I

Over the past two decades, a series of influential papers have found institutions to be powerful predictors of economic and financial development that exert persistent effects over time (e.g. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005; Banerjee and Iyer Reference Banerjee and Iyer2005; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny2000a; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer1999, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008). The power of these findings derives from a strong correlation between exogenous institutions, or the variables used to instrument for these institutions, and current institutions that are highly correlated with economic and financial development today. These statistical findings are given economic significance by building a theory of how institutions adopted or inherited in the distant past have exerted persistent effects over time. But because few studies have explored whether correlations between institutions and economic and financial outcomes hold in the past, we cannot be certain the alleged persistence of the effects of these institutions passes the scrutiny of history (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2011). If these relations were not significant in the past, the correlations observed today might instead be the product of events that have not been considered and incorporated into the statistical work of these institutional studies.

Of particular interest in this article is the law and finance hypothesis, which states that a country's legal origin is a powerful predictor of its investor protection laws and its financial development. In this article, we examine law and finance in Britain c.1900, which has been a fly in the ointment of the law and finance hypothesis (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008, p. 319). First, it appears that ownership had separated from control before or around c.1900 (Hannah Reference Hannah2007a, Reference Hannah2007b; Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2012; Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2015) or, at least, that ownership and control separated in the twentieth century before shareholder protection law was strengthened (Cheffins Reference Cheffins2001, Reference Cheffins2008; Franks, Mayer and Rossi Reference Franks, Mayer and Rossi2009). Notably, studies of corporate ownership in the United States and Brazil in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also suggest that ownership separated from control well before the strengthening of investor protection, which is contrary to the predictions of the law and finance theory (Hilt Reference Hilt2008, Reference Hilt2013; Musacchio Reference Musacchio2009).

Second, according to Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2003), the UK had the most developed stock market in the world in 1913, which is contrary to the law and finance hypothesis given the weak state of UK shareholder protection law. However, the accuracy of Rajan and Zingales's figures has been questioned by, among others, Sylla (Reference Sylla2006), who suggests that stock market capitalisation in the United Kingdom c.1913 was perhaps overestimated by conflating bonds and stocks. In addition to this issue, La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008) highlight that companies in many countries cross-listed in the London stock market, for example, and, because what matters is the legal regime of the country in which a company is listed, companies cross-listed in London were perhaps borrowing Britain's legal system and, hence, not subject to the legal tradition of their home country. This could possibly result in an overestimate of the size of the domestic British capital market.

Our contribution to these debates is twofold. First, we provide a new estimate of the market value of the British share and corporate bond markets, which does not conflate bonds and shares and which differentiates between the market value of domestic and colonial and foreign securities. In order to measure the market capitalisation of the domestic UK share and bond markets c.1900, we code by hand all the securities listed in the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence and Investor's Monthly Manual to generate new point estimates for 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929. We collect data on the legislation under which companies were incorporated to help us differentiate between companies incorporated in the UK, and hence subject to UK law, and those incorporated in foreign countries. Because most companies in the UK incorporated via two different routes – a high-shareholder-protection route and a low-shareholder-protection route – we also differentiate between companies based on the legislation they were incorporated under. Our results imply that there is no correlation between investor protection laws in the UK and the size of its domestic capital market, which casts some doubt upon the law and finance hypothesis.

Second, we compare the UK's investor protection laws with those of other countries c.1900 to ascertain whether the UK is a unique case in this era with its weak shareholder protection law and highly developed capital markets. We collect and examine fragmentary evidence on investor protections, specifically, evidence of creditor and shareholder rights across countries at the turn of the twentieth century. This evidence reveals that, across common law and civil law countries, creditor rights included in bankruptcy laws were quite similar and that the protection of shareholders did not rely strongly on government or court enforcement of shareholder rights (i.e. there was convergence on weak shareholder rights). The implications of this finding are threefold. First, Britain was not unique in having weak shareholder protection and developed capital markets c.1900. Second, there was a divergence of investor protection laws during the twentieth century. Third, the similarity of investor protection in the past across legal origins suggests that legal origin does not appear to explain differences in investor protection which are manifest today.

We also examine potential substitutes for statutory legal protection, which may resolve the puzzle of the coexistence of a thriving stock market and weak shareholder protection. One possibility, which may have the most merit, is that firms used their contractual freedom to provide protection to shareholders via their articles of association, which were simply their constitutions or corporate byelaws.

As well as augmenting the broader literature on the law and finance hypothesis (see La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008) and Xu (Reference Xu2011) for surveys), this article also contributes to the literature which examines the law and finance hypothesis from a historical perspective – see, for example, Cheffins (Reference Cheffins2001); Campbell and Turner (Reference Campbell and Turner2011); Fohlin (Reference Fohlin2007, Reference Fohlin2012); Guinnane et al. (Reference Guinnane, Harris, Lamoreaux and Rosenthal2007); Lamoreaux and Rosenthal (Reference Lamoreaux, Rosenthal, Glaeser and Goldin2006); Malmendier (Reference Malmendier2009); Musacchio (Reference Musacchio2008, Reference Musacchio2009); Roe (Reference Roe2006); Coyle and Turner (Reference Coyle and Turner2013); and Musacchio and Turner (Reference Musacchio and Turner2013). Notably, as with the current article, most of this literature does not lend much in the way of support to the law and finance hypothesis. But, unlike the current article, most of these studies are not broadly comparative in nature (with the exception of Fohlin Reference Fohlin2012). However, Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2003) and Bordo and Rousseau (Reference Bordo and Rousseau2006) adopt a historical and comparative perspective, but neither find much evidence to support the law and finance hypothesis.

The aticle is structured as follows. Section ii briefly outlines the law and finance hypothesis. Section iii examines both statutory shareholder and creditor law in the UK c.1900. Section iv generates new estimates of the market value of the UK's domestic share and bond markets for 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929. Section v compares shareholder and creditor rights for a group of common and civil law countries c.1900. Section vi discusses potential substitutes for statutory shareholder protection. Section vii concludes.

II

A significant number of recent papers find legal origins to be strongly correlated with current indices of rule of law (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Beck, Demirguç-Kunt and Levine Reference Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine2003b), financial development (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998; Djankov, McLeish and Shleifer Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007; Beck, Demirguç-Kunt and Levine Reference Beck, Demirguç-Kunt and Levine2003a, Reference Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine2003b), the regulation of entry and labour (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer Reference Djankov, La Porta, Lopez De Silanes and Shleifer2002; Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer Reference Botero, Djankov, Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2004), and the concentration of ownership (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer1999) among other things. In particular, the work of La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny2000a) and La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2006, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008) relates financial development to the extent of a country's legal protections for investors (shareholders and creditors), arguing that ‘when investor rights such as the voting rights of the shareholders and the reorganisation and liquidation rights of the creditors are extensive and well enforced by regulators or courts, investors are willing to finance firms’ (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny2000a, p. 5). In other words, investors are willing to finance firms as shareholders or creditors because the law empowers them vis-à-vis directors and insiders and reduces the agency costs associated with the arm's length financing of firms. This results in lower costs of capital, higher risk-adjusted returns for investors and a greater supply of investment capital. Notably, research has found financial markets and financial systems to be more developed in countries that have legislated more shareholder and creditor protections (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998; Levine Reference Levine1998, Reference Levine1999; Levine, Loayza and Beck Reference Levine, Loayza and Beck2002).

The world is divided by the law and finance into two main legal traditions, civil law and common law, and four legal families, common law, French civil law, German civil law, and Scandinavian civil law. La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008, p. 3) find that ‘legal rules protecting investors vary systematically among legal traditions or origins, with the laws of common law countries (originating in English law) being more protective of outside investors than the laws of civil law (originating in Roman law) and particularly French civil law countries’. According to La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998, p. 126), legal origin is a valid exogenous variable for explaining investor protections and financial development because legal systems were adopted involuntarily through either conquest or colonisation and, hence, legal families can be viewed as exogenous to a country's financial development.

Most of the evidence against the law and finance hypothesis has come from scholars taking a more historical approach. For example, Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2003) and Roe (Reference Roe2006) argue that rather than legal origins or investor protection laws, differences in financial development are largely driven by a country's experience of military invasion, war and occupation during the twentieth century, which resulted in different attitudes and policies towards financial and stock markets. It so happens that civil law countries experienced much greater levels of conflict, destruction and occupation in the twentieth century than common law countries.

III

In this section, we are interested in the investor protection law on the books in the UK at the turn of the twentieth century. In particular, we are interested in investor protection in the UK c.1900 in terms of the creditor protection rights index and anti-director rights index of La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998). This leximetric approach has several drawbacks. First, such legal metrics place the same weight on every component, whereas some components may be more important than others. Second, such metrics are additive, but individual components could be complements or substitutes (Guinnane et al. Reference Guinnane, Harris and Lamoreaux2017). Third, what is important today may not have been important to investors living c.1900. We, nevertheless, follow the leximetric approach to facilitate comparisons across time and different countries.

Company legislation in the UK governed the incorporation and operation of UK companies and specified the rights of shareholders and creditors with respect to the company and its management. The Company Clauses Consolidation Act (1845) and the Company Clauses Act (1863) governed the activities of statutory companies (mainly railways and public utilities), which were incorporated from these dates onwards. These Acts simply standardised and codified the governance rules and practices that had been imposed upon companies which had been chartered by royal letters patent or authorised by special Acts of Parliament (Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2015, p. 6). The Companies Acts from 1862 onwards governed the incorporation and governance activities of all other companies, and by 1900 the vast majority of quoted companies were incorporated under this legislation. The Companies Act received its first major revision or overhaul in 1900 and was updated periodically thereafter. The Companies Acts also contained a blueprint set of articles of association (i.e. company constitution or bylaws), which could be adopted fully, partially or not at all by companies. This blueprint set of articles was referred to as Table A.

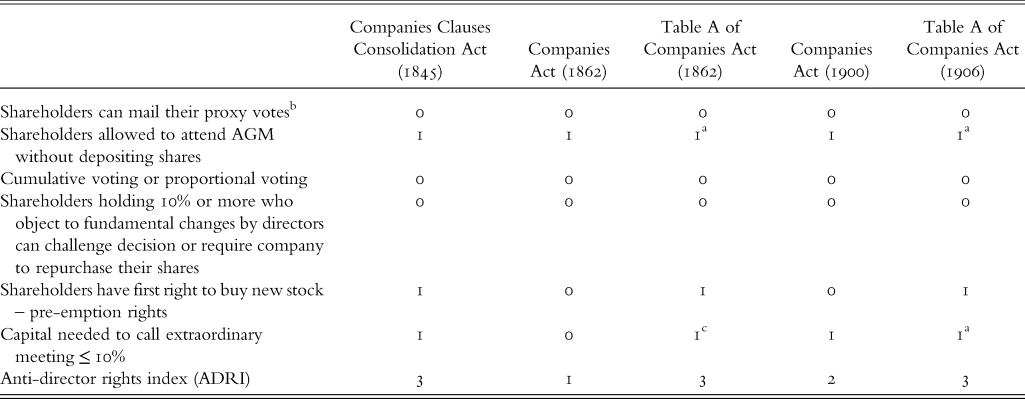

In terms of assessing how well the various pieces of company legislation and Table A protected shareholders, we construct the La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) anti-director rights index, which is the sum of six shareholder rights which they deem key for shareholder protection. First, we determine whether shareholders absent from shareholders’ meetings could vote (i.e. whether there was proxy voting by mail). Second, we check whether shares were required to be deposited before a meeting and whether shareholders were prevented from selling their shares for several days after a meeting. Third, we look for cumulative voting or proportional representation, whereby minority shareholders could elect board members. Fourth, we look for explicit minority-shareholder rights such as the right to challenge directors and assembly decisions in court and the option in the event of disagreement with a managerial or assembly decision to sell stock to the firm and thereby end one's participation. Fifth, we check whether shareholders had the first right to buy new stock in order to preserve their share of the company in the event of a decision to expand total equity (i.e. the anti-dilution provisions). Sixth, we coded as 1 when the percentage of capital needed to call an extraordinary meeting was less than or equal to 10 per cent. Table 1 shows the anti-director rights index for the three pieces of legislation as well as Table A,

Table 1. Anti-director rights index for the UK, c.1900

a Table A of the 1862 and 1906 Companies Acts have been coded to include variables in the ADRI which had passed into statute.

b The ADRI focuses on the ability of shareholder to mail their proxy vote, not on the existence of proxy voting. The Company Clauses Consolidation Act (1845) and Table A of the 1862 and 1906 Acts permit proxies but not via mail.

c Table A of 1862 Companies Act includes a suggested threshold on the proportion of shareholders needed to call an EGM, recommending a requirement of one-fifth of the shareholder body to do so. We have interpreted this clause as offering a similar right to shareholders as ≤10 per cent of capital because 20 per cent of shareholders could easily hold less than 10 per cent of the capital.

Sources: Companies Clauses Consolidation Act (1845); Companies Act (1862); Companies Act Table A (1862); Companies Act (1900); Companies Act Table A (1906).

It is a well-established fact that shareholder protection under the 1862 Act was minimal (Cheffins Reference Cheffins2008; Campbell and Turner Reference Campbell and Turner2011; Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2015). As can be seen from Table 1, the 1862 Companies Act provided little in the way of protection to shareholders, with an anti-director rights index of only 1. The 1900 Companies Act increased the anti-director rights index to 2, when a clause was inserted in the legislation to the effect that the capital required to call an extraordinary meeting was 10 per cent. The anti-director rights index did not increase again until the 1948 Companies Act, when the right to mail proxy votes was introduced. Table A of the 1862 and 1906 Companies Acts scores 3 out of 6. Companies, however, had complete discretion when it came to including these provisions in their articles of association, with the majority choosing to ignore the Table A blueprint (Campbell and Turner Reference Campbell and Turner2011, p. 574; Edwards and Webb Reference Edwards and Webb1985). How firms actually contracted with their shareholders will be discussed in Section vi.

As can be seen from Table 1, by way of contrast with the Companies Act, the anti-director rights score under the 1845 Company Clauses Consolidation Act (CCCA) was 3 out of a possible 6.Footnote 1 This is a level that company law requirements for non-statutory companies did not reach until 1980. In other words, the shareholders of railway companies received substantially more legal protection (in terms of law on the books) than shareholders in other companies.

La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) and Djankov et al. (Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007) suggest that credit markets are likely to be larger in countries with bankruptcy laws that include any of the following rights: secured creditors have the right to repossess their collateral in case of default (i.e. no automatic stay on assets for debtors); priority dictates that secured creditors (i.e. collateralised creditors) are paid first; approval of creditors is necessary for reorganising a firm or rescheduling the service of a firm's debts; and original managers do not stay during reorganisation (i.e. no debtor-in-possession reorganisation; trustees elected by the court or creditors run a company declared by a court to be bankrupt).

In terms of their creditor rights index, there are four rights deemed important by La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) and Djankov et al. (Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007): (1) secured creditors have the right to repossess their collateral in case of default (i.e. no automatic stay on assets for debtors); (2) priority dictates that secured creditors (i.e. collateralised creditors) are paid first; (3) approval of creditors is necessary for reorganising a firm or rescheduling the service of a firm's debts; and (4) original managers do not stay during reorganisation (i.e. no debtor-in-possession reorganisation; trustees elected by the court or creditors run a company declared by a court to be bankrupt). According to La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998, p. 1136) the law on the books in 1995 meant that creditors in the UK had all four of these rights. The legislative Acts which governed all companies during the years for which we estimate the value of the UK capital market gave creditors all four of these rights.Footnote 2 In other words, creditors had the four rights deemed important by La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) at the turn of the twentieth century and these rights had been in place for decades beforehand and remained in place during the following century (Coyle and Turner Reference Coyle and Turner2013).

The law on the books is a toothless tiger if it is not properly enforced. Although common-law courts c.1900 were generally reluctant to interfere in the internal workings of companies, they nevertheless acted when legal protections of creditors and shareholders were breached. Indeed, they went further in that they also vigorously acted against breaches of company's articles of association (Acheson, Campbell and Turner Reference Acheson, Campbell and Turner2016).

In summary, at the turn of the twentieth century, the law on the books in Britain provided very strong protection by modern standards for all creditors and for shareholders of companies incorporated under the 1845 CCCA. However, by modern standards, the shareholders of companies incorporated under the Companies Act had very weak protection afforded to them by company legislation.Footnote 3 According to the law and finance hypothesis, under these conditions, a thriving stock market with diffuse ownership should not have emerged in this period for such companies

IV

Estimating the size of the British capital market

There are two major hurdles that scholars face if they wish to estimate the market value of the domestic British capital market in 1900. The first hurdle is that there is no comprehensive source which contains the prices and capitalisation of all securities listed on the London and various provincial stock exchanges. To overcome this challenge is no mean feat given the size of the British capital market at this time. The second hurdle is that London was a global capital market at this time, meaning that scholars need to ascertain whether companies were domestic or foreign.

In order to estimate the market capitalisation of the UK share and bond market, we started by collecting data from the Investor's Monthly Manual (IMM). The IMM reported the prices, dividends, par values, and number of issued securities for a large number of equities and bonds which were traded on the London and provincial stock exchanges.Footnote 4 Although the IMM has been digitised by the Yale School of Management's International Centre for Finance, scholars need to clean this data carefully before using it (Grossman Reference Grossman2017). In particular, the security descriptors in the database confuse common shares, preference shares and corporate bonds. Therefore, we coded these different types of securities by hand using original hard copies of the IMM. We also checked the type of issue against the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence (SEOI).Footnote 5

Furthermore, the IMM was not comprehensive in that the securities of some companies were not reported. In terms of establishing the market capitalisation of the UK share and corporate bond market, this may not be a major issue as the omitted companies were all small. For example, Coyle and Turner (Reference Coyle and Turner2013, p. 814) in their study of the UK bond market find that the market value of the corporate bond market calculated from the IMM increases by only two per cent when the entire population of officially listed bonds is included even though there is a substantial increase in the number of bonds. Nevertheless, for 1900, we collected by hand data from the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence (SEOI), which gives the nominal capital of all companies which had securities listed on one of the UK's many provincial stock exchanges in 1900, to ascertain the extent to which the IMM underestimates the total value of the capital market.

Because UK companies were incorporated under different legislation, we had to differentiate between those incorporated under legislation which offered relatively little protection to shareholders and those which offered much more protection. In addition, because London was a global capital market during the era under investigation, we had to differentiate between companies incorporated in the UK and companies incorporated overseas, but which listed their securities on the UK market. Unfortunately, the IMM does not report such information. However, the information which helps us determine the legislation under which a company listed in the IMM was incorporated under is reported in the SEOI and the Stock Exchange Yearbook (SEY). We therefore used these sources to categorise companies into the following four classifications: (1) companies incorporated under the Companies Act; (2) companies which fell under the remit of the Companies Clauses Consolidation Act; (3) companies incorporated in the UK but not under the Companies Acts or Companies Clauses Consolidation Act; and (4) companies incorporated overseas or under UK colonial legislation. Over two thirds of the companies that fall into the third category were banks and insurance companies established before 1862. In terms of the fourth category, nearly 95 per cent of them were incorporated overseas.

Since we are interested in estimating the value of foreign securities listed on the UK capital market, we had to make adjustments to the prices of some foreign securities.Footnote 6 Foreign currencies have been converted to pounds sterling using exchange rates from Officer (Reference Officer2015) and Flandreau and Zumer (Reference Flandreau and Zumer2004).

Share and bond market capitalisation for the United Kingdom is estimated in 1895, 1900, 1913, and 1929, using the final IMM issue of each year and following the same methodology described above (i.e. checking by hand against the SEOI). 1895 was chosen as a sample year because it was just before the increase in the UK's anti-director rights index in 1900. 1929 is chosen because this is the final year in which the IMM was published. As well as providing estimates of the UK domestic market, we also provide estimates of the market value of colonial and foreign-listed securities in the UK. Our estimates are reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Total share and bond market capitalisation (£ million) quoted in Investor's Monthly Manual

Notes: Ordinary shares also includes deferred and founders’ shares. Panel B (Companies Act) includes those companies which are registered under the Companies Act. Panel C (Foreign/Colonial) includes those companies which are incorporated outside the UK or under UK colonial regulations. Panel D (CCCA) includes those companies which are registered under the Company Clauses Consolidation Act (1845). Panel E (Incorporated) includes those companies which are incorporated in the UK, but not under the Companies Act or Company Clauses Consolidation Act.

Sources: Market capitalisation is estimated using the capitalisation and market prices from Investor's Monthly Manual, 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929.

Table 3. Share and bond market capitalisation quoted in Investor's Monthly Manual (at market prices by incorporation legislation and as a % of GDP)

Notes: Ordinary shares also includes deferred and founders’ shares. Panel B excludes railways from our capitalisation estimates. The ‘Companies Act’ category includes those companies which are registered under the Companies Act. The ‘Foreign/Colonial’ category includes those companies which are incorporated outside the UK or under UK colonial regulations. The ‘CCCA’ category includes those companies which are registered under the Company Clauses Consolidation Act (1845). The ‘Incorporated’ category includes those companies which are incorporated in the UK, but not under the Companies Act or Company Clauses Consolidation Act.

Sources: Market capitalisation is estimated using the capitalisation and market prices from Investor's Monthly Manual, 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929. GDP figures used to normalise the stock market capitalisation are from Jones and Obstfeld (Reference Jones, Obstfeld, Calvo, Dornbusch and Obstfeld2001).

Because railways dominated the lists of the largest public companies (Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2012), we report our market value figures in Table 3 with and without the railways. An additional reason for doing this is that the railways of many comparator economies at this time were under state rather than private ownership.

British capital market value

Our estimates of nominal values in Table 2, which are based on the IMM, can be compared to extant estimates to ascertain their accuracy. Michie (Reference Michie1999, p. 88) uses the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence to estimate the nominal value of securities quoted on the Official List in 1913. His estimate, excluding foreign and domestic government and municipal debt, is £6.226 billion, which is very close to our estimate of £6.288 billion.Footnote 7 Hannah (Reference Hannah2015, Appendix 2) shows that the par value of shares and bonds officially listed in 1914, as published by the LSE Share and Loan Department, was £6.351 billion.

Tables 2 and 3 show the importance of separating out domestic and foreign/colonial companies: including such companies in our estimates would create a false impression of the market value of the UK share and bond market. Table 3 shows that the UK capital market is an important source of funds for foreign companies in 1895 and this is even more the case by 1913. However, the UK capital market is a relatively less important source of funds to foreign companies by 1929. Notably, Grossman (Reference Grossman2015) estimates that the share of overall share market capitalisation raised by non-UK firms in the UK approximately halved between 1913 and 1929. According to our calculations, the big decline during this period is actually in foreign bond issues and not so much in share market capitalisation for foreign firms. As can be seen from Panel B of Table 3, a large proportion of the share and bond capital issued by foreign companies in the UK was raised by railways.

Panel B of Table 3 also reveals that railways constituted a large proportion of the British capital market in this era. In terms of total share market capitalisation, domestic railways constituted 53, 49, 41 and 21 per cent of the total in 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929 respectively. The corresponding figures for the total market value of the domestic bond market are 77, 63, 61 and 45 per cent. It is important to bear this in mind when comparing the value of the UK capital market with those in countries where they progressively nationalised larger parts of the railway system (Bogart Reference Bogart2009).

How do our point estimates of market value compare to other estimates? One of the chief reasons for creating new estimates of total market capitalisation for the UK is that the estimate of Rajan and Zingales for 1913 has come under criticism. From Table 3, we see that our estimate of domestic UK share market size in 1913 (at 90 per cent of GDP) is lower than that of Rajan and Zingales for the same year (109 per cent of GDP). Moore (Reference Moore2010) estimates the size of the total UK share market as 123 per cent of GDP in 1900 and 133 per cent of GDP in 1913. These figures are smaller than our estimates based on the IMM of 150 per cent and 158 per cent in these years, suggesting that Moore's sources (Money Market Review and The Economist) were slightly less comprehensive than the IMM. Dimson et al. (Reference Dimson, Marsh and Staunton2002, p. 23) estimate that the market capitalisation of London quoted equities at the end of 1899 was $4.3 billion, or about 46 per cent of GDP. Grossman's (Reference Grossman2002, p. 128) estimates of the market capitalisation of common shares using the IMM, correspond to approximately 57 per cent of GDP in 1900 and 51 per cent in 1913. Our estimates for domestic ordinary shares are higher, at 114 per cent of GDP in 1900 and 120 per cent of GDP in 1913, but this is because we include more than just plain ordinary shares (e.g. deferred and preferred ordinary) and, unlike Grossman, we include shares issued in a foreign currency.

Tables 2 and 3 also permit us to see how market value changes over time and whether these changes correlate with changes in investor protection law. Although the UK's creditor protection law did not change between 1895 and 1929 for any company, no matter how it was incorporated, there is a substantial decrease in the market capitalisation of corporate bonds between 1913 and 1929. As can be seen from Table 3, this large relative decline in the market value of domestic corporate bonds is mainly concentrated in the railway sector. This is largely due to the disappearance of many railway bonds in the 1920s as a result of the government-orchestrated mergers of the large railway companies, following the Railway Act of 1921. Nevertheless, there is also a decline in the relative importance of non-railway bonds between 1913 and 1929. One possible explanation for this decline was the experience with wartime inflation, which decreased investors’ appetite for fixed-income securities (Coyle and Turner Reference Coyle and Turner2013). All this suggests that large changes in financial markets may be more a result of historical contingencies and politics rather than deep-rooted legal traditions and investor protection laws.

As noted above, the anti-director rights index for companies registered under the Companies Act was substantially less than that for companies registered under the CCCA. If the law and finance hypothesis is correct, it would predict that the share market for the latter would be much bigger than that for the former. As we can see from Tables 2 and 3, in 1895 the market capitalisation of total shares was 75 per cent greater for companies incorporated under the CCCA than the Companies Act. This, at first glance, appears to be consistent with the law and finance hypothesis. However, by 1913, the companies registered under the Companies Act had a larger market capitalisation than those incorporated under the CCCA. This gap had opened up even more by 1929, with the market value of companies registered under the Companies Act being more than three times that of those incorporated under the CCCA. What explains this change?

One possibility is that the market capitalisation figures are dependent on fluctuating share prices. However, when we look the nominal values in Table 2, the pattern is still the same even if the scale of the difference is diminished: companies incorporated under the CCCA have a larger nominal value in 1895 than companies registered under the Companies Act, but by 1913 this is reversed, and the gap widens further by 1929.

A second possibility is that the anti-director rights index for companies registered under the Companies Act increased from 1 to 2 in 1900, but for companies registered under the CCCA, there was no change in the anti-director rights index between 1895 and 1929. Notably, as can be seen from Table 3, there was a substantial relative decline in the total market value of companies incorporated under the CCCA between 1895 and 1929. This decline occurred despite no change in the relatively high protection afforded railway shareholders. On the other hand, the relative size of the share market for companies registered under the Companies Act grew between 1900 and 1913. At first glance, this could be attributable to an increase in the anti-director rights score, but the annual rate of growth in the size of the market was less than in the five years before 1900. In addition, the growth in market value between 1900 and 1913 largely reflects an increase in nominal value, i.e. more companies listing on the market (see Table 2).

In order to deal with the issue that the IMM is not comprehensive, we consulted the 1900 SEOI to see how many domestic companies were listed on UK stock markets and to get an estimate of their nominal capital. SEOI gives detailed information on capital issued by all companies listed in the UK, which we hand collect. Panel A of Table 4 shows the number of domestic companies quoted in the SEOI in 1900 as well as their nominal capital. Panel B of the same table shows the equivalent data for the IMM as well as the percentage of the IMM that is covered in the SEOI. Two things are worthy of note from Table 4.

Table 4. Number and nominal capital (£ million) of domestic company securities listed in Investor's Monthly Manual and Stock Exchange Official Intelligence, 1900

Notes: Ordinary shares also includes deferred and founders’ shares. This table considers companies to be domestic if they operated and were incorporated in the UK.

Sources: Figures in parentheses are the percentage of the SEOI that is in the IMM. Investor's Monthly Manual (1900, December edition) and Stock Exchange Official Intelligence (1900).

First, the proportion of companies in the SEOI that are also in the IMM is less than one quarter, meaning that most public companies are not listed in the IMM. The average nominal capital of companies in both sources is £2.24 million, whereas the average size of companies just in the SEOI is only £0.18 million. In other words, it is small companies that are not in the IMM. Their absence signals that there was a limited market for their securities either because they were so small or because there was a limited number of securities freely floating.

Second, about three-quarters of nominal capital in the SEOI belonged to companies quoted in the IMM. This would suggest that our estimates of the market value of shares and bonds based on the IMM underestimates the real value by about 25 per cent. Notably, 95 per cent plus of railway capital in the SEOI is quoted in the IMM. However, in terms of other companies (which are principally commercial and industrial entities), just over 50 per cent of nominal capital in the SEOI is also in the IMM. This is consistent with the growth in the number of small industrial and commercial companies listed on the stock market in this period.

In order to correct our estimates of market value based on the IMM, we make the assumption that the nominal value of securities in the SEOI but not in the IMM equals their market value. Without the benefit of additional information, we are unable to make any other correction to our estimates. We also assume that the proportion of nominal capital not quoted in the 1895, 1913 and 1929 versions of the IMM is the same as that in the 1900 version. Table 5 displays our baseline estimate from the IMM as well as our estimate of the entire domestic market value of bonds and equities. In 1900, our estimate of total share and corporate bond market value is 134.96 and 42.31 per cent of GDP.

Table 5. New estimates of total domestic share and corporate bond market value as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Market capitalisation and bond market value are estimated using the capitalisation and market prices from Investor's Monthly Manual, 1895, 1900, 1913 and 1929. GDP figures used to normalise the stock market capitalisation are from Jones and Obstfeld (Reference Jones, Obstfeld, Calvo, Dornbusch and Obstfeld2001). The estimate of the entire market adds the estimate of the nominal value of securities listed in the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence, but not the Investor's Monthly Manual, to the market value of those companies quoted in the Investor's Monthly Manual.

The British case raises questions about the law and finance hypothesis because in the home of the common law, there does not seem to be much correlation between investor protection and financial market development at the turn of the twentieth century. But the UK is only one, although admittedly very important, observation. Other countries c.1900 had less developed share and bond markets compared to the UK (Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales2003; Musacchio and Turner Reference Musacchio and Turner2013). If they had less investor protection than Britain, then this is consistent with the law and finance hypothesis. Thus, in the next section, we look at investor protection laws across the globe c.1900 to see if legal origin was correlated with investor protection scores and to see if Britain's low shareholder protection scores were replicated elsewhere.

V

Was the UK unique c.1900 in having weak shareholder and strong creditor protection laws? Was the UK's weak shareholder protection law and large share market simply an anomaly or did other nations c.1900 also have weak shareholder protection laws? One way of looking at these issues is to examine investor protection laws in other nations c.1900. We follow the methodology of La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) and Djankov et al. (Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007) in compiling indices of creditor and shareholder rights from the bankruptcy and company laws of a small cross-section of major economies across legal families for which data are available.

In Table 6, we follow the methodology used by La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) to identify the presence (or absence) of six shareholder rights they deem relevant for the growth of share markets for 11 countries for which detailed data are accessible. The number of rights present in the laws of each country was summed to create the La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) ‘anti-director rights index’ (bottom row of Table 6).

Table 6. Shareholder rights, c.1900

Notes: CCCA is the Company Clauses Consolidation Act and CA is the Companies Act. The USA score is for Delaware, which is the jurisdiction of choice for incorporation by publicly-traded companies (Cheffins, Bank and Wells Reference Cheffins, Bank and Wells2014).

Sources: UK scores are from Cheffins (Reference Cheffins2008, p. 36) and Acheson, Campbell and Turner (Reference Acheson, Campbell and Turner2019); USA from Cheffins, Bank and Wells (Reference Cheffins, Bank and Wells2014); Germany from Franks, Mayer and Wagner (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006); Japan from Franks, Mayer and Miyajima (Reference Franks, Mayer and Miyajima2007); China scores are for 1904 and from Williams (Reference Williams1905); Italy from Aganin and Volpin (Reference Aganin, Volpin and Morck2006); Brazil scores are for 1910 and from Musacchio (Reference Musacchio2009); Chile from Islas Rojas (Reference Islas Rojas2013); scores for France, Egypt and Sweden (c.1910) were constructed from information in Wellhoff (Reference Wellhoff1917). The La Porta et al. and Spamann anti-director rights indexes are from La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) and Spamann (Reference Spamann2010), respectively.

Most studies of investor protections in national company laws conclude that the initial boom in stock market development in the early part of the century occurred despite a lack of protection for small shareholders. Notably, all countries included in Table 6, apart from the United States, had no more than two of the shareholder protections La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997, Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) consider necessary for the development of a large stock market with a high proportion of widely held corporations. Thus, the level of protection afforded to minority shareholders in Britain c.1900 was on a par with other economies. As well as having weak shareholder protection, we also know from Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2003) that stock market activity around most of the globe was relatively high c.1913. This implies that the UK was not an anomaly – weak shareholder protection and large stock markets were commonplace c.1900.

In Table 7, indices of creditor rights are compiled following the procedure described in Section iii above for a variety of common and civil law countries for which data are available on the prevailing bankruptcy law at the time. The main reason for including only French civil law and common law countries is that it is precisely in these two groups of countries where the literature finds more marked differences in creditor protections (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998; Djankov et al. Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007).

Table 7. Creditor rights, c.1910 and 1995

Sources: All creditor rights for 1995 from La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998, table 4). Creditor rights for 1910 from the respective country sections of Borchardt and Kohler (Reference Borchardt and Kohler1906–14). Australia and Canada coded as following British bankruptcy law according to Brown (Reference Brown1900); United Kingdom, Companies (Consolidation) Act 1908; United States from Scrutton et al. (Reference Scrutton, Bowstead, Huberich and Baker1911); Hong Kong, Bankruptcy Ordinance no. 7 1891; Strait Settlements, Ordinance to Amend the Law of Bankruptcy no. 2 1888 (3 December 1888); France from Horn and Coermann (Reference Horn and Coermann1906); Belgium from Coermann and Hennebicq (Reference Coermann and Hennebicq1909) (based on the Commercial Code of 1872 as amended to 1910); Spain from Benito y Endara (Reference Benito Y Endara and Bewes1912); Argentina from Quesada (Reference Quesada and Bewes1912); Brazil, Lei 2024, 17 December 1908, in Brazil (1931–57).

In contrast to what researchers find with recent data, c.1900 the norm across countries was convergence on relatively strong creditor protections. Differences in creditor rights in the bankruptcy laws of the largest countries in Europe and the Americas were minimal. In Table 7, we see that, on average, both French civil law and common law countries had three of the four protections La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998) and Djankov et al. (Reference Djankov, La Porta, Lopez De Silanes and Shleifer2007) find explain significant differences in credit market development today. In terms of creditor protection in Britain in 1910, there was little in the way of difference between it and French civil law economies.

VI

As we saw above, Britain was not unique in having such poor statutory protection of shareholders. The question therefore arises as to how share markets developed without shareholder protection law. How do we resolve this puzzle? If investors participate in financial markets to a large extent when they know their returns are safe from the abuses or expropriation by insiders and directors, there had to be a system of shareholder protections in place that encouraged investors to buy shares during this period. In the case of Britain, there are several potential substitutes for statutory investor protection law.

The first possibility is that the common law legal system is based on legal precedent and common law judges acted to protect minority shareholders. However, common law judges did not believe that their role was to protect shareholders (Emden Reference Emden1884, pp. 77–80; Jefferys Reference Jefferys1977, p. 394). This philosophy was confirmed in the precedent set in the case in 1843 of Foss v. Harbottle, whereby it was ruled that when a company is allegedly wronged by its directors, shareholders do not have a right to sue, but the company does.Footnote 8 This ruling made it very difficult for an individual shareholder to sue over a grievance (Davies and Worthington Reference Davies, Worthington and Micheler2012, pp. 648–9).

The second possibility is that security market regulation was a substitute for statutory investor protection law. In the case of Britain c.1900, the only official stock exchange requirement pertaining to shareholder protection was that two-thirds of the nominal capital had to be allotted to the public and that articles prevent directors from using company funds to acquire its own shares (Melsheimer and Laurence Reference Melsheimer and Laurence1884; Melsheimer and Gardner Reference Melsheimer and Gardner1891, Reference Melsheimer and Gardner1905). There were no other requirements and the stock exchange regulations had an anti-director rights score of zero. However, informal stock exchange requirements may have acted as a substitute for published listing requirements. It was only in the early 1900s that stock exchange requirements increased in terms of information dissemination to shareholders and checks on director self-dealing (Gore-Brown Reference Gore-Browne1902; Thomas Reference Thomas1973, pp. 197–8). Burhop, Chambers and Cheffins (Reference Burhop, Chambers and Cheffins2014) suggest that these listing rules offered greater protection relative to IPOs which were on Special Settlement, i.e. unlisted.

The third possibility is that dividends can act as a substitute for shareholder protection because it keeps managers on a short leash in that they must come to capital markets to raise finance rather than use retained earnings (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny2000b). It also reduces the free cash flow that managers have discretion over. In the case of the UK, companies paid high dividends and were rewarded by capital markets for doing so (Campbell and Turner Reference Campbell and Turner2011). However, there is little evidence to suggest that dividends were a substitute for shareholder protection in other early capital markets.

A final possibility is that shareholders and company directors could contract privately to solve any incentive problems, with the result that statutory shareholder protection law was not needed. In the UK, for example, companies could offer shareholders high levels of protection through their articles of association. The common law was famous for enforcing contracts such as articles of association. Consequently, the courts rigorously enforced breaches of articles. Indeed, the only occasion when a shareholder could bring a derivative suit against a company was when articles had been breached. The question therefore is: did companies freely offer their shareholders much in the way of protection via their articles of association?

Recent scholarship by Guinnane et al. (Reference Grossman2017), however, suggests that the contractual freedom which British companies had in this era was abused because incorporators wrote articles which empowered directors at the expense of shareholders. However, most of their sample consists of private companies that were not listed on the stock market.

In contrast, Acheson, Campbell and Turner (Reference Acheson, Campbell and Turner2019) examine c.500 articles of association of companies which had shares listed on a UK stock market between 1862 and 1900. They find that the shareholder protection offered by these companies was high compared to modern-day standards. In addition, firms with more diffuse ownership offered higher protection to their shareholders. Notably, Hilt (Reference Hilt2008) and Musacchio (Reference Musacchio2008, Reference Musacchio2009) both point to the important role played by corporate bylaws in facilitating the separation of ownership from control in early share markets. A comparative study of company constitutions and their enforcement should prove to be a fruitful avenue for future research, which may resolve the puzzle as to why stock markets thrived when shareholder protection was so weak.

VII

The evidence presented in this article reveals three things. First, in the home of the common law, there is little correlation between investor protection scores and the development of the UK capital market around the turn of the twentieth century. This in and of itself is not evidence against the legal origins hypothesis, but it does raise a question as to the importance of investor protection legislation for the development of financial markets.

Second, whereas the law and finance literature argues that the differences observed in credit market development today are largely a product of clear differences in creditor protections contained in national laws (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1998; Djankov et al. Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007), at the turn of the twentieth century, we find convergence in the extent of creditor protections included in the bankruptcy laws of common and French civil law countries.

Third, the evidence on shareholder rights at the turn of the twentieth century also shows that in most countries for which we have data, investor protections included in national company laws were weak. That is, there was convergence on weak shareholder rights in national laws across countries. In other words, Britain was not unique in having weak shareholder protection and it was also not unique in having both weak shareholder protection and a thriving share market.

The findings of this article do not imply that legal origin cannot be a significant explanatory variable of the differences observed in financial development today. Instead, they suggest a need for more research into how the shocks of the twentieth century such as the inflationary shock after World War I and the Great Depression triggered a political process that led to state intervention and regulation, which ended up making legal origin matter more. Perhaps the divergence in financial development and investor protections in countries of different legal origins today is related to the fact that in French civil law countries, the law-making process is highly centralised, rendering it more easily captured by interest groups. In contrast, in common law countries, judges have an easier time adapting the statutes and guaranteeing that the rules that work best in practice end up prevailing (Glaeser and Shleifer Reference Glaeser and Shleifer2002; Beck et al. Reference Beck, Demirguç-Kunt and Levine2003a). Even if this is the case, the starting point for this adaptation process was not hundreds of years ago (when legal systems were introduced), but only a few decades ago, and, in any case, the effects of legal origin manifested themselves in the institutions that sustain financial development only after the political economy of these countries digested the shocks of the early part of the twentieth century.