Electoral decisions are not exhaustively described by the ideological proximity between voters and candidates. A Downsian-type model of party competition holds that parties or candidates take positions in a policy space and that voters choose the alternative that is ideologically closest to them (Downs Reference Downs1957). Scholars have noted that this view does not provide a comprehensive description of party competition—neither conceptually nor in terms of the empirical implications’ accuracy (Adams and Merrill Reference Adams and Merrill2003, 161–2). In an early critique of the Downsian model, Stokes (Reference Stokes1963) points out that there are numerous issues like the economic prosperity of a country, where voters—by and large—do not diverge with respect to the desired policy outcomes. Therefore, competitors do not campaign by staking out policy positions on these scales. Instead, competition is driven by public perceptions of competence or actual quality differentials (Aragones and Palfrey Reference Aragones and Palfrey2004; Buttice and Stone Reference Buttice and Stone2012).

Recent research including the quality aspect of political competition has typically assumed that there are two factors that determine the electoral success of competitors, a policy- and a non-policy-related component, i.e. ideological proximity and candidate valence. These candidate evaluation factors are typically treated as orthogonal in the formal contributions on the subject (Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita Reference Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita2009; Serra Reference Serra2010). Empirically, however, it is difficult to separate the two factors and to capture their relative importance for individual vote choices due to the well-known rationalization effects when trying to capture candidate quality and policy proximity from surveys (Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1986; Bartels Reference Bartels2002a; Lebo and Cassino Reference Lebo and Cassino2007). Specifically, it is challenging to determine the familiarity of voters with the policy profiles of candidates and, hence, whether they are able to correctly assess their ideological proximity to the candidates.

In this paper, I propose to estimate a comprehensive indicator of the valences of candidates competing in the German federal election of 2013 while controlling for the effect of ideological proximity. This is done by explicitly familiarizing voters with the policy positions of district candidates and making vote recommendations based on a comparison between the individual policy preferences and the candidates’ profiles. After informing voters about their correct vote choice from a spatial perspective (cf. Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk1997; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008), voters are invited to indicate their prospective vote choice. The systematic residual between the correct vote and the actual prospective vote choice provides a comprehensive estimate of the candidates’ valences. The research thus makes two important contributions. One, it introduces a novel technique for estimating candidate valences and also provides a data set of candidates’ valence advantages in the German federal election of 2013. Two, the research investigates determinants of variations in the size of candidate valences.

The remainder of this article begins by briefly outlining the valence factor of vote choices as well as components of candidate valence. Third section describes the data and method that is applied in the empirical investigation. The association of the explicit valence indicators and candidate status is the subject of fourth section. Fifth section provides some additional robustness checks. Sixth section concludes.

The Valence Component of Vote Choices

In his seminal critique of the dimensional model of politics, Stokes (Reference Stokes1963) argues that numerous issues structure political competition where neither voters nor political actors differ with regard to preferred outcomes (cf. Stokes Reference Stokes1992). Faced with such valence-issues, political competition shifts to perceptions of competence or the ability to deliver upon promises to create the universally desired outcomes. Since the proposition of the valence concept by Stokes, numerous contributions have been put forth that investigate how non-policy factors are related to candidate behavior and electoral success. Several formal contributions on the subject have introduced valence in Downsian-type models to explore variation in candidate position-taking induced by valence differentials (Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001; Aragones 2002; Schofield Reference Schofield2004; Schofield Reference Schofield2007; Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita Reference Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita2009; Hummel Reference Hummel2010; Bernahrdt, Camara and Squintani Reference Bernhardt, Camara and Squintani2011) and to derive equilibria in multi-party or multi-dimensional competition settings (Ansolabehere and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000; Schofield Reference Schofield2003).

Empirical contributions on the valence theory of politics have investigated how specific non-policy characteristics of candidates are related to electoral outcomes. The most well-known factor that alters vote choices is the incumbency status of the candidate (Cox and Katz Reference Cox and Katz1996; Berry, Berkman and Schneiderman Reference Berry, Berkman and Schneiderman2000; Burden Reference Burden2004; Hogan Reference Hogan2008; Stone et al. Reference Stone, Fulton, Maestas and Maisel2010). But candidate valence is a multi-dimensional concept that has been taken to mean a variety of things in the literature, such as “incumbency, greater campaign funds, better name recognition, superior charisma, superior intelligence” (Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001, 862). A useful distinction to classify aspects of candidate valence was put forth by Stone and Simas (Reference Stone and Simas2010). The authors assert that it is possible to differentiate between campaign valence and personal character valence. While the former encompasses characteristics like name recognition and campaign funds, personal character valence covers factors such as “integrity, competence, and dedication to public service” (Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010, 373).Footnote 1

The formal contributions on the valence theory of voting have dealt with the multi-dimensionality of the concept by defining comprehensive valence parameters to capture the range of factors contained in the concept. Conversely, the empirical literature has struggled to come up with comprehensive measures of candidate valence. The challenge of generating comprehensive empirical estimates of valence is related to the difficulty of capturing valence from survey evidence. Faced with systematic distortions in the candidates’ perceived policy profile in survey data (Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1986; Granberg and Brown Reference Granberg and Brown1992; Merrill, Grofman and Adams Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001), it is unclear to what degree proximity voting and candidate valence drive individual vote choices.

Consequently, the empirical research has frequently relied on shorthand indicators for candidate valence such as the incumbency status of candidates. While the research has consistently shown that this indicator is systematically and positively related to electoral outcomes, it cannot provide a comprehensive image of the valence advantage of candidates. Moreover, it has the implausible feature to not produce variation in valence among the group of incumbents. One alternative measure to estimate the effect of valence on electoral outcomes was recently proposed by Clark (Reference Clark2009). In an extensive hand coding of several Western European countries, the author records political events that are related to public perceptions of parties’ “competence, integrity and unity” (Clark Reference Clark2009, 112). As expected, the measure is negatively related to the vote share of parties in subsequent electoral cycles. While the work is a commendable contribution, the effect of events on party images only provides evidence at the level of the character valence in the terminology of Stone and Simas (Reference Stone and Simas2010).Footnote 2 Campaign valence factors of incumbents like increased funds or access to staff should be largely unaffected by political scandals. Another two recent contributions grapple with the difficulty of generating empirical and comprehensive measures of candidate valence by employing expert ratings of candidate valence. Stone and Simas (Reference Stone and Simas2010) investigate the long-standing proposition in the formal literature that there are position-taking incentives of valence advantages while Buttice and Stone (Reference Buttice and Stone2012) show that candidate quality alters individual vote choices and that the size of the effect is conditional on the position-taking of candidates.

The present research project intends to provide a comprehensive estimate of the valence advantages of candidates for the German Bundestag. The subsequent investigation of the measure assesses how it is related to determinants of candidate valence. Drawing on the distinction between campaign valence and personal character valence by Stone and Simas (Reference Stone and Simas2010), I suggest that campaign valence and candidate visibility in particular should be most closely related to the estimated candidate valence. Stone and Simas propose that voters intrinsically care only about the personal character valence of candidates, whereas campaign valence is rather an accidental by-product of the nature of the competition. While the assertion is plausible that voters care most about quality of character, elements such as integrity and honesty are comparatively difficult to assess for voters. Conversely, factors that drive the visibility of candidates should be more closely related to the comprehensive indicator as voters need to be familiar with candidates in order to consider them viable electoral alternatives.

The dominant factor of campaign valence in the comprehensive valence measure is particularly true for the German electoral system that is dominated by parties. In the two-tiered German electoral system, a list vote determines the overall composition of the Bundestag, although voters can personalize their choices by selecting a nominal district candidate (Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2009). As the electoral law is governed by the proportional component and therefore by the behavior of parties, the nominal candidates are frequently relatively unknown quantities. Consequently, the valence component of candidates should primarily be driven by the need to make themselves visible (campaign valence) before hoping to showcase their integrity (character valence). Stone and Simas suggest in their outline of the two dimensions of valence that there is a systematic relationship between character valence and campaign valence where candidates with a character valence advantage might be more successful in attracting campaign funds (Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010, 373). Conversely, it seems unlikely that there is a pronounced effect of character valence on campaign valence in the German case where individual candidacies are generally less dependent on third-party funds for their campaign activities. For example, nominal candidates in the 2013 German federal election only covered about 20 percent of their campaign expenses with third-party donations on average (Rattinger et al. Reference Rattinger, Roßteutscher, Schmitt-Beck, Weßels and Wolf2014). Put differently, political systems that are dominated by parties are unlikely to exhibit substantial effects of personal character valence on either campaign valence or electoral outcomes. In an extension of the arguments put forth by Stone and Simas (Reference Stone and Simas2010), I suggest that it is possible to differentiate between candidate visibility at the national level and at the local level. There are elements that increase the valence of candidates such as holding a governmental office (national level) and elements that are more strictly tied to the district competition such as the number of campaign appearances in the electoral district (local level).

A Comprehensive Measure of Candidate Valence

One of the principal challenges for investigating candidate valence from surveys is the difficulty to assess whether voters are familiar with the policy positions of candidates. Candidate placements on policy scales are subject to distortions and rationalizations (Bartels Reference Bartels1988; Granberg and Brown Reference Granberg and Brown1992; Merrill, Grofman and Adams Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001), impeding a differentiation between the valence and proximity component of vote choices. To circumvent this limitation, this paper employs evidence from a vote advice application of German nominal candidates during the 2013 federal election campaign. The online tool explicitly provided voters with information on the policy positions of their district candidates and made vote recommendations based on voters’ policy preferences. Subsequently, voters were invited to indicate their prospective vote choices and in numerous instances voters did not select the candidate that was indicated as ideologically closest by the vote advice application. This sequence of the data collection allows explicitly ruling out the possibility that voters’ selections are driven by their unawareness of the candidates’ policy positions. Instead, candidate valence trumped proximity considerations. In the remainder of this section, I sketch the data collection and outline the generation of the valence estimates. This section closes with an overview of the operationalizations of the variables that should be related to the valence parameters.

During the German federal election campaign of 2013, the curators of the platform (http://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de) assembled a survey with a binary response format—the Kandidatencheck—and invited all nominal candidates to participate. The questionnaire covered both core issues of the electoral campaign (e.g., the retirement age, austerity policies, and internet surveillance) as well as long-term concerns of the German political system (e.g., minimum wages, temporary staff policies, and renewable energies). Moreover, the items were selected to cover most major policy areas and the two ideological dimensions that structure electoral competition in Germany—an economic left-right dimension on the one hand and a cultural dimension on the other (Bräuninger and Debus Reference Bräuninger and Debus2008; Pappi and Brandenburg Reference Pappi and Brandenburg2009). To alleviate concerns regarding potential effects of biased issue selection on the vote recommendations, the items were assembled by the platform’s curators in collaboration with the political editors of those public and private media outlets that featured the survey on their web appearances to generate publicity for the platform and to inform voters about the available alternatives.Footnote 3

The candidate responses were made publicly accessible in the form of a vote advice application in the weeks before the election (Cedroni and Garzia Reference Cedroni and Garzia2010; Schultze and Marschall Reference Schultze and Marschall2012), allowing voters to log on to the platform and take an identical survey. After inputting their responses, the system calculated an agreement score between the voters and their nominal candidates and output the list of candidates—ordered by the proximity of the stated policy preferences.Footnote 4 Having been provided a vote recommendation, users of the platform were invited to respond to a supplemental questionnaire. The additional questionnaire collected, inter alia, information on the users’ prospective vote choices in the upcoming federal election.Footnote 5

To estimate the candidate valences, I model the individual vote choices and control for policy distance as provided by the vote advice application, thus capturing the valences in candidate-specific residuals. First, the distance between the users’ policy preferences and the candidates’ policy profiles is calculated for each user.Footnote 6 The choice for one of the five district candidates is then included in a mixed conditional logit model where the policy distance is the main explanatory variable.Footnote 7 I further include party fixed effects in order to control for selections that are driven by party label rather than candidate-specific factors.Footnote 8 The model has the following form—the vote choice of individual i for competitor j from the choice set S i of the five district competitors is given as

and

where U j are random effects with a normal distribution, estimated to be equal for all individuals faced with the same choice set. The candidate-specific random effects are treated as estimates of the comprehensive candidate valence.Footnote 9 There are two caveats regarding the underlying data. One, the platform has not provided users with the option of weighting the issues before calculating the policy distances. The model applied by the vote advice application therefore effectively assumes that every agreement/disagreement is equally important, whereas in fact the influence of issues on vote choice might vary by voter. The effect of unweighted vote recommendations should be that voters more frequently select candidates who were not labeled as ideologically closest by the platform. By the same token, voters might have based their candidate selections on additional policy considerations if they were irritated by the vote recommendation. To be sure, the ideal solution for this imprecision in the estimates would have been to offer voters the possibility to weigh the issues. However, absent this state of affairs, it seems unlikely that making unweighted vote recommendations would greatly affect the valence estimates. First of all, the unweighted policy distances should be strongly related to the weighted policy distances, thus creating imprecision only in edge cases. What is more, it is plausible to assume that non-weighted recommendations do not systematically favor one candidate over another, i.e. if the estimated candidate valences were elevated, they would be elevated across the board. Put differently, it would be of greater concern if voters systematically considered aspects in their candidate selections that favored candidates from one party over those from another. For example, it is plausible that a subset of voters would be more inclined to select candidates from one of the two main parties, regardless of policy proximity. This effect should, however, be controlled for by the party-specific fixed effects.

A second concern regarding the underlying data is related to the non-random sample of vote advice application users. As Marschall (Reference Marschall2014) shows in his contribution on the subject, there is clear evidence that users’ socio-demographic statuses typically do not match the population baseline. The most concerning factor among the various deviations from the baseline is a higher average educational attainment (Marschall Reference Marschall2014, 100–1). It thus needs to be considered whether the self-selected user sample might bias the estimated candidate valences. Previous research has shown that better educated voters are more likely to take personal characteristics of candidates into account when making vote choices (Glass Reference Glass1985; Lau Reference Lau1986; Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk Reference Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk1986). It can thus be assumed that more voters in the sample apply valence-based voting compared with an unbiased sample. However, as this contribution is interested in candidate-specific valences rather than individual vote choices, there is no reason to expect biases due to an over-educated sample as there is no fixed underlying metric of the valence estimates. More frequent valence voting, therefore, still generates systematic variation in the valence indicator.

There were 299 electoral districts in the German federal election of 2013. For the estimation of the indicator I drop all districts where one of the five competitors has not participated in the Kandidatencheck as voters need to be familiarized with the policy positions of all viable candidates in order for the argument to hold.Footnote 10 Despite a sample size of ~36,000 respondents, there is fairly little data for each electoral district. Consequently, I discard all districts with a coverage of fewer than 50 respondents overall. Both restrictions—a full candidate sample and at least 50 observations—limit the data set to 114 electoral districts and 570 nominal candidates.

Table 1 presents the estimates from the candidate selection model. In line with expectations, the policy distance is negatively and significantly associated with the individual vote choice. The party fixed effects are also highly significant and in line with prior expectations. The Christian Democrats (baseline) have the highest party valence, the Social Democrats a little less so, the three smaller parties are trailing behind. The majoritarian electoral system on the district tier generates a strong tendency for two parties—the CDU/CSU and SPD—to dominate the district vote. Even though Die Linke has won several East German electoral districts in recent years, this is not evident in the party fixed effects, possibly suggesting that the electoral results of successful Die Linke candidates are more strictly tied to candidate quality.

Table 1 Conditional Logit Model: Candidate Selection

Note: *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

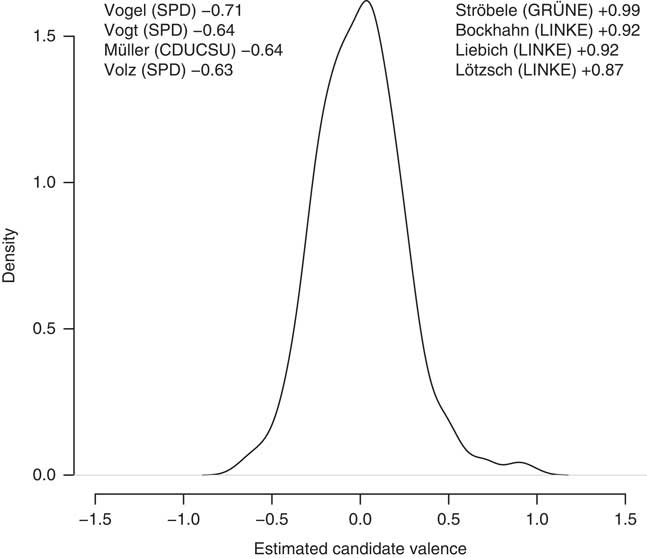

Figure 1 displays the distribution of the valence indicators—the candidate-specific random effects U j . The candidates with the four highest and four lowest values are printed at the top of the figure. Both Stefan Liebich (Die Linke) and Gesine Lötzsch (Die Linke), party chairwoman in the years 2010–2012, have been able to win district mandates in previous electoral cycles—Lötzsch in the years 2002, 2005, and 2009, Liebich in 2009—despite their membership in one of the minor competing parties. Their successful nominal campaigns and the position of party chairwoman for Gesine Lötzsch suggest a valence surplus due to visibility that is reflected in the estimates and in their subsequent successful electoral bids in the federal election of 2013. Similarly, Steffen Bockhahn (Die Linke) was party chairman of the state-level party organization in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in the years 2009–2012 and has won the mandate in the district Rostock—Landkreis Rostock II in the federal election of 2009. In addition, Bockhahn was party chairman in the municipal council of Rostock. Therefore, despite coming in second in the race for the district mandate in 2013, he was nonetheless quite visible in the district which is plausibly echoed in a high valence indicator. Finally, Hans-Christian Ströbele (Grüne) has also won a nominal mandate since 2002 as the first and only candidate from Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, suggesting a similar high valence advantage for him.

Fig. 1 Distribution of candidate valence parameters Uj from the Conditional Logit Model in Table 1. The candidates with the four highest and four lowest values are shown at the top of the figure.

Turning to the candidates with the lowest valence estimates, all four competitors have achieved electoral results in the bottom quartiles of their respective parties.Footnote 11 Among the four candidates, only Ute Vogt (SPD) was able to win a mandate for the Bundestag via the state-level party list. In fact, after a particularly poor showing during the previous federal election, where she came in third after the Christian Democrat and the Green candidate with a mere 18.0 percent of the district vote in Stuttgart I, she resigned from the position of state-level party chairwoman in Baden-Württemberg. The unusual state of affairs for a West German Social Democrat candidate to come in third continued in 2013 when Ute Vogt was placed third yet again with only 16.6 percent of the district vote. Götz Müller (CDU), the fourth candidate with a particularly low valence indicator also had a plausibly poor showing in his district where he scored an exceptionally low 13.7 percent of the votes. He was placed fourth, being surpassed by all three competitors from the left-wing parties. This fourth place is even more astounding as the 2013 federal election concluded with a comparatively strong result for the CDU due to the popularity of chancellor Merkel, which gave a boost to most Christian Democratic nominal candidates, prompting one news outlet to label Müller as “Merkel’s loneliest fighter.”Footnote 12 These first, unsystematic observations provide some indication that the estimated valence parameters do reflect the candidates’ non-policy advantages and disadvantages.

It was argued that the visibility of candidates in the district and at the national stage should be positively related to the valence parameters. Regarding national visibility, candidate valence should increase if candidates have won the district mandate in the previous electoral cycle. Candidates can also increase their visibility and hence their valence by holding an office at the national stage. To capture this empirically, information on all governmental (Minister and parlamentarische Staatssekretäre) and parliamentary offices (Parlamentspräsidium and Fraktionsvorstände) was collected. As indicators of local candidate valence, the number of campaign events a candidate has attended were selected as well as the number of personal posters a candidate has put up. Both variables were gathered from self-reported information in the candidate survey that was conducted by the project “Making electoral democracy work” (Blais Reference Blais2010).

Character valence is more challenging to capture. The best available indicators of character valence are the widely applied survey ratings of candidates’ character traits (cf. Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk Reference Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk1986; Funk Reference Funk1996; Bartels Reference Bartels2002b; Hayes Reference Hayes2005). Such trait ratings are frequently collected for top candidates. However, as no ratings are available for the rank-and-file candidates that ran in the German electoral campaign of 2013, I rely on three structured variables instead that should be related to candidate character and perceptions of character valence. One aspect that features prominently in German candidates’ self-presentation are academic titles. Most candidates with a PhD will display their title on campaign posters to indicate superior intelligence and competence (Manow and Flemming Reference Manow and Flemming2011). Accordingly, data on whether candidates have a PhD was collected. Moreover, information was assembled on the candidates’ professions as indicated on the electoral ballot. As before, more prestigious professions might signal a greater electoral viability to voters. The information of the candidates’ professions was systematized by the Bundeswahlleiter Footnote 13 and put into a structured scheme of professions. Based on this coding, all candidates were assigned a value of the job prestige that is associated with their profession (Frietsch and Wirth Reference Frietsch and Wirth2001). One final aspect of candidate quality that will be included in the analysis is physical attractiveness, which has consistently shown to be associated with candidate selections (Rosar and Klein Reference Rosar and Klein2005; Rosar and Klein Reference Rosar and Klein2013; Rosar and Klein Reference Rosar and Klein2014).Footnote 14 Table A1 in the Appendix provides summary statistics of the independent variables.

Explaining Valence Advantages of German Candidates

The estimated valence indicator should be systematically associated with the proposed components of candidate valence. Table 2 presents the results from three ordinary least square models that regress the factors on the estimated valence parameters. Model 1 contains indicators of candidate visibility at the national stage—the candidates’ incumbency status and whether or not candidates were office-holders in the previous electoral cycle. In line with expectations, the incumbency status is positively and significantly associated with the estimated candidate valence. The same is true for office-holders. The size of the office-holder variable is surprisingly small, however, which might be explained by missing observations in this variable. Some of the most well-known office-holders have not participated in the Kandidatencheck, such that several incumbent ministers are missing in the data set. Therefore, the office variable contains comparatively many office-holders with somewhat minor offices.

Table 2 Ordinary Least Square Regressions: Distance-Based Valence

Note: Party fixed effects not displayed.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Model 2 considers indicators of local candidate visibility—the logged number of campaign events a candidate participated in as well as the logged number of personal campaign posters candidates had in their electoral districts.Footnote 15 Both variables are positively and significantly associated with the estimated candidate valence. The incumbency status is still positive in model 2, but no longer meets the ordinary criterion for statistical significance. Needless to say that particularly the number of personal campaign posters a candidate can put up is systematically related to the incumbency status of candidates.

Model 3 presents the estimates from a model that regresses candidate character aspects on the valence indicator, specifically whether or not candidates have a doctorate, their job prestige, and physical attractiveness. While the title variable is plausibly signed positive, there is no systematic evidence that either a doctorate or the candidates’ job prestige is systematically related to the estimated candidate valence. Conversely and in line with previous research, the candidates’ attractiveness is positively and significantly associated with the estimated valence indicator. Nonetheless, the model fails to explain much of the variation in the valence parameters. It thus needs to be concluded that—at least in the party-dominated German political system—candidate visibility is the more important condition for candidates to appear a viable electoral alternative to voters. Aspects of the candidate character, on the other hand, bear little relation to electability.

Non-Proximity and Non-Party Preferences

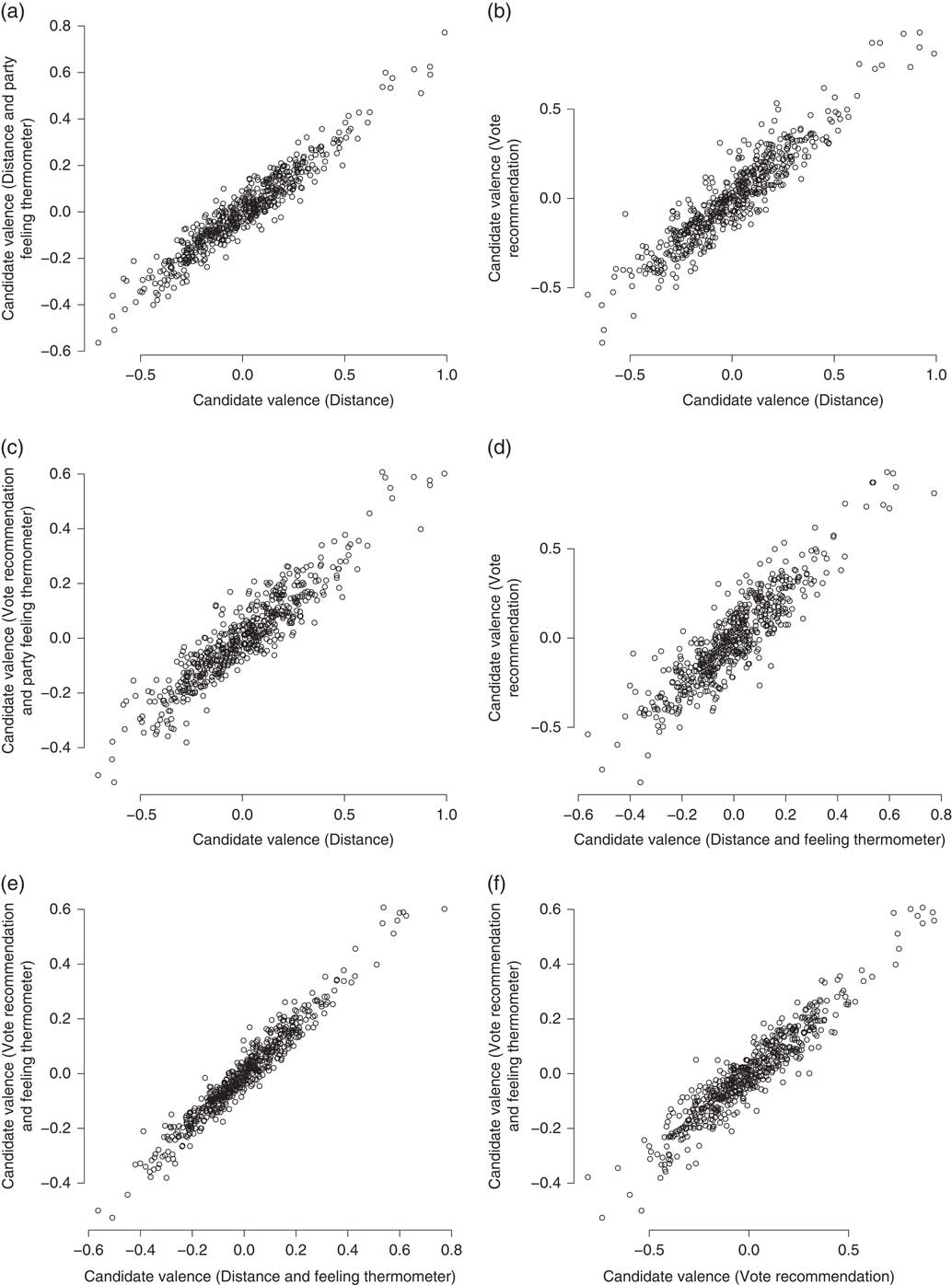

To capture candidate valences, a model was estimated that explains individual prospective vote choices with the policy distance to the district candidates. The model contained party fixed effects to control for the party label. It is possible to go beyond this model specification and even control for voters’ long-term party preferences. Table 3 presents the results from a model similar to the one proposed in A Comprehensive Measure of Candidate Valence section with the addition of party feeling thermometers. The first model in the table is identical to the model in Table 1. It is reprinted for reference. Model 2 includes the feeling thermometers in addition to the policy distance and the party fixed effects. In line with expectations, there is a positive and highly significant association between the party feeling thermometer and the candidate selection, above and beyond the party fixed effects. Nevertheless, the estimated candidate valences in the two models are well aligned, as shown in the top left panel of Figure 2. The figure shows the candidate-specific random effects from models 1 (x-axis) and 2 (y-axis) in Table 3. Despite controlling for the party feeling thermometers in the latter model, the estimated candidate valences are close to the 45º line, suggesting no dependence of the estimates on whether or not the additional control variable is included.

Fig. 2 Dependence of the estimated candidate valences on the various model specifications. The alternatives are the Pure Distance Model (Table 1), the Distance Model With Feeling Thermometer (model 2 in Table 3), the Vote Recommendation Model (model 1 in Table 4), and the Vote Recommendation Model With Feeling Thermometer (model 2 in Table 4). The valence estimates are stable across the various model specifications.

Table 3 Conditional Logit Model: Candidate Selection

Note: *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

So far, the spatial component of the vote choice was controlled for by employing the distance between the voter preferences and the candidates’ policy profiles. One might argue that the theoretical account requires modeling the actual vote recommendation rather than the policy distance between candidates and voters. Therefore, a binary indicator was generated that is set to 1 if a candidate was recommended by the platform and 0 otherwise. The two models from the previous table were re-run, where the policy distance was replaced with the binary vote recommendation. Table 4 presents the results from this analysis. Again, there is a strong and positive effect of the vote recommendation on the candidate selection. Not surprisingly, the parameter estimate shrinks when the party feeling thermometer is added in model 2. Figure 2 displays the candidate random effects from the four models in all possible combinations.Footnote 16 There is a high agreement between the estimated candidate valences, regardless of the model specification. Thus, there is good evidence that the estimated parameters are not driven by the specific modeling choice.

Table 4 Conditional Logit Model: Candidate Selection

Note: *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Conclusion

Voters do not always choose the candidate or party that is ideologically closest to them. Scholars have provided ample evidence that non-policy factors such as the visibility, the perceived integrity, or decisiveness of candidates can tilt vote choices in favor of candidates that do not advocate the most compelling policy profile for individual voters. Despite the plausibility of the proposition and the evidence to back it up, it has proven difficult to capture candidates’ valence advantages from voters directly in the form of surveys. On the one hand, this is due to the uncertainty regarding the awareness of voters of the candidates’ policy profiles and to the well-known distortion effects in the minds of voters on the other.

This contribution has attempted to capture a comprehensive valence indicator of German candidates from data generated by a vote advice application. By making vote recommendations based on the overlap between individual policy preferences and the policy profile of district candidates, it was possible to take proximity out of the equation and to capture the valence advantages of candidates. I have provided evidence that the estimated valence indicator is associated with ordinary measures of candidate valence, particularly variables that increase the visibility of candidates are strongly associated with the proposed measure. Conversely, there is little indication that character valence is associated with the estimated candidate valence.

As a party-dominated political system, Germany is a least likely case for discovering character valence effects. Therefore, finding little systematic relation between the character valence factors and the comprehensive candidate valence indicator is strictly tied to the specific German electoral system with its strong non-majoritarian component—the mixed-member proportional system (Shugart and Wattenberg Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001; Gschwend, Johnston and Pattie Reference Gschwend, Johnston and Pattie2003; Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa Reference Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa2005). The candidate as an independent political entity is of much greater importance in the US context where the valence concept originates. Consequently, the substantive results cannot generalize beyond the specific political system under investigation here. This is all the more true, as more candidate-centered electoral systems should engender a more systematic link between character valence and campaign valence (Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010, 373), where candidates with a character valence advantage might be able to raise their campaign valence. What should generalize, however, is the technique for estimating candidate valences by explicitly supplying voters with information on the candidates’ policy profiles. As vote advice applications are an increasingly common tool to help citizens make informed vote choices, scholars should take the opportunity to apply evidence from such tools in similar analyses to capture the non-spatial component of voting.

One upshot of this research program is a data set on the valences of German nominal candidates. The data are well suited to find applications beyond the substantive interest of the present contribution. For instance, several publications have recently considered the behavioral incentives of German candidates—both within the parliamentary assembly (Stratmann and Baur Reference Stratmann and Baur2002; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010; Stoffel Reference Stoffel2013; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2015) and on the campaign trail (Wüst et al. Reference Wüst, Schmitt, Gschwend and Zittel2006; Zittel and Gschwend Reference Zittel and Gschwend2008). It seems likely that a high valence advantage would affect position-taking in both cases as a higher valence translates to a greater electoral safety. Future research should strive to combine the research interests of these literatures and assess how the proposed valence parameters are related to candidate and MP behavior.

This article has considered prospective vote choices as an instrument for calculating the valence advantages of German candidates. One aspect that has not been covered is the question which voters are more likely to stray from the vote recommendations and to select candidates with a valence advantage. Future research could apply similar evidence to consider factors that increase the likelihood of valence voting. I would suggest that politically more sophisticated voters are more likely to disregard the vote recommendations for two reasons. One, more sophisticated voters have a better intuition of the valence advantages of candidates. It requires a minimum amount of political sophistication to make the connection between candidates in an electoral race and their campaign appearances. Two, some previous research has shown that more sophisticated voters are more likely to take personal characteristics of candidates into account when casting their vote (Glass Reference Glass1985; Lau Reference Lau1986; Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk Reference Miller, Wattenberg and Malanchuk1986; for an opposing point of view see Pierce Reference Pierce1993). Glass (Reference Glass1985) argues that sophisticated voters are aware that they cannot foresee the issues that will come up throughout the electoral cycle. Therefore, their best option is to select a candidate with commendable character traits which could be observed as higher levels of valence voting by political sophisticates.

Appendix

Table A1 Summary Statistics of Independent Variables