Background

Evidence indicates that social isolation and loneliness can adversely affect health and well-being (Findlay, Reference Findlay2003; Fisher, Reference Fisher2011; Collins and Wrigely, Reference Collins and Wrigely2014). A recent overview of international systematic reviews, for example, demonstrates evidence of links between social isolation and loneliness with cardiovascular and mental health outcomes (Leigh-Hunt et al., Reference Leigh-Hunt, Bagguley, Bash, Turner, Turnbull, Valtorta and Caan2017). Given these adverse health and well-being implications, the ageing population in the UK and in other advanced economies, and growing numbers of people living alone, social isolation and loneliness in later life are emerging as major issues in many countries (Victor, Reference Victor2010; Bardsley et al., Reference Bardsley, Billings, Dixon, Georghiou, Lewis and Steventon2011; Jowit, Reference Jowit2013) The significance and awareness of social isolation and loneliness in academia, policy, and among the general public has recently been accelerated by the COVID-19 novel coronavirus pandemic. The ‘lockdown’ measures imposed by governments in the UK and worldwide designed to curtail the virus mean that people have been advised to remain at home and avoid social contact, thus raising the likelihood of social isolation and loneliness. However, despite much discussion and debate about social isolation and loneliness both in the past and during the recent pandemic, there remains a lack of clarity around the definitions and measurement of, and relationship between, the two concepts in academia, policy and practice.

There has been much academic debate about social isolation and loneliness (for example Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000, Reference Victor, Bowling, Scambler and Bond2003; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learnmouth2005; Bolton, Reference Bolton2011) and a number of policy interventions aimed at reducing them in the UK, the USA, and elsewhere internationally (see, for example, World Health Organisation, 2002; N4a, 2016; The National Lottery Community Fund, 2020; Campaign To End Loneliness, 2017; and recently in response to the COVID-19 pandemic through the Connection Coalition, 2020). However, to date, social isolation and loneliness have often been conceptualised discretely, or the two concepts have been conflated or confused, as Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learnmouth2005) also point out. As this article later outlines, the conflation of the two terms has led to conceptual confusion and this has meant that it can be difficult to target support for people at risk of social isolation and/or loneliness, a factor not helped by the lack of robust evidence of the effectiveness of interventions, recognised by four systematic reviews (Cattan and White, Reference Cattan and White1998; Findlay, Reference Findlay2003; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learnmouth2005; Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011). A meta-analysis of interventions designed to reduce loneliness (Masi et al., Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo2011) focused primarily on randomised group comparison studies and did find some statistically significant evidence that some interventions are more effective than others: namely, those which addressed maladaptive social cognition as opposed to those that addressed social support, social skills, and opportunities for social intervention. However, overall there is a general lack of understanding within the literature about which specific kinds of interventions are more successful for different groups of lonely or socially isolated people.

By drawing on an extensive literature search which includes a range of existing published academic research, as well as research published in grey literature, this article aims to redress this lack of conceptual clarity by providing a clear summary of the differences and similarities between the two concepts as they have been deployed by others, and by outlining existing international evidence of the relationship between the two. Further, it challenges the conventional understanding of the two concepts, suggesting that an additional important element is to explore how opportunities for social relationships can be facilitated, and also suggesting that by creating the right kinds of societal conditions, individuals are less likely to be socially isolated, more likely to experience meaningful interaction, and consequently less likely to feel lonely.

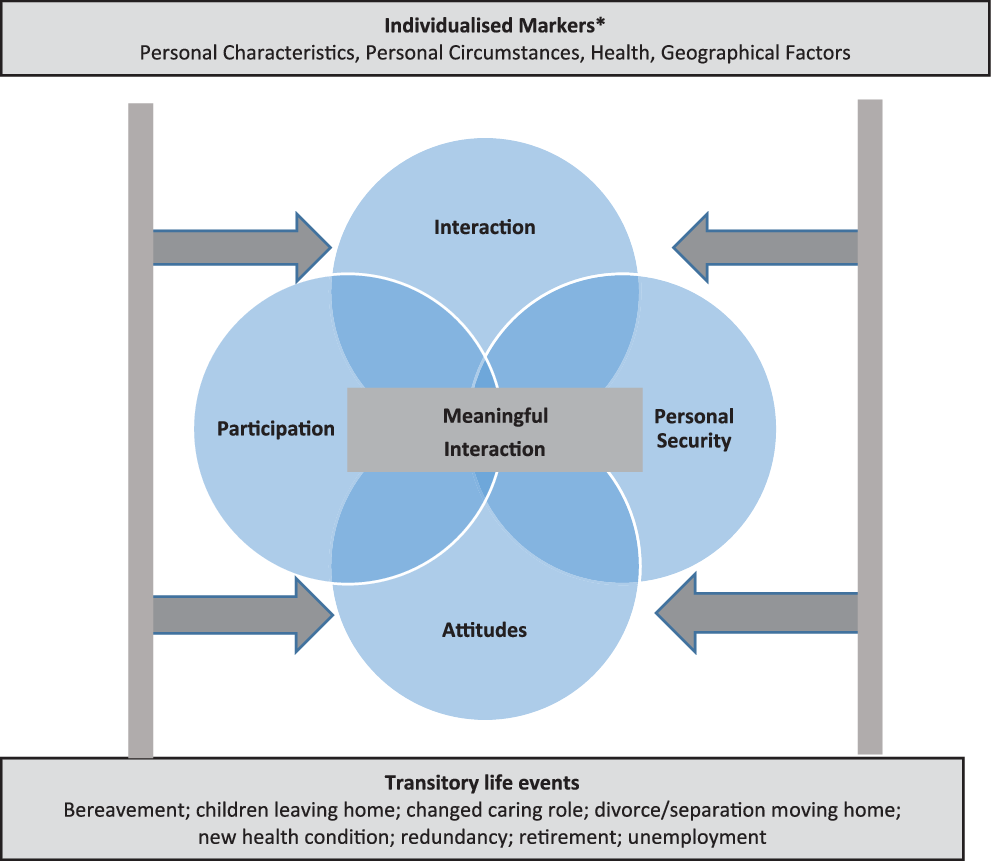

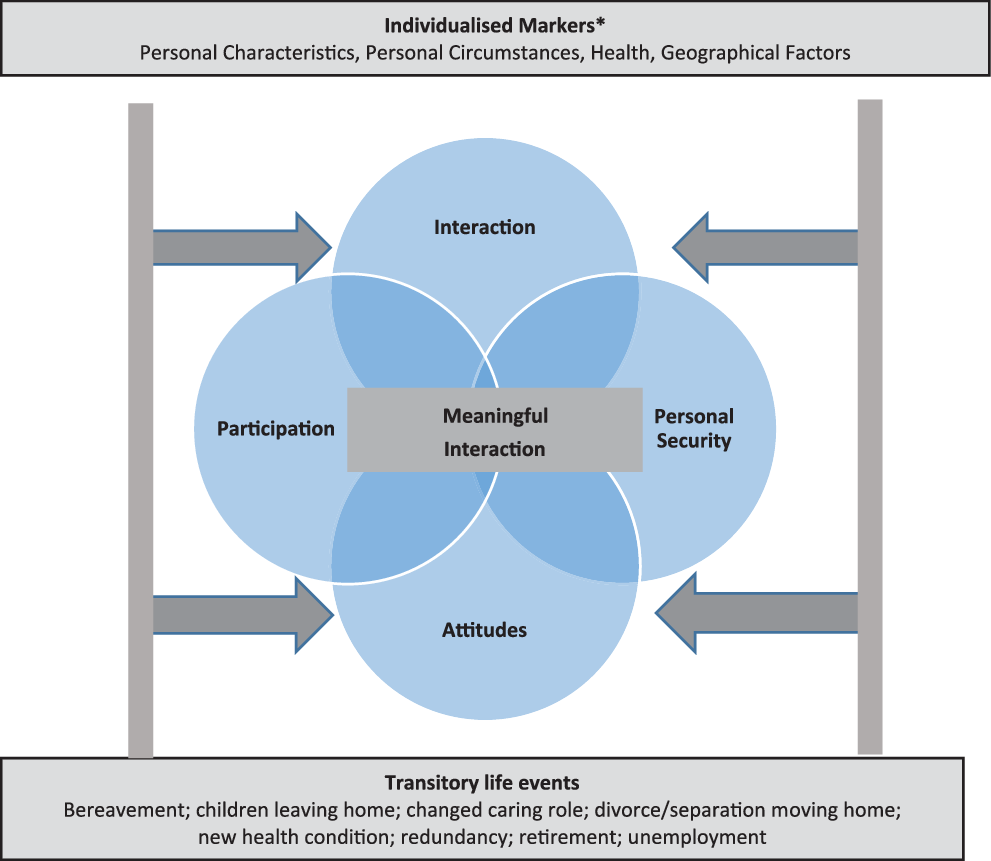

To achieve this, a new conceptual framework for exploring the nature and experience of social relationships based around meaningful interaction is proposed, developed by bringing together theoretical constructs adapted from symbolic interactionism, the Good Relations Measurement Framework (GRMF) developed for the UK’s Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), and from existing international literature on social isolation and loneliness. We argue that through this framework a fuller appreciation can be gained of factors encouraging and preventing meaningful interaction which can potentially help us to design better strategies to promote social relationships which are conducive to positive health and well-being among an ageing population, although specific policy recommendations are beyond the scope of this article. We contend that individuals’ experiences of four interlinked and overlapping domains (interaction, personal security, participation, and attitudes), along with individualised markers including personal characteristics and circumstances, health, and the geographical location within which they live, affect people’s ability and opportunity to experience meaningful interaction, thereby influencing their experiences of both social isolation and loneliness.

Methods

The evidence drawn on for this article is based on a ‘literature review’, as outlined in the typology of reviews by Grant and Booth (Reference Grant and Booth2009) of published and ‘grey’ literature. This involved using: Web of Science; Medline; Current Contents Connect; Scopus; plus the first ten pages of Google Scholar to extract peer and grey non-peer reviewed literature. Search parameters were selected to include the following key terms: social isolation; social isolation indices; isolation; loneliness; interventions; older people; Ageing Better programme; meaningful interaction; meaningful relationships; symbolic interactionism, good relations; attitudes; personal security; safety; participation; interaction; sense of belonging. A Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet was populated with headings to denote: author, date, title, publication, country/area. All relevant full text articles were obtained and the key issues/findings were grouped, tabulated, and analysed. Additional relevant publications which were cited in these full text articles, but did not emerge as part of the initial search results, as well as some articles recommended by academic reviewers, were subsequently also obtained and the same process followed.

Making sense of the current debate on social isolation and loneliness

Prior to discussion of our proposed framework it is important to outline existing definitions of social isolation and loneliness, which are often equivocal, and the subject of considerable academic debate. As far back as the 1960s, Townsend (Reference Townsend, Shanas, Townsend and Wedderburn1968) remarked that the concepts ‘living alone, loneliness, and social isolation’ were often used interchangeably. This is still the case for the latter two concepts more than fifty years later, as Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learnmouth2005) and Windle et al. (Reference Windle, Francis and Coomber2011) also note. Other researchers use definitions lacking uniformity, consistency, and clarity; particularly for social isolation, according to Nicholson (Reference Nicholson2009: 1342).

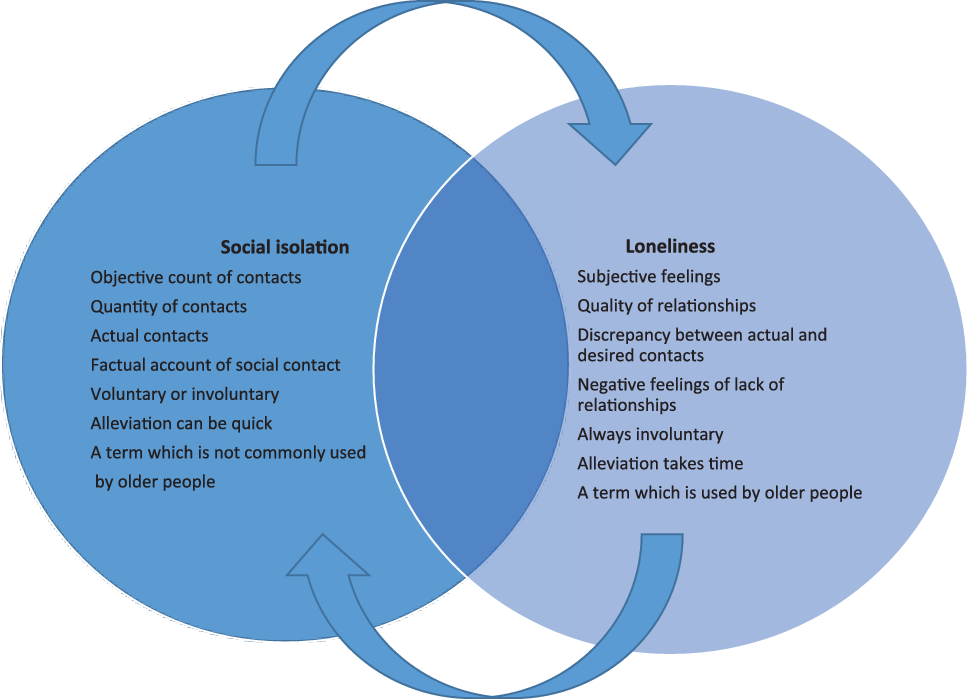

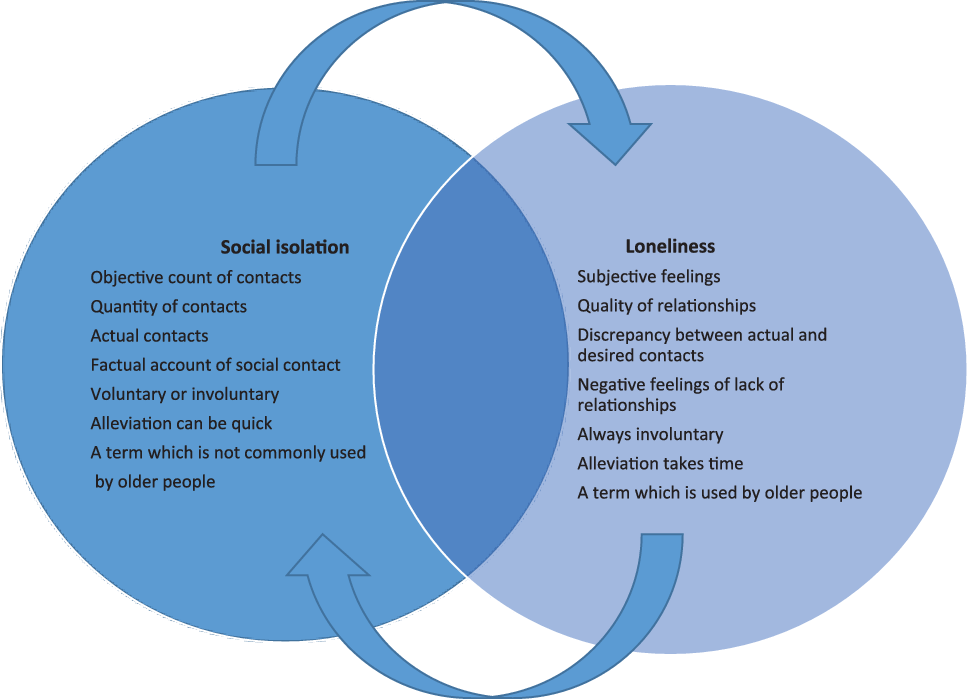

A review of international literature on social isolation and loneliness reveals a number of key issues used in defining and differentiating the two (see Figure 1 for a summary). The first relates to levels of subjectivity and objectivity. Loneliness is thought to be a subjective experience. It includes feelings about lack of connections with others and can be evident even where individuals have a social network. Social isolation, by contrast, is an objective count of social contacts; a condition of not having ties with other people (Dykstra, Reference Dykstra2009). The second is that the two terms are distinguished through an assessment based on either quantitative or qualitative relations, with social isolation more strongly associated with the former and loneliness the latter (Peplau and Perlman, Reference Peplau and Perlman1982). Many researchers (de Jong Gierveld, Reference de Jong Gierveld1987; Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2001; Grenade and Boldy, Reference Grenade and Boldy2008; Pettigrew and Roberts, Reference Pettigrew and Roberts2008; Segrin and Passalacqua, Reference Segrin and Passalacqua2010) argue that whilst social isolation is determined by the quantity of social contacts, loneliness is determined by their quality (including the time spent with contacts, Green et al., Reference Green, Richardson, Lago and Schatten-Jones2001). A third differentiation is in the variance between actual and desired contacts. Loneliness may be defined as the discrepancy between one’s desired and achieved levels of social interaction; whereas social isolation simply refers to levels of social interaction. The fourth relates to perceptions of the terms. Most (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson, Lubkin and Larson2014 being an exception) argue that social isolation is not necessarily negative, but that loneliness is a negative condition. A fifth relates to the nature of intent. According to Dickens et al. (Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011), social isolation may be either voluntary or involuntary, whereas loneliness is always involuntary. This infers that people may choose to be socially isolated, i.e. have no or few social connections but when this social isolation is not a choice and individuals have no or little choice or control over the social connections they have, it can lead to feelings of loneliness (Newall et al., Reference Newall, Chipperfield, Clifton, Perry, Swift and Ruthig2009, Reference Newall, Chipperfield and Ballis2014). The sixth distinguishing constituent is duration of the conditions: it is argued that social isolation can be alleviated quickly through gaining new acquaintances, while loneliness can be resolved only by the formation of an intimate bond, which may take longer (Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011). Finally, it is important to consider how the terms are understood by those experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, the conditions. Loneliness is a term in older people’s usage, although is often difficult to define academically, and can have multiple meanings. Social isolation, however, is straightforward to define academically, though is less well used by older people or the general public (Rook, Reference Rook1987).

Figure 1. A summary of existing definitions of, and relationships between, social isolation and loneliness.

Some authors have combined aspects of the aforementioned differentiations. Gardner et al. (Reference Gardner, Brooke, Ozanne and Kendig1999), for example, defined people as socially isolated if they had poor or limited contact with others, if they perceived this level of contact as being inadequate and/or they felt that it was having adverse personal consequences (the latter two being seen by others as loneliness). Dickens et al. (Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011) refer to social and emotional loneliness, with social loneliness representing negative feelings resulting from the absence of meaningful relationships and social integration, and emotional loneliness referring to the perceived lack of an attachment figure or confidant. Fine and Spencer (Reference Fine and Spencer2009), on the other hand, argue that social isolation has two distinct characteristics, social and affective isolation. That is, social isolation involves low levels of social interaction combined with experiences of feelings of loneliness. This approach of combining social isolation and loneliness into a single classification, however, merely adds further to the confusion and, as de Jong Gierveld et al. (Reference de Jong Gierveld, Van Tilburg, Dykstra, Vangelisti and Perlman2006) advocate, it is important to differentiate between the two concepts.

Existing evidence of the interrelationship between social isolation and loneliness

To understand more fully the relationship between social isolation and loneliness it is important to acknowledge existing international evidence on this dyadic interrelationship. Many authors (including Townsend and Tunstall, Reference Townsend, Tunstall and Townsend1973; Wenger, Reference Wenger and Jerrome1983; Andersson, Reference Andersson1986) argue the link is not straightforward: an older person may experience social isolation and loneliness concurrently (Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000); each condition can exist independently of the other (Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000; Davidson and Rossall, Reference Davidson and Rossall2015); and one can lead to the other (Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000; Wenger and Burholt, Reference Wenger and Burholt2004; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Kaye, Jacobs, Quinones, Dodge, Arnold and Thielke2016). Both conditions are not necessarily stable; people move in and out of loneliness (Victor and Bowling, Reference Victor and Bowling2012) and social isolation (Durcan and Bell, Reference Durcan and Bell2015), making it difficult to predict the impact of each on the other.

Our analysis of existing international literature on both the definitions of, and relationships between, social isolation and loneliness is summarised in Figure 1, demonstrating that individuals can be socially isolated, lonely, or both. Social isolation can lead to loneliness but there is also evidence that, in some cases, loneliness can lead to social isolation. The most important, but under-researched, finding, however, arising out of the corpus is the notion of ‘satisfying relationships’. Wenger and Burholt (Reference Wenger and Burholt2001), Borg et al. (Reference Borg, Hallberg and Blomqvist2006), and Coyle and Dugan (Reference Coyle and Dugan2012) all point to the role that satisfying relationships have in preventing or reducing the risk of loneliness. This is reported elsewhere, especially in relation to reducing loneliness and promoting well-being (Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Kalil, Hughes, Waite, Thisted, Eid and Larsen2008; Hawkley et al., Reference Hawkley, Hughes, Waite, Masi, Thisted and Cacioppo2008; Luhmann et al., Reference Luhmann, Hawkley and Cacioppo2014). Hawkley et al. (Reference Hawkley, Hughes, Waite, Masi, Thisted and Cacioppo2008), for example, demonstrate the importance of positive relationships in reducing loneliness and in creating a potentially protective measure against feelings of loneliness. This article develops further this proposition, arguing the importance of understanding satisfying relationships through a concept we refer to as ‘meaningful interaction’ and that an individual’s opportunities for meaningful interaction can be affected by wider societal conditions. The corollary is that through the creation of the right kinds of societal conditions, individuals may be less likely to be socially isolated, more likely to experience meaningful interaction, and therefore less likely to feel lonely.

Developing a framework for understanding the nature and experience of social relationships based around meaningful interaction

Thus far we have attempted to make sense of the current conceptualisation of social isolation and loneliness (Figure 1), but it is important to look beyond these two terms, and to explore individuals’ experiences of social relationships. It may not be necessarily useful, for example, to attach the labels of ‘socially isolated’ or ‘lonely’ (or both), to individuals. What is important, we argue, is a deeper understanding of the social relationships between individuals. By understanding the nature of individual relationships and the wider societal influences on those, future research can focus on identifying the kinds of interactions required to help both prevent and alleviate loneliness and thus generate more positive health and well-being, as well as the kinds of environments in which these relationships can be facilitated. The health implications of (a lack of) close social relationships has also been recognised recently by Holt-Lunstad et al. (Reference Holt-Lunstad, Robles and Sbarra2017).

The development of our framework, informed by analysis of published academic research evidence and grey literature, proposes that it is important to explore individuals’ experiences of social relationships, and suggests in particular that an individual’s experience of ‘meaningful interaction’ is the critical point. As Segrin and Passalacqua (Reference Segrin and Passalacqua2010: 320) similarly allude to,

what seems to matter most …. is meaningful connections with other people,

and the Campaign to End Loneliness refer to ‘meaningful connections’ as an ‘antidote’ to loneliness (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2017).

To explore this proposition further we draw on symbolic interactionism, a micro-level theoretical framework emerging in the mid-twentieth century from a variety of influences including Mead (Reference Mead1934) and his theories about the relationship between self and society, which address how society is created and maintained through repeated interactions among individuals (Carter and Fuller, Reference Carter and Fuller2016). Symbolic interactionism has clear applicability here, having been already adopted by various scholars to understand the relationships involved in the development of identity, in family studies (LaRossa and Reitzes, Reference LaRossa, Reitzes, Doherty, Shumm and Steinmetz2009), and more specifically patient–physician interactions in the United States to assess status implications (West, Reference West1984). Blumer’s (Reference Blumer1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method is the most comprehensive overview of Mead’s symbolic interactionist ideas, and its applicability to our approach to understanding contemporary social relationships is demonstrated by its recognition of each relationship’s uniqueness, and their changing and unpredictable nature. Blumer summarises his approach through three premises: (i) human beings act toward things on the basis of the meanings that the things have for them; (ii) the meaning of things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with others; (iii) meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretive process used by a person in dealing with the things he or she encounters (Carter and Fuller, Reference Carter and Fuller2016).

Blumer’s methodological approach is highly relevant for understanding social relationships because he emphasises

an intimate understanding rather than the intersubjective agreement among investigators.…the former being a necessary condition for scientific inquiry to have worth,

and that

any methodology for understanding social behaviour must “get inside” the individual in order to see the world as the individual perceives it (Carter and Fuller, Reference Carter and Fuller2016).

To Blumer,

empirically verifiable knowledge of social situations cannot be gleaned by using statistical techniques or hypothesis testing which employ such established research methodology, but rather by examining each social setting – i.e. each distinct interaction among individuals – directly (Carter and Fuller, Reference Carter and Fuller2016).

This methodological approach is significant for our progression of the current debate on social isolation and loneliness, as often these terms are explored in a quantitative way only through loneliness or social isolation indices or scales, and measured through surveys without supportive qualitative data. Indeed, loneliness may be underreported in quantitative research (Victor et al., Reference Victor, Bowling, Scambler and Bond2003).

Our framework, then, focuses on the nature of experiences of ‘meaningful interactions’ between individuals, including between family and non-family members, explored through both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Academic and policy work relating to meaningful interaction is currently under-developed. Much of the limited discussion on it occurred under the UK’s ‘New Labour’ administration (1997-2010) in line with their community cohesion objectives, with the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) at the time being tasked with both promoting and measuring changes in meaningful interaction, in this case between different ethnic groups; and the Commission for Integration and Cohesion advocated a definition in 2007:

…conversations [which] go beyond surface friendliness; in which people exchange personal information or talk about each other’s differences and identities; people share a common goal or share an interest; and they are sustained long-term (so one off or chance meetings are unlikely to make much difference) (Commission for Integration and Cohesion, 2007).

Academics such as Gill Valentine and her colleagues have also researched ‘meaningful contact’ or ‘meaningful encounters’ which have been documented through various published papers (see for example Valentine, Reference Valentine2008; Mayblin et al., Reference Mayblin, Valentine, Kossak and Schneider2015, Reference Mayblin, Valentine and Andersson2016; Valentine et al., Reference Valentine, Piekut and Harris2015) but similar to the DCLG they have explored it from a perspective of ‘difference’, such as faith, ethnicity, sexuality rather looking at the implications for loneliness and/or social isolation.

Although the Commission for Integration and Cohesion’s definition of meaningful interaction relates specifically to inter-ethnic relationships, research findings for the GRMF (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010), and knowledge generated from other reports which study older people and their social connections, for example Wigfield and Alden (Reference Wigfield and Alden2015, Reference Wigfield and Alden2017) and Alden and Wigfield (Reference Alden and Wigfield2016), indicate that it can be adapted to understand individual social relationships regardless of ethnic group, and can be conceptualised from a symbolic interactionist perspective. The role of meaningful interaction in individual relationships has been explored in the US, where Peters and Bolkan (Reference Peters and Bolkan2009) used the concept of ‘meaningful time experiences’ to examine intergenerational family relationships, using a ten-item measurement survey to capture the ‘depth of meaningful time experiences between older parents and their family members’ (Peters and Bolkan, Reference Peters and Bolkan2009: 21), and ask specific questions which could be adapted to explore meaningful interactions experienced in a broader sense by older people (both with family and non-family members, and of all generations). The measurement survey was subsequently tested for reliability and validity in a sample of older mothers and fathers (Tabatabaei-Moghaddam et al., Reference Tabatabaei-Moghaddam, Bolkan and Peters2012). Based on this meaningful time experiences concept, looking at research for the DCLG on meaningful interaction (including by the Office for Public Management, 2011), at the GRMF (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010), and research carried out by Valentine and colleagues (Valentine, Reference Valentine2008; Mayblin et al., Reference Mayblin, Valentine, Kossak and Schneider2015, Reference Mayblin, Valentine and Andersson2016; Valentine et al. Reference Valentine, Piekut and Harris2015) and drawing on the international research corpus on social isolation and loneliness, our conclusion is that for interaction to be meaningful, it needs to be ‘with people who are valued by the individual, who share a common goal or interest, to be positive, to go beyond the superficial level, and to be capable of sustainability in the longer term’. Further we argue that by enhancing meaningful interaction for older people we may be able to mitigate the negative health and well-being consequences of social isolation and loneliness.

Developing domains of meaningful interaction

It is important to explore how opportunities for meaningful interaction can be facilitated. Through the creation of appropriate societal conditions, individuals are less likely to be socially isolated, more likely to experience meaningful interaction, and less likely to feel lonely. Although as we explain later individualised markers, including personality trait (such as being an introvert) also play a role, and need to be considered alongside these wider societal conditions. Drawing on GRMF research (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010), it is suggested that the existence of meaningful interaction is determined by societal factors, grouped here into domains. Concomitantly, these domains have an important role in designing policies aimed at promoting meaningful interaction. Our framework is depicted diagrammatically in Figure 2; it identifies four domains influencing the prevalence of meaningful interaction between individuals (both family and non-family members): Interaction; Participation; Personal Security; and Attitudes. These domains intersect and overlap, the boundaries between them are somewhat blurred and, of course, their role in an individual’s life is influenced by personal characteristics and circumstances (including residential locality).

Figure 2. Framework for understanding the nature and experience of meaningful interaction.

Note: *See Table 1 for details of personal circumstances, personal characteristics, health and geographical factors.

Domain one: interaction

‘Interaction’ here refers to inter-personal contact on an informal or unorganised basis. The opportunity to interact with others is widely considered important for well-being (Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Kalil, Hughes, Waite, Thisted, Eid and Larsen2008; Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010). For contact to happen, nevertheless, a certain level of trust and personal security is necessary, as is suitable public space (Amin, Reference Amin2002). The importance of public space enabling a sense of common interest or mutuality is emphasised in much research (for example, Lownsbrough and Beunderman, Reference Lownsbrough and Beunderman2007; DCLG, 2008; Mayblin et al., Reference Mayblin, Valentine and Andersson2016).

Individuals’ experience of interaction is a key element in determining the nature of their social connections. Types of interaction with others varies, taking not just face-to-face form, but also through telephone conversations, email and letters, electronic applications such as Skype and Facetime, and through social media. For some – for example, older people with long term health conditions or disabilities – interaction is more difficult than for others, with inaccessible public spaces often hindering their ability to interact face-to-face. This can particularly affect high rise dwellers with disabilities or health conditions.

Counting the number of different types of social interaction is one way to assess levels of individual interaction. As discussed previously, such counts are aggregated to calculate social isolation. Individuals will inevitably differ in terms of the optimal number of social contacts they require and/or desire. Notwithstanding this our framework proposes that if the wider societal conditions are appropriate, individuals will have opportunities for interaction and be less likely to experience social isolation. However, it also recognises that although the number of contacts is important, it is the nature of those contacts which is crucial (Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart, Sörensen and Shohov2003; Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Kalil, Hughes, Waite, Thisted, Eid and Larsen2008; Hawkley et al., Reference Hawkley, Hughes, Waite, Masi, Thisted and Cacioppo2008). This includes who those contacts are with, and the nature of them. We argue, therefore, that individuals might have a low number of social contacts (i.e. be classed as socially isolated), but if those contacts are meaningful to them, are positive, and go beyond the superficial, then they are less likely to be lonely than individuals who have a larger number (i.e. not classed as socially isolated) of inconsequential or negative contacts. Promoting meaningful interaction (i.e. positive interaction, with people valued by the individual, which goes beyond the superficial level), therefore, is a significant aspect of our framework: we suggest that the presence of meaningful interaction, even with just one or two people, can negate the negative effects of social isolation, reducing the likelihood of feelings of loneliness. It should not be assumed that meaningful interaction necessarily occurs between people simply because they are family members. In some cases, those who have interaction with family members that does not meet the criteria of ‘meaningful’ may well feel more lonely. Indeed, marital or family contact that is conflictual has been associated with increased loneliness (Salamah, Reference Salamah1991; Jones, Reference Jones1992; Segrin, Reference Segrin1999). Interaction is also, of course, determined by people’s attitudes to others, individuals’ perceptions of personal security, and it is both a precondition of, and sometimes an accompanying factor to, the participation domain, as is noted later.

Domain two: participation

The concept of participation emerges extensively in health and social care literature (Piškur et al., Reference Piškur, Daniëls, Jongmans, Ketelaar, Smeets, Norton and Beurskens2014), and is a central element of several position papers from various branches of the United Nations, including UNICEF, UNESCO, and the World Health Organisation. It is manifested in various forms including the social, creative and cultural, and the civic (Green et al, Reference Green, Iparraguirre, Davidson, Rossall and Zaidi2017); and is a broad term referring to involvement in different types of organisation, including voluntary groups, charities, sports clubs, professional societies, trade unions. It is also used to refer to ability or desire to access the labour market, services, to having a voice and political representation, and the ability to participate in cultural events (Silver, Reference Silver1994; Pantazis et al., Reference Pantazis, Gordon and Levitas2006; Mathieson et al., Reference Mathieson, Popay, Enoch, Escorel, Hernandez, Johnston and Rispel2008). It has different meanings to different people, and numerous typologies of participation have been formulated. For example, Arnstein’s (Reference Arnstein1969) ‘ladder of participation’ places ‘Citizen Power’ as the top category on the ladder, ‘non-participation’ at the bottom, and ‘tokenism’ in the middle; Pretty’s (Reference Pretty1995) typology also stretches across a continuum, from ‘manipulative participation’, representing the inclusion of powerless token representatives, to ‘better’ forms of participation, such as ‘interactive participation’ and ‘self-mobilisation’.

Political and academic debates around participation in recent years have led to increasing pressure to promote more participatory forms of democracy, with both local communities and individual citizens being encouraged to participate in political, civic and social activities. Politically, Britain’s Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government’s (2010-15) promotion of the ‘Big Society’ proposed devolving responsibility for running society to local communities and volunteers in efforts to empower local people (Scott, Reference Scott2011). Academically, Putnam’s influential work Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000) provides a notable example of the academic debate, building on the concept of social capital, increasingly used in academic circles since the late 1990s.

Participation has been found to improve older people’s lives, leading to increased mobility, more positive outlooks on life, and a greater desire to take better care of oneself (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010; Piškur et al., Reference Piškur, Daniëls, Jongmans, Ketelaar, Smeets, Norton and Beurskens2014; Green et al., Reference Green, Iparraguirre, Davidson, Rossall and Zaidi2017; Tomioka et al., Reference Tomioka, Kurumatani and Hosoi2018). Existing research demonstrates that participation leads to greater levels of well-being (Piškur et al., Reference Piškur, Daniëls, Jongmans, Ketelaar, Smeets, Norton and Beurskens2014), and our framework proposes that the level and range (across activities) of participation also determines people’s levels of interaction with others, which is significant for meaningful interaction. The more an individual participates in a range of activities, the greater the level of interaction with others, the more active they become, and the less chance there is of their isolation. Participation can go beyond merely enabling greater levels of interaction and can facilitate meaningful interaction which, as noted, is likely to lead to individuals feeling less lonely. Hawkley et al. (Reference Hawkley, Hughes, Waite, Masi, Thisted and Cacioppo2008) is supportive of this, reporting that participation (through being a group member or regular church attender) can foster a sense of belonging, as well as increasing opportunities for the development of relationships that diminish the likelihood or level of loneliness. Indeed, participation brings together ‘like-minded people’ with common interests or goals, meaning that interactions experienced with others can be positive, and go beyond the superficial. The sharing of values and ideas, and having access to others with whom one can relate, was identified in focus groups informing the GRMF as helping to develop and maintain a ‘sense of belonging’ (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010), as was also the case in Tomioka et al. (Reference Tomioka, Kurumatani and Hosoi2018). As Hawkley and Cacioppo (Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010) note, participation in meaningful group activities can provide a sense of safety, enabling individuals to explore potential friendships with like-minded individuals whilst gaining a sense of belonging to the group. Interviews with older men on Age UKs fit for the future programme revealed similar findings: they were more likely to participate, and to experience meaningful interaction, when activities were tailored to their common interests – in this case, football and DIY – as this facilitated a connection to ‘like-minded’ people, a contributory factor to them feeling less isolated, deriving positive effects on their health and well-being (Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Kispeter, Alden and Turner2014).

We surmise that if societal conditions are conducive to participation individuals are less likely to be socially isolated, more likely to be able to engage in meaningful interaction, and less likely to be lonely. Participation is also, of course, determined by people’s attitudes to others (domain four), their resulting perception of personal security (domain three), and their experience of interaction (domain one), and, as with the other domains, there are other factors which influence people’s levels and types of participation: personal characteristics and circumstances; their residential area; social class; power relations; money availability; cost of activities; accessibility of transport and venues; availability of clubs, organisations, and activities nearby, and so on.

Domain three: personal security

Extensive research for the Good Relations Measurement Framework explored a number of different related terms before settling on the title of the domain of personal security (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010). By personal security we mean that an individual experiences a secure (untroubled by danger or fear either physical or verbal) condition or feeling. Use of the term ‘personal’ is important as it distinguishes between general feelings of security and a person’s own security. Personal security is highly significant to our proposed framework as, when present, it means people feel safe, able to leave their home, frequent public spaces and places, participate in organised activities, interact. Conversely, personal insecurity may find people reluctant to leave home, hesitant to attend organised activities, less likely to interact in public spaces and places. Personal security levels are closely linked therefore to the degree of individuals’ social isolation, their opportunities for meaningful interaction, and so their experience of loneliness. Evidence from elsewhere offers corroboration. Stancliffe et al. (Reference Stancliffe, Lakin, Doljanac, Byun, Taub and Chiri2007), for example, when researching individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities, concluded that social climate variables, such as being afraid at home or in one’s local community, were strongly associated with greater loneliness. Similarly, Jakobson and Hallberg’s (Reference Jakobson and Hallberg2005), research of older people in Sweden concluded that ‘loneliness and fear are probably closely related to each other, i.e. on one hand, loneliness may increase/cause fear and, on the other, fear may increase/cause loneliness through social isolation (e.g. fear of going outside, opening the door, interacting with unknown people)’ (p. 495). Hawkley and Cacioppo (Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010) explore this relationship further arguing that perceived social isolation leads to feelings of unsafety, and this then leads to heightened hypervigilance for (additional) social threat in the environment. They suggest that lonely individuals perceive more social threat than non- lonely individuals and this means that they expect more negative social interactions, remember more negative social information, and this then leads to behaviours from others that ‘confirm the lonely person’s expectations’.

Older people living in areas perceived to have high crime – in particular, antisocial behaviour – may be less likely to enjoy personal security, less able to leave their homes, and consequently have fewer opportunities for interaction (Wigfield and Alden, Reference Wigfield and Alden2015, Reference Wigfield and Alden2017). Bannister and O’Sullivan (Reference Bannister and O’Sullivan2013) reached similar conclusions about the damaging role of anti-social behaviour in relation to social cohesion, rendering people afraid to go out or visit certain places. Research findings from Sweden suggest that the cause of fear and insecurity among older people arises not only from the threat of violence and crime but also from other factors such as disease and health care crises, dependency on others, and the loss of significant others (Jakobson and Hallberg, Reference Jakobson and Hallberg2005). If individuals do not feel safe leaving their homes, using public transport, frequenting public spaces and places, they are less likely to have opportunities for any interaction, meaningful or otherwise; if they do interact with others they are less likely to be receptive to the idea of the interaction being positive, less likely to feel valued by others, and therefore less likely to engage in interaction which goes beyond the superficial, apart from perhaps with an existing network of friends and family. Individuals’ perceptions of personal insecurity, then, can lead to social isolation, meaning that meaningful interaction is more difficult to develop and maintain, in itself potentially leading to loneliness.

Domain four: attitudes

Attitudes, including how people perceive others and how they believe they themselves are perceived, also play a role in our framework. Attitudes of, and between, individuals encompass attitudes towards and from friends, family, neighbours, work colleagues, strangers. Positive attitudes towards and from others are likely to lead to greater levels of social interaction; negative attitudes may lead to lower levels of interaction, potentially leading to greater levels of social isolation, fewer opportunities for meaningful interaction, and greater chances of loneliness. Focus groups for the GRMF with both individual residents and with stakeholders around the country showed that attitudes affect how people feel during their everyday life, in turn affecting their personal security (domain three), and consequently their likelihood of visiting and interacting in public spaces. Negative attitudes by others towards an individual can affect that individual’s interaction and participation and were reported in the GRMF research to be manifest in a variety of ways including ‘looks and stares’, comments under the breath, or direct negative comments. Public transport is an arena frequently mentioned within which negative attitudes can have an adverse impact on people’s ability and opportunity to engage in everyday activities (Wigfield and Turner, Reference Wigfield and Turner2010). For example, Alden and Wigfield (Reference Alden and Wigfield2016) discuss the experiences of an older person, who had lost the confidence to go outside due to problems using public transport, particularly what she referred to as the negative ‘attitude of bus drivers’; another older person in the same report mentioned the ‘social stigma’ of disability adversely affecting his ability to go outside the home and participate in activities.

The ramifications of negative attitudes for interaction is exemplified in Higgins’ research on hate crime, where victims reported feeling scared, humiliated, stressed, isolated, and lacking in self-confidence (Higgins, Reference Higgins2006: 162-3). Nearly half the victims avoided going to certain places, others changed their routines, a quarter moved house, seven per cent changed jobs. This has a clear implication for meaningful interaction: if individuals cannot ‘be themselves’, they are less likely to be able to engage in interaction which goes beyond the superficial, and are potentially more likely to be lonely.

Loneliness itself can promote negativity. Hawkley and Cacioppo (Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010) show that lonely people tend to focus on more negative social information, expect social interactions to be more negative, and can derive less reward from positive social interactions. Similarly, Cacioppo et al. (Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman and Berntson2011) demonstrated that individuals experiencing social isolation tended to regard pleasant interpersonal interactions as less pleasant than individuals who felt socially connected. Hawkley et al. (Reference Hawkley, Burleson, Berntson and Cacioppo2003) also found that greater experiences of loneliness are associated with more generally negative perceptions of social interactions. Negative attitudes, therefore, can lead to loneliness; and loneliness can reinforce negative perceptions and experiences.

Attitudes and perceived attitudes of people towards each other play a role in determining not just the opportunities for, and thus the quantity, but also the quality, of interaction. Positive attitudes towards and from others are a precondition for meaningful social interaction that goes beyond the superficial, potentially reducing experiences of social isolation and loneliness. Conversely, negative attitudes can prevent meaningful interaction taking place, leading to people being more isolated and potentially more lonely.

Individualised markers, geographical factors, and transitory life events

As depicted in Figure 2, an individual’s experience of the four domains, and hence their ability and opportunity to a) interact with others (therefore avoiding unwanted social isolation), and b) experience meaningful interaction (therefore avoiding becoming lonely), is determined by a number of individualised markers incorporating personal characteristics, personal circumstances (including health), and the profile of the locality in which individuals live. Table 1 summarises some of the factors which can have an impact on an individual’s experience of the four domains and consequently their ability to avoid social isolation, engage in meaningful interaction, and be less lonely.

Table 1 Individualised markers and geographical factors feeding into the four domains of meaningful interaction

Note: *Health might instead be placed within personal circumstances, but given the significance of health conditions on individuals’ abilities to engage in meaningful interaction, it was considered more functional to group health conditions into a separate column.

These individualised markers and geographical factors can be applied internationally but have been identified from existing social isolation and loneliness indices developed by English local authorities (Dawkes and Simpkin, Reference Dawkes and Simpkin2013; Gloucestershire County Council, 2013; Leeds City Council, 2013; Medway Council, 2013; Bristol City Council, 2014; Luton Borough Council, 2014; Tonkin, Reference Tonkin2014; Collins, Reference Collins2015; Kent and Roberts, Reference Kent and Roberts2015; Somerset Intelligence 2016; Wigfield and Alden, Reference Wigfield and Alden2015). In Figure 2 we suggest, also, the need to take into account transitory life events triggered by factors such as retirement, bereavement, unemployment/redundancy, divorce/separation, children leaving home. These events can affect peoples’ experiences of meaningful interaction, triggering or limiting opportunities for meaningful interaction over the life course. Furthermore, looking at Figure 2 it is clear that many of the individualised markers, geographical factors, and transitory life events which influence opportunities for meaningful interaction are beyond the choice and control of individuals. This may have a significant influence on individuals’ experiences of loneliness, as a perceived lack of control can be a predictor of persistent loneliness (Newall et al., Reference Newall, Chipperfield, Clifton, Perry, Swift and Ruthig2009, Reference Newall, Chipperfield and Ballis2014).

Our framework for understanding meaningful interaction (depicted in Figure 2), then, proposes a new way of exploring social isolation and loneliness. Rather than simply assessing if people are socially isolated and/or lonely, we argue that there is a need to explore the nature of their social relationships and the extent to which those relationships provide meaningful interaction. We suggest that a range of individualised markers and societal factors affect individuals’ ability to interact with others, influencing the extent to which they are socially isolated, the extent to which they engage in meaningful interaction, and their experiences of loneliness. These wider societal factors need to be addressed by social policy in order to help increase our understanding of, and our ability to develop, strategies to promote meaningful interaction and tackle the adverse implications of social isolation and loneliness.

This proposition has a range of implications for social policy. Firstly, given the distinct differences between social isolation and loneliness, it means that social policy responses need to first identify which issue they are aiming to address – social isolation or loneliness or both – and then to develop a separate, but connected, tailored solution for each. At the moment, all too often, policy responses are designed to address social isolation and loneliness broadly without paying sufficient attention to the nuanced differences between the two. As a result, for example, quite often policy responses for lonely people are designed to increase their social connections, and thus reduce their experiences of social isolation rather than focus specifically on reducing their experiences of loneliness. Secondly, and linked to the previous point, social policy responses may need to be widened to identify ways in which lonely individuals can be supported to harness meaningful interactions with others, rather than simply focussing on connecting lonely people with others. This will undoubtedly involve developing programmes of support which identify appropriate activities, attract like-minded people, and also identify places and spaces where people feel able to engage in meaningful interaction. Finally, our model demonstrates how policy to tackle social isolation and loneliness, by promoting meaningful interaction, requires a response which goes beyond developing specific interventions but which develops a holistic solution which cuts across all policy areas. In order to support people to have more positive interaction and meaningful relationships there is a need to focus on increasing community participation, supporting people’s feelings of safety, and encouraging positive attitudes towards others which requires input from all areas of policy: housing; planning, policing, social care, community development, employment, education, health care and so on. That being said it should also be noted that people’s responses to such holistic societal strategies will not be homogenous and additional tailored interventions will continue to be required, including for individuals with specific personality traits such as maladaptive social cognition. Indeed as Masi et al. (Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo2011) note, when looking at randomised comparison studies of loneliness reduction interventions, the most successful interventions addressed maladaptive social cognition.

Our approach is fairly unique. Holt-Lunstad et al. (Reference Holt-Lunstad, Robles and Sbarra2017) do also recognise the importance of social relationships through social connectedness and do so through a typology of structural, functional, and qualitative dimensions, each of which exhibit multiple-causal elements, where structural refers to factors such as social network size/density, marital status, living arrangements; functional refers to received and perceived social support, perceived loneliness; and qualitative focuses on perceptions of positive and negative aspects of social relationships. This is a useful categorisation and measurement of pathways to social connectedness. It shares with our proposed new framework an appreciation of multi-causal factors, and at least an explicit recognition of the existence of both social isolation and loneliness. Moreover, it shares with our framework a need to explore the qualitative nature of social relationships, which Holt-Lunstad et al. (Reference Holt-Lunstad, Robles and Sbarra2017) note represents a gap in existing studies. However, Holt-Lunstad and colleagues stop short of explaining what a positive ‘social connection’ which can reduce people’s social isolation and loneliness looks like, i.e. what we refer to as meaningful interaction. Nor do they look at the wider societal influences of these positive social connections which we classify as: interaction, participation, personal security, and attitudes.

Conclusion

Social isolation and loneliness are issues of growing international concern, both being associated with poor health and well-being, affecting certain groups, including older people. However, the way that both concepts have been discussed is complex, and at times unclear, with academics, policy makers, and practitioners alike often conflating the terms. As a result, to date, definitions of the two concepts, how they might be measured, and the relationship between the two are not clearly articulated. Advancing the understanding of these issues, and how best they might be responded to, has consequently been fraught with definitional and positional uncertainty. This article has sought to redress this by providing a clear summary of the differences and similarities between the two concepts, drawing on seven distinguishing constituents: subjectivity and objectivity; quantitative or qualitative relations; actual and desired contacts; a factual account of social contact or negative feelings towards a lack of relationships; the nature of the intent associated with the concepts (voluntary or involuntary); the duration of the conditions; and how the two terms are used by those experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, them. Throughout this discussion it is recognised that social isolation can lead to loneliness, and that loneliness can lead to social isolation, though neither need necessarily be the case. Nor are these static conditions: individuals can experience differing levels of social isolation and loneliness over time, depending on changing structural and personal circumstances.

The two terms, of social isolation and loneliness, alone, are insufficient to provide a full understanding of the social relationships necessary to negate their potential negative health and well-being consequences, or to inform the design of policy solutions to promote the kinds of relationships which do create positive health and well-being outcomes for older people. Further, attaching a label of either ‘socially isolated’ or ‘lonely’ (or both) to an individual is not necessarily useful. Our framework is an exposition of the importance of exploring individuals’ experiences of social relationships, as it is the presence and nature of these relationships which can contribute to reducing loneliness and promoting associated positive health and well-being outcomes. In particular, an individual’s experience of ‘meaningful interaction’ is the critical point, an understanding of which can be best achieved by exploring social relationships from the perspective of symbolic interactionism, wherein relationships are explored in detail qualitatively, supported by quantitative data.

Our new model proposes that the ability of individuals to engage with each other, in a way which is meaningful, is determined by wider societal factors through a series of domains: interaction; participation; personal security; and attitudes. Individualised markers and geographical factors play a role in the way in which these domains prevent or enhance people’s ability to engage with each other and experience meaningful interaction, and these include individual characteristics (including personality trait); health; wealth; the geographical locations within which individuals live and frequent. It is important, also, to recognise the role and impact of transitory life events in triggering or limiting opportunities for meaningful interaction over the life course. These transitory life events are depicted in Figure 2. Although these transitory life events are often reported to have a negative impact, they can also have a positive effect on opportunities for meaningful interaction, depending on the individual circumstances. For example, a carer who ceases caring may now have more opportunities for meaningful interaction that were not present before. Or an older person who has been diagnosed with a new health condition, such as visual impairment, may be signposted to a new support group for the visually impaired which opens up opportunities for meaningful interaction which were not present before the diagnosis.

Through this article, then, we advance academic knowledge of social isolation and loneliness, advocating a novel approach to understanding the role that social relationships based on meaningful interaction play, drawing on the notion of symbolic interactionism as both a theoretical framework and a potential operationalisation mechanism. This new approach is significant for academic understanding of social isolation and loneliness, and has implications for policies aimed at reducing both conditions in later life, which may, in turn, help alleviate some of their negative health and wellbeing consequences. It emphasises the need to have activities, but also to create the appropriate places and spaces which can foster meaningful interaction. In the design of activities and the selection of places and spaces, the crucial role of the domains identified here needs to be taken into account in the construction of the overall milieu. We suggest, therefore, that policy interventions need to take a holistic approach cutting across policy areas (housing, policing, planning, education, social care and so on) and should consider the promotion of greater interaction and participation in order to facilitate meaningful interaction, whilst at the same time recognising factors which may work against this, such as negative attitudes or personal (in) security issues. These conclusions resonate with those by Leigh-Hunt et al. (Reference Leigh-Hunt, Bagguley, Bash, Turner, Turnbull, Valtorta and Caan2017), which suggest that an asset-based approach should be utilised to develop social isolation and loneliness prevention strategies across the public and voluntary sectors. Further research is now required to explore in more detail how meaningful interaction can be measured and facilitated in communities in the UK and internationally.