To highlight practical implications and future directions, we discuss the potential application of Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) ethical dilemmas to professional ethics training and education, exploring relevant challenges in identifying training needs and evaluating training effectiveness. When relevant, we highlight examples from our experience with designing, facilitating, and evaluating professional ethics training for mechanical engineering students (see Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b).

Identifying professional ethics training needs

Designing an effective training program should begin with a needs analysis to determine who to include, which content to teach, and whether to use training (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuncel, Kostal, Ones, Anderson, Viswesvaran and Kepir Sinangil2018; Salas et al., Reference Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger and Smith-Jentsch2012). However, unique challenges arise in identifying individuals who need professional ethics training. Most people believe they are more ethical than the average person (Prentice, Reference Prentice2014). As a result, individuals may resist their need for ethics training. Given the importance of self-efficacy and motivation for effective training (e.g., Colquitt et al., Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000), a better understanding of this problem is crucial. Prentice (Reference Prentice2014) proposed several recommendations to address this by increasing awareness of cognitive flaws and external factors that distort individuals’ attempts to behave appropriately. Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) study in the I-O psychology field provides an example of research that could support these strategies. For example, empirical estimates of prevalence rates can help teach trainees how likely it is for them to end up in an ethical dilemma by showing how often other people find themselves in difficult dilemmas. We have seen this phenomenon in our professional ethics training program for engineering students (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). Interestingly, many of the trainees reported thinking that being an ethical professional was simple prior to training but acknowledged that it was more difficult than originally thought posttraining, suggesting that training can help make expectations more realistic.

Identifying training content presents another challenge. But, there is no well-established way to prioritize ethical training content. For example, one could target the dilemmas that occur most often in a given profession or the conduct that causes the worst harm. As mentioned, Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy provides a useful framework for measuring prevalence rates. On top of this, the taxonomy can help categorize which dilemmas produce the most harmful consequences. Such research could inform prioritization of ethical training content.

Similarly, many training efforts that target dilemmas use Rest’s (Reference Rest1986) model as a guiding framework, which denotes content targeting conscious and controlled processes. However, there is ample evidence that shows that ethically relevant conduct can also occur more automatically and impulsively (e.g., Haidt, Reference Haidt2001; Prentice, Reference Prentice2014; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2006). This contrast raises several questions in relation to identifying training content needs. For example, is automatic or controlled processing more frequent or harmful in ethical conduct? Which dilemmas trigger automatic rather than controlled processes and vice versa? How often do individuals consciously realize they are in an ethical dilemma early enough to invoke skills learned in ethics training? Is it possible to make automatic ethical processes more controlled through training? To aid application of Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy to identifying training content, researchers should seek to thoroughly answer these questions.

An implicit uncertainty in the broader framework into which Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2021) inserts his taxonomy of dilemmas involves deciding the appropriate level of dilemma specificity. Perhaps, the profession-specific, manifest dilemmas guide professional ethics training content better than the broader, generalizable dilemmas presented in the focal article. Case-based training programs that used moderately complex cases showed greater effectiveness than high- or low-complexity cases (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Medeiros, Mulhearn, Steele, Connelly and Mumford2017). With that said, field-general practice opportunities produced larger effects than field-specific opportunities. Even if specific dilemmas better lend themselves to training, the cross-domain dilemmas could provide an organizing framework for meta-analyses of professional ethics training effectiveness. Nonetheless, further research is needed to determine how to best apply each level of the model.

Part of the purpose of a needs analysis is also to determine whether training is even an appropriate solution. In the context of professional ethics training and education, this includes consideration of which scenarios or behaviors can be affected by training interventions. Some situations are less dependent upon individual differences and abilities. For example, the moral intensity of a situation exhibits a much stronger relationship (i.e., ρ = .75) to unethical intent and behavior than do commonly examined individual difference antecedents (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). This suggests that morally intense situations could more clearly signal ethical implications, such that the correct conduct is obvious, and training is less important. Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) conceptualization of ethical dilemmas seems to align with less morally intense situations because it incorporates an element of ambiguity in the appropriate response. However, future research should examine how these dilemmas relate to factors, such as moral intensity, which may make them less applicable to training.

Evaluating professional ethics training and education

To continually improve training approaches to professional ethics, organizations and practitioners need to systematically implement and evaluate their training programs. As noted, Lefkowitz’s taxonomy could provide an organizing framework for such endeavors. Nonetheless, evaluation requires measurement of criteria. The end objective of professional ethics training and education is to positively affect behavior on the job and in the profession. However, ethics training programs seem less capable of improving behavior relative to cognitions (e.g., Waples et al., Reference Waples, Antes, Murphy, Connelly and Mumford2009). In addition, evidence suggests a weak link between ethical cognition and behavior (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). The problem may, in part, stem from challenges in conceptualization of unethical work behavior. Existing definitions are limited and overly broad (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Reynolds and Treviño2020). Despite that, custom-designed, field-specific criteria showed larger effects than off-the-shelf general measures (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Medeiros, Mulhearn, Steele, Connelly and Mumford2017). To address this, there are several relevant complexities in the conceptualization of unethical behavior that scholars could examine, including mental state, actor level of analysis, conflicting stakeholder standards, and consequences.

Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) discussion of corruption in relation to ethical dilemmas suggests mental state likely has important implications. Intentional unethical behavior may warrant a different training approach than does response to symmetric dilemmas. For example, individuals who are intentionally unethical may respond poorly to ethics training in general, unless the training effectively targets motives. On the other hand, negligent conduct may emphasize more trainable individual differences such as those that facilitate awareness, alertness, and cautiousness. Likewise, our preceding discussion of automatic and controlled processes further suggests differential implications of mental states. However, some definitions of unethical work behavior require intentional conduct, whereas others do not (Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). In the closely related fields of criminal and tort law, variations in mental state influence the perceived severity and resulting punishment of violations. To our knowledge, no conceptualizations of unethical behavior account for more nuanced fluctuations in mental state, such as negligence and recklessness. Because intentional misconduct can take the situation beyond the scope of Lefkowitz’s taxonomy, better scientific understanding of these “less-than-intentional” mental states seems especially relevant for applying this framework to training and education.

Additionally, professional conduct is inherently multilevel (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). Unethical employees rarely work alone (Pearsall & Ellis, Reference Pearsall and Ellis2011), and workplace misconduct is contagious (Brock Baskin et al., Reference Brock Baskin, Gruys, Winterberg and Clinton2020). This suggests emergence at higher levels of analysis (see O’Boyle et al., Reference O’Boyle, Forsyth and O’Boyle2011). Therefore, the level of the entity engaging in unethical behavior has important implications. Indeed, higher level misconduct (e.g., organization-level pollution) would appear to be more dangerous. Many of the scenarios used in our ethics training for engineers involved organizational-level harm (e.g., manufacturing flaws) on individuals (e.g., consumers; Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). However, scholars have not yet offered cross-level conceptualizations of unethical work behavior. Consequently, research on group- and organizational-level misconduct is less developed (e.g., Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008). Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy seems more geared toward individual-level actors. However, expanding the framework to higher levels would help contribute to a better understanding of the multilevel nature of unethical behavior and the associated training strategies. Reciprocally, a cross-level conceptualization of unethical behavior could also inform application of the taxonomy to higher actor levels.

Ethical behavior involves compliance with a normative standard (Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). However, this standard can derive from various stakeholders such as professions, organizations, communities, and society. In some situations, these standards can conflict for any individual actor. For example, I-O psychologists commonly work in roles in which multiple normative standards and professional ethics codes could come into conflict. Indeed, ambiguity in standards has sparked empirical investigation of constructs like “unethical pro-organizational behavior” (e.g., Umphress et al., Reference Umphress, Bingham and Mitchell2010). The legal context also shapes standard conflicts. For example, the law sometimes directs organizations and top leaders away from ethical objectives. Some organizational decision makers have a fiduciary duty to prioritize profit above all else, including over responsible professional conduct (e.g., Gamble, Reference Gamble2019). Similarly, Winterberg (Reference Winterberg2020) highlighted the need to consider the effects of legal frameworks that put organization and trainee interests in conflict. Robin (Reference Robin2006) attempted to align business objectives with ethical objectives by recommending fair and respectful pursuit of profit. Scholars should expand on this and carefully investigate how best to align various standards within dilemma categories and how to resolve discrepancies.

In our engineer ethics training, we used cross-profession conflicts in standards to create an ethical dilemma experience for trainees. Specifically, trainees role-played as a crash reconstruction expert witness in a mock vehicle accident lawsuit. Facilitators played the hiring attorneys. The attorneys’ priorities were zealous advocacy of clients and the engineers’ objectives were to retain impartiality. Because the expert witness was to work for the attorney, trainees commonly experienced Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) role conflict dilemma. Thus, a precise mapping of stakeholder standards for each dilemma would greatly advance professional ethics training and education by structuring necessary criteria.

Professional ethics is concerned with preventing harm. Many ethics codes, including for psychologists, incorporate an obligation not to cause harm (e.g., the welfare metadimension). In certain ethical situations (e.g., opportunity-to-prevent-harm dilemmas), one entity stands to benefit while another stands to suffer harm, and the actor must choose which stakeholder to harm. In our engineering ethics training, trainees had to choose among harming the victims, the defendants, and the attorneys (see Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). Evidence suggests that coworkers perceive inappropriate physical actions as more harmful than other forms of misconduct, such as attendance problems, and that perceived harm of misconduct plays a significant role in whether people report others’ bad behavior (Brock Baskin et al., Reference Brock Baskin, Gruys, Winterberg and Clinton2020). However, coworkers only provide one stakeholder perspective, and existing frameworks do not account for temporal factors. For example, some misconduct may bring immediate benefits (e.g., increased profit) but cause long-term harm (e.g., a damaged reputation). A more nuanced way to conceptualize harm severity across specific actions, stakeholders, and periods may therefore be beneficial in training professionals to be more aware of the consequences of their actions.

Finally, a more specific conceptualization of unethical work behavior would further guide the application of Lekfowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy to professional ethics training and education by setting a precise framework for identifying ideal responses to dilemmas. Indeed, a necessary question that is not answered in the focal article involves the desired or ideal conduct in response to each dilemma. This issue is further complicated by the fact that no single entity has legitimate authority to independently decide the proper response. Thus, scholars should devote attention to the process of deciding the appropriate behavioral response to various dilemmas. The stakeholders establishing a normative standard may provide a useful initial source of information.

Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2021) offers a valuable contribution to the study of professional ethics by providing structure to ethical dilemmas that individuals might face in their careers. We expand on this base with a discussion on implications and practice-oriented future directions. Specifically, a scientifically grounded taxonomy of ethical dilemmas can serve as a framework for advancing professional ethics training and education in prioritizing training needs and organizing evaluative criteria. Rest (Reference Rest1986) proposed that ethical conduct progresses through four stages: recognizing the dilemma, making a decision, establishing intent, and then acting. A taxonomy of ethical dilemmas should directly inform training that is focused on the first two stages and indirectly inform the remaining stages (e.g., Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Simmons, Brummel and Entringer2016). Although ethics training in the sciences has improved in effectiveness since 2007 (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Medeiros, Mulhearn, Steele, Connelly and Mumford2017), applying an ethical dilemma framework into practice is not easy. Learning the taxonomy alone is not likely to change ethical behavior. Despite decades of interdisciplinary research on ethics, training applications have been relatively underexamined. There are still major scientific gaps to fill to advance professional ethics training and education in any profession, including industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology.

Select challenges for professional ethics training and education

To highlight practical implications and future directions, we discuss the potential application of Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) ethical dilemmas to professional ethics training and education, exploring relevant challenges in identifying training needs and evaluating training effectiveness. When relevant, we highlight examples from our experience with designing, facilitating, and evaluating professional ethics training for mechanical engineering students (see Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b).

Identifying professional ethics training needs

Designing an effective training program should begin with a needs analysis to determine who to include, which content to teach, and whether to use training (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuncel, Kostal, Ones, Anderson, Viswesvaran and Kepir Sinangil2018; Salas et al., Reference Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger and Smith-Jentsch2012). However, unique challenges arise in identifying individuals who need professional ethics training. Most people believe they are more ethical than the average person (Prentice, Reference Prentice2014). As a result, individuals may resist their need for ethics training. Given the importance of self-efficacy and motivation for effective training (e.g., Colquitt et al., Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000), a better understanding of this problem is crucial. Prentice (Reference Prentice2014) proposed several recommendations to address this by increasing awareness of cognitive flaws and external factors that distort individuals’ attempts to behave appropriately. Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) study in the I-O psychology field provides an example of research that could support these strategies. For example, empirical estimates of prevalence rates can help teach trainees how likely it is for them to end up in an ethical dilemma by showing how often other people find themselves in difficult dilemmas. We have seen this phenomenon in our professional ethics training program for engineering students (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). Interestingly, many of the trainees reported thinking that being an ethical professional was simple prior to training but acknowledged that it was more difficult than originally thought posttraining, suggesting that training can help make expectations more realistic.

Identifying training content presents another challenge. But, there is no well-established way to prioritize ethical training content. For example, one could target the dilemmas that occur most often in a given profession or the conduct that causes the worst harm. As mentioned, Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy provides a useful framework for measuring prevalence rates. On top of this, the taxonomy can help categorize which dilemmas produce the most harmful consequences. Such research could inform prioritization of ethical training content.

Similarly, many training efforts that target dilemmas use Rest’s (Reference Rest1986) model as a guiding framework, which denotes content targeting conscious and controlled processes. However, there is ample evidence that shows that ethically relevant conduct can also occur more automatically and impulsively (e.g., Haidt, Reference Haidt2001; Prentice, Reference Prentice2014; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2006). This contrast raises several questions in relation to identifying training content needs. For example, is automatic or controlled processing more frequent or harmful in ethical conduct? Which dilemmas trigger automatic rather than controlled processes and vice versa? How often do individuals consciously realize they are in an ethical dilemma early enough to invoke skills learned in ethics training? Is it possible to make automatic ethical processes more controlled through training? To aid application of Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy to identifying training content, researchers should seek to thoroughly answer these questions.

An implicit uncertainty in the broader framework into which Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2021) inserts his taxonomy of dilemmas involves deciding the appropriate level of dilemma specificity. Perhaps, the profession-specific, manifest dilemmas guide professional ethics training content better than the broader, generalizable dilemmas presented in the focal article. Case-based training programs that used moderately complex cases showed greater effectiveness than high- or low-complexity cases (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Medeiros, Mulhearn, Steele, Connelly and Mumford2017). With that said, field-general practice opportunities produced larger effects than field-specific opportunities. Even if specific dilemmas better lend themselves to training, the cross-domain dilemmas could provide an organizing framework for meta-analyses of professional ethics training effectiveness. Nonetheless, further research is needed to determine how to best apply each level of the model.

Part of the purpose of a needs analysis is also to determine whether training is even an appropriate solution. In the context of professional ethics training and education, this includes consideration of which scenarios or behaviors can be affected by training interventions. Some situations are less dependent upon individual differences and abilities. For example, the moral intensity of a situation exhibits a much stronger relationship (i.e., ρ = .75) to unethical intent and behavior than do commonly examined individual difference antecedents (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). This suggests that morally intense situations could more clearly signal ethical implications, such that the correct conduct is obvious, and training is less important. Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) conceptualization of ethical dilemmas seems to align with less morally intense situations because it incorporates an element of ambiguity in the appropriate response. However, future research should examine how these dilemmas relate to factors, such as moral intensity, which may make them less applicable to training.

Evaluating professional ethics training and education

To continually improve training approaches to professional ethics, organizations and practitioners need to systematically implement and evaluate their training programs. As noted, Lefkowitz’s taxonomy could provide an organizing framework for such endeavors. Nonetheless, evaluation requires measurement of criteria. The end objective of professional ethics training and education is to positively affect behavior on the job and in the profession. However, ethics training programs seem less capable of improving behavior relative to cognitions (e.g., Waples et al., Reference Waples, Antes, Murphy, Connelly and Mumford2009). In addition, evidence suggests a weak link between ethical cognition and behavior (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). The problem may, in part, stem from challenges in conceptualization of unethical work behavior. Existing definitions are limited and overly broad (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Reynolds and Treviño2020). Despite that, custom-designed, field-specific criteria showed larger effects than off-the-shelf general measures (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Medeiros, Mulhearn, Steele, Connelly and Mumford2017). To address this, there are several relevant complexities in the conceptualization of unethical behavior that scholars could examine, including mental state, actor level of analysis, conflicting stakeholder standards, and consequences.

Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) discussion of corruption in relation to ethical dilemmas suggests mental state likely has important implications. Intentional unethical behavior may warrant a different training approach than does response to symmetric dilemmas. For example, individuals who are intentionally unethical may respond poorly to ethics training in general, unless the training effectively targets motives. On the other hand, negligent conduct may emphasize more trainable individual differences such as those that facilitate awareness, alertness, and cautiousness. Likewise, our preceding discussion of automatic and controlled processes further suggests differential implications of mental states. However, some definitions of unethical work behavior require intentional conduct, whereas others do not (Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). In the closely related fields of criminal and tort law, variations in mental state influence the perceived severity and resulting punishment of violations. To our knowledge, no conceptualizations of unethical behavior account for more nuanced fluctuations in mental state, such as negligence and recklessness. Because intentional misconduct can take the situation beyond the scope of Lefkowitz’s taxonomy, better scientific understanding of these “less-than-intentional” mental states seems especially relevant for applying this framework to training and education.

Additionally, professional conduct is inherently multilevel (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). Unethical employees rarely work alone (Pearsall & Ellis, Reference Pearsall and Ellis2011), and workplace misconduct is contagious (Brock Baskin et al., Reference Brock Baskin, Gruys, Winterberg and Clinton2020). This suggests emergence at higher levels of analysis (see O’Boyle et al., Reference O’Boyle, Forsyth and O’Boyle2011). Therefore, the level of the entity engaging in unethical behavior has important implications. Indeed, higher level misconduct (e.g., organization-level pollution) would appear to be more dangerous. Many of the scenarios used in our ethics training for engineers involved organizational-level harm (e.g., manufacturing flaws) on individuals (e.g., consumers; Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). However, scholars have not yet offered cross-level conceptualizations of unethical work behavior. Consequently, research on group- and organizational-level misconduct is less developed (e.g., Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008). Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy seems more geared toward individual-level actors. However, expanding the framework to higher levels would help contribute to a better understanding of the multilevel nature of unethical behavior and the associated training strategies. Reciprocally, a cross-level conceptualization of unethical behavior could also inform application of the taxonomy to higher actor levels.

Ethical behavior involves compliance with a normative standard (Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). However, this standard can derive from various stakeholders such as professions, organizations, communities, and society. In some situations, these standards can conflict for any individual actor. For example, I-O psychologists commonly work in roles in which multiple normative standards and professional ethics codes could come into conflict. Indeed, ambiguity in standards has sparked empirical investigation of constructs like “unethical pro-organizational behavior” (e.g., Umphress et al., Reference Umphress, Bingham and Mitchell2010). The legal context also shapes standard conflicts. For example, the law sometimes directs organizations and top leaders away from ethical objectives. Some organizational decision makers have a fiduciary duty to prioritize profit above all else, including over responsible professional conduct (e.g., Gamble, Reference Gamble2019). Similarly, Winterberg (Reference Winterberg2020) highlighted the need to consider the effects of legal frameworks that put organization and trainee interests in conflict. Robin (Reference Robin2006) attempted to align business objectives with ethical objectives by recommending fair and respectful pursuit of profit. Scholars should expand on this and carefully investigate how best to align various standards within dilemma categories and how to resolve discrepancies.

In our engineer ethics training, we used cross-profession conflicts in standards to create an ethical dilemma experience for trainees. Specifically, trainees role-played as a crash reconstruction expert witness in a mock vehicle accident lawsuit. Facilitators played the hiring attorneys. The attorneys’ priorities were zealous advocacy of clients and the engineers’ objectives were to retain impartiality. Because the expert witness was to work for the attorney, trainees commonly experienced Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) role conflict dilemma. Thus, a precise mapping of stakeholder standards for each dilemma would greatly advance professional ethics training and education by structuring necessary criteria.

Professional ethics is concerned with preventing harm. Many ethics codes, including for psychologists, incorporate an obligation not to cause harm (e.g., the welfare metadimension). In certain ethical situations (e.g., opportunity-to-prevent-harm dilemmas), one entity stands to benefit while another stands to suffer harm, and the actor must choose which stakeholder to harm. In our engineering ethics training, trainees had to choose among harming the victims, the defendants, and the attorneys (see Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Brummel and Daily2017a, Reference Kerr, Winterberg, Daily and Brummel2017b). Evidence suggests that coworkers perceive inappropriate physical actions as more harmful than other forms of misconduct, such as attendance problems, and that perceived harm of misconduct plays a significant role in whether people report others’ bad behavior (Brock Baskin et al., Reference Brock Baskin, Gruys, Winterberg and Clinton2020). However, coworkers only provide one stakeholder perspective, and existing frameworks do not account for temporal factors. For example, some misconduct may bring immediate benefits (e.g., increased profit) but cause long-term harm (e.g., a damaged reputation). A more nuanced way to conceptualize harm severity across specific actions, stakeholders, and periods may therefore be beneficial in training professionals to be more aware of the consequences of their actions.

Finally, a more specific conceptualization of unethical work behavior would further guide the application of Lekfowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) taxonomy to professional ethics training and education by setting a precise framework for identifying ideal responses to dilemmas. Indeed, a necessary question that is not answered in the focal article involves the desired or ideal conduct in response to each dilemma. This issue is further complicated by the fact that no single entity has legitimate authority to independently decide the proper response. Thus, scholars should devote attention to the process of deciding the appropriate behavioral response to various dilemmas. The stakeholders establishing a normative standard may provide a useful initial source of information.

Conclusion

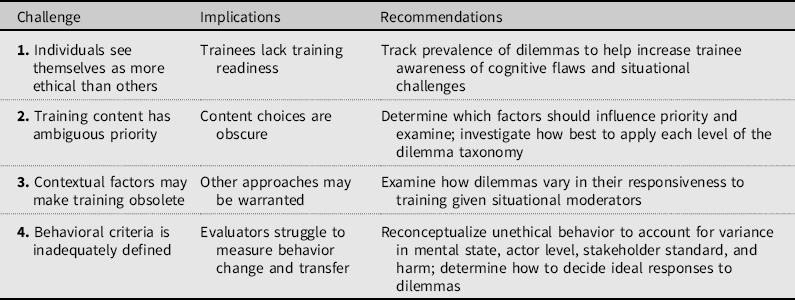

We explored some remaining challenges in applying an ethical dilemma taxonomy to identifying needs for and evaluating the effectiveness of professional ethics training and education. I-O psychology has much to offer in this space if we embrace the research area and the potential need within our own field. Ethics training programs for our members would be a great laboratory for answering some of these questions. We leave readers with a summary of aligned recommendations to help shape future directions toward improved professional ethics interventions (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Challenges, Implications, and Recommendations