this model since I am trying to isolate the effects of particular features of the vignette. This “base” model is later used again, with the relevant interactions added to it, to test Hypotheses 3a and 3b while accounting for the variation in the vignettes.

Figure 2. Perceptions of incivility and how they vary.

Figure 2 shows the results of the base model, broken down by hypothesis. First and foremost, I find that sharing partisanship with the speaker has no effect on perceptions of incivility.Footnote 12 This indicates that people perceive in-party members and out-party members similarly when it comes to making uncivil statements, replicating some prior work on the subject (e.g., Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Gubitz, Levendusky and Lloyd2019). However, in contrast, other work that finds people are less sensitive to incivility from their co-partisans, relative to their out-party (Gervais Reference Gervais2019; Muddiman Reference Muddiman2017). This may be due to the variation in the other aspects of the conjoint. My approach presents a wider variety of possible intervening variables to people’s perceptions of incivility, while the work that finds people less sensitive to co-partisan incivility has to date focused only on the intersection of partisanship and incivility type.

However, I do find strong support for H1b that predicts that those who share partisanship with the target will be more likely to perceive incivility, relative to audience members who do not share partisanship with the target. I find strong effects in the predicted direction for partisanship (p < 0.01). This indicates that people are more likely to perceive incivility when a speaker targets a co-partisan with uncivil speech, relative to situations wherein the audience member does not share partisanship with the target.

Next, I turn to the hypotheses concerning gender, namely that people would more strongly perceive incivility when it was spoken by or targeted at a woman, both of which are supported.Footnote 13 As Figure 2 shows, there are positive effects of the speaker (p < 0.10) or target being a woman (p < 0.01). Both of these findings reflect the effects that gendered stereotypes in American society can have on people’s perceptions of uncivil speech from and toward a woman. White Americans judge women who act uncivilly more harshly than men, likely due to stereotypes about how women are supposed to be “nicer” than men. And White Americans are sensitive to women being targeted by incivility, likely due to paternalistic notions about protecting women, who they believe are inherently sensitive.

I next move on to the question of whether prejudiced attitudes affect these perceptions. As one can see in Figure 2, the results show that White Americans more strongly perceive incivility when the target is Black. But these results do not test the actual hypotheses as those require an investigation of moderation effects. Recall that H3a predicts that those with strong prejudiced attitudes will more strongly perceive incivility if the speaker is Black, relative to an audience member with weaker prejudiced attitudes. This implies an interactive model between the presence of Black speaker and prejudiced attitudes. Specifically, I operationalize this as social dominance orientation. I present the interaction graphically in Figure 3, with the details appearing in Appendix B. As one can see in the figure, I find no evidence in favor of H3a.Footnote 14 This indicates that people with strong prejudiced attitudes do not perceive incivility more strongly from Black speakers.

Figure 3. OLS interaction model for racism toward speaker.

And Hypothesis 3b predicts that those with strong prejudiced attitudes will less strongly perceive incivility if the target is Black, relative to audience members with weaker prejudiced attitudes. This, again, calls for an interactive model between SDO and the presence of a Black target. Figure 4 shows some support of this hypothesis, but from a different angle than originally precited. This figure shows that those with the least prejudiced attitudes (i.e., low SDO) also exhibit the highest degree of sensitivity toward uncivil speech directed at a Black target (p < 0.10).Footnote 15 . This indicates perhaps that those with stronger prejudiced attitudes are indeed less sensitive to incivility that targets Black people, but it may not be the case that they are actively trying to ignore such incivility. These findings replicate across other models, including tests of reactions to specific dyadic combinations of speaker and target (see Appendix C).

Figure 4. OLS interaction model for racism toward target.

This implies that SDO attitudes predict incivility perceptions in cases where the target of uncivil speech is a Black person, regardless of the actual incivility being used. These moderation effects reveal why respondents, as shown in Figure 2, more strongly perceive incivility when a speaker directs it at a Black target. As one can see in Figure 4, those with the least prejudiced attitudes most strongly perceive incivility that targets a Black person. In the aggregate, this result becomes weaker. Overall, however, this is clear evidence in favor of the argument that White Americans with prejudiced attitudes differentially perceive incivility depending on the race of the target.

As for features for which I do not have an associated prediction, we see some clear trends. Figure 2 shows that while the presence of slurs greatly affects people’s perceptions that the exchange was uncivil, threats do not. The effect of slurs on incivility perceptions is large and statistically significant (p < 0.001), providing clear evidence that respondents see slurs as more uncivil than other types of uncivil discourse, replicating some prior work on the subject (Stryker, Conway, and Danielson Reference Stryker, Conway and Danielson2016). However, respondents do not perceive threats are more uncivil than insults. Further, there is no observed effect for the remaining variables that did not have an associated hypothesis.

This might be surprising in at least one area: the null effect on the elite status of the speaker. Elites may no longer hold a vaulted place in American culture; this may reflect the rise of polarization and decline in trust in government (Public Trust in Government 2019). In Appendix E, I replicate analyses from Frimer and Skitka (Reference Frimer and Skitka2020) that test whether people perceive incivility more strongly from their in-party elites than they do in-party nonelites. These additional analyses also exhibit null effects. This difference from Frimer and Skitka is likely due to the wider menu of features this experiment tests, as opposed to a more straightforward design that the aforementioned study employs.

Discussion and conclusion

Many Americans are greatly concerned with incivility in politics, with most of the electorate going as far as saying the phenomena have reached “crisis levels” (The State of Civility 2017). Scholars find good reason to be wary of political incivility, as it can erode trust in institutions (Mutz Reference Mutz2015), increase hostility (Gervais Reference Gervais2017), and even disincentivize certain groups of people from engaging in politics (Sydnor Reference Sydnor2019a). Empirical strategies for identifying incivility have evolved from manual content analyses of news corpuses (e.g., Berry and Sobieraj Reference Berry and Sobieraj2014) to automated content analyses that rely on dictionaries of “uncivil” terms (Coe and Park-Ozee Reference Coe and Park-Ozee2020), machine-learning programs that adapt in real-time to evolving discourse (Hosseini et al. Reference Hosseini, Kannan, Zhang and Poovendran2017), and hybrid methods that retain human knowledge (Muddiman, McGregor, and Stroud Reference Muddiman, McGregor and Stroud2019). The issue with many of these methods of inquiry is that they often fail to account for social dynamics and human bias in how we perceive incivility.

I show that researchers must account for variations in incivility perceptions going forward and attend to the gendered, racial, and partisan interplay at work when it comes to incivility. There is no single, universally accepted understanding of what is and is not uncivil; even slurs, though predominantly seen as uncivil in this study, may still be socially acceptable in some contexts (King et al. Reference King2018). My findings show that people form their own impressions based on a combination of their attitudes and the identity of those involved in an uncivil exchange in the following ways:

-

1. People are sensitive to their co-partisans being targeted by uncivil speech, while conversely being more likely to look the other way when an out-partisan is being similarly targeted.

-

2. People are more sensitive to women speaking uncivilly and being targeted by incivility; essentially, women need to watch their speech more, according to these findings.

-

3. People with strong prejudiced attitudes less strongly perceive incivility targeting Black Americans, making them easy targets for incivility for those strategic enough to capitalize on America’s history of White supremacy.

And while slurs may be the strongest predictor of whether someone strongly perceives something as uncivil, the findings in this study reveal a degree of partisan strategy at play in when and how people perceive incivility (Herbst Reference Herbst2010). Indeed, the findings make clear that partisans are overly sensitive to uncivil speech that targets a co-partisan. I posit that this is partly strategic, as outrage politics can be quite effective when one side can make the case that their party is being treated poorly (Braunstein Reference Braunstein2018). This also indicates to some extent that partisan calls for civility may be made in bad faith as a means to demean out-partisans for their “uncivil” behavior. White Americans may be politically motivated to perceive incivility when it is most convenient to them, such as when Black Americans or other minorities challenge white supremacy.

Gendered attitudes about what is acceptable for women to say seems to affect how strongly people perceive a woman’s political speech as uncivil (Ellemers Reference Ellemers2018). And the White Americans in this sample seemed especially sensitive to incivility targeted at women, indicating a patriarchal sort of prejudice (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996). If women and men are being judged by different standards on what constitutes incivility, then we must pay attention to the gendered biases that can accentuate attention toward some people’s speech, and not others. For example, the findings here potentially indicate that female candidates for office are hamstrung to carefully watch their language in order to appease gendered stereotypes of appropriate speech for women in America.

It is important to note, however, that this study’s conclusions regarding the gender of speakers and targets are only a starting point. This survey did not measure benevolent sexism, which I argue is likely underpinning the effects observed in this study. While my findings lay a foundation for future research to build off, I cannot definitively say that sexist stereotypes underly perceptions of uncivil speech coming from or directed toward women.Footnote 16

Further, even after accounting for every type of incivility and the other contextual features of an uncivil speech exchange, prejudiced attitudes can moderate White Americans’ perceptions of incivility. Specifically, White Americans with the lowest levels of social dominance orientation—a desire to dominate others in society—perceive incivility more when the target of that uncivil speech is Black. Meanwhile, those high on the scale do not seem to be particularly sensitive or blind to incivility targeting Black Americans. So, while racially progressive White Americans may more readily detect incivility that targets Black Americans, a whole swath of the population will likely not mind at all. This allows for an explicit type of prejudice to take place in American discourse under the guise of uncivil speech; that is, elites have carte blanche to say whatever they like about Black Americans so long as they play to the right audiences.

Perhaps more interesting to some are supplemental analyses where I measure the perceived incivility of a speaker depending on who they are speaking to. These analyses, found in Appendix H, show that Black women are routinely perceived as the most uncivil speakers, especially when they are speaking to White women. This is largely unsurprising due to the litany of research that finds that Black women are held to higher standards of personal conduct than white women or even Black men (Ashley Reference Ashley2014; Walley-Jean Reference Walley-Jean2009; Wingfield Reference Wingfield2007). While this study lacks the sample size to draw more definitive conclusions about the intersection of race and gender in regard to perceptions of incivility, future research should turn to these questions as they present ample opportunity to further our complex understanding of these phenomena.

In sum, what I find in this study is that claims about who is and is not uncivil are fundamentally about power. That is, who and what White people perceive as uncivil reflects their notions of power in America—who has it and who wants it. Those without power or those with less power are perceived as being less civil than those who already have power, like White men. As such, this study demonstrates that incivility is about identity and that incivility can be a tool for bolstering a status quo that benefits some while harming other, more marginalized voices in society. This could matter when contentious politics, especially those concerning race or gender, are deemed uncivil by those in power. In these situations, norm violations are not being perceived equally in all cases, specifically when the target of the uncivil speech is a woman, or a co-partisan, or Black. There are a series of double standards at play. And the outrage in politics surrounding just how “uncivil” everything has become is perhaps just another strategy: faux outrage politics that censures the speech of some, but not others. Perhaps, there is no incivility crisis in America; rather it is merely politically convenient to perceive as much when it suits some people more than others.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2022.7

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for suggestions and feedback from: Jamie Druckman, Matt Levendusky, Mary McGrath, Reuel Rogers, Margaret Brower, Pia Deshpande, Matt Nelsen, Kumar Ramanathan, and the Northwestern Political Behavior Workshop. Special thanks to Amanda d’Urso for invaluable assistance with analysis and open-source code.