Introduction

If we leave aside the fragments (mainly religious) and single words, phrases or verses, which appeared in the Armenian manuscripts from the fourteenth century onward, we know of only a relatively small number of manuscripts containing what may be called “Armeno-Persian,” i.e. Persian material written in Armenian characters.Footnote 1 Two analogous Persian Gospel codices written in Armenian script (Ms. 8492 and Ms. 3044Footnote 2) are held in the depository of Armenian manuscripts of the Matenadaran, Mesrop Mashtots Research Institute of Ancient Manuscripts of Yerevan. Ms. 3044 (compiled in 1780 in Ganja, center of Ganja KhanateFootnote 3) is a copy of Ms. 8492 (written in 1717–21 in Shamakhi, the center of the historical Shirvan region in TranscaucasiaFootnote 4) which is confirmed by the colophon of the manuscript written by an Armenian member of the clergy, Father Mikayel:

Ms. 3044, f141v որ ի ՌՄԻԸ (1228) ես տեր Միքայիլս գրեցի օրինակի լուսայհոքի հաքիմ Յակոբին որ գրեալ էր ի քաղաք Շօշ ի վաղուց ժամանակի յառաջ ժամօվ. սա մեք գրեցաք սբ ավետարանս ի քաղաքն Գանճայ ի հայրապետություն հայոց տեառն Սիմիօնի եւ ի տունս աղունք տեառն Իսրայիլի, որոյ յիշատակը օրհն[ու] եղիցի:

Or i ṘMIƏ (1228) es ter Mik῾ayils grec῾i ôrinaki lowsayhok῾i hak῾im Yakobin or greal êr i k῾ałak῾ Šôš i vałowc῾ žamanaki yar̄aǰ žamôv. sa mek῾ grec῾ak῾ sb avetarans i k῾ałak῾n Gančay i hayrapetowt῾yown hayoc῾ tear̄n Simiôni ew i towns ałownk῾ tear̄n Israyili, oroy yišatakə ôrhn[ow] ełic῾i. Footnote 5

(Thus I, Father Mikayel, wrote [the Gospel] in 1228 [according to the Old Armenian Calendar, 1779–80], after the original by Hakim Yaghub [the author of Ms. 8492] may God bless his soul, which was written in the city of Shosh [Isfahan; Hakim Yaghub notes in his colophon that he is from Isfahan, but he translated the Gospels in Shamakhi] at an earlier date. We wrote this Holy Gospel in the city of Ganja in the Armenian patriarchate of Father Simion and in the Aƚuwnkʻ Catholicate of Father Israel, may God bless his soul.Footnote 6)

The other colophon of Father Mikayel confirming the same fact is written in the Introduction of the manuscript (about the Introduction see below):

Ms. 3044, f10r Վերջին գրող սբ. Ավետարանիս տեր Միքայիլ աստապատցի որ եմ Գանճայ բնակեալ, տեսի ջան լուսայհոքի Օվանիսին եւ Յակոբին, որ նորանք եւս էին գրեալ եւ ես ի նոցուն օրինակի գրեսցի: Հո՛գի Սուրբ, օգնեա՛յ բազմայմեղ գրչիս, ՌՄԻԸ. յնվրի ԻԷ.

Verǰin groł sb. Avetaranis ter Mik῾ayil astapatc῾i or em Gančay bnakeal, tesi ǰan lowsayhok῾i Ôvanisin ew Yakobin, or norank῾ ews êin greal ew es i noc῾own ôrinaki gresc῾i: Ho՛gi Sowrb, ôgnea՛y bazmaymeł grč῾is, ṘMIƏ. ynvri IÊ.

(I [as] the last scribe of the Holy Gospel, Ter Mikayel from Astapat living in Ganja saw the efforts of Ovanes and Yakob, may God bless their souls, that they also wrote [this Gospel] and I wrote [it] based on their sample. May the Holy Spirit help [me], the sinful scribe. 1228 (equal to 1780), the 27th January.)

Two codices—Ms. 8492, Ms. 3044—have the following structure: the introduction, four canonical Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and the content of the passages. The introductions are the transcript versions of the Unified Gospel’s introduction from the thirteenth century written in Persian.Footnote 7 The colophon of the Unified Gospel is also preserved in these introductions rendered in Armenian script:

Ms. 3044, f10v … թամամ թայիֆայ իսայիեան ինջիլ մազիմ դարանդ քի բը զըբան ինշան բար ինշան խունդայ միշօվատ ամայ սապապ ըշղալ մաշիթ ինշան բըզըբան փարսի ջարիտանդ [ջարի անդ] ազ զըբան խօտ քի ասլի աստ ղաբըլ ինշան միշնօվանտ նայմիադանտ [նայմիդանանտ] բայուն մըղդար սաֆ.

… t῾amam t῾ayifay isayiean inǰil mazim darand k῾i bə zəban inšan bar inšan xownday mišôvat amay sapap əšłal mašit῾ inšan bəzəban p῾arsi ǰaritand [ǰari and] az zəban xôt k῾i asli ast łabəl inšan mišnôvant naymiadant [naymidanant] bayown məłdar saf.

(The whole community of Christians has the holy Gospels which are read for them in their languages but because of the daily employment they know Persian better than their own original language [which] they often hear but do not understand currently.)

This data underlines the fact that since the thirteenth century the Christian community of Iran, comprising mainly Nestorians and Armenians,Footnote 8 has been Persophone: they knew Persian better than their own languages. The situation was the same after five centuries when Hakim Yaghub decided to translate the Gospels into Persian and use the Armenian script (with consideration to Armenians), which he emphasized in his colophon:

Ms. 3044, f10r ամայ չուն ին բանդայ աջիզթարին Եաղուպ բըն Իսայղուլի ինճիլ թարջումայ քարդայի Իեահէայ բըն Էվազ րայ դիտամ բըսիար դար դըլ ին բանդայ նաղշ բաստ բար բանդայի գունայքար լազում ամատ քի ին բանդայ նիզ թարջումայ քարդամ քունամ ինջիլ մազիմ րայ ազ ավալ Մաթ զայիտան Եսոյ ազ նաթջայ դաւութ վի ֆասլ ֆասլ վէ այիեայ թամաման ջահար ինջիլան նիզ բըդին մազբուր նայ բըուն խիալ քի Իեահեայ նիքու նայ քարտ աստ քի ջահար դախըլ համ քարդաս խուպ նիստ. նայ բըդի խիալ իլայ քի հար քուդամին բար ջայի խօտ պաշատ ջըհաթ ուն ան քի մի խունանտ դիկար ասանթար պաշատ բար ին սապապ չնին քարտամ նայ բար հասուտի.

amay č῾own in banday aǰizt῾arin Eałowp bən Isayłowli inčil t῾arǰowmay k῾ardayi Ieahêay bən Êvaz ray ditam bəsiar dar dəl in banday nałš bast bar bandayi gownayk῾ar lazowm amat k῾i in banday niz t῾arǰowmay k῾ardam k῾ownam inǰil mazim ray az aval Mat῾ zayitan Esoy az nat῾ǰay dawowt῾ vi fasl fasl vê ayieay t῾amaman ǰahar inǰilan niz bədin mazbowr nay bəown xial k῾i Ieaheay nik῾ow nay k῾art ast k῾i ǰahar daxəl ham k῾ardas xowp nist. nay bədi xial ilay k῾i har k῾owdamin bar ǰayi xôt pašat ǰəhat῾ own an k῾i mi xownant dikar asant῾ar pašat bar in sapap č῾nin k῾artam nay bar hasowti.

(But as the poor servant Yaghub Ibn Isaghuli saw the Gospel which was translated by Yahya Ibn Eyvaz and left traces in the heart of the servant. [It] became necessary to the humble servant to translate the Holy Gospel, to compose the Holy Gospel from the beginning of Matthew Gospel, the birth of Jesus son of David, chapters by chapters and all parts of the four Gospels with this order. I composed this not having in mind that Yahya did not do well mixing it and it is not good [to mix Gospel chapters]. Not having in mind but [I hope] each one will be at its own place and it will be easier everyone who reads it, for which I did it and not for envy.)

The scribe Hakim Yaghub also outlines the other reason for translating the Gospels in Persian:

Ms. 8492, f236r: … դանըստայ պաշիտ է բըրայդէրան ազիզ քի սապապ ինճիլ մազիմ նվիշթան բըզըպան ֆարսի ինպուտ քի աքսար մալիման մսըլմանան ան դըղաթ միգըրըֆտանտ բայ ջամիյիեաթ իսայիան դար բալայի աքսար չիզայ քի ունչնան իեայ ինչնան աստ.

… danəstay pašit ê bəraydêran aziz k῾i sapap inčil mazim nvišt῾an bəzəpan farsi inpowt k῾i ak῾sar maliman msəlmanan an dəłat῾ migərəftant bay ǰamiyieat῾ isayian dar balayi ak῾sar č῾izay k῾i ownč῾nan ieay inč῾nan ast.

(Be aware, dear brothers, that the reason for writing the Holy Gospel in Persian was that most of the Muslim intellectuals argued on a wide range of issues with the Christian community: which is not so or which is so.)

The data of the mentioned colophon lead us to map out the tradition of religious debate and Islamic propaganda among Armenians in the eighteenth century. The Armenians had to argue the religious issues with Muslim clergy in Persian, strengthen Christian knowledge and for this purpose these codices were visibly effective means.Footnote 9

A tangible social factor impacting on the diffusion of Persophony among Armenians living in eastern Transcaucasia, i.e. the need and requirement to use Persian which was in a hierarchical bilingual partnership with vernacular Armenian and was spoken by the rulers and by the majority of people of that area.Footnote 10 Herein lies the question: was the choice to render Persian into Armenian characters motivated by a pragmatic factor or was there anything distinct or symbolic for the Armenian script itself?

Armenian letters and literature, and in particular the alphabet, were imbued with sacral meaning and symbolized to their users the association with Christianity during the domination of religious ideology in mediaeval period.Footnote 11 Indeed, for Armenians, the Armenian alphabet has sacrosanct qualities as a marker of cultural identity.

Ordinary Armenians knew Persian only for routine. They understood it very well, spoke it, but could not read and write it because the Arabic script was not included in the syllabus in primary schools for Armenian children,Footnote 12 and in the educational process learning Persian with Armenian characters obviously had pragmatic consideration.Footnote 13 In this regard, we could mention the manuscript of the Persian–Ottoman Turkish bilingual dictionary Tuhfe-ye Shahidi (Ms. 10586), written in Tabriz in Armenian script by Hovhannes Abegha,Footnote 14 dated 1721, which is held in the depository of the Matenadaran.Footnote 15 Taking into consideration the educational role of this type of dictionary in the mediaeval period, the Armeno-Persian–Armeno-Turkish version of abovementioned dictionary could be used for teaching Armenians Persian and Turkish even in primary schools. Through this type of dictionaryFootnote 16 Armenians could also learn Persian poetry by quoted verses from the Persian literature. Hence, the Armenian Christian elite clergy probably knew the Arabic script: they had mastered the writing and speaking of Persian. One of the arguments is the Armeno-Persian introduction of Ms. 8492 and Ms. 3044, transcribed from the Arabic script introduction of the Unified Gospel in Persian by the scribe Hakim Yaghub.

The usage and knowledge of the Armenian alphabet also distanced and dissociated Armenians from the members of the broader ethnic community of northeastern Transcaucasia, which was composed of Persians and the other Iranian tribes, Turk[ic] people, Lezgins and other Lezgic tribes.

The audience of the Armenian script Gospels was the ordinary Armenian population and the manuscripts were used by the Armenian clerics for reading the Gospel’s texts in the ceremonies for the Persophone Armenians who used to pray in Persian. As Krstić states, “in a society with limited literacy reading aloud or reciting was an important aspect to the communication and articulation of social identity.”Footnote 17

The abovementioned manuscripts are evidence that for the Armenians of Shirvan in the eighteenth century Persian was the interethnic language of communication which they knew better than the vernacular Armenian. The following analysis of the transcription of Persian into Armenian script illustrates that the manuscripts were written based on the principles of traditional Armenian orthographyFootnote 18 and phonetic Persian. The rules of Armenian orthography were utilized by Armenian scribes for writing Persian.Footnote 19 This allows us to study the Armenian orthography of the eighteenth century as well as the variety of Persian spoken in eastern Transcaucasia.Footnote 20

The Transcription of Persian Vowels

Persian vowels that are not reflected in Arabic script, namely short a, e, and u, are transcribed in the aforementioned manuscripts by Armenian letters ա [a], է/ե [ê/e],Footnote 21օ/ո [ô/օ], respectively. That is, mainly, the short and long vowels a and ā are transcribed the same way, because they were pronounced similarly, which is a characteristic of colloquial speech, and quite possibly how Persian-speaking Armenians may have pronounced them. Besides this, the Armenian alphabet does not distinguish long and short vowels. Particularly, in Middle Armenian texts the Persian short a [ا] (in the foreign words) was a reduced vowel in contrast to long ā [آ] and was mainly rendered by the Armenian letter ǝ [ը]. Consequently, this short vowel (sometimes also the vowel e) is often dropped in the middle of words or pronounced -ı- and written with the letter ը [ǝ], as a continuation of the Middle Armenian orthographic rule.Footnote 22 Sometimes the pronunciation of short vowels a/e fluctuates. The short vowels are also often dropped in contemporary colloquial Persian.

Short a. Footnote 23 It is rendered by the letter ը [ǝ]. Besides the causes noted above, it appears in spoken Persian as an ı, prior to a stressed syllable with a long ā, when ı is an allophone of Persian short a:

Ms. ǝntʻaxtam [ընթախտամ]—NP (New Persian) andākhtam “I throw”;Footnote 24

Ms. minǝhant [մինըհանտ]—NP minahānd, CP (Colloquial Persian) minıhānd “they put”;

Ms. nǝhat [նըհատ]—NP na(e)hād, CP nıhād “I put”;

Ms. zəb/pan [զըբ/պան]—NP zabān “language,” etc.

In the remainder of cases, it is transcribed as ա [a]:

Ms. aval [ավալ]—NP avval “first”;

Ms. andišay [անդիշայ]—NP andīshe “mind”;

Ms. az [ազ]—NP az “from”;

Ms. ƚazap [ղազապ]—NP ghaḍab “anger,” etc.

Persian lax, short e. Footnote 25 In initial position e- is replaced by ի- [i-] in words of Arabic origin which are caused by regressive assimilations to the high vowel of the second syllable;Footnote 26 cf.

Ms. ištʻiaƚ [իշթիաղ]—NP eshtīāq “alacrity”;

Ms. inčil/inǰil [ինճիլ/ինջիլ]—NP enjīl “Bible,” etc.

Transcribed as ը [ə] in word-initial position in words of Arabic origin, if the next syllable’s long ā vowel influenced the previous syllable’s -e- > ǝ- [-ը-]:Footnote 27

Ms. ǝntʻǝhan [ընթըհան]—NP emtehān “examen”;

Ms. ǝntʻǝhay [ընթըհայ]—NP entehā “finish”;

Ms. ǝltʻǝmas [ըլթըմաս]—NP elṭemās “adjuration,” etc.

In the verbal prefixes and first syllables of the verbal forms, the vowel -e- is also written as -ǝ- [-ը-],Footnote 28 e.g.:

Ms. bǝdahat [բըդահատ]—NP bedahad “may he give”;

Ms. nǝvištant [նըվիշտանտ]—NP neveshtand “they wrote”;

Ms. bǝngǝrit [բընգըրիտ]—NP benega/ārīd “let you watch”;

Ms. bǝxownit [բըխունիտ]—NP bekhwānīd “let you read,” etc.

Transcribed ա [a] at the end of the Persian past participle -e reflects its pronunciation in Early New Persian (ENP). In all probability, the ending of the past participle continued to be pronounced a. While this disappeared in literary Persian in approximately the sixteenth century, it remains in some contemporary Persian dialects and Iranian languages, as well as in the manuscripts under discussion:

Ms. pʻaray kʻanday [փարայ քանդայ]—NP parākande “(having been) dispelled”;

Ms. dar manday [դար մանդայ]—NP dar mānde “(having been) overpowered,” etc.

The suffix -esh, used to create substantives (< ENP -ish, Middle Persian /MP/ -ish /-ishn < Old Persian /OP/ *-shna), is transcribed -իշ [-iš] (e- > i- perhaps (?) before fricative -sh), e.g.:

Ms. baxšiš [բախշիշ]—NP bakhshesh “donation, forgiveness”;

Ms. asayiš [ասայիշ]—NP āsāyesh “convenience”;

Ms. raviš [ռավիշ]—NP ravesh “approach,” etc.

The -esh- > -իշ- [-iš-] transition is evident in the following words:

Ms. fǝrištʻay [ֆըրիշթայ]—NP fereshte “angel”;

Ms. nǝvištʻay [նըվիշթայ]—NP neveshte “written,” etc.

In the manuscripts, we find the West Middle Iranian form of this suffix, -isht (also in the form -esht) which isn’t preserved in the contemporary NP:

Ms. xayhi/ešt [խայհի/եշտ]—NP khwāhesh “request.”Footnote 29

The fluctuation of short -e and short -a in literary and everyday colloquial Persian is common and is also found in the manuscripts, e.g.:

Ms. baradêr [բարադէր]—NP barādar “brother”;

Ms. madêr [մադէր]—NP mādar “mother”, etc.

In the initial position [y-] + short vowel [-e] is rendered by -ե [-e-] for the sound [ye], as in modern and dialectal Armenian which was primarily regulated in the eighteenth century (see footnote 25):

Ms. ekʻ [եք]—NP yek “one”;

Ms. eganay [եգանայ]—NP yegāne “only”;

Ms. eganegi [եգանեգի]—NP yegānegī “oneness,” etc.

In the eighteenth century Armenian the diphthong -ia- [-իա-] was written -եա- [-ea-] and this rule was also suitable for the manuscripts; i.e. in Persian the most common VV combination involves the sequence [ī] + [a] > -īa- (یَ ), which in these texts is visible via the phonetic group -իեա- [-iea-], and this phenomenon also refers to the rules in Armenian according to which before a word-ending consonant cluster and in stressed syllables before -ա- [-a-] vowel is only written -ե- [-e-]:Footnote 30

Ms. gowieant [գուիեանտ]—NP gūyand “they will say”;

Ms. darieayi [դարիեայի]—NP daryāyī “a sea”;

Ms. ǰamieatʻ [ջամիեաթ]—NP jamʻīyyat “population”;

Ms. xowdayieatʻ [խուդայիեաթ]—NP khudāyat “your God,” etc.

As stated above (see footnote 25), the equal use of the letters ե [e] and է [ê] is the result of the elimination of the differences between these letters in Middle Armenian. For the scribe, these letters had the same phonemic values, which is reflected in these examples:

Ms. dê/el [դէլ / դել]—NP del “heart”;

Ms. vê/e [վէ/վե]—NP va “and”;

Ms. mownê/ent [մունէնտ/մունենտ]—NP mānand “similar, alike,” etc.Footnote 31

See also:

Ms. šêšowm [շէշում]—NP sheshum “sixth”;

Ms. vêzayif [վէզայիֆ]—NP vaẓāyef “duties”;

Ms. bêhêšt [բէհէշտ]—NP behesht “paradise”;

Ms. êliše [էլիշե]—Personal name Yełiše;,

Ms. ełiay [եղիայ]—Name of Prophet Elias, arm. Yełya;

Ms. ieałub [Իեաղուբ ]—Personal name Jacob;

Ms. abêd [աբէդ]—NP ābd “eternal”;

Ms. ǰavêd [ջավէդ]—NP javīd “eternal,” etc.

Short u. According to the rules of eighteenth century Armenian orthography all foreign words containing the phoneme u were written with the letter o [ô] in any position.Footnote 32 This rule is preserved in the Armeno-Persian manuscripts in words of Iranian origin. See:

Ms. ôftat [օֆտատ]—NP uftād “he fell”;

Ms. gôft [գօֆտ]—NP guft “he said”;

Ms. sôxan [սօխան]—NP sukhan “speech, word”;

Ms. ṙôx [ռօխ]—NP rukh “face”;

Ms. sbôkʻ [սբօք]—NP sabuk “light”;

Ms. pʻôr [փօր]—NP pur “ful”;

Ms. kʻôštant [քօշտանտ]—NP kushtand “they killed.”

See also:

Ms. fôtʻ [ֆօթ]—NP fo[w]t “death.”

It is known that in Persian one of the less common word-end short vowels is -u and usually occurs before the word-end consonant except in some words: tu “you”; du “two”; pulu “cooked rice”; buru “go.” In the examined manuscripts the mentioned words tu “you,” du “two” are written with the final -ow (see below), and -u only appears in the final position as a result of dropping word-ending -h and the glottal stop eyn. In these cases, the scribe used the traditional Armenian orthographic rule of the letter ո [o], i.e. in Armenian the letter ո [o] was the word-end letter for the sound o and was closed with the glide յ [y]. See:

Ms. šǝroy [շըրոյ]—NP shurūʻ “beginning”;

Ms. gǝroy [գըրոյ]—NP gurūh “group,” etc.

In the middle position of words, -u- is rendered by -ու- [ow] in the following words, reflecting ENP pronunciation, which, apparently, was preserved in the spoken Persian of eighteenth century Shirvan. See:

Ms. xowda [խուդա]—NP khudā, ENP khudā “God”;

Ms. xowdayvant [խուդայվանտ]—NP khudāvand, ENP khudāvand “God”;

Ms. kʻownand [քունանդ/տ]—NP kunand, ENP kunand “they will do”;

Ms. kʻowǰa [քուջա]—NP kujā, ENP kūjā “where”;

Ms. dow [դու]—NP du, ENP dū “two”;

Ms. tow [թու]—NP tū “you,” etc.

In words of Arabic origin, u reflects its unique Classical Arabic pronunciation and is transcribed ու [ow], which shows that a “Persianization” of its pronunciation had not occurred in spoken Persian. See:

Ms. mowqadamay [մուղադամայ]—NP muqaddame “preface”;

Ms. mowxtaysar / muxtasar [մուխտայսար/մուխտասար]—NP mukhtaṣar “brief”;

Ms. sowriani [սուրիանի]—NP surīānī “Assyrian”;

Ms. mowxalǝfatʻ [մուխալըֆաթ]—NP mukhālefat “opposition”;

Ms. mowdatʻ [մուդաթ]—NP muddat “time, while.”

See also:

Ms. lôqaz [լօղազ]—NP lughat “word, speech.”

The shifting of the short u, e, a to ը [ǝ] before liquid r and l. These short vowel phonemes are transcribed ը [ə] before the liquid r, which is explained by Persian’s phonetic rules. In general, ENP does not allow for word-initial consonant clusters, which is why a vowel is added at the beginning or is placed in between the consonants (anaptyxis). Contemporary Persian has also inherited this practice. However, colloquial Persian had not established distinct pronunciations for these added vowels and they were pronounced [ı]. See:

Ms. sǝrowde [սըրուդե]—NP surūde “song”;

Ms. čʻǝra [չըրա]—NP çerā “why”;

Ms. bǝray [բըրայ]—NP barāy “for”;

Ms. fǝrow [ֆըրու]—NP furū “down”;

Ms. gǝrt [գըրտ]—NP gerd “round, circular”;

Ms. afǝrit [աֆըրիտ]—NP āfarīd “he created,” etc.Footnote 33

Also transcribed ը [ə] prior to the liquid l in words of Arabic origin, e.g.:

Ms. hasǝl [հասըլ]—NP hāṣel “outcome”;

Ms. ǰalǝl [ջալըլ]—NP jalīl “magnicifent”;

Ms. vǝlayieatʻ [վըլայիեաթ]—NP velāyyat “province,” etc.

Long labialized ā. This phoneme is sometimes rendered by o- [ô-] at the beginning of a word, sometimes as ու- [ow-] at the beginning and in the middle of a word, but mainly, in all positions, as -ա- [-a-]․ The -ā- > -ū- shift before a sonant is a characteristic of colloquial Persian (farsi-ye ʻāmmiyāne) based on the Tehrani dialect. On the rendering of ā in the manuscripts see:

Mss. ôvarday [օվարդայ]Footnote 34—NP āvarde “brought”;

Ms. ômat [օմատ]—NP āmad “came”;

Mss ônan [օնան]—NP ānān “they”;

Ms. mownê/ent [մունէ/ենտ]—NP mānand “similar”;

Ms. kʻǝdowm [քըդում]—NP kudām “which”;

Ms. own [ուն]—NP ān “that”;

Ms. atʻaš [աթաշ]—NP ātash “fire”;

Ms. ap [ապ]—NP āb “water,” etc.

Long ū and ī. These phonemes are written as they would be pronounced in contemporary Persian, e.g.:

Ms. iman [իման]—NP īmān “sure, sacred”;

Ms. nifrin [նիֆրին]—NP nefrīn “curse”;

Ms. zǝmin [զըմին]—NP zamīn “ground, land”;

Mss tʻiztʻar [թիզթար]—NP tīztar “sharper”;

Ms. rowz [րուզ]—NP rūz “day”, but Mss rôze—NP rūze “fast”;

Ms. pʻiš [փիշ]—NP pīsh “nearby”;

Ms. mi [մի-]—the verbal prefix NP mī-;

Ms. gownaygown [գունայգուն]—NP gūnāgūn “assorted, varied,” etc.

The Semivowel Y

In the manuscripts discussed above, the voiced dorso-palatal glide յ [y] is written according to the rules of traditional Armenian orthography, inserted at the final position of words after the vowels ա [a] and -ո [-օ], and in the remaining cases according to Persian phonetic rules.

Words ending in ա [a] and -ո [օ] (see below) are “closed” with a syllable-ending յ [y], e.g.:

Ms. Esoy [Եսոյ]—NP ʻIsa “Jesus”;Footnote 35

Ms. downiay [դունիայ]—NP dunyā “world”;

Ms. aškʻaray [աշքարայ]—NP āshkārā “clearly”;

Ms. pʻarday [փարդայ]—NP parde “curtain”;

Ms. hamay [համայ]—NP hame “all”Footnote 36 etc.

Persian’s past participle ending -e was pronounced -a. In the text of the manuscripts it is rendered by -ա- [-a-] and closed with a -յ- [-y-]. See:

Ms. nǝgay daštay [նըգայ դաշտայ]—NP negāh dāshte “kept”;

Ms. šnitay [շնիտայ]—NP shenīde “heard”;

Ms. larzanday [լարզանդայ]—NP larzande “rocking,” etc.

The Persian negative prefix na- is also closed with a -յ [-y] before the verb roots beginning with consonants and vowels. In contemporary Persian, the y semivowel is only added prior to verb roots beginning with vowels to avoid hiatus. In the manuscripts, the negative prefix is written separately, which forces it to follow the rules of Armenian orthography, explaining why it ends in յ [y]. See:

Ms. nay gowzaštʻ [նայ գուզաշթ]—NP nagudhāsht “did not allow”;

Ms. nay tʻvanat [նայ թվանատ]—NP natavanad “cannot”;

Ms. nay šôvant [նայ շօվանտ]—NP nashavand “they do not,” etc.

The յ [y] semivowel is added prior to the Persian plural suffix -ān, as well as following the vowels –ā,Footnote 37-ī, and -ū. In a word ending in -e (written -ա [a] in the manuscripts), we have the plural ending -gān. This can be explained by diachronic analysis. The -g phoneme at the end of the historical root reappears, restoring the Middle Persian noun forming -ag suffix > Modern Persian -e. This practice is preserved throughout the text of the manuscripts. In almost every case, the Armenian syllable closing յ [y] semivowel is also written. See:

Ms. fǝrǝštʻaygan [ֆըրըշթայգան]—NP fereshtegān “angels”;

Ms. sǝtʻaraygan [սըթարայգան]—NP setāregān “stars”;

Ms. bêčʻaygan [բէչայգան]—NP baççegān “children.”

But:

Ms. biganǝgan [բիգանըգան]—NP bigānegān “strangers”;

Ms. yeganegan [եգանեգան]—NP yegānegān “individuals,” etc.

The same can be observed in plural nouns containing the present participle suffix Ms. -անդայ (MP -andag > NP -andeh), prior to the ending -gan. See:

Ms. daṙandaygan [դառանդայգան]—NP dārandegān “those having”;,

Ms. dahandaygan [դահանդայգան]—NP dahandegān “those giving”;

Ms. kʻownandaygan [քունանդայգան]—NP kunandegān “those doing,” etc.

The Diphthong ow

The diphthong ow is written in the ENP texts with the short “a” sign (fatha) and was probably pronounced as in the words, naw “new,” jaw “barley,” and rawzi “day”Footnote 38 (see NP no[w], jo[w], rūzī, correspondingly). Thus, Pisowicz considers the օṷ diphthong as being made up of o + ṷ, in which ṷ is an allophone of v.Footnote 39 The ow diphthong is phonemic.Footnote 40 In the manuscripts being discussed, the ow diphthong found in the middle of words is rendered by օվ [ôv]:

Ms. sôvgant [սովգանտ]—ժ.պ. so[w]gand “oath, swearing”;

Ms. łôvłay [ղօվղայ]—NP gho[w]ghā “tumult”;

Ms. môvč [մօվճ]—NP mo[w]j “wave”;

Ms. nôv [նօվ]—NP no[w] “new,” etc.

The Diphthong ey

In the middle of a word, the Persian diphthong -ey- is rendered by է [ê], which is typical for eighteenth century Persian.Footnote 41 See:

Ms. pʻêday [փէդայ] –NP peydā “apparent”;

Ms. pʻêkʻar [փէքար]—NP peykar “digit, figure”;

Ms. pʻêvasta [փէվաստա]—NP peyvaste “connected, always”;

Ms. fêz [ֆէզ]—NP feyz “benignity”;

Ms. łêr [ղէր]—NP gheyr “other.”Footnote 42.

The Pharyngeal Phoneme ayn

This phoneme, which is a glottal stop in words of Arabic origin, is written in certain ways in these manuscripts.

At the beginning of the following words, it is transcribed as այ- [ay-]:

Ms. aynasowr [այնասուր]—NP ʻanāṣor “elements”;

Ms. ayhǝt [այհըտ]—NP ʻahd “promise, covenant.”

Mainly, this glottal stop is deleted in consonant clusters, whether word-final or word-medial positions. See:

Ms. alam [ալամ]—NP ʻālam “world”;

Ms. atl [ատլ]—NP ʻadl “justice”;

Ms. asay [ասայ]—NP ʻaṣā “cane, stick”;

Ms. šǝroy [շըրոյ]—NP shurūʻ “beginning”;

Ms. mazam [մազամ]—NP muʻaẓẓam “honorable”;

Ms. marowf [մարուֆ]—NP maʻrūf “famed, famous”;

Ms. bad [բադ]—NP baʻd “after, then,” etc.

The Transcription of the ezafe

In Persian syntax, the connector between the determinant-determinate and substantiator-substantive is the ezafe, which is not always reflected in the manuscripts.

Following a consonant, the perceptible ezafe like -e is not transcribed according to the Arabic and Persian writing rules:

Ms. avaz ow [ավազ ու]—NP āvāz(-e) ū “his voice, his song”;

Ms. tʻir inšan [թիր ինշան]—NP tir(-e) inshān “their sword,” etc.

In a very rare cases, following a vowel, it is transcribed as -յի /-yi/:

Ms. kʻǝnarhayi zǝmin [քընարհայի զըմին]—NP kenārhā-ye zamīn “the edges of earth”;

Ms. xanayi ibrayim [խանայի իբրայիմ]—NP khāne-ye Ebrāhīm “Ibrahim’s house”;

Ms. ǰhar gwšayi alam [ջհար գուշայի ալամ]—NP çehār gūshe-ye ʻālam “the four corners of the world,” etc.

In general, the connective clitic of ezafe was not written after vowels, either.

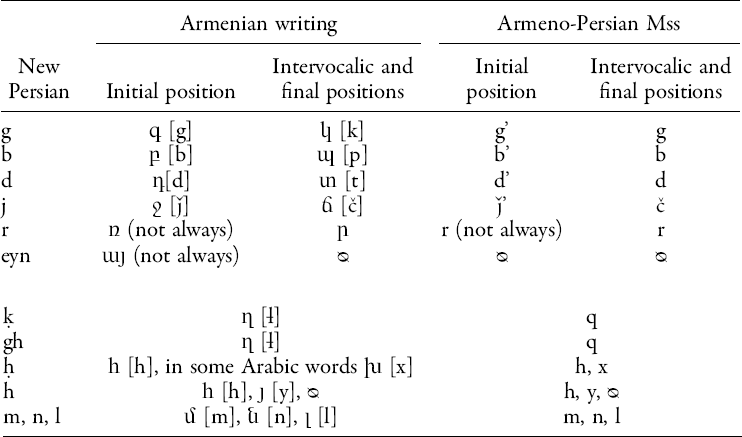

Persian Consonant Transcription

In the manuscripts under discussion, the rules of Middle Armenian orthography of consonants are utilized. There are original sources from that period (for example, the verses of Constantine of Erzincan, etc.) where a system of four levels of consonants is used.Footnote 43 In these manuscripts, voiced plosives in word-initial position are rendered by Armenian’s voiced plosives (that is, b-, g-, d-, j- are written բ- [b-], գ- [g-], դ- [d-], ջ- [ǰ-]), whereas in the middle and at the end of words they are rendered respectively by their unvoiced non-aspirated counterparts, -պ- [-p-], -կ- [-k-], -տ- [-t-], and -ճ- [-č-].Footnote 44 We think that in this case, this difference comes from the voiced plosives’ position, based on the contrast between aspirated and non-aspirated phonemes. Non-aspirated voiced stops in the middle and at the final positions of words preserve their voiced quality and differ from their counterparts at the beginning of words that are aspirated. That is, voiced plosives at the beginning of words are aspirated, expressed by voiced letters, while in the middle and at the end of words they are non-aspirated and are rendered by non-aspirated unvoiced plosives.Footnote 45 This observation from these manuscripts allows us to conclude that the scribes of Armeno-Persian manuscripts used orthographical rules which were typical for the Armenian Araratyan dialect,Footnote 46 where the voiced consonants in the initial position are aspirated ones and the unvoiced, non-aspirated consonants are voiced in the middle position.Footnote 47 This peculiarity was special to the Armenian Nor-Jugha (Jolfā) dialect,Footnote 48 which was the mother dialect of Hakim Yaghub, the scribe of Ms. 8492.Footnote 49 Thus, the examined Armenian-script Persian texts brought us to understand the usage of Armenian orthographic rules only and not the change of Persian phonetic units’ value.Footnote 50

In intervocalic and final positions NP -g- → Ms. -կ- [-k-]. See:

Ms. dikar [դիկար]—NP dīgar “other”;

Ms. akar [ակար]—NP agar “if”;

Ms. ankapin [անկապին]—NP angabīn “honey”;

Ms. bǝzôrktar [բըզօրկթար]—NP buzurgtar “bigger”;

Ms. tʻank [թանկ]—NP tang “narrow”;

Ms. sank [սանկ]—NP sang “stone,” etc.

New Persian g- > Ms. գ- [գ-] in initial position:

Ms. gǝroy [գըրոյ]—NP gurūh “group”;

Ms. -gan [-գան]—plural marker –gān;

Ms. gardanat [գարդանատ]—NP gardānad “will become,” etc.

In the middle and at the end of words NP -b- → Ms. պ [-p-]:

Ms. kʻǝtʻap [քըթապ]—NP ketāb “book”;

Ms. sapap / sabab [սապապ / սաբաբ]—NP sabab “reason, cause”;

Ms. powt [պուտ]—NP būd “was”;

Ms. nay pašat [նայ պաշատ]—NP nabāshad “not be”;

Ms. powtant [պուտանտ]—NP būdand “they were”;

Ms. iplis/iblis [իպլիս / իբլիս]—NP eblīs “Devil”;

Ms. xap [խապ]—NP khwāb “sleep”;

Ms. pašat [պաշատ]—NP bāshad “will be”;

Ms. aftap [աֆտապ]—NP aftāb “sun”;

Ms. palkʻi [պալքի]—NP balke “rather than,” etc.

Word-initial NP b- → Ms. բ- [b-]:

Ms. bay [բայ]—NP bā “with”;

Ms. mibinam [միբինամ]—NP mībīnam “I see”;

Ms. biayieat / piayieat [բիայիեատ / պիայիեատ]—NP biāyad “he will come”;

Ms. bǝsiar [բըսիար]—NP besiyār “most”;

Ms. banday [բանդայ]—NP bande “slave, servant”;

Ms. zǝban/zǝpan [զըբան/զըպան]—NP zabān “language”;

Ms. bwniad [բունիադ]—NP bunyād “base, basis”;

Ms. barakʻatʻ [բարաքաթ]—NP barakat “blessing,” etc.

New Persian -d- > Ms. -տ- [-t-] in intervocalic and final positions:

Ms. šôtan [շօտան]—NP shudan “to become”;

Ms. mownênt [մունէնտ]—NP mānand “resembling, like”;

Ms. ǝntaxtay [ընտախտայ]—NP andākhte “thrown”;

Ms. ômatan [օմատան]—NP āmadan “to come”;

Ms. dahat [դահատ]—NP dahad “will give”;

Ms. šôvat [շօվատ]—NP shavad “will be”;

Ms. afrit [աֆրիտ]—NP āfarīd “created”;

Ms. kʻart [քարտ]—NP kard “he did”;

Ms. bǝngirant [բընգիրանտ]—NP benegarand “they will watch,” etc.

Word-initial and in the intervocalic positions NP -d- → -դ- [-d-]:

Ms. andišay [անդիշայ]—NP andishe “idea, mind”;

Ms. dar [դար]—NP dar “in”;

Ms. adam [ադամ]—NP ādam “men”;

Ms. dit [դիտ]—NP dīd “he saw”;

Ms. dêl [դէլ]—NP del “heart,” etc.

New Persian -j- > Ms. -ճ- [-č-] in intervocalic and the final positions:

Ms. inčil [ինճիլ]—NP enjīl “Gospel”;

Ms. xarǝč [խարըճ]—NP khārej “outside”;

Ms. môvč [մօվճ]—NP mowe “wave”;

Ms. tʻowčar [թուճար]—NP tujjār “merchant,” etc.

Also NP -j- > Ms. -ջ- [-ǰ -]:

Ms. ǰay [ջայ]—NP jāy “place”;

Ms. ǰayhatʻ[ջայհաթ]—NP jehat “course, reason”;

Ms. ǰǝhan [ջըհան]—NP jehān “world”;

Ms. bôrǰi [բօրջի]—NP burjī “a tower”;

Ms. ownǰay [ունջայ]—NP ānjā “there”;

Ms. môvǰowp [մօվջուպ]—NP muvajeb “occasioned, consequence,” etc.

There are few words in which the NP voiceless affricate ç is rendered by the voiced affricate -ջ- [-ǰ-], in all other cases this phoneme is written ç:

Ms. ǰar [ջար]—NP çahār “four”;

Ms. ǰarsat [ջարսատ]—NP çahārṣad “four hundred”;

Ms. nayǰar [նայջար]—NP nāçār “helpless, compelled,” etc.

As we see here, this sound shift occurs only in the case of the word çahār “four”, which is in its Arabicized form when written with a -j-. This is also present in the contemporary colloquial Armenian.

In Persian consonant clusters ft, kht, st, sht the second phoneme t (apicodental, voiceless) is rendered by the Armenian unvoiced non-aspirated letter տ [t], based on Armenian orthographic rules. According to these rules, the only position where unvoiced non-aspirated plosives retain the former quality is next to voiceless fricatives. Based on this rule, foreign voiceless plosives in these positions were rendered by their respective unvoiced non-aspirated letters. This rule also applies to the manuscripts under discussion. See:

Ms. gôft [գօֆտ]—NP guft “he said”;

Ms. rast [ռաստ]—NP rāst “true, right”;

Ms. ast [աստ]—NP ast “is”;

Ms. šǝkʻast [շըքստ]—NP shekast “he broke”;,

Ms. kʻôšt [քօշտ]—NP kusht “he killed”;

Ms. daštam [դաշտամ]—NP dāshtam “I had”;

Ms. amowxtam [ամուխտամ]—NP āmūkhtam “I learned”;

Ms. šnaxt [շնախտ]—NP shenākht “he knew,” etc.

Persian’s voiceless plosive t phonemeFootnote 51 is written in Armenian with its respective aspirant counterpart, թ [tʻ], in all other positions. See:

Ms. tʻamam [թամամ]—NP tamām “finish, whole”;

Ms. łimatʻ [ղիմաթ] –NP qeymat “cost, valuation”;

Ms. Bētʻalmowłatas [բէթալմուղատաս]—NP Beyt l-Muqaddaṣ “Jerusalem”;

Ms. tʻavanat [թավանատ]—NP tavānad “will be able”;

Ms. batʻǝl [բաթըլ]—NP bāṭel “null, void”;

Ms. gitʻi [գիթի]—NP gītī “world.”

The voiced plosive becomes devoiced before the comparative suffix -tar, while the voiced fricatives are preserved. This morpheme is mainly written separately and is treated as a separate word, preserving the word-initial aspirant, թ- [tʻ-]:

Ms. zowttʻar [զուտ թար]—NP zūdtar “before”;

Ms. bǝzôrktʻar [բըզoրկ թար]—NP buzurgtar “bigger”;

Ms. bôlanttʻar [բօլանտ թար]—NP bulandtar “higher,” etc.

Persian’s voiceless plosives p, k, and ç have been transcribed with their appropriate voiceless aspirated counterparts in Armenian փ [pʻ], ք [kʻ], չ [čʻ]. See:

Ms. kʻnar [քնար]—NP kenār “side, edge”;

Ms. čʻapʻ [չափ]—NP çap “left”;

Ms. ekʻ [եք]—NP yek “one”;

Ms. aškʻaray [աշքարայ]—NP āshkārā “open, frank”;

Ms. pʻadišayan [փադիշայան]—NP pādeshāhān “kings”;

Ms. kʻi/e [քի/ե]—NP ke “that, which”;

Ms. tʻarikʻ [թարիք]—NP tārīk “dark”;

Ms. čʻašm [չաշմ]—NP çashm “eye,” etc.

The Persian dorso-uvular voiced phoneme q is comprised of two distinct allophones, the uvular, plosive, voiceless ḳ, and the postdorsal voiced fricative γ. Their pronunciation does not have an effect on the word’s definition, but is still apparent depending on the style and genre of the text. In the Armeno-Persian Gospels, the writing of these allophones does not indicate any distinctive peculiarities. Both of the allophones are rendered by the Armenian character ł [ղ], which denotes a voiced, postdorsal, spirant sound. See:

Ms. xalł [խալղ]—NP khalq “people”;

Ms. łôm [ղօմ]—NP qum “tribe”;

Ms. bałi [բաղի]—NP bāqī “rest, left”;

Ms. ałaz [աղազ]—NP āghāz “beginning”;

Ms. pʻełambar [փեղամբար]—NP peyghambar “Prophet”;

Ms. łǝsas [ղըսաս]—NP qeṣāṣ “punishment” etc.Footnote 52

The Persian nasals m, n and the lateral liquid l are written with their Armenian counterparts մ [m], ն [n] and լ [l], respectively.

The transcription of Persian r is quite mixed, sometimes written with ր [r] or ռ [ṙ]. See:

Ms. ṙwz [ռուզ]—NP rūz “day”;

Ms. ray [րայ]—NP rā postposition;

Ms. raftan [րաֆտան]—NP raftan “to go”;

Ms. bar [բար]—NP bar “on, upon”;

Ms. atʻraf [աթրաֆ]—NP aṭrāf “sides”;

Ms. harakʻatʻ [հարաքաթ]—NP ḥarakat “movement”;

Ms. xar/ṙ [խար/ռ]—NP khar “donkey”;

Ms. pʻaṙ kʻayi [փառ քայի]—NP parr-e kāhī “chaff”;

Ms. baṙaygan [բառայգան]—NP barrehā “lambs,” etc.Footnote 53

Morphophonology

Spirantization. In colloquial Persian, the dorso-uvular stop q phoneme loses its voiced quality and spirantization takes place next to unvoiced aspirants and sibilants and is pronounced x. In the manuscripts under discussion, this phoneme is rendered by Armenian -խ- [-x-]. See:

Ms. vaxtʻ/t [վախթ/տ]—NP vaqt “time”;

Ms. nôx/łtʻay [նօխ/ղթայ]—NP nuqte “point, dot”;

Ms. maxsowt [մախսուտ]—NP maqṣūd “aim, purpose”;

Ms. tʻaxex [թախեխ]—NP tahqīq “research, disquisition,” etc.

Dissimilation. In colloquial Persian, the affricate j sometimes spirantizes and becomes a fricative before another occlusive. The manuscripts preserve this in the following example:

Ms. sowžde [սուժդե]—NP sajde “prostration.”Footnote 54

Labialization. The nasal n labializes before -b and is pronounced -mb-. In the manuscripts it is written –մբ- [-mb-]. See:

Ms. hambônčay [համբօնչայ]—NP anbān [ambān] “sack”;

Ms. tʻambē [թամբէ]—NP tanbīh [tambih] “punishment”;,

Ms. šambē [շամբէ]—NP shanbe [shambe] “Saturday.”

Deletion. The glottal -h deleted in medial consonant clusters and word-end no-cluster position. In the manuscripts in the word-end position -h deleted giving way to -յ [-y] (see above), which is also unique to colloquial Persian,Footnote 55 and -h- is deleted whether it is the first or second consonant of a cluster, e.g.:

Ms. šar [շար]—NP sharḥ “explanation”;

Ms. šar [շար]—NP shahr “city”;

Ms. gay [գայ]—NP gāh “date, time”;

Ms. day [դայ]—NP dah “ten”;

Ms. gǝroy [գըրոյ]—NP gurūh “group”;

Ms. nǝgay [նըգայ]—NP negāh “look, view,” etc.

Insertion ը [ə] before the -ստ- [-st-] cluster. In Middle Armenian, an ը [ə] was pronounced and written in word-initial position prior to such a cluster. This tradition was also followed in the eighteenth century Armenian orthography,Footnote 56 and we have noted this phenomenon in Armeno-Persian manuscripts used for combining words:

Ms. danəstay [դանըստայ]—NP dāneste “known”;

Ms. sankəstan [սանկըստան]—NP sangestān “rocky”;

Ms. nəšəstan [նըշըստան]—NP neshastan “to seat”;

Ms. mi tʻvanəst [մի թվանըստ]—NP mītavanest “he could.”

And development of unstressed vowels to shwa [ə] in word-initial position:

Ms. əstat [ըստատ]—NP istād “he stood up”;

Ms. əstatant [ըստատանտ]—NP istādand “they stood up.”

Shifting. The shift -ḥ- > -x- in the manuscripts is only seen in words of Arabic origin, depending on their pronunciation in Armenian dialects where the shift -ḥ- > -x- had already occurred.Footnote 57 We believe that this is a result of the scribe (hailed from Nor-Jugha) and spoke a subdialect related to the Armenian dialect of Tabriz, which distinguished itself mainly through its -ḥ- > -x- shift.Footnote 58

Ms. zaxmatʻ [զախմաթ]—NP zaḥmat “bother, discomfort”;

Ms. ṙaxmatʻ [ռախմաթ]—NP raḥmat “charity”;

Ms. ǝxtiač [ըխտիաճ]—NP eḥti(y)āǰ “need”;

Ms. ṙaxm kʻown [ռախմ քուն]—NP raḥm kun “have mercy”;

Ms. xošxāl [խոշխալ]—NP khushḥāl “happiness” (which is in fact not entirely a word of Arabic origin, and is made up of Persian khush “good” and Arabic ḥāl “state”);

Ms. ṙaxlatʻ [ռախլաթ]—NP reḥlat “death,” etc.

Word-initial շք- [shk-] is written սք- [skʻ-], and was probably pronounced as such:

Ms. skʻanǰay—NP shekanje “torture.”

A š → s shift is seen in the Ms. 3044 f. 38r, in the word, չասմ [čʻasm] “eye,” see NP çashm.

The shift -r- > -l- occurs only in the word, barg “leaf” > NP balk [բալկ] (Ms. 8492, f. 57v).

The shift -b- > -v- met in the Ms. 8492 f. 63v, in the word maƚvar [մաղվար]—maqbar “tomb.”

There are particular writing conventions that reflect the pronunciation of the word that was already present in Armenian due to an earlier borrowing:

Ms. hownarmand tʻar [հունարմանդ թար]—NP hunarmandtar “more talented.” The Persian term hunar had made its way into Armenian dialects via Turkish as hunar.

Ms. dêv [դէվ]—NP div “demon, evil spirit” appears as Arm. < MP dēv with the meaning “evil spirit” in the Biblical tradition.Footnote 59

Ms. hečʻ [հեչ]—NP hiç “nothing”; cf. ENP hēç > Arm. dialects hečʻ [հեչ] via Turkish.

Ms. mêǰlis [մէջլիս]—“assembly, collective”; cf. ENP majles > Arm. dialects mêȷlis [մէջլիս] via Turkish. See also Ms. mêǰlisian [մէջլիսիան] “guests.”

Ms. mêlikʻ [մէլիք]—“prince, landlord”; cf. NP, ENP mālek > Arm. dialects mêlikʻ [մէլիք] via Turkish.

Conclusion

Thus, the scribes of the Armeno-Persian manuscripts Ms. 8492 and Ms. 3044 successfully utilized the Armenian characters and their phonetic values to express the Persian spoken in eastern Transcaucasia in the eighteenth century. The study of the writing features of the texts sheds light on the typical peculiarities of the Armenian orthographical rules and on the Persian pronunciation of the time.

The writing of Persian phonemes and their phonetic values expressed in Armenian letters in Ms. 8492, Ms. 3044 are presented in the following tables:

Vowels:

Consonants:

Diphthongs

Clusters

Figure 1. Ms. 3044, f. 10a: a part of the Unified Gospel colophon written in Persian (thirteenth century) rendered in Armenian script (eighteenth century).

Source: The Collection of Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran.

Figure 2. Ms. 3044, f10b: the colophon of the introduction to the Persian Gospels manuscript. The first part written in Persian and rendered in Armenian script and the second part is written in Armenian.

Source: The Collection of Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran.

Figure 3. Ms.8492, f236b: The colophon of the manuscript.

Source: The Collection of Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran.

Figure 4. Ms. 8492, f187a: the first page of the Gospel according to John.

Source: The Collection of Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran.