Steve Reich's music for Robert Nelson's film Oh Dem Watermelons (1965) is little known these days.Footnote 1 Tacitly understood as an irrelevant detour and even somewhat questionable misadventure in the composer's development, its status as marginal juvenilia and its unavailability on the market have prevented scholars from taking a serious look at the music and the context within which it was composed. Instead, Edward Strickland's offhand comment on the music and film—“it was the middle of the 1960s”Footnote 2—has stood in the place of a thoroughgoing reconsideration of the music's various social meanings.

More recent discussions of Oh Dem Watermelons have emphasized its role as part of a satirical treatment of historical blackface minstrelsy and as foreshadowing aspects of Reich's mature style.Footnote 3 It is perhaps a little surprising that Reich's work has yet to be brought into conversation with recent writings on blackface minstrelsy in the past decade, as well as high-profile treatments of minstrelsy by black novelists and filmmakers—most famously, Spike Lee in the film Bamboozled (2000).Footnote 4 My aim here, however, is neither to denounce Reich's neglected composition as racist, nor to celebrate it as harnessing the transgressive power of minstrelsy—a power that, according to the cycle theory of minstrelsy, has periodically swept through U.S. history from the era of Jacksonian democracy in the 1830s to the appearance of ragtime, musicals, and jazz in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to the birth of rock and roll in postwar America, and then hip hop as its most recent manifestation.Footnote 5 Instead, I propose three arguments. First, it is my contention that Reich's piece, along with his better-known tape pieces It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966), crystallized a set of aesthetic and conceptual preoccupations with problems of race in the United States, particularly concerning the African American freedom struggles in, and tensions between, the Civil Rights and Black Power/Black Liberation movements. As such, Oh Dem Watermelons (1965) should be placed alongside those two tape compositions as part of a series of “race” works that helped initiate his early compositional style and the musical movement referred to as minimalism; these compositions should be understood as allegorizing processes of liberation. Second, Reich and his collaborators were not unique in reviving blackface minstrelsy and other forms of racial caricature. Rather, several artists, musicians, and comedians were drawing on similar forms in the mid-to-late 1960s, forming a diffuse but interrelated network of creative artists within the San Francisco Bay Area. These artists constitute a “minstrel avant-garde” of sorts, an artistic formation fundamentally linked to the West Coast—and, more broadly, to largely white cultural avant-gardes and bohemian communities of the Baby Boomer generation. At the same time, however, the minstrel avant-garde was made possible by the successes of social movements aiming to remove uncritical forms of minstrelsy from the mass media. The irony was that this avant-garde, like most of the 1960s neo-avant-gardes, was recuperated into the system it so despised, resulting in minstrelsy's reappearance in the public eye with an ironic, postmodern flair that simultaneously mainstreamed the critical power of minstrelsy and returned classic minstrel stereotypes in new forms to mass audiences for consumption. Third, Reich's involvement with the San Francisco Mime Troupe and the Bay Area artistic scene increasingly seems to have become—despite their formative influence on him as a composer—something of an embarrassment for him, and over the years he has attempted to distance himself from most of the work he produced in that period. Although the sensitivity of the subject matter would offer an adequate rationale for Reich's evolving position on his music for Oh Dem Watermelons, the broader aesthetic, political, and social dynamics to which it is tied came to be perceived as impediments to the ascending professional trajectory and artistic acclaim that he has long sought.

The San Francisco Mime Troupe and Alternative Theater in the United States

Born and raised in New York, Steve Reich (b. 1936) left the East Coast to study composition with Luciano Berio and Darius Milhaud at Mills College (1961–63) in Oakland, California. While at Mills, Reich met R. G. Davis (b. 1933), an actor-director working with The Actors’ Workshop. Davis had also started a political theater company in 1959, soon to be called the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Beginning in the silent mime tradition while drawing on populist forms of wordless performance like Charlie Chaplin's silent slapstick films, Davis soon left the Workshop to concentrate full time on his new company, incorporated words into his productions, switched to the sixteenth-century Italian outdoor theater style of commedia dell'arte as the basis for the group's work, and began performing in parks in San Francisco to attract a wide audience. One result of the troupe's increasing prominence in the public sphere was that its members faced censorship and repression from city police and municipal authorities, often on trumped-up charges of lewdness or obscenity. Political battles with city officials in 1965 over permits for performing in public parks, in which Davis was ultimately arrested for leading an unauthorized performance, resulted in the support of the New Left activists and cultural workers in the city and led to the formation of the politically active Artists Liberation Front, in which the troupe was centrally involved.Footnote 6

The Mime Troupe was part of a new movement of alternative and political theater in the United States in the postwar period, including, among others, Julian Beck and Judith Malina's Living Theater (New York, 1951), LeRoi Jones's (a.k.a. Amiri Baraka) Black Arts Theater (Harlem, 1965; later in Newark), Luis Valdez's El Teatro Campesino (San Francisco, 1965), and the Diggers (San Francisco, 1966). The earliest of these groups began from an aestheticist modernism rather than from explicitly political work, but given the proximity of political and social radicalism in much modernist theater and the self-perceived aesthetic radicalism of the prewar avant-gardes, it is unsurprising that new U.S. modernisms of the 1950s eventually were transformed into explicitly political productions and theater companies by the 1960s. Moreover, numerous artists and artistic groups coming primarily from music (Cage, Fluxus, AACM) or dance (Judson Dance Theater) were also involved in new forms of performative expression. These groups were perhaps inspired to imagine a new relation to the body through the real physical engagement in civil disobedience acts in the new social movements of the 1960s and new modes of musical performance in rock music or jazz. Indeed, one might argue that the media manipulation of the New Left in the antiwar movement, in particular the work of the Yippies, might represent a theatricalization of New Left politics.Footnote 7

Instrumental in the alternative theater movement was the production of new works by Bertolt Brecht, the leading light of leftist political theater associated with the communist second world. An English-language Brecht revival had been taking place in the 1950s and early 1960s, marked by a translation of several of his didactic plays in 1961 by Eric Bentley. Bentley imagined his collection, Seven Plays, including Mother Courage (1939), Galileo (1938–39), The Good Woman of Setzuan (1938–40), and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1944–45), as a corrective in response to the growing popularity of Brecht in the postwar years in the English-speaking world. As Bentley notes, “Brecht has died, and what we have chosen to inherit is a cult, an ism. . . . War can be waged on Brechtism in the name of Brecht.”Footnote 8 In addition to an explicit Marxist political commitment, Brecht's work provided clear examples of various performance and theatrical strategies that would prove useful to the practitioners of the new alternative theater in the 1960s, including the time-honored use of parody, or rewriting or lampooning earlier works in light of the present; the notion of coarse thinking (plumpes Denken); the grotesque refiguring of the enemy; a philosophy of performance emphasizing the constructedness of the theatrical scene; and the possibility of demonstration in art, a logical unfolding of a premise that is antisubjective in nature.

Brecht was certainly part of the constellation of figures influencing the Mime Troupe. Perhaps most telling was that Reich, an outsider to political theater, apparently picked up on the influence of Brecht on the troupe: He later described it as “a very left-wing neo-Brechtian kind of street theater in San Francisco.”Footnote 9 Davis repeatedly theorized contemporary theater practices through Brecht—at one point publishing an article with Peter Berg in Drama Review titled “Sartre through Brecht.”Footnote 10 Davis was, however, critical of the idea that Brecht could provide “a simple solution for American political theater” and despised the “innumerable bad productions of Bentley's apolitical versions” of Brecht's plays.Footnote 11 Still, the Mime Troupe director repeatedly returned to Brecht during his tenure with the troupe, producing a version of Exception and the Rule in 1964 and Congress of White Washers in 1969. In both cases Davis wanted to avoid the “European attachment” of Brecht's work generally and instead drew on the East Asian aspects of the plays, allegedly to make them more relevant to the local context of San Francisco. In the earlier production, Davis drew on Japanese theatrical forms (Noh, Kabuki) that had influenced Brecht's theatrical productions generally; in the later production, the Chinese setting of the play inspired its treatment as outdoor Chinese opera.Footnote 12

Reich became involved with the Mime Troupe in part because it had connections to the experimental music scene in the city. Davis attended concerts at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, run by composers Ramón Sender and Morton Subotnick, and staged a theater piece titled “Event II” at the center in January 1963. In 1963 Reich became one of a few experimental composers (including Pauline Oliveros) involved in producing music for the troupe's performances and related films. Between 1963 and 1965, he composed music for a production of Alfred Jarry's proto-Dadaist play Ubu Roi, tape music for films by troupe associate Robert Nelson titled Plastic Haircut and Thick Pucker, music for Molière's Tartuffe and Milton Savage's Ruzzante's Maneuvers, and music with his Mills College colleague and future Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh for Event III (Coffee Break).Footnote 13

The Mime Troupe seemed to provide Reich with a breath of fresh air—in his words it “was just exactly what the doctor ordered after doing an MA [in composition] under Berio and Milhaud [at Mills College].”Footnote 14 Through the avant-gardist and political currents that developed together as part of Davis's vision for the group, the Mime Troupe (and particularly Davis) seems to have been one of the key factors in spurring Reich to tackle politically (and racially) oriented subject matter. Reich's compositions prior to his contact with the Troupe (and the San Francisco New Left and nascent counterculture generally) hardly dealt with the difficult, politically fraught subject matter found in works like It's Gonna Rain or Come Out. Perhaps after arriving in Oakland to study at Mills and perceiving firsthand the continuation of American racial oppression on the West Coast—thus shattering the myths of Californian (racial) utopia that in part may have inspired Reich's transcontinental relocation—Reich may already have been preoccupied with such concerns before meeting Davis.Footnote 15 In any case, Reich's contact with the Bay Area's nascent counterculture helped to spur the composer toward thinking about issues of race and ethnicity, a process that intersected fruitfully with his growing interest in African music, with the nexus of his spiritual/religious explorations and his following of the Civil Rights Movement, and with his longstanding interest in jazz and familiarity with popular music.

The Mime Troupe's A Minstrel Show

Reich's final project with the Mime Troupe was their June 1965 production A Minstrel Show, or Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel. Conceiving of the production in 1964 with Saul and Nina Landau, Davis sought to revive and rethink the historical blackface minstrel show, much in the way that he had done with the commedia dell'arte in prior work—and the use of stereotyped, stock characters was characteristic of both theatrical forms. Unlike the troupe's Italian theatrical model, blackface minstrelsy was an indigenous theatrical form that could facilitate a concrete treatment of race in the United States. According to Eric Lott, nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy not only created stereotypes that justified the existence of slavery, but also created a context in which working-class whites could explore their fascination with black culture and express oppositional, even abolitionist, viewpoints, thus at times providing a space for contesting the dominant racial hierarchies and ideologies.Footnote 16 More than a century later, Davis found himself working at an historical juncture that witnessed the remaking of the post-Reconstruction system of Jim Crow segregation and the birth of militant political strategies for ameliorating the post-migration racial order of the ghetto. During a moment of intense racial conflict within the country—the Civil Rights Movement was splintering and transforming into the Black Power Movement, and some of the earliest of the decade's wave of racial urban uprisings took place in 1964—the actor-director felt it important to confront and explode liberal racism by confronting his audience with the culturally repressed racist tropes of minstrelsy. To this end, he cast the show interracially, so that “the audience would have to struggle through the performance trying to figure out which were black and which were white. The process would unnerve them and fuck up their prejudices.”Footnote 17

The Mime Troupe's production mimicked the sectional or “presentational” form of the historical minstrel show itself. Both borrowing and altering scripts from century-old minstrel shows and introducing newly written material, the troupe not only updated the minstrel show's form but also made it a great deal more subversive, if not outright strange. A Minstrel Show begins with a “tambourine, shoutin’, stompin’, cake-walk for the opener”Footnote 18 that leads into a series of crossfire gag routines between a white, straight-man Interlocutor and individual minstrels. Next is the Stump Speech on Evolution, done by a minstrel “in the style of a [racially ambiguous] Southern senator.” All the minstrels then bowed their heads as the Interlocutor sang “Old Black Joe,” while one of the minstrels begins to furiously simulate masturbation. After a peculiar Nazi-style march sequence, the show resumes with a recounting of “Nego History Week” (without the “r”), which involves a portrayal of black historical figures and ends with militant black nationalists inciting the minstrels to revolt. The Interlocutor calms the minstrels down, asking them to “improvise” a “chick/stud scene.”Footnote 19 Here one of the minstrels acting as a hypersexualized black male figure picks up a liberal white woman at a bar and takes her home to bed. In a postcoital dialogue, these stereotyped characters deflate each other's clichéd statements, thereby “deconstruct[ing]” both stereotypes. The troupe then screens Robert Nelson's short film Oh Dem Watermelons (1965), in which white actors perform numerous violent and bizarre acts upon watermelons (presumably representing African Americans). During the intermission the minstrels sing the Black Muslim song “White Man's Heaven Is a Black Man's Hell,” and blonde female audience members are invited to dance onstage with the minstrels. The second half of the show comprises two short plays. The first was an improvised scene with a kid and cop based on Lieutenant Gilligan's shooting of James Powell in the summer of 1964 in Harlem—the event that initiated the Harlem riots. The second is a bathroom scene written by Landau in which the characters “White,” “Negro,” and “Nigger” appear, with the last character undermining the pretensions of the first two and ultimately threatening to kill them both.Footnote 20

The point of A Minstrel Show was to unearth and then “deconstruct” stereotypes, thus undoing latent racial prejudices. Davis noted that there was a particular logic at work within the show, one that was thought through quite carefully due to the production's sensitive and volatile source material:

The magic of the show was the unearthing of stereotypical images, placing them on stage, making them move rapidly from cornball black jokes (minstrel racism) to radical black (radical puncturing) jokes thus transforming a stereotypical image into a radical image. The speed of the performance and the shift from level to level, cornball to cornstalk, caught prejudices offguard and exposed them. The through line, of course, was the general apprehension about buried prejudices, which the search for the white performers amid the black faces constantly irritated. When the white and black (three of each) performers played the stereotypes exquisitely, people got confused and were likely to go away shaken.Footnote 21

Imagined as a Marxist theatrical experiment, the process at work was a dialectical one, in which the dangerous stereotypes of racist satire and caricature in minstrelsy were progressively transmuted into confrontational images and behavior. In retrospect, the Mime Troupe's approach to the minstrel show was successful on several counts. Drawing on the collective imagination and wit of the participants and research into historical minstrel shows, it produced brilliant material and shocked its audiences. It quickly became known as one of the Mime Troupe's most controversial performances, leading to numerous police busts and arrests while the troupe toured with the show in the Northwest and Canada. As Davis later quipped, “People thought we were on their side, thought it was a civil rights integration show. Not so, we were cutting deeper into prejudices than integration allowed. We poked not at intolerance, but tolerance. We were not for the suppression of differences; rather, by exaggerating the differences we punctured the cataracts of ‘color blind’ liberals, disrupted ‘progressive’ consciousness and made people think twice about eating watermelon.”Footnote 22 Despite the show's anti-integrationist tendencies, it also was the troupe's first use of an interracial cast and U.S. source material and represented an attempt to speak more directly to its (broadening) audiences. Such efforts prefigure the practices of the later, post-Davis collective era of the troupe, which were more community based and accommodating in spirit. Finally, the Minstrel Show provided an opportunity for the participants themselves to examine and learn from their experiences of racial prejudice.

Although the show was intentionally troubling, it also displayed some tendencies that worked against its own aims. Perhaps the most significant of these was the way in which the actors produced a macho environment of racist mudslinging—itself characteristic of the problematic gender dynamics within the Mime Troupe in its pre-feminist years (before 1970). Davis recounts one story in which a talented potential cast member felt uncomfortable with the situation and left the show:

We never did find a permanent third black to match [Willie Hart and Jason Marc Alexander], although, in the early rehearsals, we worked with a great performer who was five feet wide and six feet tall, played piano, could dance and sing, and was a fine actor. He left. The show was merciless and each joke was self-critical. He couldn't stand up to the scrutiny of the form: racism, white or black. He did not dig the politics or the jokes at his size. He would not admit that he was twice the width of any one performer and we found out later that he hadn't noticed he was Negro until the age of twenty-one.Footnote 23

Hence, although there was understandable desire to avoid the solipsism of “fantasy and dream therapy,”Footnote 24 the masculinized radical horizon of the troupe's work at that time could neither tolerate nor represent sensitivity within its boundaries.Footnote 25 Another closely related limitation of the show was its method of puncturing stereotypes, which was typically accomplished by transforming a docile black character into a violent or militant one, often in the spirit of Black Nationalist and Black Arts Movement rhetoric. Because the show was meant to be topical, it did successfully draw upon the transgressive images available to the left at the time—including overt sexuality, masculine black violence, and, in a negative way, Nazi fascism.Footnote 26 The fact that this imagery was subsequently appropriated and manipulated by the right—with the images of sex, racial violence, and fascism both firmly in the service of capital and rightist causes such as the prison industrial complex or the so-called Holocaust industry—can be seen as both a success and a failure. Given that powerful institutions and hegemonic social forces work hardest to adopt, absorb, and nullify images that they find most useful and most threatening, perhaps these images are merely part of a larger political contest over symbols occurring in the wake of the 1960s. On the other hand, the shifting imaginaries associated with these symbols might be linked to the postwar-generation professional-managerial class's shift in social locations or movement from the outside to the inside of powerful institutions—here identified in the cliché of the yippie turned yuppie, or the move from Haight Street to Wall Street.Footnote 27 For his part, Davis has more recently noted that the problematic content of A Minstrel Show must be handled thoughtfully in performance, with differing interpretive approaches varying the degree to which it would be “a racist show or one challenging racism.”Footnote 28

Robert Nelson and Steve Reich's Oh Dem Watermelons: An Analytic Description

Most of the music in A Minstrel Show was provided either by the troupers themselves or by two banjo players in the local folk-revival scene and/or loosely affiliated with the troupe, Carl Granich and Chuck Wiley. Reich's sole musical contribution was an extended canon on the word “watermelon” that was sung live by the troupe during the screening of Nelson's Oh Dem Watermelons, the screenplay for which was written by Saul Landau. Nelson, a San Francisco native born in 1930, was involved in the city's art scene as a painter, first enrolling in a painting class at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) and soon becoming connected to the “funk” tendency of artists and filmmakers in the late 1950s.Footnote 29 Independent cinema was also growing in prominence within San Francisco arts communities thanks to the efforts of Bruce Baillie, who in 1960 formed Canyon Cinema—an exhibition outlet and eventually a collectively run film distribution company that was initially based in the backyards of interested filmmakers and viewers.Footnote 30 Nelson first became involved in filmmaking with his wife, the artist (and later, filmmaker) Gunvor Nelson, beginning with a few home movies in the early 1960s. Around 1963, Nelson began to work with Ron Davis and produced films with him and Reich, sometimes for productions by the San Francisco Mime Troupe, including Plastic Haircut (1963), King Ubu (1963), and later, Oh Dem Watermelons. Nelson recalls that in 1965 Davis asked him to “make a short ‘intermission’ film for A Minstrel Show,” which was already in production. The Mime Troupe paid the production costs, which included “5 or 6 rolls of color film and one dozen watermelons.”Footnote 31

Throughout this period, three artistic entities—the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Canyon Cinema group, and the San Francisco Tape Music Center—often combined forces and in turn facilitated further artistic collaboration. The Mime Troupe was frequently at the center of this activity.Footnote 32 Whether in tandem with the troupe or not, the communal aspect of cultural production was a central theme in Nelson's own films, which are marked by their lighthearted humor and often feature rambling, picaresque adventures undertaken by the filmmakers themselves; as film critic J. Hoberman notes, their “friendship is, in great measure, the subject of their work.”Footnote 33 Indeed, in the case of Oh Dem Watermelons, the charged political impetus of the film emerged directly from Nelson's collaboration with Davis and Landau, making it dissimilar from his other films in this respect—though the characteristic humor and communality remain.Footnote 34

Although Oh Dem Watermelons was typically screened as a part of A Minstrel Show, it also had a separate existence as an experimental film, winning first prize in the “Cinema as Art” category of the San Francisco Film Festival in 1965. Reich's music, though performed live in the show, is relatively well coordinated with the standalone film as a taped soundtrack, and it rubs shoulders with quotations of music by Stephen Foster and a lesser-known songwriter, Luke Schoolcraft.Footnote 35

The autonomous version of the film begins with a credit sequence that includes a ponderous rendition of one chorus of Stephen Foster's classic minstrel song “Massa's in de Cold Ground” (1852) hummed by a men's choir with piano accompaniment (Example 1). At the beginning of the second phrase of the chorus, a low-voiced announcer states, “Music by Stephen Foster and Steve Reich,” and the film cuts to footage of the young Reich (Fig. 1a). The film then shows a man wearing ice skates, carrying a watermelon, walking carefully on a high metal beam attached above to a large highway overpass, and preparing of some kind of explosive; the announcer states, “Bombs by Joe Lomuto,” as the chorus of the song ends. The next scene, which lasts for a minute and a half, features a still shot of a watermelon sitting at an angle in a grassy field, accompanied by silence. Suddenly, a voice announces, “All right everybody, follow the bouncing watermelon!”Footnote 36 On the screen appear the words to Foster's “Massa's in de Cold Ground,” with an animated watermelon bouncing out of sync on top of each syllable (Fig. 1b).Footnote 37 The song is now performed about twice as fast as its earlier tempo (Example 2).

Example 1. Oh Dem Watermelons, credit sequence, hummed version of “Massa's in de Cold Ground.” Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

Example 2. Oh Dem Watermelons, from “All right, everybody” through sung rendition of “Massa's in de Cold Ground.” Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

Figure 1a. Image of Steve Reich in Oh Dem Watermelons (0:33). Image stills from Oh Dem Watermelons used by permission of Robert Nelson.

Figure 1b. The “bouncing watermelon” in Oh Dem Watermelons (2:47).

Without a break, the music and text shift to the chorus of another minstrel song, Luke Schoolcraft's “Oh! Dat Watermelon” (1874), a slightly faster 2/4 tune in the same key.Footnote 38 (See Examples 3 and 4 for the song's original chorus and the troupe's treatment of it.) By the second time through the chorus of “Oh! Dat Watermelon,” the words disappear and the watermelon suddenly transforms into a football, which is kicked by a uniformed football player in a kickoff. By this point the images begin to shift rather frequently, from a stadium and cheerleader shots, to a crowd scene, then to football players looped in action. During the course of these image shifts, the music has mutated from a repetitive, one-note chantlike tune on the phrase “Oh, dat watermelon” (mm. 17–30 in Example 4) that is a variant of the chorus of Schoolcraft's song, into a triple-meter passage in which an altered dominant in D is looped, accompanying the more robotically sung “watermelon, watermelon.” The passage then transforms into a pulsed version of the same music, accompanying a longer sequence involving a group of men chasing a rolling watermelon down an inclined road and playing football with it in a somewhat busy street.

Example 3. Luke Schoolcraft, “Oh! Dat Watermelon” (1874), chorus.

Example 4. Oh Dem Watermelons, Schoolcraft's “Oh! Dat Watermelon” and variation. Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

At this point, the musical accompaniment embarks on a process of expanding from a single-voiced accompaniment to an original multipart canon, with voices entering gradually. The images continue to change and now show greater violence inflicted upon watermelons, which are stomped upon by a person wearing ice skates, sliced with swords and knives, and blown up. One extended passage involves one actor removing animal intestines from a watermelon, apparently disemboweling it (Fig. 2a).Footnote 39 A watermelon is shot; another, already mutilated, pops out of a bus at a bus stop and is further trampled upon by exiting passengers; yet another sequence shows a construction vehicle crushing a watermelon (Fig. 2b). Then ensues a series of exotic scenes—often produced with crudely animated collages—showing watermelons in various contexts, such as being transported on different peoples’ heads (Fig. 2c). Political meetings appear, involving various heads of state—with the watermelons always accompanying black political figures. Watermelons are birthed, become children, are urinated on by a dog, stuffed into a toilet, carried by Superman, and made love to by a young white woman. Stereotypical images of black youths eating watermelons are presented, a watermelon is dropped by a rocket (Fig. 2d), and finally an earlier image of a watermelon being sliced by a sword returns. During the presentation of these quickly cut scenes, the canon has steadily built up to include five voice parts, which are then reduced one voice at a time to a single line, mirroring the earlier entry of the voices. At the end of the film, the opening passage of the group of young men chasing the watermelon down the road is now reversed, and the watermelon appears to fuse spontaneously and chase them up some stairs and the inclined road (Fig. 2e). In the soundtrack, a rousing coda ensues as the music breaks from the canon to arrive on the D major tonic and series of choruses of “Oh! Dat Watermelon,” some of which include obbligato harmonized vocal chants of “Oh, dat watermelon, oh, dat watermelon!” As the coda music continues, the chase scene is juxtaposed with fleeting images of the faces and heads of different African American men. The silent closing scene shows the cameraman (probably Nelson) filming a sticker on a reflective surface (perhaps a car windshield) showing the date and place of the film's creation (California, 1965).

Figure 2a. Disemboweling scene in Oh Dem Watermelons (5:29).

Figure 2b. Construction vehicle crushing a watermelon in Oh Dem Watermelons (6:36).

Figure 2c. Animated collage with African woman carrying watermelon in Oh Dem Watermelons (6:48).

Figure 2d. Upper part of animated rocket releases a watermelon in Oh Dem Watermelons (9:07).

Figure 2e. Watermelon chases men up the stairs in Oh Dem Watermelons (9:23).

Reich's treatment of the minstrel songs and canon is not unlike that of his tape pieces It's Gonna Rain and Come Out, with a clear material/process divide occurring between the minstrel songs (especially Schoolcraft's song) and the canon. The canon's “process” is somewhat less systematic than those found in the tape pieces but still follows a straightforward logic.Footnote 40 At approximately 3:29 in the film, the canon subject setting the lyrics “watermelon, watermelon” appears supported by a “dirty” dominant chord in the accompaniment part. Specifically, the harmony is a V7 chord with alternating fifth and root in the bass in D major but also includes the pitch D4, which clashes pungently with the C-sharp4 just below it (in jazz-harmonic terms, this chord would be a sus4 with an added 3rd; see Example 5a). The canon subject mostly outlines a tonic sonority (D3-A2-C-sharp3-D3), thus clashing slightly with the piano accompaniment but reinforcing the dirty dominant's mild inclusion of tonic harmony owing to the presence of D4 or scale-degree 1. The looping canon is set within a triple-metrical framework that I have notated in 3/2.Footnote 41 At 3:54, Reich (playing the piano) alters the texture from the “oom-pah” or two-step dance accompaniment to a pulsating texture in which the right-hand part (pitches A3-C-sharp4-D4-G4) is repeated continuously. The left-hand part alternates between E3 and A2, each of which are struck twice in succession but syncopated against the pulse of the meter (Example 5b). This effect, which adds an undulating rhythmic quality to the pulses, recalls some of the offbeat syncopations in Ewe drum textures (such as the kagan parts in particular drumming genres such as Gahu and Agbadza).Footnote 42

Example 5. Oh Dem Watermelons, “canon” voices grouped in three-beat cycle. Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

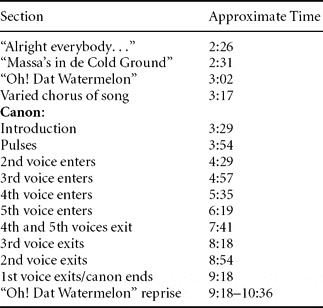

At 4:28, the second voice of the canon enters, with the same lyrics but a third higher and adjusted to continue reinforcing the tonic harmony (F-sharp3-D3-E3-F-sharp3), which now clashes more strongly with the (mostly) dominant-harmony accompaniment (Example 5c). Most importantly, the voice enters on a different beat of the looping canon, on beat 3 of the 3/2, providing a complementary rhythm to the first entry of the subject and filling in all of the empty spaces in the vocal part—and thus in accordance with standard principles of idiomatic canon writing. At 4:57, the third voice enters a third higher on beat 2 of the 3/2, further reinforcing the tonic harmony (A3-F-sharp3-G3-A3)—indeed, one can hear a “resultant pattern” out of the texture in which the word “watermelon” is transposed from A3 to F-sharp3 to D3, outlining a tonic triad (Example 5d). At this point, the musical texture exists wholly within the set metrical structure but articulates different beats such that no particular point is accented (perhaps excepting beats 1, 2, and 3 of the perceived 3/2 meter). The entry of the fourth voice at 5:35 breaks through this logic with a four-beat unit that creates a hemiola with the existing triple-based unit (Example 6a). Singing a new subject, a “Twinkle, Twinkle”‒like descending tetrachord (A3-G3-F-sharp3-E3) to the words of “oh, dat watermelon,” the troupers convey a juvenile, gleeful joy—possibly satirizing the stereotype of African American watermelon-desire. At 6:18, the fifth voice enters one beat later in the 3/2 meter and a fifth higher with the second tetrachordal subject (E4-D4-C-sharp4-B3), providing the point of maximum textural density within the canon (Example 6b). Accordingly, the effect of this oscillating, pulsating music reaches its peak intensity here, owing to the music's complex texture and the way in which the tetrachordal voices appear to be supported harmonically at times by the (mostly) dominant-harmony piano part (especially G3/E4 and E3/C-sharp4) and at times by the tonic harmony of the lower three voices (especially F-sharp3/D4). The music becomes a “shimmer of rhythms,” a thorough fusion of tonic and dominant harmonies, an ambient sea of soothing, mostly comic feeling, in a way analogous to many of Reich's later works.Footnote 43 After sustaining this texture for more than a minute, the voices exit individually by sustaining the final pitches of their canonic subjects for upwards of an entire “measure” before dropping out (see Table 1).Footnote 44 With the exit of the final voice, the music rushes headlong into the big finale, the reprise of the Schoolcraft tune at 9:18.

Example 6. Oh Dem Watermelons, “canon” voices grouped in four-beat cycle. Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

TABLE 1. Sections/Timings in the Oh Dem Watermelon Canon

During the transition from the Schoolcraft song into the canon the music creates the illusion of stopped time. In seizing upon and repeating a suspended-dominant harmony with the same oom-pah texture of “Oh! Dat Watermelon,” the music sounds like a record stuck in a groove.Footnote 45 The canon's material is prepared by the varied repetition of the chorus of Schoolcraft's song that reduces the vocal part to a single pitch, D3. Although the melodic register is maximally compressed at this point, the music still “swings” rhythmically due to its syncopated treatment—giving it a distinctly African American sensibility (see Example 4 above). However, the pitch reduction facilitates a smooth transition into the canon's introduction, which has a completely different effect from the preceding music (see Example 5a). Here the rhythm becomes strict and square, as it were, and the minstrels sing with a robotic tone, making the music appear “frozen” in time. Accompanying this change is the now static repetition of the “dirty dominant” sonority, which appears right before the final perfect authentic cadence of the Schoolcraft song's chorus. Likewise, the hypermeter of the canon's music has augmented: The 2/4 measures grouped in twos in the Schoolcraft song are now grouped in the equivalent of three measures; furthermore, with each original 2/4 unit now constituting a single “beat,” we also experience the effect of a half-time slowdown in the music's basic pulse. Even more importantly, the length of the loop itself (only three beats or twelve “pulses” long) makes the subsequent music less a “canon” and more like a kind of Africanist compositional loop (not unlike a tape loop) in which the complex interrelation of parts repeats endlessly; and in combination with the singers’ robotic tone, Reich's description of his tape pieces as being made up of “little mechanized Africans” perhaps takes on a luridly literal character.Footnote 46 It is worth noting that the stasis and sense of being stuck at this point are reinforced by the film, as the image shows a football player in motion being looped back and forth (Fig. 3). The entire effect makes it seem as if the music has entered an alternate dimension “outside” of time. The entry into this alternate dimension is reinforced when Reich alters the piano texture to pulsing chords—at which point the literal trace of the minstrel song's accompaniment texture has vanished.

Figure 3. Looped football player in Oh Dem Watermelons (3:34).

These observations about the music might profitably be resituated within the broad contours of the film. Given that the film's “soundtrack” was performed live, and that a certain neo-Brechtian aesthetic of Entfremdung governed the whole theatrical production, we might realize that there was a degree of autonomy, as well as unintentional asynchrony, between music and film—as Ron Davis himself put it, “the [cinematic] devices were self evident or made evident. No tricks . . . only knife to the mind.”Footnote 47 (Synchronization problems are most evident during the bouncing-ball section, in which the ball lags behind the sung words by a second or two.) Thus, marking the moment-to-moment interactions of the multimedia here might be less helpful than observing broader tendencies. Specifically, we might ask if the basic structure of the music—minstrel songs/canon/minstrel song reprise—inflects how we perceive the film and vice versa.Footnote 48 If we generalize the film's shifts in content, we can see that, following the silent long take of the watermelon (0:51–2:26), the material accompanying the initial presentation of the minstrel songs (the “bouncing watermelon” encouraging a sing-along, the football, cheerleader, crowd, and stadium shots) bespeaks a certain faux-naïveté, perhaps ironically linking the minstrel songs to wholesome (and largely white) imagery of Cold War America (2:26–3:36). With the appearance of the canon music, however, the sport scene gives way to mock-thuggery (the gang of actors chasing the watermelon down the incline) and eventually to the spectacles of watermelon (mis)treatment and violence. Here, the mechanical groove of the canon seems to reinforce the spectator's voyeuristic interest in what will happen next to some watermelon—indeed, one might think of them collectively as the watermelon, a cartoonish figure with multiple lives. The canon music thus serves as the motor of the viewer's libidinal investment in the long sequence of actions on screen (3:37–9:12), heightening what Laura Mulvey famously referred to as the gaze's “visual pleasure.”Footnote 49 In tandem with the spontaneous reassembly of the watermelon and its subsequent pursuit of the actors (followed by a series of stampede-like shots of running white individuals), the end of the canon and return of the minstrel song convey a powerful sense of closure (9:12–10:35)—perhaps more so than any subsequent piece of Reich's. Indeed, the film's closure effect is largely produced by the music, which resolves the perfect authentic cadence prolonged by the canon with the return of the Schoolcraft song chorus (Example 7). Its embellished repetition—sung spiritedly at full volume—provides an ironically triumphant and even manic conclusion to the events of the film, which, at one level, is a simple parable of the tables being turned or, in Malcolm X's infamous words about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the chickens coming home to roost.

Example 7. Oh Dem Watermelons, ending: “Oh! Dat Watermelon” (reprise). Transcription by author. Used by permission of Steve Reich.

Minstrel Resonances and Reich's Aesthetic Origins

Although the music discussed above may seem somewhat unusual when compared to Reich's more familiar works, aspects of the analytic description should resonate with those relatively familiar with the composer's music. Indeed, representing his first stylistically characteristic composition for live performers, the music for Oh Dem Watermelons is marked by a particular set of musical preoccupations that were worked out over the course of a decade in Reich's first “mature” works and even beyond. The presence of extended or suspended-dominant and quartal harmonies (particularly in Four Organs) and the related abstraction of cadential progressions (arguably in Piano Phase and Four Organs); the African-influenced twelve-beat patterns involving hocketing, layered entry, multiple, noncoinciding downbeats (the A. M. Jones–derived way of understanding African music that was so influential on Reich) and shifting downbeats (as in works such as Drumming Footnote 50 and Music for Pieces of Wood); the pulsing chords of Music for 18 Musicians and other works; and the different phase relationships inherent in canons all point to a similarity with Reich's other work that argues for the piece's inclusion in the Reich canon. As such, Oh Dem Watermelons provides concrete evidence for Reich's often-made statement that his aesthetic trajectory first crystallized after he became involved in the premiere performance of Terry Riley's In C in 1964. Moreover, as Keith Potter notes, Reich performed “‘hand-over-hand piano variations’ on its material with Arthur Murphy, and sometimes [Jon] Gibson, in several of his early New York concerts [in the late 1960s]—and even much later on social occasions, usually under the title Improvisations on a Watermelon, offering ‘a simple shift of accent in a repeating figure, and a gradual expansion of a two-note figure into a five-note one.’”Footnote 51 Although the music in this account seems somewhat different from that for Nelson's film—the main melodic motives of which are four notes (set to “watermelon”) and six notes (“oh dem watermelons”) in length—Reich's initial attachment to, and his gradual distancing from, the composition (first publicly, then even privately) seem evident enough in Potter's historical narration.

Why would Reich want to disassociate himself from his composition, given that it cannot be straightforwardly classified as “juvenilia” (as might be the case, for example, with the collage-based tape music for Plastic Haircut)? An obvious answer is that Reich wanted to avoid future association with this work's sensitive thematic material and, in light of Reich's subsequent rightward political drift, its connections to the radical politics of the San Francisco Mime Troupe.Footnote 52Oh Dem Watermelons, like the Minstrel Show for which it was first created, draws two elements into a potent brew—historical blackface minstrelsy (with its obvious racist stereotypes) and confrontational subject matter (typically, but not exclusively, associated with U.S. race politics and racism in the 1960s)—and audaciously combines them in a blatant form of “cognitive mapping,” whereby present-day racism is figured by past racist aesthetic practices.Footnote 53 In terms of the project's relation to historical minstrelsy, the film and its music, like the Minstrel Show generally, draw on a rather synthetic palette of references that range from the form's earliest days to the contemporaneous moment of the film and music's composition. For example, the two minstrel songs Reich uses come from very different eras in the history of minstrelsy. Whereas Foster's is an antebellum song, associated with the earlier, relatively less demeaning period of minstrelsy (and is even quoted by composers such as Charles Ives and John Alden Carpenter), the post–Civil War minstrel songs of Schoolcraft and others intensified their use of classic stereotypical clichés of black life (like the putatively unique, almost genetic black love of watermelons). That said, the particular narrative of the song sequence reveals that the subject (a slave) in the first song is much more ideologically aligned with the project of slavery—feeling sad that his master is dead and buried—whereas the second song is that of a slave hoping (and actively making efforts to ensure) that his mistress will die so that he might be freed:

In addition to the text of the two explicitly quoted minstrel songs, the film also arguably parodies the sing-along segments of Columbia Records recording artist and A&R chief Mitch Miller's television show, Sing Along with Mitch, a popular, family-oriented show in the 1960s that was described as a “great minstrel show, complete right down to the tambourine”Footnote 55 and that routinely featured sanitized versions of classic minstrel songs, in line with the corniest elements of the folk revival (like the New Christy Minstrels).Footnote 56 Further, the singers perform “Oh! Dat Watermelon” differently from the way it is notated in its nineteenth-century score, replacing the chorus's parlor-song piano texture with a dynamic two-step accompaniment and adding syncopated figures more typical of the cakewalk and ragtime rhythms first popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (compare Examples 3 and 4); the effect is similar to that of an up-tempo gospel song. The singers also ham up their attempts at minstrel dialect, that strange tongue that the African American minstrel comedian Bert Williams described as “a foreign dialect [as much] as that of the Italian.”Footnote 57 In addition to the pronunciation of the text using all of the “de, dat, den” and other (allegedly) Africanized variants on the /th/ consonant, the troupers even added those sounds (or imagined that they did) in places they may not have belonged. As Peter Coyote notes:

The soundtrack . . . was performed live by the company. Three tiers of minstrels seated stage right of the screen sang the words “Wa-DUH-Me-LON, Wa-DUH-Me-LON,” in a four-note round, each tier beginning its “Wa” on the “DUH” of the tier in front of it. The effect was hypnotic, deconstructing the word watermelon into a shimmer of rhythms.Footnote 58

Finally, there seems to be a reference to Foster's “Old Folks at Home” in the credit sequence's hummed version of “Massa's in De Cold Ground”—a scotch snap reminiscent of the ascending melodic minor third (![]() , harmonized by IV) that sets “River” at the opening of “Old Folks” (“Way down upon the Swanee River”)—though it may be unintentional (see Example 1, m. 7). The cumulative effect saturates Reich's score with sonic references to the historical legacy of blackface minstrelsy, encompassing its explicit and repressed variants, particularly as understood by radical artists in the mid-1960s.

, harmonized by IV) that sets “River” at the opening of “Old Folks” (“Way down upon the Swanee River”)—though it may be unintentional (see Example 1, m. 7). The cumulative effect saturates Reich's score with sonic references to the historical legacy of blackface minstrelsy, encompassing its explicit and repressed variants, particularly as understood by radical artists in the mid-1960s.

The Neo-Avant Garde and Two Moments in Oh Dem Watermelons

As the foregoing discussion demonstrates, Reich's musical offering to A Minstrel Show was, in part, an unsparing send-up of minstrel show stereotypes both past and present, one whose willingness to tackle thematic controversy is seemingly unparalleled in Reich's entire career as a composer. Yet Reich's apparent disdain for his work in Oh Dem Watermelons might be somewhat misleading, in that its putative singularity in the composer's oeuvre and its political incorrectness could, from a certain perspective, justify the composer's attempts to excise the work from his compositional history. Thus, to better understand these attempts at historical erasure we might first consider the ways that the subject matter of Oh Dem Watermelons is consonant with that of other works by Reich. Indeed, Oh Dem Watermelons seems neither terribly uncharacteristic in its creative approach nor particularly offensive, at least when viewed and heard critically and sympathetically: Multimedia exploration of multifaceted and politically charged subjects is characteristic of Reich's more recent work as well, particularly his video operas with Beryl Korot, The Cave (1990–93, on Israeli-Palestinian relations) and Three Tales (2002, on the dangers of technology). Although forty years later Reich's political positions may have changed, he does seem to have understood himself consistently as being in solidarity with African American political causes and has often referred to his tape piece Come Out (1966) as a “civil rights piece” (although it is perhaps best understood as a Black Power piece).Footnote 59 The same could be said of Oh Dem Watermelons: Superficially, the watermelon as a “character” or symbol for an African American undergoes a kind of transformation throughout the film, first being defamiliarized in the opening shot (as is the word “watermelon” in Reich's canon), then violated in all sorts of ways, and finally gaining some kind of “agency” by pursuing its former persecutors—offering an allegory of black liberation, as it were. Moreover, in some cases, these acts of violation are explicit references to the violence of the Jim Crow South: The bus episode immediately calls to mind the history of segregation and the movements opposing it, whereas the disemboweled watermelon makes reference to the sadistic violence and bodily mutilation that often accompanied lynchings.

Perhaps, then, the most troublesome aspect of Oh Dem Watermelons for Reich is not necessarily its subject matter, but the sheer irreverence with which it is handled. Indeed, in Davis's words, “What the California [and] San Francisco mode, code, and mood were about” seem to have something to do with this irreverence and a certain aesthetic lightness that are quite at odds with the seriousness of the subject matter in A Minstrel Show and Oh Dem Watermelons. Other, related attempts to describe the San Francisco artistic scene of the early to mid-1960s have emphasized an “openness” absent of “polemical scorn” (including openness to popular music) and a “less intellectually ‘Old World’” and hence “less classist” attitude than the European avant-gardes.Footnote 60 Certainly, these aspects of the San Francisco sensibility may have been articulated with a kind of West Coast (racial) utopianism quite specific to the San Francisco artistic formation of which Davis speaks—which includes the Mime Troupe and other radical theater groups, the filmmakers connected to the Canyon Cinema, the “funk” tendency in West Coast painting and sculpture, the composers circulating through the San Francisco Tape Music Center, the folk revivalist and nascent psychedelic rock scene (including Phil Lesh and Jerry Garcia, eventually of the Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin, among many others), and the more established Beat poets (especially Allen Ginsburg, Neal Cassady, and Gary Snyder) who presided over some of the new developments as elder statesmen of sorts. On the other hand, however, one might also discern a degree of irreverence in the neo-avant-garde generally, particularly the U.S.-based artistic formations that recycled, reimagined, and self-reflexively critiqued the prewar avant-garde's subsumption into art institutions—perhaps in response to the locked-down absurdity of American Cold War consumerism.Footnote 61 If, as Davis notes, the aesthetic formation in which he was involved was “annoying, surprising, and breaking codes,” we may not be surprised if a certain degree of unprofessionalism (indeed, antiprofessionalism) was central to its ethos.Footnote 62 One example might include the technical shortcomings of Robert Nelson's early work and cinematic editing, of which Reich was often quite critical and which led Nelson to perpetually re-edit his celebrated (and messy) works from the 1960s.Footnote 63 Another indicator of such irreverence might be the degree to which U.S. audiences began to expect humorous and sensationalistic amusement from avant-garde performances.Footnote 64

In terms of the music, the most obvious marker of this particular neo-avant-garde formation is the flip treatment of minstrel songs—indeed, aspects of minstrelsy were appropriated by certain tendencies within the U.S.-based neo-avant-garde and counterculture during the 1960s and 1970s. Two rather different musical moments in Oh Dem Watermelons offer analogies to the avant-gardist techniques appropriated by the neo-avant-garde: the transition to the canon and the canon more generally, particularly at its peak of intensity. The first moment might be thought of as “surreal,” the second “sublime.” “Surreal” was a term frequently used by contemporaneous critics to describe Nelson's film.Footnote 65 Indeed, its elements of construction and image juxtaposition are accompanied by a focus on the bodily and physical images reminiscent of surrealism (the disemboweling moment as reminiscent of the slicing of eyeballs in the Dalí-Buñuel film Un Chien Andalou), as well as the body/performance art of Fluxus and other groups in the 1960s. The film's preoccupation with images of African society—in both rural/traditional and postcolonial contexts—and especially collage-based treatments of these (as in Fig. 2c) places it in dialogue with the combination of anthropological fascination and interwar creative practices that James Clifford described as “ethnographic surrealism.”Footnote 66 Indeed, the cutouts and animated images that populate the film draw on another kind of postwar American surrealist and experimental animated cinema, one master of which was filmmaker Harry Smith—also famous for putting together the folk music anthology that would have a huge impact on the folk revival. More capaciously, one can imagine surrealism as having a powerful effect on the aesthetics of the counterculture (itself influenced by the neo-avant-garde): Psychedelic juxtapositions of fantastic imagery arguably owe as much to the precedent of surrealism as they do to mimetic and automatic responses to hallucinogenic experiences.

It is one thing to suggest that Nelson's film may be in dialogue with both aspects of prewar surrealism and postwar U.S. surrealism in its various guises; it is quite another to make claims for the surreal character of the music. For one, the relationship between music and surrealism has long been vexed, its troubles extending back to the origins of the surrealist movement itself—with many of the prominent surrealists (including Breton and De Chirico) finding the medium of music lacking with respect to their aesthetico-political aims and with the best known composers associated with surrealism (Satie, Antheil) being easily assimilated into Dada or futurism.Footnote 67 Additionally, surrealist multimedia projects (films, theater works, operas, ballets) have often involved music that was not necessarily all that “surreal” but made use of surrealist texts (such as Poulenc's operatic setting of Apollinaire's foundational play Les Mamelles de Tirésias)—leading some commentators to lump together many forms of modernist composition under the rubric “surrealism.”Footnote 68 Nonetheless, with these caveats in mind, we may point to some historians who have identified salient features of a surrealist musical aesthetics. Anne LeBaron, for example, cites the compositional practices of automatism (i.e., automatic, or stream-of-consciousness, composition) and collage and argues for the importance of postwar technologies—particularly audio recording.Footnote 69 Drawing on surrealist aesthetics more generally, we might note some of the key themes within the aesthetic discourses on surrealism, which emphasize the importance of combining the dream state with awakedness (which brings the unconscious into a direct relationship with consciousness in seeking to bring unconscious thought to light), the confusion of the identities and properties of objects and the unpremeditated juxtaposition of different realities, the notion of the “marvelous” (merveilleux) as a marker of the fantastic (which Breton describes as being equivalent to the beautiful and yet contains traces of the sublime), and, qualifying LeBaron's emphasis on collage, the continuous nature of surrealist experience.Footnote 70

Clearly, the transition between the minstrel song and the beginning of the canon is a collaged one, in the sense that the end of the one-note D-vamp variation of “Oh! Dat Watermelon” directly abuts the beginning of the canon, which acts as a new musical section of Reich's live soundtrack; here we have the direct juxtaposition of two highly contrasting musical styles, a gospel-like variation on a minstrel song and a mechanical, proto-Reichian pulse minimalism. However, the continuities between the two musical moments—which include the accompanimental (oom-pah) figuration, the pitch content of the material (the D3 monotone in the voices, the A3-D4 dyad in the right-hand part, the low A2 as remaining the lowest note in the texture), the quadratic hypermetrical interruption at the end of the vamp (which leads one, initially, to hear the canon music as continuing a cadence that, in fact, is completed only at the end of the canon), and the syntactical consistency of the lyrics themselves (“Oh, dat watermelon, dat watermelon”)—lead to a smooth transition. Indeed, the arrival of the new material is not immediately apparent, and only in retrospect (albeit soon) does the listener realize that the canon material has overtaken the vamp. Moreover, the music of the canon gets stuck on the word “watermelon” and on a harmony literally “in between” the I and V7 chords used earlier. The listener enters a warped, funhouse world by way of this transition, one that arguably mimics a certain thought process in which normative patterns of cognition are disrupted, and, through a rut of repetitive, quasi-African looping, enters a kind of trance state, and thereby an entirely different cognitive order. This shift in consciousness implied by the transition is, therefore, not unlike the continuous movement between waking and dream states in surrealist aesthetics.

A rather different moment in Reich's music can be identified at the point of greatest intensity during the canon itself, when all of the voices have entered (6:15–7:37). Perhaps surprisingly, a connection to the sublime as a figure for the “limits of reason and expression” or, more specifically, “a feeling for that which lies beyond thought and language”Footnote 71 comes to mind here (see Example 8a and 8b, showing a schematic reduction of the canon and a simplification thereof). Specifically, the fusion of tonic- and dominant-oriented pitch classes in the passage merges in such a way that it produces an effect of comparable magnitude to that of a “salvation 64” or, more accurately, a prolonged, major-mode, cadential dominant arrival characteristic of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century concert music (particularly in developmental retransitions or codas)—and given the use of such a harmony to signify a powerful form of redemptive closure, the perception of the “sublime,” with its quasi-theological associations, is perhaps warranted.Footnote 72 In this case, the sublimity of the experience is mitigated, or at least problematized, by not functioning according to the convention of dominant arrivals or prolongations with which it seems to be in dialogue: Rather than making a grandiose appearance and signaling (impending) victory in a protracted narrative struggle, here the sublime creeps up on the listener unexpectedly, even surreptitiously.

Example 8. Oh Dem Watermelons, reduction of canon, comparison to dominant-prolongation/cadential figure.

Invoking the discourse of the sublime is fraught, because of its long history as a central category of aesthetics and because many have written about it at length, including writers on music.Footnote 73 The locus of interest for our purposes is the post–World War II revival of the term, which includes its appropriation by the U.S.-based neo-avant-garde formation of Abstract Expressionism and especially Jean-François Lyotard's later articulation of a “postmodern sublime.”Footnote 74 Two points are relevant to the present discussion. First, the sublime was originally imagined as being produced through a horrific or otherwise perceptually overwhelming experience of nature and, later in the nineteenth century, was linked to the notion of the unconscious. With the advance of capitalist development and humanity's conquest of the globe (as well as its own mental faculties), however, one might argue that, in the late twentieth century, the postmodern sublime is increasingly an experience produced by the towering, nearly unfathomable aspects of human society itself—from its massive architecture and sprawling cityscapes to the communicative overabundance of information.Footnote 75 Second, the sublime is typically associated with a relatively serious and earnest affective state. Some nineteenth-century authors attempted to understand the sublime in its more ironic and even unserious modalities in various ways, but perhaps they did not entirely resolve the contradiction between the notion of the sublime and playfulness, wit, and humor—between the exalted and the everyday or lowly.Footnote 76

The difficulty of finding appropriate language to understand the “seriousness problem” in what we might describe as the watermelon sublime has much to do with the conflicting signifiers present within the music—just as one hears tropes of the musical sublime during the canon, one simultaneously hears repeated references to a watermelon in the sung text that retain the traces of racialized satire from which they emerged. That said, it is important to pay attention to the processual nature of the sublime effect: As the canon builds up its layers, its sublimity is only apparent as the crowning effect of the addition of the final layer (the fifth voice). It is as if, while listening to a rather elaborate musical joke, a realization of great profundity arises unexpectedly, and thereby associatively transforms the meaning of the word “watermelon” through its juxtaposition with a decontextualized musical convention of sublime affect. The semantic recasting of the word watermelon itself, which in racist humor refers metonymically to the derision and ridiculing of black Americans (although it, of course, also exists organically within black humor), thus provides a different way of dialectically overturning a stereotype and perhaps recalls the watermelon's transition from oppressed victim to radical avenger. Its racist associations temporarily softened, the now-defamiliarized word “watermelon” points in utopian fashion toward its liberated use—whether of anti-white or race-neutral, universal-humanist ilk.

Although the watermelon sublime treads carefully between a charged lightheartedness and unanticipated seriousness—indeed, connecting these affective states through something like a gradual process—the object of perception to which it refers is less ambiguous. Although the watermelon might superficially be linked, via its rural origins, to nature, and although the problem of the stereotype and its associations is squarely located within the unconscious, the object that functions as the sublime referent is the system or the social totality. Indeed, the film reinforces the societal/technological sublime-effect of the canon's buildup, the completion of which coincides (at 6:18) with the appearance of the construction vehicle—perhaps figuring the system itself—and the slow, inexorable descent of its crane-arm, eventually crushing the watermelon (as in Fig. 2b). The specificities of that system, however, can be perceived more clearly when heard through its racialized sonic and musical forms. In addition to the hypostasized cadential dominant discussed above, the buildup of parts within the canon includes a distinct division of labor between the “watermelon, watermelon” parts (which produce a hocketed groove three beats in length) and the “oh dat watermelon” parts (which cycle at four beats). The lower parts appear to fit Reich's previously mentioned description of the “little mechanized Africans” rather explicitly; the machinic nature of the singing, the rhythmic syncopations of the line vis-à-vis the 3/2 meter, and the reiterated pitch (whether on D3, F-sharp3, or A3) of the first “watermelon” lend the music both African and mechanical traits (with the conflation of the two having a long history within Afro-modernisms and exoticisms). In contrast, the upper parts, with their scalar (almost Schenkerian) descents, gleeful vocal delivery, and rhythmic squareness, seem much more “Western,” and, thanks to their distinct temporality, seem relatively distant from the lower parts while at the same time commenting upon them. Racialized as relatively white, the upper parts thus function as relatively powerful (and partly coordinated, partly asynchronous) strata within the figured totality, while the lower parts, racialized as relatively black, function as subordinate (and internally divided, having their own division of musical labor) within that same totality. Implicitly evoking the racialized division of labor and capitalists’ dance of competition and collusion within the Americas and the world system—and hence recalling plantation slavery, debt-peonage sharecropping, and the racialized fractions of labor in the urban and suburban working class—Reich's music offers us an evanescent auditory image of the regimes of accumulation that lurk behind—indeed, produce and reproduce—the watermelon stereotype.

Psychic Liberation and Reich's Aesthetic of the Unconscious

My point in this article, however, is not primarily to relate aspects of Reich's music to earlier aesthetic ideologies or their contemporaneous appropriations and manifestations (though the fingerprints of the neo-avant-garde are certainly unmistakable here), but rather to take note of two moments within the music for Oh Dem Watermelons that appear to highlight different conditions of “consciousness” within the work. The relationships between different sections in the music seem to relate to one another as different modalities of thought or states of being. In particular, the surreal entry into the canon, which then gives way to a sublime vision emerging from the quoted and altered song material prior to the canon, seems to imply a transition between what might be understood as conscious and what might be understood as unconscious—with the “sublime” material akin to either something of a dream state or an altered, heightened state of being that could be heuristically, if somewhat reductively (i.e., fusing the sublime object as nature/unconscious/totality), described as being in contact with the otherwise inaccessible unconscious.

Viewing the relationship between the given material (minstrel songs and gospel- variant) as conscious and the resulting material (canon) as unconscious, transformed through a musical process, allows us to connect Oh Dem Watermelons with Reich's other “race” pieces from his formative 1965–66 period—the tape pieces It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966). Reich's work at this time can be described as operating within an aesthetic of the unconscious, in which given material subjected to a process yields a psychological excavation of that material, producing its “unconscious,” so to speak, for the listener.Footnote 77 The presence of the unconscious is overdetermined in Reich's work, given his descriptions of his pieces as acting like an “oral [or aural] Rorschach test” and given the way in which his tape pieces use preexisting recorded sound and therefore draw on an “auditory unconscious” tied to a technical apparatus. Extrapolating from these examples, the unconscious in question is then twofold, involving both the unconscious of the material—aspects of which are made manifest by the process—and the unconscious of the listener.Footnote 78 The movement from conscious to unconscious (or rather, unconscious-made-conscious) can be described as desublimation. The term is associated with the work of the Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse and refers to the release of repressed and sublimated drives—thereby being a form of regression; desublimation could take place in both repressive (by which he meant recuperable and therefore capable of perpetuating domination) and nonrepressive ways.Footnote 79 For Marcuse, desublimation was inseparable from the notion of “liberation,” a ubiquitous term of the 1960s, referring to various political and social liberation movements—sexual liberation, racial and ethnic liberation, women's liberation, gay liberation, all arguably emerging from the foundational national liberation movements and anticolonial struggles and cresting with the ambitious projects of liberation from capitalism itself, as exemplified in the long moment of 1968—as well as forms of (often non-Western) spiritual liberation not necessarily linked with the previously mentioned movements, with personal liberation of one's own psyche mediating the various forms of collective liberation of both counterculture and New Left.Footnote 80

Reich's works of this period produce allegories of liberation, by illustrating liberation as a process rather than as a given—as might be the case with many other aesthetics bound up with the unconscious, from Abstract Expressionism's painting of the unconscious itself to the ostensibly liberated aesthetic practices of performance art, indeterminate music, “free jazz,” or psychedelic rock.Footnote 81 Whether emerging as a response to a perceived lack of aesthetic discipline in other unconscious-oriented aesthetics or as an aestheticization of personal (and even spiritual or political) discipline, the Reichian process—as per his much-discussed quasi-manifesto “Music as a Gradual Process”—introduces a new, impersonal element into the aesthetic environment whose impact is perceived, over time, as structuring the flow and meaning of the work.Footnote 82 Linked to an analogous aesthetic in the visual arts known as “process art,” Reich's process music combines aspects of earlier, unconscious-oriented aesthetic practices with a kind of (Cagean) formalism and sets the two into a productive, arguably dialectical conflict with one another.Footnote 83 The unfolding of that musical process, mimetically capturing in aesthetic form what Marcuse describes in political terms as a “methodical desublimation,” yields a series of dialectical sound images that can be read and interpreted individually.Footnote 84 The content of this process is, of course, dependent in part on the source material and its interaction with that process, on the one hand, and on the listener or interpreter's perception of the whole, on the other. In the context of Reich's race works, I have viewed the desublimation allegory as largely political, in light of their politically charged source material and suggestive if inchoate sonic results emerging from the specific processes employed. In other words, the Cagean, impersonal “it” of Reich's process in these works acts to figure the System, or the name for the larger social totality that characterized, in contemporaneous thought, the imperialist state-capital nexus.Footnote 85 Hence, the unconscious of these pieces can be best understood from the lens of Fredric Jameson's elusive but productive notion of the political unconscious, allowing us to read the aesthetic psychodynamics of these works as complex political allegories.Footnote 86

Reich's aesthetic of the unconscious connects his work to both contemporaneous preoccupations with psychic liberation and with the aesthetic politics of the neo-avant-garde. The problem of psychic liberation, writ large, is multifaceted and cannot be discussed extensively here, but we should note that, in the context of the United States, it appears to find its roots in the dynamics of repression and affluence in Cold War America. According to Robert Cantwell, who identifies early stirrings toward liberation in the apolitical aspects of the Folk Revival,

The collectivizing, rationalizing, scientizing, and regimenting influences of that [postwar] environment amounted to the appropriation by the commercial, educational and other establishments of what nature had given them most to enjoy, their own youth. To be young and middle-class in the postwar environment was not only to have your sexuality reduced to an elaborate set of prohibitions, exclusions, obsessions, and petty neuroses, but at the same time to have your sexual identity commodified, coarsened, and puerilized. To be young and female in the early sixties meant, in effect, to transform yourself into a rubber doll with plastic hair, purely a factory product; to be young and male demanded a practiced hypocrisy that sanctified women and at the same time demanded sexual conquests whose purpose was to provide materials for the minutely detailed narratives, graphic boasts, and outrageous claims familiar in men's dormitories.Footnote 87

Describing the experiences of middle-class white American baby boomers in the postwar era, Cantwell offers a vivid picture of what Marcuse meant by “repressive desublimation,” but deals with the problem of racism as primarily one of a search for authenticity, usually found in African American and/or white rural cultural practices. However, as the Baby Boomer generation came of age during the 1960s, its members became increasingly aware of the problems of their own internalized racism, primarily as a result of the Civil Rights and then Black Power/Black Liberation movements and through powerful accounts of the psychological effects of racism, as in the work of Frantz Fanon. Later in the decade and at the beginning of the next, various political attempts at a racially oriented psychic liberation attracted attention, including the radical-adventurist political efforts of the White Panther Party and the infamous Weatherman faction of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), as well as more clearly reformist attempts to undertake white-on-white political and labor organizing in Appalachia and the southern United States. Among the best-known theoretical texts of the time addressing the problem of whites’ internalized racism was psychotherapist Joel Kovel's White Racism: A Psychohistory (1970), which produced a number of categories for the historical (and, implicitly, self-) diagnosis of racism and drew explicitly upon Marcuse's work.Footnote 88

The problem of racial-psychic liberation thus connects Reich's musical allegories to the critique and puncturing of racist stereotype in the Mime Troupe's A Minstrel Show and Nelson's Oh Dem Watermelons, with the production clearly seeming ahead of the curve when assessed with respect to its contemporaries. Indeed, in Davis's view psychic liberation was understood to be central not only for the audience but also for the actors. In exploring performers’ background experiences with the ironies and complexities of racism, Davis sought to create a communal understanding of race and racism necessary to produce a coherent political perspective for the show. As he notes,

In addition to our social analysis, we had to deal with the personal liberation of each actor; not only to incorporate some material we might find in each performer but also to make sure that the individuals would present the collective point of view. I asked each actor to talk privately into a tape recorder about the time he first realized his black, white or ethnic identity. We learned a lot. Jason [Marc Alexander] and Willie [Hart] had torturous early experiences. Willie saw his father run across the path of a milk truck. The driver, furious that he almost hit the man, yelled out: “You fuckin’ nigger. . . .” His father didn't say anything. Marc Alexander lived with his mother, who was a mammie to some white kids. He went to play with the black kids down the road and they threw him in a box and called him “whitey,” while they kicked the box around. Don Pedro Colley, at twenty-one, walked into a dining room in some college in Oregon and didn't sit at the table with all the blacks, but with the whites. They pointed to the black table. White-Spanish-descent kid, Julio Martinez, said, “We were never prejudiced against Negroes. Of course, we were never taken for Negroes.”

All of us heard these important “coming-of-age moments.” Those who had realized early their skin color or ethnic origins understood our show and created its whip-like intensity. Performers who had not experienced the existential racial twist until very late never stayed on for long.Footnote 89

For Nelson, the problem of the unconscious was central to his work, in the frequent employment of themes of sexual frustration and masturbation, in the use of formal framing and dream sequences that figure the movement into and out of different states of consciousness, and in the ambiguity of political perspective and even subject matter.Footnote 90 On the last point, Nelson himself discussed the relationships between stereotype, racial repression, and imaginative projection in Oh Dem Watermelons as follows: