Introduction

What is a drum kit and how do we study it? There is a commonsense answer to this question: a drum kit is a musical instrument comprising an arrangement of drums, cymbals, and associated hardware, and it can be studied both formally (not just through private tuition but also prestigious music schools and academies) and informally (by practicing along to recordings, playing in bands, and so on). And yet this commonsense answer is deceptive because it hinges on taken-for-granted assumptions about the stability of the term ‘drum kit’ and the conventional ways of studying it. The problem, of course, is that musical definitions and conventions are not fixed, immoveable, or timeless; they are always in flux and in a constant process of being shaped by shifting historical and cultural contexts.

In fact, the definition of the drum kit – and consensus regarding its appropriate study – have changed dramatically over the course of the instrument’s history. This chapter is a rough guide to unpacking that history, and in doing so it treats the drum kit not as a fixed object but as a theoretical concept. What follows is a discussion of the drum kit in theory divided into three parts: (1) the invention and changing status of the instrument; (2) the trajectory of drum kit studies within the wider field of musical instrument scholarship; and (3) a discussion of the ‘drumscape’ as a theoretical tool.

The Invention of the Drum Kit

The drum kit is a uniquely American instrument whose invention coincided with the birth of jazz at the turn of the twentieth century; or at least this is the prevailing origin story that we see reproduced in numerous popular histories of the instrument.1 A typical version of the myth goes like this:

The drum set is one of New Orleans’ greatest gifts to American popular music. When the brass parade bands stopped marching and settled down in the riverboats to play – when the dances and comics in minstrel shows needed percussive accompaniment – when the blues came drifting off the plantations and mixed with Caribbean and African rhythms to make a new music called jazz, the drum kit was born.2

A similar account appears in a 2019 BBC documentary on the drum kit presented by Stewart Copeland. While being filmed on location in downtown New Orleans, Copeland holds up an enlarged photograph of the drummer Dee Dee Chandler, who played with the John Robichaux Society Orchestra at the tail end of the nineteenth century. Pointing to the bottom of Chandler’s bass drum, Copeland informs the viewer that ‘down here is one of the most important inventions in modern music’, and then declares Chandler to be ‘one of the first snare drum guys to play the bass drum at the same time … by inventing a homemade foot pedal’.3 To be fair to Copeland, the photograph of Chandler (taken circa 1896) is arguably the earliest surviving photograph of a drummer standing next to their bass drum pedal. But the viewer would be mistaken if they made the leap of assuming the photograph of Chandler was the first documented evidence of a bass drum pedal, or that it was unquestionably invented in New Orleans. Putting to one side the question of whether the hi-hat (which does not appear in drum catalogues until the mid-1920s) or separate tension tom-toms (which appear in the mid-1930s) are necessary core components of a drum kit, I will for the moment restrict my investigation specifically to the origin of the bass drum pedal.

Drummers have experimented with ways of playing more than one percussion instrument at once for centuries, if not millennia. To take a relatively recent historical example, it was common in the nineteenth century for both marching band and orchestral drummers to attach a cymbal to the rim of their bass drum so that they could play both at once.4 Jayson Dobney has documented that this practice was also evident in the United States, noting that ‘photographs taken during the Civil War often show a cymbal attached to a bass drum for use in a military band. After the war, this configuration could be found in many of the community and town concert bands that were gaining popularity throughout the country’.5

When theatre and symphonic orchestras attempted to represent the sounds of military marching band drumming indoors in cramped conditions and with fewer musicians, some inventive drummers began to place the bass drum on the floor so they could simultaneously play snare drum (often placed on a chair, since snare drum stands had not yet been invented) and bass drum (with cymbal often attached to the rim) – a performance practice which by the 1880s came to be known as ‘double drumming’.

So when did foot-operated drum pedals arrive on the scene? This is not an easy question to answer. In order to illustrate the complexity of the problem, and the messiness of historical research more broadly, I will present seven potential candidates for the bass drum pedal’s moment of origin, each with its own narrative advantages and disadvantages.

Option 1: bass drum pedals have existed from the early nineteenth century, but robust documentation proving their existence has not survived. As I document elsewhere in my book Kick It: A Social History of the Drum Kit, there are surviving illustrations from early nineteenth-century France that portray at least two different one-man bands using homemade beaters attached to their feet to play a drum with one foot, and a pair of cymbals with the other.6 Based on this evidence, you could argue for the possibility that foot pedals for drums and cymbals were likely discovered by multiple people independently in different countries from at least the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards and probably earlier. Here we begin to see that choosing a particular origin narrative serves a particular agenda: this first version of the bass drum pedal origin story privileges (a) the international roots of the technologies that inform the drum kit as an instrument; and (b) a ‘multiple discovery’ (no one person is attributed) rather than a ‘lone genius’ (one person only is attributed) narrative of invention. This origin narrative also de-privileges (a) innovations that have documented widespread impact (e.g. a pedal design that was successfully mass-produced); and (b) the USA as the country of origin for the proto-drum kit.

Option 2: the oldest surviving example of a foot-operated drum pedal is located (somewhat surprisingly) in the Keswick Museum in England. (A full discussion of this unusual bass drum pedal can be found in a 2014 journal article by Paul Archibald.)7 It was created by an inventor named Cornelius Ward for the novelty Richardson Rock and Steel Band. If we chose this as a moment of origin, it privileges (a) a single named inventor; (b) the role of drummers in novelty music (as opposed to jazz, for example); and (c) historical instruments in museum collections as a source of evidence.

Option 3: in the published memoir of Arthur Rackett, a long-time drummer for the John Philip Sousa Band, he recalled that ‘in 1882 I settled in Quincy, Illinois. This was about the time that the first foot pedal came out. Dale of Brooklyn made it. Everybody laughed at the idea, but I sent for one and started to practice in the woodshed’.8 This moment privileges oral history (Rackett’s memory preserved in print) but ignores the need for material evidence (no catalogue or paper trail corroborate the memory survives).

Option 4: the oldest legal patent for a bass drum pedal dates back to 1887, when George Olney of St Louis, Missouri, was granted a patent for a design very similar to that of Dee Dee Chandler, but Olney’s patent predates the photograph of Chandler by approximately nine years. This option privileges legal patents as documents of record, but de-privileges those who may have come up with a similar design but did not manage (or were somehow prevented) from patenting their idea.

Option 5: the earliest example I can find of a bass drum pedal being sold in an instrument catalogue is from 1893, when the German manufacturer Paul Stark published a catalogue to advertise his goods at the Chicago World’s Fair. This option privileges commercial production and evidence from instrument catalogues, and de-privileges the USA as the accepted country of origin for the bass drum pedal.

Option 6: as mentioned above, the earliest photograph of a drummer next to his bass drum pedal is likely that of Dee Dee Chandler in New Orleans circa 1896. It privileges the city of New Orleans, African American culture (Chandler was black), photographic evidence, and the notion that the drum kit only coalesces as an instrument through a particular kind of musical performance practice (e.g. dance music influenced by New Orleans second line drumming). It de-privileges patents as evidence (i.e. Olney 1887), countries outside the USA, and popular music not rooted in the jazz tradition.

Option 7: arguably the most famous of all the candidates outlined so far is William F. Ludwig’s 1909 patent for a highly successful and influential bass drum pedal design. This option privileges the overall impact a particular design has on the rest of drumming culture. From 1909 onwards Ludwig’s design is not only successfully mass-produced and sold but also widely imitated by other manufacturers.

The point of outlining seven different possible origin moments for the bass drum pedal is not, in my view, to then select one of them as the definitive version. Instead, the point is to draw attention the historiography of the drum kit – in other words, to draw attention to the processes of inclusion and exclusion that must be made when writing the instrument’s history. To investigate the origin of the drum kit, like any historical project, is necessarily to sift through a wide range of partial sources and piece together a story, which inevitably involves making judgments about what to leave in, and what to leave out of the story.

Put simply, there is frequently more than one way of framing the origin story of a musical instrument. The point here is that each of the possibilities above serves a particular ideological agenda, and to privilege one narrative necessarily excludes a host of equally important influences, inspirations, and voices. By giving attention to the multiple possible origin narratives and their implications, we can gain a better understanding of who and what we are including and excluding in the stories we tell, and why.9

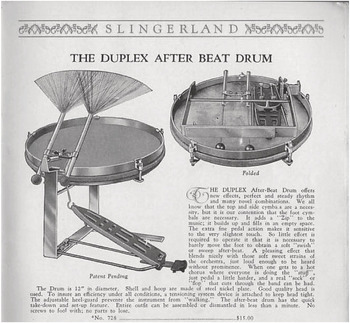

The historiographical lesson learned from the bass drum pedal can also be applied to invention of the drum kit in full as a distinct instrument – there is more than one possible moment of origin. Does the first drum kit appear in 1906, when the Philadelphia-based instrument manufacture J. W. Pepper publishes a catalogue featuring a pre-bundled ‘trap drummer’s outfit’ (comprising a bass drum, snare drum, cymbal, and bass drum pedal)? Or is it 1918, when Ludwig & Ludwig first advertise their own ‘Jazz-Er-Up’ outfit equipped with their signature bass drum pedal? Is it 1928, when a new accessory that we retrospectively recognize as a hi-hat pedal (produced and distributed by the Walberg & Auge company in Worcester, Massachusetts) begins appearing in multiple drum manufacturer catalogues? Or must we wait until 1936, when Gene Krupa collaborates with the Slingerland company to create the new ‘Radio King’ series of drum kits equipped with separate-tension tom-tom drums? To complicate matters further, what happens when electronic drum kits are introduced from roughly the 1980s onwards, or virtual drum kits from the 2000s onwards? Can a drum kit be acoustic, electronic, or virtual and still count as a drum kit? If this question causes even a modest amount of debate, then we have to assume that the meaning of a ‘drum kit’ is not fully stable. The pioneers of the acoustic drum kit could not have predicted that in the twenty-first century, debates around the meanings of a ‘drum kit’, ‘drummer’, and ‘drumming’ would include voices from computer software engineers and multinational corporations packaging virtual drummers into their digital audio workstations. Nevertheless, these actors significantly influence our contemporary understanding of what counts as a drum kit, drummer, or drumming performance.

To ask such questions is to point towards a broader question in the sociology of knowledge: what aspects of its design must stay the same in order for a drum kit to remain a drum kit over time? In the twenty-first century, when as many or more electronic drum kits are sold relative to acoustic drum kits – and when the sounds of multiple drum kits can be stored and deployed within a single software plugin – is the definition of what constitutes a drum kit categorically fixed? My argument is that it is not and never was, and this is what I mean when I say the drum kit is not a fixed object but a theoretical concept.

The History and Future of Studying the Drum Kit

Having now seen that the ‘drum kit’ is a contested concept whose meaning changes over time and across different contexts, it will come as no surprise that the same applies to studying the drum kit. William F. Ludwig published an essay in 1927 detailing his recollection of how drummers in the United States studied their instrument:

The old timers of Chicago were practically all rudimental drummers … [and] all probably had the same experience in learning to drum as I had. My dad stepped into Lyon and Healy’s store and simply said he wanted a drum book. [A book of military drum rudiments] was laid out on the counter and could be purchased for $1.00 each. It was the only drum book that [the store] had or recommended.10

With the advent of ragtime at the turn of the twentieth century, however, Ludwig observed that a new way of studying the instrument appeared: ‘new beats were invented, new systems of playing the drum were invented and, in fact, ragtime methods of all sorts appeared on the market, each one different from the other. Originality seemed to be the main object’.11 The ragtime and jazz eras fuelled a clash of musical cultures, specifically a tension between musicians who learned their instrument through reading and following notated sheet music versus those who learned to play through more informal methods and improvisation. In truth, learning to play the drum kit had always involved both formal and informal approaches, and even after the drum kit gained acceptance in institutions of higher education as part of university jazz programmes, drummers typically continued to study performance practice on their instrument using a mixed methods approach.

For most of the twentieth century, the practice of studying the drum kit could be divided into one of two categories: construction (how the instrument was designed and manufactured) or performance (how it was played). The study of the drum kit’s physical construction can arguably be situated within the wider field of ‘organology’ – a term coined in 1933 to designate the academic study of the material and acoustic properties of musical instruments dating back to the nineteenth century; it should be noted, however, that the scope of organology was severely limited for many decades, and the drum kit was not considered worthy of serious attention until the late twentieth century (see, for instance, James Blades’ 1970 landmark study, Percussion Instruments and Their History, which briefly contextualizes the drum kit’s origins amidst the wider history of percussion).12 Meanwhile, the study of drum kit performance can be situated with the broader field of ‘performance practice’ scholarship, which in the case of the drum kit made inroads into the academy with the gradual institutionalization of jazz in higher education over the second half of the twentieth century (Theodore Dennis Brown’s 1976 doctoral dissertation, A History and Analysis of Jazz Drumming to 1942, is a milestone in this respect).13 The establishment of percussion education organizations are also relevant here, such as the Percussive Arts Society (created in 1961), which held its first International Convention (PASIC) in 1976.

While the practice of studying the drum kit has gradually crept into the academy, it is worth emphasizing that many of the most important early analyses of the drum kit’s construction and performance were produced outside the academy. The publication of catalogues, newsletters, and periodicals about the drum kit are a useful example. The drum kit was a product aimed at a commercial market, and therefore the catalogues and newsletters produced by early drum kit manufacturers such as Leedy, Ludwig, and Slingerland are rich sources of information describing the latest innovations in the instrument; even though such descriptions were explicitly created to advertise the products of drum companies, they are nevertheless invaluable accounts of the drum kit’s design and construction. In terms of performance practice, a plethora of ‘method books’ appeared following the dawn of jazz: notable examples include Carl Gardner’s Modern Drum Method (1919) and Ralph Smith’s 50 Hot Cymbal Breaks and 70 Modern Drum Beats (1929), George Lawrence Stone’s Stick Control for the Snare Drummer (1935), Jim Chapin’s Advanced Techniques for the Modern Drummer (1948), and the list goes on.

Likewise, the vintage drum community that arose from the late 1980s onwards has produced numerous vital historical studies. While some of these were created with the primary aim of identifying, collecting, and restoring rare and potentially valuable drums and cymbals, others – including pioneering work by John Aldridge, Jon Cohan, Rob Cook, Chet Falzerano, and Geoff Nicholls, to name but a few – often included social history scholarship that provided insight into the cultural significance of the drum kit.14 Long-standing special interest magazines such as Modern Drummer (first published in 1977) and Not So Modern Drummer (first published in 1988) also produced important articles on the instrument, key artists, and performance styles and techniques that predate much of the academic scholarship on the drum kit.

In recent years, a much wider range of approaches to researching the drum kit has flourished, arguably marking a shift from a paradigm of ‘studying the drum kit’ (concerned mostly with issues of construction and performance) to drum kit studies (a fully interdisciplinary field of inquiry). The emerging field of drum kit studies is distinctive for embracing insights from a variety of academic sources – including but not limited to philosophy, sociology, anthropology, psychology, education, race, gender and class studies – which are brought to bear on the drum kit, drummers, and drumming. Systems of cultural theory that have proved influential elsewhere in musical instrument scholarship – such as science and technologies studies (STS), social construction of technology (SCOT) theory, actor network theory (ANT), and material culture studies – can also be productively applied to enhance our understanding of the drum kit (more of which in the next section). Drum kit studies is not itself a discipline per se, but a loosely organized field of study, which is slowly showing signs of cohering (as evidenced by the publication of this Cambridge Companion). The point here, however, is not to define drum kit studies in opposition to earlier ways of studying the drum kit, but to build upon them. Nor is it to isolate drum kit studies inside the academy from those occurring outside the academy. The drum kit is a living instrument, and drum kit studies therefore can, and should, actively encourage interaction and engagement between all spheres of drum kit culture.

In an effort to explore the breadth of what drum kit studies can and should be, I propose unfolding the term ‘drum kit’ from its narrow, commonsense definition (described at the outset of this chapter) into a larger map of directions for further enquiry. Steve Waksman has previously argued that musical instruments can be understood in a multitude of ways: as commodities, material objects, visual icons, sources of knowledge, cultural resources, and of course, ‘sound-producing devices, without which music could hardly be said to exist at all’.15 Similarly, Kevin Dawe has shown how musical instruments create forms of meaning, ‘changing soundscapes, affecting emotions, moving bodies, demarcating identities, mobilizing ideas, demonstrating beliefs, motioning values’.16 Inspired by the above and other recent work in musical instrument research, I propose that through the lens of what one might call the drumscape (which I will outline in detail in the following section), drum kit scholars can add the sum of these multiple perspectives together and make steps towards understanding not just how the drum kit, drummers, and drumming relate to the wider world – but how they impact upon it.

The Drumscape as a Theoretical Tool

The concept of the ‘soundscape’ is a twentieth-century invention. One of its key proponents, the composer and naturalist R. Murray Schafer, once theorized that ‘modern man is beginning to inhabit a world with an acoustic environment radically different from any he has hitherto known’, arguing that the soundscape of the world required careful study ‘in order to make intelligent recommendations for its improvement’.17 Similarly, the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai introduced further concepts like ‘mediascape’ and ‘technoscape’ to make sense of the intangible forces that shape the global cultural economy. More recently, Kevin Dawe has put forth the term ‘guitarscape’ in an effort to theoretically frame the guitar as ‘a large-scale musical-cultural-social occurrence that merits serious and ongoing academic study’.18 I suggest that if we are comfortable using terms like ‘technoscape’ and ‘guitarscape’, drum kit scholars might also benefit from the concept of a drumscape.19

The drum kit in all its forms (acoustic, electronic, physical, virtual, and symbolic) participates in the drumscape. (By virtue of its name, the drumscape can also encompass other instruments in the percussion family.) Such an approach encourages the study of the drum kit not just as a physical object or a performance practice, but as a symbol (encompassing both physical and virtual forms) whose meanings are determined by cultural use. In short, the drumscape is a macroscopic lens through which to understand drums, drummers, drumming, and the meanings and impacts they produce.

To once again borrow from and modify Kevin Dawe’s thoughtful discussion of the guitarscape, I suggest that the drumscape is a lens through which to consider (a) how the drum kit has been written about, thought about, and talked about; (b) the power and agency of the drum kit in culture and society; and (c) what kind of experience it is to play the drum kit (an experience involving both the mind and the body).20 Moreover, the drumscape is not simply a concept through which to analyse the drum kit as a phenomenon: it is also a process in itself. In other words, we can interrogate a multitude of events when drumscaping occurs: in the sound mixing of a recording or a live concert; in the transistorized drum machine sounds emanating from the car speakers of a moving vehicle, or the wireless headphones connected to a mobile device; in a performance by a busker in a city park; in a religious service as a gospel drummer entrains a congregation towards a spiritual experience; or in a clothing store as market researchers study whether adjustments in the BPM of a four-on-the-floor kick influence the speed with which customers shop. Drumscaping need not even be sonic in nature: it could be present in the logic of a conversation between band members over how songwriting royalties should be divided, and whether the drummer’s role merits a percentage (and if so how much); or the visual mapping of virtual music-making interfaces in a digital audio workstation that is informed in some way by an acoustic or electronic drum kit. All of these moments are both a part of the drumscape as a concept, and act as particular examples of drumscaping as a process.

Building on earlier theorizations of instruments by Simon Frith, Emily Dolan, and John Tresch, I propose that viewed through the lens of the drumscape, the seemingly simple term ‘drum kit’ can be understood from at least four different but related perspectives: the drum kit is a technology, an ideological object, a material object, and a social relationship.21 I will examine each in turn.

To understand the drum kit as a technology is to approach it as the application of an accumulated field of human knowledge (i.e. instrument-building) resulting in the creation a new music-making device. The technology of the drum kit not only solves particular problems of labour and space – allowing a single musician to play multiple percussion instruments at once – but also opens up new and extends the possibilities for musical expression. However, understanding the drum kit as a technology is not to artificially separate it from its social interaction and cultural use, as may science and technology studies (STS) scholars have observed. As Timothy Taylor once put it, for instance, music technology is ‘not separate from social groups that use it, it is not separate from the individuals who use it; it is not separate from the social groups and individuals who invented it, tested it, marketed it, distributed it, sold it, repaired it, listened to it, bought it, or revived it. In short, music technology … [is] always bound up in a social system’.22 Approaching the drum kit as a technology is not synonymous with treating it as an object either. The technology of the drum kit could easily be understood, for example, not as a thing made up of wooden shells, skins, and cymbals, but as a spatial arrangement or conceptual interface. The drum kit is a form of software as well as hardware. Non-drummers might initially puzzle over the following arrangement of abstract shapes, but any drummer would immediately be able to identify its meaning and implied use (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The drum kit as an abstract interface

The diagram below implies an overhead view of a typical setup for a righthanded drummer: a rectangular shape represents a bass drum, four dark grey circles from left to right represent a snare drum, two mounted toms, and a floor tom; and three light grey circles to represent from left to right a hi-hat, crash cymbal, and ride cymbal. This interface, even in abstract symbolic form, would be familiar enough to a drummer to imply not just a particular arrangement of drums and cymbals but also a rich set of performance practices – an amalgam of embodied techniques to coordinate one’s feet, hands, and body and enable a particular kind of music making. But of course, the implied sounds and uses need not be fixed in an open interface. Conceived as software, the drum kit allows for new codes to be written upon it: whether in the form of an electronic kit or displayed on a computer screen, drummers could happily (and routinely do) assign new voices and instruments to each element of the interface, or indeed add or remove elements entirely. The drum kit interface allows for the mixing, matching, and manipulation of sounds and performance techniques; the drum kit is a musically rich instrument precisely because drummers frequently borrow and repurpose its symbols and techniques in unexpected ways. A competent and creative drummer understands the instrument’s scripts but also subverts and rewrites them – navigating expressive pathways and possibilities that are musically distinct from other instruments.

Whether conceived of as an abstract interface or a concrete instrument, the drum kit as technology affords certain kinds of use and discourages others. It has the power to both enlarge and restrict the activity of music making. Understood from this standpoint (in other words, through the framework of actor network theory, or ANT), the drum kit is not a passive object, but an object with agency: it acts upon a drummer as much as a drummer acts upon it. The drum kit as technology encourages the user to experience music in a certain way (a very different way than, say, a guitar or woodwind instrument).

As an ideological object, the drum kit can be understood as a set of self-reinforcing ideas and values. The extent to which there is consensus surrounding these values informs social agreement of the drum kit’s function and purpose, and how it should and should not be used. The ideology of the drum kit contains received wisdom about its history, tradition, the accepted canon of significant drummers as artists (and the criteria by which they are judged to be significant), and its status as a sonic and visual icon. The ideology of the drum kit can also challenge prevailing music ideologies: from the perspective of drum kit culture, West African musical performance practices might be near the top of a hierarchy of musical value, while they might be located further down the value hierarchy embedded into the ideology of, for instance, a European instrument like the harpsichord or piano. There are also multiple and conflicting ideologies of the drum kit. In jazz drumming culture, for example, it might be taken for granted that an acoustic drum kit is a ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ drum kit, and an electronic or software drum kit is not; in electronic dance music culture, by contrast, this distinction might not matter at all. None of these ideas and values are absolute truths, but some sets of ideas have historically gravitated towards the orbit of the drum kit and the genre worlds surrounding it, while others have been repelled. And as ever, these ideologies shift and change over time.

As a material object, the drum kit can be understood as being made of particular elements and having particular physical and acoustic properties. Elsewhere I examine how the changing materials of the drumscape are mirrored by a wider shift in the materials used for commodity goods as a whole. A political ecology of the drum kit could be divided into three overlapping historical eras, each grouped by the principal materials used to manufacture the drum kit as a product: (1) renewable materials (i.e. the wood and metal used in traditional acoustic drums and cymbals); (2) non-renewable plastics and e-waste (i.e. the electronic circuitry and synthetic materials used in electronic drum kits); and finally (3) data (used in drum replacement and augmentation software).23 How this categorization plays out in detail represents an avenue for future research. Furthermore, the drum kit as a material object takes part in a global commodity industry, and is implicated in various commercial and industrial processes. Here the study of the drum kit could productively align with material culture studies more broadly.

As a social relationship, the drum kit only becomes a drum kit when it is used as such (in other words, when it is played) and when a relationship is established between the instrument and the person playing it.24 As Gareth Dylan Smith has observed, a drum kit can play a powerful role in shaping a drummer’s social identity.25 According to this approach, drum kits are not merely aids to the activity of drumming, but also powerful forces acting in relationship to their users, shaping drumming and its meaning in the process; and as it is woven into the texture of everyday existence (to paraphrase cultural theorist Langdon Winnner), the drum kit sheds its tool-like qualities and becomes part of our very humanity.26

Conclusions

To summarize, ‘what is a drum kit and how do we study it?’ is not a question where a short and simple answer will suffice. But this is a good thing. The drum kit is a living, mutable concept, and to study it properly is not a short exercise, but a lifelong inquiry that requires the establishment of a community of scholarship with constituents from both inside and outside the academy. In offering a few provocations concerning the historiography of the drum kit, the trajectory of drum kit studies, and the theorization of the drum kit, I do not claim to have fully answered any of the questions posed in this chapter, nor do I see a concept like the drumscape as a unified theoretical approach for drum kit studies as a whole. These are simply some tools to add to the toolbox, and it is my hope that the reader will find other useful tools to understand the drum kit, drummers, and drumming in the rest of this book.

Since jazz is an improvisational music, recordings offer perhaps the only valid way of its preservation.

I asked Chauncey Morehouse ‘do drummers really play that way, as we hear on the recordings?’ and he said ‘Absolutely not. Absolutely not.’

Misrepresented from the Beginning?

Recordings of interest concerning the drum kit began around 1913, when record companies began to take notice of dance crazes that were sweeping across the country.3 Yet, fourteen years later in 1927, an advert from The Talking Machine World, titled ‘Drum Notes Not Only Heard – But Identified!’,4 advertised a new home speaker, promising that ‘thousands of radio listeners will now realise for the first time that radio orchestras have drums when they hook up this new, improved Crosley Musicone’. While it is dubious as to just how clear the drum parts would have been on this new device, what is clear is that, to some extent, audiences were not used to hearing the drum kit on record at this time, as its newfound clarity was used as a point on which to market this new technology.

Recorded music is utilised in many different ways: most obviously, as entertainment for the general listener; profit-making commodity for the producer, or record label; and often, an object of study for the performing musician seeking to learn from these captured moments in musical history. On this last point, the opening quotations to this chapter demonstrate both the importance and the danger of these recordings for the aspiring drum kit player.

Historically Informed Performance (HIP) is an approach to the performance of Western art music, most commonly from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque eras. At its most basic level, it means performing music with special attention given to the performance conventions and technology present when the piece of music was composed. Taruskin’s collected essays on his critique of HIP music, Text & Act, is telling of his primary complaint with early music performers: that they give authority to a preserving text.5 ‘Central to this concept’, Taruskin explains, ‘is an idealised notion of what a musical work is: something wholly realised by its creator, fixed in writing, and thus capable of being preserved’.6 This, he argues, leads to HIP practitioners placing too much value on objects, and not enough on the people performing them, and insists that the ultimate authority rests with the interpreters rather than the texts, ‘for texts do not speak for themselves’.7 Performers seeking to recreate the styles of early jazz (or ‘HIJP’ performers, if I may insert the word ‘jazz’), often replace scores with early recordings made in the 1910s and 1920s. This chapter argues that, while this may prove beneficial for musicians studying the clarinet, trumpet, trombone, and the like, the drum kit may not be adequately represented in such a way. Perhaps drummers, more than other instrumentalists, have reason to doubt the validity of what Taruskin describes as ‘the text’.

My own experiences in performance, as a drummer playing early jazz music, have led me to reconsider what it is to play in this style, and where to look for my ‘text’. The role that early recordings play in jazz history determine how this music is interpreted today. This chapter will explore how drummers were represented on record, how this differed from their colleagues, and how HIJP performers today can balance the importance of recorded music with these considerations.

Drummers Disadvantaged in Early Recordings: Acoustic Age

From the introduction, the ‘Crosley Musicone’ demonstrates that playback equipment during the 1910s through the 1920s was ill-equipped to reproduce the sounds of early drum kits. However, playback equipment was not the only reason for this, as the problem began in the studio itself.

There is an abundance of primary sources describing the need to remove drums from the acoustic recording studio (pre-electric recording technology, between 1890 and 1925). Even in the final year of acoustic recording (1924) Variety magazine reports the apocryphal claim that ‘a drum has never been reproduced on wax’.8 While this is an exaggeration, they certainly were not reproduced well. Tales of bass drums making the recording needle ‘jump’ are well known, but every component part of the drum kit came under attack in the early recording studio. One of the earliest sources comes from early audio-enthusiast publication The Phonoscope, in 1899. It recommends that, while the studio should accommodate the snare drum, sound engineers should ‘omit the bass drum. It is likely to spoil the effect, as it does not record well’.9 Three years later, this was repeated in similar journal (The Phonogram), but with an additional piece of advice: ‘The bass drum and cymbals should be left out entirely, as they do not record at all well’.10 In 1903 one publication described the recorded bass drum fidelity as ‘disappointing’,11 and that same year the Edison Phonograph Monthly went further: ‘In making a band record bass drums are never used, as these blur or “fog” the record; cymbals are seldom used and snare drums in solo parts only’.12 As late as 1914 the same journal reported that the snare drum was no longer a solo instrument in terms of recording: ‘a trio of banjo, piano and drum, is worthy of special attention, as it is the first time these three instruments have been successfully recorded in combination by us’.13 This problem seemed to persist throughout the 1910s, as the advertising manager of the English division of Columbia Records recalled that in 1911 ‘the big drum never entered a recording room’.14 In 1914 Talking Machine World states ‘bass drums and cymbals should never be used, as they have a tendency to fog the record’.15 This advice was followed right from the 1890s and carried through to the 1920s; a photograph of the Original Memphis Five taken in 1922 shows them as a ‘recording unit’, with drummer Jack Roth seated at nothing but a snare drum (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Original Memphis Five, 1922: drummer Jack Roth on a snare drum only. Originally published in Record Research

Figure 2.1 shows drummer Roth’s bandmates pictured with their complete instruments: trumpet, trombone, clarinet, and grand piano. Many parts of Roth’s instrument – which in 1922 would feature a bass drum, multiple cymbals of different sizes and timbres, and an array of traps – are missing. Here, Roth played on a snare drum only. Replicating these recordings today necessitates choices about what to include and what to omit, complicating the accuracy or validity of the historic interpretation.

Moving later through the 1920s, an article from Melody Maker describes the conditions of a drummer in an acoustic studio as late as 1926:

Drums are the one set of instruments which cannot be used in recording in anything like the same manner as they are when playing to an audience. This is because the notes of these instruments induce a sound wave, the vibrations of which are so long that they have little or no effect on the sensitive diaphragm which is the ear of the recorder. The Bass Drum does not record at all at least, it merely gives a dull rumbling sound nothing like it really is, and the side-drum, although recordable for solo work (such as is found in such numbers as ‘Toy Drum Major’) only succeeds in blurring the general rhythm when used in conjunction with other instruments. When recording all the drummer has to do is fill in the cymbal beats and now and again perhaps add a few effects such as clog-box, chimes and such like. I know of a drummer who drew his recording fee five guineas in this case for playing just one beat on a cymbal, and if ever they stop using pianos in syncopated bands I shall try to be a drummer at least when the band is playing for the discs.16

Recollections from studio musicians of the time tell a similar story, though contradict on what parts of the drum kit were preferred. Drummer Chauncey Morehouse (1902–1980) and bandleader Paul Whiteman (1890–1967) are reported to have not used bass drums in the acoustic studio.17 Cornetist Wild Bill Davidson (1906–1989) recalls his recordings with the Chubb-Steinberg band in 1924–1925: ‘Drums couldn’t be used on the recordings, because the needle used in the process would jump the grooves when a drum beat; cymbals were used instead’.18 Abbey ‘Chinee’” Foster (1900–1962) recalls his 1925 recordings as a similar experience, only adding woodblock to the mix.19

While photographic evidence of bands in the acoustic studio are scarce, those that exist show an inconsistent picture, and almost never a full drum kit. One studio, Gennett Records, had a fortunate habit of photographing its many bands, albeit only bands comprising of white members, that passed through its doors through the first half of the 1920s. These images, all taken by photographer William Dalbey, captured each band in the same room, position, and theme (musicians pictured with their instruments), making for an informative comparison.20 Of these eight photographs, taken between 1923 and 1928, five of these show drummers Stan King, George Gowans, Doc Stultz, Tom Gargano, and Earl McDowell playing on nothing more than a ‘trap rack’ with minimal traps (one cymbal, one woodblock), with no drums used at all. The recording made in this session, Davenport Blues, is of poor audio quality, but what percussion there is to hear supports what is in the picture; there is a prominent muted cymbal rhythm but little else. This setup was described by New Orleans Musician Charlie Bocage (1900–1963), who recalled that in his recording experience with drummer Louis Cottrell and the Piron band, these were the only drums allowed.21 One photograph shows drummer Vic Moore using what would be a full drum kit (Chinese cymbal, Turkish cymbal, cowbell, woodblock, and snare drum) if it were not for the fact that there is no bass drum. His snare drum is heavily dampened with cloth or rubber (much like today’s practice silencers that we place on acoustic kits), which would have greatly affected the performance. It is this photograph,22 along with another depicting drummer Gargano23 that led some to the conclusion that it was a matter of space that kept the bass drum at the studio door;24 however, this can’t be the case, as there are two photographs that show Hitch’s Happy Harmonists showing drummer Earl McDowell using a bass drum with his full set-up (which includes cymbal and Chinese tom-tom).25 A snare drum is likely present, obscured behind the bass drum. Unfortunately this isn’t reflected in the corresponding recordings; the full set of drums depicted here cannot be heard any more than the recordings that came out of the other depicted sessions. It is, of course, possible that this was brought in merely to showcase the band’s logo on the drum head, knowing a photograph was to be taken on those sessions.

The status of the drum kit in the studio is, at best, complicated and inconsistent; one can find evidence of bass drums present on early recordings (the famous 1917 Original Dixieland Jass Band sessions shows remarkable clarity from the bass drum). Strangely, this is often more common with earlier records from the late 1910s than the 1920s, and speaks to the infancy of the recording process itself: inconsistencies are likely explained by the engineer one had on the day; while some would indeed take risks, many, perhaps most, did not.26

It wasn’t just the engineers that held the fate of the drummer’s sound – at this time, everything was in the hands of the ‘A&R’ manager (‘artist and repertoire’ manager, sometimes referred to as the ‘recording master’). One such A&R manager was Eddie King, involved in making records from as early as 1905, before moving to Victor Records, then leaving for Columbia Records in 1926.27 A well-known authoritarian, an A&R executive like King could have serious consequences for the drum kit in the studio. Drummer Chauncey Morehouse recalls that King only allowed his own drum equipment to be used. An ex-drummer himself in the John Phillip Sousa Band, King had meticulously experimented with his various percussion items, and had his pre-approved house cymbals which he insisted every drummer use.28 Musician Nat Shilkret (1889–1982), who remembers King as a good drummer in his day, recalls that King had a cymbal he was fond of, which he brought to Victor’s recording studios, and that he would go into the recording room and hold the cymbal himself ‘ready to strike it at spots at which he thought it would help’. Shilkret remembers that he and the other younger engineers were tired of this, and began hitting the cymbal themselves unbeknown to King, to chip away at the cymbal until King was compelled to throw it away.29

Drummers Disadvantaged in Early Recordings: Electric Age

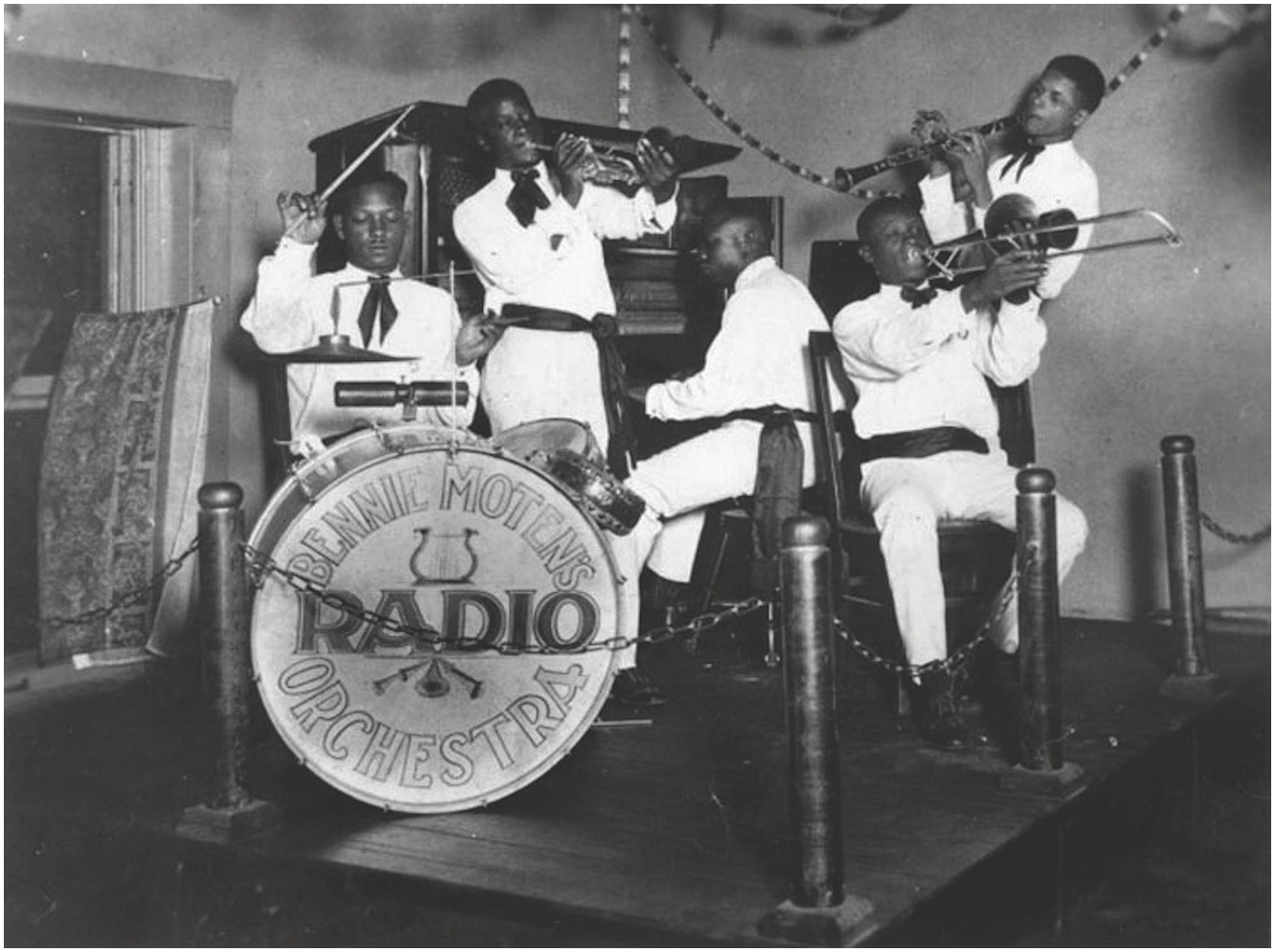

It was radio broadcasting, and the revolutionary technology it employed, that grudgingly dragged the recording industry out of the acoustic era. Radio’s superior electric technology was able to record drum kits clearer than ever before, years before the recording studio caught up. Figure 2.2 shows two bands in the radio studio using full drum kits in broadcasts from 1922. These are among the earliest photographs of a microphone being used to capture a full drum kit performance.

However interesting it is to see full drum kits on radio broadcasts as early as 1922, it remains unclear what one actually heard at the other end of an early radio broadcast. A report on the drum kit’s sound over radio that year casts doubt that this greatly improved on the acoustic method: ‘traps carry well over the radio because of their sharp, clearly defined characteristics. The bass drum is too low and slow’.30 In 1925, Radio Age describes the conditions of radio recording as being similar to what we have heard of the acoustic studio: ‘the drums are eliminated entirely’.31 One year later Radio Broadcast wrote of the state of drums on radio: ‘Perhaps in 95 per cent of the radio receivers in use to-day, it is impossible to hear a note as low as that given by a drum’.32

Similarly, when the recording industry followed radio and went electric in 1925, this was by no means an overnight change for the drum kit. The last half of the 1920s were an ‘adjustment period’ for this technology, and while good reports of drum kit recordings start to appear, inconsistencies remain. Clarinettist Barney Bigard (1906–1980) recalls a recording session with Duke Ellington in 1928 – almost certainly recorded in an electric studio, considering the date – where drummer Sonny Greer turned up but had to sit out because the studio simply could not record the drums.33

It is true that electrical recording rapidly improved as recordings moved into the mid-1930s, though by this time this technology brought with it a new swing style, and it was too late for the early jazz bands to immortalise their sound with clear fidelity. Early drummers did appear in later years on clear recordings demonstrating their techniques – most notably, Baby Dodds (1898–1959),34 who made recordings discussing his 1920s drumming style – though these musicians could not unhear the different styles they had adopted since the days of when they used techniques they were purporting to demonstrate.

The power that recording technology, and the way it developed, had over a band is demonstrated by a 1925 Billboard article commenting on the switchover from acoustic to electrical recording, and how this would have consequences, not just on clarity and fidelity, but on what instruments would be favoured to the downfall of others:

Much is being said for and against the new electrical recording process with which a few of the larger phonograph laboratories are experimenting. Altho [sic] many improvements over the old system are noted, there is no question … that many more changes will have to be made before the new way can be said to be perfect. For the first time in recording history, the piano is distinctly heard on the finished record when the electrical process is used. But it is observed that the banjo, an important factor in recording due to the piano’s comparative silence, provides a clash under the new system, and so leaders who have been anxiously watching results have, in many cases, decided to eliminate banjos from future dates. Also, drums, never before used on dates, will enjoy an unusual vogue now, as they will be able to be heard to distinct advantage.35

Drums ‘in’ or ‘out of vogue’, as described above, were determined by the technology that could or could not capture them. Rather than merely adding fidelity, early electrical recording technology complimented some instruments to the disadvantage of others. Today some listeners regard the banjo as an old-fashioned sound in jazz – perhaps its demise was due to changes in recording techniques. This seems possible, given that it also predicts the rise of the saxophone in jazz music, as saxophonists ‘will find electrical recording a boon … Thus many saxophonists formerly unable to plan dates will now be able to enjoy an extra source of revenue’. The article continues: ‘Recording orchestras are busy figuring out new recording combinations under the new plan. As previously mentioned, instruments formerly neglected will be put in and others now used may have to be cut out, temporarily at least’.36

Beyond the Record

Clearly the recording process, and its restrictions, represented drummers in a way that was not indicative of the way they played on stage. In terms of not being able to record certain components of the drum kit, leaving parts at the studio door. This omission can rightly be described as restrictive and certainly drummers have therefore been misrepresented on record. Perhaps players today interested in HIJP should ignore or place less importance on these records than other members of the band. However, these studio restrictions ultimately changed the way that drummers played on their instrument (as a whole, or whichever parts were allowed in). When we consider these changes in style that recording necessitated (or perhaps we should say, facilitated?) perhaps what may be thought of as ‘restrictions’, could instead be viewed as part of the drum kit’s story. Much like other forces that shaped the drum kit (as an instrument, and in terms of performance practice), perhaps recording restrictions, and the measures that drummers took accordingly, could be embraced by the HIJP performer today. Once we examine what performance practices came out of these restrictions, it becomes obvious that these carried through to live performance outside of the studio.

One such studio influence was how drummers dealt with the volume of their instrument. Drummers were encouraged to give unequal weighting to parts of the drum kit, such as sharp-sounding traps (e.g. woodblocks, cowbells, rims of the drum) to cut through and be heard, or to play with brushes where they would not have otherwise, in order to avoid saturating the recording horn. Baby Dodds speaks of this:

When I first began to record, I was with the Oliver band … It was then I began to use wood blocks, the shell of the bass drum and cymbals more in the recording than I usually had, because they would come through. Bass drum and snare drum wouldn’t record very well in those days and it was my part to be heard.37

Dodds also recorded with Jelly Roll Morton, on the famous Hot Pepper sessions. Dodds recalls of Morton: ‘Because he wanted the drum so very soft I used brushes on Mr. Jelly Lord. I didn’t like brushes at any time but I asked him if he wanted me to use them and he said “Yes”’. How many drummers since have wanted to sound like Baby Dodds, and mimicked a sound that Dodds himself did not enjoy? Similarly, Dodds discussed playing the washboard on some of his recordings for his brother Johnny.38 Ed Allen (1897–1974) recalls ‘washboard was a good substitute for drums, as bass drums wouldn’t record in those days anyway’.39 The drum kit and the way it is played, has been partially shaped by its own volume, and the way recording studios and acoustic bands reacted to this volume. Volume is something that has hampered, influenced, and inspired drum kit performance. It continues to be an issue when performing, practicing, and discussing the drum kit’s place in popular music today.40

How many of these studio habits were brought forward into live playing? Would brush playing be as prominent in jazz today if it were not so encouraged amongst drummers in the early days of recording (and during this crucial stage of the instrument’s development)? We associate washboard playing with the early jazz of this era, but not from reading about it – from listening to it. Practitioners of HIJP would benefit from considering the bigger picture, beyond the record: the studio, its restrictions, and its influence. Our contemporary understanding of jazz history reflects the practices of those bands captured on recording, as opposed to the bigger picture of jazz practice – in and out of the studio – at any given time of recording.

A Cycle of Influence

The picture becomes blurred as to what is considered ‘live’ and ‘studio’ performance when one considers the far-reaching influence these records have on subsequent generations of drummers. Jazz recordings have been, from their beginnings through to today, an essential teaching tool for musicians learning and developing the genre.41 For example, Bix Beiderbecke is said to have taught himself trumpet by listening to the recordings of Original Dixieland Jass Band.42 Cornetist Jimmy McPartland (1907–1991) describes his experience, as his friends heard, for the first time, recordings of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings: ‘We stayed there from about three in the afternoon until eight at night, just listening to those records one after another, over and over again. Right then and there we decided we would get a band and try to play like these guys’.43 The influence of early recordings was the inspiration for the formation of many bands. The next stage was using these recordings to learn the style, which McPartland then describes:

What we used to do was put the record on … play a few bars, and then get all our notes. We’d have to tune our instruments to the record machine, to the pitch, and go ahead with a few notes. Then stop! A few more bars of the record, each guy would pick out his notes and boom! We would go on and play it. It was a funny way to learn, but in three of four weeks we could finally play one tune all the way through.44

Records were often a way for other drummers listening to develop their own styles. However, while clarinettists and trumpet players could learn the solos and licks on the records that would appear in the ephemeral setting of a nightclub note-for-note, the aspiring drummer was not so fortunate. Drummers either would not be able to hear the parts they wished to learn, or if they could, would they want to? And, the important question for HIJP performers today: should they? As recorded jazz music began to circulate throughout the United States and beyond, this affected the way in which a new generation of jazz musicians would learn the drum kit, and interpret their role in live performance. These musicians would then record the next generation of jazz records, and a cycle of influence would be born. During the spring of 1948, Baby Dodds travelled to Europe with Mezz Mezzrow’s band, and commented on how his drumming had been interpreted by Europeans listening to his records:

While abroad I came into contact with quite a few of the European jazz bands. A fellow named Claude Luter has a little band in France and he’s got the same instrumentation that King Oliver had … He plays a lot like my brother because he learned to play by listening to his records. They studied the old records very carefully and tried to get everything down as perfectly as they could. Since they only had the records to teach them they played on the style of our music. Of course on the records they could hear only the cymbals and wood blocks and that is what they mostly used, since they couldn’t hear the snares and bass drum as distinctly.45

When HIJP drummers today play early jazz, just where are they taking their technique from? Recordings have undoubtedly provided the most interesting, informative, and rewarding tool when researching how this music was played, yet in the early recording studio not all instruments were created equal. The representation of drummers on record should be considered in order to project an accurate picture of what was really played in dancehalls in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, but also in order to consider how and why drummers are represented and portrayed the way they are today.

Conclusion

What is it to record: events, opinions, music? In order to record, we need a mediator between past and present. Just as one cannot remove the historian from the history, technology is the inevitable barrier between what was played then, and what is heard now. This chapter began by implying that the drum kit was comparatively disadvantaged by this technology, and misrepresented, but perhaps this is a weighted statement. It certainly was most affected; the effects ranged from a culling of the instrument’s component parts (and in this sense records perhaps shouldn’t be used so stringently by the aspiring HIJP drummer) to legitimate performance considerations that have defined the sound of early jazz to modern listeners. We may wish that drummers were given an equal footing from the start, but the fact is that the sound of early jazz – the sound we may wish to replicate or recreate – is defined by these early studio restrictions, and they should add to the balance of considerations the HIJP drummer must make in their performance practice.

Introduction

In a fiery 1956 sermon captured on grainy, black-and-white film, Reverend Jimmie Snow explains to his Nashville congregation why he preaches against rock and roll. ‘I know how it feels’, he intones, ‘I know the evil feeling that you feel when you sing it. I know the lost position that you get into in the beat. Well, if you talk to the average teenager of today and you ask them what it is about rock-and-roll music that they like, the first thing they’ll say is the beat, the beat, the beat!’1 Like many social leaders who condemned rock and roll, Snow located the allure and impact of this music, commonly called ‘beat music’ or simply the ‘big beat’, in its powerful percussive accompaniment. The central and most distinctive feature of the rock-and-roll beat was its emphatic, relentless snare drum accents on ‘two and four’, the conventionally ‘weak’ beats of the measure – the so-called backbeat. Shocking though it was to many in the 1950s, the backbeat soon became and remains one of the single most prevalent features of Western popular music. This chapter explores the origins of the backbeat, charts its early history on record from the 1920s to the 1950s, and considers how it has functioned as a meaningful musical signifier and cultural agent.

For the purposes of this chapter I limit my discussion to backbeats that are exclusively rhythmic in nature, serving no harmonic or other musical function. Thus, neither the weak-beat piano, banjo, or guitar chords common in nineteenth-century songs and dance music, ragtime, early jazz, country, and blues, nor the slap-back bass in swing, Western swing, and rockabilly will be considered. Rather, I focus on the emergence of the backbeat as a convention in drum kit performance practice, typically played on the snare drum. The distinctive, piercing ‘crack’ (or ‘whack’, ‘slap’, ‘spank’, etc.) of the snare drum and its potential for extreme volumes make the drum kit backbeat different in kind from the off-beat piano, banjo, guitar, or bass rhythms cited above.

Backbeating As Signifyin(g) Practice

Reverend Snow was among many who linked the rock-and-roll backbeat to juvenile delinquency and violence. Justifying the ban on rock-and-roll shows in Jersey City in 1956, Mayor B. J. Berry asserted ‘this rock-and-roll rhythm is filled with dynamite, and we don’t want the dynamite to go off in Roosevelt Stadium’.2 Critics also blamed rock and roll for promoting lascivious dancing and sexual promiscuity, claiming that its beat replicated the rhythms of sex. Condemnations of beat music commonly resorted to racist language associating the ‘primitive’ rock-and-roll beat with the ‘savage’ instincts of ‘inferior’ races. Few were more forthright than Asa Carter of the White Citizens Council of Alabama, who asserted ‘rock-and-roll music is the basic, heavy-beat music of the Negroes. It appeals to the base in man, brings out animalism and vulgarity’.3 As Steven F. Lawson summarizes, ‘the language used to link rock with the behaviour of antisocial youths was couched in … racial stereotypes. Music Journal asserted that the “jungle rhythms” of rock incited juvenile offenders into “orgies of sex and violence” … The New York Daily News derided the obscene lyrics set to “primitive jungle-beat rhythms”’.4 As late as 1987, conservative critics could assert that rock’s ‘notorious’, ‘evil’ backbeat ‘is very dangerous since it owes its beginnings to African demon worship’.5

Kofi Agawu has deconstructed the myth of ‘African rhythm’ – the notion that ‘blacks … exhibit an essential irreducible rhythmic disposition’ – exposing it as a white invention often deployed in the justification of racial hierarchy.6 As Ronald Radano notes, ‘the primitivist orthodoxy of “natural rhythm”’ can also serve as ‘a means of affirming positive identities in an egregiously racist, nationalist environment’.7 For instance, as Isaac Hayes recalled, ‘it was the standard joke with blacks, that whites could not, cannot clap on a backbeat. You know—ain’t got the rhythm’.8 Similarly, blues musician Taj Mahal interrupted a 1993 performance to chide his German audience for clapping on the downbeat. ‘Wait, wait, wait … This is schwarze [black] musick’, he instructs the crowd. ‘Zwie, vier! One, TWO, three, FOUR!’9

The affirmative potential of such strategic essentialism notwithstanding, reducing the backbeat to an inbred racial trait is profoundly limiting and, like all essentialisms, has dangerous ramifications. This is borne out by the fierce backlash against rock and roll, ‘the heavy-beat music of the Negroes’, part of a larger racist backlash in the age of Brown vs. the Board of Education, the Little Rock Nine, and Emmett Till. Far from being an inbred musical predisposition of black people, the backbeat emerged as a strategic cultural response to specific social, historical, and musical conditions. Understanding this history requires that we consider the practice of backbeating before the development of the drum kit during the first decades of the twentieth century. Indeed, as all drummers know, one does not need a drum kit to perform the multi-limb rhythmic beating that is the essence of drum kit performance practice.

Samuel Floyd has traced various elements common in African-American music – including call-and-response patterns, pitch-bending, and unflagging off-beat rhythms – to the ring shout, a ritual adapted from West African sacred traditions.10 Participants sing and chant over the rhythms of their shuffling feet, hand claps, and other body percussion. As Floyd explains, the ring shout also exemplifies the practice of ‘signifyin(g)’ central to West African and African-American expressive culture, as participants extemporaneously expand on traditional texts with additional verses, embellishments, commentary, and so forth. Theorized by Henry Louis Gates, Jr, signifyin(g) involves the interpretive elaboration on received ideas, narratives, texts, etc., often as a means of resisting or inverting dominant ideologies and power relationships, and it underlies much African-American vernacular culture, from ragging tunes to rap battles.11 As a signifyin(g) practice, backbeating is a means of responding to and reinterpreting the conventional ‘strong’ downbeat of Western music – of simultaneously acknowledging and resisting it, of playing with and working against it, of inverting it, enhancing it, and making it groove.

Incarceration, Hard Labour, and the Backbeat

In ways both metaphorical and real, backbeating has functioned as a meaningful response by African Americans to the brutal oppression of slavery and the long, violent aftermath of the Civil War. For many black southerners, conditions scarcely changed after abolition. Laws targeting black people fed a network of prisons that effectively replicated the conditions of slavery. Trivial offences or bogus charges could land black citizens in labour camps such as the notorious Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana, Parchman Farm in Mississippi, or the Darrington State Prison Farm in Texas. Each are known for their brutal conditions, but also for field recordings conducted by John and Alan Lomax beginning in 1933.

These recordings establish African-American prison songs as one of earliest repertories on record that commonly features emphatic backbeat accompaniments. For example, ‘Long John’ (1933), sung by a group of prisoners led by ‘Lightning’ Washington, is based on a story from antebellum black folklore. Representative of the trickster hero central to many signifyin(g) texts, Long John is a fugitive slave who leads a nationwide chase, outwitting his would-be captors at every turn. Washington lines out the tale, lacing it with Biblical references, and the group repeats each line to the accompaniment of axes striking on the backbeat.12 As is common in trickster tales, Long John uses cunning and wit to subvert established power structures, just as the backbeat subverts conventional notions concerning ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ beats.

In their percussive accompaniments, these prisoners transform the tools of their oppression into musical instruments, making them potential tools of liberation. By signifyin(g) on the downbeat, the prisoners transform the rhythms of forced labour into compelling grooves, creating the possibility of experiencing the body, not only as a site of violent oppression, but also as a potential site of creativity and pleasure. Here backbeating constitutes a strategy for survival and resistance, providing historical precedent for John Mowitt’s assertion that the rock-and-roll backbeat ‘define[d] the substance of a modest, but tenacious pedagogy of the oppressed … a practical wisdom about how to “strike back” and “make do” under conditions of adversity and cynical humiliation’.13

The Lomaxes also recorded songs performed during the inmates’ few leisure hours, such as ‘That’s All Right, Honey’ (1933) by Mose ‘Clear Rock’ Platt. Platt boasted to Lomax of his various jailbreaks and his powers of evasion. In an audacious display of storytelling (and signifyin[g]), he explains that he ran so fast that the ‘splat-splattin’’ of his feet was mistaken for the sound of motorcycle engine, and that his shirttail had caught fire, which was mistaken for a taillight. ‘Dey calls me “Swif-foot Rock” ‘cause de way I kin run’, he explains, adding ‘white man say he thought I mus’ have philosophies in my feet’.14 Platt’s philosophical feet can be heard, faintly tapping downbeats during his singing of ‘That’s All Right, Honey’, each foot-tap answered by a much louder clapped backbeat. Platt sings line after line of affirmative lyrics over the up-tempo ‘stomp-CLAP’ groove, celebrating freedoms that, ‘sho ‘nuff’, will be his. Platt’s exuberant performance testifies to the uplifting power of backbeating; such a spirited performance within the confines of a system designed to break the spirit constitutes a powerful act of resistance, of beating back.

Backbeating in Pentecostal Worship

Body percussion had long been practiced in Western Africa, described by European explorers as early as 1621.15 It took on greater significance in the United States, where drumming among slaves was feared and outlawed in many places. While slave holders could ban drums, they could not ban the bodies that sustained their economy, and accompaniments to sacred song and dance moved from drums to African-American bodies. As Jon Michael Spencer explains, ‘To the African the drum was a sacred instrument possessing supernatural power that enabled it to summon the gods into communion with the people … [and] percussiveness produced the power that helped move Africans to dance and into trance possession … With the drum banned, rhythm … became the essential African remnant of black religion in North America … It empowered those who possessed it to endure slavery by temporarily elevating them … to a spiritual summit’.16

Among Christian denominations, African-American Pentecostal and Holiness (also called Sanctified) churches took up body percussion most fervently. Pentecostalism emphasizes spirit possession, achieved through rhythmic song and dance, and dozens of recordings from the 1920s demonstrate the centrality of backbeating to Pentecostal worship. In Memphis alone, Bessie Johnson and Her Memphis Sanctified Singers, Elder Lonnie McIntorsh, and the Holy Ghost Sanctified Singers made recordings with consistent handclapped backbeats that fuel impassioned vocal performances as in, for example, Johnson’s ‘Keys to the Kingdom’ (1929). Another remarkable example, ‘Memphis Flu’ (1930) by Elder Curry and His Congregation, is a proto-rock-and-roll song, replete with Little Richard-style eighth notes hammered out on the piano’s high, percussive register to solid, communal backbeating. Such congregational backbeating is the audible presence of community; all participants contribute to a unifying, thoroughly embodied groove, which constitutes the primary vehicle for spiritual communion. No wonder Pentecostal preachers like Reverend D. C. Rice would defend percussive worship music, insisting that ‘people need to feel the rhythm of God’.17

Pentecostal music was not only a form of praise, but often a means of protest, with statements of resistance embedded in religious contexts. Most explicit are the various ‘Egypt’ songs, wherein the deliverance of Israelites from Egyptian captivity is understood to prophesy the deliverance of black people from racist oppression in the United States. The earliest vocal recording I have found with consistent backbeating throughout (excepting the introduction) is ‘Way Down in Egypt Land’ (1926) by the Biddleville Quintette. The song confronts the darkest depths of slavery, ‘waaaaaay down in Egypt land’, but the exuberant, rhythmically charged performance, driven by handclapped backbeating, makes clear that this is a celebration of deliverance. Perhaps the earliest drummed backbeating on a vocal record occurs on Elder J. E. Burch’s stirring ‘Love Is My Wonderful Song’ (1927), fuelled by emphatic snare backbeat accents over driving bass drum quarter notes.

A fairly direct line connects Pentecostal backbeating to 1940s rhythm and blues. Prolific gospel recording artist Sister Rosetta Tharpe collaborated with the equally prolific Lucky Millinder on several recordings. Millinder had been leading bands on record since 1933, when he took over the Blue Mills Rhythm Band, but none of his recordings feature prominent backbeats until his work with Tharpe.18 Their 1941 collaboration, ‘Shout Sister, Shout’, features Pentecostal-style congregational backbeating placed at the forefront of the mix during choruses. Millinder would again foreground clapped backbeats on ‘Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well’, a gospel parody describing a worship service that evolves into a spirited, boozy bash. Recorded in 1944 with vocalist Wynonie Harris, the record was a massive hit, spending eight weeks atop the ‘race’ chart in 1945 and crossing over to #7 on the pop chart. Handclapped gospel backbeats propelled Harris’s next hit, ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’ (1948), a cover of Roy Brown’s ‘Galveston Whorehouse Jingle’.19 Whereas backbeats accompany only the choruses of ‘Shout Sister, Shout’ and ‘Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well’, handclapped backbeating accompanies the entirety of ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’, excepting the introduction, where drummer Bobby Donaldson plays emphatic snare backbeats thickened by loose, ‘dirty’ hi-hats, which, along with wah-inflected trumpet growls and insinuating saxophone squeals, set a steamy scene for the entry of gospel clapping. Here the sacred and the secular, the spiritual and sexual meet on two and four.

Sex and the Backbeat

Euphemistic references to sex such as ‘rocking’ were commonplace well before the rise of rhythm and blues, especially in a strain of the blues, sometimes called ‘hokum’ blues, built around clever double entendres and thinly veiled references to sex. Hokum blues songs often address the world of prostitution, and many were performed in brothels and bawdy dance halls, where musicians entertained and played music for dancing, particularly the kind of dancing that might encourage subsequent assignations.20 No other strain of the blues from the 1920s and 1930s features as flagrant backbeating as the hokum blues, where the ‘rocking’ celebrated in the lyrics finds a parallel in the back-and-forth motion between bottom-heavy downbeats and penetrating backbeats.

For instance, Margaret Webster’s ‘I’ve Got What it Takes’, recorded in 1929 with Clarence Williams’s Washboard Band, features salacious lyrics set over an infectious, backbeat-based shuffle groove played on the washboard by drummer Floyd Casey. Among the most prolific recording artists of the 1920s and 1930s, Williams recorded with Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, among others, in addition to numerous recordings under his own name. I credit some of his success to the compelling percussive accompaniments provided by Casey. As these records demonstrate, the washboard was well suited to the recording technology of the day, offering a variety of percussive timbres, from the deep ‘thump’ of the wooden frame to the piercing, metallic scrape in the high register. Here the washboard constitutes a kind of miniature drum kit that produced better results in the studio than could be achieved easily with drums. Like the axes and other tools that accompanied prison songs, the washboard represents an instrument of labour that was radically repurposed and deployed in the celebration of freedoms.

Allusions to prostitution are common in the songs of Memphis Minnie, the influential blues singer, songwriter, and guitarist, who, like many musicians of her era, played at brothels and often ‘entertained’ in more ways than one.21 At a remarkable 1936 session, Minnie recorded seven sides, each featuring an unidentified percussionist playing stark, consistent backbeats on either a washboard or woodblock. Most of these songs address sexual politics, some making direct references to prostitution, such as ‘Black Cat Blues’ with the refrain ‘everyone wants to buy my kitty’, Minnie’s saucy swagger punctuated by pulsating backbeats. These are perhaps the earliest recordings to feature backbeating in the context of guitar-based blues, establishing Memphis Minnie as a rhythm-and-blues pioneer.

As Hazel Carby, Shayna Lee, and others have shown, in such songs women performers reclaimed female sexuality from the objectifying male gaze and projected empowering representations of female agency and desire.22 In this context, the backbeat is an apt metaphor for sex, rollicking between steady downbeats and penetrating backbeat accents, imparting an embodied experience that renders these assertions and celebrations of sexuality all the more compelling. Not surprisingly, some of the most influential drummers in the development of rock and roll, including prolific session drummers Earl Palmer and Hal Blaine, and Elvis Presley’s drummer D. J. Fontana – all early masters of the backbeat – started out playing in strip clubs providing rhythmic accompaniments to steamy floor shows.

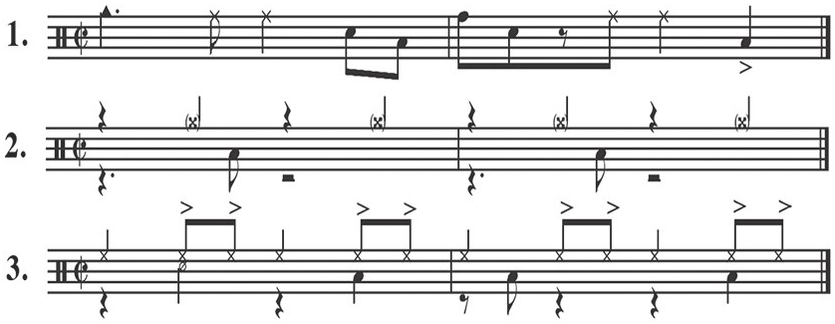

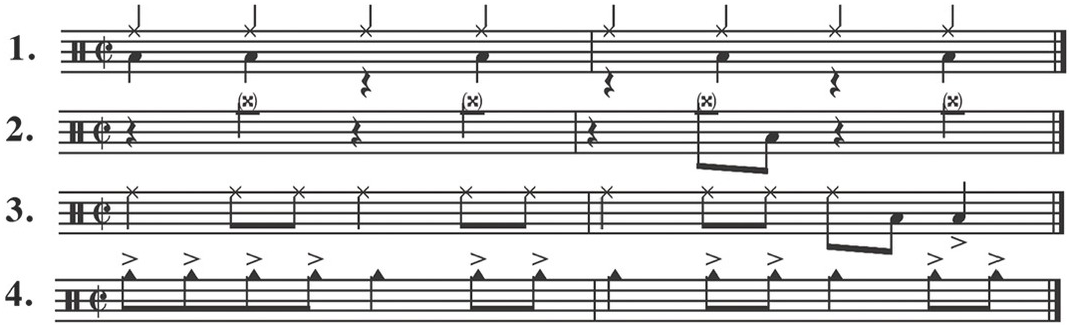

Shout Choruses, Afterbeats, and the Kansas City School

Earl Palmer has often been noted for his role in standardizing the rock-and-roll beat. He played drum kit on Fats Domino’s ‘The Fat Man’ (1949), an early hit that features consistent backbeats, and his recordings with Little Richard were among the earliest to feature the backbeat in conjunction with straight eighth-note hi-hat or ride cymbal patterns (as opposed to the swung or shuffled accompaniments typical of rhythm and blues and early rock and roll). Palmer identified the Dixieland ‘shout chorus’ as the inspiration for his earliest use of a consistent backbeat.23 In the shout chorus, the ensemble takes up boisterous figures while the rhythm section plays heavy ‘weak’ beat accents. For instance, drummer Andrew Hilaire plays emphatic snare backbeats during the last chorus of ‘Black Bottom Stomp’, recorded in 1926 with Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers. As an isolated, deliberately ‘unruly’ section, the shout chorus stands out as exceptional, as a moment of abandon during which the normal rules do not apply, or rather, in carnivalesque fashion, are inverted.

As early as the 1920s, then, drum-kit backbeating was associated with the kinds of excess and disorder critics would impute to the rock-and-roll beat decades later. The term ‘shout’ chorus alludes to the kind of spirited performances associated with black sacred music, but I have come to think of such choruses in instrumental jazz and later rhythm and blues as ‘cut-loose’ choruses, a metaphor with particular resonance for black people contending with the legacy of bondage. Typically, these backbeat-driven choruses support and impel particularly intense solos that transgress the dynamic, scalar, and timbral restraints in place during ‘regular’ choruses.