Our understanding of how and why federal systems exhibit diverging trajectories is still limited. Scholars have advocated different explanatory factors so as to account for federal system dynamics, most notably territorial cleavages (for example, Erk, Reference Erk2007; Livingston, Reference Livingston1956), ideas (Burgess, Reference Burgess1995, Reference Burgess2006), parties (Filippov et al., Reference Filippov, Ordeshook and Shvetsova2004; Riker, Reference Riker1964) as well as institutional characteristics (Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2006; Cairns, Reference Cairns1977; Thorlakson, Reference Thorlakson2003, Reference Thorlakson2007). This paper argues that historical institutionalism offers a valuable meta-theoretical approach capable of overcoming the shortcomings resulting from the isolation of one explanatory factor at the expense of others. In particular, as historical institutionalism puts emphasis on the historical construction of both institutions and ideas when accounting for political dynamics, it is suggested that it bears considerable potential to address important research questions raised in the literature on comparative federalism.

In order to assess the value of this approach to the analysis of federal system dynamics, the paper proceeds in three steps. First, it demonstrates how federalism can be conceptually reformulated as a multilayered political order, comprising an institutional and an ideational layer. Second, it introduces two models of change, the model of path dependence and the process sequencing model, both providing different types of historical explanation. Finally, the paper tests how each model can contribute to explaining the evolution of the two federal orders in Canada and Germany. Most generally, it arrives at the conclusion that whereas the model of path dependence lends itself well to explaining the federal system dynamics in Germany, the Canadian case is more vexing. Even though the federal order in Canada exhibits certain path dependent dynamics as well, unlike in Germany these path dependencies have never promoted inertia or fostered the status quo. It is argued, therefore, that beneath the level of a path dependent institutional core, the federal order in Canada has exhibited dynamics which can better be explained by the process sequencing model with its emphasis on frictions and cyclical sequences.

I. Federalism as a Multilayered Political Order

Tracing federal system dynamics presupposes clarifying two conceptual questions. First, it is necessary to specify what dimension of federalism is assumed to be subject to change and, second, what direction political change is about to take (Colino, Reference Colino, Erk and Swenden2010).

Conceptualizing federalism as a multilayered order can be valuable in discerning different dimensions of federalism. The notion of political order has played an increasingly prominent role in the literature on American political development (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2002; Orren and Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2004). At the heart of this variant of historical institutionalism is a recognition that political change takes place in a multilayered context comprising, for example, formal institutions, informal routines and modes of governance as well as ideological and cultural repertoires that legitimate authority structures (Falleti and Lynch, Reference Falleti and Lynch2009; Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2002: 703). In the case of a federal political order, two contextual layers are of particular importance: institutional and ideational layers. First, federalism always manifests itself in some form of institutional arrangement that allocates authority and power resources between territorial units which either had previously been independent or barely existed. Institutional approaches to the study of federalism have traditionally been preoccupied with this dimension of a federal order. Second, and more in accordance with sociological and ideational approaches, the notion of a multilayered federal order needs to be reponsive to the role of cultural meanings and scripts. The ideational layer therefore signifies that the allocation of political authority as set out in the institutional layer cannot be isolated from legitimatory frameworks or federal “visions” that may justify or challenge its distributional consequences.

Distinguishing institutional and ideational layers thus allows us to grasp what exactly changes within a federal order. As federal systems empirically vary in their institutional architecture as well as in the way political actors frame discourses on the appropriateness and legitimacy of these federal arrangements, it is further necessary to systematically demarcate possible directions of change. What is needed is a conceptual framework that captures important elements of federal systems and puts these elements together in a logically consistent whole. This yardstick will then allow us to gauge similarities and deviations in empirical cases both synchronically and diachronically.

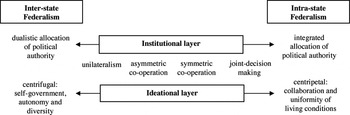

The dichotomy of inter- versus intra-state federalism offers a valuable starting point for making conceptual sense of the “varieties of federalism” (Broschek, Reference Broschek2009; Colino, Reference Colino, Erk and Swenden2010; Schultze, Reference Schultze1990). In terms of a multilayered federal order, inter-state and intra-state federalism can be seen as two conceptual extreme poles, or ideal types, each comprising contrasting institutional principles and diverging legitimatory frameworks (Figure 1). Inter-state federalism establishes a dualistic allocation of political authority. By distributing political authority and power resources independently between the federal level and the constituent units, this institutional layer impinges on the system of intergovernmental relations by considerably extending the scope of interaction modes if compared with its intra-state counterpart. In inter-state federations political actors from both tiers of government can either commit themselves to negotiate voluntarily, thereby establishing an asymmetric or symmetric system of co-operative federalism or, alternatively, exit negotiations and instead opt for unilateral action whenever they cannot reach consensus. This governance structure thus only loosely couples the federal tier and the constituent units. In doing so, the institutional design of inter-state federalism promotes a high degree of flexibility and is particularly well suited to maintain autonomy in territorially divided societies. Accordingly, the ideational layer typically displays centrifugal legitimatory frameworks in which ideas like self-government and regional diversity are well established.

Figure 1. Federalism as a Multilayered Political Order

Rather than assigning jurisdictions independently to each tier of government, intra-state federalism provides for an integrated allocation of political authority. It not only firmly entrenches constituent units' participation in federal decision making, but also provides for a functional distribution of competencies between both governmental tiers. While for the most part the right to legislate is assumed by the federal level, constituent units remain primarily responsible for the implementation process (Hueglin and Fenna, Reference Hueglin and Fenna2006: 71; Schultze, Reference Schultze1990: 480). As a system of intergovernmental relations, this institutional setting tends to yield a system of joint decision making (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988) rather than co-operative federalism. It is necessary to analytically distinguish joint decision making from less rigid modes of intergovernmental interaction: Whereas joint decision making enforces political actors from both governmental tiers to reach consensus when political change is to be pursued, co-operative federalism presupposes that actors from both tiers of government commit themselves voluntarily to find common solutions (Benz, Reference Benz2008: 5; Broschek, Reference Broschek2009: 47; Schultze, Reference Schultze1990: 480–81). Finally, as this tightly coupled governance structure is better suited to accommodate conflicts in homogenous societal contexts, it is matched by an ideational layer featuring federal visions which display centripetal goals such as collaboration or the equality of living conditions.

II. Explaining Change in Multilayered Political Orders

Conceptualizing federalism as a multilayered political order thus offers a valuable avenue to analytically disaggregating the unit of analysis and to systematically mapping possible directions of change in federal systems. It allows us to register how each layer changes over time as well as how these changing configurations, taken together, affect the federal order as a whole. Applying a historical-institutionalist framework can then contribute to explain why such distinct patterns of change unfold over time.

Historical-institutionalist approaches to the analysis of political change place a strong emphasis on the causal effects of temporality. Recent contributions have stimulated an enriching debate on how exactly temporality might affect the scope and patterns of political change (for example, Bennett and Elman, Reference Bennett and Elman2006; Howlett and Rayner, Reference Howlett and Rayner2006; Lecours, Reference Lecours and Lecours2005; Orren and Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2004; Page, Reference Page2006; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Thelen, Reference Thelen1999). While they share a common concern for temporally constructed and connected historical processes, historical-institutionalists rely on a rather diverging set of analytical tools which guide their inquiries. This is hardly surprising since the way social and political processes unfold in and over time can take various forms as regards, for example, their duration, pace or distinct trajectories (Aminzade, Reference Aminzade1992).

In an illuminating article Michael Howlett and Jeremy Rayner (Reference Howlett and Rayner2006) systematically demarcate three distinct models of historical change and discuss the analytical strengths and weaknesses for each: narrative, path dependence and process sequencing models. According to Howlett and Rayner, the model of path dependence and the process sequencing model have evolved as the most important alternatives to ahistorical theoretical approaches in which timing and sequencing has no explanatory value per se. Most basically, the model of path dependence lends itself particularly well to explaining stability and continuity while the process sequencing model is better suited to capturing patterns of change in which contingent alignments have more room to play out.

a. The Model of Path Dependence

The model of path dependence is a much used analytical tool in current research inspired by historical institutionalism. Basically, this model consists of three elements: initial conditions, a critical juncture and self-reinforcement (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000: 513–15).

The sources of a path dependent sequence can be found early in a sequence. Under a given set of initial conditions, a comparatively broad range of options is available to alter the status quo. As long as there is no selection from this menu, far-reaching change comprising a variety of possible directions is to be expected. With the arrival of a critical juncture, however, this state of historical openness comes to an end. The critical juncture mediates between the menu of choices initially available and the long-term historical outcome, since it provides that one option, which is stochastically related to these initial conditions, is selected and stably reproduced while other options which had been available before are no longer viable alternatives (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000: 513; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004: 51).

While both the occurrence of a critical juncture and the selection of an option itself are highly contingent events, contingency tends to be neutralized the more the historical trajectory temporally departs from the critical juncture. Positive feedback effects stabilize and amplify the choice initially taken. The identification of a path dependent process therefore not only provides evidence that the selection of an option has involved a significant dose of contingency early in the sequence, but also that long-term stabilization of this initial choice can be made plausible by referring to some type of mechanism of reproduction. For the purpose of investigating continuity and change in multilayered political orders, two types of mechanisms of reproduction seem to be particularly important: power-based and legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction.

According to James Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2000: 521), a power-based mechanism reproduces a contingent outcome over time because its rules and distributional consequences are conducive to the consolidation of a power structure which favours certain societal or political groups at the expense of others. Since it is the institutional layer which allocates power resources among territorial units, this type of mechanism can illuminate why federal systems empirically cluster either more along the pole of inter-state or, alternatively, intra-state federalism over time. Both institutional arrangements offer distinct opportunities for political actors to promote their interests and, thus, to produce incentives that more firmly entrench these institutional features of a federal order over time. They generate increasing returns for those working within the institutions and simultaneously raise the costs of those trying to change them. As a consequence, an institutional layer might become “locked-in” as a group of supporters will carry on maintaining and promoting the federal outcome (see Falleti, Reference Falleti2005: 331).

To be consistent with the model of path dependence, however, the historical evolution of an institutional layer maintained by power-based mechanisms must not be predictable by the pre-existing power configuration. If, as suggested in the literature, contingency becomes paramount during the selection process, it is necessary to have some openness early in the sequence with respect to the question of which group will turn out to be its major beneficiary in the long run. Accordingly, the evolution of an institutional layer can go hand in hand with changing power dynamics early in the sequence. As a consequence, it might even be the case that formerly marginalized groups become empowered with the emergence of an institution and provide for its self-reinforcement.

Legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction support the long-term stabilization of an institution since it corresponds to system-level actors' perception of what is morally appropriate or just (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000: 523). As in the case of power-based mechanisms of reproduction, timing is decisive here as well. To become “locked in” in a path dependent manner, it is necessary that such legitimatory frameworks do not simply evolve as “ideas whose time has come.” Rather, they too must result from an initial setting during a critical juncture that entails at least two or more, perhaps conflicting, legitimatory frameworks, and it must be possible to ascribe the evolving ascendancy of the prevailing one to a logic of self-reinforcement.

Each mechanism of reproduction can be applied to distinct layers of a political order. Capoccia and Kelemen, in an illuminating article devoted to the concept of critical junctures, remind us that in a multilayered political order “a historical moment that constitutes a critical juncture with respect to one institution may not constitute a critical juncture with respect to another” (Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007: 349). The same holds for the mechanisms of reproduction which provide for the self-reinforcing dynamic of different layers. More specifically, an institutional layer shapes and structures the relationship between collective actors, groups and individuals by (re-)distributing power resources among them, by exercising coercion and claiming compliance. Hence, power-based mechanisms of reproduction lend themselves well to explaining the path dependent evolution of an institutional layer, whereas legitimation-based mechanisms, with their emphasis on widely shared legitimizing ideas and social constructs, are better suited to detecting a path dependent trajectory of an ideational layer.

b. The Process Sequencing Model

Coping simultaneously with both the explanation of stability and change poses a vexing problem for the model of path dependence (Harty, Reference Harty and Lecours2005). While the model of path dependence has proven to be a powerful explanatory device that enables researchers to make sense of processes marked by long-term stability, scholars disagree about how to best capture the existence of different patterns of change in the real world as well as how to conceptually include endogenous causes that might trigger change within a temporal sequence. In particular, the call for a rigorous conceptualization of path dependence in order to avoid concept stretching has left the impression that the model allows for too much contingency early in the sequence, while being too deterministic at the back end (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999: 385).

In contrast, the process sequencing model puts stronger emphasis on endogenous sources of political change than on exogenous shocks. Rather than being induced by highly contingent and random events, change as conceptualized in this model is assumed to be deeply embedded in previous developments within the historical trajectory (Howlett and Rayner, Reference Howlett and Rayner2006: 7). Robert Lieberman, for example, hints at “frictions” emerging from the interplay of ordering layers as an important source of endogenous change. Lieberman suggests that institutional and ideational layers of a political order are normally neither equilibrated nor internally connected with each other in any coherent way. Instead, these layers permanently generate frictions stemming from mismatched and contradictory imperatives that impinge on political actors (Reference Lieberman2002: 702). This argument draws heavily on parallels with Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek's work on American political development which brings into focus incongruities between institutional layers as an endogenously generated source of political change. Orren and Skowronek argue against periodization schemes coalescing into “neatly ordered periods” (Reference Orren, Skowronek, Dodd and Jillson1994: 321) that political processes might permanently be subject to contingent alignments. Instead of analytically separating change from continuity, they suggest that different temporal mechanisms are operating simultaneously within a political order. While certain layers may indeed be stably reproduced over time, others change, thereby exhibiting different patterns moving at various paces (Reference Orren and Skowronek2004: 116–18).

Moreover, the literature on process sequencing has made available additional types of sequences which are more open to contingent developments and less stable than a path dependent sequence (Bennett and Elman, Reference Bennett and Elman2006: 258–59; Page, Reference Page2006). Whereas the model of path dependence suggests that options which had previously been available get irreversibly lost after a critical juncture, the process sequencing model brings into focus the possibility of shifting directions or even reversals within a historical trajectory (Howlett and Rayner, Reference Howlett and Rayner2006: 8). A cyclical sequence, for example, does not exhibit one equilibrated stable long path but oscillates between two or more alternatives (Bennett and Elman, Reference Bennett and Elman2006: 258). This type of sequence resembles a pattern of historical change that Stephen Skowronek has identified as “recurrent” (as opposed to “persistent” and “emergent” patterns) in his studies on presidential leadership (Skowronek, Reference Skowronek1993: 9–10). Skowronek's work reveals that, depending on the characteristic political challenges they face, presidents are prone to perform and reconfigure the institutional regime in a recurrent fashion.

III. Tracing Federal System Dynamics: Canada and Germany

a. The Institutional Layer

To be consistent with the model of path dependence, a contingent outcome triggered by a critical juncture must be reproduced even in the absence of the initial conditions that had brought it into existence (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). This theoretical argument basically applies to the evolution of the two institutional layers under examination. In Canada and Germany alike, different federal solutions were selected from several options which were available during the critical junctures of 1867 and 1871. Apart from the possibility that the status quo could have been preserved as a result from state formation failure, the founding fathers in both countries had at least three options at their disposal: a unitary state or two variants of a federation, either more along the lines of intra-state federalism or, alternatively, of inter-state federalism. The adopted federal architecture in Canada and Germany reflected the principles of one type or another of federalism from the very beginning. Yet, even though these distinct features already shimmered perceptively through the federal orders at the time of their birth, it took some time until they became amplified and aligned themselves almost prototypically with the two types of federalism.

Under the institutional framework of the German Confederation (1815–1866) the German states became increasingly concerned with a modern form of state building. Almost everywhere the scope of policy activities increased considerably, especially after 1849. In particular, governments of the German states began to take a more active stance in areas such as education, economic and infrastructure policy. As Abigail Green (Reference Green2001) has demonstrated in her comparative study of Hanover, Saxony and Württemberg, these state-building initiatives were deliberately designed to reinforce particularistic loyalties on the state level. In a similar vein, Daniel Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2006), in his study on state formation in Germany and Italy, has detected strong infrastructural capacities that had produced high levels of state rationalization, state institutionalization, and embeddedness of the state in society, on the level of the German states before the critical juncture eventually opened up in 1871. Hence, an institutional layer closer to the pole of inter-state federalism was not beyond the bounds of possibility since it would have allowed the states to preserve a considerable degree of autonomy. And, indeed, traces of inter-state federalism found their way into the constitution of the German Empire, most evidently in the area of fiscal federalism. Unlike in Canada, the constitution provided for a highly decentralized allocation of taxing powers. While the federal level had access only to tariffs and certain indirect taxes, the states were allocated the most important taxing powers (Nipperdey, Reference Nipperdey and Nipperdey1986: 82).

Yet it was an institutional layer highly receptive of intra-state federalism which soon turned out to shape the federal order during the time of the German Empire. Not only did the constitutional compromise yield a considerable degree of centralization in almost all important areas of state activity while implementation was left with the states, the federal chamber (Bundesrat) also emerged as the institutional core of the newly established federation. The historical roots of the Bundesrat can be traced back to two institutions that had served a similar purpose within the former confederal framework, the Immerwährende Reichstag within the Holy Roman Empire and the Bundesversammlung within the German Confederation (Lehmbruch, Reference Lehmbruch, Benz and Lehmbruch2002: 84). Both institutions rested on the same institutional logic as they incorporated delegates from territorial units into the decision-making process at the confederal level. Therefore, the historical trajectory offered a time-tested institutional response to the dilemma facing the founders of the German Empire, that of achieving national unity without violently destroying constituent units with highly developed infrastructural capacities.

In contrast, it is hardly ever disputed in the literature that features of inter-state federalism have dominated the institutional layer of the federal order in Canada from the very beginning. Donald Smiley and Jennifer Smith, who have otherwise disagreed on the relative influence of intra-state elements in the early days of Canadian federalism, both concluded that Confederation generally can best be understood as an attempt to depart from joint decision making, if not the “joint decision trap” (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988), that characterized politics in the United Province of Canada (Smiley, Reference Smiley1987: 38; Smith, Reference Smith and Brooks1984: 270). Inter-state federalism thus provided a neat solution because it was obviously better suited to accommodate the interests of proponents of a legislative union imagined by Macdonald as well as by those Confederationists who were more inclined to the federal principle per se, most notably Bleus from Canada East and Reformers from Canada West. From the viewpoint of the former, this solution enabled them to establish a constitutional framework much more consistent with Westminster democracy than it would have been the case with an integrated allocation of political authority. As long as the federal government obtained important jurisdictions alongside a broad range of intrusive powers such as the powers of disallowance and reservation, the declaratory clause and the peace, order and good government clause, federalism could easily be considered as what John A. Macdonald called it, a “happy medium.”

This initial advantage notwithstanding, it took some time before the institutional layer began to unfold in a way that almost prototypically reflected the inter-state logic. The Senate and, more importantly, the cabinet were designed as institutional elements to provide for some form of entanglement and provincial participation in federal legislation. As regards the former, the ratio of bills defeated by the Senate was still comparatively high until the late 1920s (Mackay, Reference Mackay1963: 199). As had been already correctly anticipated by critics during the Confederation debates, however, the second chamber has never proven to be an effective device for regional interests to influence federal legislation. Likewise, the cabinet turned out to be a rather inadequate check on the federal government. This was, for example, the experience of the former Bleus when they were unable to prevent the repeal of the New Brunswick School Act or to protect the rights of the French minority in Manitoba during the 1890s (Morton, Reference Morton and McKillop1980: 215).

b. The Ideational Layer

Robert Vipond's notion that the federal principle was “in flux” (Reference Vipond1989: 5) in Canada during the 1860s and 1870s holds for the German case as well. Being in a state of flux indicates that contingency was paramount during the critical juncture which yielded the process of state formation and impinged on the question of how the emerging institutional framework and the manner in which it (re-)distributed political authority among territorial units could best be interpreted and justified. Yet, while this problem was eventually resolved in the German case where the paradigm of unitarianism successfully superseded competing visions more federal in nature, Canadian federalism lacked such an early “lock-in” on the ideational layer.

Federalist ideas had been deeply rooted in the early modern and modern tradition of German political thought (Green, Reference Green2003; Langewiesche, Reference Langewiesche2000). As a multifaceted and widespread ideological commitment, federalism significantly shaped political discourses as well as the legal debate during the Holy Roman Empire and the German Confederation. A critical reassessment of the long dominant narrative informed by Prussian historiography has revealed that contemporary German federalism can be traced back to a longstanding tradition of political fragmentation, regional autonomy and identities (Green, Reference Green2003). During the second half of the nineteenth century, however, these federal ideas increasingly came under pressure from strong intellectual countercurrents. Most importantly, the major driving force behind the process of national unification, the national liberal movement, decidedly considered federalism as a second-best solution if compared to the prospect of a unitary state (Nipperdey, Reference Nipperdey and Nipperdey1986: 79; Lehmbruch, Reference Lehmbruch, Benz and Lehmbruch2002: 71).

Reservations about the federal principle as a means of maintaining diversity were not limited, however, to the national liberal movement. Arguably, the increasing prevalence of unitarianism over alternative legitimatory frameworks, which had put a stronger emphasis on regional diversity, is nowhere more evident than in the area of legal political thought. At the time of German unification, the most influential current within the legal discourse still proceeded from the assumption that sovereignty is shared between the federal level and the states. This school of thought soon vanished and was replaced with a debate that rather narrowly focused on the question of whether sovereignty, now assumed to be indivisible, was vested in the federal or the state level (Oeter, Reference Oeter1998: 46–52). It is hardly surprising that under the conditions of Prussian hegemony and widespread unitarian orientations among the political and bureaucratic elite the former interpretation soon prevailed. This historical constellation itself, however, resulted from a highly contingent event: the outcome of the Prussio-Austrian war. After Prussia's victory over Austria in 1866 the so called kleindeutsch model of German unification, which unlike the großdeutsch model excluded Austria–Hungary, emerged as the ultimate pathway to German unity. The creation of a federation within the framework of the kleindeutsch model not only rendered unnecessary any efforts to accommodate ethno-cultural diversity but also paved the way for Prussian paramountcy and leveraged the unitary vision at the expense of more federalist orientations.

The Canadian case, in contrast, lacked such an overarching consensus concerning the moral foundations of federalism from the very beginning. Rather, the configuration of ideas underlying the federal order became even more vexing over the course of time (Montpetit, Reference Montpetit2008; Rocher and Smith, Reference Rocher, Smith, Roçher and Smith2003). Whereas in Germany the struggle between centripetal and centrifugal orientations was finally settled by the late nineteenth century, in Canada it has continued to shape the federal arena to this day.

The provincial rights movement successfully challenged Macdonald's imperial conception of federalism by effectively launching two powerful counternarratives. Confederation was to be interpreted either as a compact between equal provinces or, alternatively, two founding nations (Cook, Reference Cook1971; LaSelva, Reference LaSelva1996; Vipond, Reference Vipond1991). Yet while these province-based legitimatory frameworks have in common that they both lean heavily towards the inter-state pole, it has nevertheless been difficult to accommodate them. The inherent tension between them has surfaced most visibly in recurrent controversies about the legitimacy of asymmetrical arrangements within the federation.

Moreover, the demise of Macdonald's imperial conception of federalism did not render the federal government meaningless once and for all. The resurgence of federal visions different from the two province-based paradigms became most evident in the wake of the so-called Second and Third National policies, when the federal government again took on a more active role in the intergovernmental arena (Smiley, Reference Smiley1975; Leslie, Reference Leslie1987). Though important elements of Trudeau's ambitious agenda such as the National Energy Program eventually failed, federal attempts to launch national policies clearly indicate that pan-Canadian visions, aimed at levelling disparities and underscoring that the sharing community is the whole rather than its parts, have never gotten entirely lost in the trajectory of Canadian federalism (Banting, Reference Banting, Bakvis and Skogstad2007: 140–42; Simeon, Reference Simeon1980: 184–85).

The problem with these competing legitimatory frameworks is not so much their mere existence, particularly since they are not necessarily exclusive. The experience of the Pearson years, when a more accommodative form of pan-Canadianism gained leverage, demonstrates that it is not impossible to bring intergovernmental relations on a more equilibrated path from time to time (McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). From the perspective of sequencing, the point is rather that no single idea has ever become “locked in” as a cognitive or normative frame which has resonated in a significant part of society for an extended period. Unlike in Germany, political actors were unable to actively cultivate one paradigm early in the historical sequence. The effectiveness of legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction, however, depends considerably on such an early “lock-in” because social constructs then appear as objective, given truths to succeeding generations and are difficult to challenge on behalf of entrepreneurial agents. The success of the provincial rights movement in establishing the “myth” (Russell, Reference Russell2004: 48) of the compact theory was, therefore, an important event early in the sequence which effectively contributed to impeding such a habitualization of Macdonald's imperial conception of federalism.

c. Path Dependence and Mechanisms of Reproduction

In both cases, path dependent dynamics have been at work in reproducing the institutional layers of each federal order. These path dependencies are particularly evident if one takes into account that the institutional logic operating each layer was left largely unaffected by several critical junctures following the process of state formation. In Germany, a highly integrated allocation of political authority existed within the authoritarian regime of the German Empire and the turbulent Weimar Republic before it finally re-emerged within the framework of a stable parliamentary system after 1949. Calls to adopt the federal order towards a federation more in line with inter-state federalism in the wake of the twin pressures of German reunification and Europeanization have had little impact, if any at all, on the established institutional logic. Even if order-shattering events and periods in Canada have been less bold than in Germany, critical junctures which would have allowed the institutional layer to shift more towards the pole of intra-state federalism nonetheless existed, too. This holds especially for the period of “mega-constitutional politics” (Russell, Reference Russell2004) when structural constraints on major political reform proposals were significantly relaxed.

How, then, have power-based mechanisms of reproduction exactly maintained the institutional layer of the federal order in Germany and Canada? In Germany, the integrated allocation of political authority first of all owes its persistence to power-based interests of bureaucracies on the level of constituent units. This is why the transformation of power resources among political actors in the wake of the revolution of 1918 did not yield a unitary state even though this option was clearly favoured by the new democratic elite. They lacked administrative expertise and experienced staff and were thus dependent on the compliance of the old civil servants who still occupied large parts of the bureaucratic machinery. Due to the established preponderance of administrative structures at the level of constituent units, federalism necessarily kept momentum. Furthermore and, somewhat paradoxically, the self-preserving interests of the traditional bureaucratic elite unwilling to give away their power position converged with those of the newly elected governments on the level of constituent units (Clark, Reference Clark2007: 631–34; Nipperdey, Reference Nipperdey and Nipperdey1986: 88). This emerging coalition comprising local party organizations and their respective bureaucracies was successful in repelling attempts on behalf of their federal counterparts to finally establishing a unitary state.

The force of positive feedback generated by the integrated allocation of political authority in Germany becomes even more obvious in the light of two constitutional provisions that were imposed on the drafters of the Basic Law by the Allied military governors in 1949. The Allies thought a dualistic allocation of political authority would be more suitable to preventing the evolution of centralizing forces and, accordingly, tried to shape the German federal system in the image of the American model. In order to prevent a return to the centralizing features of the Weimar Constitution, they insisted on a system of dual taxation, assigning indirect taxes to the federal, direct taxes to the Länder level. Moreover, they intended to limit the influence of the federal government in all matters of concurrent legislation by making pre-emption subject to the so-called Bedürfnisklausel (Article 72 (2) Basic Law). According to the Bedürfnisklausel the federal government was only allowed to take action if it was required for the preservation of the legal and economic union as well as the establishment of the equality of living conditions.

Both provisions triggered strong negative feedback by almost all political actors. They immediately developed formal and informal routines in order to bypass the dualistic division of powers. In 1955, the old system of joint taxation was almost completely restored in the area of direct taxation and the horizontal equalization scheme was significantly enlarged. The constitutional reform of 1969 amplified this pattern by incorporating sales tax revenues into the framework of shared taxation and by enlarging the redistributive capacity of horizontal equalization once again (Renzsch, Reference Renzsch1991). Federal and Länder governments also deliberately ignored the dualistic impetus of concurrent legislation in the Basic Law. This was to be achieved by voluntary agreements that allowed for federal legislative pre-eminence in all major areas of concurrent jurisdictions. In turn, Länder governments were compensated with an extension of their influence on legislation through the second chamber (Lehmbruch, Reference Lehmbruch1998; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988). As a consequence, co-operative federalism was gradually transformed into joint decision making and both tiers of governments became enmeshed in a system of intergovernmental relations where exit options are barely available.

Notwithstanding the rather dualistic formal constitutional provisions originally entailed in the Basic Law, power-based mechanisms thus again directed the institutional layer of the federal order towards the pole of intra-state federalism. An integrated allocation of political authority and joint decision making generated positive feedback for bureaucratic executive actors and for political parties alike. First, governments from both governmental tiers along with their bureaucracies have been considerably strengthened at the expense of the decision-making capacities of Länder parliaments. Moreover, unanimous decision making behind closed doors is a pressure-relieving mechanism because political responsibilities are blurred. In the case of successful negotiations, all governments can claim credit, while blame for unpopular decisions can easily be shifted on others. This comfortable mechanism of executive decision making is particularly conducive to political actors' self-interest because they have no exit option available and thus cannot be held responsible for political outcomes in the same way as voluntarily negotiating politicians in federations that dualistically allocate jurisdictions (Benz, Reference Benz2008; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988; Reference Scharpf2005).

Second, highly integrated party organizations have significantly contributed to reconfigure the federal order during the post-war period. Given their high degree of internal coherence, federal party organizations have been able to effectively enforce compliance of their regional branches and, therefore, to influence the voting behaviour of Länder premiers in the Bundesrat. For federal parties in opposition, the Bundesrat is an important tool for frustrating legislative initiatives of the federal government. This is why in the past, as Lehmbruch's (Reference Lehmbruch1998) seminal work has revealed, territorially defined cleavages have been increasingly superimposed by the logic of national party competition.

Power-based mechanisms also provide a strong explanation for institutional path dependencies in Canada. In principle, the dualistic allocation of political authority has been continuously supported by various actors for different reasons. Provincial governments provided positive feedback because this allocation allowed for effective resistance of centripetal forces within the federation. It is a recurring pattern in the history of Canadian federalism that provincial efforts fail to launch quasi intra-state “voice” strategies in order to make the federal government more responsive to provincial needs. In turn, this has reinforced the inter-state logic because provincial governments can always seize the opportunity to exit and, therefore, develop political goals within their respective sphere of exclusive authority. The lack of responsiveness of federal institutions obviously generated negative feedback and explains, for example, why political actors from Quebec recognized during the 1880s that it would be more promising to exit federal politics and instead focus their activities within the boundaries of the province (Morton, Reference Morton and McKillop1980: 217–18). In doing so, they aligned with a pattern that had already been set into motion elsewhere, most notably in Ontario (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1981), and thereby further reinforced the inter-state logic originally built into the BNA Act. In a similar vein, the Social Credit government under William Aberhart attempted to “attain the objectives of the movement by exploiting the power and position of the provincial legislature rather than by modifying national policy through securing legislative change in Ottawa” (Mallory, Reference Mallory1976: 57) during the second half of the 1930s. Given that provinces have no jurisdiction over monetary or banking policy, this pattern is particularly striking.

Political parties considerably contributed to consolidate and sustain the inter-state order as well. In Germany's intra-state arrangement the concentration of decision making on the federal level has encouraged political parties to become highly integrated. In contrast, the dualistic allocation of authority in Canada has not only fostered the emergence of regional parties, but also a rather low organizational coherence of federal party organizations (Smiley, Reference Smiley1987: 117). For example, the inter-state arrangement enabled the Liberals, who were faced with considerable difficulties, to create an efficient opposition to Macdonald's Liberal-Conservatives on the federal level and to make up for the deficiencies by successfully concentrating their activities on the provincial level. This institutional mechanism discharged them from the difficult task of bridging the ethno-cultural cleavages between Ontario Reformers and Clear Grits on the one hand, the former Rouges on the other. After the Liberals had succeeded with their efforts to find common organizational and programmatic grounds to create a federal organization and then coming to power in 1896, the Conservatives—at least in principle—seemed to have realized that loosening the ties between federal and provincial organizations might be a promising strategy for them as well (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1993: 184).

Finally, federal governments in Canada too have cherished the benefits of an institutional layer more in accordance with inter-state federalism because it allows for effective action even in the face of provincial resistance. Neither the protective tariff of the First National Policy nor the National Energy Program or unilateral cuts entailed in the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) could have been conducted so effectively if provincial governments had their hands in federal legislation as in Germany's intra-state arrangement. More specifically, inter-state federalism has resonated well with Westminster democracy. The principle of parliamentary supremacy allowed the government to carry over, in a slightly modified form, imperial remnants that had already shaped the relationship between the British motherland and the former colonies (Laforest, Reference Laforest and Murphy2007: 61; Russell, Reference Russell2004: 24). While centralist provisions, such as the powers of reservation and disallowance alongside the peace, order and good government clause, lost relevance during the early twentieth century, they were substituted by the federal spending power which emerged as the most important power resource of the federal government. The spending power has enabled the federal government to effectively bypass legal restrictions stemming from the division of powers (Banting, Reference Banting, Bakvis and Skogstad2007: 138, 147). Not surprisingly, Ottawa deliberately avoided committing itself to a more collaborative approach as jointly requested by the provinces at the end of the 1990s and largely ignored even the moderate restrictions on the federal spending power as they were provided for in the Social Union Framework Agreement (McIntosh, Reference McIntosh2004).

d. Frictions, Sequencing and Patterns of Change

The concept of frictions captures endogenous sources for political change in the absence of exogenously induced critical junctures. According to Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2002), frictions arise from an increasing mismatch between institutional and ideational layers within a political order. He suggests that whenever frictions become more prevalent, the probability of far-reaching change increases significantly.

Until the 1990s, such frictions were almost nonexistent in Germany's federal order. Unlike in Canada, power-based mechanisms of reproduction have been strongly reinforced by legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction. Unitarianism, as Gerhard Lehmbruch (Reference Lehmbruch, Benz and Lehmbruch2002) has convincingly demonstrated, has resonated well with the integrated allocation of political authority, since it allowed governments to commit themselves to co-ordinate their activities in order to bring about uniform solutions applying in the country as whole, while it simultaneously preserved the political and administrative integrity of constituent units. In the wake of the twin pressures of German reunification and Europeanization, however, these legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction became increasingly threatened due to the rise of a new set of ideas which entered the political discourse and forcefully challenged the established configuration by advocating competitive federalism and disentanglement.

As a consequence, incongruities and contradictory pressures within Germany's federal order have become much more visible since the mid-1990s. Significantly, intensified regional disparities in the wake of reunification alongside the imperatives of the common European market have encouraged several Länder governments to destabilize legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction. Fiscally strong Länder governments ranked first among the coalition which has been deliberately trying to challenge the established intra-state arrangement. Negative feedback generated by joint decision making accrued most obviously to them. Given the poor economic performance of the six new Länder, a massive fiscal transfer increasingly strained resources of the old Länder, thereby intensifying regional redistributive conflicts (Benz, Reference Benz1999: 70; Ziblatt, Reference Ziblatt2002: 631–36). Furthermore, for many Länder governments it seemed to be more rewarding to extend their autonomous policy-making capacities rather than to devote their energies to federal joint decision making, given fostered regional competition within the European market (Benz, Reference Benz1999). These developments eventually converged with the seemingly permanent stalemate due to the frequency of opposing majorities in both chambers.

In the face of this cumulative legitimatory pressure, the defending coalition comprising the majority of fiscally weak Länder as well as the federal government was not able to stave off another major attempt to reform the federal order beginning in 2003. It is generally accepted among German observers, however, that the high expectations which had been raised prior to the reform were not met by any means (for example, Benz, Reference Benz2008; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2008; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2005). Because those actors aiming to challenge the status quo had no option to unilaterally exit the “joint-decision trap” (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988), this institutional setting provided the defending coalition with an important power resource in order to channel the agenda by determining what was negotiable and what was not. Fiscally weak Länder had discarded most controversial issues, such as equalization and taxation, from the agenda before negotiations even started. With these issues out of the way, there was still considerable scope, however, for disentanglement. The most innovative suggestion put forth was the idea to enact a provision allowing for “indirect disentanglement” (Schultze, Reference Schultze2000) by adopting a general opting out clause applying to most matters falling under concurrent legislation. This would have significantly enlarged the scope of policy autonomy of those Länder governments who are more inclined to implement their own solutions in areas such as regional economic and labour markets and social and environmental policy. Yet, here it was the federal government who prevented an institutional adaption which could have turned out to alter the path of German federalism in the long run. While opting-out provisions were strictly limited to very few jurisdictions, the deliberations were primarily absorbed by a desperate effort to subdivide jurisdictions which apparently belong together and then to assign these narrowly circumscribed matters “exclusively” to either tier (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2005: 14).

While frictions between the two layers of the German federal order have not yielded significant change so far, the picture looks rather different in Canada. Not only have frictions continuously been more pronounced than in Germany. They also have translated much more easily into a departure from the historically established status quo. In fact, Canadian federalism provides a striking example for how a path dependent institutional layer can exhibit non-path dependent change. It is a common yet somewhat simplifying view to trace the dynamic of Canadian federalism as oscillating between a centrifugal and centripetal pole (Black and Cairns, Reference Black and Cairns1966; Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1989). A more fine-grained perspective would certainly detect differences that have always persisted depending on the policy area (Leslie, Reference Leslie1987). If contrasted with the historical trajectory of the federal order in Germany, however, diverging historical dynamics become clearly visible. For example, even though the BNA Act established a highly centralized federal order, this initial advantage early in the sequence did not pay off in the way the model of path dependence would predict. Quite contrary to Macdonald's expectations, provinces did not whither away but instead emerged as powerful entities within the federation. Likewise, the federal government has frequently made use of its institutionally entrenched power resources, most notably the spending power, in order to thwart centrifugal dynamics stemming from province building.

Such cyclical swings and shifting directions within the trajectory of Canadian federalism are perhaps nowhere more visible than in the area of fiscal federalism. Within a comparatively short time frame Canada has recently witnessed once again a major process of political change both with respect to scope and pace. While in the early 1980s it was still federal Minister of Finance MacEachen who claimed a vertical fiscal imbalance resulting from growing transfer liabilities under the EPF arrangement, since the late 1990s it has been again the majority of the provinces which has to deal with an increasing mismatch between revenue raising capacity and spending obligations. In a deliberate move resembling much of what Thomas Schelling (Reference Schelling1960: 22) has described as the “paradox of weakness,” Ottawa took advantage of the power to bind itself by drastically scaling down fiscal transfers to the provinces in order to significantly improve its weak fiscal position within less than three years, most notably by introducing the CHST and reforming unemployment insurance in 1995 and 1996. The federal government's power to bind itself thus turned out to be an important prerequisite for restoring fiscal strength: After having unilaterally reallocated responsibilities within the federation, the federal government found itself again in the comfortable position of determining whether it wanted to redirect growing surpluses towards provincial transfers or, alternatively, keep on track with its new priority of direct and more visible transfers.

IV. Conclusion

As this analysis has shown, both models of change can contribute to enhancing our understanding of how federal system dynamics unfold over time. Timing and sequencing have had a profound impact on the two federal trajectories under examination. While history thus matters, the two case studies also reveal that it can, however, matter quite differently.

Most obviously, the model of path dependence lends itself well in accounting for the dynamic of change underlying the federal order in Germany. Several exogenously induced critical junctures notwithstanding, power-based and legitimation-based mechanisms of reproduction have persisted and kept the federal order on a path which originally had been brought into existence in the wake of nineteenth-century state formation. Even though the two types of mechanisms of reproduction do not align with each other as smoothly as they had done prior to reunification and Europeanization, thereby generating frictions between the institutional and ideational layer, several reform attempts have not brought about a significant alteration of the federal trajectory. The increasing gap between the institutional logic of intra-state federalism on the one hand and the ideas of competitive federalism and disentanglement on the other has not triggered a major readjustment of the federal order. Rather than being reproduced by positive feedback effects, however, intra-state federalism today appears to owe its persistence primarily to historically constructed institutional constraints: All attempts aiming to shift the institutional layer more towards the pole of inter-state federalism and to escape the joint decision trap today require the consent of those political actors who are inclined to preserve the status quo. Particularly in institutional arrangements marked by a high degree of rigidity, lacking any exit options, institutional constraints can thus take the place of positive feedback so as to reproduce an institutional layer and prevent frictions from translating into substantial political change.

The model of path dependence, too, has something to say about the Canadian case. As was illustrated, the institutional layer has been stably reproduced due to power-based mechanisms of reproduction. This has rendered unlikely any prospects for institutional reforms which would bring the federal order more in line with the logic of intra-state federalism. And yet the model of path dependence fails to bring into focus important features of the federal dynamic in Canada, that is, the cyclical swings and shifts which can be traced not only on the ideational layer, but also beneath the level of the path dependent institutional core, particularly in the system of intergovernmental relations as well as on the level of public policies. Unlike the model of path dependence suggests, early events and decisions were often effectively counteracted rather than amplified. Accordingly, the process sequence model offers a better analytical framework for understanding the evolution of the federal order in Canada. First, Lieberman's concept of frictions is better applicable here because, unlike in Germany, the institutional layer of Canada's inter-state order allows frictions to effectively materialize. As an endogenous source of political change, frictions have driven federal system dynamics in multiple directions without generating a long-term equilibrium or clear resolution. Second, this is not to say that the process sequencing model considers frictions to translate automatically into change, taking arbitrarily any direction possible. Rather, as Orren and Skowronek (Reference Orren, Skowronek, Dodd and Jillson1994) suggest, it is “pattern identification” which lies at the heart of this approach. Just as Stephen Skowronek has detected recurrent patterns in how presidents tend to reconfigure the inherited political order, it should be possible to identify similar patterns of readjustment within federal systems. While a deeper sequential analysis of these patterns is beyond the scope of this paper, I have hinted at the three interaction modes available in inter-state federations: unilateralism, asymmetrical co-operation and symmetrical co-operation. Whereas the federal order in Germany became increasingly “trapped” in joint decision making, all three interaction modes have shaped the system of intergovernmental relations in Canada at times.

Finally, this brings to the fore a more general, yet sometimes neglected, concern of historical–institutionalist thinking. Because the way institutional arrangements combine constraining and enabling elements differs, institutions are furnished with varying capacities to translate frictions into change. As a consequence, it is not only crucial to scrutinize how different temporal mechanisms might be simultaneously at work in operating a given political order. Moreover, the degree of institutional rigidity itself can hint at whether the model of path dependence, with its emphasis on stability or, alternatively, the process sequencing model, with its emphasis on endogenous sources of change and cyclical sequences, might be better suited to describe and explain patterns of change in multi-layered political orders.